ABSTRACT

Satirical news and its effects on outcomes such as appreciation and persuasion have gained considerable currency as a topic of research in mass communication studies. Through the framework of construal level theory, we investigated whether different levels of spatial distance influence these effects. In a between-subjects experiment, participants in the United Kingdom (UK; n = 282) and New Zealand (NZ; n = 370) read a satirical or non-satirical news text summarizing a study reporting on the negative impact of increased digital device screen time on young children. Depending on condition, the texts referred to entities and locations in either the participant’s own country (spatially close) or a foreign country (spatially distant). Results showed significant main effects of satirical news on audience perceptions, emotions, and attitudes. While there were no significant interactions between article type (satirical vs. regular news) and spatial distance (close vs. distant), our results indicated that satirical news was associated with higher perceptions of spatial distance for both the UK and NZ participants as well as higher perceptions of social distance for the NZ participants. Exploratory indirect-effects analyses found several indirect effects of satirical news through increased perceptions of spatial and social psychological distance on audience emotions, text perceptions, and attitudes. We take these results as initial evidence suggesting spatial and social distance are potential variables to consider in future investigations of satirical news.

Satirical news is a unique blend of entertainment, news, and political opinion which has spawned localized variants across the globe (Brugman et al., Citation2020; Baym, Citation2005; Baym & Jones, Citation2012). Accordingly, satirical news has gained considerable currency as a topic of research in fields like mass communication (Becker, Citation2020). Researchers investigating satirical news have provided a better understanding regarding how the interplay of critique, entertainment, and information delivery associated with satirical news influences audience perceptions, attitudes, and other reactions towards different topics (Burgers & Brugman, Citation2021; Becker & Waisanen, Citation2013). Some of these influences are relatively stable – for example satirical news is more likely to be taken less seriously and to be perceived as more humorous when compared to a non-satirical equivalent (e.g., Brugman & Burgers, Citation2021; Skalicky, Citation2019). Other effects of satire, such as on persuasion, have been less consistent (Burgers & Brugman, Citation2021; Boukes et al., Citation2015; Brewer et al., Citation2013). Differences among topics, audiences, and authors of satire have been cited as potential moderators for this variation in the effects of satirical news (Boukes et al., Citation2015; LaMarre et al., Citation2009; Skalicky & Crossley, Citation2019).

One means to further explore these effects is via the concept of psychological distance as defined by construal level theory (Trope & Liberman, Citation2010). This theory holds that entities and events perceived to be further away in terms of spatial, temporal, or social measures are more psychologically distant and, in turn, are construed more abstractly (Trope et al., Citation2007; Trope & Liberman, Citation2010). When construed more abstractly, events and entities are conceptualized using more generic and less specific features. Greater psychological distance is associated with the believability of unlikely or improbable events (Sungur et al., Citation2019) and perceptions of humor (Bischetti et al., Citation2020; McGraw et al., Citation2014). Because satirical news presents information using similar strategies (i.e., literally unbelievable messages and humor), it may be the case that differences in psychological distance may also influence the manner in which audiences attend to satirical news.

Due to both domestic and international viewership and coverage of the news in general, satirical news likely contains various topics which differ in their proximity to an individual’s own physical location. These differences in spatial distance could, in turn, influence effects of satire associated with believability, humor, or more. However, to our knowledge, no research has investigated spatial distance in the context of satirical news. Accordingly, in the current study we take an initial step towards answering this question by investigating whether differences in spatial distance influences the effects of satirical news.

Satirical news

Satirical news blends comedy, news, and opinion into a unique format which has been described as a ‘potentially powerful form of public information’ (Baym, Citation2005, p. 273). A wealth of research in mass communication suggests this potential has been at least partially realized: although people choose to engage with satirical news because of the humorous components, they also consume satire to gain information about politics and other newsworthy events (Becker, Citation2020; Young, Citation2013). In addition to televised formats, satirical news has proliferated online via an ever-growing number of news websites across the globe, such as The Onion (USA), The Beaverton (Canada), The Civilian (New Zealand), and The Daily Mash (United Kingdom). Satirical news websites are thus becoming a ubiquitous method for communicating information online, which explains the increasing interest in this form of communication from researchers in mass communication and similar disciplines (Brugman et al., Citation2020; Becker, Citation2020; Skalicky, Citation2019).

Effects of satirical news

Various studies have been conducted to understand the effects of satirical news. These effects include perceptions and emotions towards satirical news items as well as opinions and attitudes towards the topics being satirically criticized. A common finding in much of this research is that these effects are varied based on a variety of factors, including audience populations, satirical strategies, and the nature of the topic being satirized (for overviews, see Burgers & Brugman, Citation2021; Becker, Citation2020; Becker & Waisanen, Citation2013).

Text perceptions

Measures of text perceptions towards satirical news typically include assessing perceptions of humor, liking, enjoyment, and whether the information provided is discounted as non-serious. When compared to a non-satirical equivalent, satirical news usually scores higher on these measures: satire is liked more, seen to be more humorous, but more often discounted by its audience (Burgers & Brugman, Citation2021; LaMarre et al., Citation2014; Skalicky, Citation2019). Text perceptions of satirical news have also been shown to be interdependent – for instance when satirical news is perceived as more humorous, it is also more likely to be discounted (Holbert et al., Citation2011; LaMarre et al., Citation2009, Citation2014; Skalicky & Crossley, Citation2019). The strength of these effects varies based on differences in the format and presentation of satirical news as well as individual differences of the audience.

H1: Compared to a non-satirical equivalent, a satirical news item will (a) be seen as more humorous, (b) more liked, and (c) more discounted.

Emotions and attitudes towards topics

Studies have also documented how satirical news affects attitudes and opinions towards the satirized topic. This research demonstrates that satire can elicit both positive and negative emotions (Burgers & Brugman, Citation2021; Peifer & Landreville, Citation2020). For example, Peifer and Landreville (Citation2020) demonstrated that satire can increase positive emotions like hope among viewers who share the perspective of the satirist. In addition, by virtue of being satirical, most satirical news contains negative sentiment towards a topic. It follows then that exposure to satirical critiques has been shown to increase an individual’s own negative emotions towards that same topic, making both emotions and attitudes more congruent with the satirical critique (Brewer et al., Citation2013; Lee & Kwak, Citation2014). However, satirical news is not always successful at persuading audiences to take up the satirical critique (Burgers & Brugman, Citation2021) and, in some cases, the opposite effect is obtained in that sympathy is raised for the satirical target (Baumgartner & Morris, Citation2008). In short, because satirical news is a form of entertainment, it has the potential to increase positive emotions and lead to less disagreement with the satirical message. At the same time, because satirical news is critical, it can also lead towards more negative emotions towards the satirical topic. In both cases, these emotional reactions could make audience attitudes more congruent with the satire.

H2: Compared to a non-satirical equivalent, satirical news will elicit (a) higher positive emotional responses, (b) higher negative emotional responses, and (c) attitudes more congruent with the text towards the topic.

Psychological distance and satire

The brief review above summarizes expected effects for satirical news on a variety of audience responses, and demonstrates that these effects are driven by different functions of satirical news (e.g., entertainment, information delivery, and persuasion). In this study, we extend the current research into these effects to explore an additional means for studying satire through the framework of construal level theory (CLT; Trope et al., Citation2007; Trope & Liberman, Citation2010). CLT maintains that people subjectively perceive varying levels of psychological distance between themselves and other entities, which in turn influences how abstractly or concretely these entities are mentally construed. The reference point for any one person’s perception of psychological distance is egocentric and anchored in their immediate spatial, temporal, and social context (Trope & Liberman, Citation2010). Entities and topics in a text or video which are different from this baseline are thus perceived to be at greater distances from these baselines. When psychological distance between an audience and a topic increases, this tends to amplify abstract (rather than concrete) qualities of the topic, which in turn can moderate cognitive processes related to prediction, evaluation, judgment, and more (Trope & Liberman, Citation2010).

We focus on spatial distance specifically because there is some evidence to suggest perceptions towards phenomena relevant to satirical news, such as improbable events and verbal humor, are associated with or influenced by increased spatial distance (Bischetti et al., Citation2020; Sungur et al., Citation2019). A defining characteristic of satirical news is that it challenges a reader’s standards of believability by presenting seemingly unbelievable events as news, which in turn invites a reader to recognize and decipher the satirical incongruity (Simpson, Citation2003). The believability in satirical news is thus related to a reader’s understanding of what is possible in the world. Although measuring a different sort of believability, one study of spatial distance reported participants attributed events associated with lower overall probabilities of occurring to come from geographically distant (vs. close) locations (Sungur et al., Citation2019). If spatial distance were to affect the believability of a satirically framed news event in a similar manner, increased spatial distance may bolster the believability of the satirical story, which may serve to cloak the underlying satirical critique and in turn attenuate any effects of satirical news.

In addition, humor is a crucial component of satirical news (Boukes et al., Citation2015; Simpson, Citation2003; Skalicky, Citation2019). Psychological distance has been suggested as a potential explanation behind the theoretical underpinnings for one theory of humor: benign violation theory (Warren & McGraw, Citation2016). This theory predicts that feelings of humor rely on a tension between an existing violation (e.g., an incongruity between meanings or events) and the degree of acceptability of that violation (i.e., how benign the violation is for the audience). This tension may be influenced by psychological distance, wherein more severe violations (e.g., joking about tragedies) are perceived to be more benign with increased psychological distance (e.g., greater time since the tragedy), increasing perceptions of humor (McGraw et al., Citation2012). A recent study investigating humor in COVID-19 memes among Italians found such an effect for spatial distance: Italians living further (vs. closer) from the epicenter of COVID-19 in Italy found COVID-19 memes to be more humorous (Bischetti et al., Citation2020).

We also take the current study as an opportunity to explore the effects of satirical news in different national contexts. Much of the research into satirical news reviewed above has been conducted within a single geographical or social context (cf. O’Connor, Citation2017), and usually within the United States (cf. Boukes et al., Citation2015), where characteristics unique to the US political climate have arguably shaped the nature of American satirical news (Young, Citation2019). Accordingly, one goal of the current study is to replicate the effects of satirical news on audience text perceptions, emotions, and attitudes among audiences outside of the United States. Because we are interested in testing the role of spatial distance, we chose two countries which contain native-English speaking populations but are geographically distant from one another: The United Kingdom and New Zealand.

The current study

If the entities and events in a satirical news text are viewed more abstractly via increased spatial distance, this may influence the effects of satirical news exposure on audience text perceptions, emotions, and attitudes. However, it is difficult to predict whether spatial distance will serve to enhance or attenuate some (or all) of these effects, leading to contrasting predictions. Indeed, from a humor perspective, a certain amount of spatial distance is necessary in order to accept and appreciate any humorous critique directed towards a serious topic (Bischetti et al., Citation2020; McGraw et al., Citation2014). As such, increased levels of spatial distance should amplify the effects of satirical news on text perceptions because of the safer distance between the audience and the target. However, increased spatial distance is also associated with increased believability of unlikely events, because these events are then construed more abstractly (Sungur et al., Citation2019). This means that satire framed in a geographically distant location may make it more difficult for an audience to recognize the claim to insincerity necessary for a satirical critique (Simpson, Citation2003), which could reduce any satirical effects. Finally, while satire is thought to enhance emotional responses (Burgers & Brugman, Citation2021), studies of psychological distance in other contexts suggest increased spatial distance attenuates emotional reactions (van Lent et al., Citation2017; Williams et al., Citation2014). As such, it is unclear which effects will prevail when studying the influence of spatial distance on satirical news. We thus pose the following research question in order to explore these potentially competing effects.

RQ1: To what extent does spatial distance moderate the effects of satirical (versus non-satirical) news on perceptions, attitudes, and emotions?

Materials and methods

Design

We designed an online experiment using a 2 (country: UK vs. NZ) x 2 (spatial distance: far vs. close) x 2 (article type: satirical news vs. regular news) between-subjects design. Spatial distance was manipulated by recruiting participants from two distinct geographic locations, the United Kingdom (UK) and New Zealand (NZ), and having them read texts set in either the UK or NZ. A survey was designed to measure different responses from participants towards the text and topic of the text, including text liking, perceptions of humor, message discounting, emotions, and attitudes.

Satirical and non-satirical news articles

An authentic satirical news article published in The Onion was used as the satirical news text (The Onion, Citation2019). This satirical news text summarized a fictional study describing risks associated with increased screen time for children. The fictional study claimed greater use of digital devices such as tablets and cell phones increased the risk of children becoming social-media influencers (i.e., social-media users who attempt to influence audience purchasing decisions). The satirical versions of the text used in the current study retained most of the original text, although some of the article was modified to make the text shorter and more cohesive with the non-satirical versions. A non-satirical corollary to the satirical text was created by adapting the original Onion text using additional language and phrases drawn from a non-satirical news article seriously discussing the same topic (Naftulin, Citation2019). The non-satirical news article also. described a study about parents’ fears regarding risks associated with increased screen time for children. However, the non-satirical news article claimed greater use of digital devices such as tablets and smartphones increases the risk of developmental issues appearing as children age, such as underdeveloped cognitive, social, and physical skills. Thus, the main point (screen time is bad for children) and structure of the two articles were approximately similar, but they differed in their presentation (satirical vs. non-satirical).

Psychological distance manipulation

Locations and entities in the texts were then changed so that the news articles appeared to be based on a study conducted in either in London (UK) or Wellington (NZ). The focus of the fictional study was also changed to echo fears of either British or Kiwi parents towards the risk of screen time exposure on their own children. Because our participants resided in either the UK or NZ, these different versions of the texts thus served to index a geographically close or distant relationship with the reader, depending on whether the locations and populations named in the texts matched with the reader’s local context. Online Appendix A contains the complete stimulus materials. All online appendices for this paper can be found on the Open Science Framework (OSF) repository: https://osf.io/2zbqd/.

Instrumentation

Manipulation Check

Unless mentioned otherwise, all items were measured on 7-point Likert scales. To assess whether the spatial distance manipulation was successful, participants indicated their agreement with the following statement (Sungur et al., Citation2016): ‘The event described in the news report felt like it is happening close to where I am’. From the same scale, we also measured perceived temporal distance (‘ … close to my current time’) and social distance (‘ … close to people like me’). All items were reverse coded and analyzed separately (spatial: M = 3.76, SD = 1.78; temporal: M = 2.71, SD = 1.41; social: M = 3.85, SD = 1.80).

Text Perceptions

General text liking was measured with five items, in which participants were asked whether they found the text to be (a) boring (reverse-coded), (b) enjoyable, (c) interesting, (d) lively, and (e) pleasing (Sundar, Citation1999; M = 3.67, SD = 0.97, Cronbach’s α = .77). Perceived humor was assessed with three items, in which participants indicated whether they found the text to be (a) funny, (b) amusing, and (c) entertaining (Nabi et al., Citation2007; M = 2.99, SD = 1.40, Cronbach’s α = .84). We also included aversiveness as an alternative measure of liking using one item, asking participants whether they found the text disturbing (Bischetti et al., Citation2020; M = 3.92, SD = 1.58).

Message discounting was measured using four items from Nabi et al. (Citation2007). Participants were asked to indicate to what extent they agreed with the following statements about the text: ‘the author of the message was just joking,’ ‘the message was intended more to entertain than to persuade,’ ‘the author was serious about advancing his views in the message,’ and ‘it would be easy to dismiss this message as simply a joke.’ The items were averaged to create a message discounting scale (M = 3.15, SD = 1.46, Cronbach’s α = .86).

Emotions

Participants’ emotional responses to the articles were measured using seven items from Lecheler et al. (Citation2015). Participants were asked to indicate to what extent they agreed with the following statements: ‘While reading the text, I felt: (a) enthusiastic, (b) content, (c) compassioned, (d) hopeful, (e) afraid, (f) angry, and (g) sad.’ Following the discrete-emotions perspective (Nabi, Citation2010), all emotions were analyzed separately: enthusiastic (M = 2.99, SD = 1.30), content (M = 3.39, SD = 1.28), compassioned (M = 3.62, SD = 1.38), hopeful (M = 3.01, SD = 1.23), afraid (M = 3.17, SD = 1.59), angry (M = 3.25, SD = 1.48), and sad (M = 3.90, SD = 1.58).

Attitudes

Participants’ attitudes toward appropriate amounts of screen time for children were measured using six items adapted from Cingel and Krcmar (Citation2013), of which three items tapped into participants’ positive attitudes and three items tapped into participants’ negative attitudes. Participants were asked to indicate to what extent they agreed with the following statements: ‘I believe electronic media have a positive/negative effect on children’s: (a) cognitive development (e.g., reasoning skills), (b) social development (e.g., communication skills), and (c) physical development (e.g., motor skills).’ The items belonging to positive attitudes and negative attitudes toward screen time were averaged to create two scales (positive attitudes: M = 3.87, SD = 1.19, Cronbach’s α = .75; negative attitudes: M = 4.38, SD = 1.16, Cronbach’s α = .76). Additionally, participants were asked to write how many hours per day they felt would be an appropriate screen time limit for pre-school children (2-5 years; M = 1.48, SD = 1.33) and school-aged children (6-12 years; M = 2.56, SD = 1.54).

Control Variables

We also collected a number of control variables asking participants about their experience with childcare, political affiliation, news viewing habits, levels of attention towards the article, and demographic features. Online Appendix B includes detailed information about these variables, as well as additional analyses comparing the results reported below with and without these control variables. The results in online Appendix B demonstrate these variables did not significantly influence our findings and thus we report our analysis below without them.

Participants

The data presented in this study were collected through an online experiment with 679 participants. Native-English speaking participants were recruited from two different English-speaking countries: The United Kingdom (UK) and New Zealand (NZ). We excluded nineteen participants who read the article in less than twenty seconds and eight participants who were unable to sufficiently summarize the article’s main point. This left 652 participants (UK: n = 282; NZ: n = 370; 32% men, 67% women; age range 18-83, Mage = 36.77, SDage = 14.07; 62% obtained at least a Bachelor’s degree; see online Appendix B for a more detailed description of the demographic variables for each country).

UK participants were recruited using the online crowdsourcing service Prolific Academic (www.prolific.ac) and received £1.25 for their participation. There are no online crowdsourcing platforms similar in nature to Prolific in New Zealand. Therefore, a total of 370 NZ participants were recruited through postings made on the main NZ subreddit (r/newzealand) on www.reddit.com, as well as though emails sent to professional and academic staff at a large university in New Zealand. Participant recruitment was further aided by asking participants to share the recruitment message with their extended networks of families and friends. For their time, these participants were compensated with a digital gift voucher worth $20NZD.

Procedure

The online experiment was conducted using Qualtrics. After participants agreed to the informed consent form, they received questions to determine if they belonged to the target group of the study: native speakers of English who were permanent residents or citizens of the country in which the data were collected. After these questions, all participants read one of the four articles and provided a short summary of the main point of the article. They next completed a questionnaire that measured our dependent variables, control variables, and demographic characteristics. Upon completion, participants were thanked and debriefed. The entire experiment lasted approximately ten minutes.

Results

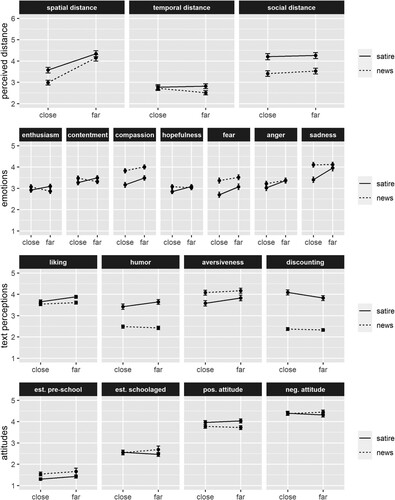

Many dependent variables in this study were correlated (see online Appendix C for a correlation matrix). We therefore analyzed the data using several MANOVA models, one for each dependent variable type: (1) perceived psychological distance (manipulation check), (2) positive emotions, (3) negative emotions, (4) text perceptions, and (5) attitudes. Because our UK and NZ participants responded differently to the satirical and regular news texts (e.g., text liking was higher in the UK sample than in the NZ sample regardless of article type; see online Appendix D), all MANOVA models included article type (satire vs. news), manipulated spatial distance (far vs. close), country (UK vs. NZ) and the interactions between these variables as predictors. We provide the dataset, code, and output on OSF: https://osf.io/2zbqd/. provides a visual overview of our variables across experiment conditions, and Online Appendix E contains means and standard deviations per condition.

Manipulation Check

A MANOVA with the above described predictors indicated our spatial distance manipulation was successful (Wilks’ λ = 0.88, F(3,642) = 28.22, p < .001, η2p = .12). Participants rated texts from the foreign country as more spatially distant than texts from their own country (F(1,644) = 52.37, p < .001, η2p = .08). We found no effects of the distance manipulation on perceived social distance (F(1,644) = 0.39, p = .53, η2p = .001) or perceived temporal distance (F(1,644) = 0.59, p = .44, η2p = .001), suggesting our measure of psychological distance was focused on spatial distance as we intended.

Direct Effects of Satire

H1 and H2 predicted direct effects of satirical news on text perceptions, emotions, and attitudes when compared to a non-satirical equivalent. Results showed direct effects of the satire condition on text perceptions (Wilks’ λ = 0.67, F(4,641) = 79.58, p < .001, η2p = .33). The satirical news texts were liked more (F(1,644) = 7.10, p = .01, η2p = .01), perceived as more humorous (F(1,644) = 115.48, p < .001, η2p = .15), found to be less aversive (F(1,644) = 11.44, p < .001, η2p = .02), and were more often discounted (F(1,644) = 302.60, p < .001, η2p = .32) than the regular news texts. On the basis of these findings, we can accept the predictions associated with H1 because satire was seen as more humorous (H1a), was more liked and found to be less aversive (H1b) and was more discounted (H1c).

Results also showed direct effects of the satire condition on both positive emotions (Wilks’ λ = 0.94, F(4,641) = 9.44, p < .001, η2p = .06) and negative emotions (Wilks’ λ = 0.96, F(3,642) = 8.82, p < .001, η2p = 004). Participants reported less feelings of compassion (F(1,644) = 31.78, p < .001, η2p = .05), fear (F(1,644) = 20.15, p < .001, η2p = .03), and sadness (F(1,644) = 12.47, p < .001, η2p = .02) after reading the satirical texts when compared to regular news texts. No direct effects of the satire condition were found in case of enthusiasm (F(1,644) = 0.16, p = .69, η2p < .001), contentment (F(1,644) = 0.03, p = .87, η2p < .001), hopefulness (F(1,644) = 0.80, p = .37, η2p = .001), and anger (F(1,644) = 0.71, p = .40, η2p = .001). On the basis of these findings, we cannot accept the predictions of H2a and H2b because significant differences for both positive (H2a) and negative (H2b) emotions indicated these emotions were lower rather than higher for satirical (vs. regular) news.

We also found direct effects of the satire condition on attitudes (Wilks’ λ = 0.97, F(4,641) = 4.57, p = .001, η2p = .03). In line with the position advocated in the satirical news texts, results demonstrated that participants’ estimations of appropriate screen time for preschool children were lower after reading the satirical news texts than after reading the regular news texts (F(1,644) = 5.09, p = .02, η2p = .01). By contrast, participants exposed to satirical news also reported more positive attitudes towards screen time (F(1,644) = 7.35, p = .01, η2p = .01). No effects were found for the satire condition on screen time estimations for school-aged children (F(1,644) = 0.81, p = .37, η2p = .001) nor on negative attitudes towards screen time (F(1,644) = 0.47, p = .50, η2p = .001). On the basis of these findings, we find only partial support for H2c because only one measure was congruent with the satirical message (i.e., a critique of extended screen time), while another was not.

The analyses revealed no interaction effects between article condition and country on the dependent variables, indicating these direct effects were similar between the two countries (see online Appendix D for more details). Taken together, satirical (vs. regular) news texts were associated with lower feelings of compassion, fear, and sadness, more positive text perceptions, more message discounting, and attitude change in contradictory directions. We thus find broad evidence to support H1a-c, but little to no evidence supporting H2a-c.

Interaction Effects

Our research question (RQ1) asked whether spatial distance influenced the effects of satirical news when compared to non-satirical news. Our results indicated that spatial distance did not significantly influence the effects of satirical news. This is because our results included no evidence for interaction effects between the experimental conditions (text condition and spatial distance) on the of dependent variables: text perceptions (Wilks’ λ = 0.99, F(4,641) = 1.61, p = .17, η2p = .01), positive emotions (Wilks’ λ = 0.99, F(4,641) = 1.22, p = .30, η2p = .01), negative emotions (Wilks’ λ = 0.99, F(3,642) = 1.70, p = .17, η2p = .01), and attitudes (Wilks’ λ = 0.99, F(4,641) = 1.16, p = .33, η2p = .01). This finding was not caused by response differences between the UK and NZ samples, because three-way interactions of article type, manipulated spatial distance, and country were also not significant: text perceptions (Wilks’ λ = 1.00, F(4,641) = 0.78, p = .54, η2p = .01), positive emotions (Wilks’ λ = 0.99, F(4,641) = 1.89, p = .11, η2p = .01), negative emotions (Wilks’ λ = 1.00, F(3,642) = 0.79, p = .50, η2p = .004), and attitudes (Wilks’ λ = 1.00, F(4,641) = 0.68, p = .61, η2p = .004).Footnote1

Exploratory Analysis: Indirect Effects

Although we found no significant interaction between text condition and our manipulated spatial distance variable (i.e., the modifications to locations in the texts), suggests text condition may have influenced participant responses to the measures of perceived psychological distance. Results from an additional MANOVA suggested this was indeed the case: Wilks’ λ = 0.95, F(3,642) = 10.60, p < .001, η2p = .05. Participants rated the satirical texts not only more spatially distant than regular news texts (Msatire = 3.97, SDsatire = 1.75; Mnews = 3.56, SDnews = 1.79; F(1,644) = 9.13, p = .003, η2p = .01), but also as more socially distant (Msatire = 4.23, SDsatire = 1.81; Mnews = 3.47, SDnews = 1.71; F(1,644) = 31.38, p < .001, η2p = .05). No effect of the satire condition was found on perceived temporal distance (Msatire = 2.80, SDsatire = 1.47; Mnews = 2.62, SDnews = 1.35; F(1,644) = 2.55, p = .11, η2p = .004).

Perceived Spatial Distance

In light of the above results, we conducted an exploratory analysis to determine whether perceptions of spatial and social distance mediated effects of article type on our other dependent variables. To do so we conducted a mediation analysis with 5,000 bootstraps using the PROCESS macro in SPSS (model 4; Hayes, Citation2017).

The mediation analysis identified several indirect effects of article type through perceived spatial distance. These results included a negative indirect effect of the satire condition through perceived spatial distance on liking (b = −0.04, 95%CI [−0.08, −0.01]) and aversiveness (b = −0.04, 95%CI [−0.08, −0.003]). By contrast, we observed a positive indirect effect for message discounting (b = 0.05, 95%CI [0.01, 0.09]). In this manner, increased perceptions of spatial distance served to enhance the direct effects of satirical news on message discounting and aversiveness. In the case of text liking, however, increased perceptions of spatial distance suppressed the positive direct effects of satirical news because increased spatial distance was associated with decreased text liking, suggesting that satirical news texts perceived as closer were also more liked.

The mediation analyses also revealed negative indirect effects of satirical (vs. regular) news exposure through perceived spatial distance on enthusiasm (b = −0.03, 95%CI [−0.06, −0.001]), compassion (b = −0.03, 95%CI [−0.07, −0.004]), fear (b = −0.05, 95%CI [−0.10, −0.01]), and sadness (b = −0.03, 95%CI [−0.07, −0.002]). As such, increased perceptions of spatial distance associated with the satirical texts served to further attenuate the main effects of lower feelings of fear, compassion, and sadness towards the satirical news reported above. While there were no significant main effects of satire on measures of enthusiasm, this effect was significantly mediated by increased perceptions of spatial distance in the same direction as the other emotions. In all, lower reported emotions in response to the satirical news texts may be a result of the higher perceptions of spatial distance (van Lent et al., Citation2017; Williams et al., Citation2014), which may in turn explain why our results above did not support the predictions of H2a and H2b.

Finally, indirect effects of the satire condition through perceived spatial distance were observed for one attitude variable: negative attitudes towards screen time (b = −0.02, 95%CI [−0.06, −0.002]). This observed indirect effect could explain the lack of a direct effect of satirical (vs. regular) news exposure on negative attitudes towards screen time. That is, perceptions of spatial distance after reading the satirical news texts may not have been high enough. See online Appendix F for the path coefficients of the models.

Perceived Social Distance

Our results also showed that the satire condition was associated with increased perceptions of social distance, and that this effect was stronger than perceptions of spatial distance (η2p = .05 social; η2p = .01 spatial). Perceptions of psychological distance are thought to be interrelated (Trope & Liberman, Citation2010), and therefore we conducted additional exploratory analysis of potential indirect effects through perceived social distance. However, when observing differences in effects between participant samples (see online Appendix D) this direct effect of satirical (vs. regular) news on perceived social distance seemed to be driven by the NZ participants’ responses. Therefore, moderated mediation analysis (with country as moderator and social distance as mediator) was conducted with 5,000 bootstraps and again using the PROCESS macro in SPSS (model 7; Hayes, Citation2017).

In these results, we observed indirect effects of the satire condition on various dependent variables through perceived social distance in only the NZ sample. Specifically, results included negative indirect effects of article type through perceived social distance in the NZ sample on enthusiasm (b = −0.12, 95%CI [−0.21, −0.05]), contentment (b = −0.08, 95%CI [−0.15, −0.01]), compassion (b = −0.17, 95%CI [−0.26, −0.09]), hopefulness (b = −0.11, 95%CI [−0.18, −0.04]), fear (b = −0.17, 95%CI [−0.27, −0.09]), sadness (b = −0.10, 95%CI [−0.19, −0.01]), liking (b = −0.16, 95%CI [−0.24, −0.10]), and negative attitudes towards screen time (b = −0.06, 95%CI [−0.12, −0.002]). Positive indirect effects were found for message discounting (b = 0.15, 95%CI [0.08, 0.24]).

In a similar manner to the indirect effects of spatial distance, the indirect effects of increased social distance in the satirical text condition for the NZ participants enhanced the direct effects of compassion, fear, sadness, and discounting, while reducing the effects of liking. In addition, for some dependent variables for which we did not find a direct effect of satire (enthusiasm, contentment, hopefulness, and negative attitudes), we did find an indirect effect of satire through increased social distance. Path coefficients of the models are reported in online Appendix F.

Discussion

The primary motivation for this study was to explore whether differences in psychological (spatial) distance influenced effects of satirical news on text perceptions, emotions, and attitudes. A secondary purpose was to investigate the effects of satirical news in two contexts where this type of research has yet to be systematically conducted (i.e., the UK and NZ). We address the second of these two first while discussing results related to direct effects.

Direct Effects of Satirical News

Our two hypotheses predicted satirical news would have specific effects on participant text perceptions, emotions, and attitudes. The results of our analysis largely support the predictions made for text perceptions – the satirical texts were found to be more humorous (η2p = .15), more discounted (η2p = .32), more liked (η2p = .01), and less averse (η2p = .02). The results for humor and discounting also comprised the largest effect sizes among our results, aligning well with past research which has highlighted the salience of the playful insincerity in satirical news (Becker, Citation2020; Holbert et al., Citation2011; LaMarre et al., Citation2014; Skalicky, Citation2019).

Unlike our hypothesis for text perceptions, our hypothesis for the effects of satirical news on participant emotions and attitudes was not supported. Firstly, we found no differences between satirical and regular news for measures of emotions aside from compassion (η2p = .05), fear (η2p = .03), and sadness (η2p = .02). These measures were lower for satirical (versus regular) news, running counter to our prediction that measures of positive and negative emotions would be stronger in the satirical news condition. This may suggest the satirical humor served as a discounting cue and thus reduced negative views towards the topic (Becker & Anderson, Citation2019). Secondly, our results included a seemingly contradictory effect for our measures of attitudes. Because satire is typically associated with increased negative perceptions towards the satirical target (Becker, Citation2020; Lee & Kwak, Citation2014), we predicted a similar attitude would be reflected in our data towards screen time. While participants who read the satirical text indicated significantly fewer hours should be devoted to screen time for pre-school aged children (η2p = .01), our data also indicated these same participants reported significantly higher positive perceptions towards screen time (η2p = .01). As a recent meta-review of mental health and computer use has suggested (Meier & Reinecke, Citation2021), these responses may index perceived ambiguity regarding the term used to measure these attitudes (i.e., screen time). In other words, screen time itself may be seen as generally positive, but perhaps only in small amounts.

Taken as a whole, our results provide evidence that effects associated with satirical news typically documented in American contexts replicate to new populations, such as the UK and NZ. However, our findings for emotions and attitudes ran counter to our predictions, likely reflecting underlying factors between the content of the text and characteristics of our participants. In this manner, our results echo a plethora of prior research in this area which has identified a number of moderators associated with individual differences of both the text and participants, such as more overt uses of humor (Becker & Anderson, Citation2019; LaMarre et al., Citation2014) and different levels of background knowledge (Boukes et al., Citation2015; Skalicky, Citation2019).

Satirical News and Spatial Distance

Because prior research has reported effects for spatial distance on phenomena similar to satirical news (i.e., believability and humor; Bischetti et al., Citation2020; McGraw et al., Citation2014; Sungur et al., Citation2019), we also asked whether differences in spatial distance may influence the effects of satirical news. However, our analysis found no significant interactions between our spatial distance manipulation (close versus far), article type (satirical versus news), and our dependent variables. This suggests that spatial distance did not influence any effects of satirical news on text perceptions, emotions, or attitudes. One explanation for this finding may be that our satirical text was so overtly satirical that the strong effects of discounting and humor reported above served to detract from perceptions otherwise associated with locations in the text.

That being said, our results included evidence of a different effect in that perceptions of both spatial and social distance were significantly higher in the satirical news condition when compared to the non-satirical condition. It may be the case that the satirical frame prompted a more abstract construal of the text, in turn increasing core dimensions of psychological distance: spatial and social relations (Trope & Liberman, Citation2010). These effects led us to conduct exploratory mediation analyses to probe whether the effects of satire might be mediated through (rather than moderated by) psychological distance. The results included several indirect effects for spatial (both UK and NZ) and social (NZ only) distance, which allowed us to update the initial answer to our research question by advancing the claim that, although this analysis was exploratory, differences in perceived psychological distance influence the effects of satirical news on text perceptions, emotions, and attitudes.

There were two particularly noteworthy findings in our analysis of indirect effects. Firstly, increased perceptions of spatial and social distance served to amplify effects of message discounting but attenuate effects of liking for satirical news. This means increased psychological distance may have decreased the believability of the satirical message while also increasing positive responses towards the satire, results which run counter to effects of spatial distance through abstract construal reported in other CLT research (Sungur et al., Citation2019). Secondly, the effects of satire on both positive and negative emotions were attenuated in the spatially distant condition. Similar attenuating effects of spatial distance have been reported in other studies of psychological distance (van Lent et al., Citation2017; Williams et al., Citation2014), and thus the results here provide further evidence of how spatial distance influences affect. As such, these findings suggest that known effects of satirical news may either be enhanced or attenuated when associated with increased perceptions of psychological distance.

Although we believe our results provide some initial evidence suggesting psychological distance may play a role during the interpretation of satirical news, there are some limitations that should be considered. Firstly, we tested our research questions using a single news text item about one particular topic (i.e., screen time use). We chose this topic because it represents an issue likely to be widespread in both the United Kingdom and New Zealand. However, other topics framed satirically and non-satirically may evoke different emotional and attitudinal responses. Secondly, written satirical news is only one specific type of satire, and thus it would be important to investigate the role of psychological distance in other forms of satire. An immediate choice would be to study these effects on televised satirical news. Finally, in this study we focused mainly on spatial distance. Future studies should consider manipulating other aspects of psychological distance. Social distance, in particular, may be a fruitful variable to explore based on the current results, and also because satirical news in part relies on perceived relationships among reader, audience, and target (Simpson, Citation2003).

In all, our analysis provides an initial investigation into the role of psychological distance and satirical news. Based on these results, a satirical frame may serve to increase perceptions of spatial and social distance, which is an effect that should be of interest to researchers interested in satirical news specifically and psychological distance broadly. Moreover, we provide evidence to suggest consistent effects associated with satire (i.e., humor, liking, and discounting) largely based on research in one context (i.e., the United States) replicate to other English-speaking countries (i.e., the United Kingdom and New Zealand). As such, our study suggests the effects of satirical news survive cultural and global boundaries while simultaneously presenting a previously unexplored relationship between satirical news and perceptions of space.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Stephen Skalicky

Stephen Skalicky is a Senior Lecturer in the School of Linguistics and Applied Language Studies at Victoria University of Wellington in Wellington, New Zealand. Stephen is broadly interested in studying links between language and cognition. His research primarily involves quantitative psychological and linguistic approaches to study creative language such as satirical discourse, figurative language, humour, and language play.

Britta C. Brugman

Britta C. Brugman is a PhD Candidate in the Department of Communication Science at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. Her research is funded through NWO VIDI project 276-45-005 and focuses on the linguistic features and communicative impact of satirical news.

Ellen Droog

Ellen Droog is a PhD Candidate in the Department of Communication Science at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. Her research is funded through NWO VIDI project 276-45-005 and focuses on the use and processing of figurative language in satiric news.

Christian Burgers

Christian Burgers is a Full Professor of Communication and Organisations in the Amsterdam School of Communication Research (ASCoR), University of Amsterdam. At the time this study was conducted, he was an Associate Professor in the Department of Communication Science at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam and a Professor by special appointment in Strategic Communication (Logeion Chair) in the Amsterdam School of Communication Research (ASCoR), University of Amsterdam. He studies strategic communication across discourse domains and is the project leader of NWO Vidi project 276-45-005.

Notes

1 Direct effects of the psychological distance condition are reported in online Appendix G.

References

- Baumgartner, J., & Morris, J. S. (2008). One “nation,” under stephen? The effects of The Colbert Report on American youth. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 52(4), 622–643. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838150802437487

- Baym, G. (2005). The Daily Show: discursive integration and the reinvention of political journalism. Political Communication, 22(3), 259–276. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584600591006492

- Baym, G., & Jones, J. P. (2012). News parody in global perspective: Politics, power, and resistance. Popular Communication, 10(1–2), 2–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/15405702.2012.638566

- Becker, A. B. (2020). Applying mass communication frameworks to study humor’s impact: Advancing the study of political satire. Annals of the International Communication Association, 44(3), 273–288. https://doi.org/10.1080/23808985.2020.1794925

- Becker, A. B., & Anderson, A. A. (2019). Using humor to engage the public on climate change: The effect of exposure to one-sided vs. two-sided satire on message discounting, elaboration and counterarguing. Journal of Science Communication, 18(4), Article A07. https://doi.org/10.22323/2.18040207

- Becker, A. B., & Waisanen, D. J. (2013). From funny features to entertaining effects: Connecting approaches to communication research on political comedy. Review of Communication, 13(3), 161–183. https://doi.org/10.1080/15358593.2013.826816

- Bischetti, L., Canal, P., & Bambini, V. (2020). Funny but aversive: A large-scale survey of the emotional response to covid-19 humor in the Italian population during the lockdown. Lingua, 249, Article 102963. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2020.102963

- Boukes, M., Boomgaarden, H. G., Moorman, M., & de Vreese, C. H. (2015). At odds: Laughing and thinking? The appreciation, processing, and persuasiveness of political satire. Journal of Communication, 65(5), 721–744. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12173

- Brewer, P. R., Young, D. G., & Morreale, M. (2013). The impact of real news about “fake news”: Intertextual processes and political satire. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 25(3), 323–343. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijpor/edt015

- Brugman, B. C., & Burgers, C. (2021). Sounds like a funny joke: Effects of vocal pitch and speech rate on satire liking. Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology, 75(2), 221–227. https://doi.org/10.1037/cep0000226

- Brugman, B. C., Burgers, C., Beukeboom, C. J., & Konijn, E. A. (2020). Satirical news from left to right: Discursive integration in written online satire. Journalism, Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884920979090

- Burgers, C., & Brugman, B. C. (2021). Effects of satirical news on learning and persuasion: A threelevel random-effects meta-analysis. Communication Research. https://doi.org/10.1177/00936502211032100

- Cingel, D. P., & Krcmar, M. (2013). Predicting media use in very young children: The role of demographics and parent attitudes. Communication Studies, 64(4), 374–394. https://doi.org/10.1080/10510974.2013.770408

- Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford publications.

- Holbert, R. L., Hmielowski, J., Jain, P., Lather, J., & Morey, A. (2011). Adding nuance to the study of political humor effects: Experimental research on Juvenalian satire versus Horatian satire. American Behavioral Scientist, 55(3), 187–211. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764210392156

- LaMarre, H. L., Landreville, K. D., & Beam, M. A. (2009). The irony of satire: Political ideology and the motivation to see what you want to see in The Colbert Report. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 14(2), 212–231. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161208330904

- LaMarre, H. L., Landreville, K. D., Young, D., & Gilkerson, N. (2014). Humor works in funny ways: Examining satirical tone as a key determinant in political humor message processing. Mass Communication and Society, 17(3), 400–423. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2014.891137

- Lecheler, S., Bos, L., & Vliegenthart, R. (2015). The mediating role of emotions: News framing effects on opinions about immigration. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 92(4), 812–838. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699015596338

- Lee, H., & Kwak, N. (2014). The affect effect of political satire: Sarcastic humor, negative emotions, and political participation. Mass Communication and Society, 17(3), 307–328. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2014.891133

- McGraw, A. P., Warren, C., Williams, L. E., & Leonard, B. (2012). Too close for comfort, or too far to care? Finding humor in distant tragedies and close mishaps. Psychological Science, 23(10), 1215–1223. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797612443831

- McGraw, A. P., Williams, L. E., & Warren, C. (2014). The rise and fall of humor: Psychological distance modulates humorous responses to tragedy. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 5(5), 566–572. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550613515006

- Meier, A., & Reinecke, L. (2021). Computer-mediated communication, social media, and mental health: A conceptual and empirical meta-review. Communication Research, 48(8), 1182–1209. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650220958224

- Nabi, R. L. (2010). The case for emphasizing discrete emotions in communication research. Communication Monographs, 77(2), 153–159. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637751003790444

- Nabi, R. L., Moyer-Gusé, E., & Byrne, S. (2007). All joking aside: A serious investigation into the persuasive effect of funny social issue messages. Communication Monographs, 74(1), 29–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637750701196896

- Naftulin, J. (2019). A new study suggests screen time could delay children’s communication, motor, and problem-solving skills. Business Insider. https://www.businessinsider.nl/screen-time-could-delay-child-development-study-2019-1/

- O’Connor, A. (2017). The effects of satire: Exploring its impact on political candidate evaluation. In J. Milner Davis (Ed.), Satire and politics (pp. 193–225). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-56774-7_7.

- Peifer, J. T., & Landreville, K. D. (2020). Spoofing presidential hopefuls: The roles of affective disposition and positive emotions in prompting the social transmission of debate parody. International Journal of Communication, 14, 200–220.

- Simpson, P. (2003). On the discourse of satire: Towards a stylistic model of satirical humour. John Benjamins Publishing.

- Skalicky, S. (2019). Investigating satirical discourse processing and comprehension: The role of cognitive, demographic, and pragmatic features. Language and Cognition, 11(3), 499–525. https://doi.org/10.1017/langcog.2019.30

- Skalicky, S., & Crossley, S. A. (2019). Examining the online processing of satirical newspaper headlines. Discourse Processes, 56(1), 61–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/0163853X.2017.1368332

- Sundar, S. S. (1999). Exploring receivers’ criteria for perception of print and online news. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 76(2), 373–386. https://doi.org/10.1177/107769909907600213

- Sungur, H., Hartmann, T., & van Koningsbruggen, G. M. (2016). Abstract mindsets increase believability of spatially distant online messages. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01056

- Sungur, H., van Koningsbruggen, G. M., & Hartmann, T. (2019). Psychological distance cues in online messages: Interrelatedness of probability and spatial distance. Journal of Media Psychology, 31(2), 65–80. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-1105/a000229

- The Onion. (2019). Parenting experts warn screen time greatly increases risk of child becoming an influencer. The Onion: America’s Finest News Source. https://www.theonion.com/parenting-experts-warn-screen-time-greatly-increases-ri-1832241704

- Trope, Y., & Liberman, N. (2010). Construal-level theory of psychological distance. Psychological Review, 117(2), 440–463. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018963

- Trope, Y., Liberman, N., & Wakslak, C. (2007). Construal levels and psychological distance: Effects on representation, prediction, evaluation, and behavior. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 17(2), 83–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1057-7408(07)70013-X

- van Lent, L. G., Sungur, H., Kunneman, F. A., van de Velde, B., & Das, E. (2017). Too far to care? Measuring public attention and fear for Ebola using Twitter. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 19(6), e193. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.7219

- Warren, C., & McGraw, A. P. (2016). Differentiating what is humorous from what is not. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 110(3), 407–430. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000041

- Williams, L. E., Stein, R., & Galguera, L. (2014). The distinct affective consequences of psychological distance and construal level. Journal of Consumer Research, 40(6), 1123–1138. https://doi.org/10.1086/674212

- Young, D. G. (2013). Laughter, learning, or enlightenment? Viewing and avoidance motivations behind The Daily Show and The Colbert Report. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 57(2), 153–169. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2013.787080

- Young, D. G. (2019). Irony and outrage: The polarized landscape of rage, fear, and laughter in the United States. Oxford University Press.