Abstract

Pacific young people living in Aotearoa New Zealand experience disparities in their sexual and reproductive health outcomes, thought to stem from cultural differences and educational inequities. Although these barriers have been characterised in literature, their influence on Pacific youth’s understandings of sexual and reproductive health have been relatively unexplored. This study investigated the sexual and reproductive health knowledge of Pacific students enrolled at a university in Aotearoa New Zealand in 2020 and where they gained this knowledge. The study used the theoretical framework of the (revitalised) Fonofale health model and was guided by the Kakala research methodology. Data were collected by means of an online survey comprised of open-ended questions and Likert scales, completed by eighty-one eligible students. Open-ended questions were analysed for general themes and responses to Likert scale items are reported using descriptive statistical analysis. The study found that Pacific youth have strong foundations of health knowledge that is heavily influenced by Polynesian cultural beliefs. Both formal and non-formal learning environments were important in developing participants’ health knowledge of these topics and for encouraging independent help-seeking behaviours. This is the first reported study to investigate the sexual and reproductive health knowledges of a pan-Pacific tertiary cohort of young people.

Introduction

Sexual and reproductive health are important components of well-being for Pacific peoples in Aotearoa New Zealand (Pulotu-Endemann Citation1995; Veukiso-Ulugia n.d.). Despite this, discussions about sexuality and reproduction are usually restricted by social stigma and cultural tapu (sacredness, prohibitions) within Pacific spaces (Naea Citation2008; Tupuola Citation2004), both in the Pacific Islands and in diasporic Pacific communities such as in Aotearoa New Zealand. The implications of these social restrictions are yet to be fully elucidated, with some suggesting that tapu restricts certain health-related vocabularies and sexual behaviours (Mills Citation2016; Veukiso-Ulugia Citation2016). While some studies have explored Pacific peoples’ perspectives of, and experiences in, sexuality education (Allen Citation2014; Naea Citation2008), little is known about the knowledge Pacific young people have of these tapu topics. To address this gap, we conducted an online survey of Pacific students at a New Zealand university to understand what they know about sexual and reproductive health and where they obtained this knowledge.

Background

Around 8% of the Aotearoa New Zealand population comprises Pacific Islanders (Statistics New Zealand Citation2018), a diverse diasporic community with ties to the subregions of the Pacific Ocean known as Melanesia, Micronesia and Polynesia. In this article, we use the term ‘Pacific Aotearoa’ to contextualise this community’s shared experience as migrants in a bicultural Aotearoa, although this term is not meant to minimise the extraordinary diversity and distinct characteristics of each ethnic group. Throughout the paper, we use ‘sexuality’ as an umbrella term to refer to a spectrum of sexual health topics including sex, sexual orientation and gender, and ‘reproduction’ to refer to reproductive health topics such as contraception, puberty and genitalia. We also refer to the cohort of participants (aged 18–51 years) using the terms ‘young people’ and ‘youth’ interchangeably, as these are both appropriate and familiar phrases to use in the context of Pacific Aotearoa. The term youth also captures the hierarchies inherent in our Pacific communities, for instance, even Pacific people aged 30 years or above may be considered youth if their parents are still alive.

Sexuality and reproduction in Pacific communities

Within Pacific communities, conversations about sexuality and reproduction are often met with discomfort and shame (Nosa et al. Citation2018). Sexuality and reproduction are considered tapu (sacred, forbidden, off-limits) and are rarely spoken of in public, or even private, settings (Veukiso-Ulugia Citation2017). These cultural taboos can influence Pacific peoples’ sexual behaviour. Unmarried Pacific women are often expected to dress modestly and be virgins (Tupuola Citation2004), and Pacific men are often held responsible for upholding their sisters’ virtue (Anae et al. Citation2000). In Pacific households, it is often considered inappropriate for relatives of the opposite sex to sleep in the same room or play games together (Tupuola Citation1998). If this tapu space is breached, it can bring shame (described as mā in some Pacific languages) both to the affected individuals and the wider family (Tupuola Citation2004; Veukiso-Ulugia Citation2016, Citation2017).

These same cultural pressures around sexuality and reproduction are produced and reproduced in diasporic Pacific communities like Pacific Aotearoa. Discussions of sex and relationships are avoided in Pacific households and the conventional gender roles, of women being sexually pure and men being their protectors, persist (Ulugia-Veukiso Citation2010). This may be because the majority (73%) of Pacific Aotearoa identify with a (mostly Christian) religion and regularly attend church on the weekend (MoE Citation2013). Christian churches have historically discouraged open conversation about sexuality and reproduction, fearing it would encourage young people to engage in sex or other behaviours deemed unacceptable (Katavake-McGrath Citation2021).

It should come as no surprise that to avoid breaching the tapu space in their own households, Pacific families prefer secondary schools to educate their children on aspects of sexuality and reproduction (Veukiso-Ulugia Citation2016). Theoretically, this might mean that school-aged Pacific youth receive most of their sexual and reproductive health knowledge from formal school curricula rather than their families. However, national reports suggest Pacific youth are underserved in school sexuality education due to an absence of Pacific-specific content in the curriculum and non-inclusive teaching pedagogies (ERO (Educational Review Office) Citation2018). This calls into question what Pacific youth understand about sexuality and reproduction and where they acquire this knowledge from, if neither their formal sexuality education classes nor at home.

Pacific youth knowledges of sexuality and reproduction

The knowledges surrounding sexuality and reproduction of Pacific young people in tertiary education are poorly defined in the literature. This is partly due to previous studies having a focus on Pacific secondary school students or being specific to a single ethnic group. For Pacific young people in secondary school, the topics of sexuality and reproduction result in feelings of discomfort, stress and embarrassment (Allen Citation2014), especially when talking to their peers (Veukiso-Ulugia Citation2016). This is articulated as a social fear of breaching the vā (space) between themselves and their classmates, especially between classmates of the opposite sex (Anae Citation2010). Vā, as opposed to sexuality and reproduction, is a concept taught to Pacific youth in their households. It is the physical and metaphysical space between two people and can represent the state of their relationship. A good vā can look like maintaining appropriate behaviour and treating the person with respect. Breaking the vā compromises this relational space, often because of inappropriate behaviour – such as discussing tapu topics such as sexuality or reproduction.

There have been several studies focused on the sexual health knowledges and experiences of particular Pacific communities, like Sāmoans. These include studies of Sāmoan women (Naea Citation2008; Tanuvasa Citation1999; Tupuola Citation2004), men (Anae et al. Citation2000) and secondary school students (Ulugia-Veukiso Citation2010; Veukiso-Ulugia Citation2013, Citation2016, Citation2017). These findings collectively suggest that Sāmoans perceive sexual and reproductive health as an important but extremely uncomfortable aspect of their lives. They describe it coming with baggage, with some students believing their cultural membership hinders their experiences in sexuality education (Veukiso-Ulugia n.d.).

These studies above describe three dominant schools of thought. One school emphasises the importance of good quality sexuality education (Fitzpatrick et al. Citation2022; Veukiso-Ulugia Citation2016) and accurate health literacy (Sa’uLilo et al. Citation2018) to ensure safe sexual health behaviours. The other school emphasises that family relationships (Naea Citation2008) and intergenerational knowledge sharing (Matenga-Ikihele Citation2012) will improve Pacific young peoples’ sexual health outcomes. The third school argues that communities and institutions must work collaboratively to effectively educate Pacific youth about sex, relationships, sexuality and reproduction (Fa’avae Citation2016; Ikihele and Nosa Citation2019; Veukiso-Ulugia Citation2017). Although this perspective appears more convincing, no study has yet taken a pan-Pacific approach to investigate youth knowledges about sexuality and reproduction, nor has any study specifically looked at Pacific youth post-secondary school. The current study addresses these gaps by investigating the sexual and reproductive health knowledges of Pacific young people enrolled in tertiary education.

Methods

Theoretical perspective

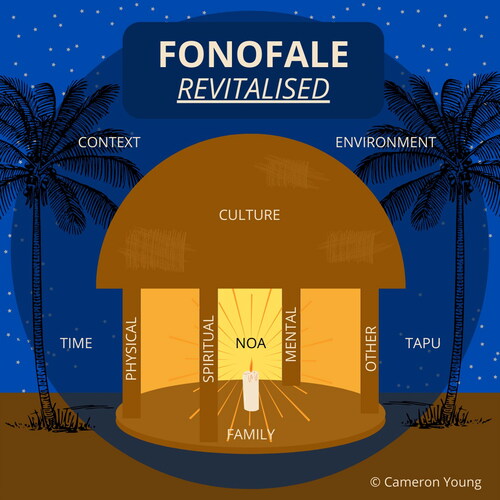

Veukiso-Ulugia (Citation2013) suggests that a Pacific theoretical perspective is necessary when engaging with Pacific people about sensitive health topics. Consequently, this study utilised the Fonofale research paradigm to approach the sensitive topics of sexuality and reproduction. The original Fonofale model (Pulotu-Endemann Citation1995) used the analogy of a traditional Sāmoan fale (meeting house) to describe the complexity of the Pacific concept of well-being. From such a perspective, well-being consists of many elements including physical, mental, social, familial, cultural and spiritual health. An individual aspect of health cannot be isolated from others because they are all interconnected; all aspects of well-being must be considered when engaging with Pacific health research.

The revitalised Fonofale (Young et al. Citation2022) extends this original conception by introducing the cultural values of tapu (sacred, forbidden) and noa (ordinary, normal) into the metaphor as darkness and light, respectively (). In this analogy, tapu represents the hidden or unknown things in our lives, and noa represents safety and comfort. Sexuality and reproduction are tapu and have the potential to raise fear and discomfort in Pacific research participants. This modelFootnote1 repurposes the Fonofale to be a shelter for participants away from harm, actual or perceived, by prompting the researcher to create a safe research environment the participants can enter comfortably. To help achieve this, we committed to using Pacific research methods and methodologies where possible. The multiple components of the Fonofale were also used to broaden the scope of the survey questions.

Figure 1. The revitalised Fonofale health model, initially conceptualised by Fuimaono Karl Pulotu-Endemann (Citation1995). This extension of the original model includes the concepts of tapu (sacred, forbidden) and noa (ordinary, normal) to inform a considered approach towards sensitive health research. Source: Young et al. Citation2022. Reproduced with permission.

When conducting Pacific research, it is important for the authors to position themselves clearly in the research design. We are a team of Pacific (CDY, MMT) and non-Pacific (BEHM, JEG, RJB) researchers based in the community being studied. This research was undertaken as a summer research project by CDY and was their first engagement with research. MMT has extensive experience conducting Pacific-centred research in Pacific communities. This was the first Pacific-centred research study that BEHM, JEG and RJB had conducted.

Methodology

The Kakala research methodology (Helu-Thaman Citation1997) was used to guide the research from conception to conclusion. This Tongan-based methodology is formed around the analogy of a kakala (Tongan garland of flowers) and describes the steps a researcher should consider when engaging with Pacific participants. These are toli, tui and luva; the stages of preparation, weaving and gifting.

Toli

Toli involves picking flowers, leaves and adornments specific to the person the kakala (garland) is being created for. In a research environment, this stage represents preparation for data collection.

Community consultation

We consulted with experts in the local Pacific community on the type of data to be collected, methods of data collection and participant criteria. Experts were approached individually and then invited to one of two formal advisory group meetings. Understanding the risks and discomforts that might arise due to the tapu nature of the research (Veukiso-Ulugia Citation2013; Young et al. Citation2022), we separated groups by age: one for staff and one for students. Altogether, there were five Pacific staff (academic or professional) and five Pacific students (undergraduate or postgraduate) who spanned a range of Pacific nations, ages, genders, sexualities and academic disciplines.

Advisors acknowledged the importance of sexual and reproductive well-being, a topic they described as being ‘shameful’ and rarely discussed within the Pacific community. Advisors suggested questions to be excluded, such as inquiring into participants’ sexual orientation; or included, such as participants’ experiences at the University of Otago, with the hope of generating targeted solutions for the university community. The advisors contributed meaningfully to the study and narrowed the focus and intentions of the research. We departed from the toli stage with their blessings and goodwill.

Participant criteria

Students enrolled at the University of Otago in 2020 who self-identified their ethnicity with a Pacific nation were invited to participate in this study. We were inclusive of migrant populations (e.g. Indian Fijians, Chinese Sāmoans) whose unique cultures are distinct from their origins (Grieco Citation1998).

Tui

Tui is the stage of weaving the kakala from individual components into a physical artefact. In a research environment, this is the stage of data collection and analysis.

Data collection

Data was gathered using REDCap (Harris et al. Citation2009) via a ten-minute mixed methods online survey. Participants were recruited by an email invitation and follow-up reminder through the university’s Pacific student mailing list (permission was obtained to access this list). The study received ethics approval from the University of Otago Human Ethics Committee (Reference: F20/009).

Measures

The survey comprised five sections. Two sections gathered demographic information and quantitative data on participants’ spirituality and religiosity. Three sections prompted Likert scale and open-ended questions on participants’ understandings, experiences and other factors relevant to their sexual and reproductive well-being. Questions were a mix of Likert scale or open-ended questions, depending on the section’s purpose. For example, we might ask an open-ended question (‘In your own words, how would you describe sexual well-being?’) followed by a Likert scale question (‘How much do you agree with the statement, “I am religious”’), or we might present an initial Likert scale followed by an open-ended question (‘How satisfied are you in your knowledge of sexual and reproductive well-being?’ and ‘Why did you answer in this way?’). The full survey can be found in the online Appendix.

Data analysis

Open-ended responses were analysed question-by-question using inductive thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke Citation2006), described in six phases. In phase 1, data were read multiple times prior to analysis for familiarity. In phase 2, initial codes were generated by grouping similar phrases and words together. In phase 3, common themes were identified by grouping similar codes together. In phase 4, themes were reviewed for relevance or further grouping to reduce the data to a more manageable size. In phase 5, themes were named within the context of their question (e.g. Section 1 themes were named according to the purpose of Section 1, and so forth). In phase 6, themes were presented as results with direct quotes intercalated as recommended by King, Cassell, and Symons (Citation2004), and accompanied by participants’ ethnicity, gender and age. Coding was aided by the use of NVivo (QSR Citation2020).

Likert scales (5- and 7-point) were analysed using basic descriptive statistics (Kaur, Stoltzfus, and Yellapu., Citation2018), as inferential analysis was not the purpose of this study. Both thematic and descriptive analyses (in percentages) are reported alongside each other for the benefit of the reader, allowing them to appreciate the themes discussed by this unique cohort, rather than drawing inferences about the population from a small sample size. Although we use suggestive language based on the quantity of responses (e.g. ‘many’ or ‘few’ participants’), we acknowledge that the significance of responses may or may not correlate with the actual number reported. Correlational analysis was not the purpose of this preliminary study.

Luva

This final stage is gifting the kakala to the recipient, who is usually the guest of a special event. It is the practice of ‘ofa (love) and faka’apa’apa (respect) towards the recipient and a moment for joy and celebration. In a research environment, this is the dissemination of research findings back to the community.

Research outcomes

Preliminary results were shared with the advisors at a hosted morning tea. We thanked them for their support and shared kai (food), as is appropriate in Pacific cultures. Formal presentations were delivered at departmental seminars, research meetings and tertiary guest lectures. A range of community-based initiatives have been influenced by this research, including youth events and sexual violence prevention workshops. Other publications and follow-up studies are being planned.

Results

Out of 1,089 students eligible to participate, 156 students (14%) opened the survey link. Incomplete and partially complete surveys were excluded to avoid making assumptions about the participants’ responses, leaving a total of 81 complete surveys (7.4% of eligible students) included in the report. Below, we provide a description of the sample population, followed by three sections: (1) understandings of sexual and reproductive well-being; (2) acquisition of sexual and reproductive health knowledge, and (3) other factors affecting sexual and reproductive health knowledge.

Sample description

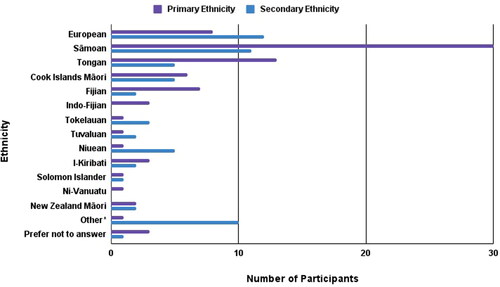

Participants identified themselves with a range of ethnicities (), with most participants (75%) identifying with a secondary ethnicity.

Figure 2. Self-identified primary and secondary ethnicity of survey participants. Other* includes Afrikaans, Chinese, German, Hawaiian, Lebanese, Malaysian, Welsh. Missing n = 1.

Participants identifying their primary ethnicities included Sāmoan (37%), Tongan (16%), European (10%) and Fijian (9%). Three participants did not answer this question. Participants identifying a secondary ethnicity included European (17%), Sāmoan (14%), Tongan (6%) and Cook Islands Māori (6%).

Most participants (84%) were between 18 years to 27 years (). Most (78%) identified their gender as women, with 19% identifying as men and two identifying as genderqueer or genderfluid. Participants were mostly undergraduate (75%, including 21% in their first year of study), and were studying Health Sciences (39%), Sciences (34%) and Humanities (28%).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of survey participants including their age, gender, level of study, division of study and tertiary-level study of sexuality or reproduction.

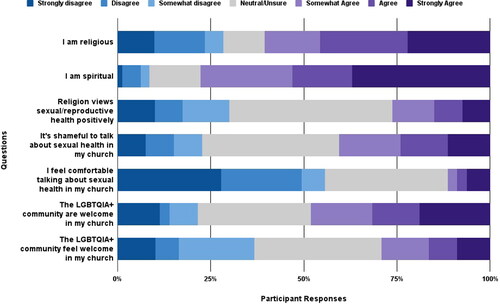

Participants responded to seven statements on a 7-point Likert scale concerning religion and spirituality (). breaks down the religious affiliation of participants.

Figure 3. Survey participants’ responses to 5-point Likert scale questions about religion and spirituality, plotted on a bar graph (scale = 100%).

Table 2. Religious affiliations of survey participants (self-identified).

Understandings of sexual and reproductive well-being

Participants answered open-ended questions about their understandings of sexual and reproductive well-being. Responses to each question are presented with key themes identified during thematic analysis.

Sexual Well-Being

Eighty participants described what they understood about sexual well-being. The main themes identified were that sexuality is an important part of personal identity, that sexuality is influenced by health knowledge, and that sexuality can be expressed through actions and behaviours. One participant struggled to give a definition for sexual well-being, responding, ‘I have never thought about it. I don’t know’.

Theme 1: sexuality is one’s personal identity

Participants (13%) indicated that sexual well-being was an important component of their personal identity, whether they were sexually active or not. Many participants (54%) identified sexual orientation and sexual preference ‘or lack thereof’ as being important. One described sexuality as ‘the capacity to identify your sexual preferences as well as your own sexual identity in a space where you are respected regardless’. Three participants also suggested that gender and gender expression were important aspects of their sexuality.

[Sexual well-being is] the comfort and confidence … about the things you feel and the way you look and actions you take part in … [It is] how you accept yourself and the things you like, such as intercourse … The confidence to be honest with what you like and expressing that to who you feel comfortable with. (Tongan woman, age 20)

Participants (20%) indicated that self-awareness and self-acceptance were part of sexual well-being. One described this as ‘knowing your body wholesomely’. Others described it as having ‘strength of character in sexual identity’ and being ‘emotionally in control, being conscious of sexual needs and feelings’.

Theme 2: health knowledges inform one’s sexuality

Participants (21%) referred to the intersectionality of sexual well-being, one of them writing that it has ‘anatomical, socio-political, emotional and spiritual’ facets. To navigate these spaces, participants suggested the importance of being educated in all aspects of their sexual well-being, including sexual intercourse (31%), sexual orientation (34%) and intimate relationships (8%).

Participants (20%) understood that health is holistic and complex. They identified their sexual and/or reproductive health in the context of ‘the four main aspects of health: mental, social, spiritual and physical’. Two participants specifically referenced the health models of Te Whare Tapa Whā (Durie Citation1998) and Fonofale (Pulotu-Endemann Citation1995).

Three participants reacted negatively to the term ‘well-being’. One described ‘sexual well-being [as] a desire that humans have … it’s not an important one, but it is there’, with another describing it as ‘a new term and … too airy-fairy’. Another thought the term was not required, writing, ‘I can understand sexual health, but well-being - I wouldn’t rely on people’s responses for this’.

Theme 3: sexuality is expressed in behaviours and actions

Participants (48%) indicated that sexual intercourse was an integral component of sexual well-being. A few participants (7%) mentioned masturbation.

[Sexual well-being is] wanting to obtain an optimal level of sexual satisfaction. (Indo-Fijian woman, age 20)

Generally, participants who mentioned masturbation did so without the use of negative language.

[Sexual well-being is having] no guilt because of cultural or religious upbringing … It is much more than pleasure, and if pleasure is the goal, then having healthy communication about it at the start with the other person would be ideal or just wank it off really. (Sāmoan man, age 27)

Participants (31%) indicated that sexual well-being related to whether someone was sexually active or not. Others (11%) suggested it is the actions or behaviours within a sexual environment, either with oneself or an intimate partner, with one young man describing it as having ‘knowledge of safe and unsafe practice around sex’. A young woman’s language suggested it was normal to have multiple sexual partners.

Participants (36%) described the importance of feeling safe and comfortable in all their sexual activities. An ideal sexual interaction to them was feeling in control of the sexual environment, some referring to ‘sex literacy’, ‘consent’ and ‘being proactive about protection. Some participants (14%) measured safety in terms of how confident they were to express and explore their sexuality with an intimate partner.

Reproductive well-being

Seventy-one participants described what they understood about reproductive well-being. Eight of them struggled to define reproductive well-being or did not offer an answer. The main themes identified were about biological processes, fertility and safety.

Theme 1: reproduction is organs, systems and processes

Participants (41%) referred to specific biological processes. These included menstruation, menarche and menopause, contraceptive methods, sexually transmitted infections, sexual health checks and sexual intercourse. Of these responses, one man referenced male anatomy to define reproduction; all other participants used female anatomy to describe reproduction, irrespective of their own gender identity. Participants also referred to female reproductive disorders like endometriosis and ovarian scarring.

Participants (25%) believed reproduction was having optimal health and being free from disease. Responses included the importance of maintaining the hygiene of their reproductive organs (6%), accessing sexual and reproductive health services (8%), and being regularly tested for sexually transmitted infections if they are sexually active (6%). One participant gave the example of ‘Chlamydia … If it goes untreated, [it] can scar your ovaries which could lead to infertility problems’.

Theme 2: reproduction is fertility

Participants (33%) considered fertility to be a key part of reproductive well-being, described as ‘the blessing of being able to carry your pēpē (baby) til you give birth’. Participants (13%) highlighted the importance of autonomy in their fertility, including having free and informed access to methods of contraception to prevent pregnancy, like condoms and birth control. In general, participants acknowledged it was up to individuals to decide when they want to start a family and that contraception was useful for regulating that choice. One participant wrote, ‘having awareness, guidance and a safe space are important … regarding conceiving a child or preventing pregnancy’.

Honestly thought [reproductive well-being] related to sexual well-being, in the sense one eventually leads to the other. But if someone can’t have babies due to illness or sexual orientation, then maybe it’s a lot broader than I imagine. (Sāmoan man, age 27)

The scope of infertility was broad. Participants acknowledged that people who could not have children could suffer emotional, spiritual and mental distress. Some participants (4%) offered solutions to infertility, including adoption and modern procedures to promote pregnancy, like in-vitro fertilisation.

Theme 3: reproduction is being safe and informed

Participants (11%) indicated that reproductive well-being was being fully informed about the decisions they made. They understood the value of a ‘strong education’ such as being educated about ‘personal hygiene’, processes like oocyte fertilisation, ‘knowing about contraception and the basics of how to get pregnant’ and being informed about their own and their partners’ health status. Some (4%) indicated that strong support systems (including family, friends and trusted health professionals) helped in their reproductive health decisions.

[Reproduction is] taking control of the decisions related to your sexuality and reproduction. You get to choose what to do with your body, eg. whether it’s to have a baby or not. (I-Kiribati, gender not given, age 19)

Participants (19%) also stressed the importance of reproductive rights. This included their legal right to use contraception, access abortion services and health clinics that offer services like STI tests, Pap smears and cervical screenings.

Acquisition of sexual and reproductive health knowledge

Participants answered Likert scale and open-ended questions about where they had acquired their sexual and reproductive health knowledge. Responses were categorised under the umbrellas of formal and non-formal education and personal life experiences. Participants also described their level of satisfaction with their health knowledge.

Formal education

Participants (66%) identified formal education as a primary source of sexual and reproductive health knowledge. Participants specifically mentioned university (32%), secondary (20%) and intermediate (3%) schools. One described their knowledge as coming ‘from school initially, but as an adult you become more worldly about sexual matters, orientation and relationships’. Some references to secondary school sexuality education were negative, one participant writing how ‘[the schools] address[ed] the topic in a manner that does not support speaking with confidence … we were discouraged from conversation’.

Non-formal education

Participants (39%) identified non-formal education as a primary source of their sexual and reproductive health knowledge. They identified their parents and family members (20%) or peers and friends (19%) as educators about sexual intimacy and reproductive hygiene. Other participants referenced organised workshops or training they had attended for work (3%), church (3%), or health clinics (11%). A few participants discussed the influence of religion on their understandings of sexuality and reproduction: one participant writing, ‘the church I was raised in helped shape my understanding … of sex as a shameful/taboo thing’.

Personal and life experiences

Participants (53%) identified their personal and life experiences as a primary source of their sexual and reproductive health knowledge. They discussed personal experiences exploring their sexuality through sexual intercourse, intimate relationships, accessing health services pre- and post-sexual interactions and masturbation. Participants (23%) identified various forms of media (e.g. social media, films, books, the Internet) as important resources keeping them informed and up to date with sexual and reproductive health information. One participant wrote, ‘social media and peers have strong influences in [my sexual and reproductive health] because it’s embarrassing to ask all the time’.

Generally, participants (59%) acknowledged their understandings of sexuality and reproduction were acquired by many sources, including specific movies and television series (e.g. Big Mouth, Sex Education), social media platforms (e.g. Facebook, Instagram), online resources (e.g. Scarleteen.com), mobile apps (e.g. period tracker apps) and workshops or training activities they had attended. Only two participants indicated that pornography influenced their understandings of sexuality and reproduction.

Knowledge satisfaction

Participants indicated a range of satisfaction with their sexual and reproductive health knowledge. Most were satisfied (49%) and had no questions (85%), but many (31%) were neutral or unsure. Some (20%) were unsatisfied with their knowledge of sexuality and reproduction.

Participants who asked questions wanted clarification on the difference between sexual and reproductive well-being and specific definitions of them. They asked about contraceptive methods, how they work and how to access them. They wondered whether Pacific women feel comfortable accessing sexual health services, like family planning, and asked what the average age of menarche (first menstruation) was as they ‘would like to know if [other Pacific women] too struggled with cultural barriers and if they had any support to prepare them for womanhood’.

Other factors influencing sexual and reproductive health knowledge

Participants answered Likert scale and open-ended questions about other factors impacting their knowledge of sexuality and reproduction. These identified their comfortability discussing these topics, common myths, and perceived cultural barriers, as important factors influencing their understandings.

Comfort

Participants were slightly more comfortable talking to their friends (69%) than their family members (66%) about sexual and reproductive health. Additionally, women were more confident (90% vs 80%) and comfortable (81% vs 67%) than men in talking to relatives about these topics. It comes as little surprise that all participants generally identified female relatives (mothers (47%), sisters (28%), aunties (13%)) as people they would go to rather than male relatives (father (17%), brother (8%)).

Participants who were uncomfortable approaching family members identified the pressures of culture and religion as barriers. They perceived sexuality and reproduction as abnormal topics and inappropriate to be discussed with family because of religious (21%) and cultural (16%) norms. Participants described feeling ‘awkward’, ‘weird’, ‘private’ and ‘shameful’ talking about these topics because ‘speaking about them with family members could be seen as disrespectful’. These participants felt equally as uncomfortable talking to their family (32%) as they perceived their family feeling uncomfortable talking to them (32%). One participant wrote:

As I have gotten older, I have become more open to talk about this conversation. However, I do not think they [mother and sister] have a proper understanding of sexual and reproductive well-being as they are from an older generation … which has a different perception on this topic. (Niuean-Tongan woman, age 20)

Common myths

Participants were asked whether they were aware of any myths surrounding sexuality and reproduction. Some participants (36%) were aware of myths, others (17%) not, but many (42%) were unsure. Four participants did not answer.

Some myths that were identified concerned the hymen and virginity. These included the belief that a woman’s first sexual intercourse should hurt and result in bleeding. These expectations were highlighted by a Tongan participant who referred to the ‘white cloth’ ceremony, where the marital bedsheet is expected to be stained with blood after the wedding night and ‘if a girl does not bleed during her first intercourse with her husband, she is cursed or “not pure”’. Participants also identified myths about sexual purity such as the idea that ‘sexual purity and morality are linked’. These sorts of ideas were often tied to religious beliefs that premarital sex, same-sex relationships or having multiple sexual partners is sinful. Another myth was identified that ‘the more sex a woman has, the “looser” her vagina will be’.

Myths were also mentioned concerning sexually transmitted infections (e.g. ‘if you are engaging in sexual activity, you will get an STI’ and ‘you can’t get STIs from oral sex’) and contraception (i.e. ‘that pulling out [during sex] works’ to prevent unwanted pregnancy and that ‘all contraception is 100%’ effective). One participant acknowledged that sexuality education is perceived to ‘encourage young people to have sex, but … it serves to better educate [us] about safe sex and may prevent unwanted pregnancies and [STI] transmission’. Other myths related to sexual intercourse were that ‘sex is male focused’ and that if someone consents ‘once, that doesn’t mean [they] can’t change [their] mind’. Others were that men should ‘have a big penis to pleasure women’ and ‘that spouses are always entitled to sex’.

Cultural pressures

Most participants (93%) felt that cultural values created barriers to open discussion about sexuality and reproduction. Only one participant indicated that culture was not a barrier ‘because a lot of it is based on personal decisions. Even with the external influences, you still have the power to choose’. Five participants did not answer the question ‘do you think cultural values create barriers against discussing sexual or reproductive well-being?’

Participants indicated that tapu influences sexuality and reproduction by creating ‘an environment of awkwardness’ and ‘since it’s seen as such a sacred thing, people shy away from talking about it’. This appeared to hinder knowledge-sharing between generations and lead to misunderstanding of these topics. One participant wrote that their ‘parents chose not to discuss sexuality with [them] … which led to many misunderstandings of sexuality which [they] now have to readdress personally’. Others shared that their ‘freedom of expression [is] very limited’ in a cultural environment, although one participant described their relief of living in Aotearoa New Zealand:

Pacifika are religious fanatics, speaking such matters will lead to disownment. In the islands, you would be beaten with a club. Praise God, I am in New Zealand. (Sāmoan man, age 34)

‘a separation between boys and girls … neither are taught properly about the other (or even themselves) and this creates a sense of alienation between the sexes, encouraging misinformation [and] misunderstandings about sexual and reproductive health’. (Sāmoan woman, age 24)

Another participant suggested that ‘shotgun weddings’ were the result of cultural pressure to hide the shame of premarital sex. No other specific examples of cultural pressures were given.

Discussion

This study was the first to investigate Pacific young people in tertiary education and their understandings about sexual and reproductive health and their sources of information. A key finding was that participants connected their knowledge to their perceptions, beliefs and attitudes towards sexuality and reproduction. The interconnected themes highlighted above suggest that sexual and reproductive health knowledge cannot be investigated without understanding the wider personal and cultural context of participants. This is further rationale for the use (and value) of a holistic model, like the revitalised Fonofale model, when conducting sensitive health research in Pacific communities.

Participants also demonstrated complex and holistic understandings of sexual and reproductive health. Their references to sexual orientation, gender identity and expression were interconnected with discussion of genitalia and biological processes such as puberty and menstruation. The theme of self-determination and autonomy was at the forefront of many responses, with participants stating they were ‘taking care and control of [their] own self’. Unexpectedly, the cultural diversity of our study sample was not reflected in the survey responses. The responses were dominated by Polynesian examples and values, like the Tongan white cloth ceremony and concept of vā, which may be consistent with the higher proportion of Polynesian participants. As a result, we continue to wonder about non-Polynesian Pacific peoples’ (i.e. Micronesian and Melanesian) understandings of sexuality and reproduction, and whether their perspectives are influenced by the Polynesian-dominant culture of Pacific Aotearoa.

Throughout the study, participants identified both formal and non-formal learning environments as valuable in developing their sexual and reproductive health knowledge. Valuable formal sexual and reproductive education was identified from as early as primary school to as recent as tertiary studies by the same participants. Similarly, non-formal learning environments – such as peer groups, workshops, training events and conferences – appeared to be equally as impactful. This suggests that alternative learning environments may provide valuable opportunities to supplement sexual and reproductive health knowledge outside the formal classroom environment. As many Pacific researchers have reiterated in the past, there is a need for collaborative action between formal institutions and community groups. This communication would ensure that Pacific youth, attending universities or not, have a wrap-around education and support in every space they enter.

Participants in this study demonstrated help-seeking strategies when faced with sexual or reproductive health challenges. Although most had strong peer networks or family members they felt comfortable asking for support, many participants identified a range of media platforms they used to educate themselves about sexuality and reproduction. These ranged from social media and the Internet, to television and film. It would be interesting to investigate the search strategies participants used to identify and filter reliable Internet information. Importantly, these findings contradict past work suggesting that Pacific peoples are ‘health illiterate’ and unable to take control of their own lives and well-being (MoH 2012; University of Otago and Ministry of Health Citation2011).

Limitations

Like all research, this study has its limitations. In particular, because of the overall pattern of response we were unable to systematically investigate the experiences of different ethnicities, ages and genders. We had a small sample size, likely due to the sensitivity of this topic. The online survey format may also have restricted participants’ responses, as Pacific cultures have strong oral traditions, and so follow-up qualitative studies would be beneficial to supplement these findings. Although many participants identified sexual orientation as an important component of sexual health, we did not ask participants to identify their own in the survey following the advice of the consultation groups. It is important to recognise too that students in tertiary education are a relatively privileged group, signalling the need for follow-up work to capture a more diverse range of perspectives.

Conclusion

This was the first pan-Pacific study conducted in Aotearoa New Zealand to investigate what university students understand about sexuality and reproduction and what contributes to this knowledge. This study highlighted that Pacific young people have strong understandings of the fundamental components of health and well-being, and the ability to seek information from trusted sources, human or digital. It is clear Pacific young people desire to speak more openly and freely about sex, relationships, sexuality and reproduction, indicative of the unique needs of a new generation of Pacific Aotearoa young people. Further studies are needed in Pacific communities to broach these important and topical areas of health.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (58.6 KB)Acknowledgements

Special thanks go to our advisors: Mary-Jane Kivalu, Jesse Kokaua, Therese Lam, Melissa Lama, Jaye Moors, Shivankar Nair, Michelle Schaaf, Troy Tararo-Ruhe, Renee Topeto and Patrick Vakaoti.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflicts of interest are reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The development of the revitalised Fonofale model was informed by valuable insights from various cultural advisors, including Taime Pareanga Samuel and Vaivaimalemalo Michael Fusi Ligaliga.

References

- Allen, L. 2014. “Don’t forget, Thursday is test[iscle] time! The Use of Humour in Sexuality Education.” Sex Education 14 (4): 387–399.

- Anae, M. 2010. “Teu Le Va: Toward a Native Anthropology.” Pacific Studies 33 (s 2/3): 222–240.

- Anae, M., N. Fuamatu, I. Lima, K. Mariner, J. Park, and T. Suaalii-Sauni. 2000. “Tiute Ma Matafaioi a Nisi Tane Samoa i le Faiga o Aiga.” The Roles and Responsibilities of Some Samoan Men in Reproduction. Auckland: Pacific Health Research Centre.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101.

- Durie, M. 1998. Whaiaora – Māori Health Development. Auckland: Oxford University Press.

- ERO (Educational Review Office). 2018. Promoting Wellbeing Through Sexuality Education. Wellington: Educational Review Office.

- Fa’avae, D. 2016. “Tatala ‘a e Koloa ‘o e To’utangata Tonga i Aotearoa mo Tonga: The Intergenerational Educational Experiences of Tongan Males in New Zealand and Tonga.” PhD diss., University of Auckland. http://hdl.handle.net/2292/32183.

- Fitzpatrick, K., H. McGlashan, V. Tirumalai, J. Fenaughty, and A. Veukiso-Ulugia. 2022. “Relationships and Sexuality Education: Key Research Informing New Zealand Curriculum Policy.” Health Education Journal 81 (2): 134–156.

- Grieco, E. 1998. “The Effects of Migration on the Establishment of Networks: Caste Disintegration and Reformation Among the Indians of Fiji.” The International Migration Review 32 (3): 704–736.

- Harris, P., R. Taylor, R. Thielke, J. Payne, N. Gonzalez, and J. Conde. 2009. “Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) – A Metadata-Driven Methodology and Workflow Process for Providing Translational Research Informatics Support.” Journal of Biomedical Informatics 42 (2): 377–381.

- Helu-Thaman, K. 1997. “Kakala: A Pacific Concept of Teaching and Learning.” Paper presented at the Australian College of Education National Conference, Cairns.

- Ikihele, A. M., and V. Nosa. 2019. “Mothers and Sisters: Educators of Sexual Health Information Among Young Niue Women Born in New Zealand.” Pacific Journal Reproductive Health 1 (9): 513–520.

- Katavake-McGrath, F. 2021. “Our Way to Home: An Exploratory Study of Pasifika Gay Men in New Zealand, their Lived Experience and their Navigation of Sexual Orientation Related Legislative Change.” PhD diss., Auckland University of Technology. http://hdl.handle.net/10292/14134.

- Kaur, P., J. Stoltzfus, and V. Yellapu. 2018. “Descriptive Statistics.” International Journal of Academic Medicine 4 (1): 60–63. https://www.ijam-web.org/text.asp?2018/4/1/60/230853.

- King, N., C. Cassell, and G. Symons. 2004. “Using Templates in the Thematic Analysis of Text.” Chap. 21 in Essential Guide to Qualitative Methods in Organizational Research edited by 256–270. London: SAGE doi:10.4135/9781446280119.n21

- Matenga-Ikihele, A. 2012. “Let’s Talk about Sex: Knowledge, Attitudes and Perceptions Towards Sexual Health and Sources of Sexual Health Information Among New Zealand Born Niuean Adolescent Females Living in Auckland.” University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand.

- Mills, A. 2016. “Bodies Permeable and Divine: Tapu, Mana and the Embodiment of Hegemony in Pre-Christian Tonga.” In New Mana: Transformations of a Classic Concept in Pacific Languages and Cultures, edited by M. Tomlinson and T. Kāwika Tengan, 77–105. Canberra: Australian National University Press.

- MoE (Ministry of Education) 2013. New Zealand Health Survey 2014/15: New Zealand Population Census. Wellington: Ministry of Education.

- Naea, N. 2008. “Navigating Many Worlds: Samoan Mothers’ Views on Sexuality Education.” Master’s diss., University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand.

- Nosa, V., N. Taufa, J. Paynter, and A. L. Tan. 2018. “A Qualitative Study of Pacific Knowledge and Awareness of Gynaecological Cancers in Auckland, New Zealand.” Pacific Journal Reproductive Health 1 (7): 356–363.

- Pulotu-Endemann, K. 1995. “Fonofale Model of Health.” In Strategic Directions for Mental Health Services for Pacific Island People, edited by the Ministry of Health. Wellington, Ministry of Health.

- QSR (QSR International Pty Ltd). 2020. NVivo.” https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home.

- Sa’uLilo, L., E.-S. Tautolo, V. Egli, and M. Smith. 2018. “Health Literacy of Pacific Mothers in New Zealand is Associated With Sociodemographic Factors and Non-Communicable Disease Risk Factors: Surveys, Focus Groups and Interviews.” Pacific Health Dialog 21 (2): 65–70.

- Statistics New Zealand. 2018. “Pacific Peoples Ethnic Group.” Accessed, July 2022. https://www.stats.govt.nz/tools/2018-census-ethnic-group-summaries/pacific-peoples

- Tanuvasa, A. 1999. “The Place of Contraception and Abortion in the Lives of Samoan Women.” PhD diss., Victoria University of Wellington. http://hdl.handle.net/10063/1371

- Tupuola, A.-M. 1998. “Fa’asamoa in the 1990s: Young Samoan Women Speak.” In Feminist Thought in Aotearoa New Zealand: Connections and Differences, edited by R. D. Plessis and L. Alice, 51–56. Auckland: Oxford University Press.

- Tupuola, A.-M. 2004. “Talking Sexuality Through an Insider’s Lens: The Samoan Experience.” In All About the Girl: Culture, Power and Identity, edited by Anita Harris, 115–125. New York: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203492567

- Ulugia-Veukiso, A. 2010. “What’s God Got to do with Sex? Exploring the Relationship between Patterns of Spiritual Engagement and the Sexual Health Activities of Samoan Youth.” Master’s diss., Massey University. http://hdl.handle.net/10179/783.

- University of Otago and Ministry of Health 2011. A Focus on Nutrition: Key Findings of the 2008/09 New Zealand Adult Nutrition Survey. Wellington: Ministry of Health.

- Veukiso-Ulugia, A. 2013. Best Practice Framework for the Delivery of Sexual Health Promotion Services to Pacific Communities in New Zealand. Wellington: Ministry of Health.

- Veukiso-Ulugia, A. 2016. “Good Sāmoan Kids’ – Fact or Fable?: Sexual Health Behavior of Sāmoan Youth in Aotearoa New Zealand.” New Zealand Sociology 23 (1): 74–95.

- Veukiso-Ulugia, A. 2017. “Sexual Health Knowledge, Attitudes and Behaviour of Sāmoan Youth in Aotearoa New Zealand.” PhD diss., Massey University, Albany. http://hdl.handle.net/10179/12338.

- Veukiso-Ulugia, A. n.d Literature Review on the Key Components of Appropriate Models and Approaches to Deliver Sexual and Reproductive Health Promotion to Pacific Peoples in Aotearoa New Zealand. Prepared for the Ministry of Health, New Zealand. https://tewhariki.org.nz/assets/literature-review-pacific-sexual-health-final-612kb.pdf

- Young, C. D., R. J. Bird, B. E. Hohmann-Marriott, J. E. Girling, and M. M. Taumoepeau. 2022. “The Revitalised Fonofale as a Research Paradigm: A Perspective on Pacific Sexuality and Reproduction Research.” Pacific Dynamics: Journal of Interdisciplinary Research 6 (2): 186–201.