Abstract

Young people comprise a significant proportion of migrants and refugees in Australia. Many encounter challenges in accessing contraception information and services. This study explored the views and experiences of young women from migrant and/or refugee backgrounds regarding the contraceptive implant and related decision-making. Interviews were conducted with 33 women, aged 15–24, living in New South Wales, Australia, who spoke a language other than English and had some experience of the implant. Three themes were developed from the data as follows: ‘Finding your own path’: contraception decision-making (in which participants described sex and contraception as being taboo in their community, yet still made independent contraceptive choices); Accessing ‘trustworthy’ contraception information and navigating services (in which participants consulted online resources and social media for contraception information, and preferred discussions with healthcare providers from outside their community); and Views and experiences of the contraceptive implant (while the implant was described as a ‘Western’ method, most participants regarded it as an acceptable, convenient, cost-effective, and confidential means of contraception). Decision-making regarding the implant is influenced by many factors which must be considered in health promotion efforts and when providing clinical care. Consideration of more informative health promotion resources, peer education strategies, and healthcare provider training is warranted to support contraception decision-making and choice.

Introduction

Australia continues to become increasingly culturally diverse due to inward migration. Nearly one-third of current Australians were born overseas and almost half of all Australians have a parent who was born overseas (ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) Citation2021a). In 2020, 59% of recent migrants were women (MCWH (Multicultural Centre for Women’s Health) Citation2021a). Young people contribute to a significant proportion of migrant and refugee populations in Australia, with one in four young people coming from a refugee or migrant background (Lidday Citation2016). Australia also attracts a growing population of young international students (WHIN (Women’s Health in the North) Citation2020; OECD 2019); in 2019, international students accounted for 21% of enrolled students in Australia, compared to a 6% average across other Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries (OECD 2019). Despite a drop in international enrolments due to the COVID-19 pandemic, enrolments are rising again (8% rise from 2021 to 2022) and are expected to continue to grow (Ferguson and Spinks Citation2021; Australian Government, Department of Education Citation2023).

Despite the increasing cultural diversity of Australia’s population, only 2% of published health research has focused on multicultural health (Mengesha et al. Citation2017). The limited evidence available suggests that women from a migrant or refugee background may experience particular challenges in accessing health information and services, including in relation to sexual and reproductive health (MCWH (Multicultural Centre for Women’s Health) Citation2016; MCWH (Multicultural Centre for Women’s Health) Citation2021a; Lang et al. Citation2020; MCWH (Multicultural Centre for Women’s Health) Citation2021b). Young people from a migrant and refugee background commonly underutilise services for sexual and reproductive healthcare and may face barriers to access which can make them further vulnerable to poor health outcomes, including unintended pregnancy (Botfield et al. Citation2018; Maheen et al. Citation2021; Metusela et al. Citation2017; Napier-Raman et al. Citation2022).

Rates of unintended pregnancy are relatively high in Australia, with approximately 40% of pregnancies being unintended (Organon Citation2022a). This can contribute to psychological, social, and financial pressure on women and their families (Organon Citation2022a). One in four unintended pregnancies result in abortion, which is relatively high compared to other high-income countries (Mazza et al. Citation2017). The oral contraceptive pill and male condoms are the most popular types of contraception used by Australian women (Mazza et al. Citation2017; Organon Citation2022b). Although these can be effective methods, their reliability is highly user-dependent (Mazza et al. Citation2017). Women from a migrant or refugee background also have less uptake of modern contraception compared to other Australian women (MCWH (Multicultural Centre for Women’s Health) Citation2021a), with those born in a non-English speaking country more likely to use withdrawal and male condoms (MCWH (Multicultural Centre for Women’s Health) Citation2021a; Mazza et al. Citation2017).

Long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) methods, including the subdermal contraceptive implant and intra-uterine devices (IUD), are very effective in preventing pregnancy (Organon Citation2022b; Winner et al. Citation2012). However, LARC uptake remains relatively low in Australia with around 12.5% of women using these methods (Mazza et al. Citation2017; Turner et al. Citation2021). Whilst the contraceptive implant can be a popular LARC option for young women from a non-migrant and refugee background (Temple-Smith and Sanci Citation2017), there is limited evidence regarding young migrant and refugee women’s uptake of the implant or their perspectives on this method (Napier-Raman et al. Citation2022). However, a study from Sweden suggests that more women from a migrant background than non-migrant women plan to use the implant after experiencing contraceptive failure (Iwarsson et al. Citation2019).

Limited research has been undertaken regarding contraceptive decision-making by young women from a migrant or refugee background in Australia, and in particular, what factors influence and inform their views, experiences, and decision-making in relation to the contraceptive implant. We conducted a qualitative study to explore the views and experiences of young women from a migrant or refugee background regarding their contraception practices and choices, particularly in relation to the contraceptive implant, and to consider the factors that inform and influence their views, experiences, and decision-making processes.

Methods

We conducted a qualitative study with young women from a migrant or refugee background in Sydney, the capital city of New South Wales (NSW). NSW has the greatest proportion of young people who migrated to Australia (VicHealth et al. Citation2017), and Sydney has one of the largest populations of overseas born Australians (ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) Citation2021b, Citation2021c). A qualitative research design was used for this study as it allowed us to gain a contextualised and richer understanding of the views, experiences, and decision-making processes of young women from a migrant and refugee background regarding the contraceptive implant (Hennink et al. Citation2011). The study was conducted by a research team at Family Planning Australia, a non-governmental organisation providing sexual and reproductive health clinical care, education and training, and research (FPA (Family Planning Australia) Citation2023).

Recruitment and sampling

Young women aged 15–24 years, who lived in NSW, spoke a language other than English at home, identified as coming from a migrant or refugee background, and had some form of experience with the contraceptive implant (i.e. were potential users [considering getting the implant], current users or past users), were eligible to participate. Non-probability purposive sampling and snowball sampling were utilised to reach prospective participants (Bryman Citation2016; Liamputtong Citation2020). To recruit a diverse range of young women from a migrant or refugee background and reduce selection bias a range of recruitment strategies were used, including promotion via professional and personal networks, social media, community organisations and peer referrals. Study posters and flyers in English, traditional simplified Chinese, Arabic and Vietnamese were displayed in waiting rooms of Family Planning Australia clinics in Sydney and shared among professional networks. A dedicated webpage was developed which included an online expression of interest form in the above four languages. These four languages were chosen as they represent the most commonly spoken languages in NSW after English (ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) Citation2021d).

Data collection

Semi-structured first interviews and repeat interviews with a sub-set of first interview participants were conducted between October 2020 and November 2022. This extended period of recruitment and data collection was due to Covid-19 constraints and associated lockdowns in NSW. Interviews were conducted face-to-face or via phone as chosen by the participant. All interviews were conducted in English, although there was an option for a phone-based NAATI-accredited translator if required. At the end of each interview, participants were asked to complete a short demographic questionnaire and were asked if they were interested in participating in a repeat interview to explore any changes in their contraception choice and related views and experiences approximately three months after the first interview. All interviews were audio-recorded, de-identified using participant codes, and transcribed verbatim. De-identified transcripts were imported into qualitative analysis software NVivo (Release 1.0) for coding and thematic analysis.

Data analysis

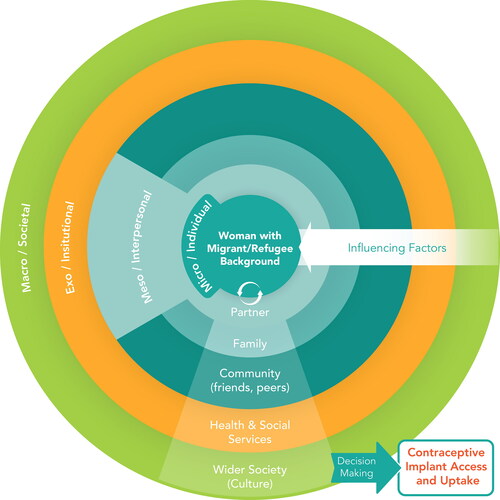

Following the principles of reflexive thematic analysis as described by Braun and Clarke (2022), initial deductive codes informed by the interview guides and research objectives were initially created and later supplemented and refined by inductive codes derived from the data (Braun and Clarke 2022). The code structure was developed in an iterative process starting early in the data collection phase by GR (Neale 2016). The coding frame was refined following a review of all interview transcripts by GR, and prospective themes and sub-themes were identified by GR and discussed with JB. Iterative categorisation, a systematic technique that supports qualitative analyses including thematic analysis, was then applied to the coded data to enhance rigour in the analysis process (Neale 2016). Final themes were discussed, agreed by all authors, and interpreted according to a framework developed by GR in collaboration with JB (see ); this framework was informed by the socio-ecological model (Golden and Earp Citation2012) and the social determinants of health framework (Solar and Irwin Citation2010; WHO 2017).

Figure 1. Framework for Multi-Level factors influencing the decision-making process regarding the contraceptive implant of young women with migrant or refugee background.

The socio-ecological model and the social determinants of health framework focus on complementary aspects of the immigration experience and emphasise the interplay between individual and other factors that can facilitate or inhibit contraception access and uptake (Mengesha et al. Citation2017). Both have been used in previous studies to describe the complex influences on contraception choice (D’Souza et al. Citation2022) and to identify migrant and refugee youth perspectives on sexual and reproductive health and rights (Napier-Raman et al. Citation2022). Our adapted framework goes a step further by illustrating how factors on each level may individually and cumulatively inform or influence migrant and refugee women’s contraception decision-making, access and uptake (Castañeda et al. Citation2015).

Ethical considerations

Prospective participants received a participant information sheet which described the conduct and purpose of the study (available in four languages). Informed consent was obtained prior to each interview, either verbally or written, depending on whether the participant chose a phone or face-to-face interview. Parental consent for young women aged 16–18 years was not obtained as we felt this would be a barrier to their participation. All prospective participants were informally ‘screened’ prior to their interview to ensure they demonstrated sufficient maturity to understand the information provided and could give informed consent (Bird Citation2011; Hildebrand et al. Citation2015). Ethical approval for the study was received from the Family Planning Australia Human Research Ethics Committee (Approval no. R2020-03).

Findings

In total, 33 initial interviews and 9 repeat interviews were conducted for the study. Participants came from a wide geographic area of Sydney with the majority residing in the Greater Western Sydney area. Over half of the participants were 22–24 years of age and currently in a relationship (55% and 61% respectively) (). Half of participants (49%) were currently using the contraceptive implant, while 21% were past implant users, and the remaining 30% were considering implant use in the future. Nearly half of participants were born in Australia (46%), and over half had no religious affiliation (58%). Only one person requested the help of a translator during the eligibility screening process. However, the same participant decided not to proceed with the interview due to scheduling conflicts. None of the participants who participated in the interviews required the assistance of a NAATI-accredited translator.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of participants (self-reported).

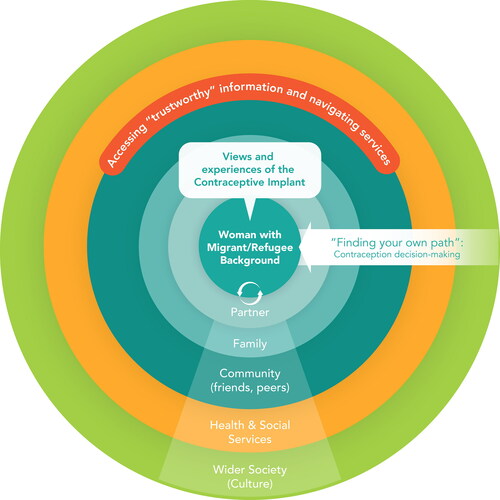

A number of factors were found to influence the views, experiences, and decision-making processes of young women from a migrant or refugee background regarding contraception. Although the focus of the study was on the contraceptive implant, most women also discussed their views in relation to contraception more broadly. Following preliminary analysis we applied our findings to the different levels of our adapted framework (see ), which are described by the following three themes.

Figure 2. Themes applied to framework for Multi-Level factors influencing the decision-making process regarding the contraceptive implant of young women with migrant or refugee background.

‘Finding your own path’: contraception decision-making

Sex and contraception were commonly described by participants as taboo and were rarely discussed within their families and communities. Sex was predominately viewed as a means to produce children in marriage within communities. Participants described how contraception use was therefore often seen as a sign of promiscuity within their communities, which could lead to community judgement, and which further silenced open conversations about contraception.

… contraception, like, I don’t ever hear of my relatives or anyone mentioning it. It’s just, kind of, almost like assumed knowledge that you remain abstinent until marriage and then you have a family (Chinese, 23 years old, current user).

I think it sort of links to – so when someone’s on like a birth control, they assume that this person has sex regularly and it looks down upon (Vietnamese, 22 years old, current user).

It’s still taboo. That’s the thing, there’s no talk of the pill, or condoms, or the IUD, or the rod – yeah (Egyptian, 21 years old, potential user).

Despite the associated stigma, several participants said that they had discussed contraception, and the implant specifically, with their mother or sister. This appeared to be most common when the mother or sister had used the implant as well. Fathers were not mentioned as ever being involved in discussion about contraceptive matters.

I didn’t know about the implant until – well until my sister brought it up with me only last year (Filipino, 22 years old, current user).

My sister, she also has the Implanon as well. So I’d ask her if she has any particular symptoms, side effects. See if she’s going through what I’m going through stuff like that (Vietnamese, 22 years old, current user).

I think my mum definitely helped me, she just explained that her experience [with the implant] was quite positive with it (Peruvian, 20 years old, current user).

My dad is pretty traditional, so I don’t talk about this with him (Malaysian, 20 years old, potential user).

Discussions about contraception most commonly occurred among friends. Many participants felt that discussing contraception options and related experiences with friends enabled them to better contextualise and understand different experiences. This was particularly important for participants who were considering getting an implant. The experiences of friends, either positive or negative, had an immense impact on the decision-making process of participants considering the implant.

I was a bit concerned about getting an implant before because I didn’t know what it was going to be like. I read all this information about it online and stuff like that but I didn’t know anyone who had a personal experience with it. So my friend told me she got the Implanon as well…and how it’s been positive for her. So that sort of convinced me to get it as well (Chinese, 19 years old, current user).

If it’s something that I know a friend has experience with I’ll go to them to ask for advice (Chinese, 20 years old, current user).

Despite the stigma relating to contraception, many participants reported still using contraception but keeping it secret from their parents and families. Many therefore preferred a more discrete method of contraception such as the contraceptive implant. Most participants expressed the desire to find their own path in relation to contraception by making independent choices and attempted to find a balance between cultural and religious values and expectations and their own experiences and understanding. While some reported feeling shame for using contraception, they often found a way to define their own terms that allowed them to live their lives as they intended without losing their cultural and religious integrity.

For a long time I felt a little bit ashamed to go to church. But I realised that if anything I’m doing something that is right for me. So I felt God should be fine with that (Bolivian, 20 years old).

I think there’s like a necessity, because at the end of the day everyone should have that choice over their bodily autonomy and what they choose to do sexually. And they should have health measures that accommodate for those choices (Bengali, 19 years old, potential user).

Accessing ‘trustworthy’ contraception information and navigating services

Participants expressed the desire for confidential, supportive, and non-judgemental information and services regarding contraception, including the implant. Some reported that they had not received any sexuality education at school or had limited exposure to contraception education in their home country, especially regarding LARC options such as the implant. Participants who had received more comprehensive forms of sexuality education in Australia or elsewhere valued its importance in enabling them to make informed choices.

I have friends from all around and sometimes, just us girls, just we’ve talked about contraception and how it’s taught in different countries… I feel like just I’ve been really lucky to be born somewhere where it’s not taboo (Finnish, 22 years old, current user).

I really didn’t have any background of any sort of contraception in Afghanistan, I really didn’t know if they have anything like that. Everything I learned over here, I have no background from my country (Afghani, 22 years old, past user).

Before I came to Australia I didn’t know about all this contraception. The only contraception I knew was condoms (Rwandan, 20 years old, past user).

Many participants preferred resources developed by government or health organisations as they were perceived to be ‘trustworthy’ and ‘reliable’. However, while they felt the information provided was very factual, they suggested there is little information on how likely described side-effects could occur or impact day-to-day life. For many, the taboo and silence in their community about contraception created generalised ‘fear’ of using any contraception and hence they desired more comprehensive information about contraception to support decision-making. Some participants recommended that contraception resources should address cultural concerns and mental health implications, and others that health promotion websites could include demonstration videos with explanations of implant insertion and removal procedures to ease fear among first time users.

I think the resources that I received were very medically based in terms of this is what Implanon is, this is the chemical in it, this is like how long it will last for, things like that and they generally told me what the symptoms were and could be and I think it’s hard to pinpoint that down to what specifically you are going to have (Vietnamese, 23 years old, current user).

I think it could be a bit of both, informative and also women sharing their experiences, because I remember they told me that you get a one in five bleeding pattern, so maybe women with each bleeding pattern, or something like that explaining it (Peruvian, 20 years old, current user).

I think, I just like looking at the pros and cons obviously online, but anyone could do that, but I guess it would be really great to be able to talk to someone, whether it’s over the phone, or just online on a chat (Bengali, 19 years old, potential user).

Social media platforms and YouTube were also commonly used by participants to aid decision-making regarding contraception. Some suggested they would find information on their social media feed that prompted them to investigate further about different contraception types.

….And there’s quite a lot of resources online like a lot of YouTube videos that explain the pros and cons. And I find that, probably, the most helpful in terms of making a judgment on which one to choose (Chinese, 23 years old, current user).

Definitely online. I feel like that’s my first point of call, just watch YouTube videos from a doctor, or from certified, verified [source] online (Bengali, 19 years old, potential user).

yeah, normally I don’t go and look for it myself on social media, it sort of usually comes to me in my feed or in my timeline (Chinese, 19 years old, current user).

Although most participants preferred to obtain contraception information online as doing so was considered ‘accessible’ and ‘private’, many expressed concerns regarding accuracy. Most participants indicated that they initially ‘Googled’ information and then followed up with a healthcare provider to further discuss contraception options to make an informed choice that suits their needs.

Definitely online, then I know even if I can’t find it online I could just probably just ask my doctor about it (Bengali, 19 years old, potential user).

There’s a lot of resources online. I’m not sure (…) how accurate everything is (Chinese, 20 years old, current user).

I went on the Family Planning website which they have a lot of resources, just pamphlets with every type of method of contraception and you could just read through it, and then finally just talking to the doctors themselves (Columbian, 22 years old, potential user).

Generally, participants who were considering using, replacing or removing the implant preferred to discuss this with a female healthcare provider who is not part of their cultural community. Many participants worried that their regular family doctor or a healthcare provider with close ties to their cultural community would judge them or disclose their intent to use contraception to their families. Privacy, confidentiality, trust in healthcare provider and having a safe space when attending services were of upmost importance to participants.

I think GPs are a little bit tricky because my family doctor is also my mum’s brother, my uncle, and I think that way, quite a few doctors in my area even if they are not directly related to me, they do know my family, the Viet community is close knit and so I would actually avoid talking about it at GPs (Vietnamese, 22 years old, current user).

The doctor was actually almost from the same background as me, and it was just such an awkward conversation, and it just felt really uncomfortable (Bengali, 19 years old, potential user).

I am going to steer clear away from my community people even if it’s GP… I prefer speaking to someone that is a little bit more free from judgment (Vietnamese, 24 years old. Current user).

The convenience of a clinic’s location and the costs of services were also mentioned as important factors by participants. Many participants with Medicare access (i.e. government subsidised services) indicated that the cost of an implant insertion was covered by Medicare and this positively influenced their decision to get one as it was an affordable option. In contrast, cost was raised as a barrier by participants who did not have access to Medicare.

I think if you’re not a citizen, it’s like $130, so for me I think it was $5, so it was affordable. The insertion was obviously free because it’s covered by Medicare, which is amazing (Sierra Leonean, 24 years old, current user).

They [medical centre] charge you a $50 fee or something like that. And I was just – I couldn’t afford to do that (Chinese, 19 years old, current user).

I don’t have Medicare since I’m not on a permanent residency yet (.) cost factors into it as well (Indonesian, 24 years old, potential user).

… with the Implanon implant it was only $40, and I only had to pay for the actual implant itself and not for the procedure (Bolivian, 20 years old, past user).

Views and experiences of the contraceptive implant

Participants commonly described the implant as a ‘Western’ method of contraception as it was perceived to be more frequently used in Western countries such as Australia. They suggested that other forms of contraception, including condoms and often the oral contraceptive pill, were more available in their home country and were therefore more popular choices among some women.

Most participants started considering or using the implant once they became sexually active, were in a stable relationship, or after experiencing an unintended pregnancy. Among available LARC options, most preferred the implant over the IUD as it was perceived to be less invasive in comparison. Participants appreciated the cost-effectiveness, convenience, reliability and discreteness of the implant, which allowed them to be protected from pregnancy and to forget about it once inserted.

I went through an unwanted pregnancy before and that really made me – went straight to the implant knowing that the efficacy was really high (Vietnamese, 22 years old, current user).

I felt like the implant was more cost effective in the long run because I would get prescriptions for the pill and then I would have to take the pill every day and setting up reminders (Filipino, 24 years old, current user).

I think another pro to me about the Implanon, was, well, I don’t have to be taking it every day. I don’t have to be stashing pills away so that my parents can’t find them. It seemed like a much more covert way of contraception (Vietnamese, 23 years old, current user).

I used Implanon. It was good, it was invisible (.) (Afghani, 22 years old, past user).

Many potential implant users expressed concern about possible side-effects of the implant due to ‘additional hormones in the body’ and wondered how it would affect their ‘daily routine’. These concerns were further compounded if participants had friends or followed peers on social media platforms who described experiencing side-effects with the implant, as described in the first theme above. Potential implant users also worried that the implant might cause noticeable changes such as irregular menstruation, which could give rise to suspicion in conservative parents.

Like something about Implanon that scares me is having it in your arm, and does that hurt, does it have hormonal side effects, will it affect my gym routine? (Bengali, 19 years, potential user)

I’ve heard of someone else using it and I think it dramatically changed their period behaviour. I think that was something I really didn’t want (Indonesian, 24 years old, potential user).

It [the implant] could affect the period cycle and that was something I didn’t really want my mum to find out. And if she finds out that my period is not regular like it used to be then she might start questioning why that is (Indonesian, 24 years old, potential user).

While potential users expressed some concerns regarding the contraceptive implant, many were still considering getting one due to its high effectiveness and convenience. Most were more inclined to get the implant if they had heard good experiences about the implant from friends or other peers.

I like that once it’s in there you can just live your life and kind of forget it’s there. So that’s really comforting. And I definitely like the safety around it as well (Bengali, 19 years old, potential user).

I feel like if I were to go into another relationship where I would be sexually active, I would choose to use the implant (Columbian, 22 years old, potential user).

I think positively about the implant. I haven’t heard anything negative about it (Macedonian, 16 years old, potential user).

Most participants with an implant were satisfied with the implant and felt they had adjusted well to it, although some reported experiencing challenges such as irregular menstrual bleeding, spotting and mood changes. Some felt that the irregular bleeding and spotting interfered with daily activities and routines. Even though many participants were aware of the possibility of these side-effects, they ‘didn’t feel like it was real enough’ (Chinese, 23 years old, past user) until they experienced them themselves. While most participants found the side-effects acceptable, some decided to stop using the implant due to these, particularly for those who had ongoing irregular bleeding rather than temporary or short-term. For Muslim participants in particular, irregular bleeding and spotting was a ‘pretty dominating concern’ (Bengali, 19 years old, potential user) as it could interfere with engagement in religious rituals and obligations.

I’ve gotten a lot of spotting, but I always knew that was a possibility (…) It’s a little bit annoying, but I deal with it (Filipino, 17 years old, current user).

It messed around with my moods and it also left me continuously bleeding (.) I think the most unacceptable thing was the changes in mood and just having them [side-effects] all pile up on each other. So it wasn’t just one factor (Chinese, 23 years old, past user).

I do accept it and I think that everything else besides the bleeding has worked well for me so far (Chinese, 19 years old, current user).

I didn’t think I would spot that much. So I knew that you could spot up to six months, but when it went past that and then – like I went on the pill to target that, (…) just so I could get more regular periods (Bolivian, 20 years old, past user).

I had the whole time (is) bleeding, like spot bleeding, like very slight bleeding, which was stopping me from praying so that was disappointing me (Afghani, 22 years old, past user).

Some participants noted they had had concerns about bruising and pain in their arm prior to having an implant inserted. While many were relieved that the procedure was not as painful as expected, some were worried that a visible bruise on the arm might raise suspicion among family members. However, most noted that their bruise quickly disappeared after insertion.

I don’t think it was anything bad in particular. Like it was really quick as well. So yeah, I think it was great, yeah (Vietnamese, 22 years old, current user).

The experience at first I was super scared (…) But I was very surprised when I didn’t feel anything (Rwandan, 20 years old, current user).

It was a bit bruised. It was kind of difficult to hide from my family because of the massive bruise that came about from getting it (Chinese, 19 years old, current user).

I can barely see the bruise anymore. It’s like it’s gone. Very unnoticeable (Chinese, 20 years old, current user).

Most past and current implant users stated that they would recommend the implant to others as they were satisfied by the implant overall and perceived it to be a good choice among available contraception options.

Everybody is different and people have different reactions to it so I’d recommend they try it out. If it’s not for them then it’s not for them. If it is, then I’ve helped someone out (Filipino, 24 years old, current user).

I would recommend it to other people. Especially people my age who fall into that concession category which means that getting the implant is probably going to be pretty cheap for them as well (Chinese, 19 years old, current user).

Other women, the Implanon would be the first thing I would recommend to anyone before any other contraception (Rwandan, 20 years old, current user).

It’s very straightforward and it’s not intimidating, and I feel comfortable knowing that I’m protected now, so it’s good (Filipino, 22 years old, current user).

Discussion

Our study explored the views, experiences and decision-making processes of young women from a migrant or refugee background regarding the contraceptive implant. Despite the diversity of participants, we identified a number of similarities relating to their views and experiences of the contraceptive implant. These included the influence and impact of culture, religion, community values and friends on decision-making processes; preferences to access social media and online resources to learn about contraceptive options; and a desire to access confidential, private and non-judgmental contraception services. Most felt the implant was an acceptable method of contraception and would recommend it to others.

Our findings suggest that due to stigma and taboo, open conversations about contraception are often limited among young women from a migrant or refugee background, which is a consistent finding among previous studies in Australia and internationally (Botfield et al. Citation2018; D’Souza et al. Citation2022; Metusela et al. Citation2017; Napier-Raman et al. Citation2022). Certain methods of contraception, including the contraceptive implant, may therefore not be well known about, which can contribute to low knowledge, misinformation, and uptake. Concerns expressed by participants regarding implant side-effects and potential insertion pain have also been described in a systematic review on migrant and refugee youth perspectives on SRH across Australia (Napier-Raman et al. Citation2022). This underlines the need for informative online health promotion resources to better address these concerns and enable young women from a migrant or refugee background to obtain accurate information about the implant and support decision-making. Online resources could include ‘real-life’ examples from users, or a demonstration video of the implant insertion and removal procedure. Engaging and collaborating with young women from a migrant or refugee background in the development of such online resources would better ensure their concerns and needs are met.

Participants expressed a desire to find their own path in relation to contraception and navigated their own contraceptive decision-making through discussing with trusted family and friends and considering more ‘discrete’ methods of contraception such as the contraceptive implant. Most participants also consulted online resources and the experiences of peers on social media to support their decision-making process regarding the implant, which is consistent with other studies on contraception choices of young women from a migrant or refugee background (Maheen et al. Citation2021; Mpofu et al. Citation2021). In line with findings from other studies (D’Souza et al. Citation2022), contraception experiences of peers and friends had the greatest influence on young migrant and refugee women’s contraceptive choices, including the implant. Considering that most participants discussed contraception with friends and consulted peers for shared experiences, the exploration of creative approaches for peer education is warranted. A study evaluating the impact of a theatre-based peer education intervention on sexual health self-efficacy of newly arrived young people in Canada found that the intervention led to increased sexual health self-efficacy in participants (Taylor et al. Citation2022). Peer education approaches such as this could be considered to better support contraception education among young women from a migrant or refugee background.

Young women from a migrant or refugee background in this study highly valued confidentiality, non-judgement, and privacy when accessing contraception services, and preferred discussing contraception with healthcare providers from a different cultural background. It is therefore critical that healthcare providers ensure privacy and confidentiality during consultations to increase trust among young women from a migrant or refugee background accessing contraception services (Maheen et al. Citation2021). Healthcare providers should also ideally be trained in culturally sensitive and person-centred care to ensure contraception services are responsive to the needs, values and preferences of young women from a migrant or refugee background (ACSQHC (Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care) Citation2023; Mengesha, Dune, and Perz Citation2016; Hawkey, Ussher, and Perz Citation2022). Cultural training for healthcare providers and the evaluation of GP resource kits to enhance the skills of healthcare providers to care for culturally diverse young people could be considered for contraception service providers (Braeken and Rondinelli Citation2012; Chown and Kang Citation2004).

Limitations

Our study contributes new evidence about the contraceptive decision-making processes of young women with a migrant or refugee background, in particular regarding the contraceptive implant. However, there are some limitations to acknowledge. While we were able to recruit participants from a range of cultural and language backgrounds, the findings should be broadly interpreted and cannot be applied to specific cultural groups. None of the participants required the assistance of a NAATI-accredited translator. Therefore, young women from a migrant or refugee background with limited English-speaking skills may have been missed. Furthermore, although recruitment materials were available in English and three commonly spoken languages in NSW, participants from other language groups or with lower literacy may have been excluded. Moreover, the included study population did not comprise any young people from a gender diverse background and hence their views and experiences are not represented in this study. The views and experiences of hard-to-reach populations such as young people from a migrant or refugee background who belong to an ethnic minority, or who do not engage with health services or social media, may also have been missed.

Conclusion

This study has highlighted how contraceptive decision-making processes of young women from a migrant and refugee background are contextualised within wider social, cultural, and institutional environments and influenced by a range of multi-level factors. Despite the stigma associated with contraception, participants made their own contraceptive choices. They desired comprehensive and evidence-based information along with ‘real-life’ experiences, and private, confidential, and non-judgmental contraception services. Although concerns were expressed regarding the side-effects of the contraceptive implant, this method of contraception was found to be generally acceptable among young women from a migrant or refugee background. To support contraception decision-making and choice, it will be important to develop online health promotion resources that include real-life experiences, ideally in collaboration with young people; consider peer education strategies to educate and inform young people; and promote cultural sensitivity training for healthcare providers caring for young people.

Disclosure statement

No conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics). 2021a. "2021 Census: Nearly Half of Australians Have a Parent Born Overseas." Australian Bureau of Statistics. July 10, 2023. https://www.abs.gov.au/media-centre/media-releases/2021-census-nearly-half-australians-have-parent-born-overseas.

- ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics). 2021b. "Australia’s Population by Country of Birth - Statistics on Australia’s Estimated Resident Population by Country of Birth." Australian Bureau of Statistics. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/population/australias-population-country-birth/2021.

- ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics). 2021c. Regional Population – Statistics about the Population for Australia’s Capital Cities and Regions. Australia: Australian Bureau of Statistics.

- ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics). 2021d. "Snapshot of New South Wales." Australian Bureau of Statistics. https://www.abs.gov.au/articles/snapshot-nsw-2021.

- ACSQHC (Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care). 2023. "Person-Centred Care." Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. July 4, 2023.https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/our-work/partnering-consumers/person-centred-care.

- Australian Government, Department of Education. 2023. International Student Numbers by Country, by State and Territory. Department of Education. March 6, 2023. https://www.education.gov.au/international-education-data-andresearch/international-student-numbers-country-state-and-territory.

- Bird, S. 2011. “Consent to Medical Treatment: The Mature Minor.” Medicus 51 (9): 54–555.

- Botfield, J. R., A. B. Zwi, A. Rutherford, and C. E. Newman. 2018. “Learning about Sex and Relationships among Migrant and Refugee Young People in Sydney, Australia: ‘I Never Got the Talk About the Birds and the Bees.” Sex Education 18 (6): 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2018.1464905.

- Braeken, D., and I. Rondinelli. 2012. “Sexual and Reproductive Health Needs of Young People: Matching Needs with Systems.” International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics 119 (S1): S60–S63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2012.03.019.

- Bryman, A. 2016. Social Research Methods. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Castañeda, H., S. M. Holmes, D. S. Madrigal, M.-E D. Young, N. Beyeler, and J. Quesada. 2015. “Immigration as a Social Determinant of Health.” Annual Review of Public Health 36 (1): 375–392. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182419.

- Chown, P., and M. Kang. 2004. Adolescent Health: Enhancing the Skills of General Practitioners in Caring for Young People from Culturally Diverse Backgrounds; a Resource Kit for GPs. Australia: Transcultural Mental Health Centre and NSW Centre for the Advancement of Adolescent Health and Transcultural Mental Health Centre.

- D’Souza, P., J. V. Bailey, J. Stephenson, and S. Oliver. 2022. “Factors Influencing Contraception Choice and Use Globally: A Synthesis of Systematic Reviews.” The European Journal of Contraception & Reproductive Health Care 27 (5): 364–372. https://doi.org/10.1080/13625187.2022.2096215.

- Ferguson, H., and H. Spinks. 2021. Overseas Students in Australian Higher Education: A Quick Guide. Australia: Parliament of Australia, Social Policy Section. https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/rp/rp2021/Quick_Guides/OverseasStudents.

- FPA (Family Planning Australia). 2023. "About Us." https://www.fpnsw.org.au/about-us.

- Golden, S. D., and J. A. L. Earp. 2012. “Social Ecological Approaches to Individuals and Their Contexts: Twenty Years of Health Education & Behavior Health Promotion Interventions.” Health Education & Behavior 39 (3): 364–372. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198111418634.

- Hawkey, A. J., J. M. Ussher, and J. Perz. 2022. “What Do Women Want? Migrant and Refugee Women’s Preferences for the Delivery of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare and Information.” Ethnicity & Health 27 (8): 1787–1805. https://doi.org/10.1080/13557858.2021.1980772.

- Hennink, M., I. Hutter, and A. Bailey. 2011. Qualitative Research Methods. London: SAGE.

- Hildebrand, J., B. Maycock, J. Comfort, S. Burns, E. Adams, and P. Howat. 2015. “Ethical Considerations in Investigating Youth Alcohol Norms and Behaviours: A Case for Mature Minor Consent.” Health Promotion Journal of Australia 26 (3): 241–245. https://doi.org/10.1071/HE14101.

- Iwarsson, K. E., E. C. Larsson, K. Gemzell-Danielsson, B. Essén, and M. Klingberg-Allvin. 2019. “Contraceptive Use Among Migrant, Second-Generation Migrant and Non-Migrant Women Seeking Abortion Care: A Descriptive Cross-Sectional Study Conducted in Sweden.” BMJ Sexual & Reproductive Health 45 (2): 118–126. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjsrh-2018-200171.

- Lang, A. Y., R. Bartlett, T. Robinson, and J. A. Boyle. 2020. “Perspectives on Preconception Health Among Migrant Women in Australia: A Qualitative Study.” Women and Birth 33 (4): 334–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2019.06.015.

- Liamputtong, P. 2020. Qualitative Research Methods. Australia: Oxford University Press.

- Lidday, N. 2016. “Supporting Young People from Refugee and Migrant Backgrounds: The National Youth Settlement Framework.” Australian Government. Melbourne, Australia: Australian Institute of Family Studies. February 2, 2023. https://aifs.gov.au/resources/short-articles/supporting-young-people-refugee-and-migrant-backgrounds-national-youth#:∼:text=One%20in%20four%20young%20people,refugee%20or%20migrant%20background1.

- Maheen, H., K. Chalmers, S. Khaw, and C. McMichael. 2021. “Sexual and Reproductive Health Service Utilisation of Adolescents and Young People from Migrant and Refugee Backgrounds in High-Income Settings: A Qualitative Evidence Synthesis (QES).” Sexual Health 18 (4): 283–293. https://doi.org/10.1071/SH20112.

- Mazza, D., D. Bateson, M. Frearson, P. Goldstone, G. Kovacs, and R. Baber. 2017. “Current Barriers and Potential Strategies to Increase the Use of Long‐Acting Reversible Contraception (LARC) to Reduce the Rate of Unintended Pregnancies in Australia: An Expert Roundtable Discussion.” The Australian & New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology 57 (2): 206–212. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajo.12587.

- MCWH (Multicultural Centre for Women’s Health). 2016. “Sexual and Reproductive Health Data Report”. MCWH. https://www.mcwh.com.au/wp-content/uploads/MCWH-Sexual-and-Reproductive-Health-Data-Report-Aug-2016-V3-latest.pdf.

- MCWH (Multicultural Centre for Women’s Health). 2021a. “Data Report: Sexual and Reproductive Health 2021”. MCWH. https://www.mcwh.com.au/wp-content/uploads/SRH-Report-2021-for-web-accessible.pdf.

- MCWH (Multicultural Centre for Women’s Health). 2021b. “Act Now to Advance Health Equity: Migrant and Refugee Women’s Sexual and Reproductive Health.” MCWH. https://www.mcwh.com.au/wp-content/uploads/Act-Now-smaller-size.pdf.

- Mengesha, Z. B., T. Dune, and J. Perz. 2016. “Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Women’s Views and Experiences of Accessing Sexual and Reproductive Health Care in Australia: A Systematic Review.” Sexual Health 13 (4): 299–310. https://doi.org/10.1071/SH15235.

- Mengesha, Z. B., J. Perz, T. Dune, and J. Ussher. 2017. “Refugee and Migrant Women’s Engagement with Sexual and Reproductive Health Care in Australia: A Socio-Ecological Analysis of Health Care Professional Perspectives.” Plos One 12 (7): e0181421. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0181421.

- Metusela, C., J. Ussher, J. Perz, A. Hawkey, M. Morrow, R. Narchal, J. Estoesta, and M. Monteiro. 2017. “In My Culture, We Don’t Know Anything About That": Sexual and Reproductive Health of Migrant and Refugee Women.” International Journal of Behavioral Medicine 24 (6): 836–845. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-017-9662-3.

- Mpofu, E., S. Z. Hossain, T. Dune, A. Baghbanian, M. Aibangbee, R. Pithavadian, P. Liamputtong, and V. Mapedzahama. 2021. “Contraception Decision Making by Culturally and Linguistically Diverse (CALD) Australian Youth: An Exploratory Study.” Australian Psychologist 56 (6): 511–522. https://doi.org/10.1080/00050067.2021.1978814.

- Napier-Raman, S., S. Z. Hossain, M.-J. Lee, E. Mpofu, P. Liamputtong, and T. Dune. 2022. “Migrant and refugee youth perspectives on sexual and reproductive health and rights in Australia: A systematic review.” Sexual Health 20 (1): 35–48. https://doi.org/10.1071/SH22081.

- OECD. "Education at a Glance 2019". https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2019_CN_AUS.pdf.

- Organon. 2022a. "Impact of Unintended Pregancies". https://www.organon.com/australia/wp-content/uploads/sites/16/2022/09/ORG01_Report_FINAL_28June2022.pdf.

- Organon. 2022b. "Not What You’re Expecting: New Report Reveals the Impact of Unintended Pregnancies in Australia." https://www.organon.com/australia/news/unintended-pregnancy-report/.

- Solar, O., and A. Irwin. 2010. A Conceptual Framework for Action on the Social Determinants of Health. Social Determinants of Health Discussion Paper 2 (Policy and Practice). Geneva: WHO. https://www.who.int/social_determinants/corner/SDHDP2.pdf?ua=1.

- Taylor, S. B., L. Calzavara, P. Kontos, and R. Schwartz. 2022. “Sex Education by Theatre (SExT): The Impact of A Culturally Empowering, Theatre-Based, Peer Education Intervention on the Sexual Health Self-Efficacy of Newcomer Youth in Canada.” Sex Education 22 (6): 705–722. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2021.2011187.

- Temple-Smith, M., and L. Sanci. 2017. “LARCs as First-Line Contraception: What Can General Practitioners Advise Young Women?” Australian Family Physician 46 (10): 710–715.

- Turner, R., A. Tapley, E. Holliday, J. Ball, S. Sweeney, and P. Magin. 2021. “Associations of Anticipated Prescribing of Long-Acting Reversible Contraception by General Practice Registrars: A Cross-Sectional Study.” Australian Journal of General Practice 50 (12): 929–935. https://doi.org/10.31128/AJGP-09-20-5657.

- VicHealth, Data61, CSIRO. and MYAN. 2017. " Bright Futures: Spotlight on the Wellbeing of Young People from Refugee and Migrant Backgrounds." https://myan.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/bright-futures-spotlight-on-the-wellbeing-of-young-people-from-refugee-and-migrant-backgrounds.pdf

- Virginia, B., and C. Victoria. 2022. Thematic Analysis A Practical Guide. London: SAGE.

- WHO (World Health Organization). "Determinants of Health." https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/determinants-of-health.

- WHIN (Women’s Health in the North). 2020. Sexual Health Information Pathways Project – for International Students (SHIPP) Project Report Findings and Recommendations. Melbourne: Women’s Health In the North. https://www.whin.org.au/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2021/03/SHIPP-Project-Findings_FINAL_TMformat-Final-1.pdf.

- Winner, B., J. F. Peipert, Q. Zhao, C. Buckel, T. Madden, J. E. Allsworth, and G. M. Secura. 2012. “Effectiveness of Long-Acting Reversible Contraception.” New England Journal of Medicine 366 (21): 1998–2007. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1110855.