ABSTRACT

Based on a quantitative content analysis of political actors’ Facebook posts (N = 1915), this study investigates profile-level and post-level drivers of user engagement (comments, likes, and shares) by employing a multilevel approach. For the first time in extant research, we also examine the factors that drive political actors to react to user comments. Findings indicate that the number of followers, the use of an official fan profile, and party vote share were negatively related to political actors’ reactions to user comments. Furthermore, party profiles were least successful in stimulating user engagement. On the post level, we found that reasoning, post length, and references to competitive political actors have the potential to increase different types of user engagement. Negative, but not positive tonality increased user engagement and positive emotional expressions had a stronger effect on user engagement than negative emotions. Furthermore, humorous posts were more likely to be commented, liked, or shared, while mobilization cues had predominantly negative effects on user engagement.

Social network sites (SNS) have become an important new source for political information. This is especially true for the younger cohort. In the 2016 presidential election, SNS were the most important source for young people’s campaign information, and an increasing share of Facebook users retrieve their political information directly from candidates’ Facebook pages (Pew Research, Citation2016). However, political actors’ Facebook accounts provide channels not only for pure information but also for political participation (Knoll, Matthes, & Heiss, Citation2018). For instance, Facebook users can express their opinions in the comments section of political actors’ posts. They can discuss matters with other users and even interact with political actors. Moreover, they can make posts more visible by ‘liking’ and ‘sharing’ them. Such direct engagement has great potential to influence political decision-making, as political actors can derive an opinion climate from user engagement and are confronted with direct feedback of potential voters and opinion leaders (Bene, Citation2017).

From a participatory democracy perspective, political actors’ Facebook posts have a great potential to increase the interaction between political actors and citizens and hence stimulate participation. Literally, everyone can express opinions and the political actors can directly respond to citizens’ input. Past research on political actors on social media, however, suggests that political actors predominantly use Facebook as a tool for one-way communication (e.g., Gerodimos & Justinussen, Citation2015) and the potential for real interaction with citizens is yet to be unfolded (also see Lilleker, Citation2016; Stromer-Galley, Citation2000). In such a context, it is important to know what drives user engagement as well as political actors’ reactions on Facebook. First research evidence indicates that source and content characteristics are important drivers for user engagement on SNS (Knoll et al., Citation2018; also see Bene, Citation2017; Borah, Citation2016; Larsson, Citation2015; Xenos, Macafee, & Pole, Citation2017). Yet, although these studies have significantly contributed to the literature, we identify five important research gaps.

First, all prior studies are related to election campaigns, mostly in the US (e.g., Borah, Citation2016; Gerodimos & Justinussen, Citation2015; Xenos et al., Citation2017). However, the majority of the time people live and act in a non-electoral context, which, in terms of the time and money political candidates spend on social media, differs from the campaign season (Schmuck, Heiss, Matthes, Engesser, & Esser, Citation2017). Second, most of the studies (e.g., Borah, Citation2016; Gerodimos & Justinussen, Citation2015; Larsson, Citation2015) used a limited sample size, covering only a few prominent politicians. In reality, users may also connect to less popular political actors, for example, because they are involved in their communities. Third, differences in profile-level characteristics are still scarcely investigated (Xenos et al., Citation2017). There is reason to believe that the type of political party and the type of Facebook page may play a role in user interaction and thus warrants a more thorough investigation. Fourth, there is no study yet which investigates the factors driving political actors to become engaged in the comments section of their posts (Gerodimos & Justinussen, Citation2015). Finally, none of the existing studies have employed a multilevel modeling approach (Gelman & Hill, Citation2007). For example, Bene (Citation2017) and Xenos et al. (Citation2017) have only controlled for the popularity and the activity of profiles. This, however, can hardly account for the nested structure of the data and inter-profile variability, such as the different characteristics of followers.

To address these important research gaps, we have collected Facebook posts of national political actors in Austria in a non-electoral period of six months. We coded two different levels: the profile level (i.e., the political actor) and the content on the post level. We analyzed these data using multilevel modeling, which allowed us to account for the variability between the different profiles.

Interaction in political actors’ Facebook posts

Political actors’ SNS accounts provide great potential to increase interaction between citizens and political representatives. We define interaction as the presence of responsiveness, i.e., ‘when the receiver takes on the role of the sender and replies in some way to the original message source’ (Stromer-Galley, Citation2000, p. 117). Based on this definition, interaction occurs when users engage with Facebook posts, such as by commenting, liking, or sharing a post. The degree of interaction, however, increases if the political actor in turn responds to users in the commentary field of the post. Only if political actors and users engage in dynamic message sending and responding, they ‘share the burden of communication equally, subverting hierarchical, linear structures of communication’ (Stromer-Galley, Citation2000, p. 117). Such interactive processes may involve and increase political participation because users can influence political decisions through direct communication with the political actors in power (Knoll et al., Citation2018).

However, the success of new online forms of interaction is determined by whether citizens make use of them and the responsiveness of the political system. These two factors can be measured in political actors’ Facebook posts. First, user engagement can be measured as ‘observable activities directly connected to specific candidate communications’ including comments, likesFootnote1, and shares (Xenos et al., Citation2017, p. 5). Users may differ in terms of how they engage in posts, as commenting was found to be primarily related to social interaction motivations, liking to presentational motivations, and sharing to information-sharing motivations (Macafee, Citation2013). Moreover, not all of these three types of user engagement may require the same cognitive effort. For example, clicking on the like button may require comparably little effort. However, sharing a post and hence suggesting your network that something is worth reading or engaging with may require more in-depth elaboration. The same is true for commenting, which involves the risk that other users respond to and evaluate one’s comment. However, it should be noted that comments may vary in terms of content (Stromer-Galley, Citation2003) and that the quality and valence of a comment may determine the democratic potential of user engagement as well as the willingness of a political actor to react. Measuring the content of single user comments, however, was beyond the scope of this study. Secondly, political actors’ reactions (to user engagement) can be measured as whether the actor replies in the comments section of a post. Such reactions indicate a two-way style of communication, which is an essential element of public deliberation.

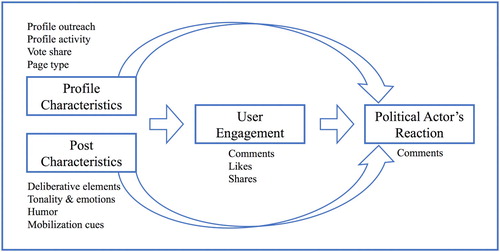

Overall, research on the predictors of user reactions to political actors’ SNS posts is scarce, and research on the reactions of political actors in their posts is yet inexistent. However, some factors have been identified which drive user engagement, which we will outline in the following section. In doing so, we consider post-level (i.e., content) and profile-level (i.e., actor specific) characteristics that drive both user engagement and political actors’ reactions (Knoll et al., Citation2018). A conceptual model of the proposed relationships is depicted in .

Effects of profile characteristics

First, we are interested in the effects of different profile-level characteristics. There is reason to believe that certain actors use SNS more robustly than others. For instance, Xenos et al. (Citation2017) found that posts from candidates with incumbency status or from major party members were more likely to receive comments and likes, indicating support for the normalization hypothesis, i.e., that established political parties are more successful in stimulating engagement online (Margolis & Resnick, Citation2000). The study, however, was conducted in an electoral context, in which larger parties may have been especially active in using their resources to advertise political posts. In contrast to this finding, theories of equalization suggest that smaller parties are more likely to utilize SNS channels to compensate for financial disadvantages offline (Rauchfleisch & Metag, Citation2016). To investigate these two competing assumptions, we assigned each actor (i.e., candidate or party page) in our sample with the vote share of the political party the actor belonged to. The variable thus represents the size of each party in terms of its vote share in the last election (2013). Due to contradictive findings and a general lack of research in this field, we ask:

RQ1: How is party vote share related to user engagement and political actors’ reactions to user comments?

RQ2: How are the types of Facebook pages used (candidate fan page, candidate private page, party page) related to user engagement and political actors’ reactions?

Effects of post characteristics

In this section, we develop hypotheses on how individual content characteristics affect user engagement. However, we do not formulate hypotheses on potential effects on political actors’ reactions, because we yet lack empirical evidence in this field.

Deliberative elements

On the post level, we first investigate how deliberative elements in a post drive user engagement. One of the most important components of deliberation is reasoning (Habermas, Citation1989). We define reasoning as whether claims in a post are supported by empirical evidence, such as statistical data or personal experience. There is some basis to believe that such reasoning may ‘fuel and resolve disputes, thus stimulating the deliberative process’ (Steenbergen, Bächtiger, Spörndli, & Steiner, Citation2003, p. 25). This is because stronger arguments evoke favorable feelings toward the message and have a higher persuasive power, at least among individuals who are involved with the issue (Petty, Cacioppo, & Goldman, Citation1981). This may hence be also true for political actors’ Facebook followers, as first evidence indicates that such followers may have stronger political predispositions compared to non-followers (Heiss & Matthes, Citation2017). Thus, if political actors use reasoning, followers may be more likely to engage with the message, such as by liking, commenting, and sharing the message (Gerodimos & Justinussen, Citation2015). Following this logic, also longer posts may increase user engagement (Bene, Citation2017). Longer posts are more likely to contain sophisticated information on the basis of which users can develop stronger attitudes and act upon them.

Furthermore, references to other political competitors may stimulate user interactions. We define references to political competitors as mentioning the names of competitive political parties or candidates affiliated with such parties. In doing so, political actors may refer to competing political standpoints and present their own views. Past research has found that exposure to different opinions can increase opinion polarization (Lee, Choi, Kim, & Kim, Citation2014) and deliberative participation (McLeod et al., Citation1999). References to external actors may have a similar function, as they provide followers with different views. As political actors use Facebook for marketing purposes, however, they may also highlight the superiority of their own policy preferences and mobilize similar views (Lilleker, Citation2015). However, references to political competitors may be confounded with negativity (Stieglitz & Dang-Xuan, Citation2013). If political actors refer to their opponents, they may do this in an overall negative manner, especially during election campaigns (Xenos et al., Citation2017). Whether negativity also moderates the effect of external political references in a non-electoral context has not been addressed thus far. From this foundation, we pose a research question on a potential interaction effect of references to competitive actors and negativity. Finally, we formulate a research question with regard to the relation between references to own party actors and user activity, which has not been investigated before.

H1: Reasoning (a) lengthier posts (b) and references to competitive actors (c) increase user engagement

RQ3: Is the effect of references to competitive actors moderated by negativity?

RQ4: How do references to own party actors affect user engagement?

Tonality and emotions

Although closely connected, tonality and emotionality describe different message characteristics. Tonality refers to positive (e.g., political success, achievement) or negative content elements (e.g., political failure, crisis), while emotionality describes how a message is presented, more specifically, whether a political candidate explicitly expresses positive or negative emotions (De Vreese, Esser, & Hopmann, Citation2016). For example, a candidate may state ‘we see that our policies were successful and significantly increased employment’ (positive tone). Emotional posts, by contrast, include emotional keywords or emotionally loaded language (e.g., ‘I’m happy/angry/sad’, ‘This is the worst law the world has ever seen!!’). Research in negativity bias provides strong evidence that individuals pay more attention and show stronger reactions to negative than to positive information (e.g., Baumeister, Bratslavsky, Finkenauer, & Vohs, Citation2001; Soroka, Citation2012). Theoretically, negative tonality and emotions may increase user engagement because negativity may elicit negative feelings, including anger and fear. Such feelings may then increase users’ involvement. For example, anger is related to feelings of political discontent and increases the likelihood to engage with attitude-consistent information (Valentino, Brader, Groenendyk, Gregorowicz, & Hutchings, Citation2011). Furthermore, affective intelligence theory assumes that anxiety can mobilize through elaboration. For example, individuals who are anxious may engage in in-depth processing of a political post and hence share or comment it (MacKuen, Wolak, Keele, & Marcus, Citation2010). In line with this reasoning, scholars observed that more critical information (Larsson, Citation2015) and negative tonality (Bene, Citation2017) increase user engagement in politicians’ Facebook posts. There is less evidence that mere positive tonality drives user engagement (Bene, Citation2017). One reason might be that mere positive tonality may be associated with a persuasive intention and may trigger reactance (Koch & Peter, Citation2017). However, the expression of positive emotions may increase the credibility of the message and induce stronger persuasive effects (Brader, Citation2005). For example, exposure to positive emotional expressions may evoke positive feelings in users and make them more open to engage with the positive information in the message (Baumgartner & Wirth, Citation2012). In line with this, Berger and Milkman (Citation2012) found that emotionally arousing news stories are more likely to be shared online and that positive emotions are even more viral than negative emotions. We extend this research and test the effect of general tonality against the effect of emotional cues in a Facebook post. Based on the previous research, we assume that only negative, not positive, tone affects user engagement (Bene, Citation2017). Additionally, we expect both positive and negative emotional expressions to drive user engagement.

H2: Negative tone, but not positive tone, increases user engagement.

H3: Negative (a) and positive (b) emotionality increases user engagement.

Humor

Drawing on political humor research, we assume that humor increases user engagement. Humor is used as a tool for entertainment and may be an important source of individuals’ need gratification. From a theoretical view, humor can increase attention to messages (Eisend, Citation2009; Matthes, Citation2013). This may be especially important in the highly competitive social media environment, in which political posts are embedded in an entertaining context. In line with this reasoning, seeking entertainment has been identified as a core motivation to visit candidate profiles on SNS (Ancu & Cozma, Citation2009). Borah (Citation2016) observed that the use of humor stimulated shares of political Facebook posts; Bene (Citation2017) found no such relationship, which might be related to a rather narrow definition of humor of the latter. However, based on the theoretical view described above, we assume that humoristic elements increase the involvement and, hence, the responsiveness of users.

H4: Humoristic elements increase user engagement.

Mobilization

Calls for mobilizations are defined as posts which provide information where or how citizens can take political action, including links to petitions or calls to participate in a political protest. Heiss and Matthes (Citation2016) have shown that exposure to such engagement calls can increase collective efficacy in users. Motivated by information sharing, they may thus share participation calls so that other people in their network may also become engaged (Macafee, Citation2013). There is less evidence to assume a positive effect on likes and comments. In fact, past research has shown that such calls may have no or even negative effects on likes and comments (Bene, Citation2017; Xenos et al., Citation2017).

RQ5: How does offline and online mobilization affect user engagement?

RQ6: How do post-level variables affect political actors’ reactions in the comments section?

Method

We implemented a quantitative content analysis, covering political Facebook posts of the most important political actors in Austria. The Austrian electoral system is based on proportional representation. Single members of the national parliament (Nationalrat) are elected through party lists and the leader of the winning party is assigned as chancellor and head of the government. At the time of the analysis, six political parties were represented in the parliament, which had exceeded the 4% election threshold in the 2013 national election. These six parties include two smaller parties, The New Austria (5% vote share) and the Team Stronach (5.4%), both founded in 2012; the two traditional large parties, the Social Democrats (26.8%) and the conservative People’s Party (24%), which formed the coalition government at the time of the analysis; and the two traditional opposition parties, the Austrian Freedom Party (20.5%) and the Green Party (12.5%). The political actors we investigate in this study include all 183 members of the Nationalrat, all members of the government (ministers and state secretaries), and political party organizations (main and youth organizations). We searched for the full names of all of these political actors on Facebook and found a total of 95 profiles. Some 34% of all members of parliament used Facebook for public communication, as did 44% of all ministers and state secretaries and 100% of the investigated party organizations. As we had to exclude five profiles due to missing information (e.g., number of followers) and three profiles due to restrictive user rights – i.e., profiles which did not allow users to comment posts – our final sample consisted of 87 profiles and 1915 wall posts. In order to make the analysis less dependent on single events, we chose a time frame of six months in a non-electoral period (5 January 2015 to 19 July 2015). We created four artificial weeks over this time frame and coded each individual post which occurred in these four artificial weeks.

Three independent coders conducted the data collection. Two coders ran a series of reliability tests using different subsamples of n = 30 posts each. All variables yielded sufficient Krippendorff’s alpha scores (all above .70). Later in the process, a third independent coder joined. As reliability was already high, all three coders repeated the test with n = 20 posts for each variable. Final reliability scores are reported. For most manifest variables such as profile type and publicity, user reactions, shared content, pictures and videos, references to internal and external actors, and online mobilization alpha values were 1. Offline mobilization reached a value of .84. More latent variables yielded sufficient alpha values (reasoning = .82; tonality = .79; emotions = .75; issue = .97; humor = .68).

Generally, we coded on two different levels. First, we coded variables on the level of the political actor, i.e., the Facebook profile. The variable party vote share represents the vote share (in percent) of each of the six political parties in the national election 2013. Thus, the variable can take six values and each actor is assigned with the corresponding value for the party the actor represents (e.g., all Social Democrat’s candidates or party profiles are assigned with the value 26.8%). The variable profile type is a categorical variable which captures whether the profile is a private account used for campaigning, an official fan page of a politician, or a party page (political party or respective youth organization). Private accounts are characterized by an add friend button instead of a like button. We only coded private accounts which were publically accessible or accepted a friend request we sent from a fake profile. We created dummy variables for political party and profile type. Furthermore, assessed each actor’s profile outreach (M = 18176.32, SD = 42270.11), i.e., the total number of followers, likes, and/or friends, and profile activity (M = 37.68, SD = 21.97), i.e., the number of posts posted in the time frame under study.

Second, we coded variables on the level of the individual post. All variables, except post length, are dummy coded. The variable reasoning measured whether a post contained an assertion which was supported by either facts (e.g., statistical data) or personal experience (e.g., providing examples) (see Steenbergen et al., Citation2003). We measured whether a post included references to the own party (internal reference) or to other (competitive) political party actors (external references). Furthermore, we coded post length (M = 34.91, SD = 59.10) by counting the number of words in the post text. We coded negative tonality when the post contained information on, for example, political failure, crises, frustration, disappointment, or negative expectations. Positive tonality was coded when the post contained issues related to success, achievement, progress, or optimism. Furthermore, we used certain keywords to identify negative (e.g., anger, sadness, or fear) and positive emotions (e.g., hope, happiness, or love) in a post. Moreover, the use of emotionally loaded pictures and language (e.g., superlatives and dramatization) were also coded as either positive or negative emotions (for a similar approach see De Vreese et al., Citation2016). Humor was coded when sarcasm, irony, silliness, or linguistic jokes were present (Sternthal & Craig, Citation1973). Finally, we coded offline and online mobilization when the posts included information on how or where citizens could take political actions, such as links to online petitions or calls for attending a political (offline) event.

Control variables: Domestic political issues contain issues related to, for example, economics, the environment, social policy, and immigration, or federal reforms. Foreign political issues include issues related to Austrian diplomacy but also to international conflicts and crises, including issues related to terrorism, refugees, and war. Party politics & elections contain posts about party manifestos, party conventions, party organization, or campaign posts (Schmuck et al., Citation2017). Even though we observed a non-electoral time period on the national level, there may still be posts related to regional elections. The fourth aspect represents private issues, including posts which relate to, for example, family, spare time, or hobbies. Finally, we assessed whether the posts included videos, pictures, shared content, or media content. Shared content is content shared from third sources; media content is coded when news media content was embedded in the posts, either through links or through screenshots of the news content. provides information on how frequently the individual variables occurred in our sample. There were no indications of multicollinearity.

Table 1. Descriptive overview of the number of posts related to the investigated profile and content characteristics in our sample (N = 1915).

Results

To analyze the predictors of the number of comments, we ran multilevel negative binomial regressions (Hilbe, Citation2011). We chose this approach because the individual posts we analyzed were nested in the profiles of the political actors. Hence, to account for between profile differences, we allow intercepts to vary randomly across the different profiles (Gelman & Hill, Citation2007). We further employed negative binomial regression, as the observed variance in our dependent variable is considerably larger than the mean for comments (M = 13.54, SD = 46.64), likes (M = 227.30, SD = 2233.09), and shares (M = 65.80, SD = 1510.29). We used the Automatic Differentiation Model Builder (ADMB) in R (see Fournier et al., Citation2012) to implement our analysis (see ). Finally, we ran hierarchical binary logistic regression to analyze whether political actors reacted to user comments in the comments section of their posts (see ). Political actors reacted in 14.46% of all analyzed posts.

Table 2. Negative binomial regression with random intercepts predicting user engagement.

Table 3. Logistic regression with random intercepts predicting political actors’ reaction.

User engagement

Results for user engagement are shown in . As expected, findings for the profile-level variables show that profile outreach is a highly significant predictor of comments, likes, and shares. Profile activity, however, did not affect user engagement. Vote share did not affect user engagement (RQ1). However, we did find significant results for the different types of profiles used (RQ2). Politicians using fan pages were less successful in generating user comments (b = −0.51, p < .05) as compared to politicians using private pages. However, posts from fan pages were more likely to be shared as compared to posts from private pages (b = 0.95, p < .01). Organizational Facebook pages were less successful in stimulating commentary activities (b = −1.26, p < .001).

Turning to the post variables, results show, in line with H1a, that reasoning increased the number of comments (b = 0.69, p < .01), likes (b = 0.65, p < .001), and shares (b = 2.28, p < .001). H1b is partly supported, as post length increased comments (b = 0.10, p < .001) and likes (b = 0.05, p < .01), but not shares. With regard to H1c, our findings show that references to external party actors had a positive effect on comments (b = 0.22, p < .01), but a negative effect on likes (b = −0.12, p < .05) and no effect on shares. Additional moderation analysis revealed that the effects of references to competitive actors were not moderated by negative tone or emotions (RQ3). References to the political actors’ own party (RQ4) had a significant negative effect on the number of comments (b = −0.35, p < .001), likes (b = −0.15, p < .01), and shares (b = −0.51, p < .001).

Our findings partly support H2, as we found that negative tonality increased the number of comments (b = 0.20, p < .05) and shares (b = 0.39 p < .01), but not likes. Positive tone had no positive effects on user engagement. H3a is also only partly supported: negative emotions only had a positive effect at the marginal level of significance on comments, significantly increased likes (b = 0.20, p < .05) and had no effect on shares. We find full support for H3b, as positive emotions increased comments (b = 0.53, p < .001), likes (b = 0.35, p < .001), and shares (b = 0.51, p < .01).

Furthermore, in line with H4, posts which contained humoristic elements were more likely to be commented (b = 0.61, p < .001), liked (b = 0.37, p < .001), and shared (b = 0.83, p < .001). Mobilizing efforts (RQ 5) related to offline activities were negatively related to comments (b = −0.59, p < .001) and likes (b = −0.72, p < .001) and shares (b = −0.72, p < .01). Mobilization efforts related to online activities were also negatively related to commenting (b = −0.50, p < .05) and liking (b = −0.53, p < .01), but positively related to sharing on the marginal level of significance.

Political actors’ reactions

Finally, summarizes the results related to political actors’ reactions in the commentary field of individual posts (RQ1 and RQ6). On the profile level, the findings show that profile outreach had a close to a significant positive effect on commenting in the first model. This effect turns to be significantly negative once controlling for the number of comments in the second model (b = −0.52, p < .01). These results indicate that the weak positive effect in the parsimonious model may be mediated by the number of comments. Once controlling for the number of comments, higher profile outreach has a strong negative effect on political actors’ reactions. Furthermore, our models indicate that vote share had a negative effect which became stronger when controlling for the number of comments (b = −0.06, p < .01). Moreover, politicians using fan profiles were less likely to react to user comments compared to politicians using private profiles (b = −1.26, p < .01). Post-related factors rarely explained political actors’ reactions. However, we still found a negative effect of negative tonality (b = −0.46, p < .05), and a positive effect of expressing negative emotions (b = 0.83, p < .01).

Additional findings

Additional findings in indicate that users were more likely to engage with party politics (except shares) and foreign policy issues as compared to domestic policy issues. Private issues were more likely to be liked and commented, but less likely to be shared. Furthermore, we found that embedded photos had negative and videos no effects on user engagement. However, media content embedded in the post significantly boosted commenting and sharing, but negatively affected likes. Finally, shared content was less likely to receive user reactions. Furthermore, when controlling for the number of comments, political actors were less likely to react to comments in posts dealing with foreign policy issues.

Discussion

On the profile level, the findings of this study indicate that the potential of real interaction between political actors and citizens may remain limited. The number of followers, the use of an official fan profile, and also party vote share negatively affected the willingness of political actors to react to user comments. One reason might be that the more ‘official’ the communication becomes, the more risk is involved (see Stromer-Galley, Citation2000). For example, such activities may also be noticed by the media and might be disseminated through multiple networks. This is also supported by our finding that profile outreach and the use of an official fan profile were positively related to the number of post shares. Increasing popularity may hence drive a one-way style of communication that dampens interactivity with users – which should be actually a key goal of SNS strategies.

The negative effect of party vote share (i.e., the size of the party an actor belongs to) on political actors’ reactions may also support assumptions of equalization, such as that smaller parties are more willing to take advantage of the interactive potential of social media, even though they may still face disadvantages in social media campaigning (e.g., advertising) in electoral times (Xenos et al., Citation2017). It may also indicate that larger, established parties with strong offline institutions still rely on their established organizational structures, which used to be successful in the past. Increasing institutional dealignment and the relocation of political engagement to the online world, however, may also increase the need for larger parties to adjust their responsiveness to voters’ online engagement. Furthermore, our finding that private pages were most and organizational (party) profiles least successful in stimulating user comments, along with the positive effect of private issues on comments, point to the importance of personalization on social media (Kruikemeier et al., Citation2013).

On the post level, we found that reasoning, post length, references to political competitors, negative tonality, positive emotions, and humor drove different types of user engagement. Followers on Facebook may thus still engage with longer and more elaborated political content. In fact, one can assume that followers of political actors may be comparably politically involved (Heiss & Matthes, Citation2017), and hence may be more likely to evaluate and process political arguments. In doing so, they may develop stronger opinions and hence increase their user engagement. However, it should be noted that the presence of reasoning was very limited and that the potential to use more sophisticated types of communication is yet to be unfolded (see ). Furthermore, we found that references to political competitors positively affected commenting, but negatively affected likes. Such references may contain contrasting issue positions, which may not be ‘liked’ by the followers of the candidate, but which may stimulate a ‘rallying’ effect, in which followers may express support for ‘their’ candidate’s positions. Interestingly, we did not find support for an interaction effect of reference to competitive actors times negativity, which may represent a political attack (Stieglitz & Dang-Xuan, Citation2013; Xenos et al., Citation2017). This indicates that it might be indeed issue polarization which stimulates commentary activity. By contrast, we found that references to own party actors decreased all measures of user engagement. Such posts may be perceived as political marketing, providing little incentive for users to get engaged.

In terms of tonality, we found that the effect of negative tone increased comments and shares, whereas the expression of negative emotions increased only likes. This may indicate that it is not so much about the negative feelings which are expressed in a candidate’s post, but the negative feelings which are elicited through negative content. For example, mere negative information about the economy might be already enough to stimulate anger or anxiety in a user and hence increase engagement (MacKuen et al., Citation2010; Valentino et al., Citation2011). The opposite was true for positivity. We found that mere positive tonality did not increase user engagement, but the expression of emotions did (Berger & Milkman, Citation2012). This might be related to the nature of social media, which is heavily used for entertainment purposes (Ancu & Cozma, Citation2009). Positive emotions may serve well in this context, as such posts pose little threat to the positive mood of users (Baumgartner & Wirth, Citation2012). A similar logic may be also applied to our finding on humor. The use of humor may elicit positive feelings and attention to political content on Facebook and may hence increase the willingness to engage (Eisend, Citation2009; Hoffman & Young, Citation2011).

Finally, our findings indicate that offline and online mobilization negatively affected user engagement. Most mobilization cues may only be used strategically to stimulate party support, rather than to provide meaningful channels for participation (Heiss & Matthes, Citation2016). This may be less true for online mobilization cues, which were more frequently shared. However, such posts were rare in our sample (see ). Hence, our data also indicate that this potential is yet to be unleashed.

Conclusions

This study has shown that the interactive potential of political actors’ Facebook accounts may be limited, as the more publicity and public attention a profile receives, the less political actors are willing to react to user comments. However, specifically younger and smaller parties may still actively engage in interaction with users and may hence stimulate initial support among voters. Despite the limited willingness of more popular political actors to react to user comments, their Facebook posts may still provide an important space for user engagement. Most importantly, this study has shown that not only mere negativity, but also reasoning, references to competitive party actors, post length, positive emotions, and humor can have positive effects on different types of user engagement. Even though we found overly negative effects of mobilization cues on user engagement, the provision of really meaningful channels of participation may still have a positive potential, as the close to a significant positive effect of online engagement cues indicated. Speaking for the Austrian case, much of this positive potential, however, is yet to be unfolded.

Some limitations should be noted. First of all, our sample represents the Austrian context in a non-electoral period. The Austrian case might differ from other countries, such as the United States, for example, in terms of the number of people politicians can reach. Moreover, compared to majority electoral systems, the proportional system in Austria may generally provide less incentives for single political actors to engage in interactions with users. This research should thus be extended to different countries. Second, there might be other factors driving user engagement which we did not observe (see Knoll et al., Citation2018). For example, some posts might have been pushed by advertising, which we were unable to trace back. Furthermore, as in the previous research, we could not examine the content of comments. However, user comments reacting to an emotionalized negative post may be more likely to involve incivility and less deliberate political content. Future studies should thus specifically investigate how the content of user comments may determine whether a political actor reacts to such comments and assess the deliberative potential of user comments in politicians’ posts. We were also not able to trace back who shared the posts with what kind of additional information. Finally, certain technological innovations might change the context of user engagement. For example, Facebook has recently introduced multiple variations of the like button, such that users can also express anger, love, or surprise. This might affect the number and meaning of such reactions as compared to the simple like button.

Despite these limitations, this study is one of the few which contributes to our knowledge of interactivity in political actors’ Facebook posts. Identifying the type of content that is most likely to generate both users’ and politicians’ reactions is crucial for enhancing our understanding of the changing nature of political communication. This, however, is a yet underexplored area of research, one which has great potential to further our understanding of the complex relationship between SNS use and political participation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Raffael Heiss is a PhD candidate at the Department of Communication, University of Vienna, Austria. His research interests include digital communication, media effects, and political participation [email: [email protected]].

Desirée Schmuck is a PhD candidate at the Department of Communication, University of Vienna, Austria. Her research interests include right-wing populism, political communication, and sustainability communication effects [email: [email protected]].

Jörg Matthes is Full Professor of Advertising Research at the Department of Communication, University of Vienna, Austria. His research interests include advertising effects, public opinion formation, and methods [email: [email protected]].

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. It should be noted that at the time of our analyses, Facebook only included the classical thumb up like bottom and did not yet include variations, such as emotional reactions (angry, sad, love, etc.).

References

- Ancu, M., & Cozma, R. (2009). Myspace politics: Uses and gratifications of befriending candidates. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 53(4), 567–583. doi: 10.1080/08838150903333064

- Baumeister, R. F., Bratslavsky, E., Finkenauer, C., & Vohs, K. D. (2001). Bad is stronger than good. Review of General Psychology, 5(4), 323–370. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.5.4.323

- Baumgartner, S. E., & Wirth, W. (2012). Affective priming during the processing of news articles. Media Psychology, 15(1), 1–18. doi: 10.1080/15213269.2011.648535

- Bene, M. (2017). Go viral on the Facebook! Interactions between candidates and followers on Facebook during the Hungarian general election campaign of 2014. Information, Communication & Society, 20(4), 513–529. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2016.1198411

- Berger, J., & Milkman, K. L. (2012). What makes online content viral? Journal of Marketing Research, 49(2), 192–205. doi: 10.1509/jmr.10.0353

- Borah, P. (2016). Political Facebook use: Campaign strategies used in 2008 and 2012 presidential elections. Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 13(4), 326–338. doi: 10.1080/19331681.2016.1163519

- Brader, T. (2005). Striking a responsive chord: How political ads motivate and persuade voters by appealing to emotions. American Journal of Political Science, 49(2), 388–405. doi: 10.1111/j.0092-5853.2005.00130.x

- De Vreese, C. H., Esser, F., & Hopmann, D. N. (2016). Comparing political journalism. London: Routledge.

- Eisend, M. (2009). A meta-analysis of humor in advertising. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 37(2), 191–203. doi: 10.1007/s11747-008-0096-y

- Fournier, D. A., Skaug, H. J., Ancheta, J., Ianelli, J., Magnusson, A., Maunder, M. N., … Sibert, J. (2012). AD model builder: Using automatic differentiation for statistical inference of highly parameterized complex nonlinear models. Optimization Methods and Software, 27(2), 233–249. doi: 10.1080/10556788.2011.597854

- Gelman, A., & Hill, J. (2007). Data analysis using regression and multilevel/hierarchical models. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Gerodimos, R., & Justinussen, J. (2015). Obama’s 2012 Facebook campaign: Political communication in the age of the like button. Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 12(2), 113–132. doi: 10.1080/19331681.2014.982266

- Habermas, J. (1989). The structural transformation of the public sphere: An inquiry into a category of bourgeois society. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Heiss, R., & Matthes, J. (2016). Mobilizing for some: The effects of politicians’ participatory Facebook posts on young people’s political efficacy. Journal of Media Psychology, 28(3), 123–135. doi: 10.1027/1864-1105/a000199

- Heiss, R., & Matthes, J. (2017). Who ‘likes’ populists? Characteristics of adolescents following right-wing populist actors on Facebook. Information, Communication & Society, 20(9), 1408–1424. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2017.1328524

- Hilbe, J. M. (2011). Negative binomial regression. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hoffman, L. H., & Young, D. G. (2011). Satire, punch lines, and the nightly news: Untangling media effects on political participation. Communication Research Reports, 28(2), 159–168. doi: 10.1080/08824096.2011.565278

- Knoll, J., Matthes, J., & Heiss, R. (2018). The social media political participation model: A goal systems theory perspective. Convergence, Advance online publication, 1–22. doi: 10.1177/1354856517750366

- Koch, T., & Peter, C. (2017). Effects of equivalence framing on the perceived truth of political messages and the trustworthiness of politicians. Public Opinion Quarterly, 81(4), 847–865. doi: 10.1093/poq/nfx019

- Kruikemeier, S., Noort, G., Vliegenthart, R., & Vreese, C. H. (2013). Getting closer: The effects of personalized and interactive online political communication. European Journal of Communication, 28(1), 53–66. doi: 10.1177/0267323112464837

- Larsson, A. O. (2015). Pandering, protesting, engaging: Norwegian party leaders on Facebook during the 2013 ‘Short campaign’. Information, Communication & Society, 18(4), 459–473. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2014.967269

- Lee, J. K., Choi, J., Kim, C., & Kim, Y. (2014). SNS, network heterogeneity, and opinion polarization. Journal of Communication, 64(4), 702–722. doi: 10.1111/jcom.12077

- Lilleker, D. G. (2015). Interactivity and branding: Public political communication as a marketing tool. Journal of Political Marketing, 14(1–2), 111–128. doi: 10.1080/15377857.2014.990841

- Lilleker, D. G. (2016). Comparing online campaigning: The evolution of interactive campaigning from Royal to Obama to Hollande. French Politics, 14(2), 234–253. doi: 10.1057/fp.2016.5

- Macafee, T. (2013). Some of these things are not like the others: Examining motivations and political predispositions among political Facebook activity. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(6), 2766–2775. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2013.07.019

- MacKuen, M., Wolak, J., Keele, L., & Marcus, G. E. (2010). Civic engagements: Resolute partisanship or reflective deliberation. American Journal of Political Science, 54(2), 440–458. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5907.2010.00440.x

- Margolis, M., & Resnick, D. (2000). Politics as usual: The cyberspace ‘revolution’. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Matthes, J. (2013). Elaboration or distraction? Knowledge acquisition from thematically related and unrelated humor in political speeches. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 25(3), 291–302. doi: 10.1093/ijpor/edt005

- McLeod, J. M., Scheufele, D. A., Moy, P., Horowitz, E. M., Holbert, R. L., Zhang, W., & Zubric, J. (1999). Understanding deliberation the effects of discussion networks on participation in a public forum. Communication Research, 26(6), 743–774. doi: 10.1177/009365099026006005

- Petty, R. E., Cacioppo, J. T., & Goldman, R. (1981). Personal involvement as a determinant of argument-based persuasion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 41(5), 847–855. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.41.5.847

- Pew Research Center. (2016, February 4). The 2016 presidential campaign: A news event that’s hard to miss. Retrieved from http://www.journalism.org/files/2016/02/PJ_2016.02.04_election-news_FINAL.pdf

- Rauchfleisch, A., & Metag, J. (2016). The special case of Switzerland: Swiss politicians on Twitter. New Media & Society, 18(10), 2413–2431. doi: 10.1177/1461444815586982

- Schmuck, D., Heiss, R., Matthes, J., Engesser, S., & Esser, F. (2017). Antecedents of strategic game framing in political news coverage. Journalism, 18(8), 937–955. doi: 10.1177/1464884916648098

- Soroka, S. N. (2012). The gatekeeping function: Distributions of information in media and the real world. The Journal of Politics, 74(2), 514–528. doi: 10.1017/S002238161100171X

- Steenbergen, M. R., Bächtiger, A., Spörndli, M., & Steiner, J. (2003). Measuring political deliberation: A discourse quality index. Comparative European Politics, 1, 21–48. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.cep.6110002

- Sternthal, B., & Craig, C. S. (1973). Humor in advertising. The Journal of Marketing, 37(4), 12–18. doi:10.2307/1250353 doi: 10.1177/002224297303700403

- Stieglitz, S., & Dang-Xuan, L. (2013). Emotions and information diffusion in SNS-sentiment of microblogs and sharing behavior. Journal of Management Information Systems, 29(4), 217–248. doi: 10.2753/MIS0742-1222290408

- Stromer-Galley, J. (2000). Online interaction and why candidates avoid it. Journal of Communication, 50(4), 111–132. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2000.tb02865.x

- Stromer-Galley, J. (2003). Diversity of political conversation on the Internet: Users’ perspectives. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 8(3), doi: 10.1111/j.1083-6101.2003.tb00215.x

- Valentino, N. A., Brader, T., Groenendyk, E. W., Gregorowicz, K., & Hutchings, V. L. (2011). Election night’s alright for fighting: The role of emotions in political participation. The Journal of Politics, 73(1), 156–170. doi: 10.1017/S0022381610000939

- Xenos, M. A., Macafee, T., & Pole, A. (2017). Understanding variations in user response to social media campaigns: A study of Facebook posts in the 2010 US elections. New Media & Society, 19(6), 826–842. doi:10.1177/1461444815616617