ABSTRACT

In this paper, we explore how highly visible users in the context of #BlackLivesMatter on TikTok shape the narrative around Black victims of police brutality, the understanding of these narratives by others, and the potential consequences of these portrayals for the movement at large. To examine these dimensions, we analysed the 100 most circulated TikTok videos and associated comments depicting victims of police brutality using the #BlackLivesMatter hashtag through multimodal critical discourse analysis. We identified how users attempted to increase visibility of their content, and how this was supported or criticised by commenters depending on the perceived motives of these efforts. Furthermore, we showcased how influencers raised awareness of the movement with little personal effort or risk, sometimes appearing to leverage the movement for self-exposure. Our analysis showed that many of the most liked videos were made by white content creators who, in their videos, seemed to be addressing an imagined white audience. While these efforts portrayed the movement favourably, the content creators remain outsiders who have not themselves been in harm's way of police brutality. While there were exceptions that promoted the perspectives of marginalised communities, and while the white narratives were consistently supportive of the movement, they also work to displace focus on racial (in)justice away from those directly affected by it, that is, away from Black people’s own experiences of police brutality. We discuss these findings in relation to questions about digital representations of Black victimhood, digital visibility and practices of whiteness, on TikTok and beyond.

Introduction

Social media platforms can provide spaces for ‘historically disenfranchised populations to advance counternarratives and advocate for social change’ (Jackson et al., Citation2020, p. 38). Specifically, with the help of smartphones and social media, individuals can record and share instances of police brutality towards Black people. These overt displays of institutional racism have been shared online through the use of hashtags like #BlackLivesMatter, allowing users to challenge the dominance of a ‘white gaze’ on black bodies (Yancy, Citation2017) by calling attention to Black victims of police brutality as a public issue (Clark et al., Citation2017), educating, supporting, and spreading victims’ stories nationally (Freelon et al., Citation2016) and framing these within a larger collective of Black victims (and potential victims) of police brutality (Langa & Creswell, Citation2019). These narratives, as mediated through visual social media narratives, can be particularly likely to reach the news media’s attention (Richardson, Citation2017), and, thus, by extension topotentially challenge hegemonic perspectives on Black victims of police brutality. In light of this, in this paper, we are interested in the use of the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter on the video-based social media platform TikTok – one of the most downloaded apps worldwide in 2020, according to Forbes (Bellan, Citation2020, february 14) – to understand how Black victims of police brutality are framed and circulated, and by whom.

TikTok functions on an interest graph, which means that content uploaded to the platform is ordered algorithmically in accordance with how the user engages on the platform and does not rely on the follower/followee-logic of many other conventional social media platforms. Correspondingly, TikTok’s algorithmic recommendation system has gained notoriety for its ability to make content ‘go viral’, evoking questions about the communicative powers of TikTok videos. By extension, the platform may have potential for the promotion of Black activists and social movements such as #BlackLivesMatter.

However, the mere existence of police brutality towards black people, and the frequent use of hashtags like #BlackLivesMatter, do not, by default, serve to strengthen the rights of Black people. It is important to note that the definition of police brutality is up to the interpreter, what Meredith Clark deems the ‘social construction of police brutality’ (Clark et al., Citation2017, p. 292) and relatedly, there is an on-going struggle in social movements like Black Lives Matter in terms of who has the power to be heard and seen (Vis et al., Citation2019). Moreover, users frame their content differently depending on their ‘imagined audience’, i.e., the people envisioned as the recipient of a message or pictured as the ‘public’ when performing in digital spaces (Litt, Citation2012). Such an imagined audience may, in turn, have consequences for how TikTok users present political issues, and more specifically, how different content creators use #BlackLivesMatter to shape the conversation on, and understanding of, racial inequality on TikTok.

Therefore, we aim to explore how highly visible users in the context of #BlackLivesMatter on TikTok are shaping the narrative around Black victims of police brutality, the understanding of these narratives by others, and the potential consequences of these portrayals for the movement at large. To do this, we investigate visual features of Black victimisation, users’ modes of gaining visibility and their approach to imagined audiences, and lastly, the perception of these issues by their audiences. In doing so, we seek to fill a gap more generally in regard to TikTok as a novel and immensely popular, yet under-explored social setting. Recent research has shown the potential of this platform for climate activism, and the important role of non-expert content creators in these contexts (Hautea et al., Citation2021). More specifically, in the context of social movement literature on Black Lives Matter, we address the lack of analysis of visual imagery (Walker, Citation2021), while also answering the call to look beyond the oft-explored Twitter in the study of the Black Lives Matter movement (Freelon et al., Citation2016).

Black victimhood and whiteness

The way victims are publicly recognised depends on how such victims are framed and understood in society more broadly. Discourses about the potential ‘ideal victim’ (Christie, Citation1986) are based on societal status and interpretations, which in the Western world are deeply intertwined with ideals of whiteness, and are thus rarely granted to individuals from marginalised groups in society, such as those belonging to Black communities (Long, Citation2021). The distinctions between who are viewed as ‘good’ or ‘bad’ victims in society ultimately shape the extent to which these victims receive support and compassion, or simply oblivion and contempt (Gracia, Citation2018). Victims of crime, and the people who speak on their behalf, use a ‘vocabulary of victimisation’ (Dunn, Citation2010) by describing their motives, actions, experiences, and reactions for a victim to pass as ‘legitimate’ in a discursive sense. These vocabularies can be vocalised in different ways and in different societal settings. For Dunn, it is essential to study how such vocabularies are formulated and how they are altered, abandoned, or broadened when such narratives are not sufficient for acquiring a legitimate status as a victim (Dunn, Citation2010, p. 177).

Black victims through a white lens

The dominant ‘white gaze’ (Yancy, Citation2017) in Western society, through which systemic racism and whiteness objectify and render black bodies dangerous, hypersexualised, and unwanted, means that Black people are generally not seen as legitimate victims. This is even though only 13% of US Americans are Black, they are 2.5 times more likely to be shot to death by police than white US Americans (Lowery, Citation2016), especially if they are unarmed (Jones, Citation2017). While being victimised exponentially more often than other people, Black men are especially vulnerable in ‘not fitting the profile’ for ideal victimhood. And while victim statuses are not desirable for all victims due to the perceived weaknesses of this role (Jägervi, Citation2014), more compassionate and inclusive victim policies would entail larger societal compassion for victims and their rights.

Legacy news media, which play an important role in the portrayal and legitimisation of victims on a societal level, have largely worked to cement these views of Black victims through the predominance of white perspectives in their news production practices and a primary focus on reporting news that are interesting to white audiences (van Dijk, Citation1991). Consequently, when Black people are portrayed in the news, it tends to be in relation to crime stories (Bjornstrom et al., Citation2010). However, often these depictions are not of Black victims. Previous research shows that Black murder victims tend to receive less news coverage than white victims (Bjornstrom et al., Citation2010; Weiss & Chermak, Citation1998). When Black victims are covered in news reports, they are more likely than white people to be portrayed as responsible for their victimisation. Young, Black, male, homicide victims, for instance, are often portrayed as criminal ‘thugs’ (Wright & Washington, Citation2018), while Black female victims are often depicted as residing in unsafe environments and taking excessive risks (Slakoff & Brennan, Citation2019).

Media reporting of the Black Lives Matter movement have been shown to portray the struggles of Black victims unfavourably by relying on elite sources rather than protestors own accounts (Everbach et al., Citation2018), and by focusing excessively on negative reporting, which demonises the movement (Umamaheswar, Citation2020), while also delegitimizing social media user’s efforts as mere misinformation (Leopold & Bell, Citation2017). These negative media depictions contribute to reinforcing racist and cultural stereotypes (Gruenewald et al., Citation2013; Wright & Washington, Citation2018), depicting the victimisation of Black people as ‘ordinary’ or unavoidable (Slakoff & Brennan, Citation2019; Weiss & Chermak, Citation1998), and reinforces misconceptions about Black people’s own supposed responsibility for being victimised (Dukes & Gaither, Citation2017; Smiley & Fakunle, Citation2016).

These white gazed media portrayals of Black victims are but a symptom of centuries of racism, oppression and positioning Black people as inherently violent and criminal (Chaney & Robertson, Citation2015; Jones, Citation2017; Smiley & Fakunle, Citation2016). This, along with a continuous opposition by many white people towards contemporary social justice movements attempting to address these issues (Nummi et al., Citation2019) helps cement systemic racism and ideals of whiteness in depictions of Black victims. But whereas legacy news media have often lacked racial sensitivity in their reporting on the struggles of Black communities, social media has come to provide an essential medium of resistance and contention of the white gaze in legacy news media reporting.

Social media resistance and #BlackLivesMatter

While the internet certainly never became the race-free utopia, it was once theorised as (Nakamura, Citation2002), and social media settings in particular, have been identified as facilitating racism and hegemonic whiteness (Cisneros & Nakayama, Citation2015; Matamoros-Fernández, Citation2017; Merrill & Åkerlund, Citation2018), social media have simultaneously been shown to enable the resistance against such detrimental forces. Where Black people (unsurprisingly) often experience a mistrust in news media’s representations of Black communities and victims (Freelon et al., Citation2018; Nummi et al., Citation2019), social media offers spaces for the propagation of ‘counterstories’ to oppose these misrepresentations (Clark et al., Citation2017), as well as efficient ways for organising and spreading information and ideas (Gerbaudo, Citation2012).

Mainly, by opposing news media portrayals through the use of the camera and video functions on their mobile phones, Black communities are ‘shifting the power of gatekeeping’ (see also Everbach et al., Citation2018; Walker, Citation2021, p. 13) to bypass traditional news channels’ mediation (Clark et al., Citation2017). Potentially at least in part due to these opportunities, Black people have become particularly prolific social media users (Nummi et al., Citation2019; Walker, Citation2021). Black people are avid users of social media but use them in more activist manners than white people, according to data from Pew Research Center (Auxier, Citation2020).

Notably, ‘Black Twitter’ constitutes a particularly active and engaged activist space in a social media setting (Clark, Citation2014) ‘in which black people discuss issues of concern to themselves and their communities—issues they say either are not covered by mainstream media, or are not covered with the appropriate cultural context’ (Freelon et al., Citation2018, p. 38), which has helped Black Twitter users connect and strategically raise issues of racial inequality (Brock, Citation2012).

However, for a social movement to successfully address issues of racial inequality and (in)justice, there is a need for ‘white allyship’– that there is support from privileged white community members, who through racially aware, active efforts, work to propel the cause of the movement (Clark, Citation2019; Jackson et al., Citation2020). In these efforts, the vocabularies of victimisation (Dunn, Citation2010) of these white allies may strengthen the case for legitimising the experiences of Black victims. The Black Lives Matter movement on Twitter has successfully reached and engaged white allies, who have been seen to promote the contents, accounts, and leaderships of Black activists (Clark, Citation2019). Research has shown that Black voices have continuously constituted the most highly referenced users in #BlackLivesMatter on Twitter (Freelon et al., Citation2016).

While less is known about the progress of the Black Lives Matter movement on TikTok, the platform could potentially fill a similar function for the Black community like Twitter. For instance, according to Pew Research Center (Citation2021), TikTok, like Twitter, is disproportionately used by Black communities. Relatedly, in discussing the context through which Black people use TikTok, André Brock (Citation2021, p. 47:10) noted that the platform ‘provides an intimate, mediated space in which Black folks can talk about the things that are valuable to them (…) in ways that activate and reassert your humanity.’ In these ways, apps like TikTok could work to connect Black communities and reinvigorate their status in ways that promote a sense of belonging and collectivity while challenging white, hegemonic representations of Black victimhood.

Research design

On 10 August 2020, we saved and screen recorded the top 100 algorithmically ranked TikTok videos using the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter based on their number of views.Footnote1 illustrates the user interface of TikTok when searching for this hashtag, in this specific moment. Since we were interested specifically in the ways victims of police brutality were mentioned, we focused the analysis on the 39 of these 100 videos addressing victims of police brutality specifically by talking about victims, showing images or video footage of victims, showing protesters being victimised by the police, simply using victim-related hashtags (for example, #georgefloyd or #breonnataylor). In addition to this, we were interested in the conversations taking place in the comment section, where a subsample of the five most-liked comments for each of the 39 victim-related videos was analysed. With some videos having their comments sections turned off, this subsample contained 139 comments.

Figure 1. Screenshot of the TikTok interface when searching videos with the #BlackLivesMatter hashtag, picture taken by the researchers in July 2020.

Figure 2. Screenshot of video by @charlidamelio, addressing the camera. Video uploaded on 30 May 2020.

In this study, a lexical and visual analysis of these choices are incorporated to understand how the TikTok videos relate to discourse regarding victimhood, race, and social (in)justice. Therefore, we used a combination of Multimodal Discourse (MD) and Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA), referred to as Multimodal Critical Discourse Analysis (MCDA) by Machin and Mayr (Citation2012) when analysing the videos. The method takes on a ‘social semiotic view of language’, which emphasises the way ‘we should see all communication, whether through language, images, or sounds, as accomplished through a set of semiotic resources, options and choices’ (Machin & Mayr, Citation2012, p. 15). This method approaches the lexical and visual semiotic choices in the material in relation to its discursive practices. In this way, discourse is understood as a social practice, which involves written and spoken languages (Fairclough & Wodak, Citation1997, p. 35). According to van Dijk (Citation2001), critical discourse analysis should consider the implicit and indirect meanings in the texts. In this sense, what is not being said is more important than what is being said, referred to as suppression or ‘lexical absence’ (Machin & Mayr, Citation2012, p. 38).

The social production of discourse is dependent specifically on the audience, as it is assumed by images and texts, and because of this, notions about the audience can affect the type of images used (Rose, Citation2016, p. 214). In this study, we are especially interested in understanding which imagined audiences that the TikTok users assume in the creation of their videos, and how their visual semiotic choices are dependent on such a framework. As such, we are not interested specifically in which audiences who are viewing the content per se, but instead, which audiences are being addressed by the TikTok users themselves.

The TikTok videos were analysed first by watching (and re-watching) the 100 videos. Both researchers took the time to do this part of the analysis together, to avoid individual biases to inform the results. This part of the analysis provided a space for us to familiarise ourselves with the data, while simultaneously noting the most basic visual features of each video in a spreadsheet. Additionally, any quantifiable measures were noted in the spreadsheet (i.e., number of likes/comments/shares), and the hashtags used in each video description, to understand their impact on the platform. In other words, while some videos were shared extensively, we were interested in which visual semiotic choices were made in these kinds of videos.

In analyses of the comment sections, we were interested in the lexical choices and stances of the commentators, to understand how these TikTok videos contributed to a discursive practice. Due to the ranking system of comments on the app, where the most-liked comments are made most visible in the comments section, these were the five first comments in each video’s comment section. These comments were analysed based on their general topic (for example, supportive, critical, or educational).

Ethical considerations

Of the 100 sampled videos using the #BlackLivesMatter hashtag, 22 were uploaded by verified accounts, which had the verification tick next to their screen names. These accounts, whose aim is to reach a broad audience, are named and quoted verbatim as they are understood as ‘public figure accounts’ (Williams et al., Citation2017). However, we also acknowledge the importance of noting that although information is publicly available, individuals are often unaware and uncomfortable with the information they perceive as personal and contextual is used outside the social media context for which it was intended (Zimmer, Citation2018). Because of this, we have allowed TikTok users with smaller followings (<1M followers) to opt in to de-anonymised participation (being quoted and named by their usernames), as well as the opportunity for larger accounts, 1–10M followers, to opt-out of being quoted. These TikTokers were contacted through their TikTok accounts or other contact information (such as Instagram accounts or e-mail addresses). They received a time window of two weeks and several reminders to reply. Moreover, we have not included the actual comments to specific TikTok videos in their original form for privacy reasons. Instead, these have been anonymised by rearranging and replacing identifiable words (Markham, Citation2012).

In researching issues of race and racism, we are inclined to reflect on our positionality as researchers and how these matter for this study’s outcome. As the race, nationality, age, gender, sexuality, and socio-economic status matter for the ‘positions’ in terms of power as researchers (Rose, Citation1997), we can in no way understand the experiences of Black US Americans, being two white, female, and European researchers ourselves. Thus, we have carried out this study by considering our positions in relation to this research. Part of this process has meant that we have attempted to ‘readjust [our] white gazes’ (cf. Yancy, Citation2017, p. 9). While structural racism becomes internalised in a myriad of ways, by taking our own positions into account, we have acknowledged the risk of reproducing a predominantly ‘white narrative’ and attempted to hinder reproducing these narratives.

Black victimhood, visibility, and whiteness

Video overviews

A total of 39 of the 100 sampled videos addressed victims of police brutality either by talking about, showing images or video footage of victims directly (n = 26), showing individuals being victimised by the police (n = 2), or simply using victim-related hashtags (for example, #georgefloyd or #breonnataylor) (n = 11). Some videos directly depicted how police officers victimised black individuals, for instance, by showing protesters being shot by rubber bullets or being teargassed by the police. In one instance, a Black TikTok user filmed himself getting victimised by police in his car after being pulled over.

Over half of the sampled comments contained positive feedback, either written in support of the TikTok user posting the video (27.2%) or in solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement itself (24.1%). While two comments in our study did resort to victim-blaming by explicitly referring to George Floyd’s criminal history, this framing was otherwise rare in the comments. While TikTok has been described as harbouring massive amounts of hate in a far-right context on the platform (Weimann & Masri, Citation2020), our findings suggest that the most well-liked comments to the #BlackLivesMatter content most often contained encouragement from others. Often, commenters were supportive, showed solidarity, and seemed moved and enlightened by the victim-related content. Potentially, TikTok videos sampled in this study might function to form a sense of collectivity and generate relatability for commenters around the issues of race-based discrimination and police brutality (Sobande, Citation2020).

Influence(rs) and visibility

Gaining visibility is important for users on any social media platform and especially on TikTok. New videos appear on users’ feeds – their ‘for you’ pages, and content producers will often use the hashtag #foryou (or #foryoupage, #foryourpage, or #fyp) in active attempts to get featured in other users’ feeds. The hashtag #xyzbca is another hashtag that presumably ‘means nothing’ but is widely used by content creators as part of an ‘algorithmic imaginary’ (Bucher, Citation2017) to boost visibility. Moreover, such efforts are part of a broader ‘visibility labour’ (Abidin, Citation2021), where content creators use specific trending hashtags, filters, keywords, or audio memes to gain visibility on the platform.

This visibility matters, especially amidst a social movement aimed at liberating Black voices. From the most frequently used hashtags in the description of the studied TikTok videos, we can see a pattern of users attempting to go viral with their content (see ). The possibilities of ‘going viral’ on TikTok have received media attention ever since the platform was first launched. Furthermore, while TikTok users are well aware that the algorithm is skewed in many ways, it remains unclear how.

Table 1. Most frequently used hashtags in the TikTok video descriptions.

With their large following, TikTok influencers naturally are more visible and interactional than ‘regular’ TikTok users. Out of the 100 most-watched videos using the #BlackLivesMatter hashtag, 22 were created by ‘verified’ account, meaning that they had risen to some form of notoriety on the platform at the time of data collection. During the height of the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020, famous TikTokers used the #BlackLivesMatter hashtag for expressing what seemed to be rehearsed statements of support for the movement. For example, one of the most famous TikTok users, @charlidamelio (80M followers), well known for her dance videos, was the originator of the most liked video using the #BlackLivesMatter hashtag at the time of data collection ().

Her video was filmed in a home setting, facing the camera directly, with her gaze centred on the audience watching her through the app. While she was wearing makeup, she was not particularly donned up in fancy attire. Her hair was made in a simple ponytail, and she wore a sweatshirt, tied at the top. The camera was solely focused on her, with a white background, and this simplicity in the background, was also reflected through the lack of use of hashtags and video description: simply #BlackLivesMatter. These elements seemed to suggest an urgency of the message and a lack of visibility labour which usually goes into the job practice of influencers, by putting up somewhat of a show. In this video, where she addressed her viewers directly, she stated,

As a person who has been given a platform to be an influencer, I realize that with that title, I have a job to inform people on the racial inequalities in the world right now.

A man was killed. His life was ended. “Don't kill me”, George Floyd says, that's his last words. His life should not be over and his name needs to be heard. George Floyd. A father and a person. A human who lost their life because of the color of their skin. We people of all colors need to speak up at a time like this.

Influencers like @charlidamelio showcase solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement. Yet, these videos are not recorded in a setting that would suggest these influencers are themselves out there, actually ‘doing something’. As seen elsewhere, self-representation practices can be carefully staged by influencers to appeal to their intended audiences (Lewis, Citation2020). Ultimately, influencers seem to be leveraging Black people’s struggles for increased self-exposure but with little effort to support the actual movement (see also Sobande, Citation2021).

Many of the supportive comments directed at specific users were written by fans of influencers, such as @charlidamelio or artists like @lizzo (10.2M followers). Supportive comments directed towards less famous users instead attempted to draw attention to the videos themselves, for example, by insisting that other users helped spread them. When TikTokers were instead critiqued (5.6%), this tended to be when they had supposedly stepped out of line concerning the Black Lives Matter agenda – using the movement to further their causes or status position. For instance, a commenter pointed out an unrelated use of Black Lives Matter hashtags in a white, young man’s humorous video, asking: ‘But why did you use those hashtags? What does this have to do with #georgefloyd and #BlackLivesMatter?’. In another instance, influencer @madisonbeer (11.9M followers) was called out for having hired photographers to accompany her while protesting, seemingly using the movement for her gain. This was noted by commenters who pointed out, ‘This protest is not your [@madisonbeer’s] aesthetic!’. In contrast to the fact that many of the hashtags incorporated into the TikTok videos were explicitly aimed to increase TikTokers’ visibilities, as previously mentioned, the top commenters seem to be instead aimed at reinforcing visibility, reach and cause of the actual movement.

An imagined white audience (874)

Whereas on Twitter, the most acknowledged voices were those of Black users (Freelon et al., Citation2016), on TikTok, this was not always the case. Several of the most liked videos were made by white content creators. And these white content creators seemed to predominantly address an imagined white audience, pleading with them to inform themselves on the issue of racial inequality. One such video featured a mother of a 13-year-old boy – shown fleetingly in the background – addressing the camera directly, while moving around her house with her phone in her hand. In the video, she becomes increasingly agitated as she is speaking, seemingly to the individuals who claim that hardships facing white mothers are equal to those of Black mothers, saying,

Now you are not going to tell me that I have to worry about my son as much as Black mothers have to worry about their sons. You are not gonna tell me that racism does not exist in this country, you are not gonna tell me that there is equality. (…) What happened to George Floyd was murder. It was murder! Period.

The lexical absence of directly addressing her white privilege, which was important for the conversations during the Black Lives Matter protests in 2020, is nonetheless indicated in her storytelling. In addition to this, her narrative is based on her own experiences as a mother, and in this sense, it seems to be addressing specifically the role of mothers in connecting with and partaking in this movement. In addition to this, she said,

And now his mother, who he cried out to, doesn’t get to be with her son. Black Lives Matter. Quit being racist. Quit your shit. Because no mother deserves to go through what that woman just went through. No mother. No matter their color.

These videos are adhering to the notion of collective political action and raising awareness for the Black Lives Matter movement and racial inequality in the US, thus, in a sense performing what could be deemed as ‘white folks work’ (Clark, Citation2019) for the movement’s benefit. Still, the content creators addressed Black victimisation as it is perceived to them as outsiders who have not themselves been in harm’s way for police brutality, and with this, they rely entirely on others’ experiences of violence (Clark, Citation2019; Jackson et al., Citation2020). As these videos were the most viewed videos using the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter at this crucial point in time for the Black Lives Matter movement in 2020, the fact that these specific videos have gained this degree of visibility should be problematised in and of itself. Besides algorithmic visibility, these videos have become amplified also through users’ interactive patterns on the platform based on their perception of some as more credible, interesting, and trustworthy voices on the issues addressed by the movement (see also Freelon et al., Citation2016).

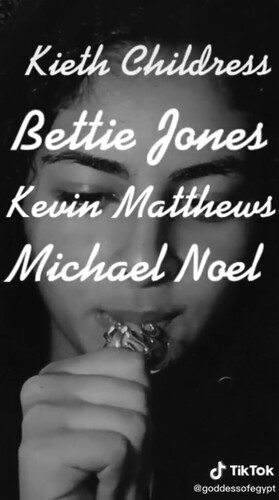

Despite the overall predominance of a white lens, it should be noted that there were also some examples of Black and other People of Color (POC) TikTokers among the most liked videos. However, these users, too, seemed to be creating videos of a deliberately educational nature with a less explicit intended audience. In one such effort, an Egyptian-American woman with the username @goddessofegypt (916.2 K followers) was reciting the names of police brutality victims while holding up and kissing her necklace with the Arabic symbol for Allah, in what could be interpreted as a spoken word poem. The visual semiotic choices made in this video added to the sense of urgency and solemnity through the addition of a black and white filter, which is otherwise seldomly used on the platform. The colour saturation of this video suggested a heightened emotional intensity, which was also translated through the creator’s performance in the video composition (see ).

Figure 3. Screenshot of @goddessofegypt (who has since changed her handle to @hana.hassan on TikTok), reciting her spoken word poem. Video uploaded on 28 May 2020.

Starting with the line ‘Black lives matter, but not until they’re dead, right?’, she recited the name and events surrounding the death of six individual victims of police brutality. Each story was told in the same form, as a mantra, ending with the line, ‘no officers have been charged for this crime’, further highlighting the systematic injustice brought upon Black victims of police brutality. By centring the video on how each of the specific victims has been subjected to the use of lethal force by police officers, and the use of repetition in her oration of their stories, can in itself be what Richardson (Citation2020) has called a militant form of investigative editorial practice. In this sense, the composition of the piece, the oral narration of the victim stories, and the use of specific filters for dramatic effect show the way visualities of black victims are not solely centred on images of the victims themselves but on individual creators and their creative expressions.

Commenters generally supported this type of educational content. Some users showed support for the Black and other POC creators on the platform, for example, by acknowledging the need for white people like themselves to take action, saying, ‘I’m white but I feel your pain. We are all equal. IT’S UP TO US TO CHANGE THE SYSTEM ![]() .’ Potentially, as previously identified on Twitter (see Clark, Citation2019) the exposure to #BlackLivesMatter-related content on TikTok might have exposed white users to movement imagery and ideas which they would not otherwise have encountered. Nonetheless, while this educational social media content regarding the movement might be greatly appreciated by white allies, it can also place a burden on black people to educate white people (Freelon et al., Citation2016).

.’ Potentially, as previously identified on Twitter (see Clark, Citation2019) the exposure to #BlackLivesMatter-related content on TikTok might have exposed white users to movement imagery and ideas which they would not otherwise have encountered. Nonetheless, while this educational social media content regarding the movement might be greatly appreciated by white allies, it can also place a burden on black people to educate white people (Freelon et al., Citation2016).

Discussion

In this paper, we have analysed how highly visible users in the context of Black Lives Matter on TikTok shape the narrative around Black victims of police brutality, the understanding of these narratives by others, and the potential consequences of these portrayals the movement at large. We identified how users attempted to increase the visibility of their Black Lives Matter-related content and how this was supported or criticised by commenters depending on the perceived motives of these efforts. We showcased how influencers raised awareness of the movement almost as if obliged but with little personal effort or risk. Sometimes, it even appeared as if influencers leveraged the movement for personal gain. Furthermore, while exceptions promoted the perspectives of marginalised communities that were moreover highly valued by commenters, our analysis showed that many of the most liked videos were made by white content creators, who, in their videos, seemed to be addressing an imagined white audience.

Even though white TikTokers’ videos consistently supported the BLM movement, these content creators nevertheless remain outsiders, who have not themselves been in harm’s way for police brutality. Furthermore, these white narratives could also work to displace the focus on racial (in)justice from Black people’s own experiences of police brutality and on white people’s interpretations of Black people’s pain and vulnerability. These findings evoke questions about digital representations of Black victimhood and the roles of visibility and whiteness in these contexts.

What is considered police brutality or not is socially constructed since the interpretation of this form of violence differs within the general public and the legal system, as opposed to what can be considered appropriate police conduct (Clark et al., Citation2017). How victims are portrayed in the media has social consequences, and as such, representations matter on a larger societal and political scale. Here, social media can work to counter the dominant white gaze on Black victims of police brutality and serve to empower Black voices and movements (Freelon et al., Citation2018; Nummi et al., Citation2019).

However, while the findings of this paper showed vocabularies of victimisation (Dunn, Citation2010) that focused mainly on informing others about the movement, the injustices it sought to address, and attempts at making victims of police brutality more relatable – for instance, by accounting the causes of Black individuals’ death at the hands of police – the platform and its users failed in doing so primarily through marginalised voices. While social movements addressing issues of racial justice need the engagement of marginalised as well as white communities (Clark, Citation2019), problems arise when movement issues become entirely defined through a white lens and is directed only towards white audiences. Had white allies instead supported and promoted Black activist voices and leadership, the white lens that has often dominated conversations on racial (in)justice could have been countered (Cammarota, Citation2011; Clark, Citation2019).

Since digital media algorithms are inherently racially biased (Noble, Citation2018), it may seem unsurprising that white voices gained greater visibility on the platform. However, the potential political outcome of this increased visibility of white narratives - even if supportive - needs to be addressed, since they could potentially skew the conversation on racial (in)justice away from those directly affected by it, and away from Black people’s own experiences of police brutality. Here, our findings differ from those that have explored the Black Lives Matter movement on Twitter, where Black users’ voices were indeed the most amplified (Freelon et al., Citation2016). Abidin (Citation2021, p. 84) notes that TikTok has allowed young people a space for ‘becoming politically engaged in a format that is entertaining, educational, and palatable among their peers.’ The potential of TikTok as a platform for allowing users to address, share, and become politically aware is, as such, considerable. However, when political action against racial injustice is being addressed and amplified by ‘outsiders’ in regard to actual exposure to police violence, some of this potential is lost. This problem, however, should not be placed entirely on content creators, commenters or ‘likers’. Instead, it should also be thought of in the light of the previous allegations directed toward TikTok in relation to Black creators and the Black Lives Matter Movement. Under the hashtag #BlackTikTokStrike in the summer of 2021, Black creators went on strike to protest the apparent racial biases in the platform’s algorithmic recommendations system. In addition to this, phrases such as ‘Black Lives Matter’ were flagged as ‘inappropriate content’ on their creator marketplace (Colombo, Citation2021), further showing how the platform itself may recreate racial biases.

Not only do these events highlight the need to question algorithmic biases about racial issues, and especially in relation to the Black Lives Matter movement itself, but also more research is needed concerning how the imagined audiences of political movements may shape its digital traces, especially in relation to using personal experiences of victims as a catalysator for political awareness.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank dr. Brooke Foucault Welles for her insightful comments on our initial first draft of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Moa Eriksson Krutrök

Moa Eriksson Krutrök holds a PhD in Sociology from Umeå University, Sweden. Her research interests centre on discourses on trauma and victimisation as communicated through high-profile (social) media events. She is an Associate Professor in Media and Communication Studies at Umeå University [email: [email protected]].

Mathilda Åkerlund

Mathilda Åkerlund holds a PhD in Sociology and is currently working with the Centre for Digital Social Research (DIGSUM) at Umeå University, studying the far-right in Swedish online settings [email: [email protected]].

Notes

1 We created a new TikTok account specifically for the data collection to not skew the algorithm by allowing it to learn our personal preferences.

References

- Abidin, C. (2021). Mapping internet celebrity on TikTok: Exploring attention economies and visibility labour. Cultural Science Journal, 12(1), 77–103. https://doi.org/10.5334/csci.140

- Auxier, B. (2020, July 13). Activism on social media varies by race and ethnicity, age, political party. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/07/13/activism-on-social-media-varies-by-race-and-ethnicity-age-political-party/

- Bellan, R. (2020, February 14). TikTok is the most downloaded app worldwide, and India is leading the charge. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/rebeccabellan/2020/02/14/tiktok-is-the-most-downloaded-app-worldwide-and-india-is-leading-the-charge/.

- Bjornstrom, E. E. S., Kaufman, R. L., Peterson, R. D., & Slater, M. D. (2010). Race and ethnic representations of lawbreakers and victims in crime news: A national study of television coverage. Social Problems, 57(2), 269–293. https://doi.org/10.1525/sp.2010.57.2.269

- Brock, A. (2012). From the blackhand side: Twitter as a cultural conversation. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 56(4), 529–549. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2012.732147

- Brock, A. (2021). Race and racism in internet studies. AOIR 2021 keynote address.

- Bucher, T. (2017). The algorithmic imaginary: Exploring the ordinary affects of Facebook algorithms. Information, Communication and Society, 20(1), 30–44. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/1369118X.2016.1154086?journalCode=rics20.

- Cammarota, J. (2011). Blindsided by the Avatar: White saviors and allies out of hollywood and in education. Review of Education, Pedagogy, and Cultural Studies, 33(3), 242–259. https://doi.org/10.1080/10714413.2011.585287

- Chaney, C., & Robertson, R. W. (2015). Armed and dangerous? An examination of fatal shootings of unarmed black people by police. The Journal of Pan African Studies, 8(4), 45–78. http://www.jpanafrican.org/docs/vol8no4/8.4-5-CCRR.pdf

- Christie, N. (1986). The ideal victim. In E. A. Fattah (Ed.), From crime policy to victim policy: Reorienting the justice system (pp. 17–30). The Macmillan Press.

- Cisneros, J. D., & Nakayama, T. K. (2015). New media, old racisms: Twitter, miss America, and cultural logics of race. Journal of International and Intercultural Communication, 8(2), 108–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/17513057.2015.1025328

- Clark, M. D. (2014). To tweet our own: A mixed-method study of the online phenomenon ‘Black Twitter’. University of North Carolina.

- Clark, M. D. (2019). White folks’ work: Digital allyship praxis in the #BlackLivesMatter movement. Social Movement Studies, 18(5), 519–534. https://doi.org/10.1080/14742837.2019.1603104

- Clark, M. D., Bland, D., & Livingston, J. A. (2017). Lessons from #McKinney: Social media and the interactive construction of police brutality. The Journal of Social Media in Society, 6(1), 284–313.

- Colombo, C. (2021, July 8). TikTok has apologized for a ‘significant error’ after a video that suggested racial bias in its algorithm went viral. Yahoo News. https://uk.news.yahoo.com/news/tiktok-apologized-significant-error-video-172818667.html

- Dukes, K. N., & Gaither, S. E. (2017). Black racial stereotypes and victim blaming: Implications for media coverage and criminal proceedings in cases of police violence against racial and ethnic minorities. Journal of Social Issues, 73(4), 789–807. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12248

- Dunn, J. L. (2010). Vocabularies of victimization: Toward explaining the deviant victim. Deviant Behavior, 31(2), 159–183. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639620902854886

- Everbach, T., Clark, M., & Nisbett, G. S. (2018). #Iftheygunnedmedown: An analysis of mainstream and social media in the Ferguson, Missouri, shooting of Michael Brown. Electronic News, 12(1), 23–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/1931243117697767

- Fairclough, N., & Wodak, R. (1997). Critical discourse analysis. In T. van Dijk (Ed.), Discourse studies: A multidisciplinary introduction (Vol. 2, pp. 258–284). Sage.

- Freelon, D., Lopez, L., Clark, M. D., & Jackson, S. J. (2018). How black Twitter and other social media communities interact with mainstream news [Preprint]. SocArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/nhsd9

- Freelon, D., McIlwain, C. D., & Clark, M. (2016). Beyond the hashtags: #Ferguson, #BlackLivesMatter, and the online struggle for offline justice (SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 2747066). Social Science Research Network. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2747066

- Gerbaudo, P. (2012). Tweets and the streets: Social media and contemporary activism. Pluto Press. http://www.oapen.org/search?identifier=642730

- Gracia, J. (2018). Towards an inclusive victimology and a new understanding of public compassion to victims: From and beyond Christie’s ideal victim. In M. Duggan (Ed.), Revisiting the ‘ideal victim’: Developments in critical victimology (pp. 297–312). Policy Press.

- Gruenewald, J., Chermak, S. M., & Pizarro, J. M. (2013). Covering victims in the news: What makes minority homicides newsworthy? Justice Quarterly, 30(5), 755–783. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418825.2011.628945

- Hautea, S., Parks, P., Takahashi, B., & Zeng, J. (2021). Showing they care (or don’t): affective publics and ambivalent climate activism on TikTok. Social Media+Society, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051211012344

- Jackson, S. J., Bailey, M., & Foucault Welles, B. (2020). #Hashtagactivism: Networks of race and gender justice. MIT Press.

- Jägervi, L. (2014). Who wants to be an ideal victim? A narrative analysis of crime victims’ self-representation. Journal of Scandinavian Studies in Criminology and Crime Prevention, 15(1), 73–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/14043858.2014.893479

- Jones, J. M. (2017). Killing fields: Explaining police violence against persons of color. Journal of Social Issues, 73(4), 872–883. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12252

- Langa, M., & Creswell, P. K. (2019). Aligned with the dead: Representations of victimhood and the dead in anti-police violence activism online. In T. Holmberg, A. Jonsson, & F. Palm (Eds.), Death matters: Cultural sociology of mortal life (pp. 199–220). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-11485-5_10

- Leopold, J., & Bell, M. P. (2017). News media and the racialization of protest: An analysis of Black Lives Matter articles. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal, 36(8), 720–735. https://doi.org/10.1108/EDI-01-2017-0010

- Lewis, R. (2020). ‘This is what the news won’t show you’: YouTube creators and the reactionary politics of micro-celebrity. Television & New Media, 21(2), 201–217. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527476419879919

- Litt, E. (2012). Knock, knock. Who’s there? The imagined audience. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 56(3), 330–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2012.705195

- Long, L. J. (2021). The ideal victim: A critical race theory (CRT) approach. International Review of Victimology, 27(3), 344–362. doi:10.1177/0269758021993339.

- Lowery, W. (2016, July 11). Aren’t more white people than Black people killed by police? Yes, but no. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/post-nation/wp/2016/07/11/arent-more-white-people-than-black-people-killed-by-police-yes-but-no/

- Machin, D., & Mayr, A. (2012). How to do critical discourse analysis: A multimodal introduction. Sage.

- Markham, A. (2012). Fabrication as ethical practice. Information, Communication & Society, 15(3), 334–353. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2011.641993

- Matamoros-Fernández, A. (2017). Platformed racism: The mediation and circulation of an Australian race-based controversy on Twitter, Facebook and YouTube. Information, Communication & Society, 20(6), 930–946. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2017.1293130

- Merrill, S., & Åkerlund, M. (2018). Standing up for Sweden? The racist discourses, architectures and affordances of an anti-immigration Facebook group. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 23(6), 332–353. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcmc/zmy018

- Nakamura, L. (2002). Cybertypes: Race, ethnicity, and identity on the internet. Routledge.

- Noble, S. (2018). Algorithms of oppression: How search engines reinforce racism. NYU Press.

- Nummi, J., Jennings, C., & Feagin, J. (2019). #BlackLivesMatter: Innovative Black resistance. Sociological Forum, 34(S1), 1042–1064. https://doi.org/10.1111/socf.12540

- Pew. (2021, April 7). Who uses TikTok, Nextdoor. Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/chart/who-uses-tiktok-nextdoor/

- Richardson, A. V. (2017). Bearing witness while black. Digital Journalism, 5(6), 673–698. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2016.1193818

- Richardson, A. V. (2020). Bearing witness while black: African Americans, smartphones, and the new protest #Journalism. Oxford University Press.

- Rose, G. (1997). Situating knowledges: Positionality, reflexivities and other tactics. Progress in Human Geography, 21(3), 305–320. https://doi.org/10.1191/030913297673302122

- Rose, G. (2016). Visual methodologies: An introduction to researching with visual materials (4th ed.). Sage Publishing.

- Slakoff, D. C., & Brennan, P. K. (2019). The differential representation of latina and black female victims in front-page news stories: A qualitative document analysis. Feminist Criminology, 14(4), 488–516. https://doi.org/10.1177/1557085117747031

- Smiley, C., & Fakunle, D. (2016). From ‘brute’ to ‘thug’: The demonization and criminalization of unarmed black male victims in America. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 26(3–4), 350–366. https://doi.org/10.1080/10911359.2015.1129256

- Sobande, F. (2020). Black women’s digital diaspora, collectivity, and resistance. In F. Sobande (Ed.), The digital lives of black women in Britain (pp. 101–129). Springer International.

- Sobande, F. (2021). Spectacularized and branded digital (re)presentations of black people and blackness. Television & New Media, 22(2), 131–146. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527476420983745

- Umamaheswar, J. (2020). Policing and racial (in)justice in the media: Newspaper portrayals of the ‘Black Lives Matter’ movement. Civic Sociology, 1(12143). https://doi.org/10.1525/001c.12143

- van Dijk, T. A. (1991). Racism and the press. Routledge.

- van Dijk, T. A. (2001). Multidisciplinary CDA: A plea for diversity. In R. Wodak & M. Meyer (Eds.), Methods of Critical discourse analysis (pp. 95–120). Sage.

- Vis, F., Faulkner, S., Noble, S. U., & Guy, H. (2019). When Twitter Got #woke: Black Lives Matter, DeRay McKesson, Twitter, and the appropriation of the aesthetics of protest. In A. McGarry, I. Erhart, H. Eslen-Ziya, O. Jenzen, & U. Korkut (Eds.), The aesthetics of global protest: Visual culture and communication (pp. 247–268). Amsterdam University Press. https://doi.org/10.5117/9789463724913

- Walker, D. (2021). ‘There’s a camera everywhere’: How citizen journalists, cellphones, and technology shape coverage of police shootings. Journalism Practice, 0(0), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2021.1884990

- Weimann, G., & Masri, N. (2020). Research note: Spreading hate on TikTok. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2020.1780027.

- Weiss, A., & Chermak, S. M. (1998). The news value of African-American victims: An examination of the media’s presentation of homicide. Journal of Crime and Justice, 21(2), 71–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/0735648X.1998.9721601

- Williams, M. L., Burnap, P., & Sloan, L. (2017). Towards an ethical framework for publishing Twitter data in social research: Taking into account users’ views, online context and algorithmic estimation. Sociology, 51(6), 1149–1168. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038517708140

- Wright, V., & Washington, H. M. (2018). The blame game: News, blame, and young homicide victims. Sociological Focus, 51(4), 350–364. https://doi.org/10.1080/00380237.2018.1457934

- Yancy, G. (2017). Black bodies, white gazes: The continuing significance of race in America (2nd ed.). Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Zimmer, M. (2018). Addressing conceptual gaps in big data research ethics: An application of contextual integrity. Social Media+Society, 4(2), 205630511876830. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305118768300