ABSTRACT

Studies suggest a growing interdependence between journalists and Twitter. What is behind this interdependence, and how does it manifest in news texts? We argue that social media platforms (and Twitter in particular) have situated themselves as purveyors of legitimated content, a projection that journalists have not fully challenged and at times abetted. Instead, journalists rely on these platforms both for access to powerful users and as conduits to surface the words of ‘ordinary people.’ This practice treats tweets more like content, an interchangeable building block of news, than like sources, whose ideas and messages must be verified. Using a corpus of U.S. news stories with tweets in them, we provide empirical evidence for our argument of the power of platforms to legitimate speech and shape journalism. This study illuminates journalists’ role in transferring some of the press’s authority to Twitter, thereby shaping the participants in and content of public deliberation.

Introduction

In the years following the 2016 US presidential election, government officials, the public, and scholars alike have been interested to know the extent of disinformation campaigns and their effects on media and public discourse. US investigations found complex apparatuses operated by foreign powers designed to sow discord and confusion (United States of America v. Internet Research Agency et al., Citation2018). One of these, Russia’s Information Research Agency, was particularly successful. This agency created hoax Twitter accounts to comment on American politics, several messages from which were actually amplified by American journalists, including in many of the country’s most respected news outlets (Lukito et al., Citation2020). It’s one thing if unsuspecting citizens were led to believe or pass along IRA messages, but what about the journalists? How could it be that the very people expected to act as a first line of defense against falsehood, those who hold verification as a core part of their professional identity (Kovach & Rosenstiel, Citation2007), could be duped by these hoax tweets?

One possibility is that the disinformation campaign was so highly sophisticated and successful at manipulating markers of identity and cultural competence that the accounts appeared personally authentic (Xia et al., Citation2019). In other words, influences external to journalism and indeed American politics were so powerful that journalistic routines of verification were overcome. Another possibility, however, is that recent internal changes in journalistic practices created the opportunity for just such a deception. For roughly a decade now, scholars have studied the relationship between journalism and social media (for a review, see Lewis & Molyneux, Citation2018). This work suggests there is a growing mutual dependence, especially between journalists and Twitter, with profound implications for public information flows and, by extension, democracy as practiced in Western nations. This study looks for markers of that dependence and attempts to explain its nature.

We argue that journalists have come to treat tweets more like content, an interchangeable building block of news, than like sources, whose ideas and messages must be subject to scrutiny and verification. Sources are interrogated; content, on the other hand, is simply reproduced. This treatment of sources is dictated by the journalistic values of verification and independence, while the treatment of content is tied to journalists’ habit of externalizing responsibility for information as a way of performing objectivity (Tuchman, Citation1980). This distinction between source and content should be manifest in how journalists present tweets in news reports. Content treatments would reproduce information in tweets without visibly questioning its provenance or providing any further evidence of its legitimacy. Turning to a dataset of hundreds of US news stories containing tweets, we seek evidence to inform this argument. Using a grounded theory approach, our analysis of this corpus builds an evidence-based argument about how journalistic products bear the marks of authority signaling that legitimate Twitter.

Such a shift in the locus of authority from journalists to Twitter would have profound implications for how we understand journalism and its role in society. Platforms already have amassed control of distribution, monetization, and audience measurement to such an extent that journalistic independence and accuracy are compromised by virtue of their dependence on this infrastructure (Van Dijck et al., Citation2018). If in addition to this Twitter short-circuits journalistic processes of verification, there are clear drawbacks for the information ecology. Beyond this, an outsized influence over sourcing and content decisions would compound the longstanding criticism of journalism that it focuses too heavily on certain voices, usually those of powerful white men, thereby producing a skewed view of the world (Gitlin, Citation1980; Hall et al., Citation1978). If Twitter has authority over news, a similar problem exists but with a different cast of characters: those who are present on Twitter and adept at leveraging its affordances to generate attention, a group that is demonstrably different from society as a whole (Wojcik & Hughes, Citation2019). By influencing who can speak and whether their speech is interrogated before amplification, this shift in journalistic practice has the potential to shape the participants in and the content of public deliberation.

Sources of news and information in journalism

Journalism’s reliance on sources is one of its defining characteristics. A reliance on primary sources is what distinguishes journalism from opinion and advocacy on the one hand (no or few external sources) and aggregation and hearsay on the other (secondary sources, or those at a further remove from information; see Coddington, Citation2019). Indeed, journalists must rely on sources because of the asymmetries in knowledge that exist between these two groups (Patterson, Citation2013) – journalists’ sources almost always know more about the subject at hand than the journalists themselves, and so journalists must find out what their sources know. The means for obtaining this information have varied over time, but have traditionally included interviews, written communication, and the exchange of documents. In all this, a journalist – and her journalism – was only as good as her sources, and a key part of a journalist’s value is her ability to find and cultivate these sources. Perhaps even more important than identifying sources is the work of verifying the information sources provide. Indeed, verification is so central to journalism that it has been called journalism’s ‘essence’ (Kovach & Rosenstiel, Citation2007, p. 79).

So, it is with some dismay that scholars have noted journalists’ increasing reliance on information subsidies, or the knowledge and story suggestions offered by public relations professionals (Berkowitz & Adams, Citation1990). This worry is based on the assumption that, at least in some cases, journalists might take and use the information provided to them without subjecting it to traditional journalistic processes of verification. That is, because the information did not originate from a journalist’s chosen source, or as the result of journalistic discovery, it may be able to short-circuit journalistic processes. This, of course, would stand to compromise journalists’ independence and their ability to function as a fourth estate (Lewis et al., Citation2008) – a possibility that now seems increasingly likely (Van Dijck et al. Citation2018). A relatively newer form of information subsidy comes via social media, where journalists, their sources, and their audiences mingle and navigate hybrid flows of information (Chadwick, Citation2017). This new mix has tipped the balance of power between journalists and their sources (Broersma & Graham, Citation2018), changing the ways they interact and the kinds of information that appears in journalistic products.

Of particular interest among journalists is Twitter, a social media platform that has been actively developed with news in mind (Pierce, Citation2015) and to which journalists have flocked (Willnat & Weaver, Citation2018). It was originally hoped that journalists’ use of Twitter would have democratizing effects on the voices present in news discourse (Broersma & Graham, Citation2013). While journalists do use Twitter as a means of finding vox populi (Anstead & O'Loughlin, Citation2014; McGregor, Citation2019; Tworek, Citation2018), studies have found that journalists’ use of Twitter as a source does not upend traditional source hierarchies (Moon & Hadley, Citation2014; Paulussen & Harder, Citation2014; Von Nordheim et al., Citation2018). That is, public officials and elite voices exert influence over news on Twitter much the way these voices have dominated other forms of public discourse. This provides mutual benefits for journalists and public officials: The officials are able to easily provide information subsidies and attempt to shape news coverage, and journalists have come to rely on Twitter for easy access to both public officials and laymen. This has been characterized as a shift away from ‘structured sources,’ such as press releases and in-person briefings, and toward ‘unstructured’ pieces of information, such as tweets (Lecheler & Kruikemeier, Citation2016). At the time, Lecheler and Kruikemeier found that journalists were still somewhat reluctant to quote directly from social media, but in the last few years, there have been significant changes in perceptions of authority and legitimacy, as well as a global uptick in sourcing from social media (Von Nordheim et al., Citation2018).

Authority and legitimization

Journalistic authority is not derived via a credential or certification. It is not tied to a particular body of knowledge. It comes instead from continuous effort and repetition of journalistic forms, practices, and discourses (Carlson, Citation2017; Zelizer, Citation1992). Journalists begin to have authority when their norms come to be accepted by audiences (Robinson, Citation2007) and are seen as meeting professional standards (Tong, Citation2018). That is, to the extent journalists have a reputation for truthtelling, they have authority (Karlsson, Citation2011). The key here is that journalists and journalism do not inherently possess authority over current events or information about public affairs. Rather, they must continuously make claims on this authority by performing it (Carlson, Citation2017). These performances are part practice, part discourse – these two elements together define journalism’s narratives about authority, eventually becoming accepted as the norm for both journalists and their audiences (Vos & Thomas, Citation2018).

This study sets aside questions of identity and discourse to focus on the practices that play a role in defining journalistic authority and legitimacy. These comprise conventions of news forms and sourcing practices, two of the way’s journalistic performances signal authority. Journalists’ selection of sources conveys to the audience notions of who has the authority to speak, or which voices are important to hear (Eldridge, Citation2017). The words and forms that present those sources to the audience are equally important, because they ‘freeze into place a set of particular authority relations between journalists and others’ (Carlson, Citation2017, p. 56). In short, journalists’ authority is based on demonstrating the process they went through to acquire the knowledge presented in their reports. They do the labor of vetting sources, interrogating them, verifying information, and finally communicating it – but audiences don’t know whether journalists have in fact done this work unless they can see evidence of it in journalists’ reports. Carlson (Citation2017) argues that journalists have no authority unless they consistently demonstrate it in this way.

Together, these questions of sourcing and form establish one corner of journalists’ authority and legitimacy and suggest to audiences who – and what – else, by proxy, possess legitimacy. This study therefore interrogates journalistic form and practice in sourcing information via Twitter in an attempt to understand what journalists see as legitimate and what legitimating signals they send to audiences. In theory, changes in journalistic forms could shift perceptions of authority over information. Given Twitter’s central role in both journalism and politics, it is likely to reflect strongly on these questions of authority. Yet scholarly attention is only now beginning to focus on the dynamics of power at play between the press, as an institution, and Twitter, as a company. While early takes on social media suggested that it might empower journalists and their audiences, it’s not clear that the power dynamics favor either of these groups (Jensen, Citation2017). Journalists’ reliance on Twitter in constructing and relaying the news legitimates not only individual tweets but also the platform itself as a purveyor of news and information.

The legitimating power of platforms

Social media platforms, and Twitter in particular, have purposively situated themselves as purveyors of legitimated news content (c.f. McGregor, Citation2019) – a projection that journalists have not fully challenged, and have at times abetted. Journalists rely on Twitter both for access to powerful users and as a conduit to surface and amplify the words of ‘ordinary people.’ What is it about Twitter that so strongly suggests to journalists that it is an authoritative source for news? One possibility is the proximity to power. Every member of the US Congress is on Twitter (Straus et al., Citation2013), and as a result, efficient access to these leaders is one of Twitter’s key benefits for journalists. Following Obama’s use of Twitter as the first ‘social media president,’ tweets practically replaced press briefings in the Trump administration. It is through Twitter that journalists primarily encounter and interact with elected officials (Molyneux & Mourão, Citation2019; Usher et al., Citation2018), who use Twitter as a de facto press release (Kreiss et al., Citation2018).

Another signal of Twitter’s legitimacy is the ubiquity of other journalists and news outlets on the platform. This is perhaps no surprise given the platform’s focus on immediacy, its affordances for brevity, and the genres of communication that developed there promoting concise wit and sarcasm (Lawrence et al., Citation2014). Twitter use has remained widespread among journalists (Armstrong & Gao, Citation2010; Holton & Lewis, Citation2011; Molyneux, Citation2015; Vis, Citation2013; Willnat & Weaver, Citation2018). Because so many journalists and their sources are on Twitter and interact with each other there, there are positive network externalities, heightening Twitter’s impact on newsmaking. This impact even extends to journalists’ news judgment – journalists who use the site often regard tweets as strong indicators of newsworthiness (McGregor & Molyneux, Citation2020).

The confluence of both politicians and journalists on Twitter makes the platform itself the floor for the symbiotic dance of press-state relations (Sparrow, Citation1999). It is through Twitter that statements from elected officials are taken up by the press, providing those statements with the stamp of credibility. Similarly, it is through Twitter that the press, as inherently ‘uncertain guardians,’ gains visible proximity and access to those in power, shoring up their own institutional power and authority (Sparrow, Citation1999; Tuchman, Citation1980). In this way, Twitter is a central platform for the construction of and symbolic deployment of political power.

The question underlying much of the research cited here, and leading up to this study as well, is how this reliance on Twitter (by both journalists and their sources) changes news content, forms, and practices in ways that reflect and perpetuate this rebalancing of power. Chadwick et al. (Citation2020) suggest that repetitions of journalistic form come to structure public debates by indicating who has power and who does not. In this case, building on Downey & Toynbee (Citation2016), we expect that those less skillful at using Twitter are marginalized in news coverage, and therefore in actual public debate. The opposite would also be true: those more skilled in Twitter use are given disproportionate attention. Again, drawing from Chadwick et al. (Citation2020), this defines the losers (the information have-nots) as those not plugged into Twitter. We argue that such changes in journalistic practice have a noticeable effect on journalistic authority and send signals about legitimacy – whose voices are legitimate sources of information, through what channels they tend to flow, and by which processes they become legitimate pieces of newsworthy information. When these signals all point toward Twitter as an ‘assumed authority,’ it is that platform – not the politicians and journalists who rely on it – that gains and subsequently projects a sense of legitimacy.

Methods

In order to examine how tweets are treated in stories, we built a corpus of news stories with tweets in them. We sought a broad and logically generalizable sample to represent the range of professional journalism currently available. We then conducted a close reading of this sample, inductively looking for ways in which journalists signal authority relating to Twitter. A qualitative approach was chosen because authority signaling is presumed to be a latent, rather than explicit and overt, process (Chadwick et al., Citation2020; Carlson, Citation2017) so this analysis seeks to understand what subtexts related to Twitter drive each news report. The analysis was conducted at four analytical levels corresponding to words, tweets, sources, and stories.

Data

First, we chose to examine one year of data. We gathered stories published in 2018, which not only was the most current for which a whole year of data would be available at the time of our collection. but also, as a mid-term election year, provides a broad amount of public affair news. Second, we chose keywords that would restrict our results to public affairs. We chose the top five issues of importance to Americans in 2018 (Pew Research, Citation2019a), which were the economy, health care, terrorism, education, and social security. Next, we used a series of keywords to help us identify stories that contained tweets. Drawing from previously published work (Rony et al., Citation2018) and our own iterative search, those words were: tweeted, tweets, ‘to Twitter’, retweet, ‘in a tweet’, ‘to tweet’, ‘tweet from’, ‘wrote on Twitter’, ‘said on Twitter’, and ‘according to a tweet’. Finally, we wanted our search to be expansive enough to include multiple types of outlets, but limited to knowable outlets. Though MediaCloud provides access to stories from tens of thousands of media sources, we searched within these for sources identified by the Pew Research Center in its State of the News Media 2018 report (Pew Research, Citation2019b). We searched for cable news (3 sources), digital-native publishers (36 sources), magazines (14 sources), network TV (3 sources), newspapers (44 sources), and public broadcasting (2 sources). In sum, the data stems from 102 news outletsFootnote1 (see Appendix A for a complete list). In all, our query yielded more than 23,000 news articles. We subjected a sample of these stories to detailed textual analysis, and that sample was built as a constructed year. We broke the sample down by month and chose 31, 30, or 28 stories at fixed intervals so these stories would be spread across the month. Our constructed year consists of 365 articles.

Analysis

The goal of this analysis is to observe what overall impression of Twitter and its relationship to journalism and information is conveyed to the audience in a news report. With this in mind, we look for evidence of how power is legitimized, thereby becoming authority, at the four structural levels outlined below. We follow an integrated approach, bridging inductive categories emerging from a textual analysis while integrating them into the structural schema informed by existing literature on journalism (Luker, Citation2009). The results stem from a process in which we each analyzed the stories, discussed together the themes we identified, and reached consensus.

Words

Latour and Woolgar (Citation1986) suggest that language can have various ‘modalities’ expressing varying levels of certainty. By this they mean the various conversational qualifiers, modifiers, and adornments that can enhance or diminish what might otherwise be a simple statement of fact, or a quote. In the case of references to Twitter in news stories, the main question is whether the tweet is left to speak for itself. Are there any qualifiers or modifiers attached to the tweet? Are any adjectives used to describe the source or the tweet? Overall, do the words surrounding the tweet provide any additional context or hint at varying levels of certainty?

Tweets

It’s also important to examine how the tweet is presented in the story itself, whether embedded directly or referred to in the text, with or without the qualifiers mentioned above. Also, does the story make any attempt to explain Twitter or how the source uses it? What kinds of messages in tweets are chosen for inclusion or quotation in news stories? Do these tweets come from verified users? Finally, it would be important to note whether the news story refers to the tweet itself as a news object or to the source, who made a statement via Twitter.

Sources

We observe whether journalists use tweets in service of news sources or the other way around. Are there multiple means of hearing from the same source (i.e., the person whose tweet was included in the news story)? Whose tweets are chosen for inclusion? Are there patterns in whose are quoted, paraphrased, or embedded directly? Furthermore, are there patterns in how tweets from different types of sources (esp. elites vs. non-elites) are presented in news stories?

Stories

The key question here is whether the story at hand would exist without Twitter, using different sourcing practices instead. That is, did a tweet or a Twitter phenomenon spark the news story in the first place? Or at a broader level, is Twitter the frame or the setting for this news story?

Together these questions help us determine whether journalists treat tweets more like content or more like a source. ‘Content’ in this sense is meant to indicate a commodity, something that comes pre-processed, pre-packaged, and ready for consumption by journalists and their audiences. ‘Source’ in this sense is meant to suggest a font of information that would naturally be subjected to traditional journalistic practices of interrogation and verification, thereby tasking journalists themselves with the processing necessary to turn the source’s information into story material fit for audience consumption. We’ve chosen a qualitative analysis precisely because usage will fall on a spectrum rather than in binary categories – journalists are likely to mix these approaches to varying degrees depending on the story, source, and the tweet itself. This study is designed to capture, at the aggregate level, the ways in which journalists treat tweets more like content or more like sources (see ).

Table 1. Depending on the story, the source, and the tweet itself, journalists may treat tweets in news stories more like content or more like sources.

Results

Across publications and story types, journalists’ use of tweets in news stories appears to be part of standard practice. This sample was selected to include only stories with tweets in them, so our data cannot speak to how common or widespread the practice is, but it’s worth noting here at the outset how deeply embedded Twitter is in news reporting practices. Years earlier, news reporters might have accompanied tweets in stories with explanations of what Twitter is (e.g., ‘a microblogging service,’) or noted how it works, or even used explanatory language such as ‘posted on Twitter’ or ‘in a social media posting.’ This language is now practically non-existent, in favor of treatments such as ‘tweeted’ or ‘said on Twitter.’ There is an implicit assumption that readers not only know what Twitter is but understand why tweets would be included in a news story. We also find no explanations as to why tweets are being used rather than seeking original quotes via interview or some other means. Journalists’ language and signaling to readers indicates that Twitter and tweets are normal, commonplace means of gathering information and hearing from sources, especially official ones. That is, journalists assume that readers understand any context or qualifications that might need to be made regarding information obtained via Twitter, and so offer none of this themselves. Regardless of whether this assumption holds up, it is evidence of a relatively stable sense among journalists that Twitter occupies a position of assumed authority and legitimacy.

The sections that follow break down what this assumption of legitimacy looks like in practice, from a reader’s perspective observing usage of tweets in news stories. Observations are organized in order of scope, from word-level concerns to story-level concerns. This is followed by a discussion and integration of key findings.

Words

We examined which words journalists used in connection with a tweet in a news story, noting any qualifiers, modifiers, or contextual signals contained within one or a few words. As noted earlier, by far the most common treatment of tweets is to say a person ‘tweeted,’ followed by ‘said on Twitter.’ These two treatments almost always appear with a time reference (e.g., ‘tweeted Thursday that’). See . This stands in contrast to journalistic practice (including in this sample) when referencing an interview, in which case journalists commonly write ‘said’ without mentioning when the interview occurred. It is not unheard of for journalists to situate an interview quote in time – especially when it is not at all recent – but with tweets, this is standard practice. By far the most common bit of contextual information associated with a tweet is the time at which it was sent. This was usually the day of the week, but sometimes included the time of day (e.g., ‘Wednesday afternoon,’ ‘late Sunday night’). There are a number of reasons journalists might include a time reference along with a tweet. It may indicate the immediacy of the information, which has long been considered a primary news value among journalists. It may also be an attempt to signal the provisional nature of the information, apropos of the ephemerality of social media posts in general. Finally, it could be that journalists consider the time a tweet was sent to be valuable, relevant information for readers in interpreting the tweet itself.

Figure 1. The most common way to refer to a tweet is to say that its author ‘tweeted’ or ‘said in a tweet,’ often accompanied by an indicator of when the tweet was sent. The link in the Sun-Sentinel story goes not to the tweet but to another Sun-Sentinel story about the tweet.

A second notable trend is the practice of characterizing the emotional effect of the tweet or series of tweets. Especially when there was a series of tweets (threaded or not, but sent in sequence, within a perceived single session, or surrounding a single issue), journalists regularly characterized the tweets as constituting ‘a tirade,’ ‘lashing out,’ or ‘ranting,’ for example. Journalists described a tweet as a person ‘complaining,’ ‘agreeing,’ ‘threatening,’ or as displaying various emotions (e.g., ‘cage-ily,’ ‘shouted,’). Journalists did not do this with every tweet, but it was common to observe in cases of a series of tweets, especially those associated with President Trump. Again, the prevalence of this treatment seems to be above and beyond standard journalistic practice of objectivity, and occurs more commonly with tweets than with other forms of source attribution. A ready explanation for this would be the affectively charged, emotionally valenced nature of Twitter itself (Berger & Milkman, Citation2012; Lawrence et al., Citation2014; Papacharissi, Citation2015), which appears to be in turn shaping the coverage of tweets and ultimately the news stories themselves, as journalists treat Twitter as a legitimated information platform.

We also looked for whether any language was used to contextualize or qualify the authors of the tweets used in news stories. Because the authors of tweets used in news stories were overwhelmingly public officials or other elites, the only such language used was the person’s title. A notable exception was the case of relatively anonymous Twitter users whose tweets were included in the story not because of who they are but because of what they said. Groups of people were referred to as ‘friends,’ ‘supporters,’ ‘critics,’ and more, usually then followed by one or a few exemplar tweets from ‘someone’ in this group. We return to this phenomenon when considering sources, but for now we note that journalists used relatively limited (i.e., single word) and generalized language to contextualize authors of tweets used in news stories.

As a whole, journalists spent precious few words adding context, qualifiers, or modifiers to tweets in news stories. The most common was a time reference; less common but noticeably present was a tendency to characterize bodies of tweets with emotionally affected descriptions. In general, journalists let the tweets speak for themselves.

Tweets

Turning our analysis to tweets included in news stories, we observed how these tweets were treated, including means of referencing and presenting tweets, what kinds of tweets were included, and how the tweet was situated within the story as a whole. First, we noted whether the story referred to the tweet (as a news object worthy of examination or inclusion on its own) or the tweeter (a person whose statements are worth hearing, regardless of how they are obtained). A clear pattern emerged: journalists referenced the tweeter when the person was a public official or other elite member of society, and they referenced the tweet when its author did not have this status. Overall, because elites were the most commonly used sources, most tweets in news stories were connected with a reference to the tweeter rather than the post itself.

A key finding is that journalists are highly inconsistent in how they present tweets in news stories. It was impossible to detect any clear pattern. Some tweets were quoted in full, some partially, and others were paraphrased and not quoted; some were linked to, some were embedded, and some neither. See . These differences even appeared within the same story, and to some extent they mirror the ways journalists have traditionally quoted sources (with full/partial quotes, paraphrasing, and pull quotes). To give a few examples, one story from CNN quotes a tweet from Trump in full, and then embeds it, essentially duplicating the information in the story; later, it provides a partial quote of a Trump tweet and then embeds the full tweet. Another story from Politico paraphrases one tweet from an EU negotiator and links to it; then describes the photo in a tweet from UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson, and embeds the tweet; then quotes a second tweet from Johnson and links to it. Probably the most common format is for journalists to treat the tweet as a statement or other document, simply quoting from it without a link or embed. This was especially common among traditional, mainstream publications. This is obviously the preferred format for wire stories, in order to keep the story text clean and unencumbered by HTML code. But this format was also common among local news outlets and was used even by some digital native outlets.

Figure 2. A CNN story says a source ‘tweeted,’ quotes the tweet in full, links to it, and then embeds it.

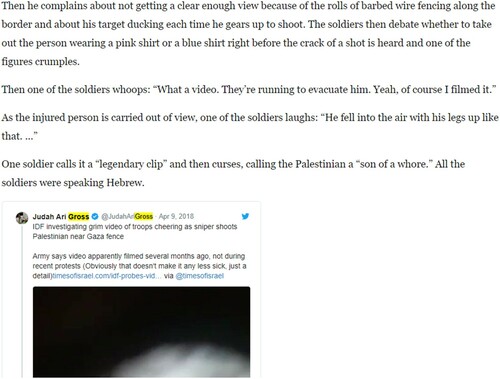

Another regularly occurring format for tweets in news stories is to use them like a sidebar. That is, tweets are embedded but not referenced explicitly in the story text. See . These tweets are, however, conceptually linked to the story, essentially functioning as supplementary material or a demonstration of a story aspect. It was much more common to see this presentation among digital native outlets, and much less common to see this presentation among traditional, mainstream outlets. Overall, however, the only consistent finding is inconsistency in how journalists present tweets and information in them.

Figure 3. This Washington Post story describes the contents of a video without ever saying where the video came from, then embeds a tweet from a Times of Israel reporter that contains the video but still doesn’t say where it originated.

A few trends were notable related to the content of tweets presented in news stories. As mentioned earlier, only an inconsistent subset of tweets were embedded, but tweets that were embedded commonly contained visual media, with or without accompanying text. This is presumably the simplest, most transparent means of reproducing the visual media from the tweet in the news story. Also, many of the tweets selected for inclusion in news stories were emotionally valent, an unsurprising finding given what we know about the nature of Twitter and social media in general, as well as journalism’s reliance on (particularly negative) emotion to raise attention and awareness.

In all of this, it is important to note once again that tweets were presented without additional context or explanation about the platform where they were posted, how it functions, how the tweets were obtained, and so on. Tweets in news stories were given the same treatment as official statements, reports, and other documents. The tweet is treated as an object published on a legitimate platform by a verified speaker that needs no further justification.

Sources

When considering sources included in these stories, we noted whether the tweet was the only means of hearing from the source. In most cases, the tweet (or tweets) was the only means of information gathering from the source in the story, with two notable exceptions. The first is President Trump, whose tweets, interviews, press briefings, and informal encounters with reporters are all treated as equally relevant and equally legitimate journalistic objects representing presidential statements. Thus, news stories in which Trump is a source routinely contain both interview or briefing quotations and tweets, and treat these as roughly interchangeable. The second exception is when the story is about a person (as opposed to an event, policy, decision, etc.), in which case Twitter is one of several means of understanding that person. Overall, however, the selected tweet is usually the only way that readers hear from that source within the span of a single story. Again, this is probably a matter of access and convenience. If journalists attempted to verify with the author every statement published in a tweet before including it in a news story, news production worldwide would grind to a halt.

The people whose tweets are used in news stories come in three varieties: officials or elites, someone experiencing a viral moment (i.e., widespread but short-lived attention on social media), and anonymous observers, commenters, or participants. As other research has shown, tweets from elite sources (e.g., public officials) are still the most common tweets included in news stories (Lecheler & Kruikemeier, Citation2016; Von Nordheim et al., Citation2018). Public officials react to and drive public discourse in carefully managed, image-conscious ways, a recent iteration of which is via Twitter (Kreiss et al., Citation2018); Twitter then becomes a journalistic supermarket that offers journalists one-stop-shopping for official statements.

Individuals at the center of viral moments on social media are a second type. In these cases, the framing is usually social media discourse itself; that is, the individual tweeted something revealing/humorous/offensive/inspiring, the message traveled widely and received much attention, and journalists write a story about this attention. With few exceptions, this is the only case in which a non-public/non-celebrity individual’s tweets are included in a news story, where that individual is also described, interviewed, or profiled in any meaningful way.

Relatively anonymousFootnote2 individuals are included more often, but with much less transparency about who they are or how their tweets were selected. Often these people are called ‘some’ or ‘others,’ and even when individual comments are singled out, journalists use the words ‘someone’ or ‘a user’ as the only description of the person given. Regularly, these tweets are included in a compendium without presentations of individual tweets, further diminishing the value of any single tweet (or author).

In summary, we see no evidence that sources whose tweets are quoted in news stories are also contacted by other means to expand upon, explain, contextualize, or otherwise verify the information in the tweet. In this case, lines between content and source are blurred as the tweet itself becomes both. This may even make sense in the case of public officials who have made it clear they use Twitter as a public information instrument. But in the case of other individuals, it’s unclear how this practice could comport with journalistic ideals of verification.

Stories

A final point of analysis was whether the news stories that included tweets were occasioned by the tweet itself. In other words, is Twitter the frame for the story? Or, would the story exist (with different sourcing and presentation) if Twitter did not? Quite often, Twitter is the frame for the story. This is especially the case with President Trump, whose tweets were featured in more than half the stories in the sample; frequently, the information in his tweet is the lead of the news story. But also, in many other cases, especially those where non-elite voices appear, the setting for the story (if not entirely its ramifications) is Twitter. As for whether these stories would exist without Twitter, that is hard to answer definitively because it engages a counterfactual. Twitter does exist, and journalists routinely rely on it as a source of information. But given the observations undertaken here, it is safe to say that Twitter’s deep integration into news routines and structures has shaped – in one way or another – the news we see, thereby privileging Twitter users and the platform itself with the power to shape the news, and therefore public discussion.

Discussion

The relationship between journalism and Twitter has received much scholarly attention in an effort to understand how this relationship shapes the information environment. This study extends that discussion by demonstrating the ways that journalists’ use of tweets in news stories signals to each other and to readers that Twitter is an authoritative, legitimated source of information. The implications for journalistic practice are profound – everything we know about journalism suggests sources should be interrogated, but there is no evidence of this process when journalists present tweets in news reports. Beyond this, the effect of positioning Twitter as an information authority is to give the platform additional power to shape news and override key journalistic values (Van Dijck et al., Citation2018).

Our findings relating to practice may be summarized with two key points. First, journalists expend very few words explaining or qualifying tweets, suggesting that a tweet is able to speak for itself. As a result, journalists assume the role of discovery and amplification rather than that of independent verification, which constitutes a significant shift in journalistic values and roles. In many cases, they apparently pass along the tweets as if they were a police report, accepting the author’s words as presented. Treating tweets as content in this way suggests they need no further journalistic processing. Journalists can simply deflect any questions to the original author by claiming they’ve been transparent in process, thus performing what Tuchman (Citation1980) called a strategic ritual of objectivity. The methods employed here are limited in that we cannot determine journalists’ motivations or reasoning for behaving as they do. Future studies might present this evidence to journalists and ask for their explanations, but we would expect them to fall along the lines already presented in scholarly work: difficult economic and cultural conditions for journalists limiting their access and reach lead them toward shortcuts as a matter of expediency (Brandtzaeg et al., Citation2016; Coddington, Citation2019; Vobič & Milojević, Citation2014). Regardless of whether audiences become accustomed to this shift in form and authority, it’s not given that they will also perceive the use of social media sources positively (c.f. Dubois et al., Citation2020).

Second, journalists appear to be continually experimenting with the formatting and presentations of tweets in news stories. One lens for looking at these formatting and presentation concerns is control. Journalists conceivably might choose to use a partial quote in order to retain the ability to frame the information as they wish, rather than adopting the tweeter’s frame wholesale. But this logic is defeated as journalists often use partial quotes in conjunction with hyperlinks to or embeds of the full tweet. Also, journalists might wish to quote a tweet (whether partially or in full) rather than linking to or embedding it because tweeters have the ability to delete or restrict access to these posts. Thus, access to the information behind a link or within an embedded post is essentially out of journalists’ hands unless they capture that information themselves. If this is the logic, though, a screenshot may better serve the purpose, especially in the case of tweets containing visual media. One can only imagine the thousands of stories now containing broken links to Trump tweets, inaccessible in the wake of his January 2021 suspension from the platform. It remains unclear why journalists use full quotes, partial quotes, or paraphrased information, and why they choose to link to tweets, embed them, or to do neither, but the implication is that platform infrastructure continues to shape the practice in ways that privilege the platform. Future studies might focus on this experimentation with the aim of understanding how journalistic presentation standards are determined, what the technical limitations are, and how experimentation in form affects audiences’ impressions of credibility and authority (c.f. Dumitrescu & Ross, Citation2020).

This study provides evidence that journalistic authority is not only created by journalistic forms but may also be transferred by them to entities outside journalism. Journalists’ treatment of tweets largely as content suggests the existence of a feedback loop that perpetuates Twitter’s centrality in the news ecosystem. As Twitter becomes associated with news, journalists and elites turn to it to react to news events and gather information. This in turn almost compels journalists to use tweets as information sources in their stories, all while lending their own legitimacy and interpretation, thereby increasing the likelihood that elites will use it for future information releases, the likelihood that journalists will return to receive them, and the likelihood that audiences become accustomed to seeing Twitter in news stories. This leads to the normative question of whether it is desirable to afford Twitter such a privileged position in the information ecosystem. Van Dijck et al. (Citation2018) argue that relying on platform infrastructures privatizes public values (such as accurate information about public affairs). This privatization occurs because realization of the public values depends upon individuals’ (mis)use of the platform. This has previously been framed as a question of asserting or maintaining expert control over journalistic content, but the greater issue is whether people, individually and collectively, can clear the bar for realizing these public values. The recent proliferation of misinformation suggests not.

In the end, Twitter and its algorithmic presentation of ‘What’s happening?’ are presented in journalism as having assumed authority over news and information. Algorithms, of course, have their own knowledge logic, driven by the ‘proceduralized choices of a machine, designed by human operators to automate some proxy of human judgement’ (Gillespie, Citation2014, p. 26). In journalism, Gillespie suggests these algorithmic logics compete with editorial logics as means of newsgathering, pitting computational objectivity against human subjectivity (Carlson, Citation2019). What we find here suggests that in the work of seeking access to and information from elite sources, algorithmic logics have come to supplant editorial logics, altering the epistemology of newsgathering in ways that challenge journalists’ claims to authority, journalistic independence, and the public’s exposure to accurate information. Journalists are reduced to amplifying and interpreting (as opposed to seeking and verifying) information, sharing authority over information with a social platform that itself is seen as a legitimate news source, if not a distinct journalistic entity. Considering these platforms have inconsistenly and belatedly – if at all – defended accurate information as a public good, this shift raises important questions for democratic societies.

Supplement_Material.docx

Download MS Word (51.9 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Logan Molyneux

Logan Molyneux is an assistant professor of journalism at Temple University who studies how journalists use social media [email: [email protected]].

Shannon C. McGregor

Shannon C. McGregor is an assistant professor in the Hussman School of Journalism and Media and a senior researcher with the Center for Information, Technology, and Public Life, both at the University of North Carolina, who studies political communication, social media, and public opinion [email: [email protected]].

Notes

1 Our list varies slightly from the Pew list because five outlets were not available via MediaCloud (arkansasonline.com, chicagotribune.com, latimes.com, sfgate.com, sbnation.com) and we did not query one non-English outlet (elnuevodia.com).

2 ‘Relatively’ is used here to indicate that no contextual or descriptive information about the person is given, such as a title, hometown, age, occupation, etc. But they may not be completely anonymous when the person’s Twitter handle or profile picture is visible in the story.

References

- Anstead, N., & O'Loughlin, B. (2014). Social media analysis and public opinion: The 2010 UK general election. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 20(2), 204–220. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12102

- Armstrong, C. L., & Gao, F. (2010). Now tweet this: How news organizations use Twitter. Electronic News, 4(4), 218–235. https://doi.org/10.1177/1931243110389457

- Berger, J., & Milkman, K. L. (2012). What makes online content viral? Journal of Marketing Research, 49(2), 192–205. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmr.10.0353

- Berkowitz, D., & Adams, D. B. (1990). Information subsidy and agenda-building in local television news. Journalism Quarterly, 67(4), 723–731. https://doi.org/10.1177/107769909006700426

- Brandtzaeg, P. B., Lüders, M., Spangenberg, J., Rath-Wiggins, L., & Følstad, A. (2016). Emerging journalistic verification practices concerning social media. Journalism Practice, 10(3), 323–342. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2015.1020331

- Broersma, M., & Graham, T. (2013). Twitter as a news source how Dutch and British newspapers used tweets in their news coverage, 2007-2011. Journalism Practice, 7(4), 446–464. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2013.802481

- Broersma, M., & Graham, T. (2018). Tipping the balance of power: Social media and the transformation of political journalism. In A. Bruns, G. Enli, E. Skogerbo, A. O. Larsson, & C. Christensen (Eds.), The Routledge Companion to social media and politics (pp. 89–103). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315716299-7.

- Carlson, M. (2017). Journalistic authority: Legitimating news in the digital era. Columbia University Press.

- Carlson, M. (2019). News Algorithms, Photojournalism and the assumption of mechanical objectivity in journalism. Digital Journalism, 7, 1117–1133. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2019.1601577

- Chadwick, A. (2017). The hybrid media system: Politics and power. Oxford University Press.

- Chadwick, A., McDowell-Naylor, D., Smith, A. P., & Watts, E. (2020). Authority signaling: How relational interactions between journalists and politicians create primary definers in UK broadcast news. Journalism, 21(7). http://doi.org/10.1177/1464884918762848

- Coddington, M. (2019). Aggregating the news: Secondhand knowledge and the erosion of journalistic authority. Columbia University Press. https://doi.org/10.7312/codd18730.

- Downey, J. (2016). Ideology: Towards renewal of a critical concept. Media, Culture and Society, 38(8), 1261–1271.

- Dubois, E., Gruzd, A., & Jacobson, J. (2020). Journalists’ use of social media to infer public opinion: The citizens’ perspective. Social Science Computer Review, 38(1), 57–74. http://doi.org/10.1177/0894439318791527

- Dumitrescu, D., & Ross, A. R. N. (2020). Embedding, quoting, or paraphrasing? Investigating the effect of political leaders’ tweets in online news articles: The case of Donald Trump. New Media & Society, https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820920881

- Eldridge, S. A. (2017). Online journalism from the periphery: Interloper media and the journalistic field. Routledge.

- Gillespie, T. (2014). The relevance of algorithms. Media Technologies: Essays on Communication, Materiality, and Society, 167, 167.

- Gitlin, T. (1980). The whole world is watching: Mass media in the making and unmaking of the new left. Univ of California Press.

- Hall, S., Critcher, C., Jefferson, T., Clarke, J., & Roberts, B. (1978). Policing the crisis: Mugging, the state and law and order. Macmillan International Higher Education.

- Holton, A. E., & Lewis, S. C. (2011). Journalists, social media, and the use of humor on Twitter. Electronic Journal of Communication, 21(1/2), 1–22.

- Jensen, M. J. (2017). Social media and political campaigning: Changing the terms of engagement? The International Journal of Press/Politics, 22(1), 23–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161216673196

- Karlsson, M. (2011). The immediacy of online news, the visibility of journalistic processes and a restructuring of journalistic authority. Journalism: Theory, Practice & Criticism, 12(3), 279–295. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884910388223

- Kovach, B., & Rosenstiel, T. (2007). The elements of journalism: What newspeople should know and the public should expect. Three Rivers Press.

- Kreiss, D., Lawrence, R. G., & Mcgregor, S. C. (2018). In their own words: Political practitioner accounts of candidates, audiences, affordances, genres, and timing in strategic social media use. Political Communication, 35, 8–31.

- Latour, B., & Woolgar, S. (1986). Laboratory life: The construction of scientific facts. Princeton University Press.

- Lawrence, R. G., Molyneux, L., Coddington, M., & Holton, A. (2014). Tweeting conventions: Political journalists’ use of Twitter to cover the 2012 presidential campaign. Journalism Studies, 15(6), 789–806. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2013.836378

- Lecheler, S., & Kruikemeier, S. (2016). Re-evaluating journalistic routines in a digital age: A review of research on the use of online sources. New Media & Society, 18(1), 156–171. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444815600412

- Lewis, S. C., & Molyneux, L. (2018). A decade of research on social media and journalism: Assumptions, blind spots, and a way forward. Media and Communication, 6(4), 11. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v6i4.1562

- Lewis, J., Williams, A., & Franklin, B. (2008). A compromised fourth estate?: UK news journalism, public relations and news sources. Journalism Studies, 9(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616700701767974

- Luker, K. (2009). Salsa dancing into the social sciences. Harvard University Press.

- Lukito, J., Suk, J., Zhang, Y., Doroshenko, L., Kim, S. J., Su, M. H., Xia, Y., Freelon, D., & Wells, C. (2020). The wolves in sheep’s clothing: How Russia’s internet research agency tweets appeared in US news as vox populi. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 25(2), 196–216. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161219895215

- McGregor, S. C. (2019). Social media as public opinion: How journalists use social media to represent public opinion. Journalism, 20(8), 1070–1086. http://doi.org/10.1177/1464884919845458

- McGregor, S. C., & Molyneux, L. (2020). Twitter’s influence on news judgment: An experiment among journalists. Journalism, 21(5), 597–613. http://doi.org/10.1177/1464884918802975

- Molyneux, L. (2015). What journalists retweet: Opinion, humor, and brand development on Twitter. Journalism: Theory, Practice & Criticism, 16(7), 920–935. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884914550135

- Molyneux, L., & Mourão, R. R. (2019). Political journalists’ normalization of Twitter: Interaction and new affordances. Journalism Studies, 20(2), 248–266. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2017.1370978

- Moon, S. J., & Hadley, P. (2014). Routinizing a new technology in the newsroom: Twitter as a news source in mainstream media. Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media, 58(2), 289–305. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2014.906435

- Papacharissi, Z. (2015). Affective publics. In Affective publics: Sentiment, technology and politics (pp. 115–136). Oxford University Press.

- Patterson, T. E. (2013). Informing the news: The need for knowledge-based journalism. Vintage Books.

- Paulussen, S., & Harder, R. A. (2014). Social media references in newspapers. Journalism Practice, 8(5), 542–551. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2014.894327

- Pew Research. (2019a). State of the Union 2019: How Americans see major national issues. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/02/04/state-of-the-union-2019-how-americans-see-major-national-issues/

- Pew Research. (2019b). State of the news media methodology. Pew Research Center. https://www.journalism.org/2019/07/23/state-of-the-news-media-methodology/

- Pierce, D. (2015, October 6). Meet Moments, Twitter's most important new feature ever: Twitter wants to make a Twitter for people who don't get Twitter. Wired. https://www.wired.com/2015/10/meet-moments-twitters-new-feature/

- Robinson, S. (2007). “Someone’s gotta be in control here”: The institutionalization of online news and the creation of a shared journalistic authority. Journalism Practice, 1(3), 305–321. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512780701504856

- Rony, M. M. U., & Yousuf, M. (2018). A large-scale study of social media sources in news articles. arXiv preprint arXiv:1810.13078.

- Sparrow, B. H. (1999). Uncertain guardians: The news media as a political institution. JHU Press.

- Straus, J. R., Glassman, M. E., Shogan, C. J., & Smelcer, S. N. (2013). Communicating in 140 characters or less: Congressional adoption of Twitter in the 111th Congress. PS: Political Science & Politics, 46(1), 60–66. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096512001242

- Tong, J. (2018). Journalistic legitimacy revisited: Collapse or revival in the digital age? Digital Journalism, 6(2), 256–273. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2017.1360785

- Tuchman, G. (1980). Making news. Macmillan.

- Tworek, H. (2018). Tweets are the new vox populi. Columbia Journalism Review. https://www.cjr.org/analysis/tweets-media.php

- United States of America v. Internet Research Agency, et al. (2018). United States district court for the district of Columbia. https://www.justice.gov/file/1035477/

- Usher, N., Holcomb, J., & Littman, J. (2018). Twitter makes it worse: Political journalists, gendered echo chambers, and the amplification of gender bias. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 23(3), 324–344. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161218781254

- Van Dijck, J., Poell, T., & De Waal, M. (2018). The platform society: Public values in a connective world. Oxford University Press.

- Vis, F. (2013). Twitter as a reporting tool for breaking news: Journalists tweeting the 2011 UK riots. Digital Journalism, 1(1), 27–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2012.741316

- Vobič, I., & Milojević, A. (2014). “What we do is not actually journalism”: role negotiations in online departments of two newspapers in Slovenia and Serbia. Journalism, 15(8), 1023–1040. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884913511572

- Von Nordheim, G., Boczek, K., & Koppers, L. (2018). Sourcing the sources: An analysis of the use of Twitter and Facebook as a journalistic source over 10 years in The New York Times, The Guardian, and Süddeutsche Zeitung. Digital Journalism, 6(7), 807–828. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2018.1490658

- Vos, T. P., & Thomas, R. J. (2018). The discursive construction of journalistic authority in a post-truth age. Journalism Studies, 19(13), 2001–2010. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2018.1492879

- Willnat, L., & Weaver, D. H. (2018). Social media and U.S. Journalists. Digital Journalism, 6(7), 889–909. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2018.1495570

- Wojcik, S., & Hughes, A. (2019). Sizing Up Twitter Users: U.S. adult Twitter users are younger and more likely to be Democrats than the general public. Most users rarely tweet, but the most prolific 10% create 80% of tweets from adult U.S. users. Pew Research. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2019/04/24/sizing-up-twitter-users/

- Xia, Y., Lukito, J., Zhang, Y., Wells, C., Kim, S. J., & Tong, C. (2019). Disinformation, performed: Self-presentation of a Russian IRA account on Twitter. Information Communication and Society, 22, 1646–1664. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2019.1621921

- Zelizer, B. (1992). Covering the body: The Kennedy assassination, the media, and the shaping of collective memory. University of Chicago Press.