ABSTRACT

According to narrative trends, digitalization has the potential to deconstruct both power structures and practices of exclusion in society. What we argue here is that this deconstruction is not the result of digitalization alone, it is dependent on how digitalization is done. On the contrary, digitalization has often resulted in reproduction instead of transformation and deconstruction, i.e. digitalization tend to uphold practices instead of challenging them. Being slightly more provocative, what becomes digitalized is often what we can easily capture and understand. Similarly, when we open up for an increased participation in the creation of digital artifacts (sometimes expressed as demand-driven, citizen-centered, or participatory development), those participating in digitalization are often already known; the use of already established contact channels making them easy to reach and connect with. Such logics raise questions about the intersections of norms and power and the potential transformative character of digitalization. The aim of this paper is to, through a theoretical framework combining critical information systems, policy enactment and norm critical design, introduce a reflexive design method to gently provoke norms. We analyze the need to intervene in the everyday practices of digitalization. This is done in an empirical case study of the making of a regional digital cultural heritage portal. The results indicate that digitalization needs norm critical interventions to change existing practices and prevent norm reproduction. Otherwise, as in this case of the digitalization of cultural heritage, digitalization runs the risk of strengthening existing power structures and excluding practices instead of challenging them.

Introduction

The digitalization of cultural heritage is a multifaceted and complex area associated with the hope and expectation that participation will increase (Enhuber, Citation2015), and a belief that it has a unifying potential. What is included and embraced as cultural heritage ‒ or not ‒ is a delicate issue (Macdonald, Citation2006), and the question of who is invited and incorporated in its becoming is equally challenging. For decades, the EU countries have been trying to establish a shared ‘European’ cultural identity in line with the European project. Issues of exclusion and inclusion in relation to this goal have surfaced and touched upon the complexity of the process (Hansen, Citation1998; Morley & Robins, Citation2002; Shore, Citation2013; Stolcke, Citation1995). This intricacy is valid not only on the European level, but also in every cultural project seeking to establish something ‘common and shared’ since the ‘shared’ presupposes the ‘other’, i.e., an ‘otherness’ (Hallam & Street, Citation2013; Kearney, Citation2005). According to Morley and Robins (Citation2002), this suggests that power, boundary marking, and exclusion processes are key areas that need to be addressed in any attempt to create a cultural identity. An awareness of the practices that either support or question the taken-for-granted cultural identities that are being reproduced is, thus, essential.

One such practice, with a growing influence, is digitalization, where several working groups and guidelines have been established in recent years (see for example the Digital Preservation Europe Project). There is a multitude of initiatives aiming to make cultural identities digitally accessible. The professional knowledge in the cultural sphere is as such translated and connected to digitalization practices, which have long been rather unaware of norm-critical perspectives (Cecez-Kecmanovic, Klein, & Brooke, Citation2008). However, the understanding that digital artifacts both carry and strongly mediate certain values and norms is a growing area in disciplines of digitalization, and a field labeled critical design has emerged. Interesting contributions have been made by for example Bardzell and Bardzell (Citation2013), Dunne and Raby (Citation2001), Lundmark and Normark (Citation2012) as well as Lundmark, Normark, and Räsänen (Citation2011), who have analyzed norm-critical design efforts and explored how normative perspectives are embedded in interaction design. Nonetheless, research on this issue is still in its infancy and rare in information systems design practices. Even though information systems research and informatics draw heavily upon several social sciences, the explicit link between norm critique and design knowledge is still rather marginalized. Issues of power, inscriptions, and emancipation have been raised since the 1970s, yet critical perspectives have been marginalized (see for example Akrich, Citation1992). In order to enhance the critical perspectives, there has been a call for more practice-oriented guidance on reflexive design activities as a way to scrutinize rules, norms, and taken-for-granted assumptions in digitalization processes (see for example Friedland & Yamauchi, Citation2011; Grin, Felix, Bos, & Spoelstra, Citation2004).

This article draws upon the tradition in the information systems (IS) discipline that focuses on interpretation, enactment, and technological frames in relation to digital technologies in the making (Orlikowski, Citation1992: Orlikowski & Gash, Citation1994). The aim of the paper is to contribute to the more general discussion of digitalization and power structures; not as in giving a fixed answer to whether digitalization automatically questions existing power relations or actually amplifies them but as in how we could understand the mechanisms in order to be more aware of how they act.

In order to do so, we will first present the theoretical position we see as a good starting point in terms of earlier research on digitalization and power. Design theoretically as in when and how power is inscribed in digital technologies, critical information systems research as a rather well-established field questioning interpretations and representations inscribed in digital technologies and finally earlier research on participatory practices in design processes. Since those theoretical positions often are accused of being too abstract and seldom provide practical guidance in the methodological section, we present a three-step exercise highly inspired by two practitioners in norm critique. This exercise serves as bridge in between theoretical underpinnings and ways of both gathering and analyzing empirical material and provoke and intervene in the empirical context. The two following sections show the results and relate them back to how this might be a contribution to the general aim but also the specific context.

The paper is structured as follows: first, the theoretical positioning and chosen analytical framework are described. The following section explores the methodological choices and the empirical settings. Next, the results of the empirical interventions are presented, and some tentative results are discussed. Finally, the last section presents the overall discussion, along with conclusions and contributions.

Theoretical positioning and analytical framework

Norm-critical IS suggests that design processes are not understood only as practices of realizing the expressed or translated needs of a client. It is highlighted that we also need ways of addressing the design limitations ‘outside’ the specific setting, including social structures, culture, economy, and institutional prerequisites. These limitations are often already in place when designers enter the scene, and they often impinge more strongly upon design choices than is admitted. This makes it interesting to create a deeper understanding of the nature of normative constructs (e.g., the enactment process of policies) for a more reflective design (Schön, Citation1987; Stolterman, Citation2008). The basic assumption is that actual design activities are more restricted by perceptions, notions, and ideas of possible futures than recognized when analyzing design practices. They are rarely deliberative conscious, or elaborated upon, and they could hide behind formal and socially accepted norms with reference to development paths and possible futures. However, they will nevertheless be unveiled during their creation. Rules, norms, knowledge claims, distinctions, and assumptions are reproduced through institutional practices, project logics, and financial models, and we need to critically scrutinize their impact (Grin et al., Citation2004).

In the making of digital technology, highlighting, elaborating, and analyzing these conscious and unconscious notions and ideas creates a platform and a structure from which to take constructs and situated meanings into account. Since there are competing constructs of meaning, it is important to critically analyze ‘the taken for granted’ rather than uncritically accepting ideas simply because they are put forward by authorities as being ‘true’. This results in a pre-design analysis phase that is not related to developing conceptual frameworks, but to creating tools for understanding limitations (taken-for-granted assumptions) on a more general level. Such a pre-design analysis phase does not serve as a bridge between ‘technological research at the concept stage and social research at the impact stage’ (Venable, Citation2006), but as a bridge between social research at the understanding stage and technological research at the design stage.

This paper, therefore, is linked to the critical tradition in IS research of questioning existing forms of knowledge production and, especially, hegemonic discourses that are taken for granted, as well as their embodiment in different processes. In this context, it is in line with Orlikowski and Baroudi’s (Citation1991) understanding of the critical stance as shining a light on taken-for-granted assumptions with the objective of exposing deep-seated structures. Also Walsham’s (Citation1993) emphasis on construction, enactment, and historical and cultural contingencies is a part of the critical IS tradition. It is also an attempt to contribute to the call for more practice-oriented methods to help and guide practitioners to reflect upon the inherited constraints reproduced if not highlighted, which was requested by Grin et al. (Citation2004) and Friedland and Yamauchi (Citation2011).

In order to comprehend and analyze the interpretations, visualizations, negotiations, and choices made ‘before’ or ‘outside’ the often-circumscribed depiction of design, it is argued that a more deconstructive understanding is needed. IS design is often viewed as a constructive and sometimes prescriptive practice (Iivari, Citation2007), with the objective of making representations of a wanted future ‒ or, in this case, a wanted shared cultural heritage ‒ and creating digital artifacts that support these representations and evaluate and justify their existence (Hevner, March, Park, & Ram, Citation2004). These assemblages are not obviously understood as design representations; however, in the long-term, they restrict and frame the scope of our digital future. We are acknowledging the political, ideological, strategic, economical, and other heavily normative practices surrounding IS designers in their professional undertakings in different ways (Löwgren & Stolterman, Citation2004). At the same time, it is important to make the actors on these levels visible and to make it possible to relate the pre-stages of design to power imbalances. As discussed briefly above, the translations made by IS designers are not without context, and there are boundary conditions that affect a designer’s possibilities, autonomy, and scope (see e.g., Haraway, Citation1988).

This is related to an established tradition in IS research that focuses on the social, organizational, and political nature of IT development (e.g., Avison, Kendall, & DeGross, Citation1993; Baskerville et al., Citation1994; Hirschheim & Klein, Citation1989; Hirschheim & Newman, Citation1991; Markus, Citation1983; Myers, Citation1995; Myers & Young, Citation1997; Newman & Robey, Citation1992; Walsham, Citation1993; Walsham & Waema, Citation1994) and the growing field of critical studies (e.g., Cecez-Kecmanovic, Citation2001; Howcroft & Trauth, Citation2005; McGrath, Citation2005; Myers, Citation2004). In this area of IS research, there are several objectives, such as questioning (i) economic-technical rationalism, (ii) technology-driven development models, and (iii) positivistic superiority in terms of valuable knowledge (Lyytinen, Citation1992, p. 168). Another objective is to enhance empirical critical studies (Cecez-Kecmanovic et al., Citation2008). As such, there are critical responses to the ideological nature of how our everyday social and cultural experiences are mediated by digital artifacts. Calhoun (Citation1995, p. xviii) describes this critical approach as seeking ‘to explore the ways in which our categories of thought reduce our freedom by occluding recognition of what could be’. Questioning the established assumptions inherent in a design situation opens up design spaces and is critical for two reasons: (i) it questions the taken-for-grantedness of a design and (ii) it reveals possibilities for transformative redefinition.

In addition to what has illustrated above, there is yet another category of actors (beyond the specific designers, the decision-makers, and the practitioners in cultural institutions) that must be included, since digitalization is argued to increase possibilities of public participation (Deuze, Citation2006; Van Hooland, Citation2006). According to Van Hooland (Citation2006), the role of users in digital media is changing, not only through increased participation, but also through a gradual shift from users as passive consumers towards users as proactive participants that reorganize and manipulate content. The same type of trend is claimed to be taking place in the development of public sector administration (often labeled ‘eParticipation’) and democracy (often labeled ‘eDemocracy’) (Macintosh, Citation2004; Sæbø, Rose, & Skiftenes Flak, Citation2008). In this field, the concept of e-Governance has emerged as a platform to improve digital access to cultural heritage (Paskaleva-Shapira, Azorín, & Chiabai, Citation2008). With the emergence of the idea of digitalization as a tool for accessibility and participatory practices (as in eDemocracy and eParticipation) (Macintosh, Citation2004; Sæbø et al., Citation2008), digitalization of cultural heritage must also be viewed not only as an existing artifact, but also as an on-going doing in terms of who will participate in deciding what is to be labeled cultural heritage and what is not, and on what terms.

However, there are few studies focusing on how such participation is distributed (Sefyrin, Citation2012; Gidlund, Citation2015). This raises questions such as: is everybody equally included, equally welcome, equally skilled, and equally able to access opportunities to participate? If it is true that participation increases both in number and in power, a critical perspective involves concerns about representational practices in digitalization. Our take on this follows that which was presented by Calhoun (Citation1995), which is based on the Marxian idea of partial participation: that participation is often communicated as if it is universal and inclusive (e.g., across such categories as customers, clients, users, and citizens), but involves a priority of certain identities at the expense of others (Gidlund, Citation2015). Calhoun (Citation1995) argues that, behind ‘the rhetoric of universality’, we find white men with technological skills. Cleaver (Citation2004, p. 271) talks about ‘over-optimistic notions of agency combined with romantic ideas about groups and institutions’, where, in fact, participation is definitely partial and, as such, is both enabled and constrained (Cleaver, Citation2004, p. 271). In short, the idea of increasing public participation needs to be scrutinized from several perspectives.

In conclusion, the analytical framework of this study is based on a combination of a critical IS agenda, the call for more practice-oriented guidance for reflexive design doings, and a norm-critical interventionist ambition (in search for possibilities for transformative redefinitions). Furthermore, the argument is that design understandings benefit from what is here called ‘pre-design analysis’. A pre-design analysis is what often precedes and surrounds that which is traditionally viewed as the design context, i.e., the restrictions of norms that are taken-for-granted, cultures, social structures, and institutional prerequisites. This framework is combined with a critical stance on the notion of participation that questions the rarely challenged idea that an open door means that everyone will enter.

Methodological choices and empirical setting

In order to be able to create a deeper understanding of the nature of normative constructs (e.g., the enactment process of policies), we directed our attention to possibilities to disrupt the current order and provoke the taken-for-granted perceptions. This is also in line with Schön (Citation1987) and Stolterman (Citation2008), who discuss designing in a more reflective manner, where the basic assumption is that actual design doings are more restricted by perceptions, notions, and ideas of possible futures than we acknowledge when analyzing design practices. As such, policy enactment and norm-critical design reflections act together as a theoretical base for our methodological choices.

Based on a norm-critical design understanding (Dunne & Raby, Citation2001), we searched for more interventionist methodologies in terms of co-constructing new ways of understanding what is articulated and by whom, as well as what could be articulated and by whom (Zuiderent-Jerak & Bruun Jensen, Citation2007). Since identity-oriented representational practices often tend to reproduce stereotypical identities (Sefyrin, Danielsson Öberg, Ekelin, & Gidlund, Citation2013), we have chosen to focus on excluding and including practices from an institutional perspective, letting the practitioners on the ‘inside’ question their ability to include and invite other representations of cultural heritage.

The aim was to find methods to be able to discuss the taken-for-granted underlying assumptions in the design process and relate them to what becomes a representation of cultural heritage in the digitalization process. This is a way to find other possible enactments, translations, and alternatives. In addition, as argued by Cecez-Kecmanovic et al. (Citation2008) and Calhoun (Citation1995), there is a need for more empirically oriented norm-critical studies and our ambition grew to not only study and analyze norm reproduction but also to try to find a method or tool that could be used to challenge norm reproduction in its doing, i.e., contribute to practitioners.

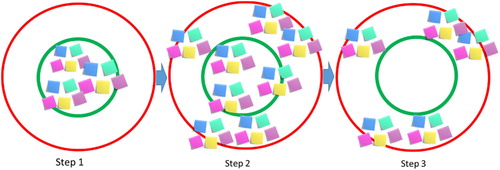

Greatly inspired by an exercise created by two practitioners in norm creativity (Vinthagen & Zavalia, Citation2014) called ‘the norm circle’, which consists of two steps, we developed a three-step exercise (also used in other research projects not yet published). The third step added is more intervention-oriented, including analysis of possible action space ().

The three steps can be briefly described as follows:

Step 1: We asked the participant to fill the inner circle with what and who is included in everyday practices (positioned inside the norm circle). This in order to visualize what and who is included in the everyday making of cultural heritage, i.e., the norm reproduction.

Step 2: We asked the participants to identify what and who is excluded in everyday practices (positioned outside the norm circle). This in order to start a process of reflecting upon the inclusion/exclusion practices.

Step 3: We removed what and who was placed inside (that is in step 1) and gave the participants the opportunity to discuss and reflect the new image. Then we started to discuss how to include the excluded. This in order to identify the participants’ action space for what and who is positioned outside the norm in their everyday practices.

Table 1. Informants.

The portal is owned by a regional network consisting of collaborating institutions including the County Administrative Board, the county museum, the county library, and the National Archive (located in the region). Its funding has changed over time; it has been funded by both EU funding and received economic support from the local municipality, as well as the County Administrative Board. Key actors from all collaborating institutions were represented at the workshop. The actors were either directly involved in the everyday practices of the digitalizing the cultural heritage of the region or involved at the regional policy level.

Each step in the exercise was carried out twice; the first round focused on what becomes digital cultural heritage (is displayed on the web portal), and the second focused on who are part of making and contributing to what ends up on the web portal. We started out with the three steps focusing on the question what is cultural heritage and then repeated the same steps in connection to who does or does not do cultural heritage. For each step, approximately 1 hour is required; it is especially important to make sure that there is sufficient time for the last step, so that it is not rushed through. It is in the third step that the identification of action space and possibilities for transformative redefinition takes place. In the following section, we will describe the exercise and the steps in more detail and briefly mention the effects of the workshop in the group

Intervention: to provoke the norm

In this empirical setting, in the first step, the workshop participants were asked to write down representations of: ‘what is cultural heritage’ in their everyday practice and stick the notes in the inner circle on the whiteboard. This was done by asking the participants to take about 5 minutes to individually contemplate the question:

What is made into cultural heritage today (note the verb form: ‘is’) (step 1)?

This question was used in order to direct their thoughts to their everyday practices, how digital cultural heritage is talked about, and what digital cultural heritage is supported by institutional settings. When the participants stuck their post-it notes to the whiteboard, they had the opportunity to elaborate on notes in more detail. The idea of this exercise was for the group to develop a shared understanding of the big picture based on the post-it notes.

In the next step of the exercise, the following question was asked:

What does not become cultural heritage (step2)?

In this step, the focus was on what does not become cultural heritage based on the current working methods and processes in the participants’ everyday working life. Just like with the first question, the participants wrote their answers on post-it notes, but this time they were asked to place them in the outer/surrounding circle. This part of the exercise revealed which parts of our cultural heritage are not so easily ‘made into’ a part of our official cultural heritage. It also showed why the verb ‘is’ is important; i.e., what we believe and claim ‘is’ cultural heritage could differ from what actually ‘becomes’ cultural heritage. This served as a starting point for a discussion about the underlying assumptions restricting the design space that are rarely deliberate or conscious.

When both the inner and surrounding circle were filled with post-it notes, we removed all the post-it notes from the inner circle. While doing so, the participants were asked to approach to the white board.

When gathered in front of the white board, the participants were asked to analyze how their everyday practices are currently preventing what was placed ‘outside’ the norm in the exercise. This was done by asking the following questions (step 3):

What does it mean to completely focus on that which ‘does not become’ digital cultural heritage?

What would have to change in current working methods and processes to expand the (official) representation of a region’s heritage?

In this step, it was important to let the participants be active by the whiteboard, to move the post-it notes around, draw arrows and write suggestions and ideas on how to alter existing practices and discuss amongst themselves. Also important was to talk about identifying possible action space (i.e., possibilities for transformative redefinition), to visualize what is possible to accomplish in everyday policy enactment and what is embedded in a larger structure beyond the individual. In order to balance the structural aspects of design limitations and individualization of responsibility, we included a discussion about social structures, culture, economy, and institutional prerequisites. It was also important for us as workshop leaders to listen carefully and, together with the participants, allow small changes to existing practices to be made visible.

Following this discussion, the now empty space in the inner circle was filled with numerous suggestions from the participants about how to include other stories (which were previously located in the outer circle) of what cultural heritage is and also to include other actors in the making of cultural heritage.

The process was then repeated, this time with a focus on who ‘is’ taking part in making digitalized cultural heritage: who takes part? Who does not take part? How could those not currently taking part be included?

In both processes (regarding both ‘what is’ and ‘who does’ digitalized cultural heritage), the participants commented quite anxiously that what had been placed in the inner circle was being ‘so easily removed’. Step 3 was perceived as visually descriptive, and the void that was created by the removal of the post-it notes made the distinction between what is supported by everyday practices and what is not very clear.

Norm-critical reflexivity ‒ what was learned?

The use of the above-mentioned three-step method had some very interesting results. First, the use of the norm-critical reflexive methodology reveals that removing ‘what already exists’ (from the inner norm circle) was a strongly visual experience for the participants. The participants commented on a strange feeling, as well as feeling uneasy and provoked when the inner circle was emptied. We responded that what is already institutionalized by existing working methods and processes does not require further focus. But in order to make room for that which ‘is outside’ the (inner) norm (circle), the participants needed to let go of what was inside the inner circle. We asked them to leave the objects of the inner circle behind and relax in the knowledge that these objects are already secured through existing working procedures and processes. In other words, the removal of these items did not mean that they were lost; it meant that they were done anyway. However in our case, the participants still felt as if the parts of cultural heritage upheld by existing practices ‘disappeared’. For example, one participant said:

… it becomes so obvious when everything in there is gone …

The participants suggested that they often, in their everyday working practices, begin with what is ‘inside’; only if time and other resources are available, what is ‘outside’ is taken into consideration:

To start by taking ‘what is already done’ away instead of just adding and adding makes the process manageable

The reflexive methodology also revealed that even though all of the participants had a broad definition of what cultural heritage is or could be and who ‘makes’ cultural heritage, the focus was on that which was within the norm circle. What was outside the norm was left with whatever space remained. One of the participants explains this by saying:

You don’t think much about what it isn’t, about that which does not become [cultural heritage] …

To define what ‘is not’ cultural heritage helps me figure out what it actually is.

Furthermore, the reflexive methodology, combining policy enactment and critical IS, made the project clarify the logic behind the digital cultural heritage portal. The methodology during the workshop put into focus the project funding the portal and its specific outcomes. The reflexive methodology revealed the project logic, in which the results were almost fully formulated prior to the start of the project. Thus, the participants discussed how short funding periods prevent the inclusion of the unknown and what is outside of the norm. The informants said:

Project funding often controls the formulations …

During the workshop, it became obvious that the use of the reflexive methodology created a significant insecurity among the key actors. The methodology reveals how difficult it is to challenge everyday practices, to question interpretations of policy, and to open up the concept of cultural heritage. As a result of the methodology of these activities, the participants began to question the concept itself:

Maybe we should call it something else. People don’t recognize themselves in the concept of cultural heritage …

It’s so difficult […] We ask them if they want to be a part of the project, but [they] don’t want to …

Conclusions and contributions: everything disappears …

The aim of this paper was twofold: (i) to contribute to the area of norm-critical IS design in general by presenting a method that strengthens practitioners’ abilities to reflect on how their everyday work practices reproduce established norms and (ii) to contribute to the specific understanding of digitalizing cultural heritage by raising questions about what becomes, and who makes, digital cultural heritage. Therefore, the guiding research question was what are the translations, in everyday practices, of how digitalization of cultural heritage is made and how can we gently provoke these norms?

Regarding the first aim, our view is that the theoretical construct of a combination of a thorough understanding of the interpretative character of IS design (including norms, social structures, and institutional prerequisites), the acknowledgement of policy enactment together with norm-critical interventionist perspectives was successful as a way to put forward a quite simple and concrete tool for more reflexive design processes. The policy enactment and interpretative frame views fed on each other and as such pinpointed the structural contextual factors influencing design choices which would otherwise be hard to link to everyday practices. The reflexive methodology sparked a variety of reflections among the participants, in addition to clarifying what is in fact not supported or made visible ‒ and, therefore, is not becoming cultural heritage ‒ as well as who is currently not supported or involved in the making of cultural heritage. The methodology as such could be described as an exercise that helps practitioners to identify openings and action spaces in digitalization processes in order to resist uncritical reproduction of un-reflected everyday practices. It is also an answer to the calls for more practical guidance in how to gather and analyze empirical material on the relation in between digitalization and power structures, i.e., perform critical studies in the information systems field.

The exercise raised an awareness among the workshop participants about when the norm and the majority are given almost all the space, and what happens to minorities (i.e., the ‘others’ or the non-majorities; the ones outside the inner circle) when they are finally addressed and invited. In other words, the minorities and their perspectives become ‘additions’ so to speak. Ultimately, the participants identified that the norm is, after all, the starting point. The process of letting what they consider to be ‘outside’ becomes the starting point for their everyday practices ‒ and simultaneously allowing themselves to recognize that the majorities are so well-established in current working methods that they are automatically monitored ‒ shifted the perspectives of the participants. Placing what they consider to never or rarely be represented as cultural heritage in the center spaces created openings in an otherwise fairly rigid order which would otherwise have been difficult to penetrate. This also applies to objects considered to be included as digital cultural heritage; objects easily accessible and easily perceived as cultural heritage travels more smoothly in established working forms and they also become the starting point. In this way, excluding everyday practices become more visible and they have to start searching for action space, using their everyday working practices to include rather than exclude.

An interesting result is that the participants perceived it as almost threatening to remove the what and who that is currently included in their everyday practices put it to the side; even though the likelihood that this displacement would seriously threaten the norm is very small. The idea that the norm is already so established and upheld by current everyday practices that it does not need to be monitored is challenging. What is interesting is that even though such displacement creates opportunities and spaces for more people to make their voices heard in terms of what representations of cultural heritage there are and should be. This is the strongest contribution of this study; the participants’ reaction when what was placed in the norm (the inner circle) was taken away; their response was that they felt as if ‘everything disappeared’. Which leads to the conclusion that they perceived the norm as ‘everything’. This paints a strong picture of how powerful unreflected norms are and how ingrained they are in current everyday digitizing work practices. Most importantly, it illustrates the importance of unveiling and disturbing these norms if the ambition is to prevent the digitalization of cultural heritage from becoming the exclusive heritage of the majority and the established.

Regarding the overall research question, the results indicate that digitalization needs norm-critical interventions, such as reflexive design, to open up existing spaces and prevent norm reproduction. We would also argue that the proposed exercise is generic; the three-step model enhances the understanding of how norms are represented in terms of design choices. The strength of the model is that three steps easily visualize the effect of everyday practices, which creates awareness and possibilities for interventions. Otherwise, as in this empirical case regarding digitalization of cultural heritage, digitalization runs the risk of strengthening current power structures and exclusion practices, instead of challenging them, which is very topical in Europe today.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Dr Sara Nyhlén is a political scientist working at Forum for Gender Studies at Mid Sweden University. She has a research interest of power, normalization and intersectionality. She is using a variety of qualitative methods and often focuses on policy analysis and policy enactment. She is currently working in a post doc project concerning migration among the most deprived EU-citizens [email: [email protected]].

Professor Katarina Lindblad Gidlund is a professor in informatics and here research interests are critical studies of digital technologies and societal change. She is appointed by the Swedish government as a member of the Usability Council and a member of the editorial board of the International Journal of Public Information Systems. She is a program committee member of International conference of EGovernment (EGOV) [email: [email protected]].

Additional information

Funding

References

- Akrich, M. (1992). The de-scription of technical objects. In W. E. Bijker & J. Law (Eds.), Shaping technology building society (pp. 205–224). Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Avison, D. E., Kendall, J. E., & DeGross, J. I. (Eds.). (1993). Human, organizational, and social dimensions of information systems development, Amsterdam.

- Bardzell, J., & Bardzell, S. (2013). What is critical about critical design? Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on human factors in computing systems (pp. 3297–3306). ACM.

- Baskerville, R., Smithson, S., Ngwenyama, O., & DeGross, J. (1994). Transforming organizations with information technology: proceedings of the IFIP WG8.2 working conference on information technology and new emergent forms of organization, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA, 11-13 August, 1994 North Holland, Amsterdam, Holland. ISBN 9780444819451.

- Calhoun, C. (1995). Critical social theory: Culture, history, and the challenge of difference. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Cecez-Kecmanovic, D. (2001). Doing critical IS research: The question of methodology. Qualitative Research in IS: Issues and Trends, 141–162.

- Cecez-Kecmanovic, D., Klein, H. K., & Brooke, C. (2008). Exploring the critical agenda in information systems research. Information Systems Journal, 18(2), 123–135.

- Cleaver, F. (2004). The social embeddedness of agency and decision-making. Participation ‒ from Tyranny to Transformation? Exploring New Approaches to Participation in Development, Zed Books.

- Deuze, M. (2006). Participation, remediation, Bricolage: Considering principal components of a digital culture. The Information Society, 22(2), 63–75.

- Dunne, A., & Raby, F. (2001). Design noir: The secret life of electronic objects. Springer Science and Business Media.

- Enhuber, M. (2015). Art, space and technology: How the digitisation and digitalisation of art space affect the consumption of art ‒ a critical approach. Digital Creativity, 26(2), 121–137.

- Friedland, B., & Yamauchi, Y. (2011). Reflexive design thinking: Putting more human in human-centered practices. interactions, 18(2), 66–71.

- Gidlund, K. L. (2015). Makers and Shapers or users and choosers participatory practices in digitalization of public sector. International Conference on Electronic Government (pp. 222–232). Springer International Publishing.

- Grin, J., Felix, F., Bos, B., & Spoelstra, S. (2004). Practices for reflexive design: Lessons from a Dutch programme on sustainable agriculture. International Journal of Foresight and Innovation Policy, 1(1–2), 126–149.

- Hallam, E., & Street, B. (Eds.). (2013). Cultural encounters: Representing otherness. Routledge.

- Hansen, P. (1998). Schooling a European identity: Ethno-cultural exclusion and nationalist resonance within the EU policy of ‘The European dimension of education’. European Journal of Intercultural Studies, 9(1), 5–23.

- Haraway, D. (1988). Situated knowledges: The science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective. Feminist Studies, 14(3), 575–599.

- Hevner, A., March, S., Park, J., & Ram, S. (2004). Design science in information systems research. MIS Quarterly, 28, 75–105.

- Hirschheim, R., & Klein, H. K. (1989). Four paradigms of information systems development. Communications of the ACM, 32(10), 1199–1216.

- Hirschheim, R., & Newman, M. (1991). Symbolism and information systems development: Myth, metaphor and magic. Information Systems Research, 2(1), 29–62.

- Howcroft, D., & Trauth, E. M. (Eds.). (2005). Handbook of critical information systems research: Theory and application. Aldershot: Edward Elgar.

- Iivari, J. (2007). A paradigmatic analysis of information systems as a design science. Scandinavian Journal of Information Systems, 19(2), 39–63.

- Kearney, R. (2005). Strangers, gods and monsters: Interpreting otherness. London: Routledge.

- Löwgren, J., & Stolterman, E. (2004). Design av informationsteknik, materialet utan egenskaper. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Lundmark, S., & Normark, M. (2012). Reflections on norm-critical design efforts in online youth counselling. Proceedings of the 7th Nordic Conference on Human-Computer Interaction: Making Sense through Design (pp. 438–447). ACM.

- Lundmark, S., Normark, M., & Räsänen, M. (2011). Exploring norm-critical design in online youth counseling. 1st International Workshop on Values in Design–Building Bridges between RE, HCI and Ethics.

- Lyytinen, K. (1992). Information systems and critical theory. In M. Alvesson & H. Willmott (Eds.), Critical management studies (pp. 159–180). London: Sage Publications.

- Macdonald, S. (2006). Undesirable heritage: Fascist material culture and historical consciousness in Nuremberg. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 12(1), 9–28.

- Macintosh, A. (2004). Characterizing e-participation in policy-making. In System Sciences, 2004. Proceedings of the 37th Annual Hawaii International Conference on (10 pp). IEEE.

- Markus, M. L. (1983, June). Power, politics, and MIS implementation. Communications of the ACM, 26(6), 430–444.

- McGrath, K. (2005). Doing critical research in information systems: A case of theory and practice not informing each other. Information Systems Journal, 15, 85–101.

- Morley, D., & Robins, K. (2002). Spaces of identity: Global media, electronic landscapes and cultural boundaries. London: Routledge.

- Myers, B. A. (1995, March). User interface software tools. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction, 2(1), 64–103.

- Myers, M. D. (2004). Hermeneutics in information systems research. In J. Mingers & L. P. Willcocks (Eds.), Social theory and philosophy for information systems (pp. 103–128). Chichester: Wiley.

- Myers, M. D., & Young, L. W. (1997). Hidden agendas, power, and managerial assumptions in information systems development: An ethnographic study. Information Technology and People, 10(3), 224–240.

- Newman, M., & Robey, D. (1992). A social process model of user-analyst relationships. MIS Quarterly, 16(2), 249–266.

- Orlikowski, W. (1992). The duality of technology: Rethinking the concept of technology in organizations. Organization Science, 3(3), 398–427.

- Orlikowski, W. J., & Baroudi, J. J. (1991). Studying information technology in organisations: Research approaches and assumptions. Information Systems Research, 2(1), 1–28.

- Orlikowski, W. J., & Gash, D. C. (1994). Technological frames: Making sense of information technology in organizations. ACM Transaction on Information Systems, 12, 174–207.

- Paskaleva-Shapira, K., Azorín, J., & Chiabai, A. (2008). Enhancing digital access to local cultural heritage through e-governance: Innovations in theory and practice from Genoa, Italy. Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research, 21(4), 389–405. doi:10.1080/13511610802568031.

- Sæbø, Ø, Rose, J., & Skiftenes Flak, L. (2008). The shape of eParticipation: Characterizing an emerging research area. Government Information Quarterly, 25(3), 400–428.

- Schön, D. (1987). Educating the reflective practitioner. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Sefyrin, J. (2012). From profession to practices in IT design. Science, Technology and Human Values, 37(6), 708–728.

- Sefyrin, J., Danielsson Öberg, K., Ekelin, A., & Gidlund, K. L. (2013). Representational practices in demands driven development of public sector. International Conference on E-Government, the conference proceedings of Springer LNCS volume 7444, Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg.

- Shore, C. (2013). Building Europe: The cultural politics of European integration. London: Routledge.

- Stolcke, V. (1995). Talking culture: New boundaries, new rhetorics of exclusion in Europe. Current Anthropology, 36, 1–24.

- Stolterman, E. (2008). The nature of design practice and implications for interaction de-sign research. International Journal of Design, 2(1), 55–659.

- Van Hooland, S. (2006). From spectator to annotator: Possibilities offered by user-generated metadata for digital cultural heritage collections. Immaculate Catalogues: Taxonomy, Metadata and Resource Discovery in the 21st Century, Proceedings of CILIP Conference.

- Venable, J. (2006, February 24). The role of theory and theorising in design science research. In S. Chatterjee & A. Hevner (Eds), First International Conference on Design Science Re-search in Information Systems and Technology, Claremont, CA. Claremont, CA: Claremont Graduate University.

- Vinthagen, R., & Zavalia, L. (2014). Normkreativ, Premiss Förlag, Halmstad.

- Walsham, G. (1993). Interpreting information systems in organizations. New York, NY: Wiley.

- Walsham, G., & Waema, T. (1994, April). Information systems strategy and implementation: A case study of a building society. ACM Transactions on Information Systems, 12(2), 150–173.

- Zuiderent-Jerak, T., & Bruun Jensen, C. (2007). Editorial introduction: Unpacking ‘intervention’ in science and technology studies. Science as Culture, 16(3), 227–235.