ABSTRACT

This article examines the reception and dissemination of ‘malign information influence’ (MII) in a liberal democracy; information sponsored by authoritarian regimes or other hostile actors and projected through international broadcasting outlets across borders. The study contributes to the scarce research on the reception of narratives transmitted by the Russian state-supported media platforms RT and Sputnik, exposing characteristics, political attitudes, and sharing behaviors of RT/Sputnik consumers. A nationwide, representative survey (n: 3033) from November 2020 revealed a surprisingly high number of Swedish RT/Sputnik consumers (7%), with an overrepresentation of young, men and supports of non-parliamentarian parties and the right wing, nationalist Sweden Democratic Party. These consumers are somewhat more willing than non-consumers to disseminate news on social media and in real life despite being distrustful of the sources. The findings strengthen previous research in demonstrating the attractiveness of identity grievance narratives among alternative media consumers, yet the results show that RT/Sputnik consumers also aligned with narratives that contrasts with national security policy. They state less trust in politicians, institutions, the media, news, and journalism, yet are comparatively prone to share unreliable or untrue news content on social media and in real life. The analysis thus identified a section of media consumers who can function as vehicles for the dissemination of MII. The article contributes to the under-researched problem of the potential of MII to take root and provides a basis for future qualitative research that can refine and provide nuance to the knowledge of reception of MII.

In recent years, concerns have arisen regarding the use of information to manipulate attitudes and behaviors across state borders, with the Russian interference in the 2016 US election as the primary example (Hall Jamieson, Citation2018). The exploitation of new technologies and international broadcasting to project messages that can harm democratic societies by undermining democracy, spurring polarization, or even damaging national security, has been widely acknowledged. Previous research has primarily focused on content (Ramsay & Robertshaw, Citation2019), spread (Guess et al., Citation2019), and countermeasures (Bjola & Papandakis, Citation2019), whereas the consequences require further study. This article contributes by scrutinizing audience reception of the Russian state-sponsored media platforms RT and Sputnik in Sweden.

Leaderships – mainly autocratic states and antagonistic actors – have placed great effort into embedding information influence in seemingly normal and attractive news reporting, projected through channels such as CCTV-N and RT (Rawnsley, Citation2015; Turcsanyi & Kachlikova, Citation2020, p. 72). Such modern information influence activities differ from traditional propaganda in that actors use new channels and normal media consumption patterns to reach citizens in other societies. This article adopts the label ‘malign information influence’ (MII) to denote information sponsored by authoritarian regimes or other hostile actors and projected through international broadcasting to inflict harm upon others. This kind of international broadcasting blurs the lines between public diplomacy, propaganda, and traditional journalism (Rawnsley, Citation2015, p. 274; Rawnsley, Citation2016; Wright et al., Citation2020). Such communication is often made attractive through affective narratives that build on, but is not restricted to, disinformation (Turcsanyi & Kachlikova, Citation2020; Eberle & Daniel, Citation2019; Crilley & Chatterje-Doody, Citation2020).

In a study of RT’s organizational behavior, Elswah and Howard (Citation2020, p. 642) highlight the need for knowledge on those watching RT, presumably an audience with antiestablishment and anti-Western views. Crilley et al. (Citation2022) contributed through a study of RT’s Twitter followers, identifying a heterogeneity of followers that do not engage with the message content to any substantial degree. Yet, they call for additional research on consumption and engagement on platforms beyond Twitter. This article takes a step towards filling this gap. It adds through a comprehensive approach that exposes not only the number of consumers but also audience characteristics, their willingness to disseminate unreliable news and MII and alignment with message content. Key findings involve the identification of a surprisingly high number of Swedish RT/Sputnik consumers, with an overrepresentation of young, men and supporters of non-parliamentarian parties and the right wing, nationalist Sweden Democratic Party. These consumers are somewhat more willing than non-consumers to disseminate news despite being distrustful of the sources. The findings strengthen previous research in demonstrating the attractiveness of identity grievance narratives. In addition, RT/Sputnik consumers were more prone than non-consumers to align with narratives that contrast with national security policy.

Alternative media, trust, and MII

Research indicates that there is a link between low trust in institutions and the media, consumption of alternative media (often linked to foreign and right-wing nationalist strategies) and use and spread of disinformation (Bennett & Livingston, Citation2018, p. 122, 128). Disinformation seems to be spread mainly by a small minority who actively and regularly engage with sources of unreliable information, whereas most media users encounter disinformation indirectly in regular news media or social media networks (Glenski et al., Citation2020, p. 47; Lecheler & Egelhofer, Citation2021, p. 324–325). In a study on German voters, Zimmermann and Kohring (Citation2020) found that media consumers with low trust in institutions and mainstream media tend to turn to alternative and nonreliable sources of information (Zimmermann & Kohring, Citation2020, p. 227, 231). Scholars have identified a strong criticism of mainstream media on the part of alternative media (Cushion, Citation2021, pp. 15–18), which means that consumers can find fuel for their skepticism of mainstream media by consuming alternative media.

Holt et al. (Citation2019, 862) propose that a central defining aspect of all alternative media, irrespective of ideological standpoint, is ‘a proclaimed and/or (self-) perceived corrective, opposing the overall tendency of public discourse emanating from what is perceived as the dominant mainstream media in a given system’. Recent research positions anti-mainstream right-wing alternative media between journalism and political activism (Mayerhöffer & Heft, Citation2021). Schwarzenegger (Citation2021) found that the ideological affiliations of consumers of alternative media span from left-wing to right-wing but coalesce in their anti-establishment and anti-system sentiments and feelings of being more critical, informed, and knowledgeable than the norm. Some use alternative media to feel accepted in their anti-establishment opinions and be part of a community of likeminded people. Others use it to gain complementary perspectives to mainstream media that feels too sensational, incomplete, and obscurely one-sided. They share a skepticism against the state and the media in general, often including alternative news sources (Schwarzenegger, Citation2021, pp. 104–6). A study on Norwegian self-professed immigration critics showed that participants felt like they alone understood the severity of the country’s ‘immigration crisis’. Having lost trust in the establishment’s competence and integrity, the alarmed participants turned to alternative, immigration critical media (Thorbjørnsrud & Figenschou, Citation2020, pp. 8–13).

Alternative media discourse and MII: the Swedish case

Information influence is often tailored to different target groups (Linvill & Warren, Citation2020) but also depends on national context (Deverell et al., Citation2020). Most research on information influence has been carried out in the US setting, and additional studies are needed to uncover how it is received in other contexts (Tucker et al., Citation2018, p. 61). Humprecht’s (Citation2019) analysis of four national settings, which finds disinformation to mirror national information environments, is a valuable contribution in this regard. This article turns to Sweden, which has been a key target of Russian MII. A cross-national study of RT and Sputnik coverage on the UK, the USA, France, Germany, Sweden, Italy, and Ukraine, exposed that coverage of Sweden was the narrowest, 88% of the coverage focusing on political dysfunction (Ramsay & Robertshaw, Citation2019, p. 80). Sweden has also been subjected to MII being framed as a bad example, with the aim of spurring right-wing, anti-liberal, anti-migrant feelings (Colliver et al., Citation2018).

RT and Sputnik broadcasting in Sweden corresponds closely with the Swedish far-right discourse on alternative media platforms, which is critical of the establishment and cultivates in-group/out-group differences (Arceneaux et al., Citation2021, p. 2). Heft et al. (Citation2019) found that the supply of and demand for alternative far-right-wing media platforms is particularly high in Sweden and Germany, supposedly due to a lower representation of right-wing positions in the political and legacy media sphere. Furthermore, there is substantial concern with MII in Sweden (Wagnsson, Citation2020). Against this background, analysis of the reception of MII in Sweden is highly pertinent.

Analytical design

The first part of the analysis scrutinizes the scale of RT/Sputnik consumption, characteristics of consumers, including trust in political institutions, politicians, news, journalism, and different media outlets. It also investigates users’ media consumption patterns and willingness to spread unreliable news, including RT and Sputnik, on social media and in real life. While in the past, media research looked upon ‘reach’ as news media organizations’ capacity to access large audiences through broadcasting/publishing, the audience has now become a tool for further diffusion of information (Mejias & Vokuev, Citation2017). Given the significant role of the audience in the modern media ecology, this article explores not only the characteristics and attitudes of MII consumers but also their inclination to spread MII further in society. The impact of MII can increase when it is echoed in mainstream or alternative media, or spread on social media, reaching audiences who do not engage directly with foreign media platforms (Nisbet & Kamenchuk, Citation2019, p. 75). The idea of information influence as reinforcing and normalizing existing attitudes, rather than radically changing opinions, is common (Peisakhin & Rozenas, Citation2018).

The second part of the analysis explores alignment/non-alignment with message content. It targets two types of content: propositions reflecting identity grievance and propositions linked to national security.

Identity-grievance campaigns that exploit perceptions of political, economic, religious, or cultural wrongs are common to state-sponsored disinformation campaigns (Nisbet & Kamenchuk, Citation2019, p. 67; 76–77). A key aim is to nurture discord and polarization in the target society (Tucker et al., Citation2018). Cultivation of negative feelings is particularly efficient in undermining cohesion. News stories that seek to evoke emotions are more likely to be passed on to others (Lewandowsky et al., Citation2012, p. 108) and politicians within populist parties exploit the power of negative emotions more frequently than other politicians do (Engesser et al., Citation2017, p. 1285). Identity grievance often evolves around negative ‘others’, spurs ‘affective polarization’ and disrupts civil public debate (Wojcieszak & Warner, Citation2020, p. 2; Hutchens et al., Citation2019, p. 358). Targeting identity is key to the cultivation of negative feelings that can elicit conflicts between people holding different identities (Hameleers et al., Citation2017; Crilley & Chatterje-Doody, Citation2020). MII that draws upon identity grievance is likely to be particularly appealing to consumers of alternative media, including RT and Sputnik. Müller and Schulz (Citation2021) exposed that consumers of German altmedia shared feelings of personal relative deprivation and populist right-wing views. This resonates with Zimmermann and Kohring (Citation2020, p. 227), who found consumers of less reliable news generally more dissatisfied with and distrustful of the political system and prone to fringe political parties. We, therefore, anticipate that consumers of MII will be more likely than non-consumers to align with identity grievance narratives.

MII can also focus on issues linked to national security. Such narratives can work indirectly and long term, by undermining democracy and cohesion and the will to defend the country. They can be directly aimed at influencing the audience’s views on national security policy in a certain direction, such as when the Russian state sponsored media platform Sputnik reproach Nordic countries for collaborating with NATO, setting up sanctions against Russia, resisting Nord Stream 2 or displaying ‘Russophobia’ (Deverell et al., Citation2020). MII can even pave the way for foreign invasion (Golovchenko et al., Citation2018, p. 976). Russian MII that contradicts national security policy might gain some resonance in Europe, in particular if cultivating EU negativism, anti-Americanism and negative feelings towards NATO (Keating & Kaczmarska, Citation2017, pp. 14–16). In Sweden, the left and right extremes have traditionally shared opposition to the EU and opinion on NATO is partisan. Yet, we still consider it unlikely that consumers of MII align with narratives that can undermine national security, given the seriousness of the matter and the relatively large consensus on national security policy. Furthermore, public concern and vigilance to MII as a security threat is likely to have risen in Europe, in parallel with institutional development, such as the creation of NATO Strategic Communication Centre of Excellence and the EU’s East StratCom Task Force.

In conclusion, we theorize that MII consumers will align more than non-consumers with identity-grievance narratives, but they will not align more than non-consumers with narratives that contradicts with and can potentially undermine national security. To probe these claims, respondents were presented with propositions that reflect RT/Sputnik narratives on identity grievance and national security (see further below).

Methodology

Selection of sites for malign information influence

The selection of RT (formerly Russia Today) and Sputnik as sites of MII is justified given their capacities as major media outlets backed by the Russian government and intended for the projection of information influence. RT has been labeled ‘one of the most important organizations in the global political economy of disinformation’ and characterized as an ‘opportunist channel that is used as an instrument of state defense policy to meddle in the politics of other states’ (Elswah & Howard, Citation2020). Sputnik was launched in 2014, based on the government-owned radio station Voice of Russia, and owned by Rossiya Segodnya, which was created by presidential decree in 2013 to spread news abroad (Groll, Citation2014). Scholars have demonstrated how these state-backed media agencies slander politicians, politics, and societies in Europe and the USA, and how individuals and Western news agencies reproduce their narratives (Khaldarova & Pantti, Citation2016; Watanabe, Citation2018).

RT and Sputnik written articles are available to Swedes online and on social media (such as Twitter and Facebook). The broadcasting version of RT is available from its home page and on cable TV and YouTube. RT and Sputnik employ similar strategies, aiming to destabilize other states (Gérard et al., Citation2020). Ramsay and Robertshaw (Citation2019) identified strong convergence between their narrative themes on European states and NATO, seen in the strong focus on political division, dysfunction, and negative consequences of immigration. The platforms’ written articles differ somewhat, Sputnik for instance re-printing more articles from other outlets (Ramsay & Robertshaw, Citation2019, p. 18). Sputnik publishes more articles on Sweden than RT. Yet, the content of articles on Sweden is very similar, habitually written in a critical tone, often quoting angry or scornful Swedish social media posts to strengthen the message. Some articles are almost identical, such as ‘Backlash as Swedish National Museum slaps racism and sexism warnings on CLASSIC ART’ (RT) and ‘Uproar as Swedish National Museum Adds ‘Insane’ Warnings to Classic Art’ (Sputnik) that were published in both outlets on the same date (June 21, 2021).

The survey

The survey was conducted 3–11 November 2020. The participants were recruited by the research agency Novus, from a randomly selected web panel (no opportunity for self-recruitment) and consist of a representative random sample of the population. The response rate was 65%, with a total number of 3033 people (out of 4660 invited) participating, aged between 18 and 89. The survey was conducted online, with participants receiving a link to the survey by email. The age distribution of the participants was fairly similar to that of the total population, with a slight under-representation of the youngest age groups 18–29 and 30–49 years. and slight overrepresentation of the older age groups 50–64 and 65–79 years, caused by non response. Weights have been applied to compensate for the disproportionate stratification. There are no indications of the non-response rate skewing the results.

Respondents were asked questions about media consumption, centering on the consumption of traditional national media, national alternative (populist) media (Samhällsnytt, Fria tider, Nyheter idag), traditional foreign media (CNN, BB, Sky news) and RT and Sputnik. They were also asked about the reason for consumption. The next set of questions focused on trust and mapped respondents’ sharing behavior.

Respondents were subsequently presented with a set of 15 propositions that reflect RT/Sputnik news reporting on identity grievance and national security. Each proposition corresponds to a Russian narrative strategy identified in systematic research (Wagnsson & Barzanje, Citation2021; Deverell et al., Citation2020; Hellman, Citation2021; Hoyle et al, Citationin press). The first set of propositions corresponds to two strategies labelled suppression and destruction that often serve to reinforce one another. Suppression work primarily through instigating conflict by focusing on moral values, whereas destruction target material capabilities and political and institutional leadership (Wagnsson & Barzanje, Citation2021, p. 250). Both exploit feelings of identity-grievance and can potentially cultivate anti-liberal views and undermine societal cohesion and trust. A reliability statistics analysis displayed a Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.732, which indicates a good level of internal consistency for this set of propositions.

The second set of 11 propositions mirror Russian reporting that contrasts with and can potentially undermine Swedish security. They mirror a strategy identified in previous research labelled direction (Wagnsson & Barzanje, Citation2021, p. 251) that aims to make the audience align with the narrator on specific issues. In the present article, the direction is about making the audience taking positions that runs contrary to official Swedish security policy. The propositions focus on Russophobia, practices of the Armed Forces, co-operation with NATO, Sweden’s inability to co-operate with other countries, military resolve and support for national military defense capacity. A reliability statistics analysis displayed a Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.782, which indicates a good level of internal consistency for this set of propositions.

Results

RT/Sputnik consumers: demographics, political party, trust

Results show that 7% of the respondents (n: 212) consume RT/Sputnik on some occasion, and 2% declare a weekly or monthly consumption. Henceforth, ‘RT/Sputnik users’ denotes the total number of consumers (7%), regardless of frequency of consumption, since the n-value is too low for reliable analyses of differences among frequent and sporadic users. Given the small number of consumers, findings on in-group variances among RT/Sputnik users need also to be treated with some caution.

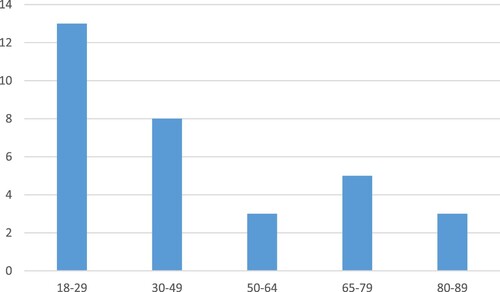

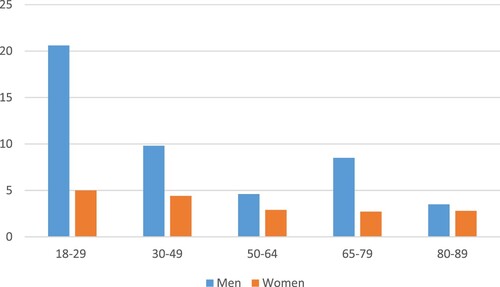

The analysis of demographics (gender, age, education, income, place of residence) showed some statistically significant differences between users and non-users (see supplementary information file for details on significant differences). The most noticeable finding is that men and the youngest are overrepresented among users. Almost three out of four RT/Sputnik consumers are males and although RT/Sputnik consumers exist within all age cohorts, the youngest (18–29 years) are overrepresented. Strikingly, 13% of those aged 18–29 consume Sputnik. Furthermore, 20, 6% of men aged 18–29 and 10, 8% of men aged 30–49 report consumption of RT/Sputnik. and show the consumption of RT/Sputnik by age and gender.

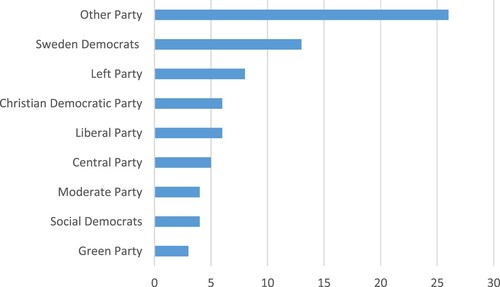

Furthermore, RT/Sputnik users stand out regarding political party preference. Followers of non-parliamentarian parties, in particular, are overrepresented among RT/Sputnik users, as are followers of the Sweden Democrats, whereas partisans of two large traditional parties with a long history in the Swedish Parliament – the Moderate Party and the Social Democrats – are underrepresented (for statistically significant differences between users and non-users, see supplementary information file). shows RT/Sputnik consumption among followers of different parties. It demonstrates that the consumption of RT/Sputnik is more common among followers of non-parliamentarian parties, the right-wing national conservatist party the Sweden Democrats and the Left Party, whereas it is less common among followers of traditional and centrist parties.

Results further show that RT/Sputnik are more skeptical than non-users to all kinds of media and journalism, except Swedish alternative media, RT and Sputnik. This said, RT/Sputnik consumers consider Swedish traditional media, public service, and Swedish journalists more trustworthy than RT/Sputnik. RT/Sputnik consumption also corresponds with lower trust in Swedish politicians and in all key governmental institutions included in the survey: the police, the Public Health Agency, the Swedish Civil Contingencies Agency. The only exception is the lack of differences in trust in the Armed Forces among consumers and non-consumers ().

Table 1. Trust in politicians, institutions, news and journalism.

RT/Sputnik consumers: news consumption and dissemination

RT/Sputnik consumers stand out with a very high reported consumption of all kinds of news media. As much as 95% consume foreign traditional media such as CNN, BBC, and Sky News (65% for the total number of respondents) and 82% consume national alternative media (28% for the total number of respondents). Their monthly consumption of traditional Swedish media (97%) is on pair with the consumption of the total number of respondents, and they only report a slightly lower daily consumption.

The next step examined the potential for the spread of RT/Sputnik news. It should be noted that it is rare that RT/Sputnik consumers report sharing RT/Sputnik news content. Nevertheless, they are more prone than non-consumers to spread all kinds of news, including Sputnik and RT, on social media. RT/Sputnik users are also more prone to discuss news with family and friends in real life, except for traditional Swedish media. Although RT/Sputnik consumers very rarely report sharing unreliable news, they are somewhat more inclined than non-consumers to affirm that they spread news without knowing their origins and disseminate news even when suspecting that they might not be true. They are also slightly more prone to concur with the statement that they do not trust any news ( and ).

Table 2. Sharing behavior.

Table 3. Trust in news and sharing of unreliable news.

RT/Sputnik users: alignment with malign information influence

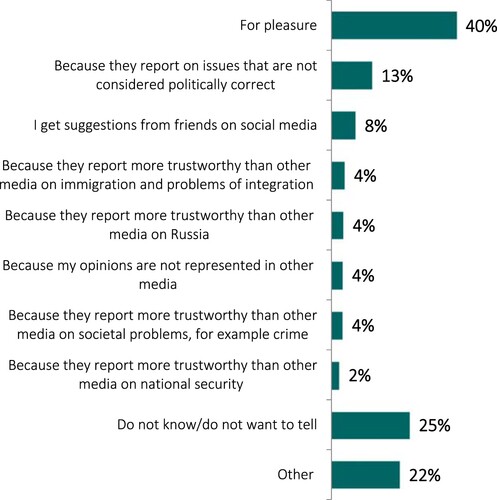

The final step examines what kind of messaging RT/Sputnik users align with, based on the assumption that consumers will be more likely to spread content that they approve of. To begin with, when asked about incentives for RT/Sputnik consumption, the most frequent answer (40%) was ‘for pleasure’. Yet, for roughly a third of the respondents, the content of news was a reason for turning to RT/Sputnik. These respondents referred to different incentives, including RT/Sputnik reporting on issues not considered politically correct by other media, their views not being represented in other media, or that RT/Sputnik report more trustworthy on societal problems, Russia, or national security. Almost half of the respondents did not want to tell or referred to other reasons ().

The analysis of results further shows that the expectation that RT/Sputnik consumers will align more than non-consumers with identity-grievance messaging holds true. The results show that RT/Sputnik consumers agree significantly more than non-users with 14 out of 15 identity-grievance propositions. The only proposition that did not yield any significant differences between users and non-users was ‘Countryside residents are easily forgotten’ ().

Table 4. Alignment with RT/Sputnik messaging: Identity grievance.

We further expected that RT/Sputnik consumers would not align more than non-consumers with messaging that could potentially harm national security. This turned out to be mostly wrong. Users aligned more than non-users with all RT/Sputnik’s negative propositions on the Swedish Armed forces and Sweden’s inability to cooperate with other countries. Furthermore, they converged more with the proposition that Sweden exaggerates the threat from Russia and is unnecessarily critical to Russia. However, interestingly, they did not align more than non-consumers with the RT/Sputnik negative narrative on NATO. There were no significant differences between consumers and non-consumers as regard Swedish cooperation with NATO or Sweden joining NATO. Furthermore, consumers demonstrate stronger support than non-consumers of a strong national defense and of young people serving in the Armed Forces ().

Table 5. Alignment with RT/Sputnik messaging: National security.

Discussion

RT and Sputnik are English-language news outlets that are likely to be unknown to most Swedish media consumers. It is, therefore, surprising that as much as 7% of respondents reported that they consume RT and/or Sputnik on some occasion. Furthermore, in contrast to Crilley et al.’s (Citation2022) finding that RT’s Twitter followers rarely engage with the content, the results of this study demonstrate that RT/Sputnik news consumers align more than non-users with the content. Differences among consumers and non-consumers are small, sometimes minor, but nevertheless identifiable on almost every factor measured.

First, the results demonstrate that a large share of consumers are drawn to RT/Sputnik because they find these news platforms entertaining, yet many also stated incentives that reflect identity grievance. This supports previous research findings indicating that MII packaged through international broadcasting is made attractive through entertaining features and affective narratives (Turcsanyi & Kachlikova, Citation2020; Eberle & Daniel, Citation2019). Moreover, in line with our expectations, RT/Sputnik consumers aligned with these platforms’ identity grievance messaging more than non-consumers did. This supports previous research on the power of messaging exploiting identity-grievance. RT/Sputnik consumers agreed more than non-users with all identity-grievance propositions, except ‘Countryside residents are easily forgotten’. This might be explained by the fact that countryside residents are underrepresented among RT/Sputnik consumers, although this is speculation.

Second, and contrary to expectations, RT/Sputnik consumers also aligned more with messaging that contrasts with, and can potentially harm, national security. They were less inclined than non-consumers to view Russia as a threat and to support the national relatively critical stance on the Russian Federation. They were more prone to criticism towards the present state of the Armed Forces, and to Sweden’s capacity to collaborate with other countries. The respondents’ relative alignment with RT/Sputnik messaging on serious issues linked to national security is particularly noteworthy given the existence of confirmation bias, a well-known mechanism in previous research, which should make people reluctant to align with unfamiliar information influence.

Third, even though RT/Sputnik users do trust Swedish media outlets more than they trust RT and Sputnik, they nevertheless display lower trust than non-users in Swedish politicians, societal institutions, media outlets, news, and journalism. This confirms previous research demonstrating that consumption of nonmainstream media is negatively associated with trust in the media in general (Schwarzenegger, Citation2021; Tsfati & Peri, Citation2006). At the same time, RT/Sputnik consumers stand out with a very high media consumption, being drawn to all kinds of media outlets, which is in line with findings on RT Twitter audiences (Crilley et al., Citation2022, p. 17).

Despite displaying less trust in the media, RT/Sputnik consumers were slightly more prone than non-users to spread news content of these news media outlets, both on social media and in real life, to family and friends. They also demonstrate a relatively more wreckless sharing behavior, being somewhat more prepared than non-consumers to disseminate unreliable information including RT and Sputnik, both online and in real life. The finding that some consumers spread messaging despite being distrustful of the source corresponds with research showing that consumers in Russia aligned with state-sponsored messaging that built upon widespread historic memories despite displaying distrust in the sources (Szostek, Citation2018). The findings thus represent another indication of the attractiveness of identity grievance narratives.

Although it is beyond the scope of this study to settle on the consequences of the RT/Sputnik consumers’ dissemination of MII in society, it is of value to discuss the matter. Rather than cultivating opposing ideologies (Linvill & Warren, Citation2020, pp. 462–463), the RT/Sputnik narratives on Sweden boost only nationalist and anti-liberal views. This is in line with Golovchenko et al. (Citation2020), who found that Internet Research Agency’s (IRA) primary strategy during the US 2016 elections was to support one side, rather than to saw as much as discord as possible in society. This said, the RT/Sputnik messaging could still work to divide groups and people of different opinions in Swedish society. It can also undermine societal cohesion by decreasing trust in politicians and societal institutions. The analysis demonstrates that although young, men and followers of the Sweden Democrat party, are overrepresented, there are RT/Sputnik consumers of all ages, and among followers of all political parties. This means that even though RT/Sputnik consumers rarely share RT/Sputnik news content, when they do so, this messaging has the potential to reach all segments of society. Furthermore, many non-users also align with the RT/Sputnik narrative and might be prepared to accept such messaging. To illustrate, 27% of all respondents stated that liberalism has gone too far, 55% that politicians have lost control over societal development, and 16% that Sweden exaggerates the threat from Russia. This corresponds with research indicating that far-right discourse – that overlaps with RT/Sputnik messaging – has gradually become seen as less radical and more political mainstream in Sweden (Arceneaux et al., Citation2021, p. 3). This increases the likelihood that the MII is well received also among many non-consumers, when spread on social media and in real life.

There are also some peculiarities within the section of RT/Sputnik consumers. Despite being critical of the practices of the Armed Forces, RT/Sputnik consumers display more trust in the Armed Forces than in other societal institutions. Moreover, paradoxically, despite being comparatively ‘mild’ on Russia, they are relatively supportive of Sweden deepening ties to Russia’s traditional antagonist NATO. These odd results might indicate that RT/Sputnik consumers appreciate any constellation that demonstrates strength, cohesion, and military resolve. Furthermore, it might signify that the RT/Sputnik audience is a segment of media consumers not driven by any comprehensive or consistent political ideology or agenda. If so, they be unconscious, and/or involuntary, agents of Russian MII. This would correspond with Noppari et al. (Citation2019, p. 29) identification of a particular group of consumers of populist counter-media in Finland, that they label ‘agenda critics’. This group appreciates counter-media’s confrontation with national journalism and views mainstream media content as biased against their views, but, in contrast to more extreme ‘system skeptics’, do not take firm ideologically extreme positions or actively engage to a large extent in alternative media sites to promote their views. The findings on Swedish RT/Sputnik consumers also call to mind a category of media users identified by previous research; destructive chaos-seekers that thrive on confrontation, with a particular appetite for harming civil debate online. This category was identified among young male American consumers, consisting of a sub-group consuming a lot of news, seeking, and enjoying confrontation and provocative positions, and being active in spreading hostile political rumors (Petersen et al., Citation2018; Åkerlund, Citation2021Citation2021). Consumers with such a chaos-seeking profile can contribute to a central goal of RT; to broadcast, not a consistent political message, but ‘anything that causes chaos’ (Elswah & Howard, Citation2020, p. 631, 640).

Nonetheless, even though RT/Sputnik consumers expressed slightly less trust in the media, politicians, and public agencies than non-consumers, the results of this investigation do not provide solid evidence that RT/Sputnik consumers are strongly anti-establishment. Furthermore, RT/Sputnik users still trust traditional Swedish media, Swedish journalists in general and Public service more than they trust Swedish alternative media, Sputnik and RT. More research is therefore required to probe similarities to the chaos-seeking young consumers identified in the US context, and to get a better understanding of their overall characteristics.

Conclusion

This study is one of the scarce contributions to research on consequences of malign information influence (MII). The results demonstrate the allure of MII packaged as attractive international broadcasting, by showing a surprisingly high number of Swedish respondents (7%) consuming RT and/or Sputnik. RT/Sputnik users exist within all categories of respondents, yet there is a clear overrepresentation of young, men and partisans of non-parliamentarian parties and the right-wing nationalist Sweden Democratic Party. These consumers are active in disseminating news. Furthermore, the findings exposed that consumers align with RT/Sputnik messaging on identity-grievance issues and national security more than non-consumers do. They hold the potential to function as megaphones of Russian messaging in Sweden, whether intentionally or not.

The RT/Sputnik consumers alignment with MII messaging might be particularly problematic given the overrepresentation of young, media savvy men, with the potential of reaching many in their social media networks. Although RT/Sputnik consumers very rarely report that they share unreliable news, they are nevertheless somewhat more prone than non-consumers to do so. They are also more prone than non-consumers to align with propositions that boost negative feelings and are more willing to spread the news to others, perhaps to their real or imagined ‘communities of discontent’. These assumptions need to be probed in future research, which is much needed to provide an accurate understanding of this group of media consumers. Such research should move beyond the survey methodology, which is limited in providing a set number of propositions and questions, disenabling respondents from freely stating and elaborating on their views in their own words.

Research employing qualitative methods that have been found valuable in research on the reception of media narratives would serve as a particularly fruitful follow-up to the findings of this article. Focus groups are less useful, due to the potential stigma linked to consumption of alternative media that might impede respondents from freely stating their intentions and opinions. Yet, Q-methodology that involves a data collection that beings with the respondent’s viewpoint (Keuleers, Citation2021), audio diaries, and in-depth interviews (Szostek, Citation2018) are suitable for capturing consumers’ viewpoints and wordings. Such research need to unearth consumers’ individual narratives and assess their alignment with the Russian narratives. It could also expose driving forces for consumption and sharing with better accuracy and uncover distinctions between sub-groups within the Sputnik and/or RT audience. Another pertinent issue is whether audiences experience narratives in Sputnik differently from those conveyed in RT, and whether broadcasted narratives elicit stronger or otherwise different reactions compared to textual narratives, for instance due to a stronger effect of the mechanism of transportation, through which the audience get ‘immersed’ into the story (Wojcieszak & Kim, Citation2016).

The potential of MII should not be overestimated, since the tendency to primarily accept information that confirms previous attitudes and worldviews limits the likelihood of attitude change (Lewandowsky et al., Citation2012). Nevertheless, audiences are not immune to being influenced by unfamiliar information and the strength of confirmation bias can vary depending on individual factors and across national contexts (Knobloch-Westerwick et al., Citation2019). Future research needs to study the impact of MII from different messengers and in different national contexts.

This study has nevertheless provided unique quantitative data on the number and character of RT and Sputnik consumers in one national context and exposed their alignment with the narratives and reasons for consuming and sharing that can inspire future research. It has contributed to the under-researched problem of the potential of MII embedded in attractive international broadcasting exploiting effective narratives to take root and spread in a democratic society. The findings indicate that, intentionally or not, consumers of MII can function as suitable vehicles for aiding the messenger in trying to polarize society, undermine democracy and even eroding the national security interests of the target state.

Acknowledgements

For excellent research assistance, I thank Torsten Blad. For very helpful feedback, I thank two anonymous reviewers and Aiden Hoyle.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Charlotte Wagnsson

Charlotte Wagnsson is Professor of Political Science at the Swedish Defence University. Her research interests include European security, political communication in the security sphere and strategic narratives. She has published her works in journals such as New Media and Society, Journal of Common Market Studies, Media, War and Conflict and European Security.

References

- Åkerlund, M. (2021). Dog whistling far-right code words: The case of ‘culture enricher’ on the Swedish web. Information, Communication & Society, 2021, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2021.1889639

- Arceneaux, K., Gravelle, T. B., Osmundsen, M., Petersen, M. B., Reifler, J., & Scotto, T. J. (2021). Some people just want to watch the world burn: The prevalence, psychology and politics of the ‘Need for Chaos’. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. B, 376(1822), 20200147. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2020.0147

- Bennett, L., & Livingston, S. (2018). The disinformation order: Disruptive communication and the decline of democratic institutions. European Journal of Communication, 33(2), 122–139. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323118760317

- Bjola, C., & Papandakis, K. (2019). Digital propaganda, counterpublics and the disruption of the public sphere: The Finnish approach to building digital resilience. Cambridge Review of International Affairs, 33(1), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/09557571.2019.1704221

- Colliver, C., Pomerantsev, P., Appelbaum, A., & Birdwell, J. (2018). Smearing Sweden: International influence campaigns in the 2018 Swedish election. LSE Institute of Global Affairs.

- Crilley, R., & Chatterje-Doody, P. N. (2020). Emotions and war on YouTube: Affective investments in RT’s visual narratives of the conflict in Syria. Cambridge Review of International Affairs.

- Crilley, R., Gillespie, M., Vidgen, B., & Willis, A. (2022). Understanding RT’s audiences: Exposure not endorsement for Twitter followers of Russian state-sponsored media. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 27(1), 220–242. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161220980692

- Cushion, S. (2021). UK alternative left media and their criticism of mainstream news: Analysing the canary and evolve politics. Journalism Practice. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2021.1882875

- Deverell, E., Wagnsson, C., & Olsson, E.-K. (2020). Destruct, direct and suppress: Sputnik narratives on the Nordic countries. The Journal of International Communication, 27(1), 15–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/13216597.2020.1817122

- Eberle, J., & Daniel, J. (2019). Putin, you suck”: affective sticking points in the Czech narrative on “Russian hybrid warfare. Political Psychology, 40(6), 1267–1281. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12609

- Elswah, M., & Howard, P. N. (2020). “Anything that causes chaos”: The organizational behavior of Russia Today (RT). Journal of Communication, 70(5), 623–645. https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqaa027

- Engesser, S., Ernst, N., Esser, F., & Büchel, F. (2017). Populism and social media: How politicians spread a fragmented ideology. Information, Communication & Society, 20(8), 1109–1126. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2016.1207697

- Gérard, C., Guilhem, M., & Loqman, S. (2020). RT, Sputnik et le mouvement des gilets jaunes: Cartographie des communautés politiques sur Twitter RT, Sputnik and the yellow vest movement: Mapping political Communities on Twitter. L’Espace Politique, 40(1). https://doi.org/10.4000/espacepolitique.8092

- Glenski, M., Volkova, S., & Kumar, S. (2020). User engagement with digital deception. In K. Shu, S. Wang, D. Lee, & H. Liu (Eds.), Disinformation, misinformation, and Fake news in social media. Lecture notes in social networks (pp. 39–61). Springer.

- Golovchenko, Y., Buntain, C., Eady, G., Brown, M. A., & Tucker, J. (2020). The International Journal of Press/Politics, 25(3), 357–389.

- Golovchenko, Y., Hartmann, M., & Adler-Nissen, R. (2018). State, media and civil society in the information warfare over Ukraine: Citizen curators of digital disinformation. International Affairs, 94(5), 975–994. https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iiy148

- Groll, E. (2014). Kremlin’s ‘Sputnik’ newswire is the BuzzFeed of propaganda. Foreign Policy, 10 November. Available from: http://foreignpolicy.com/2014/11/10/kremlins-sputnik-newswireisthe-buzzfeed-of-propaganda/ [Accessed 2 March 2021)]

- Guess, A., Nagler, J., & Tucker, J. (2019). Less than You think: Prevalence and predictors of fake news dissemination on Facebook. Science Advances, 5(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aau4586

- Hall Jamieson, K. (2018). Cyber war: How Russian hackers and trolls helped elect a president. Oxford University Press.

- Hameleers, M., Bos, L., & de Vreese, C. H. (2017). “They Did It”: The effects of emotionalized blame attribution in populist communication. Communication Research, 44(6), 870–900. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650216644026

- Heft, A., Mayerhöffer, E., Reinhardt, S., & Knüpfer, C. (2019). Beyond Breitbart: Comparing right-wing digital news infrastructures in six Western democracies. Policy & Internet, 12(1). https://doi.org/10.1002/poi3.219

- Hellman, M. (2021). Infodemin under pandemin: Rysk informationspåverkan mot sverige (The info-demic during the pandemic: Russian information influence activities against Sweden). Statsvetenskaplig Tidskrift, 123(5), 451–474.

- Holt, K., Figenschou, T. U., & Frischlich, L. (2019). Key Dimensions of Alternative News Media. Digital Journalism, 7(7), 860–869. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2019.1625715

- Hoyle, A., van den Berg, H., Doosje, B., & Kitzen, M. (in press). Portrait of a liberal chaos: RT's antagonistic strategic narration about the Netherlands. Media, War and Conflict.

- Humprecht, E. (2019). Where ‘fake news’ flourishes: A comparison across four Western democracies. Information, Communication & Society, 22(13), 1973–1988. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2018.1474241

- Hutchens, M. J., Hmielowski, J. D., & Beam, M. A. (2019). Reinforcing spirals of political discussion and affective polarization. Communication Monographs, 86(3), 357–376. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637751.2019.1575255

- Keating, V. C., & Kaczmarska, K. (2017). Conservative soft power: Liberal soft power bias and the ‘hidden’ attraction of Russia. Journal of International Relations and Development, 22(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41268-017-0100-6

- Keuleers, F. (2021). Choosing the better devil: Reception of EU and Chinese narratives on development by South African University students. In A. Miskimmon, B. O'Loughlin, & J. Zeng (Eds.), One belt, One road, One story?. Palgrave studies in European union politics (pp. 167–194). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Khaldarova, I., & Pantti, M. (2016). Fake news. Journalism Practice, 10(7), 891–901. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2016.1163237

- Knobloch-Westerwick, S., Liu, L., Hino, A., Westerwick, A., & Johnson, B. K. (2019). Context impacts on confirmation bias: Evidence from the 2017 Japanese snap election compared with American and German findings human. Communication Research, 45(4), 427–449. https://doi.org/10.1093/hcr/hqz005

- Lecheler, S., & Egelhofer, J. L. (2021). Consumption of misinformation and disinformation. In H. Tumbar, & S. Waisbord (Eds.), The routledge companion to media disinformation and populism. Taylor & Francis Group.

- Lewandowsky, S., Ecker, U. K. H., Seifert, C. M., Schwartz, N., & Cook, J. (2012). Misinformation and Its correction: Continued influence and successful debiasing. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 13(3), 106–131. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100612451018

- Linvill, D. L., & Warren, P. L. (2020). Troll factories: Manufacturing specialized disinformation on Twitter. Political Communication, 37(4), 447–467. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2020.1718257

- Mayerhöffer, E., & Heft, A. (2021). Between journalistic and movement logic: Disentangling referencing practices of right-wing alternative online news media. Digital Journalism. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2021.197491

- Mejias, U. A., & Vokuev, N. E. (2017). Disinformation and the media: The case of Russia and Ukraine. Media, Culture & Society, 39(7), 1027–1042. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443716686672

- Müller, P., & Schulz, A. (2021). Alternative media for a populist audience? Exploring political and media use predictors of exposure to Breitbart, Sputnik, and Co. Information, Communication & Society, 24(2), 277–293. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2019.1646778

- Nisbet, E., & Kamenchuk, O. (2019). The psychology of state-sponsored disinformation campaigns and implications for public diplomacy. The Hague Journal of Diplomacy, 14(1-2), 65–82. https://doi.org/10.1163/1871191X-11411019

- Noppari, E., Hiltunen, I., & Ahva, L. (2019). User profiles for populist counter-media websites. Journal of Alternative and Community Media, 4(1), 23–37. https://doi.org/10.1386/joacm_00041_1

- Peisakhin, L., & Rozenas, A. (2018). Electoral effects of biased media: Russian television in Ukraine. American Journal of Political Science, 62(3), 535–550. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12355

- Petersen, M. B., Osmundsen, M., & Arceneaux, K. (2018). The “need for Chaos” and motivations to share hostile political rumors. PsyArXiv. September 1.

- Ramsay, G., & Robertshaw, S. (2019). Weaponising news RT, Sputnik and targeted disinformation. King’s College.

- Rawnsley, G. (2016). Introduction to “International broadcasting and public diplomacy in the 21st century”. Media and Communication, 4(2), 42–45. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v4i2.641

- Rawnsley, G. D. (2015). To know us is to love us: Public diplomacy and international broadcasting in contemporary Russia and China. Politics, 35(3-4), 273–286. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9256.12104

- Schwarzenegger, C. (2021). Communities of darkness? Users and uses of anti-system alternative media between audience and community. Media and Communication, 9(1), 99–109. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v9i1.3418

- Szostek, J. (2018). Nothing is true? The credibility of news and the conflict in Ukraine. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 23(1), 116–135. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161217743258

- Thorbjørnsrud, K., & Figenschou, T. U. (2020). The alarmed citizen: Fear, mistrust, and alternative media. Journalism Practice, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2020.1825113

- Tsfati, Y., & Peri, Y. (2006). Mainstream media skepticism and exposure to extra-national and sectorial news media: The case of Israel. Mass Communication & Society, 9(2), 165–187. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327825mcs0902_3

- Tucker, J., Guess, A., Barberá, P. M., Vaccari, C., Siegel, A., Sanovich, S., Stukal, D., & Nyhan, B. (2018). Social media, political polarization, and political disinformation: A review of the scientific literature. William + Flora Hewlett Foundation.

- Turcsanyi, R., & Kachlikova, E. (2020). The BRI and China’s Soft Power in Europe: Why Chinese Narratives (Initially) Won. Journal of Current Chinese Affairs, 49(1), 58–81. https://doi.org/10.1177/1868102620963134

- Wagnsson, C. (2020). What is at stake in the information sphere? Anxieties about malign information influence among ordinary Swedes. European Security, 29(4), 397–415. https://doi.org/10.1080/09662839.2020.1771695

- Wagnsson, C., & Barzanje, C. (2021). A framework for analysing antagonistic narrative strategies: A Russian tale of Swedish decline. Media, War & Conflict, 14(2), 239–257. https://doi.org/10.1177/1750635219884343

- Watanabe, K. (2018). Conspiracist propaganda: how Russia promotes anti-establishment sentiment online. Paper presented at ECPR General Conference 2018, Hamburg, Available from: file:///C:/ Users/s-9426/Downloads/Sputnik05ECPR.pdf [Accessed 8 May 2020].

- Wojcieszak, M., & Kim, N. (2016). How to improve attitudes towards disliked groups: The effects of narrative versus numerical evidence on political persuasion. Communication Research, 43(6), 785–809. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650215618480

- Wojcieszak, M., & Warner, B. R. (2020). Can interparty contact reduce affective polarization? A systematic test of different forms of intergroup contact. Political Communication, 37(6), 789–811. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2020.1760406

- Wright, K., Scott, M., & Bunce, M. (2020). Soft power, hard news: How journalists at state-funded transnational media legitimize their work. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 25(4), 607–631. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161220922832

- Zimmermann, F., & Kohring, M. (2020). Mistrust, disinforming news, and vote choice: A panel survey on the origins and consequences of believing disinformation in the 2017 German Parliamentary Election. Political Communication, 37(2), 215–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2019.1686095

Appendix

Table A1. Age and gender: statistically significant differences users/non-users.

Table A2. Political party: statistically significant differences users/non-users.