ABSTRACT

The expanding gaming industry now includes a large group of consumers who watch others play games. On Twitch.tv – the leading platform for gameplay streaming – influencers livestream themselves playing games while viewers watch and interact with them. Previous research suggests that social interaction may be critical for a successful stream but has not studied gameplay streams as Interaction Rituals, a model describing how interaction lead to social motivation. Analysis of four gameplay streams shows how the streamer, through inclusion strategies and active viewer participation, promote viewer engagement in a way that resembles the mechanisms of offline Interaction Rituals. The model, therefore, appears to be useful for understanding how successful gameplay streams draw a returning audience through producing positive social emotions and parasocial attachment to the group.

1. Introduction

Newzoo (Citation2020) estimates that 2.7 billion people play games and that gaming industry revenue will reach 159.3 billion USD during 2020. Gaming has quickly become one of the largest entertainment industries on the planet, surpassing the movie and music industries combined. New forms of consumption have evolved; a sizable audience now consumes gaming by watching others play. Esports events have been recorded to draw more viewers than the Super Bowl (Genova, Citation2018) and in the 2019 world champion in Fortnite won nearly six times as much as the winner of Tour de France (Nicolaou, Citation2019).

Many consumers now watch gameplay videos, where content creators play games while sharing their perspectives and commenting on the games. On YouTube, the biggest channels have many millions of subscribers and their owners have become world-famous influencers expanding into other forms of content. Undoubtedly, the ability to generate viewer engagement is critical for their success. However, in the case of YouTube, which mainly houses pre-recorded videos, the ability to interact with viewers is limited.

The situation is different on Twitch.tv – the second biggest platform for gameplay videos – where content is primarily livestreamed.Footnote1 Compared to pre-recorded and edited content, live streaming presents unique integration opportunities and challenges. A central challenge is for the streamer to create and maintain viewer engagement by keeping the uncut stream entertaining between eventful or action-packed moments. This challenge is offset, however, by the primary advantage of livestreaming: It enables direct interaction with the audience. Successful streamers make good use of technical affordances for interaction, such as appearing on-screen via a web camera or having a separate monitor dedicated to the viewer chat. Viewer engagement is especially important on Twitch, as the platform enables viewers to donate money in real time to ‘cheer’ on content they enjoy.

Collins’s (Citation2004) Interaction Ritual – model has been used to show how social motivation is produced through interaciton in a range of groups, subcultures and movements. In the last decade, it has also been applied to online interactions, such as text messaging, special-interest forums, and online dating (c.f. Anker Nexø & Strandell, Citation2020; Boyns & Loprieno, Citation2013; DiMaggio et al., Citation2018; Ling, Citation2008; Maloney, Citation2013). These studies demonstrate how shared symbols and norms of interaction can produce social motivation to revisit interactions. Since gameplay streams involve intense real-time interaction, video and audio components, and large groups of returning participants, it is likely that these even further resemble offline interaction rituals, such as concerts or sporting events. Previous research on Twitch suggests that interaction plays an important role in successful streams for learning, creating shared meaning and shaping pro-social behavior (c.f. Diwanji et al., Citation2020; Recktenwald, Citation2017; Seering et al., Citation2017a; Woodcock & Johnson, Citation2019). The Interaction Ritual – model could therefore likely be applied as a generalizable theoretical framework to identify the interaction mechanisms that contribute to successful streams through the buildup of positive social emotions and parasocial attachment to the group.

1.1. Objective

The purpose of this study is to explore the role of interaction rituals in building viewer engagement on Twitch gameplay streams. This has the twofold purpose of (1) identifying interactive mechanisms of successful streams, and (2) contributing research on the utility of Collins’s Interaction Ritual – model online.

2. Previous research

Viewers are motivated by different factors, such as desires to learn about a particular game or for social interaction and belonging (c.f. Hamilton et al., Citation2014; Hilvert-Bruce et al., Citation2018). This variety suggests that different streamers may attract different audiences. Gandolfi (Citation2016) identified three Twitch gameplay streamer interaction styles: (1) the challenge streamer, who prioritizes gameplay; (2) the exhibition streamer, who emphasizes entertainment and performance; and (3) the companion streamer, who relies most on social and emotional connection with viewers. Streamer characteristics may also matter for why viewers offer emotional, instrumental and financial support (see Wohn et al., Citation2018).

Other researchers have studied how streamers build viewer engagement while growing their channels. Hamilton et al. (Citation2014) reported that two important factors for viewer engagement are perceived streamer friendliness and the ability to create a unique social atmosphere of shared attitudes specific to the stream. Creating an interaction-conductive yet value-specific social environment may help branding the stream and promote group identification, which attracts like-minded followers.

Johnson and Woodcock (Citation2019) identified social tools used by streamers to encourage emotional engagement, including humor, adapting to viewer wishes, rapid responsiveness to viewers, emotional reactivity, and acting appropriately to game context. Many streamers are more animated on stream than in real life, which may facilitate online interactions. Some even turn the stream into an expressive performance act. Such performances and animated personas may be advantageous for branding and exploiting the attention economy of social media (Senft, Citation2013). In apparent contrast, microcelebrity studies, which have been applied to Twitch (Song, Citation2018), argue that authenticity is important for viewer engagement (Marwick, Citation2015; Marwick & Boyd, Citation2011). However, in these studies, ‘authenticity’ refers to knowing and directly interacting with fans, which not necessarily excludes theatrical performances or even personas.

Other research has focused more on viewer participation. For example, Seering et al. (Citation2017a) found imitation to be prevalent in Twitch-chats, as well as conformity with authorities, such as chat moderators. Diwanji et al. (Citation2020) found the most frequent interactive behaviors on Twitch to include reactions and information production. Such studies indicate that Twitch often involves common behavioral scripts, a precondition of interaction rituals (see Section 3). Other research suggests that viewer engagement may depend on viewers’ ability to influence the stream (Glickman et al., Citation2018; Seering et al., Citation2017b).

Maintaining viewer engagement may become more difficult as a channel grows and interaction becomes less personal. Streamers describe a threshold where personalized interactions with individual viewers shift into interacting with the viewers as a collective, which may negatively affect interaction (Hamilton et al., Citation2014). Interviewed streamers reported that this threshold is low, around 100–150 viewers. Some streamers, who prefer more personal interaction, therefore intentionally keep their communities small. Socially motivated viewers may also prefer smaller channels, because larger channels cannot provide the same interaction experience (Hilvert-Bruce et al., Citation2018).

A common denominator of previous research is that social interaction appears to be important for successful streams on Twitch. Although viewer motivation may vary – and some participate actively while others just watch – all viewers are exposed to the interactions in the streams. It may therefore be that even passive viewers enjoy the social experience.

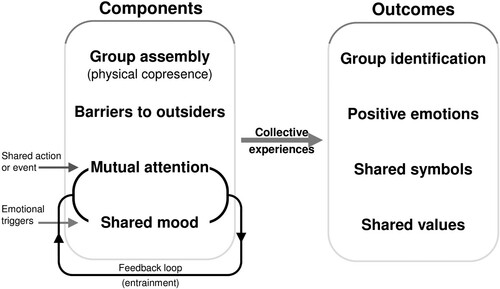

3. Interaction rituals

Collins’s (Citation2004) Interaction Ritual model has been extensively used to identify interaction mechanisms leading to social motivation and identification with a group. In this model, a ‘ritual’ is any group interaction with structured elements, ranging from spontaneous interaction (e.g., children playing) to formal rituals such as a sermon. Successful rituals produce positive emotional associations with the group and its symbols, contribute to group identification, reaffirm shared values, and build motivation to revisit the ritual (see ). This ability of group dynamics (‘rituals’) to consistently produce positive social emotions is what motivates individuals to return to feel more of the same, creating ‘interaction ritual chains.’ The model could therefore likely be used to analyze how successful streamers achieve growing viewer engagement.

Beyond group assembly, three components are necessary for a successful ritual. First, the interaction needs clear barriers that delineate the group, creating a sense of membership and belonging. Barriers may be physical (a church or concert hall) but could also be a particular subcultural style, formal membership requirements, or specialized knowledge. Second, participants must share a mutual focus. This can be a single point of attention (the music and/or musician at a concert) or a mutual awareness of a synchronized behavior (a crowd dancing or a formal ritual). Finally, participants need to establish a shared mood, both feeling things about the interaction itself and being aware of similar feelings in others.

The last two components are critical because they involve active interaction and lead to a process of emotional buildup (entrainment) through back-and-forth interaction. Synchronized behavior, attention and mood – coupled with mutual awareness of the same in others – provides a self-reinforcing feedback-loop of increasingly positive social emotions and sense of belonging. Furthermore, over time participants associate positive emotional experience with the group, its symbols and activities, which motivates further engagement.

Collins’s (Citation2004) original model states that bodily presence in a physical space is necessary for sufficient mutual attention and behavior synchronization to build intense emotions. Events such as weddings or concerts would simply not have the same impact over the phone. However, researchers have since argued against this position (c.f. DiMaggio et al., Citation2018; Ling, Citation2008; Maloney, Citation2013).

DiMaggio et al. (Citation2018) and Maloney (Citation2013) demonstrated that interaction rituals do occur online. By replacing physical and behavioral cues with digital substitutes, online interactions can produce similarly intense social emotions and experiences as offline interactions (Boyns & Loprieno, Citation2013). Such interaction rituals rely heavily on shared symbols, knowledge, and communication patterns, which are simultaneously barriers to outsiders and substitutes physical behavior synchronization in the rhythmic entrainment of emotions. For example, synchronization of emoji use has been shown to play an important role in the experience of ‘chemistry’ in online dating (Anker Nexø & Strandell, Citation2020).

4. Method

A sample of four recent streams by successful gameplay streamers were selected as cases for this study (see ). Four streams is a limited sample and generalizations should therefore be made with caution, even with streams reaching thousands of viewers. However, for an explorative study with the purpose of identifying theoretical mechanisms and applying the interaction ritual -model, four representative cases with variance within a shared category were deemed sufficient. These streamers were selected on four criteria: (1) regular streaming of single-player gameplay, (2) active audience interaction, (3) variance in gameplay, and (4) variance in following size. The latter was considered important since audience size could affect the form and quality of interactions (Hamilton et al., Citation2014; Hilvert-Bruce et al., Citation2018). The material was collected between February and April 2020 and was transcribed into 270 pages of data.

Table 1. Sample overview.

Variance within the shared category of single-player gameplay streams is important since different streams have different social atmospheres and interaction styles (c.f. Gandolfi, Citation2016; Hamilton et al., Citation2014). In contrast to competitive multiplayer games, where the goal is to beat other players in games of skill, much like traditional sports, single-player games are usually either narrative-driven experiences (much like a movie) or sandbox gameplay, where players explore and/or build worlds to their liking.

The four streamers varied significantly in their persona and interaction style:

KickthePJ is a highly aesthetical, visual and experienced-focused, streamer who also draws and uses elaborate camerawork and voice acting in his stream. His stream is particularly oriented towards indie games such as Ori and The Will of The Wisps.

TeaWrex plays high-end action games, demanding high skill and intense graphics. His discussions are typically about game-lore and complex game mechanics, here in The Witcher 3. TeaWrex is also experience-focused but less about performance than KickthePJ and more about game immersion.

Mithzan focuses on gameplay and on a friendly social experience in the stream, playing games together with friends or interacting with the audience, presenting in-game achievements or tricks and tips for the viewers. In the material, he plays Animal Crossing: New Horizons, a light-hearted social simulation game.

GiantWaffle, a former engineering student who also deals in stocks, has a more rational and goal-oriented persona than the others. His interaction centers on gameplay mechanics, optimization and achievement. In the sandbox game Minecraft, he undertakes big construction projects.

4.1. Transcription, coding, and analysis

Studying interactions between video/audio content and intense live chats with many participants presents particular transcription challenges. The material often contained simultaneous, interrelated and fast-paced interactions and events from many actors, often occurring within a second and in different form (e.g., games/speech/visuals/text). For example, if a viewer subscribes to a channel during a live stream, a popup could appear and be recognized verbally by the streamer simultaneously as dozens of viewers discuss parallel game events. In this study, events were recorded in temporal order in a single transcript, using timestamps to capture the rapid flow of interaction. A selective transcription process was employed, in which events and communication unrelated to interaction, such as spam or silent stretches of gameplay, were excluded. The transcript included chat logs (with Twitch emojis/symbols) and streamer audio-transcripts (word-by-word), parallel with observational notes about what occurred on the screen, including gameplay, twitch notifications and streamer behavior.

We analyzed the material using qualitative content analysis in two phases. In the initial inductive (data-driven) phase, we coded patterns of interaction reoccurring across the material, focusing on concrete practices without regard for Collins’ theoretical concepts. This yielded analytical categories consolidated into three themes represented in the analysis as: Engaging viewers emotionally, Inclusion strategies and Viewer participation. In the second phase, these analytical categories were linked to the Interaction Ritual -model, as presented in the analysis section.

4.2. Ethical considerations

The study faced ethical challenges of getting informed consent and ensuring anonymity, circumstances common to internet research. Finding and contacting thousands of partly anonymous viewers and getting their informed consent is not feasible. However, since the material is publically available, it is reasonable to assume that both streamers and viewers participate with the knowledge that their actions and statements may be used for all kinds of purposes, including research.

Viewer usernames were replaced with numbers to protect privacy while still being able to track individuals through interactions. We decided to retain nicknames of the streamers after consultation with colleagues and internet research guidelines, assessing in particular the reasonable expectation of publicity, the accessibility in the public sphere and the sensitivity of the information (see NESH, Citation2018). Streamers are acting as public personas (e.g., a TV host), on a platform with open access, and the material contains no sensitive information. Against this, we weighed the value of the information for: (1) transparency, as other researchers may assess the analysis, (2) added contextual information for familiar readers, and (3) wordplays using streamer names, which occur in ways that would be difficult to represent in anonymized form.

5. Analysis & results

5.1. Engaging viewers emotionally

Throughout the material, the streamers ignited and/or were the focus of the majority of interactions. This disproportionate attention to the streamers is likely not only due to their control, power or fame, but also because only they have auditory and visual presence. This means that the streamer inevitably is a mutual attention point, much like a ritual leader, in addition to what went on in the game.

In line with previous research (Gandolfi, Citation2016; Hamilton et al., Citation2014; Hilvert-Bruce et al., Citation2018), distinct atmospheres and styles of streamer interaction could be discerned in this material. For example, Mithzan displayed traits of a ‘challenge streamer’ by focusing heavily on the game itself and letting game events drive the content of the stream. Typical interactions would involve providing factual answers to viewer questions about the games themselves. This can be contrasted with GiantWaffle and Teawrex, two streamers whose styles resemble the ‘companion streamer.’ These streamers emphasized community building and used viewer interaction as the main driver of direction and progress in the stream. In their streams, the gameplay functioned more as context for social interaction than as the primarily focus of it.

While the four streamers displayed different traits of the categories identified by Gandolfi (Citation2016), there are limitations in characterizing these streamers. Although the streamers clearly had different styles, they all emphasized viewer interaction, not only the ‘companion streamers.’ For example, KickthePJ – whose general style was that of an ‘exhibition streamer,’ using dramatic performances to stimulate interaction and spark energetic reactions from the viewers – frequently displayed explicit concern for maintaining a socially conductive atmosphere. The excerpt below shows how KickthePJ repeatedly checked in on his audience:

Table

Here KickthePJ tries to verify that the viewers are enjoying the stream maintaining emotional energy. Several viewers ensure that they are, in fact, enjoying the stream so far. The streamer makes use of his dramatic acting and humor to provoke further validation by pretending to be the viewers and criticizing his own stream. This light-hearted joking in turn evokes even more positive engagement from additional viewers.

Note that KickthePJ builds increasing emotional energy through a successive entrainment process that involves triggering further positive emotions and associations by responding to and encouraging the viewer interaction, leading to the buildup of a positive shared mood. The streamer did not only gain information on viewer experiences but ensured a mutual focus of attention on positive experiences. By making the viewers share their collective positive experiences, he turns the viewers’ attention to their own emotions and the fact that others share those experiences. Note that the impact of this depends on a succession of chained actions. The viewers’ initial responses were followed by further encouragement, which triggered increasing viewer engagement. The process, which Collins (Citation2004) called entrainment, builds excitement through successive mutual validation of shared experiences. In this way, a sense of community is effectively created, shared attitudes are reaffirmed, and the stream is associated with positive feelings (emotional energy).

In the following excerpt, we can observe another example of the streamers facilitating viewer engagement through recognition and validation of shared experiences and attitudes. This is a segment of a larger discussion on ‘time skipping’ in Animal Crossing, which could be considered an improper or unserious way of playing the game. In the discussion, the streamer repeatedly recognized opinions that reflected his own, such as the conviction that time skipping should not to be shamed:

Table

In this short exchange between three participants, shared views are reaffirmed through mutual validation. The excerpt enters as Viewer64 validates the streamer’s time skipping by saying that this participant does the same. Mithzan recognizes this by arguing in favor of time skipping. This is followed by Viewer8’s assertion of the same position through sarcasm, ridiculing those who shame time skipping. Finally, Mithzan rewards the joke by reading it out and laughing at it.

This is another example of a successful interaction where viewer engagement is facilitated through a process of social entrainment. Much like in the previous example, the streamer is both the leader and the center of attention in a process of rhythmic entrainment of positive shared attitudes. This is one of many examples illustrating how streamers actively work to maintain a friendly atmosphere, which has been suggested to be conducive to successful streams (c.f. Hamilton et al., Citation2014; Johnson & Woodcock, Citation2019).

The influential role of the streamer is also evident during ‘pivoting,’ the processes of ascribing meaning to game events. Recktenwald (Citation2017) used the term to explain how the ‘roar of the crowd’ (p. 69) sometimes establishes or changes the meaning of game events. Pivoting was repeatedly observed throughout the study, occasionally involving the viewers, such as in the example below. While streaming, KickthePJ portrayed the game character Tokk favorably, only to later change his attitude, which led to similar reactions among viewers. This shows the flow of emotional energy, the streamer as a ritual leader and his influence on social entrainment. Note also how KickthePJ, who relies heavily on performances, frequently imitates Tokk while reading from the game. This is typical of exhibition streamers (Gandolfi, Citation2016) and streamers who are more animated on camera than in real life (c.f. Woodcock & Johnson, Citation2019).

Table

This example shows how the streamer’s reactions to game content are followed by corresponding attitudes expressed by the viewers. The initial positive reactions to Tokk elicited a positive response from the viewers, which later changes to negative reactions as KickthePJ reassesses Tokk. It is clear that pivoting is a dynamic group process during which shared attitudes are established, communicated, or changed, in relation to a shared point of attention (a symbolic object).

5.2. Inclusion strategies

The streamers frequently used a range of strategies to encourage active participation and to maintain a conductive social climate, which often seemed more important than the gameplay content. Three inclusion strategies were frequently observed: (1) streamer authenticity, (2) recognition of viewers, and (3) the use of collective pronouns.

As previously demonstrated by microcelebrity research (c.f. Marwick, Citation2015; Marwick & Boyd, Citation2011), authenticity seemed to encourage viewer engagement. Creating inclusion through streamer authenticity involved streamers sharing their thoughts and reflections on topics beyond current gameplay, such as future plans or personal topics. Talking about future plans also provided an opportunity for viewer influence through opinions and suggestions. Transparent sharing of personal topics also appeared to promote parasocial bonding – a sense of having a personal relation to the streamer – especially when the shared information resonated with the views and attitudes of the viewers. We interpret this as yet another way to encourage a shared attention and mood in thousands of viewers. In the following example, KickthePJ shared a story of traveling to Iceland completely unrelated to gameplay content, which is met with positive responses from viewers who could imagine that they too would enjoy the experience:

Table

Recognition as a technique for inclusion sometimes simply meant validating the viewers’ attitudes (as illustrated in Section 5.1), but it often involved highlighting and thanking people for live monetary donations or subscriptions.Footnote2 Recognizing contributions commonly involved ‘shoutouts’ – loudly thanking contributors by their (user)names, such as: ‘Hey Viewer49! Thank you so much for that tier 1 sub my dude!’ (Mithzan).

Inclusion through recognition by attending to viewer questions was a recurring theme, but frequency and type of questions varied between the streams. KickthePJ, who is more of a performance or exhibition streamer, received fewer questions, whereas the steamers more focused on social companionship received more. The streamers also frequently received questions unrelated to the gameplay of the stream. In the following excerpt, Giantwaffle is replying to multiple viewers’ questions regarding his views on the economic outlook:

This excerpt is an excellent example of a companionship actively including several viewers in a conversation completely unrelated to gameplay. However, it is important to note that just like inclusion was important to some degree in all streams, all streamers also relied on gameplay content as a driving force for the progression of the stream, including the companionship-oriented streams.

A final, more subtle yet very common, inclusion strategy was the use of collective pronouns when streamers talked about their actions in games. By replacing the first person ‘I’ with ‘we,’ the streamers all attributed collectively agency to their own actions. This creates a sense of the gameplay or stream being a group endeavor in which the viewers are actively participating, which could increase emotional entrainment by making viewers feel like they are part of an interaction ritual. The identification of a collective ‘we’ delimits the group, encourages shared attention, and contributes to a positive collective mood, such as triumphant emotions when progress is made. These two excerpts illustrate this practice:

The prevalence of these three inclusion strategies in all streams suggests that they are key components for creating viewer engagement in single-player gameplay streams. This corresponds with previous research, in which interviewed streamers reported that making viewers feel included was necessary for success (Hamilton et al., Citation2014; Johnson & Woodcock, Citation2019).

5.3. Viewer participation

While the streamer leads the ritual and builds engagement through inclusion strategies, the viewers are not passive. They contribute to the buildup of emotional energy and a sense of community through collective actions. This was particularly obvious when jokes evolved around which the community could engage. The streamer often unintentionally initiated this through actions or statements, but the process of turning it into a recurring joke always involved multiple viewers highlighting, commenting on, and repeating it until it became a community meme. In the abridged excerpt below, we can follow this process:

Table

This example shows how game content, streamer performances, viewer reactions, and streamer recognition of those reactions, together promote viewer engagement over time. The streamer initially reacted to gaining an ability called ‘sticky,’ allowing the player to stick to walls, which the viewers playfully turned into a joke by nicknaming the streamer.

Inside jokes, memes, shared memories, and jargon frequently occurred in all streams. These are examples of digital symbolic objects, which through successful interaction rituals have become associated with positive emotional energy (Collins, Citation2004). Simply referencing the symbolic object later on can invoke these associations, in oneself and in others, making it a powerful sociopsychological mechanism. However, since this process requires a successful interaction ritual, the streamer alone has limited power over the creation of symbolic objects.

On Twitch, symbolic objects are heavily used by viewers, and many common emojis and memes are integrated into the default user interface. For example, the term ‘bozo’ has its own emoji, which makes it a symbolic object in a very literal sense:

Table

Here the streamer’s use of the word ‘bozo’ elicits excited engagement from the viewers (indicated by the rapid succession of related reactions). The fact that this was triggered by a single word and had no previous buildup suggests that the term is already a well-established symbolic object in the community. Note how this use of emojis as symbolic objects is an excellent example of a digital interaction ritual. The symbolic object creates a barrier to outsiders (since shared knowledge is necessary to participate), it provides shared attention point and can be part of highly synchronized collective behavior. The regular viewers of the stream already know what to do and they do it in an instant, collectively, while experiencing others doing the exact same thing. This corresponds with previous research finding imitative communication to be prevalent on Twitch (Seering et al., Citation2017a).

The existence of barriers to outsiders in the form of shared knowledge necessary for full participation was also observed when newer viewers were confused by interactions building on shared experiences. For example, the game character Wart Jr. was frequently met with enthusiastic favor in Mithzan’s stream despite being depicted as a ‘cranky personality’:

This playful collective sentiment had been established in previous streams, which made new viewers unable to pick up on the joke. The fact that the streamer suggests watching past content instead of explaining maintains the value of the shared experience and simultaneously encourages the new viewer to engage more with the stream.

Sometimes the viewers could directly influence the stream collective actions. In the next example, Teawrex expresses his disinterest in Gwent, a card game within The Witcher 3. However, several viewers display great passion for Gwent through expressions, emojis, arguments, and (playful) threats of unsubscribing.

Table

Following this, Teawrex eventually submits to the will of the crowd and plays Gwent, which in turn contributes to a more successful interaction ritual. Ignoring pressure from the viewers can likely break the buildup of emotional entrainment by creating friction in the combination of shared attention and mood. This would be in line with previous research suggesting that viewer engagement may depend on their ability to influence the stream (Glickman et al., Citation2018; Seering et al., Citation2017b).

Finally, collective action is critically important in sociotechnical events on Twitch like ‘hype trains’ or ‘raids.’ Raiding involves streamers temporarily streaming another live stream on their channels, which also brings their viewers into the raided stream. This significantly increases the numbers of current and potential future viewers. The raid simultaneously exposes viewers to a new stream and gives them a ‘stamp of approval’ from a streamer they already like. Raids are important social events on Twitch that typically lead to excited reactions from viewers:

Table

Here an automated message signaled the raid, which was followed by excited reactions from the raided streamer and his viewers. Note that this whole excerpt took place over a span of nine seconds, which suggests that a raid is a very potent symbolic object capable of triggering an intense spike of collective emotional energy.

The greatest surge of viewer engagement – measured in intensity, number of reactions or temporal extent – was observed during another event: a hype train. This sociotechnical event is triggered when viewers gift large numbers of subscriptions to others. Like a raid, this leads to many excited reactions:

Table

6. Conclusions & discussion

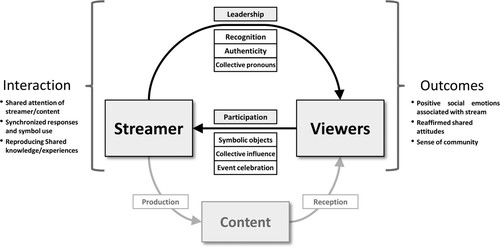

The analysis shows how viewer engagement is encouraged in gameplay streams on Twitch through processes that largely resemble offline interaction rituals. Indicative of successful interaction rituals are synchronized expectations/behavior (e.g., extensive, rapid and collective hype train and raid -responses), shared symbolic objects (e.g., emojis, memes and inside jokes), and barriers to outsiders (e.g., shared experiences/knowledge of stream/gameplay). These are thought to lead to positive social emotions associated with the stream and a sense of group membership (Collins, Citation2004). summarizes the components of the interaction rituals particular to gameplay streams on Twitch, as observed in the data.

The interaction dynamic between viewers and streamer is central to creating viewer engagement. Gameplay content certainly matters (provides initial incentive and interaction topics), but it appears to be the interactive processes producing positive social emotions that lead to attachment to a stream. While gameplay content varied significantly between the four streams, the general interactive mechanisms that led to viewer engagement were consistent across the material. Consequently, researchers should view gameplay streams as largely social activities, where the ability to create emotional energy through inclusive interaction rituals are central for successful streamers. This study suggests that the Interaction Ritual framework is useful for understanding and explaining why Twitch is a successful entertainment model. It tells us why people come back, why they follow successful streamers, and why they donate money for free content. Specifically, this is achieved by producing positive social emotions and parasocial attachment to the stream as a social group through mechanisms reproducing rituals, symbols and barriers to outsiders. The Interaction Ritual -model, therefore, appears to be not only applicable in this online setting, but also particularly useful for researchers interested in understanding what draws people to certain streams.

In line with previous research (e.g., Anker Nexø & Strandell, Citation2020; Boyns & Loprieno, Citation2013; DiMaggio et al., Citation2018; Ling, Citation2008; Maloney, Citation2013), this study demonstrates that Collins’s (Citation2004) Interaction Ritual model can be applied to online interactions, even when visual and auditory communication is one-sided. These findings also suggest that the mutual awareness of synchronized physical behavior can be effectively substituted with digital mechanisms such as synchronized viewer reactions. Interaction rituals appear to be essential for successful Twitch gameplay streams, which heavily rely on these processes. Twitch is in fact designed to utilize such processes well, such as by putting the streamer in control of shared attention, rewarding engagement through subscriptions or donations, and by providing emojis for expressions and memes that can serve as symbolic objects.

This study is limited by the small sample, and its conclusions should not be read as empirical/quantitative generalizations. For the purpose of identifying mechanisms promoting viewer engagement through Interaction Rituals on Twitch, the sample was selected to be representative of typical single-player gameplay streams with variance within the shared category (following size and type of gameplay). Therefore, we believe that the results have high ecological validity within that category but should not be precipitously transferred to other streaming categories, where other mechanisms may be more important. These limitations invite further research to investigate whether similar mechanisms apply in other categories. Another limitation that warrants further study is that netnographic methods cannot observe viewer emotions or experiences directly. Combining observations and interviews could capture both expressions and internal experiences of viewer engagement. For stronger validity, this could also involve observing participant reactions while watching a live stream, followed by conducting interviews directly after the stream. Finally, longitudinal studies could capture how interaction ritual chains are created as a streamer’s community evolves over time.

Acknowledgements

This article is a heavily reworked version of a bachelor thesis submitted by Henrik Jodén in 2020, supervised by Jacob Strandell, at Uppsala University. We want to acknowledge and thank the anonymous peer reviewers for their constructive feedback as well as Mikael Harmén & Evelina Svadling who read and commented on earlier versions of the paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Henrik Jodén

Henrik Jodén is a postgraduate student in social psychology at Uppsala University. His main focus is on online interaction. He has throughout his studies been engaged with social constructivism and symbolic interactionism.

Jacob Strandell

Jacob Strandell is a postdoctoral researcher specialized in cognitive sociology. His research emphasizes the role of psychological mechanisms in a range of sociological topics such as sustainability, identity and motivation, and intimate relationships.

Notes

1 For an extensive ethnographic account of the everyday practical, organizational and legal aspects Twitch gameplay streaming, see Taylor (Citation2018).

2 Subscriptions are monthly payments to support a streamer, which in return is rewarded with socially recognizable symbols such as custom emojis and badge.

References

- Anker Nexø, L., & Strandell, J. (2020). Testing, filtering, and insinuating: Matching and attunement of emoji use patterns as non-verbal flirting in online dating. Poetics, 83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poetic.2020.101477

- Boyns, D., & Loprieno, D. (2013). Feeling through presence: Toward a theory of interaction rituals and parasociality in online social worlds. In Benski, & Fisher (Eds.), Internet and emotions (pp. 47–61). London: Routledge.

- Collins, R. (2004). Interaction ritual chains. Princeton University Press.

- DiMaggio, P., Bernier, C., Heckscher, C., & Mimno, D. (2018). Interaction ritual threads: Does IRC theory apply online? In W. B. Weininger, A. Lareau, & O. Lizardo (Eds.), Ritual, emotion, violence (pp. 99–142). Routledge.

- Diwanji, V., Reed, A., Ferchaud, A., Seibert, J., Weinbrecht, V., & Sellers, N. (2020). Don’t just watch, join in: Exploring information behavior and copresence on Twitch. Computers in Human Behavior, 105, 106–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.106221

- Gandolfi, E. (2016). To watch or to play, it is in the game: The game culture on Twitch.tv among performers, plays and audiences. Journal of Gaming & Virtual Worlds, 8(1), 63–82. https://doi.org/10.1386/jgvw.8.1.63_1

- Genova, V. (2018). LoL world championship draws more viewers than the super bowl. Dexerto. Retrieved July 30, 2020 from https://www.dexerto.com/esports/lol-world-championship-draws-more-viewers-than-the-super-bowl-209502

- Glickman, S., McKenzie, N., Seering, J., Moeller, R., & Hammer, J. (2018). Design challenges for livestreamed audience participation games. CHI PLAY 2018 – Proceedings of the 2018 Annual Symposium on Computer-Human Interaction in Play.

- Hamilton, W. A., Garretson, O., & Kerne, A. (2014). Streaming on Twitch: Fostering participatory communities of play within live mixed media. Proceedings of the 32nd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems – CHI ‘14, 1315–1324.

- Hilvert-Bruce, Z., Neill, J. T., Sjöblom, M., & Hamari, J. (2018). Social motivations of live-streaming viewer engagement on Twitch. Computers in Human Behavior, 84, 58–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.02.013

- Johnson, M. R., & Woodcock, J. (2019). The impacts of live streaming and Twitch.tv on the video game industry. Media, Culture & Society, 41(5), 670–688. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443718818363

- Ling, R. S. (2008). The mediation of ritual interaction via the mobile telephone. In J. E. Katz (Ed.), Handbook of mobile communication studies (pp. 165–176). MIT Press.

- Maloney, P. (2013). Online networks and emotional energy: How pro-anorexic websites use interaction ritual chains to (re)form identity. Information, Communication & Society, 16(1), 105–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2012.659197

- Marwick, A. E. (2015). You may know me from YouTube: (Micro-)celebrity in social media. In P. D. Marshall, & S. Redmond (Eds.), A companion to celebrity. Wiley-Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118475089.ch18

- Marwick, A. E., & Boyd, D. (2011). I tweet honestly, I tweet passionately: Twitter users, context collapse, and the imagined audience. New Media and Society, 13(1), 114–133. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444810365313

- NESH (The [Norwegian] National Committee for Research Ethics in the Social Sciences and the Humanities). (2018). A guide to internet research ethics. NESH.

- Newzoo. (2020). Global games market report 2020. Retrieved July 27, 2020, from https://newzoo.com/insights/trend-reports/newzoo-global-games-market-report-2020-light-version/

- Nicolaou, A. (2019). Fame and ‘Fortnite’ – Inside the global gaming phenomenon. Financial Times. Retrieved April 12, 2020, from https://www.ft.com/content/f2103e72-b38f-11e9-bec9-fdcab53d6959

- Recktenwald, D. (2017). Toward a transcription and analysis of live streaming on Twitch. Journal of Pragmatics, 115, 68–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2017.01.013

- Seering, J., Kraut, R. E., & Dabbish, L. (2017a). Shaping pro and anti-social behavior on Twitch through moderation and example-setting. Proceedings of the 2017 ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing.

- Seering, J., Savage, S., Eagle, M., Churchin, J., Moeller, R., Bigham, J. P., & Hammer, J. (2017b). Audience participation games: Blurring the line between player and spectator. Proceedings of the 2017 ACM Conference on Designing Interactive Systems. https://doi.org/10.1145/3064663.3064732

- Senft, T. M. (2013). Microcelebrity and the branded self. In J. Hartley, J. Burgess, & A. Bruns (Eds.), A companion to new media dynamics. Wiley-Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118321607.ch22

- Song, H. (2018). The making of microcelebrity: AfreecaTV and the younger generation in neoliberal South Korea. Social Media + Society, 4(4), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305118814906

- Taylor, T. L. (2018). Watch me play: Twitch and the rise of game live streaming. Princeton University Press.

- Wohn, D. Y., Freeman, G., & McLaughlin, C. (2018). Explaining viewers’ emotional, instrumental, and financial support provision for live streamers. Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems – Proceedings. https://doi.org/10.1145/3173574.3174048

- Woodcock, J., & Johnson, M. R. (2019). The affective labor and performance of live streaming on Twitch.tv. Television & New Media, 20(8), 813–823. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527476419851077