Abstract

Suicide is a major public health concern, patterned by systematic inequalities, with lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans (LGBT+) people being one example of a minoritised group that is more likely to think about and attempt suicide worldwide. To address this, UK national suicide prevention policies have suggested that LGBT+ people should be prioritised in prevention activities. However, there is little research seeking to understand how LGBT+ suicide is re/presented in political and policy spheres. In this article, we critically analyse all mentions of LGBT+ suicide in UK parliamentary debates between 2009 and 2019 and in the eight suicide prevention policies in use during this period. We argue that LGBT+ suicide is understood in two contrasting ways: firstly, as a pathological ‘problem’, positioning LGBT+ people either as risks or as at risk and in need of mental health support. Alternatively, suicide can be seen as externally attributable to perpetrators of homophobic, biphobic and transphobic hate, requiring anti-hate activities as part of suicide prevention. In response, we argue that although these explanations may appear oppositional; they both draw on reductive explanations of LGBT+ suicide, failing to consider the complexity of suicidal distress, thus constraining understandings of suicide and suicide prevention.

Keywords:

Background

Globally, suicide is considered a major public health problem with around 700,000 people dying by suicide annually (World Health Organization Citation2021). It is widely recognised that the distribution of suicide is patterned by systematic inequalities: one example of such inequalities is found amongst lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans (LGBT+Footnote1) people, who have consistently been found to be more likely to think about and attempt suicide worldwide (World Health Organization Citation2014). In the UK, understandings of LGBT+ suicide are hampered as sexual orientation, trans identity, nor gender identity are collected when recording death (McAllister and Noonan Citation2015). However, data has shown that LGBT+ people in the UK are more likely than cisgender (non-trans), heterosexual people to think about and attempt suicide (Rimes et al. Citation2019a, Citation2019b; Surace et al. Citation2021), and therefore it is likely that this will be mirrored in deaths by suicide (McAllister and Noonan Citation2015).

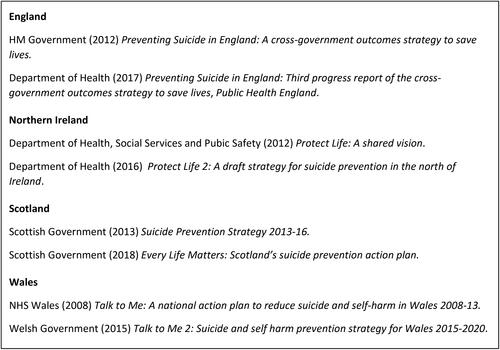

Responding to this, governments across the UK have identified LGBT+ people as requiring tailored suicide prevention (Department of Health Citation2016, Citation2017; Department of Health Social Services and Public Safety Citation2012; HM Government Citation2012a; NHS Wales Citation2008; Scottish Government Citation2013, Citation2018a; Welsh Government Citation2015). National suicide prevention strategies are recommended by the World Health Organization (Citation2021) as integral to reducing suicide. However, the politics and policies of suicide prevention have received little critical analysis (see Button Citation2016; East, Dorozenko, and Martin Citation2021; Fitzpatrick Citation2021; Marzetti et al. Citation2022; Reeves Citation2010 for notable exceptions), and this is similarly reflected in the study of LGBT+ suicide prevention.

One study by McAllister and Noonan (Citation2015) provides an in-depth analysis of how the suggestions for LGBT+ inclusion contained in Preventing Suicide in England, could be implemented both in healthcare settings and wider society, although it does not analyse the construction of the policy itself. In contrast, our research analyses re/presentations of LGBT+ people’s suicidal distress in UK policies and parliamentary debates 2009–2019 (the decade immediately following the 2008 recessionFootnote2), using the ‘What is the problem represented to be?' (WPR) approach to critical policy analysis (Bacchi and Goodwin Citation2016). To contextualise our analysis, we begin this article by tracing the historical roots of these policies in health, society, the law and politics.

LGBT+ suicide as a political issue

Historically, suicide has been predominantly understood as the tragic outcome of a pathologically disturbed mind, positioned as a fatal consequence of mental illness, most often depression (Hjelmeland and Knizek Citation2017). This has been widely integrated into mainstream discourses about suicide, with Marsh (Citation2010) arguing such understandings demonstrate a ‘compulsory ontology of pathology’ (18), in which suicide is conceptualised as necessarily medicalised. However, the framing of suicide as purely pathological has been problematised, with scholars questioning how viewing suicide through a psychocentric lens serves to obscure the socio-cultural, political, historical and economic contributors to suicidal distress (Rimke Citation2016), reducing possibilities for suicide prevention (Marzetti et al. Citation2022).

In contrast, understandings of LGBT+ suicide have tended to combine psychological and social factors in their approaches (Grzanka and Mann Citation2014), with explanations of LGBT+ suicide often focussing on homophobia, biphobia and transphobia (taken together, ‘queerphobia’ (Marzetti Citation2018)). This has primarily been understood using Minority Stress Theory, which proposes that expectations, experiences and internalisation of queerphobia, along with concealing one’s LGBT+ identity to avoid stigmatisation, enact minority stresses which can negatively impact both physical and mental health (Meyer Citation2003). As these stressors are understood to be rooted in social relations, interventions to reduce minority stress should seek to tackle queerphobia at its roots, in addition to any psychological support offered. However, research examining the relationship between queerphobia and suicide often fails to account for the ways in which queerphobia is embedded within the broad fabric of society through normative practices (Marzetti, McDaid, and O’Connor Citation2022; McDermott, Hughes, and Rawlings Citation2018). Minority stresses are often narrowly portrayed as the outcomes of individual, interpersonal interactions such as bullying, family non-acceptance, and hate crimes (Formby Citation2015; Robinson and Schmitz Citation2021; Wozolek, Wootton, and Demlow Citation2017), erroneously presumed to be perpetrated by a few individuals who are seen as disrupting an otherwise accepting status quo. Although they can be important contributors, focussing solely on interpersonal relationships obscures the ways in which minority stressors are also consequences of cis-heteronormative societies that regard being cisgender and being heterosexual as culturally desirable; othering those that do not comply and conform (Marzetti, McDaid, and O’Connor Citation2022; McDermott and Roen Citation2016).

Histories of exclusion: sin, crime, pathology

It is important to historicise cis-heteronormativity, queerphobia and mental health stigma in relation to LGBT+ people’s suicidal distress. In doing so, we are motivated by Sara Ahmed’s proposal that contemporary understandings of injustices must take into account and remember ‘the wounds that mark the place of historical injury’ (Ahmed Citation2014,173). Historically, both suicide and LGBT+ lives in the UK have been heavily influenced by views held in some Christian denominations; translating acts considered sinful in the Bible into crimes, before transforming them into pathological problems in need of treatment (Drescher Citation2010; Neeleman Citation1996). Suicide in England and Wales was illegal until the Suicide Act 1961 (9 & 10 Eliz 2, c. 60) and until 1966 in Northern Ireland (Criminal Justice Act (Northern Ireland) 1966), although it was never illegal in Scotland. After decriminalisation, suicide was reconceptualised as a mental health problem in need of clinical intervention (Hjelmeland and Knizek Citation2017). However, in many ways the social stigmatisation of suicide has persisted (Oexle et al. Citation2019).

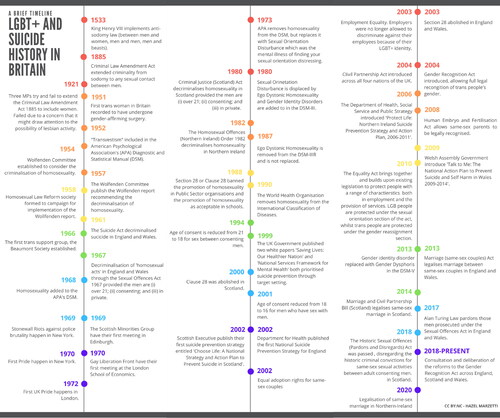

In a parallel history, same-sex relationships between men were illegal; with decriminalisation taking place in 1967 in England and Wales (Sexual Offences Act 1967 (s. 1)), in 1980 in Scotland (Criminal Justice (Scotland) Act 1980 (s. 80)), and in 1982 in Northern Ireland (The Homosexual Offences (Northern Ireland) Order 1982). Same-sex activities were never illegal between women in any of the four nations, nor was being trans. However legal gender recognition for trans people was not introduced until the Gender Recognition Act 2004, which at the time of writing is under review. Throughout the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, there has been a raft of legislation protecting and providing for LGBT+ people across the UK (see ). However, similarly to suicide, stigmatisation continued, with LGBT+ people often viewed as deviant or risky (Russell Citation2005). In 2011, the UK’s first transgender action plan Advancing Transgender Equality was introduced (HM Government Citation2011), followed by the UK’s first LGBT Action Plan (Government Equalities Office Citation2018a).

Figure 1. A brief timeline of LGBT+ and suicide history in Britain (edited from Marzetti Citation2020).

Concurrent with the decriminalisation of LGBT+ lives, however, pathologisation was codified within the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) and being LGBT+ could be conflated with being mentally ill (Ferlatte et al. Citation2019). This ended for cisgender lesbian, gay and bisexual people with the World Health Organization’s removal of homosexuality from the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) in 1990 and the removal of ‘ego dystonic homosexuality’ from the DSM in 1987. However, gender dysphoria remains within the DSM-5 used today, which maintains the pathologisation of trans people as having a ‘disorder’, a diagnosis often used to gate-keep gender-affirming medical treatment (for more detailed exploration of the pathologisation of LGBT+ people see Drescher Citation2010; Drescher Citation2015; Hubbard and Griffiths Citation2019; and Riggs et al. Citation2019).

Sticky assumptions underlying the ‘problem’ of LGBT+ suicide

Although formal representations of LGBT+ people as risky, criminal, and mentally ill have, for the most part, been denounced, social perceptions of deviancy persist (Wagaman Citation2016). McDermott and Roen (Citation2016) have argued that the repeated portrayal of LGBT+ people as mentally ill forged a dangerous association between being LGBT+ and being mentally ill; whilst critical suicide scholars have warned against simplistic explanations of suicide as the tragic final outcome of depression, without sufficiently attending to broader socio-economic or political contributors to suicide (Hjelmeland and Knizek Citation2017), such as poverty and austerity (Mills Citation2018).

Using Ahmed’s (Citation2014) concept of stickiness, we argue that the ways in which these dual associations have been repeatedly rehearsed throughout history helps explain how and why, in contemporary times, LGB+ people are frequently positioned as expected and accepted to be mentally ill, and how suicide can similarly become expected and accepted as an inevitable outcome of such illness. Taken together, these representations construct a pathological pathway from being LGBT+ to being suicidal (Waidzunas Citation2012). In this paper, we foreground both this entanglement and the simultaneous ongoing, complicated disentanglement of LGBT+ and suicidal people from perceptions of sinfulness, criminality and pathology to consider how contemporary policies and parliamentary debates reproduce, respond to, or resist these framings.

Methods

The data analysed in this article derive from a broader project seeking to understand the politics of suicide and suicide prevention in the UK through an analysis of suicide prevention policies and parliamentary records. Our analysis covers the years 2009–2019, and incorporates eight suicide prevention policies, two from each UK nation: England, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales (). We also conducted key word searches in Hansard and the equivalent search engines for Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales, identifying every mention of ‘suicide’ in parliamentary and assembly records across the four nations’ legislatures between 2009 and 2019. We found 3,247 references to suicide combined between the House of Commons and the House of Lords; 1,689 in Northern Ireland; 2,140 in Scotland; and 688 in Wales. The study was granted ethical approval by the University of Edinburgh’s Counselling, Psychotherapy and Applied Social Sciences (School of Health in Social Sciences) Research Ethics Committee.

Figure 2. Eight suicide prevention strategies, action plans and updates analysed in this paper (adapted from Marzetti et al. Citation2022, 5–6).

To begin our analysis, policy documents were analysed using a combination of deductive and inductive coding, underpinned by the central guiding questions of the WPR approach to critical policy analysis (Bacchi and Goodwin Citation2016). This approach seeks to challenge the notion that the ‘problems’ that parliamentary activities and policies aim to ‘solve’ are independent of political practices, instead arguing that these ‘problems’ must always be understood as the products of governments’ practices and ways of thinking. To better understand the governmentalities that construct these problems, Bacchi and Goodwin developed a series of analytical questions to guide WPR analysis concerning policy decisions. Guided by these, the work presented in this paper focuses on how the policies and parliamentary debates represent the ‘problem’ of LGBT+ suicide (Q1); the assumptions that underlie this representation (Q2) and the ways in which this has come about (Q3); the silences that remain within these particular representations of LGBT+ suicide prevention (Q4); and the effects of these problematisations (Q5).

During our analysis of the eight policies, we noticed that LGBT+ people were frequently positioned as a group with higher rates of suicide requiring tailored suicide prevention, and we therefore explored this further in our analysis of parliamentary records. HLM and AO thematically organised the parliamentary records according to the topics discussed within them, finding 79 parliamentary debates that mentioned LGBT+ suicide, and this data was then combined with the LGBT+ references from the suicide prevention policies. Bringing these two groups of documents together, HLM undertook a thematic analysis, guided by the principles of the WPR approach. These themes were developed and refined in conversation with AC, AJ and AO, considering the synergies and dissonances between the two data sets.

Findings

Othering by numbers: a cycle of statistical invisibility

The majority of prevention policy documents identified LGBT+ people, amongst a raft of other marginalised groups, as at increased risk of suicide. Mentions of LGBT+ people tended to be brief, sometimes acknowledging the need for tailored or prioritised support and awareness, with little further discussion. In part, this seemed to be consistent with the commitment to quantification that was evident throughout the policies analysed, and that has been more broadly acknowledged and critiqued in the field of suicide prevention (Hjelmeland Citation2016).

Some groups of people are known to be at higher risk of suicide than the general population. […] but limits on the data available mean that their risk is hard to estimate, or else there is no way of monitoring progress as a result of suicide prevention measures. (HM Government Citation2012a, 13)

This quote from Preventing Suicide in England acts as one example of what can happen when the statistical monitoring of the effectiveness of prevention is prioritised over prevention itself, and reveals an implicit prioritisation of the prevention of suicides that can be statistically measured, monitored and evaluated.

In this particular policy, LGBT+ people were one of many groups that were not included under ‘Action 1: Reduce the risk of Suicide in key high risk groups’, and were instead mentioned under ‘Action 2: Tailor approaches to improve mental health in specific groups’, which discussed broadly improving the population’s mental health as a method of reducing suicide risk. ‘Action 2′ also tended to signpost outside of the policies either to other policies or to the work of charitable sector organisations, whilst acknowledging that ‘for many of these groups we do not have sufficient information about numbers of suicides or about what interventions might be helpful’ (21), presenting a statistical dead-end. This statistical invisibility was then used to provide justification for the lack of tailored suicide prevention, creating an almost self-fulfilling cycle:

Due to the limited equality data for deaths recorded by General Register Office, it is quite possible that there may be differential impact on other equality groups that have not been analysed such as sexual orientation, disability status, ethnicity and those with/without dependants. (Department of Health Social Services and Public Safety Citation2012, 55)

The risk from nowhere: risky gays or a risky gaze

The re/production of LGBT+ people as at risk was used to emphasise the importance of LGBT+ suicide and its prevention, and to advocate for greater support:

Staff in health and care services, education and the voluntary sector need to be aware of the higher rates of mental distress, substance misuse, suicidal behaviour or ideation and increased risks of self-harm amongst lesbian, gay and bisexual people, as well as transgender people. (HM Government Citation2012a, 7)

Although the positioning of sexual orientation as risk was unique to Protect Life, the conceptualisation of LGBT+ people as at risk of anxiety, depression, self-harm and suicide was widespread. This conceptualisation appeared to be consistently attached to groups that prevention policies deemed high risk (for example, Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic people, unemployed people, and men), but where this risk came from, and how it came to be, was often left under explored. For example,

Research suggests that adults and young people who identify as gay, lesbian, bisexual or transgender have a greater risk of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts. (Scottish Government Citation2018a, 14)

This narrative process of sweeping the production of risk away from structural contributors to suicidal distress and tidying them into individual bodies ‘at risk’ illuminates a tension. Whilst it may be clear that a group, such as LGBT+ people, experiences high incidence of suicidal thoughts and attempts, demonstrating an undeniable health inequality (World Health Organization Citation2014), narratives of risk should carefully balance recognising such health inequalities with reproducing them. We argue, therefore, that where policies focus on individuals at risk rather than structural factors producing health inequalities, suicide appears framed as an individual, apolitical, ahistorical problem, which as discussed in this article’s opening is misleading. In doing so, the representation of the at risk LGBT+ suicidal person has the potential to become a caricature that may compound or extend existing stigmatisation of LGBT+ people and inhibit suicide prevention practices that seek to disrupt this ‘risk’ at its roots.

Hate kills

In contrast to psychologising explanations to LGBT+ suicide, the third progress report on Preventing Suicide in England (2017) briefly discusse homophobic, biphobic and transphobic bullying as an external contributor to suicidal distress. This externalising social approach was also widely evident in parliamentary debates, with LGBT+ suicide routinely portrayed as the result of queerphobic stigma, discrimination and harassment. This was particularly the case in discussions of LGBT+ youth suicide, where queerphobic bullying was positioned as a significant contributor, but was also reflected upon more widely, with parliaments considering the ways in which structural inequalities (such as marriage, historic pardons and disregards, and the introduction of LGBTI inclusive education in Scotland; to be discussed later) contributed to a climate in which LGBT+ people could find life unliveable. We will consider each in turn.

What about the children?

In both parliamentary debates and, to a lesser extent prevention policies, suicidal distress amongst LGBT+ young people was in part attributed to queerphobic bullying in schools. For example, Rona Mackay MSP stated that:

Many LGBTI children in Scotland are terrified of going to school, where they are terrorised for simply being themselves. Children are harming themselves as a direct result of the abuse that they receive in school. When they should be planning their future, some are planning their deaths. (Scottish Parliament Official Record, 19th April 2017, col 97)

Underlying such discussions was a powerful secondary narrative centred on young people’s ability to have a prosperous future in which their potential could be fulfilled. Although undoubtedly all young people should have an equal right to a prosperous future, we wish to unsettle approaches that look to tomorrow to justify why young people should be treated with care and respect today. Arguments about un/fulfilled potential evoke ideas of particular types of futures for preservation, privileging lives that conform to normative standards: namely those that are white, middle-class, not disabled, and often male, which may then intersect with normative ideals related to sexuality and gender identity (Cover Citation2012; Grzanka and Mann Citation2014; McDermott and Roen Citation2016; Puar Citation2012). The privileging of lives that can fulfil neo-liberal expectations of the ‘good life’: doing ‘well’ in education, getting a ‘good’ job, marrying, having children, and using purchasing power in the capitalist economy, serves to reinforce the problematic idea that there are some lives more deserving of longevity than others (Butler Citation2004).

Re-framing the ‘problem’ of suicide as attributable to bullying, simultaneously re-frames suicide prevention as anti-hate work. For example, Lord Collins of Highbury emphasised that:

Schools must be in no doubt that they have a fundamental responsibility to prevent such bullying happening in the first place. Schools need to be environments where young people feel comfortable in reporting homophobic bullying. (Hansard, House of Lords Debate, 4th July Citation2011, Col 44)

A rare contrasting example, acknowledging the relationship between queerphobia in wider society and queerphobic bullying, is a speech by John O’Dowd in the Northern Ireland Assembly:

The attitudes in our schools are often a reflection of the attitudes in our broader society. There is a responsibility on communities and families to ensure that homophobic bullying is totally unacceptable. There is a responsibility to ensure that we do not use language or involve ourselves in actions that will encourage such homophobic bullying or, for that matter, any form of bullying. (Northern Ireland Assembly Official Report, 11th June 2012, 283)

Suicide as a tool of rhetoric

Throughout the years analysed there were significant changes in LGBT+ rights in three nations of the UK (see ) regarding marriage equality, and conversations about future changes were had in the fourth (NI). During these same years, LGBTI inclusive education was introduced in the Scottish Parliament, and the Historic Sexual Offences (Pardons and Disregards) Act 2018 was passed in Scotland. In England and Wales The Protection of Freedoms Act 2012 (Section 92) enabled persons convicted under various repealed laws criminalising homosexual acts to apply to the Home Secretary for their convictions and cautions to be disregarded. Legislative changes were seen by its proponents as righting past wrongs, explicitly promoting equalities. This progress was positioned by some as a source of national pride, for example, in this speech by Monica Lennon she argued:

passionately for the rights of families to have their late relatives’ convictions pardoned. That includes, devastatingly, the families of men who say that their loved ones died by suicide as a consequence of the stigma of homosexuality. […] Scotland has reached a high point for LGBT rights, being recognised in 2015 and 2016 as the best country in Europe for LGBTI legal equality. (Scottish Parliament Official Report, 6th June 2018, col 39)

What we say in the House today will go out on radio and television this evening. People sitting around their dinner table will watch this and see what the views of senior politicians are. People, particularly the young, will be informed by the opinions of politicians. As Bronwyn McGahan said, there is a lot of prejudice and discrimination on this issue in our community. We need to send out a clear message that people from the LGBT community are equal and are entitled to the same rights as everybody else. Prejudicial views lead to discrimination, and that discrimination has an ongoing devastating impact on young men and women who are gay. It leads to bullying, harassment and suicide. (Northern Ireland Assembly Official Report, 1st October 2012, 19)

Discussion

Throughout our data we identified a somewhat dichotomised representation of the ‘problem’ of LGBT+ suicide: as either internally attributable to LGBT+ individuals, or as externally attributable to the perpetrators of queerphobic hate. Although both approaches were used to argue that suicide prevention should be tailored to the needs of LGBT+ communities, we argue that both, somewhat perversely, could have potentially problematic consequences for understandings of LGBT+ suicide and suicide prevention. Approaches that internalise risk within LGBT+ bodies made use of two established societal narratives discussed in this article’s opening: positioning LGBT+ people as ‘risky’ (Russell Citation2005) and suicide as a pathological problem (Marsh Citation2010). Although we believe that these framings are often unintentional, they can create ‘sticky’ associations (Ahmed Citation2014) between being LGBT+ and being suicidal, which may result in looping effects (Hacking Citation2006) whereby LGBT+ people internalise narratives positioning LGBT+ people as suicidal, in turn increasing their risk of suicide (Waidzunas Citation2012).

Psychologising suicide risk may also have additional consequences for the types of suicide prevention that are considered useful. More broadly, it has been argued that UK suicide prevention policies frame suicidal distress as a mental health problem, and thus rely on increased and improved surveillance practices, improved mental health care, and restricted access to lethal means (for example, by removing potential ligature points within hospitals and prisons, particularly within statutory settings) (Marzetti et al. Citation2022; Reeves Citation2010). Within the prevention policies analysed in this article, the need for suicide prevention tailored for LGBT+ people was acknowledged as necessary and desirable. However, policies were more vague about how this could be implemented, and whether they would be expected to fit within the rather medicalised parameters of suicide prevention suggested more broadly in the policies. Instead, prevention policies tended to signpost outwards, indicating that individual health boards, institutions and practitioners would need to interpret the ways in which this prioritisation and tailoring could and should be implemented. However, we wondered whether such services would feel sufficiently informed, equipped and resourced to provide tailored prevention, and whether there would be any further governmental support for doing so. This also raises the possibility that if statutory services are not equipped to provide ‘tailored’ approaches to suicide mitigation, then related suicide prevention and care needs maybe pushed back onto already stretched LGBT+ communities to provide under-resourced and unfunded support on a peer-to-peer basis (Worrell et al. Citation2022).

In contrast, approaches that entirely externalised suicide risk, understanding LGBT+ suicide as solely a social problem, located with the perpetrators of queerphobia, conceptualised suicide prevention as within the purview of anti-hate activities. Although such approaches were less pathologising, they could overlook the agency and emotions of individuals feeling suicidal (McDermott, Roen, and Scourfield Citation2008), resulting in different, yet still over-simplistic and deterministic understandings of LGBT+ suicide (Grzanka and Mann Citation2014). It has been argued that such approaches can present suicide as an almost causal, inevitable consequence of queerphobia (Waidzunas Citation2012), obfuscating other possible contributors of LGBT+ suicidal distress (Bryan and Mayock Citation2017; McDermott and Roen Citation2016). In addition, such approaches can serve to individualise queerphobia within interpersonal relationships, ignoring the ways in which such interactions may be shaped by broader socio-political dynamics (Cover Citation2012; Formby Citation2015; Wozolek, Wootton, and Demlow Citation2017) and limiting the narratives available to LGBT+ people for making sense of suicidal feelings (Salway and Gesink Citation2018).

This framing of queerphobia was evident in discussions of bullying in our data. Consonant with broader literature, such discussions often appeared to suggest that queerphobic bullying was confined to the school environment, present within negative interactions between individual pupils, that disrupted an otherwise accepting and affirming school system (Formby Citation2015; Macintosh Citation2007; Wozolek, Wootton, and Demlow Citation2017). This representation of queerphobia obscures reality, where research has demonstrated that the UK is not a consistently safe nor affirming place in which to be LGBT+ (Bachmann and Gooch Citation2017; Government Equalities Office Citation2018b). We argue that representing queerphobia as an individual issue fails to account for the social, structural and institutional nature of queerphobia in a number of areas of public life (McDermott, Hughes, and Rawlings Citation2018), and fails to hold governments to account for their own roles in upholding and perpetuating systemic cis-heteronormativity. Indeed, in our analysis of parliamentary records, the only discussion of governmental contributors to LGBT+ suicide tended to be highly superficial, primarily positioned as rhetorical warning devices about potential future harms.

To better understand, and indeed prevent, LGBT+ suicide therefore, we argue that internalising, psychological approaches and externalising, social approaches to understanding LGBT+ suicide must be brought into dialogue with one another. To do so, we suggest considering the potential of social ecological approaches, which can take into account the multiple, complex interactions between individuals, their interpersonal relationships and communities, and the broader socio-economic and political landscape (Scourfield, Roen, and McDermott Citation2008; Standley Citation2020). In doing so we can begin to ask different questions, resisting binary understandings that position LGBT+ people as at risk of suicide (Alasuutari et al. Citation2021; Bryan and Mayock Citation2017; Cover Citation2012). This critical re-framing may help us to ask more nuanced questions, such as why it is that some LGBT+ people experience queerphobia and go on to feel suicidal, whilst others do not (McDermott and Roen Citation2016). This would also enable researchers, policy makers and politicians to take the, undoubtedly important, role of queerphobia into account when considering LGBT+ suicide, whilst also creating space for understanding the many nuances and complexities of human experiences additional to LGBT+ identity that may also impact upon LGBT+ suicide. This needs to incorporate intersecting structural factors such as social class (McDermott and Roen Citation2016); urban-rural particularities (Keene et al. Citation2017); and ethnicity (Mereish et al. Citation2019); as well as individual and interpersonal adversities such as adverse childhood experiences or relationships problems (Rimes et al. Citation2019b; Rivers et al. Citation2018; Williams et al. Citation2021).

Conclusion

In conclusion, discussions of LGBT+ suicide in UK prevention policies and political debates (2009–2019) were dichotomised. LGBT+ suicide was either conceptualised as a psychological problem contained within risky, pathological LGBT+ bodies, or as a consequence of queerphobic hate, with little space left for greater nuance. Whilst psychologised risk narratives failed to acknowledge the systemic effects of cis-heteronormativity and queerphobia; externalising risk narratives constructed a simple cause-and-effect relationship between queerphobia and suicide, reducing possibilities for intersectional analysis, and overlooking contributors beyond the stigmatisation of sexual orientation and gender identity. Thus, although parliamentary debates appeared to direct our attention towards social interventions to reduce queerphobia as methods of suicide prevention, this was not widely reflected in prevention policies, which we argue is a key omission in UK suicide prevention strategies that needs to be addressed. To conclude, we argue that policy makers and politicians must work together to provide support for individuals experiencing suicidal distress through the provision of community and clinical resourcing. However, they must also maintain a long-term vision that can work to tackle the structural and systemic conditions, related to sexual orientation and gender identity and beyond, that contribute to LGBT+ people’s lives becoming unliveable.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability

All data used in the project is publicly available using public databases and search engines.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Most broadly, the term LGBT+ is used to incorporate the diverse communities brought together under the rainbow umbrella, who may or may not define their sexual, romantic or gender identities under the defined LGBT categories but who nonetheless do not identify as simultaneously cisgender, heteroromantic and heterosexual. In this article specifically, the acronym also represents the diversity of acronyms used across the policies and parliamentary debates. These include, but are not limited to LGBT LGBT+ LGBTI (including intersex people specifically) LGBTQ (including queer people specifically) and LGBTQI.

2 For a more detailed exploration of the relationship between austerity and suicide, see Mills (Citation2018).

References

- Ahmed, S. 2014. The Cultural Politics of Emotion. 2nd ed. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press Ltd.

- Alasuutari, V., S. B. Whitestone, L. Goret Hansen, K. Jaworski, and O. Doletskaya. 2021. “Queer 2/.” Whatever 4:599–630. doi:10.13131/2611-657X.whatever.v4i1.148

- Bacchi, C., and S. Goodwin. 2016. Poststructural Policy Analyses - Guide to Practice. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bachmann, C. L., and B. Gooch. 2017. “LGBT in Britain Hate Crime and Discrimination.” Stonewall. https://www.stonewall.org.uk/lgbt-britain-hate-crime-and-discrimination

- Bryan, A., and P. Mayock. 2017. “Supporting LGBT Lives? Complicating the Suicide Consensus in LGBT Mental Health Research.” Sexualities 20 (1–2):65–85.

- Butler, J. 2004. Undoing Gender. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Button, M. E. 2016. “Suicide and Social Justice: Toward a Political Approach to Suicide.” Political Research Quarterly 69 (2):270–280. doi:10.1177/1065912916636689.

- Cover, R. 2012. Queer Youth Suicide, Culture and Identity: Unliveable Lives? Queer Youth Suicide, Culture and Identity: Unliveable Lives? Farnham: Ashgate Publishing.

- Department of Health 2016. “Protect Life 2: A Draft Strategy for Suicide Prevention in the North of Ireland.” https://www.health-ni.gov.uk/protectlife2

- Department of Health Social Services and Public Safety. 2012. “Protect Life a Shared Vision.” https://setrust.hscni.net/download/297/mental-health-and-emotional-wellbeing/3773/refreshed_protect_life.pdf

- Department of Health. 2017. “Preventing Suicide in England: Third Progress Report of the Cross-Government Outcomes Strategy to Save Lives.” https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/suicide-prevention-third-annual-report.

- Drescher, J. 2010. “Queer Diagnoses: Parallels and Contrasts in the History of Homosexuality, Gender Variance, and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual.” Archives of Sexual Behavior 39 (2):427–460.

- Drescher, J. 2015. “Out of DSM: Depathologizing Homosexuality.” Behavioral Sciences 5 (4):565–575.

- East, L., K. P. Dorozenko, and R. Martin. 2021. “The Construction of People in Suicide Prevention Documents.” Death Studies 45 (3):182–190.

- Ferlatte, O., J. L. Oliffe, D. R. Louie, D. Ridge, A. Broom, and T. Salway. 2019. “Suicide Prevention from the Perspectives of Gay, Bisexual, and Two-Spirit Men.” Qualitative Health Research 29 (8):1186–1198.

- Fitzpatrick, S. J. 2021. “The Moral and Political Economy of Suicide Prevention.” Journal of Sociology 58 (1):113–129.

- Formby, E. 2015. “Limitations of Focussing on Homophobic, Biphobic and Transphobic “Bullying” to Understand and Address LGBT Young People’s Experiences within and beyond School.” Sex Education 15 (6):626–640.

- Government Equalities Office. 2018a. LGBT Action Plan Improving the Lives of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender People. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/lgbt-action-plan-2018-improving-the-lives-of-lesbian-gay-bisexual-and-transgender-people.

- Government Equalities Office. 2018b. National LGBT Survey Summary Report. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-lgbt-survey-summary-report

- Grzanka, P. R., and E. S. Mann. 2014. “Queer Youth Suicide and the Psychopolitics of “It Gets Better.” Sexualities 17 (4):369–393.

- Hacking, I. 2006. “Making Up People.” London Review of Books, August 17, 2006. https://www.lrb.co.uk/thepaper/v28/n16/ian-hacking/making-up-people

- Hansard. 2011. “House of Lords Debate of 4th July 2011.” https://hansard.parliament.uk/Lords/2011-07-04/debates/11070420000137/EducationBill?highlight=education%20bill%20house%20lords#contribution-1107051000016

- Hjelmeland, H. 2016. “A Critical Look at Current Suicide Research.” In Critical Suicidology. Transforming Suicide Research and Prevention for the 21st Century, edited by Jennifer White, Ian Marsh, Michael J. Kral, and Jonathan Morris, 31–55. Vancouver: UBC Press.

- Hjelmeland, H., and B. L. Knizek. 2017. “Suicide and Mental Disorders: A Discourse of Politics, Power, and Vested Interests.” Death Studies 41 (8):481–492.

- HM Government. 1961. The Suicide Act 1961 9 and 10 Eliz 2, c. 60

- HM Government. 1967. Sexual Offences Act 1967 s.1

- HM Government. 2004. Gender Recognition Act (UK) 2004 c.7.

- HM Government. 2011. “Advancing Transgender Equality: A Plan for Action.” no. December:20.

- HM Government. 2012a. Preventing Suicide in England.

- HM Government. 2012b. Protection of Freedoms Act 2012 (England and Wales)

- Hubbard, K. A., and D. A. Griffiths. 2019. “Sexual Offence, Diagnosis, and Activism: A British History of LGBTIQ Psychology.” The American Psychologist 74 (8):940–953.

- Keene, D. E., A. I. Eldahan, J. M. White Hughto, and J. E. Pachankis. 2017. ““The Big Ole Gay Express”: Sexual Minority Stigma, Mobility and Health in the Small City.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 19 (3):381–394.

- Macintosh, L. 2007. “Does Anyone Have a Band-Aid? Anti-Homophobia Discourses and Pedagogical Impossibilities.” Educational Studies 41 (1):33–43.

- Marsh, I. 2010. Suicide: Foucault, History and Truth. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Marshal, M. P., L. J. Dietz, M. S. Friedman, R. Stall, H. A. Smith, J. McGinley, B. C. Thoma, P. J. Murray, A. R. D'Augelli, and D. A. Brent. 2011. “Suicidality and Depression Disparities between Sexual Minority and Heterosexual Youth: A Meta-Analytic Review.” Journal of Adolescent Health 49 (2):. 15–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.02.005.

- Marzetti, H. 2018. “Proudly Proactive: Celebrating and Supporting LGBT+ Students in Scotland.” Teaching in Higher Education 23 (6):701–717.

- Marzetti, H. 2020. “Exploring and Understanding Young LGBT+ People’s Suicidal Thoughts and Attempts in Scotland.” PhD Diss., University of Glasgow.

- Marzetti, H., A. Oaten, A. Chandler, and A. Jordan. 2022. “Self-Inflicted. Deliberate. Death-Intentioned. A Critical Policy Analysis of UK Suicide Prevention Policies 2009–2019.” Journal of Public Mental Health 21 (1):4–14.

- Marzetti, H., L. McDaid, and R. O’Connor. 2022. ““Am I Really Alive?”: Understanding the Role of Homophobia, Biphobia and Transphobia in Young LGBT+ People’s Suicidal Distress.” Social Science & Medicine 298:114860. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.114860

- McAllister, S., and I. Noonan. 2015. “Suicide Prevention for the LGBT Community: A Policy Implementation Review.” British Journal of Mental Health Nursing 4 (1):31–37.

- McDermott, E., and K. Roen. 2016. QuSeer Youth, Suicide and Self-Harm Troubled Subjects, Troubling Norms. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- McDermott, E., E. Hughes, and V. Rawlings. 2018. “Norms and Normalisation: Understanding Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Queer Youth, Suicidality and Help-Seeking.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 20 (2):156–172.

- McDermott, E., K. Roen, and J. Scourfield. 2008. “Avoiding Shame: Young LGBT People, Homophobia and Self-Destructive Behaviours.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 10 (8):815–829.

- Mereish, E. H., M. Sheskier, D. J. Hawthorne, and J. T. Goldbach. 2019. “Sexual Orientation Disparities in Mental Health and Substance Use among Black American Young People in the USA: Effects of Cyber and Bias-Based Victimisation.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 21 (9):985–998.

- Meyer, I. 2003. “Prejudice, Social Stress, and Mental Health in Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Populations: Conceptual Issues and Research Evidence.” Psychological Bulletin 129 (5):674–697.

- Mills, C. 2018. ““Dead People Don’t Claim”: A Psychopolitical Autopsy of UK Austerity Suicides.” Critical Social Policy 38 (2):302–322.

- Neeleman, J. 1996. “Suicide as a Crime in the UK: Legal History, International Comparisons and Present Implications.” Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 94 (4):252–257.

- NHS Wales. 2008. Talk to Me – A National Action Plan to Reduce Suicide and Self Harm in Wales 2008-2013. Cardiff: NHS Wales

- Northern Ireland Assembly. 2012. “Official Report of 11th June 2012.” http://www.niassembly.gov.uk/globalassets/documents/official-reports/plenary/2012/20120611.pdf

- Northern Ireland Assembly. 2012. “Official Report, 1st October 2012.” http://www.niassembly.gov.uk/assembly-business/official-report/reports-12-13/01-october-2012/

- Northern Ireland Government. 1966. Criminal Justice Act 1966 (Northern Ireland). S.12.

- Northern Ireland Government. 1982. The Homosexual Offences (Northern Ireland) Order. 1982 No. 1536, NI. 19.

- Oexle, N., K. Herrmann, T. Staiger, L. Sheehan, N. Rüsch, and S. Krumm. 2019. “Stigma and Suicidality among Suicide Attempt Survivors: A Qualitative Study.” Death Studies 43 (6):381–388.

- Puar, J. K. 2012. “Coda: The Cost of Getting Better: Suicide, Sensation, Switchpoints.” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 18 (1):149–158.

- Reeves, A. 2010. Counselling Suicidal Clients. London: SAGE.

- Riggs, D. W., R. Pearce, C. A. Pfeffer, S. Hines, F. White, and E. Ruspini. 2019. “Transnormativity in the Psy Disciplines: Constructing Pathology in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders and Standards of Care.” The American Psychologist 74 (8):912–924.

- Rimes, K. A., N. Goodship, G. Ussher, D. Baker, and E. West. 2019a. “Non-Binary and Binary Transgender Youth: Comparison of Mental Health, Self-Harm, Suicidality, Substance Use and Victimization Experiences.” The international Journal of Transgenderism 20 (2–3):230–240.

- Rimes, K. A., S. Shivakumar, G. Ussher, D. Baker, Q. Rahman, and E. West. 2019b. “Psychosocial Factors Associated With Suicide Attempts, Ideation, and Future Risk in Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Youth.” Crisis 40 (2):83–92.

- Rimke, H. 2016. “Introduction - Mental and Emotional Distress as a Social Justice Issue: Beyond Psychocentrism.” Studies in Social Justice 10 (1):4–17.

- Rivers, I., C. Gonzalez, N. Nodin, E. Peel, and A. Tyler. 2018. “LGBT People and Suicidality in Youth: A Qualitative Study of Perceptions of Risk and Protective Circumstances.” Social Science & Medicine 212 (September):1–8.

- Robinson, B. A., and R. M. Schmitz. 2021. “Beyond Resilience: Resistance in the Lives of LGBTQ Youth.” Sociology Compass 15 (12):1–15.

- Russell, S. T. 2005. “Beyond Risk: Resilience in the Lives of Sexual Minority Youth.” Journal of Gay & Lesbian Issues in Education 2 (3):5–18.

- Salway, T., and D. Gesink. 2018. “Constructing and Expanding Suicide Narratives from Gay Men.” Qualitative Health Research 28 (11):1788–1801.

- Scottish Government. 1980. Criminal Justice (Scotland) Act.1980, S.80.

- Scottish Government. 2013. “Suicide Prevention Strategy 2013–2016.” https://www.gov.scot/publications/scottish-government-suicide-prevention-strategy-2013-2016/

- Scottish Government. 2018a. “Every Life Matters: Scotland’s Suicide Prevention Action Plan.” https://www.gov.scot/publications/scotlands-suicide-prevention-action-plan-life-matters/

- Scottish Government. 2018b. Historical Sexual Offences (Pardons and Disregards) (Scotland) Act 2018.

- Scottish Parliament. 2017. “Official Report of 19th April 2017.” https://www.parliament.scot/chamber-and-committees/official-report/search-what-was-said-in-parliament/meeting-of-parliament-19-04-2017?meeting=10890

- Scottish Parliament. 2018. “Official Report of 6th June 2018.” https://www.parliament.scot/chamber-and-committees/official-report/search-what-was-said-in-parliament/meeting-of-parliament-06-06-2018?meeting=11581

- Scourfield, J., K. Roen, and L. McDermott. 2008. “Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Young People’s Experiences of Distress: Resilience, Ambivalence and Self-Destructive Behaviour.” Health & Social Care in the Community 16 (3):329–336.

- Standley, C. J. 2020. “Expanding Our Paradigms: Intersectional and Socioecological Approaches to Suicide Prevention.” Death Studies 46 (1):224–232.

- Surace, T., L. Fusar-Poli, L. Vozza, V. Cavone, C. Arcidiacono, R. Mammano, L. Basile, A. Rodolico, P. Bisicchia, P. Caponnetto, et al. 2021. “Lifetime Prevalence of Suicidal Ideation and Suicidal Behaviors in Gender Non-Conforming Youths: A Meta-Analysis.” European child & Adolescent Psychiatry 30 (8):1147–1161.

- Wagaman, M. A. 2016. “Self-Definition as Resistance: Understanding Identities among LGBTQ Emerging Adults.” Journal of LGBT Youth 13 (3):207–230.

- Waidzunas, T. 2012. “Young, Gay, and Suicidal: Dynamic Nominalism and the Process of Defining a Social Problem with Statistics.” Science Technology and Human Values 37 (2):199–225.

- Welsh Government. 2015. “Talk to Me 2: Suicide and Self Harm Prevention Strategy for Wales 2015–2020.” https://gov.wales/sites/default/files/publications/2019-06/talk-to-me-2-suicide-and-self-harm-prevention-action-plan-for-wales-2015-2020.pdf

- WHO (World Health Organisation). 2014. Preventing Suicide A Global Imperative A Global Imperative. Geneva. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241564779

- WHO (World Health Organization). 2021. “LIVE LIFE. An Implementation Guide for Suicide Prevention in Countries.” https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240026629

- Williams, A. J., C. Jones, J. Arcelus, E. Townsend, A. Lazaridou, and M. Michail. 2021. “A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Victimisation and Mental Health Prevalence among LGBTQ + Young People with Experiences of Self-Harm and Suicide.” Plos One 16 (1):e0245268.

- Worrell, S., A. Waling, J. Anderson, A. Lyons, J. Fairchild, and A. Bourne. 2022. “Coping with the Stress of Providing Mental Health-Related Informal Support to Peers in an LGBTQ Context.” Culture, Health & Sexuality:1–16. doi:10.1080/13691058.2022.2115140

- Wozolek, B., L. Wootton, and A. Demlow. 2017. “The School-to-Coffin Pipeline: Queer Youth, Suicide, and Living the In-Between.” Cultural Studies ↔ Critical Methodologies 17 (5):392–398.