ABSTRACT

A major development in the music industries in recent years has been the rise of ‘unsigned’ or ‘self-releasing’ musicians (sometimes problematically called ‘DIY musicians’ or ‘independent musicians’) who upload music directly to music streaming platforms (MSPs). This article examines the distinctive way in which Chinese MSPs have sought to incorporate such self-releasing musicians into their platform eco-systems and what it tells us about the ways in which digital platforms commodify cultural expression. We show that a remarkable new system has developed in China, based on evolving dynamics of platform power and state-business relations, and very high levels of concentration and integration. Yet the work of independent, self-releasing musicians is playing a much bigger part in the Chinese system than in other parts of the world, allowing them to reach audiences in ways that were not previously possible. Drawing on critical studies of digital platforms and of the historical development of the music industries, we show that this apparent democratisation also represents an incorporation and commodification of activity that would often previously have taken place beyond the music industries, in ways that place constraints on the cultural autonomy of self-releasing musicians.

1. Introduction

There has been increasing interest, in recent social science and humanities research, in how more and more domains of social and cultural life have come under the aegis of digital platforms – a process often known as ‘platformisation’ (Van Dijck et al., Citation2018). Music potentially serves as a fascinating example of the platformisation of culture, because in recent years, a new system of musical distribution and consumption centred on music streaming platforms (MSPs) has arisen. Following a period of crisis for the music industries from 2000 to 2015, this new system has enabled a recovery of the recorded music and publishing industries by providing new flows of revenue from subscriptions and advertising (Sun, Citation2018). More than 62% of global revenue from recorded music now comes from music streaming (IFPI, Citation2021), and in many countries, MSPs such as Spotify, Apple, Amazon, YouTube and Soundcloud offer the main way in which consumers access recorded music.

While some researchers have begun to consider the platformisation of culture (Nieborg & Poell, Citation2018) and more specifically of music (Prey, Citation2020), one striking aspect of this system has not been given any sustained attention. A growing number of independent, unsigned or self-releasing musicians can now make their music easily available via distributors such as Tunecore and CD Baby, or ‘producer-oriented’ platforms such as Soundcloud and Bandcamp (Hesmondhalgh et al., Citation2019). As a result, an increasing amount of music is now made public by musicians that have not signed contracts with record or music publishing companies, whether the big multinational ‘majors’ (Universal, Sony and Warner) or small and medium-sized companies. While the vast majority of time spent on musical consumption, and therefore of recorded music income, is generated by content licensed to MSPs by record and music publishing companies, a great deal of the content on these platforms is self-released music. The amount of such self-released music that is available is growing fast across the world, as we shall see below – and so is the economic importance of this sector (Mulligan & Jopling, Citation2020). While some analysts have discussed the working conditions faced by such musicians (e.g., Haynes & Marshall, Citation2018), the implications of the incorporation of this vast musical ‘surplus’ into the platform system have not been analysed, either by researchers of the music industries, or by those analysing digital platforms. This incorporation raises potentially illuminating issues about the new and distinctive ways in which digital platforms are involved in the commodification of culture. In this article, we suggest that this incorporation can be understood as a process by which musical creativity that previously existed outside the system of recorded music is, under platformisation, brought within that system, with new implications for understanding the power of digital platforms.

The case of China highlights these issues in a particularly stark way, because of the remarkable degree of concentration and integration in Chinese music markets. In China, currently the world’s seventh largest market for music (IFPI, Citation2021) but set to become much bigger, a unique platformised system has developed out of China’s distinctive music business and culture. There is remarkably little serious critical cultural and media research published in English on the Chinese music industries, as we show in our literature review below. Our article, therefore, makes a significant contribution by examining the distinctive features of the Chinese music industries in general. However, our main purpose is to analyse the distinctive ways in which Chinese MSPs have incorporated self-releasing musicians into the Chinese platform eco-system, and what this says about dynamics of power, control and commodification in relation to music and expressive culture. To achieve this aim, we draw on theories and perspectives from critical media, communication and internet studies, platform studies, and in particular those approaches known as political economy and cultural studies, concerned as they are with dynamics of power and inequality in relation to culture, the first emphasising economic, legal and regulatory issues, the second matters of culture, knowledge and identity.

The next section places this analytical framework in the context of existing research, emphasising the historical importance of ‘reservoirs’ or ‘talent pools’ of musical labour, many of them operating in ‘proto-markets’ (Toynbee, Citation2000), which exist alongside, and feed, a centralised, more fully commodified core. Section 3 provides essential context by explaining the rise of self-releasing musicians across the world, and in the Chinese music industries specifically. Section 4 then examines the distinctive ways in which the two main Chinese MSPs have incorporated self-releasing musicians, and compares the political-economic processes and cultural factors involved.

2. Platformisation, the music industries and musical labour

Drawing on research in software studies, business studies, and political economy, Poell et al. (Citation2019, p. 1) have defined platformisation as ‘the penetration of the infrastructures, economic processes, and governmental frameworks of platforms in different economic sectors and spheres of life’, and drawing on cultural studies, as ‘the reorganisation of cultural practices and imaginations around platforms’. We go beyond existing research on the platformisation of cultural production (Nieborg & Poell, Citation2018) on the music industries and MSPs (Prey, Citation2020), and on creative and cultural labour (e.g Banks et al., Citation2013) by placing platformisation in long-term historical context, and in particular by analysing what commodification enabled by cultural platforms might mean for the creative autonomy of musicians.

In order to understand the significance of how platformisation is affecting musical labour, we need to consider the system of musical labour that prevailed prior to the rise of the new musical eco-system centred on streaming platforms. Musical labour, in much of the world, has long involved workers providing their services to numerous buyers rather than a single firm. This is also true of many workers in other major cultural industries such as radio, television, journalism and film, but arguably it is even more the case in music. As Jason Toynbee (Citation2000) showed in a ground-breaking analysis of musicians, musical labour combines dynamics of precariousness and independence or autonomy.Footnote1 In popular music contexts where little formal training or education was required, access to the means of making and distributing music increased significantly in the twentieth century, as costs of instrumentation and recording declined, and there was an expansion of leisure time and income, and an ensuing proliferation of spaces where music was welcome.

Toynbee differentiated two distinct spheres that emerged from these conditions. The first consisted of local musical scenes and networks, in which (often young) musicians honed their skills and developed new styles in ‘proto-markets’, commodified to relatively limited degrees, where commercial impulses were often constrained by factors such as love of music, romantic ideologies, and the use of music as an expression of solidarity, e.g., in rock, rap, jazz, reggae and myriad other genres (Toynbee, Citation2000, pp. 1–33). The second sphere comprised highly centralised systems of dissemination, in the form of recording and publishing companies operating at a national and international level, and few-to-many media (radio, television, cinema, print). The first sphere came to function as a vast ‘reservoir’ of potential labour for the second sphere, as musicians sought fame and fortune in the latter, in spite of the fact that only very few could actually achieve success (Miège, Citation1989). This ‘over-supply of human and musical resources’ (Toynbee, Citation2000, p. 27) was helpful for capitalist businesses, but they faced the challenge of selecting and recruiting musicians and styles from the abundant musical activity beyond their sphere, not knowing which would achieve success in constantly shifting market conditions.

In later work, Matt Stahl (Citation2013) provided a detailed analysis of how contradictions between autonomy and independence on the one hand, and control and precariousness on the other, operated in various historical circumstances in the USA. Building on Toynbee’s combination of political economy and cultural studies analysis, Stahl drew on critical legal studies and business history to show how, when musicians do subject themselves to the control of firms and institutions in the second sphere, in return for potential recognition and financial reward, this usually happens under the aegis of intellectual property and contract law regimes, in ways that favour capitalist businesses. Central to this, according to Stahl, are the recording and publishing contracts that determine royalty rates and much else, shaped under asymmetrical conditions where rights-holders have much greater knowledge than contracting musicians, and sustained by complex national copyright laws, framed according to international copyright treaties and agreements. Stahl thereby provided a detailed historical account of how Toynbee’s ‘institutional autonomy’ is structured into the music industries, in ways that are highly problematic for musical labour.

This critical historical sociology of musical labour has not been adequately updated for the digital age. In public debate about the impacts of digitalisation of culture, during the period in which digitalisation seemed to be eroding the power of the ‘legacy’ recording and publishing industries, through its threat to the artificial scarcity that sustained underlying copyright regimes, it seemed to be assumed by some digital optimists that a future digital system, just over the horizon, would democratise culture by making it possible for ‘a long tail’ of smaller producers to exist alongside the big hits and superstars that dominated sales and income (Anderson, Citation2014). In an era when much commentary was focused on ‘user-generated content’, concerns about digital labour during this period were principally focused for a long time on the ‘free labour’ or ‘unpaid labour’ of users or ‘prosumers’ (Hesmondhalgh, Citation2016; see also Anderson, Citation2014) rather than the cultural workers who undertook actual production and distribution. As MSPs began to stabilise music industry revenues, however, a new set of concerns emerged about the paltry pay-outs to musicians being made by these newly emergent business models (Dredge, Citation2013). However, these concerns were expressed mostly in journalism (e.g., Pelly, Citation2018) and most critical research on MSPs was paying (often valuable) attention to various other issues, such as how MSPs use data to achieve personalisation, which not only ‘reflects social divisions (between high-value and low-value listeners, for example) but reinforces and even produces new divisions’ (Prey, Citation2016, p. 42; see also Drott, Citation2018), and how MSP processes of recommendation and curation, notably through playlists, might be reshaping musical experience and subjectivity (Eriksson & Johansson, Citation2017). Some analysts offered significant research on how musicians must adapt to, or in some cases push back against, requirements of platforms in the new digital music economy, including social media platforms, illuminating how the longstanding requirement for musicians to act as self-sufficient entrepreneurs was being remade and reinforced in the contemporary world (Baym, Citation2018; Haynes & Marshall, Citation2018). Research that focused on widespread concerns about musician earnings from MSPs nuanced polemical attacks on those platforms by pointing to the key role of rights-holders, who retained the lion’s share of payments from the new MSPs (Hesmondhalgh, Citation2020); Marshall, Citation2015; Sinnreich, Citation2016; Towse, Citation2020) in ways familiar from previous regimes. But none of these recent studies of musical labour have paid systematic historicised attention to the structural political-economic and cultural issues raised by Toynbee and Stahl, concerning the dialectic of control and autonomy in the system based on the co-existence or a ‘reservoir’ of musical labour (Toynbee’s first sphere) with highly centralised and commodified organisations and technologies (Toynbee’s second sphere). Nor have we found critical research that examines the political-economic and cultural implications of the increasing inclusion, or perhaps better incorporation, of independent, self-releasing cultural workers into the music platform system, at least none that places such an examination in the longer-term historical context we have offered above. The same is true of an important parallel literature that deals with the cultural work of creators on video platforms such as YouTube (Caplan & Gillespie, Citation2020).

As for the Chinese context that we focus on here, there has been some English-language research on the music industries in China, but none of it comes close to addressing these dynamics of incorporation and commodification in a historical context. Some business analysis (e.g., Tang & Lyons, Citation2016) points to dynamics of integration, such as Tencent’s important purchase of rights-holder China Music Corporation (which Tang and Lyons see as horizontal integration, but can just as easily be seen as vertical, in that it brings together MSP distributors with rights-holders). Shen et al. (Citation2019) provide the most developed English-language account, tracing the evolution of China’s online music ecology back to the tightening of copyright law and enforcement in 2011–2014, leading rapidly to the domination of the BAT (Baidu, Alibaba, Tencent) internet giants, reinforced by the growth of mobile technologies. In the absence of powerful incumbents such as major record companies, and building on a loose though tightening intellectual property regime that allowed experimentation and innovation, such as integration of online karaoke into MSPs, the internet giants developed distinctive strategies, including the ‘musician support projects’ that we analyse below. However, Shen et al.’s science and technology studies approach is interested primarily in the conditions that allow ‘innovation’, rather than the implications for musical labour and cultural autonomy. Our approach here is informed by cultural studies and sociological analysis focused on the implications of these political-economic developments for musical sociality and community. Our approach is not to examine the subjectivity of musical workers in detail, though that is certainly a worthwhile aim. Rather, in the line with the platform studies of van Dijck, Poell and their colleagues, we examine platform mechanisms to examine the affordances they offer and their impacts on musical workers and cultural autonomy. We examine platform interfaces, functions and practices, and draw on reports from music industry and technology online media, supplemented by interviews with product managers and algorithm engineers conducted in China in 2018 and 2020, which were transcribed and analysed.

3. Self-releasing musicians in the platformised music industries

The platformisation of music has brought about a new set of relationships between the ‘reservoir’ or ‘talent pool’ of musicians, and the commercial core where many of them seek success. In Europe and North America (and much of Latin America), in order to make their music available across the many MSPs available, and to manage their often rather meagre revenues, self-releasing musicians make use of a set of companies that did not really exist until the last twenty years, which tend to call themselves distributors or label service companies (Cooke, Citation2018, p. 131). These companies range from companies such as Tunecore that make their services available to pretty much anyone who wishes to use them, to companies such as Ditto, which like record companies offer a range of distribution and marketing services but unlike those companies allow musicians to retain ownership of their copyrights (Ingham, Citation2019). Musicians working with the latter companies are, therefore, ‘unsigned’ or ‘self-releasing’ but they are not amateurs: they might be ambitious musicians, keen to establish a large audience and build a career, or established musicians who no longer wish to work with major or large independent record companies. These new distributors or label service companies track and collect publishing revenues on behalf of the songwriters and composers who use them. Meanwhile, self-releasing musicians at different scales, from small to large, gain income from other sources besides recording, from live music and the sale of merchandise, and other jobs such as teaching.

As a result of this new system, unsigned or self-releasing musicians have become increasingly important, in business and in musical terms, across much of the world. Mulligan and Jopling (Citation2020) estimate that what they call the ‘artists direct’ sector amounted to around 873 million US dollars in 2019 (in recording revenues alone – songwriting revenues are extra). This constitutes a small share (4.1%) of global recorded music revenue, but the growth rate is very striking and some consider this sector to be ‘the most exciting and fastest-growing sector to spring out of the music industry’s streaming revolution’ (Ingham, Citation2019). China ‘is becoming a particularly interesting hotspot’ for this growing self-releasing or DIY market (Ingham, Citation2020).

There is a confusing array of terminology in this domain and we need to pause to justify our use of the term ‘self-releasing’ artists. Often the term ‘independent’ artists is used to refer to any musician, on no matter what scale, who seeks to bypass rights-holders. The term ‘artists direct’ seems to be applied to those musicians who do not even use marketing services. In any case, the term ‘independent’ can easily be confused in this context with musicians who are signed to independent record companies. Others, such as Ingham (Citation2019) use the term ‘DIY artists’, though this risks confusion with a particular musical culture named DIY, which places emphasis ‘on forming and maintaining spaces for production and distribution which purportedly exist outside of, and are positioned as oppositional to, the popular music industries’ (Jones, Citation2019, p. 2), when in fact many musicians at the first and second levels delineated above have no such oppositional goals. Faced with this confusing morass of terms, we prefer ‘self-releasing’, which is more specific than ‘independent’, more inclusive than ‘artists direct’, and less ideologically loaded than ‘DIY’.

The system that has emerged in China is completely different from this system based on self-releasing musicians bypassing rights-holders to access MSPs via new digital distributors and label service companies. There is not only a much greater role of the state in the music industries in China but also the multinational ‘major’ corporations have never dominated market share in China to anything like the same degree as elsewhere. While the three majors (Universal, Sony and Warner) have market shares of 70–80% in many western countries, in China, they rarely achieve more than 30% of market share in recording and publishing (An, Citation2016). Crucially, a situation has arisen in which Chinese MSPs can be rights owners as well as distributors. The various MSPs operated by just two major corporations, Tencent and NetEase, dominate the platform space to an even greater degree than Spotify and Apple Music in the west, especially following the recent closure of Xiami Music (run by Alibaba) in 2021.

Even more strikingly, Tencent (though not NetEase) integrates platform control with rights ownership – by contrast with the west, where Spotify and Apple own no significant music rights, and the major rights-holding companies hold only very small stakes in platform corporations. This is because the early efforts of the major rights-holding companies to develop their own music platforms failed (Mulligan, Citation2015). Apple stepped into the breach with its iTunes system, but it became clear that the subscription model of MSPs offered a much more stable basis for musical capitalism, and Swedish company Spotify was chosen by investors and digital partners (such as Facebook) to lead the way. Internet giants Apple, Amazon and Google eventually entered into the emerging music platform market via purchases of tech unicorns, but this could only happen once rights-holding majors and larger independents, now finally seeing a profitable legal alternative to ‘piracy’, had agreed to license their music to MSPs, though on terms very favourable to themselves.

In China, by contrast, the Chinese state permitted rights-owning Chinese companies to develop their own MSPs. Up until around 2012–2014, a huge mass of unlicensed music co-existed with licensed music on the still-nascent Chinese MSPs. In the clampdown on copyright infringement mentioned earlier, MSPs were required to take down all unlicensed music on their sites, and this favoured those bigger companies that could pay for licensed music, especially Tencent Music Entertainment (TME) which as we saw above had purchased a majority stake in a vast rights-holding company, China Music Corporation (CMC), in 2016. TME is now the largest distributor and music rights owner in China, with an estimated 90% of copyright market share of Chinese music copyrights, based on its purchase of the huge copyright assets of CMC (Xuan, Citation2020).

However, in 2018 came a crucial development that was to lead to a greater degree of incorporation of unsigned, self-releasing musicians into the platform system than has been the case in North America and Europe. In that year, in order to limit TME’s market dominance and facilitate greater platform competition, the NCAC, the National Copyright Authority of China, introduced a new regulation. Previously, Chinese MSPs competed on the basis of the exclusive content that each offered – i.e., content available only on their platforms. The new regulation ‘suggested’ that Chinese MSPs should sublicense at least 99% of their exclusive content to other platforms.Footnote2 This had two consequences. First, Chinese MSPs came to have mostly the same music as each other – more than 99%. In this respect (though only in this respect), they became more like western platforms, which broadly have the same repertoire as each other, but compete on the basis of their interfaces, playlists, recommendation algorithms, etc. Second, the 1% of content still permitted to be exclusive became the main way in which platforms competed. This often consisted of the work of just a few superstars, but began to generate a huge amount of streams – around 50% of the total (Pan, Citation2018).

Chinese MSPs then began to compete to expand repertoire by incorporating self-releasing musicians. They did so first, from 2014 onwards, by introducing ‘musician support projects’ (such as Xiami’s ‘Light Seeking Project’) that aimed to draw emerging, unsigned musicians into the emerging music platform system. The aim was to sign artists to exclusive deals and develop them as stars. However, around the same time, aiming at expanding total catalogue, and therefore the 1% exclusive content they were permitted, Chinese music platforms also launched self-releasing schemes to attract musicians of all kinds to upload their own content, in a way somewhat similar to how western platforms such as YouTube and Soundcloud permit anyone with digital access to upload their music. It is this moment that, we claim, represents a new phase, whereby the creativity of musicians previously outside the business models of the music industries started to become incorporated within them.

These self-releasing schemes have grown steadily over the years. On NetEase’s ‘NetEase Cloud Musician’ self-releasing scheme alone, the number of artists had grown from 20,000 in 2016 to 200,000 in 2020 (Ingham, Citation2020). In the process, the relationship between musician support projects and self-releasing schemes has evolved. Before 2016 musician support projects (e.g., TME’s Mass Innovation and Music Project and NCM’s Stone Project I) mainly served as talent-hunting campaigns so that platforms could select some musicians for development as stars. After 2016, while some projects (such as TME’s Force Project) continued to provide such ‘artist-based’ talent support, new projects became subservient to self-release schemes which catered to musicians and were mainly ‘song-based’ publishing and distribution services (interview, October 23, 2020). Both TME and NCM upgraded their self-release schemes (Tencent Musician and NCM Musician, respectively) by offering self-releasing artists services such as publishing administration, data management, recommendation and tipping.Footnote3 To facilitate these schemes, the platforms launched related projects offering incentives such as promotional services and financing – such as NCM’s Ladder Project (2018) and TME’s Galaxy Project (2020) – in order to expand the total catalogue and therefore the 1% exclusive content. Thus, unlike the situation in the west, where digital distributors such as CD Baby and TuneCore operate independently from MSPs, providing various services to musicians, digital distribution for self-releasing musicians in China is thoroughly integrated within the Chinese music platform eco-system.

4. Chinese self-release schemes and platform mechanisms

We now analyse how self-release schemes have become strategic and fundamental components in the running of MSPs, and how they affect the cultural autonomy of musicians, in the new conditions of commodification outlined above. The schemes’ declared goal is to incubate ‘original music’. Often in China the term ‘original’ (原创) is interchangeably used with ‘indie’ (独立) and it is vital here to clarify, for Chinese and ‘western’ readers some real problems of terminology and translation, given the fundamental connections of notions of independence with cultural autonomy (Klein, Citation2020). ‘Indie’ in the contemporary Chinese music context has less to do with the anti-commercial ethos and alternative networks associated with independent music culture in North America and Europe, and more with an ideology of cultural entrepreneurialism that emphasises the need for musicians to forge their own careers (Bennett, Citation2018). While in Japan and Korea, indie musicians have tended to adopt cultural-political positions at odds with prevailing neoliberal discourses (Jian, Citation2018, p. 5), such politics are not so much to be found in Chinese indie music culture which has lost the underground anti-hegemonic ethos of the late 1990s (Qu, Citation2017). Instead there has been a shift to a highly depoliticised notion of originality (De Kloet, Citation2010) and ‘grassroots entrepreneurship’ (Keane, Citation2007, p. 34). ‘Indie’ or ‘original’ music on MSPs is very much a socio-economic concept, often validated by the ability of musicians to develop entrepreneurial careers, manage copyrights and to develop brand identities ‘that generate multiple revenue streams’ (Haynes & Marshall, Citation2018, p. 463). Our analysis below therefore explores the degree to which self-releasing schemes are tied to problematic dynamics of commodification, and how this shapes ‘intrinsic’ notions of the value of music, i.e., notions of value that do not depend upon ‘external validators like the market’ (Haynes & Marshall, Citation2018, p. 478).

Van Dijck, Poell and de Waal have differentiated three key interacting ‘mechanisms’ by which digital platforms operate: datafication – the ability of platforms to turn into data aspects of the world not previously quantified; selection – the way that they steer user interaction though selection or curation of topics, actors, objects, services and so on; and commodification – the transformation of various elements into services that can be bought and sold (Van Dijck et al., Citation2018, pp. 31–48). Following this analytic framework, we compare the self-releasing schemes of the two leading Chinese MSPs, showing how their datafication practices are conditioned by the specific ways in which these MSPs seek to commodify the creativity of Chinese musicians, and how this in turn influences selection and curation strategies, diminishing cultural autonomy in the process.

4.1. TME’s self-releasing scheme: Tencent Musician

TME’s four music platforms are QQ Music (online listening), WeSing (social karaoke), Kugou Music (short video content) and Kuwo Music (long audio content), forming a single eco-system. They have over 800 million monthly active users, and own the rights and licenses to over 30 million songs (Li, Citation2019). TME’s self-release schemes, previously available as a service under each platform, were integrated in 2020 as Tencent Musician on a separate platform, standardising enrolment of music(-ians) and centralising the production and distribution of musical content. This centralisation involves a deepening affiliation with Tencent’s overall platform strategies, and with state control.

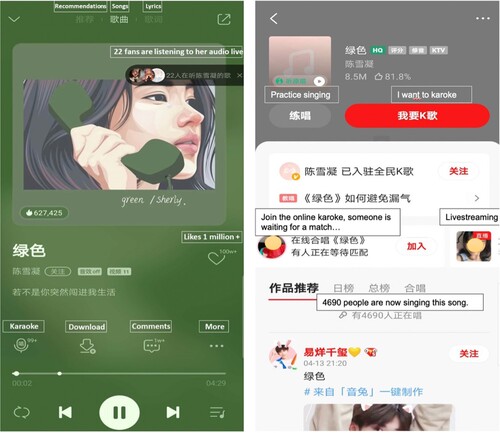

We begin with datafication mechanisms. Large quantities of data are generated regarding demographics, music metadata and user interactions. This data is then used to test and calculate the amount of exposure each song might get, based on the goal of producing a ‘pan-entertainment’ experience across the four platforms. shows that, on the page for the song ‘Green’ on QQ Music, when a user clicks the ‘22 fans are listening to her audio live’ tab, the user will then be directed to another user’s live chat room where someone might be singing live or chatting with other users, with ‘Green’ playing in the background. Or, by clicking the ‘karaoke’ tab on the ‘Green’ page, the user is directed to the WeSing page of ‘Green’ () where they can karaoke alone or with others and watch other users livestreaming ‘Green’ in real time. Similar inter-platform circulation dynamics also pertain on Kugou and Kuwo. Though NCM has similar entertainment features, what is distinctive on TME’s platform are the real-time analytics (Prey, Citation2018) of users’ music-related entertainment behaviour, which drive and optimise personalised advertising for TME (Jiang, Citation2015). Also, as real-time analytics help ‘infer what a given user’s situation might be, at a given moment in time’ (Drott, Citation2018, p. 253), TME’s real-time circulation can be used to predict the mood, context and content of music usage among individuals and collectives.

Figure 1. (Left) shows the page for the song ‘Green’ on QQ music. By clicking the ‘karaoke’ tab on this page, users are directed to the karaoke page (right). 6 September 2020.

Datafication is deeply connected to commodification (Van Dijck et al., Citation2018). First of all, TME’s business model includes two sets of revenues: 30% comes from online music services (subscription, download, ads and sub-license) and 70% from social entertainment services (‘tipping’ – donations by users – in livestreaming and karaoke) (Dong, Citation2021; Xuan, Citation2020). Chinese streaming platforms do not generate significant subscription income (and even western services run at a loss). This has pushed TME to emphasise entertainment functions such as livestreaming, karaoke and short video in order to generate tipping and ‘gifts’.

This pan-entertainment commodification model affects musical autonomy. Listeners are easily distracted by such pervasive and interactive functions. Each song no longer retains its boundary as an independent work but instead functions to spark connections to other activities, thus affecting the textual and sonic autonomy of songs. Moreover, cultural autonomy, involving tensions with commercialism and state control (Klein, Citation2020), is hampered when Tencent Musician systematically pursues cross-sector and governmental collaborations to enlarge its already vast catalogue and to grow its influence. Tencent Musician has launched a series of themed song-writing competition activities, involving collaboration with the state and governmental organisations. For example, in 2018 Tencent launched a songwriting competition in collaboration with the Palace Museum, entitled ‘Ancient Paintings Can Sing’, with strong themes of patriotism and nationalism. Self-release musicians are increasingly likely to feel compelled towards such promotional activities. This blurs the ‘clear separation between the creative and business aspects of making music’ (Klein, Citation2020, p. 65), thus diminishing self-released musicians’ autonomy still further.

Datafication and commodification are the basis for MSPs curating the content provided by self-releasing musicians. Highlighting what is ‘trending’ is one major way to push certain topics, activities and services (Gillespie, Citation2016). TME follows a very hierarchical logic of selecting trending charts and artists. First, Tencent Musician releases and distributes weekly updated official charts to four platforms, based on its algorithmic interpretation of newly released songs on the platform. These charts then form the basis of playlists. These rankings and playlists need to compete with the different business goals of TME platforms, and as a result, self-releasing charts are relatively hidden in ‘Charts’ sections. Even on the music-oriented platform QQ Music where self-releasing might achieve greater visibility, the charts section still operates as a contested field where self-released content must compete with established acts. So trending charts prioritise popular or mainstream playlists, with the ‘Tencent Musician’ chart only apparent in the ‘Specialist Charts’ section and shown as having the least popularity. So chart curation is subject to the ‘tiered governance’ (Caplan & Gillespie, Citation2020) of TME platforms regarding business orientation and copyright hierarchy. Second, the presentation of artists is also very hierarchical. In the ‘Musicians’ section under the Music Library tab of the main page, songs and musicians are organised according to popularity, featuring major stars and their works and hit songs from recent music reality and TV shows that Tencent have produced or to which it has exclusive licenses. Thus, TME’s curation logic reduces the visibility and popularity of self-releasing musicians and associated playlists, reflecting the dominance of content owned by the big copyright owners over content of self-releasing musicians.

4.2. NCM’s self-releasing scheme: NetEase musician

NetEase Cloud Music began in 2013 and launched its self-releasing service NCM Musician in 2016. The second-largest Chinese MSP corporation after TME, NCM claims to have attracted over 200,000 self-releasing musicians into NCM Musician (Ingham, Citation2020), as indicated above. Facing rising costs as a result of having to obtain licenses from TME due to the 99% sublicense regulation outlined earlier, NCM has developed its self-release scheme as a central asset and has done so on the basis of an intensively algorithmically-driven datafication strategy. It emphasises ‘originality’ but in a way that provides significant constraints on musical autonomy in its selection and recommendation.

NCM’s datafication strategy differs from TME in that it is more oriented to gathering data from ordinary users and amateur or semi-professional musicians. NCM Musician positions itself as a space for unsigned singers and songwriters only, but it accepts many cover singers, who display limited originality. Though this may affect the reputation of NCM Musician and carries risks of copyright infringement, it increases the enrolment of NCM musicians because of the low threshold necessary for musician registration. It also increases the metrics of NCM musicians, because users are more familiar with cover songs. NCM uses algorithms which appear to have little concern for music aesthetics. NCM’s Musician Service manager told us: ‘our music evaluation system is automatic, no need for humans. The operation team will be given a list of selected names to decide who and how to promote, but this list is algorithm-decided’ (interview, 23 May, 2018). This dominant algorithmic logic is also evident in music circulation. NCM’s algorithmic system does not consider factors of music aesthetics but works on the basis of data about users’ previous behaviour (interview, 23 May, 2018). The performance of tracks is monitored by an important tool called ‘The Musician Index’, which measures the behavioural and relational characteristics of musicians, problematically adopting the ‘reputation metrics’ (Van Dijck et al., Citation2019) familiar from social media.Footnote4 The datafication of music, via coding musicians’ and fans’ behaviours into algorithms that track and identify ‘high value’ (committed and engaged) artists and ‘high-value’ fans (i.e., those who stay longer) (Prey, Citation2016, pp. 34–35), enables NCM to monetise these groups via targeted advertisements in the start-up screen and in comment areas for songs. The NCM Musician manager told us that ‘the Index is now the fundamental barometer for us to manage the products, and to determine the depths and means of our commercial collaboration’ (interview, 23 May, 2018).

NCM’s self-release scheme thus provides a means to compete with TME’s copyright monopoly. It enables NCM to expand local catalogue and acquire free licenses of song copyrights. It expands local (i.e., Chinese-language) repertoire which enables greater engagement with karaoke, cover versions, and livestreaming. But NCM Musician distinguishes itself from TME by claiming to promote ‘original’ music-making. NCM has embedded free DAW (digital audio workshop) software in its Musician service and has set up an official channel to purchase song copyrights. Though musicians can make money from this, some are concerned about this buy-out deal which they fear leads to a loss of control of essential music assets, i.e., song copyrights and recording copyrights, thereby clearly affecting their autonomy. Meanwhile, the sheer size of the self-releasing population and the amount of ‘user data’ generated out of the datafication of music on the scheme, means that the proprietary algorithms developed in NCM’s indexing have become attractive vehicles for capital investment (Drott, Citation2018, p. 237) and are currently key assets in NCM’s market valuation. NCM is reported to have made losses since its launch in 2013, but the emphasis on ‘originality’, Chinese repertoire and data analytics helped have helped increase the valuation of NCM from $ 3.5 billion in 2018 to $7 billion in 2019 (Li, Citation2019).

Finally, in terms of content selection, NCM differs markedly from TME by prioritising the curation of original music. NCM’s personalised recommendation plays an active role in promoting little-known musicians to users. For example, on its personalised playlists of 30 recommended songs, the portion of self-released music is larger than on TME’s equivalent playlists, which need to balance the exposure of different copyrights. Self-releasing charts are emphasised more than all other charts in the interface. For example, in the ‘Charts’ section of the NCM main page, listeners can see a list of ‘trending’ playlists, featuring original, popular, new releases, local and global playlists, but the ‘Indie Original Playlist’ is forefronted. Notably, NCM prioritises musical value in curating playlists. They invite teams of judges (critics, musicians and producers, and music influencers) to evaluate and select 24 ‘original’ songs out of 50 songs released on NetEase in the previous month. These playlists are not based so much on notions of entrepreneurially-achieved popularity or of copyright priorities, as is the case with TME (as discussed above), as on qualities of ‘independence, open-mindedness and humanism’, in the words of NCM Indie Original Chart’s official explanation of its selection criteria. This less utilitarian evaluation of ‘originality’ is distinct from that of TME, in that human curation of music is valued for its relative autonomy, promoting values of musical quality over those of stardom, celebrity and corporate entertainment. With no spotlight on particular stars, while curating the charts, NCM creates a less hierarchal but ‘vernacular’ community via themed playlists rather than stardom. NCM, therefore, offers some cultural autonomy on its platforms, though in somewhat compromised form – for there is little transparency, with no explanation of the rules and expectations of how the long list of 50 songs is created.

5. Conclusion

Self-releasing schemes in China may appear to permit democratisation but they in fact provide a basis of commodification and centralisation in what, as we showed earlier, is an extraordinarily centralised and integrated system.Footnote5 Drawing on the way that some platform studies integrate political economy and cultural studies (cf. Van Dijck et al., Citation2018), and supplementing it with insights from Toynbee and Stahl’s historical accounts of dialectics of precariousness and autonomy in the commodification of music, we have shown how ‘reservoirs’ of musical labour previously outside the recorded music system have been incorporated into it by platformisation. TME’s schemes offer a heavily datafied evaluation of the work of musicians, based on the goal of strengthening its monopoly in publishing (i.e., composition) copyright ownership, and on a strategy of ‘pan-entertainment’ commodification across its platforms. NCM places a somewhat higher value on autonomous music making, prioritises self-release charts, and shows some interest in music quality in making official playlists. But overall, self-releasing schemes end up occupying a relatively marginal space due to copyright hierarchies and competition between the different ‘sub-platforms’ within the overall platform eco-system. Their purpose is mainly to expand potentially monetisable content within a platform system marked by super-abundance.

TME’s ‘pan-entertainment’ datafication generates greater exposure and diversification of musician revenues, but reduces the autonomy of musicians, positioning them as sources of automated connectivity and real-time datafication. NCM’s strategy aims to develop self-releasing as a central asset for nurturing exclusive copyrights and advancing algorithmic analytics to compete against TME’s domination. But as is the case with TME’s platforms, NetEase’s comprehensive datafication through indexing transforms musicians into ‘data subjects’ (Ruppert, Citation2011) whose identities are subject to the computational configuration of relationships among musicians, users and the platform. Self-release schemes, as algorithmic projects of connectivity and datafication, are embedded in TME’s recentralisation of vertical and horizontal collaboration and NCM’s endeavour to expand catalogue and capitalisation by investors.

Platform mechanisms affect every musician, but those signed to big record companies stand to gain more exposure and income, whereas most self-releasing musicians seek greater control over creation, copyrights, cooperation and curation, only to experience new ‘platformised’ constraints. Our focus has been on limitations on the cultural autonomy of self-releasing musicians, because that is where claims about democratisation have been most apparent. Of course, some self-releasing musicians are aware of the constraints imposed by these platforms and there is some space for them to exercise agency. To achieve greater cultural autonomy, some are now choosing to work with retailer Bandcamp and distributor Believe Digital (see Section 3), or to circulate their music in less commercial online spaces such as the Douban Musician Site, which provides only basic functions such as music uploading, picture and video sharing, and posting about gigs.

These developments should not be thought of as exotic aberrations from some western ‘norm’. Each geo-regional system has its own peculiar and distinctive paths, and we have tried to characterise them here using the case of China. Analysis of western dynamics might similarly focus on how dynamics of supposed democratisation, where hundreds of thousands of musicians gain access to MSPs such as YouTube, Spotify and Soundcloud, serve to incorporate reservoirs of musical labour previously outside the core, or on its margins, into a datafied, platformised system.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Shuwen Qu

Shuwen Qu is the Associate Professor in the School of Journalism and Communication at the Jinan University. Her research interests include cultural studies, popular music, music technology and communication. Now she is working on the research projects of the platformization of music industry and its impacts on the musical experiences [email: [email protected]].

David Hesmondhalgh

David Hesmondhalgh is Professor of Media, Music and Culture in the school of Media and Communication in Leeds University. His research interest includes digital platforms in the realm of culture, media studies and the cultural and creative industries [email: [email protected]].

Jian Xiao

Jian Xiao is the associate professor at School of Media and International Culture, Zhejiang University. She has published a monograph, ‘Punk Culture in Contemporary China’ with Palgrave Macmillan. Her research interest is focused on urban politics, new media, and cultural studies [email: [email protected]].

Notes

1 Of course in recent years, work in many sectors, including cultural ones, has moved even more in this direction of precariousness.

2 In early July of 2021, as part of a more general set of measures concerning China’s tech sector, China’s competition regulator, the State Administration for Market Regulation, required Tencent to pay a fine of 500,000 yuan (around $77,150) for its anti-competitive practices, and to relinquish exclusivity rights on existing catalogue. However, this does not affect deals formed directly with self-releasing artists, and this latter fact makes clear the importance of research in this area (Cooke, Citation2021).

3 Data management provides information about the demographic make-up of audiences, streams or plays, and revenue musicians gain from ads splits, subscriptions, downloads, etc. Tipping allows audiences to tip whatever amount of money for songs they like – the tipping income, after platforms take a commission, goes directly to musicians.

4 The behavioural data is based on the amount of engagement of musicians and the time of listening of fans, as well as the relational data of the interaction between musicians and fans. Interview, NCM Musician Program manager, August 2018.

5 As mentioned earlier, Xiami closed in 2021. This was the Chinese music platform most imbued with notions of musical autonomy.

References

- An, N. (2016, June 23). Within five years, China will become the largest digital music market of payed music [五年内, 中国将成为全球最大的付费数字音乐市场]. http://www.idaolue.com/News/Detail.aspx?id=1465

- Anderson, C. (2014). The long tail. Hachette.

- Banks, M., Gill, R., & Taylor, S. (2013). Theorizing cultural work. Routledge.

- Baym, N. K. (2018). Playing to the crowd. NYU Press.

- Bennett, A. (2018). Youth, music and DIY careers. Cultural Sociology, 12(2), 133–139. https://doi.org/10.1177/1749975518765858

- Caplan, R., & Gillespie, T. (2020). Tiered governance and demonetization: The shifting terms of labor and compensation in the platform economy. Social Media + Society, 6(2), 205630512093663. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120936636

- Cooke, C. (2018). Dissecting the digital dollar (2nd ed.). CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

- Cooke, C. (2021). Tencent share price dips as Chinese regulator confirms exclusivity deal ban. Retrieved July 27, 2021, from https://completemusicupdate.com/article/tencent-share-price-dips-as-chinese-regulator-confirms-exclusivity-deal-ban/

- De Kloet, J. (2010). China with a cut. Amsterdam University Press.

- Dong, C. (2021, January 15). Tencent Music‘s secondary listing: slowing growth, how to break the ceiling? [腾讯音乐二次上市:业绩增速放缓, 如何打破天花板?]. https://xueqiu.com/4649754500/168887331

- Dredge, S. (2013). Spotify vs musicians. Retrieved October 10, 2020, from https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2013/jul/29/spotify-vs-musicians-streaming-royalties

- Drott, E. (2018). Music as a technology of surveillance. Journal of the Society for American Music, 12(3), 233–267. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1752196318000196

- Eriksson, M., & Johansson, A. (2017). “Keep smiling!” Time, functionality and intimacy in Spotify’s featured playlists. Cultural Analysis, 16(1), 67–82.

- Gillespie, T. (2016). Trending is trending. In R. Seyfert & J. Roberge (Eds.), Algorithmic cultures (pp. 52–75). Routledge.

- Haynes, J., & Marshall, L. (2018). Beats and tweets: Social media in the careers of independent musicians. New Media & Society, 20(5), 1973–1993. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444817711404

- Hesmondhalgh, D. (2016). Exploitation and media labor. In R. Maxwell (Ed.), The Routledge Companion to Labor and Media (pp. 30–39). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203404119.ch3

- Hesmondhalgh, David. (2020). Is music streaming bad for musicians? Problems of evidence and argument. New Media & Society, 146144482095354. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820953541

- Hesmondhalgh, David, Jones, Ellis, & Rauh, Andreas. (2019). SoundCloud and Bandcamp as alternative music platforms. Social Media + Society, 5(4), 205630511988342. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305119883429

- IFPI. (2021). Global music report: Data and analysis for 2020.

- Ingham, T. (2019). DIY artists will earn more than $1 billion this year. No wonder the major labels want their business. Retrieved December 12, 2020, from https://www.rollingstone.com/pro/features/diy-artists-will-earn-more-than-1-billion-this-year-no-wonder-the-major-labels-want-their-business-830863/

- Ingham, T. (2020). The independent artist market is exploding in China – with NetEase and Tencent battling to woo the best indie acts. Retrieved January 20, 2021, from https://www.musicbusinessworldwide.com/the-independent-artist-market-is-exploding-in-china-with-netease-and-tencent-in-a-battle-to-woo-the-countrys-best-indie-acts/#:~:text = It%20concluded%20that%2C%20since%202017,first%2010%20months%20of%202020

- Jian, M. (2018). The survival struggle and resistant politics of a DIY music career in East Asia: Case studies of China and Taiwan. Cultural Sociology, 12(2), 224–240. https://doi.org/10.1177/1749975518756535

- Jiang, J. (2015). Interview with Jiang Jie, Manager of the department of Tencent data platform: Accurate real-time recommendation is the foundation of Tencent‘s billion yuan advertising [专访腾讯数据平台部总经理蒋杰:腾讯数十亿广告的基础是精准实时推荐]. Huxiu. http://www.kejilie.com/huxiu/article/FCB52397A277BCBA9D30DA2C6862ADC6.html

- Jones, E. (2019). DIY and popular music: Mapping an ambivalent relationship across three historical case studies. Popular Music and Society, 44(1), 60–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/03007766.2019.1671112

- Keane, M. (2007). Created in China: The great new leap forward. Routledge.

- Klein, B. (2020). Selling out. Bloomsbury Academic.

- Li, C. Z. (2019, May 27). Pay rate less than 5% can be profitable, Tencent music can “lie to win”? [付费率不及5%都能盈利, 腾讯音乐能“躺赢”吗?]. CLS. https://www.cls.cn/detail/350635

- Li, T. (2019, September 6). Ali adds 700 million dollar stakes to regenerate NetEase Cloud Music [阿里7亿美元加注, 网易云音乐回血]. Huxiu. https://m.huxiu.com/article/316858.html

- Marshall, L. (2015). “Let’s keep music special. F— Spotify”: On-demand streaming and the controversy over artist royalties. Creative Industries Journal, 8(2), 177–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/17510694.2015.1096618

- Miège, B. (1989). The capitalization of cultural production. International General.

- Mulligan, M. (2015). Awakening: the music industry in the digital age. MIDiA.

- Mulligan, M., & Jopling, K. (2020). Independent artists: Pathfinding through a pandemic. MiDIA.

- Nieborg, D. B., & Poell, T. (2018). The platformization of cultural production: Theorizing the contingent cultural commodity. New Media & Society, 20(11), 4275–4292. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444818769694

- Pan, WT. (2018). Exclusive copyright to attract users to enter; Direct sign musicians control recommend (maintain) a premium brand [独家版权吸引用户入驻; 直签音乐人控制厂牌推荐 (维持) 溢价]. Hua Chuang Securities. http://pdf.dfcfw.com/pdf/H3_AP201812241279056778_1.pdf

- Pelly, L. (2018). Unfree Agents: Spotify pushes an Uber-like model for independent artists. The Baffler. https://thebaffler.com/downstream/unfree-agents-pelly

- Poell, T., Nieborg, D., & van Dijck, J. (2019). Platformisation. Internet Policy Review, 8(4), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.14763/2019.4.1425

- Prey, R. (2016). Musica analytica: The datafication of listening. In R. Nowak (Ed.), Networked music cultures (pp. 31–48). Palgrave.

- Prey, R. (2018). Nothing personal: Algorithmic individuation on music streaming platforms. Media, Culture & Society, 40(7), 1086–1100. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443717745147

- Prey, R. (2020). Locating power in platformization: Music streaming playlists and curatorial power. Social Media+ Society, 6(2), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120933291

- Qu, SW. (2017). The discursive mapping and scene reconstruction of Chinese indie music [中国独立音乐的话语流变与场景重构]. Literature and Art Studies, 11, 113–126.

- Ruppert, E. (2011). Population objects: Interpassive subjects. Sociology, 45(2), 218–233. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038510394027

- Shen, X., Williams, R., Zheng, S., Liu, Y., Li, Y., & Gerst, M. (2019). Digital online music in China – A “laboratory” for business experiment. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 139, 235–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2018.10.022

- Sinnreich, A. (2016). Slicing the pie: The search for an equitable recorded music industry. In P. Wikstrom & R. DeFillippi (Eds.), Business and innovation and disruption in the music industry (pp. 153–174). Edward Elgar.

- Stahl, M. (2013). Unfree masters. Duke University Press.

- Sun, H. (2018). Digital revolution tamed. Peter Lang Publishing.

- Tang, D., & Lyons, R. (2016). An ecosystem lens: Putting China’s digital music industry into focus. Global Media and China, 1(4), 350–371. https://doi.org/10.1177/2059436416685101

- Towse, R. (2020). Dealing with digital: The economic organisation of streamed music. Media, Culture & Society, 42(7-8), 1461–1478. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443720919376

- Toynbee, J. (2000). Making popular music. Arnold.

- Van Dijck, J., Nieborg, D., & Poell, T. (2019). Reframing platform power. Internet Policy Review, 8(2), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.14763/2019.2.1414

- Van Dijck, J., Poell, T., & De Waal, M. (2018). The platform society. Oxford University Press.

- Xuan, Y. (2020, March 17). After the copyright dispute, Tencent Music and NetEase cloud music “war” burned to independent musicians, live broadcast and other fields [版权之争后, 腾讯音乐与网易云音乐的”战火”烧到独立音乐人、直播等多个领域]. 36Ke. https://www.36kr.com/p/1725272834049