Abstract

Managing fertility and sexual and reproductive health across the life course is associated with numerous responsibilities disproportionately experienced by women. This extends beyond dealing with the physical side effects of contraception and can include the emotional burden of planning conception and the financial cost of accessing health services. This scoping review aimed to map how reproductive responsibilities were defined and negotiated (if at all) between heterosexual casual and long-term partners during any reproductive life event. Original research in high-income countries published from 2015 onwards was sourced from Medline (Ovid), CINAHL and Scopus. In studies that focused on pregnancy prevention and abortion decision making, men felt conflict in their desire to be actively engaged while not wanting to impede their partner’s agency and bodily autonomy. Studies identified multiple barriers to engaging in reproductive work including the lack of acceptable male-controlled contraception, poor sexual health knowledge, financial constraints, and the feminisation of family planning services. Traditional gender roles further shaped men’s involvement in both pregnancy prevention and conception work. Despite this, studies reveal nuanced ways of sharing responsibilities – such as companionship during birth and abortion, ensuring contraception is used correctly during intercourse, and sharing the costs of reproductive health care.

Introduction

Managing fertility and maintaining sexual health across the life course is associated with a variety of tasks, responsibilities, and burdens. These extend beyond dealing with the physical side-effects of contraception or pregnancy and can include the financial costs of contraception, the emotional burdens of planning conception, and the stigma of accessing abortion services (Altshuler et al. Citation2021; Hamper Citation2021). Although many such burdens can be shared between heterosexual partners, they are disproportionately experienced by those with female reproductive organs. This is significant; women of reproductive age between 15–44 constitute approximately 20% of the national population in Australia (Australian Bureau of Statistics Citation2021) and 95% of Australian women at risk of pregnancy use some form of contraception (Richters et al. Citation2016). It is estimated that one third of Australian women experience an unintended pregnancy within their lifetime (Rowe et al. Citation2016), and that 40% of pregnancies in Australia are unintended (Organon Citation2022), a figure comparable to global estimates suggesting that 44% of pregnancies are unintended (Bearak et al. Citation2018). Furthermore in Australia, 17.3 abortions take place per 1000 women aged 15–44 each year (Keogh, Gurrin, and Moore Citation2021).

Reproductive responsibilities and burdens are increasingly recognised under an array of terms, including ‘fertility work’ (Bertotti Citation2013), ‘contraceptive labour’ (Kimport Citation2018a), and ‘procreative responsibility’(Campbell, Turok, and White Citation2019). The use of these terms, and their meanings varies within the literature, presenting challenges to understanding and investigating this phenomenon. We use the terms ‘reproductive responsibility, work and/or burdens’ to describe any task requiring active engagement or management (physical, emotional, mental, financial or time) from an individual during any reproductive event, such as maintaining sexual health, initiating conversations with partners about sexual and/or reproductive issues, or managing the side effects of a contraceptive method.

There has been investigation into the role that men play, and the role that women want men to play, in sharing reproductive responsibilities. While some studies have examined pregnancy prevention and decision-making in the context of long-term relationships (Bertotti Citation2013; Fennell Citation2011), others have focused on the mental, physical, emotional and economic impact of taking reproductive responsibility (Wigginton et al. Citation2015; Kimport Citation2018a), or the way in which reproductive public health messaging and services are targeted at those with female reproductive organs (Wilson Citation2020). Kimport showed how health providers and family planning services reinforce the idea that pregnancy prevention is women’s work during contraceptive counselling appointments (Kimport Citation2018b). Men have also been shown to rely on their partners to effectively manage contraception and pregnancy prevention (Ekstrand et al. Citation2007; Merkh et al. Citation2009).

Despite substantial evidence that posits reproductive responsibilities as women’s work, studies have provided examples of men taking primary responsibility for achieving individual and shared reproductive goals in the form of shared decision making, sharing financial costs, and companionship during abortion and birth (Wigginton et al. Citation2018; Fennell Citation2011; Altshuler et al. Citation2021). However, work which explores how men engage in reproductive life events is mostly outdated or focussed on pregnancy prevention. Scoping reviews are suited to rapidly mapping literature related to a broad and relatively unexplored concept (Arksey and O'Malley Citation2005). This scoping review aims to map current literature that uses language related to reproductive work, responsibility or burdens to better understand the contemporary use of these terms and their negotiation between heterosexual partners.

Methods

Search strategy

Articles were identified by systemically searching three databases: Scopus, CINAHL and Medline (Ovid). These databases were selected as they include articles related to both the social sciences and health. Search terms () included any combination of words from column A and column B (For example fertility work, fertility burden, reproductive work, etc.).

Table 1. Search strategy.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Articles were included if they were original research, written in English, set in a high-income country and described how those in casual or committed heterosexual relationships conceptualise and negotiate responsibilities and burdens associated with any reproductive life event ().

Table 2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

The way in which reproductive goals are achieved changes over time and can be influenced through available and emerging technologies such as developments in fertility treatments and the increasing range of available contraceptive options. Therefore, we only included articles published from 2015 onwards. To allow our findings to be interpreted within similar health systems to Australia, we only included studies from high-income countries (Fantom and Serajuddin Citation2016). Where differences in health systems were identified they are contextualised in the results.

We excluded papers about populations with specific sexual and reproductive health needs such as those accessing IVF treatments, sex workers or people living with HIV, as these populations have additional needs which may influence the experience and negotiation of responsibilities. We also excluded articles written from the perspectives of health providers and papers that focused on prospective male contraceptives, as our interest was in the practices in which men engage now, rather than those that might become available in the future.

Study selection

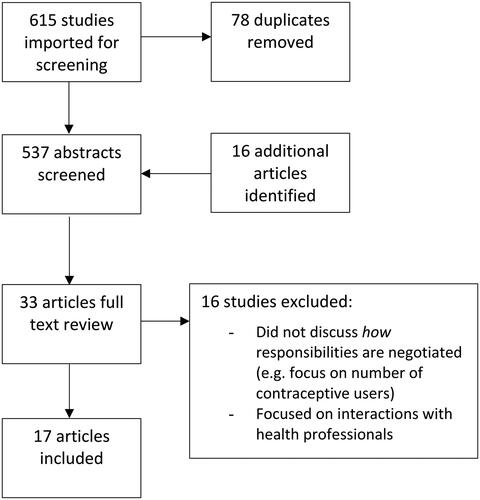

Results from the database search, conducted in November 2021, were uploaded to web platform COVIDENCE, and duplicates removed. Additional articles were identified by reviewing reference lists of relevant articles and from previous literature reviews conducted by the primary researcher (CC). The remaining articles were screened for inclusion and exclusion criteria by the primary researcher based on the title and abstract. Articles that met the full inclusion criteria were subjected to full-text screening. This process occurred in consultation with other members of the research team (MTS, JC) to ensure agreement on included articles.

Data extraction and analysis

Data from included articles were extracted into a Microsoft Word table. This detailed study aims, methodology, sample population, setting, findings and the terminology used by the researchers to describe reproductive responsibilities. Inductive content analysis (Hsieh and Shannon Citation2005) was used to analyse the included articles, facilitated by the use of NVivo (QSR International Citation2012).

The scoping review aimed to explore how reproductive responsibilities were defined by researchers and participants and how they were negotiated or shared (if at all) between heterosexual partners during any reproductive event. Inductive content analysis is an appropriate analysis technique when the aim is to describe a particular phenomenon (Hsieh and Shannon Citation2005). All articles were read in full and analysed by the primary researcher (CC). The analysis was performed iteratively across the data set with initial codes being refined as the analysis progressed. Codes were then grouped into categories to describe and reflect the meaning of the data.

All articles were then re-reviewed to ensure the analysis reflected the depth of the articles. Discrepancies in interpretation were resolved by discussion and mutual agreement within the research team.

Results

The database search identified 615 articles, of which 17 were included in this review. (). Articles were excluded if they were set in low- or middle-income countries, were not original research, explored prospective male-controlled contraceptives or targeted those with specific sexual and reproductive health needs such as those accessing IVF treatments. These populations were excluded as they have additional reproductive needs which may influence experiences of, and negotiation of, reproductive responsibilities. Details of Inclusion and exclusion criteria can be found in above.

Study characteristics

Of the 17 studies included, 14 were qualitative studies, one was a mixed-methods survey, one was a quantitative survey, and one was a scoping review of qualitative work. Most studies were conducted in the USA (n = 10), the UK (n = 4) and Australia (n = 2). The scoping review included 10 articles from multiple high-income countries. Most studies were published in social science or sexual health peer reviewed journals.

Of the qualitative studies, most used individual semi-structured interviews. Two studies used focus groups and one used a combination of these data collection methods. Studies that used surveys to collect data ranged in size from 348 participants (quantitative survey) (Gilliam et al. Citation2017) to 1,906 (mixed-methods survey) (Wigginton et al. Citation2018).

Study participants were men (n = 9), women (n = 4), or both men and women (n = 4) and of the latter, 2 included couples. The age range of participants across studies was 14–55 years, and most were identified as either low-income or upper middleclass.

Although all the papers discussed some form of reproductive responsibility, the aims and objectives of each study and the reproductive stage of life explored, varied greatly. There was some overlap in the reproductive event that articles focused upon (for example, contraception and abortion), but the primary focus of most included articles was pregnancy prevention and contraception (n = 10), STI prevention (1), abortion decision-making (1), conception (2), birth and abortion experiences (1) and sterilisation (2) (see ).

Table 3. Included studies.

Brown

Content analysis was used to identify patterns of engagement between heterosexual partners across a wide spectrum of reproductive events. Through content analysis, four major categories were identified: respecting women’s autonomy, barriers to taking responsibility, sharing responsibility, and power and masculinities.

Respecting women’s autonomy

Most male participants included in pregnancy prevention studies reported respecting their female partners’ agency and bodily autonomy, which hindered their active engagement (Hamm et al. Citation2019; James-Hawkins, Dalessandro, and Sennott Citation2019; Campbell, Turok, and White Citation2019; Fefferman and Upadhyay Citation2018; Sharp, Richter, and Rutherford Citation2015). This was highlighted in James-Hawkin, Delassandro and Sennot’s study (2019) which explored US college men’s involvement in contraceptive decision-making and pregnancy prevention. One male participant (age 18–24) was quoted as saying:

Anything that is affecting her body, hormones or whatever, it’s her decision, I mean the guy should have input. Like I want you to use this, I would like it if you were on birth control or whatever. But ultimately, I think it’s her decision (James-Hawkins, Dalessandro, and Sennott Citation2019, 270).

She didn’t tell me she took [the ring] out. She told me to pull out, so I thought it would work… . honestly, I don’t know if [she] planned [the pregnancy] or not. But it happened… . I mean, it wasn’t really my mistake since I didn’t know (Fefferman and Upadhyay Citation2018, 386).

By assigning his partner primary responsibility for contraceptive use and management, the respondent absolved himself of blame when contraception failed. This same discourse also limited men’s ability to meaningfully engage in achieving their own reproductive goals. Other studies have noted that male partners adopted a passive ‘supportive’, yet secondary role to women during reproductive events, reinforcing gendered ideas of reproductive responsibility (Fefferman and Upadhyay Citation2018; Campbell, Turok, and White Citation2019; Wilson Citation2020). In alignment with this, active engagement was at times downplayed by participants to prevent any perception of impeding their partner’s autonomy.

Just as some women expressed the desire for men to be more actively involved, others wanted control without the partner’s involvement. This was evident in reproductive life events including contraceptive management using female-controlled contraceptives and/or condoms (Wigginton et al. Citation2018), while acquiring abortion services (Altshuler et al. Citation2021), obtaining female sterilisation (Leyser-Whalen and Berenson Citation2019) and while trying to conceive (Grenfell et al. Citation2021).

Barriers to taking responsibility

Most articles highlighted structural barriers that impeded men and/or women’s ability to participate in reproductive work. These were often specific to the study location.

Lack of acceptable male-controlled contraception

Some men in studies about pregnancy prevention felt limited in their ability to take primary responsibility due to a lack of male-controlled contraceptive options (Hamm et al. Citation2019; James-Hawkins, Dalessandro, and Sennott Citation2019). Condom dissatisfaction was widely described by both men and women (Hamm et al. Citation2019; Dalessandro, James-Hawkins, and Sennott Citation2019; Campbell, Turok, and White Citation2019; Daugherty Citation2016; Brown Citation2015). Reasons for dissatisfaction included reduced sensation, vaginal drying, or their interruption to sexual intercourse. Dissatisfaction with male-controlled methods may increase reliance on female-controlled contraceptives, and increase the burdens experienced by female partners.

Financial constraints

Leyser-Whalen and Berenson’s study (2019) of low-income women accessing male or female sterilisation described how financial constraints in the USA shape participation in reproductive work. Participants reported how not having health insurance, or the availability of grants that cover only female sterilisation, as restricting men’s ability to access vasectomy (Leyser-Whalen and Berenson Citation2019). Requiring time off work to recover from vasectomy also acted as a barrier when men were the household income provider (Leyser-Whalen and Berenson Citation2019). In the UK, where access to female-controlled contraceptives under the NHS is free, men described dissatisfaction about the cost of condoms (Wilson Citation2020). Although condoms can be obtained at no charge at sexual health clinics, partners were often sceptical about their efficacy, deterring their use (Wilson Citation2020). Moreover, Fefferman and Upadhyay (Citation2018) study highlighted how factors such as gang life, periods of incarceration, and immigration policies also shaped young low-income men’s involvement in fertility work (Fefferman and Upadhyay Citation2018).

The feminisation of reproductive healthcare

The feminisation of reproductive health care and public health campaigns primarily targeted to women further constrained the ability of male partners to share fertility work. This was highlighted in Wilson’s couples’ study (2020) of men’s role in family planning with couples in the UK. Some men felt unwelcome at these services, for example, one male participant (age 21–30) was quoted as saying; ‘The family planning thing, as a bloke we’re told basically to wait outside, or here’s some condoms piss off’ (Wilson Citation2020, 31). Male participants also noted how public health campaigns were primarily directed to women.

The feminisation of healthcare also extends to the use of reproductive technologies. Many women who use fertility trackers are unaware these apps can be used simultaneously on their partners’ phones (Grenfell et al. Citation2021). Interactions with health professionals also shapes participation in reproductive work. In their scoping review, Nicholas et al. (Citation2021) described how health professionals reinforced gendered ideas of contraception in their interactions with men, either by not discussing contraception during health care visits, or by assuming men are disengaged or resistant to reproductive work, such as discussing the ‘nagging wife’ who instigates their partners vasectomy (Nicholas et al. Citation2021, 133). Leyser-Whalen and Berenson (Citation2019) also observed how health professionals could restrict women’s access to permanent sterilisation if they were ‘too young’, which may be viewed as prioritising female reproduction over individual agency. (Leyser-Whalen and Berenson Citation2019). Clinic specific policies can also act as barriers when female participants desired the presence of their male partner while accessing abortion services but this was denied, resulting in significant emotional distress (Altshuler et al. Citation2021).

Sexual health knowledge

Misinformation and fear of side effects deters men from accessing vasectomy (Leyser-Whalen and Berenson Citation2019; Nicholas et al. Citation2021; Campbell, Turok, and White Citation2019), and studies that focused on pregnancy prevention described men’s limited understanding of female-controlled contraception (Campbell, Turok, and White Citation2019; Fefferman and Upadhyay Citation2018; Gilliam et al. Citation2017; Woodhams et al. Citation2018). Many pregnancy prevention studies reported that male participants perceived the risk of unintended pregnancy with contraceptive non-use or poor adherence to be low. In low-income populations, this was sometimes aligned with a fatalistic approach to fatherhood and the belief that it was difficult to plan when and if a pregnancy would occur (Hamm et al. Citation2019; Campbell, Turok, and White Citation2019; Daugherty Citation2016).

Sharing responsibility

All included articles found that some participants, both male or female, wanted to share reproductive responsibilities. However, there was often dissonance between believing work should be shared and male participants taking action to share responsibility. There was also variability within and between studies in how participants interpreted what taking responsibility implied. For example, Wigginton et al. (Citation2018) survey of Australian women highlighted variation in women’s interpretation of ‘who took responsibility for contraception the last time you had sex’ with some women describing no-one took responsibility despite using long-acting reversible contraception, vasectomy or withdrawal. Many women also showed gendered interpretations of contraceptive responsibility, stating; ‘Pill/condoms- always. I’m responsible for my contraception (pill) and he’s responsible for his (condoms)’ (Wigginton et al. Citation2018, 7). This is reflected in other studies where men predominately discuss male-controlled methods such as condoms and withdrawal when questioned about contraception (Woodhams et al. Citation2018; Brown Citation2015; Daugherty Citation2016).

However, there were many examples in the included studies of more nuanced ways of sharing reproductive responsibilities. Altshuler et al. (Citation2021) found that companionship during birth and/or abortion could represent an important form of shared responsibility and highlighted the potential positive effects of companionship on both partners including emotional support and protection from stigma when accessing abortion (Altshuler et al. Citation2021). In terms of included studies that focused on pregnancy prevention, other examples of men sharing reproductive responsibilities included sharing the cost of contraception, ensuring contraception was used correctly (Fefferman and Upadhyay Citation2018; Wigginton et al. Citation2018), checking the position of intrauterine devices (Fefferman and Upadhyay Citation2018), sharing contraceptive decision making and dealing with contraceptive side effects (Fefferman and Upadhyay Citation2018; Campbell, Turok, and White Citation2019; Wilson Citation2020; Gilliam et al. Citation2017), encouraging partners to use contraception (Gilliam et al. Citation2017), attending health services appointments with partners (Fefferman and Upadhyay Citation2018), and initiating reproductive conversations (Gilliam et al. Citation2017). In the case of conception work, Grenfell et al. (Citation2021) found examples of men sharing reproductive responsibility through the use of fertility trackers; ‘If we forgot to do a reading it was… both of our responsibilities…[I] really appreciated that’ – woman aged 24–43 (Grenfell et al. Citation2021, 124). In some cases, women actively shaped men’s engagement by requesting their participation’: [My girlfriend] would just sort of [ask] me…can I remind her [to take the pill]’ (young male of colour aged 15–24) (Fefferman and Upadhyay Citation2018, 380).

Some studies described men taking primary responsibility for pregnancy prevention through vasectomy (Leyser-Whalen and Berenson Citation2019; Nicholas et al. Citation2021) and initiating condom use (Sharp, Richter, and Rutherford Citation2015; Campbell, Turok, and White Citation2019; Brown Citation2015; Gilliam et al. Citation2017; Wigginton et al. Citation2018). The latter was, however, in some cases motivated by the desire for self-care and STI prevention more than sharing pregnancy prevention efforts (Woodhams et al. Citation2018) Men were more likely to desire shared responsibilities in long-term compared to short-term relationships (Gilliam et al. Citation2017; Sharp, Richter, and Rutherford Citation2015).

Power and masculinities

Manhood

Many authors found participants framed the ability to procreate as central to their (or their partner’s) masculine identities, and this impacted their engagement in reproductive events. Leyser-Whalen and Berenson (Citation2019) showed how low-income women’s partners in the USA often rejected the idea of vasectomy, with women primarily attributing this to ideas of losing ‘manhood’; this was particularly true of Latina participants. As one woman (aged 24–43) described ‘Oh, because he’s one of those guys… you know how they say, ‘macho’ (Leyser-Whalen and Berenson Citation2019, 757). Nicholas et al. (Citation2021) also noted in their scoping review, less social support for vasectomy among Latino and Black men in the USA highlighting the intersecting impacts of both culture and gender on engagement in permanent sterilisation. However, Nicholas et al. (Citation2021) also describes a shift in traditional expressions of masculinity, whereby taking equal responsibility for pregnancy prevention by undergoing vasectomy, was desired by some male participants, and viewed as a sign of commitment to their family and partner. (Nicholas et al. Citation2021).

Prioritisation of men’s sexual pleasure

In studies that focused on pregnancy prevention and abortion-decision making from the perspectives of men, over half discussed men’s prioritisation of sexual pleasure over taking responsibility for pregnancy prevention. In Dalessandro, James-Hawkins and Sennott’s study (2019), class privileged college men maintained masculine ideals of spontaneous care-free sex and male pleasure by using ‘strategic silence’, or purposely avoiding conversation about contraception, until after sexual intercourse. Men assumed women were effectively using contraception, were equally motivated to avoid pregnancy, and had the financial resources to access emergency contraception or abortion if required. As one male participant (aged 18–24) said;

I feel like most men, at least my age, [believe] something like, “Oh, I just don’t want to get her pregnant, but it feels really good to have sex without a condom. She should be on birth control so I [don’t have to] use a condom (Dalessandro, James-Hawkins, and Sennott Citation2019, 782).

Several studies noted some men’s negative attitudes towards condoms, and reliance on female-controlled contraception, emergency contraception and abortion, to avoid their use (Brown Citation2015; Hamm et al. Citation2019; Campbell, Turok, and White Citation2019; Dalessandro, James-Hawkins, and Sennott Citation2019). This was despite their ability to recognise the importance of contraceptive use and was inconsistent with their desires to avoid pregnancy. Other pregnancy prevention studies illustrated some men’s complete reliance on women to manage contraception, including the initiation of condoms (Daugherty Citation2016; James-Hawkins, Dalessandro, and Sennott Citation2019; Sharp, Richter, and Rutherford Citation2015). In a US based study of men at risk of unintended pregnancy, one male participant (aged 18–25) said,

A lot of people be getting pregnant because girls ain’t on top of their job… If a female don’t want to get pregnant, it’s their job to be like, “hold up, you gonna throw a jimmy [condom] on that?” (Daugherty Citation2016, 1828).

Virility, spontaneity and conception

The papers by Hamper (Citation2021) and Grenfell et al. (Citation2021) discuss how masculine ideals of care-free sexual encounters that prioritise male pleasure, shape men’s (non)-involvement.

Well I did talk to my husband about it [fertility tracking], and he was like … don’t talk to me about it because it’ll just put me off my game, we’ll just do it and not worry about it and see what happens’ (Hamper Citation2021, 10).

Women were also sensitive of the impact on their male partners if they failed to conceive, noting the links between virility, the ability to impregnate a woman, and ideas of masculinity (Hamper Citation2021).

Discussion

This review shows how reproductive responsibilities and burdens can be shared across a range of reproductive events, as well as how barriers to engagement, and masculinities can shape involvement. Language describing reproductive responsibilities and burdens was largely used in relation to pregnancy prevention, however this review highlights how responsibilities are applicable to a wide variety of reproductive events from companionship during abortion through to use of digital technology when planning conception. Within each reproductive event, authors document similar patterns of engagement between heterosexual partners and highlight how responsibilities can be conceptualised, shared and negotiated, while acknowledging that the large proportion of reproductive work continues to fall to women.

Most participants in the selected studies, regardless of gender believed that reproductive work should be shared between partners, but there was often a dissonance between this idea and men’s active engagement. Studies highlighted complex barriers to men’s engagement including a lack of male-controlled contraceptive methods and poor sexual health knowledge. In addition to the included studies, previous research shows that men are less likely to attend health services than women (Galdas, Cheater, and Marshall Citation2005) and have less opportunities to acquire reproductive information informally through these channels. Even when men do attend health services, health providers are less likely to discuss pregnancy prevention and/or reproductive information during consults (Nicholas et al. Citation2021), and often disregard the men’s role in unintended pregnancy (Connor, Edvardsson, and Spelten Citation2018). Men’s poor sexual health knowledge has also been documented in previous research (Marshall and Gomez Citation2015; Stewart et al. Citation2017), and impedes men’s engagement in a myriad of reproductive responsibilities such as initiating conversation. Not only does this increase the burden on their female partners, it also restricts their ability to meet their own sexual and reproductive health goals.

Hegemonic masculinity is associated with a pattern of gender relations that results in the oppression of women and other subordinate masculinities (Messerschmidt Citation2019). In reproductive relationships, this presents through the unequal distribution of reproductive responsibility and risk to women. This is evident in this review when men assumed women were effectively managing contraception and could access emergency contraception or termination if required (Brown Citation2015; Daugherty Citation2016; Dalessandro, James-Hawkins, and Sennott Citation2019). Although not all men in the selected studies exhibited hegemonic behaviour, most did not challenge the prevailing distribution of reproductive work and therefore benefitted from it through complicit masculinity (Messerschmidt Citation2019). However, gender constructions are fluid and can be challenged by female partners (Connell and Messerschmidt Citation2005). Instances of women challenging the gender order were evident in the review, with some women being active in shaping their partner’s involvement in contraceptive management (Fefferman and Upadhyay Citation2018). However, this onus to educate and facilitate engagement by partners can represent another form of reproductive work that falls to women. This also overlooks the unequal gendered power within heterosexual relationships whereby some women may not feel able to challenge their partners.

When men did have the opportunity to actively engage in reproductive work many struggled with competing ideas of sharing responsibility and respecting women’s agency and bodily autonomy. This was evident both in studies of young men and those who were older (Sharp, Richter, and Rutherford Citation2015; Fefferman and Upadhyay Citation2018; Hamm et al. Citation2019). It is important to note that not all women wanted their male partners involved in reproductive decision making and female participants in some studies expressed a desire for autonomous control (Wigginton et al. Citation2018; Leyser-Whalen and Berenson Citation2019). It is also important to recognise the potential for reproductive coercion in increasing men’s engagement in reproductive responsibilities. Supporting men to engage in a respectful and collaborative manner, without extending into controlling or coercive behaviour, instances of which have been described in studies exploring reproductive coercion (Grace and Anderson Citation2018), are integral to protecting women’s bodily autonomy and reproductive rights.

Limitations

Like all research this study has its limitations. Many of the included studies discussed the experiences of partners not directly being interviewed which could have resulted in data that did not reflect the true intentions of participants partners. A few of the included studies involved couple interviews and this may have impacted what participants said. Some studies did not give full details of how many participants were involved, or provide data on participants’ ethnicity or socioeconomic status, limiting comparability and the interpretation of the data. It is possible that other papers that fit the inclusion and exclusion criteria were missed if they used terminology not identified by the search strategy. Studies written in languages other than English and published before 2015 were excluded.

Conclusion

Reproductive responsibilities and burdens occur across the reproductive life course. Assigning primary or exclusive responsibility to women discounts the part men can play in reproductive life events and contributes to unequal reproductive burdens. Men should be supported to engage in reproductive responsibilities while respecting their partners’ agency and reproductive autonomy.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Altshuler, A. L., A. Ojanen-Goldsmith, P. D. Blumenthal, and L. R. Freedman. 2021. “Going Through it Together”: Being Accompanied by Loved Ones During Birth and Abortion.” Social Science & Medicine (1982) 284:114234. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114234

- Arksey, H., and L. O'Malley. 2005. “Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 8 (1):19–32.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2021. “Census of Population and Housing: Population Data Summary, 2021.” Canberra: ABS. Online available from: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/population/

- Bearak, J., A. Popinchalk, L. Alkema, and G. Sedgh. 2018. “Global, Regional, and Subregional Trends in Unintended Pregnancy and its Outcomes from 1990 to 2014: Estimates from a Bayesian Hierarchical Model.” The Lancet. Global Health 6 (4):e380–e9.

- Bertotti, A. M. 2013. “Gendered Divisions of Fertility Work: Socioeconomic Predictors of Female versus Male Sterilization.” Journal of Marriage and Family 75 (1):13–25.

- Brown, S. 2015. “They Think it’s All Up to the Girls’: Gender, Risk and Responsibility for Contraception.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 17 (3):312–325.

- Campbell, A. D., D. K. Turok, and K. White. 2019. “Fertility Intentions and Perspectives on Contraceptive Involvement Among Low‐income Men Aged 25 to 55.” Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health 51 (3):125–133.

- Connell, R. W., and J. W. Messerschmidt. 2005. “Hegemonic Masculinity: Rethinking the Concept.” Gender & Society 19 (6):829–859.

- Connor, S., K. Edvardsson, and E. Spelten. 2018. “Male Adolescents’ Role in Pregnancy Prevention and Unintended Pregnancy in Rural Victoria: Health Care Professional’s and Educators’ Perspectives.” BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 18 (1):1–10.

- Dalessandro, C., L. James-Hawkins, and C. Sennott. 2019. “Strategic Silence: College Men and Hegemonic Masculinity in Contraceptive Decision Making.” Gender & Society 33 (5):772–794.

- Daugherty, J. 2016. “How Young Men at High Risk of Fathering an Unintended Birth Talk About Their Procreative Identities.” Journal of Family Issues 37 (13):1817–1842.

- Ekstrand, M., T. Tydén, E. Darj, and M. Larsson. 2007. “Preventing Pregnancy: A Girls’ Issue. Seventeen-year-old Swedish Boys’ Perceptions on Abortion, Reproduction and Use of Contraception.” The European Journal of Contraception & Reproductive Health Care 12 (2):111–118.

- Fantom, N. J., and U. Serajuddin. 2016. “The World Bank’s Classification of Countries by Income.” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper (7528)

- Fefferman, A. M., and U. D. Upadhyay. 2018. “Hybrid Masculinity and Young Men’s Circumscribed Engagement in Contraceptive Management.” Gender & Society 32 (3):371–394.

- Fennell, J. L. 2011. “Men Bring Condoms, Women Take Pills: Men’s and Women’s Roles in Contraceptive Decision Making.” Gender & Society 25 (4):496–521.

- Galdas, P. M., F. Cheater, and P. Marshall. 2005. “Men and Health Help‐seeking Behaviour: Literature Review.” Journal of Advanced Nursing 49 (6):616–623.

- Gilliam, M., E. Woodhams, H. Sipsma, and B. Hill. 2017. “Perceived Dual Method Responsibilities by Relationship Type Among African-American Male Adolescents.” The Journal of Adolescent Health 60 (3):340–345.

- Grace, K. T., and J. C. Anderson. 2018. “Reproductive Coercion: A Systematic Review.” Trauma, Violence & Abuse 19 (4):371–390.

- Grenfell, P., N. Tilouche, J. Shawe, and R. S. French. 2021. “Fertility and Digital Technology: Narratives of Using Smartphone App ‘Natural Cycles’ While Trying to Conceive.” Sociology of Health & Illness 43 (1):116–132.

- Hamm, M., M. Evans, E. Miller, M. Browne, D. Bell, and S. Borrero. 2019. “It’s Her Body”: Low-income Men’s Perceptions of Limited Reproductive Agency.” Contraception 99 (2):111–117.

- Hamper, J. 2021. “A Fertility App for Two? Women’s Perspectives on Sharing Conceptive Fertility Work with Male Partners.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 24 (12):1–16.

- Hsieh, H.-F., and S. E. Shannon. 2005. “Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis.” Qualitative Health Research 15 (9):1277–1288.

- James-Hawkins, L., C. Dalessandro, and C. Sennott. 2019. “Conflicting Contraceptive Norms for Men: Equal Responsibility Versus Women’s Bodily Autonomy.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 21 (3):263–277.

- Keogh, L. A., L. C. Gurrin, and P. Moore. 2021. “Estimating the Abortion Rate in Australia from National Hospital Morbidity and Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme Data.” The Medical Journal of Australia 215 (8):375–376.

- Kimport, K. 2018a. “More than a Physical Burden: Women’s Mental and Emotional Work in Preventing Pregnancy.” Journal of Sex Research 55 (9):1096–1105.

- Kimport, K. 2018b. “Talking About Male Body-based Contraceptives: The Counseling Visit and the Feminization of Contraception.” Social Science & Medicine (1982) 201:44–50. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.01.040

- Leyser-Whalen, O., and A. B. Berenson. 2019. “Situating Oneself in the Intersectional Hierarchy: Racially Diverse, Low-income Women Discuss Having Little Agency in Vasectomy Decisions.” Sex Roles 81 (11-12):748–764.

- Marshall, C., and A. M. Gomez. 2015. “Young Men’s Qwareness and Knowledge of IUDs in the United States.” Contraception 92 (4):383.

- Merkh, R. D., P. G. Whittaker, K. Baker, L. Hock-Long, and K. Armstrong. 2009. “Young Unmarried Men’s Understanding of Female Hormonal Contraception.” Contraception 79 (3):228–235.

- Messerschmidt, J. W. 2019. “The Salience of “Hegemonic Masculinity.” Men and Masculinities 22 (1):85–91.

- Nicholas, L., C. E. Newman, J. R. Botfield, G. Terry, D. Bateson, and P. Aggleton. 2021. “Men and Masculinities in Qualitative Research on Vasectomy: Perpetuation or Progress?” Health Sociology Review 30 (2):127–142.

- Organon. 2022. “Impact of Unintended Pregnancy.” In Online: Organon.

- QSR International. 2012. “NVivo Qualitative Data Analysis Software.” QSR International Pty Ltd.

- Richters, J., S. Fitzadam, A. Yeung, T. Caruana, C. Rissel, J. M. Simpson, and R. O. de Visser. 2016. “Contraceptive Practices Among Women: The Second Australian Study of Health and Relationships.” Contraception 94 (5):548–555.

- Rowe, H., S. Holton, M. Kirkman, C. Bayly, L. Jordan, K. McNamee, J. McBain, V. Sinnott, and J. Fisher. 2016. “Prevalence and Distribution of Unintended Pregnancy: The Understanding Fertility Management in Australia National Survey.” Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health 40 (2):104–109.

- Sharp, E., J. Richter, and A. Rutherford. 2015. “Um… I’m Pregnant.” Young Men’s Attitudes Towards Their Role in Abortion Decision-Making.” Sexuality Research and Social Policy 12 (2):155–162.

- Stewart, M., T. Ritter, D. Bateson, K. McGeechan, and E. Weisberg. 2017. “Contraception–What About the Men? Experience, Knowledge and Attitudes: A Survey of 2438 Heterosexual Men Using an Online Dating Service.” Sexual Health 14 (6):533–539.

- Wigginton, B., M. L. Harris, D. Loxton, and J. Lucke. 2018. “Who Takes Responsibility for Contraception, According to Young Australian Women?” Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare 15:2–9. doi:10.1016/j.srhc.2017.11.001

- Wigginton, B., M. L. Harris, D. Loxton, D. Herbert, and J. Lucke. 2015. “The Feminisation of Contraceptive Use: Australian Women’s Accounts of Accessing Contraception.” Feminism & Psychology 25 (2):178–198.

- Wilson, A. D. 2020. “British Couples’ Experiences of Men as Partners in Family Planning.” The Journal of Men’s Studies 28 (1):22–44.

- Woodhams, E., H. Sipsma, B. J. Hill, and M. Gilliam. 2018. “Perceived Responsibility for Pregnancy and Sexually Transmitted Infection Prevention Among Young African American Men: An Exploratory Focus Group Study.” Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare 16:86–91. doi:10.1016/j.srhc.2018.02.002