ABSTRACT

We discuss how a capability approach to information technology in neighbourhoods with low social capital can create embedded and sustainable Community Technology Partnerships (CTPs) that connect residents and institutions together, reducing barriers to social participation and collaborative action. Current research indicates older people in deprived neighbourhoods have chronic problems with the effective sharing of community information, a key factor in the ‘digital divide’ [Niehaves and Plattfaut (Citation2014). Internet adoption by the elderly: Employing IS technology acceptance theories for understanding the age-related digital divide. European Journal of Information Systems, 23(6), 708–726. https://doi.org/10.1057/ejis.2013.19]. Manchester Age Friendly Neighbourhoods had 4,000 conversations in four ‘age-friendly’ resident-led neighbourhood partnerships in Manchester. This fieldwork demonstrated that the inability to create and share information within and across residents, communities and service providers is a key contributor to social isolation and barrier to local collaboration. MAFN developed a CTP to correlate perceptions that it was difficult to find out what was going on in the neighbourhood, with an exhaustive audit of actual activity. The result was collective surprise at finding out about dozens of events in each area that were previously either poorly communicated or which were not normally published at all, relying entirely on word of mouth. The CTP was developed using a capability model [Kleine (Citation2013). Technologies of choice? ICTs, development, and the capabilities approach. MIT Press] to discover and overcome both the social and technical barriers preventing the hosts of neighbourhood activities collaboratively and sustainably self-publishing their event information. This resulted in the production of PlaceCal, an holistic social and technical toolkit that ensures groups and individuals have the technology, skills, infrastructure and support to publish information, creating a distributed network of community information.

1. Introduction

This paper discusses how applying a ‘capability approach’ to information technology (Kleine, Citation2013) in neighbourhoods with low social capital can create embedded and sustainable ‘Community Technology Partnerships’ that connect residents and institutions together, reducing barriers to social participation and encouraging collaborative action.

We discuss the place of technology in communities in relation to the creation and sharing of information about local groups and events, and the impact of our own socio-technical intervention ‘PlaceCal’ which was piloted in a Manchester neighbourhood by {Manchester Metropolitan University (MMU) and Geeks for Social Change (GFSC) from 2017 until present.

The PlaceCal pilot created a community calendar which was co-produced by a wide range of partners working in the locality. It did this through a social intervention in the form of a community development programme which trained individuals, groups and organisations to curate and share a digital calendar ‘feed’ of their own events, and a technological intervention in the form of a digital platform for collating, processing and publishing those feeds to create a central source of community information.

We called this co-production process a Community Technology Partnership (CTP). The CTP used a capability approach to help understand the specific barriers preventing effective sharing of community information, and attempted to overcome them using a range of methods including community training, the PlaceCal software and bespoke technical documentation.

This paper will discuss the ‘age friendly’ context for the intervention, and how we built on existing work applying capabilities to IT. Throughout, we distinguish the capability approach from existing approaches, and conclude with the specific findings discovered delivering the PlaceCal CTP.

2. Neighbourhood partnerships and the capability model

2.1. Defining the capability approach

The PlaceCal CTP was conceived to apply a ‘capability approach’ to community technological development, building on existing ‘age friendly’ community development programme ‘Manchester Age Friendly Neighbourhoods’ (MAFN).Footnote1

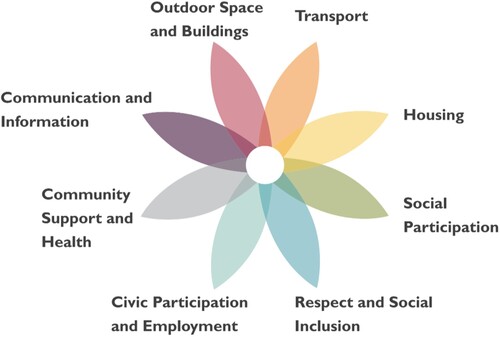

MAFN was conducted by an engaged-research team at MMU with the objective of co-creating resident-led multi-stakeholder partnerships located in deprived Manchester neighbourhoods. ‘Neighbourhoods’ were self-defined by residents in relation to political ‘wards’ of 6,000–10,000 people. The research component of this project developed a mixed-methods critical evaluation based on the World Health Organisation's (WHO) ‘Age Friendly Cities and Communities’ (AFCC) principles. This approach explores eight dimensions or ‘domains’ of well-being, including ‘communication and information’. The delivery component of the project focussed on creating neighbourhood partnerships that brought together communities of ‘place’ and ‘practice’, signifying that individuals were invested in the area in different ways: living, working, or both.

This deliberate mix of communities of place and practice is itself an application of a capability-based community development methodology. Our interpretation (White & Hammond, Citation2018) explores the AFCC concept of ‘active ageing’ as a position distinct from medical or social models of disability, emphasising the active self-determination of individuals in any social, economic or technical process (Nussbaum, Citation2003; Sen, Citation1999).

The AFCC ‘flower’ diagram () shows the interaction of multi-determinants of healthy ageing for an individual older person. Each petal represents a different domain in the social, economic or physical environment. The diagram demonstrates how the ‘age friendly approach’ must place individual human experience at the centre of any understanding of opportunities for a well-lived life, and at the centre of any actions taken to improve those opportunities (World Health Organization, Citation2007).

Definitions of the capability approach insist on ‘people's freedom to choose the lives they have reason to value’ (Sen, Citation1999, p. p18). All aspects of the social, economic and physical environment are implicated in the interdependent structural enabling or disabling of each individual's desires. In capability terms, Kleine (Citation2013), using Alsop and Heinsohn (Citation2005, p. p8), shows how the agency of the individual to make meaningful choices is a capacity that is measured by that individual's asset endowment which has psychological, informational, organisational, material, social, financial and human components.

Using a more philosophical tone, Nussbaum describes the capability model in the form of a question: what are the people of the group … actually able to do and be? (Nussbaum, Citation1999, p. p34). This offers a concrete ethical test to ensure that people are being engaged in a manner which respects their fundamental existence, rather than having choices ‘made for them’ on the basis of external characterisation or assumptions of their abilities, feelings or opinions. The test contains the expectation that this question needs to be asked of all individuals and groups, and requires an ongoing negotiation between all Beings (White, Citation2018).

A capability approach must therefore recognise the right of each individual to define their Being, in relation to their own social, economic and political context. It requires direct engagement with citizens and the discovery of their actual (not presumed) desires. It must understand that people are part of groups and societies, and that capabilities are collective and relational. The capability approach supports individuals to overcome actual and specific barriers to realising desired states of being: indeed, this is why it is an approach and not a model (Sen, Citation1999).

We summarise this interpretation of the capability approach and how it can be distinguished from other attempts to enable greater equity of opportunity in .

Table 1. Models of difference.

The deficit or ‘medical’ model centres individuals' deviations from ‘the norm’: in other words, ‘abnormal’ individuals are assumed to have a ‘deficit’ of some kind. Franklin (Citation1999), speaking in a technology context, bluntly states: ‘people are seen as sources of problems, while technology is seen as a source of solutions’. By contrast, the social model sees disability as created by the individual's relationship to the social environment, and argues that deficit-based approaches actually disable communities by implying ‘communities in and of themselves are not competent [and] require the expertise of professionals’ (Durie & Wyatt, Citation2013).

While the difference between the deficit and social models has been widely discussed, there is little formal academic discussion about the relationship between the capability approach and other models. In a rare example, Mitra (Citation2006) explains that ‘the capability approach allows disability to be differentiated at two levels: at the capability level, or as a potential disability, and at the functioning level, or as an actual disability’.

This vital distinction between potential and actual disability disrupts generic, ‘representational’ approaches which create normative categories and disabling judgements. This insistence on the real potential and actual conditions of the existence of individuals and groups enables positive engagement with the real conditions of opportunity, and makes them part of the context for any future transformation.

Durie and Wyatt (Citation2013) explore the practical application of these issues in a case study of ‘The Beacon Project’ where construction of a resident-led multi-stakeholder partnership is shown to have transformed health, social and educational outcomes in a highly deprived neighbourhood in Cornwall over more than 22 years. This ‘C2 Connecting Communities’ methodology shows how the development of interpersonal relationships between a range of stakeholders is central to the success of any programme of transformative community development. Durie and Wyatt argue social transformation is enabled through active collaboration of previously unequal and adversarial stakeholders (‘the community’ and ‘the authorities’) because these direct relationships increase the ability of both groups of stakeholders to address ‘common’ problems, enabling an emergent future which was previously unachievable.

Both MAFN and the Placecal CTP followed the C2 methodology in order to operationalise this interpretation of the capability approach.

2.2. Technology and capability

explores differences between the three broad models of dis/ability. In our interpretation these approaches are complementary. The capability approach builds on both the social and deficit models, allowing direct engagement with the desired capabilities of communities of place and practice. This section compares these existing discussions with the CTP approach.

OECD (Citation2016) paints a bleak picture of digital skills in the UK. This study divides common computer skills into several categories from 1 (simple) to 3 (complex). Level 1 skills consist of a range of day-to-day computing skills like ‘deleting an email’. 40% of ‘working age’ adults aged 16-65 struggle to complete all the tests at this basic threshold, being described as ‘under level 1’.

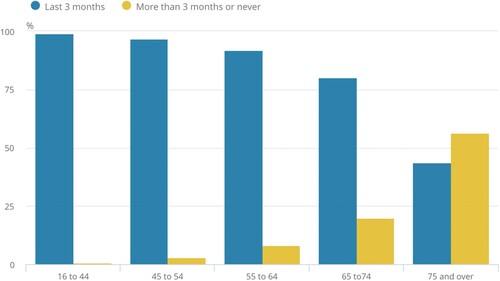

This picture is much worse for older people, who are significantly less likely to use the internet than the average population (Niehaves & Plattfaut, Citation2014). Office for National Statistics (Citation2019, ) found 56% of those over 75 have either never been online, or not been online for over three months, increasing to 61% for over 75s with disabilities. The reasons for this are varied. 52% of non-internet users aged over 65 think that they're simply not missing out on information (Pew Research Centre, Citation2014b), 65% think it's too complicated and 53% have privacy concerns (Friemel, Citation2016). This is exacerbated by social class, with 40% or less of over 65s with a high school education or less being online, compared to 87% of college graduates in the USA (Pew Research Centre, Citation2014a).

Figure 2. Internet users by age group (Office for National Statistics, Citation2019).

What people actually do when they're online is varied and heavily correlated with class and age. Digital exclusion is intersectional, and the worst experiences are suffered by those who are older, less well educated, less likely to be employed, female and disabled (van Deursen & van Dijk, Citation2014, p. p520). This results in a skills gulf between tech ‘haves’ and ‘have-nots’. Being digitally included is not a simple binary test – ‘are you on the internet / using a smartphone / on Facebook?’ – but a complex multidimensional matrix of skills and capabilities. This matrix is highly impacted by a range of psychosocial variables and overall motivation (McNeal et al., Citation2008) for the specific ‘clickable possibilities’ (Kleine, Citation2013, p. p38) the citizen wants to accomplish.

This situation is worsened still through the current desire for government and statutory services to be ‘digital by default’ (UK Cabinet Office, UK Government Digital Service, & Rt Hon Lord Maude of Horsham, Citation2012), or worse, online only. In the UK, key activities such as claiming benefits, filing tax returns, and accessing medical services are in the process of being moved online ‘to transform public services … making them better and cheaper for taxpayers and more effective and efficient for government’ (ibid.). In other words, services are no longer ‘door-to-door’ but rather ‘person-to-person’, mediated by the internet (Wang et al., Citation2018).

In practice this is placing increasing strain on ‘human’ services for older people. Anecdotal reports published by Age UK (Citation2015) demonstrate this issue concretely:

Exclusion from online services … is a growing problem and people are sent to us to help. Telephone lines are busy and you are directed to online communication for almost everything – benefits, gas and electricity, tax, Blue Badges etc. Our local authority wants most changes reported online and they offer very little face-to-face service and are reluctant to take changes over the telephone (if you can get through that is). For sites that require an email before you proceed this is more of a problem as most clients don't have one.

Current strategies to rectify this systematic exclusion in a technological context fall into two categories: ‘a11y’ and ‘digital inclusion’.

‘a11y’ is a deficit-based technical perspective. Online campaign sites such as a11yproject.com consist of advice to software developers on how to make sure websites can be used by people with visual impairments, colourblindness and impaired motor skills for example. Such initiatives perform useful functions, but as perhaps indicated by the cryptic obfuscation of ‘a11y’ – there are 11 letters between ‘a’ and ‘y’ – the focus is on (software) ‘users’ who by definition are separate from the expert professionals who produce these websites. Needless to say, this approach does not engage with wider determinants of exclusion and only considers the user's literal interaction with the service.

‘Digital inclusion’ takes a skills approach that considers the social factors that might make someone unable or unwilling to use desirable technology. UK Cabinet Office, & UK Government Digital Service (Citation2014) breaks down digital inclusion into four categories: ‘access – the ability to actually go online and connect to the internet; skills – to be able to use the internet; motivation – knowing the reasons why using the internet is a good thing; and trust – a fear of crime, or not knowing where to start to go online’, for example. ONS data (Office for National Statistics, Citation2019) indicates that this approach has a very long way to go to make government digital services inclusive for older people.

Our critique of the current situation is that neither of these initiatives seek to address underlying causes of digital exclusion by transforming technology provision to make it more inclusive. Park and Humphry (Citation2019) note ‘digital inclusion can only be realised if all dimensions of access, affordability and digital literacy are resolved’. We add that these are all complex social and economic factors that cannot be explained through ‘the digital’ or ‘literacy’ alone: current formulations implicitly presume that existing services are approaching perfection, and that anyone who doesn't use digital technology for a given task has a social or physical impairment.

Ultimately, both the deficit and social models of technical inclusion seek to enable people that were excluded from the design process to adapt to pre-existing systems. By contrast, a capability approach seeks to design systems and products which support people's freedom to choose the ‘lives they have reason to value’ (Sen, Citation1999, p. 18) – in our case, the wish to find things to do and people to meet locally in a deprived area bereft of digital capacity.

3. How we made a community technology partnership

The remainder of this paper discusses how we formed a CTP. A CTP considers all the people, skills, infrastructure, tools and resources in a neighbourhood, analyses barriers to digital participation, asks what it is that people want to do and be, and co-creates technological and social interventions to overcome these barriers.

We first discuss the existing research and community development conducted during the MAFN project that created the emergent context for PlaceCal. We then discuss the local impetus for an initial prototype. Finally, we explore the core capabilities discovered through this process, the key barriers facing each, and how we worked to overcome them in a community context through the PlaceCal intervention.

3.1. A capable neighbourhood

The MAFN co-research process involved over 6,000 conversations, culminating in the development of ‘Age Friendly Action Plans’ for each of the 5 communities where research was undertaken.Footnote2 In each case, the action plans demonstrated that ‘community information’ was a significant issue, a finding supported by a wide range of health, housing and social care stakeholders.

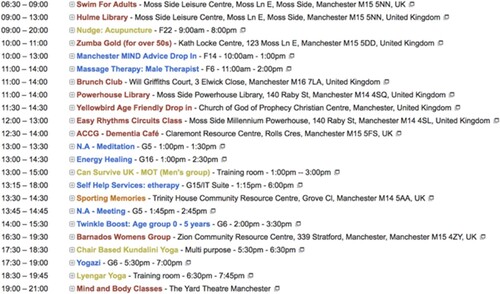

This research discovered a widely held perception there was ‘nothing to do’ in each of the neighbourhoods. An exhaustive audit of community activity in each area then discovered, on the contrary, that there was a significant amount of activity even in the least active area. These activities involved a wide range of stakeholders from tiny community groups to city institutions. This events were collated into shared Google Calendars maintained by MAFN's community development workers. These calendars () became an extraordinary resource that allowed each partnership to get a fuller picture of what was happening locally, enabling previously impossible collaborations and validating the C2 methodology.

People are saying they're bored and there's nothing to do – with this much on that's mad isn't it!

F/70s, resident in pilot area

Engagement with institutional partners revealed that across health, housing and community sectors there were a number of existing attempts to catalogue community activities described in terms of ‘asset mapping’ or ‘community directory’ initiatives. Each attempt, like the MAFN calendar, was inherently limited by funding and time, and required constant community development work to maintain.

The PlaceCal CTP evolved by exploring all the ways that we could increase connectivity and communication between project partners. Working within the MAFN partnership, we established that there was the potential for a collaboratively maintained, high quality, up-to-date and trusted central information source.

We investigated why community information availability was so poor despite extensive efforts by a range of institutions. This consisted of direct engagement with a range of stakeholders, a recognition of systemic and structural inequality, and active participation of partnership members in all creative stages. The CTP focussed on the capabilities of individuals and communities to create better lives for themselves and each other in the place that they live, as opposed to a focus on any single technology or inclusion goal. It sought to create positive affective relationships between individuals, community organisations and institutions that enable realisation of each partnership actor's desires to meaningfully collaborate to create, publish, curate and maintain information.

Our working definition of a capability approach in the context of place-based communities therefore has three components:

direct engagement with and involvement of multiple stakeholders, (responding to real lived experience, not relying on representations created externally)

in a creative partnership, (working together to identify and address shared goals, ensuring all are included in the process)

actively enabling realisation of both group and individual capabilities. (generating new actual and potential resources through enabling new relations and actions).

3.2. How we made a community technology partnership

As briefly discussed, PlaceCal was initially conceived of as a tool to move from the single, central, manual calendar maintained by the MAFN team, to an automated, cross-sector tool grounded in the existing partnership work. MMU and GFSC gained funding from Innovate UK's Smart City programme ‘CityVerve’.

We used the term ‘Community Technology Partnership’ to describe an intervention process that uses direct engagement with a broad range of stakeholders to build a partnership that facilitates co-production of a digital, technological object. The PlaceCal CTP had the specific goal of designing, creating and maintaining a social and technological intervention that could improve aspects of community connectedness, impact on social cohesion, and reduce social isolation in low social capital neighbourhoods. We deliberately distinguish the development of PlaceCal and the CTP approach in order to fully realise the importance of both, and offer a methodology for creating technological products in an embedded community context.

We will now briefly describe how this methodology was applied.

3.3. Developing a prototype

MAFN created a ‘manual’ Google Calendar (Section 2.1) of all the events we were able to discover in 18 months of community engagement (). This calendar was eventually stretched to the limits of the software. For example, it was not very good at browsing lots of events at the same time, had no geolocation features, and required an ongoing connection to the MAFN partnership to access. Crucially, this manual version required constant updates and maintenance, resulting in more work being created the more successful it got. The PlaceCal project built on the underlying context that each organisation was actively sharing information with the MAFN partnership, and was maintaining a diary of some kind that allowed us to share their information.

We realised that if we could encourage each group in the partnership to publish their calendar online using software they were already using such as Outlook, Mac Calendar, Google Calendar or Facebook, we could use the built in ‘iCal’ or ‘API’Footnote3 features of these calendars to automatically collate and publish the information ‘feeds’ in one place. Rather than the current system where each worker writes up a ‘snapshot’ of each group's activities whenever they met the group, we would work with each group to help them publish a feed, enabling collaborative publishing with much lower effort and much wider reach. This central source of event information would therefore be a canonical source of local information that could be shared online and in print by every partner.

GFSC developed the PlaceCal software in Ruby on Rails, a popular framework for rapidly developing web applications. It is live at placecal.org . Source code can be downloaded from GitHub under the AGPL license.Footnote4 Training and support materials are published at handbook.placecal.org . All these tools were made free and open source to demonstrate our commitment to our overall methodology rather than any one software tool; to make development and design decisions public and transparent; and optimistically to encourage teams doing similar work in other neighbourhoods to be able to directly contribute to feature development.

Through co-design workshops with the age friendly partnership in Hulme and Moss Side we ensured accessibility (a11y) of the site and branding by getting direct feedback throughout the process. Key developments included a warm and engaging ‘mid century’ colour scheme that still met high accessibility standards, a spacious design that reduces cognitive overload, a larger font size, and a user experience that requires as few clicks as possible to access information. The font size and colour scheme were tested with different groups of older people to ensure the site was ‘inviting’ and ‘friendly’.

We designed the event importing functionality in a modular way that allowed us to rapidly develop importers for any feed we discovered during the fieldwork process. As we spoke to each group, we created these importers as needed, and documented the process in our handbook. This handbook became our key resource for understanding and documenting the widely diverging technical and social contexts of groups attempting to publish information in our pilot area.

Given this diversity of technical requirements and the social complexity of getting individuals, groups and institutions to share their calendar feeds, it was very important for us to be content-agnostic and work with whatever we were given. A large amount of development time therefore went into creating a system that could piece together missing information such as venue names, event addresses and alternate names for the same building.

Our final prototype had three key features: a list of activities on each day (‘show me what's on right now’), a list of activities at each community venue (‘show me what's on at my local venue’), and a list of each ‘partner’ (‘show me the kinds of things I can do in my area’).

3.4. The capability engagement processes

With our prototype in place, we began engaging every member of the MAFN partnership. Our a priori categories for these groups were: ‘Institution’ (e.g., Manchester City Council); ‘Voluntary’ (e.g., third sector community centres) and ‘Community’ (e.g., small unincorporated groups). Each group was consulted for up to an hour with a semi-structured interview about both what the group did, and their current technical capabilities. This research uncovered a wide range of social and technical barriers such as: fearing the time and effort it would take; not understanding the meaning and efficacy of involvement; not having an internet connection; not knowing who in the organisation was responsible for digital publishing; and either not being able to get permission, or being unsure if permission was required.

This process led to a sophisticated understanding of the actual and desired capabilities of a wide range of organisations, and covered all aspects of publishing, editing, reading and curating information. From these discrete wishes emerged a list of ‘core capabilities’ (Nussbaum, Citation2003) or ‘roles’ that people wanted to ‘do and be’. These roles are summarised in .

Table 2. PlaceCal roles.

Most people belonged to more than one of these roles: for example, everyone is a ‘citizen’, and ‘secretaries’ are often also ‘social prescribers’. We found this taxonomy accurately described the shared objectives and barriers in our specific context, and facilitated a shared understanding of the capabilities we needed to enable. It's important to note that these roles help identify general common barriers across a range of distributed stakeholders, and do not replace the requirement for individual engagement with each group to discover their specific barriers. Identifying these roles was a key tool in understanding design objectives, communication, support and training.

The rest of this section explores these roles in depth, and how through direct engagement in a creative partnership we actively realised their increased capability (see Section 3.1).

3.5. Roles and their capabilities

3.5.1. Secretary

An early finding was that several public health institutions, community activists and development workers were working to create ‘asset mapping’ or ‘community directory’ services. Tools provided to do this were either non-existent or poorly designed, resulting in a range of spreadsheets, printouts and software being used within each organisation, each incomplete, with overlapping and conflicting information, mirroring the situation for the organisations hosting and running activities.

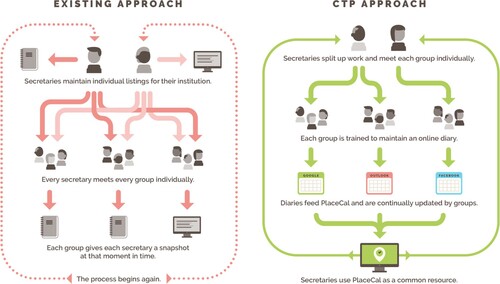

We describe people conducting these efforts as ‘secretaries’: not a ‘technical’ role, but one with the ambition to ‘enable local groups to publish information’ and ‘be able to curate local information to create an active local identity’. PlaceCal was designed to overcome the current situation where each secretary must meet each group individually and manually create a list of events at that moment in time, creating an increasing list of out of date information sources. Every extra secretary therefore actually increased the total effort required for each community group.

The CTP approach instead provided a training package that enabled secretaries to support each group to maintain their own listings, which were then aggregated and published on PlaceCal. This shift in structure is shown in . Work could therefore be divided between secretaries in an area, shifting the focus from simply maintaining immediately out-of-date information sources to skills-based digital inclusion that enables groups to promote themselves.

Some organisations, when trained to publish their own information, listed almost twice as many events than they were able to list in a face-to-face interview. The most frequent barrier to obtaining this information was finding out who the person responsible for maintaining the diary was in each institution, taking time, trust and patience for effective engagement.

One example of the success of this approach is that City Council's Central Neighbourhood Team were able to shift their focus from reactively supporting local groups individually, to strategically managing cross-neighbourhood events such as Winter Festivals in 2017 and 2018. These Festivals had been dormant for many years, precisely because of a lack of joined-up information sources in the current climate of austerity.

We use PlaceCal regularly in terms of understanding the neighbourhood, and also sharing with others. It helps us understand the diversity of people and groups and what's of interest to people, that picture of the diversity.

Patrick Hanfling, Central Neighbourhood Team Lead, MCC

Crucially, this role enables existing trust networks to be replicated ‘online’, enabling the neighbourhood to present a collective, inclusive identity. Our ongoing ambition is to establish institutional buy-in so that our onboarding process becomes a routine activity of frontline workers who will become PlaceCal secretaries and help ‘curate’ local information.

While many secretaries helped with the PlaceCal rollout, we were unable to fully train them to use PlaceCal directly due to our pilot's limited resources and the relatively high technical and social skills required to effectively engage local groups. To fully realise this role we are seeking funding to co-develop a ‘train the trainers’ programme. As this would be a small number of people to train in any given context (say 5–20 per 50,000 people) we believe this to be an easily surmountable problem.

3.5.2. Community groups (managers and admins)

‘Community groups’ are incorporated or unincorporated organisations that target a specific neighbourhood. We identified two key roles within them in the CTP context: ‘managers’, who were able to make strategic decisions and commit institutional resources needed to be part of the PlaceCal platform, and ‘admins’, who had the job of actually maintaining calendars and bookings on a day-to-day basis. In some cases, these were the same person, again reflecting the social/relational rather than technical/representational aspects of this work.

Secretaries worked with community groups to understand their technical and social needs. Overall we discovered an enormous skills gulf representative of the discussion in Section 2.2, with groups of all scales struggling to use their current software and computer assets effectively, and unable to take on any additional technology. For example, members of large institutions commonly did not know how to access internal systems (or the bureaucracy in using them was insurmountable), and small groups often didn't know they already had a calendar programme as part of their email suite (Outlook 365 or G Suite, for example). It was demonstrated very quickly that the PlaceCal approach of working with existing calendar software was the only way this job would be possible, with the median time to ‘onboard’ a group using software they already had being upwards of one day over several conversations, emails, phonecalls and visits.

By helping groups publish events using existing tools, we made the crucial job of diary publishing as easy as possible and with a clear definition of success: publish a calendar feed and let us know about it. For example, one community organisation with two large venues published only a weekly paper leaflet distributed on their front desk, and were not able to publish this information online. As the result of a key worker publishing this information in their existing Outlook system, PlaceCal has become the core events listing for the service, removing the burden on an already overstretched admin staff. In another case, it emerged the system in use was already outputting an iCal feed.

I am so pleased you think you can link to what we already have. I was quite concerned about setting up something additional as we don't have people with the skills or time to keep it all up to date. I have just about got to grips with what we do have!

Susan Ash, Mossley Community Centre

Secretaries and community groups working in partnership has allowed cross-sector access to accurate information about what everyone is doing, making a complex system of interrelated information streams seem simple and manageable. This collaborative publication means that the ephemeral ‘community’ now exists as a coherent body, enabling a range of actors to easily discover everyone active locally.

In one example of this, a resident (F/50s) conducted an oral history project looking at how people use herbal medicine across different cultures. She told us that PlaceCal made it possible to get otherwise inaccessible contact information for range of groups, resulting in a multicultural herbalism event at a local garden centre. The CTP has therefore enabled the active realisation of projects far beyond our initial scope, drastically increasing community capability indirectly.

Community groups in the pilot area have been supported to publish information sustainably with low effort. Sen's (Citation1984) terms, this increases their ability to convert capital (in the form of staff time) into capability (the ability to publish information effectively). Through the partnership, this information is now widely distributed with no additional effort on behalf of individual groups.

3.5.3. Social prescribers

‘Social prescribers’ are individuals and organisations support the health of the community by helping them connect to local activities, programmes and opportunities. Nesta (Citation2013) discovered 90% of GPs would ‘socially prescribe’ if they had access to the right information, but only 9% of patients have received social prescriptions, a finding supported by the UK Government and NHS England (Citation2019). This was validated in our pilot area through work with a local GP practice.

I think it's really fleshed out the challenge of how we get information out. Having a tool to let people find this out themselves seems totally obvious, it lets people teach me stuff, like ‘oh that refugee service is better than that one’, that helps us find a way together.

Dr Alasdair Honeyman, GP

Discussion with Dr Honeyman made it clear that ease of access to community information was a major barrier to social prescribing. The average UK GP visit is under 9 minutes (Irving et al., Citation2017), meaning that individual flyers and posters for each service () were practically unusable as they took too long to browse, had graphic design that obscured the content, and went out of date quickly. Additionally, in order to feel comfortable giving a recommendation it was crucial to know that event listings were reliable, trustworthy and accurate.

Figure 5. A selection of the current community information needed to find out everything going on in the area.

Ongoing CTP development work created trust that PlaceCal listings were accurate and up-to-date. A single point of reference for daily activity led to Dr Honeyman setting up a screen just for PlaceCal, using it routinely in consultations (). This has been instrumental in discovering specific and invisible lacks such as provision for a recent influx of Somali refugees, for example.

Creating a de-siloed, community owned and curated social prescribing resource has dramatically improved relationships between GP practices and community groups, giving health workers the capability to care for the widest possible range of patient needs with little additional effort.

3.5.4. Commissioners

Contributing to community partnership work are individual institutional commissioners who actually commit staff and resources. PlaceCal engaged with NHS commissioners, housing associations, Manchester City Council (MCC), the GP Federation and health and well-being workers, to establish Manchester Public Information Group (ManPIG).

We quickly discovered a stubborn assumption that the internet has already made information about community activity universally available and free. On reflection with the group, we discovered that this was highly correlated with social capital. Given it was at least possible to find out about high social capital cultural events such as classical concerts, theatre and art, it was counterintuitive to discover that information wasn't available at all for more deprived communities. While there was a desire to, for example, ‘see all the classical concerts on tonight in one place’, this was seen as a ‘nice to have’, not the critical public health issue experienced by our pilot area. It became clear that this level of misunderstanding was a key barrier to overcome to justify the CTP approach to those who controlled city-wide budgets. One local councillor shared our frustration:

PlaceCal captures information that isn't held anywhere else. This is particularly useful to people who don't use social media, which can often be older people who are at higher risk of being isolated. What a shame it was they didn't know about all these other events or projects, precisely because there isn't a central place for them to be shared.

Cllr Emily Rowles

We worked with senior managers across multiple sectors to understand these city-wide information issues in understanding the full range of community activity. We were surprised to discover that very often we had the only ‘technical’ knowledge in the room, highlighting the lack of ‘technological’ knowledge even at the very top of statutory organisations. Through ‘demystifying’ this knowledge and sharing our methodology openly with the group, we co-authored group aims and objectives. This process has highlighted the importance of good quality information, and begun the process of de-siloing information commissioning processes, enabling these groups to work together on shared cross-sector initiatives.

3.5.5. Citizens

The CTP's decentralised network of residents and service providers sharing information through the PlaceCal platform has enabled everyone to work better together, is highly cost effective, and has enabled a range of previously impossible tasks. It has radically transformed neighbourhood information for each involved stakeholder and the citizens of the neighbourhood. We estimated about 3% of total community activity was accurately published at the start of the project, compared to 70% during the pilot. This dramatic increase has reduced the ‘degrees of separation’ between individuals and neighbourhood activities and services directly and through friends, family and peers. Many of the success stories in the PlaceCal pilot have been through these indirect connections: concerned friends, social prescribers and health workers who now have the capability to help residents better engage with their neighbourhood.

An example of co-operative impact is the Hulme Winter Festival in 2018, where over 15 organisations came together to organise a shared festival across multiple sites, collaboratively funding an A2 ‘whats on’ guide containing information about each individual group. 10,000 guides were printed and distributed to homes and community centres by volunteers and staff across multiple organisations. This meant that even the 61% of disabled adults over 75 who do not use the internet () directly benefitted from a ‘digital’ intervention. Needless to say, door-to-door delivery of service information was previously unimaginable for individuals group and institutions in the pilot.

Many citizens and the MAFN partnership have now reported that they can much more easily find community information crucial to their health and their quality of life. More citizens now feel part of a supportive and engaged community and no longer struggle to find and get involved with running social activities, directly increasing both their own capability and the capability of the groups joined.

One elderly man vv poorly who felt he was so poorly and isolated thought he was going to die. Said the [xmas] tree and food had saved him.'

WhatsApp message sent by resident volunteer at 2018 Winter Festival

I was a bit low and my doctor asked me about stuff I liked doing and I wasn't sure. We had a look at the things that were happening [on PlaceCal] and I always wanted to do some craft or sewing work. I bought a machine ages ago but didn't have the confidence to know what to do. Now I am learning to make all sorts of things. I can repair stuff like holes and zips and other things. My doctor thinks the sewing group might have been what helped me stop needing my antidepressants – I think they helped too.

‘Samina’, Moss Side resident

4. Conclusion: making a place for community technology

The main difference between a capability approach and deficit or social model is that that it considers the whole social and cultural context of each individual's lived experience. Deficit approaches only address technical issues related to physical accessibility, while social approaches only address issues related to categories of social accessibility.

These approaches do not require either direct engagement with those who are excluded, or a social commitment to helping individuals overcome their specific barriers, but instead focus on representational issues (‘could someone with a disability theoretically access this service?’) with little (or no) accountability to any specific population (‘is this specific person or group actually benefiting from this service?’).

The CTP approach requires a creative partnership that can produce active solutions to specific experiences of exclusion that address the interdependence between social and technical issues. We believe that the case study presented here strongly indicates that such an integrated process can create dramatically more inclusive opportunities.

The PlaceCal CTP used a capability approach to transform community information in our pilot area. Our approach has three stages:

direct engagement with and involvement of,

multiple stakeholders in a place-based creative partnership,

actively enabling realisation of self-defined opportunities for individuals and groups.

We believe engagement that seeks to overcome exclusionary mechanisms and create and realise opportunities must be concretely situated. ‘Direct’ engagement recognises that it is the quality of the relationships between specific people in a particular place which enables the expression or suppression of the capability of individuals. The specific barriers faced by individuals and groups are varied and interdependent and social and technical, all at the same time. A CTP supports each community group to directly collaborate with the agencies and access the expertise needed to address the specific barriers that prevent people achieving active, ontological goals in their own neighbourhood. This specificity is essential to transforming both individual and collective capability.

The PlaceCal CTP focusses on working with specific people to create a source of trusted community information. This could mean helping convert a paper calendar into a digital one; negotiating with managers for permission to share information; working with off-site IT support to set up information sharing systems; or making a printout available at a local corner shop on request. While each of these desires has an accessibility and inclusion requirement that could be addressed individually, it is clear that a capability approach has the potential to fulfil these unique needs in a simple, meaningful and timely fashion.

A CTP creates a wide range of shared benefits by enabling specific people in a particular place to realise opportunities that they were unable to do before. It increases the capabilities of both individuals and groups working in partnership, enabling people not to use technology as an instrument but use technology to ‘do and be’ what they actually want.

4.1. Barriers to adoption

Despite the many benefits of the CTP model compared to other methodologies with more limited scopes, we have found it very difficult to gain adoption and funding in the siloed public sector environment described in the paper. As an asset-based approach developed in the academy, while we have been able to successfully access innovation funding and have gained widespread praise in our pilot area, we have not been able to secure ongoing investment from project beneficiaries such as social prescribing initiatives and city councils.

We believe the key reason for this difficulty is the widespread lack of recognition of the devastating impact of digital exclusion on the lived experience of local residents. Despite consensus around the qualitative value of the work of PlaceCal on the ground, and its adoption as day-to-day tool by local stakeholders, there was no institutional appetite to provide funding without evidence that increased information about events and services had a ‘direct’ health benefit.

For example, we were often asked to show that attendance at local venues increased as a result of PlaceCal. Given registers of event attendance were not currently kept or shared by the community groups in the pilots, demonstrating this would require a large-scale neighbourhood-wide evaluation that would likely be as large a time and money investment as the project itself.

This example demonstrates that despite an abundance of so-called ‘asset-based’ and ‘partnership-based’ approaches in the neighbourhood, there is currently no consensus on health and social care priorities. Instead, each group set its own priorities and expectations and expected external projects to conform to this. This meant that each bid or pitch had to be effectively written from scratch in the format expected by each specific organisation. Even willing and eager organisations struggled to identify in which budget and department PlaceCal would ‘belong’, straddling ‘innovation’, ‘communications’ and ‘neighbourhood services’ for one registered housing provider.

If evidence of and attendance at events was already recorded by these partnerships it would demonstrate an awareness that access to information matters, and give us an existing reporting framework to demonstrate project success. The absence of these frameworks, and the lack of good community information, are therefore co-constituted barriers to institutional adoption.

Adopting a CTP approach sustainably therefore requires high level institutional support for cross-sector transdisciplinary approaches, and a willingness to confront digital exclusion as a part of standard practice across all aspects of public sector service provision. The authors are hopeful these barriers can be overcome given the immense benefits to a range of stakeholders that the CTP approach offers.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Matt Youngson and April Manderson (MAFN); Mark Dormand, Jazz Chatfield and Justin Hellings (GFSC); Age Friendly Hulme and Moss Side; Dr Alaisdair Honeyman; and Patrick Hanfling.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Stefan White

Stefan White (he/him) is acting co-head of architecture at the Manchester School of Architecture. http://msaphase.org/. Email: [email protected]

Kim Foale

Kim Foale (they/them) is the founder of Geeks for Social Change, a design studio focussed on the intersections between community organising, research and technology. https://gfsc.studio. Email: kimgfsc.studio

Notes

1 MAFN was based on a successful and ongoing 2012 pilot project (Phillipson et al., Citation2014) undertaken in partnership with Southway Housing Trust.

2 The Manchester wards Old Moat, Moston, Miles Platting, Burnage and Hulme and Moss Side (one area).

3 ‘Application Programming Interface’, a computer-readable public interface to a database

References

- Age UK (2015). Later life in a digital world. https://www.ageuk.org.uk/globalassets/age-uk/documents/reports-and-publications/reports-and-briefings/active-communities/later_life_in_a_digital_world.pdf

- Alsop, R., & Heinsohn, N. (2005). Measuring empowerment in practice: Structuring analysis and framing indicators. https://doi.org/10.1596/1813-9450-3510

- Durie, R., & Wyatt, K. (2013). Connecting communities and complexity: A case study in creating the conditions for transformational change. Critical Public Health, 23(2), 174–187. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/09581596.2013.781266

- Franklin, U. (1999). The real world of technology. House of Anansi.

- Friemel, T. N. (2016). The digital divide has grown old: Determinants of a digital divide among seniors. New Media & Society, 18(2), 313–331. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444814538648

- Irving, G., Neves, A. L., Dambha-Miller, H., Oishi, A., Tagashira, H., Verho, A., & Holden, J. (2017). International variations in primary care physician consultation time: A systematic review of 67 countries. BMJ Open, 7(10), e017902. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017902

- Kleine, D. (2013). Technologies of choice? ICTs, development, and the capabilities approach. MIT Press.

- McNeal, R., Hale, K., & Dotterweich, L. (2008). Citizen–government interaction and the internet: Expectations and accomplishments in contact, quality, and trust. Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 5(2), 213–229. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/19331680802298298

- Mitra, S. (2006). The capability approach and disability. Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 16(4), 236–247. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/10442073060160040501

- Nesta (2013). Social prescriptions should be available from GP surgeries, say four in five GPs. https://www.nesta.org.uk/news/social-prescriptions-should-be-available-from-gp-surgeries-say-four-in-five-gps/

- NHS England (2019). Army of workers to support family doctors. https://www.england.nhs.uk/2019/01/army-of-workers-to-support-family-doctors/

- Niehaves, B., & Plattfaut, R. (2014). Internet adoption by the elderly: Employing IS technology acceptance theories for understanding the age-related digital divide. European Journal of Information Systems, 23(6), 708–726. doi: https://doi.org/10.1057/ejis.2013.19

- Nussbaum, M. C. (1999). Sex and social justice. Oxford University Press.

- Nussbaum, M. C. (2003). Capabilities as fundamental entitlements: Sen and social justice. Feminist Economics, 9(2–3), 33–59. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/1354570022000077926

- OECD (2016). Skills matter: Further results from the survey of adult skills. https://www.oecd.org/skills/skills-matter-9789264258051-en.htm

- Office for National Statistics (2019). Exploring the UK's digital divide -- Office for National Statistics. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/householdcharacteristics/homeinternetandsocialmediausage/articles/exploringtheuksdigitaldivide/2019-03-04

- Park, S., & Humphry, J. (2019). Exclusion by design: Intersections of social, digital and data exclusion. Information, Communication & Society, 22(7), 934–953. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2019.1606266

- Pew Research Centre (2014a). Attitudes, impacts, and barriers to adoption Pew Research Center. https://www.pewinternet.org/2014/04/03/attitudes-impacts-and-barriers-to-adoption/

- Pew Research Centre (2014b). Older adults and technology use. https://www.pewinternet.org/2014/04/03/older-adults-and-technology-use/

- Phillipson, C., White, S., & Hammond, M. (2014). Old moat: Age-friendly neighbourhood report (p. 124).

- Sen, A. (1984). Resources, values, and development. Harvard University Press.

- Sen, A. (1999). Development as freedom. Alfred Knopf.

- UK Cabinet Office, & UK Government Digital Service (2014). Government digital inclusion strategy. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/government-digital-inclusion-strategy/government-digital-inclusion-strategy

- UK Cabinet Office, UK Government Digital Service, & Rt Hon Lord Maude of Horsham (2012). GOV.UK: Making public service delivery digital by default. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/launch-of-gov-uk-a-key-milestone-in-making-public-service-delivery-digital-by-default

- van Deursen, A. J., & van Dijk, J. A. (2014). The digital divide shifts to differences in usage. New Media & Society, 16(3), 507–526. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444813487959

- Wang, H., Zhang, R., & Wellman, B. (2018). Are older adults networked individuals? Insights from East Yorkers' network structure, relational autonomy, and digital media use. Information, Communication & Society, 21(5), 681–696. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2018.1428659

- White, S. (2018). The greater part: How intuition forms better worlds. In B. Lord (Ed.), Spinoza's philosophy of ratio. https://edinburghuniversitypress.com/book-spinoza-039-s-philosophy-of-ratio.html

- White, S., & Hammond, M. (2018). From representation to active ageing in a Manchester neighbourhood: Designing the age-friendly city. In Age-friendly cities and communities: A global perspective (pp. 193–210).

- World Health Organization (2007). Global age-friendly cities: A guide. World Health Organization.