Abstract

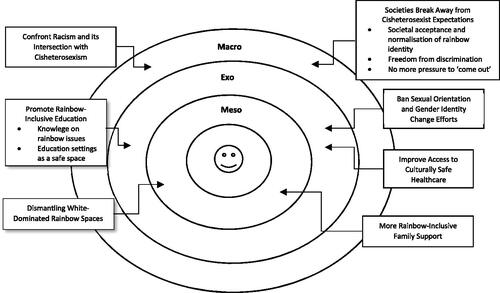

Rainbow research tends to prioritise gender and sexuality experiences over the racialised experiences of Asian rainbow young people. Informed by an intersectional lens, we employed a hope-based ecological framework to examine how multiple overlapping axes of oppression (e.g. cisgenderism, heterosexism and racism) shape the aspirations of these youth. We drew on the voices of Asian participants from the 2021 Aotearoa New Zealand Identify Survey, who had responded to an open-text question on their hopes for rainbow young people (n = 217; age range = 14 to 26). The content analysis identified seven prominent categories of hope across three ecological levels (macro exo and meso). These categories were societies: 1) break away from cisheterosexist expectations; 2) confront racism and intersection with cisheterosexism; 3) promote rainbow-inclusive education; 4) ban sexual orientation and gender identity change efforts; 5) improve access to culturally safe health care; 6) dismantle white-dominated rainbow spaces; and 7) provide more rainbow-inclusive family support. These hopes were constructed amidst the desire to challenge unacceptance and exclusion by the wider society for not adhering to white cisheterosexist expectations. The study provides critical insights for community organisations, education settings, and government to consider in addressing the diverse needs of Asian rainbow young people.

Introduction

The most recent population-based Household Economic Survey conducted in 2020 found that 4.2% of adults in Aotearoa New Zealand are ‘rainbow’Footnote1 (Statistics New Zealand 2021). The proportion of rainbow young people may be higher as the Aotearoa Youth’19 survey estimated that 12% of secondary school students had a rainbow identity (Roy et al. Citation2020). This proportion includes people whose gender identity differs from their sex assigned at birth or who are unsure of their gender identity; attracted to the same sex or were attracted to both men and women, or multiple sexes; although, it is unclear how many of them identified with an AsianFootnote2 ethnicity. Our use of the term rainbow also includes people with culturally specific identities such as Chinese tongzhi and Indian hijra. In this paper, the objective of using the term ‘Asian rainbow young people’ is to mobilise political solidarity amongst minoritised young people who experience multiple forms of marginalisation and oppression such as cisheterosexism, racism, ageism and the pressures of acculturation.

Background

Internationally, while there is a growing research on rainbow youth in Asia (e.g. Tan and Saw Citation2022; Wandrekar and Nigudkar Citation2020), few studies are available on Asian rainbow young people living as a minoritised group in a non-Asian country. The unique colonial history and religious influence that can be found in Asia, as well as Asian cultural values, are often dismissed in the mainstream rainbow literature (Tan and Saw Citation2022). Asian collectivist values emphasise avoiding confrontation with others (especially with the elderly) to preserve a harmonious interpersonal relationship and fulfil familial commitments, marriage roles, and the duty to carry on the family bloodline (Ching et al. Citation2018; Mao, Mccormick, and Van de Ven Citation2002). Identifying as a rainbow person can be seen as diminishing one’s public reputation, described as ‘face’ in East Asian contexts (Dam Citation2023), and ‘honour’ in South Asian contexts (Bal and Divakalala Citation2022), as well as tarnishing the reputation of the family, for deviating from the cisheteronormative expectations present in broader Asian communities.

The experiences of Asian rainbow young people continue to be subsumed within studies that have predominantly recruited European participants, despite Asian scholars (Hahm and Adkins Citation2009; Mao, Mccormick, and Van de Ven Citation2002; Tan and Weisbart Citation2022) alluding to the peril of viewing Asian rainbow experiences through a ‘western’ lens. One such example is the deficit-based assumption that ‘coming out’ or disclosing one’s rainbow identity is the normative end-goal for all rainbow youth to live their authentic selves. Such a perspective takes away the agency that Asian rainbow young people have and undermines the importance of collectivist values in influencing their decisions whether or not to openly disclose their rainbow identity (Amerasinghe 2018; Nakhid, Yachinta, et al. Citation2022). The decision to not come out is ‘an act of selflessness and care, a considered decision’ (Nakhid, Yachinta, et al. Citation2022, 300) which constitutes a more common (as well as strengths-based) narrative for young people who prioritise the maintenance of harmonious familial relationships and kinship.

Studies from Aotearoa provide evidence of mental health inequities for those who live at the intersection of being Asian and rainbow. The representative Youth’12 study in Aotearoa found higher rates of depression and suicide attempts for ARYP relative to their Asian cisgender and heterosexual counterparts (Chiang et al. Citation2017). The disparities in depression and suicidal rates become more prominent compared to Pākehā cisgender and heterosexual students (Chiang et al. 2017). Heightened rates of mental health issues may be related to the cisheterosexism which exposes rainbow young people to minority stressors such as societal discrimination and family rejection (Tan and Saw Citation2022). Cisheterosexism is underpinned by the assumption that there are only two valid genders (man and woman) and that people only engage in heterosexual relationships. Cisheterosexism privileges those who conform to the normative gender and sexual identities and marginalises others, with negative repercussions (e.g. discrimination, misgendering and pathologisation) (Fenaughty et al. Citation2022; Ellis, Riggs, and Peel Citation2019).

Although not specifically centred on youth, two studies have dexamine the discriminatory experiences faced by Asian rainbow individuals in Aotearoa. The 2018 Aotearoa Counting Ourselves study found that of Asian transgender people (n = 49), two-fifths of Asian participants had experienced discrimination due to their transgender or nonbinary identity (42%) or race or ethnicity (39%) (Tan, Yee, and Veale Citation2022). Asian transgender participants were approximately six times more likely to feel discriminated against for their ethnicity relative to the overall survey cohort (39% vs. 7%) (Tan, Yee, and Veale Citation2022). Apart from the respective minority stressors associated with being rainbow, as well as Asian, Asian rainbow young people encounter specific stressors as a function of their intersectional identities that vary in different contexts (Tan and Weisbart Citation2022). The Adhikaar project that undertook community consultations with 43 South Asian rainbow individuals illustrated the impact of cisheteronormative white-centric norms that create a dissonance between South Asian rainbow individuals and their sense of grounding in a ‘world that was not made for them’ (Bal and Divakalala Citation2022, 13). Despite the systemic struggles that Asian rainbow young people experience, there are pockets of small (but powerful) hopes as this group engages in advocacy, build community solidarity, and take on responsibility to make lived realities visible (Bal and Divakalala Citation2022).

Theoretical framework

Hope theory defines ‘hope’ as a positive motivational state in pursuing goals (Snyder Citation2002). Goals may reflect aspiration envisioned, the desire to further a goal in progress that has been made, or the wish to forestall negative outcomes (Snyder Citation2002). Grounded in future-oriented thinking, research with rainbow participants points to the benefits of hopefulness in healthy rainbow identity development (Moe, Dupuy, and Laux Citation2008) and the prevention of mental ill-health and suicidality (Moe et al. Citation2023). However, research on hope largely focuses on individual cognitive and psychological contexts with less attention paid to the contextual aspects of hope (Moe et al. Citation2023; Yohani Citation2008). Informed by a socioecological model, a few studies have explored hope as an ecological phenomenon formed and influenced over time by the complex interaction of inter- and intra-individual factors (Institute of Medicine Citation2011; Yohani Citation2008). In this study, we employ a hope ecological framework to examine the formation of hope across three system levels: interpersonal (meso), contextual or community (exo), and structural (macro) (Clark and Stubbeman Citation2021; Yohani Citation2008).

Where research focuses on the experiences of multiple important aspects of one’s identity, an intersectional theory is often used to explain the nuances of oppression and privilege (Wesp et al. Citation2019). Intersectionality is a critical methodology originally conceptualised to consider Black women’s unique experiences of sexist and racist oppression (Crenshaw Citation1989). Intersectionality research is informed by a social justice agenda to uncover the operation of oppression and how minoritised groups such as Asian rainbow young people resist unjust social processes (Rice, Harrison, and Friedman Citation2019; Wesp et al. Citation2019). The Intersectionality Research for Health Justice framework (Wesp et al. Citation2019) outlines three actions that could be used to advance a rainbow justice agenda for research: naming the intersecting power relations that produce inequities; identifying the structural production of inequities to disrupt the status quo; and centring embodied knowledge of those at the margins of society. By inserting an intersectionality analysis within a hope ecology framework we hoped to identify the role of multiple (interconnected) systems that facilitate the developmental trajectory of hope for Asian rainbow young people alongside structures that sustain the effects of intersectional oppression (Institute of Medicine Citation2011).

A scant amount of intersectionality-guided literature exists to examine the construction of hope for Asian rainbow young people in Aotearoa. To address this literature gap, as well as concern that psychological framings of hope may inadvertently obscure broader oppressive structures, we used an ecological lens to explore the hopes of Asian participants as revealed in the Identify Survey (the largest study of rainbow youth in Aotearoa to date). The analysis was designed to understand how the futures that Asian rainbow young people imagine are shaped by processes of differentiation (e.g. racialisation and gendering) across the ecology of their lives, with a focus on centring their experiences.

Methods

The data were derived from the Identify Survey, a nationwide study in Aotearoa that collected comprehensive data on the strengths and challenges reported by rainbow young people across key domains of their lives. The survey was developed as a collaboration between rainbow community researchers and organisations and recruited 4,784 rainbow participants aged 14 to 26 between February and August 2021 (Fenaughty et al. Citation2022). Participants were recruited in the political context of the New Zealand Government debating the Conversion Practices Prohibition Legislation Bill (banning of sexual orientation and gender identity change efforts) and the Births, Deaths, Marriages and Relationships Registration Act (the removal of proof of medical transition to change the gender marker on one’s birth certificate); both Bills were passed in 2022.

Purposive sampling strategies were used both in-person (e.g. at community events and meetings) and online (e.g. via advertisements and posts on Facebook and Instagram). Some of the online advertisements specifically invited racialised rainbow youth, whose voices are often under-represented. Overall, 526 participants identified with an Asian ethnicity (including Chinese, Indian, Filipino, Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese and others); of these, 217 provided a response to the open-text question: ‘What are your hopes for rainbow young people in Aotearoa New Zealand in the future?’. Appendix 1 presents the demographic characteristics of the analytic sample (n = 217; Mage = 18.54). The Identify Survey received ethical approval from the New Zealand Health and Disability Ethics Committee (20/NTB/276).

Data analysis

Open-text responses were analysed using conventional content analysis, an inductive approach to identifying patterned categories (Hsieh and Shannon Citation2005). The analytic process began with the lead researcher (KT), with lived experiences as an Asian rainbow young person, familiarising himself with the content to achieve immersion. Next, each quote was carefully read and labelled with code(s) to capture the essence of the text. An individual response could contribute to more than one code if the quote touched on several issues. The coding phase was recursive rather than linear, as KT regularly consulted with other authors to check the evolving analysis against the dataset. The codes were then organised into categories and subcategories based on similar contents and meanings. All the authors were then involved in the selection of participant quotes that best exemplified each category to put into the narrative summary of the results. Information on ethnicity was provided for each exemplar but not the other details as it could risk leading to deductive disclosure. Although some participants only wrote short phrases or sentences that lacked context and conceptual richness, many participants provided sufficient details of their experiences and perspectives.

Using IBM SPSS v28, we conducted Chi-square goodness-of-fit (χ2) tests to determine whether there were any associations between the observed and expected frequency distributions for demographic variables (age, ethnicity, gender, sexuality and region) amongst participants who chose to leave a qualitative comment (see Appendix 1). No statistically significant differences were detected across age groups, ethnicities, gender groups and regions, except that we found participants who identified their sexual identity as ‘queer’ were more likely to provide a response.

Findings

Findings were organised under seven overarching categories to identify the different aspects of Asian rainbow young peoples’ experiences and aspirations for other rainbow young people (see ). Asian rainbow young people identified factors across three distinct and interconnected ecological systems as relevant to their construction of hope: the macrosystem, the exosystem, and the mesosystem.

Macrosystem

The macrosystem refers to the broader social structures and norms that structure and police the social environments Asian rainbow young people live in.

Societies break away from cisheterosexist expectations

Cisheterosexism alienates Asian rainbow young people by disrupting their sense of belonging in a society that privileges cisgender and heterosexual people, exposes them to minority stressors (e.g. discrimination and rejection) and may compel some to live a ‘closeted’ life.

Societal acceptance and normalisation of rainbow identity

One participant (Samoan, Chinese and Indian) spoke about the experience of being at the margins of society, which hindered their sense of belonging: ‘My hope is that everyone in the rainbow whanau feel like they belong’. It was apparent that participants felt ‘othered’ through the pressure to conform to cisgender and heterosexual norms alongside the need to constantly justify their rainbow identities:

I hope that we can recognise how society at large is and has been shaped against rainbow people, and I hope that we can change things to be more welcoming and accepting at all levels of society. I would like a world in which our identities aren’t a debate, but are understood simply as a fact of life. (Indian and Pākehā)

I hope that young people can be able freely express themselves and be proud of their sexualities without having to face the negativities of homophobia that come from their elders/parents/religion. (Filipino)

Freedom from discrimination

In addition to the normalisation of their rainbow identities, for some participants just being free from active cisheterosexist discrimination represented a key hope for them. For some, this discrimination included judgement and harassment concerning their identity:

I just hope that we can all express ourselves without judgement and harassment. I don’t want to hide anymore, and I am sure that many others are having the same feeling as I am. I hope there will be more and more progressive and inclusive change for all rainbow young people in Aotearoa NZ, so our future generation can grow up in a more accepting community! (Vietnamese)

I would like to be able to display affection towards a partner or friend without being publicly berated, or attacked for being who I am. Because this is a little bit of a fear of mine, being put down for something I cannot change. (Korean)

I hope that people in same sex relationships are able to freely show their love without people staring and making rude comments, as well as those of the transgender community being able to freely express their identity. (Chinese and Māori)

No more pressure to ‘come out’

Participants challenged the notion of not having to ‘come out’ as a form of privilege that cisgender and heterosexual people possess. The need to ‘come out’ in order to challenge cisheterosexist assumptions (i.e. that everyone is cisgender and heterosexual) was a disempowering process as it continued to buttress the power inequity between rainbow and non-rainbow populations. For example, one participant (Pakistani and Pākehā) shared, ‘I hope that in general, diverse sexualities and genders will be normalised so we won’t have to ‘come out’ the same way cishet people don’t.’ Coming out was described as an intimidating process as one participant (Filipino) hoped, ‘That coming out doesn’t have to be so scary and everyone gets along with us’. Others similarly wished that there were no expectations to ‘come out’, as one participant (Chinese) hoped ‘that one day, the concept of closeting and coming out won’t apply to us anymore’.

Confront racism and its intersection with cisheterosexism

Creating an inclusive society for Asian rainbow young people requires recognising intersecting systems of oppression and acknowledging that individuals may experience discrimination on multiple fronts. One participant (Indian) desired, ‘that we can be safe, be proud, be seen as “norma”. That no rainbow young person is ever discriminated against (for sexuality, gender, disability, race, etc)’.

The two quotations below demonstrate some of the additional challenges ARYP are more likely to experience (compared to their Pākehā counterparts); these include racism and discrimination from society and pressure to forgo one’s cultural identity so as to fulfil ‘western’ expectations.

To be able to express rainbow identities without fear of being discriminated. Ethnic-minority rainbow young people experience additional discriminations due to their ethnicity and there’s a strong need to acknowledge this! (Southeast Asian Chinese)

There will be better representation for queer BIPOC [Black, Indigenous, People of Colour] because although we face discrimination and oppression based on our sexuality and/or gender identity, it is easier for society as a whole to accept you if you fit into ‘western’ ideals. (Cambodian Chinese)

Participants faced specific barriers that are often overlooked in conversations about strengthening support for rainbow communities. One participant (Indian) hoped that there could be ‘Ethnic LGBT+ support especially for migrants.’ Support services for Asian rainbow young people ought to account for issues commonly affecting migrants such as low English language proficiency, lack of awareness of services, difficulty accessing culturally appropriate healthcare, and housing instability (Wong Citation2021).

Exosystem

Within the exosystem, organisations and social systems impact individuals without their active participation, as the relevance of legal structures, education systems and health care delineates below.

Ban sexual orientation and gender identity change efforts (SOGICE)

Participants called for Government intervention to criminalise practices that seek to change or suppress sexual orientation and gender identity. Participants expressed fear of living in a country where cisheterosexism can be disguised as a form of therapy to ‘treat’ rainbow identities.

Conversion therapy, in all its forms, [should be] banned. (Punjabi and Pākehā)

I want every queer kid who’s like me to be assured that they won’t be sent to conversion therapy, that if their environment becomes dangerous they’ve got somewhere to go. (Southeast Asian Chinese)

Change efforts that attempt to alter or suppress rainbow identity have detrimental mental health consequences for young rainbow people (Fenaughty et al. Citation2023), and such practices were outlawed by the New Zealand Government in February 2022.

Promote Rainbow-Inclusive education

The pervasive culture of cisheterosexism within educational environments as reflected in policies, curricula and staff members’ attitudes, can contribute to social exclusion. Participants suggested that education should be the starting point to normalise rainbow identities and address cisheterosexism in society, and schools have an essential role to play in instigating change.

Expand knowledge on rainbow issues

The expansion of education about rainbow identities, relationships and issues (e.g. minority stressors) was deemed by participants as key to the inclusion of rainbow people in the general society. However, comments demonstrated that such contents are often not meaningfully included in the school curriculum (and maybe silo-ed into sexuality education) or are offered on an optional basis.

I hope that we mandate rainbow education in schools to further a society that truly embraces rainbow people. (Japanese and Pākehā)

I hope that in-school education about LGBTQIA + identities and issues will be as compulsory/as comprehensive as heterosexual sex education. (Chinese)

Increased knowledge of rainbow issues was not confined to students but was seen as also relevant to educators. Participants in the study described sometimes being tasked with the additional labour of having to educate someone else about rainbow experiences. For example, one participant (Chinese) wished there could be ‘further education on LGBT + people so cisgender and heterosexual people can be more educated without needing to put young rainbow people in the sole position of educating another when they don’t want to.’

Make education settings safe spaces

Schools, polytechnics and universities can also serve as institutions that perpetuate cisheterosexism. Participants provided examples of the discriminatory language used by schools’ leadership teams, barriers to filing complaints about bullying, and lack of genuine follow-up for victimised rainbow students. One participant (Cambodian Chinese) hoped that:

Schools will have more education on the rainbow community and being able to celebrate our culture and success without anyone feeling unsafe because of their gender identity and/or sexuality, as well as the hope for a better understanding of our community within a heteronormative society. I also wish for schools to get rid of gendered language because it’s unnecessary and just causes rifts.

Schools actually doing something for queer/trans kids that get bullied, child abuse being taken seriously. (Indian)

I hope that we can make schools safer and better. Actually better, not just doing things to look like they’re doing something. Putting in the hard yards to protect queer kids. Informing teachers of what to do and say. Actually educating us students about queer history, for a change. I just want us to feel like we belong. (Southeast Asian Chinese)

Improve access to culturally safe healthcare

Despite the high mental health needs due to distress resulting from minority stressors (Le et al. Citation2022), participants reported difficulties in accessing healthcare that was timely, culturally safe, low cost, and convenient to their location.

I also hope mental health services will be better and more accessible, especially for rainbow people as I’ve seen so many of my friends struggle with mental health due to homophobic and transphobic people. (Indian and Pākehā)

Participants also experienced high levels of unmet need for gender-affirming car. This type of care can be difficult to access via the public health system in Aotearoa due to long wait times and inconsistent pathways (Fraser et al. Citation2019). Privately funded access to local and overseas gender-affirming care may be a less viable option for Asian transgender youth, particularly those with limited finance.

I hope the support that we need can become more genuine and less tokenistic. I am talking about mental health providers learning and respecting diverse sexualities, a dedicated service for rainbow youth estranged from families and easier and cheaper access to gender affirming health care. (Indian)

I hope people can transition without medical gatekeeping, and that trans surgeries are all covered under healthcare. (Vietnamese)

Mesosystem

The mesosystem comprises settings or contexts that an individual is a part of. Participants identified families and rainbow communities as networks of relationships that are crucial to formation of hope.

Have more Rainbow-Inclusive family support

Family acceptance of rainbow identity was not something to be taken for granted. Participants described the complicated situation that they often had with family members, including family rejection, family refusal to acknowledge rainbow identity, and limited understanding of gender and sexuality diversity.

I hope that in the future, rainbow youth will not have to experience the pain and trauma of simply expressing their identity that my friends and I myself have experienced. It frustrates me to know that I have to hide to keep my parents happy, that I have to lie to them about my relationship with my partner just to keep them happy. (Chinese)

I hope my parents don’t push me so much to get married fast as I find it hard to establish romantic relationships due to not feeling sexual and romantic desire. I hope they respect asexuality as an identity and allow me to just live how I would like. I would love a platonic partner to be a companion throughout life though, so it’s not like I want to be single forever. (Chinese)

One participant (Southeast Asian Chinese) shared ‘I want people like me to feel loved, to feel accepted, if not by their [birth] family, then by their found family [family of choice].’ The Youth’12 study showed that non-Pākehā (including Māori, Pacific, Chinese, and Indian) rainbow young people did not report higher rates of depression and suicide attempts compared to their Pākehā counterparts (Chiang et al. Citation2017). The findings implied that there may be culturally-specific support networks that Asian rainbow young people seek out to mitigate the effects of minority stressors on the mental health.

Dismantling white-dominated rainbow spaces

Participants raised concerns about the predominantly white, cisgender rainbow spaces that present themselves as seemingly inclusive. As one participant (Sri Lankan) shared,

We can be accepting and loving of one another. I feel as if the rainbow community still holds traits of racism, misogyny and transphobia (ironically). As a POC [Person of Colour] who is part of the younger generation of rainbow group in NZ, I find that there is bias towards white members of the community. I’ve found it incredibly hard to voice my opinions and experiences growing up queer in NZ as a POC - often being diminished by white rainbow members themselves at times. (Sri Lankan)

White-centric rainbow spaces provide exemplars of institutional racism, especially when Indigenous and minoritised ethnic groups (e.g. Asian) are frequently disempowered from taking up leadership positions (Meyer Citation2015). The lack of non-Pākehā representation in rainbow organisations and community events signals the limited consideration given to the voices of diverse ethnic groups. Ethnic identity was described by participants as an aspect of themselves they had to suppress due to the culturally unsafe nature of white rainbow spaces.

To be more racially inclusive and more trans and nonbinary inclusive. It [The rainbow space] is still predominantly cis and white dominated for me to feel entirely comfortable because currently it doesn’t feel like it’s a space I go to feel represented and loved. (Chinese)

I find living in Wellington there is a lot of pride in being queer and nonbinary/trans which is great but a lot of it feels gatekept by Pākehā people. I hope to find more spaces where POC [People of Colour] can feel valid and represented and for me to feel comfortable. (Chinese)

Discussion

The hope ecology framework presented in this paper offers insight into futurity, agency and the expectations of Asian rainbow young people as shaped by the various systems that they are embedded in. A systems-level analysis of their experience is germane for stakeholders at family, community and policy levels to generate solutions that address barriers to participation in different social spheres.

An intersectionality analysis at the macro-level reveals the dominant discourses that reinforce cisgender and heterosexual prejudices and Pākehā (Whiteness) as the unquestioned norm of rainbow representation. Cisheterosexism puts Asian rainbow young people at risk of social exclusion in different spheres of life including unemployment, poverty and limited social connection (Ching et al. Citation2018). Participants discussed the challenges in gaining acceptance from the wider society and coming out to an environment where both ‘rainbow’ and ‘Asian’ identities are minoritised. In a context where assimilation into ‘Western’ society is seen as an indicator of success by some Asian communities, being rainbow was a barrier to this (Nakhid, Tuwe, et al. Citation2022). Thus, most Asian rainbow young people were careful in deciding to whom they could disclose their rainbow identity so that the ties with family, relatives and communities could continue to be maintained (Adams et al. Citation2022; Mao, Mccormick, and Van de Ven Citation2002; Nakhid, Yachinta, et al. Citation2022).

Cisheterosexism was evident in participants’ descriptions of the erasure of their experiences and needs in legal structures, education systems and health care. Different priorities for change were outlined: a ban on change efforts through legislation; the more meaningful integration of rainbow issues into the educational curriculum; the creation of safe spaces at educational institutions (including the establishment of anti-bullying policies); and improved accessibility and degree of cultural safety of general and gender-affirming healthcare. Instead of treating everyone equally regardless of their cultural differences and social backgrounds, service providers working within a culturally safe framework should engage in reflexivity to identify their own biases and blinds spots that may interfere the provider-patient relationship. It is critical for service providers and organisations to create a space in which Asian rainbow young people can articulate their experiences safely (Curtis et al. Citation2019). For Asian families and communities to better understand rainbow cultures, participants recommended more education and resources be provided on destigmatising rainbow identities and supporting Asian rainbow communities. The Rainbow Support Collective (Citation2023) has listed a number of resources about supporting young people who are trans, nonbinary, intersex or rainbow in Aotearoa; however, we are not aware of any specific guidelines for families that consider for the diverse and complex needs of Asian rainbow communities.

Although non-Asian rainbow young people have also shared similar hopes when it comes to enhanced rainbow inclusivity across exosystems (Fenaughty et al. Citation2022), participants specifically urged for increased visibility of Asian rainbow representation as well as better understanding of their needs in settings where they are often rendered invisible. In Aotearoa, Asian communities are subjected to specific forms of racialisation, exemplified by the perpetuation of the ‘model minority myth’ and the ‘perpetual foreigner’ narratives that seek to exclude them from the perceived privileges of ‘white membership’ (Dam Citation2023; Tan Citation2023). The intersection between Asian racialisation experiences and cisheterosexist marginalisation and Asian cultural expectations presents unique challenges for this group, distinguishing them from other minoritised ethnic groups in Aotearoa such as Māori, Pasifika and African communities. In this instance, hope was uttered as an anticipation for more Asian rainbow voices to be heard and more Asian rainbow leadership who participants could relate to, as members of this group navigate a unique terrain of racialisation, cisheterosexist marginalisation, and cultural expectation not shared by others.

The pressure to conform to normative (white cisheterosexist) expectations has a flow on effect for how Asian rainbow young people form interpersonal relationships with families and rainbow communities. Several participants described mainstream rainbow spaces as unwelcoming and alienating and some had to hide certain aspects of their identity to fit into the white cisgender ‘script’ evident in these monocultural environments. Racism towards Asian rainbow communities is often not acknowledged or is actively denied, by some members of rainbow communities who also claim marginality in Aotearoa.

Asian rainbow young people are often left to themselves to handle the additional challenges that cisheterosexism presents, as they may be estranged from other social networks and social support from family members. While family and Asian communities can provide a buffer against the damages caused by racism (Wong Citation2021), receiving support from the family or wider community remained out-of-reach for some participants, and was only something that they could yearn for. While some family members have embraced rainbow cultures following migration and acculturation to Aotearoa, the aforementioned Asian values and colonial histories continue to shape traditional gender and sexual role expectations within Asian communities.

Strengths and limitations

As an online survey, the Identify Survey may have over-recruited ARYP with convenient access to online resources and support. The recruitment may also have benefited from assistance by rainbow community networks so those with fewer connections to rainbow communities were less likely to find out about the survey (Fenaughty et al. Citation2022). The anonymous nature and online delivery of the survey, however, constituted appealing features of research participation for some Asian rainbow young people who may not yet have ‘come out’ or did not wish to disclose their identity to researchers.

Despite often being placed in a single category for the purposes of political solidarity (Dam Citation2023), within-group differences exist for the Asian population (Adams and Neville Citation2020). The risk of bias for participants who chose to provide a qualitative comment is likely to be minimal and we did not detect significant differences between most demographic groups (i.e. age, gender, ethnicity, and region) except for those participants who identified their sexuality as ‘queer’. Queer is increasingly used as a political identity to disrupt hegemonic and dominant discourses of gender and sexuality and queer identifying participants may be particularly motivated to share their stories and experiences to help produce change (Fenaughty et al. Citation2022).

However, the Identify study falls short when considering the diverse backgrounds of different Asian groups in terms of gender, nationality, length of residence, migration status, and religion. Those with limited literacy or English language abilities, or with a background as recent migrants or refugees, have been identified as having the highest need for health and support services (Wong Citation2021). Future research can consider ways to reach out to diverse Asian groups such as partnering with local Asian community organisations and providing options to complete the survey in multiple languages. It is important to note that the low frequency of participants speaking directly about their personal experience of racism and intersectional identities, does not imply that these experiences are less substantial for Asian rainbow young people. The nature of the survey (as a rainbow-specific study) and the questions asked meant that participants received few prompts to share their intersectional identity experiences.

Conclusion

This study draws on a hope ecology framework to explore how Asian rainbow young people’s hopes and aspirations for rainbow young people are regulated by macro-level norms and agents within their exo- and meso-level systems. Findings highlight common hopes, including the strong desire for their identities to be normalised, to live without fear of discrimination, to gain familial acceptance, and for more education on gender and sexuality diversity. In identifying the impacts of whiteness on how Asian rainbow young people hold on to intersecting identities, participants challenged the dominant narrative of there being a homogenous experience of being a rainbow young person as well as racialised narratives that have been forced upon them. Importantly, participants’ hopes for the future imply that several key social domains are culturally unsafe to access due to the pervasive character of whiteness and cisheterosexism, which prevent this group from feeling safe and finding connection. Eliminating barriers to achieve equity for Asian rainbow young people requires engaging with and welcoming Asian rainbow young people as their whole selves, while at the same time being aware of the relationships between Asian values, cisheterosexuality and the impacts of racialisation in modern day Aotearoa New Zealand.

Acknowledgement

The authors are grateful to Identify participants who entrusted us with analysing crucial information about experiences of being a rainbow person in Aotearoa. Thank you to Ryan San Diego for participating in an initial discussion to conceptualise the direction of this paper. Thanks also go to the Ministry for Ethnic Communities (Te Tari Mātāwaka) for funding the first author to present part of the study’s findings at the inaugural Ethnic Advantage Conference in Ōtepoti/Dunedin. Lastly, the authors express our appreciation to the four anonymous reviewers for engaging in robust discussion with us about the theoretical framework and their contribution to refining this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 In Aotearoa, the use of ‘rainbow’ as an umbrella term encompasses people born with intersex variations (e.g. people with genitals, gonads or chromosomal patterns that do not fit typical binary notions of male or female bodies). It is important to not conflate the categories of sex characteristics, gender and sexuality that may lead to the erasure of specific intersex experiences.

2 Te Tiriti o Waitangi has granted the (im)migration of non-Māori (including New Zealand European/Pākehā, Pacific peoples, Asians and other ethnic groups) to settle in Aotearoa since 1840 (Dam Citation2023). Our usage of the term ‘Asian’ follows the Statistics New Zealand (2019) classification that includes diverse populations with genealogical links to East Asia (e.g. Chinese and Japanese), South Asia (e.g. Indian and Bangladeshi) and Southeast Asia (e.g. Filipino and Malaysian).

References

- Adams, J., E. J. Manalastas, R. Coquilla, J. Montayre, and S. Neville. 2022. “Exploring Understandings of Sexuality among “Gay” Migrant Filipinos Living in New Zealand.” SAGE Open 12 (2): 215824402210973. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440221097391

- Adams, J., and S. Neville. 2020. “Exploring Talk about Sexuality and Living Gay Social Lives among Chinese and South Asian Gay and Bisexual Men in Auckland, New Zealand.” Ethnicity & Health 25 (4): 508–524. https://doi.org/10.1080/13557858.2018.1439893

- Amerasinghe, D. 2018. “Coming out’ of the Asian Closet: The Intersectional Experiences of LGBTQ + Asians in New Zealand.” Masters’ thesis, University of Auckland.

- Bal, V., and C. Divakalala. 2022. “Community is Where the Knowledge is: The Adhikaar Report.” https://www.adhikaaraotearoa.co.nz/the-adhikaar-report/

- Chiang, S.-Y., T. Fleming, M. Lucassen, J. Fenaughty, T. Clark, and S. Denny. 2017. “Mental Health Status of Double minority Adolescents: Findings from National Cross-sectional Health Surveys.” Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 19 (3): 499–510. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-016-0530-z

- Ching, T. H. W., S. Y. Lee, J. Chen, R. P. So, and M. T. Williams. 2018. “A Model of Intersectional Stress and Trauma in Asian American Sexual and Gender Minorities.” Psychology of Violence 8 (6): 657–668. https://doi.org/10.1037/vio0000204

- Clark, R. S., and B. L. Stubbeman. 2021. “I had Hope. I Loved This City Once.”: A Mixed Methods Study of Hope within the Context of Poverty.” Journal of Community Psychology 49 (5): 1044–1062. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.22502

- Crenshaw, K. 1989. “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics.” University of Chicago Legal Forum 1989 (1): 139–167.

- Curtis, E., R. Jones, D. Tipene-Leach, C. Walker, B. Loring, S.-J. Paine, and P. Reid. 2019. “Why Cultural Safety rather than Cultural Competency is Required to Achieve Health Equity: A Literature Review and Recommended Definition.” International Journal for Equity in Health 18 (1): 174. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-019-1082-3

- Dam, L. 2023. “Be(com)ing an Asian Tangata Tiriti.” Kōtuitui: New Zealand Journal of Social Sciences Online 18 (3): 213–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/1177083X.2022.2129078

- Ellis, S. J., D. W. Riggs, and E. Peel. 2019. Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans, Intersex, and Queer Psychology: An Introduction (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Fenaughty, J., A. Ker, M. Alansari, T. Besley, E. Kerekere, A. Pasley, P. Saxton, P. Subramanian, P. Thomsen, and J. Veale. 2022. Identify Survey: Community and Advocacy Report. https://www.identifysurvey.nz/publications

- Fenaughty, J., K. Tan, A. Ker, J. Veale, P. Saxton, and M. Alansari. 2023. “Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Change Efforts for Young People in New Zealand: Demographics, Types of Suggesters, and Associations with Mental Health.” Journal of Youth and Adolescence 52 (1): 149–164. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-022-01693-3

- Fraser, G., J. K. Shields, A. Brady, and M. S. Wilson. 2019. The Postcode Lottery: Gender-affirming Healthcare Provision across New Zealand’s District Health Boards. https://osf.io/f2qkr/

- Hahm, H. C., and C. Adkins. 2009. “A Model of Asian and Pacific Islander Sexual Minority Acculturation.” Journal of LGBT Youth 6 (2-3): 155–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/19361650903013501

- Hsieh, H.-F., and S. E. Shannon. 2005. “Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis.” Qualitative Health Research 15 (9): 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

- Institute of Medicine. 2011. The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

- Le, T. P., B. T. Bradshaw, M. Q. Wang, and B. O. Boekeloo. 2022. “Discomfort in LGBT Community and Psychological Well-being for LGBT Asian Americans: The Moderating Role of Racial/Ethnic Identity Importance.” Asian American Journal of Psychology 13 (2): 149–157. https://doi.org/10.1037/aap0000231

- Mao, L., J. Mccormick, and P. Van de Ven. 2002. “Ethnic and Gay Identification: Gay Asian Men Dealing with the Divide.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 4 (4): 419–430. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691050110148342

- Meyer, D. 2015. Violence against Queer People: Race, Class, Gender, and the Persistence of Anti-LGBT Discrimination. New Brunswick, NB: Rutgers University Press.

- Moe, J. L., P. J. Dupuy, and J. M. Laux. 2008. “The Relationship between LGBQ Identity Development and Hope, Optimism, and Life Engagement.” Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling 2 (3): 199–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/15538600802120101

- Moe, J., N. Sparkman-Key, A. Gantt-Howrey, B. Augustine, and M. Clark. 2023. “Exploring the Relationships between Hope, Minority Stress, and Suicidal Behavior across Diverse LGBTQ Populations.” Journal of LGBTQ Issues in Counseling 17 (1): 40–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/26924951.2022.2105773

- Nakhid, C., M. Tuwe, Z. Abu Ali, P. Subramanian, and L. Vano. 2022. “Silencing Queerness – Community and Family Relationships with Young Ethnic Queers in Aotearoa New Zealand.” LGBTQ + Family: An Interdisciplinary Journal 18 (3): 205–222. https://doi.org/10.1080/27703371.2022.2076003

- Nakhid, C., C. Yachinta, and M. Fu. 2022. “Letting In/“Coming ut” – Agency and Relationship for Young Ethnic Queers in Aotearoa New Zealand on Disclosing Queerness.” LGBTQ + Family: An Interdisciplinary Journal 18 (3): 281–303. https://doi.org/10.1080/27703371.2022.2091704

- Rainbow Support Collective. 2023. More Resources for Supporting Rainbow Young People. https://www.be-there.nz/resources

- Rice, C., E. Harrison, and M. Friedman. 2019. “Doing Justice to Intersectionality in Research.” Cultural Studies ↔ Critical Methodologies 19 (6): 409–420. https://doi.org/10.1177/1532708619829779

- Roy, R., L. M. Greaves, R. Peiris-John, T. Clark, J. Fenaughty, K. Sutcliffe, D. Barnett, V. Hawthorne, J. Tiatia-Seath, and T. Fleming. 2020. Negotiating Multiple Identities: Intersecting Identities among Māori, Pacific, Rainbow and Disabled Young People. Auckland: The Youth19 Research Group.

- Statistics New Zealand. 2021. LGBT + Population of Aotearoa: Year Ended. https://www.stats.govt.nz/reports/lgbt-plus-population-of-aotearoa-year-ended-june-2020

- Snyder, C. R. 2002. “Hope Theory: Rainbows in the Mind.” Psychological Inquiry 13 (4): 249–275. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1304_01

- Tan, K. 2023. “Talking about Race and Positionality in Psychology: Asians as Tangata Tiriti.” Journal of the NZCCP 33 (1): 107–111. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8187858

- Tan, K. K., and A. T. Saw. 2022. “Prevalence and Correlates of Mental Health Difficulties amongst LGBTQ People in Southeast Asia: A Systematic Review.” Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health https://doi.org/10.1080/19359705.2022.2089427

- Tan, K. K., A. Yee, and J. F. Veale. 2022. “Being Trans Intersects with My Cultural Identity”: Social Determinants of Mental Health among Asian transgender people.” Transgender Health 7 (4): 329–339. https://doi.org/10.1089/trgh.2021.0007

- Tan, S., and C. Weisbart. 2022. “Asian-Canadian Trans Youth: Identity Development in a Hetero-cis-normative White World.” Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity 9 (4): 488–499. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000512

- Wandrekar, J. R., and A. S. Nigudkar. 2020. “What do we know about LGBTQIA + mental health in India? A review of research from 2009 to 2019.” Journal of Psychosexual Health 2 (1): 26–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/2631831820918129

- Wesp, L. M., L. H. Malco, A. Elliott, and T. Poteat. 2019. “Intersectionality Research for Transgender Health Justice: A Theory-driven Conceptual Framework for Structural Analysis of Transgender Health Inequities.” Transgender Health 4 (1): 287–296. https://doi.org/10.1089/trgh.2019.0039

- Wong, S. F. 2021. Asian Public Health in Aotearoa New Zealand. https://www.asiannetwork.org.nz/resources/asian-health/

- Yohani, S. C. 2008. “Creating an Ecology of Hope: Arts-based Interventions with Refugee Children.” Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal 25 (4): 309–323. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-008-0129-x