ABSTRACT

The concept of witnessing has been used to explore the construction of evidence and experience in settings of law, religion, atrocity, media, history and science. Recent research has examined how digital technologies may multiply the involvement of remote, non-present and unanticipated actors in the witnessing of events. This paper examines what digital data practices at Amnesty International’s Decoders initiative can add to the understanding of witnessing. It introduces the notion of ‘data witnessing’ with reference to four projects on (i) witnessing historical abuses with structured data from digitised documents; (ii) witnessing the destruction of villages with satellite imagery and machine learning; (iii) witnessing environmental injustice with company reports and photographs; and (iv) witnessing online abuse through the classification of Twitter data. These projects illustrate the configuration of experimental apparatuses for witnessing injustices with data. In contrast to accounts which emphasise the presence of an individual human witness at the scene, Amnesty’s data practices are conspicuously collective and distributed, rendering the systemic scale of injustices at a distance, across space and time. Such practices may contribute to research on both (new) media witnessing and data politics, suggesting ways in which care, concern and solidarity may be constructed, structured, extended and delimited by means of digital data.

Introduction

Bearing witness is said to be at the heart of Amnesty International’s culture, evident in its combination of volunteer’s networks and documenting abuses (Hopgood, Citation2006, p. 14). This ‘foundational practice’ is said to embody a ‘secular religiosity’ combining witnessing with symbols such as the candle encased in barbed wire and principles of non-violence, suggesting affinities with the outlook of religious groups such as the Quakers (Hopgood, Citation2006, p. 8, 21).

Amnesty’s earliest activities in the 1960s involved compiling information about political prisoners and mobilising volunteers to advocate for their release, including through letters, petitions, candle-lit vigils, supporting their families and the ‘adoption’ of prisoners (Buchanan, Citation2002; Power, Citation1981). In 1973 Amnesty introduced ‘Urgent Actions’ to their repertoire of activities. These were transnational campaigns against abuses often involving mass letter, fax and email writing to parties considered responsible (such as authorities detaining prisoners), an approach which has been described as ‘the tactic of immediate inundation’ (Wong, Citation2012).

This article examines how Amnesty’s practices of documenting and responding to abuses have been extended, modified and redistributed by means of data and digital technologies, focusing on its Decoders initiative (decoders.amnesty.org). Founded in 2016, Amnesty Decoders describes itself as ‘an innovative platform for volunteers around the world to use their computers or phones to help our researchers sift through pictures, information and documents’ (Citation2018). Initially based in Amnesty’s campaigns team and collaborating closely with research teams, the initiative bridges across two central tenets of the organisation’s mission: documentation and volunteer-driven mobilisation.

I propose the concept of ‘data witnessing’ to characterise how data is involved in attending to situations of injustice in Decoders projects, as a conspicuously collective, distributed accomplishment. Unlike accounts which emphasise a singular witness present at the scene, the work of Amnesty Decoders involves a choreography of human and non-human actors to attend to the systemic scale of injustices at a distance, across space and time. These projects may be regarded as experimental apparatuses for witnessing situations of injustice with data, telling us something about emerging practices of (new) media witnessing as well as emerging dynamics of data politics and data activism.

Varieties of witnessing

Data witnessing can be positioned in relation to previous literatures on witnessing. The Holocaust is said to precipitate a ‘crisis of witnessing’ due to a dearth of witnesses and the ‘impossibility of telling’ for survivors (Felman & Laub, Citation1992), giving rise to practices of ‘postmemory’ (Hirsch, Citation2008) amongst those who were affected without being present, including ‘postmemorial witnessing’ (Heckner, Citation2008), ‘vicarious witnessing’ (Keats, Citation2005; Zeitlin, Citation1998), ‘mechanical witnessing’ (Baer, Citation2005), ‘distant witnessing’ (Liss, Citation1998) and ‘artifactual testimony’ (Liss, Citation2000).

In media studies the concept of witnessing is said to offer fresh perspectives on problems of representation, mediation and reception (Frosh & Pinchevski, Citation2009). An important touchstone for these debates is Peters’ proposal to conceptually unpack witnessing as an ‘intricately tangled practice’ (Citation2001). He suggests witnessing can be ‘in’ the media (eg. eyewitnesses), ‘of’ the media (eg. studio audiences) or ‘via’ the media (eg. television audiences), and that it can be construed in terms of:

[…] an actor (one who bears witness), an act (the making of a special sort of statement), the semiotic residue of that act (the statement as text) or the inward experience that authorises the statement (the witnessing of an event). (Peters, Citation2001, p. 709)

Others challenge or relax the emphasis on singularity and presence. Frosh emphasises the active role of the audience as ‘performative co-constructor of witnessing as a form of discourse and experience’ (Citation2009). Kyriakidou examines how audience engagement can be configured as witnessing, including affective, ecstatic, politicised and detached varieties (Citation2015). Wagner-Pacifici argues that witnessing can be viewed as a collective accomplishment, as a ‘network of cross-witnessing (co-signers and countersigners) that escorts an event across the threshold of history’ (Citation2005, p. 55). Yet while acknowledging that ‘collective witnessing has a certain power’, she suggests that for it to be considered ‘responsible and competent’ it ‘must take a singular, individual form’, for example through the performance of signatures or oaths (Citation2005, p. 48).

Others emphasise the role of digital technologies in facilitating witnessing through the production and sharing of media content. Chouliaraki defines ‘digital witnessing’ as ‘the moral engagement with distant suffering through mobile media, by means of recording, uploading and sharing’ (Citation2015a, Citation2015b), arguing this can raise questions about non-professional content as well as challenging the centrality of established professionals and organisations. The proliferation of devices capable of producing and distributing online content is said to enable ‘distant witnessing’ (Gregory, Citation2015; Martini, Citation2018), ‘connective witnessing’ (Mortensen, Citation2015), ‘citizen witnessing’ (Allan, Citation2013), and ‘civilian witnessing’ (McPherson, Citation2012). These represent a shift from the singular experiences of individuals which are surfaced through textual practices, towards witnessing as the configuration of relations between events, producers, consumers, content and technologies.

The notion of ‘virtual witnessing’ has gained traction in science and technology studies, developed in Shapin and Schaffer’s research on air-pump experiments in the seventeenth century (Citation2011). Virtual witnessing is considered a ‘powerful technology for constituting matters of fact’ through the ‘production in a reader’s mind of such an image of an experimental scene as obviates the necessity for either direct witness or replication’ (Citation2011, p. 60). The authors argue that virtual witnessing is a collective act achieved through a combination of material technologies, such as the operation of the air pump; literary technologies, such as the journal article; and social technologies, such as the epistemic conventions for handling knowledge claims (Citation2011, p. 25). Influential reinterpretations include Latour’s emphasis on the ‘testimony of nonhumans’ (Citation1993, p. 22) and Haraway’s counter-proposal to the self-invisible and exclusionary gentleman-witness with the modified ‘modest witness’ that ‘insists on its situatedness’ (Citation2018).

The concept of ‘data witnessing’ attends to how situations can be accounted for and responded to with data. Like virtual witnessing it explores the witnessing’s collective dimensions, including the involvement of non-human actors. Following media witnessing it examines not just the production of facts, but also the articulation of affect, care, concern and solidarity. Whilst recent work on media witnessing emphasises the production and sharing of content, the accounts below examine the co-production of witnessing through data which both organises and is organised by remote, distributed actors. This article draws on both media and scientific witnessing (Leach, Citation2009), as well as recent work using perspectives from science studies to examine the enrolment of objects as ‘material witnesses’ to injustice (Forensic Architecture, Citation2014; Schuppli, Citation2014; Weizman, Citation2017). The study of data practices may suggest other ways of doing witnessing than those focusing on the singularity and immediacy of experience, instead focusing on socio-technical construction of intelligibility (Gray, Citation2018), response-ability (Haraway, Citation2016) and relationality (Star & Ruhleder, Citation1996) with data.

The following accounts of Decoders projects are based on interviews with Amnesty staff and collaborators;Footnote1 analysis of websites, reports, software repositories and workshop materials; and through participation in events and online activities. They focus on the configuration of data witnessing and how participation was organised through the Decoders projects. Previous research examines Amnesty’s organisational structure (Candler, Citation2001; Wong, Citation2012); networked character (Kahler, Citation2015; Land, Citation2009); branding, content and communicative practices (Chouliaraki, Citation2010; Vestergaard, Citation2008); and many other aspects. The data witnessing of Amnesty’s Decoders may be viewed as part of its ‘digital action repertoires’ (Selander & Jarvenpaa, Citation2016). Rather than focusing exclusively on the products of quantification or datafication, these projects may be viewed in relational terms – as ‘data assemblages’ (Kitchin, Citation2014; Kitchin & Lauriault, Citation2018) or ‘media ensembles’ (Moats, Citation2017) – in order to examine who and what data witnessing can attend to and assemble, in what capacity and to what end.

The configuration of data witnessing at Amnesty Decoders

An Amnesty proposal called ‘Alt Click’ sought to explore how to utilise large volumes of digital data to advance advocacy against abuses, as well as how digital technologies might enable ‘deeper’ and ‘more meaningful’ forms of volunteer engagement beyond social media sharing and signing online petitions. By combining these aspirations, the project would enable volunteers to become ‘human rights monitors’ contributing to ‘information and research challenges’ through a ‘global digital action platform’, piloting tools and methods for documenting abuses with sources such as satellite and social media data (Gough, Citation2014).

Drawing on previous projects which used satellite imagery to ‘watch over’ vulnerable villages (Aradau & Hill, Citation2013; Parks, Citation2009), Alt Click would address the research challenge of ‘data overload’ while enabling volunteers to contribute and participate beyond established action formats. Alt Click gave rise to two initiatives: a ‘Digital Verification Corps’ training volunteers in ‘open source investigation’ methods over several months; and another part in which ‘anyone can be involved’ which became Amnesty Decoders.

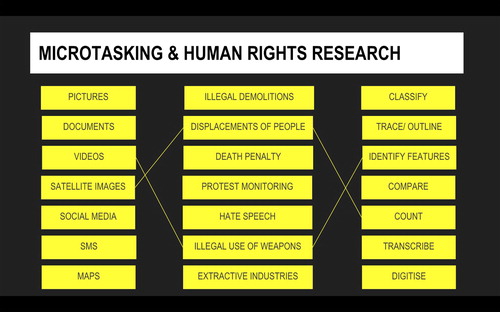

Amnesty explored possibilities for Decoders projects through a series of research, design and user workshops organised at their offices and at public events such as MozFest. These gathered staff from across the organisation as well as invited experts, volunteers and event participants. Instead of ‘crowdsourcing’ (associated with Amazon’s Mechanical Turk), Amnesty preferred the term ‘microtasking’: ‘splitting a large job into small tasks that can be distributed, over the Internet, to many people’ (The Engine Room & Amnesty International, Citation2016). To explore their own way of doing participation with data Amnesty reviewed tools and platforms; learnings from previous projects (privacy, ethics, data integrity, design); and types of microtasking operations (). This research emphasised how microtasking is a collective undertaking, such that input would be usable only if verified by several users and confirmed statistically or through consensus. While Wagner-Pacifici notes that historically witnessing was often underpinned by individual performances (e.g., signatures), Amnesty opted for witnessing collectives with anonymous contributors, resonating with her metaphor that ‘the Greek chorus may be said to derive its voice from its nature as an assembly’ (Citation2005, p. 47).

Flip charts and post-it notes () were used to materialise and order possibilities (Mattern, Citationforthcoming), leading to criteria for evaluating projects such as ‘taskability’, the extent to which a situation could be rendered through microtasking. For distant renderings of injustice to be durable (Boltanski, Citation1999, p. 7), the translation of different situations into structured data would need to be both conventionalised (to create shared understandings and classifications), and experimental (involving novel configurations of relations between actors, methods, sources).

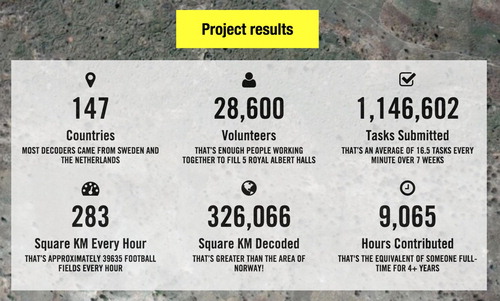

Drawing on agile and user-centric design practices, projects were developed through value propositions, personas, user journeys, paper prototypes, functional prototypes, sprints, stand-ups and testing sessions. The ‘configuration of the user’ (Woolgar, Citation1990) emerged through an interplay between researchers, volunteers and media artefacts. The projects were designed to be conspicuously collective, such as through summaries enumerating the involvement of others (). Volunteers said they valued the community spirit and sense of connection.

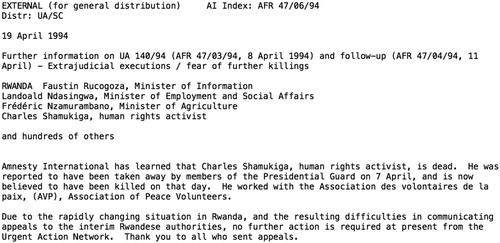

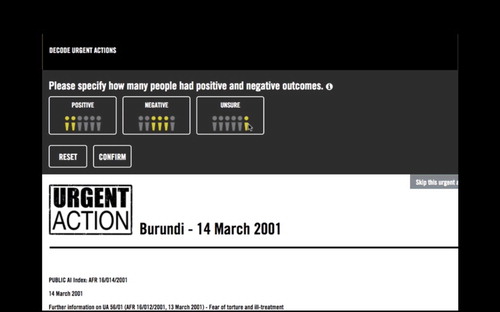

Decode Urgent Actions: witnessing historical abuses with structured data from digitised documents

After these initial workshops in 2015–2016, the first Decoders project was inspired by the project coordinator’s discovery that figures about Urgent Actions were calculated manually on a case-by-case basis, rather than through ‘structured data’. The archives team had decades of Urgent Action (UA) documents, with identifiers and some metadata, but in many different formats (WordPerfect to microfilm). Some, but not all, had been digitised. These originated from Amnesty’s sections, and embodied different practices for ‘sorting out’ (Bowker & Star, Citation2000) their objects of care and concern. Staff commensurated over 500 categories into 17 categories and 44 sub-categories (Espeland & Stevens, Citation1998), noting: ‘this is not a snapshot of human rights situations around the world but rather the work that we do’. As well as the stability of categories such as ‘prisoners of conscience’ and ‘fear of torture or ill-treatment’, there were also notable changes. For example, ‘trade unionists’ tailed off after the 1980s and ‘human rights defenders’ rose to prominence in the 2000s.

The UA archive was a collection of textual descriptions of separate incidents (), and not amenable to analysis in the same way as structured data. The task was thus to ‘extract’ structured data from documents. But what could be extracted, and which data was a priority for both Amnesty researchers and for engaging volunteers? In further workshops in 2016, participants annotated printed UAs to explore the intersection between analytical priorities and what could be known from the archives. Many questions could only be answered by information contained in a minority of documents. The challenge was to identify ‘which were the most relevant questions which could be answered using the most documents’, and to decide on a subset of the 20,000 digitised UAs. Amnesty explored the possibilities of text analysis, including automatically extracting data on country and region, as well as using keywords and regular expressions to detect different kinds of UAs. They opted to focus on 2,800 ‘stop actions’ giving outcomes at the end of campaigning activities.

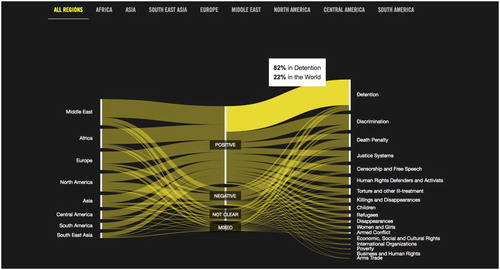

The project sought to render historical human rights situations legible through data at scale and across space and time, by translating archival documents into structured data. Building on harmonised categories and harvested data, the Decoders read texts and generated additional data through user interface features, including numbers of people involved, their genders and whether outcomes were ‘positive’ or ‘negative’ (), according with parameters for attending to injustices through data that were established in the design workshops. Thousands of volunteers read and created data about 2,443 actions, which was used as the basis for statistics and visualisations (). The data witnessing apparatus in this project was intended to render past injustices and Amnesty’s work intelligible at a distance through the addition of structured data fields, connecting historical events and contemporary volunteers through engagement with organisational memory.

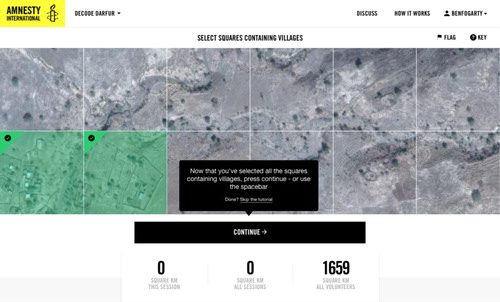

Decode Darfur: witnessing the destruction of villages with satellite imagery and machine learning

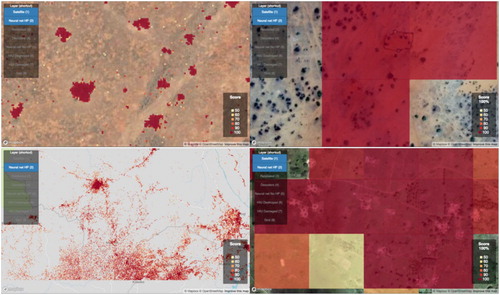

The second project aimed to identify the destruction of villages in Darfur through volunteer classification of satellite imagery, which informed experiments in algorithmic classification. In particular it sought to document sites which were inaccessible to civil society observers, embodying a machine-assisted, forensic sensibility for injustice (Forensic Architecture, Citation2014). Decode Darfur built on previous research on violence in Darfur, combining satellite imagery, photographs and eyewitness interviews. Satellite imagery was intended to function with other sources, such that there would be ‘bits of evidence corroborating each other’. Due to the large surface area being covered the project was divided into two parts: identifying human settlements and identifying possible destruction.

After a training sequence, Decode Darfur asked users to select tiles which showed evidence of human settlement (). In Decode the Difference satellite imagery of settlements from different dates was used to compare ‘before’ and ‘after’ pictures. As Weizman and Weizman comment, ‘before and after’ pictures were partly a byproduct of early photographic processes which tended to miss moving figures, and the gap between them can be ‘considered as a reservoir of imagined images and possible histories’ standing in need of elaboration (Forensic Architecture, Citation2014, p. 109; Weizman & Weizman, Citation2014). In addition to accompanying materials from Amnesty, a new feature for involving volunteers, the Decoders forum, served as a space for such supplementary interpretation, imagination and emotion.

The forum became a space for curiosity, concern, mystery, sadness and consolation. Messages were exchanged about scorched soil, strange lights and colours, unidentifiable objects, caves, agricultural features, storms and dust clouds, military camps, burning vegetation, brick factories, solar cooking devices, railways and bridges, churches, animals and airstrips. The forum served as a site for collective sensemaking (Weick, Citation1995), the schematisation of seeing with satellite imagery and the emergence of conventions for recognising, classifying and coding phenomena (Goodwin, Citation1994). Rather than focusing exclusively on the doing of the task, the forum served as a space where Decoders expressed appreciation for sublime landscapes, ‘guesstimated’ the sizes of objects, lamented ‘absolute devastation’, exchanged news about the conflict and shared photographs of village life prior to the violence. Some found the satellite imagery so depressing they had to pause; others were grateful to work for justice, peace and solidarity with a community from around the world.

Volunteer data was used to train machine-learning algorithms to identify settlements and sites of potential destruction, framing the task as a ‘multi-task binary classification problem’ (Cornebise, Worrall, Farfour, & Marin, Citation2018). Using ‘Krippendorff’s Alpha’, an inter-coder reliability measure developed in communications research (Krippendorff, Citation2011), it was found that Decoders were more accurate as a collective rather than as individuals: ‘even though individually diverse, in aggregate, the crowd’s vote is very much in agreement with Milena, agreeing 89% more often than by chance’ (Cornebise, Citation2017; ). The data was used to train a deep neural network, ResNet-50, to identify settlements beyond the region that volunteers worked on (Cornebise et al., Citation2018). Identifying destruction over time depended on prohibitively expensive, high-resolution historical satellite imagery. The volunteer leading the research counselled modesty in ambition and care in interpreting results. While this is work-in-progress, such experiments have elicited significant interest, with one report describing the potential of machine-learning at Amnesty as ‘extremely promising’.

Figure 8. Visualisations of settlements identified by machine-learning algorithm (Cornebise et al., Citation2018).

In these projects, data witnessing can be envisaged as a ‘collective operational formation’ (Mackenzie, Citation2017, p. 229) of algorithms, imagery, interface components and volunteers. The projects interweave scientific-evidential and social-experiential modes. On the one hand, the aspiration to train machine-learning algorithms to identify sites of destruction at scale resonates with what Collins and Kusch call ‘mimeomorphic’ action, which is ‘informed by our intention to do things in the same way’ (Citation1999, p. 36). On the other hand, volunteer engagement is not exhausted by such aspirations: forum contributions can be more aptly characterised as ‘polimorphic’ – or ‘many-shaped and [taking] their shape from society’ (Citation1999, p. 37) – manifesting care, solidarity and concern with those in sites of destruction. As well as documenting systematic violence with structured data for future legal action, the project also aimed to increase public attention around a ‘forgotten conflict’ through ‘thousands of people looking at Darfur’, enacting and sustaining relations between sites of destruction and Amnesty volunteers.

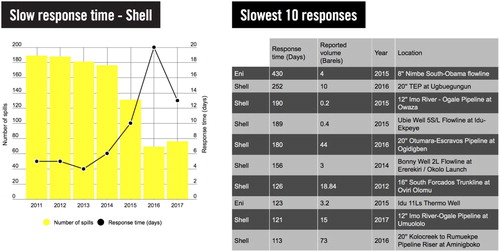

Decode oil spills: witnessing environmental injustice at scale in the Niger Delta with enumerated entities from the transcription of reports

The third project sought to create ‘the first independent, structured databases of oil spills in the Niger Delta’. Data was gathered from official reports and photographs, which were used to quantify inaction and explore inconsistencies in official accounts. The project thereby inventively repurposed existing reporting mechanisms (Gray, Gerlitz, & Bounegru, Citation2018) to challenge and provide alternatives to ‘modes of authorised seeing’ (Jasanoff, Citation2017) and to attend to the destruction of environments undergirding the lives of people in affected regions.

Amnesty began its Niger Delta work in the 1990s around the time of disappearances, extrajudicial killings and executions of protestors such as writer-activist Ken Saro-Wiwa. In cases such as the 2008 Bodo spill Amnesty argued that Shell sought to avoid responsibility and massively understated the scale of spillages. Amnesty campaigned for a full clean-up and compensation, invoking satellite imagery and testimonies from local people and arguing that official mechanisms were failing (Amnesty International, Citation2011). They argued that the spills represented ‘systematic corporate failure’ and that issues around them were ‘the rule rather than the exception’ (38). Amnesty argued that analysis of Joint Investigation Visit (JIV) forms from the National Oil Spill Detection and Response Agency suggested ‘systemic flaws in the system for investigating oil spills in the Niger Delta’ and ‘serious discrepancies between the evidence and the oil companies’ claims’ (Amnesty International, Citation2013).

As opposed to earlier cases such as individual prisoners of conscience, in the Niger Delta Amnesty sought to draw attention to a broader societal situation: problematic material infrastructures and their owners, regulators and effects on local environments and communities. While attending to environmental destruction could suggest an interest in ‘nonhuman rights’ (Forensic Architecture, Citation2014), Amnesty’s focus was on how the destruction of these environments affected the lives of local people, including fishing, water and health, arguing that the government was ‘failing to fulfil its duty to protect the human rights of people living in the Niger Delta’ (Amnesty International, Citation2015).

Building on previous Amnesty research, a preliminary analysis identified variations in forms used to report oil spills (). Different form types could be assigned different templates to enable volunteers to transcribe them through three separate activities: transcribing causes, transcribing locations and interpreting photos.

As one researcher commented, the most important thing was that ‘everything [was] on a single spreadsheet’. This enabled the production of new ‘enumerated entities’ (Verran, Citation2015) to account for spills across space and time, such as averages (‘an average of seven days to respond to each spill’); percentages (‘Shell responded within 24 h of a spill occurring on only 26% of occasions’); and totals (‘Shell since 2011: 1,010 spills’). It also enabled the identification of outliers and the analysis and ranking of spills with tables and graphs (). While reports are legally required within 24 h, Amnesty could thus quantify how much longer it often took, thus substantiating claims of ‘systematic flaws’, rather than isolated problematic incidents (Amnesty International, Citation2018a).

Rather than taking official reports at face value, Amnesty highlighted inconsistencies within and across them to ‘show tensions, push for better information, get things moving’. The project may thus be read as a kind of ‘immanent critique’ where available evidence is taken as partial and provisional and used to tease out contradictions and establish ‘best case scenarios’, even if the number and scale of spills may be significantly worse. The intervention was also ‘immanent’ in the sense that the government was ‘failing to enforce its own rules’ (let alone other norms or ambitions). Just as transparency initiatives assemble publics around pipelines (Barry, Citation2013a, Citation2013b), so the Decoders assembled collectives to interrogate official accounts.

The forum played a vital role in the data witnessing apparatus, surfacing issues around transcription and interpretation (eg. difficult handwriting, different geographical coordinate systems), soliciting for second opinions and flagging notable reports. Decoders discussed reports which suggested illegal activity without police being informed, photographs suggesting corrosion rather than drilling, discrepancies between dates and boxes ticked, and cases of disagreement between companies and community representatives. Forum discussions also led to a new category for labelling photographs (‘damage to previous repair’), which was incorporated into the database. As well as serving as a space for collective deliberation around the interpretation of reports, forum users contemplated destruction and distress to local communities; shared sadness, anger and frustration about failures of companies and regulators; and expressed support for each other and solidarity with those affected. The volunteers included residents of the Delta seeking justice for their communities.

One researcher at Amnesty suggested that while ‘traditional human rights work revolves around testimony’, it appeared that testimony alone ‘doesn’t work in the Niger Delta’, and that the analysis of Decode Oil Spills could open up new avenues for inquiry and action. The project was framed as ‘How 3,500 activists took on Shell’ and ‘the equivalent of someone working full-time for eight months’. Rather than a one-to-one relation between witness and event, the project emphasised many-to-many relations between Decoders and situations of injustice, as a way to find fresh perspectives and to perpetuate international pressure.

Troll Patrol: witnessing online abuse through the classification of Twitter data

The fourth project sought to extend human rights to online spaces by attending to abuse on Twitter. It emerged from previous work by the technology and human rights team at Amnesty, including a report on women’s experiences of online abuse, including silencing effects, self-censorship, psychological harms and ‘the intersectional nature of abuse on the platform’ (Amnesty International, Citation2018b). Rather than focusing on separate incidents, these activities drew attention to abuse as a systemic issue such that inaction by Twitter created the conditions for – as one woman who was subject to abuse put it – ‘institutional racism’, ‘institutional misogyny’ and ‘institutional xenophobia’. Amnesty positioned Twitter’s neglect of abuse as a human rights issue, invoking UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights.

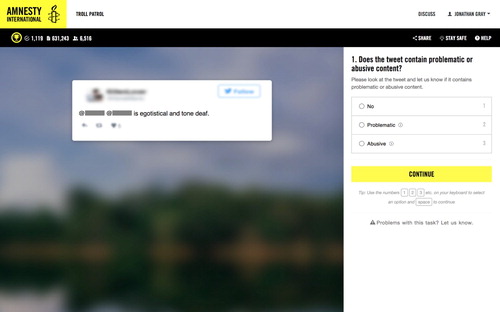

After exploring this topic at a ‘Hack4Charity’ hackathon in London in June 2017 co-organised with Accenture Analytics, Amnesty engaged a data scientist for sentiment analysis and machine learning on Twitter data pertaining to women MPs in the UK, with initial findings suggesting that 2.85% of such tweets were abusive (Dhrodia, Citation2017; Stambolieva, Citation2017). They established that keywords alone would not be sufficient to understand the scale of abuse. The project thus sought to identify and classify abuse with volunteers, informing further experimentation with machine learning. Early discussions about data collection, sampling and methodology raised questions about best how to create and justify lists of accounts. After making large lists based on desk research and scraping, staff were concerned that this did not constitute ‘a cohesive population of women’. They opted to focus on profession, compiling a list of 1000 journalists and politicians, and retrieving 6 million tweets which mentioned them through a third-party analytics company.

Decoders were shown one tweet at a time and asked to classify it as ‘abusive’, ‘problematic’ or neither (). If a tweet was abusive, they were asked to select further subcategories such as ‘Sexism or misogyny’, ‘Racism’, ‘Homophobia or transphobia’, ‘Ethnic or religious slurs’, and then specify whether abuse was contained in text, video, image or an attachment. Amnesty was particularly interested in ‘intersectional discrimination’, or abuse across multiple categories. The tweets were decontextualized, revealing neither poster, target or thread. Platform features such as retweets and likes were also redacted, constituting a kind of ‘demetrification’ (Grosser, Citation2014). This was partly as they ‘didn’t want to focus on the perpetrators, but on women’s experiences of abuse’.

Forum discussions examined edge cases, hypothesised about context, unpicked tweets that alluded to violence in films or extremist subcultures and contemplated how to make sense of ‘creative’ abuse (eg. tactics to evade hate speech rules). Decoders discussed what it would be like to have tweets directed at them; consoled each other in relation to violent imagery and slurs; and encouraged regular breaks. Volunteers proposed other kinds of categories of abuse for future projects and discussed the balance between removing problematic content and enabling free speech.

As well as expressing solidarity and validation for women who experience abuse, the project introduced a human rights frame for online abuse, arguing volunteers ‘bearing witness by classifying tweets have a much deeper experience of abuse online than by signing a petition’. Troll Patrol examined not only abusive content, but also how content was mediated by Twitter, including ‘pile-ons’ of abuse, spikes with media events as well as ‘outpourings of solidarity’. It enabled the quantification of injustice at scale through claims such as ‘7.1% of tweets sent to the women in the study were problematic or abusive’, and ‘black women were disproportionately targeted’.

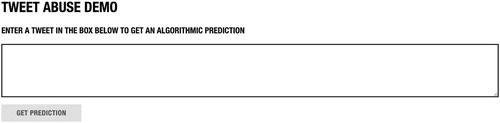

Troll patrol also included a ‘Tweet abuse demo’ () which used machine-learning algorithms to assess whether a given tweet was abusive or problematic. This experimentation was not intended to endorse automated content removal on the platform side, which raised many other issues, including free speech and other ‘risks to human rights’. It was rather intended to advance civil society experimentation to account for and respond to both the dynamics and scale of online abuse, as well as to ‘demonstrate the potential and current limitations of AI technology’ in abuse detection and to make the case for transparency around automated systems (Amnesty International, Citation2018c).

Conclusion: data witnessing and/as data politics?

The concept of ‘data witnessing’ is intended as a lens through which to attend to particular aspects of contemporary data practice, drawing on previous work on media witnessing and virtual witnessing. In this article I have introduced the concept with reference to empirical research on Amnesty Decoders projects which assemble data witnessing collectives to attend to the systemic character of injustices across space and time, beyond isolated incidents. This is not to suggest that all activist or human rights data work should be construed as data witnessing (as opposed to, say, reporting or analysis). Like other forms of witnessing, the aptness of the term depends on the setting, the organisation of relations and the configuration of activity. In the case of Amnesty, witnessing is an important part of the organisation’s history and identity and the term has been explicitly used by Decoders staff and collaborators (Cornebise et al., Citation2018).

In the projects above, data witnessing involves the ‘parameterisation’ of situations of injustice, articulating actors, relations, events, spatiality, temporality and activity as data. This schematisation of that which is witnessed is co-produced through a combination of existing materials of varying levels of proximity to situations of injustice (eg. archives, satellite images, reports, tweets); design processes of ‘taskification’ (eg. user experience and software development practices); campaigning, research and organisational objectives (eg. documenting violations of state and corporate rules); and volunteer activities (eg. proposing new categories, developing classificatory conventions).

Data witnessing encodes, enacts and enables different social, cultural and political approaches to injustice, giving rise to media objects such as structured databases, maps, visualisations, machine learning algorithms and new sets of ‘enumerated entities’ (Verran, Citation2015). As well as enabling different ways of ‘telling about society’ through representations of injustice (Becker, Citation2007), data witnessing involves the gathering of publics to assemble data through which such representations can be produced. It can contribute to the study of media witnessing by examining how – in contrast to the singular experience of the individual at the scene – witnessing can be envisaged as collective, mediated, distributed across space and time, and accomplished with the involvement of a plethora of both human and non-human actors. It can be understood in relation to previous studies of ‘information politics’ at Amnesty and beyond, which may ‘produce overemphasis on some areas, to the detriment of others’ (Keck & Sikkink, Citation1998; Ron, Ramos, & Rodgers, Citation2005). It may also be informative for research on statactivism (Bruno, Didier, & Vitale, Citation2014), data activism (Milan & Velden, Citation2016), data justice (Dencik, Hintz, & Cable, Citation2016) and data politics (Ruppert, Isin, & Bigo, Citation2017). The Decoders projects may be viewed in terms of their ontological politics – the socio-technical articulation of actors, relations, sites and categories of injustice through data.

As well as asking who and what is witnessed (i.e., how different aspects of collective life are articulated and attended to), the projects above also raise questions about who and what is doing witnessing, and how participation in witnessing is materially organised (Marres, Citation2012, Citation2017). While previous work on crowdsourcing and gamification has emphasised the economics and labour of information production (Scholz, Citation2012), the Decoders projects suggest how ‘microtasking’ at Amnesty is not exhausted by its information-processing or labour-saving functions. Congruent with other recent studies (Kennedy & Engebretsen, Citation2019; Kennedy & Hill, Citation2017), these projects show how data projects can have affective dimensions. The forum plays a role in shifting emphasis from ‘I’ to ‘we’ as the subject of witnessing, and in making space for the collective articulation of experience and emotion, not just the instrumental production of evidence. Previous work on witnessing raises questions of who has voice and agency, who has the right to be heard and who deserves protection (Chouliaraki, Citation2015b). The ‘we’ of the Decoders comprises a shifting transnational assembly of places where Amnesty has sections and places where it does not, as well as enabling unexpected alliances as a result of spill overs between projects.

The collective character of data witnessing is by design in these projects, partly as microtasking contributions were found to be most reliable in aggregate. The Decoders initiative was also attentive to potential risks and harms to both volunteers as well as those to whom injustice is done. While previous research cautions against the dark side of data systems (Seltzer & Anderson, Citation2001) as well as threats of ‘dataveillance’ (Lupton & Williamson, Citation2017), the Decoders projects started with workshops on privacy, harm reduction and ‘responsible data’ and many focus on injustice at scale, rather than on the datafication of individuals. Thus, datafication represents a departure from witnessing as ‘the transformation of experience to discourse, of private sensation to public words’ (Kyriakidou, Citation2015). Data witnessing is rather a collective accomplishment which enables concern and solidarity to be extended across space and time, as opposed to the ‘thereness’ of singular personal experience.

But what is the cost of this shift from the individual to the collective character of injustice? Could data witnessing excessively abstract and decontextualize injustice and suffering, as Boltanski puts it, as a ‘massification of a collection of unfortunates who are not there in person’ (Citation1999, p. 13)? In shifting from individual testimony to the commensuration, quantification and analysis of injustice ‘at a distance’ through data, might this displace or distract from compassion for the individual that is elicited by testimony from those present in space and time? Hill argues that ‘minimal presentations’ are not inherently less likely to elicit a sense of responsibility that accompanies witnessing than ‘affective coverage’ and that such an assumption undermines the active role of audiences in the construction of meaning (Hill, Citation2018). Furthermore the above projects suggest that Amnesty campaigners assume that these data witnessing experiments will not function in isolation, but in tandem with other research and campaigning activities (online and offline), and their attendant modes of representation (texts, images, videos), as can be seen in reports on Decoders projects.

Conversely, it may be argued that Decoders projects do not go far enough in shifting focus from individual to systemic injustices and relating incidents of abuse to broader narratives and structures of colonialism, energy politics, capital, class, patriarchy and power. Such concerns are raised in debates about the ‘humanitarian’ and the ‘political’ (Boltanski, Citation1999, p. 91) and the notion that the ‘era of the witness’ coincides with a moment of ‘individuating and thus depoliticising complex collective histories’ (Weizman, Citation2017, p. 81). This may reflect contrasts between ‘politics of pity’ and ‘politics of justice’ (Arendt, Citation1990; Boltanski, Citation1999). Critics of the hegemony of human rights (D’Souza, Citation2017; Geuss, Citation2001; Geuss & Hamilton, Citation2013; Moyn, Citation2012, Citation2014) may raise questions about how data and digital technologies are involved in construing situations of injustice as human rights situations, as opposed to other kinds of ‘political situations’ (Barry, Citation2012). While Amnesty Decoders does indeed emerge from human rights work, the social and political possibilities of data witnessing – and the associated ways in which care, concern and solidarity may be constructed, structured, extended and delimited by means of digital data – remain a matter for both ongoing experimentation and further research.

Acknowledgements

Thanks are due to Claudia Aradau, Tobias Blanke, Liliana Bounegru, Geoffrey Bowker, Lilie Chouliaraki, Shannon Mattern, Susan Schuppli, Robin Pacifici-Wagner and Lonneke van der Velden for their invaluable comments, correspondence and suggestions throughout the process of writing this article. The empirical research in this paper would not have been possible without time and input from Milena Marin at Amnesty International, to whom I am most grateful for introducing me to the Decoders initiative and for many interesting conversations and reflections. Building up a corpus of notes and materials on the configuration of practices, technologies, approaches and organisational settings of Amnesty Decoders was possible thanks to discussions with David Acton, Julien Cornebise, Azmina Dhrodia, Mark Dummett, Scott Edwards, Ben Fogarty, Sauro Scarpelli and others involved in the project. Richard Rogers and the Digital Methods Initiative at the University of Amsterdam always provide an inspiring environment for exploratory empirical work, which in this case included looking at the the Decoders projects from a digital methods perspective at the Winter School 2016 (with Olga Boichak, Liliana Bounegru, Agata Brilli, Claudia Minchilli, Coral Negrón, Mariasilvia Poltronieri, Chiara Riente, Gülüm Şener and Paola Verhaert) and the Summer School 2018 (with Aurelio Amaral, Derrek Xavier Chundelikatt, Maarten Groen, Jesper Hinze, Jiyoung Ydun Kim, J. Clark Powers, Tommaso Renzini, Caroline Sinders, Yarden Skop, Ginevra Terenghi, Felipe Escobar Vega, Ros Williams and Ilaria Zonda). Thanks to Lina Dencik, Stefania Milan, Morgan Currie, Gabriel Pereira, Bruno Moreschi, Silvia Semenzin, Minna Ruckenstein and other organisers and discussants at the 2018 Data Justice Conference at Cardiff University, which was a perfect venue for the first public outing of this research. I received useful feedback on the full paper at the Digital Society Network, University of Sheffield, thanks to Helen Kennedy, Elisa Serafinelli, Ysabel Gerrard, Lulu Pinney, Lukasz Szulc, Warren Pearce, Ataur Belal and other participants. I'm most appreciative of support from Joanna Redden and Emiliano Treré during the review process and of excellent suggestions from two anonymous reviewers. Finally, discussions with my graduate students on the "data activism" module at King's College London are an ongoing source of reflection and inventiveness for further empirical work and experiments with data witnessing.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes on contributors

Dr Jonathan Gray is Lecturer in Critical Infrastructure Studies at the Department of Digital Humanities, King’s College London, where he is currently writing a book on data worlds. He is also Cofounder of the Public Data Lab; and Research Associate at the Digital Methods Initiative (University of Amsterdam) and the médialab (Sciences Po, Paris). More about his work can be found at jonathangray.org and he tweets at @jwyg.

ORCID

Jonathan Gray http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6668-5899

Notes

1 Including the Decoders project coordinator, staff in Amnesty campaigning and research teams, contract designers and software developers and a volunteer machine learning expert. Interviews were conducted from 2016–2018 at Amnesty’s offices and through video chat.

References

- Allan, S. (2013). Citizen witnessing: Revisioning journalism in times of crisis. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

- Amnesty Decoders. (2018). Become an Amnesty Decoder. Retrieved from https://decoders.amnesty.org

- Amnesty International. (2011). Nigeria: The true ‘tragedy’: Delays and failures in tackling oil spills in the Niger Delta. London: Author.

- Amnesty International. (2013). Nigeria: Bad information: Oil spill investigations in the Niger Delta. London: Author.

- Amnesty International. (2015). Nigeria: Clean it up: Shell’s false claims about oil spill response in the Niger Delta. London: Author.

- Amnesty International. (2018a). Negligence in the Niger Delta: Decoding Shell and Eni’s poor record on oil spills. London: Author.

- Amnesty International. (2018b). Toxic Twitter - a toxic place for women. London: Author.

- Amnesty International. (2018c). Troll Patrol findings. London: Amnesty International. Retrieved from https://decoders.amnesty.org/projects/troll-patrol/findings

- Aradau, C., & Hill, A. (2013). The politics of drawing: Children, evidence, and the Darfur conflict. International Political Sociology, 7, 368–387. doi: 10.1111/ips.12029

- Arendt, H. (1990). On revolution. London: Penguin Books.

- Baer, U. (2005). Spectral evidence: The photography of trauma. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Barry, A. (2012). Political situations: Knowledge controversies in transnational governance. Critical Policy Studies, 6, 324–336. doi: 10.1080/19460171.2012.699234

- Barry, A. (2013a). Material politics: Disputes along the pipeline. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

- Barry, A. (2013b). Transparency as a political device. In M. Akrich, Y. Barthe, F. Muniesa, & P. Mustar (Eds.), Débordements : mélanges offerts à Michel Callon (pp. 21–39). Paris: Presses des Mines.

- Becker, H. S. (2007). Telling about society. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Boltanski, L. (1999). Distant suffering: Morality, media and politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bowker, G. C., & Star, S. L. (2000). Sorting things out: Classification and its consequences. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Bruno, I., Didier, E., & Vitale, T. (2014). Statactivism: Forms of action between Disclosure and Affirmation. Partecipazione e Conflitto, 7, 198–220.

- Buchanan, T. (2002). ‘The Truth will Set You free’: The making of Amnesty International. Journal of Contemporary History, 37, 575–597. doi: 10.1177/00220094020370040501

- Candler, G. G. (2001). Transformations and legitimacy in nonprofit organizations — the case of Amnesty International and the brutalization thesis. Public Organization Review, 1, 355–370. doi: 10.1023/A:1012288930985

- Chouliaraki, L. (2010). Post-humanitarianism: Humanitarian communication beyond a politics of pity. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 13, 107–126. doi: 10.1177/1367877909356720

- Chouliaraki, L. (2015a). Digital witnessing in conflict zones: The politics of remediation. Information, Communication & Society, 18, 1362–1377. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2015.1070890

- Chouliaraki, L. (2015b). Digital witnessing in war journalism: The case of post-Arab Spring conflicts. Popular Communication, 13, 105–119. doi: 10.1080/15405702.2015.1021467

- Collins, H., & Kusch, M. (1999). The shape of actions: What humans and machines can do. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Cornebise, J. (2017). Descriptive statistics on Decoders data. Unpublished.

- Cornebise, J., Worrall, D., Farfour, M., & Marin, M. (2018). Witnessing atrocities: Quantifying villages destruction in Darfur with crowdsourcing and transfer learning. Presented at the AI for Social Good NIPS2018 Workshop, Montréal, Canada.

- Dencik, L., Hintz, A., & Cable, J. (2016). Towards data justice? The ambiguity of anti-surveillance resistance in political activism. Big Data & Society, 3, 1–12. doi: 10.1177/2053951716679678

- Dhrodia, A. (2017). Unsocial media: Tracking Twitter abuse against women MPs. Retrieved from https://medium.com/@AmnestyInsights/unsocial-media-tracking-twitter-abuse-against-women-mps-fc28aeca498a

- D’Souza, R. (2017). What’s wrong with rights?: Social movements, law and liberal imaginations. London: Pluto Press.

- The Engine Room, & Amnesty International. (2016). Microtasking. Retrieved from https://library.theengineroom.org/microtasking/

- Espeland, W. N., & Stevens, M. L. (1998). Commensuration as a social process. Annual Review of Sociology, 24, 313–343. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.24.1.313

- Felman, S., & Laub, D. (1992). Testimony: Crises of witnessing in literature, psychoanalysis, and history. London: Routledge.

- Forensic Architecture. (2014). Forensis: The architecture of public truth. Berlin: Sternberg Press.

- Frosh, P. (2009). Telling presences: Witnessing, mass media, and the imagined lives of strangers. In A. Pinchevski & P. Frosh (Eds.), Media witnessing: Testimony in the age of mass communication (pp. 49–72). Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Frosh, P., & Pinchevski, A. (eds.). (2009). Media witnessing: Testimony in the age of mass communication. Houndmills, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Geuss, R. (2001). History and illusion in politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Geuss, R., & Hamilton, L. (2013). Human rights: A very bad idea. Theoria, 60, 83–103. doi: 10.3167/th.2013.6013505

- Goodwin, C. (1994). Professional vision. American Anthropologist, 96, 606–633. doi: 10.1525/aa.1994.96.3.02a00100

- Gough, J. (2014). Alt-Click: A new generation of human rights activists (Unpublished). London: Amnesty International.

- Gray, J. (2018). Three aspects of data worlds. Krisis: Journal for Contemporary Philosophy, 1, 3–17.

- Gray, J., Gerlitz, C., & Bounegru, L. (2018). Data infrastructure literacy. Big Data & Society, 5, 1–13. doi: 10.1177/2053951718786316

- Gregory, S. (2015). Ubiquitous witnesses: Who creates the evidence and the live(d) experience of human rights violations? Information, Communication & Society, 18, 1378–1392. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2015.1070891

- Grosser, B. (2014). What do metrics want? How quantification prescribes social interaction on Facebook. Computational Culture, 4. Retrieved from http://computationalculture.net/what-do-metrics-want/.

- Haraway, D. J. (2016). Staying with the trouble: Making kin in the Chthulucene. Durham: Duke University Press Books.

- Haraway, D. J. (2018). Modest_Witness@Second_Millennium. FemaleMan©_Meets_OncoMouse™: feminism and technoscience (Second edition). New York: Routledge.

- Heckner, E. (2008). Whose trauma is it? Identification and secondary witnessing in the age of postmemory. In D. Bathrick, B. Prager, & M. D. Richardson (Eds.), Visualizing the Holocaust: Documents, aesthetics, memory (pp. 63–85). Rochester, NY: Camden House.

- Hill, D. W. (2018). Bearing witness, moral responsibility and distant suffering. Theory, Culture & Society, 36(1), 27–45. doi: 10.1177/0263276418776366

- Hirsch, M. (2008). The Generation of postmemory. Poetics Today, 29, 103–128. doi: 10.1215/03335372-2007-019

- Hopgood, S. (2006). Keepers of the flame: Understanding Amnesty International. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Jasanoff, S. (2017). Virtual, visible, and actionable: Data assemblages and the sightlines of justice. Big Data & Society, 4, 1–15. doi: 10.1177/2053951717724477

- Kahler, M. (2015). Networked politics: Agency, power, and governance. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Keats, P. A. (2005). Vicarious witnessing in European concentration camps: Imagining the trauma of another. Traumatology, 11, 171–187. doi: 10.1177/153476560501100303

- Keck, M. E., & Sikkink, K. (1998). Activists beyond borders: Advocacy networks in international politics. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Kennedy, H., & Engebretsen, M. (eds.). (2019). Data visualization in society. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Kennedy, H., & Hill, R. L. (2017). The feeling of numbers: Emotions in everyday engagements with data and their visualisation. Sociology, 52(4), 830–848. doi: 10.1177/0038038516674675

- Kitchin, R. (2014). The data revolution: Big data, open data, data infrastructures and their consequences. London: SAGE.

- Kitchin, R., & Lauriault, T. (2018). Towards critical data studies: Charting and unpacking data assemblages and their work. In J. Thatcher, A. Shears, & J. Eckert (Eds.), Thinking big data in geography: New regimes, new research (pp. 3–20). Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

- Krippendorff, K. (2011). Computing Krippendorff’s Alpha-reliability (p. 12). Philadelphia, PA: Annenberg School for Communication, University of Pennsylvania.

- Kyriakidou, M. (2015). Media witnessing: Exploring the audience of distant suffering. Media, Culture & Society, 37, 215–231. doi: 10.1177/0163443714557981

- Land, M. B. (2009). Networked activism. Harvard Human Rights Journal, 22, 205–243.

- Latour, B. (1993). We have never been modern. (C. Porter, Trans.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Leach, J. (2009). Scientific witness, testimony, and mediation. In P. Frosh & A. Pinchevski (Eds.), Media witnessing: Testimony in the age of mass communication (pp. 182–197). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Liss, A. (1998). Distant witnessing. Afterimage: The Journal of Media Arts and Cultural Criticism, 26(3), 3.

- Liss, A. (2000). Artifactual testimonies and the stagings of Holocaust memory. In R. I. Simon, S. Rosenberg, & C. Eppert (Eds.), Between hope and despair: Pedagogy and the remembrance of historical trauma (pp. 117–133). Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Lupton, D., & Williamson, B. (2017). The datafied child: The dataveillance of children and implications for their rights. New Media & Society, 19, 780–794. doi: 10.1177/1461444816686328

- Mackenzie, A. (2017). Machine learners: Archaeology of a data practice. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Marres, N. (2012). Material participation: Technology, the environment and everyday publics. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Marres, N. (2017). Digital sociology: The reinvention of social research. London: Polity Press.

- Martini, M. (2018). Online distant witnessing and live-streaming activism: Emerging differences in the activation of networked publics. New Media & Society, 20(11), 4035–4055. doi: 10.1177/1461444818766703

- Mattern, S. (forthcoming). Small, moving parts: A century of fiches, fairs, and fantasies.

- McPherson, E. (2012). Digital human rights reporting by civilian witnesses: Surmounting the verification barrier. In R. A. Lind (Ed.), Produsing theory in a digital world 2.0: The intersection of audiences and production in contemporary theory (pp. 193–209). New York: Peter Lang Publishing.

- Milan, S., & Velden, L. v. d. (2016). The alternative epistemologies of data activism. Digital Culture & Society, 2, 57–74. doi: 10.14361/dcs-2016-0205

- Moats, D. (2017). From media technologies to mediated events: A different settlement between media studies and science and technology studies. Information, Communication & Society, 1–16. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2017.1410205

- Mortensen, M. (2015). Connective witnessing: Reconfiguring the relationship between the individual and the collective. Information, Communication & Society, 18, 1393–1406. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2015.1061574

- Moyn, S. (2012). The last utopia: Human rights in history. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Moyn, S. (2014). Human rights and the uses of history. London: Verso.

- Parks, L. (2009). Digging into Google Earth: An analysis of ‘Crisis in Darfur.’ Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 40, 535–545.

- Peters, J. D. (2001). Witnessing. Media, Culture & Society, 23, 707–723. doi: 10.1177/016344301023006002

- Power, J. (1981). Amnesty International: The human rights story. Oxford: Pergamon Press.

- Ron, J., Ramos, H., & Rodgers, K. (2005). Transnational information politics: NGO human rights reporting, 1986–2000. International Studies Quarterly, 49, 557–587. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2478.2005.00377.x

- Ruppert, E., Isin, E., & Bigo, D. (2017). Data politics. Big Data & Society, 4, 1–7. doi: 10.1177/2053951717717749

- Scholz, T. (2012). Digital labor. New York: Routledge.

- Schuppli, S. (2014). Material witness [Video]. Retrieved from http://susanschuppli.com/exhibition/material-witness-2/

- Selander, L., & Jarvenpaa, S. (2016). Digital action repertories and transforming a social movement organization. Management Information Systems Quarterly, 40, 331–352. doi: 10.25300/MISQ/2016/40.2.03

- Seltzer, W., & Anderson, M. (2001). The dark side of numbers: The role of population data systems in human rights abuses. Social Research, 68, 481–513.

- Shapin, S., & Schaffer, S. (2011). Leviathan and the air-pump: Hobbes, Boyle, and the experimental life. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Stambolieva, E. (2017). Methodology: Detecting online abuse against women MPs on Twitter. London: Amnesty International.

- Star, S. L., & Ruhleder, K. (1996). Steps toward an ecology of infrastructure: Design and access for large information spaces. Information Systems Research, 7, 111–134. doi: 10.1287/isre.7.1.111

- Verran, H. (2015). Enumerated entities in public policy and governance. In E. Davis, & P. J. Davis (Eds.), Mathematics, Substance and Surmise (pp. 365–379). New York: Springer, Cham.

- Vestergaard, A. (2008). Humanitarian branding and the media: The case of Amnesty International. Journal of Language and Politics, 7, 471–493. doi: 10.1075/jlp.7.3.07ves

- Wagner-Pacifici, R. (2005). The art of surrender: Decomposing sovereignty at conflict's end. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Weick, K. E. (1995). Sensemaking in organizations. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Weizman, E. (2017). Forensic architecture: Violence at the threshold of detectability. New York: Zone Books.

- Weizman, E., & Weizman, I. (2014). Before and after: Documenting the architecture of disaster. Moscow: Strelka Press.

- Wong, W. H. (2012). Internal affairs: How the structure of NGOs transforms human rights. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Woolgar, S. (1990). Configuring the user: The case of usability trials. The Sociological Review, 38, 58–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-954X.1990.tb03349.x

- Zeitlin, F. I. (1998). The vicarious witness: Belated memory and authorial presence in recent Holocaust literature. History and Memory, 10, 5–42.