ABSTRACT

‘Checking in’ at or ‘tagging’ oneself to various places on social media constitute online representations that contribute to the classification, or ‘making’, of places. At the same time, users are also classified based on what they (show that they) do where. In this paper, we deploy Bourdieusian cultural sociology to the realm of place-exposing geomedia practices to understand social reproduction on social media. The study uses multiple correspondence analysis on a national survey deployed in Sweden (n=3,902). Various place-exposing practices are analyzed in relation to the contemporary Swedish class structure. Results reveal a connection between various forms and volumes of capital and the places that people visit and chose to put on display for online audiences. We are thus able to verify how the socio-technological regime of geomedia, with its new arenas for online exposure, extends deep-seated dynamics of socio-cultural reproduction and even reinforces the classificatory linkages between spatial appropriation and social identity work.

Introduction

Geomedia technologies such as social media allow people to perform their identities by showcasing their whereabouts and cultural activities to their social networks (Schwartz & Halegoua, Citation2015). ‘Checking in’ at or ‘tagging’ oneself to various places constitute online representations that contribute to the classification, or ‘making’, of places (e.g., Boy & Uitermark, Citation2017). At the same time, users are also classified based on what they (show that they) do where. In this paper, we deploy Bourdieusian cultural sociology to the realm of place-exposing geomedia practices to understand social reproduction on social media. By ‘place-exposing geomedia practices’ we mean digital practices that epitomize the new socio-technological regime of geomedia (see below) and expose certain (types of) places.

Geomedia practices that expose specific places, such as ‘checking in’ at a museum or sharing pictures from a sports event via a social networking site, provide a novel entry point for studying the composition of people’s cultural and lifestyle repertoires – what people value and what they choose to do with their time. These practices connect lifestyles to place, allowing us to pose the question of ‘where?’ in relation to cultural stratification and symbolic power. Indeed, the literature on cultural stratification and taste is marked by a focus on which practices people rely on to mark social status (Bourdieu, Citation1979 [1984]; Flemmen et al., Citation2018), and how various modes of consumption (such as ironic consumption) allow symbolic boundary drawing (Jarness, Citation2015). The body of literature concerned with the what and the how of culture consumption connects, for instance, the appreciation of ‘high-brow’ culture and ironic consumption of ‘low-brow’ culture to privileged strata of the population. The question of where remains largely unanswered (Koehrsen, Citation2019). Here, we study the significance of place in relation to cultural distinctions and we discern how cultural distinctions in the era of geomediatization contribute to the (re)production of not only social positions but also of space and place (cf. Lefebvre, Citation1974/1991).

The growing popularity, the ‘everydayness’, of place-exposing geomedia practices also implies that mediations of place become increasingly important to social stratification processes. Under the regime of mass media circulation, people rarely reached beyond their closest circles with pictures, postcards or other types of information telling where they were and what they did. Such sharing processes also took time. Digital place-exposing practices, by contrast, constitute and represent lifestyles that people deliberately and immediately want to communicate to an online audience of family, friends, colleagues, and acquaintances. In this sense, these practices are overt and more ‘conspicuous’ (Veblen, Citation1899 [2008]) than the practices normally studied in cultural sociology (which is not always in sync with our new media landscape), and are likely to have a more direct and expanding impact on the classification of lifestyles as well as places. The regime of geomedia thus produces what we see as an expanding symbolic battlefield (see also Fast, Johan, & André, Citation2021).

Along these lines, our study draws on Bourdieusian sociology to study the social stratification of place-exposing geomedia practices. We are specifically concerned with the class-bound character of the places that people with different volumes and compositions of economic, cultural and social capital chose to ‘check in’ at or ‘tag’ themselves to on social media. The study uses multiple correspondence analysis (MCA) on a national survey (n = 3902) with the adult Swedish population in order to delineate the Swedish space of social positions. In a second step, we study various place-exposing digital practices in relation to different class positions. The study contributes to the understanding of symbolic power in the era of conspicuous, locative, media that has put place and the question of ‘where?’ at the center of cultural distinction.

Geomedia practices and the mutual classification of place and self

In this article, we conceive of social media as part of a broader socio-technological regime characterizing media culture of the twenty-first century: geomedia (e.g., McQuire, Citation2016; Thielmann, Citation2010). By the term we want to highlight the coming together of connective, representational and logistical affordances (cf. Hutchby, Citation2001) within digital media technologies and the social norms and values that accompany this shift (Fast, Ljungberg, & Braunerhielm, Citation2019; Jansson, Citationforthcoming). Geomediatization, in turn, refers to the normalization of this regime in society and culture (Fast, Jansson, Lindell, Ryan Bengtsson, & Tesfahuney, Citation2018) – a transformation whereby people’s media practices become more closely woven into the production of space and place.

Let us be more concrete. In earlier stages of modernity, connective affordances, the ability to link people and places, marked technologies like the telephone and the telegraph. Representational affordances, in turn, were associated with, for example, photography and the camera. Logistical affordances, the ability to steer and organize people and activities in time and space, characterized time-tables, maps, clocks and so forth (Peters, Citation2008, Citation2015). Most media technologies thus attained a relatively clear bias as to what they were good for, even though their actual uses could vary to some extent over time and between different settings. Digital media, by comparison, have a greater tendency to converge and are thus generally less ‘pure’ (Jenkins, Citation2004). A social media platform like Instagram connects users instantaneously not only with other people but also, algorithmically, with certain types of activities, places and things, while at the same time enabling users to circulate representations of place and provide the exact locations of their whereabouts. To those possessing the right skills, geomedia thus makes the everyday management of space, place, mobility and distance increasingly simple and personal, nurturing the so-called spatial self (Schwartz & Halegoua, Citation2015). At the same time, however, geomedia entails sophisticated forms of automated surveillance and the exploitation of people’s spatial practices (e.g., Andrejevic, Citation2019).

Given this basic characterization, the impact of digital geomedia on the production of space and place can be understood along three complementary axes, corresponding to the above affordance types. First, extended connectivity makes people increasingly aware of other places, especially those visited and mediated by peers or automatically promoted by means of datafication (e.g., for leisure, tourism, and other forms of consumption) (cf., Van Dijck, Citation2013; Van Dijck & Poell, Citation2013). Mediated experiences of place are in this way increasingly specialized, tailored according to the norms and lifestyles of particular segments of the population. Second, the improved opportunities for media users to represent places in the way they like, taking numerous digital photos and enhancing them by means of filters and other digital tools, feed into the broader trend of aestheticization that defines modern consumer culture (Featherstone, Citation1991, pp. 66–72). Part of this trend is also the propensity, especially among young media users, to emplace themselves, that is, taking selfies in particular settings and then sharing these online as a form of recognition work (e.g., Dinhopl & Gretzel, Citation2016; Lo & McKercher, Citation2015). Third, locative media technologies, that is, ‘media of communication that are functionally bound to a location’ (Wilken & Goggin, Citation2015, p. 4), have turned located information provided through geotagging, check-in services, customer ratings, and so forth, into the norm (ibid., p. 5). The underlying technology, global positioning systems (GPS), is also vital to help people navigate through space and thus reaching, and representing, the ‘right’ places and the ‘right’ people and activities – while avoiding others (e.g., Boy & Uitermark, Citation2017; Frith & Kalin, Citation2016; Polson, Citation2016; Zukin et al., Citation2015).

What is crucial here, is that geomedia reinforces ‘self-making’ and ‘place-making’ as mutual processes of classification. This happens in two conflicting ways. On the one hand, there are growing opportunities for people to find, appropriate and share representations of space and place both online and in material geographies according to their individual preferences (e.g., Munar & Jacobsen, Citation2014; Özkul & Humphreys, Citation2015; Verhoeff, Citation2008). While it is certainly not a new thing that people seek out places that fit their own sense of identity and (desired) status, as shown, for example, in research on tourism, lifestyle migration and elective belonging and ‘emplacement’ (e.g., Benson, Citation2016; Correia & Kozak, Citation2012; Savage, Citation2010; Shani, Citation2019), the ability to more or less publicly link self with place as a matter of ‘spatial distinction’ (Marom, Citation2014, p. 1348) has multiplied with geomedia. On the other hand, the nature of algorithmic culture (Striphas, Citation2015) is such that individuals – as aggregated digital subjects (Goriunova, Citation2019) – are automatically steered toward certain destinations, literally as well as metaphorically speaking. Geomedia can thus be seen as a logistical machinery (cf. Rossiter, Citation2015) that contributes to the symbolic reproduction of social as well as geographical spaces and thus to a collectivization of lifestyle-related choices. Granted, the latter tendency may evoke resistance and counter-tactics among class-fractions that feel their autonomy and capacity for spatial distinction are threatened.

Against this background, by geomedia practices we mean practices conducted by means of online digital media, especially social media, and resonating with the above characteristics (see also operationalization in Data and method). Geomedia practices, we argue, potentially constitute an increasingly important field of symbolic struggle. This pertains especially to those geomedia practices that are place-exposing, that is, linking a particular agent and activity to a particular place (a named location, such as, the local gym or a particular tourist resort), or type of place (categories like ‘supermarket’ or ‘hamburger restaurant’). It should be stressed here that place-exposing practices are not necessarily locative; anyone may, for example, share a picture from a wilderness hike or a shopping mall (certain types of places) on social media without revealing the exact location. Place-exposing practices, whether locative or not, contribute – also with their absence – to the overt classification and positioning of places, agents and activities (including geomedia practices per se) in social space. In order to grasp what this means in terms of underlying power relations we should apply a Bourdieusian analytical framework.

Distinctive practices in the age of geomedia

We draw on the work of Pierre Bourdieu in order to understand geomedia practices – especially those exposing (and thus directly part of producing) specific places – in relation to social space and its wider power relations. While other scholars have provided frameworks or arguments in relation to the study of social and cultural stratification in late modernity (see e.g., Chan, Citation2019), Bourdieu is unmatched in that he provides a theoretical-methodological program for this endeavor. Bourdieu’s argument is not only – or primarily – an empirical one (e.g., on the homology between the space of social positions and the space of lifestyles). He also forwards an epistemology for the study of the correspondences between a set of objective properties, or capital, and subjective orientations in the social world, such as lifestyles and cultural practices (Bourdieu, Citation1979 [1984]; Citation1989; Lizardo & Skiles, Citation2015; Rosenlund, Citation2015, Citation2019). Accordingly, practice (in the widest sense of the word) is understood in relation to the social histories of agents. Agents move about in various social fields, including the family, the wider social space, and other fields, that inculcate them and provide them with access to various forms of capital (Bourdieu, Citation1979 [1984]; Citation1996). Agents that share similar social histories tend to form similar ways of orienting in the world. For Bourdieu, then, social reproduction is not imposed ‘from above’, but results from the interplay between individuals’ socially shaped orientations in the world – their habitus – and the field in relation to which it operates (Bourdieu, Citation1979 [1984]; Citation1990).

In order to capture the relationship between individuals’ possession of resources and their cultural practices and lifestyles, Bourdieu relied on correspondence analysis. Bourdieu held that this technique, which inductively extracts the most prevalent structures in a dataset and presents them in a synoptic map, ‘corresponds exactly to what, in my view, the reality of the social world is’ (Bourdieu & Wacquant, Citation1992, p. 96). In contrast to more established statistical techniques, such as regression analysis – which forces data into a preconceived model – correspondence analysis first establishes, inductively, the structure of the social field that is being studied. Ideally, all resources that function as capital in a field – primarily defined as economic, cultural and social capital – are operationalized and included in the analysis. Bourdieu and others have found that the main social divisions in ‘modern and differentiated societies’ (Rosenlund, Citation2015, p. 157) tend to revolve around volume and composition of capital (see also Rosenlund, Citation2019). The correspondence analysis thus creates a statistical representation of a social field (Duval, Citation2018). Practices and preferences – that is, lifestyle manifestations – are then projected onto the (statistical representation of the) field. The method is relational in nature, and studies differences and similarities in terms of distances in the field; properties found far away from each other indicate a social distance (Hjellbrekke, Citation2019). Systematic overlaps in the distribution of capital and lifestyles are framed as instances of social reproduction by way of habitus (Rosenlund, Citation2015).

In recent decades this approach has gained traction outside of France (Savage & Silva, Citation2013). A range of studies have applied Bourdieu’s program in contemporary Western societies and found a space of social positions structured primarily of volume and composition of capital, and that lifestyles are shaped by both these dimensions (see, e.g., Flemmen et al., Citation2018; Hjellbrekke et al., Citation2015; Prieur et al., Citation2008; Rosenlund, Citation2019). This goes for media practices as well (Hovden & Moe, Citation2017; Lindell, Citation2018; Lindell & Hovden, Citation2018).

It is true that Bourdieusian sociology tends to refrain from formulating and testing hypotheses (for an exception see Gayo et al., Citation2018) – not least because Bourdieu’s endeavor was an inductive one. However, one should not ignore the growing body of research (see e.g., Flemmen et al., Citation2018; Hjellbrekke et al., Citation2015; Prieur et al., Citation2008; Rosenlund, Citation2019; Lindell, Citation2018; Lindell & Hovden, Citation2018) that has applied his approach and found that (1) the class structures of many contemporary societies resemble the one proposed by Bourdieu (Citation1979 [1984]) and that (2) media and culture consumption tend to connect to that class structure. We thus have reasons to pose and test – albeit without breaking with the inductive construction of the social space via MCA – the following two hypotheses:

H1: Volume of capital and capital composition will be the two primary dimensions of social differentiation in contemporary Sweden.

H2: Social agents’ place-exposing geomedia practices will vary significantly with both volume of capital and capital composition.

In relation to the debate on the character of cultural distinction in late modernity Koehrsen (Citation2019) rightly points out that focus tends to be put either on the what (e.g., ‘low-brow’ or ‘high-brow’) or the how (e.g., ironic consumption and ways of preferring [see, e.g., Daenekindt & Roose, Citation2017; Jarness, Citation2015; see also Peters et al., Citation2018]). Less is known about the where, that is, the place-related contexts in which cultural distinctions are played out (Koehrsen, Citation2019). Thus, Bourdieu’s (Citation2000, pp. 134–135) observation that social and physical space tend to overlap and intermingle, has received little empirical attention outside of certain strands of urban studies (see e.g., Marom, Citation2014; Wacquant, Citation2007).

Geomedia technologies allow people to perform their identities by showcasing their whereabouts and cultural activities to their social networks (Schwartz & Halegoua, Citation2015; Wilken & Humphreys, Citation2019). In relation to Bourdieu’s sociology, place-exposing geomedia practices, such as ‘checking in’ at a museum or sharing a photo of a sports event via a social networking site, are interesting in three respects. First, the study of such practices allows for a contribution to the well-established tradition of mapping the contents of people’s cultural and lifestyle repertoires – what people value and what they choose to do with their time (Bourdieu, Citation1979 [1984]). This connects to our hypothesis regarding social reproduction via media and culture consumption. At the same time, and secondly, place-exposing geomedia practices link lifestyles to places, and allow posing the question ‘where?’ in relation to cultural stratification and symbolic power (Koehrsen, Citation2019). The focus upon place-exposing geomedia practices allows us to take into account that lifestyles take place, so to speak. Third, and relatedly, practices such as ‘check-ins’ on social media are lifestyle manifestations that people deliberately, even conspicuously, communicate to an online audience of family, friends, colleagues and acquaintances. The affordances of geomedia, which includes the representational ability to showcase lifestyles in an explicit manner, imply that cultural distinction assumes a more prevalent ‘front-stage’ character (Goffman, Citation1959; Meyrowitz, Citation1986).

At present, we do not know much about cultural distinction in relation to these geomediatized cultural practices. Hargittai and Litt (Citation2013) suggest that class matters indirectly, via digital skills and media literacy, for how people negotiate the various ‘context collapses’ (boyd, Citation2011; Davis & Jurgenson, Citation2014) on social media – meaning that previously separated social arenas merge on social networking sites. Others, however, hold that the less privileged and ethnic minorities deploy ‘respectability politics’ to maintain a facade on social media that corresponds with the expectations of a white middle class (Pitcan et al., Citation2018). This latter view constitutes the ‘null hypothesis’ – version of our second hypothesis – which relies on Bourdieu’s (Citation1990) argument that practice stems from habitus and thus tends to reproduce social positions. Implicit in Pitcan et al.’s (Citation2018) approach is, instead, a view that practice (such as behavior on social media) results from the deliberate weighing of risks against gains. From this perspective, one would expect culturally distinctive practices to be less prevalent on social media than elsewhere, precisely because agents are assumed to act in a calculated manner in relation to their social networks, and since showcasing dubious, or ‘low-brow’ tastes in front of an online audience involves a certain ‘risk’.

By focusing upon different types of places that people across social space ‘check in’ to, ‘tag’ themselves to, or share photos from, we are allowed to study both the what and the where of overt, semi-public, cultural distinctions, and contribute to the ongoing debates around self-performance and cultural distinction on social media. The next section details our methodological approach.

Data and method

This study is part of a project on the mediatization of everyday life – Measuring mediatization. A key concern of the project is to grasp how mediatization plays into social stratification processes. Between February and March 2019, the project deployed a survey via the research institute Kantar-Sifo’s web-panel consisting of over 60,000 people. The survey was sent to 12,481 adult Swedes (18–90 years old), among these, 3902 individuals answered the survey, leaving the response rate at 31%.

Like in a previous publication on digital disconnection (Fast et al., Citation2021), we use this survey to analyze mediatization in relation to the Bourdieusian social space. We do this by using MCA on variables that capture individuals’ holdings of social, economic and cultural capital. As outlined above, MCA is the inductive statistical technique that Bourdieu favored, since it extracts structures from the data rather than imposing a preconceived model upon it, and since results are presented in a spatial, multivariate and relational manner, where distance indicates social distance and distinction (Rosenlund, Citation2015).

In following recent MCA-oriented studies of the Scandinavian societies (e.g., Flemmen et al., Citation2018; Lindell, Citation2018; Rosenlund, Citation2015) we used nine variables to construct the Swedish space of social positions. This first step of the analysis allowed us to test Bourdieu’s model of social stratification in a contemporary Swedish setting (Hypothesis 1). Cultural capital was measured with (1) respondents’ educational levels, (2) number of books at home, (3) type of education (for example, humanities/arts, social care or transportation), (4) parents’ educational levels and (5) levels of exposure to various cultural artifacts at home when growing up. Economic capital was measured with (1) monthly income, (2) economic assets and (3) ownership of country/summer house. Social capital was measured by asking respondents if they were (1) members of any board. While other indicators of social capital can be used (for instance friends’ levels of education and occupational status) we followed previous research designs (including Bourdieu’s analyses in Distincion) and put primary focus on cultural and economic capital (cf. Flemmen et al., Citation2018; Lindell Citation2018; Lindell & Hovden, Citation2018). in the appendix provides a full disclosure of the active variables. In order to test H1 beyond establishing whether the two most important dimensions of social differentiation are found in volume and composition of capital, we studied the positions of various age cohorts, genders, working sectors (private–public) and residential areas (rural–urban) in social space. This allowed a comparison with previous research and to further test the validity of the model in relation to H1.

Once the social space had been constructed, we projected place-exposing geomedia practices as supplementary variables in the space. We were, in other words, allowed to study the class-specific coordinates of these practices, and subsequently able to test H2 regarding cultural distinction on social media. To this end, our respondents were asked if they had physically visited and ‘checked in’, ‘tagged’ themselves, or shared a photo on social media from each of the following nine places during the last 12 months: a museum, an art exhibition, a conference, a hotel, a camping-site, a shopping mall, a market hall, a nature reserve, and a theater. Answers were given according to a nominal scale: (1) has not visited the particular place, (2) has visited and ‘checked in’, ‘tagged’ or shared a photo of the given place, and (3) has visited the place but not ‘checked in’, ‘tagged’ or shared a photo. This study design captured both the what and the where of cultural distinction (Koehrsen, Citation2019) and allowed us to identify distinctions both outside of social media (who visits which places?) and on social media (who chooses to expose their visits to particular places in front of a social media audience?).

While the present study design allowed us to grasp how geomedia practices – through the mutual classification of places, activities and agents – form part of social stratification processes, there are some limitations worth highlighting. First, the sample is slightly skewed toward highly educated, and older, people. Second, we are here concerned with the extent to which social groups share their visits to different places on social media, but the data prevents us from knowing who they share this information with. In other words, we cannot capture if, for instance, a certain social group is more prone to have stricter privacy settings on their social media accounts and, in effect, if the information they share only reaches a specified audience (e.g., all friends on Facebook or only colleagues). Third, while we bridge previous work in cultural sociology that has studied the what and the where of cultural distinction on separate fronts, we are unable to study more qualitative aspects, that is, the how-question (Jarness, Citation2015).

Results

In this section, we go through the findings of our correspondence analyses. We first present the composition of the Swedish social space (H1), and then turn to the positioning of different place-exposing geomedia practices in social space (H2).

Social space

In the first step of the analysis, we applied the Bourdieusian procedures of MCA to construct a space of social positions representing the structure of class relations pertaining to contemporary Swedish society. Building upon previous research on the Scandinavian class structures, our first hypothesis stated that this social space would be structured according to two main dimensions; capital volume and capital composition (economic vs. cultural capital). Only if H1 was confirmed, our analysis would be able to proceed with H2.

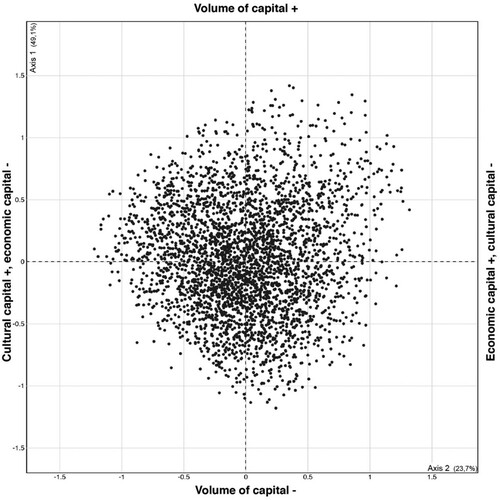

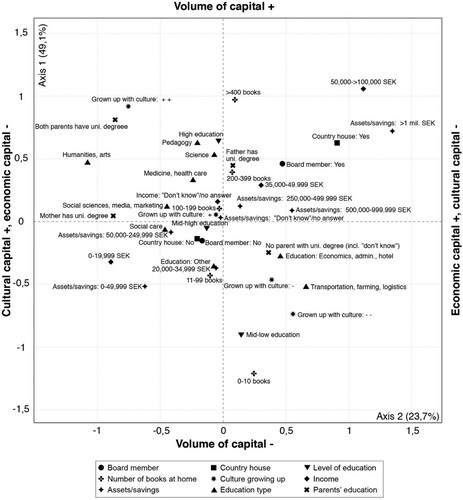

presents the coordinates of the respondents (the cloud of individuals), and presents the modalities pertaining to the active variables (the cloud of modalities). The MCA identified two main axes of differentiation in terms of class relations (see and A3 in the Appendix for details). Together they explain 73% of the variance amongst the variables and as such we have chosen not to focus upon the other dimensions (cf. Hjellbrekke, Citation2019).

Figure 1. The Swedish social space anno 2019. The cloud of individuals. MCA, axis 1 (volume of capital) and 2 (capital composition). Missing values have been omitted (n = 3693).

Figure 2. The Swedish social space anno 2019. The cloud of modalities. MCA, axis 1 and 2. Missing values have been omitted (n = 3693).

As shown in , the Swedish social space follows the anticipated structuring principles, found in previous research on the Scandinavian societies (Flemmen et al., Citation2018; Hjellbrekke et al., Citation2015; Prieur et al., Citation2008; Rosenlund, Citation2015; Citation2019; Lindell, Citation2018; Lindell & Hovden, Citation2018). Along the vertical axis, we see how different types of assets and positions express capital volume. In the upper half of the model, we find people with higher incomes, greater economic assets, higher educational levels and thus on more influential social positions. In the lower part of social space, by contrast, we find less privileged social groups that also stem from less privileged social backgrounds.

The horizontal axis, in turn, represents the composition of capital based on indicators of cultural capital (to the left) and economic capital (to the right). On the left side of the space cultural capital outweighs economic capital, whereas economic capital dominates on the right side of the space. This dimension verifies that different types of capital correspond to different educational trajectories – for example, social care and humanities vs. economics, administration and transportation – and that the force of habitus (predispositions based on social background) plays a reproductive role also in relation to the Swedish social space. These findings confirm previous studies of how social space is structured in Sweden (e.g., Broady, Citation2001; Lindell, Citation2018; Lindell & Hovden, Citation2018), and that – although it implies simplification – it is possible to speak of four ideal-typical class factions, or domains of social space: (1) the cultural middle and upper class (top-left), (2) the economic middle and upper class (top-right), (3) the working-class (bottom right), and, finally, (4) a domain of low volumes of capital where the lack of economic capital is most prevalent (for instance, this is where we find students in the midst of accumulating scholastic capital (bottom left)).

It is also worth commenting on how demographic variables correspond with our model of social space. While not displayed in the figure, these variables were studied as supplementary points in the space in order to ‘check’ the model against previous research. Age was positively associated with capital volume (older people have greater assets). Like in previous studies (Lindell & Hovden, Citation2018), Swedish men’s capital composition was generally speaking characterized more by economic capital compared to women, whereas women tend to be somewhat richer on cultural capital. Similarly, occupations in the private sector were associated with economic capital, while occupations in the public sector were linked to cultural capital (Broady, Citation2001). Altogether, our findings confirm H1.

Projection of geomedia practices in social space

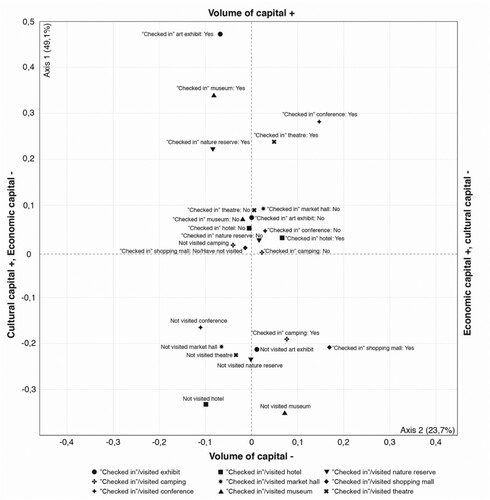

In light of empirically established cultural theory, our results concerning culture consumption – which places have or have not been visited () – are not surprising. All but two modalities of our place-exposing practices and visits are related to either both or one of the axes of differentiation levels that are statically significant (see , Appendix). It should be noted, however, that most modalities display only a modest distribution in social space (less than .5 deviations from the center of the space). Social media ‘checked ins’ at hotels and the reluctance to display a camping site visit are not significantly related to the Swedish class structure. Most people, regardless of their class position, seem inclined to showcase their hotel visits, while keeping possible visits to camping sites in the ‘back stage’ (cf. Goffman, Citation1959).

Figure 3. Place-exposing practices projected into the Swedish social space. The cloud of modalities. MCA, axis 1 and 2. Missing values (including not owning a smartphone) have been omitted (n = 3483).

Before turning to the distribution of geomedia practices in social space, let us take a look at which places people state that they actually claimed to have visited. The most apparent variations exist along the vertical axis, between the capital rich and the capital poor: those inhabiting the lower half of social space have typically not visited a theater, an art exhibit, a museum, a conference, a hotel, a nature reserve, or a market hall. The reverse is true for those in the upper half of social space, where we find the cultural and the economic middle and upper classes. Visits to art exhibits and museums correspond strongly with high volumes of capital, whereas visits to camping sites and shopping malls are more often undertaken by those with less capital – reflecting what Bourdieu (Citation1979 [1984], p. 56) calls ‘tastes of necessity’.

Along the horizontal axis, differentiating agents in terms of capital composition, we notice a discrepancy between the cultural and the economic middle/upper classes. While less than half of the modalities were statistically significantly explained by this axis (, Appendix), we can still see some tentative results and tendencies. The cultural middle and upper class seem relatively more inclined to visit art exhibitions, museums and nature reserves compared to the economic middle and upper class, which instead seems predisposed to visit conferences, hotels, theaters, and market halls. Our results also suggest that visits to camping sites and shopping malls are more frequent among individuals in the working class, that is, among those positioned in the lower right corner of social space, than among capital poor class fractions with more cultural orientation.

As for showcasing these whereabouts to an online audience, i.e., the place-exposing geomedia practices, we find that the capital rich are, overall, more inclined to check in at the places they claim to have visited. Thus, the capital rich not only visit art exhibits, museums, nature reserves, conferences and theaters more frequently; they also seem inclined to expose and broadcast these visits to others by communicating their presence at these places on social media. Relatedly, those visiting camping sites or shopping malls – i.e., people at less privileged positions, especially in terms of cultural capital (i.e., parts of the working class), also claim to have checked in at those venues. Again, the composition of capital plays a minor role, but the distinctions between, e.g., checking in at conferences (economic capital) at checking in at art exhibits and museum (cultural capital) are clearly in line with H2.

The capital rich’s inclination to undertake place-exposing geomedia practices represents an interesting pattern in light of our own parallel study on ‘digital disconnection’ practices and sentiments of ‘digital unease’, based on the same survey data (Fast et al., Citation2021). Our earlier findings show, among other things, that digital disconnection practices and feelings of discomfort with digital media correspond positively with high capital volumes, and with high volumes of cultural capital in particular. This is to say that the capital rich – and the cultural middle and upper class especially – is relatively more inclined to withdraw from digital media in various places and social contexts. Among other things, our previous results indicate that the cultural middle and upper class finds it important to disconnect from digital media when spending time in nature. Considering this, it is arguably surprising to find, in the present analysis, that this class fraction is nonetheless predisposed to check in on social media, when in nature as well as when in certain other places.

We shall elaborate on the middle and upper classes’ seemingly ambivalent relationship to digital media in our concluding section, where we aim to contextualize our findings. For now, we may conclude that our second hypothesis – proposing that social agents’ place-exposing geomedia practices will vary with both volume of capital and capital composition – is partly supported by our analysis. Although capital composition seems less determinative for individuals’ readiness to check in at various sites of consumption, we do see clear distinctions pertaining to capital volume.

Since all but two modalities were explained by either capital volume or capital composition, at levels of statistical significance, we reject the ‘null’-version of our second hypothesis – suggesting that place-exposing geomedia practices would not be significantly different between actors across social space, due to people’s awareness of ‘context collapses’ on social media (Pitcan et al., Citation2018). Our results align with previous knowledge about cultural practices across social space and suggest that check-in practices are in fact socially classified, especially according to capital volume. A key observation is that different social groups’ patterns of exposing their place-visits align with previous research that has linked cultural preferences to various social positions (Flemmen et al., Citation2018; Prieur et al., Citation2008; Lindell, Citation2018). In other words, there is no support for the contention that classes deprived of cultural capital attempt to compensate their lack of symbolic mastery by exposing (rare) visits to cultural institutions to an online audience. Following the same social logic, the cultural middle and upper classes showcase their ‘culturally’ oriented movements through space. In this realm of online practices the force of habitus seems, thus, to outweigh dynamics of ‘passing’ and adjusting to middle-class values and expectations with ‘respectability politics’ (cf. Pitcan et al., Citation2018).

Discussion

Tagging oneself in a photo, ‘checking in’ at a hotel, a conference or an art exhibit, or sharing a photo of such places on various social media platforms – what we have referred to as place-exposing geomedia practices – are semi-public, overt, cultural practices with a double function. They contribute to both the construction of ‘selves’ and ‘places’. Since the advent of the smartphone and social media just above a decade ago, they have become key practices for identity formation and class demarcation among social groups. Yet, Bourdieusian cultural sociology has remained insensitive to the peculiarities of new media whereby cultural preferences and lifestyles become more overt and conspicuous. This study has shown that place-exposing practices on social media connect to the contemporary Swedish class structure, whereby individuals are positioned in terms of their volume and composition of various social resources. While certain discrepancies were identified between people with different capital portfolios, the main finding concerns the connection between geomedia practices and different volumes of capital. This study thus contributes to the broader field of cultural sociology, which has hitherto mainly focused on the ‘what’ and the ‘how’ of culture consumption (Koehrsen, Citation2019). In line with Koehrsen’s (Citation2019) call – we have added a focus upon the question of place, and ‘where?’. In times of geomediatization (Fast et al., 2018), where locative media are with (most of) us always, place-exposing practices emerge as a new instance in the reproduction of social relations, as well as a symbolic battlefield.

The main contribution of our study is that we can empirically verify how the socio-technological regime of geomedia (through which connective, representational and logistical affordances come together) extends deep-seated dynamics of socio-cultural reproduction and even reinforces the classificatory linkages between spatial appropriation and social identity work. Geomedia platforms constitute yet another toolset for cultural distinction and as such provide new means for cementing pre-existing class divisions, for example, through exposing prestigious cultural practices taking place at ‘nice’ venues and destinations. According to the same logic, this also means that geomedia practices play an important role in shaping the ‘value’ of different places, normalizing the understanding of what constitutes a ‘nice’ or ‘privileged’ place reserved for the ‘happy few’, and, conversely, stigmatizing certain places as less distinctive. As such, our study contributes a Bourdieusian angle to how ordinary media practices play into spatial (re)encoding processes related to for example gentrification (see also Tissot, Citation2018; Trinch & Snajdr, Citation2017; Wacquant, Citation2018; Jansson, Citation2005, Citation2019).

Such dynamics are likely to be further enhanced by the commercial logics of social media, where algorithmically constructed streams of information largely make up the environments people inhabit online (e.g., Couldry & Mejias, Citation2019; Striphas, Citation2015; Van Dijck, Citation2013). As such, the conspicuous tendencies we have identified here, and their classificatory implications, are automatically reinforced. Still, this does not rule out the possibility that geomedia, precisely through platformed sociality (Van Dijck, Citation2013) and the interactive construction of online ‘spatial selves’ (Schwartz & Halegoua, Citation2015), also constitutes a ‘learning machine’; a cultural forum that allows for a certain degree of symbolic experimentation among users and as such pull aspirational individuals into new symbolic contexts where previously unfamiliar places are put on display. To study such aspirational trajectories, and how they might contribute to the recoding of places such as in gentrification, we need to follow up the current study and include indicators of social mobility.

In light of the present study design, we must also be sensitive to the fact that different people expose their whereabout and cultural practices to different kinds of audiences (e.g., only to ‘friends’ on Facebook or to ‘everyone’). Indeed, we have not been able to discern the extent to which various people have different privacy settings on their social media accounts. As such, we call upon future research to detail how place-exposing practices might differ not only between social positions, but also in terms of the degree to which peoples’ social media accounts are configured to be either ‘overt’ or more ‘private’. Furthermore, since this study relies on a survey, we cannot know the extent to which self-reported behaviors correspond to actual practices. The correspondences between place-exposing practices and the social structure observed here might, in other words, capture a moral and symbolic economy rather than an economy of practices. We thus call for ethnographic research to bridge this gap.

Supplementary Material.docx

Download MS Word (23.5 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Johan Lindell

Johan Lindell is Associate Professor in Media and Communication studies at Uppsala University, Sweden. His research interests include the sociology of Pierre Bourdieu and media use and lifestyles, fields of media and cultural production and media systems. He has previously published his research in, for instance, New Media & Society, European Journal of Communication, Media, Culture & Society, Poetics and Communication Theory.

André Jansson

André Jansson is Professor of Media and Communication Studies and Director of the Geomedia Research Group at Karlstad University, Sweden. His most recent books are Transmedia Work: Privilege and Precariousness in Digital Modernity (with Karin Fast, Routlege, 2019) and Mediatization and Mobile Lives: A Critical Approach (Routledge, 2018). His upcoming book is entitled Rethinking Communication Geographies: Geomedia and the Human Condition (Edward Elgar).

Karin Fast

Karin Fast is Associate Professor at the Department of Geography, Media and Communication, Karlstad University, Sweden and research fellow at Media and Communication Studies at the University of Oslo. She is the author of Transmedia Work: Privilege and Precariousness in Digital Modernity (with André Jansson, 2019), and has also published her work in peer-review journals such as, for example, Communication Theory, Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, Media, Culture & Society, and Communication: The European Journal of Communication Research.

References

- Andrejevic, M. (2019). Automating surveillance. Surveillance & Society, 17(1/2), 7–13. https://doi.org/10.24908/ss.v17i1/2.12930

- Benson, M. (2016). Lifestyle migration: Expectations, aspirations and experiences. Routledge.

- Bourdieu, P. (1979 [1984]). Distinction: A social critique of the judgement of taste. Routledge.

- Bourdieu, P. (1989). Social space and symbolic power. Sociological Theory, 7(1), 14–25. https://doi.org/10.2307/202060

- Bourdieu, P. (1990). The logic of practice. Stanford University Press.

- Bourdieu, P. (1996). On the family as a realized category. Theory, Culture & Society, 13(3), 19–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/026327696013003002

- Bourdieu, P. (2000). Pascalian meditations. Stanford University Press.

- Bourdieu, P., & Wacquant, L. J. (1992). An invitation to reflexive sociology. University of Chicago press.

- Boy, J. D., & Uitermark, J. (2017). Reassembling the city through Instagram. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 42(4), 612–624. https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12185

- boyd, d. (2011). Social network sites as networked publics: Affordances, dynamics, and implica- tions. In Z. Papacharissi (Ed.), A networked self: Identity, community, and culture on social network sites (pp. 39–58). Routledge.

- Broady, D. (2001). What is cultural capital? Comments on Lennart Rosenlund’s social structures and change. Sosiologisk arbok (2), 45–60.

- Chan, T. W. (2019). Understanding cultural omnivores: Social and political attitudes. The British Journal of Sociology, 70(3), 784–806. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-4446.12613

- Correia, A., & Kozak, M. (2012). Exploring prestige and status on domestic destinations: The case of Algarve. Annals of Tourism Research, 39(4), 1951–1967. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2012.06.005

- Couldry, N., & Mejias, U. A. (2019). Data colonialism: Rethinking big data’s relation to the contemporary subject. Television & New Media, 20(4), 336–349. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527476418796632

- Daenekindt, S., & Roose, H. (2017). Ways of preferring: Distinction through the ‘what’ and the ‘how’ of cultural consumption. Journal of Consumer Culture, 17(1), 25–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469540514553715

- Davis, J. L., & Jurgenson, N. (2014). Context collapse: Theorizing context collusions and collisions. Information, Communication & Society, 17(4), 476–485. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2014.888458

- Dinhopl, A., & Gretzel, U. (2016). Selfie-taking as touristic looking. Annals of Tourism Research, 57, 126–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2015.12.015

- Durham Peters, J. (2008). Strange sympathies: Horizons of German and American media theory. In F. Kelleter & D. Stein (Eds.), American studies as media studies (pp. 3–23). Universitätsverlag.

- Duval, J. (2018). Correspondence analysis and Bourdieu’s approach to statistics. In T. Medvetz & J. J. Sallaz (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Pierre Bourdieu (pp. 512–527). Oxford University Press.

- Fast, K., Jansson, A., Lindell, J., Ryan Bengtsson, L., & Tesfahuney, M. (2018). Introduction to geomedia studies. In K. Fast, A. Jansson, J. Lindell, L. Ryan Bengtsson, & M. Tesfahuney (Eds.), Geomedia studies: Spaces and mobilities in mediatized worlds (pp. 1–17). Routledge.

- Fast, K., Lindell, J., & André, J. (2021). Disconnection as distinction: A bourdieusian approach to where people withdraw from digital media. In A. Jansson & P. C. Adams (Eds.), Disentangling: The geographies of digital disconnection (pp. 61–90). Oxford University Press.

- Fast, K., Ljungberg, E., & Braunerhielm, L. (2019). On the social construction of geomedia technologies. Communication and the Public, 4(2), 89–99.

- Featherstone, M. (1991). Consumer culture and postmodernism. Sage.

- Flemmen, M., Jarness, V., & Rosenlund, L. (2018). Social space and cultural class divisions: The forms of capital and contemporary lifestyle differentiation. The British Journal of Sociology, 69(1), 124–153. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-4446.12295

- Frith, J., & Kalin, J. (2016). Here, I used to be: Mobile media and practices of place-based digital memory. Space and Culture, 19(1), 43–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/1206331215595730

- Gayo, M., Joye, D., & Lemel, Y. (2018). Testing the Universalism of Bourdieu’s Homology: Structuring Patterns of Lifestyle across 26 Countries (No. 2018-04).

- Goffman, E. (1959). The presentation of self in everyday life. Anchor Books.

- Goriunova, O. (2019). The digital subject: People as data as persons. Theory, Culture & Society, 10.2632/76419840409

- Hargittai, E., & Litt, E. (2013). Facebook fired? The role of internet skill in people’s job-related privacy practices online. IEEE Security & Privacy, 11(3), 38–45. https://doi.org/10.1109/MSP.2013.64

- Hjellbrekke, J. (2019). Multiple correspondence analysis for the social sciences. Routledge.

- Hjellbrekke, J., Jarness, V., & Korsnes, O. (2015). Cultural distinctions in an “egalitarian” society, s. In P. Coulangeon, & J. Duval (Eds.), The Routledge Companion to Bourdieu’s distinction (pp. 187–206). Routledge.

- Hovden, J. F., & Moe, H. (2017). A sociocultural approach to study public connection across and beyond media: The example of Norway. Convergence, 23(4), 391–408. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856517700381

- Hutchby, I. (2001). Technologies, texts and affordances. Sociology, 35(2), 441–456. https://doi.org/10.1177/S0038038501000219

- Jansson, A. (2005). Re-encoding the spectacle: Urban fatefulness and mediated stigmatisation in the 'City of Tomorrow'. Urban Studies, 42(10), 1671–1691.

- Jansson, A. (2019). The mutual shaping of geomedia and gentrification: The case of alternative tourism apps. Communication and the Public, 4(2), 166–181.

- Jansson, A. (forthcoming). Rethinking communication geographies: Geomedia and the human condition. Edward Elgar.

- Jarness, V. (2015). Modes of consumption: From ‘what’ to ‘how’ in cultural stratification research. Poetics, 53(December), 65–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poetic.2015.08.002

- Jenkins, H. (2004). The cultural logic of media convergence. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 7(1), 33–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367877904040603

- Koehrsen, J. (2019). From the ‘what ‘and ‘how ‘to the ‘where’: Class distinction as a matter of place. Cultural Sociology, 13(1), 76–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/1749975518819669

- Lefebvre, H. (1974). /1991). The production of space. Blackwell.

- Lindell, J. (2018). Distinction recapped: Digital news repertoires in the class structure. New Media & Society, 20(8), 3029–3049. http://doi.org/10.1177/1461444817739622

- Lindell, J., & Hovden, J. F. (2018). Distinctions in the media welfare state: Audience fragmentation in post-egalitarian Sweden. Media, Culture & Society, 40(5), 639–655. http://doi.org/10.1177/0163443717746230

- Lizardo, O., & Skiles, S. (2015). After omnivorousness, is Bourdieu still relevant?. In L. Hanquinet & M. Savage (Eds.), Handbook of the sociology of art and culture (pp. 90–103). Routledge.

- Lo, I. S., & McKercher, B. (2015). Ideal image in process: Online tourist photography and impression management. Annals of Tourism Research, 52, 104–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2015.02.019

- Marom, N. (2014). Relating a city’s history and geography with Bourdieu: One hundred years of spatial distinction in Tel Aviv. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 38(4), 1344–1362. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12027

- McQuire, S. (2016). Geomedia: Networked cities and the future of public space. Polity Press.

- Meyrowitz, J. (1986). No sense of place: The impact of electronic media on social behavior. Oxford University Press.

- Munar, A. M., & Jacobsen, J. K. S. (2014). Motivations for sharing tourism experiences through social media. Tourism Management, 43, 46–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2014.01.012

- Özkul, D., & Humphreys, L. (2015). Record and remember: Memory and meaning-making practices through mobile media. Mobile Media & Communication, 3(3), 351–365. https://doi.org/10.1177/2050157914565846

- Peters, J. D. (2015). The marvelous clouds: Toward a philosophy of elemental media. University of Chicago Press.

- Peters, J., van Eijck, K., & Michael, J. (2018). Secretly serious? Maintaining and crossing cultural boundaries in the karaoke bar through ironic consumption. Cultural Sociology, 12(1), 58–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/1749975517700775

- Pitcan, M., Marwick, A. E., & boyd, D. (2018). Performing a vanilla self: Respectability politics, social class, and the digital world. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 23(3), 163–179. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcmc/zmy008

- Polson, E. (2016). Negotiating independent mobility: Single female expats in Bangalore. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 19(5), 450–464. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367549416631548

- Prieur, A., Rosenlund, L., & Skjott-Larsen, J. (2008). Cultural capital today: A case study from Denmark. Poetics, 36(1), 45–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poetic.2008.02.008

- Rosenlund, L. (2015). Working with distinction: Scandinavian experiences. In P. Coulangeon & J. Duval (Eds.), The Routledge companion to Bourdieu’s distinction (pp. 157–186). Routledge.

- Rosenlund, L. (2019). The persistence of inequalities in an era of rapid social change: Comparisons in time of social spaces in Norway. Poetics, 74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poetic.2018.09.004

- Rossiter, N. (2015). Locative media as logistical media: Situating infrastructure and the governance of labor in supply-chain capitalism. In R. Wilken & G. Goggin (Eds.), Locative media (pp. 208–223). Routledge.

- Savage, M. (2010). The politics of elective belonging. Housing, Theory and Society, 115–161. https://doi.org/10.1080/14036090903434975

- Savage, M., & Silva, E. B. (2013). Field analysis in cultural sociology. Cultural Sociology, 7(2), 111–126. https://doi.org/10.1177/1749975512473992

- Schwartz, R., & Halegoua, G. R. (2015). The spatial self: Location-based identity performance on social media. New Media & Society, 17(10), 1643–1660. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444814531364

- Shani, G. (2019). How place shapes taste: The local formation of middle-class residential preferences in two Israeli cities. Journal of Consumer Culture, 10.1469/540519882486

- Striphas, T. (2015). Algorithmic culture. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 18(4–5), 395–412. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367549415577392

- Thielmann, T. (2010). Locative media and mediated localities: An introduction to media geography. Aether: The Journal of Media Geography, V, 1–17.

- Tissot, S. (2018). Categorizing neighborhoods: The invention of ‘sensitive areas’ in France and ‘historic districts’ in the United States. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 42(1), 150–158. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12530

- Trinch, S., & Snajdr, E. (2017). What the signs say: Gentrification and the disappearance of capitalism without distinction in Brooklyn. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 21(1), 64–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/josl.12212

- Van Dijck, J. (2013). The culture of connectivity: A critical history of social media. Oxford University Press.

- Van Dijck, J., & Poell, T. (2013). Understanding social media logic. Media and Communication, 1(1), 2–14. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v1i1.70

- Veblen, T. (1899 [2008]). The theory of the leisure class. Project Gutenberg. https://gutenberg.org/files/833/833-h/833-h.htm

- Verhoeff, N. (2008). Screens of navigation: From taking a ride to making the ride. Journal of Entertainment Media, 12.

- Wacquant, L. (2007). Urban outcasts. Polity Press.

- Wacquant, L. (2018). Bourdieu comes to town: Pertinence, principles, applications. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 42(1), 90–105. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12535

- Wilken, R., & Goggin, G. (2015). Locative media – definitions, histories, theories. In R. Wilken & G. Goggin (Eds.), Locative media (pp. 1–21). Routledge.

- Wilken, R., & Humphreys, L. (2019). Constructing the check-in: Reflections on photo-taking among foursquare users. Communication and the Public, 4(2), 100–117. https://doi.org/10.1177/2057047319853328

- Zukin, S., Lindeman, S., & Hurson, L. (2015). The omnivore’s neighborhood? Online restaurant reviews, race, and gentrification. Journal of Consumer Culture. https://doi.org/10.1469/540515611203

Appendix

Table A1. Active variables used to create the Swedish social space.

Table A2. Benzécri-adjusted eigenvalues of top 10 dimension among the active variables.

Table A3. Contributions and squared cosines of active categories, dimensions 1 and 2.

Table A4. V-test for modalities in supplementary variables on the two main dimensions.