ABSTRACT

This paper reports the findings of a study of two automatically generated corpora of multimodal digital items user-tagged as ‘Black Lives Matter memes’ and ‘Blue Lives Matter memes’. The central aim is to flesh out the memetic trends representing the discourses and ideologies on the Black and blue memescape, which is explored in the wake of the most infamous but interest-generating tragedy in the history of the Blue Lives Matter movement, namely George Floyd's death at the hands of white police officer Derek Chauvin. Studied through a Multimodal Critical Discourse Analytic lens, the internet memes are shown to contribute to the polyvocal political discussion and, with some neutral or ambiguous exceptions, to display a positive (pro-) or – more often – negative (anti-) stance on each of the opposite movements (with anti-BLM items consituting the largest category in the dataset). Also, contrary to the well-entrenched conceptualisation of memes as a type of humour, the majority of the memes at hand manifest no humorous potential. Humour is present mainly among the negative-stance memes, which points to the disparagement of a target as a concomitant of humour in the memes on this serious political topic.

Introduction: Black Lives Matter, Blue Lives Matter and memes

Commenced in 2013, Black Lives Matter (BLM)Footnote1 is a decentralised Black-liberation movement comprised of many organisations based in the USA, as well as operating worldwide (including Black Lives Matter Global Network Foundation). The movement advocates for policy changes geared towards Black liberation, equal treatment and – notably – against any racially motivated and state-sanctioned acts of violence against Black people, including police brutality. In response to BLM and repeated acts of homicide of law-enforcement officers, the countermovement called Blue Lives Matter (hereafter, BlueLM) was created in 2014 to support the police in the USA.Footnote2

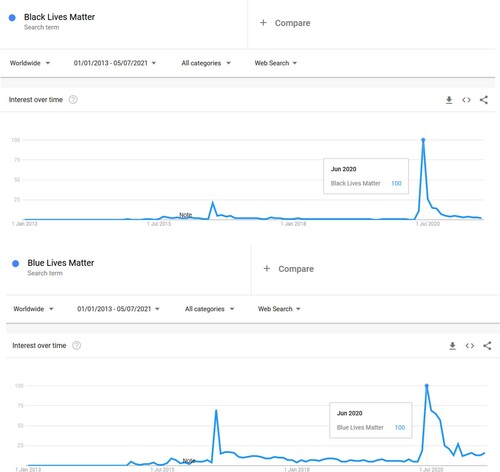

Although BLM bills itself as a non-violent movement calling for peaceable civil disobedience, some of the protests and riots held in the streets are known to have taken rather severe forms, sparking controversies (see also Bock & Figueroa, Citation2018). This was the case with many events that took place in the aftermath of the tragic death of a Black American citizen, George Floyd, on 25th May 2020 in Minneapolis, Minnesota. During Floyd's arrest on suspicion of using a counterfeit bill, a white police officer relentlessly knelt on the captured and handcuffed man's neck, leading to his demise. Similar to a few previous incidents, one of which actually inspired the movement (see Gallagher et al., Citation2018; Ince et al., Citation2017; Jones, Citation2020; Ray et al., Citation2017), this homicide and the legal action taken against the responsible police officer (faced with three charges)Footnote3 further polarised the nation into BLM vs BlueLM supporters. Undoubtedly, Floyd's untimely death reinforced BLM,Footnote4 both offline (giving rise to numerous demonstrations and rallies, as well as riots not only in the USA but also internationally) and online, putting the movement in the public eye like no previous case of racial injustice (see Dixon & Dundes, Citation2020). This is evidenced by Google Trends; Internet users’ peak interest (100) in BLM worldwide – reflected by the intensity of the keyword searches – came in June 2020, and the same holds for BlueLM Google searches (see ). The BlueLM June results do not seem to have been eclipsed even by the news circulated in March 2021 about the charges being brought against the former police officer responsible for the deadly arrest or the unprecedented court rulings (Derek Chauvin was found guilty on all three charges on 20th April 2021 and received a sentence of 22.5 years’ imprisonment on 25th June 2021).Footnote5 However, the police officer's trial and its outcome may explain the moderately high interest in BlueLM in the first half of 2021.

Figure 1. Interest in BLM and BlueLM according to Google Trends since 2013 (status quo on 5th July 2021).

Among other things, users’ social media activity materialises through Internet memes, which are users’ artefacts indicative of participatory digital culture (Wiggins & Bowers, Citation2015). Memes epitomise user-generated content on social media that gives excellent insights into how the general public endorses or challenges existing ideologies (Khosravinik, Citation2017). These are to be thought of as systematic representations of the world shared and agreed on by social groups (e.g., Charteris-Black, Citation2011; van Dijk, Citation1998), which are communicated through various (multimodal) discourses.

Memes have been amply examined as bearers of social critique and vessels for political dissent (e.g., Huntington, Citation2016; Milner, Citation2013, Citation2016; Ross & Rivers, Citation2017, Citation2018; Wiggins, Citation2019). Thus – as can be extrapolated – memes typify a motley assortment of users’ shared beliefs (Milner, Citation2013, Citation2016), crystallising the ideologies in the collective social minds. Memes are also seen as a form of political empowerment and collective social action taken to resist hegemonic discourses, stir up political agitation and facilitate social movements, being vehicles for political activism (e.g., Dynel & Poppi, Citation2020a; Frazer & Carlson, Citation2017; Milner, Citation2013, Citation2016).

It should be pointed out that while the past two decades have seen an explosion of empirical research on memes, there seems to be a lot of (often unnoticed) confusion about this concept. Originally proposed in reference to any item that proliferates through replication (for the history of the notion, see e.g., Shifman, Citation2013; Wiggins & Bowers, Citation2015), presumably in any public space, the term ‘meme’ is nowadays prevalent shorthand for a ‘humorous Internet meme’ (Dynel, Citation2016; Yoon, Citation2016). Thus, memes are conventionally presupposed to be a form of online humour (but see Vickery, Citation2014 on the confession bear memetic trend), whether or not it is the humour per se that is examined and accounted for.Footnote6 However, albeit often conducted by scholars recognised for their contributions to humour research, many studies on memes – duly quoted in humour research – concern (or, at least, contain) non-humorous examples. These are devoid of the basic property of humorous artefacts, that is any form of surprising incongruity subject to resolution (which allows the humour to remain) but not dissolution, as a mathematical puzzle would be (see e.g., Martin & Ford, Citation2018).

Because of the common association between memes and humorous items, the term ‘meme’ tends to be used in both popular and academic parlance in reference to any user-generated humour shared via the Internet. This kind of relaxed approach should not be applied in any solid research. Formally, (Internet) memes are best defined as multimodal, user-generated artefacts (whether or not humorous) occurring in cycles based on the same topic, form, and/or stance, which users create, aware of the previous items, for them to be further circulated via transformation (see Huntington, Citation2016, p. 78; Shifman, Citation2013, p. 41). The notion of a meme's stance (Dynel, Citation2021; Shifman, Citation2013; Wiggins, Citation2019) is of crucial importance when the socio-political content and ideologies communicated in memes are to be elucidated. Taking account of the form and the various nested voices that may be invoked, whether combined or juxtaposed (see Dynel, Citation2021), it is necessary to determine the meme author's stance on the represented topic, which is inextricably connected to the ideology endorsed.

The premises presented in the course of this introduction are the point of departure for the current study, which contributes to the previous research on users’ ideologies about BLM and BlueLM on social media by focusing on relevant memes. While the BLM movement has been widely discussed from various angles across disciplines, this is the first study that aims to gauge the BLM memescape (but see Williams, Citation2020Footnote7 on ‘Black memes’, as well as Yoon, Citation2016Footnote8 on racist memes), as well as BlueLM memescape. This study contributes to the previous research on the Facebook pages of both movements (Bock & Figueroa, Citation2018) and their respective hashtags (Carney, Citation2016; Gallagher et al., Citation2018; Ince et al., Citation2017). Our overarching objective is to explore the movement's conflicting ideologies, as manifest on the international memescape, not associated with any particular platform that could show a specific focus, and hence bias in favour of or against either movement. Specifically, we aim to investigate the distribution of memes, whether or not humorous, supportive (pro-) and/or critical (anti-) of either movement and to delve into the ideological constructs conveyed through recurrent multimodal discourses. Based on two automatically compiled corpora of memes, this paper details the prevailing discourses and ideologies communicated through memes generated and tagged BLM and BlueLM by social media users in the wake of the very impactful events concerning the killing of George Floyd and its socio-political repercussions. This project is thus driven by two main research questions regarding:

the actual frequency of humour among politically loaded memes at hand, with our expectation being that it need not prevail among the memes at hand; and

the nature and diversity of ideological constructs on the Black and blue memescape indicative of the use of memes as political weapons in the pro-Black vs anti-Black conflict, starting from the assumption that there might be more memes manifesting anti-Black bias.

With this project centred on an automatically generated corpus of tagged items, we show a new methodological direction in the research on memes whose aim is to target diversified data (not restricted to pre-selected platforms) and to minimise researcher bias, typically involved in manual collection of datasets comprised of what scholars themselves consider (relevant) memes.

Methodology

A Python script was created by a computer expert to collect data from Google Images through a newly installed browser, thus pre-empting any impact of her previous user searches. The queries ‘“black lives matter” + meme’ and ‘“blue lives matter” + meme’ were applied to retrieve digital items labelled by users as memes relevant to the two movements, based on their lay understandings of the label ‘meme’. This method of data collection, which – to the best of our knowledge – has not been used in the research on memes before, means that many potentially relevant but untagged memes could not be included in the corpus. However, the key merit of this procedure is that the automatically collated items signposted with tags constitute a randomised sample of the memescape at a chosen point in time, without favouring any memes given their source, reach or user engagement. The use of the automatic method was intended to minimise researcher bias (which often characterises manually collected datasets comprised of purposefully cherry-picked examples that serve the authors’ goals). Also, our randomised data were extracted from over 180 websites, as evidenced by our post facto examination of the URLs of the memes in the corpus, offering greater representativeness of the memescape than corpora built on the basis of websites selected a priori (as is often done by meme researchers with goals different to ours), which might potentially carry pre-established ideologies. This is what we wanted to avoid, aiming at a randomised and diversified sample of the Black and blue memescape.

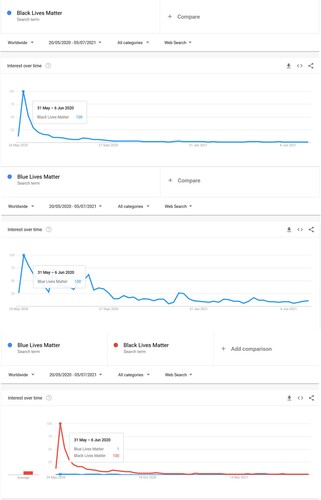

After our deleting a few duplicates within each set (i.e., items reposted with no modifications, potentially indicating the specific memes’ popularity, with which this study is not concerned), the compiled corpora comprise relevant BLM items (n = 531) and BlueLM items (n = 413). These data represent the memetic status quo of 6th July 2020, i.e., seven weeks after the homicide of George Floyd at the hands of the white police officer, when the BLM protests were going strong but enough time had passed for the relevant memescape to develop. Importantly, 6th July 2020 is also one month after the week that Google Trends show as the time of the peak popularity of the search term ‘Black Lives Matter’ not only since the tragic event on 25th May 2020 () but also since the movement came into being in 2013 (cf. ). Both BLM and BlueLM seem to have reached their top popularity as search terms on Google between 31st May and 6th June 2020. However, the comparison of the two trends indicates that BLM eclipses the countermovement's popularity as a Google search term, even though its interest (albeit much lower) does not appear to have dropped so dramatically after the peak, possibly due to Derek Chauvin's trial (). Thus, we worked on the assumption that the highest number of relevant memes could be collected about a month after the peak. Indeed, limiting the Python script search time to one month (6th June – 6th July 2020 as the dates of memes' postings) yielded an overwhelming majority of the items in each corpus (n = 509 for BLM and n = 358 for BlueLM).

Figure 2. Interest in BLM and BlueLM and a comparison of the two on Google Trends (for the time between a few days before George Floyd's death until several days after Derek Chauvin's sentence).

Based on their examination of #BlackLivesMatter associated with several other hashtags circulated in 2014, Ince et al. (Citation2017) submit that the hashtags cannot be algorithmically assessed for the pro- or counter-Black sentiments they express. This is all the more relevant to multimodal memetic data, which need to be carefully scrutinised. Thus, subjecting the corpus of memes to manual qualitative and quantitative analyses was the only way of deciphering the stance represented in the memes (cf. Dynel, Citation2021; Shifman, Citation2013; Wiggins, Citation2019) and their underlying pro- or anti- BLM ideologies. The automatically generated corpora were open-coded by both authors through a grounded-theory approach in an iterative process. All problematic cases were discussed so that agreement could be reached for each item. Several items (n = 26 and n = 34) were discarded from the corpora upon the first inspection, having no relevance to the topic of Black or blue lives (e.g., unrelated merchandise pictures). We thus arrived at the core corpora of BLM memes (n = 505) and BlueLM memes (n = 379), with several items (n = 32) occurring in both corpora, being indicative double-tagging and user-perceived significance for both movements (e.g., pro-BlueLM and, simultaneously, anti-BLM).

The data were examined through the lens of Multimodal Critical Discourse Analysis, which fits the study of ideologies in social discourse that encompasses not only verbal but also multimodal components, the combination of which makes for the totality of the communicated meaning (Machin, Citation2013; Machin & Mayr, Citation2012; see also van Leeuwen, Citation2004, Citation2009; Wang, Citation2014). The multimodal items were carefully dissected with reference to the relevant micro- and macro-levels of social structure (e.g., van Dijk, Citation1993). Similar to previous studies of political memes, besides the socio-political context (see Kjeldsen, Citation2000; cf. Milner, Citation2013, Citation2016), we took account of a wide range of intertextual allusions to previous artefacts (Kristeva, Citation1980 [Citation1967]; D’Angelo, Citation2009) and to historical, political and cultural facts (Ross & Rivers, Citation2018). All of these components, occurring in various clusters, contributed to the complex discourses of BLM and BlueLM memes and had to be examined jointly so that the specific ideological constructs and overarching ideologies could be fleshed out.

According to the research design, the memes in the two corpora were ultimately divided along two criteria. First, the presence/absence of humour was identified based on resolvable incongruity, the hallmark of all humour (see e.g., Martin & Ford, Citation2018), understood as a structural property of a meme that invites relevant cognitive operations (see Dynel, Citation2016). Second, the memes in each corpus were studied in the light of the stance on BLM and BlueLM, either positive or negative. Also, a third group of memes (bifurcating into two subtypes) was distinguished in each corpus, capturing the cases qualifying as neither pro- nor anti- movement. Further, within the four major pro- and anti-BLM and BlueLM categories, memetic trends were distilled depending on the specific ideological discourses and constructs. Rather than devising a coherent classificatory system that would comprehensively account for every item in each of the major categories (an impossible task given the diversity of the items), our objective was to identify the prevalent patterns in the datasets. Thus, several trends, that is ideological constructs and discourses, within pro-BLM and anti-BLM, as well as pro-BlueLM and anti-BlueLM, memes were teased out, each necessarily represented by at least seven items. Thereby, we arrived at the twelve prevailing trends summarised in .

Table 1. Summary of the main trends found in the two corpora of memes.

Analysis and findings

Quantitatively, the data yield interesting results. While a substantial number of memes in the BLM corpus (n = 505) are humorous (n = 204), the majority (n = 301) do not qualify as humour. As regards the ideological dimension, anti-BLM memes (n = 241) slightly outnumber the pro-BLM ones (n = 205). Among the anti-BLM group, there is some difference, but not too significant a difference, between humorous (n = 128) and non-humorous (n = 113) memes. Among the pro-BLM memes, non-humorous ones (n = 153) eclipse humorous ones (n = 52). The remainder of the corpus (n = 59) encompasses two subsets: memes (n = 29) that support neither of the opposing movements, trying to triangulate and rationalise or being factual and non-judgemental (see below), as well as memes (n = 30) that seem to be ideologically ambiguous, with their stance on BLM being crucial but impossible to establish. Two BLM memes in (3A and 3B) illustrate this last category of memes where the meme creators’ stance (and sometimes also the stance of the subjects presented in the pictures) cannot be unequivocally determined (see Dynel, Citation2021).

As regards 3A, there is no way of knowing whether the four subjects in the picture have painted their faces black with serious intent in support of BLM or with a jocular intent in order to laugh it off. Moreover, the image may have originated regardless of the movement, while it was only the meme author that imposed the ‘Black lives matter’ sign on a BLM-neutral photograph, with either intent (pro- or anti-BLM). On the other hand, 3B shows a smiling white woman walking through a shopping mall, with many Black people lying on the floor, presumably in an act of protest. The verbal component of the meme might be an utterance applied to the woman and/or a message that the meme creator wishes to convey. It is impossible to tell whether this is a sincere admission and the main thrust of the meme, or whether the meme creator takes a dissociative stance on the woman's (alleged) light-hearted attitude towards the Black people around her. Importantly, the stance that the subject shown in the meme (seems to) represent may be either endorsed or disparaged and even ridiculed by the meme author/poster, with this being the central stance and import of the meme (Dynel, Citation2021).

Among the BlueLM memes (n = 379), anti-BlueLM (n = 136) memes slightly outnumber pro-BlueLM memes (n = 110), whilst quite a few (n = 63) show epistemological ambiguity in terms of the stance taken on BlueLM (or BLM), and a few more (n = 70) take a meta-perspective on the Black–blue strife (Examples 3C and 3D) or are just ideologically neutral (Example 3E) without taking sides. Example 3C exhibits an explicit attempt at triangulation between the two competitive ideologies represented by the slogans. Similarly, Example 3D showcases the rationalising argument of an elderly Black citizen who questions the strife between the two movements and calls for mutual respect, albeit implicitly casting doubt on BLM premises (i.e., the presence of racism).Footnote9 Finally, 3E (a meme bearing both BLM and BlueLM tags) shows no ideological stance at all while commenting on the toll that Covid-19 (embodied by the tired SpongeBob SquarePants) must have taken on the protesters. Similar to BLM items, the majority of BlueLM memes are not humorous (n = 226), while much fewer (n = 153) display humorous potential. The presence/lack of humour does not show any marked distribution within the anti-BlueLM group (n = 74 humorous vs n = 58). However, non-humorous memes (n = 78) outnumber humorous ones (n = 32) within the pro-BlueLM category.

The memes presenting a positive/negative stance on BLM and BlueLM are in the majority, eclipsing the neutral memes, in accordance with our initial assumption, and their discourses and ideological constructs (conceptualised as memetic trends) need to be detailed in the qualitative analysis that follows. As the memes exemplifying the trends are briefly discussed, the lack of humour is taken by default and is not commented on, while the presence of the items' humorous potential is indicated.

Pro-BLM memes

A salient memetic trend endorsing BLM involves the circulation of supportive logos and slogans. As shows, this trend involves the central ‘Black Lives Matter’ slogan (4B and 4C) and many other ones, often explanatory (4C) or creative, such as the metaphorical slogan in 4A, where an abscess and infection to be drained represent racism and its pernicious ideology. This extremely widespread trend involves two main discourses: photographs of people, both white (4A) and Black (4C) holding signs, for instance at rallies (4A and 4C); as well as (less frequent) users’ digital artefacts (e.g., the drawn portrait of George Floyd in 4B). All of the slogans echo the basic BLM ideological premises and call attention to black citizens’ legal and civil rights, indicating the prevalence of racism and the systemic violence and oppression of Black people (cf. Carney, Citation2016). Some of the signs also elaborate on these premises, clarifying misunderstandings, as is the case with 4C, which addresses the rationale underlying the key slogan and refers to the Black vs All Lives Matter strife, which is the key topic of another prevailing trend.

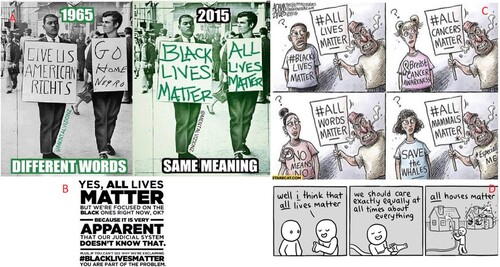

The seemingly universal ‘All Lives Matter’ motto, deployed as a counter to Black Lives Matter, purports to sound inoffensive but is racist, being indicative of indifference to racial disparities (Bock & Figueroa, Citation2018). This Liberal slogan (Bailey & Leonard, Citation2015) intimately communicates white supremacy and racial colour-blindness (Carney, Citation2016; Gallagher et al., Citation2018; Orbe, Citation2015), being a means of masking inequalities, and skirting the topics of racial injustice and unwarranted police violence against Black citizens (Langford & Speight, Citation2015). Most importantly in this context, All Lives Matter is used rhetorically to dismiss the legitimacy of the BLM movement and its core slogan, as also evidenced by a few memes in the corpus at hand, albeit too few to be distilled as an independent ideological trend within the anti-BLM dataset. All Lives Matter is sometimes employed strategically in tandem with Black Lives Matter to protest racism (Carney, Citation2016). In other words, as Gallagher et al. (Citation2018) put it, supporters of Black Lives Matter ‘hijack’ All Lives Matter to counter-protest it. This is essentially what Example 4C, as well as the four cases in make manifest.

In 5A, thanks to a multimodal juxtaposition of two manipulated images, a parallel is drawn between contemporary times and the ‘60s. This meme indicates systemic injustice with roots in history and racist undertones that the All Lives Matter slogan/ideology carries, being semantically empty otherwise. Likewise, systemic injustice of the judicial system is the focus of 5B, which – similar to Example 4C – also explicates the motivation behind the slogan. Moreover, the advocates of All Lives Matter dismiss the seriousness of racism and the need to prioritise Black over All, as also represented in the comic strip memes in 5C and 5D. Alluding to a selection of well-known slogans, the humorous meme in 5C exhibits the ‘All’ counter-logic in order to ridicule it and point to the ultimate self-serving purposes of the enraged objector, who consistently demands generalising slogans. Another humorous item, the metaphor-based comic strip in 5D presents a zealous supporter of equality ignoring a house burning as he is hosing down another house unaffected by the fire.

Another prevailing trend among the pro-BLM memes, exemplified in , concerns what can be broadly conceptualised as the superiority of police officers over Black citizens. This trend holds that law enforcement personnel routinely engage in unwarranted acts of violence (Clark et al., Citation2017; Pellow, Citation2016), as is considered to have been the case with George Floyd (cf. the riddle in 6A). Police are also thought to act unfairly, evincing a negative bias against Black citizens, which the humorous meme in 6B illustrates. This negative bias is also manifest in the supreme indifference that police have towards Black lives, as represented by the two-part meme based on images of police officers and a racist joke about death that qualifies as dark humour (Dynel & Poppi, Citation2018) and that two police officers in the second picture seem to be laughing at (6C).

Overall, the memes showing pro-BLM slogans (often contextualised in offline uses, such as signs displayed at rallies) promote the movement and its plea for equality and human rights. The BLM movement, as represented in the data at hand, does not show any ‘Black power’ ideology encompassing Afrocentrism, Black pride, Black separatism, Black supremacism, among others (see Collins, Citation2006; McCartney, Citation2010). While those are a mirror reflection of white racism, separatism and supremacism (McLaughlin, Citation2005), the BLM movement fights against structural racism and inequality. This also shows in the memes that present the ideological struggle against the ‘All Lives Matter’ slogan, which takes a generalising position to support the existing system of power (Mullaly, Citation1997). The memes at hand address two problems: the ‘denial of racism’ (van Dijk, Citation1992) and the promotion of strategical racial homogeneity and ‘victimism’ (Poppi et al., Citation2018), that is the tendency of oppressors to present themselves as victims of the injustices that affect the oppressed. As the memes indicate, one of the marked forms of injustice is the brutality, and more generally, the superiority that the police evince, especially towards Black citizens. This salient memetic theme is BLM supporters’ natural reaction to the events of 25th May 2020, similar to previous egregious acts of police violence that received extensive media coverage (Lawrence, Citation2000) and prompted social media responses (Clark et al., Citation2017; Dixon & Dundes, Citation2020). While the pro-BLM memes display great heterogeneity otherwise, the three ideological trends seem to monopolise this part of the memescape. The trends on the anti-BLM memescape are much more diversified.

Anti-BLM memes

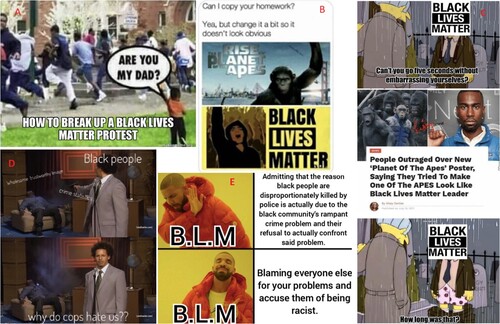

The dominant anti-BLM trend concerns the deprecation of Black citizens, and it can be divided into two major subtypes: shaming and questioning BLM logic, which may intertwine (see the humorous memes in ).Footnote10 The shaming trend is based on the attribution to Black people, especially males (see Smiley & Fakunle, Citation2016), pejorative features such as rowdiness, propensity for casual sex and escaping from parental responsibility (7A). Similarly, alluding to pupils’ adage about copying homework from one another, the demeaning meme in 7B shows one BLM logo as a modified version of the poster advertising the new film about apes’ uprising. The human and animal leaders are thus subject to comparison, which concerns something more than each holding up one arm in a rebellious act. In these and many other memes, Black citizens are presented as being uncouth and capable of violent behaviour, involving both verbal and physical aggression.

In a related trend, Black people's logic and rational thinking are also questioned, as in 7C, where the title of a newspaper article with accompanying pictures is sandwiched between two screenshots from The Simpsons. The latter act as a critical commentary on the reported recognition of the alleged similarity between a BLM leader and an ape, an idea that the meme author frowns upon, thus pouring scorn on the BLM poponents whose claim is considered to backfire.

In a very productive trend, users criticise and undermine BLM logic by pointing out what they consider its contradictions, hypocrisy and double standards, as shown in 7D and 7E, which utilise meme templates to bring out the relevant juxtapositions. Using the ‘Who killed Hannibal’ template to exhibit extreme audacity,Footnote11 7D points out that Black citizens should not be surprised at police's attitude to them if they kill law-abiding citizens. Similarly, based on the no – yes template, 7E addresses the ‘rampant crime problem’ that BLM denies only to do external attribution and make racism accusations.

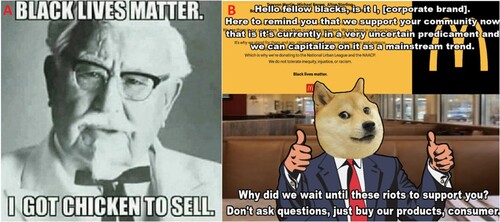

The criticism of a contradiction within BLM ideology can also be sought in a most peculiar trend targeting capitalism (see the humorous items in ). While it is the brands that are the main target of the criticism for pandering to Black citizens to boost profit, the memes may be considered to implicitly display an anti-BLM orientation: although BLM is a leftist movement, it is shown to receive support from capitalist enterprises, whether or not willingly. Meme 8A features Colonel Harland David Sanders, the founder of Kentucky Fried Chicken, voicing the BLM slogan only to immediately advertise his product. In 8B, with McDonald's BLM supportive poster in the background and its generic ‘doge’Footnote12-faced representative, the meme verbalises the economic motivation that various corporations are held to be driven by as they show their support to the BLM movement. Therefore, indirectly, through criticising the capitalistic support, memes like these may be seen as trying to dismantle BLM integrity.

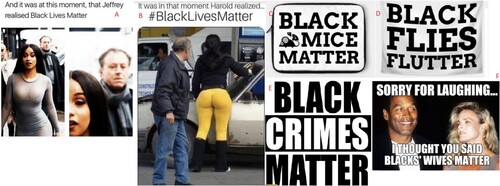

Another major memetic trend can be captured under the umbrella term ‘trivialisation’. It encompasses several discourses, most notably, sexualisation, autotelic wordplay (i.e., wordplay for its own sake) and meaningful wordplay, all of which show inherent humour, given their formal properties (see ). The sexualisation trend features white men ogling buxom Black women, whether celebrities (such as Cardi B, an American rapper, songwriter, and actress, in a translucent bodycon designer dress in 9A) or anonymous women, such as the one in 9B dressed in tight leggings, with the captions suggesting that the men (bearing random names) have realised the importance of BLM thanks to the women's robustness. Regardless of the sexist connotations or the implicit praise of the women's attractive looks (see Dynel & Poppi, Citation2020b; Poppi & Dynel, Citation2021), these humorous memes seem to undermine the importance of the political movement.

By the same token, the various wordplay-based distortions of the BLM slogan, such as those in 9C and 9D, appear to convey no relevant propositional meaning but do make light of the movement, dismissing its significance and the ideological load of the motto. However, some other distortions, such as that in 9E, do carry pertinent ideological import and cannot possibly be defended as being shared ‘just for fun’. The same concerns 9F, which features the former professional American football player O.J. Simpson and his ex-wife, whom he is known to have murdered. Thus, apart from discrediting BLM, these two wordplay-based memes bring up the issue of the (alleged) racially motivated violence and law-breaking propensities of Black people.

It is time to take stock. Firstly, many of the anti-BLM memes in the corpus attribute to Black people various negative features and behaviours through what may be regarded as victim blaming (Chagnon, Citation2017). On the one hand, some memes bring to focus well-entrenched stereotypes of Black people as inherently violent and criminogenic (see Quillian & Pager, Citation2001) and sometimes spread dehumanisation ideology (Haslam, Citation2006), with Black people being conceived as less human and more animal-like. On the other hand, other memes propel new stereotypes consequent upon the BLM movement's rhetoric, such as blame-calling that serves Black people's goals. Secondly, the capitalist support examples constitute an attempt to undermine the BLM movement and the claims to victimhood by pointing to the support Black people receive from capital brands representing the injustice and oppression of the society. The depicted BLM's collusion with capitalistic values – implicitly considered an expression of an antagonistic society (see Pollock, Citation1989) – serves to dismantle the idea that BLM promotes equality, social justice, human rights and freedom. Thirdly, the memes that trivialise the BLM movement through sexualisation and wordplay, whether or not meaningless, are a straightforward way of showing contempt for the movement and its cause. Even if seemingly acknowledging the attractiveness of Black women, memetic sexualisation may be taken to carry negative connotations, aggravating the condition of Black women's inferiority (see Mowatt et al., Citation2013). This is because this sexualisation involves hypersexuality (Miller-Young, Citation2010), often indicating the stereotyped size-related peculiarity (Newton et al., Citation2012). Additionally, the hitherto ignored Black women earn their presence only through this sudden bodily ‘hypervisibility’ (Harris-Perry, Citation2011), which is actually a means of disparagement.

Pro-BlueLM memes

signposts a marked pro-BlueLM memetic trend concerning police officers, both Black and white, who have lost their lives on duty (cf. Bock & Figueroa, Citation2018). Police officers, such as the two women, one white (10A) and one Black (10B), are pictured as professionals and kind humans. A sub-trend within this category addresses Black police officers whose deaths do not appear to have caused any outcry from BLM supporters, thus indicating their hypocrisy (10C and 10D). Additionally, the unnoticed deaths of Black law-enforcing personnel are sometimes contrasted with those of Black perpetrators, whose demise does generate strong responses from the Black community.

The endorsement of BlueLM also concerns police officers’ law-enforcement duties that serve and protect law-abiding citizens, as well as the respect that police deserve as humans and professionals. This is a broad trend that involves various discourses exemplified in .

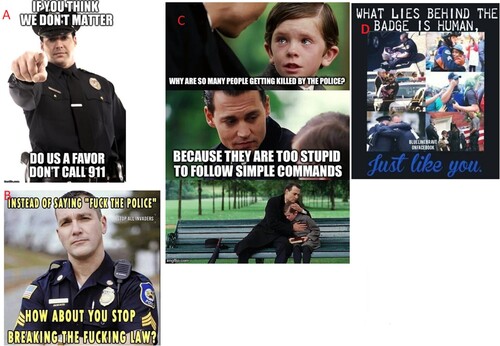

This prevalent memetic trend legitimising BlueLM involves a marked humorous subtrend featuring images of police officers, with witty verbal components representing their stance and challenging, for example, the common critical presumption (11A) or the clichéd pejorative expression (11B). Similar to supporters on the Blue Matters Facebook page (Bock & Figueroa, Citation2018), pro-BlueLM meme authors espouse support for legitimate use of violence and attribute the guilt for the deaths at the hands of police to the deceased themselves, albeit not denying them sympathy, as is the case with 11C, a humorous meme based on a template involving three stills from Finding Neverland. Also, in another notable type of discourse, users recognise police officers’ sensitive human nature and humane gestures towards citizens (11D).

The third prevalent pro-BlueLM trend, similar to the pro-BLM counterpart (cf. ), involves the promotion and reiteration of the BlueLM American flag (12 A) and the central slogan (12B) with a view to showing and garnering support for the movement. Both memes in present explicit calls to action, whether generic or more specific (cf. the suggestion to cannily introduce oneself as ‘Blue Lives Matter’ at a self-service coffeehouse chain).

To summarise, pro-BlueLM memes depict police officers in idealised terms as heroes, commendable professionals and model citizens (see Solomon et al., Citation2021), at times emphasising the primary dichotomy between the good (the police) and the bad (Black offenders) (cf. Augoustinos & Every, Citation2007). The promotion of BlueLM symbols and slogans, typically in digitally constructed images, alludes to the long-standing American ethos of the police's untrammelled power and authority necessary to curb ‘arrogant autonomy’ (Shanahan & Wall, Citation2021). This ethos legitimises police interventions in the spirit of legalism, i.e., unquestioned dutiful rule-following (Shklar, Citation1986), as many memes show.

Anti-BlueLM memes

Many of the memes comprising the Anti-BlueLM subcorpus align with those in the pro-BLM subcorpus. This is the case with a trend concerning police's superiority (cf. ), which illustrates, the focus here being on their ruthlessness.

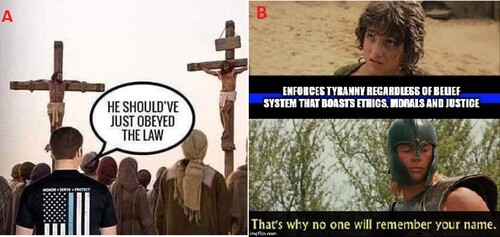

Meme 13A dissociatively echoes (Dynel, Citation2020) BlueLM extreme ideological beliefs about punishment through a hyperbolic presentation of a BlueLM advocate (with a BlueLM flag on his t-shirt) accusing Jesus himself of having disobeyed the law and being responsible for his fate. Similarly, 13B deploys the ‘That's why no one will remember your name’ meme templateFootnote13 to metaphorically symbolise the police's tyrant power over the lowly, who espouse the ideology based on ethics, morals and justice.

Another trend found in the BlueLM corpus is similar to the All Lives Matter trend distinguished in the pro-BLM subcorpus (cf. ). Here, it is the BlueLM motto that is echoed and hijacked only to be argued against and undermined ().

Meme 14A quotes the three ‘lives matter’ slogans presented in the symbolic colours, where the ‘all’ and ‘blue’ are presented as being compatible, in order to indicate the generic anti-Black bias in the strife. Meme 14B questions the blue lives phenomenon, and thus the need for the BlueLM movement, explaining the rationale behind BLM, which BlueLM does not have: the latter is not a response to oppression to which a person is subjected based on their innate characteristic.

Another trend () is a counterpart of an anti-BLM trend that humorously trivialises the importance of the movement at hand (cf. ). This trend encompasses memes that play with the movement's slogan in a light-hearted manner, without any direct ideological meanings arising from the memes. This is done either through images of various fictional blue characters, such as Sesame Street's Cookie Monster as he is munching on a cookie (15A) or through various forms of verbal and visual play, as is the case with the Photoshopped police-officer cat in 15B.

In general terms, at the core of Anti-BlueLM memes, there is the claim that the police's superiority ideologically misrepresents the notions of law and morality. These memes question the need for legalism (Shklar, Citation1986) and ‘adversarial legalism’ (see Cross & Kagan, Citation2003; Epp, Citation2003), which calls for harsh punishment for offenders. Users suggest that the premise underlying the expression ‘law and order’ is futile without the application of moral principles that sustain equality among citizens and safeguard the fairness of punishment. Additionally, dismantling the ‘Blue Lives Matter’ slogan, other memes question the need for the movement, which is seen merely as a rejoinder to the Black Lives Matter movement (see Lynch, Citation2018). In this vein, the ‘Blue Lives Matter’ slogan and movement are sometimes made light of and disparaged through trivialising memes devoid of any deeper meanings.

Discussion and conclusions

This study has led to several interesting conclusions about the BLM and BlueLM memescape. The larger size of the BLM corpus in comparison with the BlueLM corpus indicates that BLM seems to have generated more interest among meme creators, at least at the time of data collection based on the Python script applied. This aligns with the result of the comparison of the two Google Trends, with BLM showing much more popularity than BlueLM as a search term (see ). This is not meant to suggest, however, that BLM has more (meme-creating) supporters than the countermovement. Within each corpus, items manifesting a negative stance on the tagged movement outnumber those presenting a positive stance, with neutral-stance and ambiguous-stance memes being the least frequent. This may be taken to suggest that memes are primarily a means of voicing political criticism, rather than political endorsement, which aligns with and explains the plethora of papers on memes as vehicles for dissent and negative evaluations of the political arena (e.g., Huntington, Citation2016; Milner, Citation2013, Citation2016; Ross & Rivers, Citation2018; Wiggins, Citation2019).

Counter to the widespread presumption that memes are a category of humour, reflected by a plethora of studies, the majority of memes in the corpus based on user tags do not show the basic property of humour, i.e., any resolvable incongruity. This proves that users do not inherently associate memes with humour, which is in line with the original conceptualisation of the Internet meme as any cultural unit altered thanks to human creativity.Footnote14 Additionally, within the pro-BLM and pro-BlueLM categories, non-humorous memes dominate over humorous ones, while more humour is present among the anti-BLM and pro-BLM categories, but it does not dominate there either. This points to two important conclusions. First, the inherently serious political topics of BLM and BlueLM, related to human rights and human life, do not immediately promote humour as users make their memetic contributions to the polyvocal discussion (Milner, Citation2013; Ross & Rivers, Citation2017, Citation2018) on social media. Second, the presence of humour in the negative-stance memes testifies to the disparagement of a target being a concomitant of political humour (see e.g., Dynel, Citation2020);Footnote15 even though not all humour has a target of whom to make fun, the presence of the target makes for mirthful experience and boosts the funniness effect (Martin & Ford, Citation2018). It also seems that having the target of genuine, non-humorous criticism facilitates humour production, and the humour may be most appreciated by those sharing the same ideological standpoint. Empathy for the target may block humour appreciation, especially if it involves racist or dark humour (Dynel & Poppi, Citation2018).

Overall, by design, the two movements, Black Lives Matter and Blue Lives Matter, are in a relationship of ideological opposition. In many memes, these pro- and anti- stances do mesh or may only be implicit/tacit. However, this does not mean that all anti-BlueLM memes must necessarily be pro-BLM (but this seems to be a frequent pattern indeed), let alone that anti-BLM memes communicate a pro-BlueLM stance. Nor is it the case that pro-BLM or pro-BlueLM memes must simultaneously implicate a negative stance on the other movement.

While the memescape is very much diversified within both BLM and BlueLM, the anti-BLM memes, constituting the most amply represented category in the entire dataset, show the greatest number of consistent trends, which proves users’ productivity and well-entrenched negative beliefs about Black people. Additionally, this seems to be consonant with the findings of Bock and Figueroa (Citation2018), who report that the BLM Facebook has more negative comments from BlueLM advocates than BLM supporters post on BlueLM Facebook. This may also indicate that, unlike its critics, BLM supporters prefer to fight for their cause rather than attack the countermovement, for instance through producing anti-BlueLM memes.

Taken together, anti-BLM memes evince tacit white supremacy ideology (Daniels, Citation2016), sometimes reflected in the colour-blind All Lives Matter argument (Carney, Citation2016; Gallagher et al., Citation2018; Orbe, Citation2015). They also point to the users’ little positive disposition towards Black people and significant attribution of blame for the recognised inequality to the Black themselves rather than discrimination (Bobo et al., Citation2012), with Black males being often pictured as ‘thugs’ capable of criminal acts (see Smiley & Fakunle, Citation2016). All this is done to question the need for the BLM movement, puncture its underlying rationale, and even ridicule it (cf. Bailey & Leonard, Citation2015). Specifically, the anti-BLM ideological constructs and discourses detected in the corpus range from deprecation through shaming (attribution of pejorative features) to accusations of questionable logic, which is claimed to entail contradictions, hypocrisy and double standards, including capitalist support. Yet another trend is trivialisation through sexualisation or wordplay, which may be meaningless or communicate some anti-Black content. Except for this last category, trivialisation memes, enclosed within a humorous frame and bearing the tacit Batesonian ‘this is play’ metamessage (see Dynel, Citation2017, Citation2018; Dynel & Poppi, Citation2020b and references therein), may not do serious political critique, evincing a playful and seemingly innocuous approach to the movement. Nevertheless, given that the memes are not restricted to one humour-oriented interactional space and do make light of the serious political movement, they should be interpreted as exhibiting an anti-BLM stance.

Trivialisation, albeit showing in other discourses (blue characters and multimodal play), is also one of the trends in the anti-BlueLM subcorpus, carrying similar effects. The anti-BlueLM category, the smallest one, also encompasses memes dismantling the rationale behind the movement's slogan, as well as police's superiority. This last trend can be found in the pro-BLM subcorpus as well. Overall, the superiority trend criticises police officers’ ruthlessness, brutality, abuse of power and anti-Black bias (see Clark et al., Citation2017). Pro-BLM memes also feature items dismantling the colour-blind/racist All Lives Matter ideology (see also Carney, Citation2016; Gallagher et al., Citation2018), as well as items reiterating pro-BLM slogans. A similar slogan reiteration trend can be observed in the pro-BlueLM corpus. What prevails in the pro-BLM slogan trend is pictures of individuals at rallies exhibiting their support, even though digital subject-less items showing logos and slogans, typical of the BlueLM trend, can be found too. This difference between pro-BLM and pro-BlueLM slogan-based memes is a natural consequence of the numerous rallies and demonstrations, where BLM advocates show their support. Some of this personal endorsement duly travels online to reach broader audiences, being perhaps more appealing than impersonal digital items. Additionally, rather than repetition of the core slogan in various visual forms typical of the pro-BlueLM subcorpus, the pro-BLM subcorpus includes various slogans or elaborations of the primary one so that the ideological premises for the movement are expounded on. Taken as a whole, the pro-BLM memes picture Black people as law-abiding citizens rationally pursuing equality and indicate that anti-Black bias may be recognised in the policy-making system in the USA, making for economic, educational and public health inequalities (Pellow, Citation2016).

Besides the pro-BlueLM slogans, the pro-BlueLM subcorpus also includes the fallen police officers’ trend, which sometimes simultaneously admonishes BLM double standards and Black-on-Black crime (see Bailey & Leonard, Citation2015). However, as Smiley and Fakunle (Citation2016) report, unarmed Black male victims tend to be criminalised posthumously whilst being merely unarmed victims of law enforcement. All this conforms to the stereotype of Black men as rowdy thugs, so deeply entrenched in the (online) community that it subconsciously normalises and legitimises any law-enforcement activities, including violence (Carney, Citation2016). In this vein, the prevailing and diversified pro-BlueLM trend expresses endorsement of police officers as empathetic and empathy-deserving human beings and, more importantly, sentinels maintaining peace and order and legitimate law-enforcers entitled to use any measures thanks to the power vested in them. This trend tacitly sanctions hierarchal, authoritarian principles (Bock & Figueroa, Citation2018).

It may be thought that the slogan (and hashtag) BlackLivesMatter that came into being in 2013 may promote pro-Black online activism, raising people's awareness of racism and unifying them around a common cause, similar to other politically loaded slogans and hashtags (see Zulli, Citation2020), extending the movement's reach and bolstering its influence (Mundt et al., Citation2018) both online and offline. There have been claims that social media users can promote the BLM movement and help it expand (Ince et al., Citation2017; Mundt et al., Citation2018), allowing stifled Black voices to be heard and – in the long run – induce policy changes (Carney, Citation2016). Similar optimistic views have been expressed about memes fostering various political movements (see Dynel & Poppi, Citation2020a; Milner, Citation2013).

However, Mundt et al. (Citation2018, p. 10) doubt that social media can ‘build and/or sustain movements for social change’, which makes pro-BLM memes unlikely harbingers of social change. This is, among other things, because participatory networked culture does not mean social equality, with people being restricted by knowledge and limited access to social media (Jenkins, Citation2014). Consequently, some Black voices may never come to the fore in online spaces (Miller et al., Citation2021; Zulli, Citation2020). This aligns with the current findings about the BLM memescape, since pro-BLM memetic activity seems to be eclipsed quantitatively by anti-BLM memes, which may sometimes take the form of ‘platformed racism’ (Matamoros-Fernández, Citation2017). This racism may even escalate on social media, given that restraint against the expression of racist views is not observed in online contexts (e.g., Jakubowicz, Citation2017), and the same can be said about memes (the most virulent examples avoided in this paper). While this study does not indicate this clearly, being based on corpora of randomised data, research of BlueLM and BLM memes culled from specific platforms would, presumably, indicate that on social media users tend to interact within pre-selected nodes. This is where their original divergent views become more entrenched (KhosraviNik & Unger, Citation2015), as they interact with like-minded people to support either the Black or the Blue Lives Matter movements, typically pre-conditioned by several social variables, notably their race (cf. Dixon & Dundes, Citation2020).

Acknowledgement

The Authors would like to thank Gosia Krawentek for her assistance in the process of corpus data collection and her advice on methodology (in accordance with her duties in the Sonata Bis project 2018/30/E/HS2/00644).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Marta Dynel

Marta Dynel is Associate Professor in the Department of Pragmatics at the University of Łódź and part-time Chief Research Fellow in the Department of Creative Communication at Vilnius Gediminas Technical University. Her research interests are primarily in humour studies, im/politeness, the pragmatics of film discourse and social media, and the philosophy of irony and deception. She is the author of 2 monographs, over 110 journal papers and book chapters, as well as 15 (co)edited volumes and special issues. She is Editor-in-Chief of Lingua. [email: [email protected]]

Fabio I. M. Poppi

Fabio I. M. Poppi obtained his PhD in Linguistics from the University of East Anglia (UK). He is Research Associate at the University of Łódź (Poland) and Associate Professor at Sechenov Moscow University (Russia). His research interests include multimodality, critical approaches to language, ideology and social cognition, all with reference to film, art, and social media discourse. He has published extensively on these topics in international journals. [email: [email protected]]

Notes

6 Vickery (Citation2014) submits that the sad-looking bear template inspired a non-humorous meme cycle based on people's serious personal revelations. However, there may be an epistemological error involved in (part of) her analysis, stemming from the assumption that the meme authors have shared their genuine problems, which may not have been the case; rather, at least some of the memes may have been submitted as cases of dark humour (see Dynel & Poppi, Citation2018), whether or not making truthful admissions. Some of the examples are nothing but absurd and overtly untruthful (Dynel, Citation2018) and/or evince humorous potential in the way the alleged confessions are structured, finishing with incongruous, surprising punchlines (Dynel, Citation2016), as in ‘7 years ago my father was diagnosed with Alzheimer's. We convinced him not to kill himself. I wish we hadn't’. Even if this text is partly truthful (e.g., the meme creator had a father suffering from Alzheimer's), it is very likely to have been submitted with a humorous intent, given the deliberate surprise effect in the closing statement (cf. the evidently non-humorous ‘I wish we hadn't convinced him not to kill himself’).

7 Williams (Citation2020) presents what she calls ‘Black memes’ based on the stigmatised Becky and Karen categories as critique of white surveillance and casual racial dominance. She concludes that these ‘Black memes’ help fight against racial injustice. However, it needs to be pointed out that the memes discussed by Williams (Citation2020) are primarily orientated towards genuine disparagement (see Dynel, Citation2020) of the two female stereotypes, while the Black issues are not at stake, let alone being endorsed, in each and every case (e.g., one meme showing Barack Obama sitting at his presidential desk as the nosey Karen is lingering outside his window).

8 Yoon (Citation2016) lists a few trends that seem to endorse racism (e.g., stereotyping and othering, as well as denial of racism) based on what seems to be a cherry-picked sample of 85 memes (from among 7762 memes labelled ‘that's racist’) that the author selected based on their relevance to the topic and popularity. These findings give a rather limited and biased picture of what the racist memescape involves.

10 It needs to be emphasised that humour does not necessarily entail funniness, which is a gradable property of humorous items subject to personal evaluation and is dependent on many psychological variables (see e.g., Martin & Ford, Citation2018). This is especially important in the case of racist humour, which may be considered offensive rather than amusing.

11 This template comes from Eric Andre's late-night show. In one sketch, the host suddenly pulls out a gun, fires a number of shots into his co-host Hannibal Buress only to turn deadpan into the camera and ask naively, ‘Who killed Hannibal?’.

13 It consists of two stills and a quotation from Troy, where Achilles (Brad Pitt) looks down (both literally and metaphorically) on the messenger.

15 It should be noted that also positive-stance memes may easily involve disparagement of a target of some kind.

References

- Augoustinos, M., & Every, D. (2007). The language of “race” and prejudice: A discourse of denial, reason, and liberal-practical politics. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 26(2), 123–141. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927X07300075

- Bailey, J., & Leonard, D. J. (2015). Black Lives Matter: Post-nihilistic freedom dreams. Journal of Contemporary Rhetoric, 5(3/4), 67–77.

- Bobo, L. D., Charles, C. Z., & Krysan, M. (2012). The real record on racial attitudes. In P. V. Marden (Ed.), Social trends in American life: Findings from the general social survey since 1972 (pp. 38–83). Princeton University Press.

- Bock, M. A., & Figueroa, E. J. (2018). Faith and reason: An analysis of the homologies of Black and Blue Lives Facebook pages. New Media & Society, 20(9), 3097–3118. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444817740822

- Carney, N. (2016). All lives matter, but so does race: Black lives matter and the evolving role of social media. Humanity & Society, 40(2), 180–199. https://doi.org/10.1177/0160597616643868

- Chagnon, N. J. (2017). Racialized culpability: Victim blaming and state violence. Race, Ethnicity and Law, 22, 199–219. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1521-613620170000022016

- Charteris-Black, J. (2011). Politicians and rhetoric: The persuasive power of metaphor (2nd ed.). Palgrave MacMillan.

- Clark, M. D., Bland, D., & Livingston, J. A. (2017). Lessons from #McKinney: Social media and the interactive construction of police brutality. The Journal of Social Media in Society, 6(1), 284–313.

- Collins, P. H. (2006). From Black power to hip hop: Racism, nationalism, and feminism. Temple University Press.

- Cross, F. B., & Kagan, R. A. (2003). America the adversarial. Virginia Law Review, 89(1), 189–237. https://doi.org/10.2307/3202389

- D’Angelo, F. J. (2009). The rhetoric of intertextuality. Rhetoric Review, 29(1), 31–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/07350190903415172

- Daniels, J. (2016). White lies: Race, class, gender and sexuality in white supremacist discourse. Routledge.

- Dixon, P. J., & Dundes, L. (2020). Exceptional injustice: Facebook as a reflection of race-and gender-based narratives following the death of George floyd. Social Sciences, 9(12), 231. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9120231

- Dynel, M. (2016). “I has seen Image Macros!” Advice animals memes as visual-verbal jokes. International Journal of Communication, 10, 660–688.

- Dynel, M. (2017). But seriously: On conversational humour and (un)truthfulness. Lingua. International Review of General Linguistics, 197, 83–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2017.05.004

- Dynel, M. (2018). Irony, deception and humour: Seeking the truth about overt and covert untruthfulness. Mouton de Gruyter.

- Dynel, M. (2020). Vigilante disparaging humour at r/IncelTears: Humour as critique of incel ideology. Language & Communication, 74, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langcom.2020.05.001

- Dynel, M. (2021). COVID-19 memes going viral: On the multiple multimodal voices behind face masks. Discourse & Society, 32(2), 175–195. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926520970385

- Dynel, M., & Poppi, F. I. M. (2018). In tragoedia risus: Analysis of dark humour in post-terrorist attack discourse. Discourse & Communication, 12(4), 382–400. https://doi.org/10.1177/1750481318757777

- Dynel, M., & Poppi, F. I. M. (2020a). Caveat emptor: Boycott through digital humour on the wave of the 2019 Hong Kong protests. Information, Communication & Society, 1–19, Epub ahead of print 6 May 2020. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118x.2020.1757134

- Dynel, M., & Poppi, F. I. M. (2020b). Quid rides?: Targets and referents of RoastMe insults. HUMOR: International Journal of Humour Research, 33(4), 535–562. https://doi.org/10.1515/humor-2019-0070

- Epp, C. R. (2003). The judge over your shoulder: Is adversarial legalism exceptionally American? Law & Social Inquiry, 28(3), 743–770. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-4469.2003.tb00214.x

- Frazer, R., & Carlson, B. (2017). Indigenous memes and the invention of a people. Social Media + Society, 3(4), 205630511773899. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305117738993

- Gallagher, R. J., Reagan, A. J., Danforth, C. M., Dodds, P. S., & Moreno, Y. (2018). Divergent discourse between protests and counter-protests: #BlackLivesMatter and #AllLivesMatter. PLoS ONE, 13(4), e0195644. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0195644

- Harris-Perry, M. (2011). Sister citizen: Shame, stereotypes, and black women in America. Yale University Press.

- Haslam, N. (2006). Dehumanization: An integrative review. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 10(3), 252–264. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr1003_4

- Huntington, H. E. (2016). Pepper spray cop and the American dream: Using synecdoche and metaphor to unlock internet memes’ visual political rhetoric. Communication Studies, 67(1), 77–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/10510974.2015.1087414

- Ince, J., Rojas, F., & Davis, C. A. (2017). The social media response to Black Lives Matter: How Twitter users interact with Black Lives Matter through hashtag use. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 40(11), 1814–1830. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2017.1334931

- Jakubowicz, A. (2017). Alt_Right white lite: Trolling, hate speech and cyber racism on social media. Cosmopolitan Civil Societies: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 9(3), 41–60. https://doi.org/10.3316/informit.309784538174296

- Jenkins, H. (2014). Rethinking ‘rethinking convergence/culture’. Cultural Studies, 28(2), 267–297. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502386.2013.801579

- Jones, L. K. (2020). #Blacklivesmatter: An analysis of the movement as social drama. Humanity & Society, 44(1), 92–110. https://doi.org/10.1177/0160597619832049

- Khosravinik, M. (2017). Social media critical discourse studies (SM-CDS). In J. Flowerdew & J. Richardson (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of critical discourse analysis (pp. 582–596). Routledge.

- KhosraviNik, M., & Unger, J. W. (2015). Critical discourse studies and social media: Power, resistance and critique in changing media ecologies. In R. Wodak & M. Meyerc (Eds.), Methods of critical discourse studies (pp. 205–233). SAGE Publications.

- Kjeldsen, J. E. (2000). What the metaphor could not tell us about the prime minister’s bicycle helmet: Rhetorical criticism of visual political rhetoric. NORDICOM Review, 21(2), 305–327. https://doi.org/10.1515/nor-2017-0387

- Kristeva, J. (1980 [1967]). Word, dialogue, and novel. In L. Roudiez (Ed.), Desire in language: A semiotic approach to literature and art (trans. T. Gora, A. Jardine & L. Roudiz) (pp. 64–91). Columbia University Press.

- Langford, C. L., & Speight, M. (2015). #Blacklivesmatter: Epistemic positioning, challenges, and possibilities. Journal of Contemporary Rhetoric, 5(3/4), 78–89.

- Lawrence, R. (2000). The politics of force: Media and the construction of police brutality. University of California Press.

- Lynch, C. G. (2018). Don’t let them kill you on some dirty roadway: Survival, entitled violence, and the culture of modern American policing. Contemporary Justice Review, 21(1), 33–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/10282580.2018.1415045

- Machin, D. (2013). What is multimodal critical discourse studies? Critical Discourse Studies, 10(4), 347–355. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405904.2013.813770

- Machin, D., & Mayr, A. (2012). How to do critical discourse analysis: A multimodal introduction. SAGE.

- Martin, R., & Ford, T. (2018). The psychology of humour. An integrative approach. Elsevier.

- Matamoros-Fernández, A. (2017). Platformed racism: The mediation and circulation of an Australian race-based controversy on Twitter, Facebook and YouTube. Information, Communication & Society, 20(6), 930–946. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2017.1293130

- McCartney, J. (2010). Black power ideologies: An essay in African American political thought. Temple University Press.

- McLaughlin, E. (2005). Recovering blackness – repudiating whiteness: The Daily Mail’s construction of the five white suspects accused of the racist murder of Stephen Lawrence. In K. Murji & J. Solomos (Eds.), Racialization: Studies in theory and practice (pp. 163–184). Oxford University Press.

- Miller, G. H., Marquez-Velarde, G., Williams, A. A., & Keith, V. M. (2021). Discrimination and Black social media use: Sites of oppression and expression. Sociology of Race and Ethnicity, 7(2), 247–263. https://doi.org/10.1177/2332649220948179

- Miller-Young, M. (2010). Putting hypersexuality to work: Black women and illicit eroticism in pornography. Sexualities, 13(2), 219–235. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460709359229

- Milner, R. M. (2013). Pop polyvocality: Internet memes, public participation, and the Occupy Wall street movement. International Journal of Communication, 7, 2357–2390.

- Milner, R. M. (2016). The world made meme: Public conversations and participatory media. MIT Press.

- Mowatt, R. A., French, B. H., & Malebranche, D. A. (2013). Black/female/body hypervisibility and invisibility: A Black feminist augmentation of feminist leisure research. Journal of Leisure Research, 45(5), 644–660. https://doi.org/10.18666/jlr-2013-v45-i5-4367

- Mullaly, R. (1997). Structural social work: Ideology, theory, and practice. Oxford University Press.

- Mundt, M., Ross, K., & Burnett, C. M. (2018). Scaling social movements through social media: The case of Black Lives Matter. Social Media + Society, 4(4). https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305118807911

- Newton, Z., Guo, L., Yang, H., & Malkin, M. (2012). Physical activity and perception of body image of African American women. LARNet: The Cyber Journal of Applied Leisure and Recreation Research, 15(1), 1–12.

- Orbe, M. (2015). # AllLivesMatter as post-racial rhetorical strategy. Journal of Contemporary Rhetoric, 5(3/4), 90–98.

- Pellow, D. N. (2016). Toward a critical environmental justice studies: Black Lives Matter as an environmental justice challenge. Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race, 13(2), 221–236. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742058X1600014X

- Pollock, F. F. (1989). State capitalism: Its possibilities and limitations. In S. E. Bronner, & D. M. Keller (Eds.), Critical theory and society. A reader (pp. 95–118). Routledge.

- Poppi, F. I. M., & Dynel, M. (2021). Ad libidinem: Forms of female sexualisation in RoastMe humour. Sexualities, 24(3), 431–455. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460720931338

- Poppi, F. I. M., Travaglino, G. A., & Di Piazza, S. (2018). Talis pater, talis filius: The role of discursive strategies, thematic narratives and ideology in Cosa Nostra. Critical Discourse Studies, 15(5), 540–560. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405904.2018.1477685

- Quillian, L., & Pager, D. (2001). Black neighbors, higher crime? The role of racial stereotypes in evaluations of neighborhood crime. American Journal of Sociology, 107(3), 717–767. https://doi.org/10.1086/338938

- Ray, R., Brown, M., Fraistat, N., & Summers, E. (2017). Ferguson and the death of Michael Brown on Twitter: # BlackLivesMatter, # TCOT, and the evolution of collective identities. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 40(11), 1797–1813. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2017.1335422

- Ross, A. S., & Rivers, D. J. (2017). Digital cultures of political participation: Internet memes and the discursive delegitimization of the 2016 U.S Presidential candidates. Discourse, Context & Media, 16, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcm.2017.01.001

- Ross, A. S., & Rivers, D. J. (2018). Internet memes as polyvocal political participation. In D. Schill & J. A. Hendricks (Eds.), The presidency and social media: Discourse, disruption and digital democracy in the 2016 Presidential election (pp. 285–308). Routledge.

- Shanahan, J., & Wall, T. (2021). ‘Fight the reds, support the blue’: Blue lives matter and the US counter-subversive tradition. Race and Class, 63(1), 70–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/03063968211010998

- Shifman, L. (2013). Memes in digital culture. MIT Press.

- Shklar, J. N. (1986). Legalism: Law, morals, and political trials. Harvard University Press.

- Smiley, C. J., & Fakunle, D. (2016). From “brute” to “thug”: The demonization and criminalization of unarmed Black male victims in America. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 26(3-4), 350–366. https://doi.org/10.1080/10911359.2015.1129256

- Solomon, J., Kaplan, D., & Hancock, L. E. (2021). Expressions of American white ethnonationalism in support for “Blue Lives Matter”. Geopolitics, 26(3), 946–966. https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2019.1642876

- van Dijk, T. A. (1992). Discourse and the denial of racism. Discourse & Society, 3(1), 87–118. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926592003001005

- van Dijk, T. A. (1993). Principles of critical discourse analysis. Discourse & Society, 4(2), 249–283. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926593004002006

- van Dijk, T. A. (1998). Ideology. SAGE.

- van Leeuwen, T. (2004). Ten reasons why linguists should pay attention to visual communication. In P. LeVine & R. Scollon (Eds.), Discourse and technology: Multimodal discourse analysis (pp. 7–20). Georgetown University Press.

- van Leeuwen, T. (2009). Discourse as the recontextualization of social practice: A guide. In R. Wodak & M. Meyer (Eds.), Methods of critical discourse analysis (2nd ed., pp. 144–161). SAGE.

- Vickery, J. R. (2014). The curious case of confession bear: The reappropriation of online macro-image memes. Information, Communication & Society, 17(3), 301–325. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2013.871056

- Wang, J. (2014). Criticising images: Critical discourse analysis of visual semiosis in picture news. Critical Arts, 28(2), 264–286. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2014.906344

- Wiggins, B. E. (2019). The discursive power of memes in digital culture: Ideology, semiotics, and intertextuality. Routledge.

- Wiggins, B. E., & Bowers, G. B. (2015). Memes as genre: A structurational analysis of the memescape. New Media & Society, 17(11), 1886–1906. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444814535194

- Williams, A. (2020). Black memes Matter: #LivingWhileBlack With Becky and Karen. Social Media + Society, 6(4). https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120981047

- Yoon, I. (2016). Why is it not just a joke? Analysis of Internet memes associated with racism and hidden ideology of colorblindness. Journal of Cultural Research in Art Education, 33, 92–123.

- Zulli, D. (2020). Evaluating hashtag activism: Examining the theoretical challenges and opportunities of #BlackLivesMatter. Participations, 17(1), 197–216.