?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

There is a growing body of literature around the concept of artivism, which refers to artists who use social engagement and activism in their artistic practices. Artists, however, are not necessarily perceived as political actors and are heard for their political activism only through a legitimacy cross-over from artistic field to political field. In this paper, therefore, we theorize that audience attention has become an important resource for political legitimacy and study how a set of artivists are received on social media. To this end we have analyzed over two million tweets and argue that content on social media platforms such as Twitter provides insight into how people talk about social issues, such as politics and activism. We employ the methods of topic modeling and semantic network analysis to study how Twitter users engage with artivists and find that very few Twitter users are interested in the societal issues that artivists raise. Instead, the majority of tweets in our data involves attention to state prosecution, media-centric artistic recognition and consumerism. These findings indicate that even though some artivists succeed in bringing their activist art to Twitter audiences, political activism that originates from artists is rarely a topic of discussion among Twitter users in terms of its activist content.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

‘I don't think anybody can separate art from politics. The intention to separate art from politics is itself a very political intention’ (Der Spiegel, Citation2011). This quote by Ai Weiwei highlights how problematic artivists find it to separate art and politics. Artistic and political legitimacy, however, follow different logics. Artworks and artists are legitimated through artistic hierarchies that gatekeepers within art fields set (Bourdieu, Citation1993). Political legitimacy, in contrast, is achieved increasingly through media and audience attention, which have come to (partially) substitute political and intellectual elites (Simons, Citation2003). As people are increasingly focused on individual persons and their ideas – instead of political parties and their respective political programs and ideologies (Karvonen, Citation2010), audience attention has become an important resource for political legitimacy. Activist artists or artivists have to navigate these two logics. Yet, although much has been written on artistic legitimacy (Baumann, Citation2007), less is known about the attention to – and reception of – activism by artists.

This paper discusses the degree and type of attention media audiences give to artivists by focusing on social media. Platforms such as Twitter afford everyday political discussions among media audiences, often strongly in relation to news media content (Wilkinson & Thelwall, Citation2012). They maintain an infrastructure that allows their users to openly exchange ideas that are relevant to politics in an everyday fashion (Vromen et al., Citation2015). We therefore analyzed over two million tweets from Twitter users about six artivists. They are considered artivists in that they seek social change and highlight pressing social issues throughout their artistic practices (Danko, Citation2018). The methods of topic modeling and semantic network analysis were employed to answer the following research question: to what extent and how do artivists receive attention for their activism on Twitter?

This paper provides two main contributions. First, by bringing together insights from social movement studies, cultural sociology, and political science, we address the ways in which artists are able to engage in activism through a legitimacy cross-over from the art field to the political field. This paper therefore adds to the growing body of literature on social engagement and activism in the arts (Bishop, Citation2012; Danko, Citation2018). It offers a more comprehensive theory of artivism that takes into account the dynamics between the art, political and social media fields. Second, we further develop the formal study of culture ‘to capture, analyze, and understand cultural patterns’ (Edelmann & Mohr, Citation2018, p. 1). While topic modeling bridges the quantitative and the qualitative – preserving hermeneutic meaning, the interpretation of the results remains challenging. By combining topic modeling with semantic network analysis, we ‘provide a systematic method of focusing qualitative microscopes within the increasingly overwhelming world of big data’ (Bail, Citation2014, p. 474).

Theoretical framework

Activism within the arts

A growing body of research identifies a social turn in the arts. Here artworks and artists are perceived to be increasingly evaluated on the basis of social rather than artistic criteria (Bishop, Citation2012). Some artists seek social change in society by incorporating political activism in their artistic expression. They have been described as artivists (Danko, Citation2018). Political activism is understood as the practice of dissent that widens the sphere of political participation beyond institutional or governmental politics (Neumayer & Svensson, Citation2016). Through political activism, excluded views and expressions are brought into political debates (Dahlberg, Citation2007). Artivists, then, seek legitimacy as artists and social change in the broader society through their political activism. Current research, however, focuses on the production of art, providing little attention to the reception of artivists as both artist and political actor.

In order to understand the reception of artivists, we draw upon – and combine – insights from social movement studies, cultural sociology and political science. First, social movement studies have primarily focused on activists who have instrumentalized modes of artistic expression to further their political cause. Examples range from Chilean arpilleras that helped in resisting Pinochet’s repressing regime (Adams, Citation2002) to the rock concerts for debt relief in the Global South (Street, Citation2012). In these studies, however, artistic expression is a means to achieve the goals of social movements, instead of (also) being a means by itself.

Second, we draw on cultural sociology to understand how artists gain legitimacy within a field of cultural production. Since the field of art has come to constitute itself as relatively autonomous (Bourdieu, Citation1993), acceptance to speak about politics is not a given for artists. In general, legitimacy entails a process through which the unaccepted becomes accepted through some degree of consensus among a constituency (Zelditch, Citation2001). For artistic legitimacy, Bourdieu (Citation1993) emphasizes the centers of cultural authority, such as museums and galleries, where decisions are made about which artistic expressions are accepted as legitimate works of art. Such consensus-forming among the inner members of the art field (Baumann, Citation2007) is particularly characteristic for the arts.

Third, political science literature outlines how acceptance to engage in politics and hence legitimacy in the political field is achieved. Politics, here, is understood as participation and engagement in acts that affect or influence government actions or public policy, such as raising societal issues through protests and participating in political parties (Ekman & Amnå, Citation2012). In the past processes of political legitimation took mainly place within the terrain of political elites; today legitimation in politics is largely oriented to popular culture publics (Simons, Citation2003). In governmental politics, politicians increasingly rely on access to mass (social) media and their audiences for political legitimacy (Kriesi et al., Citation2013; Loader et al., Citation2016). Likewise, the politics of protest follow this logic by seeking political legitimacy in and through news media (Cottle, Citation2008). According to Karvonen (Citation2010), people are increasingly focused on individual persons and their ideas, instead of political parties and their respective political programs and political ideologies. Audience attention and acceptance, in other words, have become key resources for political legitimacy: those who are accepted to engage in politics are those who are accepted by the broader public to do so.

Artists are able to engage in activism through a legitimacy cross-over from the art field to the political field. Indicative of this, popular culture celebrities, such as Hollywood actors or hip-hop stars (Harlow & Benbrook, Citation2019), who commit themselves to political causes, derive their political legitimacy from their representation of mass popular culture audiences and their claim to represent a constituency (Watts, Citation2020). Roussel and Lechaux (Citation2010, p. 22) describe this as a symbolic coup: the celebrity’s audience is equated with a constituency. Artivists, then, require attention among the broader public for their political activism to impact the broader society. Yet, we know very little the type and degree of attention given to artivists beyond the art field.

Social media platforms such as Twitter have come to constitute communicative spaces that afford ordinary people in society to engage in politics through everyday political talk (Vromen et al., Citation2015) by sharing ideas, reiterating statements and reacting to news and to other users. The content on social media platforms, therefore, provides insight into how people talk about political issues. Studying audience attention to artivists on social media thus allows us to study the degree in which and how social media audiences discuss the art and activism of artivists.

Twitter, in particular, provides us with an empirical window to study the audience attention and acceptance of artivists. Twitter is a microblogging service that facilitates the dissemination of short bursts of information (tweets), allowing its users to publicly engage in conversation with others and share their views (Hogan, Citation2010). Apart from news media platforms, politicians, celebrities or companies, most Twitter users are ordinary people, the majority being below thirty years of age and originating from populous areas (Sloan et al., Citation2015). Furthermore, the default privacy setting of Twitter accounts is public so that most views that users express on the platform are publicly available and invite many others to react (boyd et al., Citation2010).

Based on a large-scale study of Twitter content, Wilkinson and Thelwall (Citation2012) show that many tweets relate to news events and politics. Moreover, Twitter is used actively during election campaigns (Evans et al., Citation2017) and serves as an important campaigning tool for activists (Wonneberger et al., Citation2020). As such, Twitter facilitates in spreading information about politics (Howard & Hussain, Citation2011) and affords its users to engage in politics through participating in everyday political discussions. Even though connective social media platforms are often used for reproducing and repurposing meaning (Mortensen, Citation2017), the Twittersphere constitutes a communicative space where a fairly large proportion of ordinary people in society openly exchanges ideas that are relevant to politics in an everyday fashion. Twitter, to this extent, allows us to study (online) everyday communicative processes through which the broader public discusses artivists and their activist practices.

Artivist cases

In lieu of a comprehensive database of artivists, we have selected six artivist cases though an iterative process. They are similar in the sense that they are all (1) visual artists who (2) display elements of political activism (online and/or offline), (3) have been met with some degree of (legal) controversy in their country of origin, and (4) whose work has generated substantial Twitter attention needed to do topic modeling. Yet, we take a ‘diverse-case’ approach, aiming to capture substantial variation along two dimensions (Gerring, Citation2008). First, the different degrees of freedom that artivists face constitute a useful measure for artistic freedom. The more freedom artivists enjoy, the more likely it is, we expect, that people consider them to be artists and, vice versa, we expect more attention devoted to their activism in case artivists experience less freedom. Indeed, Western media audiences have been found to be particularly interested in the cosmopolitan repressed other (Chouliaraki, Citation2013). Unsurprisingly, the selected artivists from authoritarian states have purposively targeted Western audiences (Gapova, Citation2015; Preece, Citation2015; Rahbaran, Citation2012). Following Norris (Citation2002), we therefore consulted the annual Freedom of the World Report (Freedom House, Citation2016) as a proxy for the different degrees of repression that each artivist might experience within their respective countries. This report uses an aggregation of various indicators for political rights and civil liberties and therefore describes in which national contexts our cases operate professionally. Second, cases were selected based on different degrees of media coverage.Footnote1 The more media coverage artivists receive, the more likely it is that they receive attention on Twitter. displays an overview of our six cases.

Table 1. Cases in context.

Ai Weiwei is an internationally-renowned Chinese artist – and a (micro-)blogging ‘communication activist’ (Strafella & Berg, Citation2015, p. 152) – whose visual artworks often explicitly address human rights issues (Hancox, Citation2014). He was detained in 2011 by Chinese authorities and for alleged tax evasion.

Banksy is a UK street artist, who is well-known for using graffiti to provide social commentary on current global human rights issues (Brassett, Citation2009). Many authorities consider his murals to be vandalism, despite some works selling for huge sums of money at auction houses.

Hans Haacke is an established German artist living and working mostly in New York. His work often revolves around the relationship between museums and their corporate sponsors (Bourdieu & Haacke, Citation1995), resulting in several cases of censorship.

Jafar Panahi is an Iranian film director whose films have been banned in Iran due to their critical depiction of life in Iran (Rahbaran, Citation2012). He was arrested and sentenced to jail in 2010, and subsequently banned from producing movies.

Pussy Riot is a Russian avant-garde activist group, whose hit-and-run punk performances are acts of social resistance against the Russian government and institutions of power. In 2012, some members faced legal prosecution after they staged a performance in a Moscow church and spent two years in jail (Riccioni & Halley, Citation2021).

Jonas Staal is a Dutch visual artist whose work explores the role of art in political processes. In 2005 he produced works in which the death of (still living) Dutch right-wing politician Geert Wilders was mourned (Kranenberg, Citation2007). Perceived as death threats, Staal was arrested and brought to trial, only to be acquitted later.

Research design

Data

Data was collected in late 2016-early 2017 from Twitter by manually scrapingFootnote2 all English-language tweets that contained the names of the selected cases. We opted for a six-year period (2010–2015) to include multiple (media) events for each artivist case in our data. Data preparation consisted of several steps. First, tweets from verified Twitter accounts such as news platforms, celebrities, and politicians were omitted as the focus in this paper is on ordinary users. Second, Twitter users that accounted for one percent or more of the total annual tweets on one case were marked as potential spam accounts. We deleted tweets of accounts that included a large number of identical tweets.Footnote3 Third, tweets shorter than three words were removed as they are difficult to interpret meaningfully. For the remaining 2,201,286 tweets, words that bear low meaningFootnote4 and all links and emojis were deleted in order to strengthen the topic model (DiMaggio et al., Citation2013). Because of the sheer size of the dataset, inexactitudes such as messy spelling can, for a large part, be rendered irrelevant for the outcome (Mayer-Schonberger & Cukier, Citation2013).

Method

Methods like topic modeling (TM) and semantic network analysis (SNA) serve as helpful tools to uncover meaningful themes within large datasets of textual documents. TM produces groups of words – topics – that are associated by their frequent occurrence together. They convey dominant latent themes within texts. The strength of TM is that it assumes that the meaning of words emerges from their use in the context of other words (Mohr & Bogdanov, Citation2013). This means that, within all the text in the data, if particular unique words occur several times in varying semantic contexts they will appear in multiple topics to different degrees. One potential weakness of TM, however, is that the researcher has to tell the algorithm how many topics it needs to identify in the data. Assessing the right number of topics is a process of trial-and-error until saturation and stability is reached where no new themes emerge when requesting more topics.

The output of TM was used to conduct a SNA. Methods like SNA, too, build on the assumption that the meaning of words emerges from their semantic contexts (Dreiger, Citation2013) and strengthen the interpretation and visualization of textual data (Weij & Berkers, Citation2019). Since TM includes each word in the dataset in one of the topics, we can assess the relationship between topics. By setting SNA up in this way, we do not assess the relationship between individual words, which would be similar to TM. Rather, we analyze the relationship between groups of words that appear together frequently. Combining TM and SNA uniquely enables us to discern major themes on a higher level of abstraction, by assessing clusters of topics that are semantically related, while still addressing semantic nuances within these broader themes by assessing individual topics.

For this study, each individual tweet is treated as a textual document. The Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) algorithm provided in the Mallet toolkit was first used. LDA is a topic model algorithm that provides a specified number of topics and estimates how each textual document in the dataset exhibits these topics (DiMaggio et al., Citation2013). The program Gephi was subsequently used to conduct a semantic network analysis. The nodes in the semantic network graph represent the topics from our model. The ties between topics represent the relationship between two given topics, calculated as follows:

where

represents the total amount of distinct words occurring both in topics

and

;

represents the number of occurrences of word

in topic

and

represents the number of occurrences of word

in topic

. The relationship between topics can be calculated this way since every instance of each word in the corpus is assigned to a topic. This means that when a word (e.g., the word ‘car’) occurs several times in the corpus (i.e., the word ‘car’ is used multiple times within one document and/or in multiple documents), it can be assigned to one topic in one instance and to another topic in another instance. As such, the weight of the tie between two given topics is high when the topics have words in common and when the frequency with which particular instances of those words are assigned to both topics is similar. Conversely, for example, if two topics only share one word that appears 1,000 times in the data and is assigned to topic

999 times and only 1 time to topic

, then that word is, semantically speaking, much more important for the interpretation of the first topic. In this case, these two topics will exhibit a weak tie in the network graph, only to become stronger if they have more distinct words in common and if the occurrences of those words are more balanced between the two topics.

We then used Gephi’s modularity algorithm to assess and visualize whether some topics are more highly interconnected than others. Not all topics have to yield meaningful interpretations (DiMaggio et al., Citation2013), however. For each cluster of topics, therefore, we will go into those topics that are substantively meaningful and exhibit the most interesting ties with other topics in the network graph. The analysis is subsequently based on two outputs: (1) the topic solution that consists of the collections of words that occur together frequently and (2) the textual documents that exhibit the topic most highly according to probability scores, providing qualitative ground for our interpretation of topics.

Analysis

shows all collected tweets per case. Ai Weiwei, Banksy and Pussy Riot together account for 98.91% of all collected tweets. Explaining why specific cases receive more media attention than other is beyond the scope of this paper. Yet, one important factor that likely influences the degree of Twitter attention given to artivists is the degree of news media attention they receive. This is supported by our data () as these three cases score high for news media coverage on Twitter. We know from other studies that news media content constitutes a considerable part of Twitter content (Rogstad, Citation2016). Unsurprisingly, Twitter attention to celebrity artivists eclipses other artivists (Preece, Citation2015).

Table 2. Data descriptives.

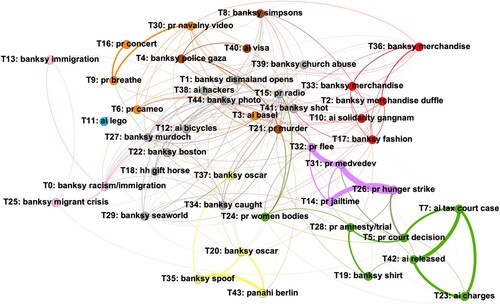

After preparing the data, 45 topicsFootnote5 were requested as more topics did not bring up any new themes and less topics resulted in certain themes being overshadowed by others. All the relationships between topics were then calculated and uploaded into Gephi. After filtering out the weakest ties, rendering the network graph more comprehensible, nine topic clusters emerged from Gephi’s modularity algorithm (scoring a relatively strong 0.582, meaning that the topics in each cluster are relatively well interconnected as opposed to the others). The network graph is presented in , in which each cluster is colored uniquely and the graph layout is plotted according to Gephi’s Force Atlas algorithm.

Political legitimacy through state prosecution

The first cluster that stands out in the network graph (green) mainly conveys the reoccurring theme of prosecution. Five out of seven topics within this cluster display strong ties and address different aspects of the trial cases against Pussy Riot and Ai Weiwei. Topic-23 loads strongly on tweets that address charges laid against Ai Weiwei and his response to it (). Twitter users that posted these tweets share news articles (e.g., Reuters) and stress that the artist has been harassed and has attacked injustices. They frame China’s prosecution of Ai Weiwei as being unjust. Following these, the tweets in which Topic-7 is highly present address developments in the tax evasion case that was held against Ai Weiwei in China. They report on the lost court case which resulted in him having to pay a fine in order to settle his case. Topic-42 revolves around reporting that Ai Weiwei has been released on bail for his tax evasion case.

Table 3. Topics green cluster.

Topic-5 and Topic-28, in turn, address the prosecution that some members of Pussy Riot faced in Russia. Tweets in which these topics load strongly on discuss court developments and decisions. Similar to Ai Weiwei, most Twitter users share and retweet tweets by news media platforms that report on this trial case. In contrast to reporting on Ai Weiwei, however, some of the tweets that mention Pussy Riot include the hashtag ‘#humanrights’, thereby more explicitly speaking out against the Pussy Riot prosecution than is visible for Ai Weiwei. Additionally, our data show that Pussy Riot gains celebrity attention as users react directly to, for example, the British comedian Eddie Izzard (Topic-28). This has undoubtedly contributed to further Twitter attention, although celebrity status in itself is found to be insufficient for political legitimacy (Watts, Citation2020).

There is little normative judgment to be found in this cluster however. Most tweets remain at the level of signaling and sharing developments of the trial cases as they appeared in the news. As newsworthy events often trickle down to social media platforms (Rogstad, Citation2016), it is unsurprising that many Twitter users pay attention to these developments. For these Twitter users, it is not so much the activism of artivists that matters; they show hardly any support or rejection. Instead, the fact that Twitter users mainly retweet, share and talk about the trial cases shows that they particularly care about the course of the prosecution of Ai Weiwei and Pussy Riot.

The tweets that are clustered together in the second, purple cluster are closely related to the first cluster. This relationship is established through one relatively strong tie between Topic-5 from the green cluster that discusses prosecution and Topic-26 from the purple cluster that discusses Pussy Riot’s experiences in jail. The topics in the purple cluster deal more specifically with the experiences of the artivists in relation to their prosecution, instead of the prosecution itself .

Table 4. Topics purple cluster.

These topics all display very strong ties among each other and deal with different developments after two members of Pussy Riot had received their prison sentence. Topic-32 appears mainly in tweets about the two prosecuted Pussy Riot members fled Russia to outrun their prison sentence. Topic-26, subsequently, loads strongly on tweets that highlight the hunger strike of a jailed Pussy Riot member during her prison sentence. Two of the three highest scoring tweets for this topic report on the supposed slave conditions that resulted in the hunger strike protest.

Even though relatively strongly related to the first cluster, no attention to Ai Weiwei’s sentence is apparent. In contrast to Ai Weiwei, however, two members of Pussy Riot spent roughly two years in actual prison. Next to being prosecuted, the severity and conditions of the sentence play a key role in the degree of attention that is given to artivists. This further supports the interpretation of the first cluster: the activism of artivists does not seem to matter for Twitter users, while artivist prosecution and sentence severity more strongly affect when ordinary Twitter users perceive of artivists as political actors. In other words, the perception of artivists as activists, rather than artists, is strongly dependent on the consequences of the artivists’ actions than on the activism itself, at least among our cases.

Artistic legitimacy through artistic recognition

In the third (yellow) cluster, some attention to the artistic side of activist art emerges. The topics in this cluster address the Oscar nomination for Banksy’s film Exit through the Gift Shop and the Golden Bear that Jafar Panahi received at the Berlin Film Festival for one of his films that was smuggled out of Iran (). Yet, most tweets in this cluster merely signal these events. None of them convey personal views as to why the artists are recognized for their artistic products.

Table 5. Topics yellow cluster.

When mentioning Banksy in this context, Twitter users highlight Hollywood actor James Franco singing at the Oscars (Topic-37). This is indicative of the attention that is given to popular culture celebrities and popular culture events on Twitter. Such associations with celebrities add to the celebrity status of Banksy too. Twitter users seemingly include Banksy among popular culture celebrities, while not mentioning the artist explicitly in an artistic (or political) context. Only in Topic-20 do Twitter users mention Banksy along with Lucy Walker, who is a British documentary maker notable for producing societally relevant and critical documentaries. This is, however, done in the context of professional recognition rather than of artistic or political content.

In the case of Jafar Panahi (Topic-43), however, Twitter users address the artist as a dissident filmmaker and director, thereby stressing the political context of Panahi in which the artist faced prosecution for his art in his home country Iran. This is further emphasized by the use of the hashtag ‘#Irandeal’, indicating that Jafar Panahi’s award winning film cannot be seen separately from its political context in Iran. Yet, from reading the tweets, we do not get any information as to why Panahi is considered a dissident artist in Iran or what this Iran deal means.

This cluster, in other words, illustrates that a particular group of Twitter users signal recognition of artists without going into the broader context and without sharing personal views. Instead of raising pressing political issues in which these artivists are involved or which they themselves convey, these users seem to be interested mostly in sharing how artivists are recognized in their respective art fields. As such, the Twitter attention to Banksy and Jafar Panahi conveys internal rather than external artistic legitimacy, as award nominations signal consensus among inner members of an art world and not necessarily among the general public (Baumann, Citation2007). At the same time, this shows that not all Twitter users are interested in the political side to artivism, which means that the degree of audience attention in itself does not guarantee political legitimacy.

Retail activism

The network graph also displays a cluster of weakly tied topics (red) of which the majority pertains to the sale of consumer items derived from Banksy’s artworks. Even though Twitter accounts of companies and media platforms were excluded from our dataset, retweets of – and replies to – such accounts do often occur. Topic-17, for example, loads high on tweets that refer to fashion items based specifically on Banksy’s Balloon Girl artwork (). Topic-36 shows up mostly in tweets about laptop decals and stickers with Banksy’s famous Molotov Guy artwork.

Table 6. Topics red cluster.

This cluster, therefore, includes tweets that announce the availability of consumer items with Banksy designs. The use of hashtags like ‘#fashion’ tells us that such items are fashionable and desired. Only in the second highest scoring tweet for Topic-2 do we encounter a normative judgement: by adding the hashtag ‘#stolen’ the user expresses something of a personal view to the practice of commercializing Banksy. However, this particular tweet also includes the statement that this is ‘Too funny!’, illustrating an ironic attitude towards marketing and selling Banksy consumer items.

Some Twitter users seem to want to express their taste for the artist Banksy, without relating Banksy’s commodified works to the artist’s activism. To that extent, the commodification of art into consumer items such as bags and posters fits well into a widespread consumer culture that affords consumers some room for self-expression (Chouliaraki, Citation2013). Again, however, this type of attention illustrates that a significant proportion of the Twitter users is not interested in the political activism of artivists, suggesting that political legitimacy for artivists is not necessarily related to their artistic products, their activism or their commercial success.

The damaged art of the refugee crisis

Albeit rather small, the three topics within the pink cluster each highlight the geopolitical issue of migrating refugees. The main tweets in each of these topics, however, revolve around a particular project by Banksy in which this political issue is highlighted, even though Pussy Riot and Ai Weiwei both have addressed the refugee crisis in their work during the period of data collection.

Looking more closely at the tweets themselves, we find that two out of the three topics mainly address the damaging of Banksy’s murals rather than the issue of refugees depicted in these murals. Topic-0 is mainly present in tweets that signal the destruction of Banksy’s immigration mural in UK town Clacton-on-Sea (). Similarly, Topic-13 loads high on tweets that address how the same Banksy mural was scrubbed by local authorities. Even though Twitter users explicitly refer to the mural as confronting racism (Topic-0) and an anti-immigration rhetoric (Topic-13), attention in these tweets mainly goes out to what happened to the artworks instead of what they stand for. Only in Topic-25, there is some room for reflection on the refugee crisis. Some tweets highlight the entrepreneurial spirit of migrants in a Calais migrant camp who charge people to view the Banksy mural of Steve Jobs as a refugee.

Table 7. Topics pink cluster.

By bringing these Banksy murals to attention and relating them to the global crisis of (Syrian) refugees and immigration, Twitter users show that this crisis is a theme that deserves attention. The nature of attention given to Banksy, however, is similar to Pussy Riot and Ai Weiwei in the context of their prosecution. Most tweets do not include personal views with regards to refugees and gravitate mostly towards attention to what happened to Banksy’s artworks. Yet, the acts of mentioning, spreading and repeating the global refugee crisis tells us it is a theme many Twitter users deem important. Moreover, these tweets indicate that Twitter users accept Banksy as someone who is allowed to raise awareness for this subject.

The ‘other’-category: signaling individual projects.

The remaining clusters (gray, orange, blue, brown) consist of topics that do not seem to convey any clearly related themes (Appendix).Footnote6 In the largest cluster (gray), several topics are grouped together even though they convey very different themes on the topic level. The smallest cluster (blue) consists of only one topic pertaining to Ai Weiwei’s Lego project. The topics in both clusters do not exhibit any strong ties. They pertain mostly to smaller projects relating to the cases, such as Ai Weiwei’s bicycle project (Topic-12), Hans Haacke’s gift horse (Topic-18) and Banksy’s Dismaland (Topic-1). Likewise, the remaining two clusters consist of seemingly unrelated projects, dealing mainly with different Pussy Riot projects (orange) or projects by different cases without any clear relation between them (brown). This suggests that these clusters constitute a residual category consisting of topics that gain less interest.

Conclusion

In this paper we studied the degree and type of attention media audiences give to artivists using Twitter. Our findings show that the Twitter attention that artivists receive has little to do with the political cause they respectively aim to advance, at least for the cases we selected. Instead, the majority of attention to – and interest in – artivism on Twitter can be characterized as focusing on consequences rather than content. Specifically, this entails a strong emphasis on state prosecution, media-centric artistic recognition and consumerism. Thus, artivists achieve political legitimacy not for their activism but primarily for the consequences of their activism.

These findings provide an important contribution to studies on social engagement and activism in the arts. The artivists in our sample indeed receive little attention for their art other than when recognition by the inner members of an art field (Baumann, Citation2007) is emphasized. Instead, artivists primarily receive Twitter attention for social rather than artistic matters as the literature suggests (e.g., Bishop, Citation2012). In fact, Twitter users in our sample rarely mention art and political activism together. They discuss artivists as either artists, for example through the topic of artistic recognition, or as political actors, for example through the topic of state prosecution. As such, the degree of audience attention does not guarantee political legitimacy. Although the legitimacy cross-over through mainstream attention enables artivists to engage in activism, the social change that artivists seek is strikingly lost in the process.

By focusing on the consequences of art activism, artivism affords Twitter users to display solidarity with the suffering artivist. This contributes to research that suggests that Western media audiences seek to display solidarity as a form of cosmopolitan self-expression (Chouliaraki, Citation2013). Twitter, as a social media platform, lends itself greatly for such practices (Hogan, Citation2010) and Pussy Riot and Ai Weiwei especially constitute the cosmopolitan ‘other’ as they originate from countries that score relatively low on freedom. This form of solidarity, however, extends only as far as mainstream news media attention goes. The other artivist who suffered state repression – Jafar Panahi – remains largely invisibly in the topic model, which means that the display of solidarity by Twitter users follows widespread news media attention instead of the actual suffering artivist.

And yet, both popularity and the lack thereof, at least as far as this public extends to Twitter users, result in little impact of the artivists and their causes. Highly popular artivists such as Banksy, Pussy Riot and Ai Weiwei see their political agenda being overshadowed by attention that barely scratches the surface of their causes, while less well-known artivists such as Jafar Panahi, Jonas Staal and Hans Haacke receive virtually no attention at all. As an important resource for political legitimacy, then, audience attention takes the form of a Matthew Effect for artivists: attention leads to more attention. Political legitimacy for artivists comes at the cost of their activist intent being largely ignored.

These conclusions, however, should be taken with some caution. First, even though Twitter provides an empirical window to study everyday discussions by the broader public, our conclusions only extend, strictly speaking, to the Twittersphere. Second, and partly due to the short nature of tweets, Twitter users remain mostly at the level of signaling particular events. Yet, Twitter constitutes a communicative space through which people in contemporary democracies actively engage with politics (Vromen et al., Citation2015). For artivists to achieve any impact beyond the art field, receiving attention on platforms such as Twitter is indispensable. Third, we purposively selected diverse cases to explore the degree and type of attention media audiences give to artivists. Hence, it is not our intention to statistically generalize but instead to provide a broad interpretative analysis of (English-language) media audience attention to artivists. Future research might build on our findings by zooming in on, for example, Russian or Chinese dissident artists, by studying the reception in their country of origin, or the interplay between domestic and international reception. Interestingly, Ai Weiwei, Pussy Riot and Jafar Panahi have all been framed as not being loyal to their country of origin by those in power, i.e., as a dissident artist (Hancox, Citation2014), as part of a global elite focusing on the Western import topic of gender (Gapova, Citation2015), and as a ‘festival filmmaker’ catering for Western tastes (Rahbaran, Citation2012), respectively.

Finally, by combining topic modeling and semantic network analysis, we bridged the methodological polarization between quantitative and qualitative analysis and helped to better study meaning structures. Admittedly, the analysis is somewhat biased towards frequently-occurring textual content in the data. Therefore, topic modeling falls short to trace out smaller differences within themes as well as those artivists who have received considerably less attention. Yet, the disproportionate amount of attention to Ai Weiwei, Banksy and Pussy Riot shows that Twitter users mainly focus on that which is popular, trending and widely debated in society. Future research might examine the comparative impact of artivists’ media politics on (type of) attention (see Strafella & Berg, Citation2015). Furthermore, the strength of topic modeling – allowing for an unsupervised approach and letting an algorithm categorize textual data – is also a weakness. The algorithm does not know how many topics there are within texts and there is no thorough statistical test available to assess the model’s goodness of fit. The researcher ultimately must interpret the best fit in terms of the number of topics. At the same time, this gives researchers more interpretative control over their data without the black-box of complex and automated algorithmic models.

Supplement_Material.docx

Download MS Word (23.5 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Frank Weij

Frank Weij was a PhD candidate and lecturer at the Erasmus School of History, Culture and Communication (Erasmus University Rotterdam) until 2020, after which he has been pursuing a career as a data scientist. His dissertation involves the relationship between the arts and political activism.

Pauwke Berkers

Pauwke Berkers is full professor Sociology of Popular Music and head of department Arts and Culture Studies at the Erasmus School of History, Culture and Communication (Erasmus University Rotterdam). His research focuses on music in relation to issues of inclusion and resilience.

Notes

1 Derived from our Twitter dataset.

2 Python was used to clean the data.

3 We assessed potential spam accounts individually and manually.

4 Words like (demonstrative) pronouns occur often in the data while not conveying much meaning. They are therefore excluded.

5 The full topic-solution is too large to provide within the format of this paper (available on request).

6 Following DiMaggio et al. (Citation2013), although no topic solution is perfect, the researcher should look for the most optimal topic model through which the data can be viewed most clearly.

References

- Adams, J. (2002). Art in social movements. Sociological Forum, 17(1), 21–56. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1014589422758

- Bail, C. A. (2014). The cultural environment: Measuring culture with big data. Theory and Society, 43(3–4), 465–482. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11186-014-9216-5

- Baumann, S. (2007). A general theory of artistic legitimation. Poetics, 35(1), 47–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poetic.2006.06.001

- Bishop, C. (2012). Artificial hells: Participatory art and the politics of spectatorship. Verso.

- Bourdieu, P. (1993). The field of cultural production. Columbia University Press.

- Bourdieu, P., & Haacke, H. (1995). Free exchange. Polity Press.

- boyd, d., Golder, S., & Lotan, G. (2010). Tweet, tweet, retweet: Conversational aspects of retweeting on Twitter. HICSS-43. IEEE: Kauai, HI.

- Brassett, J. (2009). British irony, global justice: A pragmatic reading of Chris Brown, Banksy and Ricky Gervais. Review of International Studies, 35(1), 219–245. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210509008390

- Chouliaraki, L. (2013). The ironic spectator: Solidarity in the age of post-humanitarianism. Polity Press.

- Cottle, S. (2008). Reporting demonstrations: The changing media politics of dissent. Media, Culture & Society, 30(6), 853–872. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443708096097

- Dahlberg, L. (2007). Rethinking the fragmentation of the cyberpublic. New Media & Society, 9(5), 827–847. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444807081228

- Danko, D. (2018). Artivism and the spirit of avant-garde art. In V. F. Alexander, S. Hägg, S. Häyrynen, & E. Sevänen (Eds.), Art and the challenge of markets volume 2 (pp. 235–261). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Der Spiegel. (2011). Ai Weiwei, ‘Shame on me’. Retrieved February 21, 2020. from https://www.spiegel.de/international/world/ai-weiwei-shame-on-me-a-799302.html

- DiMaggio, P., Nag, M., & Blei, D. (2013). Exploiting affinities between topic modeling and the sociological perspective on culture. Poetics, 41(6), 570–606. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poetic.2013.08.004

- Dreiger, P. (2013). Semantic network analysis as a method for visual text analytics. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 79, 4–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.05.053

- Edelmann, A., & Mohr, J. W. (2018). Formal studies of culture. Poetics, 68, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poetic.2018.05.003

- Ekman, J., & Amnå, E. (2012). Political participation and civic engagement: Towards a new typology. Human Affairs, 22(3), 283–300. https://doi.org/10.2478/s13374-012-0024-1

- Evans, H. K., Smith, S., Gonzales, A., & Strouse, K. (2017). Mudslinging on Twitter during the 2014 election. Social Media+ Society, 3(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305117704408

- Freedom House. (2016). Freedom in the world report 2016. Retrieved May 4, 2017, from https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/freedom-world-2016

- Gapova, E. (2015). Becoming visible in the digital age: The class and media dimensions of the Pussy Riot affair. Feminist Media Studies, 15(1), 18–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2015.988390

- Gerring, J. (2008). Case selection for case-study analysis: Qualitative and quantitative techniques. In The Oxford handbook of political methodology.

- Hancox, S. (2014). Art, activism and the geopolitical imagination: Ai Weiwei’s Sunflower Seeds. Journal of Media Practice, 12(3), 279–290. https://doi.org/10.1386/jmpr.12.3.279_1

- Harlow, S., & Benbrook, A. (2019). How# Blacklivesmatter: Exploring the role of hip-hop celebrities in constructing racial identity on Black Twitter. Information, Communication & Society, 22(3), 352–368. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2017.1386705

- Hogan, B. (2010). The presentation of self in an age of social media. Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society, 30(6), 377–386. https://doi.org/10.1177/0270467610385893

- Howard, P. N., & Hussain, M. M. (2011). The role of digital media. Journal of Democracy, 22(3), 35–48. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2011.0041

- Karvonen, L. (2010). The personalization of politics: A study of democracies. ECPR Press.

- Kranenberg, A. (2007). Kunst of bedreiging: gedenkplaatsen voor Wilders. Retrieved February 21, 2020, from https://www.volkskrant.nl/nieuws-achtergrond/kunst-of-bedreiging-gedenkplaatsen-voor-wilders~be0767ec/

- Kriesi, H., Lavenex, S., Esser, F., Matthes, J., Bühlmann, M., & Bochsler, D. (2013). Democracy in the age of globalization and mediatization. Palgrave.

- Loader, B. D., Vromen, A., & Xenos, M. A. (2016). Performing for the young networked citizen? Celebrity politics, social networking and the political engagement of young people. Media, Culture & Society, 38(3), 400–419. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443715608261

- Mayer-Schonberger, V., & Cukier, K. (2013). Big data: A revolution that will transform the way we live, work, and think. Houghton Mifflin.

- Mohr, J. W., & Bogdanov, P. (2013). Introduction – topic models: what They are and why they matter. Poetics, 41(6), 545–569. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poetic.2013.10.001

- Mortensen, M. (2017). Constructing, confirming, and contesting icons: The Alan Kurdy imagery appropriated by #humanitywashedashore, Ai Weiwei, and Charlie Hebdo. Media, Culture & Society, 39(8), 1142–1161. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443717725572

- Neumayer, C., & Svensson, J. (2016). Activism and radical politics in the digital age: Towards a typology. Convergence, 22(1), 131–146. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856514553395

- Norris, P. (2002). Democratic phoenix: Reinventing political activism. Cambridge University Press.

- Preece, C. (2015). The authentic celebrity brand: Unpacking Ai Weiwei’s celebritised selves. Journal of Marketing Management, 31(5–6), 616–645. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2014.1000362

- Rahbaran, S. (2012). An interview with Jafar Panahi. Wasafiri, 27(3), 5–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/02690055.2012.687597

- Riccioni, I., & Halley, J. A. (2021). Performance as social resistance: Pussy Riot as a feminist avant-garde. Theory, Culture & Society, 38(7–8), 211–231. https://doi.org/10.1177/02632764211032726

- Rogstad, I. (2016). Is Twitter just rehashing? Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 13(2), 142–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/19331681.2016.1160263

- Roussel, V., & Lechaux, B. (2010). Voicing dissent: American artists and the war on Iraq. Routledge.

- Simons, J. (2003). Popular culture and mediated politics. In J. Corner & D. Pels (Eds.), Media and the restyling of politics (pp. 171–189). Sage.

- Sloan, L., Morgan, J., Burnap, P., & Williams, M. (2015). Who Tweets? Deriving the demographic characteristics of age, occupation and social class from Twitter user meta-data. PLoS ONE, 10(3), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0115545

- Strafella, G., & Berg, D. (2015). “Twitter bodhisattva”: Ai Weiwei’s media politics. Asian Studies Review, 39(1), 138–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/10357823.2014.990357

- Street, J. (2012). Music and politics. Polity Press.

- Vromen, A., Xenos, M. A., & Loader, B. (2015). Young people, social media and connective action. Journal of Youth Studies, 18(1), 80–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2014.933198

- Watts, E. (2020). ‘Russell Brand’s a joke right?’ Contrasting perceptions of Russell Brand’s legitimacy in grassroots and electoral politics. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 23(1), 35–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367549419861627

- Weij, F., & Berkers, P. (2019). The politics of musical activism: Western YouTube reception of Pussy Riot’s punk performances. Convergence, 25(2), 287–306. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856517706493

- Wilkinson, D., & Thelwall, M. (2012). Trending Twitter topics in English: An international comparison. ASIS&T, 63(8), 1631–1646. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.22713

- Wonneberger, A., Hellsten, I. R., & Jacobs, S. H. (2020). Hashtag activism and the configuration of counterpublics. Information, Communication & Society, 24(12), 1694–1711. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2020.1720770

- Zelditch, M. (2001). Processes of legitimation. Social Psychology Quarterly, 64(4), 4. https://doi.org/10.2307/3090147