Abstract

Male romantic jealousy is a commonly cited driver of intimate partner violence against women. An in-depth, contextualised understanding of the pathways and mechanisms from jealousy to intimate partner violence is, however, needed to inform programmes and interventions. We triangulated data from 48 interviews, eight focus groups and 1216 survey findings from low-income married women and men in northern Ecuador. Male jealousy was associated with controlling behaviours (aOR: 14.47, 95% CI: 9.47, 22.12) and sexual intimate partner violence (aOR: 2.4, 95% CI: 1.12, 5.12). Controlling behaviours were associated with physical and sexual intimate partner violence (aOR: 2.16, 95% CI: 1.21, 3.84). Qualitatively we found that most respondents framed jealousy within a discourse of love, and three triggers of male jealousy leading to intimate partner violence were identified: (1) community gossip, which acted as a mechanism of community control over women’s movements and sexuality; (2) women joining the labour force, which was quantitatively associated with intimate partner violence and partially mediated by jealousy; and (3) women’s refusal to have sex, which could lead husbands to coerce sex through accusations of infidelity. Gender-transformative interventions at the individual, couple and community level providing models of alternative masculinities and femininities may offer promise in reducing intimate partner violence in Ecuador. Importantly, future economic empowerment interventions should address jealousy to mitigate potential intimate partner violence backlash.

Introduction

Intimate partner violence is a major and persistent public health and human rights issue with an estimated one-third of women worldwide experiencing it during their lifetime (WHO Citation2021). This study investigated intimate partner violence within the context of marriage; intimate partner violence being defined as any behaviour ‘that causes physical, sexual or psychological harm’ (WHO Citation2021).

Psychological harm can include controlling behaviours, such as isolating a person from friends and family, or monitoring their movements (WHO Citation2021), and economic intimate partner violence, a form of controlling behaviour in which one limits a partner’s ability to lead an economically productive life (e.g. by restricting their employment or education) (Gibbs, Dunkle, and Jewkes Citation2018). Intimate partner violence can have a variety of short-, mid- and long-term health and social consequences, in the most severe cases resulting in homicide and increased risk of suicide attempts (WHO (World Health Organization) Citation2021). Intimate partner violence can be perpetrated against both men and women, but throughout this study our focus is on intimate partner violence perpetrated by men against women.

In Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC), where traditional gender norms are pervasive, romantic jealousy is often cited as a risk factor for intimate partner violence (Bott et al. Citation2012). Little empirical research in the region, however, has thoroughly explored the pathways and mechanisms by which romantic jealousy leads to intimate partner violence. To gain this deeper understanding and inform programmes and interventions we conducted a sequential, exploratory, mixed-methods secondary analysis of data from low-income Colombian and Ecuadorian men and women living in northern Ecuador.

Intimate partner violence and gender norms in LAC

An estimated one-quarter of women in LAC will experience intimate partner violence during their lifetime, with a higher estimate for women living in rural areas (WHO Citation2021). Of women over 15 years of age in Ecuador, 25% experience physical intimate partner violence, 8% sexual intimate partner violence, 41% psychological intimate partner violence and 15% economic intimate partner violence, in their lifetime (INEC Citation2019). In 2018, Ecuador passed the Comprehensive Organic Law to Prevent and Eradicate Violence against Women, aiming to eradicate violence against women by raising awareness of the problem and increasing protection and reparations for women who have experienced violence (Government of Ecuador Citation2018). Legal efforts to delegitimise violent behaviours, however, are not sufficient to end culturally engrained practices, and throughout LAC adherence to traditional gender norms and hegemonic masculinities (Connell and Messerschmidt Citation2005) has consistently been associated with intimate partner violence perpetration (e.g. Boyce et al. Citation2016; Lennon et al. Citation2021).

LAC scholars describe the prevalent expression of hegemonic masculinity as machismo. Narratives from the late 1950s portrayed machistas as philandering, authoritarian, oppressive, aggressive men who view women as possessions to be dictated to and controlled (Fuller Citation2012). Initial revisionist interpretations framed these negative traits alongside chivalry, bravery, strength and honour to portray a ‘benevolent sexism’ (Goicolea, Coe, and Ohman Citation2014). Today hypermasculine machismo has become a caricature that reflects masculine insecurity (Fuller Citation2012), particularly among young LAC adults (Goicolea, Coe, and Ohman Citation2014). Sexual prowess, however, still plays a central role in men’s understanding of what it means to be a ‘proper’ man and can be a key component of male bonding and group acceptance (Buller Citation2010; Flood Citation2008). The extent to which local gender norms construct masculinities in line with machismo or offer alternative masculinities has important implications for intimate partner violence by affecting the degree to which violence is condoned.

Closely aligned with machismo is the feminine equivalent marianismo which draws on religious roots of the Virgin Mary to frame Latina women as morally and spiritually superior to men (Agoff, Herrera, and Castro Citation2007). Castillo et al. (Citation2010) conceptualise marianismo as comprising five pillars whereby women should be: (1) the source of strength and happiness for their families; (2) virgins until marriage and faithful to their husbands; (3) respectful of traditional, hierarchal, gendered power differentials; (4) silent to maintain conflict-free relationships; and (5) responsible for the spiritual growth and religious practice of their families. The extent to which local femininities are constructed in accordance with marianismo may play a critical role in women’s experiences of partner jealousy and intimate partner violence by affecting how impacted they are by accusations of infidelity (pillar 2), how hierarchical they believe their relationship with their husband should be (pillar 3) and whether they are expected to maintain family harmony even in the context of violence (pillar 4).

Romantic jealousy and intimate partner violence

White (Citation1981) defines romantic jealousy as ‘a complex set of thoughts, feelings and actions that follow a threat to self-esteem and/or threaten the existence or quality of the relationship. These threats are generated by the perception of a real or potential attraction between the partner and a (perhaps imaginary) rival’ (p. 24). The emotions that make up romantic jealousy and the reactions considered appropriate in response to it may differ cross-culturally (Salovey Citation1991). Low levels of romantic jealousy have been found to protect a relationship (White Citation1981), while higher levels have been associated with lower relationship quality and satisfaction (Barelds and Barelds-Dijkstra Citation2007) and unidirectional and bidirectional intimate partner violence (Pichon et al. Citation2020). In a recent global systematic review, Pichon and colleagues (Citation2020) identified six pathways from romantic jealousy to intimate partner violence and three underlying mechanisms: (1) threatened masculinities, (2) threatened femininities, and (3) patriarchal beliefs; suggesting that gender norms play a major role in perpetuating intimate partner violence. Only four of the 51 studies included in the systematic review, however, were conducted in LAC indicating more research within the region is needed.

In studies exploring risk factors of intimate partner violence in LAC romantic jealousy features prominently and is often cited as the second most common trigger of perpetration after alcohol (Bott et al. Citation2012). In Ecuador, 29.9% of respondents in a national survey thought ‘wife-beating’ was acceptable in cases of actual or suspected infidelity (Bott et al. Citation2012). Despite being commonly cited as a trigger of, and justification for intimate partner violence in LAC, the pathways and mechanisms from romantic jealousy to intimate partner violence are understudied and underutilised in programmes and interventions. For programmes and interventions to effectively target romantic jealousy leading to intimate partner violence, we must first gain a better understanding of what triggers romantic jealousy, what are common reactions to romantic jealousy, and why romantic jealousy so often results in intimate partner violence. This study aims to begin to fill these gaps by answering the following research questions: (1) what is the association between romantic jealousy and different forms of intimate partner violence in Ecuador; and (2) what are the pathways and mechanisms from romantic jealousy to different forms of intimate partner violence in Ecuador?

Methods

Settings

Ecuador is a predominantly Roman Catholic country and maintains a largely patriarchal society (UN Women Citation2021). Data for this study were collected in seven urban areas of the Sucumbíos and Carchi provinces in northern Ecuador. Sucumbíos is in the Amazon region while the Andes Mountains traverse the majority of Carchi. Due to cross-border drug and human trafficking, Sucumbíos and Carchi have some of the highest homicide rates in the country (Conway Citation2013). These provinces are also among the poorest and have a heavy influx of refugees from bordering Colombia (UNHCR Citation2020). Colombian refugee women living in Ecuador face many personal, social and structural challenges that compound their risk of experiencing intimate partner violence including financial stress, no fixed residence, previous experiences of violence, social isolation, lack of legal documentation and restricted mobility (Hynes et al. Citation2016; Keating, Treves-Kagan, and Buller Citation2021).

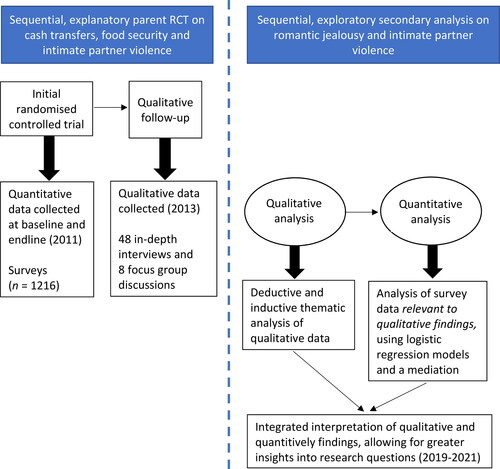

Study design

We conducted a secondary analysis of data from a six-month randomised controlled trial (RCT) of a World Food Programme cash transfer and food assistance intervention. The programme successfully increased food security and social cohesion and decreased intimate partner violence (Hidrobo et al. Citation2012; Hidrobo et al. Citation2014). To explore how increased cash and food security influenced household dynamics, a two-phase, mixed-methods study was carried out. The quantitative sample included 148 clusters; randomisation was stratified at the province level. A selected group of low-income households in each cluster were administered a paper survey prior to intervention start (March-April 2011) and approximately seven months later (October-November 2011).

The final sample with baseline and follow-up data on intimate partner violence consisted of 1216 women ages 15-69 years that were in the same partnership at time 1 and time 2. The mean age of the quantitative sample was 35 years for women and 39 years for their partners. Approximately two-thirds of participants were Ecuadorian and one-third Colombian. For most, their highest level of education was primary school or lower, and about one-third of women reported participating in the labour force at time 1. Partners were educated at a similar level to their wives and almost all participated in the labour force () (for more information see Hidrobo et al. Citation2012; Hidrobo et al. Citation2014).

Table 1. Household characteristics of a sample of low-income Ecuadorian and Colombian refugees at time 1, age 15–69, in partnership, living in northern Ecuador (n = 1216).

Qualitative phase participants were purposively sampled according to whether their experiences of intimate partner violence increased or decreased during the intervention. Individuals who did not participate were included as controls. The fieldwork was conducted 21 months after the intervention (see online supplemental Appendix 1 for a timeline). Forty-eight in-depth interviews (IDIs) with women and eight focus group discussions (FGDs) with a total of 52 participants were carried out, half in each province. In Sucumbíos, 20 individuals participated in FGDs and groups ranged from three to six. In Carchi, 32 participated in FGDs and groups ranged from five to nine. FGDs were conducted with women and men from the intervention arm, husbands of women from the intervention arm and men from the control group (the perspectives of women in the control group were captured in IDIs) (). The total qualitative sample included 100 participants, 16-66 years old. Included men and women were not in relationships with one another.

Table 2. Characteristics of focus group discussions (FGDs) (n = 52).

Two Ecuadorian women who had previously interviewed people experiencing disadvantage in the region conducted the IDIs. The principal investigator (AMB) who is a native Spanish speaker with extensive experience interviewing men about violence conducted the FGDs. Topic guides covered: (1) background and social networks; (2) intra-household dynamics; (3) experience and views of the intervention; (4) attitudes towards and experiences of intimate partner violence; and (5) women’s empowerment. Audio files lasted approximately one-hour and were transcribed verbatim in Spanish (see Buller et al. Citation2016).

Secondary analyses

The study took the form of a sequential, exploratory, secondary analysis of the data from the RCT and qualitative follow-up. Three researchers (including AMB who led the original qualitative study) conducted a thematic analysis of qualitative data from Sucumbíos (CC and AMB) and Carchi (MP and AMB) using a constant comparative method supported by NVivo 12. Following an initial scoping of the transcripts, researchers returned to the literature to identify key deductive themes which formed the basis of initial codes (e.g. Boyce et al. Citation2016). During this process, researchers explored key study elements – local gender norms, romantic jealousy and intimate partner violence – to understand how they related to one another. As the researchers read transcripts they allowed new codes to develop inductively from the data such as ‘family disapproval of wife’ and ‘neighbourhood gossip’ as triggers of romantic jealousy leading to intimate partner violence. They continually refined codes, adding detail and nuance to child codes and then grouping them into bigger themes under parent codes such as ‘community gossip about female infidelity’. As the coding tree developed, they revisited transcripts for additional evidence of support or challenges to coding decisions.

Once the qualitative data had been analysed another researcher (STK) mapped the qualitative findings onto the quantitative dataset using available, relevant quantitative indicators to determine if there were similar trends in the quantitative data (see online supplemental Appendix 2 for a comparison between qualitative and quantitative results). The outcome variables assessed physical and sexual intimate partner violence in the last six months (at time 2) using the WHO Violence Against Women Instrument. Independent variables of interest included partner romantic jealousy and controlling behaviours (see for more details) and were measured at time 1 to establish temporality between the behaviours.

Table 3. Experience of romantic jealousy, controlling behaviours and recent intimate partner violence in a sample of partnered women, age 15-69, living in northern Ecuador (n = 1216).

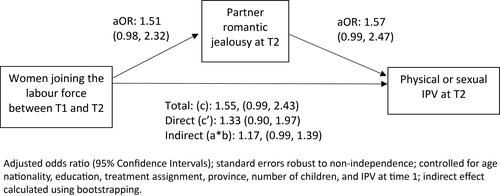

Adjusted odds ratios (aOR) with standard errors robust to non-independence were calculated to examine the relationship between romantic jealousy and controlling behaviours at time 1, and physical and sexual intimate partner violence at time 2. Guided by qualitative results, an analysis was then conducted to test if romantic jealousy acts as a mediator of the relationship between women joining the labour force and physical and sexual intimate partner violence. We identified direct and indirect effects, accounting for clustering of data, and using bootstrapping to compute standard errors to assess the significance of the mediated effect (). All models controlled for age, nationality, education, treatment assignment, province, number of children and physical and sexual intimate partner violence at time 1. The triangulated mixed-methods results were then interpreted together by the whole team, allowing for enhanced insights into the research question ().

Ethical considerations

All participants provided written informed consent. All women were provided with contact information for local support services regardless of whether they reported experiencing violence. Review board approval for the RCT was obtained from the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) and the in-country data collection partner Centro de Estudios de Población y Desarrollo Social. The qualitative follow-up received ethical approval from IFPRI and the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM). The qualitative component of the secondary analysis obtained additional ethical approval from LSHTM (Ref: 17859).

Results

We begin by presenting our findings on the prevalence’s of romantic jealousy and intimate partner violence, and the mixed-methods associations between them. We then present the three common triggers of romantic jealousy leading to intimate partner violence that arose from our qualitative data, and the quantitative findings that triangulate them.

Prevalence of romantic jealousy and intimate partner violence

Male romantic jealousy was identified in almost all IDIs and FGDs as a major factor leading to intimate partner violence despite not being explicitly covered in the topic guides. Quantitatively, approximately 11% of female participants reported partner romantic jealousy at time 1; a similar number had experienced controlling behaviours at time 1. At time 2, 16% reported recent physical or sexual intimate partner violence ().

Mixed-method associations between romantic jealousy and intimate partner violence

Qualitatively, most participants referred to romantic jealousy as desirable in a relationship and thought that if a woman’s husband was not jealous he did not love her. For example, when describing her neighbours one woman said: ‘Her husband sends her to dance with her girlfriends and he does not get jealous […], [about this] my husband says, he does not love her, that is why he does not get jealous’ (37-year-old woman, IDI, Sucumbíos). This perception of male romantic jealousy as a manifestation of love meant it was socially tolerated, and men used this acceptability often to exert control over their wife’s behaviours.

Although most participants viewed jealousy as a manifestation of love, some younger women had mixed feelings or rejected this notion completely. For example, one woman said: ‘You know, they say it [jealousy] is love, but it is not love, it is like a sickness’ (25-year-old woman, FGD 5, Carchi). There was also evidence of some variation in beliefs about the acceptability of controlling women’s behaviours. For example, when asked to describe a situation when she felt physically threatened by her partner, a woman responded: ‘He didn’t want me to go out with my friends. I said to him, you can’t prohibit me, we are together yes, but that doesn’t mean that I am your house slave’ (18-year-old woman, IDI, Sucumbíos). Here, the participant clearly rejects traditional gender roles and emphasises the importance of women’s freedom of movement, despite feeling unsafe doing so.

In contrast to jealousy, infidelity was described as signifying the absence of love and being very distressing for the faithful partner. One participant saying she would rather ‘be beaten up’ than cheated on and describing infidelity as the ultimate ‘betrayal’ and ‘the hardest’ ‘most ugly’ thing a person could endure (25-year-old woman, IDI, Carchi). Most participants reported that physical violence was never justified in a relationship, but many made exceptions in cases of infidelity. For example, a woman reflected: ‘in the moment of rage [after being cheated on] the person isn’t thinking’ (30-year-old woman, IDI, Carchi). The colloquial term for female infidelity, poner los cuernos or ‘putting the horns [on his head]’ foregrounds the unknowing partner, while the horns symbolise the infidelity that all (other than the ridiculed, faithful partner) can see. There was a prevailing belief that women were unfaithful because they weren’t sexually satisfied. Thus, men were humiliated by partner infidelity and sometimes used threats of violence to try to prevent it, as illustrated in the following extract:

He says that if he sees me with someone else, […] then he’ll cut off my bum, or my breast… I never know if he’s being serious or joking […] Sometimes when he sees a woman putting the horns [cheating] on her husband he reiterates to me, he says it again. (40-year-old woman, IDI, Sucumbíos)

Men were described as machistas when the control they exerted over their wife was considered extreme, but the line between socially acceptable and unacceptable control was not always clear and men experienced a tension between fulfilling gender roles and avoiding the negative machista label. For example, when asked who made the decisions in his household, one man responded: ‘In my case it’s always me. The man is the one who makes the decisions […] But, of course I don’t want to say with this that I’m machista’ (33-year-old man, FGD 2, Sucumbíos). This suggests that level of control was not the distinguishing factor between socially sanctioned male roles and machismo. Instead, the evidence points to the difference being in how men enforce this control and how they relate to women. Men who told their wife how she should behave and why were perceived favourably by participants, while machistas were described as hot-tempered and violent men who were desperate to prove their manliness. For example, a participant described machistas as men who believe ‘if they hit a woman then they are more of a man’ (36-year-old woman, IDI, Sucumbíos). Machismo was usually associated with older men, and there was a prevailing narrative that machistas were from a disappearing generation.

Women’s gendered identities centred on maintaining their virginity until marriage and being a faithful wife. Femininities were linked to being hyposexual (in contrast to men’s hypersexuality) and women were expected to be sexually satisfied by their husbands and not tempted by other men. Local gender norms differed depending on a woman’s marital status. Female participants stated that before marriage they could dress in revealing clothing, talk loudly with friends and work outside the home. After marriage, however, women faced stricter societal constrains; their identities became linked to their husbands and her behaviours could have implications on his social status. Men on the other hand were expected to secure their role as household overseer and failure to do so resulted in social sanctioning. For example, a man whose wife was considered to yield too much power in the relationship might be described mockingly: ‘Sometimes the woman also gives orders in the house […] For that we call them [a] mandarina, because the woman is doing the man’s thing so that’s where the criticisms comes’ (33-year-old man, FGD 2, Sucumbíos).

Quantitatively we found a high co-occurrence of romantic jealousy and controlling behaviours. Compared to women who did not experience partner romantic jealousy, women who did experience it had 14 times the odds of also experiencing controlling behaviours (at time 1) (aOR: 14.47, 95% CI: 9.47, 22.12; p < 0.001). Women who reported controlling behaviours by their partner also had significantly higher odds of experiencing sexual intimate partner violence (aOR: 3.84, 95% CI: 1.21, 3.84) and combined physical and sexual intimate partner violence (at time 2) (aOR: 2.16, 95% CI: 1.21, 3.84). We found additional, significant associations between romantic jealousy, controlling behaviours and physical and sexual intimate partner violence that are further described below ().

Table 4. Adjusted odds ratios of male romantic jealousy and controlling behaviours (time 1) and physical and sexual intimate partner violence (time 2) (n = 1216).

Common triggers of romantic jealousy leading to intimate partner violence

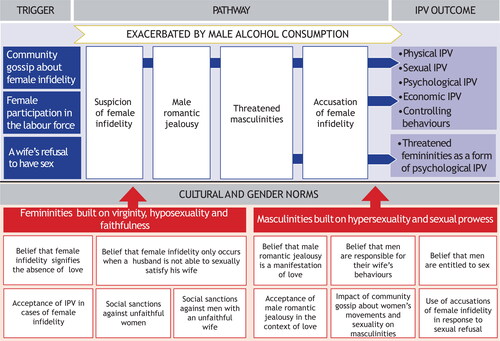

Three common triggers of romantic jealousy leading to physical, economic and sexual intimate partner violence were evident in the qualitative data: (1) community gossip about female infidelity, (2) female participation in the labour force, and (3) a wife’s refusal to have sex. All triggers were exacerbated by male alcohol consumption and partially triangulated by quantitative findings ().

Figure 2. Identified triggers of male romantic jealousy leading to intimate partner violence (IPV) again women, and underpinning cultural and gender norms.

Community gossip about female infidelity

Almost all participants said that they lived in constant fear that their family or neighbours would gossip about them. They reported that actions deviating from traditional gender roles could result in them becoming the subject of gossip. Moreover among men, not reacting to rumours of female infidelity could be perceived as a lack of manliness. Thus, men were pressured to respond to gossip quickly to maintain their social status and this sometimes took the form of physical intimate partner violence, especially if they had been consuming alcohol. For example, one participant shared an experience that had occurred after her husband heard gossip that her unborn child was not his: ‘He went to drink [alcohol…] He became more angry and I hid in the closet […] then he managed to hit me in the face’ (37-year-old woman, IDI, Carchi).

For women, a rumour that she had a sexual affair was a direct threat to her femininity and unfaithful women were stigmatised. Some women described adjusting their behaviours to protect against gossip. For example, one woman stopped leaving the house without her husband: ‘You know, if I go to the neighbours then they start with their gossip… so I don’t go out’ (33-year-old woman, IDI, Sucumbíos). Hence, gossip functioned as a mechanism of community control of women’s movements and sexuality.

No quantitative data were collected on community gossip about female infidelity, but there was partial quantitative evidence to support this pathway as controlling behaviours (at time 1) was significantly associated with physical intimate partner violence (at time 2) (aOR: 2.29, 95% CI: 1.31, 3.99) ().

Female participation in the labour force

Many women reported that their husband did not allow them to work outside of the home because they were jealous (a form of economic intimate partner violence). One woman explained, ‘He doesn’t want me to go… I tell him that I will go to the cafeteria to work, [and he says] that I have my lovers at the cafeteria’ (22-year-old woman, IDI, Sucumbíos). When women did work, returning home later than expected or gossip (trigger 1) about interactions with male colleagues could spark violence.

I was over there working in the coca company… they called [my husband]… [and said] that I was with another [man]… he came [to my workplace]… and punched me in the face, I remember that half of my eye turned red. (18-year-old woman, IDI, Sucumbíos)

Quantitatively, we found that women’s entry into the labour force between time 1 and time 2 was marginally associated with higher odds of partner romantic jealousy (aOR: 1.51, 95% CI: 0.98, 2.32), and partner romantic jealousy was marginally associated with higher odds of physical and sexual intimate partner violence (aOR: 1.57, 95% CI: 0.99, 2.47). These approached but did not attain statistical significance at the 0.05 level. Partner romantic jealousy partially mediated the relationship between women joining the labour force and physical or sexual intimate partner violence, and also approached but did not attain statistical significance at the 0.05 level (Indirect effect: aOR: 1.17, 95% CI: 0.99, 1.39) ().

A wife’s refusal to have sex

Many women described how they were expected to be sexually available to their husbands, and if they did not want to have sex there had to be a health-related reason to explain their refusal:

If I’m tired and he wants to [have sex] then […] he might think that ‘aha you have another [lover], that’s why you don’t want to sleep with me, obviously!’ That’s happened many times, but you need to speak and explain that you’re ill or something hurts, or you’re not feeling well and then he’ll understand. (46-year-old woman, FGD 1, Sucumbíos)

Participants reported that physically forcing one’s wife to have sex was considered machista and socially unacceptable although some women reported it occurring, especially after their husband had been consuming alcohol. Many women reported that if they refused sex then their partner would accuse them of infidelity, thereby coercing sex while avoiding the machista label. For example, a woman explained:

Sometimes I’m sleeping and I tell him I don’t want to [have sex with him] because I’m tired. He says I must have a lover, all sorts of things. So to let me sleep, to stop annoying me, I have sex with him. (40-year-old woman, IDI, Sucumbíos)

No quantitative data were collected on female sexual refusal, but there was partial quantitative evidence to support this pathway as partner romantic jealousy (measured as accusations of infidelity at time 1) was significantly associated with experiencing sexual intimate partner violence (at time 2) (aOR: 2.40, 95% CI: 1.12, 5.12) ().

Discussion

We found that male romantic jealousy is a barrier to partnered women’s safety, and social and economic independence. Traditional masculinities and femininities, and cultural and gender norms laid the foundation for the relationship between romantic jealousy and intimate partner violence against women.

In line with other literature from LAC, we documented that gender norms in northern Ecuador are changing as illustrated by the rejection of the machista label and moving away from the pillars of marianismo (Boyce et al. Citation2016; Fuller Citation2012), but many of the beliefs and attitudes associated with machismo and marianismo that facilitate the pathway from romantic jealousy to intimate partner violence prevail. Hence, our results suggest that in Ecuador structural, community-based interventions may be needed to provide positive role models of alternative masculinities (e.g. that focus on equitable household decision making and responsibilities) (Bourey et al. Citation2015; Casey et al. Citation2018), and that aim to address specific authoritarian behaviours directly (e.g. controlling where a woman goes or what she wears) instead of targeting the label of machista, which is already perceived unfavourably and as unrelatable.

Programming could also provide positive role models of alternative femininities that capitalise on emerging femininities that already coexist with marianismo but reject male romantic jealousy and controlling behaviours (Budgeon Citation2014; Salazar, Goicolea, and Öhman Citation2016). These could mitigate the emotional impact of accusations of female infidelity and increase women’s decision-making in the household and community to shift gendered power dynamics (Treves-Kagan, Maman, et al. Citation2020). Challenging gender norms in environments where violence is condoned can aggravate intimate partner violence, particularly in the short-term (Jewkes Citation2002); thus, gender synchronised interventions could work closely with men, couples and the community – emphasising the value of positive communication and trust in relationships (e.g. Kyegombe, Stern, and Buller Citation2022; Niolon et al. Citation2017) and increasing support for non-violent behaviours (Treves-Kagan, Maman, et al. Citation2020) – to avoid a backlash of increased intimate partner violence. Gender-transformative programming has shown to effectively reduce intimate partner violence at the community-level (Ellsberg et al. Citation2015), and our findings support evidence from Nicaragua (Ellsberg et al. Citation2020) that these results could be replicated in LAC.

Increasing women’s economic empowerment has been demonstrated to increase their agency and contribute towards gender equality (Ellsberg et al. Citation2015), but in line with past literature our findings suggest that women’s empowerment in the form of joining the labour force may increase intimate partner violence (Heise and Kotsadam Citation2015). Our findings highlight that in Ecuador the association between women joining the labour force and intimate partner violence is partially mediated by male romantic jealousy, thus economic empowerment interventions could provide an opportunity to discuss gender and male romantic jealousy to mitigate the risk of potential intimate partner violence backlash.

As found previously in LAC, participants generally conceptualised romantic jealousy as an overwhelming, powerful emotion that emanates from intense feelings of love (Tronco Rosas Citation2018). Programmatic approaches could target individual beliefs that romantic jealousy is synonymous with love through critical reflection and communication interventions and comprehensive sexuality and relationship education (Makleff et al. Citation2020). Our findings suggest that interventions should not aim to demonise or eliminate romantic jealousy, but instead decrease its weight and acceptability as a mechanism of controlling behaviours (Hart and Legerstee Citation2010) and highlight its role in precipitating intimate partner violence events (Kyegombe, Stern, and Buller Citation2022). Interventions that dismantle love-based narratives around romantic jealousy using mass-media could also be beneficial, as exposure has been correlated with controlling behaviours in relationships (Aubrey et al. Citation2013).

Findings from this study are consistent with the four pathways identified by Pichon and colleagues (Citation2020): (1) Men who suspect their partner of infidelity use physical and psychological intimate partner violence; (3) Men who anticipate partner infidelity use controlling behaviours and economic intimate partner violence; (4) Women experience accusations of infidelity as a form of psychological intimate partner violence; and (5) Women who anticipate male suspicion of their own infidelity experience sexual coercion. Our study highlights that in Ecuador female labour force participation is key in triggering accusations of infidelity via pathway three. A novel addition to the earlier review findings is the central role gossip plays in triggering pathway one, and more research is needed to determine in which other contexts this trigger applies.

We found that privately accusations of infidelity may be used by partners to coerce sex, while publicly accusations of infidelity made through community gossip may be used to maintain the gendered hierarchy, controlling women’s movements and access to employment, thereby increasing their social isolation and vulnerability to intimate partner violence (Capaldi et al. Citation2012; Mayorga Citation2012). Hence, measurements should clearly indicate who made the accusation of infidelity and whether it was made publicly or privately, as these represent different triggers and could have important programmatic implications.

Limitations

This study is not without its limitations. Firstly, quantitative indicators of romantic jealousy and controlling behaviours were each measured with one question, and more sensitive, robust measures are preferable. Furthermore, the qualitative topic guides did not include questions on gender norms, romantic jealousy and their relationship to intimate partner violence, but for the majority of participants these topics arose naturally. Data were collected in 2011 (quantitative) and 2013 (qualitative) and it is possible that gender norms and beliefs about romantic jealously and intimate partner violence have continued to change since then. Significant and measurable gender norms change, however, takes a long time and given this timeframe the data is likely still relevant and applicable to the current cultural context (Lennon et al. Citation2021). Lastly, the quantitative sample is representative of low-income households in Sucumbíos and Carchi, however, the triangulation of our results with mixed methods (when possible) and the existing literature increases our confidence in its transferability to the larger sample and Ecuadorian context.

Conclusion

Findings from this study suggest that individual, couple and community-level, gender-transformative programming that provides role models of alternative masculinities and femininities could be a promising approach to use in preventing intimate partner violence against women in Ecuador. More evidence is needed, however, to determine whether these interventions are effective. Additionally, while women’s economic empowerment has been demonstrated to contribute towards gender equality, findings from this study suggest that women joining the labour force may increase their risk of intimate partner violence, and this association is mediated by male romantic jealousy. Hence, empowerment programmes that provide the opportunity to discuss gender and male romantic jealousy could help mitigate the risk of potential intimate partner violence backlash. These and related interventions should consider the role of alcohol in exacerbating the triggers of violence and raise couples’ awareness of the link between patriarchal gender roles, male romantic jealousy and intimate partner violence.

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official positions of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine or the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Declarations of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Funding

This work was supported by an anonymous funder. The funder had no role in the design, analysis, and write-up of these results.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Agoff, C., C. Herrera, and R. Castro. 2007. “The Weakness of Family Ties and their Perpetuating Effects on Gender Violence: A Qualitative Study in Mexico.” Violence against Women 13 (11): 1206–1220.

- Aubrey, J. S., D. M. Rhea, L. N. Olson, and M. Fine. 2013. “Conflict and Control: Examining the Association Between Exposure to Television Portraying Interpersonal Conflict and the Use of Controlling Behaviors in Romantic Relationships.” Communication Studies 64 (1): 106–124.

- Barelds, D. P. H., and P. Barelds-Dijkstra. 2007. “Relations Between Different Types of Jealousy and Self and Partner Perceptions of Relationship Quality.” Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy 14 (3): 176–188.

- Bott, S., A. Guedes, M. M. Goodwin, and J. A. Mendoza. 2012. “Violence Against Women in Latin America and the Caribbean: A Comparative Analysis of Population-Based Data From 12 Countries.” Washington, DC: Pan American Health Organization. https://iris.paho.org/handle/10665.2/3471

- Bourey, C., W. Williams, E. E. Bernstein, and R. Stephenson. 2015. “Systematic Review of Structural Interventions for Intimate Partner Violence in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Organizing Evidence for Prevention.” BMC Public Health 15: 1165.

- Boyce, S., P. Zeledon, E. Tellez, and C. Barrington. 2016. “Gender-Specific Jealousy and Infidelity Norms as Sources of Sexual Health Risk and Violence Among Young Coupled Nicaraguans.” American Journal of Public Health 106 (4): 625–632.

- Budgeon, S. 2014. “The Dynamics of Gender Hegemony: Femininities, Masculinities and Social Change.” Sociology 48 (2): 317–334.

- Buller, A. M. 2010. “The Measure of a Man: Young Male, Interpersonal Violence and Constructions of Masculinities an Ethnographic Study from Lima, Peru.” PhD diss., London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine.

- Buller, A. M., M. Hidrobo, A. Peterman, and L. Heise. 2016. “The Way to a Man's Heart Is Through His Stomach?: A Mixed Methods Study on Causal Mechanisms Through Which Cash and In-Kind Food Transfers Decreased Intimate Partner Violence.” BMC Public Health 16 (1): 488.

- Capaldi, D. M., N. B. Knoble, J. W. Shortt, and H. K. Kim. 2012. “A Systematic Review of Risk Factors for Intimate Partner Violence.” Partner Abuse 3 (2): 231–280.

- Casey, E., J. Carlson, S. Two Bulls, and A. Yager. 2018. “Gender Transformative Approaches to Engaging Men in Gender-Based Violence Prevention: A Review and Conceptual Model.” Trauma, Violence & Abuse 19 (2): 231–246.

- Castillo, L. G., F. V. Perez, R. Castillo, and M. R. Ghosheh. 2010. “Construction and Initial Validation of the Marianismo Beliefs Scale.” Counselling Psychology Quarterly 23 (2): 163–175.

- Connell, R. W., and J. W. Messerschmidt. 2005. “Hegemonic Masculinity: Rethinking the Concept.” Gender & Society 19 (6): 829–859.

- Conway, J. A. 2013. “Lago Agrio (Nueva Loja), Ecuador: A Strategic Black Spot?.” MA diss., United States Army War College.

- Ellsberg, M., D. J. Arango, M. Morton, F. Gennari, S. Kiplesund, M. Contreras, and C. Watts. 2015. “Prevention of Violence against Women and Girls: What Does the Evidence Say?” The Lancet 385 (9977): 1555–1566.

- Ellsberg, M., W. Ugarte, J. Ovince, A. Blackwell, and M. Quintanilla. 2020. “Long-Term Change in the Prevalence of Intimate Partner Violence: A 20-Year Follow-up Study in León, Nicaragua, 1995-2016.” BMJ Global Health 5 (4):e002339.

- Flood, M. 2008. “Men, Sex, and Homosociality: How Bonds Between Men Shape their Sexual Relations with Women.” Men and Masculinities 10 (3): 339–359.

- Fuller, N. 2012. “Repensando el Machismo Latinoamericano.” Masculinities and Social Change 1 (2): 114–133.

- Gibbs, A., K. Dunkle, and R. Jewkes. 2018. “Emotional and Economic Intimate Partner Violence as Key Drivers of Depression and Suicidal Ideation: A Cross-Sectional Study among Young Women in Informal Settlements in South Africa.” PLoS One 13 (4):e0194885.

- Goicolea, I., A.-B. Coe, and A. Ohman. 2014. “Easy to Oppose, Difficult to Propose: Young Activist Men’s Framing of Alternative Masculinities Under the Hegemony of Machismo in Ecuador.” YOUNG 22 (4): 399–419.

- Government of Ecuador. 2018. “Comprehensive Organic Law to Prevent and Eradicate Violence Against Women [Ley Orgánica Integral para la Prevención y Erradicación de la Violencia de Género Contra las Mujeres].” https://oig.cepal.org/sites/default/files/2018_ecu_leyintegralprevencionerradicacionviolenciagenero.pdf

- Hart, S. L., and M. Legerstee. 2010. Handbook of Jealousy: Theory, Research, and Multidisciplinary Approaches. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

- Heise, L., and A. Kotsadam. 2015. “Cross-National and Multilevel Correlates of Partner Violence: An Analysis of Data from Population-Based Surveys.” The Lancet Global Health 3 (6):e332–e340.

- Hidrobo, M., J. Hoddinott, A. Margolies, V. Moreira, and A. Peterman. 2012. Impact Evaluation of Cash, Food Vouchers, and Food Transfers among Colombian Refugees and Poor Ecuadorians in Carchi and Sucumbíos. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute. https://documents.wfp.org/stellent/groups/public/documents/liaison_offices/wfp254824.pdf

- Hidrobo, M., J. Hoddinott, A. Peterman, A. Margolies, and V. Moreira. 2014. “Cash, Food, or Vouchers? Evidence from a Randomized Experiment in Northern Ecuador.” Journal of Development Economics 107: 144–156. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2013.11.009

- Hynes, M. E., C. E. Sterk, M. Hennink, S. Patel, L. DePadilla, and K. M. Yount. 2016. “Exploring Gender Norms, Agency and Intimate Partner Violence among Displaced Colombian Women: A Qualitative Assessment.” Global Public Health 11 (1-2): 17–33.

- INEC (Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas y Censos). 2019. “Encuesta Nacional Sobre Relaciones Familiares y Violencia de Género Contra las Mujeres (ENVIGMU).” Quito, Ecuador. https://www.ecuadorencifras.gob.ec/documentos/web-inec/Estadisticas_Sociales/Violencia_de_genero_2019/Boletin_Tecnico_ENVIGMU.pdf

- Jewkes, R. 2002. “Intimate Partner Violence: Causes and Prevention.” The Lancet 359 (9315): 1423–1429.

- Keating, C., S. Treves-Kagan, and A. M. Buller. 2021. “Intimate Partner Violence against Women on the Colombia Ecuador Border: A Mixed-Methods Analysis of the Liminal Migrant Experience.” Conflict and Health 15 (1): 24.

- Kyegombe, N., E. Stern, and A. M. Buller. 2022. “We Saw That Jealousy Can Also Bring Violence”: A Qualitative Exploration of the Intersections Between Jealousy, Infidelity and Intimate Partner Violence in Rwanda and Uganda.” Social Science & Medicine 292: 114593.

- Lennon, S. E., A. M. R. Aramburo, E. M. M. Garzón, M. A. Arboleda, A. Fandiño-Losada, S. G. Pacichana-Quinayaz, G. I. R. Muñoz, and M. I. Gutiérrez-Martínez. 2021. “A Qualitative Study on Factors Associated with Intimate Partner Violence in Colombia.” Ciencia & Saude Coletiva 26 (9): 4205–4216.

- Makleff, S., J. Garduño, R. I. Zavala, F. Barindelli, J. Valades, M. Billowitz, V. I. Silva Márquez, and C. Marston. 2020. “Preventing Intimate Partner Violence among Young People – A Qualitative Study Examining the Role of Comprehensive Sexuality Education.” Sexuality Research and Social Policy 17 (2): 314–325.

- Mayorga, M. N. 2012. “Risk and Protective Factors for Physical and Emotional Intimate Partner Violence against Women in a Community of Lima, Peru.” Journal of Interpersonal Violence 27 (18): 3644–3659.

- Niolon, P. H., M. Kearns, J. Dills, K. Rambo, S. Irving, T. Armstead, and L. Gilbert. 2017. “Preventing Intimate Partner Violence Across the Lifespan: A Technical Package of Programs, Policies and Practices.” Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/ipv-technicalpackages.pdf

- Pichon, M., S. Treves-Kagan, E. Stern, N. Kyegombe, H. Stöckl, and A. M. Buller. 2020. “A Mixed-Methods Systematic Review: Infidelity, Romantic Jealousy and Intimate Partner Violence against Women.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17 (16): 5682.

- Salazar, M., I. Goicolea, and A. Öhman. 2016. “Respectable, Disreputable, or Rightful? Young Nicaraguan Women’s Discourses on Femininity, Intimate Partner Violence, and Sexual Abuse: A Grounded Theory Situational Analysis.” Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma 25 (3): 315–332.

- Salovey, P., ed. 1991. “Envy and Jealousy: Self and Society.” In The Psychology of Jealousy and Envy, Chap. 12, 271–286. New York: Guilford Press.

- Treves-Kagan, S., S. Maman, N. Khoza, C. MacPhail, D. Peacock, R. Twine, K. Kahn, S. A. Lippman, and A. Pettifor. 2020. “Fostering Gender Equality and Alternatives to Violence: Perspectives on a Gender-Transformative Community Mobilisation Programme in Rural South Africa.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 22 (sup1): 127–144.

- Treves-Kagan, S., A. Peterman, N. C. Gottfredson, A. Villaveces, K. E. Moracco, and S. Maman. 2020. “Equality in the Home and in the Community: A Multilevel Longitudinal Analysis of Intimate Partner Violence on the Ecuadorian-Colombian Border.” Journal of Family Violence 1–14.

- Tronco Rosas, M. A. 2018. “Género y Amor: Principales Aliados de la Violencia en las Relaciones de Pareja que Establecen Estudiantes del IPN.” Mexico City, Mexico: Programa Institucional de Gestion con Perspectiva de Genero. https://www.ipn.mx/genero/materialesdeapoyo/articulo-violentometro.pdf

- UN Women. 2021. Ecuador. https://lac.unwomen.org/en/donde-estamos/ecuador#:∼:text=Ecuador%20is%20a%20country%20characterized,them%20women%20and%2049.6%25%20men

- UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees). 2020. Ecuador. http://reporting.unhcr.org/node/2543

- White, G. L. 1981. “Jealousy and Partner's Perceived Motives for Attraction to a Rival.” Social Psychology Quarterly 44 (1): 24–30.

- WHO (World Health Organization). 2021. “Violence against Women Prevalence Estimates, 2018: Global, Regional and National Estimates for Intimate Partner Violence against Women and Global and Regional Estimates for Non-Partner Sexual Violence against Women.” Geneva: World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241564625