ABSTRACT

This paper seeks to illuminate the significance of datafication for anti-poverty programmes, meaning social protection schemes designed specifically for poor people. The conversion of beneficiary populations into machine-readable data enables two core functions of social protection, those of recognising entitled beneficiaries and assigning entitlements connected to each anti-poverty scheme. Drawing on the incorporation of Aadhaar, India’s biometric population database, in the national agenda for social protection, we unpack a techno-rational perspective that crafts datafication as a means to enhance the effectiveness of anti-poverty schemes. Nevertheless, narratives collected in the field show multiple forms of data injustice on recipients, underpinned by Aadhaar’s functionality for a shift of the social protection agenda from in-kind subsidies to cash transfers. Based on such narratives the paper introduces a politically embedded view of data, framing datafication as a transformative force that contributes to reforming existing anti-poverty schemes.

1. Introduction

The concept of datafication implies rendering into data many aspects of the world that had not been quantified before (Cukier & Mayer-Schoenberger, Citation2013, p. 29). Widely studied in business intelligence, datafication is known for its effects on the structuring logic of markets and for its mixed implications on ethics and user privacy (Taylor, Floridi, & Van der Sloot, Citation2016). But an important, yet understudied subfield of data governance pertains to the effects of datafication on social protection programmes, through which basic services are provided to many of the world’s poor. Increasingly taken up in poverty reduction agendas, social protection refers to ‘all public and private initiatives that provide income or consumption transfers to the poor, protect the vulnerable against livelihood risks, and enhance the social status and rights of the marginalised’ (Devereux & Sabates-Wheeler, Citation2004).

Anti-poverty programmes are social protection schemes directed mainly or solely at poor people (Joshi & Moore, Citation2000). Over the last 10–15 years, such schemes have become increasingly computerised on a global scale, making digital technologies an integral part of the back- and front-end of welfare systems (Devereux & Vincent, Citation2010). In this process, computerisation is being paralleled by datafication: data of beneficiaries are being gradually inscribed in programme design, thus becoming directly relevant to entitlement determination. This results in a process of datafication of anti-poverty programmes, which affects the implementation of public welfare schemes worldwide.

Datafication is designed to facilitate two components of anti-poverty programmes, namely user identification and assignation of correct entitlements. The availability of machine-readable data allows for automatised recognition of targeted beneficiaries and is devised to enable reduction in inclusion and exclusion errors (Muralidharan, Niehaus, & Sukhtankar, Citation2016). Furthermore, it enables the correct assignation of resources to beneficiaries for their respective entitlement brackets (Saini, Sharma, Gulati, Hussain, & von Braun, Citation2017). While both functions were originally paper-based or partially digitised, datafication is conceived to automatise them, seeking to infuse greater effectiveness and accountability in programme design.

However, views and empirics on the effects of datafication on recipients’ access to social benefits are mixed. Theories of data justice, meaning ‘fairness in the way people are made visible, represented and treated as a result of their production of digital data’ (Taylor, Citation2017, p. 1), are relevant to illuminate the implications of datafication for anti-poverty programme recipients. The concept of data justice, as Heeks and Renken (Citation2018) argue, has structural drivers that affect development, revealing exposure of the poor to forms of injustice that are specific to a datafied world. Inspired by these accounts, our research question is: how does datafication affect the entitlements of anti-poverty programme recipients?

We seek to answer the question through a case study of datafication of the Public Distribution System (PDS), India’s largest food security scheme, in the southern state of Karnataka. Our case selection is dictated by the ongoing transformation of the Indian PDS through the Unique Identification Project (Aadhaar), which constitutes the world’s biggest infrastructure for biometric identification. By conducting in-depth interviews with multiple actors of the Aadhaar-based PDS, we unpack a techno-rational perspective that hails the system as a means to combat leakage and maximise the effectiveness of the programme. But at the same time, field narratives reveal several forms of data injustice including narrow targeting, misalignment of programmes with policy principles, and exclusion of the entitled from service provision. These forms of data injustice inspire our theorisation of a politically embedded view of data, where datafication acts as a transformative force that contributes to deep reform of social protection agendas.

The rest of this paper is structured as follows. We first illustrate the role of datafication in anti-poverty programmes, highlighting the two functions it is designed to enable. We then review the incorporation of Aadhaar in the Indian PDS, identifying a techno-rational perspective that frames Aadhaar as an enabler of programme effectiveness. Through narratives collected from PDS beneficiaries, we then problematise such perspective, bringing to light three forms of data injustice – legal, design-related, and informational – that were not in place before datafication. Contributing to theorisations of datafication in the Global South, we conclude by introducing a view of data as politically embedded in choices that have multiple, potentially adverse consequences on anti-poverty programme recipients.

2. The datafication of anti-poverty programmes

Over the last 10–15 years, social protection programmes have become increasingly computerised. Digital transformation has affected many phases of anti-poverty schemes: for example, cash transfer systems are moving from physical delivery to mobile money, seeking to bypass the issues of leakage connected to material entitlements (Devereux & Vincent, Citation2010). Employment guarantee programmes have moved to biometric recognition of users, combating problems of deception and illicit inclusion (Muralidharan et al., Citation2016). The back-end phases of social protection schemes are also being digitised by means of ‘end-to-end computerisation’ (Masiero & Prakash, Citation2015).

Datafication is inscribed in this scenario of ongoing computerisation. In the case of social protection schemes, what is datafied is the users’ population, converted into digital databases on whose basis entitlements are determined. Digital technologies afford the translation of individual and household data, previously collected through non-automated census systems (Jerven, Citation2013), into computer records that can be retrieved at all times, acquiring crucial importance for programme management. Through datafication, populations are turned from physical subjects into digital records amenable to consultation, on whose basis administrative decisions are taken.

The lens of datafication, largely used to interpret developments in the domain of market and business intelligence, thus acquires a specific meaning when placed in the context of anti-poverty programmes. Such a meaning is centred on the twofold act of recognising beneficiaries, allowing to discriminate (for example through income data) the entitled from the non-entitled, and assigning the right entitlements to each of them. For example, targeted programmes are designed specifically for users below the poverty line and are predicated on the dichotomy of poor and nonpoor citizens (Devereux, Citation2016). Datafying a population’s records, such phase becomes automated, and computerised recognition of users allows the assignation of the right benefits to each of them.

Shaping such crucial decisions of anti-poverty programme management, datafication converts the lived experience of poverty and vulnerability into machine-readable data, with tangible effects on the lives and livelihoods of the citizens involved. Datafication has been framed as digital enactment of the idea of ‘seeing like a state’, as in Scott’s (Citation1998) argument that colonial powers engaged in proactive production of citizens through means of census and classification. By inscribing citizens into census categories, the state produces a vision of citizens that has direct consequences on how they are managed, and on how social benefits aimed for them are administered. As Hacking (Citation1986) referred to ‘making up people’ with classification, datafication ‘makes’ beneficiaries through census categories that are crystallised through data and made amenable to top-down control.

From an operational point of view, datafication is designed to solve two important issues of anti-poverty programme management, identified as inclusion and exclusion errors (Muralidharan et al., Citation2016). Inclusion errors refer to the illicit inclusion of non-entitled users into programmes, resulting in leakage of benefits to the nonpoor. Exclusion errors refer to the exclusion of genuinely entitled users, based on ill-defined selection criteria or the wrongful implementation of existing ones (Swaminathan, Citation2002). Datafication is tailored to combat both issues, as it allows to assign the programme’s benefits to all those entitled, at the same time excluding everyone else.

The two functions of datafication have great relevance for anti-poverty schemes. A common problem across social protection programmes is that of leakage, meaning the systematic diversion of benefits away from entitled individuals and households (Saini et al., Citation2017). In a context of limited resources, this reduces the goods available to the entitled, who hence need to resort to political connections to seek to obtain their entitlements. Automatising the phases of recognition of users and assignation of entitlements, datafication is inscribed in a positive vision of e-governance, seeing technology as means to streamline and improve existing systems.

A more recently emerged stream of literature, however, problematises this view. As noted by Taylor (Citation2017), the data revolution has been seen primarily as technical, without connecting the power of data to a social justice agenda. In parallel though, an idea of data justice is necessary in a world in which data intervene on processes that were entirely material before, and that affect the lives of the poor and vulnerable in new ways (Arora, Citation2016). The novel concept of data justice, as shown by Heeks and Renken (Citation2018), has structural drivers that affect the condition of the world’s poor.

Theories of data justice – and of the injustices stemming in this respect – have become prominent in the domain of critical data studies. Still, such theories have not yet been applied to the phenomenon of anti-poverty programme datafication delineated here. This leaves a gap in knowledge of the effects of datafication on the entitlements of beneficiaries. It remains to be seen if datafication leads to equitable outcomes and the extent to which minimisation of inclusion and exclusion errors is taking place.

This leads to ask, how does datafication affect the entitlements of anti-poverty programme recipients? The response needs empirical insights on a datafied anti-poverty programme, where the conversion from paper – to data-based is ongoing or has already happened. The Indian state of Karnataka, where datafication of a large anti-poverty scheme is in progress, provides a case of this type.

3. Methodology

Case selection for this paper was motivated by ongoing datafication of the Karnataka PDS, which provided an opportunity to observe effects on beneficiary entitlements. Semi-structured interviews (Riessman, Citation2008) served as the primary method for data collection. We conducted interviews in urban (BTM Stage 1, Koramangala, Belakadi, ISRO Colony, JP Nagar) and semi-urban (Bommanahalli, Vittasandra, Velankani, Doddathogur, Ponappa Agrahara and Ayodhya Nagar) areas of Bangalore, capital city of Karnataka, and in the rural Kolar district; regions were chosen so that difference in operational procedures across urban densities could be understood. Interviews were conducted in farmer-markets, inside and outside PDS ration shops, and at homes of beneficiaries and ration shop owners. The date range of interviews, led between April and August 2018, accounts for variation in operations of ration shops over weekdays and weekends.

A total of 42 people were interviewed over the fieldwork period (). Among the benefit providers we interviewed ration shop owners and workers, and of beneficiaries, we interviewed both in-state and out-state recipients. Interviews were conducted while the PDS identity verification and ration distribution processes (described in Section 4) were underway, which led us to gain a first-hand understanding of the ration delivery process. The age group of the interviewed population was 30–60, with diversified occupations of beneficiaries including shopkeepers, casual labourers in the construction business, retailers at farmer markets, housewives, cab drivers and farmers.

Table 1. Synopsis of interviews.

Our interview data were progressively integrated with statistics, press releases, and governmental information becoming available online on the programme as fieldwork progressed. Our corpus of data was subjected to thematic analysis, meaning the examination of content through categories clustered around thematic units (Riessman, Citation2008). The thematic analysis led us to identify two main perspectives (a techno-rational and a socially embedded view) taken by respondents and to elicit a set of relevant themes under each perspective – including three different forms of data injustice associated to the datafied PDS. The two perspectives have provided a nuanced response to our research question.

4. The datafied PDS in Karnataka

The Indian PDS dates back to 1965, when the Food Corporation of India (FCI) was established as a governmental agency to manage the nation’s food security system. The core purpose of the scheme is that of distributing primary necessity items (primarily rice, wheat, sugar and kerosene) to the poor, at highly subsidised prices to make them accessible to even the poorest households. Commodities are procured by the FCI and distributed all over the nation through fair-price shops, known as ration shops and managed by staff called ration dealers, as all entitled households have a fixed monthly ration of goods they can avail under the programme.

The PDS was originally formulated as a universal programme, which allowed all households to apply for subsidies under the scheme. Yet, through the fiscal crisis of the 1990s, the universal PDS was identified as a burden on expenditure, leading in 1997 to a targeted system which circumscribed subsidies to below-poverty-line (BPL) households. Additional provisions were made, in 2000, for the poorest of the poor, covered by a scheme called Antyodaya Anna Yojana (AAY) and entitled to greater quantities of subsidy under the PDS. Amounts of subsidy for each commodity are established at the state level, and subject to revisions by state ministries of Food and Civil Supplies.

While being one of the largest food security systems worldwide, the PDS is affected by a set of issues that hamper its ability to reach the poor. The main issue is leakage to non-entitled recipients, determined by two simultaneous forces: first, the difference in the price of items between the market and ration shops, leading PDS actors to divert goods to the market (Khera, Citation2011). Second, the difficult financial situation experienced by ration dealers after targeting, which has drastically reduced the number of users and the endangered survival of ration shops. These forces determined the increasing involvement of ration dealers in the illegal trade of PDS goods, known as rice mafia and capable to divert commodities from entitled recipients. As per the latest estimates available, diversion results in 40%–50% of all PDS goods not reaching the poor every year (Saini et al., Citation2017).

Operational decisions on the PDS are taken by state governments, following guidelines provided by the central government on the programme. Shortly after moving to a targeted system, several states resorted to computerisation to monitor the diversion of goods. The government of Karnataka, a southern state with rates of PDS usage well above the Indian average (Khera, Citation2011), was an early mover in computerisation, which in 2005 initiated an online database of PDS users. Based on such database, stored with a state agency known as the Karnataka Corporation of Food and Civil Supplies (KFCSC), ration shops in six districts were equipped with point-of-sale machines configured to sell only to registered users (Masiero & Prakash, Citation2015).

Over the last five years, against the backdrop of state-level projects of this type, India has developed a unifying infrastructure for social protection and welfare systems. This lies in the Unique Identity Project (Aadhaar) launched through the Unique Identity Authority of India (UIDAI), a government agency established in January 2009 under the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology. The Aadhaar system provides all enrolees with an identifying 12-digit number and the capture of biometric details, meaning ten fingerprints and an iris scan. Presented as a means of facilitating access to social benefits (UIDAI, Citation2010), Aadhaar has received a strong promotional push by the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) government in power since 2014: with the setup of enrolment centres all over the nation and the increasing incorporation in public services, in 2018 Aadhaar has reached an enrolment rate above 89.9% of the Indian population, and is today the largest biometric identification infrastructure ever created in history.

Motivated by central government guidelines (Government of India, Citation2015) inviting states to shift to an Aadhaar-enabled PDS, state governments have started incorporating Aadhaar in the programme. This implies introducing Aadhaar-based recognition of users in ration shops, which beneficiaries visit every month to obtain their entitlement from ration dealers (Masiero, Citation2015a). To do so beneficiaries need to enrol with Aadhaar, and their unique identification number is subsequently linked to the state-level FCI database assigning their entitlements. The FCI database is referred to as a ration card database, where a ration card is the paper-based document that lists all members of a household and its poverty status.

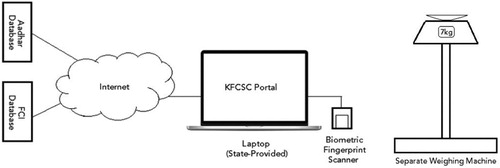

illustrates the functioning of the Aadhaar-based PDS in Karnataka. Each ration shop is equipped with a state-provided laptop, connected to a fingerprint scanner and to the KFCSC server which stores data from the Aadhaar and FCI databases. To collect their rations, users scan their fingerprint which reveals two sets of data: their identity as recognised by the Aadhaar system, and their entitlements as per the FCI database. Once recognition has taken place, the user is allotted their ration, accompanied by a receipt testifying the transaction. One element remaining from the paper-based system is the ration card, where a stamp is placed in correspondence of each monthly ration.

The accountability mechanism inscribed in the Aadhaar-based PDS is twofold, applying to both ration dealers and beneficiaries. On the one hand, as a senior official told us, the biometric system aims at combating the erroneous inclusion of non-poor citizens:

The old [paper-based] system was fraught with bogus ration cards, with which non-poor people could turn up at the ration shop and get subsidies just like the poor. With Aadhaar this is not possible, because biometric credentials are unique for each person.

There was a big problem of theft at the ration shop level, because there were no automated checks into place. So, the ration dealer could just pretend having finished their monthly stock, and then go sell it on the market […] we have implemented Aadhaar especially so that transactions have to go through the [POS] machine, and thus for all of them there is a digital record.

5. Findings

Our field data shed light on multiple views on the effects of Aadhaar on PDS entitlements. Such views can be grouped into two macro-clusters, each highlighting a different perspective on the programme and the datafying infrastructure within it. We first illustrate a techno-rational perspective, illuminating a view of Aadhaar as ‘problem solver’ in the PDS, and then contrast it with a socially embedded vision that highlights new forms of data injustice in the programme.

5.1. Techno-rational perspective: Aadhaar as problem-solver

Since the establishment of UIDAI in 2009, Aadhaar has been framed as a technology-enabled route to the inclusion of vulnerable Indians. Created under the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) coalition in power till 2014, Aadhaar has been brought forward by the current national government, under whose aegis it is framed as a technology ‘at the service’ of the poor (UIDAI, Citation2010). Reflecting such narrative, our interviews with ration shop staff reveal emphatisation of the positives of the biometric identification system. The main argument sustaining this view relates to the system’s ability to combat illegal diversion of goods, as explained by a ration dealer in Bangalore:

[In the Aadhaar-based PDS] there is no more way to cheat the system and go out to sell on the market. if even just one bag of rice disappears, for any reason in the current system, we will have to respond of that.

We [ration shop owners] are not allowed to register for fresh ration stocks from the regional godown, until the consignment for the current month has been completely disbursed. But since the quantity disbursed depends on [the number of] people who accessed the benefit through Aadhaar, the system does not allow ration shop owners to hoard rations illegally.

Every cardholder now gets their quantities of ration, which was not the case before. Ration dealers could claim stocks had finished and sell them independently, but they are now prevented from doing so. Because of the Aadhaar system, only actual cardholders can now buy from the PDS.

To be sure, narratives taking a techno-rational perspective do not deny the existence of problems in the new system. In line with the experience of other states (Yadav, Citation2016), our Karnataka fieldwork has revealed issues with biometric verification, especially for the elderly and users involved in the farming and construction industries. A probable cause is the deterioration of fingerprint quality due to age and activities requiring manual labour. Beneficiaries often face difficulties in accessing benefits due to the same, as a recipient at a ration shop in Kolar told us:

We have no other option. There is a corporation office nearby where we have to go. They send someone to do the verification. But that takes time and I have never used it. My family comes here with me, so even if I am not verified, someone will.

In addition, the current system allows one person to access benefits only from the ration shop they are registered with, based on proximity to the place of residence. As it emerged in our interviews with migrants, given the requirement for a local residential proof, people from other states of India (and in-state beneficiaries based outside their hometown) cannot collect rations from the place they moved to. They hence often have to travel long distances trading on job commitments, which is problematic especially for informal daily labourers whose time off leads to lose a day’s wage. This issue, already present in the old system, has persisted across the transition to a biometric PDS.

While recognising such problems, the perspective emerging from these narratives focuses on the positives of datafication, framed as a solid anti-leakage measure. This does not deny the existence of issues but leads to interpret them as ‘technical problems’ that will be overcome with the improvement of state-level infrastructures. As powerfully synthesised by a ration dealer interviewed in Bangalore, issues of this type are ‘the costs to bear’ in transition: problematic as they can be, they will be fixed as the Aadhaar-based system becomes the national standard.

5.2. Socially embedded perspective: new forms of data injustice

The accounts detailed above recognise computerisation as inherently good and rational. A different vision, relating technology to its specific context of implementation, emerges from more respondents’ narratives and observations conducted on the field. In information systems literature such a vision is referred to as ‘socially embedded’, as it considers technology in relation to the social context in which it operates (Avgerou, Citation2008). A socially embedded perspective is reflected in accounts that frame the Aadhaar-based PDS in relation to the lived reality of recipients (Chaudhuri & König, Citation2018), revealing issues in three domains – legal, design-related, and informational – of the newly implemented technology.

5.2.1. Legal domain: conditionality of PDS access to Aadhaar enrolment

As the PDS is currently designed, access to the programme is predicated on Aadhaar registration, which is a fundamental requirement to be eligible for social protection. This is also what we observed in the ration shops, where no alternative mechanism is available to the Aadhaar-based process. In the original idea of its founder, the former chairman of Infosys Nandan Nilekani, Aadhaar is characterised by being entirely optional and non-coercive (Nilekani & Shah, Citation2016). But enrolment is now mandatory for all those who want access to the PDS, as a ration shop worker highlights:

Users are given food [in ration shops] on the basis of the link between Aadhaar and the ration card. If the ration card has not been linked to Aadhaar, they have to go to computer centres to link it and then come back again. If a non-registered user asks me for a ration, I cannot give it even if I know them.

Scholars have argued that, making access to the PDS conditional to Aadhaar registration, the system subordinates people’s right to food to enrolment in a biometric database (Ramanathan, Citation2014). This leads users to ‘trade’ data for rations, exchanging biometric registration with access to a scheme that used to depend simply on poverty status. Significantly, many beneficiaries reacted with surprise to our question on how they felt towards Aadhaar registration: as several interviewees argued, any problem with ethics or privacy would just disappear in front of the need to obtain food under the scheme. As observed by a woman near a ration shop in Bangalore,

How would I not register? Now you need Aadhaar for all the schemes of the government. I am not really sure what happens with data treatment, if I can get ration, it’s ok.

5.2.2. Design-related domain: gaps with the reality of beneficiaries

The Aadhaar-based system is designed to reserve the programme for genuinely entitled recipients, where entitlement is proven by Aadhaar registration. But in multiple users’ perspectives, the system’s ability to reduce inclusion errors is greater than that of solving existing issues of wrongful exclusion. The system may have reduced ration dealers’ ability to trade on the market, but has not displayed potential to support users who are not recognised by point-of-sale machines, as a user explains:

My wife had gone to her in-law’s place and I was left with no option but to buy ration from out neighbour’s shop [meaning: regular non-subsidised ration] on credit. No matter how many times I try, the machine will not recognise me.

While not fully resolving exclusion issues, system design seems to perpetuate other problems, such as existing user dependency on ration dealers. Some beneficiaries voiced the suspicion that ration dealers still cheat on the rations sold, as a woman in a poor neighbourhood of Bangalore:

I often have the sensation that the ration dealer is tampering with our rations, selling fewer quantities of rice but claiming to have sold the whole ration. I cannot know for sure, because there is no way to know exactly how much rice has been sold at each transaction.

In addition, one issue that persisted from the pre-Aadhaar system is the uncertainty, displayed by many users, on the days and times of ration distribution. To be sure, in the rural Kolar district we witnessed regularities in opening times, revealed by billboards outside the ration shops and confirmed by the recipients we spoke to. Such regularities are however not present in the areas of Bangalore that we visited, where several interviewees display lack of awareness of the monthly opening times of the shop. We have experienced the same uncertainty in our visits to ration shops, often struggling to understand when these would be open: ration shops, several users reveal, open at the discretionality of the dealer, increasing users’ dependency and lack of monitoring mechanisms.

These cues point to a system that combats the inclusion error but is less effective in providing rations to those who are not recognised by point-of-sale machines.Footnote2 This points to a design-reality gap (Heeks, Citation2002) between the system and the real access problems from which users are affected. Even if built to correct wrongful inclusion, it still leaves exclusion errors and dependency on ration dealers, revealing limited capability to deal with the substantial issues experienced by users.

5.2.3. Informational domain: from PDS to cash transfers

Based on documentation produced by UIDAI and national economic surveys since 2014–2015, the design behind Aadhaar’s incorporation in the PDS stretches far beyond superficial streamlining. In the policy frame of the central government, Aadhaar is part of a ‘trinity’ that comprehends two more tools: a financial inclusion programme (the Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana) and mobile phones, whose ownership across India is rapidly increasing. The former, most commonly referred to as Jan Dhan Yojana, offers zero-balance bank accounts to low-income households, with a view of extending banking to the poorest of the poor. The mobile component seeks to delink finance from banks and post offices, enabling access to banking through basic mobile phones.

The system resulting from Jan Dhan Yojana, Aadhaar and mobile telephony is acronomysed as ‘JAM Trinity’ in government’s narrative and popularised as an anti-poverty tool (Government of India, Citation2015). Applied to social protection, it carries a particular goal: the JAM trinity does not seek to improve the subsidy system, but to replace it with a policy based on direct cash transfers to be delivered directly to beneficiaries’ bank accounts. As the ministry of finance reveals, such a system will bring substantial advantages with respect to the current leakage-burdened ration system:

[With cash transfers], by reducing the number of government departments involved in the distribution process, opportunities for leakage are curtailed (…) In addition to net fiscal savings, income transfers can compensate consumers and producers for exactly the welfare benefits they derive from price subsidies without distorting their incentives. (Government of India, Citation2015)

Amidst varying views on the effectiveness of such shift (Drèze & Khera, Citation2017; Saini et al., Citation2017), our data highlight an informational problem, relating to recipients’ awareness of the change underway. None of the beneficiaries’ we spoke to, including supporters of Aadhaar, displayed awareness of the prospected transition: in interviews, none related Aadhaar’s adoption to a move to cash transfers. But when asked whether they would prefer in-kind rations or an equal-value sum of cash to be credited on their accounts, beneficiaries unanimously declared a preference for the PDS as it currently is. As a woman in Kolar highlighted, reasons for this pertain to the secure materiality of rations:

No Sir, ration, any day. The men in the house are all alcoholics – they will drink it (cash) all away. At least if we get ration, we have something in the house to eat. We don’t need money.

Three forms of data injustice, summarised in , offer a nuanced response to our research question. The Aadhaar-based PDS is framed in governmental narrative through the techno-rational goal of reducing leakage in the programme. But when observed through its effects on the reality of beneficiaries, the same technology is found to participate in processes that undermine recipients’ ability to access entitlements as they did before. Datafication is built with rational purposes, but turns out to be intertwined with forms of injustice that are specific to datafied programmes.

Table 2. Forms of data injustice in the Aadhaar-based PDS.

6. Discussion

Our study of the Aadhaar-based PDS sheds light on the datafication of anti-poverty programmes, a domain of data governance on which limited knowledge is available. We find that on the one hand, Aadhaar’s datafying infrastructure is depicted as an optimal problem-solver, built to tackle the specific issues from which social protection schemes are affected. But through the lived reality of recipients, the same infrastructure is found to produce forms of injustice that pertain specifically to the datafied system. Covering legal, design-related and informational domains, such injustices problematise the techno-rational view of Aadhaar as an instrument for leakage minimisation.

Scholarship in critical data studies offers multiple problematisations of datafication processes. It suggests that notwithstanding an overwhelmingly positive vision of data governance in the Global South, biased towards ‘empowerment’ of the poor and needful (Arora, Citation2016), datafication contributes to shifting power equilibria with unpredicted and, in some cases, overtly negative effects on vulnerable groups (Eubanks, Citation2018; Taylor & Broeders, Citation2015). The uptake of data-based processes yields multiple consequences on economic governance, with mixed effects on subjects whose data are collected in a silent or coercive way (Mann, Citation2018; Taylor & Richter, Citation2017). Focusing on datafication of anti-poverty programmes, we seek to make three main contributions to such debate.

First, our study reflects a techno-rational view of datafying infrastructure as a tool for improvement, designed to tackle the particular problems that affect anti-poverty schemes. Incorporated in the PDS, Aadhaar is framed by providers as an effective means to monitor ration shop transactions, which prevents leakage by ensuring that goods are only sold to entitled beneficiaries. The techno-rational vision, promoted by the government, has been interiorised by numerous beneficiaries and increases consensus towards the ongoing adoption of Aadhaar in the public welfare system. Datafication, conceived as a technical fix to an existing problem, thus acquires an inherently political role, that of building an image of the government as skilled and effective problem-solver.

Second, empirics on the lived reality of PDS beneficiaries using Aadhaar lead to dispute the techno-rational vision. We find that the Aadhaar-based PDS subordinates the right to food to the enrolment of users, making subsidies conditional to biometric monitoring (Ramanathan, Citation2014). Furthermore, programme design is centred on detection of inclusion errors, more than on tackling the real access problems experienced by beneficiaries (Drèze & Khera, Citation2017). Finally, an informational asymmetry exists between the government and programme recipients, who are not made aware of the link between Aadhaar (and the JAM trinity of which it is a part) and the prospected shift to cash transfers. These aspects illustrate three new forms of data injustice, reinforcing the argument that the poor are exposed to specific injustices in a datafied world (Arora, Citation2016; Heeks & Renken, Citation2018).

Our third contribution pertains to theories of datafication in the Global South. In the Information Systems discipline a techno-rational perspective, where computerisation is framed as inherently capable of positive effects, is juxtaposed to a socially embedded vision, in which technology is considered within the social setting in which it participates. A techno-rational view is exemplified by governmental depictions of Aadhaar, whereas a more socially embedded one emerges in the problematisations of recipients, leading to the identification of multiple data injustices. But a socially embedded vision, identified here as relevant paradigm, may require greater elaboration when applied to datafied anti-poverty schemes.

The intentionality behind Aadhaar, as clearly put in the Indian government’s narrative, is not that of creating a superficial fix to the PDS. It is that of using the JAM trinity to turn the programme into a system of cash transfers, eliminating subsidy and economic distortion in favour of direct benefits that will enable the poor to buy commodities on the market (Saini et al., Citation2017). Such a move is deeply transformative and will affect the whole system rather than just the ‘last mile’ in which ration shop transactions happen (Prakash & Masiero, Citation2015). Cash transfer projects already in operation, such as that of Jharkhand, reveal a complete restructuring of the PDS supply chain, which eliminates ration dealers and shifts the locus of poverty reduction to the free market (Drèze et al., Citation2017).

As the case illustrates, it is not only a ‘social’ context that the technology is part of (Rao, Citation2013). The incorporation of Aadhaar in social protection is the incarnation of a precise political choice, that of substituting the PDS with a system that transfers governance to the market. There is a specific grand design behind this, motivated by explicit assertions sustaining greater effectiveness of direct benefits compared to in-kind subsidies (Government of India, Citation2015). In this scenario, technology is not simply ‘socially’ embedded, but purposefully inscribed in a political design with clear directions and consequences.

This leads us to augment the socially embedded view with a politically embedded vision, which considers datafication as an integral part of the policies that it puts forward. Such a vision frames datafied infrastructures as related to the political decisions behind them, which illuminates the dynamics of economic governance (Mann, Citation2018) that such infrastructures advance. This reveals a particular form of embeddedness, where the ‘social’ context is substantiated in the ‘political’ agendas that inform the making of datafication. Conceived as such, a politically embedded view sheds light on the dependencies (Heeks & Renken, Citation2018) that the poor experience in a datafied world.

Viewing data as politically embedded has multiple implications for the emerging study of datafication in the Global South (Milan & Treré, Citation2017), of which our research provides some instantiations. One such instantiation pertains to the dichotomy between ‘beneficiaries’ and ‘consumers’ at the base of the pyramid (Arora, Citation2016): converting the PDS into a cash transfer scheme implies turning the ‘beneficiary’ of anti-poverty programmes into a ‘consumer’ of freely available goods on the market. As observed elsewhere, this will substantially alter the state-market balance in anti-poverty systems (Drèze & Khera, Citation2017), a move which the Government hails as removal of ‘market distortion’ induced by subsidies (Government of India, Citation2015). While it may result in dismantling the current, ration-based food security system, the move may take different shapes at the state level, with some state governments using Aadhaar to streamline the PDS in its current formulation (Masiero, Citation2015b).

In addition, there is scope for linking the anti-poverty discourse to that of anti-corruption measures, often associated to computerisation of the public sector in the Global South (Gonzalez-Zapata & Heeks, Citation2015). On the one hand, it is true that enforcing the Indian government’s policy on the universal right to food requires anti-corruption efforts: corrupt programmes are subjected to leakage of resources, which in the PDS case diverts food rations away from beneficiaries. Governmental narratives frame the prospected transition to cash transfers as an anti-corruption measure, as it sets to transform a system characterised by multiple incentives to diversion. It remains, however, to be seen whether a cash transfer system may be the solution, or whether it may generate other forms of incentives to diversion as some commentators suggest (Drèze et al., Citation2017; Ramanathan, Citation2014). As noted elsewhere, preserving the PDS at the state level is an alternative to radical transformation, which can also be pursued through digital technologies (Masiero, Citation2017).

Finally, the literature on datafication in the Global South relates new biometric systems to previous forms of surveying, experienced by poor and vulnerable communities since the colonial era (Arora, Citation2016; Couldry & Mejias, Citation2018). Studying a large biometric infrastructure, our research sheds some light on the relation between ‘old’ and ‘new’ forms of surveying: on the one hand, there is clear continuity between Aadhaar and old technologies of rule such as the Census of India, aimed at mapping the population to increase its amenability to control (Scott, Citation1998). At the same time, datafied technologies such as the Aadhaar-seeded PDS go one step further, by automatically linking the poverty status of residents to their biometric and demographic details. This automatic link tightly couples the identity of the resident with its attributions in terms of income, gender, caste and other forms of classification, thus providing the state with detailed profiles of its residents/beneficiaries. Further research on the topic may link this to theorisations of data colonialism, which combines extant practices of coloniality with the quantification methods of computing (Couldry & Mejias, Citation2018).

7. Conclusion

This paper has observed datafication through the lens of its significance for anti-poverty programmes. Drawing on the case of India’s Aadhaar, it has illustrated a techno-rational depiction of datafication as problem-solver within existing social protection schemes. We have then examined a field-based counternarrative that reveals three forms of data injustice, stemming from the adoption of datafied infrastructures. On this basis we have introduced a politically embedded view, advancing a framing of datafication as a force that contributes to deep reform of existing schemes. This puts datafied anti-poverty schemes in relation to the political design behind them and may inspire further research on the implications of datafication for the entitlements of beneficiaries in social protection.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Silvia Masiero is Lecturer in International Development at the School of Business and Economics, Loughborough University. Her research concerns the role of ICTs in socio-economic development, with a focus on the participation of ICT artefacts in the politics of anti-poverty programmes and emergency management. She has conducted extensive work on the computerisation of India's main food security programme, the Public Distribution System (PDS), and on the adoption of ICTs in core aspects of the Indian public sphere including elections, rural employment guarantees, and programmes of social protection. She is a fellow of the Higher Education Academy (HEA), a member of the Association for Information Systems (AIS), and a member of the UNESCO Chair in ICT4D.

Soumyo Das is currently a MS by Research scholar at IIIT Bangalore, where his study focuses broadly on the domain of technology and organisations. He researches on how digital technologies influence organisational dynamics and is interested in critical approaches to digitisation in the context of development. Soumyo has an undergraduate degree in the applied sciences and was formerly employed with the Tata Group.

Notes

1 Criticism has been raised on the choice of passing the act as a Money Bill, which only requires approval from the Lok Sabha (Lower House of Parliament) and bypasses the decision of the Upper House.

2 Even though the system’s ability to fight inclusion errors is defended by the authorities, during fieldwork we have come across two instances of people from privileged backgrounds standing in line at ration shops. This corroborates Swaminathan’s (Citation2002) argument that a core problem lies in how APL/BPL status is determined.

References

- Arora, P. (2016). Bottom of the data pyramid: Big data and the Global South. International Journal of Communication, 10, 1681–1699.

- Avgerou, C. (2008). Information systems in developing countries: A critical research review. Journal of Information Technology, 23(3), 133–146. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.jit.2000136

- Chaudhuri, B., & König, L. (2018). The Aadhaar scheme: a cornerstone of a new citizenship regime in India? Contemporary South Asia, 26(2), 127–142. doi: 10.1080/09584935.2017.1369934

- Couldry, N., & Mejias, U. A. (2018). Data colonialism: Rethinking big data’s relation to the contemporary subject. Television & New Media, 1–14.

- Cukier, K., & Mayer-Schoenberger, V. (2013). The rise of big data: How it's changing the way we think about the world. Foreign Affairs, 92, 28–36.

- Devereux, S. (2016). Is targeting ethical? Global Social Policy: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Public Policy and Social Development, 16(2), 166–181. doi: 10.1177/1468018116643849

- Devereux, S., & Sabates-Wheeler, R. (2004). Transformative social protection. Working paper series, 232. Brighton: IDS.

- Devereux, S., & Vincent, K. (2010). Using technology to deliver social protection: Exploring opportunities and risks. Development in Practice, 20(3), 367–379. doi: 10.1080/09614521003709940

- Drèze, J., Khalid, N., Khera, R., & Somanchi, A. (2017). Aadhaar and food security in Jharkhand. Economic & Political Weekly, 52(50), 50–60.

- Drèze, J., & Khera, R. (2017). Recent social security initiatives in India. World Development, 98, 555–572. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.05.035

- Eubanks, V. (2018). Automating inequality: How high-tech tools profile, police, and punish the poor. New York, NY: St. Martin's Press.

- Gonzalez-Zapata, F., & Heeks, R. (2015). The multiple meanings of open government data: Understanding different stakeholders and their perspectives. Government Information Quarterly, 32(4), 441–452. doi: 10.1016/j.giq.2015.09.001

- Government of India. (2015). Wiping every tear from every eye: The JAM trinity number solution. Economic survey 2015–2016. New Delhi: Government of India. http://indiabudget.nic.in/es2014-15/echapvol1-03.pdf

- Hacking, I. (1986). Making up people. In Reconstructing individualism: Autonomy, individuality, and the self in western thought (pp. 161–171). Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Heeks, R. (2002). Information systems and developing countries: Failure, success, and local improvisations. The Information Society, 18(2), 101–112. doi: 10.1080/01972240290075039

- Heeks, R., & Renken, J. (2018). Data justice for development: What would it mean? Information Development, 34(1), 90–102. doi: 10.1177/0266666916678282

- Jerven, M. (2013). Poor numbers: How we are misled by African development statistics and what to do about it. New York, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Joshi, A., & Moore, M. (2000). The mobilising potential of anti-poverty programmes. Discussion paper series, 374. Brighton: IDS.

- Khera, R. (2011). Trends in diversion of grain from the public distribution system. Economic & Political Weekly, 46, 106–114.

- Mann, L. (2018). Left to other peoples’ devices? A political economy perspective on the big data revolution in development. Development and Change, 49(1), 3–36. doi: 10.1111/dech.12347

- Masiero, S. (2015a). Redesigning the Indian food security system through e-governance: The case of Kerala. World Development, 67, 126–137. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.10.014

- Masiero, S. (2015b). Will the JAM trinity dismantle the PDS? Economic & Political Weekly, 50(45), 21–23.

- Masiero, S. (2017). Digital governance and the reconstruction of the Indian anti-poverty system. Oxford Development Studies, 45(4), 393–408. doi: 10.1080/13600818.2016.1258050

- Masiero, S., & Prakash, A. (2015, May 11-14). The politics of anti-poverty artefacts: Lessons from the computerization of the food security system in Karnataka. 7th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies and Development, Singapore.

- Milan, S., & Treré, E. (2017). Big Data from the South: The Beginning of a Conversation We Must Have. Retrieved from SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3056958

- Muralidharan, K., Niehaus, P., & Sukhtankar, S. (2016). Building state capacity: Evidence from biometric smartcards in India. American Economic Review, 106(10), 2895–2929. doi: 10.1257/aer.20141346

- Nilekani, N., & Shah, V. (2016). Rebooting India: Realizing a billion aspirations. London: Penguin.

- Prakash, A., & Masiero, S. (2015). Does computerization reduce pds leakage? Economic & Political Weekly, 50(50), 77–81.

- Ramanathan, U. (2014). Biometrics use for social protection programmes in India violating human rights of the poor. Geneva: United Nations Research Institute for Social Development. Retrieved from http://www.unrisd.org/sp-hr-ramanathan

- Rao, U. (2013). Biometric marginality: UID and the shaping of homeless identities in the city. Economic & Political Weekly, 48(13), 72–77.

- Riessman, C. K. (2008). Narrative methods for the human sciences. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Saini, S., Sharma, S., Gulati, A., Hussain, S., & von Braun, J. (2017). Indian food and welfare schemes: Scope for digitization towards cash transfers. ZEF-Discussion Papers on Development Policy No. 241, Bonn, Germany.

- Scott, J. C. (1998). Seeing like a state: How certain schemes to improve the human condition have failed. New York, NY: Yale University Press.

- Swaminathan, M. (2002). Excluding the needy: The public provisioning of food in India. Social Scientist, 30, 34–58. doi: 10.2307/3518075

- Taylor, L. (2017). What is data justice? The case for connecting digital rights and freedoms globally. Big Data & Society, 4(2), 1–14. doi: 10.1177/2053951717736335

- Taylor, L., & Broeders, D. (2015). In the name of development: Power, profit and the datafication of the Global South. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 64, 229–237.

- Taylor, L., Floridi, L., & Van der Sloot, B. (Eds.). (2016). Group privacy: New challenges of data technologies. London: Springer.

- Taylor, L., & Richter, C. (2017). The power of smart solutions: Knowledge, citizenship, and the datafication of Bangalore’s Water supply. Television & New Media, 18(8), 721–733. doi: 10.1177/1527476417690028

- UIDAI. (2010). Envisioning a role for Aadhar in the public distribution system. Retrieved from http://www.prsindia.org/uploads/media/UID/Circulated_Aadhaar_PDS_Note.pdf

- Yadav, A. (2016). In Rajasthan, there is “unrest at the ration shop” because of error-ridden Aadhaar. Retrieved from https://scroll.in/article/805909/in-rajasthan-there-is-unrest-at-the-ration-shop-because-of-error-ridden-aadhaar