Abstract

Good quality patient care requires health care providers to respect the humanity and autonomy of their patients. However, this is not achieved in all settings. This study used cross-sectional survey data including open-ended text responses to explore negative experiences with health care providers among women in Appalachia. We used the Heath Stigma & Discrimination Framework (HSDF) to identify how stigma is created and perpetuated through interactions with health care providers. Survey data from 628 women collected through purposive sampling identified that two out of three participants had had a bad encounter with a provider that made them not want to return for care. One in six participants had a negative experience specifically while seeking contraception. Using the domains of the HSDF framework, qualitative answers to open-ended questions illuminated how health care providers, influenced by social and cultural norms related to religiosity, patriarchal views, poverty, poor health infrastructure, and the opioid crisis, created and perpetuated stigma through dehumanising treatment, low-quality care, and health care misogyny. Because stigma is a driver of health inequity, these findings highlight the important and sometimes problematic role that health care providers can play when they create a barrier to future care through poor treatment of patients.

Introduction

Interactions and experiences with health care providers are core components of health care delivery that affect health-seeking behaviours, as they can either enhance or impair trust between an individual, their health care provider, and the larger health care system (Murray and McCrone Citation2015). Health care that respects, protects and supports autonomy is a critical component of achieving quality patient care (AHRQ Citation2022; Hardee et al. Citation2014); however, it is not uncommon for health care providers to be a source of mistreatment. For example, research has highlighted problematic provider behaviour related to misgendering patients who identify as trans and providing poor quality care to certain racial or ethnic groups or individuals who use drugs (Siddiqui Citation2022; Seelman et al. Citation2021; Knight et al. Citation2019).

Furthermore, care that involves an element of labelling, stereotyping, separation, status loss, or discrimination can introduce stigma and damage the patient-provider relationship (Hatzenbuehler, Phelan, and Link Citation2013). Stigma resulting from a negative interaction with a health care provider can be especially harmful because stigma contributes to health inequities due to its disruption of resources, relationships and coping behaviours (Hatzenbuehler, Phelan, and Link Citation2013). Mistreatment by health care providers can be compounded by existing health access problems (Holmes et al. Citation2020), especially in regions like Appalachia where health care is challenging to find and options may be limited by resources and geography.

The Appalachian region of the USA, which spans 423 counties over 13 states (ARC Citation2021), is well-known for widespread poverty that result from decades of systemic economic oppression and regional exploitation (Baird Citation2014). Appalachian counties have disproportionately worse health outcomes than US counties as a whole due to multiple barriers to care access, including a lower number of providers per capita, long travel distances, lack of specialists, and more recently, the impacts of the opioid crisis (Marshall et al. Citation2017; Meit, Heffernan, and Tanenbaum Citation2019). Engaging in care related to topics such as reproductive health, may worsen the experience of health stigma. Data from focus groups with stakeholders in Appalachia suggest that stigma and mistreatment from health care providers and the local community makes seeking family planning services difficult or unappealing (Swan et al. Citation2020).

The relationship between the health provider, who has coveted knowledge and resources, and the patient, who needs both, can be problematic (Odero et al. Citation2020), especially in a country where health care is viewed as a commodity instead of a right (Alspaugh et al. Citation2021). Poor treatment within health settings can affect willingness to return not only to that provider but to seek health services more generally (Murray and McCrone Citation2015). Negative experiences with health care providers can thereby impacting long-term health and wellness. These experiences carry ramifications that go beyond individuals and impact entire groups and communities (Alsan, Wanamaker, and Hardeman Citation2020).

Because reproductive health care is stigmatised, it is prone to harmful health provider practices (Hussein and Ferguson Citation2019). Mistreatment of women and pregnancy-capable people in health care settings has a long history (Cleghorn Citation2021). Researchers point to gender inequity and gender norms and expectations as one of the root causes of mistreatment during pregnancy and birth, working at a structural level to both create and normalise mistreatment by health care providers (Betron et al. Citation2018). Because gender bias is one of the central drivers of obstetric mistreatment, it follows that gender bias will also influence other aspects of reproductive care, such as contraception and abortion, as well as health care generally (Chemlal and Russo Citation2019; Harris, Reichenbach, and Hardee Citation2016; Holt et al. Citation2017). The literature on bias in patient-provider relationships remains limited especially with respect to non-obstetric reproductive health (Berndt and Bell Citation2021).

Appalachia, in particular, has a unique combination of infrastructure and social factors that can make health-seeking experiences challenging. While Appalachian physical infrastructure issues are well-characterised (Marshall et al. Citation2017), social factors are less understood. To address this knowledge gap, we analysed quantitative and qualitative data from a survey of Appalachian women and pregnancy-capable people. The following research questions guided the analysis: (1) how common are negative experiences among Appalachian women while seeking health care, generally, and with respect to birth control, specifically; and (2) what is the nature of these experiences, as described by participants?

Theoretical framework

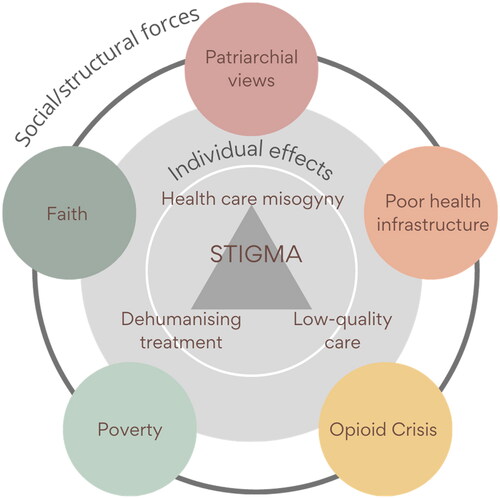

The Health Stigma and Discrimination Framework (HSDF) was used to frame the study focus, develop research questions, analyse data, and discuss the findings. This framework identifies how stigmatisation occurs across several domains (Stangl et al. Citation2019). The first domain, drivers and facilitators, refers to how stigma is created by social processes and norms. The second domain, stigma marking, shows how stigma links to a variety of factors, including race, class and gender. Often, individuals are ‘marked’ by multiple forms of stigma, such as class and race, creating intersecting forms of stigma. Once applied to an individual or group, specific practices and experiences become stigmatised, which encompasses the third domain, manifestations. Manifestations can include experiences of stigma, anticipated stigma, stereotypes, and discriminatory behaviours and attitudes. Such manifestations affect a variety of outcomes, the fourth domain, including the accessibility and acceptability of health care services (Stangl et al. Citation2019). Ultimately, mistreatment by health care providers is a symptom of broader social and cultural forces, which are rooted in systems and structures of sexism, classism, racism, ableism, capitalism, and other forms of oppression.

Materials and methods

Participants and procedures

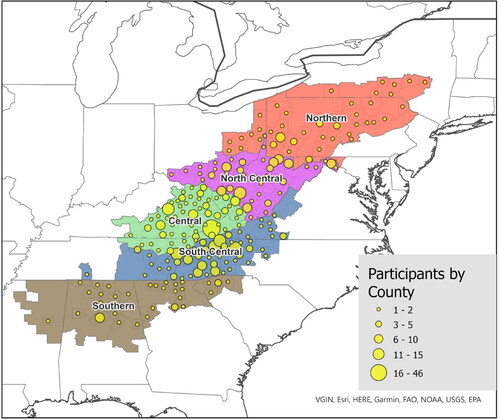

In November 2019, we recruited a purposive sample using Facebook advertisements targeting people residing in Appalachian zip codes and engaging Facebook groups of interest to Appalachian people (e.g. Appalachian Americans). Interested participants clicked on the advertisement which took them out of Facebook and into a secure survey platform (REDCap) to complete the survey anonymously. At the end of the survey, participants were able to receive a $10 gift card as compensation for their time. This method of using Facebook for survey recruitment was chosen because research suggests that Facebook is widely used by Appalachian populations, especially women and rural residents (Auxier and Anderson Citation2021; Dickson et al. Citation2017; Staton et al. Citation2022). Research has also previously established Facebook as being useful for rural intervention delivery, targeted research on sensitive topics, and recruitment of difficult-to-access Appalachian residents (Whitaker, Stevelink, and Fear Citation2017; Dickson et al. Citation2017). This strategy allowed for concurrent recruitment from across all Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC)-defined Appalachian subregions, which has been historically difficult to accomplish due to geographic inaccessibility (Pollard and Jacobsen Citation2021).

Inclusion criteria were as follows: age 18–49 years; assigned female at birth and pregnancy capable; and resident in an Appalachian zip code. The survey was available for four days until 1,202 responses had been collected. After the study closed, responses were carefully screened, using recommended fraud detection techniques, resulting in the removal of cases that suggested ‘bot’ type activity or other fraudulent activity (Ballard, Cardwell, and Young Citation2019; Teitcher et al. Citation2015; Griffin et al. Citation2022). Fraud detection measures included analysis of survey metadata for survey completion times and removal of any survey completed in under twenty minutes or greater than two hours (Teitcher et al. Citation2015; Griffin et al. Citation2022). Duplicate and/or automatically generated email addresses with particular patterns were flagged as fraudulent and were eliminated (Ballard, Cardwell, and Young Citation2019). The remaining data were screened for nonsense responses or for surveys that contained exact duplicate responses. The study procedures were approved by the University of Buffalo’s Institutional Review Board.

Measures

The survey questionnaire was developed by the research team to examine community perceptions of unmet family planning needs in the greater Appalachian region, and included existing measurement tools as well as items created specifically for the study. Included items were based on topics relevant to Appalachian community stakeholders, as ascertained in a series of tele-conference focus groups (Swan et al. Citation2020) and the existing literature. The survey included items measuring demographic characteristics as well as individual and community-level experiences related to health care access, family planning, substance use, and health-seeking behaviours.

Demographic factors

We included several demographic factors in our analysis: age, income, health insurance status, race/ethnicity, marital status and education level. Age was a continuous variable ranging from 19 to 49 years. We asked participants their annual household income before tax, with response options ranging from 1 to 6 ($0–$14,999 = 1, $15,000–$29,000 = 2, $30,000–$49,000 = 3, $50,000–$69,000 = 4, $70,000–$100,000 = 5, $100,000 or more = 6). We measured health insurance and marital status dichotomously. We asked participants about their highest level of education and collapsed responses into four categories: some or all of high school; associate degree, some college, or trade school; bachelor’s degree; and some graduate school or a graduate degree. We asked participants what race/ethnicity they identified as. Due to low frequencies of Black/African American (n = 21), Asian/Pacific Islander (n = 3), Latina/o/x (n = 6), Native American/American Indian (n = 9), and other (n = 24), we collapsed these categories into one ‘non-white’ group.

Negative health care experiences

Participants were asked if they had had ‘bad experiences’ with a health care provider that made them not want to return for care, assessed separately for general health care settings and while seeking birth control (no/don’t know = 0; yes = 1). We then asked participants if they had ever been treated badly when seeking health care (with separate items for seeking general health care and for seeking birth control) due to their income, race, Appalachian identity, weight or gender (gender was only asked for general health care and not for birth control seeking, specifically). For each of these items, we coded responses as ‘yes’ (=1) or ‘no’/'don’t know’ (=0). To explore possible intersections of identity-based maltreatment in health care, we also created an ordinal variable that indicates the number of reasons perceived by participants as the cause of their mistreatment (0 = none, 1 = one, 2 = multiple). We then asked any participant who reported these ‘bad experiences’ to describe their experience by selecting from a list of options and/or writing an open-ended response.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the study sample and the frequency of negative health care experiences, differentiating between encounters in general health care settings and those experienced while seeking birth control. We also used bivariate analyses to explore the intersections of identity-based maltreatment in health care. Then, we conducted a qualitative analysis of open-ended responses to questions about bad experiences in general health care and while seeking birth control, as well as two other open-ended probes (‘What are the most important things you would like us to know about health care in your community?’ and ‘What do you think is needed in your community to help people use birth control more often, even when there are problems with community drug use?’).

Responses to open-ended questions informed the creation of a conceptual map (). Next, the first and fourth authors deductively analysed the open-text responses using directed content analysis as applied by Hsieh and Shannon (Citation2005) using the Health Stigma and Discrimination Framework (Stangl et al. Citation2019). We assigned codes to the four domains identified by the theoretical framework, with subcategories taken from the conceptual map. During analysis, we inductively created a sub-category within the HSDF domain of ‘Outcomes’, which we labelled ‘the care we deserve’ to capture participant recommendations on preventing health care mistreatment and stigma, which spoke to the outcomes of advocacy and resilience. Both authors coded independently, met to confirm findings, and reconciled discrepancies through consensus. Credibility was ensured by member reflexivity and coanalysis (Morrow Citation2005).

Results

Demographic characteristics

shows the demographic characteristics of this sample of women and pregnancy-capable individuals. One participant identified as a trans man assigned female at birth; all other participants identified as cisgender women. Participants’ mean age was 33.7 years (SD = 6.6), and the average annual household income was between $30k and $69k. Most participants had health insurance (n = 563, 89.8%) and identified their race/ethnicity as white (n = 564, 89.8%). A comparison of our sample to the demographic characteristics of Appalachia more generally is made in . shows a map of where participants lived within Appalachia, as organised by zip code.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of Appalachian women of reproductive age (N = 628).

Frequency and description of negative health care experiences

As shown in , two-thirds of participants reported negative experiences when seeking general health care (n = 418, 66.9%) and roughly one in six participants reported negative experiences while seeking birth control (n = 98, 15.7%). Participants most often perceived that negative experiences in health care or contraceptive care were due to their weight (health care: n = 224, 35.8%; birth control: n = 115, 18.6%) or income (health care: n = 210, 33.6%; birth control: n = 122, 19.6%).

Table 2. Frequency of negative experiences in health care among Appalachian women of reproductive age (N = 628).

Many participants (n = 228, 36.9%) perceived their mistreatment in general health care settings as related to holding multiple marginalised identities, and bivariate analyses were used to explore the intersections of identity-based maltreatment in health care. Individuals with more than one perceived reason for mistreatment in general health care were significantly more likely to report not feeling listened to (χ2(2) = 44.44, p < 0.001), not feeling comfortable with the provider (χ2(2) = 20.79, p < 0.001), and feeling that the provider was rude/condescending (χ2(2) = 74.27, p < 0.001). More than one perceived reason for mistreatment while seeking birth control was significantly associated with difficulty understanding birth control options (χ2(2) = 23.66, p < 0.001), not being offered all birth control options (χ2(2) = 34.80, p < 0.001), being denied birth control by a provider (χ2(2) = 30.06, p < 0.001), being refused any birth control by a provider (χ2(2) = 7.01, p = 0.030), being refused the preferred birth control method (χ2(2) = 54.20, p < 0.001), feeling forced by a provider to use birth control (χ2(2) = 78.63, p < 0.001), feeling pressured by a provider to use birth control (χ2(2) = 33.09, p < 0.001), feeling pressured by a provider not to use birth control (χ2(2) = 16.99, p < 0.001), and being refused birth control by a pharmacist (χ2(2) = 16.65, p < 0.001).

The most common type of negative health care experience was encountering rude or condescending providers (n = 311, 49.5%), although not feeling listened to (n = 246, 39.2%) and feeling uncomfortable with the provider (n = 190, 30.3%) were also common. In contraceptive care, the most common experience was pressure from health care providers to use birth control, which was reported by over a quarter of participants (n = 164, 27.4%). Additionally, 42 participants (6.7%) reported that a provider tried to force them to use birth control. Although just under 2% of participants reported being denied any form of birth control (n = 11, 1.8%), about 6% reported that a provider refused them their preferred contraceptive method (n = 38).

Qualitative descriptions of negative health care experiences

Findings from the open-ended prompts helped identify how mistreatment and stigma from health care providers impacted women and pregnancy-capable people in Appalachia. In line with our guiding framework, we have organised our findings across four domains: (1) stigma drivers, (2) stigma marking, (3) stigma manifestations, and (4) outcomes.

Stigma drivers

We identified five sub-categories of stigma drivers in the open-text responses: patriarchal views, religiosity, poor health care infrastructure, poverty, and the opioid crisis. Patriarchal views were experienced at a community level and through individual interactions. Participants described how ‘women’s health’, especially reproductive health, was marginalised in their community because of commonly held attitudes regarding sexuality and anti-abortion or anti-contraception sentiments. Participants also described patriarchal interactions with health care providers in which the providers talked about how many children women should have or required that they seek spousal consent for birth control. Patriarchal views and the influence of religion and faith were difficult to disentangle, as each facilitated and supported the other. Participants wrote about the ways in which providers’ religious beliefs, as well as religious norms within the community, influenced what was and was not deemed acceptable. Tenets of abstinence outside of marriage were noted by participants as a collective norm that influenced sexual and reproductive health knowledge and care. One participant wrote, ‘Here in the South we are taught abstinence, abstinence, abstinence, so when you do decide you are ready to have sex you don’t really know what or how to talk to your doctor’ (30s, white, South Central Appalachia). Participants noted a lack of education and awareness of reproductive health in their community, which they perceived to be a result of the stigma and shame placed on reproductive health and sexuality.

Participants described poverty, both their own lack of financial resources and poverty within their community, as influencing the ability to seek health care. For example, women described being unable to seek health care because of affordability issues or outstanding medical debt that rendered them ineligible for care. Limited economic resources were exacerbated by what was described as a poor health care infrastructure. Participants wrote about lack of choice regarding their provider, especially if they were uninsured. Further, some providers were difficult to access geographically, had limited office hours, or did not take public insurance. Some participants felt that the profit-driven model of health care positioned patients and their needs as secondary to making money. Small hospital closures and growing hospital monopolies in many Appalachian regions (e.g. Ballad Health in South Central Appalachia) were also noted by participants who were unsatisfied with their ability to seek high-quality care when it was needed. Both poverty and poor health infrastructure had the effect of making participants feel undervalued or unworthy of care. One participant summed up the cumulative impact of poverty and health access, writing, ‘the barriers to healthcare for women in Appalachia are many. Affordable, safe and convenient care is missing in many areas of the region and many women in the region are accustomed to doing without so that others in the family can have basics’ (40s, white, South Central Appalachia).

The unique impacts of the opioid crisis in Appalachia were noted by many. Participants wrote of an opioid-related stigma that was bidirectional: directed both at and from health care providers. Several participants mentioned a lack of trust in health care providers after understanding their role in the opioid crisis. Others reported that health care providers treated patients differently in the wake of the opioid crisis, not taking reports of pain seriously or othering people in Appalachia when they sought care. One participant wrote, ‘Patients seeking medical treatment in rural areas [are] treated with less respect due to the influx of drug abusers’ (20s, white, North Central Appalachia). Taken together, these five societal influences create an environment that was hostile to women and pregnancy-capable people, sexuality and health-seeking behaviours.

Stigma marking

Stigma marking was also noted by participants, who described comments from health care providers regarding patients’ weight, drug use and sexual activity. One participant shared a story about seeking care for endometriosis, writing that the nurses ‘insisted on a pregnancy test even when I had completed paperwork and told them verbally that I was a virgin. I was 18. Then when they realised I was serious and that I was not pregnant they laughed and called me a “unicorn”’ (30s, white, South Central Appalachia). This quote illustrates how patriarchal and religious norms about sexual activity had been internalised by the nursing staff and manifested in marking this individual with stigma. Multiple participants shared that health care providers judged them and/or did not believe they had not yet had sex. Even when participants avoided sexual activity, as prescribed by the community, once marked as ‘other’ or as deviating from the norm, they were not believed.

Stigma manifestations

Participants described stigmatised experiences involving health care providers that fitted into three sub-categories: dehumanising treatment, health care misogyny, and low-quality care. Dehumanising treatment from health care providers describes instances where patients were not treated with respect, where patients lacked autonomy over their health care decisions or were ignored, and where patients did not have their concerns taken seriously or were not informed of all their options. One participant wrote about the difficulty obtaining contraception, saying, ‘The local health department employs local people who are very judgemental. There is no place to go and have privacy’ (30s, white and Indigenous, South Central Appalachia). Others spoke of fearing health care encounters because of stigma and mistreatment related to current or previous drug use.

When health care mistreatment was rooted in bias against women and pregnancy-capable people, it was categorised as health care misogyny. One participant talked about difficulty finding care when suffering from postpartum depression, saying, ‘I was 7 weeks post-partum and I've struggled with my mental health for years. [The health care provider] even apologised to my partner for having to “deal with me”’ (20s, white, South Central Appalachia). Another participant specifically connected how unchallenged sexism impacted her and her partner’s ability to get HPV testing, writing, ‘Sexism impacts care, e.g. I've had two male partners that were refused HPV testing because it’s invasive but tests for females for HPV are very invasive’ (40s, white, North Central Appalachia). Several other participants noted mistreatment during pelvic examinations or while giving birth that went ignored by health care providers. In other cases, participants wrote about conversations in which a provider ‘slut-shamed’ them or blamed their experience of rape on their looks. One participant reported experiencing a sexual assault perpetrated by a health care provider.

Participants also wrote of the ubiquity of poor-quality health care in their community. Specifically, participants mentioned lack of knowledge on the part of providers, overcrowded clinics with short visit times, and problems that went overlooked until worse outcomes developed. One participant wrote, ‘A lot of people in my community don’t trust the doctors we have here or the hospital because they or their family have received bad care’ (no age given, white, Central Appalachia). Stories of low-quality care are shared with friends and family, potentially influencing perceptions of care among entire social networks. Many participants felt that health providers were either ill-equipped or uninterested in addressing their health concerns, citing monetary gain as a primary driver among providers. This perception was tied to knowledge of incentives paid to providers who prescribed/over-prescribed opioids.

Outcomes

The outcomes of stigmatised care centred on access to services, including affected populations and the care they deserved. For example, those seeking mental and reproductive health services were especially affected by stigma, as care was doubly difficult to access, due both to logistics and long-standing stigma and shame within the community. Participants noted that abortion was not a viable option because of cost or excessive travel time to find services, while others noted that perinatal care and birth services were unavailable in their community.

One participant noted that, because of the cost of contraception, she felt sterilisation was the only viable option to avoid an accidental pregnancy; she indicated that she would not have selected this permanent option if she had access to affordable reversible or user-dependent contraception. One participant noted that seeking health care was often an option of last resort, saying, ‘Due to stigma and mistrust attached to doctors and the like, a lot of people in my community wait until there is no other alternative except seeking medical care’ (40s, white, Central Appalachia).

Participants offered suggestions on how to improve care experiences to better reflect the care they deserved. One participant requested ‘better outreach with less judgement, & outreach that doesn’t involve religion’ (20s, white, North Central Appalachia). Others felt that laws that did not punish pregnant parents or threaten custody of their children for seeking alcohol and drug dependency treatment would be beneficial to their community. Overwhelmingly, participants noted the need for education, access and lack of judgement and stigma from providers and communities about sexual activity and drug use.

Discussion

These findings describe the frequency and nature of negative experiences of Appalachian women and pregnancy-capable people in our study. Almost two-thirds of participants in the survey reported a bad experience with a health care provider that made them not want to return for care, and almost one in six participants reported a negative experience specifically while seeking contraceptive services. Personal stories of these interactions, interpreted through the lens of the HSDF, illuminated the ways in which social and cultural stigma can impact individuals through interactions with health care providers and facilitated a deeper understanding of the progression from stigma drivers to stigma marking to stigma manifestations and outcomes among women in Appalachia.

Many of these findings align with findings from the focus group research that informed the development of this survey (Swan et al. Citation2020). Participants in this previous research identified provider bias, the influence of stigma and fear of judgement, and lack of trust in health care providers as influencing community members’ ability to seek reproductive health and treatment for opioid use disorder. This current patient-focused study confirms these findings but builds on previous research by describing the ways in which stigma influences health care experiences from the patient’s point of view. These findings also elaborate on the double bind that women in conservative or rural settings navigate, trying to square the pressure to control fertility with societal constraints in a regional setting that minimises female agency and autonomy while stigmatising contraception and abortion. We assert that the influence of cultural narratives and corresponding structural barriers impeded participants in our study from asserting their full reproductive autonomy (Kimport Citation2021).

The impact of stigma on reproductive health has been well studied (Hussein and Ferguson Citation2019; Valentine et al. Citation2021), but the Appalachian region is less commonly included in this work. One previous study exploring decision-making regarding abortion in rural, Central Appalachia found that respondents with historically positive experiences with health care providers reported confidence that their health needs, including abortion, would be met (O’Donnell et al. Citation2018). Conversely, individuals who did not receive support for abortion from their provider saw this as a barrier to obtaining abortion services. Positioning our findings within the framework of health-seeking behaviour, mistreatment and stigma at the hands of health care providers may be a significant barrier to reproductive autonomy. Further, an international systematic review found that fear of mistreatment from health care providers was a reason that women and pregnancy-capable people seek abortion care outside of mainstream health services, even when abortion is legal (Chemlal and Russo Citation2019). Our results provide much-needed evidence of the impact of stigma on reproductive health experiences in the Appalachian region.

Findings from this study also identify the intersections of multiple forms of stigma manifested in the treatment of patients by their health care providers. For example, respondents holding multiple marginalised identities reported higher rates of perceived mistreatment, were more likely to report not feeling listened to or have a provider that was rude or condescending, and were less likely to have full reproductive autonomy while selecting contraception. The relationship between health care providers and patients can be problematic even in the absence of malintent because of the way providers situate patients within systems of normative accountability (Mann Citation2022). Participants who reported negative interactions with providers while seeking contraception reported feeling pressured to use birth control and, less commonly, also pressured not to use birth control. Similarly, participants reported poor treatment related both to sexual activity and abstaining from sex, indicating that stigma regarding sexuality may be more firmly rooted in misogyny than any kind of sexual morality. These seemingly contradictory findings provide examples of the stratified reproduction manifested in Appalachia, whereby the sexuality, fertility, reproduction and maternity of some people are valued, and the fertility of others is not (Ginsburg and Rapp Citation1995). Our qualitative findings also support this notion, especially among participants with current or previous drug use, who reported more judgement and less autonomy regarding their family planning decisions, including avoiding or attaining pregnancy.

Not only did participants describe how their difficulties accessing health care services related to stigma and mistrust of providers, but they also took the time to document the care they deserved. While a wealth of negative stereotypes of Appalachia exist nationally, those living within Appalachia show great resiliency and self-sufficiency in the face of prolonged economic exploitation and often unchallenged marginalisation (Denham Citation2016). Appalachians are experts in their own needs and concerns, and these findings suggest several solutions to improving regional health and wellness. Participants explicitly described ways of stopping the cycles of mistreatment and stigma surrounding their reproductive health care: access to comprehensive sexual and reproductive education and resources, less judgement from providers, and removing the influence of patriarchal views and religiosity from health care services. With the recent US Supreme Court ruling that eliminated the constitutional right to abortion, large numbers of Appalachians have lost all access to abortion services and will likely see further limitations on contraception, including emergency contraception (Guttmacher Institute Citation2022). It is challenging to see how participants’ view of their desired patient-centred care fits within the social, cultural and now increasingly, political forces that hinder their reproductive and bodily autonomy (Paltrow, Harris, and Marshall Citation2022). Recommendations to improve reproductive health experiences, in addition to those provided by participants, include grounding care in the tenets of both person-centred care and reproductive justice (Ross and Solinger Citation2017). Providers should be especially attuned to inherent power imbalances between providers and patients, as true person-centred care cannot be fully realised without addressing this hierarchy in health care (Berndt and Bell Citation2021).

Strengths and limitations

This research has several important strengths. It is one of very few studies solely focused on the experience of mistreatment at the hands of health care providers in Appalachia, where the inherent power imbalances between the health provider and the patient can become a source of harm. Furthermore, there is little research specific to reproductive health care in Appalachia, a large and diverse region that contains a strong regional identify and many shared beliefs (Cooper, Knotts, and Elders Citation2011; ARC Citation2021). Our results establish a baseline frequency of these issues in Appalachia and support and expand understanding of quantitative findings on mistreatment by health care providers. Finally, the theoretical underpinnings of the analysis enabled a more holistic and meaningful explanation of how stigma, discrimination and mistreatment affect individuals seeking care.

There are however also important limitations to this research. The qualitative findings derive from open-ended responses, which precluded follow-up questions and probes that might further explain an answer. Additionally, we selected participats using purposive sampling, meaning that the quantitative findings may not be generalisable to elsewhere in Appalachia or beyond. Recruitment via Facebook precluded the ability to confirm findings via member checking. This method of recruitment also meant that the demographics of our sample skewed whiter, better educated, and wealthier than is the norm for Appalachia. Future research should focus on establishing the prevalence of negative health care experiences using more rigorous sampling strategies. Over-sampling underrepresented racial, ethnic, sexuality and gender minority groups in future research could help ensure that the diverse voices of Appalachia are captured.

Conclusion

Documenting poor treatment in health care and understanding how stigma, discrimination and mistreatment by health care providers are created and maintained is critical because stigma is a root cause of health inequities (Hatzenbuehler, Phelan, and Link Citation2013). Patients’ and community members’ negative experiences can impact future health-seeking behaviour, potentially to the detriment of their health and the health of their community (Alsan, Wanamaker, and Hardeman Citation2020). It is improbable to think we will ever be able to deliver health care that is entirely free of bias, as bias is deeply rooted in social and cultural norms. What we can do, however, is ensure that we develop accountability measures and methods to ensure that health care providers are held accountable for their behaviours in an effort to reduce future harm to individuals and the communities they serve (Chambers et al. Citation2022).

Declaration of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Additional information

Funding

References

- AHRQ (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality). 2022. “Six Domains of Health Care Quality.” Accessed July 18, 2022. https://www.ahrq.gov/talkingquality/measures/six-domains.html

- Alsan, M., M. Wanamaker, and R. R. Hardeman. 2020. “The Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis: A Case Study in Peripheral Trauma with Implications for Health Professionals.” Journal of General Internal Medicine 35 (1): 322–325.

- Alspaugh, A., N. Lanshaw, J. Kriebs, and C. Van Hoover. 2021. “Universal Health Care for the United States: A Primer for Health Care Providers.” Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health 66 (4): 441–451.

- ARC (Appalachian Regional Commission). 2021. “About the Appalachian Region.” Accessed March 21, 2022. https://www.arc.gov/about-the-appalachian-region/

- Auxier, B., and M. Anderson. 2021. “Social Media Use in 2021.” Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech (blog). April 7, 2021. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2021/04/07/social-media-use-in-2021/.

- Baird, S. 2014. “Stereotypes of Appalachia Obscure a Diverse Picture.” NPR, April 6, 2014. https://www.npr.org/sections/codeswitch/2014/04/03/298892382/stereotypes-of-appalachia-obscure-a-diverse-picture

- Ballard, A. M., T. Cardwell, and A. M. Young. 2019. “Fraud Detection Protocol for Web-Based Research Among Men Who Have Sex With Men: Development and Descriptive Evaluation.” JMIR Public Health and Surveillance 5 (1): e12344.

- Berndt, V. K., and A. V. Bell. 2021. “‘This Is What the Truth Is’: Provider-Patient Interactions Serving as Barriers to Contraception.” Health 25 (5): 613–629.

- Betron, M. L., T. L. McClair, S. Currie, and J. Banerjee. 2018. “Expanding the Agenda for Addressing Mistreatment in Maternity Care: A Mapping Review and Gender Analysis.” Reproductive Health 15 (1): 143.

- Chambers, B. D., B. Taylor, T. Nelson, J. Harrison, A. Bell, A. O'Leary, H. A. Arega, S. Hashemi, S. McKenzie-Sampson, K. A. Scott, et al. 2022. “Clinicians’ Perspectives on Racism and Black Women’s Maternal Health.” Women’s Health Reports 3 (1): 476–482.

- Chemlal, S., and G. Russo. 2019. “Why Do They Take the Risk? A Systematic Review of the Qualitative Literature on Informal Sector Abortions in Settings Where Abortion Is Legal.” BMC Women’s Health 19 (1): 55.

- Cleghorn, E. 2021. Unwell Women: Misdiagnosis and Myth in a Man-Made World. New York: Dutton.

- Cooper, C. A., H. G. Knotts, and K. L. Elders. 2011. “A Geography of Appalachian Identity.” Southeastern Geographer 51 (3): 457–472.

- Denham, S. A. 2016. “Does a Culture of Appalachia Truly Exist?” Journal of Transcultural Nursing 27 (2): 94–102.

- Dickson, M. F., M. Staton-Tindall, K. E. Smith, C. Leukefeld, J. M. Webster, and C. B. Oser. 2017. “A Facebook Follow-Up Strategy for Rural Drug-Using Women.” The Journal of Rural Health 33 (3): 250–256.

- Ginsburg, F. D., and R. Rapp, eds. 1995. Conceiving the New World Order: The Global Politics of Reproduction. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Griffin, M., R. J. Martino, C. LoSchiavo, C. Comer-Carruthers, K. D. Krause, C. B. Stults, and P. N. Halkitis. 2022. “Ensuring Survey Research Data Integrity in the Era of Internet Bots.” Quality & Quantity 56 (4): 2841–2852.

- Guttmacher Institute. 2022. “Interactive Map: US Abortion Policies and Access after Roe.” August 3, 2022. https://states.guttmacher.org/policies/

- Hardee, K., J. Kumar, K. Newman, L. Bakamjian, S. Harris, M. Rodríguez, and W. Brown. 2014. “Voluntary, Human Rights-Based Family Planning: A Conceptual Framework.” Studies in Family Planning 45 (1): 1–18.

- Harris, S., L. Reichenbach, and K. Hardee. 2016. “Measuring and Monitoring Quality of Care in Family Planning: Are We Ignoring Negative Experiences?” Open Access Journal of Contraception 7: 97–108.

- Hatzenbuehler, M. L., J. C. Phelan, and B. G. Link. 2013. “Stigma as a Fundamental Cause of Population Health Inequalities.” American Journal of Public Health 103 (5): 813–821.

- Holmes, S. M., H. Hansen, A. Jenks, S. D. Stonington, M. Morse, J. A. Greene, K. A. Wailoo, M. G. Marmot, and P. E. Farmer. 2020. “Misdiagnosis, Mistreatment, and Harm – When Medical Care Ignores Social Forces.” The New England Journal of Medicine 382 (12): 1083–1086.

- Holt, K., J. M. Caglia, E. Peca, J. M. Sherry, and A. Langer. 2017. “A Call for Collaboration on Respectful, Person-Centered Health Care in Family Planning and Maternal Health.” Reproductive Health 14 (1): 20.

- Hsieh, H.-F., and S. E. Shannon. 2005. “Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis.” Qualitative Health Research 15 (9): 1277–1288.

- Hussein, J., and L. Ferguson. 2019. “Eliminating Stigma and Discrimination in Sexual and Reproductive Health Care: A Public Health Imperative.” Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters 27 (3): 1–5.

- Kimport, K. 2021. No Real Choice: How Culture and Politics Matter for Reproductive Autonomy. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. https://www.rutgersuniversitypress.org/no-real-choice/9781978817913/

- Knight, K. R., L. G. Duncan, M. Szilvasi, A. Premkumar, M. Matache, and A. Jackson. 2019. “Reproductive (In)Justice – Two Patients with Avoidable Poor Reproductive Outcomes.” The New England Journal of Medicine 381 (7): 593–596.

- Mann, E. S. 2022. “The Power of Persuasion: Normative Accountability and Clinicians’ Practices of Contraceptive Counseling.” SSM – Qualitative Research in Health 2: 100049. doi:10.1016/j.ssmqr.2022.100049

- Marshall, J. L., L. Thomas, N. M. Lane, G. M. Holmes, T. A. Arcury, R. Randolph, P. Silberman, et al. 2017. “Health Disparities in Appalachia.” https://www.arc.gov/wpcontent/uploads/2020/06/Health_Disparities_in_Appalachia_August_2017.pdf

- Meit, M., M. Heffernan, and E. Tanenbaum. 2019. “Investigating the Impact of the Diseases of Despair in Appalachia.” Journal of Appalachian Health 1 (2): 7–18.

- Morrow, S. L. 2005. “Quality and Trustworthiness in Qualitative Research in Counseling Psychology.” Journal of Counseling Psychology 52 (2): 250–260.

- Murray, B., and S. McCrone. 2015. “An Integrative Review of Promoting Trust in the Patient-Primary Care Provider Relationship.” Journal of Advanced Nursing 71 (1): 3–23.

- O’Donnell, J., A. Goldberg, E. Lieberman, and T. Betancourt. 2018. “‘I Wouldn’t Even Know Where to Start’: Unwanted Pregnancy and Abortion Decision-Making in Central Appalachia.” Reproductive Health Matters 26 (54): 98–113.

- Odero, A., M. Pongy, L. Chauvel, B. Voz, E. Spitz, B. Pétré, and M. Baumann. 2020. “Core Values That Influence the Patient-Healthcare Professional Power Dynamic: Steering Interaction towards Partnership.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17 (22): 8458.

- Paltrow, L. M., L. H. Harris, and M. F. Marshall. 2022. “Beyond Abortion: The Consequences of Overturning Roe.” The American Journal of Bioethics 22 (8): 3–15.

- Pollard, K., and L. A. Jacobsen. 2021. “The Appalachian Region: A Data Overview from the 2015-2019 American Community Survey.” Appalachian Regional Commission. https://www.arc.gov/report/the-appalachian-region-a-data-overview-from-the-2015-2019-american-community-survey/

- Ross, L. J., and R. Solinger. 2017. Reproductive Justice: An Introduction. Reproductive Justice: A New Vision for the Twenty-First Century. Oakland, CA: University of California Press.

- Seelman, K. L., A. Vasi, S. K. Kattari, and L. R. Alvarez-Hernandez. 2021. “Predictors of Healthcare Mistreatment among Transgender and Gender Diverse Individuals: Are There Different Patterns by Patient Race and Ethnicity?” Social Work in Health Care 60 (5): 411–429.

- Siddiqui, S. M. 2022. “Mistreatment in Medical Care and Psychological Distress among Asian Americans.” Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 24 (4): 963–969.

- Stangl, A. L., V. A. Earnshaw, C. H. Logie, W. v. Brakel, L. C. Simbayi, I. Barré, and J. F. Dovidio. 2019. “The Health Stigma and Discrimination Framework: A Global, Crosscutting Framework to Inform Research, Intervention Development, and Policy on Health-Related Stigmas.” BMC Medicine 17 (1): 31.

- Staton, M., M. F. Dickson, E. Pike, H. Surratt, and S. Young. 2022. “An Exploratory Examination of Social Media Use and Risky Sexual Practices: A Profile of Women in Rural Appalachia Who Use Drugs.” AIDS & Behavior 26 (8): 2548–2558.

- Swan, L. E. T., S. L. Auerbach, G. E. Ely, K. Agbemenu, J. Mencia, and N. R. Araf. 2020. “Family Planning Practices in Appalachia: Focus Group Perspectives on Service Needs in the Context of Regional Substance Abuse.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17 (4): 1198.

- Teitcher, J. E. F., W. O. Bockting, J. A. Bauermeister, C. J. Hoefer, M. H. Miner, and R. L. Klitzman. 2015. “Detecting, Preventing, and Responding to ‘Fraudsters’ in Internet Research: Ethics and Tradeoffs.” Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics 43 (1): 116–133.

- Valentine, J. A., L. F. Delgado, L. T. Haderxhanaj, and M. Hogben. 2021. “Improving Sexual Health in U.S. Rural Communities: Reducing the Impact of Stigma.” AIDS & Behavior 26: 90–99.

- Whitaker, C., S. Stevelink, and N. Fear. 2017. “The Use of Facebook in Recruiting Participants for Health Research Purposes: A Systematic Review.” Journal of Medical Internet Research 19 (8): e290.