Abstract

Intimacy has been identified as an important component of satisfying sexual activity in later life. While the existing literature reports that the importance of intimacy increases with age, the mechanisms behind this process have not been extensively researched. Even less is known about later-life sexual intimacy among women and men from former communist countries. This study explored the nuances of sex and intimacy by interviewing 50 Polish and Czech women and men aged 60 to 82. Data were analysed thematically using an inductive approach. Three main themes were developed to represent the extent to which intimacy was part of participants’ lives: 1) lifelong representation of sex as an intimate connection between individuals; 2) later-life shift towards intimacy-oriented sex for two main reasons: health-related necessities and a new relationship context; and 3) no intimacy whatsoever. The study findings indicate that a later-life refocus from an instrumental, penetrative-oriented view of sex towards a wider variety of intimate behaviours may be beneficial, not only for improving quality of sexual life, but also to gain new ways to express emotional connections between the partners.

Introduction

Research on sexuality in later life has received extensive attention, particularly in the last two decades. Thanks to this effort, sex has been shown to remain an important part of older adults’ lives with positive effects on their physical and psychological well-being (Buczak-Stec, König, and Hajek Citation2021; Smith et al. Citation2020). Many older adults continue to engage in various forms of sexual activity, either within monogamous relationships with a long-term partner or in a new relationship established in mid or later life (Erens et al. Citation2019; Karraker and DeLamater Citation2013; Ševčíková, Gottfried, and Blinka Citation2021). Relatedly, the literature suggests that closeness and intimacy may play a vital role in later-life sexual expression (Morrissey Stahl et al. Citation2019; Sandberg Citation2013). However, these have not been the subject of many studies. Thus, the present study sought to investigate how older people experience intimacy and how their experiences differ according to the cultural context. We undertake a qualitative, cross-cultural analysis of interview data from heterosexual older Czech and Polish people about trajectories of intimacy over the life course in order to understand how intimacy-related attitudes and behaviours affect their relationship and sexual functioning.

A multifaceted concept of intimacy is commonly equated with ‘closeness’ but also implies a more specific romantic or sexual dimension (Popovic Citation2005), leading to distinguishing two facets: emotional intimacy and sexual intimacy. Emotional intimacy has more connotations with feelings of love, closeness, sharing of feelings, connection with a partner, affirmation, and demonstrations of caring (Morrissey Stahl et al. Citation2019; Sinclair and Dowdy Citation2005). Sexual (physical) intimacy usually refers to acts of physical closeness, such as sensual touching, caressing, kissing and oral sex, which may accompany penetrative intercourse but do not rely on it to happen (Sandberg Citation2013; Hinchliff and Gott Citation2004). Such an understanding resonates with the erotic (non)intercourse scenarios described by McCarthy, Cohn, and Koman (Citation2020) in which ‘sensual, playful, erotic, and intercourse touch are all valued and introduce crucial dimensions of couple sexuality’ (301). Overall, there is still no uniform and generally accepted model or definition for the construct of intimacy because cultural, gender and age differences may lead to different understandings (Hook et al. Citation2003; Popovic Citation2005). For example, sexual interaction in young women has been found to more likely revolve around the theme of emotional closeness compared to men of the same age, who tend to treat sex and intimacy separately, although these gender differences are less pronounced in more permissive cultures (e.g. Meston and Buss Citation2007; Ridley Citation1993).

Recent literature suggests that, for many older adults, physical closeness, affection and intimacy may be equally or more important than sexual activity per se (Fileborn et al. Citation2017; Sandberg Citation2013), and that experiencing closeness and intimacy improves the quality of their relationship and potentially sexual functioning (Erens et al. Citation2019). This is particularly important given that staying in a long-term relationship does not always guarantee continuity of sexual activity in later life. Higher age, a longer marriage, and poor physical health (one’s own or the partner’s) may lead to the avoidance of sexual interaction or to a complete cessation of sexual activity among older people (Carvalheira et al. Citation2020; Hinchliff et al. Citation2020). However, research also indicates that there are individuals who adjust their sexual practices in response to the challenges of health-related sexual difficulties by revising the meanings associated with penetrative sex and by searching for alternative intimate behaviours to sexual intercourse, such as sensual touching, caressing, kissing and oral sex (Gore-Gorszewska Citation2021a; Hinchliff and Gott Citation2004).

In this respect, several studies provide evidence that an individual’s attitudes towards intimacy are not fixed but may become more affirmative in late adulthood. For example, a recent study among US women aged 57-91 observed that, while all participants valued intimacy in their relationships (i.e. intimacy in a broad sense), most acknowledged that its importance over sexual passion grew over time (Morrissey Stahl et al. Citation2019). Similarly, older Swedish men recounted that, while their sexual activity at a younger age was predominantly focused on intercourse, at the time of the interview they more often engaged in sensuality-oriented intimate behaviours (Sandberg Citation2013).

Nonetheless, Fileborn and her colleagues (2017) critically point out that not all changes in sexual practices and adjustments are easily acceptable for older people. Some of them, following an internalised hierarchical definition of sex, still treat sexual intimacy as a ‘lesser’ form of sexual activity compared to the gold standard of heterosexual penetrative intercourse. For example, some couples reported being 'forced’ to modify their sexual behaviour towards intimacy due to situational factors and health issues such as the progressive dementia of one partner (Holdsworth and McCabe Citation2018). Moreover, some older individuals differentiate sexual intimacy from emotional intimacy and perceive these two dimensions contribute in different ways to the quality of their relationship and sexual life (Gore-Gorszewska Citation2021a; Morrissey Stahl et al. Citation2019).

The existing qualitative studies that explore intimate behaviours in the ageing population, although undoubtedly informative, rarely address intimacy directly and tend to raise this topic alongside other aspects of later-life sexuality (Fileborn et al. Citation2017). They most often focus on specific issues (e.g. the couple’s intimacy in relation to caregiving; Holdsworth and McCabe Citation2018); limit their sample to specific subgroups, such as long-term married couples (Hinchliff and Gott Citation2004; Ménard et al. Citation2015); or explore only one gender narratives without providing a joint perspective on possible gender variations in later-life intimacy (Fileborn et al. Citation2017; Sandberg Citation2013). In addition, the majority of studies investigate the topic in Western cultures (e.g. Australia, Canada, Sweden, UK), leaving potential sociocultural specificities unaddressed. Given these limits and diverse understanding of later-life intimacy, we propose to add a cultural perspective while jointly studying older female and male experiences with sexual and emotional intimacy.

Very few studies to date have provided insight into the sexuality and intimacy of older adults with a more conservative background such as those, for example, from post-communist European societies (see: Gore-Gorszewska Citation2021a; Ševčíková and Sedláková Citation2020). To contextualise, Central and Eastern European countries are, in general, considered less egalitarian, less liberal and less sexually permissive than their Western counterparts (Herzog Citation2011). Still, despite many similarities in the political and historical context, these societies are not uniform with regard to the public discourse on sexuality that prevailed before the collapse of communism (Herzog Citation2011; Kościańska Citation2016). For instance, during communist times, Czechoslovak gynaecologists tried to demythologise both the climacteric and ageing women’s sexuality, and they were very much influenced by Master’s and Johnson’s ground-breaking study of human sexuality. Czechoslovak experts tended to provide recommendations on sexual techniques, while accentuating female self-actualisation and independence, which could have led to the enhanced quality of the sex lives of older Czech women (Bělehradová and Lišková Citation2021). Although Masters and Johnson’s work had an impact on sexological expertise in other Central European socialist countries, such as East Germany and Hungary, in Poland public discourse on sexuality was grounded in Catholic morality and heavily influenced by guidance from popular sexology experts (Ingbrant Citation2020). Their work, although informative and progressive in some respects, linked sexual pleasure and fulfilment to traditional gender roles, stating that women’s emancipation was the source of a double burden and that intercourse is the proper aim and culmination of the sexual act (Kościańska Citation2016).

Raising the issue of cultural nuances in the sexual discourses within which current older adults were socialised, this study aims to explore trajectories of intimacy and later-life intimacy among older women and men from two Central European post-communist countries, the Czech Republic and Poland. Both countries share a communist past, during which they underwent specific social changes, such as state-imposed secularisation, socialist emancipation, the repression of pro-democratic movements, and an emphasis on pro-family politics (Lišková Citation2018). Currently, both countries are relatively homogenous with respect to the ethnicity of their populations and are decidedly heteronormative, yet the level of religiosity and the position of the Catholic Church is significantly different. Poland is considered one of the more religious countries in Europe, with a strong emphasis on pro-family values (Gwiazda Citation2021). The Czech Republic is one of the most secular and atheist among European countries and Catholic values play a less prominent role in its society (Hamplová Citation2013). The present research embarks on the cross-cultural analysis of qualitative interview data from older heterosexual Czechs and Poles about intimacy and its changes across their life course with the aim of understanding how intimacy-related attitudes and behaviours affect older individuals’ relationships and sexual functioning.

Materials and methods

Participants and recruitment

This study is based on an analysis of 50 semi-structured interviews with individuals aged 60 to 82 from the Czech Republic (n = 20, 13 women, median age = 65) and Poland (n = 30, 16 women, median age = 70). The sample was diverse in terms of relationship status, educational background, and occupational status ().

Table 1. Sample characteristics (N = 50).

Gender Current Relationship Status

Czech participants were recruited at a hospital through a preventive cognitive health programme designed for ageing people, and subsequently through chain-referral technique. Polish participants were recruited through posters distributed at health centres, pharmacies, University of the Third Age venues, and in a retirement home in two cities in southern Poland.

Informed consent to conduct and audiotape the interviews was obtained from the participants. All study procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Masaryk University in the Czech Republic and Jagiellonian University in Poland.

Data collection

In-depth, semi-structured interviews were conducted face-to-face by the authors in the Czech Republic and Poland (AŠ and GGG, respectively) between 2017 and 2019. Each interview lasted between one and three hours and was audio recorded. Being part of a larger qualitative study that explored the sexuality of older adults (in both countries separately), the interview guides were purposefully broad and included a set of questions across several domains related to the participants’ sexual lives. Although the Czech and Polish interview structure differed in the sequence of questions asked during interviews and in the wording/phrasing of questions (while their meanings were consistent across countries), both focused on mapping sexual trajectories, changes in sexual expression across the life course, and the sources and outcomes of the changes, and resulted in the aggregation of comparable data. Detailed information about each study scope and procedures can be found elsewhere (Gore-Gorszewska Citation2021a; Ševčíková and Sedláková Citation2020).

Both authors identify as white, young women, who are trained in psychology and psychotherapy. Both are knowledgeable about the specifics of later-life sexuality (including sexual difficulties) and share the cultural background of their respective countries. These aspects facilitated the establishment of respectful atmosphere during the interviews, attenuating the age-gap, and understanding the notions and contexts raised by the interviewees. Female participants indicated that the gender similarity allowed them to be more open, while men claimed candour because they considered the interviewer to be a 'truth-seeking researcher’.

Data analysis

The main question asked by the current study analysis was: “How do older adults reflect on intimacy and its role in their sexual lives”. The analysis of the transcribed interviews was guided by a form of thematic analysis, modified to adhere to the cross-country comparison of the two data sets. Thematic analysis offers a flexible and useful research tool for identifying, analysing and reporting patterns (i.e. themes) in qualitative data (Braun and Clarke Citation2006). In this study, we used a bottom-up (inductive) approach and followed the steps required to ensure the quality of the analysis and the trustworthiness of its findings. The authors regularly discussed and negotiated each analytical step and the related outcomes.

Both the authors familiarised themselves with the data collected in their own language by repeatedly reading the transcripts, taking notes, and writing down their initial ideas. Then they proceeded to coding, based on notions that emerged from the interviews themselves while keeping the research question in mind. After a sub-sample of transcripts (six Czech, eight Polish) had been coded, the authors began to identify patterns across the data and generate a preliminary set of descriptive candidate themes. These were translated into English, together with the corresponding, illustrative quotations, and then discussed between the authors, who shared their initial notes and clusters of emerging themes such as ‘sex-related expectations in later life’ and ‘life-long experiences with sex and expressions of closeness’. Another round of coding for the subsequent sub-sample of transcripts was conducted in a similar fashion, accompanied by recurrent discussion between the authors, resulting in the identification of dominant and unique patterns.

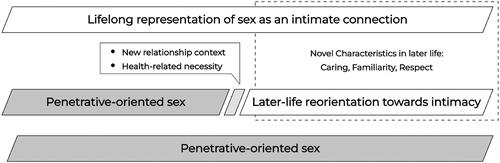

The reviewed themes were then organised into a preliminary thematic map, which was used by both authors to navigate the analysis of the remaining transcripts. By going back and forth between coding and reviewing the themes, the thematic map was modified to include new notions such as ‘more intimate contacts thanks to male strategies to maintain sexual activity when dealing with age-related health problems’. The themes’ contents and previous transcripts were then reviewed by both authors. Finally, the authors discussed the themes and their structure and reflected on the similarities and differences they had identified within the data until agreement was reached for the final thematic map (see ).

Findings

By exploring nuances of sexual and emotional intimacy in the accounts of older adults from the Czech Republic and Poland, three general themes that represent the extent to which intimacy was part of the participants’ lives were developed: i) lifelong representation of sex as an intimate connection between two people; ii) later-life shifts towards intimacy-oriented sex; and iii) no intimacy whatsoever. We also found that, in both the samples, intimacy in older age had gained novel and relevant characteristics that are captured in the following themes: (a) caring about each other; (b) familiarity; and (c) respect. Several cultural variations were identified with respect to the extent of participants’ willingness to practise intimacy-oriented sex.

Lifelong representation of sex as an intimate connection between two people

Some women and men shared the perspective that sex and intimacy are inseparable, with intimacy pivotal in sexual encounters. A number of participants had always considered sex not in terms of instrumental, penetrative intercourse, but as a variety of affectionate behaviours that were expressions of the intimate connection between two partners in love: ‘Something that happens between two people who have this special bond’ (M67-PLFootnote1). Another participant explained that throughout her whole life physical closeness had been so tightly linked to emotional and psychological closeness, that she could not imagine one without another: ‘I have it [sex] connected with that psychic closeness … I can’t imagine that I would be mentally close to someone and at the same time it wouldn’t work physically’ (W62-CZ). In this context, partnered sex provides older people with the sense of unity and it is the ultimate way of confirming closeness and exclusivity between them.

Interestingly, in the Polish sample, we observed a disjuncture between an individual’s perception of sex as an intimate connection between two people and the extent to which some participants had experienced it. One woman explained that she had always had ‘these romantic ideals about sex as a special, sublime act, based on deep emotions and closeness, gentleness and the right atmosphere’ (W66-PL), but she was unable to share such a connection with her husband, for whom sex was purely instrumental, focused on penetration and satisfying his sexual needs. Her narrative resonated with the accounts of several other Polish women and men, who admitted that their longing for intimacy-oriented sexual contact was not possible due to an unfavourable relationship context.

Later-life shift towards intimacy-oriented sex

Many participants in the study reported that, at some point in their lives, they experienced a change in their perceptions of intercourse, intimacy, and their joint role in a satisfying sexual relationship. While recounting that their younger years were dominated by a rather instrumental approach to sexual activity and a focus on penetrative sex, with age, our interviewees opened up to the possibility that other forms of sexual expression could satisfy their needs. A 71-year-old female interviewee explained how she currently saw intimacy and closeness as central to her relationship: ‘I believe the act of being together is the essence of sex. Bodies naked or not, penetration or not, but together. This is what matters now’ (W71-PL). It is worth noting that similar comments were made by male participants, as in this case: ‘[Intimacy] is a part of life. It’s enriching. You feel like you are with your wife, and you don’t have to have sex. You just lie together and simply make love’ (M63-CZ). Akin to this, many other men elaborated on their later-life refocus from an instrumental view of sex to a broader variety of sexual, non-coital expressions.

Two main reasons were identified as drivers for this change: health-related necessity and new-relationship context. For some participants the shift was induced by necessity – when they faced age-related sexual problems, such as post-menopausal discomfort or erectile difficulties during penetrative sex. One male interviewee, who admitted having problems maintaining an erection, referred to a talk show in which an older Czech photographer, Jan Saudek, said that he used oral sex to deal with his erectile problems in the context of having a much younger wife: ‘Mr. Saudek replied that, so far, he has been licking [his way] out of it [a Czech euphemism for oral sex]. So, some women like it very much’ (M63-CZ). This participant reported using the same strategy (i.e. orally satisfying his younger female partner), especially when having difficulty in achieving a firm erection. At the same time, he acknowledged that he benefitted from his new approach towards sex. This and other similar narratives conform to the pattern we observed in this study: replacing penetrative sex by other sexual practices was initially considered by some participants as merely as a coping strategy in the face of health-related sexual problems. Over time, however, these gestures of intimacy became cherished as important and enriching elements of sexual life.

The second reason for developing a new, intimacy-oriented perspective towards sex was related to a relationship-status change. This was a turning point in which entering a new relationship at older age and resuming sexual activity may give rise to new patterns of sexual expression and a new interpretation of the sexual act. An illustrative quote comes from a woman who discovered non-penetrative forms of physical intimacy only after meeting a new partner at the age of 58: ‘In my marriage, well, I’d never experienced it (…) He [the new partner] is very open. Cuddling and being close is more important for him than just sex. (…) You could say that together we discovered how great it is to be intimate’ (W70-PL). She found this new way of being sexual very rewarding and regretted that her earlier sex life had been devoid of it, which was a widely shared notion of many women and men in this study.

The shift towards valuing intimacy above other forms of sexual contact was nuanced among participants, and our analysis revealed two distinct approaches within this theme. Some interviewees referred to penetrative sex as a pleasurable, albeit an optional part of their sex lives. While occasionally including it in their sexual repertoire, they were adamant that non-coital, intimate sexual activities—such as kissing, petting and oral sex—became more important, gratifying and enriching: ‘We take it slowly. We talk, we hug, stroke and kiss, all that. (…) Occasionally we have intercourse, but more often we are happy without it’ (M66-PL). Other participants were more ‘radical’ in their approach and elaborated on how sexual activity has given way to gestures of purely non-sexual physical intimacy, which became central in their later-life relationships. This was illustrated by a woman who described moments of intimate contact with her husband: ‘It is enough for me to just hug, to lie down and hold hands. It satisfies me… sex doesn’t come in the first place. (…) A relationship, understanding, those things are far more important’ (W67-CZ). She stressed that these gestures were highly valued while being performed with no sexual intentions (not as an invitation to sex or foreplay) but simply for the feeling of being emotionally intimate together.

No intimacy whatsoever

In contrast to the approaches to sex and intimacy presented above, several male participants, exclusively in the Polish sample, provided a distinctly different view. According to them, only penetrative sex mattered, while other forms of sexual expression were ‘unnecessary fuss and distraction’ and emotional intimacy is redundant and overrated, ‘soap-opera-inspired’ (M67-PL). These men were adamant in their strongly physiological accounts of the instrumental role of sex in satisfying a man’s need, a view that had persisted since their youth. One interviewee straightforwardly claimed that, should his financial status allow it, he would ‘seek girls who needed a sponsor (…) or visit brothels to have sex with young, pretty girls’ (M75-PL) to fulfil his needs. Notably, the participants who represented this approach unanimously complained about the challenges they encountered, such as frequent refusals from women and difficulties in performing penetrative sex due to health-related problems: ‘I often struggle, you know, my [erectile] problems. It is frustrating, because finding a woman is a challenge to begin with. And then, when I have an opportunity, it doesn’t work!’ (M67-PL). Yet, despite these difficulties and related distress, these same men seemed to be unwilling to revise their approach towards later-life sex and consider non-coital, more intimate forms of sexual expression as an alternative.

While two male accounts within this theme were rid of any notion of intimate experiences or any desire for it, two other Polish narratives revealed ambiguity regarding the non-existence of the need for intimacy. For example, one participant who had had numerous sex partners in the past and claimed that all he ever wanted and all he currently needed was to have intercourse and to ejaculate, in such a way recalled his best sexual encounter: ‘It was with that one [name] I’ve told you about. In terms of satisfaction, well, it was definitely with her, because… I had this… feeling’ (M76-PL). Even when prompted, he was unable to specify this ‘feeling’, but he claimed: ‘This feeling… yes. It made a difference, that it was with her’. This quotation suggests that the need for an intimate connection with a sexual partner may exist, but is either difficult to articulate or not recognisable, effectively preventing this man and like-minded men from seeking for it or acting upon it.

Intimacy and caring about each other

For many participants who acknowledged the importance of intimacy, physical contact with a partner seemed to gain additional value in later life. When participants were touched, kissed, caressed or brought to orgasm, they interpreted these acts as gestures of not only being loved, but also of being cared for by someone important to them: ‘Now [sex] is very unimportant [due to progressive vaginal atrophy]. I feel it’s not about sex and orgasms but about intimacy between the partners, so I can’t completely trivialise [sex] like that. Because he massages me, strokes me, he caresses me, yeah, when, when I want to, or when he sees that I'm sad’ (W68-CZ). This same woman emphasised how, through such gestures of intimacy, her partner communicated his care for her emotional well-being. Her statement points to the scope of caring that can be expressed and experienced in later life, suggesting that intimacy conveyed via physical contact plays a crucial role in confirming the importance of older partners and bonding to each other.

Another, more distinct aspect of caring about the partner – consideration for their sexual needs – was also observed in this study. Specifically, male participants indicated that in later life they had, often for the first time, experienced a genuine desire to care about their female partner’s sexual pleasure. When they followed their partner’s wishes and began to engage in various forms of intimacy at the expense of penetrative sex, they found themselves experiencing gestures of sexual and emotional intimacy that they themselves found gratifying: ‘I used to think that if I didn’t have intercourse, why should I even meet with a woman. There was no point. Well, this has changed. (…) [with a current partner] we can hug, kiss, talk for hours, fall asleep, and wake up together and that’s it (…). It is amazing’ (M66-PL). Other male participants stressed how much, at present, they enjoyed such gestures of intimacy in the relationship context and how meaningful they found them, even if they had begun mainly out of consideration for the partner.

Intimacy and familiarity

The second important component in the portrayal of later-life intimacy was the reciprocal relationship between intimacy in a relationship and mutual familiarity of the partners. If built over the life course, this seemed to help maintain sexual intimacy in long-term couples: ‘You already know what to touch, what to do to make it work, to make it pleasurable’ (M61-CZ). This acquired knowledge supported older couples to stay sexually active and exchange pleasurable sex in later life.

In the case of new relationships, mutual understanding and familiarity seemed to legitimise the incorporation of sexual behaviour into a relationship established in later life: ‘I suddenly came across a person with whom I fit together so well emotionally, and we understand each other in so many ways, so this [erotic] aspect of life, as it turned out, is not a problem at all. It’s only a natural extension’ (W70-PL). In this context, deepening mutual familiarity at a physical level was spontaneous and effortless. It was a novel experience for many interviewees who emphasised how engaging in physical intimacy fostered a change in thought ("we talk about everything") and led to an even better understanding between partners, thus strengthening their bond and facilitating greater physical closeness.

In relation to sex life in older age, it seemed to be particularly valuable for sexual pleasure that individuals began to appreciate their understanding of their partner’s body, sexual wishes, and preferences: ‘After three years of no partnered sex, it was surprising, because I just thought it might not work, that I couldn’t, and so on. But [it worked out well] because he was, as a partner, so sensitive that he knew more about my body than I did’ (W64-CZ). Some respondents considered the growing familiarity with partner’s body a revelation and life-changing experience, as they had not had the opportunity to encounter this level of connection and understanding with their partners in past relationships.

Intimacy and respect

In terms of the novel characteristics of later-life intimacy, female Polish participants voiced a strong connection between intimacy and respect. Feeling respected as a woman and being treated as an equal partner was particularly prominent in their narratives and was mentioned as paramount to engagement in sexual behaviour in later-life. Gestures of intimacy offered by a male partner were considered to be proof of this respect: ‘I feel secure and safe with him, as I know he respects me as a person and a woman, but not ‘his woman’. My wishes are important to him – I can feel it – and it makes intimacy so easy’ (W66-PL). This sentiment resonates with the accounts of women who perceived intimate behaviours in a relationship based on mutual respect to be meaningful and non-negotiable in later-life, often in contrast to their past experiences, when sexual activity was more instrumental and served different reasons, such as marital duty, procreation and satisfying the husband’s needs, and for that reason often lacked the component of physical and emotional intimacy.

Discussion

Drawing on historical research on sexuality in former communist countries (Herzog Citation2011; Kościańska Citation2016; Lišková Citation2018), this study used a cultural perspective to analyse older Czechs’ and Poles’ narratives about intimacy and its changes across the life course. The aim was to understand how intimacy-related attitudes and behaviours evolved and how they affected older individuals’ relationship and sexual functioning, while taking into account their sociocultural background.

In our analysis, we distinguished three different intimacy trajectories in respondents’ lives. In general, the less pragmatically sex was perceived (i.e. via a focus on physiological need, reproduction, and one’s own pleasure over the affectionate aspects of sex), the more intimacy was present. For some older adults, intimacy had been an integral part of sex throughout their lives; for others, new health and relationship conditions resulted in a later-life shift towards intimacy-oriented sex; and yet another group of participants maintained their lifelong representation of sex exclusively as intercourse, without the need for intimacy. These latter two trajectories of intimate expressions may point to the extent to which participants were socialised according to the traditional norms of masculinity, femininity and notions of proper sexual behaviour, with strongly accentuated gendered sexual roles within a relationship (e.g. norms for bearing children and satisfying the man’s sexual needs; Gore-Gorszewska Citation2021a; Kościańska Citation2016; Lišková Citation2018).

The dominance of traditional sexual norms and their negative impact on later-life sexuality is perhaps most visible in the accounts of a group of male interviewees who rejected acts of intimacy entirely, considering them superfluous and unnecessary. Their lifelong attitude escapes even the hierarchical definition of sex proposed by Fileborn et al. (Citation2017) because, for these men, nothing but sexual intercourse counted as sex. The fact that the ‘No intimacy whatsoever’ trajectory was present in only Polish male narratives, while absent in the Czech sample, may be attributed to some extent to the gendered sociocultural norms for sexual conduct and masculinity that prevailed at the time in communist, largely traditional Poland. By contrast to Czechoslovakia (currently Czechia and Slovakia), where female self-actualisation and independence was promoted by sexology experts and resonated in state policies (Bělehradová and Lišková Citation2021), the official communist party line in Poland was grounded in patriarchal tropes, reinforced by traditional Catholic Church values, and bolstered by the discourse of Polish sexologists, whos work emphasised traditional gender roles and ‘natural differences’ between women and men (Gal and Kligman Citation2000; Kościańska Citation2016). In this respect, for some men from a conservative background, intimacy may be difficult or impossible to incorporate into the male self-concept (Prager and Roberts Citation2004) because of the disjuncture between intimate behaviours and societal views of strong, dominant masculinity. It is worth acknowledging that this observed tendency could also be apparent in men from other cultural settings that stress traditional, performance-oriented ideals of sex (Fileborn et al. Citation2017; McCarthy, Cohn, and Koman Citation2020; Traeen et al. Citation2019).

Notably, the penetration-focused attitude seemed to persist among some older men, not only despite the intimacy-oriented expectations of their potential female partners, but also despite experiencing dissatisfaction with the quality of current sex life and frustration due to erectile problems. This may illustrate the negative health-related consequences of holding entrenched conservative beliefs about sexual conduct in later life. Given that in older age the prevalence of somatic illnesses, including sexual problems, increases (Traeen et al. Citation2017), and the fact that many older individuals, particularly in more traditional cultural contexts, struggle with reaching out for professional help (Gore-Gorszewska Citation2020), placing less emphasis on penetration and more on the intimate components of sex could provide a much needed solution for maintaining a satisfying sex life despite naturally occurring health-related sexual problems. In addition, because older adults typically identify primary care physicians as their primary source of help for sexual difficulties (Hinchliff et al. Citation2020), healthcare professionals should consider the sociocultural context of internalised sexual norms as a factor that potentially influences sexual behaviour in later life when offering support to their older patients.

Elaborating on previous findings about the increasing role of intimacy in later life (Morrissey Stahl et al. Citation2019; Sandberg Citation2013), our study identified re-partnering and a health-related necessity as the main factors that drive the shift towards intimacy-oriented sex. These two disruptive conditions seem to represent turning points that provide older people with an opportunity to question and reframe their life-long perspective on sexual expression. According to Carpenter and DeLamater (Citation2012), certain transitional moments may dramatically alter sexual expression and require the negotiation of new forms of sexual behaviour (i.e. adopting or rejecting sexual scripts and the socially learned sets of guidelines that govern people’s sexual lives). Also, a lack of societal expectations to engage in penetrative sex after entering a new relationship in later life has been voiced by older women as liberating (Gore-Gorszewska Citation2021b). Therefore, it may be plausible that the lack of emphasis on intercourse in newly formed later-life relationships may release older adults from the assumed necessity of following a gold standard of heterosexual intercourse, and thus create an opportunity to develop, practise and appreciate intimate closeness or to appreciate intimacy as a source of pleasure and comfort (Fileborn et al. Citation2017; Gore-Gorszewska Citation2021a; Ševčíková and Sedláková Citation2020).

The present study has also identified caring by the partner as a prominent category, accentuated in many narratives as emerging at older age. We propose that caring could be interpreted on several levels. Firstly, gestures of sexual intimacy can be seen in terms of the time and attention given to the well-being of the partner, which signals their importance. This facet of intimacy resonated particularly strongly in the narratives of the interviewed women who, according to traditional norms, have been socialised into the dominance of penetrative sex to serve the satisfaction of male sexual needs (Gore-Gorszewska Citation2021a). In their opinion, gestures of intimacy made them feel empowered and important to their partners, who — instead of having their needs met through sexual intercourse — were attentive to them. Secondly, we can interpret caring for a partner’s sexual needs as a beneficial activity in terms of the satisfaction that is experienced when a partner feels sexual pleasure in response to the other’s actions. Particularly prominent here was the voice of male participants, for whom this was a novel experience in late adulthood. The focus on male sexual satisfaction (while ignoring the female partner’s pleasure), practised earlier in life, was likely the result of following traditional sexual scripts and gendered sex roles that were modelled at home and reinforced at the societal level. Although Czech sexology – and state policies – were more focused on female sexuality than Polish ones, the centrality of penetrative intercourse among the older generation has been preserved until today (Steklíková Citation2014). This may explain why shifting the attention from male to female sexual pleasure was perceived by participants as such a novelty. Lastly, care, as an emphasised aspect of intimacy, may be unique to later-life sexuality. Specifically, the theory of socioemotional selectivity proposes a reorientation from pragmatic towards emotional goals at older age (Carstensen, Isaacowitz, and Charles Citation1999). This refocus may facilitate enriching later-life intimacy with a dimension of caring.

The results of the study support the existing literature on sexual intimacy with the three intimate trajectories and identified turning-point moments, potentially contributing to a more comprehensive understanding of how the role of intimacy develops/changes in late life. On a practical level, and in line with the clinically oriented Good Enough Sex model (McCarthy, Cohn, and Koman Citation2020), which promotes healthy couple sexuality and the reinforcement of relationships, the implications of our results include the benefits of integrating intimacy and eroticism in maintaining a satisfying sexual life in late adulthood. While intimacy can help in managing age-related changes in sexual functioning in older age, modifications to one’s sexual repertoire can also lead to enrichment and growth, rather than being limited to counteracting sexual problems. More testimonies about the positive outcomes derived from the change towards intimacy-oriented sex should be publicly communicated and incorporated into guidebooks and other forms of support on later-life sexuality.

Limitations

Although the main strength of this study was that it provides novel cross-cultural insights on intimate trajectories in later life, several limitations should be considered. The article draws on findings from two studies that were initially conducted separately. This led to some unavoidable discrepancies. For example, the sub-samples were not entirely homogenous – Czech participants were smaller in number and slightly younger. Also, the interview guides were not identical, specifically in terms of the wording of questions and their sequence during the interview. Nonetheless, given that distinct patterns were identified across the sample, the narratives collected in both countries correspond in terms of the content. Finally, the observed nuances in intimacy-related attitudes and behaviours may be, to some extent, attributed to recruitment bias (i.e. participants’ self-selection) and the voices of less forthcoming older adults may be under-represented.

Conclusion

To conclude, this study examined and identified several ways in which intimacy was perceived and exercised in older adults’ lives, with an emphasis on the potential influence of the sociocultural context and societal norms on sexual conduct. The results indicate that a later-life refocus from an instrumental, penetrative-oriented view of sex towards a wider variety of intimate behaviours occurs in traditional cultures, and may be beneficial, not only in terms of improved the quality of sexual and relational life, but also with respect to older individuals learning new ways to bond and connect with their partners.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank participants for sharing their intimate experiences and reflections.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Man, aged 67, from Poland. Interviewees coded by their gender (man/woman), age and country of origin (Poland/Czech Republic).

References

- Bělehradová, A., and K. Lišková. 2021. “Aging Women as Sexual Beings. Expertise Between the 1950s and 1970s in State Socialist Czechoslovakia.” The History of the Family 26 (4):562–582. doi:10.1080/1081602X.2021.1955723

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2):77–101. DOI10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Buczak-Stec, E., H.-H. König, and A. Hajek. 2021. “Sexual Satisfaction of Middle-Aged and Older Adults: Longitudinal Findings from a Nationally Representative Sample.” Age and Ageing 50 (2):559–564.

- Carpenter, L., and J. DeLamater. 2012. “Studying Gendered Sexuality Over the Life-Course: A Conceptual Framework.” In Sex for Life: From Virginity to Viagra: How Sexuality Changes throughout our Lives, edited by Laura Carpenter and John DeLamater, 155–178. New York: New York University Press.

- Carstensen, L., D. Isaacowitz, and S. Charles. 1999. “Taking Time Seriously: A Theory of Socioemotional Selectivity.” The American Psychologist 54 (3):165–181. DOI:10.1037/0003-066X.54.3.165

- Carvalheira, A., C. Graham, A. Stulhofer, and B. Traen. 2020. “Predictors and Correlates of Sexual Avoidance Among Partnered Older Adults Among Norway, Denmark, Belgium, and Portugal.” European Journal of Ageing 17 (2):175–184.

- Delamater, J. 2012. “Sexual Expression in Later Life: A Review and Synthesis.” Journal of Sex Research 49 (2–3):125–141.

- Erens, B., K. Mitchell, L. Gibson, J. Datta, R. Lewis, N. Field, and K. Wellings. 2019. “Health Status, Sexual Activity and Satisfaction among Older People in Britain: A Mixed Methods Study.” Plos One 14 (3):e0213835.

- Fileborn, B., S. Hinchliff, A. Lyons, W. Heywood, V. Minichiello, G. Brown, S. Malta, C. Barrett, and P. Crameri. 2017. “The Importance of Sex and the Meaning of Sex and Sexual Pleasure for Men Aged 60 and Older Who Engage in Heterosexual Relationships: Findings from a Qualitative Interview Study.” Archives of Sexual Behavior 46 (7):2097–2110.

- Gal, S., and G. Kligman. 2000. The Politics of Gender After Socialism. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Gore-Gorszewska, G. 2020. “Why Not Ask the Doctor?’ Barriers in Help-Seeking for Sexual Problems among Older Adults in Poland.” International Journal of Public Health 65 (8):1507–1515.

- Gore-Gorszewska, G. 2021a. “What Do You Mean by Sex?’ A Qualitative Analysis of Traditional Versus Evolved Meanings of Sexual Activity Among Older Women and Men.” Journal of Sex Research 58 (8):1035–1049.

- Gore-Gorszewska, G. 2021b. “Why Would I Want Sex Now?’ A Qualitative Study on Older Women’s Narratives on Sexual Inactivity as a Deliberate Choice.” Ageing and Society, 1–25. doi:10.1017/S0144686X21001690

- Gwiazda, A. 2021. “Right-Wing Populism and Feminist Politics: The Case of Law and Justice in Poland.” International Political Science Review 42 (5):580–595.

- Hamplová, D. 2013. Náboženství v české společnosti na prahu 3. Tisíciletí. Prague: Karolinum Press.

- Herzog, D. 2011. Sexuality in Europe: A Twentieth-Century History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hinchliff, S., A. Carvalheira, A. Štulhofer, E. Janssen, G. M. Hald, and B. Traeen. 2020. “Seeking Help for Sexual Difficulties: Findings from a Study with Older Adults in Four European Countries.” European Journal of Ageing 17 (2):185–195.

- Hinchliff, S., and M. Gott. 2004. “Intimacy, Commitment, and Adaptation: Sexual Relationships within Long-Term Marriages.” Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 21 (5):595–609.

- Holdsworth, K., and M. McCabe. 2018. “The Impact of Dementia on Relationships, Intimacy, and Sexuality in Later Life Couples: An Integrative Qualitative Analysis of Existing Literature.” Clinical Gerontologist 41 (1):3–19. DOI10.1080/07317115.2017.1380102.

- Hook, M., L. Gerstein, L. Detterich, and B. Gridley. 2003. “How Close Are We? Measuring Intimacy and Examining Gender Differences.” Journal of Counseling & Development 81 (4):462–472.

- Ingbrant, R. 2020. “Michalina Wisłocka’s The Art Of Loving and the Legacy of Polish Sexology.” Sexuality & Culture 24 (2):371–388.

- Karraker, A., and J. DeLamater. 2013. “Past-Year Sexual Inactivity Among Older Married Persons and their Partners.” Journal of Marriage and Family 75 (1):142–163.

- Kościańska, A. 2016. “Sex on Equal Terms? Polish Sexology on Women’s Emancipation and ‘Good Sex’ from the 1970s to the Present.” Sexualities 19 (1-2):236–256.

- Lišková, K. 2018. Sexual Liberation, Socialist Style: Communist Czechoslovakia and the Science of Desire, 1945-1989. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- McCarthy, B., D. Cohn, and C. Koman. 2020. “Sexual Equity and the Good Enough Sex Model.” Sexual and Relationship Therapy 35 (3):291–303.

- Ménard, A. D., P. J. Kleinplatz, L. Rosen, S. Lawless, N. Paradis, M. Campbell, and J. D. Huber. 2015. “Individual and Relational Contributors to Optimal Sexual Experiences in Older Men and Women.” Sexual and Relationship Therapy 30 (1):78–93. doi:10.1080/14681994.2014.931689.

- Meston, C., and D. Buss. 2007. “Why Humans Have Sex.” Archives of Sexual Behavior 36 (4):477–507.

- Morrissey Stahl, K., J. Gale, D. Lewis, and D. Kleiber. 2019. “Pathways to Pleasure: Older Adult Women’s Reflections on Being Sexual Beings.” Journal of Women & Aging 31 (1):30–48. DOI10.1080/08952841.2017.1409305.

- Popovic, M. 2005. “Intimacy and Its Relevance in Human Functioning.” Sexual and Relationship Therapy 20 (1):31–49. DOI10.1080/14681990412331323992.

- Prager, K., and L. Roberts. 2004. “Deep Intimate Connection: Self and Intimacy in Couple Relationships.” In Handbook of Closeness and Intimacy, edited by Debra Mashek and Arthur Aron, 43–60. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Ridley, J. 1993. “Gender and Couples: Do Men and Women Seek Different Kinds of Intimacy?” Sexual and Marital Therapy 8 (3):243–253. DOI10.1080/02674659308404971.

- Sandberg, L. 2013. “Just Feeling a Naked Body Close to You: Men, Sexuality and Intimacy in Later Life.” Sexualities 16 (3–4):261–282.

- Ševčíková, A., and T. Sedláková. 2020. “The Role of Sexual Activity from the Perspective of Older Adults: A Qualitative Study.” Archives of Sexual Behavior 49 (3):969–981.

- Ševčíková, A., J. Gottfried, and L. Blinka. 2021. “Associations among Sexual Activity, Relationship Types, and Health in Mid and Later Life.” Archives of Sexual Behavior 50 (6):2667–2677.

- Sinclair, V., and S. Dowdy. 2005. “Development and Validation of the Emotional Intimacy Scale.” Journal of Nursing Measurement 13 (3):193–206.

- Smith, L., I. Grabovac, L. Yang, G. F. López-Sánchez, J. Firth, D. Pizzol, D. McDermott, N. Veronese, and S. E. Jackson. 2020. “Sexual Activity and Cognitive Decline in Older Age: A Prospective Cohort Study.” Aging Clinical and Experimental Research 32 (1):85–91. DOI10.1007/s40520-019-01334-z.

- Steklíková, E. 2014. “Sexualita seniorů.” [Sexuality of Elderly People]. Master's degree thesis, Charles University.

- Traeen, B., A. Štulhofer, E. Janssen, A. A. Carvalheira, G. M. Hald, T. Lange, and C. Graham. 2019. “Sexual Activity and Sexual Satisfaction Among Older Adults in Four European Countries.” Archives of Sexual Behavior 48 (3):815–829.

- Traeen, B., G. M. Hald, C. Graham, P. Enzlin, E. Janssen, I. L. Kvalem, A. Carvalheira, and A. Štulhofer. 2017. “Sexuality in Older Adults (65+)—An Overview of the Literature, Part 1: Sexual Function and Its Difficulties.” International Journal of Sexual Health 29 (1):1–10.