ABSTRACT

How do older adults mobilize social support, with and without digital media? To investigate this, we focus on older adults 65+ residing in the Toronto locality of East York, using 42 interviews lasting about 90 minutes done in 2013–2014. We find that digital media help in mobilizing social support as well as maintaining and strengthening existing relationships with geographically near and distant contacts. This is especially important for those individuals (and their network members) who have limited mobility. Once older adults start using digital media, they become routinely incorporated into their lives, used in conjunction with the telephone to maintain existing relationships but not to develop new ones. Contradicting fears that digital media are inadequate for meaningful relational contact, we found that these older adults considered social support exchanged via digital media to be real support that cannot be dismissed as token. Older adults especially used and valued digital media for companionship. They also used them for coordination, maintaining ties, and casual conversations. Email was used more with friends than relatives; some Skype was used with close family ties. Our research suggests that policy efforts need to emphasize the strengthening of existing networks rather than the establishment of interventions that are outside of older adults’ existing ties. Our findings also show that learning how to master technology is in itself a form of social support that provides opportunities to strengthen the networks of older adults.

Introduction

Most North American adults are now online, with 59% of Americans 65+ using the internet in 2016 (Anderson & Perrin, Citation2016). It has taken a longer time for this age group to join the digital milieu, having grown accustomed to using non-digital means to communicate and seek information (Fortunati, Citationin press; Yuan, Hussain, Hales, & Cotten, Citation2016). However, it was inevitable that older adults would also go online. Digital media have become omnipresent and easier to use, via the internet, tablets, and smartphones. Being online has become compelling, as much information, goods, services, and people are most conveniently (and often exclusively) available online. Moreover, an age group is not a static category: many older adults grew up using digital media, and there is no reason for them to stop when they turn 65. While they may lose some ties with workmates as they retire, they gain more leisure time to connect with friends and relatives. Yet older adults are the least-studied age group with respect to their digital media needs and preferences, and scholars know little about variations in their use (Fortunati, Citationin press; Yuan et al., Citation2016).

If resources flowing through digital media provide support for younger adults (Ellison, Steinfield, & Lampe, Citation2007; Hampton, Rainie, Lu, Shin, & Purcell, Citation2015), shouldn’t this also be true for older adults? We contribute to the growing body of work examining older adults’ social support mobilization (Bradley & Poppen, Citation2003; Bromell & Cagney, Citation2014; Cotten, Anderson, & McCullough, Citation2013; Gray, Citation2009; Requena, Citation2013; Smith, Citation2014; Smyth, Siriwardhana, Hotopf, & Hatch, Citation2015). We show how older adults exchange different types of social support and the role of digital media in these exchanges. Our research suggests that efforts need to be placed in strengthening existing networks rather than interventions that are beyond older adults’ existing ties. Once online, older adults do what other North Americans do: they use the internet for information, to make arrangements, and to connect with friends and relatives. Their interactions with friends and relatives via digital media provide a good deal of social support, which we found to be particularly important for older adults with limited mobility themselves or their network members.

The research we present shows how older adults integrate in-person meetings, phone calls, and digital media to keep in contact with friends, relatives, and neighbors. Similar to younger adults, older adults find digital media to be handy, low-cost, and visually rich. Once older adults start to use digital media, the technology becomes incorporated as a routine part of their lives. Relying primarily on email, and to a lesser extent, Facebook and Skype, older adults use digital media to maintain and to strengthen existing social ties and to facilitate both micro-communication and support mobilization. Contradicting fears that digital media is inadequate for meaningful contact (Turkle, Citation2011), the participants consider social support exchanged via digital media to be as real as any other kind of support. Yet, their preference is for one-to-one, more intimate ways of interaction rather than for many-to-many broadcast media (Tian & Menchik, Citation2016).

Our research analyzing the online behavior of older adults is part of the fourth East York project, situating the digital involvement of Toronto adults in the context of their everyday lives (Wellman, Citation1979; Wellman et al., Citation2006; Wellman & Wortley, Citation1990). We focus here on 42 non-frail, English-speaking adults aged 65+ residing in the Toronto locality of East York, 24 (57%) of whom use digital media to communicate. As best as we know, this is the first field study reporting how older adults mobilize social support via digital media. We address three research questions here:

RQ1: What types of social support do older adults exchange?

RQ2: How do digital media intersect with traditional means of providing social support?

RQ3: In what ways do older adults use digital media for exchanging social support?

Social support and digital media in the lives of older adults

Two streams of research inform the present study: the role of digital media in social support mobilization, and the interplay between well-being and digital media in the lives of older adults.

Much scholarly understanding of social support has focused on the benefits of social support for health, life expectancy, and happiness. Research has also shown the multidimensional nature of support (Hlebec & Kogovšek, Citation2013; Williams, Barclay, & Schmied, Citation2004; Xia et al., Citation2012). The second East York study, conducted in 1979, was influential in this. It supplemented the initial quantitative findings of the first East York study with lengthy in-depth interviews with a subset of 33 of the respondents originally interviewed in 1968. Using factor and cluster analysis, it pioneered the disaggregation of ‘social support’ into five different types, finding that network members in different roles tended to specialize in what they give. For example, siblings and friends provided emotional aid (Wellman & Wortley, Citation1990). The interviews also showed the more voluntary nature of telephone contact than in-person contact (Wellman & Tindall, Citation1993).

Other research has focused on the ‘triple revolution’ of the turn to social networks, the pervasiveness of the internet, and handy mobile phones influencing how individuals are connected (Rainie & Wellman, Citation2012). The third East York study, conducted in 2004–2005, was the first to delve into the role of the internet in facilitating the connected lives of residents. This hybrid study, combining a survey of a random-sample of 350 adult residents and a follow-up interview with 25% of them, showed that the internet ‒ principally email in those days ‒ provided connectivity between in-person encounters, allowing friends, relatives, and household members to maintain and enrich their relationships (Mok, Wellman, & Carrasco, Citation2010; Wellman et al., Citation2006).

Juxtaposing the social support and the triple revolution research suggests that digital media can serve as a bridge to obtaining social support. Email, Facebook, texting, and video chat allow network members to stay in contact with fewer constraints on distance (Rainie & Wellman, Citation2012). Digital media can provide continuing contact with strong and weak ties, potentially able to supply a variety of help. They also facilitate self-disclosure that lets network members know that support is needed (Bruggeman, Citation2016; Hampton et al., Citation2015; Rains, Brunner, & Oman, Citation2014; Siibak & Tamme, Citation2013). There is some indication that digital media use is organized both by gender, with women maintaining more contact than men, and intergenerationally, with younger generations supporting older adults (Fortunati, Citationin press).

Our concern here is the interplay of digital media and social support for older adults. The decrease in the death rate of older adults and the increase in life expectancy has resulted in a greater proportion of the population comprising older adults, a shift unprecedented in history, pervasive globally, enduring over time, and with profound economic, social, and health implications. For example, 13.7% of Canadians were 65+ in 2015, up from 7.7% in 1956 (Statistics Canada, Citation2016). To look at this issue in another way, social isolation is associated with numerous negative outcomes, including increased mortality, depression, poor physical health, and susceptibility to dementia (Cornwell & Waite, Citation2009; Dickens, Richards, Greaves, & Campbell, Citation2011; Fratiglioni, Wang, Ericsson, Maytan, & Winblad, Citation2000; Holt-Lunstad, Smith, Layton, & Brayne, Citation2010). Older adults can be in a stage of their lives where they experience loneliness and depression due to changes in their physical, social, and economic situations (Dickens et al., Citation2011; Iliffe et al., Citation2007; National Institute of Mental Health, Citation2009).

How does older age affect the exchange of social support? Although there is a loss of coworkers, previous East York research has shown that they usually are a minor source of support (Wellman et al., Citation2006; Wellman & Tindall, Citation1993). Revealing important gender differences, older women ‘have larger networks and receive supports from multiple sources, while men tend to rely on their spouses exclusively’ (Antonucci & Akiyama, Citation1987, p. 737). More importantly, network members can get frail, disconnected, and die, reducing the number of ties who are available to be supportive for both women and men. Residential moves from single-family homes to apartments may disconnect existing neighboring ties but make new ties available. Yet, older adults remain engaged with diverse network members (Bromell & Cagney, Citation2014; Cotten et al., Citation2013; Gray, Citation2009; Requena, Citation2013; Smyth et al., Citation2015), and digital media may be especially important for those older adults who have limited capability to visit their friends and relatives in person.

Digital media have the potential to help older adults overcome social isolation and feelings of loneliness. Recent research has found that older adults have more actively started to use technology to connect with others (Cotten et al., Citation2013; Zickuhr & Madden, Citation2012). One concern often raised is that some older adults may not have the ability to employ digital media to obtain the needed social support (Schreurs, Quan-Haase, & Martin, Citationin press; Smith, Citation2014). Their lack of connection can come from a lack of skill or perception of how digital media can be useful (Wright, Citation2000). Nevertheless, once older adults start to use digital media, the technology may become a routine part of their lives (Bradley & Poppen, Citation2003; Quan-Haase, Beermann, Martin, Miller, & Wellman, Citation2016; Zickuhr & Madden, Citation2012). The older adults in these studies report that the internet makes it easier to reach people, enables them to stay in touch, allows them to meet new people, increases the quality and quantity of communication with others, and makes them feel more connected to family and friends. Some research suggests that older adults are especially apt to use the internet for companionship rather than to exchange other kinds of support (Wright, Citation2000).

Methods

East York

This is the initial paper from the fourth wave (since 1968) of research in Toronto’s locality of East York (Wellman, Citation1979; Wellman et al., Citation2006; Wellman & Wortley, Citation1990). East York is a former autonomous ‘borough’ that is now consolidated into the larger City of Toronto, the fourth largest metropolitan area in North America. East York’s population has remained at slightly more than 100,000 even as the Greater Toronto Area has increased 64%, from 3.7 million in 1986 to 6.1 million in 2011. East York’s population consists of working-class and middle-class small families and single adults living in modest homes and apartments (Quan-Haase et al., Citation2016). Transit options and the street grid make travel easy within the city of Toronto.

Data collection

Our sampling frame came from a randomly sampled set of 2321 East York households provided by the Research House list-services company. The sample skewed older, in keeping with East York’s current demographics. From this list, we randomly contacted 304 persons by letter: 101 agreed to participate; a response rate of 34%. Participants received a letter of information and invitation (approved by the University of Toronto's Research Ethics Board) outlining the purpose of the study, as well as a $50 coffee shop gift card. Potential participants were then telephoned for an interview appointment. The difficulty in accessing apartment buildings and the landline-only nature of the sampling list skewed our final sample to include a large proportion of older adults. Moreover, older adults were more likely to accept invitations to be interviewed. This resulted in a mean age of our overall sample as 59.5.

Our analysis focuses on the subset of 42 participants who were older adults, aged 65–93, with a median age of 71. About half (23/42) were women, and more than 70% were older than 70 years. Most were retired from paid work, while remaining actively engaged with friends, relatives, and other matters (see ). Most were ethnically British-Canadian; the diversity of the other participants precluded further analysis of cultural variations.

Table 1. Demographics of participants.

Our semi-structured interviews, conducted in 2013–2014 by social science students, lasted about 1.5 hours each. The questions and probes in our interview schedule covered participants’ technology use, social networks, and views about privacy. All interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim, with one-third checked for accuracy by a research assistant neither involved in the data collection nor the transcription.

Data analysis

Four tenets of grounded theory guided our analysis: (1) open coding that remains close to the data; (2) memo writing and reflection; (3) use of the constant comparative method; and (4) saturation of codes. As we are building upon past East York research and frameworks of social support, we followed Corbin and Strauss (Citation2014) in their suggestion that in grounded theory a previously identified framework ‘can provide insight, direction, and an initial list of concepts to use as a starting point for developing new concepts and expanding old ones’ (p. 52). Two researchers engaged in open coding of 15 transcripts and wrote extensive memos about each of the themes that emerged. Three additional coders each coded the remaining data, meeting frequently and memoing extensively. Through discussions with the entire team, we continually adjusted and refined the coding scheme. Once this scheme was in place, three additional coders coded the remaining data, meeting frequently to ensure consistency. In this second stage, we used additional memoing in conjunction with the constant comparative method (Charmaz, Citation2006; Glaser & Strauss, Citation1967). We stopped when we reached saturation for each theme included in the final coding scheme ‒ that is, we could not gain any additional insights from further coding.

Findings

Over half (24/42) of the participants reported using digital media to connect with friends and relatives. Younger participants were more likely to rely on digital media: those aged 65 − 69 (53%) used digital media more for support exchange compared to those in their 70s (44%) and 80+ (18%). Women were more apt to use digital media to maintain their networks: 61% as compared to 53% of men (see also Fortunati, Citationin press). Most of the non-users relied on their partners, children, grandchildren, friends, and neighbors to find out information for them and, at times, to communicate with others on their behalf (see also Kennedy, Nansen, Arnold, Wilken, & Gibbs, Citation2015).

What types of social support do older adults exchange? (RQ1)

To allow for comparisons while remaining open to new insights, we used past frameworks developed in earlier East York studies to inform our coding (Wellman, Citation1979; Wellman et al., Citation2006; Wellman & Wortley, Citation1990). The five types of social support found in previous studies ‒ emotional aid, small services, large services, financial aid, and companionship ‒ are all evident in our interviews. The percentage of those exchanging each kind of support is in the same order as we found in pre-internet days (Wellman & Wortley, Citation1990).

Giving and receiving support continued to be distinct types of support exchange, with East Yorkers feeling blessed that they gave more support than they received (Acts 20:35) (see ).

Table 2. Types of social support exchanged.

All participants stressed the importance of companionship for their well-being and considered receiving it as an important component of tie closeness. Indeed, companionship was the only type of support that more participants reported receiving (60%) than giving (52%). As Paul told us:

Somebody just wants to talk one evening and calls you up. You might not want to, particularly, you might want to do something else, but you’ll listen … Give and take, that’s what friends are for. (P84, 81, M) [Participant#, Age, Gender]

Consistent with previous research (Yuan et al., Citation2016), participants received companionship more from friends than relatives and said that they favored these social exchanges to those with relatives. Many of these older adults lived alone and depended on the in-person companionship provided by their friends, such as dining, doing like-minded activities, or going on a road trip. But they often made arrangements for these get-togethers by email or phone.

In contrast to ongoing friendships, companionship with kin mainly happened over holidays, birthdays, and other celebrations. Such companionship sometimes became a burden for some older adults. When asked how the family visits would be arranged, Sutapa said it was a mixture of phoning and actual visiting.

They would call me up, but it’s interesting, I think they just expect that I know that I’m invited, because sometimes it gets right up to the day before. It’s usually quite a late phone call, but as I say, I think they think that I just understand that I’m going there. (P77, 76, W)

Many participants reported providing small services, which brought both instrumental and emotional value to these older adults. Small services were rarely thought of as a chore, and many of the participants said they enjoyed doing such favors. For some, altruistic behaviors shaped their identity, as Magdalena told us:

I like to help people, and to me, that is my joy in life, helping others. Giving, baking, talking: that’s what we do. We have nothing to do now, so all we can do now is help others. (P73, 75, W)

Eight reported receiving small services from neighbors and kinfolk. Neighbors who lived next door knew that they could count on each other for small services, such as borrowing tools, taking care of each other’s homes when they were away on vacation, or looking out for each other’s health. However, other participants experienced the decrease of socialization in their neighborhood. As Allen said:

A few years ago, there used to be more holiday parties and half the neighbors haven’t done that lately. I think they are mostly involved with their children or other activities. (P97, 75, M)

For these older adults, large services usually meant caretaking. They saw this as a burden and only engaged in it out of a sense of family duty. Five participants reported receiving large services and five reported providing them. For Joe, it was a matter of being the only family member geographically close enough to help with an ailing parent:

My mother-in-law had a stroke, so I have been certainly [helping]. I’m the only one in the city with the exception of my one daughter who’s even related. (P7, 73, M)

Due to its onerousness, participants expected to receive large services from family rather than friends. However, in the absence of family, a few participants received care from friends. Rachel recalled:

I had my knee replaced and I needed someone to stay with me the first week that I was home. My sister was going to do it but then she fell and broke her arm. So I have a good friend in Ottawa and she came up. (P98, 72, W)

Participants also provided emotional aid to their kin and friends. They valued the emotional connection and often associated it with companionship.

By contrast to other kinds of support, financial aid was hardly mentioned, with the one exception being a father who had helped to back his son’s business. No one reported receiving/giving financial aid.

How do digital media intersect with traditional means of providing social support? (RQ2)

The East Yorkers’ integrated use of digital media with in-person and telephonic contacts facilitated the mobilization of social support, particularly companionship, with kin and friends.

To keep in touch with various social groups, participants used digital media to coordinate social events where they could enjoy companionship. For instance, 24 participants reported using email for coordinating get-togethers and catching up with family and friends, and 11 participants used Facebook to stay updated with news and pictures of kin and friends.

At times, digital media substituted for in-person and telephonic contacts. Despite living near friends in the same neighborhood or city, some participants could not see them often because they were homebound. Many also had friends or relatives that were homebound. Mobility was a concern for many older adults, especially for those who were ill. Digital media, as a complement, alternative, and substitute for face-to-face communication were especially important for these participants. However, not all participants were technologically adept. We identified one group comfortable with email and willing to try out less familiar digital media such as Skype or Facebook and a second group that stayed away from digital media altogether, relying exclusively on phone and in-person exchanges. But, as Fortunati (Citationin press) also reports, even the first group, ‘often behave[d] like novices,’ having technology crashes or misunderstanding the unique communication norms of digital media.

Although distance could be the biggest barrier to companionship, as it is for younger East Yorkers (Mok et al., Citation2010), some participants used digital media to minimize the barrier, especially for being in contact with kin connected by network structures and normative obligations (see also Yuan et al., Citation2016). Seventeen reported having long-distance kin and three had long-distance friends. Among those who have kin far away, 59% (10/17) of them used the telephone regularly to talk to family members; 41% (7/17) used email, Skype, or Facebook. While email and Skype were used mostly among family members of the same generation, Facebook was often used for communication between older adults and younger family members. Rose said,

I use Facebook … sometimes I see something on their page that I like to see. I like Facebook because I have a lot of young cousins, who I can see what they’re up to. Where they are. I just like that kind of family connection that I can get on the internet. Because they live in Alberta and I live in Ontario … Pictures, more pictures on Facebook. I like looking at pictures of them and their kids and their kids’ kids. (P40, 67, W)

Digital media were particularly useful for enabling companionship with those living away from socially close family and friends. For example, Eva used email to maintain long-distance friendships. The convenience of email allowed her to keep connected to friends whose relationships would likely have atrophied if she still had to rely on mailing handwritten letters. Digital media increased communication frequency and provided non-existent opportunities for companionship.

I have friends that I went to school with and we just send a quick note of something happening or any news or asking questions, but I would never sit down and write a letter and put a stamp on it and go. I used to at Christmas and birthdays and everything, but now we’re in touch way more often. (Maria, P90, 82, W)

Despite their digital involvement, voice conversations by telephone continue to be crucial in these older adults’ lives (Wellman, Citation1979; Wellman & Tindall, Citation1993; Wellman & Wortley, Citation1990; Yuan et al., Citation2016). They did not consider phone chats to be digital media. Although most used smart phones, a phone is a phone to these older adults ‒ one that they have long used as the most important and routine communication medium. Unlike younger adults, phones were for talking and not for other social activities such as texting.

The East Yorkers did not consider digital media to be a substitute for the phone, as the phone was considered a tool for support with its own affordances. The phone was compatible with digital media, occupying its own niche in these older adults’ communication repertoire. Having a phone nearby both eased worries about emergencies and gave network members the comfort of knowing that help was at the fingertips of their elderly friends and relatives. In addition to convenience, chats over the phone were valued, allowing them to have ‘real conversations’ with their friends. Juliana explained:

I like to talk with them. If you send someone an email, you’re not talking with them. They’ll get it and then they read it and respond. I prefer to call up on the phone and talk to them directly. (P53, 67, W)

In what ways do older adults use digital media for exchanging social support? (RQ3)

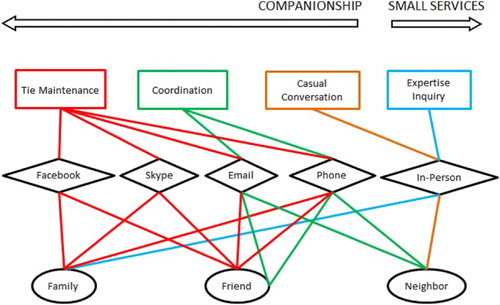

We identified four processes by which these older adults used digital media for exchanging social support: (1) coordination, (2) tie maintenance, (3) casual conversation, and (4) expertise inquiry. The first three mechanisms are associated with companionship and the last is related to small services (). We also identified patterns with regard to the use of specific channels of communication, which we discuss in detail under each process, with some East Yorkers using different media depending on the kind of relationship they had.

Figure 1. A model of social support mobilization in a population of older adults by type of tie, media, and type of support.

Coordination

For these East Yorkers, coordination usually complemented companionship, involving activities such as planning events, get-togethers, and celebrations with friends, family, and neighbors. The participants strongly preferred using the phone to organize events; only four relied on email. When the phone users turned to email, it was to keep additional network members in the loop and as a supplementary means of coordination. The four who preferred email for coordination (supplemented by the phone) saw email as more convenient because it did not interrupt others. They especially valued this for coordinating with their busy adult children. These participants appreciated the affordances of email in particular when it came to the challenges of coordinating an event. As Luisa said:

Email now becomes one of the communication modes for rounding up the monthly luncheon meeting for retired persons. In the past, one person had to make phone calls. My girlfriend complained, ‘My God, for the last 20 years, I have to make twenty phone calls and leave a message and then wait for another twenty calling me back!’ Now, she just has to do all the emails. (P69, 68, W)

In some cases, husbands and wives worked together. For example: Malik (P8, 70, M) found it convenient that his wife used Facebook to coordinate social events. He praised her skills to use digital media and organize their social life. Raol (P7, 73, M) used to rely on his wife to use digital media to organize social events, but as a result of her illness, he has taken on this role. He uses Skype to coordinate events and stay in touch with his daughter who lives abroad.

Maintaining ties

To maintain ties, these East Yorkers spent much time reaching out to long-time friends and family, many of whom had become geographically dispersed. Here, too, many preferred using the telephone (see similar findings in Yuan et al., Citation2016). Nevertheless, they used email as a supplementary aid to bridge distances and time zones and for its convenience in sending quick notes that did not require immediate replies. Ingrid explained email’s convenience:

And the email is wonderful because I would never keep as closely in touch with my friends having lived in the States. I lived there for fourteen and a half years and then people that I’ve known anywhere and everywhere and relatives, I use it for, I wouldn’t be as often [in touch]. (P90, 82, W)

Digital media helped some participants to reconnect with old friends. Thomas recounted how he reconnected with an old friend in Malaysia after he found his business card while cleaning out his desk:

And I knew he was off as a lawyer and it popped up [online] as a lawyer, so I just emailed the address that came up, and I’d say within 5 hours I had an answer, ‘How the hell did you find me?’ (P68, 67, M)

Eleven (of the 42, 26%) older adults went beyond email, using Facebook to find out what is happening in the lives of friends and family. They were passive readers on Facebook, rather than posting updates about their own lives.

Four used Skype to converse with socially close but geographically distant network members ‒ mostly family and, in one instance, a socially close friend.

You can see that person and see how they look. Otherwise then you’re talking on the phone and have no idea what’s going on. (Olga, P20, 80, W)

However, three of the four only used Skype because other network members had asked them to. Other participants did not seem to be aware of it or did not know if others had it available.

Casual conversation

Chatting with others without the intention of providing support (neighborly chats, passing along jokes, gossip) mostly took place in person, often with neighbors, with many participants noting that saying, ‘Hello,’ is just the neighborly thing to do. Digital media were not used to keep in touch with neighbors. Many of these older adults placed a high value on in-person communication and claimed there was no substitute for this form of engagement. Some had discomfort with technology, and the majority just preferred face-to-face communication as a fuller form of communication. As Blake told us:

It gives you a more concentrated effort. You can get caught up with them. (P72, 65, M)

Despite the preference for in-person chats, some participants did rely on email for staying in casual contact with geographically distant friends and relatives.

Expertise inquiry

Our coding discovered the exchange of expertise as an important form of support that previous East York studies had not identified. Many participants got advice from more expert network members in dealing with digital media, home renovations, or automotive issues. Although expertise is a type of small service, the participants did not see it that way. Such advice often came from friends and family during in-person or telephone conversations. We also identified one case where expertise was sought from a weak tie, while in another divergent case, a translator told how his English as a Second Language students were contacting him for assistance:

Usually it’s the telephone and email. And lots of times, say they have a problem, they’ll email the language problem to me … Most of them have cells; they’ll call me on the cell, but if they can’t they’re always near a computer. (Thomas, P68, 67, M)

Although both men and women received expertise advice via email, women particularly relied on it. When men and women lived together, they often cooperated in dealing with technical as well as interpersonal issues.

Discussion

Our most notable finding is the most basic: more than half of the East York older adults have joined the digital age. Although they are most comfortable with telephoning, many are like their younger counterparts in using digital media in conjunction with phones to network with their friends and relatives, as well as to obtain information and engage in online activities (see also Fortunati, Citationin press). This is the continuation of their younger adult lives for those who have already started using the internet earlier, often introduced to computers at work. Indeed, younger older adults are more apt and likely to use digital media than older ones.

Pressure and encouragement from peers and younger family and friends have also led many to digital media; some feel they have little choice (see also Quan-Haase, Martin, & Schreurs, Citation2016). Many see the practicality of using digital media: if they want to connect with their grandchildren living 1000 km away, digital media are the most fruitful forms of routine contact in-between rare in-person visits. If they want to arrange family get-togethers, one group email message is more efficient than 20 phone calls. The older adults’ use of digital media is well-integrated into the in-person contacts that are part of their everyday lives (Wellman, Quan-Haase, Witte, & Hampton, Citation2001). As seniors’ digital media use trends strongly upwards, fewer are technology-avoiding.

Nevertheless, older adults’ use of digital media is qualitatively different than the use by younger adults, as it relies on now-traditional email rather than on newer applications. Facebook was only passively used. Although some used Skype, once connected, it was just like a telephone call, albeit with engrossing visuals. The participants scarcely knew about such things as Instagram or Snapchat.

When it comes to integrating digital media, more than anything, these older adults continued their lifelong habits of using the telephone to complement their in-person get-togethers. To be sure, smartphones are now digital media. But to the participants, they were almost identical to their traditional landline phones, except portable. The senior East Yorkers were talkers rather than texters on their phones ‒ much less users of mobile apps. Thus, they can be described as technology-essentialists, using tools and features essential to their lives.

Companionship was the key to these older adults’ interpersonal lives ‒ in person, on the telephone, and on the internet. Rather than making new ties that are more prevalent in some young adults (McEwen & Wellman, Citation2013), senior East Yorkers focused on maintaining existing ties (see also Mesch, Talmud, & Quan-Haase, Citation2012). They worked hard to coordinate joint activities, such as family get-togethers, and they often used digital media to seek out the expertise of their friends and relatives. There is some indication that women, historically more active maintainers of networks than men (Antonucci & Akiyama, Citation1987; Wellman, Citation1990), are more apt to use digital media for companionship. Older men, however, sometimes needed to change roles, as their spouses become frail and no longer are able to coordinate and maintain their social lives.

Digital media played important roles in mobilizing the older adults’ social support; thus it can increase well-being and reduce isolation. The reliance on email and Skype in conjunction with the telephone meant that many exchanges were one-to-one rather than the broader network communications (many-to-many) that social media such as Facebook facilitate (Tian & Menchik, Citation2016).

As we had found in previous East York research with younger adults, the participants exchanged five types of social support: emotional aid, small services, large services, financial aid, and companionship. We confirmed that companionship is an especially central type of support for older adults (Hagan, Manktelow, Taylor, & Mallett, Citation2014). As in earlier East York studies, we found that the participants exchanged different kinds of social support through different types of ties. For all adult age-groups, each kind of support has its own dynamics.

We identified four mechanisms of support mobilization: coordination, maintaining ties, casual conversation, and expertise inquiry. Previous East York research had shown ties with socially close kin to be especially important (Wellman, Citation1979; Wellman & Wortley, Citation1990). To our surprise, we found that ties with friends were more actively maintained online than ties with kin, except for the almost exclusive use of Skype for maintaining kinship ties. While family is an important source of support for older adults, support exchanges with family were considered normative obligations and sometimes resented. Adult children were often at work and grandchildren at school, with many demands on their time. By contrast, supportive exchanges with same-generation friends were felt to be voluntary, reciprocal, and most importantly more available (see also Yuan et al., Citation2016).

Conclusions

Our findings show that digital media are enhancing the ability of many older adults to mobilize social support (see also Cotten et al., Citation2013). There is no doubt that a majority of older adults use digital media, particularly email, to exchange social support with friends and family near and far. They see email as handy for exchanging support with far-away ties as much as for near-by ties, especially as they and many friends and family deal with lessened mobility. In these cases, any distance is a barrier to support mobilization. Yet, the telephone remains the preferred choice (after in-person contact) for providing support, because of its prevalence, immediacy, interactivity, usability, and familiarity.

Our research suggests a model of how older adults use a variety of media to mobilize support with different types of ties (see ):

Older adults maintain their social ties with family and friends by using an array of digital media in addition to the telephone; they especially use email to keep in contact with friends.

To coordinate social activities, older adults principally use email and phone to contact friends.

Neighbors only use in-person encounters for casual conversations.

To obtain expertise, including getting help in using digital media, family members are asked in person and, to a lesser extent, by phone.

Our model comprises four mechanisms of social support exchange that our participants used online: (1) coordination, (2) tie maintenance, (3) casual conversation, and (4) expertise inquiry. While the first three are associated with companionship, the last one relates to the exchange of small services. Our model not only expands previous typologies of social support (Plickert, Côté, & Wellman, Citation2007; Wellman & Wortley, Citation1990), but it also stresses the process of mobilizing support, making it clear that mobilization is not a static phenomenon. Rather, coordination is required for both giving and receiving social support, and digital media are critical for much of this coordination, as they facilitate contact and also aid in the back and forth of scheduling interactions, meetings, and other types of contact (Chayko, Citation2016; Rainie & Wellman, Citation2012). The relevance of micro-communications ‒ communication that is short and meant for purposes of coordination ‒ are best understood in the context of older adults’ everyday lives, who often have less-structured time and may welcome more opportunities for social interaction.

Although none of the participants we interviewed were institutionalized, our study highlights the role of digital media in keeping older adults connected. For some of these seniors, mobility ‒ linked to health-related challenges ‒ was a barrier to being in contact and exchanging support. Even if they themselves were mobile, some of their friends and family might not have been. Digital media helped older adults seek social support.

Future studies could test the model and provide further evidence regarding interaction effects between type of tie by type of media by type of support. The study’s limitations include the cross-sectional design and the fact that data were collected from a single English-Canadian urban locality, with only self-reports from a small sample with a narrow socioeconomic profile. The findings highlight the need to examine in more breadth and depth how various support providers function in specific populations, according to factors such as gender, ethnicity, migration, and socioeconomic status (Hammen, Citation2005; Raffaelli et al., Citation2013).

Hence, these findings need to be placed in the context of some of the large-scale social changes affecting older adults in North America and elsewhere. Old age does not mean retreating into a walled bunker. Many older adults today continue to be networked individuals, staying active and engaging in social activities (Rainie & Wellman, Citation2012). Nevertheless, many older adults also have diminished mobility. They turn to whatever means is useful, available, and convenient to stay in contact, including the internet and mobile phones. They keep up with their friends and family online, and hear about them from others. When they have health concerns, they seek support from their friends and relatives, integrating the copious ‒ often confusing ‒ advice they receive with what their doctors tell them (Kelner, Wellman, Pescosolido, & Saks, Citation2000). In fact, social support exchanged via digital media is considered by older adults in East York to be ‘real,’ not token, support. Our study shows that learning how to master technology is in itself a form of social support mobilization that provides opportunities to strengthen the networks of older adults.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Christian Beermann, Brent Berry, Lilia Smale, Rhonda McEwen, Darryl Pieber, Helen Hua Wang, Carly Williams, Isioma Elueze, and Alice Renwen Zhang for their research collaboration.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Anabel Quan-Haase is Professor of Information and Media Studies and Sociology at Western University and Director of the SocioDigital Lab. She is also the author of Technology and Society (OUP, 2016) and co-editor of the Handbook of Social Media Research Methods (Sage, 2017) [email: [email protected]].

Guang Ying Mo is a Post-Doctoral Fellow at the Institute of Information, Communication, Culture and Technology at the University of Toronto Mississauga. Dr. Mo uses social network approach to examine the mechanisms of collaboration across knowledge-based boundaries and its impact on innovation [email: [email protected]].

Barry Wellman, the co-director of the NetLab Network, has led all four East York studies. A professor in the University of Toronto's Sociology Department for 47 years, he is a member of the Royal Society of Canada, has co-authored more than 200 papers with more than 80 colleagues, and is the co-author of Networked: The New Social Operating System [email: [email protected]].

ORCID

Anabel Quan-Haase http://orcid.org/0000-0002-2560-6709

Barry Wellman http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6340-8837

Additional information

Funding

References

- Anderson, M., & Perrin, A. (2016, September 7). 13% of Americans don’t use the internet. Who are they? Retrieved from http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/09/07/some-americans-dont-use-the-internet-who-are-they/

- Antonucci, T. C., & Akiyama, H. (1987). An examination of sex differences in social support among older men and women. Sex Roles, 17(11–12), 737–749. doi: 10.1007/BF00287685

- Bradley, N., & Poppen, W. (2003). Assistive technology, computers and Internet may decrease sense of isolation for homebound elderly and disabled persons. Technology and Disability, 15, 19–25.

- Bromell, L., & Cagney, K. A. (2014). Companionship in the neighborhood context: Older adults’ living arrangements and perceptions of social cohesion. Research on Aging, 36(2), 228–243. doi: 10.1177/0164027512475096

- Bruggeman, J. (2016). The strength of varying tie strength: Comment on Aral and Van Alstyne. American Journal of Sociology, 121(6), 1919–1930. doi: 10.1086/686267

- Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory. London: Sage.

- Chayko, M. (2016). Superconnected. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2014). Basics of qualitative research. London: Sage.

- Cornwell, E. Y., & Waite, L. J. (2009). Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and health among older adults. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 50(1), 31–48. doi: 10.1177/002214650905000103

- Cotten, S. R., Anderson, W. A., & McCullough, B. M. (2013). Impact of internet use on loneliness and contact with others among older adults. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 15(2), e39. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2306

- Dickens, A. P., Richards, S. H., Greaves, C. J., & Campbell, J. L. (2011). Interventions targeting social isolation in older people. BMC Public Health, 11(1), 133–647. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-133

- Ellison, N. B., Steinfield, C., & Lampe, C. (2007). The benefits of Facebook ‘Friends:’ Social capital and college students’ use of online social network sites. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 12(4), 1143–1168. doi: 10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00367.x

- Fortunati, L. (in press). How young people experience elderly people’s use of digital technologies in everyday life. In S. Taipale, T.-A. Wilska, & C. Gilleard (Eds.), Digital technologies and generational identity: ICT usage across the life course. London.

- Fratiglioni, L., Wang, H. X., Ericsson, K., Maytan, M., & Winblad, B. (2000). Influence of social network on occurrence of dementia: A community-based longitudinal study. The Lancet, 355(9212), 1315–1319. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02113-9

- Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5, 1–10.

- Gray, A. (2009). The social capital of older people. Ageing and Society, 29(01), 5–31. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X08007617

- Hagan, R., Manktelow, R., Taylor, B. J., & Mallett, J. (2014). Reducing loneliness amongst older people: A systematic search and narrative review. Aging & Mental Health, 18(6), 683–693. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2013.875122

- Hammen, C. (2005). Stress and depression. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 1(1), 293–319. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143938

- Hampton, K. N., Rainie, L., Lu, W., Shin, I., & Purcell, K. (2015, January 15). Social media and the cost of caring. Retrieved from http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/01/15/social-media-and-stress/

- Hlebec, V., & Kogovšek, T. (2013). Different approaches to measure ego-centered social support networks: A meta-analysis. Quality & Quantity, 47(6), 3435–3455. doi: 10.1007/s11135-012-9731-2

- Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., Layton, J. B., & Brayne, C. (2010). Social relationships and mortality risk: A meta-analytic review. PLoS Medicine, 7(7), e1000316. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316

- Iliffe, S., Kharicha, K., Harari, D., Swift, C., Gillmann, G., & Stuck, A. E. (2007). Health risk appraisal in older people 2. British Journal of General Practice, 57(537), 277–282.

- Kelner, M., Wellman, B., Pescosolido, B., & Saks, M. (2000). Complementary and alternative medicine: Challenge and change. Oxford: Routledge.

- Kennedy, J., Nansen, B., Arnold, M., Wilken, R., & Gibbs, M. (2015). Digital housekeepers and domestic expertise in the networked home. Convergence, 21(4), 408–422.

- McEwen, R., & Wellman, B. (2013). Relationships, community, and networked individuals. In R. Teigland & D. Power (Eds.), The immersive internet (pp. 168–179). London: Palgrave-Macmillan.

- Mesch, G. S., Talmud, I., & Quan-Haase, A. (2012). Instant messaging social networks. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 29(6), 736–759. doi: 10.1177/0265407512448263

- Mok, D., Wellman, B., & Carrasco, J. A. (2010). Does distance matter in the age of the internet? Urban Studies, 47(13), 2747–2783. doi: 10.1177/0042098010377363

- National Institute of Mental Health. (2009). Older adults: Depression and suicide facts. Retrieved from http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/older-adults-and-depression/index.shtml

- Plickert, G., Côté, R. R., & Wellman, B. (2007). It’s not who you know, it’s how you know them: Who exchanges what with whom? Social Networks, 29(3), 405–429. doi: 10.1016/j.socnet.2007.01.007

- Quan-Haase, A., Beermann, C., Martin, K., Miller, M., & Wellman, B. (2016, April). Older adults networking on and off digital media. Paper presented at International Sunbelt Social Network Conference, Newport Beach, CA.

- Quan-Haase, A., Martin, K., & Schreurs, K. (2016). Interviews with digital seniors: ICT use in the context of everyday life. Information, Communication & Society, 19(5), 691–707. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2016.1140217

- Raffaelli, M., Andrade, F. C. D., Wiley, A. R., Sanchez-Armass, O., Edwards, L. L., & Aradillas-Garcia, C. (2013). Stress, social support, and depression: A test of the stress-buffering hypothesis in a Mexican sample. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 23(2), 283–289. doi: 10.1111/jora.12006

- Rainie, L., & Wellman, B. (2012). Networked: The New Social Operating System. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Rains, S. A., Brunner, S. R., & Oman, K. (2014). Self-disclosure and new communication technologies. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 33(1), 42–61. doi: 10.1177/0265407514562561

- Requena, F. (2013). Family and friendship support networks among retirees. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 33(3/4), 167–185. doi: 10.1108/01443331311308221

- Schreurs, K., Quan-Haase, A., & Martin, K. (in press). Problematizing the digital literacy paradox in the context of older adults’ ICT use. Canadian Journal of Communication, 42(2).

- Siibak, A., & Tamme, V. (2013). ‘Who introduced Granny to Facebook?’: An exploration of everyday family interactions in web-based communication environments. Northern Lights: Film & Media Studies Yearbook, 11(1), 71–89. doi: 10.1386/nl.11.1.71_1

- Smith, A. (2014, April 3). Older adults and technology use. Retrieved from http://www.pewinternet.org/2014/04/03/older-adults-and-technology-use/

- Smyth, N., Siriwardhana, C., Hotopf, M., & Hatch, S. L. (2015). Social networks, social support and psychiatric symptoms: Social determinants and associations within a multicultural community population. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 50(7), 1111–1120. doi: 10.1007/s00127-014-0943-8

- Statistics Canada. (2016, September 28). Demographic change. Retrieved from http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/82-229-x/2009001/demo/int1-eng.htm

- Tian, X., & Menchik, D. A. (2016). On violating one’s own privacy. In L. Robinson, J. Schulz, & S. R. Cotten (Eds.), Communication and information technologies annual: [New] media cultures (pp. 3–30). Bingley: Emerald Group.

- Turkle, S. (2011). Alone together. New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Wellman, B. (1979). The community question: The intimate networks of East Yorkers. American Journal of Sociology, 84, 1201–1231. doi: 10.1086/226906

- Wellman, B. (1990). The place of kinfolk in personal community networks. Marriage and Family Review, 15, 195–228. doi: 10.1300/J002v15n01_10

- Wellman, B., Hogan, B., Berg, K., Boase, J., Carrasco, J. A., Côté, R., & Tran, P. (2006). Connected lives. In P. Purcell (Ed.), Networked neighbourhoods (pp. 157–211). Guildford: Springer.

- Wellman, B., Quan-Haase, A., Witte, J., & Hampton, K. (2001). Does the Internet increase, decrease, or supplement social capital? American Behavioral Scientist, 45(3), 436–455. doi: 10.1177/00027640121957286

- Wellman, B., & Tindall, D. (1993). How telephone networks connect social networks. In W. D. Richards & G. A. Barnett (Eds.), Progress in communication sciences (Vol. 12, pp. 63–93). Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

- Wellman, B., & Wortley, S. (1990). Different strokes from different folks: Community ties and social support. American Journal of Sociology, 96(3), 558–588. doi: 10.1086/229572

- Williams, P., Barclay, L., & Schmied, V. (2004). Defining social support in context: A necessary step in improving research, intervention, and practice. Qualitative Health Research, 14(7), 942–960. doi: 10.1177/1049732304266997

- Wright, K. (2000). Computer-mediated social support, older adults, and coping. Journal of Communication, 50(3), 100–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2000.tb02855.x

- Xia, L.-X., Liu, J., Ding, C., Hollon, S. D., Shao, B.-T., & Zhang, Q. (2012). The relation of self-supporting personality, enacted social support, and perceived social support. Personality and Individual Differences, 52(2), 156–160. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2011.10.002

- Yuan, S., Hussain, S. A., Hales, K.D., & Cotten, S. R. (2016). What do they like? Communication preferences and patterns of older adults in the United States. Educational Gerontology, 42(3), 163–174. doi: 10.1080/03601277.2015.1083392

- Zickuhr, K., & Madden, M. (2012, June 6). Older adults and internet use: For the first time, half of adults ages 65 and older are online. Retrieved from http://www.pewinternet.org/~/media/Files/Reports/2012/PIP_Older_adults_and_internet_use.pdf