ABSTRACT

Efforts to govern algorithms have centerd the ‘black box problem,’ or the opacity of algorithms resulting from corporate secrecy and technical complexity. In this article, I conceptualize a related and equally fundamental challenge for governance efforts: black box gaslighting. Black box gaslighting captures how platforms may leverage perceptions of their epistemic authority on their algorithms to undermine users’ confidence in what they know about algorithms and destabilize credible criticism. I explicate the concept of black box gaslighting through a case study of the ‘shadowbanning’ dispute within the Instagram influencer community, drawing on interviews with influencers (n = 17) and online discourse materials (e.g., social media posts, blog posts, videos, etc.). I argue that black box gaslighting presents a formidable deterrent for those seeking accountability: an epistemic contest over the legitimacy of critiques in which platforms hold the upper hand. At the same time, I suggest we must be mindful of the partial nature of platforms’ claim to ‘the truth,’ as well as the value of user understandings of algorithms.

Mounting controversies around algorithms in recent years have prompted concerns about the extent to which they fairly and equitably regulate speech and participation in social life. Responses to these concerns that seek to more effectively govern algorithms have centerd the ‘black box problem,’ or the opacity of algorithms resulting from corporate secrecy and the scale and complexity of algorithms (Ananny & Crawford, Citation2016; Bucher, Citation2018; Burrell, Citation2016). The black box problem stands in the way of effecting greater accountability through oversight. In this article, I call attention to a related and equally fundamental problem, which poses a challenge for governance efforts. The problem emerges from the power dynamic between platforms and users that underlies the legitimization of knowledge claims about algorithms. This power dynamic grows, in part, from the information asymmetry between platforms and users, as platforms withhold, obscure, and strategically disclose details about their algorithms (Burrell, Citation2016; Pasquale, Citation2015). By retaining exclusive access to certain information about their algorithms, as well as user data, platforms have achieved a position of epistemic authority. Platforms, as Gillespie suggested, are ‘in a distinctly privileged position to rewrite our understanding of [algorithms], or to engender a lingering uncertainty about their criteria … ’ (Citation2014, p. 187). Yet, beyond obstructing sight into the black box, I argue that platforms can undermine users’ and other stakeholders’ perceived capacity to autonomously know algorithms independently of platform-sanctioned ‘truth.’ I introduce the concept of black box gaslighting to capture how platforms leverage their epistemic authority to prompt users to question what they know about algorithms, and thus destabilize the very possibility of credible criticisms.

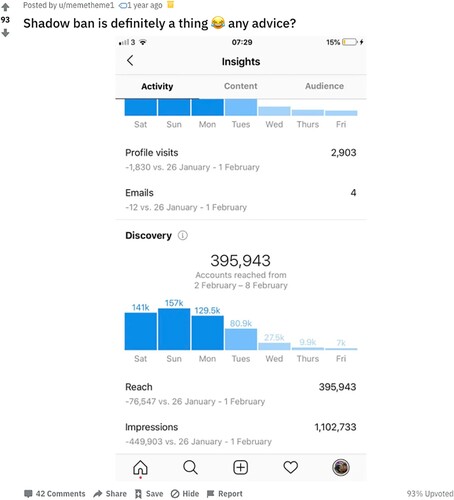

I explicate the concept of black box gaslighting through the case study of the ‘shadowbanning’ dispute within the Instagram influencer community. Influencers are part of a broader population of platform laborers who face ‘algorithmic precarity,’ or ‘the turbulence and flux that emerge as a routine feature of platformized labor’ (Duffy, Citation2020, p. 2). Platforms establish the institutional conditions of labor on their sites through algorithms that prescribe participatory norms as they reify policies and values (Bucher, Citation2018; Cotter, Citation2019). In this sense, influencers feel compelled to know how platform algorithms work to achieve visibility, grow their following, and, ultimately, be successful (Bishop, Citation2019; Cotter, Citation2019; Duffy, Citation2020). For this reason, shadowbanning has provoked considerable anxiety among influencers. Shadowbanning is a moderation technique long used by online forums (Cole, Citation2018). In relation to Instagram, the term is used by influencers to refer to when, without notice or explanation, a user’s post(s) is prevented from appearing in different spaces on the platform, making the content much less likely to reach non-followers. Complaints about shadowbanning typically highlight the lack of control influencers feel they have over their labor in the face of seemingly arbitrary rules and enforcement (Blunt et al., Citation2020). This discourse has also included accusations that Instagram disproportionately shadowbans people of color (BBC News, Citation2020; Salty, Citation2019), women (Cook, Citation2019), and members of the LGBTQ+ community (Joseph, Citation2019; Salty, Citation2019), among others. Instagram, for its part, has denied the use of shadowbanning. Yet, as will be explained, the platform has not been clear or consistent about precisely what it is denying or acknowledged that elements of influencers’ claims ring true. Consequently, Instagram’s denials have provoked considerable confusion.

What is of broad interest in the Instagram shadowbanning dispute is not necessarily what is or is not true about algorithmic moderation on Instagram, but rather how this dispute lays bare the fragile state of users’ capacity, and particularly platform laborers’ capacity, to make credible critical claims about algorithms and their proprietors. In what follows, I suggest that we should not only be concerned about the flow of information about algorithms between platform ‘insiders’ and ‘outsiders,’ but also the different assumptions we have about ‘insider’ and ‘outsider’ information. I argue that black box gaslighting interferes with efforts to mitigate vulnerabilities in the platform economy and, more broadly, to ensure algorithms operate in the public’s best interest.

Platforms, power, and (creative) labor

Platforms shape social practices, values, and institutions through their ubiquitous presence in and mediation of everyday life (Duffy et al., Citation2019; van Dijck et al., Citation2018). Platforms particularly wield significant power over work and employment, which they accomplish through the induction of a new mode of management: the ‘algorithmic boss’ (Duffy, Citation2020; Kellogg et al., Citation2020; Rosenblat & Stark, Citation2016). Platforms have come to mediate workflows in the traditional economy and engendered a new class of ‘gig workers’ (e.g., Uber drivers), microwork laborers or ‘clickworkers’ (e.g., MTurkers), and, most relevant the present study, creative laborers (e.g., influencers). Platforms use algorithms to manage the quality of labor-outputs via ‘soft control’ intended to nudge laborers’ behavior (Kellogg et al., Citation2020; Rosenblat & Stark, Citation2016). Indeed, platforms have gained substantial market power primarily via ‘ownership of the means of behavioral modification’ (Zuboff, Citation2015, p. 82). With data extracted from users, platforms use algorithms to evaluate and hierarchize laborers in ways that ensure their own profitability.

On Instagram and other social media platforms, influencers and other creative laborers generate considerable value for platforms by engaging other users (Craig & Cunningham, Citation2019), which renders them subject to ‘algorithmic control’ (Kellogg et al., Citation2020). Digital influencers are a type of microcelebrity who have accrued a large number of followers and make their living by creating content, building relationships with and communities among users, and promoting products and services (Abidin, Citation2016; Duffy, Citation2017). An influencer’s success is defined largely by how well they can achieve visibility in algorithmically-ranked feeds (Bishop, Citation2019; Christin & Lewis, Citation2021; Cotter, Citation2019). Thus, they view learning about algorithms as a central component of their work (Cotter, Citation2019; Duffy, Citation2020). Yet, learning about algorithms does not guarantee visibility or success. In fact, algorithms tend to exacerbate conditions of instability and inequity in media and cultural industries (Duffy, Citation2020). This ‘algorithmic precarity’ (Duffy, Citation2020) motivates influencers and other creative laborers on platforms to optimize their practices and content according to their understanding of algorithms (Bishop, Citation2018; Cotter, Citation2019; Stuart, Citation2020).

While influencers are essential to the success of platforms, they have little say in establishing the conditions of their labor beyond collective organizing and issuing public complaints and critiques (Cunningham & Craig, Citation2019; Duffy, Citation2017). Moreover, organizing or speaking out carries risks, as doing so may jeopardize current or future access to benefits and privileges afforded by relationships and formal partnerships with platforms (Caplan & Gillespie, Citation2020). Nevertheless, cultivating knowledge about algorithms has helped influencers to resist and/or reign in the demand’s algorithms impose on their day-to-day work and creative processes, to advocate for fair remuneration, and to mobilize collectively (Bishop, Citation2019; Cunningham & Craig, Citation2019; O’Meara, Citation2019). Understanding how algorithms function, why, and with what effect helps influencers ground and give weight to their critiques.

The black boxing of algorithms

Platforms have insulated themselves from public scrutiny by sharing little information about their algorithms (Flyverbom, Citation2016; Pasquale, Citation2015). Keeping tight-lipped helps platforms protect algorithms as their ‘secret sauce’ and prevent people from ‘gaming the system’ (Burrell, Citation2016; Pasquale, Citation2015; Ziewitz, Citation2019). The opacity resulting from such corporate secrecy forms the basis of characterizations of algorithms as black boxes (Pasquale, Citation2015). Although platforms have gradually endeavored to share more information about their algorithms, these efforts have often primarily served to strategically position themselves in the public eye (e.g., Flyverbom, Citation2016; Petre et al., Citation2019), a means by which they seek to ‘establish the very criteria by which these technologies will be judged, built directly into the terms by which we know them’ (Gillespie, Citation2010, p. 359).

Yet, platform efforts to manage disclosures about their algorithms are not the only reason algorithms have been labeled black boxes. In reality, greater transparency does not necessarily make algorithms knowable (Ananny & Crawford, Citation2016; Kemper & Kolkman, Citation2019). Algorithms commonly process enormous datasets with a large number of heterogenous properties, and integrate a series of complex statistical and computational techniques, which limits our capacity to comprehend what they do procedurally (Ananny & Crawford, Citation2016; Burrell, Citation2016; Seaver, Citation2014). Further, machine learning algorithms often operate independently of human oversight. Even when companies can trace algorithms’ work, it still may not be possible to explain why they produce particular models or outcomes (Ananny & Crawford, Citation2016; Burrell, Citation2016; Kroll, Citation2018). Further, algorithms are dynamic (Kitchin, Citation2017). They are developed iteratively (Kroll, Citation2018) and via experimentation (e.g., A/B testing) (Seaver, Citation2014). The internal logic of machine learning algorithms develops in relation to data produced by user activity (Burrell, Citation2016) and alongside the broader system as interfaces, settings, capabilities, and user populations change (Ananny & Crawford, Citation2016). Thus, to the degree that algorithms are constantly in flux, it is difficult to draw stable conclusions about them.

Gaslighting

Gaslighting denotes a kind of manipulation technique, often referenced in popular discourse and psychoanalysis (Spear, Citation2019). Gaslighting occurs under conditions of power asymmetries (Abramson, Citation2014; Sweet, Citation2019) and entails prompting someone to question their reality and conform to the gaslighter’s will. As Spear (Citation2019, p. 5) further explains,

the purpose of gaslighting is not only to neutralize particular criticisms that such individuals might lodge, but to neutralize the very possibility of criticism by undermining the victim’s conception of herself as an autonomous locus of thought, judgement, and action.

Gaslighting is effective in altering individuals’ conception of reality because it is predicated on relationships in which a victim trusts and/or grants authority to their gaslighter (Abramson, Citation2014; Sweet, Citation2019). When gaslighters occupy a position of authority, they can further mobilize their authority ‘as leverage to demand they be treated with unjustified degrees of credence’ (Abramson, Citation2014, p. 21). The tension between victims’ trust of their gaslighters and self-trust founds the basis for self-doubt that inevitably arises from gaslighting. The routine experience of such self-doubt can cause victims to begin to question their own ability to independently and reliably understand their realities clearly (Spear, Citation2019).

In what follows, I illustrate a particular kind of gaslighting observed in the relationship between platforms and users, which is emergent from algorithms’ black box nature. Recently, the scholar-activist collective Hacking//Hustling introduced the concept of platform gaslighting, or

the structural gaslighting that occurs when platforms deny a set of practices which certain users know to be true. […] When platforms deny something like shadowbanning and users feel the impact of it, it creates an environment in which the shadowbanned user is made to feel crazy, as their reality is being denied publicly and repetitively by the platform. (Blunt et al., Citation2020, p. 79)

Method

The case study investigated in this article concerns the ongoing dispute between influencers and Instagram about whether shadowbanning is real. I learned of this dispute through the course of collecting data for a broader project on how Instagram influencers learn about and make sense of algorithms on the platform (Cotter, Citation2020). During the data collection period, Instagram first publicly refuted shadowbanning. Yet, I observed that, in spite of Instagram’s statement, some influencers persisted in their belief that shadowbanning was real. This piqued my interest. I wanted to know how two competing knowledge claims about algorithmic moderation on Instagram (i.e., ‘shadowbanning is real’ vs. ‘shadowbanning is a myth’) could endure, especially when Instagram had weighed in on the matter.

Much of the data in the present study comes from that collected for the broader project and consists of online discourse materials (e.g., social media posts, videos, news articles, etc.) and semi-structured interviews with Instagram influencers (n = 17). I gathered online discourse materials primarily from searches for combinations of relevant keywords (e.g., algorithms, shadowbanning, etc.) in Instagram, Google, YouTube, the subreddits /r/Instagram and /r/InstagramMarketing, as well as Facebook groups for Instagram influencers between September 2017 and May 2020. Nearly all interviews were conducted between May 2018 and November 2018 and lasted an hour on average. Interviewees included those at various points in their careers, including those just starting out and seasoned influencers with hundreds of thousands of followers.

From interviews and online materials, I identified statements about or relevant to shadowbanning issued by Instagram and parent company, Facebook, which include social media posts, official blog posts, help pages, and policy documents. Notably, nearly all statements explicitly referring to shadowbanning were communicated via social media posts or statements to journalists. To ensure a more complete understanding of the shadowbanning discourse and the full range of relevant statements by Instagram, I additionally searched Nexis Uni for media coverage of shadowbanning on the platform through July 2021. To identify articles with statements from Instagram and/or Facebook, I narrowed results to only include articles that referred to spokespeople or any current or former Facebook or Instagram executive.Footnote1 Throughout data collection, I used snowball sampling to gather additional relevant materials (e.g., blog posts from Facebook and Instagram) linked to in the foregoing sources. While Instagram and Facebook’s official documents (blog, help, and policy pages) only refer to shadowbanning on Instagram in two blog posts, for background and context, I additionally reviewed official documents discussing why/how Instagram limits the visibility of content and accounts. To identify these, I searched blog, policy, and help pages for relevant keywords (e.g., visibility, filter, demote, non-recommendable).

While collecting multiple genres of data permits a degree of triangulation – the ability to trace the recurrence of themes across different sources – the qualitative methods I used do not lend themselves to establishing the prevalence of opinions or beliefs. Moreover, influencers’ opinions and beliefs about shadowbanning vary for variety of reasons and the findings that follow necessarily present a simplified view. For example, influencers with more years under their belts, will have experienced various evolutions in platform governance and technical infrastructure that might render their judgements dissimilar from those of newcomers. While this is not a question I pursued, it is worth noting as a limitation and opportunity for future work.

To analyze data collected, I used an inductive qualitative approach informed by constructivist grounded theory (Corbin & Strauss, Citation2014). First, I constructed initial codes for influencers and Instagram’s statements, particularly focusing on coding actions, as a means of sticking close to the data (Charmaz, Citation2014), related to knowledge production. I then synthesized broader themes from this initial coding and compared these back to the data to ground my interpretations (Charmaz, Citation2014). As a final step in the analysis, I looked for points of tension between influencers’ and Instagram’s respective statements about shadowbanning and the platform’s algorithms and compared these.

In the following sections, I describe how influencers understand shadowbanning, and how Instagram has denied the existence of shadowbanning and renarrativized influencers’ experiences with shadowbanning as something else entirely. I then describe influencers’ perceptions of Instagram as an epistemic authority on its algorithms, which compels acceptance of the platforms’ ‘facts.’ Finally, I offer some final thoughts about the broader implications of black box gaslighting.

How influencers understand shadowbanning

Influencers refer to shadowbanning as a shorthand for occasions when posts or accounts are downranked in or filtered out of Instagram’s main feed; Explore, hashtag, and Reels pages; and/or searches without notice. For example, social media strategy influencer Alex Tooby (Citation2017, n.p.) offered her ‘official’ definition of shadowbanning as:

Instagram’s attempt at filtering out accounts that aren’t complying with their terms. The Shadowban renders your account practically invisible and inhibits your ability to reach new people. More specifically, your images will no longer appear in the hashtags you’ve used which can result in a huge hit on your engagement. Your photos are reported to still be seen by your current followers, but to anyone else, they don’t exist.

Interviewer: Have you experienced a shadowban?

Emily: I'm not sure. I feel like I have based on … Especially when it was going on a lot. I always use the same four or five hashtags. Like #[CITY]blogger or #[CITY]girl, or whatever they were. #outfitoftheday, stuff like that. And then all of a sudden it was like I would have no engagement whatsoever on a post.

Interviewer: Just a really significant drop that you were like, ‘Something is off.’

Emily: Right, a really significant drop.

Recently I've made a post and used the same hashtag set I use when posting about that sport […] and I got 0 hashtag impressions. It shows nothing when I go into my insight. It's like I have not put any hashtags.

Based on their experiences, influencers tend to understand shadowbanning as resulting from engaging in activity and/or publishing content deemed undesirable by Instagram, which would degrade the user experience. As Alex Tooby’s aforementioned definition exemplifies, influencers say shadowbanning is a means by which Instagram (algorithmically) enforces platform ‘rules’ to minimize behavior that could be seen a ‘spamming’ and particularly behavior indicative of bots. In a blog post, Tooby cited multiple reasons why accounts might be shadowbanned, which include using automation services that violate the Terms of Service, using a restricted hashtag, and being repeatedly reported by other users (Tooby, Citation2017). In an interview, Marcus similarly characterized shadowbanning as the penalty for engaging in behavior that Instagram deems unacceptable:

So if you're spamming people and you have content that Instagram deems against the rules or something like that, or against their terms of agreement, they're gonna stop pushing that because they feel like that's gonna keep people off the app, I guess. […] So if they think there's some suspicious activity going on in your account that's not authentic or in line with their rules, then they're going to repress your reach …

Algorithmic ranking and moderation on instagram

Before proceeding, a brief primer on algorithmic ranking and moderation on Instagram is in order. Instagram algorithmically arranges content in the main feed, Explore, Reels, and hashtag pages according to predictions of what users ‘care about most’ (Mosseri, Citation2021). Here, engagement (liking, commenting, etc.) serves as a proxy for what users care about (Mosseri, Citation2021). Each post is ranked according to predicted likelihood of engaging with a post, with higher values resulting in more prominent placement in the different surfaces. Ranking values are specific to individual users and predicted from signals derived from both content features (e.g., photo vs. video, keywords) and user characteristics and activity (e.g., age, user interactions).

Instagram also uses algorithms to limit to reach of ‘borderline’ content that does not violate the platform’s Community Guidelines, but is otherwise deemed (usually algorithmically) in ‘bad taste, lewd, violent or hurtful’ (Constine, Citation2019). This policy is part of the 'reduce' component of Facebook’s ‘remove, reduce, and inform’ strategy (Rosen & Lyons, Citation2019, n.p.). ‘Reduction’ can be accomplished by adjusting initial ranking values of posts in order to make them less visible (Owens & Kacholia, Citation2019). For this, an algorithm predicts the likelihood that content is ‘objectionable’ based on signals like user reports or whether it contains certain keywords (Owens & Kacholia, Citation2019). Alternately, certain content is rendered non-recommendable (Instagram, Citationn.d.-a), as explained in a blog post (Rosen & Lyons, Citation2019, n.p.):

We have begun reducing the spread of posts that are inappropriate but do not go against Instagram’s Community Guidelines, limiting those types of posts from being recommended on our Explore and hashtag pages. For example, a sexually suggestive post will still appear in Feed if you follow the account that posts it, but this type of content may not appear for the broader community in Explore or hashtag pages.

Instagram also restricts certain hashtags (e.g., #tagsforlikes, #sunbathing, #ass) in ways that limit the visibility of posts using them (Instagram, Citationn.d.-b). A search for restricted hashtags displays only the ‘Top posts’ and a message stating ‘Recent posts from [hashtag] are currently hidden because the community has reported some content that may not meet Instagram’s community guidelines.’ In other words, Instagram restricts hashtags when many posts using a hashtag exhibit signals that suggest (to algorithms) that they violate content rules.

The above details correlate with influencers’ understanding of shadowbanning. Influencers may see their visibility drop significantly and without explanation for a variety of reasons, for example if they share content deemed objectionable. Moreover, policy changes may result in an influencer’s account or content facing new ranking ‘penalties’ (demotion or non-recommendation) overnight. With these details, it would not be unreasonable to conclude, as reporter Jesselyn Cook (Citation2020) did that ‘selective shadow banning is written into Instagram’s rulebook.’

Renarrativizing shadowbanning

Instagram has issued a variety of public statements that depict shadowbanning as a kind of urban myth. The first time Instagram explicitly referred to shadowbanning, the platform stated, as conveyed by TechCrunch: ‘Shadowbanning is not a real thing, and Instagram says it doesn’t hide people’s content for posting too many hashtags or taking other actions’ (Constine, Citation2018). In this statement, Instagram referred specifically to one kind of behavior many influencers believed contributed to shadowbans. However, in most statements, Instagram offers wholesale denials without much explanation, which makes it difficult to judge exactly what the company is denying. When Instagram’s denials occasionally offer some definition of shadowbanning, they often use a definition that does not fully match that of influencers. For example, Instagram CEO Adam Mosseri has referred to shadowbanning as having content taken down (Facebook, Citation2020), which is not how most influencers define shadowbanning, as discussed above. At face value, Instagram’s statements refute specific ideas about shadowbanning (e.g., shadowbanning results from using too many hashtags and/or constitutes content removals), which narrows the scope of the issue.

Instagram has attempted to debunk the shadowbanning ‘myth’ by suggesting three alternative explanations. First, Instagram has suggested glitches. For example, in the earliest response to criticism about shadowbanning, the company wrote in a Facebook post ‘We understand users have experienced issues with our hashtag search that caused posts to not be surfaced. We are continuously working on improvements to our system with the resources available’ (Instagram, Citation2017). Eva Chen, Instagram’s Director of Fashion Partnerships later reiterated this point in an interview: ‘Shadow banning does not exist, it is a persistent myth […] the day that the shadow banning word became a thing, it’s because there was legitimately a bug that was affecting hashtags’ (May, Citation2019, n.p.). Later, on multiple occasions, Instagram similarly characterized the restriction of certain hashtags (i.e., a form of shadowbanning) as ‘mistakes’ in response to criticism (Are, Citation2019; Rodriguez, Citation2019; Taylor, Citation2019).

Second, to a lesser extent, Instagram has suggested that what influencers understand as shadowbanning is simply their own failure to create engaging content. In the aforementioned earliest statement responding to shadowbanning complaints, most of the company’s post was dedicated to providing advice about how to create ‘good content’ as a ‘growth strategy’ (Instagram, Citation2017). As evident in the comments section, some (indignantly) read this statement as the company blaming influencers for the problems they were experiencing (e.g., ‘You're kidding right?? Sidestepping the issue, telling us it is our fault? What the hell is wrong with you?’).

Third, Instagram has suggested that what seems like shadowbanning is beyond the platform’s control, a matter of chance. For example, in an Instagram story in February 2020, Mosseri said:

Shadowbanning is not a thing. If someone follows you on Instagram, your photos and videos can show up in their feed if they keep using their feed. And being in Explore is not guaranteed for anyone. Sometimes you get lucky, sometimes you won’t.

Over time, Instagram has come closer to affirming shadowbanning. In a blog post in June 2020, without refutation, Mosseri explicitly acknowledged users’ concerns about shadowbanning – specifically, concerns that Black creators were being disproportionately affected as they engaged in Black Lives Matter activism on the platform (see ; Bowenbank, Citation2020).

Over the years we’ve heard these concerns sometimes described across social media as ‘shadowbanning’ – filtering people without transparency, and limiting their reach as a result. Soon we’ll be releasing more information about the types of content we avoid recommending on Explore and other places. (Mosseri, Citation2020a)

It is difficult, if not impossible, to know the intentions behind statements made by Mosseri and Instagram surrogates. Platforms have a variety of logical reasons to be secretive about their algorithms and broader policy matters (e.g., preventing manipulation or protecting against backlash; Gillespie, Citation2018), which would likely apply to Instagram’s handling of the shadowbanning dispute. One reasonable motive would be to distance the platform from stickier claims about intentional and/or biased censorship of certain content – for example, racial justice activism and right-wing content.

Motive aside, while Instagram’s statements avoid obvious falsehoods, they omit important clarifying information, for example a clear and consistent definition of shadowbanning, which permits Instagram’s alternative explanations to take shape. In fact, it is the carefully laid truths in Instagram’s renarrativization of shadowbanning that makes it compelling and which has provoked second-guessing and confusion among influencers, which I will now discuss.

Bringing beliefs in line with the ‘official truth’

Influencers often look to Instagram to verify details about the platform’s algorithms, which affirms the company’s perceived epistemic authority in the shadowbanning dispute. Instagram, then, comes to be seen as the principal (or only) actor in a position to judge the credibility of claims about its algorithms. Exemplifying the authority granted to Instagram, Jessica said in an interview:

I found everybody was up in arms about shadowbanning, because if you use too many hashtags, or the same hashtags, you'll get shadowbanned, blah, blah, blah. And I was like, ‘No, that's not right.’ Instagram never publicly announced that they were shadowbanning. It was just all hearsay, so it was completely BS.

Propagation of misleading information is rife in this subreddit, which in turn leads to more misleading information. Everyone is trying to help, but none of us actually have any answers. That's why if someone is saying something, only linking to a credible source should be allowed. And by that, I mean an official Instagram post …

As influencers have received Instagram’s statements refuting shadowbanning, the epistemic authority granted to Instagram has induced confusion and self-doubt, a parallel sense of not being in a position to properly judge the credibility of claims about shadowbanning. After Instagram’s statements in June 2020, influencer and academic researcher Carolyn Are (Citation2020) explicitly characterized Instagram’s response as gaslighting in a blog post:

Instagram have basically been gaslighting audiences into thinking that the shadowban, algorithm bias and censorship were just their imagination … only to admit they existed without admitting it months later.

I've seen, there's articles out there that have quotes from Instagram directly saying it's fake, and that it's not a thing. So you can find the articles online from people that call themselves strategists, saying that it's real. But I would much rather take the word of Instagram directly because if Instagram has their people making quotes to the media, they're not … I don't think they're legally allowed to lie about that. [chuckle] So I think I would trust that first if they're saying, ‘No, this isn't a thing,’ then it's not a thing …

I actually asked Instagram and they [platform representatives] told me [shadowbanning] wasn't a real thing. […] I legit, I had an email thread with them where they're like, ‘Yeah, that's just not a thing. That never was a thing.’ So, unless I was lied to by my contact in Instagram, it wasn't a thing …

From this position of doubt, many influencers have re-interpreted their insights about algorithmic moderation to bring them in line with Instagram’s narrative of shadowbanning-as-myth. For example, some influencers refer to ‘glitches,’ as Christina did in an interview:

I think [shadowbanning] was something that quickly became a scapegoat for people when they were having any sort of problem with their engagement. It was, ‘Oh I must be Shadowbanned’ but, if you were truly Shadowbanned, you knew it. I think more so it was probably just a temporary glitch in the algorithm …

… there was actually a glitch a couple of months back that was causing people not the show up under hashtags. There were also reports of a similar glitch more recently, after the wave of hacks/backend errors that happened at IG. It seems like most people were able to show up in their hashtags within a couple of weeks of the incident

In my opinion, it’s way easier to blame some mysterious outside source when content underperforms versus taking a hard look at why it failed. Creators tell themselves oh, it’s just the shadowban, that’s why all my posts don’t get many likes instead of investigating ways to improve that failed content. (The Pinnergrammer, Citation2018)

Discussion

The last several years have witnessed an intensification of public outcry over the power of algorithms, for example, controversies surrounding free expression, representation, and (platform) labor conditions. Because creative laborers, including influencers, are particularly motivated to learn about algorithms, the insights they build through their labor have allowed them to see and issue early warnings of problems wrought by algorithms, for example censorship, discrimination, and uneven application of policies (e.g., Caplan & Gillespie, Citation2020; Joseph, Citation2019). In the present case study, when Black Instagram influencers engaged in activism as part of the Black Lives Matter movement raised concerns about racial bias and shadowbanning (e.g., see ), as discussed, it prompted Instagram’s most forthcoming statements about the phenomenon to date and a promise to address the issue. This kind of public outcry is integral in effecting change, but only when perceived as credible criticism. In this article, I have sought to direct attention to a threat to the ability to voice credible criticism: a technique by which platforms can subtly neutralize criticism, which I termed black box gaslighting.

Black box gaslighting rests on the black box nature of algorithms, which results from corporate secrecy and technical complexity. In the present case study, this nature granted Instagram ground upon which to stake plausible denials of shadowbanning. Through careful statements that leveraged perceptions of epistemic authority, Instagram prompted many influencers to second guess what they knew about algorithmic moderation on the platform. Further, even influencers who continued to resolutely assert that shadowbanning was real often saw Instagram as being in possession of, but perhaps reluctant to acknowledge, ‘the truth.’ Consequently, Instagram has maintained the principal authority to confirm or deny knowledge claims about algorithmic moderation on the platform and, so, destabilize criticism. In this, black box gaslighting is not merely a means of shouting down criticism or impeding the ability to speak out. It is a means of configuring users (and other stakeholders) as incapable of assessing algorithms independently of what platforms say about them. It is a means of hardening perceptions of platforms’ epistemic authority on their algorithms, and, as a result, undermining the credibility of outside critics.

Thus far, much of the discussion about governing algorithms has highlighted the importance of transparency, as the black boxing of algorithms makes it difficult to debate and/or challenge their logics, techniques, and outcomes. Transparency practices and black box gaslighting are interrelated. There are legitimate reasons why platforms cannot be fully transparent (e.g., Flyverbom, Citation2016; Pasquale, Citation2015). The allowance of an acceptable level of opacity, in addition to practices of strategic obfuscation (Pasquale, Citation2015) and visibility management (Flyverbom, Citation2016), creates a space for platforms to engage in black box gaslighting, to convincingly suggest that their critics have drawn faulty conclusions as a result of the information they lack, but platforms possess. Accountability requires a critical audience (Kemper & Kolkman, Citation2019). Yet, a critical audience to challenge what algorithms do and how will not affect accountability if platforms can simply render challenges irrational. Black box gaslighting suggests a deterrent for those seeking accountability: an epistemic contest over the legitimacy of critiques in which platforms hold the upper hand. At the same time, it must be said that discerning the consequences and affordances of algorithms, even for platform owners, often requires more than mere access to source code or design specifications (Kemper & Kolkman, Citation2019; Kroll, Citation2018). Much of the decisions or outcomes algorithms produce are not planned, programmed, or anticipated (Kemper & Kolkman, Citation2019). Although it is sometimes inconvenient for platforms to admit, their claim to ‘the truth’ is only partial, and we should be mindful of the incompleteness of their knowledge when platforms refute critiques.

It should also be noted that black box gaslighting is not always effective. In spite of the confusion black box gaslighting provoked, what influencers knew about Instagram’s algorithms helped many see the fault lines in the platform’s renarrativization of shadowbanning, to understand statements as omitting or glossing over important information. I encountered several influencers who asserted themselves in this regard. For example, one user commented in r/Instagram: ‘the official line from Instagram is that shadowbans don't even exist. We all know they do.’ Mia told me in an interview: ‘Instagram have come out and said that they don’t exist, which I don’t believe.’ While many influencers expressed considerable distrust towards Instagram in general, this distrust did not always render influencers immune to perceptions of Instagram’s epistemic authority. What seems to matter more is the knowledge influencers built about Instagram’s algorithms over time. This knowledge offers tools for identifying and critically reflecting on the platform’s attempts (whether deliberate or not) to re-write what they knew. While black box gaslighting can interfere with what people know about algorithms, what people know about algorithms may alternately help them recognize and resist black box gaslighting. In fact, online advice about how to beat a shadowban abounds, which evokes the question of whether black box gaslighting can be diffused when enough people hold that shadowbanning is, in fact, ‘a thing.’

Based on this article’s findings, I suggest that how we treat user understandings of algorithms has consequences for governance efforts. Relying uncritically on platforms’ statements as indices for evaluating the credibility of users’ claims risks reinforcing perceptions of the exclusive epistemic authority of platforms. While platforms do benefit from unparalleled access to certain information about their algorithms, this does not make them the sole authority on all knowledge claims about algorithms. Different vantage points afford different insights. Instagram’s user data allows for various macro-level insights, as guided by a core belief in platforms as neutral actors (Gillespie, Citation2010). However, users have valuable insights to share about algorithms, because algorithmic outcomes arise from highly contextual data inputs that become visible through located, embodied experiences (Bishop, Citation2019; Cotter, Citation2020). In the context of the shadowbanning dispute, this means that influencers were not, as Mosseri suggested in recent statements, without information; they just had access to different information to support the conclusions they drew. In short, the findings suggest an imperative to protect users’ capacity to draw conclusions about algorithms that part with ‘official truths’ certified by platforms. We need to ensure users can effectively advocate for their needs and interests based on their unique insight about what algorithms mean to and for them. This cannot happen if we only trust platforms to legitimate information about algorithms.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Kelley Cotter

Kelley Cotter is an assistant professor in the College of Information Sciences and Technology at The Pennsylvania State University. Her research explores how people learn about and make sense of algorithms, and how such insight may be mobilized in efforts to govern algorithms and platforms [email: [email protected]].

Notes

1 The full search string used was ‘(shadowban* OR “shadow ban” OR “shadow banned” OR “shadow banning”) AND Instagram AND (spokes* OR “Adam Mosseri” OR “Vishal Shah” … etc.)’ filtered for English language only. Executives were identified using the Corporate Affiliations database (http://corporateaffiliations.com).

References

- Abidin, C. (2016). “Aren’t these just young, rich women doing vain things online?”: influencer selfies as subversive frivolity. Social Media+ Society, 2(2), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305116641342

- Abramson, K. (2014). Turning up the lights on gaslighting. Philosophical Perspectives, 28(1), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/phpe.12046

- Ananny, M., & Crawford, K. (2016). Seeing without knowing: Limitations of the transparency ideal and its application to algorithmic accountability. New Media & Society, 20(3), 973–989. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444816676645

- Are, C. (2019). Instagram apologises to pole dancers about the shadowban. https://bloggeronpole.com/2019/07/instagram-apologises-to-pole-dancers-about-the-shadowban/

- Are, C. (2020). Instagram quietly admitted algorithm bias. https://bloggeronpole.com/2020/06/instagram-quietly-admitted-algorithm-bias-but-how-will-it-fight-it/

- BBC News. (2020). Facebook and Instagram to examine racist algorithms. https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-53498685

- Bishop, S. (2018). Anxiety, panic and self-optimization: Inequalities and the YouTube algorithm. Convergence, 24(1), 69–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856517736978

- Bishop, S. (2019). Managing visibility on YouTube through algorithmic gossip. New Media & Society, 21(11-12), 2589–2606. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444819854731

- Blunt, D., Wolf, A., Coombes, E., & Mullin, S. (2020). Posting into the void: studying the impact of shadowbanning on sex workers and activists. https://hackinghustling.org/posting-into-the-void-content-moderation/

- Bowenbank, S. (2020). Instagram CEO Adam Mosseri pledges to amplify black voices after shadow banning accusations. https://www.cosmopolitan.com/lifestyle/a32881196/instagram-ceo-adam-mosseri-black-voices-shadow-banning-accusations/

- Bucher, T. (2018). If … then: Algorithmic power and politics. Oxford University Press.

- Burrell, J. (2016). How the machine ‘thinks’. Big Data & Society, 3(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951715622512

- Caplan, R., & Gillespie, T. (2020). Tiered governance and demonetization. Social Media+ Society, https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120936636

- Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory. SAGE.

- Christin, A., & Lewis, R. (2021). The drama of metrics: Status, spectacle, and resistance among YouTube drama creators. Social Media + Society, 7(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305121999660

- Cole, S. (2018). Where did the concept of ‘shadow banning’ come from? Vice. https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/a3q744/where-did-shadow-banning-come-from-trump-republicans-shadowbanned

- Constine, J. (2018). How Instagram’s algorithm works. TechCrunch. https://techcrunch.com/2018/06/01/how-instagram-feed-works/

- Constine, J. (2019). Instagram now demotes vaguely ‘inappropriate’ content. TechCrunch. https://techcrunch.com/2019/04/10/instagram-borderline/

- Cook, J. (2019). Instagram’s shadow ban on vaguely ‘inappropriate’ content is plainly sexist. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/instagram-shadow-ban-sexist_n_5cc72935e4b0537911491a4f

- Cook, J. (2020). Instagram’s ceo says shadow banning ‘is not a thing.’ that’s not true. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/instagram-shadow-banning-is-real_n_5e555175c5b63b9c9ce434b0

- Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2014). Basics of qualitative research. SAGE.

- Cotter, K. (2019). Playing the visibility game: How digital influencers and algorithms negotiate influence on Instagram. New Media & Society, 21(4), 895–913. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444818815684

- Cotter, K. (2020). Critical algorithmic literacy: Power, epistemology, and platforms [Doctoral dissertation]. Michigan State University.

- Craig, D., & Cunningham, S. (2019). Social media entertainment. NYU Press.

- Cunningham, S., & Craig, D. (2019). Creator governance in social media entertainment. Social Media+ Society. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305119883428.

- Dorpat, T. L. (1996). Gaslighthing. Jason Aronson, Inc.

- Duffy, B. E. (2017). (Not) getting paid to do what you love. Yale University Press.

- Duffy, B. E. (2020). Algorithmic precarity in cultural work. Communication and the Public. https://doi.org/10.1177/2057047320959855.

- Duffy, B. E., Poell, T., & Nieborg, D. B. (2019). Platform practices in the cultural industries: Creativity, labor, and citizenship. Social Media + Society, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305119879672

- Facebook. (2020). Fuel for India 2020. https://fb.watch/2oxg8yvpVw/

- Flyverbom, M. (2016). Transparency: Mediation and the management of visibilities. International Journal of Communication, 10, 110–122. http://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/4490

- Gillespie, T. (2010). The politics of ‘platforms’. New Media & Society, 12(3), 347–364. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444809342738

- Gillespie, T. (2014). The relevance of algorithms. In T. Gillespie, P. J. Boczkowski, & K. A. Foot (Eds.), Media technologies (pp. 167–194). MIT Press.

- Gillespie, T. (2018). Custodians of the internet. Yale University Press.

- Instagram. (2017). We understand users have experienced issues with our hashtag … [Instagram post]. https://www.facebook.com/instagramforbusiness/posts/1046447858817451

- Instagram. (n.d.-a). Why are certain posts on Instagram not appearing in Explore and hashtag pages? https://help.instagram.com/613868662393739

- Instagram. (n.d.-b). Why can’t I search for certain hashtags on Instagram? https://help.instagram.com/485240378261318

- Joseph, C. (2019). Instagram’s murky ‘shadow bans’ just serve to censor marginalised communities. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/nov/08/instagram-shadow-bans-marginalised-communities-queer-plus-sized-bodies-sexually-suggestive

- Kellogg, K. C., Valentine, M. A., & Christin, A. (2020). Algorithms at work: The new contested terrain of control. Academy of Management Annals, 14(1), 366–410. https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2018.0174

- Kemper, J., & Kolkman, D. (2019). Transparent to whom? No algorithmic accountability without a critical audience. Information, Communication & Society, 22(14), 2081–2096. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2018.1477967

- Kitchin, R. (2017). Thinking critically about and researching algorithms. Information, Communication & Society, 20(1), 14–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2016.1154087

- Kroll, J. A. (2018). The fallacy of inscrutability. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 376(2133), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2018.0084

- May, N. (2019). “Could things be going faster? Yes”: Eva Chen on sustainability, shadow banning and the future of Instagram. https://www.standard.co.uk/fashion/eva-chen-selfridges-instagram-popup-fast-fashion-sustainability-future-of-instagram-a4303496.html

- Mosseri, A. (2020a). Ensuring black voices are heard. https://about.instagram.com/blog/announcements/ensuring-black-voices-are-heard

- Mosseri, A. (2020b). Our latest actions racial justice … [Instagram post]. https://www.instagram.com/p/CBnwzaYJ6ap/

- Mosseri, A. (2021, June 8). Shedding more light on how Instagram works. https://about.instagram.com/blog/announcements/shedding-more-light-on-how-instagram-works

- Myers West, S. (2018). Censored, suspended, shadowbanned. New Media & Society, 20(11), 4366–4383. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444818773059

- O’Meara, V. (2019). Weapons of the chic. Social Media+ Society, 5(4), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305119879671

- Owens, E. J., & Kacholia, V. (2019). U.S. Patent No. 10,229,219. Washington, DC: U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

- Pasquale, F. (2015). The black box society. Harvard University Press.

- Petre, C., Duffy, B. E., & Hund, E. (2019). Gaming the system. Social Media+ Society, 5(4), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305119879995

- Rodriguez, J. (2019). Instagram apologizes to pole dancers after hiding their posts. https://www.ctvnews.ca/sci-tech/instagram-apologizes-to-pole-dancers-after-hiding-their-posts-1.4537820

- Rosen, G., & Lyons, T. (2019). Remove, reduce, inform. https://about.fb.com/news/2019/04/remove-reduce-inform-new-steps/

- Rosenblat, A., & Stark, L. (2016). Algorithmic labor and information asymmetries. International Journal of Communication, 10(27), 3758–3784.

- Salty. (2019). An investigation into algorithmic bias in content policing of marginalized communities on Instagram and Facebook. https://saltyworld.net/algorithmicbiasreport-2/

- Seaver, N. (2014). Knowing algorithms. http://nickseaver.net/s/seaverMiT8.pdf

- Spear, A. D. (2019). Epistemic dimensions of gaslighting. Inquiry, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/0020174X.2019.1610051

- Stuart, F. (2020). Ballad of the bullet. Princeton University Press.

- Sweet, P. L. (2019). The sociology of gaslighting. American Sociological Review, 84(5), 851–875. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122419874843

- Taylor, S. (2019). Instagram apologizes for blocking Caribbean carnival content. https://www.vice.com/en_ca/article/7xg5dd/instagram-apologizes-for-blocking-caribbean-carnival-content

- The Pinnergrammer. (2018). The Instagram shadow ban – Myth or reality. https://thepinnergrammer.com/the-instagram-shadow-ban-myth-or-reality/

- Tooby, A. (2017). Are you the victim of an Instagram shadowban?? Here’s why & how to remove it from your account! https://alextooby.com/instagram-shadowban/

- van Dijck, J., Poell, T., & De Waal, M. (2018). The platform society. Oxford University Press.

- Ziewitz, M. (2019). Rethinking gaming: The ethical work of optimization in web search engines. Social Studies of Science, 49(5), 707–731. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312719865607

- Zuboff, S. (2015). Big other: Surveillance capitalism and the prospects of an information civilization. Journal of Information Technology, 30(1), 75–89. https://doi.org/10.1057/jit.2015.5