ABSTRACT

Despite recent efforts to establish a European Digital Single Market (DSM), access to audio-visual (AV) works through on-demand service providers, such as Netflix and Amazon Prime, continues to be restricted across jurisdictions to the detriment of consumers through geo-blocking measures. This paper introduces a proposal for a central clearing house for AV rights which facilitates the cross-border provision of AV services and thereby contributes to the creation of the DSM. To ensure that the adoption of the proposal enhances the efficiency of the market, we assess whether it meets specific criteria that pertain to market design and the functioning of the market for AV works.

Introduction

As of 2014, approximately 14 million EU citizens lived in a Member State other than their country of origin (Simonelli, Citation2016, p. 18). In 2012, another 4 million from linguistic minorities had an adequate level of proficiency in another EU language while between 90 and 220 million could speak a language other than their mother tongue (ibid). Additionally, with broadband internet access and technological advances such as mobile smart devices which have provoked the daily use of the internet (Sherman & Waterman, Citation2016, p. 458), the number of people accessing audio-visual (AV) services online has grown rapidly since 2010 (Grece, Lange, Schneeberger, & Valais, Citation2015, p. 26). By 2020, 59 million households, 20% of the European pay-TV market, are expected to have a subscription to such a service. However, prevailing barriers continue to prevent consumers from accessing these services in a different language across Member States (ibid), thus undermining the potential of the internet to eliminate international barriers and limiting cultural diversity which would benefit consumers (Maciejewski, Fischer, & Roginska, Citation2014, p. 22). These obstacles stem from exclusive territorial licenses and geo-blocking measures based on consumers’ geographic locationFootnote1 (Mazziotti, Citation2015, p. 1).

The system of exclusive territorial licenses is largely supported by copyright law which allows right holders to exploit their rights by imposing restrictions on the licensee regarding, inter alia, territory, use and technology (Meurer, Citation2002, p. 1872). In the absence of copyright law, the right holder's incentive to invest in new content could be weakened as the rent from new works cannot be entirely be extracted (Wunsch-Vincent, Citation2016, p. 2). Hitherto, content licenses in the EU are granted per country and are mostly territorial. Copyrights are still enforced under national laws, as only parts of the copyright system have been harmonised under EU law (Mazziotti, Citation2015, p. 3). Consequently, an AV service provider (‘provider’) who wants to offer content across the EU needs to acquire rights in each Member State and abide by national copyright laws which restricts the internal market (Hoffman, Citation2016, p. 144).

In response to changing consumer demand, the European Commission launched the Digital Single Market (DSM) strategy in 2015 which aims at removing the predominant barriers to improve online access for consumers and businesses across Europe (European Commission, Citation2015, p. 3). The Commission stressed that with the launch of the DSM unjustified discrimination against consumers would disappear. However, there is still some way to go as the Geo-blocking and Portability Regulations, as well as the Copyright Proposal insufficiently addressed geo-blocking measures and deficient consumer access to AV works (Schroff & Street, Citation2018, p. 1305; Proposal 2016/0280; Regulations (EU) 2017/1128 and 2018/302).

Besides reviewing the literature to explain the problem, the objective of this paper is to explore and discuss a policy proposal which enables cross-border accessibility of AV works without banning exclusive territoriality. We propose to establish a clearing house, i.e., an intermediary that facilitates exchange between two parties, for AV rights, serving providers in different Member States. This proposal aims at allowing EU citizens living in a Member State other than their country of origin, as well as citizens with adequate proficiency in another EU language, to access the full range of content.Footnote2 As further changes in the regulatory environment, in particular the copyright system, can be expected in time, such a set-up constitutes a timely solution for the increased demand to access content beyond one's own territory. The proposal complements the Commission's initiatives supporting the DSM.

A clearing house for AV rights is in line with previous research acknowledging the contribution of the territorial licensing system to the prevailing barriers to cross-border accessibility of AV works. Although a clearing house is novel in the market for AV works, it has proven to be effective in various industries such as the market for over-the-counter (OTC) derivatives, patent pools, and life sciences. Arguably, one could opt for a solution relying on competition between collective management organisations (CMOs or collecting societies) that collect and distribute authors’ royalties as applied in the music industry which shares some characteristics of the AV market (Schroff & Street, Citation2018, p. 1306). Such a solution has, however, been deemed to be ineffective and has the potential to threaten cultural diversity (ibid).

To put our proposal in perspective and assess its viability, we discuss to what extent it satisfies conditions and concepts related to market design, and criteria that pertain to the market for AV works. The most important condition that we identify is to find an appropriate way of regulating prices of the add-on services for accessing cross-border content.

Literature review

The market for on-demand AV works

We start with an overview of the on-demand AV market where the key players are the right holder (wholesaler) who typically produce the content for which they own all rights, and digital content providers (retailer) who bundle licensed content, typically from multiple copyright owners, into a single channel like a website, app, or platform (European Commission, Citation2015, p. 5; Sherman & Waterman, Citation2016, p. 465). Copyright law confers exclusive rights to content producers allowing them to ‘control their work, its accessibility, pricing, modification and other elements’ (Wunsch-Vincent, Citation2016, p. 2). A right holder can commercially exploit rights by assigning them to a third party or by licensing them (Jones & Sufrin, Citation2016, p. 833). When rights are licensed, the right holder permits the licensee to exploit the respective right, and therefore remains in control of the use.

Without copyright law, incentives to create content would be hampered, particularly when creative work is sold at marginal costs or can be easily copied without any remuneration for the creator. Therefore, the supply of creative works would fall below a socially desirable level. Copyrights have been established to, inter alia, address this market failure by rewarding creativity with temporary monopoly profits (Wunsch-Vincent, Citation2016, p. 2). Generally, copyright law is a regulatory tool that transfers specified rights to creators and prohibits the drafting of certain contracts or exercise of practices (Meurer, Citation2002, p. 1872). It further permits right holders to impose commercial requirements to the licensee such as territorial, technology and usage restrictions (ibid, p. 1880). The exclusive rights granted by copyright law are based on the principle of exclusive territoriality which allows the licensee to fully exploit the licensed rights as right holders commit to refrain from exploiting their rights themselves or to license them to other parties (Jones & Sufrin, Citation2016, p. 834f). To offer services containing AV works, content providers must obtain a license from the right holder on a per country basis (Chalaby, Citation2016, p. 48). A company who wants to operate on a pan-European level needs to obtain the rights in all 28 Member States which is, however, associated with high costs (Hoffman, Citation2016, p. 149).

Limitations to cross-border accessibility of AV works

Hitherto, European consumers have been prevented from accessing AV works across borders although the demand has risen. Several scholars assessed possible causes for the prevailing barriers. Hoffman (Citation2016) holds the fragmented copyright law within the EU and the territoriality of copyrights responsible (p. 144f). She identifies technical measures like geo-blocking, which enable discrimination based on viewers’ geographical location as factors that keep national borders in place. She calls for abandoning the territorial copyright system and taking a stronger stance against geo-blocking (p. 172f). Earle (Citation2016) also emphasises the rising expectations of consumers to access content across borders and acknowledges the need to adjust the law (pp. 1, 16).Footnote3 Ibáñez Colomo (Citation2017) stresses that the DSM objectives can only be realised by harmonising copyright law, as competition law alone cannot achieve this (p. 16).

Langus, Neven, and Poukens (Citation2014) focus on the motives behind a territorial licensing system and assess whether a limitation of these practices would benefit social welfare (p. 1). They provide an overview of features of the AV industry such as the value and licensing chain, financing, and rights clearance. They acknowledge that content rights are typically exploited on a territory-by-territory basis and that pan-EU licenses rarely exist (p. 44f). The authors further find that regulatory changes limiting or banning territorial licenses may not bring about the desired effects on social welfare (p. 118), which will be further discussed below.

Policy proposals for enabling cross-border accessibility of AV works

Langus et al. (Citation2014) argue that changes in the policy framework for copyright protected AV works may not only enable cross-border exploitation but can also positively impact social welfare and transaction costs if well designed (p. 104f). They compare four policy proposals to the status quo which follows the ‘country of reception’ principle, whereby rights must be cleared for the receiving country and restrictions can be imposed by contracting parties (p. 4).

Proposal 1 is a ‘targeting approach’ requiring AV service providers to obtain rights for each country in which they target viewers (excluding territories in which users have access to content without belonging to the target group). Technical measures to prevent passive sales are not allowed. As citizens abroad can be served, social value would be increased (p. 105f). The other proposals pursue the ‘country of origin’ principle whereby rights only need to be cleared in the Member State where the content provider is established (p. 5). Proposal 2 considers the country of origin principle in combination with freedom of contract whereby parties to an agreement can contractually impose restrictions on each other to limit passive sales (e.g., geo-blocking). This approach preserves the system of territorial licences for AV works and limits the pan-EU exploitation of rights. In Proposal 3, the licensor is prohibited from imposing geographical restriction on the licensee which bans territorial licenses and paves the way for pan-EU licenses. Proposal 4 considers a scenario under which licensor and licensee cannot impose geographical restrictions, i.e., the licensee cannot discriminate based on viewers’ geographical location (p. 107f). The authors conclude that none of these proposals significantly benefits end-users and warrants a departure from the status quo.

Mazziotti (Citation2015) questions whether geo-blocking is the sole source for limited access to AV works across the EU (p. 14). He looks at justifications for territorial licenses and finds that technical restrictions appear necessary in an industry dominated by territorial licenses. Mazziotti proposes five policy options for cross-border access without impairing the territorial exploitation of content rights, of which the following two are the most promising. Under the ‘soft law initiative’ proposal, the European Commission issues guidance on the transposition of existing EU laws such as the interaction between copyright and competition law (acknowledging that the latter may challenge the usage but not the existence of copyrights). Such an initiative would be necessary since non-legislative initiatives have proven to be ineffective. One example is the European Commission's recommendation on collective cross-border management of copyright and related rights for online music services (ibid; European Commission, Citation2005). The ‘new legislative measure’ proposal follows the logic of the Block Exemption Regulation for vertical agreements under Article 101(3) of the Treaty of the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) (Regulation (EU) No 330/2010). It sets out the circumstances under which territorial restrictions would be considered compatible with the internal market objective and the logic of the DSM. Thus, a system of pan-EU or multi-territorial licenses may be within reach (p. 15) but would need further elaboration.

Poiares Maduro, Monti, and Coelho (Citation2017) review the Geo-Blocking Regulation Proposal and argue that to deal with the Regulation's failure to address AV copyrighted content, a long-term comprehensive solution asks for EU wide copyright law. However, they judge that such a reform is unlikely to prevail soon and suggest an alternative in accordance with existing case law (p. 29f). They propose an obligation to provide cross-border access to content for which requisite rights have been granted by the respective right holder in more than one territory. Under these circumstances, copyright is not limited to one territory and therefore the provider's customers should be able to access services in the served territories. The burden of proof would lie with the trader who needs to inform users when legal restraints from offering cross-border service exist, i.e., no license has been obtained. This proposal does not specifically address content inaccessibility as it primarily emphasises the need to expand the Geo-Blocking Proposal to comprise AV services not legally bound to one territory.

CMOs – an alternative solution?

CMOs may provide an alternative solution. Schroff and Street (Citation2018) address geo-blocking in the music industry in the EU and zero in on the regulatory framework and its contribution to the DSM. They explore the role of CMOs which have been subject to reforms to address geographical copyright barriers.Footnote4 Their discussion about collection and distribution of music rights and its connection to the DSM parallels our exploration of AV rights.Footnote5 According to the authors, the CMO Directive has serious shortcomings, stemming from, amongst others, the reliance on competition as copyright owners must be free to choose a CMO (Directive 2014/26/EU). The underlying driver is efficiency, and not, for instance, cultural diversity, as competition is assumed to solve problems related to cross-border licensing. However, they argue that this set-up based on rational self-interest fails to capture collective components like social and cultural funds, or the interests of authors less actively pursuing commercial goals. Our paper focuses on AV rights and, more generally, proposes a solution that does not rely on competition by CMOs, hence avoiding problems that prevail in the music industry as identified by Schroff and Street.

Proposal for a central clearing house for cross-border accessibility of AV works

Objective and motivation

The primary objective of the proposal is to enable cross-border access of AV works through a central clearing house which coordinates AV rights across the internal market. This proposal is, to the best of our knowledge, the first one addressing the problem of cross-border accessibility while leaving room for future copyright alterations.

Clearing houses have already contributed to the better functioning of markets which share characteristics with the AV industry, such as high transaction costs, market thickness, and the presence of (vertical) territorial restraints. For example, in the market for OTC derivatives contracts (Pirrong, Citation2011), regulators introduced central clearing counterparties for interbank transactions as part of the Market Infrastructure Regulation (Regulation (EU) No 648/2012). Van Overwalle (Citation2016) examines clearing houses for life sciences patents, serving as mechanisms ‘[…] by which providers and users of goods, services, and/or information are matched’ (p. 12). The author identified four types of clearing houses: for information, technology exchange, standardised licenses and royalty collection. The latter two are relevant in the context of AV works. Under these two concepts, a clearing house either provides access to standardised licenses through a portal which generates customised agreementsFootnote6 or collects license fees for patent holders (p. 13f).

As highlighted, there are various rationales for maintaining territorial exclusivity in the AV market which may render current intentions to ban or restrict territorial exclusivity by limiting geo-blocking less attractive.Footnote7 However, the system has drawbacks such as high transaction costs.Footnote8 We therefore consider a proposal which enables consumers to access content across borders while increasing transparency of licensing agreements. Although the European Commission has acknowledged the need to align national copyright systems to enable legal cross-border transmission of AV works by providers, such a change is unlikely to occur in the near future.Footnote9 This has been confirmed by the lack of materiality of the recent legislative reforms. Our proposal allows for maintaining national copyright laws while aiming for cross-border accessibility of AV works.

Components and scope

To set up a clearing house, the characteristics of the AV market calls for two types of agencies:

an EU agency which we label as the European Clearing House for AV Rights (ECHAR), and

national agencies called National Clearing Houses for AV Rights (NCHARs).

This system ensures that, even though underlying ownership patterns (e.g., who is the author and receives remuneration) will vary, providers and right holders face uniform conditions (regarding the market conditions prevailing in the country of the providing servicer) across the European market and therefore supports a level playing field. Moreover, the dominance of providers operating solely in a single Member State requires national agencies who have the knowledge of the national market.

These institutions will be entrusted with the facilitation and coordination of transactions by ‘pooling’ AV rights granted to providers by right holders through licensing agreements. Thus, the proposal affects both providers and right holders and concerns licensing agreements concluded between these parties. For the purpose of this proposal, providers are defined as any business offering online services whereby copyright protected work is provided to subscribers against remuneration. Therefore, this proposal particularly concerns on-demand pay-to-view services, i.e., Transactional Video-on Demand and Subscription Video-on Demand services. Free services are outside the scope of this proposal as they tend to be based on different business models, e.g., based on advertising. These free on-demand AV services include catch-up services which are provided by public broadcasters and platforms offering user-generated content. The latter are typically accessible on a global basis while the former is typically subject to national legislation and state intervention from which we abstract.Footnote10 Moreover, as catch-up services can generally be accessed (temporarily) without paying an additional fee, a remuneration of the right holder is not always possible.

The proposed regulation may equally apply to existing agreements and therein acquired rights. It aims at improving the functioning of the internal market and increasing transparency of licensing agreements. The latter will support the European Commission and national competition authorities with investigations into restrictive clauses. With a uniform approach which maintains the current protection for right holders and preserves economic benefits from the current system, the proposal promotes free movement of services across the EU. It will limit unauthorised access to content via illegal streaming or downloading platforms as a large share of their users is actually willing to pay if content would be available in their jurisdiction (Earle, Citation2016, p. 12).

The proposal is consistent with initiatives published by the European Commission under the DSM aegis. It serves the Single Market objective and complements the Audio-Visual Media Services Directive (Directive 2010/13/EU) as it aims at improving the cross-border reach of AV services. The legal basis for the proposal (and other initiatives supporting the DSM) can be found in Article 114 TFEU as it enhances the freedom to provide and receive services, promotes the free movement of services, and supports ‘the establishment and functioning of the internal market’. Furthermore, the provisions in the proposal are proportionate in terms of achieving its objective as it preserves territorial licenses, the removal of which, as part of a substantial copyright reform, would have a substantial impact on market participants. Also, just like clearing houses in other sectors, it is a targeted mechanism aiming at the specific purpose of cross-border access. Comparatively, the obligations introduced in this proposal do not go beyond what is necessary to remove prevailing barriers in light of the significant impact of the current practices on the online dissemination of AV works across Europe. Overall, it should be feasible to regulate the clearing houses’ exercise of powers and range of actions in keeping with their goal. As a regulation is binding in its entirety for all Member States at the time it enters into force, it effectively ensures a uniform application of the rules of this proposal, provided that it includes an obligation for AV service providers to comply.Footnote11

Clearing mechanism

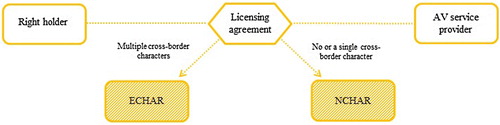

The central idea is to enable European consumers to access content regardless of their geographic location (within the EU). For cross-border provisionFootnote12 of AV rights, transactions concluded between providers and right holders must be reported to the responsible authority, which is either the ECHAR or an NCHAR where the jurisdiction depends on the licensing agreements’ characteristics. Agreements may fall into one of two categories (see ):

Licensing agreements with either no or a single cross border character. These need to be reported to the NCHAR of the country where the provider is established. Agreements fall in this category when they are concluded between two parties established in the same Member State (nationally) or when one of the parties is established in another Member State (cross-border).

Licensing agreements with multiple-cross border characters. Such contracts shall be reported to the ECHAR and are defined as licenses granted for more than one territory, including pan-EU licenses .

Hence providers must offer customers the possibility to add additional features to their general subscription, such as access to national content catalogues, for which a fee can be charged. The payment scheme must be proportionate and thus not go beyond what is necessary for the additional service. Some regulatory oversight will be necessary which we expect to be light-handed relative to, for instance, the regulation of access prices in sectors such as telecommunications. Basically, there should be a fair compensation that does not invite providers to react strategically, e.g., to benefit from ‘regulatory arbitrage’, which could result in inefficient market outcomes.Footnote13 An additional payment is required for two reasons. Firstly, it ensures an adequate remuneration for right holders whose content has been made available for customers of the provider lacking a licensing agreement. Without a remuneration mechanism, the incentives to undertake investments in content could be reduced. Secondly, the ‘providing provider’ needs to install server capacity to satisfy additional requests. These investments must be economically viable. Moreover, the additional services should be offered on a monthly basis requiring active renewal. Thereby, the concerned rights can remain covered by the original licensing agreement(s). Furthermore, according to a survey for the European Commission, 34% of EU citizens living abroad are willing to pay a monthly fee of EUR 10 or more to access AV works from their home country (Plum Consulting, Citation2012, p. 8).

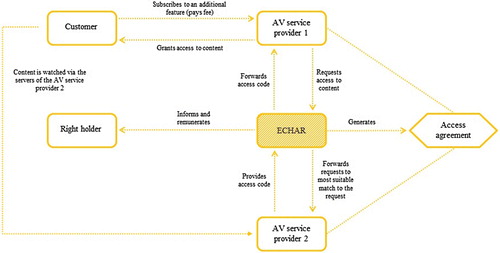

The transaction process works as follows (see ): to provide its users with content for which no rights were acquired, the provider sends a request to the ECHAR who acts as intermediary between AV service providers in the EU. Since all licensing agreements must be reported, the ECHAR can identify the providers to whom the requested rights have been granted through a licensing agreement with the right holder. Therefore, the ECHAR can match the requesting party with the providing party using a matching and due diligence mechanism for confirmation.Footnote14 Afterwards, the initial request is forwarded to the ‘providing provider’ who passes on an access code to the ECHAR which the requesting provider can use to unlock the service for the user. By using the ECHAR as an intermediary, market parties enter a direct contractual relationship. This limits risks from contracting and the opportunities for collusion and market foreclosure. The ECHAR, moreover, generates standardised agreements between the parties with a predefined maturity.

Without a central clearing house, exchanges across the EU are unlikely to occur due to the high transaction costs associated with a large number of bilateral agreements. The variety of providers in different Member States complicates the identification of right holders of the required content which increases search costs. As enabling cross-border accessibility of AV works depends on such agreements, a legal obligation for providers to find a suitable party for user requests is needed, despite the substantial costs to do so. In an unregulated environment, this obstacle would render the achievement of such contracts economically unviable and would impose an economic burden on market players. Consequently, a central clearing house is a precondition for the achievement of the objective as it significantly decreases transaction costs.

Moreover, ongoing information exchange between the NCHARs and the ECHAR is envisaged. The ECHAR will be informed about every licensing agreement reported to NCHARs to be able to fulfil its task as a facilitator of on-demand cross-border provision of content. The ECHAR in turn informs the NCHARs about relevant multi-territory licensing agreements. Moreover, since all clearing houses have insight into the terms on which the content rights are granted to providers, they can monitor for clauses that may harm competition and consumer welfare, and report to competition authorities if necessary.

Evaluation

As the adoption of a new economic governance should not leave a market worse off, we use the conceptual framework for market design by Gans and Stern (Citation2010) to assess the economic efficiency of our proposal. Their approach integrates three principles for a well-functioning market identified by Roth (Citation2007), namely market thickness, market safety and lack of congestion. Market thickness is the existence of numerous buyers and traders which facilitates an appropriate mutually satisfactory exchange between these parties. Hence, this criterion refers to allocative efficiency stimulated by more and better matching opportunities. Market safety exists when market participants have incentives to disclose confidential information and act on it. This condition increases trust and reduces the barrier to become active in the market and leads to more interactions. A lack of congestion, which is also required for allocative efficiency, can be achieved by freeing up market participants’ time or means when making the decision to conduct a transaction with several alternatives being available.

Gans and Stern note that thick and uncongested markets allow for consistent, transparent, and stable prices and transactions (p. 10), and add additional characteristics relevant for markets where intangible goods, in particular ideas and technology, are traded. Since AV content has different characteristics, we adjust, where necessary, the proposed concepts, specifically idea complementarity and user reproducibility (p. 815ff). Idea complementarity implies that ideas need to be complemented with other ideas and assets to be most valuable. While this notion seems to have limited relevance for AV content, the bundling of similar types of content, nevertheless, generates value for consumers as it increases variety. One may also think of complementarity between content and devices: a clearance system would facilitate access to content on various types of screens.

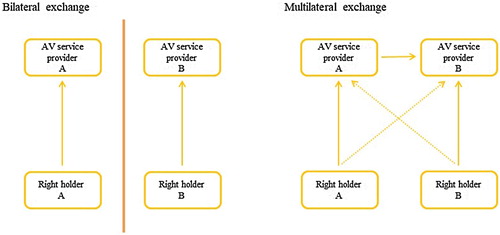

User reproducibility refers to the replication of ideas at a low cost by potential buyers. For copyrighted content, unlimited and costless copying and redistribution may not be desirable as it could impede the seller's ability to fully appropriate the value of his idea. Hence, to safeguard a producer's incentives to invest in content, a balance must be obtained. The authors further found that a shift from a bilateral towards a multilateral exchange mechanism (see ), like in our proposal, enhances efficiency, decreases inefficiencies and limits the scope for strategic bargaining (ibid, p. 811).

As we will discuss below, the clearing house must be able to deal with copyright exemptions. Langus, Neven, and Shier (Citation2013) provide a corresponding framework which helps to identify relevant factors in the decision-making process regarding exemption approvals (p. 71ff). They firstly consider whether transaction costs forestall mutually beneficial trade. Secondly, they assess whether missing markets exist and if so whether they are likely to be served by innovative market solutions in the future. Thirdly, the authors look at market power and the impact of the exemption on market players’ incentives. Finally, they examine the effect of the exemption on transformative (new) services (ibid).

In the following, the criteria and framework presented above will be used to assess the effectiveness of a central clearing house for AV rights.

Figure 3. Enabling multilateral exchange based on Gans and Stern (Citation2010).

A central clearing mechanism for AV rights across the EU enhances the thickness of the European market as it increases exchange opportunities through transactions between providers operating in different markets to take place which were not practicable before. For the ECHAR to be able to efficiently match AV service providers in need of rights to a content provider who has been granted these rights, a thick market is a necessary condition. Since all licensing agreements affecting the European market need to be reported to either the competent NCHAR or the ECHAR, market thickness and, thus, an effective matching mechanism for facilitating and coordinating transactions, is guaranteed.

As agreements are likely to be written in national languages and are based on national copyright laws, they need to be translated into English. This may especially impose a burden on small content owners or providers which may require the introduction of a common standard for agreements. Such a set-up, for example, already exists for the clearing and settlement of OTC derivatives where clearing houses require the submission of relevant documentationFootnote15 in English. This is enabled through a common standard – the so-called Master Agreement – developed by the International Swaps and Derivatives Association. This standardised agreement serves as a basis for other agreements to be concluded under national laws by allowing for modifications to address differences in the applicable law. A similar solution could, thus, be adopted for the clearing of AV works under the proposed framework.

The new system enhances market safety as it requires providers and right holders to disclose the terms of their licensing agreements. Thus, it becomes easier to instantly verify the legitimacy of content offerings. Also, this allows the new agencies to consider all existing options when allocating the most suitable service provider to the request.

Congestion can be counteracted by a matching mechanism (consisting of an algorithm that makes use of the clearing houses’ databases) which allows for the identification of the most suitable matching partner in a timely manner. Where multiple providers are suitable, other criteria, such as price and the terms on which access is granted, can be considered. A due diligence mechanism requires the review of the result to ensure that the best option is chosen. The existence of precise and transparent rules in the establishing regulation further supports the proper functioning of the new system.

We furthermore consider characteristics of AV works as intangible goods. Regarding the rivalry character of information, providers continue to be limited in their use of content for which they do not have rights. The new mechanism allows them to redirect their customers to another provider who offers the desired content. Where platforms are incompatible, a combination of suitable interfaces and a connection between them ensure that they can communicate with each other.Footnote16 The access code from the providing AV servicer allows the requesting party to unlock the former's services for his customers. Therefore, exclusivity is preserved.

The application of Gans and Stern's framework to our context shows that the content catalogue offered by a provider to its customers is an aggregation of catalogues from various right holders. The different contents complement one another, and their unique combination is what drives demand for the provider's service who can offer a ‘one-stop shopping’ opportunity. Moreover, the right holder depends on the provider to make content available to customers. Reproduction and redistribution can be prevented since the requesting provider does not get access to the actual content. Customers are merely redirected to the server of the ‘providing provider’ when accessing the additional content package with the access code. Therefore, the requesting provider cannot reproduce the other provider's content to offer it as one's own. Moreover, even if content is accessible, reproduction is unlikely as this would constitute a copyright infringement. Copyrights therefore support market safety which in turn facilitates multilateral exchange.

We add an extra consideration to the evaluation as introduced by Langus et al. (Citation2013). Since the ECHAR coordinates different sets of content rights, the copyright system might challenge the proper implementation of the new system. Consequently, a corresponding exemption needs to be embedded in the current copyright framework. The objective of copyright exemptions is to ‘[…] increase access to existing and future creative works where this is thought to be excessively constrained by copyright’ (p. 1f). The exemption required in this context supports the abolishment of prevailing barriers which counteract the establishment and functioning of the internal market and would thus find its legal basis under Article 114 TFEU. Moreover, the new system aims at overcoming the problem of missing markets for users who want to access copyright protected work across borders. The cross-border provision of content by providers who have obtained the respective rights from the right holders to providers without these rights enables the provision of new services. According to Langus et al.'s framework, these factors strengthen the case for a copyright exception. While the authors identified high transaction costs as a barrier to trade, copyright rules and licensing practices currently prevent trade between providers across Member States. As the new system does not have an adverse effect on the right holders’ incentive to invest in new content as has been highlighted before, and therefore does not significantly reduce revenues, the exemption in the copyright framework can be implemented without major opposition from stakeholders with vested interests.

From an economic perspective, the proposal would promote allocative efficiency as it reduces various types of transaction costs by simplifying the cross-border clearance process of content rights. This improves the matching of supply and demand as the new system provides a platform which facilitates exchanges. Consumers who could not access the AV works of their choice across borders now have a wider range of content to choose from. Also, existing vertical restraints in licensing agreements can be maintained, so that no additional inefficiencies (e.g., free-riding) will be introduced.

Conclusion

In the current debate about the DSM's achievements, voices have been raised that a ban of exclusive territorial licensing agreements is needed to limit geo-blocking measures which currently prevent consumers from accessing content across borders. Although the current system is associated with high transaction costs, it has been questioned whether a pan-EU licensing system would significantly reduce costs. The cultural and linguistic diversity in the EU provides for another argument in favour of exclusive territoriality as it facilitates customised content services. While the prevailing business practices in the AV market contribute to the fragmentation of the internal market whose completion is one of the fundamental aims of the EU Treaty, a ban of territorial licensing practices could have a negative economic impact. The implementation of such an approach is likely to decrease consumer choice and weakens the incentives to produce new content.

Our policy proposal introduces a central clearing mechanism for AV rights which enables the cross-border access of content, without banning territorial exclusivity while eliminating distortions in cross-border allocative efficiency. It leaves scope for further changes in the future, such as a reform or harmonisation of the copyright system.

Given current technological developments, it makes sense to briefly reflect on a possible implementation of a clearing house mechanism for IP rights through a blockchain technology.Footnote17 Note that a blockchain generates open and trusted records of transactions,Footnote18 which is a central aspect of our proposal. We expect that a ‘private’ blockchain,Footnote19 as a register and execution mechanism of content provision transactions, can be useful to design and execute smart contracts that (further) reduce transaction costs, while speeding up the clearing and settlement between consumers, providers and rights holders. Since the design will have to be compatible with national and European legal frameworks, it may be useful to add a central layer of governance while maintaining the decentralised ledger functionality.Footnote20 We leave a further assessment of a blockchain implementation, e.g., along the lines of Savelyev (Citation2018), to future work, possibly as a more detailed implementation analysis.

More generally, it is advisable to conduct stakeholder consultations and an impact assessment to ensure industry support and to fill in the details. A comparative analysis between different policy options (possibly including a blockchain implementation) would be useful to identify the most effective way to solve the problem of cross-border access to AV works while safeguarding the fundamental EU principles.

Acknowledgement

We are grateful to Thibault Schrepel (Dept. of Public Economics Law, Utrecht University) and two anonymous reviewers for helpful comments and suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Miriam Ettel

Miriam Ettel is a M.Sc. Economics of Competition and Regulation Graduate from Utrecht University School of Economics. She is working as a Specialist Advisor for Regulatory Engagement (Treasury) [email: [email protected]].

Paul W. J. de Bijl

Paul W. J. de Bijl is senior lecturer Competition and Regulation at Utrecht University School of Economics, owner/principal of Radicand Economics, and extramural fellow of TILEC, Tilburg University. His research interests include regulation of electronic communications, information policy, and the digital economy [email: [email protected]].

Notes

1 For example, determined via the payment method's origin, i.e., the country where a credit card was issued.

2 We abstract from workarounds like virtual private networks (VPNs) which allow users to disguise their location when accessing content outside their home jurisdiction because of uncertainty regarding its legality. This is particularly the case when users subscribe to paid services unavailable in their own jurisdiction using a VPN. Thereby, the copyright holder is not deprived of compensation. However, such an approach seems to counteract the underlying principles of the copyright system which our proposal aims at preserving.

3 See also Weiss (Citation2016) for similar observations (p. 884).

4 See Haunss (Citation2013) for an overview of the evolution of CMOs in Europe.

5 See Alaveras, Gómez, and Martens (Citation2017) for a broader discussion on geo-blocking of non-AV content.

6 One example are the Creative Commons which facilitate access to copyright protected works such as music and books through ‘free and easy-to-use copyright licenses’ (Creative Commons, Citation2016).

7 This view is supported by Langus et al. (Citation2014) who critically oppose any policy proposals abandoning the system of territorial licenses.

8 Langus et al. (Citation2014) provide an overview of factors contributing to high transaction costs in the AV industry. See also Weiss (Citation2016).

9 See Ibáñez Colomo (Citation2017) and Mazziotti (Citation2015) for similar observations.

10 Public broadcasting can be motivated by various reasons, such as a need to support national culture and values, and media plurality – which are subject to ongoing debate (see e.g., Picard & Siciliani, Citation2013). In the future, it might be worthwhile to explore the possibilities to add free on-demand catch-up services and pay-to view services via pay-TV platforms to the proposal.

11 Note that the scope of the proposal is limited. For instance, from a media policy perspective, it can be desirable that content is framed, explained and displayed in the appropriate local cultural context. Under the current proposal, there does not seem to be a direct role for the clearing house to achieve this goal (except perhaps for providing monitoring data regarding cross-border viewing of locally-textured content). As there are no clear complementarities between the legal (geo-blocking) aspects and the media policy goals, the clearing house should aim at eliminating avoidable frictions while policy goals regarding content may be addressed at the level of distribution.

12 To allow for the cross-border provision of AV rights, a corresponding exemption needs to be included in the copyright framework as discussed in the ‘Evaluation’ section.

13 Experience in the telecommunications and the postal sector with wholesale pricing rules may provide guidance on the impact of wholesale prices on the incentives of AV providers. See for instance Laffont and Tirole (Citation2000) and Geradin (Citation2017).

14 It is outside the scope of this paper to introduce a suitable matching and due diligence mechanism.

15 See, for example, Euroclear (Citation2012) for language requirements related to clearing documentation (p. 24).

16 Cf. solutions based on application programming interfaces (APIs) and communication links between different software platforms’ APIs.

17 For discussions of blockchain technologies applied to clearing and settlement, see for instance Peters and Panayi (Citation2016). For a broad discussion of blockchain applied to the copyright sphere, from a legal and computer science perspective, see Savelyev (Citation2018). Schrepel (Citation2018) discusses how blockchain, as a means to facilitate contracting and ‘cut out the middleman’, creates new challenges for antitrust law.

18 For an exposition on the central economic features of the blockchain technology, see Catalini and Gans (Citation2018).

19 Public (also called permissionless, i.e., without access control) blockchains rely on ‘mining’ as a means to receiving value. Private (permissioned) blockchains add value through applications, for instance, as a means for the transfer of assets, as registers of exchanges, and as execution mechanisms for smart contracts. See Schrepel (Citation2018) for a more elaborate description and discussion (in the context of antitrust law).

20 Based on a private blockchain, as public blockchains currently do not allow any form of governance other than the ‘consensus protocol’.

References

Literature

- Alaveras, G., Gómez, E., & Martens, B. (2017). Geo-blocking of non-audio-visual digital media content in the EU Digital Single Market. (Working Paper). JRC Digital Economy. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2983793

- Catalini, C., & Gans, J. S. (2018). Some simple economics of the blockchain. (NBER Working Paper). Retrieved from http://www.nber.org/papers/w22952

- Chalaby, J. K. (2016). Television and globalization: The TV content global value chain. Journal of Communication, 66(1), 35–59. doi: 10.1111/jcom.12203

- Creative Commons. (2016). What we do – What is creative commons? Retrieved from https://creativecommons.org/about/

- Earle, S. (2016). The battle against geo-blocking: The consumer strikes back. Richmond Journal of Global Law and Business, 15(1), 1–73.

- Euroclear. (2012). International securities operational market practice book. Retrieved from https://www.euroclear.com/dam/Brochures/MA1521_ISMAG_MPB_2012.pdf

- European Commission. (2005). Recommendation of 18 May 2005 on collective cross-border management of copyright and related rights for legitimate online music services. Retrieved from https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reco/2005/737/oj

- European Commission. (2015). A Digital Single Market strategy for Europe. Retrieved from https://www.parliament.uk/documents/lords-committees/eu-internal-market-subcommittee/Digital-Single-Market/COM-2015-192-final-digital-single-market-strategy.pdf

- Gans, J. S., & Stern, S. (2010). Is there a market for ideas? Industrial and Corporate Change, 19(3), 805–837. doi: 10.1093/icc/dtq023

- Geradin, D. (2017). Is mandatory access to the postal network desirable and if so at what terms? (Discussion Paper). Tilburg Law & Economics Center (TILEC).

- Grece, C., Lange, A., Schneeberger, A., & Valais, S. (2015). The development of the European market for on-demand audiovisual services. Strasbourg: European Audiovisual Observatory.

- Haunss, S. (2013). The changing role of collecting societies in the internet. Internet Policy Review, 2, 1–8.

- Hoffman, J. (2016). Crossing borders in the digital market: A proposal to end copyright territoriality and geo-blocking in the European Union. The George Washington International Law Review, 49, 143–173.

- Ibáñez Colomo, P. (2017). Copyright licensing and the EU Digital Single Market strategy. In R. D. Blair & D. D. Sokol (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of antitrust, intellectual property, and high tech (pp. 339–357). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Jones, A., & Sufrin, B. (2016). EU competition law: Text, cases, and materials. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Laffont, J.-J., & Tirole, J. (2000). Competition in telecommunications. London: MIT Press.

- Langus, G., Neven, D., & Poukens, S. (2014). Economic analysis of the territoriality of the making available right in the EU. Brussels: Charles River Associates Study for the European Commission.

- Langus, G., Neven, D., & Shier, G. (2013). Assessing the economic impacts of adapting certain limitations and exceptions to copyright and related rights in the EU. Brussels: Charles River Associates Study for the European Commission.

- Maciejewski, M., Fischer, N. I. C., & Roginska, Y. (2014). Streaming and online access to content and services. Brussels: European Parliament.

- Mazziotti, G. (2015). Is geo-blocking a real cause for concern in Europe? (Working Paper). Florence: European University Institute.

- Meurer, M. J. (2002). Vertical restraints and intellectual property law: Beyond antitrust. Minnesota Law Review, 87, 1871–1912.

- Peters, G. W., & Panayi, E. (2016). Understanding modern banking ledgers through blockchain technologies: Future of transaction processing and smart contracts on the internet of money. In P. Tasca, T. Aste, L. Pelizzon, & N. Perony (Eds.), Banking beyond banks and money (pp. 239–278). Cham: Springer.

- Picard, R. G., & Siciliani, P. (2013). Is there still a place for public service television? Effects of the changing economics of broadcasting. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, University of Oxford.

- Pirrong, C. (2011). The economics of central clearing: Theory and practice. New York: International Swaps and Derivatives Association.

- Plum Consulting. (2012). The economic potential of cross-border pay-to-view and listen audiovisual media services. Retrieved from https://plumconsulting.co.uk/economic-potential-cross-border-pay-view-and-listen-audiovisual-media-services/

- Poiares Maduro, M., Monti, G., & Coelho, G. (2017). The geo-blocking proposal: Internal market, competition law and regulatory aspects. Brussels: European Parliament.

- Roth, A. E. (2007). The art of designing markets. Harvard Business Review, 85(10), 118ff.

- Savelyev, A. (2018). Copyright in the blockchain era: Promises and challenges. Computer Law & Security Review: The International Journal of Technology Law and Practice, 34(3), 550–561. doi: 10.1016/j.clsr.2017.11.008

- Schrepel, T. (2018). Is blockchain the death of antitrust law? The blockchain antitrust paradox. Retrieved from https://ssrn.com/abstract=3193576

- Schroff, S., & Street, J. (2018). The politics of the Digital Single Market: Culture vs. competition vs. copyright. Information, Communication & Society, 21, 1305–1321. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2017.1309445

- Sherman, R., & Waterman, D. (2016). The economics of online video entertainment. In J. M. Bauer & M. Latzer (Eds.), Handbook on the economics of the internet (pp. 458–474). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Simonelli, F. (2016). Combating consumer discrimination in the Digital Single Market: Preventing geo-blocking and other forms of geo-discrimination. Brussels: European Parliament.

- Van Overwalle, G. (2016). Patent pools and clearinghouses in the life sciences: Back to the future. In D. Matthews & H. Zech (Eds.), Research handbook on IP and the life sciences (pp. 304–336). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Weiss, C. A. (2016). Available to all, produced by few: The economic and cultural impact of Europe’s Digital Single Market strategy within the audio-visual industry. Columbia Business Law Review, 3, 877–923.

- Wunsch-Vincent, S. (2016). The economics of copyright and the internet: Moving to an empirical assessment relevant in the digital age. In J. M. Bauer & M. Latzer (Eds.), Handbook on the economics of the internet (pp. 229–246). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Case law

- Joined Cases-403/08 and C-429/08, Football Association Premier League Ltd and Others v QC Leisure and Others; Karen Murphy vs Media Protection Services Ltd (2008).

Legislation

- Directive 2010/13/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 10 March 2010 on the Coordination of Certain Provisions Laid Down by Law, Regulation or Administrative Action in Member States Concerning the Provision of Audiovisual Media Services (Audiovisual Media Services Directive).

- Directive 2014/26/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 February 2014 on Collective Management of Copyright and Related Rights and Multi-Territorial Licensing of Rights in Musical Works for Online Use in the Internal Market (Directive on Collective Management of Copyright).

- Proposal (2016/0280) for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on Copyright in the Digital Single Market (Copyright Proposal).

- Regulation (EU) No 330/2010 of 20 April 2010 on the Application of Article 101(3) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union to Categories of Vertical Agreements and Concerted Practices (Block Exemption Regulation).

- Regulation (EU) No 648/2012 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 4 July 2012 on OTC Derivatives, Central Counterparties and Trade Repositories (European Market Infrastructure Regulation).

- Regulation (EU) 2017/1128 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 June 2017 on Cross-Border Portability of Online Content Services in the Internal Market (Portability Regulation).

- Regulation (EU) 2018/302 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 28 February 2018 on Addressing Unjustified Geo-Blocking and Other Forms of Discrimination Based on Customers’ Nationality, Place of Residence or Place of Establishment Within the Internal Market and Amending Regulations (EC) No 2006/2004 and (EU) 2017/2394 and Directive 2009/22/EC (Geo-Blocking Regulation).