ABSTRACT

Populism continues to gain traction in politics but there has been relatively little research on how it plays out on the Internet. The special issue at hand aims at narrowing this gap of research by focusing on the close relation between populism and online communication. This introduction presents an integrative definition of populism, as well as a theoretical analysis of the interplay between populist communication logic and online opportunity structures. The individual contributions discuss how populist actors may benefit from the Internet. They analyze how political leaders and extreme parties use populist online communication. The authors also shed light on how populist movements may relate to various political parties. They finally demonstrate which groups of social media users are more susceptible to populism than others and what effects populist online communication may have on citizens. We hope that this special issue will contribute to the discussion on what is arguably one of the largest political challenges currently faced by a series of nations around the globe.

Populism is gaining traction in politics. In the year before the publication of this special issue, the USA and Europe were both confronted with a series of major elections that featured more or less successful populist candidates. We can think here of US President Donald Trump, presidential candidates Norbert Hofer in Austria and Marine Le Pen in France, as well as party leader Geert Wilders in the Netherlands.

Against this backdrop, it is no surprise that the body of scientific literature on populism has been growing (Aalberg, Esser, Reinemann, Strömbäck, & de Vreese, Citation2017; de la Torre, Citation2015; Inglehart & Norris, Citation2016; Kriesi & Pappas, Citation2015; Mudde & Rovira Kaltwasser, Citation2012b). The concept has been discussed theoretically (Alvares & Dahlgren, Citation2016; Esser, Stepinska, & Hopmann, Citation2017; Krämer, Citation2014; Mazzoleni, Citation2003; Wirth et al., Citation2016) and has been empirically analyzed in various communication channels, such as manifestos (Caiani & Graziano, Citation2016; Rooduijn, De Lange, & Van der Brug, Citation2014), party broadcasts (Jagers & Walgrave, Citation2007), speeches (Hawkins, Citation2009; Oliver & Rahn, Citation2016), the press (Akkerman, Citation2011; Herkman, Citation2017; Rooduijn, Citation2014), news broadcasts (Bos, van der Brug, & de Vreese, Citation2011), and talk shows (Bos & Brants, Citation2014; Cranmer, Citation2011).

However, there has been relatively little research on populism on the Internet (Bartlett, Birdwell, & Littler, Citation2011; Engesser, Ernst, Esser, & Büchel, Citation2017; Gerbaudo, Citation2014; Groshek & Engelbert, Citation2013; van Kessel & Castelein, Citation2016). This dearth of scientific studies is remarkable given the fact that the close relation between populism and online communication was already established relatively early in the history of the Internet (Bimber, Citation1998). We hope that, by revisiting this intriguing relation, the special issue at hand provides new insights into populist communication and populism in general.

This introduction presents an integrative definition of populism, a theoretical analysis of the interplay between populist communication logic and online opportunity structures, as well as a brief overview of the individual contributions to the special issue.

Defining populist communication logic and online opportunity structures

Populism can be understood as ideology (Mudde, Citation2004), style (Jagers & Walgrave, Citation2007), or strategy (Weyland, Citation2001). Although there has been a vivid debate about the ‘correct’ definition (e.g., Aslanidis, Citation2016), we argue that the three terms merely represent different aspects of populism and that they are not mutually exclusive. However, the terms are semantically interrelated, in particular ideology and style (Irvine, Citation2001), which has led to misunderstandings. Therefore, we suggest the following clarification: The approach of populism as ideology defines populism as a set of ideas and focuses, within the context of the special issue at hand, on the content of populist communication (What?). The approach of populism as style conceives of populism as mode of presentation and is interested in the form of populist communication (How?). The approach of populism as strategy refers to populism as a means to an end and focuses on the motives and aims of populist communication (Why?).

Beside these three aspects of populism in the media, scholarship has also been interested in the populist actor or messenger of populist communication (Who?) (Aalberg & de Vreese, Citation2017, p. 9; Canovan, Citation1999, p. 6).

In this introduction, we combine all four above components into what we refer to as populist communication logic. It draws on the concept of media logic (Altheide, Citation2014; Altheide & Snow, Citation1979) and can be conceived of as the sum of norms, routines, and procedures shaping populist communication.

Populist communication does not occur in a vacuum but is embedded in specific social contexts which can be grasped by the concept of opportunity structures. Political opportunity structures refer to characteristics of a political system that positively affect a given phenomenon, e.g., social movements (Kriesi, Citation1995; McAdam, Citation1982). Related to this concept are discursive opportunities (Esser et al., Citation2017; Gamson, Citation2004; Koopmans & Statham, Citation2003) which ‘determine a message’s chances of diffusion in the public sphere’ (Koopmans & Olzak, Citation2004, p. 202). Drawing on these previous ideas, we introduce the concept of online opportunity structure, which refers to factors inherent to the online media system. We are interested in those online opportunity structures which foster populist communication.

Some of these factors have been attributed to online media in general, while others have been assigned to social media in particular. However, in light of recent theoretical and empirical research regarding the interplay of online mass media and social media (Chadwick, Citation2013; Newman, Fletcher, Levy, & Nielsen, Citation2016), it seems increasingly difficult to maintain such an analytical distinction. Therefore, we have decided to merge all forms of online opportunities into a single concept.

Interplay of populism and online opportunities

This section is dedicated to the interplay of populist communication logic and online opportunities. We begin with aspects related to populism as ideology, move on to the populist actor, and conclude with populism as style and strategy.

Populism as ideology

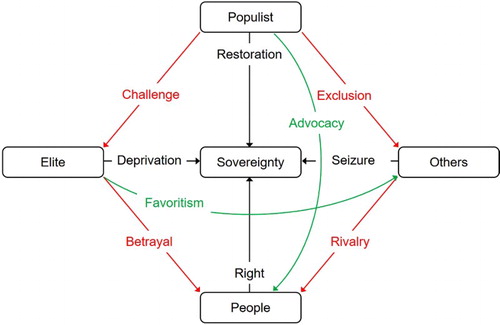

The populist ideology is widely regarded as ‘thin’ or less elaborate (Canovan, Citation2002, p. 32; Kriesi, Citation2014, p. 362; Mudde, Citation2004, p. 543; Reinemann, Aalberg, Esser, Strömbäck, & de Vreese, Citation2017, p. 13; Wirth et al., Citation2016, p. 8). This means that it draws on a relatively small set of elements and relations. Beyond that, it can be enriched with more substantive add-on ideologies, such as nationalism, liberalism, and socialism, which may result in left-wing populism or right-wing populism. In the following, we present a heuristic model that includes the most important elements of populist ideology and their interrelations (see ).

The model is based on the idea of a struggle over political sovereignty. The people is regarded as the ultimate sovereign but the elite is assumed to betray the people and to deprive it of its legitimate right to exercise power. The populist actor pitches himself as a challenger of the elites and as an advocate of the people. S/he aims at wrenching the sovereignty from the elites and at restoring it to the people. The elite is also assumed to engage in a complicity with ‘the others’ and to favor them over the people. ‘The others’ supposedly rival the people and illegitimately attempt to seize sovereignty but the populist actor aims at excluding ‘the others’ from society.

There has been disagreement on where to draw the line between the thin populist ideology and the add-on ideologies. In particular, the nature of ‘the others’ and its capacity to replace the elites are disputed. Some authors argue that ‘the others’ are a constitutive element of populism and that there is a type of ‘excluding populism’ (Jagers & Walgrave, Citation2007, p. 334) without any reference to the elites, while others consider ‘the others’ merely as a part of added right-wing ideology (Rooduijn, Citation2014; Schulz et al., Citation2017; Wirth et al., Citation2016). A third group assumes an intermediate position and remains largely undecided (Albertazzi & McDonnell, Citation2008; Engesser et al., Citation2017; Reinemann et al., Citation2017). Against this backdrop, we include ‘the others’ in our heuristic model in order to integrate the different approaches. Based on this model, we will discuss in the following how populist communication logic interacts with online opportunity structures (see ).

Table 1. Interplay of populist communication logic and online opportunity structures.

People-centrism and direct online connections

There is a broad consensus that the people is the most important element of the populist ideology (Albertazzi & McDonnell, Citation2008, p. 6; Reinemann et al., Citation2017, p. 14; Taggart, Citation2000, p. 91). The people is conceived of as homogenous group or monolithic bloc (Reinemann et al., Citation2017, p. 19). It is also regarded as inherently good and bestowed with a catalogue of positive attributes, such as virtuous, pure, or wise. Depending on the context of populist communication and the add-on ideologies, the notion of the people may vary. While right-wing populism tends to define the people as nation, left-wing populism rather conceives of it as class (Abts & Rummens, Citation2007; Mény & Surel, Citation2000). In any case, the populist actors pitch themselves as representatives, advocates, and mouthpieces of the people (Canovan, Citation1999, p. 4). To fulfill these functions, they seek a fast, direct, and unmediated connection to the people. On the one hand, the populists want to be informed about the people’s opinions and problems, and, on the other hand, they aim at spreading their messages without interference or delay from the elites (Canovan, Citation2002, p. 34; Kriesi, Citation2014, p. 363).

In contrast to institutionalized means of political communication, such as manifestos and speeches, the mass media offer the populists already a more direct channel to the people (Krämer, Citation2014, p. 46). However, the populists still have to pass the journalistic gatekeepers and adhere to news production cycles (Shoemaker & Vos, Citation2009). On the Internet, these factors play a less important role – at least potentially (Williams & Delli Carpini, Citation2011, p. 61). Moreover, the online environment frequently allows for the circumvention of traditional opinion leaders and facilitates what has been referred to as the ‘one-step flow of communication’ (Bennett & Manheim, Citation2006; Vaccari & Valeriani, Citation2015). In summary, online media provide the populists with even more direct connections to the people than traditional offline media do (Engesser et al., Citation2017, p. 1113; Esser et al., Citation2017, p. 377).

Popular sovereignty and democratizing potential of the internet

Closely related to the people is the concept of popular sovereignty (Abts & Rummens, Citation2007, p. 406; Albertazzi & McDonnell, Citation2008, p. 6; Mudde, Citation2004, p. 543). It implies that the people is the legitimate und ultimate political sovereign. Popular sovereignty can be regarded as a ‘crude version of Rousseau’s General Will’ (Hawkins, Citation2009, p. 1043). In this sense, popular sovereignty is a central pillar of democracy (Canovan, Citation1999, p. 7; Laclau, Citation2005, p. 169). However, the populists denounce the elites who deprive the people of their sovereignty and they also refuse the checks and balances which restrict them (Abts & Rummens, Citation2007, p. 408; Mény & Surel, Citation2002, p. 13). Therefore, populism in its purest sense is regarded as a serious threat to liberal democracy (Mudde & Rovira Kaltwasser, Citation2012a, p. 16; Reinemann et al., Citation2017, p. 18). Nevertheless, populist ideas or movements can remind the political representatives of their responsibility towards the electorate and indicate the failings of the political system (Taggart, Citation2002, p. 75).

Moreover, the Internet has been bestowed with the potential to democratize the political system. Some scholars predicted an equalization of power and undermining of representative political institutions through new possibilities of communication and participation (Rheingold, Citation1993). This school of thought can be subsumed under the label of direct democracy optimism (Anstead & Chadwick, Citation2009, p. 59). Other authors assumed a more moderate position and discerned an increasing potential for direct representation which they conceived as an on-going, two-way process with high levels of accountability (Coleman, Citation2005; Coleman & Blumler, Citation2009). This approach may be labeled representative democracy optimism (Anstead & Chadwick, Citation2009, p. 59). In summary, populism and the Internet have in common that they both have been regarded as correctives of democracy.

Anti-Elitism and non-elite online actors

The populist ideology is built upon the fundamental antagonism between the people and the elites (Mény & Surel, Citation2002, p. 12; Mudde, Citation2004, p. 543; Rooduijn, Citation2014, p. 727). The elites form an essential part because they are the ones who betray the people and deprive it of its sovereignty. The concept of the elite may change depending on the add-on ideologies: Right-wing populism may be more likely to attack supranational institutions, the mass media and the courts, while left-wing populism may rather denounce the economic and religious elites (Engesser et al., Citation2017).

Although the elites may be accused of being arrogant, selfish, and incompetent, their most relevant flaw is that they arguably have been coddled and corrupted by the political or economic system. The populist, however, maintains the impression that he or she is untainted by power. This apparent immaculacy allows the populist to legitimately attack and challenge the elites. Therefore, the populists aim at presenting themselves as non-elite actors.

It suits the populist communication logic well that the Internet provides non-elite actors with new opportunities to influence political communication (Chadwick, Citation2013, p. 88). This phenomenon can be approached from different perspectives. One strand of research focused on the role of online challengers (Kriesi, Citation2004; Pfetsch, Adam, & Bennett, Citation2013). A second group of scholars investigated how the Internet facilitates the rise of alternative media (Atton, Citation2004; Hintz, Citation2015). A third group analyzed how the Internet establishes counter publics (Dahlgren, Citation2005; Downey & Fenton, Citation2003). In sum, the Internet is presumed to lower the threshold for populist non-elite actors to enter the arenas of communication.

Exclusion of others and homophily of the internet

Although populist ideology regards the elites as primary antagonist of the people, they have to face a second opponent, the so-called others (Albertazzi & McDonnell, Citation2008, p. 3; Jagers & Walgrave, Citation2007, p. 322). While the elites, in terms of the social hierarchy, are perceived as residing ‘above’ the people, ‘the others’ are either located ‘beside’ (Jagers & Walgrave, Citation2007, p. 324) or even ‘below’ the people (Abts & Rummens, Citation2007, p. 418).

‘The others’ typically consist of ‘ethnic, religious, sexual, minorities’ (Reinemann et al., Citation2017, p. 21), as well as of ‘criminals, profiteers, and perverts’ (Abts & Rummens, Citation2007, p. 418). By excluding them from the people, the populist ideology addresses the human inclination towards in-group favoritism and out-group discrimination (Reinemann et al., Citation2017, p. 20).

In this regard, populist communication logic and online opportunities go hand in hand, because the Internet is presumed to frequently cultivate homophily, which is the ‘tendency of similar individuals to form ties with each other’ (Colleoni, Rozza, & Arvidsson, Citation2014, p. 318). One manifestation of homophily is the filter bubble which pre-selects consonant media content (Flaxman, Goel, & Rao, Citation2016; Pariser, Citation2011), another one is the echo chamber where political attitudes are confirmed and amplified (Jamieson & Cappella, Citation2008; Sunstein, Citation2001).

Populist actors: (charismatic) leaders and personalized online connections

Some scholars regard a charismatic leader as constitutive element of populism (Canovan, Citation1999, p. 6; Kriesi, Citation2014, p. 363; Weyland, Citation2001), while others suggest it to instead be a facilitating factor (Mudde, Citation2004, p. 545; Reinemann et al., Citation2017, p. 14). We argue that the populist actor plays an important role in the populist ideology because s/he is supposed to restore the sovereignty to the people. In addition, the populist actor deserves special attention because s/he is the messenger of political communication (Aalberg & de Vreese, Citation2017, p. 9). Finally, regardless of their theoretical relations, populism and charismatic leaders frequently co-occur in empirical reality throughout history and around the world, as can be illustrated by the prominent examples of Pericles, Napoleon Bonaparte, Beppe Grillo, Nigel Farage, Hugo Chavez, Rodrigo Duterte, Julius Malema, Donald Trump, etc. Against this backdrop, we think that populist leaders (charismatic or not) may be important parts of the populist communication logic. They shape populist communication in the sense that it is frequently focused on the populist leader.

This fits very well to the Internet’s capacity to provide the populist actor with opportunities for personalized communication (Stanyer, Citation2008). Kruikemeier, van Noort, Vliegenthart, and de Vreese (Citation2013) found that Internet users visiting a website tailored to an individual politician feel more involved and interested in politics than people visiting a website focused on a political party (p. 59). Lee and Jang (Citation2013) demonstrated that individuals experienced stronger feelings of interpersonal contact (i.e., social presence) on social media than on news websites.

Populist style and the attention economy of the internet

Several scholars have emphasized that populism can be characterized by a certain style of communication (Bos et al., Citation2011, p. 187; Canovan, Citation1999, p. 5; Krämer, Citation2014, p. 49). In contrast to the populist ideology which addresses the elements and interrelations of populist ideas, the populist style refers to the way in which these ideas are communicated. We argue that, for instance, the antagonism between the people and the elites is a part of the populist ideology. However, it is a stylistic decision to present this antagonism in a simple or an elaborate manner, in a rational or an emotional tone, or in a positive or a negative light.

The list of stylistic features that have been attributed to populism is extensive: dramatization, polarization, moralization, directness, ordinariness, colloquial and vulgar language, etc. (e.g., Bos et al., Citation2011, p. 187). We have decided to focus on three major dimensions of populist style: simplification, emotionalization, and negativity.

First of all, populist actors frequently tend to reduce complexity (Canovan, Citation1999, p. 5). They are used to narrow down all social relations to the antagonism between people, elite, and ‘others’. In their view, problems have single causes and can be solved with simple treatments (Caiani & Graziano, Citation2016, p. 258). The whole world is depicted in black and white without any shades of gray (Hawkins, Citation2009, p. 1043). Empirical studies have also demonstrated that populists prefer a simple language (Oliver & Rahn, Citation2016, p. 194).

Second, populists often rely on emotions. Canovan (Citation1999) refers to this as the ‘populist mood’ (p. 6). Most authors stressed the importance of anger, fear, and resentment (Caiani & Graziano, Citation2016, p. 260; Hameleers, Bos, & de Vreese, Citation2016, p. 7) but we argue that the role of hope should not be underestimated either. While the negative emotions are raised by the elites and ‘the others’, the positive emotions are directed towards the populist leader.

Third, the populists prefer to paint in black. Elites and ‘others’ are presented as threats, and the situation within which they operate is depicted as crisis (Moffitt & Tormey, Citation2014, p. 391; Taggart, Citation2002, p. 69). This style of communication addresses two attitudes that have been identified among the supporters of populist parties: declination and relative deprivation (Elchardus & Spruyt, Citation2016, pp. 116–117). The former concept refers to the view that the entire society develops in a negative way, while the latter implies that other members of society enjoy better positions than oneself. It is important that these notions do not require an objectively negative situation (e.g., economic crisis or absolute deprivation) but merely a sense of negativity.

In terms of online opportunity structures, the concept of attention economy implies that attention is a scarce resource over which information providers have to compete (Davenport & Beck, Citation2001). On the Internet, this competition is particularly fierce due to the abundance of content (Lanham, Citation2006). Therefore, the Internet favors content that ‘maximizes attention’ (Klinger & Svensson, Citation2015, Citation2016). The populist style of simplification, emotionalization, and negativity increases our attention by addressing fundamental perceptual patterns and news values (Shoemaker & Cohen, Citation2006). Therefore, populism is particularly well-suited to be communicated online.

Populism as strategy: power, legitimacy, mobilization, and non-institutionalized masses on the internet

Populism can also be regarded as a strategy or plan of action (Jansen, Citation2011; Weyland, Citation2001). This implies that the populist actor uses populism as a means to an end. The populists are presumed to have motives for and to pursue aims through populist communication. Three political aims are of particular interest: power, legitimacy, and mobilization. On the one hand, political actors may employ populism to acquire and exercise power (Weyland, Citation2001, p. 12). On the other hand, political actors may instrumentalize populism to secure legitimacy (Abts & Rummens, Citation2007, p. 410). This is especially true in presidential systems, where candidates and incumbents depend more heavily on the direct support of the citizens. This is also a reason for populist actors to maintain their populist practices even after they have come into office.

In a more general sense, populism can also be employed to mobilize supporters for elections, demonstrations, referenda, or any other form of political action (Jansen, Citation2011, p. 83). This particularly applies to the case of Switzerland where the ruling Swiss People’s Party regularly relies on populist mass communication to win popular initiatives.

All three strategies frequently rely on ‘uninstitutionalized’ (Weyland, Citation2001, p. 14) or ‘marginalized’ (Jansen, Citation2011, p. 82) supporters. Related to this, the Internet is often seen as a place where non-institutionalized masses gather and can be easily recruited (Shirky, Citation2008). Empirical research has demonstrated that online media can increase political action among those who are usually more reluctant to participate (Carlisle & Patton, Citation2013; Xenos, Vromen, & Loader, Citation2014). Accordingly, the Internet may provide the populist actors with exactly those non-institutionalized masses that they seek.

In summary, we could demonstrate that populist communication logic and online opportunity structures go hand in hand in various regards. To begin with, populism, as a political ideology that evolves around the concept of popular sovereignty, is particularly well-suited to be communicated through the Internet, which has been widely bestowed with the largest democratizing potential of all mass media. People-centrism appears more convincing when directly addressed to the people, and anti-elitism can be more easily expressed in a media environment that favors non-elite actors. Additionally, the homophile filter bubbles and echo chambers of the Internet are fertile grounds for the idea of excluding ‘others’.

Furthermore, features of populist style, such as simplification, emotionalization, and negativity, are perfectly in line with the Internet’s attention economy. At the same time, the populist strategies of acquiring power, securing legitimacy, and mobilizing supporters frequently target non-institutionalizes masses that can be easily found on the Internet.

Finally, the Internet provides populist leaders with personalized communication channels that allow them to exert their charisma and suggestive power.

We do not argue that the Internet has to be characterized exclusively by the online opportunity structures detailed above. In contrast, we think that online media may also, for instance, reinforce anti-democratic tendencies, support the elites, or increase plurality. Nevertheless, we are convinced that major elements of the populist communication logic and certain online opportunity structures fit together well enough to deserve a special issue of Information, Communication, & Society dedicated to this interplay.

Contributions to the special issue

The contributions to the special issue at hand cover a broad range of disciplines, definitions of populism, methods, countries, and stages of the communication process. Bracciale and Martella assumed a political science perspective, Matthes and Heiss drew on psychological theories, Stier et al. followed a computational science approach, and the remaining papers are mainly rooted within the field of communication. We included a theoretical study, as well as empirical studies that employed content analyses, surveys, an experiment, and a user behavior analysis. Online populism was investigated in the US, Latin America, within single European countries (Austria, Germany, Italy, and the Netherlands) and across six Western countries. The authors conceived of populism as political ideology, as communication style (Bracciale & Martella, Groshek & Koc-Michalska, Waisbord & Amado) or as blame attribution (Hameleers & Schmuck). We covered the communicators (Bracciale & Martella, Krämer, Waisbord & Amado), content (Ernst et al., Stier et al.), usage (Groshek & Koc-Michalska, Matthes & Heiss, Stier et al.), and effects (Hameleers & Schmuck) of populist communication on the Internet.

Krämer complements the introduction of the special issue by an in-depth discussion of the various functions that the Internet may fulfill for right-wing populists. Bracciale and Martella present an empirical typology of populist communication styles on Twitter based on the two dimensions of tonality and personalization. Waisbord and Amado could not detect any significant differences between populists and non-populists. They found that Latin American Presidents did not use Twitter to give the people a voice but rather as mouthpiece for themselves. Ernst et al. demonstrated that extreme and oppositional parties employed populist communication strategies more frequently than mainstream parties on social media.

Stier et al. found that the German party AFD and the PEGIDA movement overlapped both in terms of Facebook audiences and content. The populist actors addressed issues that had been deemphasized by mainstream parties, such as crime, migration, and Islam.

Groshek and Koc-Michalska showed that, in the US presidential elections, more active social media users were inclined to support Bernie Sanders while more passive social media users supported Republican populists. Matthes and Heiss revealed that adolescents with stronger participatory motivations and higher levels of extraversion were more likely to follow populists on Facebook. Hameleers and Schmuck could demonstrate that populist social media posts had the potential to reinforce populist attitudes if the recipients sympathized with the source of the posts.

In summary, the special issue provides us with theoretical considerations on how populist actors may benefit from the Internet (Krämer). The contributions offer us insights into how political leaders (Bracciale & Martella, Waisbord & Amado) and extreme parties (Ernst et al.) use populist online communication. The authors also show us how the populist movement PEGIDA relates to political parties (Stier et al.). We learn which groups of social media users are more susceptible to populism than others (Groshek & Koc-Michalska, Matthes & Heiss) and what effects populist online communication may have on citizens (Hameleers & Schmuck).

It is our hope that this special issue will contribute to scholarly as well as other forms of discussion regarding what is arguably one of the largest political challenges currently faced by a series of nations around the globe.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Anders Olof Larsson http://orcid.org/0000-0003-3621-4687

Notes on contributors

Sven Engesser is Senior Research and Teaching Associate at the Institute of Mass Communication and Media Research at the University of Zurich. He has received his PhD from LMU Munich. His research focuses on political communication, science communication, and media systems [email: [email protected]].

Nayla Fawzi is a post-doctoral researcher at the Department of Communication Studies and Media Research at Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich, Germany. Her research focuses on trust in the media, populism and the media, and online user behavior [email: [email protected]].

Anders Olof Larsson is Associate Professor at the Faculty of Management, Westerdals Oslo School of Arts, Communication and Technology. Larsson received his PhD from Uppsala University. His research focuses on political communication and journalism in relation to digital media [email: [email protected]].

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aalberg, T., & de Vreese, C. H. (2017). Introduction: Comprehending populist political communication. In T. Aalberg, F. Esser, C. Reinemann, J. Strömbäck, & C. H. de Vreese (Eds.), Populist political communication in Europe (pp. 3–11). London: Routledge.

- Aalberg, T., Esser, F., Reinemann, C., Strömbäck, J., & de Vreese, C. H. (Eds.). (2017). Populist political communication in Europe. London: Routledge.

- Abts, K., & Rummens, S. (2007). Populism versus democracy. Political Studies, 55(2), 405–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.2007.00657.x

- Akkerman, T. (2011). Friend or foe? Right-wing populism and the popular press in Britain and the Netherlands. Journalism, 12(8), 931–945. doi: 10.1177/1464884911415972

- Albertazzi, D., & McDonnell, D. (Eds.). (2008). Twenty-first century populism: The spectre of Western European democracy. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Altheide, D. L. (2014). Media edge: Media logic and social reality. New York, NY: Peter Lang.

- Altheide, D. L., & Snow, R. P. (1979). Media logic. London: Sage.

- Alvares, C., & Dahlgren, P. (2016). Populism, extremism and media: Mapping an uncertain terrain. European Journal of Communication, 31(1), 46–57. doi: 10.1177/0267323115614485

- Anstead, N., & Chadwick, A. (2009). Parties, election campaigning, and the internet: Toward a comparative institutional approach. In A. Chadwick & P. N. Howard (Eds.), Routledge handbook of internet politics (pp. 56–71). London: Routledge.

- Aslanidis, P. (2016). Is populism an ideology? A refutation and a new perspective. Political Studies, 64(1S), 88–104. doi: 10.1111/1467-9248.12224

- Atton, C. (2004). An alternative internet. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Bartlett, J., Birdwell, J., & Littler, M. (2011). The new face of digital populism. London: Demos.

- Bennett, W. L., & Manheim, J. B. (2006). The one-step flow of communication. Annals of the American Academy of Political & Social Science, 608, 213–232. doi: 10.1177/0002716206292266

- Bimber, B. (1998). The internet and political transformation: Populism, community, and accelerated pluralism. Polity, 31(1), 133–160. doi: 10.2307/3235370

- Bos, L., & Brants, K. (2014). Populist rhetoric in politics and media: A longitudinal study of the Netherlands. European Journal of Communication, 29(6), 703–719. doi: 10.1177/0267323114545709

- Bos, L., van der Brug, W., & de Vreese, C. (2011). How the media shape perceptions of right-wing populist leaders. Political Communication, 28(2), 182–206. doi: 10.1080/10584609.2011.564605

- Caiani, M., & Graziano, P. (2016). Varieties of populism: Insights from the Italian case. Italian Political Science Review, 46(2), 243–267.

- Canovan, M. (1999). Trust the people! Populism and the two faces of democracy. Political Studies, 47(1), 2–16. doi: 10.1111/1467-9248.00184

- Canovan, M. (2002). Taking politics to the people: Populism as the ideology of democracy. In Y. Mény & Y. Surel (Eds.), Democracies and the populist challenge (pp. 25–44). Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Carlisle, J. E., & Patton, R. C. (2013). Is social media changing how we understand political engagement? An analysis of Facebook and the 2008 presidential election. Political Research Quarterly, 66(4), 883–895. doi: 10.1177/1065912913482758

- Chadwick, A. (2013). The hybrid media system: Politics and power. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Coleman, S. (2005). New mediation and direct representation: Reconceptualizing representation in the digital age. New Media & Society, 7(2), 177–198. doi: 10.1177/1461444805050745

- Coleman, S., & Blumler, J. G. (2009). The internet and democratic citizenship: Theory, practice and policy. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Colleoni, E., Rozza, A., & Arvidsson, A. (2014). Echo chamber or public sphere? Predicting political orientation and measuring political homophily in Twitter using big data. Journal of Communication, 64(2), 317–332. doi: 10.1111/jcom.12084

- Cranmer, M. (2011). Populist communication and publicity: An empirical study of contextual differences in Switzerland. Swiss Political Science Review, 17(3), 286–307. doi: 10.1111/j.1662-6370.2011.02019.x

- Dahlgren, P. (2005). The internet, public spheres, and political communication: Dispersion and deliberation. Political Communication, 22(2), 147–162. doi: 10.1080/10584600590933160

- Davenport, T. H., & Beck, J. C. (2001). The attention economy: Understanding the new currency of business. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

- de la Torre, C. (Ed.). (2015). The promise and perils of populism: Global perspectives. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky.

- Downey, J., & Fenton, N. (2003). New media, counter publicity and the public sphere. New Media & Society, 5(2), 185–202. doi: 10.1177/1461444803005002003

- Elchardus, M., & Spruyt, B. (2016). Populism, persistent republicanism and declinism: An empirical analysis of populism as a thin ideology. Government and Opposition, 51(1), 111–133. doi: 10.1017/gov.2014.27

- Engesser, S., Ernst, N., Esser, F., & Büchel, F. (2017). Populism and social media: How politicians spread a fragmented ideology. Information, Communication, & Society, 20(8), 1109–1126. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2016.1207697

- Esser, F., Stepinska, A., & Hopmann, D. (2017). Populism and the media: Cross-national findings and perspectives. In T. Aalberg, F. Esser, C. Reinemann, J. Strömbäck, & C. H. de Vreese (Eds.), Populist political communication in Europe (pp. 365–380). London: Routledge.

- Flaxman, S., Goel, S., & Rao, J. M. (2016). Filter bubbles, echo chambers, and online news consumption. Public Opinion Quarterly, 80(S1), 298–320. doi: 10.1093/poq/nfw006

- Gamson, W. A. (2004). On a sociology of the media. Political Communication, 21(3), 305–307. doi: 10.1080/10584600490481334

- Gerbaudo, P. (2014). Populism 2.0. In D. Trottier & C. Fuchs (Eds.), Social media, politics and the state: Protests, revolutions, riots, crime and policing in the age of Facebook, Twitter and YouTube (pp. 16–67). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Groshek, J., & Engelbert, J. (2013). Double differentiation in a cross-national comparison of populist political movements and online media uses in the United States and the Netherlands. New Media & Society, 15(2), 183–202. doi: 10.1177/1461444812450685

- Hameleers, M., Bos, L., & de Vreese, C. (2016). ‘They did it’: The effects of emotionalized blame attribution in populist communication. Communication Research, online first. doi: 10.1177/0093650216644026

- Hawkins, K. A. (2009). Is Chavez populist? Measuring populist discourse in comparative perspective. Comparative Political Studies, 42(8), 1040–1067. doi: 10.1177/0010414009331721

- Herkman, J. (2017). The life cycle model and press coverage of Nordic populist parties. Journalism Studies, 18(4), 430–448. doi: 10.1080/1461670X.2015.1066231

- Hintz, A. (2015). Internet freedoms and restrictions: The policy environment for online alternative media. In C. Atton (Ed.), The Routledge companion to alternative and community media (pp. 235–246). Abingdon: Routledge.

- Inglehart, R., & Norris, P. (2016). Trump, Brexit, and the rise of populism: Economic have-nots and cultural backlash. Harvard Kennedy School Faculty Research Working Paper Series RWP16-026. Retrieved from https://research.hks.harvard.edu/publications/workingpapers/citation.aspx?PubId=11325

- Irvine, J. (2001). Style as distinctiveness: The culture and ideology of linguistic differentiation. In P. Eckert & J. Rickford (Eds.), Style and sociolinguistic variation (pp. 21–43). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Jagers, J., & Walgrave, S. (2007). Populism as political communication style: An empirical study of political parties’ discourse in Belgium. European Journal of Political Research, 46(3), 319–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6765.2006.00690.x

- Jamieson, K. H., & Cappella, J. N. (2008). Echo chamber: Rush Limbaugh and the conservative media establishment. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Jansen, R. (2011). Populist mobilization: A new theoretical approach to populism. Sociological Theory, 29(2), 75–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9558.2011.01388.x

- Klinger, U., & Svensson, J. (2015). The emergence of network media logic in political communication: A theoretical approach. New Media & Society, 17(8), 1241–1257. doi: 10.1177/1461444814522952

- Klinger, U., & Svensson, J. (2016). Network media logic: Some conceptual considerations. In A. Bruns, G. Enli, E. Skogerbø, A. O. Larsson, & C. Christensen (Eds.), The Routledge companion to social media and politics (pp. 23–38). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Koopmans, R., & Olzak, S. (2004). Discursive opportunities and the evolution of right-wing violence in Germany. American Journal of Sociology, 110(1), 198–230. doi: 10.1086/386271

- Koopmans, R., & Statham, P. (2003). Challenging immigration and ethnic relations politics: Comparative European perspectives. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Krämer, B. (2014). Media populism: A conceptual clarification and some theses on its effects. Communication Theory, 24, 42–60. doi: 10.1111/comt.12029

- Kriesi, H. (1995). New social movements in Western Europe a comparative analysis. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Kriesi, H. (2004). Strategic political communication: Mobilizing public opinion in audience democracies. In F. Esser, & B. Pfetsch (Eds.), Comparing political communication: Theories, cases, and challenges (pp. 184–212). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kriesi, H. (2014). The populist challenge. West European Politics, 37(2), 361–378. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2014.887879

- Kriesi, H., & Pappas, T. S. (Eds.). (2015). European populism in the shadow of the great recession. Colchester: ECPR Press.

- Kruikemeier, S., van Noort, G., Vliegenthart, R., & de Vreese, C. H. (2013). Getting closer: The effects of personalized and interactive online political communication. European Journal of Communication, 28(1), 53–66. doi: 10.1177/0267323112464837

- Laclau, E. (2005). On populist reason. London: Verso.

- Lanham, R. A. (2006). The economics of attention: Style and substance in the age of information. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Lee, E.-J., & Jang, J.-W. (2013). Not so imaginary interpersonal contact with public figures on social network sites: How affiliative tendency moderates its effects. Communication Research, 40(1), 27–51. doi: 10.1177/0093650211431579

- Mazzoleni, G. (2003). The media and the growth of neo-populism in contemporary democracies. In G. Mazzoleni (Ed.), The media and neo-populism: A contemporary comparative analysis (pp. 1–20). Westport, CT: Praeger.

- McAdam, D. (1982). Political process and the development of black insurgency, 1930–1970 (2nd ed.). Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

- Mény, Y., & Surel, Y. (2000). Par le peuple, pour le peuple: Le populisme et les démocraties. Paris: Fayard.

- Mény, Y., & Surel, Y. (2002). The constitutive ambiguity of populism. In Y. Mény & Y. Surel (Eds.), Democracies and the populist challenge (pp. 1–21). London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Moffitt, B., & Tormey, S. (2014). Rethinking populism: Politics, mediatisation and political style. Political Studies, 62(2), 381–397. doi: 10.1111/1467-9248.12032

- Mudde, C. (2004). The populist zeitgeist. Government and Opposition, 39(4), 542–563. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-7053.2004.00135.x

- Mudde, C., & Rovira Kaltwasser, C. (2012a). Populism and (liberal) democracy: A framework for analysis. In C. Mudde & C. Rovira Kaltwasser (Eds.), Populism in Europe and the Americas: Threat or corrective for democracy? (pp. 1–26). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Mudde, C., & Rovira Kaltwasser, C. (Eds.). (2012b). Populism in Europe and the Americas: Threat or corrective for democracy? New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Newman, N., Fletcher, R., Levy, D., & Nielsen, R. K. (2016). Reuters institute digital news report 2016, from http://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/Digital-News-Report-2016.pdf

- Oliver, J. E., & Rahn, W. M. (2016). Rise of the Trumpenvolk: Populism in the 2016 election. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 667(1), 189–206. doi: 10.1177/0002716216662639

- Pariser, E. (2011). The filter bubble: What the internet is hiding from you. New York, NY: Penguin Press.

- Pfetsch, B., Adam, S., & Bennett, W. L. (2013). The critical linkage between online and offline media. Javnost-The Public, 20(3), 9–22. doi: 10.1080/13183222.2013.11009118

- Reinemann, C., Aalberg, T., Esser, F., Strömbäck, J., & de Vreese, C. H. (2017). Populist political communication: Toward a model of its causes, forms, and effects. In T. Aalberg, F. Esser, C. Reinemann, J. Strömbäck, & C. H. de Vreese (Eds.), Populist political communication in Europe (pp. 12–25). London: Routledge.

- Rheingold, H. (1993). The virtual community: Homesteading on the electronic frontier. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Rooduijn, M. (2014). The mesmerising message: The diffusion of populism in public debates in Western European media. Political Studies, 62(4), 726–744. doi: 10.1111/1467-9248.12074

- Rooduijn, M., De Lange, S. L., & Van der Brug, W. (2014). A populist zeitgeist? Programmatic contagion by populist parties in Western Europe. Party Politics, 20(4), 563–575. doi: 10.1177/1354068811436065

- Schulz, A., Müller, P., Schemer, C., Wirz, D., Wettstein, M., & Wirth, W. (2017). Measuring populist attitudes on three dimensions. International Journal of Public Opinion Research. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1093/ijpor/edw037

- Shirky, C. (2008). Here comes everybody: The power of organizing without organizations. New York, NY: Penguin Press.

- Shoemaker, P. J., & Cohen, A. A. (2006). News around the world content, practitioners, and the public. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Shoemaker, P. J., & Vos, T. P. (2009). Gatekeeping theory. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Stanyer, J. (2008). Elected representatives, online self-presentation and the personal vote: Party, personality and webstyles in the United States and United Kingdom. Information, Communication & Society, 11(3), 414–432. doi: 10.1080/13691180802025681

- Sunstein, C. R. (2001). Republic.com. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Taggart, P. (2000). Populism. Buckingham: Open University Press.

- Taggart, P. (2002). Populism and the pathology of representative politics. In Y. Mény & Y. Surel (Eds.), Democracies and the populist challenge (pp. 62–80). Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Vaccari, C., & Valeriani, A. (2015). Follow the leader! Direct and indirect flows of political communication during the 2013 Italian general election campaign. New Media & Society, 17(7), 1025–1042. doi: 10.1177/1461444813511038

- van Kessel, S., & Castelein, R. (2016). Shifting the blame: Populist politicians’ use of Twitter as a tool of opposition. Journal of Contemporary European Research, 12(2), 594–614.

- Weyland, K. (2001). Clarifying a contested concept: Populism in the study of Latin American politics. Comparative Politics, 34(1), 1–22. doi: 10.2307/422412

- Williams, B. A., & Delli Carpini, M. X. (2011). After broadcast news: Media regimes, democracy, and the new information environment. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Wirth, W., Esser, F., Wettstein, M., Engesser, S., Wirz, D., Schulz, A., …, Schemer, C. (2016). The appeal of populist ideas, strategies and styles: A theoretical model and research design for analyzing populist political communication. Working Paper 88 of the NCCR Democracy at the University of Zurich. Retrieved from http://www.nccr-democracy.uzh.ch/publications/workingpaper/wp88

- Xenos, M., Vromen, A., & Loader, B. D. (2014). The great equalizer? Patterns of social media use and youth political engagement in three advanced democracies. Information, Communication & Society, 17(2), 151–167. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2013.871318