Abstract

This literature review synthesises existing evidence and offers a thematic analysis of primary care and emergency department experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer and/or any other sexual or gender minority (LGBTQ+) individuals in Canada. Articles detailing first-person primary or emergency care experiences of LGBTQ + patients were included from EMBASE, MEDLINE, PsycINFO and CINHAL. Studies published before 2011, focused on the COVID-19 pandemic, unavailable in English, non-Canadian, specific to other healthcare settings, and/or only discussing healthcare provider experiences were excluded. Critical appraisal was performed following title/abstract screening and full-text review by three reviewers. Of sixteen articles, half were classified as general LGBTQ + experiences and half as trans-specific experiences. Three overarching themes were identified: discomfort/disclosure concerns, lack of positive space signalling, and lack of healthcare provider knowledge. Heteronormative assumptions were a key theme among general LGBTQ + experiences. Trans-specific themes included barriers to accessing care, the need for self-advocacy, care avoidance, and disrespectful communication. Only one study reported positive interactions. LGBTQ + patients continue to have negative experiences within Canadian primary and emergency care – at the provider level and due to system constraints. Increasing culturally competent care, healthcare provider knowledge, positive space signals, and decreasing barriers to care can improve LGBTQ + experiences.

Introduction

It has been estimated that 4% of the Canadian population identifies as lesbian, gay, or bisexual and 0.24% identifies as transgender (Statistics Canada Citation2021; Cotter and Savage Citation2019). These statistics are likely an underestimate as people are more likely to report having same-sex attraction and/or engaging in same-sex sexual behaviour than to identify explicitly as lesbian, gay or bisexual (Gates Citation2011). A February 2021 Gallup News article explains that the known prevalence of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer and/or any other sexual or gender minority (LGBTQ+) individuals is also increasing as people feel more comfortable disclosing their sexual orientation and/or gender identity. This pattern is likely to continue as younger generations are more likely than older ones to identify as LGBT.

Historically, the LGBTQ + community has been discriminated against in many ways: socially, criminally, medically, physically and culturally (Daum Citation2019; McKay, Lindquist, and Misra Citation2019; Silverstein Citation2009). Although openly identifying as LGBTQ + in Canada has become more accepted in recent years, discrimination and stigma persist (Statistics Canada Citation2021; Cotter and Savage Citation2019; McKay, Lindquist, and Misra Citation2019; Taylor and Peter Citation2011). A nation-wide Canadian report on harassment in school found that 74% of transgender students had been verbally harassed about their gender expression and 21% of LGBTQ + students had been physically harassed or assaulted because of their sexual orientation (Taylor and Peter Citation2011). There are also increased levels of sexual assault and violence against LGBTQ + individuals (McKay, Lindquist, and Misra Citation2019; Kassing et al. Citation2021; Casey et al. Citation2019). Several systematic reviews have shown that LGBT individuals are at greater risk for depression, suicidality and other mental health concerns (Plöderl and Tremblay Citation2015; Miranda-Mendizábal et al. Citation2017; Lick, Durso, and Johnson Citation2013) than others. Discrimination against and harm towards sexual and gender minorities persists today, in Canada and around the world (Swiebel and van der Veur Citation2009).

The healthcare system has historically stigmatised and perpetuated harm towards LGBTQ + persons. Despite recent efforts to increase cultural awareness and acceptance within the system, people who identify as LGBTQ + are still subject to harmful practices and policies (Subhrajit Citation2014). Homosexuality was considered a personality disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders until 1973 and many health care providers continued to view homosexuality as a disorder into the 1990s (Silverstein Citation2009; Jones and Gabriel Citation1999). Sexual orientation change efforts and/or conversion therapy, the practice of attempting to change someone’s gender or sexual orientation often by coercion, has been used by some religious leaders and mental health providers (Ryan et al. Citation2020). Sexual orientation change efforts have been linked to increased depression, increased suicide attempts, lower income, and lower educational attainment in youth as well as depression, anxiety, general distress and suicide in LGBTQ + adults (Ryan et al. Citation2020; Andrade and Redondo Citation2022). Only since December 2021 has the Canadian government banned conversion therapy and sexual orientation change efforts, as noted in a Toronto Star article on December 6, 2021. Although there has been an increase in training for health care providers on LGBTQ + identities, studies have not shown if this is sufficient to enact long-term change (Röndahl Citation2011; Sekoni et al. Citation2017)

People who identify as LGBTQ + have unique healthcare needs, such as: different sexually transmitted infection (STI) risks; increased risk for mental health concerns; gender affirming care; and requiring a more nuanced discussion around screening services, in addition to routine care needs (McNamara and Ng Citation2016). This, along with historical and current discrimination, makes it critical to understand healthcare experiences to make receiving healthcare safer for LGBTQ + patients. This review’s objective was to synthesise the existing evidence on the primary care and emergency department care experiences among LGBTQ + individuals to better understand factors contributing to positive and negative experiences.

Methods

Terminology

This literature review was intended to include the experiences of all sexual and gender minority individuals. With evolving terminology there is no single descriptor or acronym that can accurately envelop all gender and sexuality minority identities. The “+” symbolises all sexual and gender minority identities that are not included in the acronym. This is not meant to minimise the experiences of those who identify as a sexual or gender minority other than lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and/or queer (LGBTQ), but rather to be more inclusive. Importantly, we made every effort to not generalise the experiences of all sexual and gender minority-identifying people as one common experience. Results are reported according to the specific participants of each study (hence the reason for varying terminology throughout this paper).

Search strategy

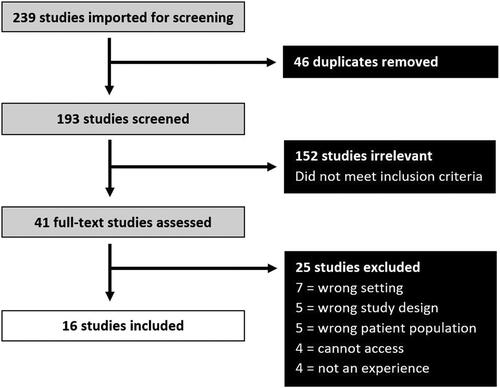

In July 2021 the EMBASE, MEDLINE, PsycINFO and CINHAL databases were searched using a variety of keywords such as “primary care”, “emergency department”, “hospital”, “experience”, “perception”, “LGBT” (exploded), and “gender and sexual minorities”. The reference lists from key articles were manually examined for additional relevant articles identified in the initial search. The database search was re-run in May 2022 to ensure no new articles that met inclusion criteria were missed. A PRISMA diagram was used to outline the results of the search (). Ethics review was not required since the study is a synthesis of the evidence based on published and non-identifiable data. No individual participant data is included in this literature review.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

We included primary research articles published between January 2011 and July 2021 that presented original findings from Canadian studies with patients who identified as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer or any other sexuality or gender minority. Experiences and perceptions of LGBTQ + patients who used primary or emergency care for any reason were included. Articles were excluded if they were published before 2011, focused on the COVID-19 pandemic, were not available in English, conducted outside of Canada, conducted in healthcare settings outside of primary care or emergency departments (for example, mental health care, HIV clinics, reproductive health services), and/or documented the experiences/perceptions of health care providers.

Screening and assessment of methodological quality

Title and abstract screening was divided evenly amongst three independent reviewers (JC, AN, SC) and screened according to inclusion and exclusion criteria specified above. Full-text screening of all articles that met inclusion criteria was conducted in duplicate (SC and JC) with conflicts resolved by an independent third reviewer (AN).

Data abstraction

Study characteristics were extracted from included papers (). Subsequently, studies were assessed for methodological rigour (), and a thematic analysis was conducted. The critical appraisal was completed using a modified CASP protocol designed for qualitative research to assess risk of bias (Brice Citation2022). Thematic analysis included reviewing all papers using an inductive approach and identifying preliminary codes in an iterative fashion, then grouping similar codes into broader themes. Once themes had been identified, previous papers were re-analysed in a deductive manner. The description for each theme was borne out of common examples across multiple studies.

Table 1. Characteristics of included studies.

Table 2. Quality assessment of included articles.

Results

Study inclusion

The results of the search strategy are shown in . The search yielded 239 studies in total (46 duplicates) and therefore 193 unique studies were screened. Of the 41 articles that underwent full-text review, a total of 16 articles were included in this synthesis (see ). Multiple studies (Baker and Beagan Citation2014; Fredericks, Harbin, and Baker Citation2017; Harbin, Beagan, and Goldberg Citation2012; Heyes, Dean, and Goldberg Citation2016; Heyes and Thachuk Citation2015) used the same dataset and care was taken to ensure the number of participants included in each theme was accurate and not duplicated.

Study characteristics and quality assessment

An overview of study characteristics () shows that studies tended to be qualitative or mixed-methods in nature, with all using semi-structured interviews or Internet surveys to collect data. The sample sizes tended to be small (<50), with only seven large-scale studies in Nova Scotia, Ontario or Canada-wide. Eight of 16 studies were specific to the transgender community and five studies used data from the same dataset, but each shared unique insights. Most articles categorised as general LGBTQ + experiences focused on queer, lesbian and bisexual women, one article focused on gay and bisexual men, and two articles included the LGBTQ + community more broadly. Articles categorised as trans-specific focused solely on transfeminine, transmasculine, and non-binary individuals.

The quality assessment () demonstrated that eight articles had a small sample size (<20), one had a medium sample size (20-100), and seven had a large sample size (>100). Nine of 16 articles explored deviant cases/exceptions, whereas only three articles commented on reflexivity among the researchers. Two articles failed to expand on their process of data analysis and as such it was difficult to assess rigour of analysis. Limitations inherent to qualitative studies, such as small sample sizes, interviewer bias and lack of generalisability were reflected in the quality assessment; however, no studies were excluded based on poor quality due to the limited sample.

Thematic analysis

Although some overlap existed, there was a clear distinction between general LGBTQ + care experiences and the healthcare experiences of transgender patients. To better understand the similarities and differences in their experiences, the articles were divided into general LGBTQ + experiences and trans-specific experiences (). Although transgender participants were sometimes included in a few articles deemed general LGBTQ+, broad themes were extracted in their analyses, and as such it was impossible to discern trans-specific perspectives.

Themes identified in both the general LGBTQ + and trans-specific groups included discomfort/disclosure concerns, a lack of positive space signalling, and a lack of health care provider knowledge (). The primary theme among general LGBTQ + experiences concerned heteronormative assumptions, whereas trans-specific themes centred on barriers to accessing care, the need for self-advocacy, the avoidance of care, and disrespectful communication (). Only one study reported positive experiences with over 66.2% of LGB participants and 68.7% of trans participants stating they had positive experiences using primary care services in Nova Scotia (Gahagan and Subirana-Malaret Citation2018).

Table 3. Similarities in themes between LGBTQ + and trans-specific primary care and emergency department experiences.

Lack of positive space signalling Trans-specific Lack of health care provider knowledge Trans-specific

Table 4. Unique themes between LGBTQ + and trans-specific primary care and emergency department experiences.

Barriers to accessing care Self-advocacy Avoidance of care Disrespectful communication

Transgender patients felt greater discomfort in the emergency department as their transgender status would likely be disclosed to an unknown provider in a position of (). In contrast, queer, lesbian, gay and bisexual patients felt more discomfort with primary care visits as they needed to decide if or when they wanted to disclose their sexuality to the provider, which may have potentially damaged their long-term relationship. Often, these patients did not feel it was necessary to disclose their sexual orientation to providers in the emergency department. Although both LGBTQ + and trans participants experienced discomfort and concerns about disclosure to their primary and emergency care providers, general LGBTQ + participants were more likely to be concerned about disclosing their sexuality to their health care provider. LGBTQ + patients were more likely to feel invisible, that the onus on discussing sexuality fell to them as patients, and additionally had concerns about the care providers’ response. In contrast, transgender patients expressed discomfort discussing trans-health related issues with their providers, but no articles mentioned primary care disclosure concerns. Both groups spoke about the lack of positive space signalling, and how they believed even small gestures would make healthcare environments more inclusive and decrease discomfort.

The two most common themes pertaining to trans-specific experiences were barriers to accessing care and avoidance of care (). Trans patients were more likely to avoid emergency department visits due to concerns about receiving inappropriate care and transphobia – such as deadnaming (using someone’s birth name instead of their chosen name), misgendering (using the wrong pronouns/gender for someone, regardless of intent), refusal of care, or disrespectful comments. Long wait times for referrals, having to navigate a complex healthcare system, lacking other support, insufficient healthcare resources/physicians in the region and geographic isolation in the North were all facets of barriers to care. Many transgender patients felt the need to self-advocate, which placed an additional and unnecessary burden on them as they struggled to vocalise their healthcare needs. For example, transgender patients were often expected to educate their health care providers, prepare and plan for their appointments to ensure that they would receive appropriate care, and follow-up regularly to ensure that their referrals were passed on.

Discussion

This review unearthed rich information on the primary care and emergency department experiences of Canadian LGBTQ + patients. Although many studies explicitly inquired about both positive and negative experiences, only one article included positive experiences (Gahagan and Subirana-Malaret Citation2018). Many themes arose from both general LGBTQ + articles and trans-specific ones.

In general, the trans-specific articles focused more on gender affirming hormone care whereas the concerns of general LGBTQ + patients included safe sexual practices, STI testing, and conception. LGTBQ + patients were not confident that their providers could accurately assess the risk level of their sexual practices or provide knowledge on safer sexual practices or screening. Transgender patients were concerned about their family practitioners’ familiarity with and willingness to prescribe gender-affirming hormone therapy.

Incorporating LGBTQ + culturally competent care may minimise disclosure/discomfort concerns, heteronormative assumptions, disrespectful communication, the need for self-advocacy, and care avoidance. An increase in health provider training can increase health care provider knowledge, decrease care avoidance, decrease the need for self-advocacy, and decrease discomfort. Barriers to care may be improved with systems-level changes and positive space signalling may decrease discomfort and disclosure concerns as well.

LGBTQ + culturally competent care

The negative experiences of disclosure/discomfort, disrespectful communication, heteronormativity, increased self-advocacy, and care avoidance may be influenced by the amount of culturally competent care provided in primary and emergency care. Cultural competence has been defined as “a set of congruent behaviours, attitudes, and policies that come together in a system, agency, or among professionals and enable that system, agency, or those professionals to work effectively in cross-cultural situations” (Cross et al. Citation1989, 13). Culturally competent care leads to higher rates of patient satisfaction and improved health, but an LGBTQ + specific cultural competency programme has not explicitly been evaluated for efficacy (Savage Citation2007).

Various attempts have been made to increase cultural competency surrounding LGBTQ + care, in Canada and elsewhere. In 2007, United States Veteran’s Affairs developed a pilot program in Boston to increase health care provider competency and create policies that would ensure appropriate treatment of transgender patients and legal protection for providers (Ruben et al. Citation2017). This local intervention was so successful at providing quality LGBT healthcare that it has been expanded across the USA (Mattocks et al. Citation2014). This demonstrates the effectiveness of utilising culturally competent frameworks and teachings for LGBT healthcare delivery.

Increasing health care provider knowledge

This review of the literature revealed that insufficient health care provider knowledge negatively impacts LGBTQ + patient care experiences – and is especially prevalent for transgender patients. There is an onus on patients to self-advocate and educate their providers, and a common occurrence of care avoidance among LGBTQ + individuals, which may be mitigated with increased health care provider training. There are transgender-specific healthcare resources for both primary and specialist care. The World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) provides the highest standard of care and practice guidelines for the healthcare of transgender patients around the world and provides training and certifications for providers (Coleman et al. Citation2022). An Ontario resource for transgender health is Rainbow Health Ontario, which provides condensed, evidence-based information for any physicians prescribing gender-affirming hormone therapy (Bourns Citation2019). Implementing widespread use of evidence-based practices can empower family medicine practitioners to prescribe gender-affirming hormone therapy, which could reduce burdens on the system and decrease barriers to access for transgender patients. Early incorporation of these practices in health professional training would facilitate familiarity and ease of use in practice.

Reducing barriers to care

Insufficient access to gender-affirming care poses a unique concern to transgender patients. Those seeking gender-affirming care often need to navigate barriers to care such as long waiting times and administrative burdens, on top of an increased risk of psychological distress and suicide (Green et al. Citation2022; Spanos et al. Citation2021). Facilitating timely access to lifesaving gender-affirming hormone therapy at the level of primary care is a channel by which barriers to care for transgender patients can be reduced (Green et al. Citation2022; Spanos et al. Citation2021).

The recently released 8th edition of the WPATH Standard of Care guidelines transitioned to an informed consent model of medical and surgical gender affirming care, rather than requiring certain assessments, such as psychiatric or specialist evaluations (Coleman et al. Citation2022, S31). In Canada, healthcare is under provincial domain, which leads to each province having different gender affirming care coverages, as noted in Danielle D’Entremont’s CBC article on March 18, 2021. This article also states that Yukon has the most comprehensive coverage for gender affirming care in Canada. As noted in an Ontario Government Newsroom article on November 6, 2015, provincial insurance requires physicians to follow the WPATH guidelines to get coverage for their patients– but not all WPATH recommendations are covered (such as facial feminisation surgery).

Positive space signalling

Both general LGBTQ + and trans-specific experiences indicated a desire for symbols or materials indicating LGBTQ+-friendly environments, commonly referred to as positive space signals. A lack of positive space signals can lead to discomfort, fear of disclosure, and uncertainty about whether a provider or healthcare environment can be trusted to be LGBTQ+-friendly. A brief US review demonstrated a lack of empirical data on the effectiveness of positive space signals, but concluded that there is likely a low risk of harm in employing them (Chaney and Sanchez Citation2018). Another US and Canada-based study on Pride semiotics supported those findings, concluding that small pride/rainbow signs or stickers made individuals feel more comfortable and safer in healthcare spaces (Wolowic et al. Citation2017). The authors also noted that there is a limitation to what signalling can provide – symbols must be vetted before they are trusted and LGBTQ + patients should still proceed with caution (Wolowic et al. Citation2017). Additionally, safety cues can transfer over to other marginalised populations (Chaney, Sanchez, and Remedios Citation2016). For example, providing gender-neutral toilets and bathrooms may also make LGB and racialised patients feel the space is inclusive for them (Chaney and Sanchez Citation2018). When a healthcare team has incorporated culturally competent practices and is confident in their ability to provide LGBTQ + positive care, they can demonstrate this by using pronoun pins, displaying pride signifiers, having posters or pamphlets on queer health, or having preferred name and/or pronoun sections on intake forms.

Strengths and limitations of the review

This review identified rich qualitative data surrounding LGBTQ + primary and emergency care experiences in Canada in the last decade. The detailed first-person accounts in the studies cited were used to generate both broad and specific recommendations for improving primary and emergency care. While the data collected chronicled detailed lived experiences, the studies included in this review have notable limitations. First, findings from them may not be widely generalisable due to the predominantly qualitative nature of the data and small sample sizes. Data collection via surveys and interviews are also susceptible to bias, particularly social desirability bias and interviewer bias.

Furthermore, five of 16 articles utilised the same dataset (Baker and Beagan Citation2014; Fredericks, Harbin, and Baker Citation2017; Harbin, Beagan, and Goldberg Citation2012; Heyes, Dean, and Goldberg Citation2016; Heyes and Thachuk Citation2015) and three articles used the same Trans PULSE study dataset (Bauer et al. Citation2014; Bauer et al. Citation2015; Giblon and Bauer Citation2017). There was also no comparison of LGBTQ + primary and emergency care experiences to non-LGBTQ + experiences. Only one article (Gahagan and Subirana-Malaret Citation2018) contained the option to identify as Two-spirit, but this information was provided only in the results, and not incorporated into the discussion.

In addition, most studies focused on LGBT health while using an ‘other’ category to describe gender and sexuality minorities identifying beyond LGBT (e.g. intersex, Two-spirit, pansexual, asexual, etc.) which decreases specificity. Additionally, the review did not identify many positive interactions with primary and emergency care providers, although some reviews did ask about both positive and negative experiences.

Finally, the review examined published primary data from science-based search engines and therefore the grey literature was not examined.

Future directions

In future work it would be prudent to collect information on positive healthcare experiences so facilitators at the level of the health care provider, as well as in the clinical environment, can be identified. A study comparing the primary and emergency care experiences of LGBTQ + and non-LGBTQ + patients would be helpful in further delineating both positive and negative care experiences among LGBTQ + patients in Canada. Gathering information on healthcare providers’ perspectives of treating LGBTQ + patients would also shed light on LGBTQ + care. Future studies are needed that explicitly include Two-spirit voices to add inclusion to the work already undertaken. A quality improvement analysis of how existing LGBTQ + cultural competency training impacts patients and healthcare delivery is crucial to improving care. For example, the US National LGBT Cancer Network recently published a best practices guideline for creating and delivering LGBTQ Cultural Competency Training (Margolies, Joo, and McDavid Citation2014) and in 2021 the Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario (Citation2021) published best practice guidelines for promoting 2SLGBTQI + health equity. Quality improvement analysis of best practices such as above and others is an important next step.

Conclusion

This review summarises the wide range of experiences that LGBTQ + patients encounter during primary care and emergency department visits in Canada. Key themes included health providers’ lack of knowledge of LGBTQ + individuals, a lack of positive space signalling, as well as discomfort and disclosure concerns for both general LGBTQ + and trans-specific experiences. Heteronormativity was more of a concern for general LGBTQ + respondents whereas disrespectful communication, an increased need for self-advocacy, avoidance of care, and barriers to accessing care were experienced more specifically by transgender study participants. An increase in health care provider knowledge and culturally competent care, more safe space signalling, and systemic changes to reduce barriers to accessing care, such as primary care physicians prescribing gender-affirming hormone therapy, are likely to improve the healthcare experiences of the LGBTQ + community and should be implemented more widely.

Acknowledgements

We thank Sandra Halliday, a health sciences librarian at Queen’s University, for her guidance in the development of the literature search strategy and identification of key terms.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Funding

No specific funding was received for this review.

References

- Andrade, G., and M. C. Redondo. 2022. “Is Conversion Therapy Ethical? A Renewed Discussion in The Context of Legal Efforts To Ban It.” Ethics, Medicine and Public Health 20: 100732.

- Baker, K., and B. Beagan. 2014. “Making Assumptions, Making Space: An Anthropological Critique of Cultural Competency and Its Relevance to Queer Patients.” Medical Anthropology Quarterly 28 (4): 578–598.

- Bauer, G. R., A. I. Scheim, M. B. Deutsch, and C. Massarella. 2014. “Reported Emergency Department Avoidance, Use, and Experiences of Transgender Persons in Ontario, Canada: Results from a Respondent-Driven Sampling Survey.” Annals of Emergency Medicine 63 (6): 713–720.e1.

- Bauer, G. R., X. Zong, A. I. Scheim, R. Hammond, and A. Thind. 2015. “Factors Impacting Transgender Patients’ Discomfort with Their Family Physicians: A Respondent-Driven Sampling Survey.” PloS One 10 (12): e0145046.

- Bell, J., and E. Purkey. 2019. “Trans Individuals’ Experiences in Primary Care.” Canadian Family Physician Medecin de Famille Canadien 65 (4): e147–e154.

- Bourns, A. 2019. “4th Edition: Sherbourne’s Guidelines for Gender-affirming Primary Care with Trans and Non-binary patients.”

- Brice, R. 2022. "CASP CHECKLISTS - CASP - Critical Appraisal Skills Programme". CASP - Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/.

- Casey, L. S., S. L. Reisner, M. G. Findling, R. J. Blendon, J. M. Benson, J. M. Sayde, and C. Miller. 2019. “Discrimination in The United States: Experiences of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, And Queer Americans.” Health Services Research 54 (S2): 1454–1466.

- Chaney, K. E., and D. T. Sanchez. 2018. “Gender-Inclusive Bathrooms Signal Fairness Across Identity Dimensions.” Social Psychological and Personality Science 9 (2): 245–253.

- Chaney, K. E., D. T. Sanchez, and J. D. Remedios. 2016. “Organizational Identity Safety Cue Transfers.” Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin 42 (11): 1564–1576.

- Clark, B. A., S. K. Marshall, and E. M. Saewyc. 2020. “Hormone Therapy Decision‐Making Processes: Transgender Youth and Parents.” Journal of Adolescence 79 (1): 136–147.

- Clark, B. A., J. F. Veale, D. Greyson, and E. Saewyc. 2018a. “Primary Care Access and Foregone Care: A Survey of Transgender Adolescents and Young Adults.” Family Practice 35 (3): 302–306.

- Clark, B. A., J. F. Veale, M. Townsend, H. Frohard-Dourlent, and E. Saewyc. 2018b. “Non-Binary Youth: Access to Gender-Affirming Primary Health Care.” International Journal of Transgenderism 19 (2): 158–169.

- Coleman, T. A., G. R. Bauer, D. Pugh, G. Aykroyd, L. Powell, and R. Newman. 2017. “Sexual Orientation Disclosure in Primary Care Settings by Gay, Bisexual, and Other Men Who Have Sex with Men in a Canadian City.” LGBT Health 4 (1): 42–54.

- Coleman, E., A. E. Radix, W. P. Bouman, G. R. Brown, A. L. C. de Vries, M. B. Deutsch, R. Ettner, L. Fraser, M. Goodman, J. Green, et al. 2022. “Standards of Care for the Health of Transgender and Gender Diverse People, Version 8.” International Journal of Transgender Health 23 (sup1): S1–S259.

- Cotter, A., and L. Savage. 2019. "Gender-Based Violence and Unwanted Sexual Behaviour in Canada, 2018: Initial Findings From The Survey Of Safety In Public And Private Spaces". https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/85-002-x/2019001/article/00017-eng.htm

- Cross, T., B. Bazron, K. Dennis, and M. Isaacs. 1989. Towards A Culturally Competent System of Care: A Monograph on Effective Services for Minority Children Who Are Severely Emotionally Disturbed. Washington, DC: Child and Adolescent Service System Program (CASSP) Technical Assistance Center, Georgetown University Child Development Center.

- Daum, C. W. 2019. “Violence Against and Policing of LGBTQ Communities: A Historical Perspective.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.1221

- Fredericks, E., A. Harbin, and K. Baker. 2017. “Being (In)Visible in the Clinic: A Qualitative Study of Queer, Lesbian, and Bisexual Women’s Health Care Experiences in Eastern Canada.” Health Care for Women International 38 (4): 394–408.

- Gahagan, J., and M. Subirana-Malaret. 2018. “Improving Pathways to Primary Health Care Among LGBTQ Populations and Health Care Providers: Key Findings from Nova Scotia, Canada.” International Journal for Equity in Health 17 (1): 76.

- Gates, G. 2011. How Many People are Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender? Los Angeles, CA: The Williams Institute/UCLA School of Law.

- Giblon, R., and G. R. Bauer. 2017. “Health Care Availability, Quality, And Unmet Need: A Comparison of Transgender and Cisgender Residents Of Ontario, Canada.” BMC Health Services Research 17 (1): 283.

- Green, A. E., J. P. DeChants, M. N. Price, and C. K. Davis. 2022. “Association of Gender-Affirming Hormone Therapy with Depression, Thoughts of Suicide, and Attempted Suicide Among Transgender and Nonbinary Youth.” The Journal of Adolescent Health 70 (4): 643–649.

- Harbin, A., B. Beagan, and L. Goldberg. 2012. “Discomfort, Judgment, and Health Care for Queers.” Journal of Bioethical Inquiry 9 (2): 149–160.

- Heyes, C., M. Dean, and L. Goldberg. 2016. “Queer Phenomenology, Sexual Orientation, and Health Care Spaces: Learning from the Narratives of Queer Women and Nurses in Primary Health Care.” Journal of Homosexuality 63 (2): 141–155.

- Heyes, C., and A. Thachuk. 2015. “Queering Know-How: Clinical Skill Acquisition as Ethical Practice.” Journal of Bioethical Inquiry 12 (2): 331–341.

- Jones, M. A., and M. A. Gabriel. 1999. “Utilization of Psychotherapy by Lesbians, Gay Men, and Bisexuals: Findings from a Nationwide Survey.” The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 69 (2): 209–219.

- Kassing, F., T. Casanova, J. A. Griffin, E. Wood, and L. M. Stepleman. 2021. “The Effects of Polyvictimization on Mental and Physical Health Outcomes in an LGBTQ Sample.” Journal of Traumatic Stress 34 (1): 161–171.

- Lick, D. J., L. E. Durso, and K. L. Johnson. 2013. “Minority Stress and Physical Health Among Sexual Minorities.” Perspectives on Psychological Science 8 (5): 521–548.

- Logie, C. H., C. L. Lys, L. Dias, N. Schott, M. R. Zouboules, N. MacNeill, and K. Mackay. 2019. “Automatic Assumption of Your Gender, Sexuality and Sexual Practices is also Discrimination": Exploring Sexual Healthcare Experiences and Recommendations Among Sexually and Gender Diverse Persons in Arctic Canada.” Health & Social Care in the Community 27 (5): 1204–1213.

- Margolies, L., R. Joo, and J. McDavid. 2014. Best Practices in Creating and Delivering LGBTQ Cultural Competency Trainings for Health and Social Service Agencies. National LGBT Cancer Network.

- Mattocks, K. M., M. R. Kauth, T. Sandfort, A. R. Matza, J. Cherry Sullivan, and J. C. Shipherd. 2014. “Understanding Health-Care Needs of Sexual and Gender Minority Veterans: How Targeted Research and Policy can Improve Health.” LGBT Health 1 (1): 50–57.

- McKay, T., C. H. Lindquist, and S. Misra. 2019. “Understanding (and Acting on) 20 Years of Research on Violence and LGBTQ + Communities.” Trauma, Violence & Abuse 20 (5): 665–678.

- McNamara, M. C., and H. Ng. 2016. “Best Practices in LGBT Care: A Guide for Primary Care Physicians.” Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine 83 (7): 531–541.

- Miranda-Mendizábal, A., P. Castellví, O. Parés-Badell, J. Almenara, I. Alonso, M. J. Blasco, A. Cebrià, A. Gabilondo, M. Gili, C. Lagares, et al. 2017. “Sexual Orientation and Suicidal Behaviour in Adolescents and Young Adults: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science 211 (2): 77–87.

- Plöderl, M., and P. Tremblay. 2015. “Mental Health of Sexual Minorities. A Systematic Review.” International Review of Psychiatry 27 (5): 367–385.

- Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario. 2021. “Promoting 2SLGBTQI + Health Equity: Best Practice Guideline”.

- Röndahl, G. 2011. “Heteronormativity in Health Care Education Programs.” Nurse Education Today 31 (4): 345–349.

- Ruben, M. A., J. C. Shipherd, D. Topor, C. G. Ahn Allen, C. A. Sloan, H. M. Walton, A. R. Matza, and G. R. Trezza. 2017. “Advancing LGBT Health Care Policies and Clinical Care Within a Large Academic Health Care System: A Case Study.” Journal of Homosexuality 64 (10): 1411–1431.

- Ryan, C., B. T. Russell, R. M. Diaz, and S. T. Russell. 2020. “Parent-Initiated Sexual Orientation Change Efforts with LGBT Adolescents: Implications for Young Adult Mental Health and Adjustment.” Journal of Homosexuality 67 (2): 159–173.

- Savage, S. 2007. “Effective Communication and Delivery of Culturally Competent Health Care.”

- Sekoni, A. O., N. K. Gale, B. Manga-Atangana, A. Bhadhuri, and K. Jolly. 2017. “The Effects of Educational Curricula and Training on LGBT-Specific Health Issues for Healthcare Students and Professionals: A Mixed-Method Systematic Review.” Journal of the International AIDS Society 20 (1): 21624.

- Silverstein, C. 2009. “The Implications of Removing Homosexuality from the DSM as a Mental Disorder.” Archives of Sexual Behavior 38 (2): 161–163.

- Spanos, C., J. A. Grace, S. Y. Leemaqz, A. Brownhill, P. Cundill, P. Locke, P. Wong, J. D. Zajac, and A. S. Cheung. 2021. “The Informed Consent Model of Care for Accessing Gender-Affirming Hormone Therapy is Associated with High Patient Satisfaction.” The Journal of Sexual Medicine 18 (1): 201–208.

- Statistics Canada. 2021. “A Statistical Portrait Of Canada’s Diverse LGBTQ2+ Communities". https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/210615/dq210615a-eng.htm

- Subhrajit, C. 2014. “Problems Faced by LGBT People in the Mainstream Society: Some Recommendations.” International Journal of Interdisciplinary and Multidisciplinary Studies 1 (5): 317–331.

- Swiebel, J., and D. van der Veur. 2009. “Hate Crimes Against Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Persons and the Policy Response of International Governmental Organisations.” Netherlands Quarterly of Human Rights 27 (4): 485–524.

- Taylor, C., and T. Peter. 2011. Every Class in Every School: The First National Climate Survey on Homophobia, Biphobia, and Transphobia in Canadian Schools. Toronto: Egale Canada Human Rights Trust.

- Vermeir, E., L. A. Jackson, and E. G. Marshall. 2018. “Barriers to Primary and Emergency Healthcare for Trans Adults.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 20 (2): 232–246.

- Wolowic, J. M., L. V. Heston, E. M. Saewyc, C. Porta, and M. E. Eisenberg. 2017. “Chasing the Rainbow: Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Queer Youth and Pride Semiotics.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 19 (5): 557–571.