ABSTRACT

Automated decision-making using algorithmic systems is increasingly being introduced in the public sector constituting one important pillar in the emergence of the digital welfare state. Promising more efficiency and fairer decisions in public services, repetitive tasks of processing applications and records are, for example, delegated to fairly simple rule-based algorithms. Taking this growing trend of delegating decisions to algorithmic systems in Sweden as a starting point, the article discusses two litigation cases about fully automated decision-making in the Swedish municipality of Trelleborg. Based on analyzing court rulings, exchanges with the Parliamentary Ombudsmen and in-depth interviews, the article shows how different, partly conflicting definitions of what automated decision-making in social services is and does, are negotiated between the municipality, a union for social workers and civil servants and journalists. Describing this negotiation process as mundanization, the article engages with the question how socio-technical imaginaries are established and stabilized.

Introduction

In August 2020, the UK saw a weekend of protest with students chanting ‘Fuck the Algorithm’ outside of the Department for Education (The Verge, Citation2020).Footnote1 Their anger was directed against an algorithm predicting A-level results. Based on these predictions, universities are offering spots to students that then must receive a certain grade in their exams to be admitted. The algorithm predicted A-level results based on the ranking of an individual student combined with the historical performance of the specific school attended. In response to the results that down-graded almost 40% of the students compared to the solely teachers-based expectations, critics argued that private schools in affluent areas and communities were privileged by the parameters on which the algorithm was based. Well-performing students in low performing schools were disadvantaged. Due to the mounting critique, the algorithm that was supposed to replace the canceled A-level exams was rolled back and grades were based on teachers estimates instead (The Guardian, 2020Footnote2). This is just one example of how algorithm-based forms of automation are increasingly deployed in public administration and the welfare sector that encompasses both funding for public institutions for health care and education – as in the example above – as well as direct financial benefits for residents – as focused upon in the following. It also illustrates the potential problems of bias and decreased social mobility that might emerge in the context of algorithmic automation that is based on and reinforces historical inequalities.

Algorithms, automated decision-making, and artificial intelligence (AI) have become important markers for efficiency, progress, and success not only in private businesses, but also and particularly in the public sector (Kaun & Taranu, Citation2020) and are a constitutive part of what has been called the digital welfare state (Alston, Citation2019). Not only with COVID-19 have calls for broader and faster digitalization of the public sector been issued. Digital technologies in the public sector promise cost reduction as well as fairer decisions and a renewed focus on ‘the important aspects’ in the work of civil servants (Choroszewicz & Mäihäniemi, Citation2020).

Algorithms are increasingly enabling the automation of tasks in public administration of the welfare state, including applications for social benefits and child protection. Algorithms that are currently used in the welfare sector include simple decision trees (for example the Trelleborg model discussed here (Kaun & Velkova, Citation2019)), sorting (for example the sorting algorithms developed by the Austrian Employment Services that automatically sorts applicants into three different categories (Kayser-Bril, Citation2019)), matching as well as predictive algorithms (for example a predictive score estimating the likelihood of child abuse in Denmark (Alfter, Citation2019)). At the same time, potential issues with automated decision-making based on algorithms have been acknowledged at the policy level. The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) contains a paragraph on algorithmic decision-making and promotes ‘the right to explanation’ – that is, the right to be provided an explanation for the output of an algorithm (Goodman & Flaxman, Citation2016) and the right to verification and rectification of an algorithmic decision by a human, the so-called human in the loop provision (Dreyer & Schulz, Citation2019). Regardless of the encountered problems and expressed concerns, automation of public administration continues to be in full swing at the supranational, national, and local levels across European countries (European Council, Citation2018; Spielkamp, Citation2018). However, there is a lack of studies that engage empirically with the implementation of algorithmic decision-making at an everyday level, highlighting the imaginaries and practices that emerge in the context of implementing these complex systems in public administration from the different perspectives of actors involved.

This article engages with the negotiation of what algorithm-based decision-making in the public sector means and what consequences different definitions and understandings have for case workers and beneficiaries. Considering the prominent case of automated decisions on social benefit applications in the municipality of Trelleborg and litigation cases in connection with it, the article follows the ways in which algorithms and automated decision-making are defined by different actors. By following the negotiation and definition process, the article not only carves out different imaginaries developed, but also shows the practical implications of these definitions for citizens. The article draws a picture of how both bureaucrats, union activists and journalists imagine the contours and workings of automated decision-making in the public sector. Through in-depth interviews with the unit manager responsible for the automation project and a civil servant in Trelleborg as well as close readings of appeals to the Parliamentary Ombudsmen and one Administrative Court of Appeal, I trace the diverging and partly contradictory ideas of what automated decision-making (ADM) is and what consequences it has. The analysis shows how the meaning and understanding of ADM is negotiated and is connected with changing imaginaries of the benefits and dangers of implementing large-scale ADM systems in the welfare context. The article shows how such conflicts and negotiations contribute to what Robert Willim (Citation2017) has called the mundanization of technology, here in the case of ADM, namely strategies of developing everyday understandings of complex technologies that have implications for our everyday lives.

Background: the Trelleborg model and two litigation cases

Like most countries of the global north, Sweden has set an ambitious agenda of becoming world-leading in AI development and use (Government Offices of Sweden, Citation2018). This includes the transition in the public sector towards ‘digital first’ and digital by default, which is an important precondition for broad algorithmic automation. Accordingly, different algorithmic and data-based digital systems have been implemented in recent years. At the same time, Sweden has been connected with a specific model of welfare provision, the so-called Nordic model following the idea of a providing a strong safety net for residents including among other things basic care including health, education and elderly care for free. The automation of public administration of welfare provision is hence a crucial development that is affecting large parts of society. Taking the Trelleborg case as an example of this development, the analysis aims to intervene more broadly in discussions of algorithmic automation and the digital welfare state. At the same time, there is no shared understanding what automated decision-making and AI in the public sector encompasses. Hence, the article aims to engage with the different ways in which ADM in the public sector is defined by different actors that have stakes in the automation process.

Since 2017, the Trelleborg municipality with roughly 46,000 residents has introduced fully automated decisions on applications for social benefits. This case of automated decision-making is one of the most well-known and most widely discussed in Sweden. Trelleborg municipality prides itself for being at the forefront of automation efforts leading the piloting innovation program from Rebel to Model (Rakar, Citation2018). It often serves as a reference point to explore both algorithmic culture as well as the implications of the digital welfare state (Choroszewicz & Mäihäniemi, Citation2020; Kaun & Taranu, Citation2020). More specifically, the system is based on a rather simple decision tree model that cross checks certain variables with databases by for example the Tax Agency including income or payments by the state health insurance. All initial applications are processed manually by a case worker. However, follow-up applications that have to be submitted once a month are processed automatically. People affected by the ADM system are residents of the municipality who are applying for economic support (ekonomisk bistånd) including welfare benefits (försörjningsstöd) that either fully or partially cover costs of housing, food, clothing, telephone and internet access. One of the most discussed aspects of the introduction of this ADM system is the reduction of civil servants working with social benefit applications from eleven to three case workers. The number of residents that no longer rely on social benefits increased during 2017, the year the automation algorithm was introduced, to 450. The number of residents moving away from social benefits into other ways of securing an income was around 168 five years earlier. This decrease in beneficiaries is not merely attributed to automation by the municipality and journalists, but to a holistic program of re-integrating long-term unemployed into the job market (Swedish Television, Citation2018). The Trelleborg case has been controversially discussed early on. Criticism ranged from its illegal delegation of decisions to algorithmic systems that is not supported by legal regulations for municipalities, to questions of transparency as well as the future of the work and status of civil servants more generally.

As part of a general discussion on how welfare provision is changing with digitalization and in particular algorithm-based decision making (Alston, Citation2019; Kaun & Taranu, Citation2020), several actors started to explore the so-called Trelleborg model further. Firstly, the journalist Fredrik Ramel engaged in the discussion about transparency of the ADM system used in Trelleborg. After several failed attempts to get access to the source code from Trelleborg municipality and reaching out to the Danish company that was responsible for the coding, he took legal steps: He submitted an appeal to an Administrative Court of Appeal arguing that the source code of the software used falls under the Swedish principle of public access to official records (Offentlighetsprincipen). The court followed his appeal and ruled that the source code has to be made accessible to the public and is fully included in the principle of public access (Dagenssamhälle, Citation2020).

After the ruling of the Administrative Court was made public another group of journalists at newspaper Dagenssamhälle submitted a Freedom of Information Request in accordance with the principle of public access to official records to gain access to the source code. Trelleborg municipality forwarded the request to the Danish software company who delivered the code that was in turn shared with the journalists. The material was, however, not submitted to a security check and sensitive data including personal numbers (comparable to social security number), names and information about elderly care at home was delivered to the journalists (Dagenssamhälle, Citation2020).

Secondly, in 2018, Simon Vinge chief economist at the Union for Professionals (Akademikerförbundet SSR) reported the municipality of Trelleborg to the Parliamentary Ombudsmen (Justitieombudsmannen JO). He complained about the fact that the authorities failed to respond to a freedom of information request related to Robotic Process Automation (RPA) use to deliver automated decisions. As of fall 2020, SSR and Simon Vinge have not heard back from the Parliamentary Ombudsmen.

The digital welfare state: algorithms, AI and ADM in the public sector

Automated decision-making refers to the current process of implementing and delegating tasks to digital systems – both rule- and knowledge-based. One precondition for automated decision-making is the process of datafication, namely the quantification of social life at large and the production of big data (Mayer-Schönberger & Cukier, Citation2013). These changes are already underway in areas such as education, labor, and warfare, through for example, new forms of algorithmic governance (Eubanks, Citation2017; Kennedy, Citation2016; Mosco, Citation2017; O’Neill, Citation2016). Algorithmic automated decision-making or decision support systems are procedures that utilize automatically executed decision-making algorithms to perform an action (Spielkamp, Citation2018). With the help of mathematic models, big data, or the combination of different registers, algorithms issue a decision, for example, on an application for social benefits. While it has been argued that civil servants are freed from repetitive and monotonous tasks with the help of algorithms (Engin & Treleaven, Citation2019), automated decision-making does not avoid friction (Dencik et al., Citation2018; Eubanks, Citation2017; Zarsky, Citation2016). Apart from the issue of explanatory power, problems of ethics and accountability (Ananny, Citation2016; Sandvig et al., Citation2016) – including the question of human agency in relation to complex socio-technical systems (Kaun & Velkova, Citation2019; Kitchin, Citation2017) – have also been indicated as important challenges of automated decision-making.

At the same time, automated decision-making is intertwined with the transformation of the welfare state. Large-scale economic crises since the early 1970s have led to a shift in how welfare provision in Western democracy is organized (Bleses & Seeleib-Kaiser, Citation2004; Bonoli & Natali, Citation2012; Gilbert, Citation2002; Hemerijck, Citation2012). Often referred to as dismantling or transformation of the welfare state, a number of governments have privatized specific public services – including education, child, and health care as well as the corrections and the media sector – and increasingly introduced the model of new public management to run public sector organizations with the objective of making them more efficient by implementing private sector management routines (Pollitt et al., Citation2007). With processes of digitalization and datafication, we are experiencing a shift toward a new regime of welfare provision that is intricately linked to digital infrastructures that result in new forms of control and support. This new welfare regime – which has been described as new public analytics (Yeung, Citation2018) and which I together with Lina Dencik (Citation2020) have termed algorithmic public services – is characterized by new forms of privatization that not only take, for example, shape in new actors such as technology companies and coders entering the field of public administration, but also emerge in the form of increased delegation and reliance on complex technological systems (Veale & Brass, Citation2019). Although technology is often described in neutral terms (Sumpter, Citation2018), automated decision-making has implications for values of public administration beyond efficiency and service, including democratic participation, legal frameworks, objectivity, freedom of expression, and equality. In numerous cases, public administration institutions are considered as an important intermediary between the state and citizens (DuGay, Citation2005; Lawton, Citation2005; Van der Wal et al., Citation2008). Changes in the manner these institutions are organized have consequences for the relationship between the state and the citizens and, consequently, for democracy (Skocpol, Citation2003).

Although a comparatively large number of e-governance studies have emerged since the late 1990s (Andersen & Dawes, Citation1991; Brown, Citation2007; Edmiston, Citation2003; Ho, Citation2002; Layne & Lee, Citation2001) and a few projects are starting to investigate the implications of ADM systems for case workers’ self-perception and discretion (Ranerup & Henriksen, Citation2019, Citation2020; Svensson, Citation2020), little research has been conducted on the everyday practices of integrating complex algorithmic systems in the mundane practices that relate to welfare provision. Critical algorithm and automation studies are currently merely beginning to consider the public sector and welfare state institutions and are often focused on the US and the UK context (Eubanks, Citation2017; Reisman et al., Citation2018). Further, the discussion and preliminary research on automated decision-making has, thus far, been speculative (e.g., Bucher, Citation2017a; Zarsky, Citation2016).

Socio-technical imaginaries in the making and the struggle for mundanization

In Science and Technology Studies, socio-technical imaginaries are one of the ways to engage with questions around technologies and their social repercussions as well as how they are shaped by the social. The major definition of socio-technical imaginaries as proposed by Sheila Jasanoff (Citation2015) refers to imaginaries that are

collectively held, institutionally stabilized and publicly performed visions of desirable futures (or of resistance against the undesirable), and they are also animated by shared understandings of forms of social life and social order attainable through and supportive of advances in science and technology. (p. 19)

As Ben Williamson argues socio-technical imaginaries are not only mere fantasies, but they are developed ‘in science laboratories and technical R&D departments sometimes, through collective efforts, become stable and shared objectives that are used in the design and production of actual technologies and scientific innovations– developments that then incrementally produce or materialize the desired future’ (Williamson, Citation2018, p. 222). They can act as models for the shaping of and implementation of technological developments, most often materializing as tech pilot projects that are partly performed outside usual institutional norms and policies.

Socio-technical imaginaries are future visions that sometimes materialize and are translated into concrete practices. Astrid Mager and Christian Katzenbach (Citation2020) remind us that they are always also contested and under negotiation. While socio-technical imaginaries allow us to explore desired futures, the concept is less helpful to conceptualize struggles that emerge in defining what certain technologies actually are and do. This process of meaning making of technology is not at all straightforward as, for example, Taina Bucher (Citation2017b) has demonstrated in her analysis of discussions about algorithmic failures in social media. The articulation of what technology means and does, is always also translational work between different sectors as Michael Hockhull and Marisa Leavitt Cohen (Citation2020) show. They argue that corporations active in the tech sector enact socio-technical imaginaries of the digital future through producing hot air and the aura of technological cool at intersectoral conferences and trade shows with the aim of pushing digital technologies into, for example, the public sector.

The meaning making around technology is not only related to how we imagine technology to work with and for us, but also which aspects we ignore in order to develop mundane, workable understandings of complex systems (Bowker & Leigh Star, Citation1999; Gitelman, Citation2008; Peters, Citation2015). Robert Willim (Citation2017) has defined this process as mundanization. With reference to domestication theory (Morley & Silverstone, Citation1990; Silverstone, Citation2005) that has conceptualized the integration of new technologies in our everyday lives – the taming of new media – he argues that in order to be able to establish mundane uses of technologies, we have to forget and ignore aspects of these systems. Part of this process are not only lay theories of how technology works, but also struggles about defining what technology as such is and does. The definition of what a specific technology is and does in turn has implications on how technology is integrated in, for example, legal frameworks and institutional structures. At the same time, successful technologies are often considered as hidden or invisible infrastructures that slip from our consciousness (Star & Ruhleder, Citation1996; Willim, Citation2019). Struggles on the meaning making of and around technologies that is expressed through conflicting definitions and access renders technology that is going through the process of mundanization visible. While mundanization as a process involves different forms of meaning making including practices of highlighting and forgetting specific technological aspects, I consider socio-technical imaginaries as one way of developing mundane understandings of new technologies, hence as specific forms of mundanization.

Approaching the mundanization of ADM

Tracing the socio-technical imaginaries that are mobilized in the process of mundanization, the material for this article consists of three major sources; firstly, interviews with a case worker and the project leader at Trelleborg municipality as well as actors involved in the litigation cases, secondly, an analysis of documents that emerged as part of the automation project and the litigation processes and thirdly, news pieces reporting on the Trelleborg model and the litigation cases:

In order to follow the negotiation process of what ADM in public services is and does, I have interviewed the automation unit manager and a civil servant at Trelleborg municipality. Furthermore, I have interviewed Simon Vinge at the Union SSR, who has submitted the appeal to the Parliamentary Ombudsman about the process of the litigation case. Vinge also shared documentation of the litigation process including exchanges with the Parliamentary Ombudsmen and Trelleborg municipality.

Furthermore, the decision by the court of appeal is part of the analysis. It was issued after Fredrik Ramel submitted an appeal in connection with a freedom of information request to gain access to the source code of the RPA software. The litigation process as well as a subsequent analysis of the material delivered to other journalists was, furthermore, detailed in a blog post by the data journalism platform J++ that investigated the decision-making algorithm in Trelleborg after the decision by the court of appeals and discovered that sensitive data were delivered to journalists together with the software source code. The long-read blog post serves as contextualizing material for the analysis here. Moreover, opinion pieces by the involved parts, in particular Trelleborg municipality and the Union of Professionals, are part of the contextualizing material as well as a report evaluating a best-practice project preparing other municipalities to implement a similar decision model as Trelleborg.

The material was analyzed in terms of different definitions of ADM systems that were suggested by the involved actors with a specific focus on what the implications of specific definitions are and how they feed into the process of mundanization.

ADM as decision support system and humanizing ADM

Trelleborg municipality defines automated decision-making as automated handling of applications and considers rule-based algorithms as decision support systems rather than automated robots to which tasks are fully delegated (Interview with project leader Trelleborg municipality, 17 October 2018). Even if algorithms are issuing decisions, every case has an assigned civil servant who is formally accountable for all decisions involved, as the project leader at Trelleborg municipality argues. She also argues that social benefit decisions are contingent on the availability of the applicant for the job market. The full evaluation of this criterion is the responsibility of civil servants and not the algorithms. In that sense, the municipality argues for a broad definition of decision support systems that includes fully automated sub-decisions, but where the overall responsibility is with the assigned civil servant. The project leader argues

So what is automated decision-making actually? This is the question. In our process, when we refer to social benefits, this is mainly a question whether you are available for the job market or not. And the evaluation of this question, this decision, if you are available or not is taken in job market process by a civil servant. And then this decision is taken to a higher organizational level and becomes part of decision by the public agency. So, in that sense, we do not have fully automated decisions. (Interview with project leader Trelleborg municipality, 17 October 2018)

During the interviews there emerged, however, also a more mundane form of definitional work. In mainstream media, the algorithm implemented in Trelleborg was initially called Ernst. The civil servant I interviewed recounts that

Ernst, no we do not call it like that anymore. That was a working name that we had, kind of. Just for us to better understand “what is this actually”? And to a certain degree it was some kind of robot, but actually an algorithm. But to make the whole thing a little bit livelier, so when I worked with a working group on this and we had a brain storming day where we were supposed to discuss what we are going to do we kind of … in order to be able to relate to something, and it is kind of difficult to relate to an algorithm, we came up with this exercise. Like a collective drawing exercise of the algorithm on a big flip chart paper, kind of. One person drew one part and then the next person drew another. In that way, we kind of developed a picture. And were like, so this is what you look like and he kind of was born then. And then it was our former head of administration who came up with that he should be called Ernst. But this is nothing we are still using. This was kind of in the beginning of everything. (Interview with civil servant Trelleborg municipality, 17 October 2018)

Yes. I think we have taught ourselves that we should speak of automated handling, but in the beginning, it was that we said, ‘it is a robot’ and the thing with the name. And sometimes we can still speak of producing a report with help of the robot, but actually we are talking about automation. There is no R2D2 who walks around the corridor, but it is a computer as such. But often it is, maybe it is easier to understand if you call it a handling robot or something like that. (Interview with project leader Trelleborg municipality, 17 October 2018)

In the email signature image that reads ‘When robots take care of the processing, the municipality takes care of the citizens,’ citizens are implied as the beneficiary of automation (see ). However, in the automation process they are hardly visible. The project leader and civil servant I interviewed, argued that nothing really changed for the citizens. They receive the same service and have the same accessibility with the e-service platform. Often, they do not even realize that the municipality has automated parts of the processing of applications except that they receive decisions faster, which is in their own interest according to the interviewees. A website instructing residents on how to apply for social benefits mentions Robotic Process Automation (RPA) that is used for tasks that can be taken care of in a cheaper, faster and more robust way by machines than by people. It is also argued that ‘the robot’ executes all tasks in the same manner as a case worker (Trelleborg municipality, Citation2020). Citizens have not been part of the development process, while civil servants have been filmed, interviewed and participated in workshops prior to the coding and implementation, also to establish a feeling of participation in the development process as the project leader argued during the interview. The civil servant acknowledges this and is very proud to ‘be an active part of this technological development and to be first in Sweden doing this. To be at the forefront’ (Interview with civil servant Trelleborg municipality, 17 October 2018).

Figure 1. Email signature image Trelleborg municipality, 2019. ‘When robots take care of the processing, the municipality takes care of the citizens’.

However, with increased national and international discussions on the role of algorithms in everyday life, journalistic and oversight investigations of automation in the public sector emerged. Both journalists, but also unions for professionals that are affected by forms of cognitive automation such as the Trelleborg project became active proponents in redefining automated decision-making and the algorithms involved as public records that can and should be accessible by the public. Two major litigation cases around the Trelleborg automation project emerged. In both cases, the algorithm and automated decision-making was defined slightly differently pointing to the contested character of the process of mundanization through definition.

ADM as code

In the first case, Fredrik Ramel a journalist at Swedish Public Radio, requested access to the source code of the software on which the automation of decisions at Trelleborg municipality is based. After an initial discussion with Trelleborg municipality, he reached out to the Danish software company who directed him back to Trelleborg municipality who owns the software. After that he formally requested the source code from the municipality arguing that

with support of chapter 2 of the Freedom of the Press Act on the principle of public access to official records, I would like to request the source code that is the foundation for the algorithm-based software that Trelleborg municipality uses for support their decisions on social benefits for example welfare support. (from official email to Trelleborg municipality quoted in the decision by the Court of Appeals, 21 February 2020)

The software was developed for the specific needs of the municipality who now owns it. It is hence not a licensed software product that is still owned by a commercial company that has the software at its disposal for commercial interests. Furthermore, the court has reached to the opinion that no individuals will be harmed if the source code is shared with Fredrik Ramel as requested. Hence, the appeal should be allowed. (from the decision by the Court of Appeal, 21 February 2020)

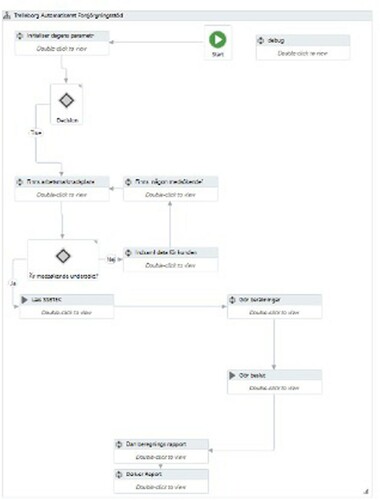

ADM as decision tree and interface

In the second litigationFootnote3 case, Simon Vinge chief economist at the Union for Professionals (Akademikerförbundet SSR) did not request access to the source code of the software for automated decisions but requested ‘meaningful information’ on how decisions are made with the help of the algorithmic system. In the process that started in June 2018, he had several conversations and meetings with representatives from Trelleborg municipality to discuss what meaningful information in relation to the algorithmic system might mean. He was shown a short film that explained the process of automation and reached the conclusion that he would like to receive screenshots of the program interface that is used by the civil servants for processing and administrating social benefit applications (see ). After waiting for almost a year without hearing back, he reported Trelleborg municipality to the Parliamentary Ombudsmen (PO) for delaying the response and the inability to provide meaningful information on how decisions are made with the help of the algorithm-based system. The report to the PO is based on a formulation in the State Public Report ‘Law for the support of the digitalization of public administration’ from 2018 (SOU 2018:25, Citation2018, p. 25) that emphasizes the right to ‘meaningful information on the logics behind as well as the expected consequences’ of automation for the individual person. The main argument is that the democratic rights of individual citizens are constrained if meaningful information about how automated decisions are executed are missing. The union furthermore argued that meaningful information must be accessible to and comprehensible for lay people without programing knowledge. According to the union, the municipality is lacking routines and definitions of what meaningful information encompasses in the case of automated decisions on social benefit applications. In an opinion piece published in Svenska Dagbladet, Simon Vinge and Heike Erkers (chair of the Union for Professionals) (2020-01-18) argue further that the delegation of decisions is not regulated in the delegation system of the municipality and hence the algorithm – or in their words robot – acts illegally. After reporting Trelleborg municipality to the Parliamentary Ombudsmen, Simon Vinge received the following screenshot illustrating the decision process:

Figure 2. Screenshot UiPath of the decision tree of Trelleborg municipality's Robotic Process Automation system.

In both cases, it is argued that different aspects of automated decision-making should be treated as public records and hence fall under the regulation on the principle of public access to official records, which was enacted in 1766 through the Freedom of Press Act. The negotiations of ADM as public record illustrate how new technical systems are integrated into existing legal frameworks by way of definition. At the same time, the two litigation cases illustrate mundanization in action or rather the negotiation of the meaning of technology while it is implemented and prior to it falling into mundane oblivion. Although digital infrastructures for public administration are largely build on the principles of invisibility, the current public discourse on the ‘dark side’ of digital welfare has contributed to attempts of making these digital infrastructures visible.

Conclusion

The article was introduced by highlighting a case of automated decision-making implemented by the British Department for Education and the controversy that emerged around it including public protests and the retraction of automated grading. The article itself engages with ADM systems used to administrate social benefit applications and public reactions to their use. Together the examples illustrate the breath as well as the multiplicity of implications of the use of algorithms in public administration and the emergence of what could be called the digital welfare state. At the same time, both cases also illustrate that the implementation of ADM systems is not only a question of technical infrastructures and workflow organization but involves meaning making processes. These meaning making processes are here captured with the notion of mundanization, namely the development of everyday relations to complex technical systems. Part of mundanization is developing definitions and understandings of what a specific technology is and does. In focusing on this question what technology is and does, the article engages with practices of mundanization that contribute to the stabilization of socio-technical imaginaries beyond stressing the powerful positions of specific actors. The contribution and relevance of the mundanization as theoretical entry point stresses small but important ways of acting on emerging technologies and infrastructures. In doing so, the article also considers the specific ways in which definitions of ADM systems are established that have implications for citizens and the public more generally.

The two cases of litigation against Trelleborg municipality underline the ongoing negotiation of what ADM is, what it does and what the consequences of introducing algorithmic systems in public administration are. ADM has in the process of mundanization been defined as a decision support system (by the municipality), a robot (by the municipality and public), software code (journalists) and public record (union representatives, journalists, court of appeals). The different definitions provided by the actors involved in the litigation processes illustrate important ways in which socio-technical imaginaries are co-produced. They also show that they are often conflictual, contested and unstable in nature as Sheila Jasanoff (Citation2015) has argued earlier. At the same time, they are performative, e.g., depending on which definition becomes the dominant one specific consequences for case workers (for example in terms of discretion) and residents (in terms of making informed choices and the possibility to appeal to decisions), but also in relation to the public (in terms of meaningful access to information on how decisions are made). Returning to the initial definition of socio-technical imaginaries as multiple and partly diverging from each other, it is not surprising that union representatives and journalists are involved in the negotiation process here. As ‘institutions of power’ they are in the position to highlight certain imaginaries over others and hence contribute to the stabilization and institutionalization of certain imaginaries over others.

At the heart of the argument is the negotiation of socio-technical imaginaries, as part of the process that can be described as a mundanization or the integration of complex technical systems into everyday practices through developing mundane understandings of these systems, for example through emphasizing specific aspects while ignoring others. In the case discussed here, mundanization takes shape in definitions developed for one specific ADM system. These definitions are provided by different actors – the municipality, journalists and union representatives – and consequently translate ADM into a language outside of the domain of computer scientists and software developers. Analyzing this process as mundanization bridges not only different stages of the implementation of complex technical systems, but also different fields of research that engage with automated decision-making.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Anne Kaun

Anne Kaun is professor in media and communication studies at Södertörn University, Stockholm, Sweden. Her research areas include media theory, mediated temporalities, algorithmic culture, automation and artificial intelligence from a humanistic social science perspective. Her work has appeared in among others New Media & Society, Media, Culture and Society, and Information, Communication & Society. In 2020, her co-edited book Making time for digital lives was published by Rowman & Littlefield [email: [email protected]].

Notes

3 Formally, this is not a case of litigation, but a report to the Parliamentary Ombudsman, who is not in the position to sanction any of the parties but issue statements, advisory opinions, initiate legal proceedings, recommendations or referrals (JO, Citation2014).

References

- Alfter, B. (2019). Denmark. In M. Spielkamp (Ed.), Automating society: Taking stock of automated decision-making in the EU. A Report by AlgorithmWatch in Cooperation with Bertelsmann Stiftung, supported by Open Society Foundations. AlgorithmWatch. Retrieved May 7, 2021, from https://www.algorithmwatch.org/automating-society

- Alston, P. (2019). Report of the Special rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights. A/74/48037. https://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=25156

- Ananny, M. (2016). Toward an ethics of algorithms. Science, Technology, & Human Values, 41, 93–117.

- Andersen, D. F., & Dawes, S. (1991). Government information management: A primer and casebook. Prentice Hall.

- Bleses, P., & Seeleib-Kaiser, M. (2004). The dual transformation of the German welfare state. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bonoli, G., & Natali, D. (2012). The politics of the ‘new’ welfare states: Analysing reforms in Western Europe. In G. Bonoli & D. Natali (Eds.), The politics of the new welfare state (pp. 3–20). Oxford University Press.

- Bowker, G., & Leigh Star, S. (1999). Sorting things out: Classification and its consequences. MIT Press.

- Brown, M. (2007). Understanding e-government benefits: An examination of leading-edge local governments. The American Review of Public Administration, 37(2), 178–197. https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074006291635

- Bucher, T. (2017a). ‘Machines don't have instincts’: Articulating the computational in journalism. New Media and Society, 19(6), 918–933. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444815624182

- Bucher, T. (2017b). The algorithmic imaginary: Exploring the ordinary affects of Facebook algorithms. Information, Communication & Society, 20(1), 30–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2016.1154086

- Choroszewicz, M., & Mäihäniemi, B. (2020). Developing a digital welfare state: Data protection and the use of automated decision-making in the public sector across six EU countries. Global Perspectives, 1(1), 12910. https://doi.org/10.1525/gp.2020.12910

- Dagenssamhälle. (2020). Känsliga uppgifter spreds via kod till biståndsrobot [Sensitive data were distributed via code of a benefit robot]. https://www.dagenssamhalle.se/nyhet/kansliga-uppgifter-spreds-kod-till-bistandsrobot-31911?fbclid=IwAR3LsYY0uxmI64JR9yDSh4sFgSlwj6HvCq2UY7ABPbPCWU3rqpjcLsrdfAk

- Dencik, L., Hintz, A., Redden, J., & Warne, H. (2018). Data scores as governance: Investigating uses of citizen scoring in public services. https://datajusticelab.org/data-scores-as-governance/

- Dencik, L., & Kaun, A. (2020). Datafication and the welfare state. Global Perspectives, 1(1), 12912.

- Dreyer, S., & Schulz, W. (2019). The general data protection regulation and automated decision-making: Will it deliver? https://www.bertelsmann-stiftung.de/en/publications/publication/did/the-general-data-protection-regulation-and-automated-decision-making-will-it-deliver

- DuGay, P. (2005). The values of bureaucracy. Oxford University Press.

- Edmiston, K. D. (2003). State and local e-government: Prospects and challenges. The American Review of Public Administration, 33(1), 20–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074002250255

- Engin, Z., & Treleaven, P. (2019). Algorithmic government: Automating public services and supporting civil servants in using data science technologies. The Computer Journal, 62(3), 448–460. https://doi.org/10.1093/comjnl/bxy082

- Eubanks, V. (2017). Automating inequality: How high-tech tools profile, police, and punish the poor. St Martin's Press.

- European Council. (2018). Declaration pf cooperation on artificial intelligence. Brussels.

- Gilbert, N. (2002). Transformation of the welfare state: The silent surrender of public responsibility. Oxford University Press.

- Gitelman, L. (2008). Always already new. Media, history, and the data of culture. MIT Press.

- Goodman, B., & Flaxman, S. (2016, June 23). EU regulations on algorithmic decision-making and a “right to explanation” [Paper presentation]. ICML Workshop on Human Interpretability in Machine Learning, New York.

- Government Offices of Sweden. (2018). National approach to artificial intelligence. Ministry of Enterprise and Innovation. Retrieved May 7, 2021, from https://www.regeringen.se/4aa638/contentassets/a6488ccebc6f418e9ada18bae40bb71f/national-approach-to-artificial-intelligence.pdf

- Hemerijck, A. (2012). Two or three waves of welfare state transformation? In N. Morel, B. Palier, & J. Palme (Eds.), Welfare state? Ideas, policies and challenges (pp. 33–60). Polity Press.

- Ho, A. T.-K. (2002). Reinventing local governments and the e-government initiative. Public Administration Review, 62(4), 434–444. https://doi.org/10.1111/0033-3352.00197

- Hockenhull, M., & Cohen, M. L. (2020). Hot air and corporate sociotechnical imaginaries: Performing and translating digital futures in the Danish tech scene. New Media & Society, Online First, https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820929319

- Jasanoff, S. (2005). Designs on nature: Science and democracy in Europe and the United States. Princeton University Press.

- Jasanoff, S. (2015). Future imperfect: Science, technology, and the imaginations of modernity. In S. Jasanoff, & S.-H. Kim (Eds.), Dreamscapes of modernity: Sociotechnical imaginaries and the fabrication of power (pp. 1–33). University of Chicago Press.

- Justitieombudsmannen, JO. (2014). A Parliamentary Agency. https://www.jo.se/en/About-JO/The-Parliamentary-agency/2020-12-28

- Kaun, A., & Taranu, G. (2020). Sweden / Research. In F. Chiusi, S. Fischer, N. Kayser-Bril, & M. Spielkamp (Eds.), Automating society 2020. A Report by AlgorithmWatch in Cooperation with Bertelsmann Stiftung. AlgorithmWatch. Retrieved May 7, 2021, from https://automatingsociety.algorithmwatch.org

- Kaun, A., & Velkova, J. (2019). Sweden. In M. Spielkamp (Ed.), Automating society: Taking stock of automated decision-making in the EU. A Report by AlgorithmWatch in Cooperation with Bertelsmann Stiftung, supported by Open Society Foundations. AlgorithmWatch. Retrieved May 7, 2021, from https://www.algorithmwatch.org/automating-society

- Kayser-Bril, N. (2019). France. In M. Spielkamp (Ed.), Automating society: Taking stock of automated decision-making in the EU. A Report by AlgorithmWatch in Cooperation with Bertelsmann Stiftung, supported by Open Society Foundations. AlgorithmWatch. Retrieved May 7, 2021, from https://www.algorithmwatch.org/automating-society

- Kennedy, H. (2016). Post, mine, repeat: Social media data mining becomes ordinary. Springer.

- Kitchin, R. (2017). Thinking critically about and researching algorithms. Information, Communication & Society, 20(1), 14–29.

- Lawton, A. (2005). Public service ethics in a changing world. Futures, 37(2-3), 231–243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2004.03.029

- Layne, K., & Lee, J. (2001). Developing fully functional e-government: A four stage model. Government Information Quarterly, 18(2), 122–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0740-624X(01)00066-1

- Mager, A., & Katzenbach, C. (2020). Future imaginaries in the making and governing of digital technology: Multiple, contested, commodified. New Media & Society, Online First, https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820929321

- Mayer-Schönberger, V., & Cukier, K. (2013). Big data: A revolution that will transform how we live, work, and think. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- Morley, D., & Silverstone, R. (1990). Domestic communication – technologies and meanings. Media, Culture & Society, 12(1), 31–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/016344390012001003

- Mosco, V. (2017). Becoming digital: Toward a post-internet society. Emerald.

- O'Neil, C. (2016). Weapons of math destruction: How big data increases inequality and threatens democracy. Crown.

- Peters, J. D. (2015). The marvellous clouds. Towards a philosophy of†elemental media. The University of Chicago Press.

- Pollitt, C., Van Thiel, S., & Homburg, V. (Eds.). (2007). New public management in Europe. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Rakar, F. (2018). Lärprojekt Trelleborgsmodellen - Från Rebell till Modell [Project Trelleborg model – From rebel to model] www.moten.trelleborg.se/arbetsmarknadsnamnden/agenda

- Ranerup, A., & Henriksen, H. Z. (2019, January 30–31). Robot takeover? Analysing technological agency in automated decision-making in social services [Paper presentation]. 16th Scandinavian Workshop on e-Government, University of South-Eastern Norway.

- Ranerup, A., & Henriksen, H. Z. (2020). Digital discretion: Unpacking human and technological agency in automated decision making in Sweden’s social services. Social Science Computer Review. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439320980434

- Reisman, D., Schultz, J., Crawford, K., & Whittaker, M. (2018). Algorithmic impact assessments: A practical framework for public agency accountability. https://ainowinstitute.org/aiareport2018.pdf

- Sandvig, C., Hamilton, K., Karahalios, K., & Langbort, C. (2016). Automation, algorithms, and politics| when the algorithm itself is a racist: Diagnosing ethical harm in the basic components of software. International Journal of Communication, 10, 19.

- Silverstone, R. (2005). Domesticating domestication. Reflections on the life of a concept. In T. Berker, M. Hartmann, Y. Punie, & K. J. Ward (Eds.), Domestication of media and technology (pp. 229–248). Open University Press.

- Skocpol, T. (2003). Diminished democracy. From membership to management in American civic life. University of Oklahoma Press.

- SOU 2018:25. (2018). Juridicial support for the digitalisation of public administration [Juridik som stöd förförvaltningens digitalisering]. Retrieved May 7, 2021, from https://www.regeringen.se%2F495f60%2Fcontentassets%2Fe9a0044c745c4c9ca84fef309feafd76%2Fjuridik-som-stod-for-forvaltningens-digitalisering-sou-201825.pdf&usg=AOvVaw0uWx39jBfmo7E6yzdFAVV6

- Spielkamp, M. (2018). Automating society: Taking stock of automated decision-making in the EU. https://algorithmwatch.org/en/automating-society/

- Star, S. L., & Ruhleder, K. (1996). Steps towards an ecology of infrastructure: Design and access for large information spaces. Information Systems Research, 7(1), 111–134. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.7.1.111

- Sumpter, D. (2018). Outnumbered: From Facebook and Google to fake news and filter-bubbles – the algorithms that control our lives. Bloomsbury.

- Svensson, L. (2020). Automatisering till nytta eller fördärv? [Automation to benefit or ruin?]. Socialvetenskaplig Tidskrift, 26(3-4), 341–362. https://doi.org/10.3384/SVT.2019.26.3-4.3094

- Swedish Television. (2018). Contested Robot decides who gets benefits in Trelleborg [Omdiskuterad robot avgör vem som får stöd i Trelleborg]. Retrieved May 7, 2021, from https://www.svt.se/nyheter/lokalt/skane/robot-avgor-vem-som-far-stod

- Trelleborg municipality. (2020). This way a digital application is handled [Så här hanteras en digital ansökan]. https://www.trelleborg.se/omsorg-och-hjalp/ekonomiskt-stod/ekonomiskt-bistand-forsorjningsstod/sa-har-hanteras-en-digital-ansokan/

- Van der Wal, Z., De Graaf, G., & Lasthuizen, K. (2008). What's valued most? Similarities and differences between the organisational values of the public and the private sector. Public Administration, 86(2), 465–482. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2008.00719.x

- Veale, M., & Brass, I. (2019). Administration by algorithm? Public management meets public sector machine learning. In K. Yeung & M. Lodge (Eds.), Algorithmic regulation. Oxford University Press.

- The Verge. (2020). UK ditches exam results generated by biased algorithm after student protests. Retrieved May 7, 2021, from https://www.theverge.com/2020/8/17/21372045/uk-a-level-results-algorithm-biased-coronavirus-covid-19-pandemic-university-applications

- Williamson, B. (2018). Silicon start-up schools: Technocracy, algorithmic imaginaries and venture philanthropy in corporate education reform. Critical Studies in Education, 59(2), 218–236. https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2016.1186710

- Willim, R. (2017). Imperfect imaginaries: Digitisation, mundanisation, and the ungraspable. In G. Koch (Ed.), Digitisation: Theories and concepts for empirical cultural research (pp. 53–77). Routledge.

- Willim, R. (2019, October 14). From a talk at: Man or machine? Who will decide in the future [Paper presentation]. Future Week at Lund University, Lund.

- Yeung, K. (2018). Algorithmic regulation: A critical interrogation. Regulation & Governance, 12(4), 505–523. https://doi.org/10.1111/rego.12158

- Zarsky, T. (2016). The trouble with algorithmic decisions: An analytic road map to examine efficiency and fairness in automated and opaque decision making. Science, Technology and Human Values, 41(1), 118–132. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243915605575