ABSTRACT

This paper traces the recent turn to humour, irony and ambiguity embodied in the adaptation of memes into the repertoire of online propaganda of the militant neo-Nazi group the Nordic Resistance Movement; in a process, we dub the ‘memefication’ of white supremacism. Drawing on a combination of quantitative visual content analysis (VCA) and in-depth visual analysis focused on iconography and symbolism, we explore all memes (N = 634) created and circulated by the group around the 2018 general elections in the country. The analysis proceeds in two steps: First, we present the results of the VCA in which we identified five thematic categories of memes crafting white supremacy, xenophobia, homophobia, misogyny and anti-Semitic ideas onto esoteric and popular culture iconography then to map these across a matrix of content and form. We then proceed to the analysis of the cluster of memes coded as violent to explore the iconography and symbolism used to promote violence and death threats and render them banal. We draw on a range of recent scholarship on the entanglement of memes in the rise of the far-right and engage critical perspectives on the necropower of fascism to explore the interplay between ambiguous, playful and jokey imagery on the one hand and the murder fantasies and serious threat of white supremacist violence at the heart of neo-Nazi ideology, on the other.

Introduction

For some time now, memes have been associated with vernacular and participatory digital cultures online (Philips, Citation2019), the communication repertoire of democratic social movements, vibrant political debate and campaigns for solidarity or justice (Bayerl & Stoynov, Citation2016; Jensen et al., Citation2020; Milner, Citation2013) and even counter-terrorism efforts from below (McCrow-Young & Mortensen, Citation2021). However, these ephemeral and bite-sized images have recently had ‘a reactionary turn’ and have become deeply entangled with mischievous and far-right subcultures online (Tuters & Hagen, Citation2020, p. 2218) and the propaganda apparatus of violent extremist actors. Memes thus not only abound in fringe and early internet cultural spaces like 4chan and Reddit but also increasingly form an essential part of the toolbox of violent actors within extreme-right movements, including male supremacist and white supremacist groups (Askanius, Citation2021a; DeCook, Citation2018). The adaptation of memes by white supremacist groups is an important potential driver in online radicalisation into far-right extremism. Previous research indicates that memes serve as an effective means to convey key ideological narratives, attract new supporters and contribute to rendering extremist thought mainstream (Bogerts & Fielitz, Citation2019). Because online memes are ephemeral and often shared anonymously, they enable new, experimental and playful engagements with far-right ideas in ways that could act as a gateway to later, stronger commitments (Miller-Idriss, Citation2019; Moreno-Almeida & Gerbaudo, Citation2021). Yet, the exact role of memes in processes of online radicalisation and their implications for the visual construction of white supremacism and violent extremism more generally remains relatively unexplored. So too do the workings of the specific symbols and iconography involved in this process, which we might dub a ‘memefication’ of white supremacism. To understand the political potency of memes and the increasing role they play in contemporary far-right propaganda, we need to understand their main tenets and the litany of coded visual language from which they draw and generate new meaning.

During the insurgency against the Capitol on 6 January 2021, we saw a motley array of symbols and iconography well-known from contemporary white supremacist and extremist groups on full public display in Washington DC. Besides the multitude of different MAGA regalia, confederate flags and Trump merch, the signature Hawaiian shirts of the Boogaloo movement, Crusader crosses and Germanic pagan imagery of right-wing militias and different versions of QAnon iconography, for example, on clothes with the letter ‘Q’ or banners with slogans like ‘Trust the Plan’ were on display. Equally omnipresent was the widely recognised insignia of the alt-right, Pepe the Frog and the appurtenant green-and-white flag of Kekistan (mimicking the German Empire’s Reichskriegsflagge) – a fictional country where Pepe’s avatar Kek rules, all conjured up in the meme-driven culture of 4chan, Reddit and other Alt-Tech platforms. These symbols, many of which were not so long ago relegated to the fringes of online subcultures, today seem to travel seamlessly back and forth between online and offline spaces and transit into real-life political mobilisations. The deadly outcome, the vitriol and violence of the insurgency stand in stark contrast to the colourful and somewhat comic imagery and symbolism on display in DC, which is informed by the very same ‘humorous ambiguity’ (Bogerts & Fielitz, Citation2019) or ‘mischievous ambivalence’ (Philips & Milner, Citation2017) that saturates memes. However, the events leave little ambiguity around what a ‘white nationalist’ take-over would look like, and it remains to be seen whether the events will put an end once and for all to the ‘just joking’ veil in which far-right memes are so often cloaked.

This article takes an interest in the symbols and iconography of white supremacist memes and their role in pushing the boundaries of public discourse by trivialising and normalising messages of hate, violence and death threats. We anchor these concerns in a specific national context, that of Sweden, and through the prism of a particular empirical case, that of the militant neo-Nazi group the Nordic Resistance Movement; currently the biggest and most active extreme-right actor with an explicitly violent and ‘revolutionary’ agenda in Scandinavia, which, in 2017, introduced memes as part of its propaganda repertoire. We ask: How do neo-Nazi memes promote and banalise violence and death threats and what are the key symbols and iconography involved in this process? We use the case of NRM to demonstrate how memes allow white supremacism with its cultures of violence, including fantasies of ethno-national ‘purity’ through violence, public executions and the toppling of democracy, to intersect with the more mainstream political currents and ideas they feed off.

Weaponising the visual: the far-right’s turn to memes

As ‘bite-sized nuggets of political ideology and culture that are easily digestible’ (DeCook, Citation2018, p. 485), memes employ humour and rich intertextuality and are meant to be shared in social media where they ‘[pass] along from person to person, yet gradually [scale] into a shared social phenomenon’ (Shifman, Citation2013, p. 364). Far-right actors have co-opted this online phenomenon to dress up hate speech with dark humour, pop-culture references, quirky GIFs and catchy phrases. Tapping into contemporary digital subcultures allows such actors to cloak anti-democratic messages in the attires of depoliticised cultural consumption. Memes feed off a pool of content that appeals to ‘multiple audiences far beyond those who unambiguously identify with neo-Nazi and other far-right symbolism’ (Bogerts & Fielitz, Citation2019, p. 150). The co-optation of memes and the digital subcultures from which they stem involve a wide range of iconography and symbols that entail carefully coded references that rely on and market to the observer’s knowledge of far-right ideology (Miller-Idriss, Citation2018, p. 6). The humanoid cartoon frog, Pepe the Frog, is but one such by now well-known example. While memes commonly emerge on so-called Alt-Tech platforms (such as 4chan, 8kun, Reddit, Gab and Imgur, see Donovan et al., Citation2019), they increasingly tend to leave the fringe communities of the global far-right and travel through what Ebner (Citation2019) describes as a circular online influence ecosystem across mainstream social media platforms in a variety of bigoted guises.

But the weaponisation of visuals in far-right propaganda is not new. Well aware of the power of visuals to appeal to the masses, build affective bonds, package and sell political agendas and transform ideology into a marketable object of consumption, fascist regimes have been prolific in aestheticising politics in the past (Benjamin, (Citation1979 [Citation1930]); Koepnick, Citation1999; Ravetto, Citation2001). The concept of the aestheticisation of politics was first coined by Walter Benjamin (Citation1930) in his analysis of German fascism. Although Nazi Germany railed against the poisons of modernity, they knew how to deploy the latest technology to relay their message effectively. Through technologically innovative movies, orchestrated mass rallies, the excessive use of brand symbols and Führerkult imagery, German fascism ‘endorsed seemingly unpolitical spaces of private commodity consumption so as to reinforce political conformity’ (Koepnick, Citation1999, p. 52). Culture and entertainment allowed historic Nazism to gain mass support by ‘offering something to everyone’ (Koepnick, Citation1999). Placing the role of visuals in fascist propaganda in a historical context helps us understand today’s memefication of white supremacism as an evolution of the aesthetisation of fascism. Similar to fascist propaganda of the Third Reich, memes wrap ideology in easily digestible narratives and appealing visuals that are designed and marketed to appeal to ‘modern consumers’ (Koepnick, Citation1999).

While the actual political potency of memes remains contested (Wiggins, Citation2016), research indicates that they are potentially powerful drivers in processes of online radicalisation and work as gateways into more extreme and violent content and communities. Yet, knowledge of how memes and online participatory cultures are deployed and co-opted by the far-right is still scarce, just as we know little of how the various visual codes and symbols at the heart of the meaning-making processes of memes move across and translate in different national contexts. While we have previously examined the meme production and practices of this particular group and how their memes display a convergence of traditional neo-Nazi imagery with the visual aesthetics of the alt-right (see Askanius, Citation2021a), in this piece, we take a particular interest in the iconography and symbolism at play in the memefication of white supremacist violence. We do so to disentangle the multivalent (and at first sight confusing/nonsensical) array of different symbols dense with intertextual references to historical and contemporary figures, events, places and debates, in their memes. We hope that by bringing clarity to the layers of relationships between dichotomous categories such as mainstream and esoteric/fringe, violent and non-violent, harmful and harmless in this particular mode of online propaganda, we can shed light on the strategic blurring of these boundaries in violent extremists’ current attempts to reshape and re-invent political action and discourse associated with white supremacism.

Methods and material

The study focuses on the body of memes produced and circulated by the group around the 2018 general elections in Sweden. The sample includes all publicly accessible memes (N = 634) that were published in weekly bundles on NRM’s online hub Nordfront.se in the period from May 2017 – when ‘Memes of the week’ was launched – to December 2018 when the fieldwork ended. To analyse this material, we combine two visual methods, and the analysis proceeds in two steps accordingly. First, we conduct a quantitative visual content analysis (VCA) (Bock et al., Citation2011; Rose, Citation2016) that allows us to code our larger sample of memes and classify it into distinct categories. Through the systematic coding of images, we identified five broad thematic categories. These are (i) anti-establishment (214), (ii) ‘racial strangers’ (145), (iii) anti-Semitism (129), (iv) NRM self-promotion (61) and (v) anti-feminist/LGBTQ (42) memes. The categories were derived inductively and revised multiple times until they were exhaustive and exclusive. We then coded the memes within each category for persons, characters, objects, symbols and text appearing in the images, their intertextual references, and (remixed) stylistic and aesthetic features. This allowed us to further characterise and understand the memes on the spectrum of (a) far-right ideological positions and (b) cultural form.

In a second analytical step, we take an interest in a particular cluster of memes spanning across the five categories that contain markers of violent extremism (N = 67) to explore the visual iconography and symbolism used to promote and banalise violent intent and death threats. Within the broader VCA, this coding process allowed us to systematically map the notoriously slippery notion of våldsbejakandeFootnote1 [adjective signalling someone or something inciting violence], mining the data for explicit and implicit references to violence, genocide, ethnic cleansing and probe for the ways in which coded signs and symbols are weaponised across the thematic clusters of memes. Markers of violence and violent extremism include dead bodies, bodies being beaten/violated, as well as indirect markers of violence such as references to the Third Reich (concentration camps, swastikas, the portrayal of Hitler), explosives, knives, hangman’s ropes and weapons in general.

To operationalise the qualitative visual analysis of memes coded as violent, we draw on Miller-Idriss’s (Citation2018, Citation2019) extensive work on the role of symbolism and iconography in contemporary extreme-right youth cultures and social movements. While her research focuses specifically on the commercialisation of far-right ideology in the context of clothing brands and consumer goods, we follow her approach to study the visual codes involved in the memefication of neo-Nazi ideology, which follows a similar pattern of ‘encoding historical and contemporary far-right, nationalistic, racist, xenophobic, Islamophobic, and white supremacist references into iconography, textual phrases, colors, scripts [and] motifs’ (Miller-Idriss, Citation2018, p. 4). The concept of iconography is key to understanding the constitutive power of visual culture: ‘images convey meaning beyond their mere aesthetic representation; rather, images and pictures are “encoded texts” that need to be carefully deciphered’ (p. 33). The imagery of the far-right heavily relies on such codes that are interwoven in (modified) symbols of Nordic mythology and nationalist history, as well as references to the Third Reich, the Holocaust, the colonial era, etc. Symbols are multivalent and ‘often do not convey a decisive or direct meaning, but rather an evocative one’ (p. 12). This obviously complicates the unambiguous decoding of images. For legal reasons, far-right imagery may also avoid depicting historical scenes from the Third Reich or explicit links to the Holocaust, making it all the more important to look for and carefully examine (strategically) coded references. The ability to detect, decode and correctly interpret the images is dependent on the viewer’s background knowledge. We draw on previous international research on far-right iconography and symbolism (Bogerts & Fielitz, Citation2019; Doerr, Citation2017; Greene, Citation2019; Miller-Idriss, Citation2018, Citation2019) and on the specificities of Sweden’s extreme-right imagery (Askanius, Citation2021a; Citation2021b; Ekman, Citation2014; Kølvraa, Citation2019; Lööw, Citation2015; Merill, Citation2020) to establish the contextual knowledge needed to decipher the visual codes and subcultural ephemera that NRM uses to promote and banalise violence and death threats.

Understanding neo-Nazi memes across (ideological) content and (cultural) form

On 27 May 2017, NRM launched the campaign Memes of the week [Veckans meme] as part of a larger effort to boost the humour and entertainment end of their online propaganda. The editors of Nordfront present memes as offering ‘a gateway into heavier topics’ and ‘catching the attention of people outside the movement’. Supporters ‘old and young, skilled and unskilled’ are called upon to join the ‘meme war’ on mainstream social media. From its launch to the end of 2020, the weekly meme dump on Nordfront counts 49 editions. The memes antagonise NRM’s political enemies and reiterate the logic of discrimination, exclusion and stereotyping. With NRM’s white supremacist and explicitly violent agenda, their memes go far beyond remixing LOLCats and funny looking frogs to mock opponents and target minorities and the promise/threat of deadly violence in their proclaimed rise to power and revolutionary ‘take-over’ is woven into the imagery in both implicit and explicit ways.

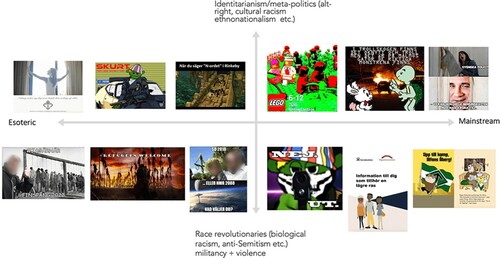

Jumping off the initial categorisation of the memes into five categories, we propose a matrix with which to further examine the images across these thematic strands on a spectrum of first, different ideological positions within the broader extreme-right movement in Sweden and second a continuum of visual symbols and pop-cultural references ranging from the esoteric symbols (impalpable to anyone outside the knowing in-group) to the more mainstream cultural references, including well-known cartoon characters, protagonists in children’s books, logos and graphic design of public institutions, etc. This analytical distinction largely follows Eatwell’s (Citation1996) original categorisation of fascist appeal between the ‘esoteric’ nods and winks to hardcore members and the more populist and palatable ‘exoteric’ modes intended for the general public.

The memes draw from a pool of figures and symbols known from mainstream entertainment and popular culture. These include children’s television characters, toy brands, cartoons characters and video games aesthetics. Together, these elements and their mixing are so consistently deployed that they qualify as a strategy, one that continues the long history of fascist movements’ aestheticising politics. The memes are densely self-referential but also highly intertextual. They display different degrees of explicitness about violent intent and variations over ideological positions on a spectrum between cultural and biological racism and between ethno-nationalism and white supremacy. To make sense of these variations and the juxtaposition of (textual/cultural) forms and (ideological) content, the first steps of the VCA involved positioning the memes in a matrix built around these axes.

(Ideological) content: All of the memes are obviously produced from within or circulated by an explicitly neo-Nazi and white supremacist organisation. Yet, some memes draw more explicitly on references to historical national socialism as an ideology using documentary or cartoon images of Hitler’s Third Reich, Holocaust imagery (denial and ridicule), the swastika or NRM’s own symbol, the Nordic Tyr rune, whereas other memes are discernibly informed by Alt-right ideology and meta-political messages and symbolism. This is the case when, for example, NRM’s messages or logo are projected onto memes of Pepe the Frog or other lesser-known symbols and icons of the Alt-Right such as the OK hand sign, the thumbs-up sign or the 1980s style vaporwave filter. At this upper end of the axis, the ideological core ideas are rooted in ethno-nationalism rather than white supremacy and in expressions of cultural rather than biological racism. The vertical line thus represents two ends of the far-right continuum in terms of the ideological positions, from the ‘softer’ ideas of ethno-nationalism, white identity/nationalism embraced by the Alt-right and identitarian movements to the violent and anti-democratic positions with explicit references to militancy, violence and violent revolution (indicated with weapons, ethnic cleansing, mass executions, race wars, etc.).

(Cultural) form: The second axis positions the memes in accordance with how they draw on pop-cultural references and deploy styles and aesthetics on a scale between the mainstream and the esoteric. With esoteric, we refer to memes remixing symbols, icons and images not immediately known to people outside extreme-right circles. They require a high level of shared (sub)cultural knowledge. Several of the memes make references to Alt-Right iconography and discourse, for example, by featuring seemingly harmless characters such as the Moon Man (originating from a 1980s McDonald’s ad campaign) and the black and white ‘normies’ or ‘feelsman’ image (meant to represent the docile mainstream ‘sheeple’). With mainstream, we refer to memes re-appropriating familiar, to a Swedish audience at least, popular culture references and icons. These include well-known characters from children’s shows such as Alfons Åberg, Skurt and Björne, cartoon characters like Tintin or Bamse; references to Hollywood films or political satire shows (e.g., The Simpsons), commercial brands and merchandise (e.g., Lego and Star Wars). These are symbols with mainstream subcultural currency. Memes at this upper-right end thus possess a certain ‘pop-polyvocality’ (Milner, Citation2013) in that they reflect elements of a ‘pop-cultural common tongue that facilitate a diverse engagement of many voices’ (Milner, Citation2013, p. 65) and therefore have, at least potentially, a broader public appeal.

The co-optation and ‘swedification’ of symbols

Miller-Idriss (Citation2019) distinguishes between three types of far-right symbols: those created by or for far-right consumers, in artefacts intentionally laced with far-right symbols and codes; those that at their origins have no relationship to the far-right but have become co-opted as far-right symbols; and those which deliberately or accidentally deploy far-right symbols and codes, either through attempts to draw media attention, or through ignorance and coincidence. The first two categories in the Miller-Idriss distinction are represented in the memes. The first category obviously includes NRMs own visual logo, an adaptation of the Tyr rune in Norse mythology, and Third Reich Nazi symbols, such as the swastika and the ‘Imperial Eagle’. Co-opted symbols include, for example, the frog puppet Skurt and the teddy bear Björne from 1980s children’s television shows, the literary characters Åsa Nisse and Alfons Åberg, symbols and characters from the film such as Star Wars, Attack on Titan and Dracula Untold. Out of all of these fictional characters co-opted from entertainment and popular culture, the Swedish version of Pepe the Frog, Skurt, occurs most frequently. Originally, Skurt was a small frog-like hand puppet on a Swedish TV show running from 1988 to 2006 – a children’s favourite that is widely known among young and old in Sweden today. Today, the frog with the grinning face and colourful hat is remixed into endless variations of racist, misogynist and anti-Semitic memes to the extent that he has become the face of the Swedish far-right within and beyond Sweden. The malleability of the symbol and the relative ease with which a character such as Skurt is repurposed and transposed into new contexts in a fashion that is easily replicable (Shifman, Citation2013) suggests that these symbols work as empty signifiers; discursive voids into which meaning can be assigned and recruited for different ideological purposes. Today, there are several sites and channels dedicated to producing and posting Skurt memes, and the character has been used frequently and indiscriminately with reference to parties across the far-right spectrum from the Sweden Democrats (SD) and Alternative for Sweden (AfS) to the Nordic Resistance Movement (NRM). Around the 2018 general elections, calls were made on Reddit and 4chan for the international community to help Swedish users make ‘the lad go global’ and to try to influence the outcome of the elections in support of the far-right. While these efforts did not pan out in any significant way (Colliver et al., Citation2018), the collective efforts of users in these communities, well-versed in the vernacular arts of remixing open-ended and nebulous symbols, have arguably turned Skurt into a far-right mascot with some degree of success.

But perhaps the most ‘creative’ example of an elaborately co-opted sign is that involved in the series of execution memes set in the small industrial town Finspång in the northern part of the country, which started to circulate in 2017. The memes recount a fictional/future tribunal to take place after fascist take-over in 2022 in which ‘traitors of the people’ (politicians, journalists, researchers, feminists and women in relationships with non-white men) will be held accountable for their betrayal against the nation and hanged from lamp posts and cranes across the country. Once ‘justice has been served’, Finspång will be turned into a ‘white reserve’ to protect the population’s ‘biological exceptionalism’ from the dangers of the Muslim invasion and/or the collapse of society under the burdens of multiculturalism more generally. The memes are built from stock photographs or caricatures of those considered to fall into the category ‘traitor of the people’ accompanied by the text ‘Finspång 2022’ or the more direct ‘We are going to Finspång’ or ‘See you in Finspång’, the latter being an allegory to the expression of German extremists who use the phrase ‘See you in Walhalla’ referencing the halls of death in Norse mythology (Miller-Idriss, Citation2019). The slogan was also recently referenced at the end of the manifesto of the right-wing terrorist behind the Christchurch massacre in New Zealand. In this manner, ‘a real place, rooted in the offline world, became a fantastical place in online spaces and was infused with far-right meanings’ (p. 128). To be sure, the Finspång memes represent the most explicit articulation of death threats in the batch of memes examined, an aspect we unpack in the final sections of the analysis focusing on the iconography of death and violence.

Much like other far-right symbols before them, both Skurt and the town of Finspång are arbitrary signs in the sense that there is no clear reason why this exact puppet or town should become symbols of neo-Nazi ideology over others. Such co-optations of symbols and their coincidental evolutions as such defies explanation through traditional theories about how symbols work, according to Miller-Idriss (Citation2018, Citation2019). At the heart of this disruption between logical and linear association between symbols and their intended meanings are the online subcultural communities and the global nature of the internet, which have profoundly changed the ways in which ideological messages are produced, circulated and consumed.

In this sense, the NRM memes draw on and add meaning to symbols, icons and narrative conventions well-known to far-right supporters globally. But they are also distinctly Swedish and draw on a range of symbols and cultural references one would have to be knowledgeable of the political context of Sweden to fully understand. Both Skurt and Finspång provide ample evidence of how symbols are not merely adopted wholesale but rather translated to make sense in and add meaning to specific national contexts, conflicts and public conversations. The case of NRM and how this particular actor has adopted a cultural phenomenon with the global purchase by tapping into a subcultural lingo of the far-right internationally, thus also shed light on the transnationalisation processes through which memes, and their visual codes, travel and find new meaning in local/national contexts. Further, we might argue that both ‘Skurt’ and ‘Finspång’ have become so commonplace in memes and other imagery across the Swedish far-right that they qualify as subcultural icons in this ideological context, although their ‘status’ as such might turn out to be short-lived. Indeed, as argued by Mortensen (Citation2016), ‘online construction of icons is more transient’ and ‘less controllable and predictable because it involves more actors, more media platforms, and a greater geographical spread’ (p. 410). But we may understand these as icons in the sense that they have become embedded into ‘standard frames of reference’ among the groups, networks, alternative ‘news’ media and online spaces that make up the far-right in the country to such an extent that they in the end ‘seem to require no particular explanation, and are often proclaimed to “speak for themselves”’ (Mortensen (Citation2016)) in these circles.

The iconography of death threats and violence

In these final analytical steps, we explore the interplay between the ambiguous, playful and jokey imagery of the memes and the visual constructions of murder fantasies and serious threat of white supremacist violence at the heart of neo-Nazi ideology. The majority of all memes coded as violent (N = 67) target those individuals and groups deemed not to belong to or to pose a threat to the nation.Footnote2 The iconography of violence in these memes is intricately tied to symbols of death and dying. This is important, Miller-Idriss (Citation2018) argues, as ‘[d]eath is the penultimate celebration and valorisation of violence that is so central to far-right identity and ideology’ (p. 109). Symbols of death act as straightforward threats of violence and physical harm, evoking both a general and unspecified fear as well as a more specific threat against certain ethnic, religious or racial minorities (Miller-Idriss (Citation2018)). The aesthetic moment in fascist propaganda has a history of reconfiguring perceptions so that they prefigure and culminate in violence and warfare, which constitutes the climax of alternative fascist modernity (Koepnick, Citation1999, p. 53). Although symbols of violence, often combined with historical or mythological references, are ubiquitous in far-right subcultures, themes of violent threat, dying and death have so far received little to no attention within the scholarship on far-right extremism (p. 108). This second part of the analysis responds to Miller-Idriss’s call for the social sciences to further deepen our knowledge on the iconographic representations of death and dying and their relation to militant violence. While the valorisation of violence that characterises these memes clearly places them on the lower, ‘race revolutionary’, end of the matrix presented in , the wide range of symbols and codes deployed to visualise violent intent distributes these memes across the mainstream and esoteric scale of our matrix. This is significant for the potential appeal of the memes to both in-groups and out-groups, as detailed in the sections below in which we follow Miller-Idriss’s (Citation2018) typology of three key iconographic representations of death in far-right products and symbols to structure the analysis of abstract/implicit violence, specific/explicit violence and threats of (deadly) violence at play in the memes.

Abstract/implicit violence

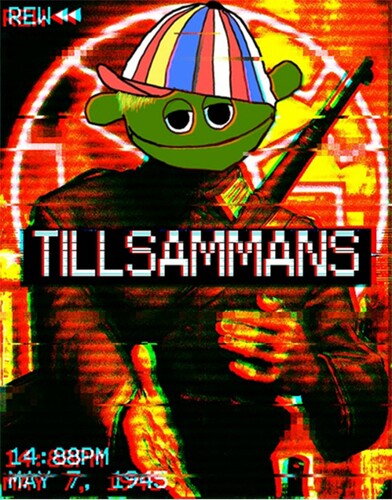

Memes with abstract depictions of violence convey the thought or idea of causing physical harm rather than directly depicting violent action, death or dying. In this category of violent memes, ideological motivation and violent intent are carefully disguised through a range of esoteric far-right codes on the one hand and seemingly harmless ‘humorous’ mainstream references on the other hand. In the example below, we see this dynamic at work in one of the many Skurt memes ().

This meme shows the smiling frog head on the body of a German WW2 Wehrmacht soldier who extends a hand towards the observer, inviting him/her to fight ‘together’. The Nazi/WW2 references and their (implicit) violent intent are cleverly nested in esoteric codes and symbols. In the background, we see a blazing Black Sun (or Sun Wheel), an ancient European symbol that was appropriated by the Nazis and was inscribed in the SS headquarters of Wewelsburg. With its three superimposed swastikas, the occult symbol is often used as a (less recognisable and not prohibited) substitute for the swastika (Bogerts & Fielitz, Citation2019, p. 147). The textual references ‘REW’ for ‘rewind’ and ‘May 7, 1945’ place the meme in a specific historical context, namely the day of Germany’s official military surrender at the end of WW2. From what the (deliberately) pixelated meme allows us to see, the soldier’s uniform has the typical collar patch of the Wehrmacht, and his gun resembles a Mauser Karabiner 98k, the most common infantry rifle within the German Army during the war. The timecode 14:88 is a combination of two popular white supremacist numeric symbols. 14 is shorthand for the 14 words ‘We must secure the existence of our people and a future for white children’ penned by white supremacist David Lane (1938–2007) as a unifying slogan for an international militant Aryan uprising. The number 88 is a coded symbol for ‘Heil Hitler’ (H being the 8th letter of the alphabet).

The sympathy with National Socialism and its violent history is thus woven into a bricolage of ‘complex layers of intertextual references, which require literacy to decode’ (Tuters & Hagen, Citation2020, p. 8). Impalpable to anyone outside the group, the iconography of this type of meme fosters an in-group belonging among those fluent in neo-Nazi vernacular. The symbols and codes can be understood as a form of ‘performative communication’ in the sense that they do not only express and market ‘ideological beliefs, but also to strengthen a sense of belonging among group members’ (Miller-Idriss, Citation2018, p. 52). This makes this cultural expression a key driver in stimulating in-/out-group distinctions, ‘not through political opposition, but rather through the implicit formation of an “us”’ and “them” comprised, respectively, of those aware and of those unaware of a meme’s subcultural currency’ (Tuters & Hagen, Citation2020, p. 8) . By remixing esoteric far-right symbols with a seemingly innocuous pop-culture character, the iconography of such memes makes it possible to promote and celebrate violent intent in subtle, not overtly violent ways that would otherwise, if spelled out, be abhorred by the general public.

Specific/explicit violence

The second category of violent memes goes beyond abstract depictions and, instead, is characterised by a specific, straightforward display of violence that threatens factual people (politicians, journalists, etc.) with serious/deathly violence and/or those targeted groups considered to pose a threat to ‘the nation as a place with particular kinds of ethnic, racial, religious, linguistic, or cultural boundaries’ (Miller-Idriss, Citation2018, p. 116). What makes the violent intent so explicit in these memes is not only the depictions of weapons (guns, (laser)swords, artillery, etc.), dead bodies and blood but also the image-text combinations (titles, descriptions and direct speech) that make it easy to re-contextualise well-known imagery from mainstream popular culture and give them completely new meanings (Bogerts & Fielitz, Citation2019, p. 150).

The example below () shows a scene from the movie Dracula Untold (2014) that retells the story of the historical figure Vlad the Impaler (who later turns into the undead vampire Dracula) in fifteenth-century Transylvania. The movie presents the warlord sociopath Vlad, in this version known for allegedly slaughtering thousands of his Ottoman foes by impaling them on stakes, as a misunderstood hero. The recurring themes of the vilification of Islam and the fear of a Muslim Europe make the narrative well-suited for far-right Islamophobic propaganda.

By adding #refugees welcome – the well-known slogan of the migrant solidarity movement which formed in Europe during the border crisis of 2015–2016 to the gory scene depicting a forest of impaled bodies (Vlad’s allegedly Muslim enemies), the meme uses a historic anti-Islam reference to re-direct meaning to what was originally a pro-refugee solidarity slogan to show support for newly arrived refugees a new, diametrically opposite, meaning. The explicitly violent iconography in these memes effectively creates existential antagonisms that juxtapose an organic and classless ‘us’ with a nebulous ‘them’ (Tuters & Hagen, Citation2020). While the white supremacist agenda remains subtle or cleverly disguised in the first category of implicitly violent memes, these latter examples make little or no effort to conceal their message that certain groups are not only unwelcome; – they must be eradicated. Memes in this category clearly assert a willingness to go far beyond what is deemed socially acceptable and, at the same time, demonstrate how the lines of legality regulating hate speech are carefully toed.

Threats of (deadly) violence

While in the previous category, ‘violence is celebrated as a strategy to achieve a particular outcome’, in this last cluster of violent iconographies, ‘the end goal is the restoration of a dying civilization’ (Miller-Idriss, Citation2018, p. 117). The threat of (deadly) violence is framed around the need for the rebirth of a national socialist society. Far-right threats of violence are often embedded in specific future-oriented, hypothetical scenarios that sketch the idea of an ‘aspirational nationhood’ (Miller-Idriss, Citation2018). Such ‘fantasy expressions of a nation that never existed but that is, nonetheless, aspired to’ (Miller-Idriss, Citation2018, p. 109) are most clearly reflected in the Finspång memes that proclaim the preservation of white purity and the superiority of the Aryan race in remarkably overt and unabashed ways, even for this specific actor in the Swedish context. As a particularly unsettling ‘revenge fantasy’ built around more mainstream far-right imaginaries of the collapse of Sweden (Titley, Citation2019, p. 1013), Finspång not only celebrates and valorises violence but normalises linkages between anti-establishment sentiments and racial fantasies of national degeneration with ideas of justifiable violence and ultimately mass murder ().

Figure 4. Series of Finspång memes. Top: Election campaign meme juxtaposing the fast-right party Alternative for Sweden with NRM. Bottom left: Digitally manipulated photo of Holocaust survivors. Bottom right: Picture of executed Soviet Union partisans 349 × 222 mm (72 × 72 DPI).

While executions and hangings are not always directly depicted, the noose serves as a recurring symbol of the death threat and a proxy to the broader Finspång narrative. Such death (threat) symbolism against the establishment serves as a ‘source of resistance, protest, and cultural subversion against perceived hegemonic authorities’ in the extreme-right (Miller-Idriss, Citation2018, p. 111). The iconography of the Finspång memes feeds off a range of different imagery and symbols that contain intertextual, political and historical references to visualise and bring substance to this ultimate revenge fantasy. A key illustration of the rich intertextuality of the execution memes includes the nod to the fictive event ‘Day of the rope’ (carved out in detail in the racist novel The Turner Diaries) in which ‘“race traitors” are summarily lynched, including “the politicians, the lawyers, the businessmen, the TV newscasters, the newspaper reporters and editors, the judges, the teachers, the school officials, the ‘civic leaders’, the bureaucrats, the preachers”, actors and musicians and anyone else who cooperated with the system, as well as anyone who took part in an interracial sexual relationship’ (Berger, Citation2016, p. 12). The execution memes mainly depict ‘impending death’ rather than dead bodies. This death trope evokes the subjunctive ‘as if’ – the voice of the contingent, imaginative ‘of what might be’ stored in the images (Zelizer Citation2010). As such, they provide an externalisation and visualisation of the ‘what if’ of this longstanding revenge fantasy in the extreme-right movement.

Such death tropes propelled by the current rise of far-right movements might usefully be understood ‘to belong to a new moment’ in the long history of the necropolitics that continues to haunt post-colonial liberal democracies (Mbembé Citation2003, p. 30). The third category of explicitly violent iconography provides an excellent window into what Mbembe (Citation2003) calls the twin issues of death and terror at the heart of necropolitical regimes. In the examples of execution memes above, the (imagined) construction of a Pan-Nordic national socialist state is presented as the consolidation of the politically legitimate ‘right to kill’ in the name of the greater good of saving the nation culminating in ‘the final solution’ (i.e., Finspång). In an ‘extrapolation of the theme of the political enemy’ (Mbembé Citation2003, p. 17), the memes put concrete faces and names to the list of the ‘Sweden-enemies’ whose death is both required and just. Such systematic killings are rendered possible/plausible, and necessary even, by the always impending ‘state of exception’ imagined in the peculiar terror formation that is organised racism. Facing societal collapse, chaos and the disintegration of the white nation ‘judicial order can be suspended’ and proponents of national socialism granted the ‘right to wage war (the taking of life)’, Finspång then becomes ‘the zone where the violence of the state of exception is deemed to operate in the service of “civilization”’ (Mbembé Citation2003, p. 24). They convey a nostalgic longing for national socialism to once again have the ‘sovereignty, power and the capacity to dictate who may live and who must die’ (p. 11).

Importantly, the Finspång memes were circulated in a time around the general elections during which the group simultaneously engaged in extensive offline ‘base activism’ around the country in which the fictive/future trials are interwoven into analogue propaganda distributed across cities in the southern part of the country. For example, in November 2018, ‘clear messages to local traitor politicians’ were put up on doors and notice boards at the entry of 21 town halls stating: ‘To politicians in this building: you will pay for your crimes against the Nordic people when put to justice in the future folk tribunal’. In this manner, the death threats travelled back and forth between online and offline space and reached different audiences, many of whom were themselves directly targeted and named as prospective accused for the tribunal.

Concluding reflections

Beyond the context of Sweden, and certainly, beyond this specific white supremacist group, the likes of which tend to come and go, memes are increasingly part of a broader strategy of the far-right to push the boundaries of what is acceptable in mainstream discourse. In important ways, memes are helping move ideas, previously considered beyond the pale in public discourse, to travel and have bearing online. They are key to ongoing efforts among far-right actors to get rid of or re-invent the symbols and visual codes that once defined far-right ideology and white supremacism, more specifically in the pursuit of making it attractive to a new generation of younger audiences. Bogerts and Fielitz (Citation2019) argue that ‘since the far right, too, has undergone a process of (post) modernization, it must be regarded as closely intertwined with post-modern (youth) cultures which express themselves creatively and often ironically on social media’ (p. 150). The neo-Nazi movement in the country has not yet succeeded in recruiting youth in large numbers, but they are certainly tapping into the cultural expressions of contemporary youth culture in their efforts to do so. Indeed, NRM’s memes find inspiration in early internet culture spaces that are rife with symbols ‘easily hijacked by those looking to do harm, whose actions often fly under the radar – because those actions look like the things that used to be fun' (Philips, Citation2019, p. 3).

The carefully coded and remixed symbols and references that were subject to close examination in this study highlight the multivocality of memes and the strategic attempt by an openly Nazi group with a relatively straightforward agenda of violence to tap into the sentiments of ambiguity and nebulosity around earnestness and intent that saturate the subcultural fringes of the internet. It is this malleability and the fusing (and confusing) of the silly and the banal with murder fantasies and threats of white supremacist violence that allow the group to cater to not only to those already identifying with far-right ideology but also to the broader public and those ‘who are keen to avoid the social stigma of the far right while still communicating with insiders’ (Miller-Idriss, Citation2018, p. 62). In this sense, memes work as one of the key techniques in contemporary efforts by far-right movements internationally to counter the stigma of the totalitarianism, genocide and human tragedy still associated with national socialism and help launder white supremacist violence into the mainstream.

To be sure, most of NRM’s memes are rife with violence and death. However, what makes those in the final category described above stand out in comparison to all other violent iconographies in the sample is the mimicry and remix of documentary photography, factual places and concrete people in combination with messages directly articulating death threats and/or evoking death symbolism through past atrocities and fantasies of future genocides. They play around with imagined, phantasmic ideas, yet they mirror and tap into real historical events. Public lynching, trials and executions of traitors and the public display of dismembered bodies of dehumanised Others, parades of heads mounted on sticks – these images may in Western audiences all resonate with atrocities elsewhere or atrocities of the past. They are scenarios and ideas easily written off as inconceivable and confined to the perversions of the uncivil fringes of society among groups classified as marginal, extremist and unwanted by the state. Yet as Mbembé (Citation2003) reminds us, anti-democratic groups such as NMR and the broader movements in which they operate are not exterior to or the antithesis of liberal democracy. Rather they represent its dark side, or what he calls its ‘nocturnal body’, which is based on the very same desires, fears, affects, relations and violence that once drove colonialism. They are the unwelcome reminders of the persistence of necropolitical techniques and ideas within liberal democracies in a Europe consumed by the continued desire for apartheid.

Yet, in order to understand the ways in which fascist iconography lingers in the fibres of contemporary culture and how it works as an entry point for far-right recruitment and radicalisation, it is not enough to have an exclusively visual lexicon of fascist aesthetics (Ravetto, Citation2001). More ethnographically oriented work and audience studies are needed to examine the extent to which out-groups, the mainstream user, and especially youth native to digital subcultural aesthetics, are exposed to memes with violent far-right messaging, how remixed pop cultural references and coded symbols are understood and perceived and what appeal and political potency they may carry. For example, where and how do young people come into contact with such memes in their day-to-day life? What are their ordinary and everyday encounters with radicalisation messages online? Asking these questions will further our knowledge of the extreme right as a site of cultural engagement and help us understand where messages of violent extremism circulate and how they resonate when travelling back and forth between fringe and mainstream spaces today.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Tina Askanius

Tina Askanius is associate professor in media and communication studies at Malmö University and affiliated researcher at the Institute for Futures Studies in Stockholm, Sweden. Her research concerns the interplay between online media, social movements mobilizations and political radicalization. She is currently working on projects related to violent extremism and white supremacist movements in Scandinavia. She has published extensively on social movement media practices in international journals such as Media, Culture & Society, International Journal of Communication, Social Movements, Conflict & Change and Journalism Practice.

Nadine Keller

Nadine Keller is research assistant at the School of Arts and Communication and affiliated with the research platform Rethinking Democracy at Malmö University, Sweden. She holds a MA in Media and Communication Studies. Her work on racism and hate speech has previously been published in the journal Studies in Communication and Media (SCM).

Notes

1 The term ‘våldsbejakande’ is used consistently by intelligence services, state authorities and researchers in the field of extremism and radicalisation in Sweden. It aims to describe violence beyond physical attacks such as murder or abuse to include threats of physical violence as well as limitations of mobility such as detention and forcible resettlement/ethnic expulsions. Further, the term is meant to go beyond direct invitations to such acts to include anti-democratic ideas which legitimate hierarchies of inferiority and superiority between different groups which in turn work to pave the way for explicit incitement to violence (SOU 2013).

2 This cluster of memes fall under three thematic categories: anti-Semitic (25), ‘racial strangers’ (20) and finally ‘traitors of the people’ (16).

References

- Askanius, T. (2021a). On frogs, monkeys, and execution memes: Exploring the humor-hate nexus at the intersection of neo-Nazi and alt-right movements in Sweden. Television & New Media, 22(2), 147–165. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1527476420982234

- Askanius, T. (2021b). I just want to be the friendly face of national socialism. Nordicom Review, 42(1), 17–35. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2478/nor-2021-0004

- Bayerl, P. S., & Stoynov, L. (2016). Revenge by photoshop: Memefying police acts in the public dialogue about injustice. New Media & Society, 18(6), 1006–1026. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444814554747

- Benjamin, W. (1979 [1930). Theories of German fascism: On the collection of essays war and warrior. New German Critique, 17, 120–128. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/488013

- Berger, J. M. (2016). The Turner legacy: The storied origins and enduring impact of white nationalism’s deadly Bible. ICCT Research Papers, 7(8), 1–50. https://doi.org/http://doi.org/10.19165/2016.1.11

- Bock, A., Isermann, H., & Knieper, T. (2011). Quantitative content analysis of the visual. In E. Margolis & L. Pauwels (Eds.), The SAGE handbook visual research methods (pp. 265–283). SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Bogerts, L., & Fielitz, M. (2019). ‘Do you want meme war?’ Understanding the visual memes of the German far right. In M. Fielitz & N. Thurston (Eds.), Post-digital cultures of the far-right online actions and offline consequences in Europe and the US (pp. 137–154). Transcript Verlag.

- Colliver, C., Pomerantsev, P., Applebaum, A., & Birdwell, J. (2018). Smearing Sweden: International influence campaigns in the 2018 Swedish election. LSE Institute of Global Affairs.

- DeCook, J. R. (2018). Memes and symbolic violence: #Proudboys and the use of memes for propaganda and the construction of collective identity. Learning, Media and Technology, 43(4), 485–504. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2018.1544149

- Doerr, N. (2017). Bridging language barriers, bonding against immigrants: A visual case study of transnational network publics created by far-right activists in Europe. Discourse and Society, 28(1), 3–23. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926516676689

- Donovan, J., Lewis, B., & Friedberg, B. (2019). Parallel ports, sociotechnical change from the alt-right to alt-tech. In M. Fielitz & N. Thurston (Eds.), Post-digital cultures of the far-right online actions and offline consequences in Europe and the US, (pp. 49–65). Transcript Verlag.

- Eatwell, R. (1996). Fascism: A history. Allen Lane.

- Ebner, J. (2019). Counter-creativity: Innovative ways to counter far-right communication tactics. In M. Fielitz & N. Thurston (Eds.), Post-digital cultures of the far right online actions and offline consequences in Europe and the US (pp. 169–181). Transcript Verlag.

- Ekman, M. (2014). The dark side of online activism: Swedish right-wing extremist video activism on YouTube. MedieKultur: Journal of Media and Communication Research, 30(56), 21–99. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.7146/mediekultur.v30i56.8967

- Greene, V. S. (2019). ‘Deplorable’ satire: Alt-right memes, white genocide tweets, and redpilling normies. Studies in American Humor, 5(1), 31–69. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5325/studamerhumor.5.1.0031

- Jensen, M., Neumeyer, C., & Rossi, L. (2020). ‘Brussels will land on its feet like a cat’: Motivations for memefying #brusselslockdown. Information, Communication & Society, 23(1), 59–75. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2018.1486866

- Koepnick, L. P. (1999). Fascist aesthetics revisited. Modernism/Modernity, 6(1), 51–73. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1353/mod.1999.0009

- Kølvraa, C. (2019). Embodying ‘the Nordic race’: Imaginaries of viking heritage in the online communications of the nordic resistance movement. Patterns of Prejudice, 53(3), 270–284. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0031322X.2019.1592304

- Lööw, H. (2015). Nazismen i sverige 2000-2014. Ordfront.

- Mbembé, J.-A. (2003). Necropolitics. Public Culture, 15(1), 11–40. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-15-1-11

- McCrow-Young, A., & Mortensen, M. (2021). Countering spectacles of fear: Anonymous’ meme ‘war’ against ISIS. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 1, 1–18. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/13675494211005060

- Merill, S. (2020). Sweden then vs. Sweden now: The memetic normalization of far-right nostalgia. First Monday, 35, 6. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161221995083

- Miller-Idriss, C. (2018). The extreme gone mainstream: Commercialization and far right youth culture in Germany. Princeton University Press.

- Miller-Idriss, C. (2019). What makes a symbol far right? Co-opted and missed meanings in far-right iconography. In M. Fielitz & N. Thurston (Eds.), Post-digital cultures of the far-right online actions and offline consequences in Europe and the US (pp. 123–136). Transcript Verlag.

- Milner, R. M. (2013). Pop polyvocality: Internet memes, public participation, and the occupy wall street movement. International Journal of Communication, 7, 2357–2390.

- Moreno-Almeida, C., & Gerbaudo, P. (2021). Memes and the Moroccan far-right. International Journal of Press/Politics, 1, 1–25. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161221995083

- Mortensen, M. (2016). ‘The image speaks for itself’ – or does it? Instant news icons, impromptu publics, and the 2015 European ‘refugee crisis’. Communication and the Public, 1(4), 409–422. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/2057047316679667

- Philips, W. (2019). It wasn’t just the trolls: Early internet culture, ‘fun,’ and the fires of exclusionary laughter. Social Media and Society, 5(3), 1–4. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305119849493

- Philips, W., & Milner, R. M. (2017). The ambivalent internet: Mischief, oddity, and antagonism online. Polity Press.

- Ravetto, K. (2001). Unmaking of fascist aesthetics. University of Minnesota Press.

- Rose, G. (2016). Visual methodologies: An introduction to researching with visual materials. Sage (atlanta, Ga ).

- Shifman, L. (2013). Memes in a digital world: Reconciling with a conceptual troublemaker. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 18(3), 362. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12013

- Titley, G. (2019). Taboo news about Sweden: The transnational assemblage of a racialized spatial imaginary. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 39(11/12), 1010–1023. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSSP-02-2019-0029

- Tuters, M., & Hagen, S. (2020). (((they))) rule: Memetic antagonism and nebulous othering on 4chan. New Media and Society, 22(12), 2218–2237. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444819888746

- Wiggins, B. E. (2016). Crimea river: Directionality in memes from the Russia-Ukraine conflict. International Journal of Communication, 10, 451–485.

- Zelizer, B. (2010). About to die. How News Images Moves the Public . New York, NY: Oxford University Press.