Abstract

Growing evidence suggests that young migrants are particularly vulnerable to sexual violence. As young migrants often lack family and social networks, professionals are often the recipients of disclosures of sexual violence. This study aimed to explore how professionals experience young migrants’ disclosures of sexual violence. A qualitative design was used, based on 14 semi-structured interviews with a range of professionals from the public sector and civil society in southern Sweden. The data were analysed using qualitative content analysis. The overarching theme developed was ‘coming across the hidden problem of sexual violence in an excluded population’ supported by three sub-themes: ‘linking structural marginalisation and vulnerability to sexual violence’; ‘realising that sexual violence is one among many other concerns’; and ‘taking pride in backing up young people betrayed by society’. Professionals expressed a strong sense of responsibility due to the complex vulnerabilities of young migrants and their lack of access to services. This, coupled with the lack of clarity about how to respond to disclosures of sexual violence, can lead to moral distress. There is a need to strengthen support for professionals, including recognition of ethical dilemmas and the establishment of formal connections between organisations making access more straightforward and predictable.

Introduction

International migration has been on the rise globally and in Sweden, where the population of non-Swedish-born persons has risen from 11.3% in 2000 to over 20% at the end of 2021 (SCB Citation2022). Migrants in Sweden are not a homogeneous group. They come from different countries and have different backgrounds; they have also migrated for different reasons and have different legal statuses. They can be asylum seekers (seeking international protection) or refugees (having legal recognition of the right to international protection), labour migrants or international students, spousal or family migrants. Some of them may also be undocumented—without the right to residency, and who can originate from any of the other groups of migrants.

The peak migration rate was reached in 2015 when Sweden took in the largest number of international migrants per capita of any OECD country ever recorded (OECD Citation2016). This resulted in a drastic shift in Swedish migration policy in 2016 from one of the most generous migration policies in the EU to meeting EU minimum standards (Law 2016:752 Citation2016). It also resulted in the introduction of prolonged asylum-seeking processes particularly affecting unaccompanied migrant children who in many cases turned 18 before their asylum applications were processed. Asylum seeking children have access to more rights and services than adults, including access to school, social services and healthcare services. Asylum seeking adults and undocumented migrants only have access to health care which cannot be deferred (Law 2013:407 Citation2013). In Sweden, civil society organisations play a critical role providing services that are not covered by the public sector social welfare services (Ouis Citation2021).

Asylum seeking adults rarely have employment permits and are dependent upon a daily subsistence allowance provided by the Swedish Migration Agency. For young migrants without children, that amount is between SEK 50 (11–17 years) to SEK 71 (from 18 years) per day (approximately USD 5 or USD 7) and is paid out only if they reside in approved accommodation or in an approved neighbourhood.

Growing evidence suggests that migrants are particularly vulnerable to sexual violence (De Schrijver et al. Citation2018) at all stages of the migratory process including in their home countries, enroute and in their countries of destination (Chynoweth, Freccero, and Touquet Citation2017; Mason-Jones and Nicholson Citation2018; Ouis Citationforthcoming). Young people have always been at greater risk for sexual violence (WHO Citation2002) and there is evidence of a double burden of vulnerability for young migrants. For example, a recent mapping study of young migrants’ sexual and reproductive health and rights carried out by the Public Health Agency of Sweden found that 25% of young migrants had experienced some form of sexual violence (Folkhälsomyndigheten Citation2020).

Sexual violence is a broad term lacking an agreed upon definition and encompassing many different types of behaviours including rape, sexual harassment, sexual abuse, unwanted sexual advances and forced marriage (WHO Citation2011). Key to the concept of sexual violence is sexual coercion, specifying that sexual violence does not necessarily need to involve the use of physical force, but rather involve issues of choice, power and consent.

The experience of sexual violence is associated with negative physical and mental health outcomes (Bentivegna and Patalay Citation2022) which have consequences not only for migrant youth as individuals but also for how they integrate into a new society (Basile and Smith Citation2011). Sexual violence is often a taboo subject, strongly associated with stigma and shame and notoriously underreported. This underreporting is even more true of migrants in that they have lower response rates to health-related surveys in general (Carlsson et al. Citation2006) and to questions about sexual violence in particular. Many migrants in Sweden come from conservative cultures, some of which have honour-related norms, making discussion of sex and sexuality even more difficult.

Although non-disclosure rates are often high (Ullman et al. Citation2020), experiences of sexual violence are disclosed (Ahrens et al. Citation2007). With the growing number of young migrants at heightened risk of sexual violence and often lacking family and social networks, health, education and social service providers can be the recipients of such disclosures. Understanding how professionals experience disclosures of sexual violence by young migrants can deepen our understanding of the vulnerability of young migrants to sexual violence, the responses available and the support required. To our knowledge there is no published research conducted in Sweden focusing on different public sector and civil society professionals’ experiences of young migrants’ disclosures of sexual violence.

This study aimed to explore how professionals and service providers experience meeting young migrants exposed to sexual violence. More specifically, it explores how they understand sexual violence experienced by young migrants, how they perceive their professional roles and responsibilities in relation to the young migrants that they meet, how they experience young migrants’ disclosures of sexual violence, and what strategies they employ to navigate these encounters.

Methods

Research design

The study employed a qualitative design utilising individual interviews to gain a deeper understanding of professionals’ experiences of disclosures of sexual violence by young migrants.

Study setting

The study setting comprised two cities in the south of Sweden with large migrant populations and with an active civil society sector catering to them (Malmö and Gothenburg).

Sampling

Maximum variation sampling was employed to reach the breadth of participants employed in different occupations who were meeting young migrants during the course of their work. Young migrants were defined as persons aged 15–30 years with migration experience. Initial participants were identified through discussions with two key informants, one from the public sector and one from civil society, to identify relevant organisations and services in Malmö. These included different healthcare services, social services, schools, care homes and the police. Emails were sent out to all identified individuals and organisations and followed up with reminders. At a second stage of recruitment, snowball sampling was employed resulting in the inclusion of two participants from Gothenburg. Persons were eligible to participate if they had experienced disclosures of sexual violence from young migrants during their work. Fourteen participants were included. The sample was deemed to provide sufficient information power for the intended analysis as the group of professionals with experience of disclosures of sexual violence by young migrants is limited (Malterud, Siersma, and Guassora Citation2016).

Data collection

Data were collected through in-depth individual interviews using a semi-structured interview guide. Questions focused on four key areas: (1) participants’ understanding of sexual violence; (2) participants’ experiences of a meeting with a young migrant during which sexual violence is disclosed; (3) participants’ reflections about working in a context in which sexual violence can be disclosed by young migrants; and (4) participants’ perceptions of how their organisation works with young migrants and sexual violence. All interviews were conducted by the first author and took between 35 and 90 min. All were conducted in Swedish except for one conducted in English.

Interviews were conducted by the first author between December 2021 and September 2022. An initial pilot interview was conducted, which was subsequently included in the analysis as it was deemed to be of sufficient quality and did not result in changes to the interview guide. Interviews were conducted in person, by video meeting, and by telephone. It was considered appropriate to use video and telephone interviews not only to be able to reach participants in other geographic areas but also to facilitate participation (Janghorban, Latifnejad Roudsari and Taghipour Citation2014; Oliffe et al. Citation2021).

Analysis

Manifest and latent qualitative content analysis, as described by Graneheim and colleagues (Graneheim, Lindgren, and Lundman Citation2017; Graneheim and Lundman Citation2004) was performed.

The first author had primary responsibility for analysis. Interviews were transcribed verbatim and translated from Swedish to English, after which relevant meaning units were identified. Meaning units were condensed and coded inductively. Codes were then re-contextualised into categories by moving between deductive and inductive processes. This phase in the analysis was carried out until the formulation of the themes at the latent level, at which point pre-understanding was reintegrated into the analysis. Through a process of going back and forth between codes, categories and themes involving several co-authors, an overarching theme was identified. Preliminary results were discussed between all co-authors and consensus reached. shows an example of the analytical process.

Table 1. Example of the analytical process.

The analysis was facilitated by the use of Excel version 16.66.1 and NVivo release 1.6.2.

Ethical considerations

Participants were sent written information about the study in the days before the interview including the aim and purpose of the study, the fact that participation was voluntary and that they were free to withdraw at any time. This information was repeated orally before the start of the interview, and an opportunity to ask questions was provided. Confidentiality was assured and each interview was assigned a number. No names were recorded at any point in the data collection process and any other identifying information was removed from the transcript. Consent was recorded orally. All data were stored on encrypted USB drives kept under lock and key in a data safe accessible only by members of the research team. Consent files were stored separately from transcription and interview files. As sexual violence is a sensitive topic, all participants were provided with information about where they could access support should they wish to do so following the interview. The study was approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (drn. 2021:03510).

Findings

The fourteen participants came from a variety of different professional fields and included nurses, midwives, social workers, lawyers, counsellors, coordinators and the police. The sample consisted of ten female and four male participants (between 30 and 68 years of age). Eight came from the public sector and nine from civil society organisations.

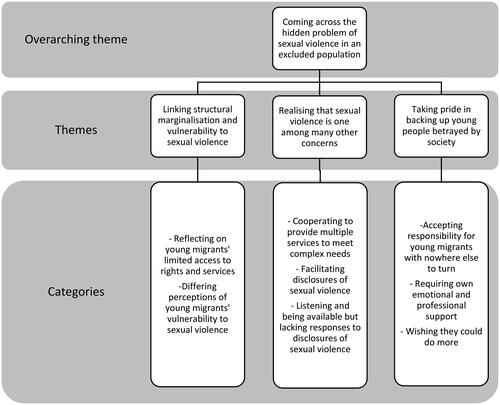

The overarching latent theme developed in this study was: ‘coming across the hidden problem of sexual violence in an excluded population’. This overarching theme is built on three sub-themes, as detailed below (see ). The first sub-theme, ‘linking structural marginalisation and vulnerability to sexual violence’, refers to participants’ understanding of young migrants’ vulnerability to sexual violence. Sub-theme 2, ‘realising that sexual violence is one among many other concerns’, refers to participants’ experiences of the meetings that they as professionals have with young migrants and how they experience disclosures. Sub-theme 3, ‘taking pride in backing up young people betrayed by society’, refers to how professionals and service providers navigate the tensions in their work.

Figure 1. Analytical model illustrating professionals’ experiences of meeting young migrants exposed to sexual violence.

Coming across the hidden problem of sexual violence in an excluded population

This overarching theme reflects participants’ feeling that the sexual violence that young migrants are exposed to was largely unrecognised (the hidden problem) and the result of the fact that they often live very vulnerable lives, largely outside of mainstream society.

Linking structural marginalisation and vulnerability to sexual violence

This sub-theme reflects participants’ views that the young migrants they meet face many different layers of vulnerability and that this vulnerability is largely a consequence of various laws and policies that affect them.

Reflecting on young migrants’ limited access to rights and services

Participants reflected on the different rights and services young migrants may or may not have access to, depending on their residency status and the many barriers to gaining residency.

I think many people get denied because the grounds for asylum are so narrowly defined but also because of how narrowly credibility is determined by the Migration Agency. They cannot be incoherent, or vague or jump to different points in time in the story. They need to provide a clear timeline which is generally difficult but even more so if you have been traumatised, have PTSD or anything else that might affect access to memories. Participant 8, female, counsellor.

A key role played by civil society organisations is that of facilitating access to different social welfare services and trying to manage the many barriers to service access migrants face. Although all migrants have the right to healthcare that cannot be deferred, this is interpreted differently by different healthcare providers. As a result, they meet many young migrants who have been denied services. Participants also reflected on barriers to accessing social services including the requirement of identification, which can be an issue for asylum seekers and undocumented young migrants and the requirement of providing an address, information which they are obliged to share with the police if asked. Undocumented migrants are particularly wary of the police as they enact deportations. Different municipalities have different policies regarding young migrants’ eligibility for social services and several participants highlighted the importance of individuals to enable access to certain services.

What support is available depends very much on what municipality one is in; the same goes for access to shelters. If the right person is contacted it can go quickly; if not one may not get access at all. Participant 6, female, counsellor

They also reflected on the fact that young migrants may lack information about their rights and about what services are available but also that many face internal barriers including a lack of trust in public sector services.

A key issue raised in terms of the vulnerability of young migrants was a lack of the right to work or a lack of access to employment when the right exists. An inability to provide for oneself through legal means leaves only illegal options for sources of income including black-market employment, criminality and sex work, all of which enhance vulnerability to sexual violence.

Not having a safe place to stay was perceived as making young migrants especially vulnerable to sexual violence. Homelessness, living in crowded conditions or being dependent on others for a place to stay were common problems, even among young migrants with residency permits.

Lacking basic rights opens up the possibility of being exploited. It is actually quite obvious; they have to meet their basic needs in some way. It also makes having any form of risk assessment difficult. You might have to sleep somewhere where you are not safe or at an unsafe person’s place. Or to make money. You end up in a very risky environment. Participant 14, female, social worker.

Several participants reflected on the solidarity among young migrants in the context of limited options and choices. Despite, or maybe because of the lack access to rights and services, they are very active in helping themselves and helping each other.

I think it is often forgotten that these young migrants help each other a lot. Often in an emergency situation someone (another young migrant) might find them a place where they can crash for a few days. They support each other in issues of sexual violence or social vulnerability. They do a lot for each other. Participant 4, female, counsellor.

However, a few participants felt that they might meet young migrants who are still relatively well off and that there might be others who are no longer willing or able to seek help.

The more obstacles you face and the less support you get, the lower your motivation for change will be. You must have hope along the way. Participant 11, female, counsellor.

Differing perceptions of young migrants’ vulnerability to sexual violence

Different participants received disclosures of different types of sexual violence. In general, participants meeting girls and young women encountered more cases of intimate partner sexual violence, honour-related violence and trafficking, while those meeting boys and young men as well as LGBTQ migrants more often encountered non-partner sexual violence, survival sex or sex in exchange for meeting basic needs.

For example, most participants from the healthcare services received disclosures of sexual violence by young women or girls and nearly all of these were perpetrated by a family member or a friend of the family. On the other hand, disclosures by young men and boys of experiences of sexual violence were reported more often by participants working for civil society organisations.

Being dependent on the perpetrator, being exploited or harassed by a person in a position of power, or not knowing whom to trust were vulnerability factors for sexual violence mentioned in relation to all groups of young migrants. Although participants had experienced disclosures of sexual violence, many suspected that there were also many cases that were never disclosed.

I also think there are many cases of sexual violence that we don’t find out about. There are often many signs of sexual violence and sometimes we ask questions but never really get to the bottom of it. Participant 6, female, counsellor.

Several participants also mentioned barriers to disclosure arising from the use of interpreters. Disclosure of sexual violence involves negotiating a number of barriers including stigma, shame and lack of trust. When an interpreter is present, these barriers need to be overcome in relation to two people instead of one.

Realising that sexual violence is one among many other concerns

The sub-theme reflects participants’ view that young migrants have numerous interconnected needs and face complex difficulties, among which sexual violence may be only one, and perhaps not the most serious issue being confronted.

Cooperating to provide multiple services

Participants and the organisations they worked for provide young migrants with an array of different services including healthcare services, counselling, integration support, legal advice, police services and practical support in accessing food, groceries, clothing and accommodation. Many participants support young migrants through contacts and referrals to other services and highlighted the importance of partnerships with individuals and organisations to facilitate access. At the same time participants reflected on the many challenges to working together, particularly with public sector services and the numerous legal and policy barriers to supporting young migrants.

Facilitating disclosures of sexual violence

Participants described the strategies they employed when meeting young migrants. Most important were approaches to building trust, including allowing the meeting to take time, letting the young person take the lead, listening and being present and making sure to follow up on any referrals or next steps. Having the opportunity to meet the young migrant multiple times was considered particularly important for disclosure.

We work holistically. They come to us for different things and the trust grows the more often that they come. It might be more natural for them to disclose (sexual violence) to us. Participant 7, female, coordinator.

All participants reflected on the importance of their professional role, and about being clear about what support they can provide and what they cannot provide. They also highlighted the tension between the need to be flexible in working with young migrants while staying within the legal and policy boundaries of their work.

We need to know how to use the system when it comes to the legal aspects, particularly when it comes to minors. Sometimes they might not have any identification documents at all. On the other hand, we do need to keep patient records. We are responsible for that even if we get patient who would rather be anonymous. We have to stay within the boundaries of the law while trying to be flexible to address the individual’s specific situation. Participant 13, female, midwife.

Several participants highlighted the need to ask specifically about sexual violence to facilitate disclosure, to be able to put sexual violence into words, and to indicate a level of comfort in discussing difficult issues. This approach could overcome at least some of the barriers to disclosure.

I think it is difficult to describe (sexual) violence in words and sometimes clients don’t know how to bring it up. But if I ask directly, I feel that it becomes easier for them to say the words. Participant 1, female, social worker.

All participants reflected on the fact that none of the young migrants came to them seeking support for sexual violence, but that the disclosure took place while seeking support for something else which in turn could be related to their exposure to sexual violence.

One doesn’t meet to discuss sexual violence; one meets to discuss another need, for example accommodation, that they want help to find some other accommodation because they are being sexually exploited where they are. So often one is talking about something else, but sexual violence comes up during the conversation. Participant 5, female, lawyer.

Listening and being available but lacking responses to disclosures of sexual violence

All the participants stressed the need to be receptive when listening to the experiences of young migrants, by being available, accessible and permissive. Participants needed to be fully present in the meeting while at the same time putting their own feelings and emotions on hold so as to focus on the young person and their needs. Several participants expressed the importance of not imposing their own definitions on a young migrant’s experiences but on the other hand, many also stressed the importance of being clear about behaviour that is not acceptable.

If someone has lived with sexual violence for a long time or has been living with the memory of it for a long time it is easy to normalise it. I think it is important to indicate what is not okay. That way they can develop their own sense of what is not okay, and they can maybe ask for help. Participant 6, female, counsellor.

Several participants expressed frustration at the lack of clarity about what to do and how to respond to disclosures of sexual violence.

The problem here is that the continuity-of-care chain is not established. We are at the stage where we are trying to identify people (who have experienced sexual violence) […] But where all these identified people are going to be referred, we still do not know. Participant 13, female, midwife.

Participants were ambivalent about encouraging young migrants to report the sexual violence to the police. They expressed uncertainty about whether this would be in the young person’s best interest, particularly in the case of undocumented migrants at risk of deportation. They also expressed an awareness of the difficulties surrounding investigations and convictions for sexual violence, especially if no physical evidence was collected by the healthcare services or if the exposure had occurred some time in the past. Both of these conditions characterised the majority of disclosures that they received.

Who am I to say that they should report to the police; it is not at all sure that it is in their best interest. It could be worse, and it is awful that it is this way! It is so difficult. Participant 4, female, counsellor.

Other participants expressed a feeling of powerlessness at not being able to do anything to respond to the underlying structural vulnerability that facilitated the exposure to sexual violence, particularly in the case of young undocumented migrants.

With this person I knew I could get him a conversation with a counsellor or psychologist but there was nothing I could do to fix the situation that resulted in the sexual violence since it is illegal for him to work. He has nowhere to live; he has no ID or bank account. Participant 8, female, counsellor.

Often there were no referrals made in response to disclosures of sexual violence.

The most common response to disclosure of sexual violence is that it stops there. In the conversation between us. Participant 10, male, nurse.

Taking pride in backing up young people betrayed by society

This sub-theme reflects the fact that on the one hand participants felt very proud of the important work that they were doing trying to meet the needs of these young migrants while at the same time they were frustrated that society allows these young people to live in situations that expose them to sexual violence.

Accepting responsibility for young migrants with nowhere else to turn

Participants generally felt a great deal of responsibility towards young migrants. They wanted to address the most urgent sources of vulnerability and felt they had to play many roles.

My level of responsibility felt is great as the trust placed in me is great - we are their family, community and only network in Sweden […] I feel like I am perceived as being omnipotent. For some of them I am their last resort. Participant 2, female, coordinator.

Many also expressed disappointment about having to take over this degree of responsibility from society, community and family.

If you ask me what I would want more broadly there would need to be entirely new structures in place. I wish there was access to healthcare and housing for all so that we from the not-for-profit sector would not need to carry such a heavy load. Participant 8, female, counsellor.

Requiring own emotional and professional support

Participants felt that some of their meetings with young migrants could be very difficult but at other times they could be experienced as very positive, especially when they had managed to build trust with the young person so that they have felt comfortable enough to disclose experiences of sexual violence. Some felt that they had got used to working with very vulnerable young migrants and that it was not so difficult anymore. Regardless, all participants reflected on the importance of receiving support not only for the emotional aspects of the meetings but also for the professional anchoring of their responses. Most participants felt that they received support from immediate colleagues and most also had regular access to an external supervisor or counsellor.

We share often. On the one hand we discuss cases to see if we have come to the right conclusions. Through raising the issues ourselves, we can get feedback; sometimes there might be things that we haven’t thought of. Other times it is just a difficult situation that we need to talk about. Participant 6, female, counsellor

All participants underlined the importance of keeping the information shared with them by young migrants confidential. Consent could be sought to share information within a designated team. In the absence of consent anonymity must be maintained if there was a need to discuss the case with colleagues.

Support from their organisations was perceived as more mixed. Some participants expressed that they felt very supported. Others felt that their organisations questioned their work with young migrants or that it was largely invisible and not prioritised.

Wishing they could do more

Many participants felt that although they were able to help young migrants with specific services, their needs and vulnerabilities were so great that they were often left wishing that they could have done more. Concretely, they mentioned wanting training to be better able to address sexual violence. They also felt their organisation should recruit more staff to be able to reach more vulnerable young migrants. They also mentioned lacking sufficient and/or dependable funding.

Central to this category were the feelings of powerlessness to address the root causes of vulnerability, of not always being able to follow up young migrants and know what has happened to them, and the knowledge that in many cases they are unable to access the help they need.

I often find myself in these situations where I feel powerless. There are things I can do but the structures and systems that cause the vulnerability I can try to fight but I am powerless… I feel shame for being a part of this system that creates this inequality and vulnerability. Participant 8, female, counsellor.

Several participants felt very strongly that young migrants’ vulnerability to sexual violence was a betrayal by the social welfare state. They felt powerless and frustrated trying to support a group of people who were in great need but who are largely and increasingly excluded from mainstream services. Many also shared that the current political climate was further restricting support that could be provided.

It (sexual violence) is also structural; there is something violent in betraying children and young people in the way we have in the welfare state. Not that the Migration Agency or social workers are abusive but the structure that puts people in situations where they can be exploited, that is the problem. Participant 4, female, counsellor.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study conducted in Sweden exploring experiences of disclosure of sexual violence by young migrants among a wide range of public sector and civil society professionals. The overarching theme of the study, ‘coming across the hidden problem of sexual violence in an excluded population’, reflects participants perceptions that many cases of sexual violence are never disclosed (the ‘hidden problem’) and that those that are ‘come up’ in the context of meeting other needs. Findings suggest that professionals feel pride in their work providing critical services to vulnerable young migrants that often do not have other options. However, they also often feel that they are providing these services in a context that does not value or recognise their work (Gabrielsson, Karim, and Looi Citation2022; Ouis Citationforthcoming). In addition, the political climate and broader social discourse in Sweden are currently moving towards openly opposing work with migrant groups (Civil Rights Defenders Citation2022).

Previous studies from Europe and internationally have identified migrants as being especially vulnerable to sexual violence, particularly asylum seekers, refugees, undocumented migrants (De Schrijver et al. Citation2018) and unaccompanied migrant children and young people (Mason-Jones and Nicholson Citation2018). There is increasing recognition of the interaction between migrant legal status, living conditions and sexual violence in receiving countries (Keygnaert et al. Citation2015). This notion is supported by how the professionals interviewed in this study understood young migrants’ vulnerability to sexual violence, reflected in the theme ‘linking structural marginalisation and vulnerability to sexual violence’. They described how different groups of young migrants have access to different services depending on their residency status, age, who they are, where they live, and even who they met when trying to access services—and that it is this structural marginalisation that contributes to their vulnerability to sexual violence. It was also found that some migrant groups are not able to access formal social welfare institutions and rely exclusively on support from civil society. This was found previously by van den Ameele et al. (Citation2013) in relation to transmigrants and by Ouis (Citation2021) in relation to young migrants.

It is this combination of exclusion and vulnerability that contributes to the increased risk of exposure to sexual violence and which lies at the root of the more complex vulnerability faced by young migrants (Jahanmahan, Nunez Borgman, and Darvishpour Citation2019). Even when granted asylum, young migrants gain access to the same rights as Swedish young people but live under worse conditions. They tend to have lower socioeconomic status, live in segregated neighbourhoods, are exposed to discrimination, have poorer mental health and higher levels of drug use, and in the case of unaccompanied youth, lack the support of parents or guardians (Klöfvermark and Manhica Citation2019). Addressing these complex vulnerabilities was perceived by many professionals as their role and responsibility in relation to the young migrants they met and was reflected in the theme ‘realising that sexual violence is one among many other concerns’. As many young migrants exist outside of the mainstream social welfare system partnerships between organisations and even individuals in different organisations were seen as critical for trying to meet those needs. However, this reliance on specific individuals for accessing support was perceived as a key challenge leading to a lack of predictability about what services and support may be available, as documented in other research in Sweden (Ouis Citationforthcoming).

In this study, all disclosures of sexual violence occurred in the context of seeking support for something else, and disclosing sexual violence was not perceived by the professionals as the reason for the meetings. Participants felt that many of the experiences of sexual violence shared with them by migrant youth were terrible but that they often were not the worst thing that the young person concerned was going through, nor the biggest problem that they faced. This highlights the incredible vulnerability of these young migrants, since an experience of sexual violence was not necessarily considered an urgent issue, but rather the result of a context that had enabled it.

Previous studies have found different legal and policy barriers to migrants’ access to different rights and services (Keygnaert and Guieu Citation2015), and this was supported by this study as well. Professionals’ awareness of the complex vulnerability of young migrants and their lack of options for accessing different services contributed to the strong sense of personal responsibility for trying to meet their needs. This is reflected in the theme ‘taking pride in backing up young people betrayed by society’. In addition, the need to create individual solutions to meet the specific needs of each young migrant increases the autonomy and power of the professional but also the pressure on them to make the ‘right decision’ about what to do or whom to contact. This could be described as an ethical dilemma leading to moral distress which refers to the dissonance between what is morally right and what one can do, or the dissonance in situations where there may be two competing right courses of action (Gabrielsson, Karim, and Looi Citation2022; Ouis Citationforthcoming). Professionals highlighted the importance of both external supervision and peer support to navigate these tensions but also the need to professionally anchor decisions. This may be enhanced in the context of sexual violence as there is a lack of clarity in terms of what to do in response to the disclosure of sexual violence and a lack of shared understanding of who is responsible for addressing it.

Implications and practical recommendations

This study suggests that professionals perceive young migrants’ vulnerability to sexual violence to be largely structural and a function of their marginalised position in society. The feeling is that addressing this would require major structural change at legal and policy levels at a ment when current trends in Sweden are moving towards curtailing access to rights and services for migrants (Civil Rights Defenders Citation2022). In this context it is important to provide more support for professionals providing services to young migrants and in particular to be aware of the ethically difficult choices that they have to make and encourage an openness and awareness within the organisations to manage them. The development of guidelines for how to deal with disclosures of sexual violence could also be helpful to bolster professionals in their determinations of next steps. In addition, formalising the relationship between organisations providing different types of support and making them more predictable and less based on individual relationships could help in easing some of the responsibility felt by individual professionals. Improving support to professionals providing services to young migrants could in turn facilitate the work that they do supporting vulnerable young migrants with experiences of sexual violence and improve their outcomes.

Methodological considerations

The study has several strengths. It employed maximum variation sampling to understand how professionals from the public sector and civil society experience young migrants’ disclosures of sexual violence. Thus, it represents a range of professionals working in different types of organisations providing different services and included persons of different ages, genders and ethnic backgrounds. Other strengths were that all data obtained were included in the analysis and that the analytical process involved consensus, accomplished through feedback from all co-authors. Credibility was enhanced by conducting member checks of the preliminary results with three interview participants (one from the public sector and two from civil society). Dependability was enhanced through the use of a thematic interview guide based on previous research in the field and aims of the study. Detailed description of the study methodology and analysis contributes to the confirmability. The transferability of these results to other similar settings—in Sweden at least—is deemed to be good.

A potential limitation is the possible power differential between interviewer and interviewee. However, as all participants were professionals sharing their experiences as experts in their own fields, any effect that this might have had was minimised. Another potential limitation was the use of video and telephone interviews. However, recent studies suggest that these can be of comparable quality to in-person interviews and appropriate for facilitating participation (Janghorban, Latifnejad Roudsari and Taghipour Citation2014).

Conclusion

Professionals meeting young migrants with experiences of sexual violence feel responsibility to meet the many and varied needs that they perceive contribute to the young migrants’ vulnerabilities. The perception is that this structural vulnerability is likely to increase given the current political climate and, because of this, the role of these services providers will become even more as will the pressure on them. There is a need to strengthen and support professionals who encounter young migrant victims of sexual violence in their work. Such support includes recognition of the ethical issues involved and the establishment of more formal connections between organisations and service providers to make access to services more predictable.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ahrens, C. E., R. Campbell, N. K. Ternier-Thames, S. M. Wasco, and T. Sefl. 2007. “Deciding Whom to Tell: Expectations and Outcomes of Rape Survivors’ First Disclosures.” Psychology of Women Quarterly 31 (1): 38–49. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2007.00329.x

- Basile, K. C., and S. G. Smith. 2011. “Sexual Violence Victimization of Women: Prevalence, Characteristics, and the Role of Public Health and Prevention.” American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine 5 (5): 407–417. https://doi.org/10.1177/1559827611409512

- Bentivegna, F., and P. Patalay. 2022. “The Impact of Sexual Violence in Mid-Adolescence on Mental Health: A UK Population-Based Longitudinal Study.” The Lancet. Psychiatry 9 (11): 874–883. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(22)00271-1

- Carlsson, F., J. Merlo, M. Lindström, P. O. Östergren, and T. Lithman. 2006. “Representativity of a Postal Public Health Questionnaire Survey in Sweden, with Special Reference to Ethnic Differences in Participation.” Scandinavian Journal of Public Health 34 (2): 132–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/14034940510032284

- Chynoweth, S. K., J. Freccero, and H. Touquet. 2017. “Sexual Violence Against Men and Boys in Conflict and Forced Displacement: Implications for the Health Sector.” Reproductive Health Matters 25 (51): 90–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/09688080.2017.1401895

- Civil Rights Defenders. 2022. “Our Review of the Tidö Agreement.” Accessed 29 November 2022. https://crd.org/2022/10/24/our-review-of-the-tido-agreement-tidoavtalet.

- De Schrijver, L., T. Vander Beken, B. Krahé, and I. Keygnaert. 2018. “Prevalence of Sexual Violence in Migrants, Applicants for International Protection, and Refugees in Europe: A Critical Interpretive Synthesis of the Evidence.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15 (9): 1979. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15091979

- Folkhälsomyndigheten. 2020. Migration, Sexuell Hälsa och Hiv- och STI-Prevention: En Kartläggning av Unga Migranters SRHR i Sverige [Migration Sexual Health and HIV and STI Prevention: Mapping Young Migrants’ SRHR in Sweden]. In Stockholm: Folkhälsomyndigheten.

- Gabrielsson, S., H. Karim, and G.-M E. Looi. 2022. “Learning Your Limits: Nurses’ Experiences of Caring for Young Unaccompanied Refugees in a Acute Psychiatric Care.” International Journal of Mental Health Nursing 31 (2): 369–378. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12965

- Graneheim, U. H., B. M. Lindgren, and B. Lundman. 2017. “Methodological Challenges in Qualitative Content Analysis: A Discussion Paper.” Nurse Education Today 56: 29–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2017.06.002

- Graneheim, U. H., and B. Lundman. 2004. “Qualitative Content Analysis in Nursing Research: Concepts, Procedures and Measures to Achieve Trustworthiness.” Nurse Education Today 24 (2): 105–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001

- Jahanmahan, F., N. Nunez Borgman, and M. Darvishpour. 2019. “‘Vi Dör Hellre i Sverige Än i Afghanistan!’ - Att Få Uppehållstillstånd Eller Leva Papperslöst i Sverige” [‘We’d rather Die in Sweden Than in Afghanistan’ - Gaining Residence Permits or Living Undocumented in Sweden]. In Ensamkommandes Upplevelser och Professionellas Erfarenheter: Integration, Inkludering och Jämställdhet [Unaccompanied Children’s and Professionals’ Experiences: Integration, Inclusion and Equality], edited by M. Darvishpour and S. A. Månsson, 120–135. Stockholm: Liber.

- Janghorban, R., R. Latifnejad Roudsari, and A. Taghipour. 2014. “Skype Interviewing: The New Generation of Online Synchronous Interview in Qualitative Research.” International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being 9 (1): 24152. https://doi.org/10.3402/qhw.v9.24152

- Keygnaert, I., S. F. Dias, O. Degomme, W. Devillé, P. Kennedy, A. Kováts, S. De Meyer, N. Vettenburg, K. Roelens, and M. Temmerman. 2015. “Sexual and Gender-Based Violence in the European Asylum and Reception Sector: A Perpetuum Mobile?” European Journal of Public Health 25 (1): 90–96. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/cku066

- Keygnaert, I., and A. Guieu. 2015. “What the Eye Does Not See: A Critical Interpretive Synthesis of European Union Policies Addresssing Sexual Violence in Vulnerable Migrants.” Reproductive Health Matters 23 (46): 45–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rhm.2015.11.002

- Klöfvermark, J., and H. Manhica. 2019. “Unga Flyktingar i Sverige: Psykisk Ohälsa och Missbruksproblem” [Young Refugees in Sweden: Poor Mental Health and Substance Abuse Problems]. In Ensamkommandes Upplevelser och Professionellas Erfarenheter: Integration, Inkludering och Jämställdhet [Unaccompanied Children’s and Professionals Experiences: Integration, Inclusion and Equality], edited by M. Darvishpour and S. A. Månsson, 43–58. Stockholm: Liber.

- Malterud, K., V. D. Siersma, and A. D. Guassora. 2016. “Sample Size in Qualitative Interview Studies: Guided by Information Power.” Qualitative Health Research 26 (13): 1753–1760. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732315617444

- Mason-Jones, A. J., and P. Nicholson. 2018. “Structural Violence and Marginalisation. The Sexual and Reproductive Health Experiences of Separated Young People on the Move. A Rapid Review with Relevance to the European Humanitarian Crisis.” Public Health 158: 156–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2018.03.009

- OECD. 2016. Promoting Well-Being and Inclusiveness in Sweden. Paris: OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264259980-en

- Oliffe, J. L., M. T. Kelly, G. Gonzalez Montaner, and W. F. Yu Ko. 2021. “Zoom Interviews: Benefits and Concessions.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 20: 160940692110535. https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069211053522

- Ouis, P. 2021. “Migrationslagstiftining, Transnationella Relationer och Sexuell Riskutsatthet” [Migration Laws, Transnational Relationships and Sexual Vulnerability]. In Sexualitet och Migration i Välfärdsarbete [Sexuality and Migration in Social Work], edited by P. Ouis, 265–291. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Ouis, P. forthcoming. “Professionellas Beredskap, Erfarenheter och Tolkningar av Sexuellt Våld Bland Unga i en Migrationsprocess” [Professionals Preparedness, Experiences and Understandings of Sexual Violence in Youth in a Migration Process]. In Perspektiv på Sexualitet i Socialt Arbete [Perspectives on Sexuality in Social Work], edited by C. Holmström, A. de Cabo, and P. Ouis. Stockholm: Liber.

- SCB. 2022. “Utrikes Födda i Sverige” [Foreign-Born Persons in Sweden]. Accessed 20 December 2022. https://www.scb.se/hitta-statistik/sverige-i-siffror/manniskorna-i-sverige/utrikes-fodda/

- Law 2013:407. 2013. Om Hälso- och Sjukvård till Vissa Utlänningar som Vistas i Sverige Utan Nödvändiga Tillstånd” [On Healthcare Services for Certain Foreigners Residing in Sweden Without the Required Permits]. https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-och-lagar/dokument/svensk-forfattningssamling/lag-2013407-om-halso-och-sjukvard-till-vissa_sfs-2013-407/

- Law 2016:752. 2016. Om Tillfälliga Begräsningar av Möjligheten att Få Uppehållstillstånd i Sverige [On Temporary Limitations on the Possibility of Getting Residency Permits in Sweden]”. https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-och-lagar/dokument/svensk-forfattningssamling/lag-2016752-om-tillfalliga-begransningar-av_sfs-2016-752/

- Ullman, S. E., E. O’Callaghan, V. Shepp, and C. Harris. 2020. “Reasons for and Experiences of Sexual Assault Non-Disclosure in a Diverse Community Sample.” Journal of Family Violence 35 (8): 839–851. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-020-00141-9

- van den Ameele, S., I. Keygnaert, A. Rachidi, K. Roelens, and M. Temmerman. 2013. “The Role of the Healthcare Sector in the Prevention of Sexual Violence Against Sub-Saharan Transmigrants in Morocco: A Study of Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices of Healthcare Workers.” BMC Health Services Research 13: 77. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-13-77

- WHO (World Health Organization). 2002. World Report on Violence and Health. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- WHO (World Health Organization). 2011. Violence Against Women: Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Against Women. Geneva: World Health Organization.