ABSTRACT

This paper examines two large-scale cases ‒ the 2013 Boston bombing and the 2015 Bangkok bombing, each of which spurred an online investigation conducted by concerned citizens to find the bombers. While both bombing cases had different cultural discourses, the processes and outcomes of the online investigation were similar: there were rampant speculation and rumor-mongering, as well as false accusations and harassment of innocent suspects. The aim of the paper is to understand how such acts of mob justice happened. Using actor–network theory, a theoretical and methodological tool for mapping out the networks human and non-human interactions, I discuss two types of networks found in both investigations. The two network types demonstrate how a claim can be construed as fact or fiction through such networks of interaction. In light of debates on the proliferation of fake news and alternative facts, the findings have implications for the current and precarious state of truth in today’s society.

Introduction

‘Truth’ in today’s society is currently at the center of a number of debates, and the process by which people ‘reach’ the truth has become increasingly important to study. Collective intelligence is a model of collaborative knowledge-making on the internet that aims to discern the ‘truth’. Online communities on various social media platforms have attempted to use collective intelligence to resolve social injustices. However, success is not always guaranteed. Such efforts are often thwarted by emotion, lack of information, and an inclination to rumor-monger. Moreover, there are complicated interactions with institutional authorities such as the police or mass media. This paper examines two large-scale mob justice efforts carried out by those online during the 2013 Boston bombing and the 2015 Bangkok bombing. While both bombing cases had different cultural contexts, the processes and outcomes of the online investigations were similar: collective intelligence failed on both fronts, resulting in the obscuration of the truth, false accusations, and harassment against innocent bystanders. Using actor–network theory (ANT), I discuss two types of networks that demonstrate how a claim can be construed as fact or fiction. In light of debates on the proliferation of fake news and alternative facts, the findings have implications for the current and precarious state of truth in today’s society.

Background

Boston bombing

On 15 April 2013, two pressure cooker bombs exploded near the finish line of the 117th annual Boston marathon, resulting in three deaths while injuring 264 others (Wilson, Miller, & Horwitz, Citation2013). As people tried to make sense of the shocking tragedy, RedditFootnote1 became a focal point of the incident.

Reddit was a major source of information for those interested in the bombing. Updates were continuously posted in live-update threads housed within the r/news and r/inthenews subreddits.Footnote2 r/findbostonbombers was soon created, partly fueled by the FBI’s call for information, photos, and videos from the public. Whether or not it meant to, r/findbostonbombers became part of a vigilante witch-hunt to find the bombers. As Redditors combed through photos and videos, innocent people were named, shamed, and harassed. This doxxingFootnote3 and dissemination of private information led to criticism of r/findbostonbombers. Despite the thousands of people involved, Reddit failed to identify the correct suspects, exemplifying a catastrophic failure in collective intelligence efforts. The FBI eventually identified the Tsarnaev brothers, Tamerlan and Dzhokhar, as the bombing suspects (NBC News, Citation2016). Alexis Ohanian, Reddit co-founder, called it one of the most important events in Reddit history as it demonstrated the ‘the gift and the curse’ of such a democratic and open platform (Nicks, Citation2013).

Two years later, another bombing occurred in a completely different country but with surprisingly similar trajectories.

Bangkok bombing

On 17 August 2015, a bomb exploded at the revered Erawan Shrine during the evening rush hour in the heart of downtown Bangkok, Thailand, killing 20 and injuring 125 others. In the minutes following the attack, reports of the incident spread online. While the world watched as the Thai police conducted a messy and haphazard investigation (Tribute Wire Reports, Citation2015), another parallel investigation occurred in Facebook and Thailand’s Reddit equivalent: Pantip.Footnote4

Dubbed the ‘keyboard sleuths’ or ‘social media sleuths’ by Thai news media (Middleton, Citation2015; NewsAsia, Citation2015), Thai netizens gathered footage and photos, and discussed facts and theories. During the course of the unofficial investigation, the netizens doxxed and shamed many people. Like Reddit, the Thai keyboard sleuths failed to identify the Bangkok bomber and caused more headaches for the state authorities, who were already wading through mounds of misinformation and false leads. In the end, the Thai police arrested two of the bombers, Yusufu Mieraili and Adem Karadag, who were Uyghurs protesting Thailand’s repatriation of asylum-seeking Uyghur Muslims back to China (Fuller & Wong, Citation2015).

While mob justice has historical roots tracing back to medieval witch hunts, the internet and its tools for communication and information gathering has elevated mob justice to a new, unprecedented level of breadth and efficacy. The two bombing cases, set in different years, different countries and cultures, provide a compelling comparison to understanding how the online community uses the collective intelligence tools of the internet to pursue social justice.

Literature review

Collective intelligence and the amateurization of knowledge

Web 2.0 is the internet we know today. While the phrase may seem archaic, as there are debates about Web 3.0, the impact of Web 2.0 cannot be overstated. The rise of user-generated content, and tools that encourage the democratization of knowledge, have changed the world, transforming the way we deal with information, communication, and much more. It has spurred globalization and created new opportunities for the passive internet user of the past to be active, productive, and creative (Brake, Citation2014; Dimaggio et al., Citation2001; Lessig, Citation2009; Ritzer & Jurgenson, Citation2010).

Armed with the tools of Web 2.0, internet users can be a powerful collective. Scholars have analyzed the effects of Web 2.0 on knowledge production and distribution on the web. Hargadon and Bechky (Citation2006) studied innovation-oriented online creative consumer communities or IOCCs (i.e., communities of creative consumers that engage in production), and how they group together as a community through activities such as help-seeking and help-giving. In other words, these types of creative communities turn to one another for help, instead of turning to experts or opinion leaders. IOCCs truly demonstrate how the internet has transformed knowledge production.

What IOCCs rely on is the power of collective intelligence, whether they are a brand community (Muniz & O’Guinn, Citation2001) or a fan community (Jenkins, Citation2006). The phrase ‘collective intelligence’ is defined by Pierre Levy (Citation1999, p. 13) as ‘a form of universally distributed intelligence, constantly enhanced, coordinated in real time, and resulting in the effective mobilization of skills … No one knows everything, everyone knows something, all knowledge resides in humanity’. Other terms such as ‘cognitive surplus’ (Shirky, Citation2010), ‘collaborative knowledge’ (Stahl, Citation2006), and ‘crowdsourcing’ (Brabham, Citation2012) are perspectives that stem from collective intelligence. In essence, knowledge can be created not just from one individual, but from the collaboration of many, including non-human sources such as automated content agents or bots (Niederer & Dijck, Citation2010). The key question in this matter is the true effectiveness of collective intelligence.

There are arguments supporting and criticizing the collective intelligence model, but the majority of the research supports it in a cautious yet optimistic fashion. Malone and Klein (Citation2007) believe that collective intelligence could be used for greater societal good, for example, encouraging action to address climate change. In politics, Landemore (Citation2017) has demonstrated that the knowledge of the collective can be accurate as it removes individual emotions and biases, thus making a strong case for democratic political action. Research on disaster aftermath has shown that social media provides an essential platform for collective intelligence to gather information for those seeking help or updates (Silver & Matthews, Citation2017). While misinformation may exist, Silver and Matthews (Citation2017) have found that the online community tends to correct itself. Yet despite the online community’s best efforts to fact-check itself, misinformation occurs because of the very nature of an open collective intelligence model. This is an element that previous research has overlooked.

Wikipedia, often cited as the most successful example of collective intelligence, exemplifies this issue. With its ‘free encyclopedia’ tagline, it is based on an ‘openly editable content’ model in which any user can contribute knowledge, whether they are an expert or amateur (Wikipedia, Citation2017). As more people contribute, the information should become more accurate. Users can fact-check each other, thereby steering articles away from potential biases, judgments, and political leanings (Shirky, Citation2011). However, while Wikipedia is an exemplary model for collective intelligence, it is not without its faults and missteps.

This is of particular concern when Wikipedia users attempt to create articles for an ongoing event. On 22 March 2017, a man drove a car into a crowd of pedestrians in London, injuring over 50 people and killing three. Online sleuths believed they identified the assailant to be Abu Izzadeen, because he had been charged for committing terrorism before (Scott, Citation2017). His name was shared widely on Twitter, Facebook, and even a British news program; his Wikipedia entry was subsequently updated to reflect the new information. However, he was not the assailant; he was actually in prison at the time of the attack. ‘The public naming of Mr. Izzadeen was a troubling reminder that fact and fiction can be hard to separate in a breaking news event’ (Scott, Citation2017). In cases where speed of information, emotional anguish, and the desire for social justice muddle together, collective intelligence often fails.

Collective intelligence and mob justice efforts, therefore, do not seem to mesh well. Collective intelligence is powerful, but can often be swayed by outside factors, such as interactions with institutional players. As Phillips (Citation2013, p. 503) study on 4chan has shown, there is an ‘amplificatory relationship between trolls and the mainstream media’. Online communities do not exist in isolation from the outside world, thus complicating the process of collective intelligence and in turn, social justice efforts.

The human flesh search engine

The literature surrounding the relationship between mob justice and collective intelligence is mostly concentrated in China. By trusting in the so-called ‘wisdom of the crowd’, internet users in China engage in what is called the ‘human flesh search engine’ (HFSE). It is ‘the act of searching for information about individuals through the online collaboration of multiple users’ (Pan, Citation2010, p. 2). The HFSE uses the collective intelligence model to solve a social injustice or exact punishment on a perceived violator of the laws and norms of society (Gao & Stanyer, Citation2013). Motivated by a desire for ‘truth’ and ‘justice’ in a country of high censorship and corruption (Ong, Citation2012), the HFSE is often enacted to fight ‘unethical yet lawful behaviors’ in China (Tao & Chao, Citation2011, p. 2). A primary example is the ‘kitten killer’ case.

In 2006, photos of a woman stomping a kitten to death with high heels were posted online (‘China’s online vigilantes’, Citation2008). Outraged and frustrated that the law could not prosecute the unknown woman, the HFSE crowdsourced their resources and skills to dox her. They subsequently exposed her real name, occupation, workplace, and home address. She was harassed and eventually fired from her job. This case exemplifies the very physical and psychological consequences of the HFSE, causing scholars to doubt its potential as a ‘manifestation of citizen empowerment and civil participation’ (Tao & Chao, Citation2011, p. 1).

The HFSE has roots much older than the internet, as acts of mob justice date back to medieval European witch hunts and lynchings in America. However, the internet has added a new level of complexity to an old form of social control. In addition to the research in China, there have been a few studies done in South Korea, Taiwan, Japan, and the United States (Ronson, Citation2016; Tao & Chao, Citation2011). Cases such as the Dog Poop girl and Justine Sacco’s harassment demonstrate the global occurrence of mob justice. The cases that have been studied often represent scenarios where collective intelligence is successful, allowing the internet to be the judge, jury, and executioner by engaging in vigilante justice.

While previous research on the HFSE can illuminate the motivation behind mob behavior, there has been no systematic and convincing analysis of the processes that lead to the failure of collective intelligence. There is a dearth of research on cases where collective intelligence fails, and the internet mob ends up targeting an innocent suspect. Cases such as the London terror attack are examples of the online collective behaving as though they hold the same institutional knowledge and authority as the police and the court system, while failing to identify the correct perpetrator. When collective intelligence fails, and the mob points its finger at an innocent person, what is happening? What do the networks of interactions look like between the various actants involved in mob justice efforts? Using the Boston and Bangkok bombing as comparative case studies, I use actor–network theory to map out the notable networks of interaction.

Methods

Data collection

The main source of data for the Boston bombing was Reddit. Data from 15 April (the day of the bombing) to 22 April 2013 (the day the Tsarnaev brothers were arrested) were collected. The subreddits included were – r/news, r/inthenews, and r/findbostonbombers. There were 21 live-update threads total within r/news and r/inthenews that had at least 200 comments. Fifteen threads from r/findbostonbombers with over 200 comments were collected through Archive-It (https://archive-it.org/) a service that crawls through the internet and collects daily snapshots of millions of web pages. The 100 most liked comments were sampled from each of the 36 threads, totaling 3600 comments for the content analysis.

The Bangkok bombing involved two social media channels: Pantip and CSI LA, a public Facebook group that gained notoriety for previously failed crowdsleuthing efforts in Thailand (despite the seemingly American name). Data from 16 August (the day before the bombing) to 30 September 2015 (when the Thai police made an arrest) were collected. The Pantip data were collected manually through keyword searches ranging from ‘Bangkok bombing’, ‘RatchaprasongFootnote5 bombing’, ‘Ratchaprasong blast’, and other such variations. There were seven relevant Pantip threads with at least 100 comments for sampling, yielding 700 Pantip comments.

To collect data from CSI LA, I used a free scraping app called NetVizz, which is a tool that is able to extract data from particular Facebook groups or pages (Rieder, Citation2013). Thousands of comments were collected, leading me to sample the top 100 comments from 26 relevant posts, totaling 2600 comments.

Both the Boston and Bangkok data collection, therefore, yielded a similar number of comments to analyze (3600 and 3300, respectively). All the usernames in the data were anonymized and assigned an ID# in chronological order.

Data analysis

The initial method of analysis was conventional content analysis, which is a useful qualitative tool for generating thematic codes and patterns directly from textual data (Hsieh & Shannon, Citation2005). While the content analysis results are outside of the scope of this paper, the thematic categories and in-depth analysis highlighted the cultural context of the bombings as well as the sequence of events (Pantumsinchai, Citation2017). The results paved the way for a fruitful actor–network theory analysis (ANT), which is the focus of this paper.

Actor-network theory

ANT is both a theory and a method. It is a constructivist approach which does not assume that there are grand truths or larger social structures; rather, it is purely concerned with the observable interactions within a social network (Latour, Citation2005). ANT treats everything in the ‘social and natural worlds as a continuously generated effect of the webs of relations within which they are located’ (Law, Citation2009, p. 141). There is no methodological distinction between human and non-human actants (Sismondo, Citation2009). It is a bottom-up, materialist approach analyzing how networks are built via observable interactions between human and non-human actants.Footnote6 Both types of actants have agency, and are equally capable of affecting a network (Latour, Citation2005; Nimmo, Citation2011).

According to ANT, the goal of networks is to become stable (Law, Citation2009). Our understanding and experience of social reality come from networks which have been stabilized due to long-standing interactions between various actants. An important factor allowing for the stabilization of networks is discourse. Law (Citation2009), one of the founders of ANT, talks about ‘discursive stability’. Discourses are what allows the initial claims to be possible in the first place; Law calls (Citation2009) this the ‘conditions of possibility’. Discourses allow certain interpretations of events to appear to be ‘truthful’ or ‘commonsensical’ via ideological codes (Smith, Citation1999). In other words, claims are not drawn out of thin air. Claims are based in existing networks of discourse within society, allowing said statements to be plausible, acceptable, and sensible.

An ANT-based approach, therefore, allows researchers to qualitatively describe the observable interactions in a network of human and non-human actants, while reducing the social world to material connections. ANT can help explain how claims become facts as they connect to sources within the network. From the time when society believed the earth was round to now, when scientists are debating the realities of climate change, ANT can show how a claim that was true one day and supported by a whole network can be false the next (Besel, Citation2011). Using ANT’s principles and methods, I mapped out two types of networks that were apparent in both the Boston and Bangkok bombings: blackboxed and the feedback loop. Each network was responsible for disseminating false claims while establishing other claims as truth.

Findings

ANT is used here to map out how claims made online (e.g., rumors, conjectures, and theories) move through a network comprised of media coverage, police statements, and social media channels to eventually be considered fact, although networks do not always get to the point where they are stabilized; disruptions can occur, and the networks can collapse.

The Findings section is organized into two subsections for each network type: blackboxed and the feedback loop. These two networks occurred at key turning points during the bombings, such as when an innocent person was accused. When an innocent person is harassed, it is when the mob justice and collective intelligence efforts are failing. As the current research is interested in how exactly such efforts at justice fail, mapping out the process of claims-making is important to understanding the basis and trajectories of the accusations.

Network type: blackboxed

The first network, blackboxed, demonstrates what a robust and stabilized network that has been taken for granted looks like. In such a network, the claim has moved through multiple interactions between humans and non-human actors and has been universally accepted as ‘fact’. Such a network represents the process of blackboxing.

Blackboxing is an ANT concept derived from engineering. In its original use, blackboxes referred to devices with unknown inner workings. For example, a computer is a blackbox in and of itself; and when one opens up the tower, there are a number of black boxes within that, which have an input and output. It is not necessary to actually understand exactly what is going on within those blackboxes as long as they function properly for the computer. As the methodology of ANT was developed, sociologists wanted to merge the division between science and technology (hence, the birth of the field of science and technology studies). Pinch and Bijker (Citation1993, p. 14) in particular wanted to ‘open the so-called blackbox in which the workings of technology are housed’. ANT scholars wanted to seriously consider how material objects and the technologies that created them affected human relationships, hence, the emphasis on non-human actants. Scholars wrote about the blackbox technologies of bicycles, telephones, television, electric cars, and more (Callon & Latour, Citation1981; Pinch & Bijker, Citation1993).

As thought developed, blackbox moved from being about material technologies. Scholars began studying how facts and knowledge were constructed by networks of human and non-human interactions, thereby constituting social reality (Callon & Latour, Citation1981; Pinch & Bijker, Citation1993). Blackbox was used to refer to contained social processes that society tended to overlook and take for granted. Callon and Latour (Citation1981) discussed how the idea of electric cars replacing gasoline cars became common sense in France during the 1970s, due to the workings of a corporation called Electricité de France. In their seminal book, Laboratory Life (Citation1986), Latour and Woolgar discussed the construction of scientific facts through a complex network of interactions between laboratories, researchers and scientists, and publishers. Scientific facts, though considered ‘facts’, are still supported by a network of humans and non-humans. Once a piece of knowledge is considered factual, it is essentially blackboxed, because people no longer question why it is a fact; society simply accepts it. (There can be counter-arguments from people in other competing networks, hence, the current debate on climate change. (See Besel, Citation2011).

The two meanings of blackbox are therefore related, though with different emphases on material versus non-material cultures. Blackboxes once meant material objects that people took for granted, but scholars eventually adapted the term to analyze the cultural and scientific knowledge that people took for granted. In my theoretical use of the term, I am focused on the latter meaning, as the network graphs in and represent the social construction of knowledge. The knowledge disseminated within the actor–network during the bombings not only are taken for granted, when the network is stabilized, such knowledge is further reified as ‘truth’.

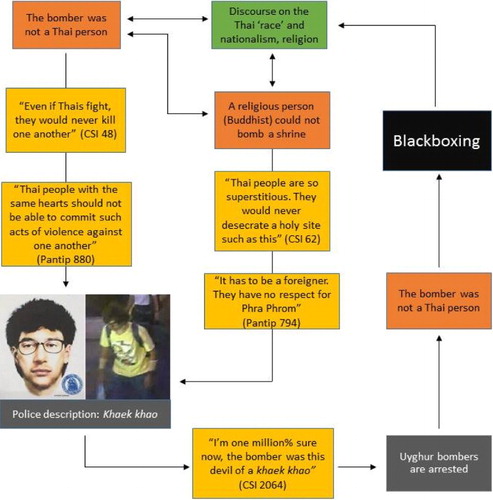

In , there are two statements made online that need to be examined. The beginning statement (starting in the top left corner) is ‘the bomber is not a Thai person’. The second statement is ‘a religious person (Buddhist) could not bomb a shrine’. Both statements were made in CSI LA and Pantip in the aftermath of the bombing, as the Thai people tried to make sense of what had happened.

From the very beginning of the unofficial investigation, the netizens were adamant in their belief that the bomber was not a Thai person. Moreover, as the site of the bombing was a place of significant religious worship, it was deemed unlikely, if not impossible, that a Thai person could have bombed a holy site. However, the two statements were made in the context of existing nationalist discourse within the Thai nation-state. In order to understand the conditions of possibility for such statements, we must understand Thailand’s history.

Despite being a multi-ethnic and racially diverse country, Thailand has strong hegemonic discourses regarding what characteristics constitute a ‘true Thai’. As part of a racist nationalist project carried out by the Thai government in the 1930s, the idea of a unified ‘Thai race’ was perpetuated through the ideology of cultural nationalism (Winichakul, Citation2008). Cultural nationalists believed that there was a ‘natural’ and ‘common’ culture across all Thai people. To be a ‘true Thai’, one must speak the Thai language, adopt Buddhism, love the Thai monarchy, and trust the military authority which governed the country during the 1930s (and not so coincidentally, was also governing the country during the 2015 bombing) (Thananithichot, Citation2011). Most importantly, a person embodying the ‘essence of Thainess’ must have nam jai (the value of caring and having kindness for one another), and live by ideals of communal solidarity and harmony (Connors, Citation2005; Winichakul, Citation2008).

Cultural nationalism remains a strong ideological driving force in Thailand today. Based on such discourses, the two statements in were made possible and deemed acceptable by the Thai online community. Many people believed that a Thai person could not hurt another Thai person, despite a long history of internal disputes and political coups (Fisher, Citation2013). Since all ‘true’ Thais must be Buddhist, and no Buddhist could destroy a religious site, the bomber could not have been a Thai person.

We now understand how the original two claims were made possible based on existing discourse in Thailand. The two claims supported one another, hence the bi-directional arrow. The quotes from CSI LA and Pantip reflect the general discussion online that helped to support the network. The more people agreed, the more factual the claims seemed to be. The statements were further confirmed when the sketch of the Yellow Shirt Suspect was released by the police, coupled with a description that the man was foreign (i.e., not Thai) and of khaek khao Footnote7 descent. The sketch and CCTV footage are non-human actants in the network that mediate an interaction between the authorities and the online community. Official confirmation that the bomber was not Thai, made the claims even stronger. This made sense to the public; as a ‘true Thai’, one who is religious and loves harmony, could not hurt another Thai person, much less bomb a shrine. The network completes itself at this point when the Uyghur is arrested is made, and the claims are ‘blackboxed’ – that is, fully becomes fact, to the point where it is taken for granted. Now that the ‘facts’ have been supported by networks of people, images, and institutional players, they feed into the existing discourse on the Thai race and identity.

As a result of this stabilized network, a number of non-Thais were accused and harassed by the online community. While it was correct that the bombers were not Thais, the blackboxed network became the basis for the online community’s mob mentality against innocent foreigners.

Non-human actants

Latour (Citation2005) argues that non-human actants must be made visible in the actor–network. Non-humans also have agency, and are capable of affecting change within the actor–network. Nimmo (Citation2011, p. 112) explains that agency, a concept typically reserved for humans, is actually ‘an emergent property of networks and inter-relationships between heterogeneous actants’. Non-human actants therefore, not only allow for mediation between human actants, they also are the basis for human practices.

For ANT there is no ‘society’ as such, in the sense of a domain consistent exclusively of relations between human subjects, as these relations are always mediated and transformed and even enabled by nonhumans of diverse kinds, whether objects, materials, technologies, animals or eco-systems. (Nimmo, Citation2011, p. 109)

Nimmo (Citation2011) extends that to include historical texts in her study on the purification of dialog around milk production.

An ANT analysis, therefore, is not complete without a proper acknowledgement of non-human actants. is mostly comprised of human actants – the quotes from CSI LA and Pantip all represent the armchair detectives. Due to space constraints, every non-human actant could not be portrayed. A key non-human actant that is represented is the police sketch of the yellow shirt suspect. In the network, the police sketch connects individuals within the CSILA and Pantip network with one another, and provides a way for the overall network to progress towards blackboxing. The word khaek khao the police used to describe the bombing suspect also became an actant itself, as the very word changed the way the human actors in the network perceived and understood the case. The word has an agency of its own, and subsequently affected the network.

Previous studies such as Besel (Citation2011) and Nimmo (Citation2011) have shown that discourse can also be a part of the actor–network, in that it provides the conditions of possibility. Therefore, the discourse on the Thai race and nationalism, which itself is made up of a slew of networks dating back through Thailand’s political history, constitutes a non-human actant in and of itself.

Other non-human actants not clearly represented are the computers and mobile devices that connect people online to this case. Without the internet and its cables, along with its social media services such as Facebook, Pantip, Twitter and more, the armchair detectives would also not have a way to connect to one another. Essentially, computer-mediated communication technologies are important non-human actants that enable the human connections made in the case. Devices such as security cameras, CCTV, phone cameras all constitute the actor–network, and provide further non-human actants such as photographs, surveillance videos, screenshots, etc. News articles on the Bangkok bombing connected people to the network. When the links to the articles were shared on social media, they became a non-human actant. Without these non-human actants to enable connections and affect change within the network, the entire unofficial investigation would not have happened at the scale and speed that it did, if at all.

The blackboxed network is a primary example of how a claim based in preexisting discourse can become stabilized through a network of human and non-human interactions, to eventually be perceived as fact or truth. The second network, however, is quite the opposite.

Network type: the feedback loop

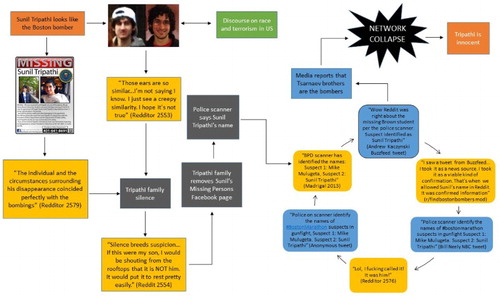

, the feedback loop, represents the most complex network in the two cases as it captures the relationship between traditional news media and online communities. takes place after the FBI had identified the Boston bombers in surveillance photos but did not know their identities. The FBI released the photo to the public () and asked for help in identifying the names of the men. This caused individuals that looked similar to the men in the photos to be targeted by Reddit. One key suspect was Sunil Tripathi, a college student who had gone missing a month before the bombing.

Figure 3. FBI released images of the Boston bombing suspects (Johnson, Leger, & Strauss, Citation2013).

Tripathi became a suspect when a Redditor posted about his status as a missing person. It quickly caught on as many believed that Tripathi disappeared in order to plan and carry out the bombing. Where Tripathi went missing was also in close proximity to the bombing area. There was also indication that Tripathi had been depressed before his disappearance, leading Redditors to believe that he matched the temperament of an extremist. Moreover, there were heated debates over whether or not Tripathi physically resembled one of the men in the FBI photos (who was actually Dzhokhar Tsarnaev). An old high school classmate of Tripathi’s even tweeted a comment regarding Tripathi’s resemblance to Dzhokhar, further fueling the rumor (Madrigal, Citation2013). Tripathi would fast become the most well-known suspect in the Reddit investigation, though he was innocent.

Starting at the top left of , the claim, ‘Sunil Tripathi looks like the Boston bomber’, is based on his missing person poster and images doxxed from his personal Facebook page. Similar to the preexisting discourses that led Thai netizens to believe that a Thai person could not have carried out the bombing, there were preexisting racist and terrorist discourses informing Redditors’ accusations against Tripathi.

Since the September 11th terrorist attacks and the declaration of the ‘war on terror’ in 2001, the US has passed legislation to combat terrorism. Those of Middle Eastern descent were not only legislative targets, they also became cultural targets with the exacerbation of racist ideologies (Poynting & Mason, Citation2007). Such ideologies created a divisive boundary between insiders and outsiders of the country, where outsiders were seen as a threat to ‘American ideals’ and ‘American-ness’ (Greenwald, Citation2013).

This process of othering has resulted in the essentialization, stereotyping, and objectification of the victims of such racist discourse. ‘The concept of “Americans” most definitely does not include people with foreign and Muslim-sounding names like “Anwar al-Awlaki” who wear the white robes of a Muslim imam and spend time in a place like Yemen’, explains Greenwald (Citation2013). Those of Middle Eastern descent with non-‘American’ sounding names and non-‘American’ physical features were often generalized to be terrorists or Islamic extremists. The very notion that one was a Muslim could lead to discrimination, as the religious identity and racial identity have become mixed up in the general wave of Islamophobia (Bravo López, Citation2011). ‘Islamophobia would be a hostile attitude towards Islam and Muslims based on the image of Islam as an enemy, as a threat to “our” well-being and even to “our survival”’ (Bravo López, Citation2011, p. 569). The media in the United States has also engaged in the dissemination of moral panics by criminalizing Muslim communities (Bravo López, Citation2011; Poynting & Mason, Citation2007).

It is no surprise then, that those of Middle Eastern descent are now often stereotyped as Islamic extremists or terrorists. The accusation against Tripathi falls under such racist discourse related to terrorism in the United States, which created the conditions of possibility for the accusation.

The claim was further stabilized as the Tripathi family remained silent in the wake of the accusations against their missing son. Facing incredible harassment from online trolls, the family deleted the Find Sunil Tripathi Facebook page. These two actions were considered a sign of guilt by those online – if Tripathi was truly innocent, why did they not speak up? The final clinch in Tripathi’s supposed guilt as the bomber was when Redditors heard his name being spoken on the Boston police scanner. This is a point of great contention and debate, as many people said they heard Tripathi’s name being spoken, while just as many maintained that they never heard Tripathi’s name. Regardless of whether or not his name was actually mentioned, the mere possibility was enough to send the Reddit community, and those observing it, into a frenzy.

At this point, the feedback loop begins. As denoted by the circular portion on the right-hand side of , the network is no longer spread out but feeding into itself. When Redditors began claiming that they heard Tripathi’s name on the scanner and celebrating that they were the first to identify the bomber, mainstream media channels such as BuzzFeed and CBS began retweeting the information on Twitter. Not only were the mainstream media checking on Reddit, they also believed Reddit’s claim about the scanner. While no one could produce a soundbite from the police scanner speaking Tripathi’s name, the claim was credible enough, due to the already existing and stabilized network (the situation revolving around Tripathi’s disappearance, the supposed physical similarities, and the actions of the Tripathi family). Moreover, the police was a highly trustworthy and legitimate source.

Receiving confirmation from the media and the police was enough to validate Reddit’s original claim. For Reddit, the stability of the network seemed widespread across various actants, yet, in reality, the network was an illusion. Instead of a robust network, the network was a loop, feeding into itself. The claim only gained more traction as high-profile Twitter accounts with millions of followers such as the hacktivist collective, Anonymous, and celebrity news reporter Perez Hilton retweeted the information. At this point, the claimed seemed factual, and various players celebrated Reddit’s successful collective intelligence.

Similar to the blackboxed network in , the feedback loop in does not have enough space to depict all the non-human actants in the network. Similar non-human actants are also at play in this network – the photographs of the suspects, the discourse surrounding race and terrorism in the United States, the internet and its cables, social media websites, Sunil Tripathi’s missing persons Facebook page, mobile phones, computers, security cameras, CCTV footage, and news articles about the bombing are active non-human actants. Additionally, has some other non-human actants, such as the non-action and silence of the Tripathi family. While the Tripathi family were human actants, their very silence became a non-human actant, as people read into the silence as signs of guilt. The police scanner was also a non-human actant, one that dramatically affected change in the network by setting off the entire feedback loop.

Within the feedback loop, statements made by individuals took on a life of their own and constituted non-human actants. Quotes about Sunil Tripathi’s name being heard on the police scanner being retweeted on Twitter showed how the very texts themselves took on a life of their own, outside of the individual who created the text. This harks back to Nimmo’s (Citation2011) argument on the power and agency of texts in actor–networks. Non-human actants are ever-present and influential in both and .

Reddit’s celebration did not last long. After the police shootout with the suspects in Watertown, Massachusetts, NBC reported on the true identity of the bombers: brothers Tamerlan and Dzhokhar Tsarnaev. The revelation of this fact immediately caused the circular network to collapse. With further confirmation from the police and the media that the bombers were actually the Tsarnaev brothers, the network that Reddit believed to be robust was dismantled. The original claim was thus modified to indicate Tripathi’s innocence. The discovery of Tripathi’s body not long after the whole debacle was further proof of his innocence, as his death was ruled to be a suicide.

Discussion and conclusion

What and demonstrate is that claims go through networks with many shapes and paths when becoming factual. ANT has demonstrated that there are no objective‘facts’. Facts are heavily embedded in a network of beliefs, discourses, imagery, statements, and of course, people, be it individuals or institutional bodies. If the network becomes robust enough, it can be maintained, stabilized, blackboxed, thus forming society’s so-called ‘common sense’. However, there is always the possibility for the network to collapse if new information or new actants enter the network. Even blackboxed statements may be unraveled and revealed to be ‘false’. Such is the shifting and evolving nature of networks and ‘truth’.

There is more to the stories of the two bombings, but ultimately, both bombing cases failed in their quest to find the perpetrators. The two network types apparent in both cases demonstrate how a single investigation can yield both facts and falsehoods. Even if the first network, blackboxed, demonstrates how there can be grains of truth in the armchair investigations, it does not necessarily yield desirable end results. The feedback loop network demonstrates how easy it is to see something as truthful even when it is a house of cards. Collective intelligence was seen as the online community’s greatest strength, and many hoped that with thousands of minds and eyes debating all the possibilities and scanning all the available imagery, the amateur investigations would be successful. While social media can be useful for disaster information seeking (Silver & Matthews, Citation2017) or politics (Landemore, Citation2017), the argument for armchair detectives is more complicated. As the online communities became the source for accurate and updated news for those interested in the bombings, there was pressure on them to be more reliable than mass media. And if, by chance, those online could succeed in finding the bombers before the FBI or the Thai police, it would have been lauded as the greatest achievement of collective intelligence. Such are the underlying motivations not discussed in Hargadon and Bechky’s (Citation2006) IOCCs. Within the amateur bombing investigations, knowledge has become equated with ‘truth’, which is problematic.

Moreover, the ANT network maps have shown that the various claims made by the online communities were based on existing discourses that clouded their judgment. An additional element that was not represented in the ANT diagrams is the sheer urgency of both cases. With the fear that the bombers could escape before being apprehended, those online felt rushed to identify the bombers as fast as possible, at the risk of making mistakes and sacrificing the truth. Finally, the interactions between the online communities and surrounding institutional players proved to be complicated elements considering the feedback loop, in which false information is propped up as the ‘truth’.

The ANT analysis of the bombings therefore depicts how difficult it is to discern the ‘truth’. By mapping out the path through which claims made online become factual, it is easy to see how precarious the nature of ‘truth’ is. Claims with robust networks of support from non-human actants (images, videos, and discourse) and human actants (online community members and members of the press) easily collapsed and were revealed to be unsubstantiated. In the end, the seesaw nature of the ‘truth’ is the biggest obstacle for collective intelligence on the internet, and for society in general. Truth is socially constructed, subjective, precarious, and everchanging. If ‘truth’ can be easily swayed, how can collective actions at social justice such as the HFSE be effective? The potential for collective intelligence as a form of citizen empowerment is doubtful in light of these findings

If a claim for the truth has a strong network of interactions backing it, those in the network will see it as truth. The internet is particularly powerful at connecting networks to larger groups of actants, stabilizing the networks even farther. In the same way that collective intelligence uses the collaborative knowledge of many to discern the ‘truth’, the ‘truth’ itself relies on the network of actants to maintain its status. With this understanding, it is clear how issues such as fake news and alternative facts have gained traction in American society (Graham, Citation2017; Stelter, Citation2016). The truth is as truthful as we want it to be.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes on contributor

Penn Pantumsinchai is a Sociology lecturer within the University of Hawaii system. She earned her Ph.D. in Sociology from the University of Hawaii at Manoa. Her research interests include the internet (online communities, social media), consumption, and social justice issues. She is a co-host of The Social Breakdown podcast (thesocialbreakdown.com) [email: [email protected]].

Notes

1 Reddit, the self-proclaimed ‘front page of the internet’ is a social news aggregator where people can submit content to be discussed and ranked by the community (Reddit, Citation2016).

2 Subreddits are interest-based communities and are demarcated by [r/subreddit-title].

3 ‘Doxxing’ or document tracing is the act of looking up personal information (either through legal or illegal means) and then posting said information online.

4 A discussion board similar to Reddit and one of the most popular websites in Thailand (Hongladarom, Citation2000).

5 The downtown intersection where the Erawan Shrine is located.

6 The terms ‘actors’ and ‘actants’ are used interchangeably as is common in various ANT research (Nakajima, Citation2013).

7 Khaek as a standalone word is often used to refer to ethnic Indians, while khao is the color white. Combined, it is a phrase used to refer to light-skinned Muslims from South and Central Asia or the Middle East.

References

- Besel, R. D. (2011). Opening the “Black Box” of climate change science: Actor-network theory and rhetorical practice in scientific controversies. Southern Communication Journal, 76(2), 120–136. doi: 10.1080/10417941003642403

- Brabham, D. (2012). The myth of amateur crowds: A critical discourse analysis of crowdsourcing coverage. Information, Communication & Society, 15(3), 394–410. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2011.641991

- Brake, D. R. (2014). Are we all online content creators now? Web 2.0 and digital divides. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 19(3), 591–609. doi: 10.1111/jcc4.12042

- Bravo López, F. (2011). Towards a definition of Islamophobia: Approximations of the early twentieth century. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 34(4), 556–573. doi: 10.1080/01419870.2010.528440

- Callon, M., & Latour, B. (1981). Unscrewing the big leviathan; or how actors macrostructure reality, and how sociologists help them to do so? In K. Cetina & A. V. Cicourel (Eds.), Advances in social theory and methodology (pp. 277–303). Boston, MA: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

- China’s online vigilantes: Virtual carnivores. (2008). The Economist.

- Connors, M. K. (2005). Hegemony and the politics of culture and identity in Thailand. Critical Asian Studies, 37(4), 523–551. doi: 10.1080/114672710500348414

- Dimaggio, P., Hargittai, E., Neuman, R., & Robinson, J. (2001). Social implications of the internet. Annual Review of Sociology, 27, 307–336. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.307

- Fisher, M. (2013). Thailand has had more coups than any other country. This is why. The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2013/12/03/thailand-has-had-more-coups-than-any-other-country-this-is-why/

- Fuller, T., & Wong, E. (2015). Thailand blames Uighur militants for bombing at Bangkok shrine. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2015/09/16/world/asia/thailand-suspects-uighurs-in-bomb-attack-at-bangkok-shrine.html?_r=3

- Gao, L., & Stanyer, J. (2013). Hunting corrupt officials online: The human flesh search engine and the search for justice in China. Information, Communication & Society, 17(7), 814–829. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2013.836553

- Graham, D. A. (2017). ‘Alternative Facts’: The needless lies of the Trump administration. The Atlantic. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2017/01/the-pointless-needless-lies-of-the-trump-administration/514061/

- Greenwald, G. (2013, March 25). The racism that fuels the ‘war on terror’. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2013/mar/25/racism-war-on-terror-awlaki

- Hargadon, A., & Bechky, B. (2006). When collections of creatives become creative collectives: A field study of problem solving at work. Organization Science, 17(4), 484–500. doi: 10.1287/orsc.1060.0200

- Hongladarom, S. (2000). Negotiating the global and the local: How Thai culture co-opts the internet. First Monday, 5(8). Retrieved from http://firstmonday.org/issues/issue5_8/hongladarom/index.html

- Hsieh, H.-F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687

- Jenkins, H. (2006). Convergence culture: Where old and new media collide. New York, NY: New York University Press.

- Johnson, K., Leger, L. D., & Strauss, G. (2013). FBI releases images of two suspects near Boston bomb sites. USA Today. Retrieved from http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2013/04/18/boston-bombing-marathon-investigation-fbi/2093037/

- Landemore, H. (2017). Democratic reason. Princeton University Press. Retrieved from https://press.princeton.edu/titles/9907.html

- Latour, B. (2005). Reassembling the social: An introduction to actor-network-theory. Clarendon lectures in management studies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Latour, B., & Woolgar, S. (1986). Laboratory life: The construction of scientific facts (2nd ed.). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Law, J. (2009). Actor network theory and material semiotics. In B. S. Turner (Ed.), The new Blackwell companion to social theory, Blackwell companions to sociology (pp. 141–158). Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Lessig, L. (2009). Reforming law. In Remix: Making art and commerce thrive in the hybrid economy (pp. 253–273). New York: Penguin Books.

- Levy, P. (1999). Collective intelligence: Mankind’s emerging world in cyberspace. Cambridge, MA: Basic Books.

- Madrigal, A. (2013). #BostonBombing: The Anatomy of a Misinformation Disaster. Retrieved July 30, 2016, from http://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2013/04/-bostonbombing-the-anatomy-of-a-misinformationdisaster/275155/

- Malone, T., & Klein, M. (2007). Harnessing collective intelligence to address global climate change. Innovations, 2(3), 15–26. doi: 10.1162/itgg.2007.2.3.15

- Middleton, R. (2015). Bangkok bomb: Social media sleuths on overdrive falsely accuse Australian model Sunny Burns. International Business Times. Retrieved from http://www.ibtimes.co.uk/bangkok-bomb-social-media-sleuths-go-overdrive-falsely-accuse-australian-model-sunny-burns-1516236

- Muniz, A., & O’Guinn, T. (2001). Brand community. Journal of Consumer Research, 27(4), 412–432. doi: 10.1086/319618

- Nakajima, S. (2013). Re-imagining civil society in contemporary urban China: Actor-network-theory and Chinese independent film consumption. Qualitative Sociology, 36(4), 383–402. doi: 10.1007/s11133-013-9255-7

- NBC News. (2016). Inside the FBI Boston bombing investigation. NBC News. Retrieved from http://www.nbcnews.com/nightly-news/video/inside-the-fbi-boston-bombing-investigation-836283971756

- NewsAsia. (2015). Online Thai sleuths try to crowdsource bomber’s identity. Channel NewsAsia. Retrieved from http://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/asiapacific/online-thai-sleuths-try/2061194.html

- Nicks, D. (2013). The six most important moments in Reddit history. Time. Retrieved from http://techland.time.com/2013/10/01/the-six-most-important-moments-in-reddit-history/

- Niederer, S., & Dijck, J. van. (2010). Wisdom of the crowd or technicity of content? Wikipedia as a sociotechnical system. New Media & Society, 12(8), 1368–1387. doi: 10.1177/1461444810365297

- Nimmo, R. (2011). Actor-network theory and methodology: Social research in a more-than-human world. Methodological Innovations Online, 6(3), 108–119. doi: 10.4256/mio.2011.010

- Ong, R. (2012). Online vigilante justice Chinese style and privacy in China. Information & Communications Technology Law, 21(2), 127–145. doi: 10.1080/13600834.2012.678653

- Pan, X. (2010). Hunt by the crowd: An exploratory qualitative analysis on cyber surveillance in China. Global Media Journal, 9(16), 1–19.

- Pantumsinchai, P. (2017). Armchair detectives and the social construction of falsehoods: Emergent mob behavior on the internet (PhD dissertation). University of Hawaii at Manoa.

- Phillips, W. (2013). The house that fox built: Anonymous, spectacle, and cycles of amplification. Television New Media, 14(6), 494–509. doi: 10.1177/1527476412452799

- Pinch, T., & Bijker, W. (1993). The social construction of facts and artifacts: Or how the sociology of science and the sociology of technology might benefit each other. In W. Bijker, T. Hughes, & T. Pinch (Eds.) The social construction of technological systems: New directions in the sociology and history of technology (4th ed., pp. 1–51). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Poynting, S., & Mason, V. (2007). The resistible rise of Islamophobia anti-Muslim racism in the UK and Australia before 11 September 2001. Journal of Sociology, 43(1), 61–86. doi: 10.1177/1440783307073935

- Reddit. (2016). Reddit: The front page of the internet. Reddit. Retrieved from https://www.reddit.com/

- Rieder, B. (2013). Studying Facebook via data extraction: The Netvizz application. In Websci ‘13 proceedings of the 5th annual ACM web science conference (pp. 346–355). New York, NY: ACM.

- Ritzer, G., & Jurgenson, N. (2010). Production, consumption, prosumption: The nature of capitalism in the age of the digital ‘prosumer’. Journal of Consumer Culture, 10(1), 13–36. doi: 10.1177/1469540509354673

- Ronson, J. (2016). So you’ve been publicly shamed. MP3 Una edition. Audible Studios on Brilliance Audio.

- Scott, M. (2017, March 24). Fake sleuths: Web gets it wrong on London attacker. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/24/technology/london-terror-attack-suspect-social-media.html

- Shirky, C. (2010). Cognitive surplus: How technology makes consumers into collaborators. New York: Penguin Books.

- Shirky, C. (2011, January 14). Wikipedia – an unplanned miracle. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2011/jan/14/wikipedia-unplanned-miracle-10-years

- Silver, A., & Matthews, L. (2017). The use of Facebook for information seeking, decision support, and self-organization following a significant disaster. Information, Communication & Society, 20(11), 1680–1697. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2016.1253762

- Sismondo, S. (2009). An introduction to science and technology studies (2nd ed). Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Smith, D. (1999). Writing the social: Critique, theory, and investigations. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Stahl, G. (2006). Group cognition: Computer support for building collaborative knowledge. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. Retrieved from https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/group-cognition

- Stelter, B. (2016). Fake news, real violence: ‘Pizzagate’ and the consequences of an Internet echo chamber. CNN Money. Retrieved from http://money.cnn.com/2016/12/05/media/fake-news-real-violence-pizzagate/index.html

- Tao, Y.-H., & Chao, C.-H. (2011). Analysis of human flesh search in the Taiwanese context. In: 2nd international conference on innovations in bio-inspired computing and applications, Shenzhen, China.

- Thananithichot, S. (2011). Understanding Thai nationalism and ethnic identity. Journal of Asian and African Studies, 46(3), 250–263. doi: 10.1177/0021909611399735

- Tribute Wire Reports. (2015). Probe of Bangkok bombing recalls bad reputation of police. The Chicago Tribune. Retrieved from http://www.chicagotribune.com/news/nationworld/ct-bangkok-bombing-probe-20150825-story.html

- Wikipedia. (2017). Wikipedia: About. Wikipedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Wikipedia:About&oldid=771132497

- Wilson, S., Miller, G., & Horwitz, S. (2013). Boston bombing suspect cites U.S. wars as motivation, officials say. The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/boston-bombing-suspect-cites-us-wars-as-motivation-officials-say/2013/04/23/324b9cea-ac29-11e2-b6fd-ba6f5f26d70e_story.html

- Winichakul, T. (2008). Nationalism and the radical intelligentsia in Thailand. Third World Quarterly, 29(3), 575–591. doi: 10.1080/01436590801931520