Abstract

High profile data breaches and the proliferation of self-tracking technologies generating bio-feedback data have raised concerns about data privacy and data sharing practices among users of these devices. However, our understanding of how self-trackers in sexual health populations, where the data may be sensitive, personal, and stigmatising, perceive data privacy and sharing is limited. This study combined industry consultation with a survey of users of the world’s first biofeedback smart vibrator, the Lioness, that enables users to monitor and analyse their sexual response intensity and orgasm duration over time. We found users of the Lioness are motivated to self-track by both individual and altruistic goals: to learn more about their bodies, and to contribute to research that leads to better sexual health outcomes. Perceptions of data privacy and data sharing were shaped by an eagerness to collaborate with sexual health researchers to challenge traditional male-centric perspectives in biomedical research on women’s sexual health, where gender plays a crucial role in defining healthcare systems and outcomes. This study extends our understanding of the non-digital aspects of self-tracking by emphasising the role of gender and inclusive healthcare advocacy in shaping perceptions of data privacy and sharing within sexual health populations.

Introduction

Self-tracking technologies have gained popularity in recent years by enabling users to measure and track physiological changes in the body. Through wearable or insertable devices that connect via Bluetooth to an app, users can monitor their bodies and generate biofeedback (often in datafied form) such as heart rate, breathing, sweat gland activity, temperature, and muscle contractions (Lupton Citation2021). In sexual health, these devices have become primary treatments for sexual dysfunction, addressing issues such as sexual pain and arousal in women and erectile dysfunction in men (Stanton and Kirakosian Citation2020). Those devices with artificial intelligence (AI) capabilities are the latest advances in the field of sextech that encompasses ‘biomedical technologies, therapeutic apps and platforms, and pleasure and entertainment-focused technologies’ (Albury, Stardust, and Sundén Citation2023; see also Burgess et al. Citation2022).

Prominent among these devices is the world’s first biofeedback smart vibrator, the Lioness, invented by California startup SmartBod Incorporated DBA Lioness. The device connects by Bluetooth to a secure Internet server from which users can download their pelvic floor output during periods of self-stimulation (Pfaus et al. Citation2022). Intimate biometric data such as body temperature and the intensity, frequency, and duration of pelvic floor contractions are collected and recorded by the user and can be compared across time to see patterns of performance that may be impacted by lifestyle factors such as stress, alcohol, drug use, lack of sleep and different sexual partners. In 2021, the second-generation Lioness 2.0 was launched with the device providing artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted guidance through an in-app ‘live’ track feature, enabling users to identify moments of high arousal and orgasm while using the device.

Rapidly advancing technology and highly publicised data breaches underscore the necessity for cyber-safe approaches to Internet-connected devices. In 2011, Fitbit users discovered their sexual activity data exposed in Google search results, then in 2017, WeVibe settled a $US3.75 million class action lawsuit for unauthorised data collection and unencrypted transmission when hacked (de Freytas-Tamura Citation2017). Subsequently, the Internet Society (Citation2018) updated its IoT Trust Framework (v2.5), emphasising comprehensive disclosures and security patching. Additionally, a consortium led by Mozilla and Consumers International published commercial guidelines urging adherence to minimum industry standards such as encryption, automatic updates, and password strength requirements (Mozilla Citation2018). In the discussion section of this paper, co-author (Klinger) addresses vendors’ responses to enhancing consumer safeguards in respect of IoT devices.

Data breaches in the sextech industry reveal the potential for individuals to be stigmatised and/or discriminated against based on their sexual health data, influenced in part by societal norms and expectations surrounding (in)appropriate sexual conduct (Lupton Citation2015). However, little is known about the data privacy perceptions and sharing practices of self-trackers in sexual health communities. In the context of interdisciplinary concerns about data governance, surveillance, and commercial intrusions in the sextech industry (e.g. Stardust Citation2024), we conduct the first study to survey Lioness smart vibrator users on their data privacy perceptions and sharing practices, aiming to explore the less explored social context of self-tracking. The question this study asked was: what do users of The Lioness smart vibrator think about data sharing and data privacy? We combine this empirical research with industry perspectives from Liz Klinger, the co-founder of Smartbod Incorporated, makers of the Lioness, thereby responding to calls for more partnered research (rather than simply external critique), to prioritise the development of ethical and accountable sextech design, research and practices (Stardust, Albury, and Kennedy Citation2023).

Self-tracking technologies: previous research

There is an increasing body of work about the Quantified Self (QS), which encompasses self-tracking and monitoring practices, technologies, tools, meanings, and their consequences (Lupton Citation2021). Spanning various fields, including human-computer interaction (HCI), health, media studies, and sociology, this research focuses on self-optimisation strategies, the affordances of self-tracking technologies, and values surrounding self-tracking practices (see Lupton Citation2016; Lyall and Robards Citation2018; Rapp et al. Citation2015; Sharon and Zandbergen Citation2017). Self-tracking is often portrayed as beneficial, offering users self-knowledge and empowerment through data-driven insights (Williamson Citation2015), although concerns about data ownership, commercial invasiveness and data privacy remain (Lyall and Robards Citation2018).

The social context of self-tracking has lately emerged as an important consideration in research analysing user attitudes towards data sharing and privacy (Polonetsky and Tene Citation2013). Polonetsky and Tene argue that users prioritise the social value of self-tracking over discussions of analytics or third-party cookie sharing. Lupton (Citation2021) extends this argument by emphasising the interpersonal factors shaping self-tracking practices and user perceptions. Self-trackers in Lupton’s study view sharing personal data with close contacts as an intimate social experience, influencing their perceptions of data privacy and self-disclosure. Consequently, they feel more in control of their data, perceive its collection as personally beneficial, and are less cautious about potential harm. Lupton suggests these perspectives are influenced by affective forces within digitally mediated communities, challenging assumptions about data privacy and third-party data use. Her findings pertain to those sharing personal data, however, Lupton (Citation2021) calls for research that involves sensitive and potentially stigmatising data, to better understand the practices around, motivations for, and importance of self-tracking devices. This study answers that call and Lupton’s theorisations provide the building blocks for considering perceptions of digital privacy in an extreme and little researched ‘edge case’, that is, among users of a smart vibrator.

Although there is substantial work on self-tracking technologies, biofeedback devices used in sexual health and wellness contexts, including their users, uses and outcomes is relatively under-studied (see Döring and Pöschl Citation2018). Research is emerging in the intersecting domains of data studies and queer and feminist science and technology studies asking critical questions about the gendered politics of data tracking and aggregation in the domain of sex tech. Among the key issues highlighted in this body of work are the tensions between gendered cultures of altruism and the commercial imperatives of startup cultures (Flore and Pienaar Citation2020); data-driven understandings of ‘healthy sexuality’ (Burgess et al. Citation2022); the discursive construction and normalisation of specific user desires, identities, characteristics and behaviours (Hendl and Jansky Citation2022; Lupton Citation2015); the stigmatising potential of health data generated by self-tracking practices (Lupton Citation2021); the consequences of new forms of ‘publicness’ that networked connectivity and sextech engender (Sundén Citation2023); and the political economies of commercial sextech technologies and platforms that may lead to ‘more invasive forms of commercial surveillance’ (Wilson-Barnao and Collie Citation2018; Wynn et al. Citation2017). These critiques have in common an understanding that networked technologies and the ethos of sharing now characterising contemporary online interactions have redefined conventional ideas about intimacy and privacy in the digital age.

Data privacy is a focal point in discussions about self-tracking technologies due to the personal nature of the information they generate, potentially comprising intimate, sensitive, and stigmatising data (Lupton Citation2021). Moreover, all IoT devices are susceptible to hacking, amplifying privacy concerns. Self-tracking technologies, reliant on communication between servers, devices, and Bluetooth connections, obscure data sharing recipients. For instance, Wynn et al. (Citation2017) discovered vulnerabilities in Internet-connected smart vibrators, revealing device owner identities and posing risks of remote control and a potential sexual assault. They proposed enhanced security measures like secure token keys and data minimisation. While the authors use the term ‘smart vibrator’ to encompass remote control and biofeedback vibrators, users of the latter have distinct perspectives on data privacy and sharing, as this study will show.

Another concern is the lack of access users have to data they generate that can be used for commercial purposes or misappropriated by others including hackers (Sundén Citation2023; Wilson-Barnao and Collie Citation2018, 735). Based on their analysis of WeVibe marketing material and interviews with professionals in the Australian adult entertainment industry, Wilson-Barnao and Collie (Citation2018) found that commercialised regimes of measurement and control govern the use of sexual health and wellness devices and outweigh any benefit that may be derived from the technology. Users of smart vibrators undergo ‘intimate forms of surveillance’ as companies exploit and share the personal data produced by their bodies, rendering them passive and bypassing their conscious control (Wilson-Barnao and Collie Citation2018, 736). Despite this, the authors suggest that users may perceive a trade-off, as they gain access to new forms of knowledge and experience feelings of mastery and control over their bodies and pleasure centres (Wilson-Barnao and Collie Citation2018). While their argument raises important concerns about the need for industry-wide standards and policies in relation to data privacy, it also highlights the need to investigate user perceptions of self-tracking and to consult with industry on how these legitimate concerns are addressed, as we do in this paper.

Materials and methods

In designing this project, the Chief Investigator (BM) was interested in asking users of the Lioness how they used their biometric data, what it meant to them, and where and with whom they shared their experiences. Qualtrics software was used to administer the multiple-choice survey of 18 questions, some of which included free-response fields for additional feedback. There were no rewards or incentives to participate. As a research method, online surveys allow for participant anonymity, the targeting of a specific population of interest, are low cost to administer and have a rapid turnaround time (Lehdonvirta et al. Citation2021). The non-probability ‘river’ sampling method was used, wherein respondents were invited to follow a link to the survey posted on the Lioness social media profiles and in the Lioness app available on iOS and Android and available between 16 October and 12 November 2021. Users of the app gave their consent to participate in the survey by clicking an in-app slider. The posting of the survey link across domains and applications and with the endorsement of Lioness, was intended to capture a higher proportion of respondents who used the Lioness device. While unequal access to the Internet can lead to coverage bias in a participating sample (Lehdonvirta et al. Citation2021), the survey was designed to target users who could navigate the Internet-enabled features of the device with a view to investigating their perceptions of biofeedback technology. Non-probability online survey research has noted limitations such as the ‘selection effects’ that result from targeting a specific sub-population and problems of generalisability (Lehdonvirta et al. Citation2021). However, meaningful inferences can be drawn from data derived from non-probability online surveys (see Dawkins et al. Citation2013) and, in this case, about the self-recorded perceptions of ‘active’ Lioness users who use the device’s Internet connected features.

The project received ethics approval from the University of Technology Sydney, Australia (ETH20-5448). This followed a ‘high risk’ assessment and a rigorous review process that involved deliberation at two Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) meetings, out-of-session email discussion and lengthy application revisions. In negotiation with the HREC, and to minimise demographic data collection, questions about race, ethnicity, class, and disability did not form part of the survey. This is a noted limitation of the study given such identity markers would have yielded varying attitudes about data privacy and risk tolerance from those represented here.

In all, 192 responses were recorded, and participants were 18 years of age or older, took part anonymously, and voluntarily opted-in to the survey via a toggle in the Lioness app. The time commitment involved was estimated to be no more than 10 min, as outlined in the Participant Information Sheet posted on the Lioness website which also detailed the anonymity of participant data. The only identity markers collected in the survey were the age and gender identity of participants. This was to exclude those under 18 years of age and specifically target participants who identified as women, given that Lioness users tend to be young women between the ages of 25 and 35 years who have purchased the device for a particular type of pleasure.

In terms of gender distribution, the survey sample was largely representative, with the majority of participants identifying as female (77%), followed by male (15%), and non-binary (7%). Additionally, a majority (81%) reported owning a Lioness device. However, there were more older people participating in the survey (50> years = 28%) which was both surprising and a point of consideration in our analysis of the survey results. Though the geographic location of participants was not sought, they were likely based in the USA where the company was founded and the main consumer market for the device. The company does have distributors abroad, but those channels are less transparent about consumer profiling. While the company does not keep detailed information about their users, the device’s price point (USD $229) and collection of biofeedback data, would suggest the Lioness appeals to a more educated, affluent, and data-savvy (or at least data curious) user than the typical sex toy purchaser.

Users of the Lioness device are required to accept Lioness’s Terms of Service and consent to the Privacy Policy on their website and app. The Lioness Privacy Policy (n.d.) outlines the data SmartBod collects from users such as device activation details, account setup information, profile personalisation, browser activity (e.g. browser type, user operating system, URL page referrals, actions performed on the Lioness site) and the IP address of the user. None of this information was shared with the Chief Investigator of this research project, nor did she have access to any biometric data generated by Lioness users.

In the ‘Ways that you might share your data’ section of their Terms of Service, Lioness users are informed that they can choose to share their data with Lioness or a third party in the form of research surveys but that ‘Any PII [Personally Identifiable Information] you provide to Lioness (or supplied by you or Lioness to such third-party survey providers) in connection with these surveys will only be used in relation to that survey and as stated in this policy’ (Lioness, n.d.). By means of this statement, users are made aware of the data type, collection and sharing of Lioness user information as well as the voluntary nature of their participation in any Lioness initiated or third-party survey. By clicking a slider in the Lioness app, users can ‘proactively opt-in’ to participate in any medical or academic research conducted.

Findings

Practices and perceptions of intimate biometric data collection

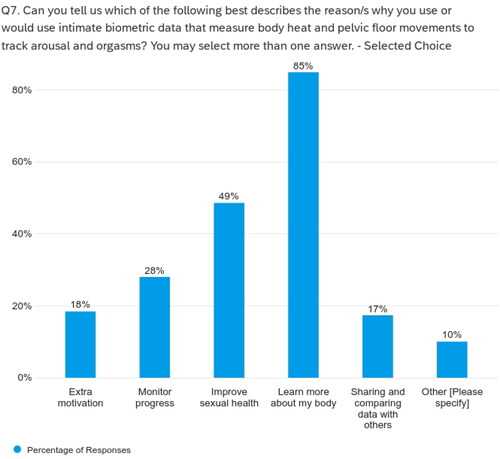

Most of those surveyed (86%) looked at the ‘intimate biometric data’ on their Lioness app which was defined for survey participants as data derived from body heat and pelvic floor movement enabling users to track arousal and orgasm (Q5). While the majority viewed their intimate biometric data ‘less than once a week’ (58%), more frequent users who viewed their data ‘two to six times a week’ (20%) comprised the second largest category (Q6). The principal motivation for participants generating intimate biometric data on their Lioness was educational, as evidenced by 152 respondents (85%) expressing a desire to ‘learn more about my body’ (Q7) – see , Q7. This trend was corroborated by responses to Q14 in which participants were asked to either agree or disagree with the statement that ‘Biometric data can help Lioness users better understand their bodies’ with 0% responding they ‘disagreed’. Instead, participants expressed either agreement (49%) or strong agreement (43%) with this claim. The second most cited reason for generating biometric data was to ‘improve sexual health’ (49%) followed by the desire to ‘monitor progress’ (28%). The question also included a free-form response section, enabling participants to expand on their views in comments such as ‘I just LOVE data’, ‘It’s kind of fun’, ‘Purely curious – am a data nerd’, ‘for the fun of it’ and to ‘share data to support the research community’ (Q7). These responses indicated a desire for self-optimisation as well as an enthusiasm for analysing biometric data among those surveyed.

Perceptions of data privacy and data sharing

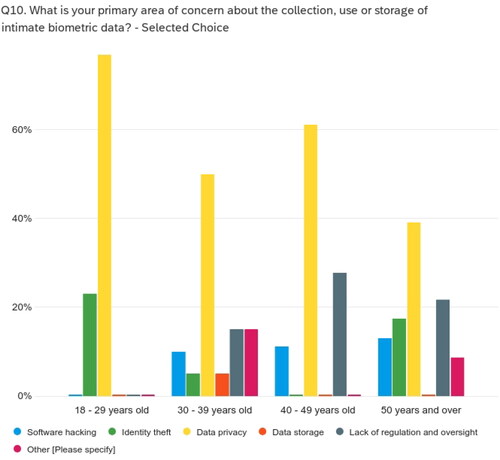

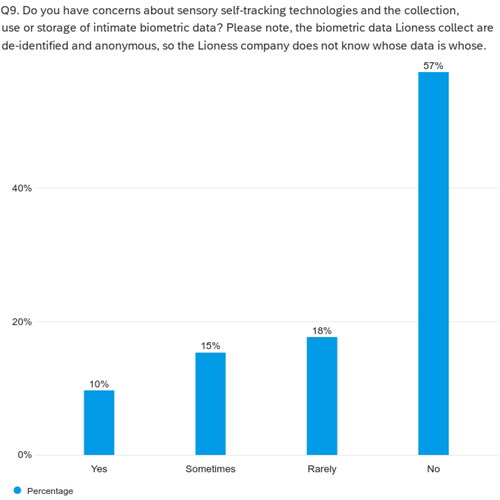

In response to whether they had concerns about the collection, use or storage of intimate biometric data (Q9), 101 respondents (57%) indicated they did not have any concerns, while 31 (18%) ‘rarely’ had concerns – see , Q9. There was little difference in the number of male and female-identifying respondents who had ‘no’ concerns about the collection, use or storage of biometric data (female = 55% and male = 54%), whereas those identifying as non-binary were more likely to answer ‘no’ (83%). All respondents who indicated ‘no’ skipped to Q11 in the survey. Those who indicated ‘yes’ (10%), ‘sometimes’ (15%) or ‘rarely’ (18%) in response to whether they were concerned about the collection, use or storage of intimate biometric data (Q9), were then asked about their primary area of concern (Q10). Of the 74 who responded, data privacy was the primary area of concern (54%) followed by a lack of regulation and oversight (18%) and identity theft (11%). Few in the selected cohort rated software hacking (9%) or data storage (1%) as a principal concern, but in three follow-up comments data storage was either directly mentioned (e.g. ‘Privacy, Storage, and no regulation/oversight if anything happens to the data’) or inferred in comments such as ‘all of the above’ referring to the range of concerns from which respondents could choose.

Figure 2. Concerns about sensory self-tracking technologies and the collection, use, or storage of intimate biometric data.

Segmented by age, those most concerned about data privacy were aged between 18 and 29 years (77%) and those least concerned about data privacy were 50 years or over (39%) – see , Q10. Whereas a ‘lack of regulation and oversight’ was of no concern for respondents in the youngest demographic (0%), it was the second most pressing concern for the oldest respondents in the cohort (22%).

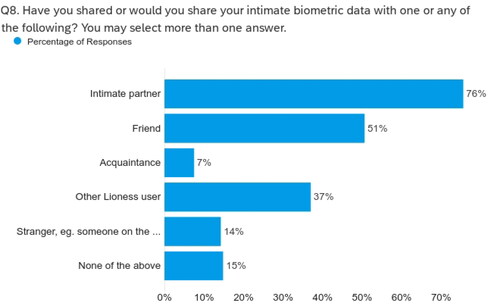

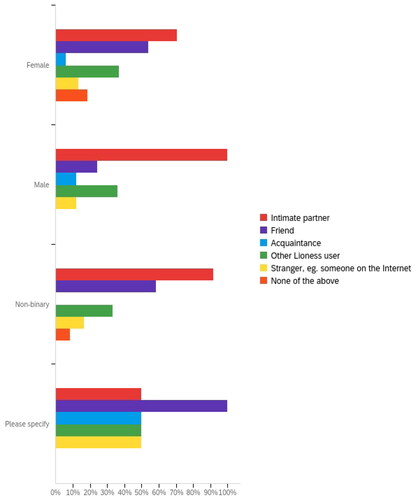

The three people with whom respondents indicated they have or would share their intimate biometric data (Q8) were an intimate partner (76%), followed by a friend (51%) and another ‘Lioness user’ (37%) – see , Q8.

When segmented by gender, all male-identifying respondents to Q8 in the survey (100%) indicated that they would share their intimate biometric data with an intimate partner, which compared similarly with 92% of those identifying as non-binary. Of the female-identifying respondents in the cohort, 71% had or would share their biometric data with an intimate partner and 54% were more likely to share or consider sharing these details with a friend (c.f. 24% male and 58% non-binary) – see , Q8. The gender of survey respondents had little to no bearing on whether they would share biometric data with another Lioness user (female = 37% male = 36% and non-binary= 33%). When asked with whom they would likely share their Lioness account details (Q11), respondents were divided between either an intimate partner (54%) or ‘none of the above’ (42%), the latter of which included an intimate partner, friend, acquaintance, other Lioness user or stranger.

Figure 5. People with whom respondents have shared or would share their intimate biometric data (segmented by gender).

The Lioness ‘Live View’ feature is an AI-enabled option on the Lioness vibrator that allows users to see their sexual response or arousal in real time. When asked in Q12 whether they had used the new feature, the majority indicated they had not (61%). Of the 69 participants who indicated ‘yes’, they were asked in Q13 with whom they had used the feature, and most had done so alone (67%) rather than with an intimate partner (33%), friend (0%) or stranger (0%).

Media usage and connectivity preferences

The most likely form of media respondents would use to talk about their Lioness was Reddit (19%) although the majority used the ‘other’ free text option (40%) to record a range of alternate platforms and media not included in the list of options such as Discord, Signal, iMessage, text message, Gmail, phone call, ‘in person’/’real life’, or to simply indicate that they did not talk about their Lioness using any carriage service (Q15). Others responded with ‘No social media ugh not appropriate especially as I am a professor and a mother’ and ‘I probably wouldn’t talk about it with anyone other than my husband and for a recent research study’ (Q15). Some indicated in the free-form response that they talk about their Lioness in ‘real life’, ‘face-to-face’, ‘in person’, ‘personal text or verbal conversations with those I trust’, or ‘friends, f2f (face-to-face)’ using the means of ‘Good old conversation’ (Q15). This finding supports arguments about the non-digital dimensions to self-tracking in the broader QS community, in particular, how data privacy and data sharing practices are entwined with users’ personal relationships (Lupton Citation2021).

However, when asked in Q16 whether they would be interested in connecting with other Lioness users to share advice, tips or information about their Lioness the majority answered either ‘yes’ (26%) or ‘maybe’ (43%). Of the 114 respondents who in Q17 ranked from 1 (most likely) to 7 (least likely) the different media they would use to connect with other Lioness users if given the opportunity, the majority answered the Lioness app discussion forum (n = 53) was the most likely outlet, followed by the Lioness website discussion forum (n = 19) and Facebook group (n = 17). In these responses, participants demonstrated a willingness to connect with other Lioness users in digitally mediated spaces owned and managed by SmartBod.

Sexual health research advocacy

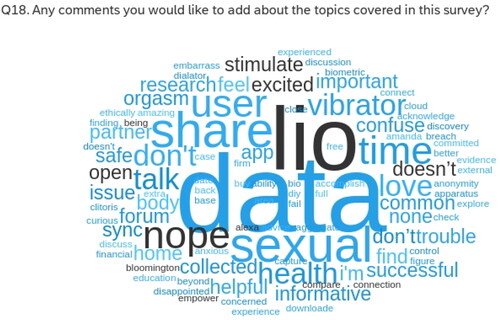

The final question (Q18) gave respondents the option to add any comments about the topics covered in the survey. Several respondents reported technical errors with the Live View feature, connection issues and data syncing, the price of the Lioness, and ‘Financial inaccesibilidades’ (sic), the lack of power driving the device (e.g. ‘not intense enough’), problems with time-outs, and the request for more detailed data in their orgasm graphs. The overwhelming majority mentioned ‘data’ in the context of the need for more sexual health research about women in comments such as ‘I’m excited to see what you can do with aggregated data to improve pleasure and find common trends’ and ‘Sexual health and empowerment backed by evidence-based data is very important!’ (see , Q18). In a similar vein, others applauded the research and opportunity to participate, e.g. ‘Glad to help promote intelligent open informative discussions’ and ‘Sex research in a lab is way more strange and vulnerable than this DIY at home with ability to compare notes’. A handful of respondents indicated they would like a ‘safe forum’ to talk about their biometric data with other users.

Discussion

This study investigated perceptions of data sharing and privacy among a group of self-trackers whose biofeedback data are considered among the most sensitive and potentially stigmatising. Consistent with the findings of research on self-trackers more generally (e.g. Lupton Citation2021), survey respondents reported feeling in control of their bodies, empowered by their biometric data, and perceived their self-tracking practices as contributing to both self-knowledge and a wider research community invested in female sexual health.

In a world marked by structural inequalities and growing commercial interest in personal data, the narrative of self-empowerment through health apps has been treated with some scepticism, particularly for the way in which it constructs certain bodies, desires and capacities as ‘normal’ (Hendl and Jansky Citation2022). It is also the case that these apps have the potential to provide individuals with valuable tools and resources for managing their health and well-being (see Williamson Citation2015, 140), and may improve health outcomes, e.g. through self-tracking that identifies changes in libido or sexual function over time and prompts an individual to seek medical advice or treatment. On a larger scale, aggregating and analysing self-tracked data may provide important insights into population health trends and disparities, which can inform public health interventions and policies aimed at reducing inequalities.

Study participants identified with a wider research community invested in female sexual health and were motivated by a desire to ‘Share data to support the research community’ (Q7), ‘Improve understanding of female sexuality’ (Q7) and ‘…help promote intelligent open informative discussions’ (Q18). Absent from these comments was a sense of the ‘passive’ rendering of Lioness users on whom ‘intimate forms of surveillance’ are enacted that bypass their ‘conscious control’ (Wilson-Barnao and Collie Citation2018, 736). Rather, respondents saw their data contributions as having the potential to pioneer advance in a biomedical research realm historically dominated by phallocentric perspectives (Grunt-Mejer Citation2022; Willis et al. Citation2018). Their comments about the need to ‘improve understanding of female sexuality’ acknowledge the lesser visibility and/or subordinate status assigned to female sexual pleasure within sexuality research, a criterion often assessed through the lens of the ‘coital imperative’ in which penile-vaginal intercourse is seen as the main or desired sexual activity (Grunt-Mejer Citation2022; Willis et al. Citation2018). One respondent even applauded the study by stating, ‘I know research is hard to accomplish in this area, keep up the amazing work!’ (Q18). That the Lioness survey respondents viewed themselves as sexual health pioneers accords with several studies that have found altruism is a key motivation for participation in qualitative research where the expectation of personal insight and benefits to others are more important than the costs associated with investing time and effort in the research process (see Dennis Citation2014; Watanabe et al. Citation2011). While donating data for sexological research may heighten the vulnerability of a user’s personal information through sharing, the potential therapeutic benefits and necessity to address the stigma surrounding women’s sexual health outweighed any associated risks among our survey participants. These altruistic motivations are even more pronounced in women’s sexual health research wherein gender is a ‘fundamental factor’ that defines and shapes health systems and their resulting outcomes (see Hay et al. Citation2019).

There are concerning instances of commercial invasiveness in the sex tech industry as exemplified in the WeVibe and Fitbit cases alluded to earlier. However, efforts to address data privacy issues are hampered by research approaches that lean on a binary mindset: the assumption that all companies exploit user data and all consumers are passive, duped or trapped in a Faustian bargain over their personal information. Rather than unconscious consumers or even research subjects, respondents in this study self-identified as research pioneers collaborating with domain experts on the production of knowledge in a form of praxis (Dennis Citation2014). In comments such as ‘‘I’m excited to see what you can do with aggregated data to improve pleasure and find common trends’ and ‘Sexual health and empowerment backed by evidence-based data is very important!’, respondents showed that finding answers to questions about their own embodied experiences of pleasure would likely help others. Their stated interest in aggregate data – in this case to identify trends for the advancement of female sexual health – contrasts with views expressed among self-trackers in general for whom technical questions to do with analytics, measurement, or third-party cookie sharing are less significant (Polonetsky and Tene Citation2013, 13).

In recent years, sex tech companies have made a concerted effort to address data privacy breaches, given their collection of sensitive and potentially stigmatising user data (see Ley and Rambukkana Citation2021). In some cases, manufacturers have opted to exceed the minimum legal requirements to build trust among consumers. This is also ‘smart business’ as Klinger argues, because the laws that protect the data privacy of consumers may vary both nationally and internationally. For example, within the European Union (EU), the General Data Protection Regulation Citation2016 (GDPR) mandates the fundamental protection of personal data including health information and Article 9 prohibits the sharing of such information unless the user explicitly consents. Explicit consent is defined in Recital 32 of the GDPR as ‘…a clear affirmative act establishing a freely given, specific, informed and unambiguous indication of the data subject’s agreement to the processing of personal data relating to him or her, such as by a written statement, including by electronic means, or an oral statement’, and adds that ‘Silence, pre-ticked boxes or inactivity should not therefore constitute consent’ (GDPR Citation2016). For Lioness, ‘explicit consent’ must be preceded by communication that is clear, transparent, and accessible, and does not require consumers to wade through impenetrable terms of service. The company’s policy is to adopt the lessons of good quality sex education in which consent is both informed and enthusiastically given.

While consumers in EU member states are afforded the same data privacy safeguards, in the USA legislation varies across state jurisdictions. California – where SmartBod Incorporated DBA Lioness is based – has one of the strictest data privacy laws in the country after the passing of the California Consumer Privacy Act of 2018 or CCPA (State of California Department of Justice Office of the Attorney General Citation2024). The law mandates privacy rights for California consumers such as the right to know what personal information a business collects about them and to whom it is sold or shared; the right to delete personal information collected by a business; the right to opt-out of the sale or sharing of their personal information; and the right to not suffer retaliatory or discriminatory treatment in the exercise of data privacy rights. In November 2020, the act was amended to add new privacy protections for consumers including the right to correct inaccurate information and the right to limit the use and disclosure of sensitive personal information collected. Users of the Lioness can find information about the company’s data collection and storage practices on their website including the use of anonymised and aggregated user data to track trends. As Klinger describes, Lioness encrypts their databases, employs host authentication and security servers to store their user lists, anonymises user data and uses the ‘one-way hashed’ method of transforming personal information into a fixed-size string of characters. Combined with Lioness employing a certified, third-party security firm to handle authentication and store user identity, which removes the ability to compare user identities or reverse the hash, it is practically impossible to retrieve the original data input of users. The degree of data privacy protection Lioness affords users constitutes industry best practice according to a review by the Mozilla Foundation – a non-profit organisation promoting openness, innovation and participation on the Internet (Mozilla Foundation Citation2018).

The fact that the majority of survey respondents did not have any concerns (57%) or ‘rarely’ had concerns (18%) about the privacy of their data (Q9), may be partially attributed to their familiarity with the extra security measures detailed on The Lioness website, coupled with their geographic location, predominantly North America, which aligns with the company’s primary consumer base. In regions of North America where sexual attitudes are more liberal (excluding jurisdictions such as Texas), the use of sex tech devices may carry less risk; however, in other parts of the world, such activities could be deemed illegal or considered pornographic, potentially leading to criminal prosecution. The variability with which users may view their data as sensitive or potentially stigmatising is an important consideration in regulatory debates about sextech. A more useful approach would be to argue that user evaluations of risk exist along a continuum, are influenced by cultural factors, and are contingent upon whether the user resides in a jurisdiction that criminalises or stigmatises sexual behaviours such as adultery, masturbation, or sex work.

There were generational differences in data privacy perceptions within the study cohort. Those most concerned about data privacy were aged between 18 and 29 years (77%) and those least concerned about data privacy were aged 50 years or over (39%). Arguably, younger generations are more digitally literate and, as frequent users of social media and other online platforms, have a greater awareness of and sensitivity to privacy issues associated with these technologies. The generational gap may also indicate a shift in attitudes over time. Younger individuals may be more cautious and critical of data practices, while older individuals may have different perspectives shaped by their experiences with evolving technologies and societal norms. Contrastingly, respondents aged 50 years or over were more concerned about a ‘lack of regulation and oversight’ in the collection, use and storage of biometric data than the youngest survey participants. While older individuals may place more trust in regulatory frameworks to protect their data, policymakers and regulators should take into account age-related variations in privacy concerns when developing and implementing data protection policies.

Gender was a factor in perceptions of data sharing and data privacy among the Lioness users surveyed. Female-identifying respondents were more likely to share biometric data with a friend compared to male participants. This may indicate different norms or expectations regarding privacy within friendships across genders. That all male-identifying respondents were willing to share their intimate biometric data with a partner may suggest a higher level of trust or a different perception of privacy within that group. These findings illustrate how data sharing practices within self-tracking sexual health communities are influenced by gendered relationship dynamics, such as the lower levels of intimacy observed in male friendships (Machin and Dunbar Citation2013). They also demonstrate how self-tracking technologies can shape different subjectivities and embodiments (Lupton Citation2013).

Of the media platforms respondents used to share their data, Reddit (19%) was the preferred option among those provided in the survey, likely because of the more anonymous interactions facilitated on the site and lower risk perception compared to mainstream social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter (Nyblom, Wangen, and Gkioulos Citation2020). That the majority used the ‘other’ free text option (40%) to record a range of alternate platforms and venues for sharing their data such as Discord, Signal, iMessage, text message, Gmail, phone call, and ‘in person/real life’ (Q15), reflects a tendency towards multitasking media in everyday life (Deuze Citation2012), even though the data shared may be seen as more sensitive or potentially stigmatising.

The lack of concern about data privacy among survey respondents points to the complex ideas about with whom and how data are shared within digital communities. As Lupton (Citation2021) has pointed out, offline relationships shape conceptions of data sharing and privacy and this was true of the Lioness users surveyed who indicated they would share their data with close, in-person connections (Q8) such as an intimate partner (76%), or a friend (51%). These are examples of the more-than-digital and relational dimensions to self-tracking that also inform the broader population of self-trackers (Lupton Citation2021). Given 37% of respondents indicated they would share their biometric data with another Lioness user, there are strong communal ties between them and digital ‘pride’ (Lioness n.d.) in a ready example of ‘brand community identification’ (Valmohammadi, Taraz, and Mehdikhani Citation2023). While beyond the scope of the present study, research of Lioness’ corporate branding and the ways in which users interact as collectively on the company’s social networks would yield interesting insights and may yet be another example of the relational forces shaping user perceptions of self-tracking (see Lupton Citation2021).

Conclusion

This study responds to calls for more industry-partnered research and empirical data on the data sharing and privacy perceptions of an under-researched sexual health population, drawing on insights from the co-founder of The Lioness smart vibrator and a survey of users. We found that Lioness users are motivated by both individual and altruistic goals: to learn more about their bodies and contribute to research that leads to better sexual health outcomes for all.

But more than research ‘subjects’, respondents were self-styled ‘pioneers’ striving for better sexual health outcomes in a historically phallocentric scientific research community. Altruism emerged as a defining aspect of their advocacy for sexual health within a medical domain they perceive as gender-biased. Participants’ interest in, and for some, enthusiasm for, Lioness’ use of aggregated data to identify trends and advance sexual health research beset by restrictive gender norms and expectations, challenges taken-for-granted assumptions about the way self-trackers should feel about their data sharing and privacy, particularly those generating potentially stigmatising or sensitive data. We argue for a more nuanced approach to understanding privacy perceptions in self-tracking sexual health communities that takes into account the non-digital forces (Lupton Citation2021) shaping the motivations of users. As this study found, whereas data sharing practices differed by gender, data privacy perceptions differed by age and contributed to an individual’s risk evaluation. These differing results underscore the importance of incorporating demographic factors into regulatory and policy frameworks addressing data privacy.

While a key motivation for women’s participation in sexual health research is to address its disproportionate focus on heterosexual men, understanding how the long and problematic history of biomedical research involving racial minorities affects their participation is a pressing area for future research (see Chinn, Martin, and Redmond Citation2021), especially in studies of self-tracking sexual health communities. While White women may participate to address the gender health gap, Black women and other racial minority women may be less motivated due to medical mistrust and their unique historical and contemporary experiences (Chinn, Martin, and Redmond Citation2021). Future research on sexual health communities should explore such lines of inquiry, finding productive comparisons at the intersection of gender, race and sexuality.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the anonymous reviewers for their considered and helpful feedback, the Lioness users who generously gave their time to participate in the survey and Alan Davison from the University of Technology Sydney, Australia, who supported the sabbatical that enabled this research.

Disclosure statement

In accordance with Taylor & Francis policy and my ethical obligation as a researcher, I (BM) am reporting a conflict of interest in having conducted this research with Smartbod Incorporated, a company that might benefit or be disadvantaged by the published findings. While no funding was received from Smartbod Incorporated, I was given a sample Lioness device as part of the research and have disclosed these interests fully to Taylor & Francis, with an approved plan in place for managing any potential conflicts.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Albury, K., Z. Stardust, and J. Sundén. 2023. “Queer and Feminist Reflections on Sextech.” Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters 31 (4): 2246751. https://doi.org/10.1080/26410397.2023.2246751.

- Burgess, J., K. Albury, A. McCosker, and R. Wilken. 2022. Everyday Data Cultures. Newark: Polity Press.

- Chinn, J. J., I. K. Martin, and N. Redmond. 2021. “Health Equity Among Black Women in the United States.” Journal of Women’s Health 30 (2): 212–219. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2020.8868.

- Dawkins, L., J. Turner, A. Roberts, and K. Soar. 2013. “Vaping’ Profiles and Preferences: An Online Survey of Electronic Cigarette Users: Vaping Profiles and Preferences.” Addiction 108 (6): 1115–1125. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.12150.

- de Freytas-Tamura, K. 2017. “Maker of ‘Smart’ Vibrators Settles Data Collection Lawsuit for $3.75 Million.” The New York Times, March 14, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/14/technology/we-vibe-vibrator-lawsuit-spying.html

- Dennis, B. K. 2014. “Understanding Participant Experiences: Reflections of a Novice Research Participant.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 13 (1): 395–410. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940691401300121.

- Deuze, M. 2012. Media Life. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Döring, N., and S. Pöschl. 2018. “Sex Toys, Sex Dolls, Sex Robots: Our Under Researched Bedfellows.” Sexologies 27 (3): E51–E55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sexol.2018.05.009.

- Flore, J., and K. Pienaar. 2020. “Data-driven Intimacy: Emerging Technologies in the (Re) Making of Sexual Subjects and ‘Healthy’ Sexuality.” Health Sociology Review 29 (3): 279–293. https://doi.org/10.1080/14461242.2020.1803101.

- General Data Protection Regulation. 2016. European Union. Recital 32 Conditions for Consent. https://gdpr-info.eu/recitals/no-32/

- Grunt-Mejer, K. 2022. “The History of the Medicalization of Rapid Ejaculation—A Reflection of the Rising Importance of Female Pleasure in a Phallocentric World.” Psychology & Sexuality 13 (3): 565–582. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2021.1888312.

- Hay, K., L. McDougal, V. Percival, S. Henry, J. Klugman, H. Wurie, J. Raven, F. Shabalala, R. Fielding-Miller, A. Dey, et al. 2019. “Disrupting Gender Norms in Health Systems: Making the Case for Change." 2019.” Lancet 393 (10190): 2535–2549. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30648-8.

- Hendl, T., and B. Jansky. 2022. “Tales of Self-Empowerment Through Digital Health Technologies: A Closer Look at ‘Femtech’.” Review of Social Economy 80 (1): 29–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/00346764.2021.2018027.

- Internet Society. 2018. May 22. Internet of Things Trust Framework v2.5. https://www.internetsociety.org/resources/doc/2018/iot-trust-framework-v2-5/

- Lehdonvirta, V., A. Oksanen, P. Räsänen, and G. Blank. 2021. “Social Media, Web, and Panel Surveys: Using Non-Probability Samples in Social and Policy Research.” Policy & Internet 13 (1): 134–155. https://doi.org/10.1002/poi3.238.

- Ley, M., and N. Rambukkana. 2021. “Touching at a Distance: Digital Intimacies, Haptic Platforms, and the Ethics of Consent.” Science and Engineering Ethics 27 (5): 63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-021-00338-1.

- Lioness. n.d. Privacy Policy. Lioness. https://lioness.io/pages/privacy-policy

- Lupton, D. 2013. “Quantifying the body: monitoring and measuring health in the age of mHealth technologies.” Critical Public Health 23 (4): 393–403. https://doi.org/10.1080/09581596.2013.794931.

- Lupton, D. 2015. “Quantified Sex: A Critical Analysis of Sexual and Reproductive Self-Tracking Using Apps.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 17 (4): 440–453. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2014.920528.

- Lupton, D. 2016. The Quantified Self: A Sociology of Self-Tracking. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Lupton, D. 2021. “Sharing Is Caring’: Australian Self-Trackers’ Concepts and Practices of Personal Data Sharing and Privacy.” Frontiers in Digital Health 3: 649275. https://doi.org/10.3389/fdgth.2021.649275.

- Lyall, B., and B. Robards. 2018. “Tool, Toy and Tutor: Subjective Experiences of Digital Self-Tracking.” Journal of Sociology 54 (1): 108–124. https://doi.org/10.1177/1440783317722854.

- Machin, A., and R. Dunbar. 2013. “Sex and Gender as Factors in Romantic Partnerships and Best Friendships.” Journal of Relationships Research 4: e8. https://doi.org/10.1017/jrr.2013.8.

- Mozilla Foundation. 2018. Lioness Vibrator. Product review. Privacy Not Included Guide. https://foundation.mozilla.org/en/privacynotincluded/products/lioness-vibrator/

- Mozilla. 2018. Minimum Standards for Tackling IoT Security. Medium. https://medium.com/read-write-participate/minimum-standards-for-tackling-iot-security-70f90b37f2d5

- Nyblom, P., G. Wangen, and V. Gkioulos. 2020. “Risk Perceptions on Social Media Use in Norway.” Future Internet 12 (12): 211. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi12120211.

- Pfaus, J., D. Hartmann, E. Wood, J. Wang, and E. Klinger. 2022. “Women’s Orgasms Determined by Autodetection of Pelvic Floor Muscle Contractions Using the Lioness ‘Smart’ Vibrator.” The Journal of Sexual Medicine 19 (Suppl 3): S2–S3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2022.05.011.

- Polonetsky, J., and O. Tene. 2013. “Privacy and Big Data: Making Ends Meet.” Stanford Law Review Online. http://www.stanfordlawreview.org/online/privacy-and-big-data/privacy-andbig-data.

- Rapp, A., F. Cena, J. Kay, B. Kummerfeld, F. Hopfgartner, T. Plumbaum, J. E. Larsen, D. A. Epstein, and R. Gouveia. 2015. “New Frontiers of Quantified Self: Finding New Ways for Engaging Users in Collecting and Using Personal Data.” Adjunct Proceedings of the 2015 ACM International Joint Conference on Pervasive and Ubiquitous Computing and Proceedings of the 2015 ACM International Symposium on Wearable Computers, 969–972.

- Sharon, T., and D. Zandbergen. 2017. “From Data Fetishism to Quantifying Selves: Self-Tracking Practices and the Other Values of Data.” New Media & Society 19 (11): 1695–1709. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444816636090.

- Stanton, A. M., and N. Kirakosian. 2020. “The Role of Biofeedback in the Treatment of Sexual Dysfunction.” Current Sexual Health Reports 12 (2): 49–55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11930-020-00257-5.

- Stardust, Z. 2024. “Sex Tech in an Age of Surveillance Capitalism: Design, Data and Governance.” In Routledge Handbook of Sexuality, Gender, Health and Rights, edited by P. Aggleton, R. Cover, C. Logie, E. C. Newman, and R. Parker, 448–458. 2nd ed. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

- Stardust, Z., K. Albury, and J. Kennedy. 2023. “Sex Tech Entrepreneurs: Governing Intimate Data in Start-Up Culture.” New Media & Society 0: 146144482311644. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448231164408.

- State of California Department of Justice Office of the Attorney General. 2024. California Consumer Privacy Act of 2018 or CCPA. https://oag.ca.gov/privacy/ccpa.

- Sundén, J. 2023. “Play, Secrecy and Consent: Theorizing Privacy Breaches and Sensitive Data in the World of Networked Sex Toys.” Sexualities 26 (8): 926–940. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460720957578.

- Valmohammadi, C., R. Taraz, and R. Mehdikhani. 2023. “The Effects of Brand Community Identification on Consumer Behavior in Online Brand Communities.” Journal of Internet Commerce 22 (1): 74–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332861.2021.2011597.

- Watanabe, M., Y. Inoue, C. Chang, H. Hong, I. Kobayashi, S. Suzuki, and K. Muto. 2011. “For What Am I Participating? The Need for Communication After Receiving Consent from Biobanking Project Participants: Experience in Japan.” Journal of Human Genetics 56 (5): 358–363. https://doi.org/10.1038/jhg.2011.19.

- Williamson, B. 2015. “Algorithmic Skin: Health-Tracking Technologies, Personal Analytics and the Biopedagogies of Digitized Health and Physical Education.” Sport, Education and Society 20 (1): 133–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2014.962494.

- Willis, M., K. N. Jozkowski, W.-J. Lo, and S. A. Sanders. 2018. “Are Women’s Orgasms Hindered by Phallocentric Imperatives?” Archives of Sexual Behavior 47 (6): 1565–1576. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-018-1149-z.

- Wilson-Barnao, C., and N. Collie. 2018. “The Droning of Intimacy: Bodies, Data, and Sensory Devices.” Continuum 32 (6): 733–744. https://doi.org/10.1080/10304312.2018.1525922.

- Wynn, M., K. Tillotson, R. Kao, A. Calderon, A. F. Murillo, J. Camargo, R. Mantilla, B. Rangel, A. Cardenas, and S. Rueda. 2017. “Sexual Intimacy in the Age of Smart Devices: Are We Practicing Safe IoT?” In Proceedings of the 2017 Workshop on Internet of Things Security and Privacy (IoTS&P ‘17), 25–30. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/ezproxy.lib.uts.edu.au/10.1145/3139937.3139942.