ABSTRACT

This article advances extant research that has audited search algorithms for misinformation in four respects. Firstly, this is the first misinformation audit not to implement a national but a cross-national research design. Secondly, it retrieves results not in response to the most popular query terms. Instead, it theorizes two semantic dimensions of search terms and illustrates how they impact the number of misinformative results returned. Furthermore, the analysis not only captures the mere presence of misinformative content but in addition whether the source websites are affiliated with a key misinformation actor (Russia’s ruling elites) and whom the conspiracy narratives cast as the malicious plotters. Empirically, the audit compares Covid-19 conspiracy theories in Google search results across 5 key target countries of Russia’s foreign communication (Belarus, Estonia, Germany, Ukraine, and the US) and Russia as of November 2020 (N = 5280 search results). It finds that, across all countries, primarily content published by mass media organizations rendered conspiracy theories visible in search results. Conspiratorial content published on websites affiliated with Russia’s ruling elites was retrieved in the Belarusian, German and Russian contexts. Across all countries, the majority of conspiracy narratives suspected plotters from China. Malicious actors from the US were insinuated exclusively by sources affiliated with Russia’s elites. Overall, conspiracy narratives did not primarily deepen divides within but between national communities, since – across all countries – only plotters from beyond the national borders were blamed. To conclude, the article discusses methodological advice and promising paths of research for future cross-national search engine audits.

Since early 2020, when Covid-19 began to spread across the globe, a seemingly infinite variety of narratives have surfaced suspecting secret plots behind the pandemic. Actors blamed as villains included the governments of states (like those of China, the USA, or Russia), companies (like those setting up 5G cellphone networks), international organizations (like the North Atlantic Treaty Organization [NATO] or the World Health Organization [WHO]), and wealthy individuals (like Bill Gates or George Soros). These actors were accused of a flurry of malign activities, amongst others of spreading the Coronavirus intentionally, of covering up accidents in military laboratories, and of ripping off the benefits of 5G-technologies that allegedly caused Covid-19 symptoms. In many countries across the globe, large proportions of the citizens came to believe in at least one of these narratives. In the US, for instance, as of March 2020, ‘31 percent believe[d] that the virus was created and spread on purpose. […] 30 percent believe[d] that the dangers of vaccines ha[d] been concealed, and 26 percent believe[d] as much about 5G technology’ (Uscinski & Enders, Citation2020).

In the academic literature, narratives as the ones indicated above are commonly referred to as ‘conspiracy theories’, prominently defined by Douglas et al. (Citation2019) as ‘attempts to explain the ultimate causes of significant social and political events and circumstances with claims of secret plots by […] powerful actors’ (Douglas et al., Citation2019, p. 4; see also Baden & Sharon, Citation2021; Sunstein & Vermeule, Citation2009; Uscinski, Citation2019; Yablokov, Citation2015, Citation2019; Yablokov & Chatterje-Doody, Citation2021). Grounded in this literature, this study understands by Covid-19 conspiracy theories all narratives that claim that one or several actors are (a) willfully exploiting the Covid-19 pandemic for their sinister goals and (b) intentionally seeking to conceal their malign deeds from the public. As visible from this understanding, conspiracy narratives typically cast one individual or group as the vicious ‘plotters’ (Radnitz, Citation2021, p. 17) while they strengthen the collective identity of another group as innocent and largely ignorant victims. Conspiracy theories, therefore, have been often instrumentalized by powerful political actors to further achieve their strategic goals, for instance, to vilify competitors or to rally supporters behind their flag (Fenster, Citation2008; Yablokov, Citation2015, Citation2019). Alongside populist politicians from Western democracies, in particular, Russia’s ruling elites have been widely accused of spreading conspiracy narratives across the global public (European External Action Service [EEAS], Citation2021; Yablokov, Citation2015, Citation2019; Yablokov & Chatterje-Doody, Citation2021).

Against this empirical backdrop, this study raises three overarching research questions: (1) To what extent were Internet users in five key target countries of Russia’s foreign communication and Russia (as a contrast case) exposed to conspiracy theories when searching for information about Covid-19? (2) To what extent did sources explicitly affiliated with Russia’s ruling elites contribute to the visibility of conspiracy narratives across the five contexts? (3) And who were the actors most widely vilified as plotters in search results across the five countries? By addressing these research questions, this study aims to contribute to the filling of two broader gaps in the academic literature. The first gap is identified in the recently vibrant strand of research that is systematically auditing the output of search algorithms for potentially detrimental social consequences (Hussein et al., Citation2020; Puschmann, Citation2019; Urman et al., Citation2021). This research has interrogated search algorithms for a wide range of alleged biases, including own-content bias and partisan bias. However, as Hussein et al. (Citation2020) have recently lamented, research that systematically audits search algorithms for misinformation is ‘practically non-existing’ (p. 6). The second gap is located in the interdisciplinary literature that scrutinizes how conspiracy theories are communicated in digitalized news media environments (Bruns et al., Citation2020; Gruzd & Mai, Citation2020; Uscinski, Citation2019; Yablokov, Citation2015, Citation2019). This branch of research, however, has focused on how conspiracy theories gain traction in pre-defined online spaces, most frequently in social networks (for recent studies, see Bruns et al., Citation2020; Gruzd & Mai, Citation2020). In contrast, the degree to which search algorithms contribute to the visibility of conspiracy theories remains scarcely investigated (for two exceptional studies, consider Ballatore, Citation2015; Hussein et al., Citation2020).

In order to fill these two gaps, this study simulates local language search queries via proxy servers purchased in Belarus, Estonia, Germany, Russia, Ukraine, and the US. We automatedly repeated all queries in three-day intervals (N = 11 search rounds) throughout the month of November 2020 – as one of the first months of the pandemic’s second wave, when case numbers were on the rise in all countries under investigation. In each search round, we fielded four search queries, translated in the local languages: covid + 19, covid + 19 + origin, covid + 19 + truth, and covid + 19 + conspiracy + theories (for a justification of query term choice, see method section). In a manual content analysis of the top 20 results retrieved for each query (N = 5280), we established codes related to the website’s content (whether undebunked conspiracy narratives were present, and who were the suspected plotters) and creators (type of website, geographical origin, affiliation with Russia’s ruling elites; by Russia’s ruling elites, this study specifically understands the country’s autocratic leader Vladimir Putin and his closest allies who govern the country).

As our findings show, across all contexts under scrutiny, the visibility of undebunked conspiracy narratives varied massively with two semantic dimensions of the search term, which we theorize as to the terms ‘encoding’ and ‘specificity’. We found that sources with close ties to Russia’s ruling elites contributed to the visibility of conspiratorial accounts in top Google results in three countries (Russia, Belarus, and Germany). At the most abstract level, Covid-19 conspiracy narratives did not deepen divides within but between national communities, since – across all contexts – primarily actors from beyond the national borders were suspected to stand behind the plot. Contextualizing and elaborating on these claims, the remainder of the article is structured as follows. The next section reviews the literature on the sociopolitical relevance of search algorithms with a focus on research that has audited web search engines for misinformation. A further section provides an overview of extant research on conspiracy theories, and in particular on how conspiracy narratives are communicated in digital information environments. The subsequent Methods section is followed by a section that presents findings. In the Discussion, we detail how this study advances extant research on search engines and conspiracy theories.

Search engines as powerful mediators of political information in the digital age

Web search engines are among the most powerful mediators of political information in digital media environments. According to the Reuters Institute Digital News Report (Newman et al., Citation2020), at the time of research, searching the web was one of the most popular ‘side door[s]’ (p. 23) to the news across the globe. Across all forty countries included in the Reuters study, on average, a quarter (25%) of respondents said to start their news journeys with a search engine (for similar evidence, see also Dutton et al., Citation2017). However, users turn to search engines not only for getting their news but also for facts. In a survey conducted across six European countries and the US in January 2017, Dutton et al. (Citation2017) found that the average respondent went online to ‘find or check a fact’ (p. 28) at least once a day. Only two activities were pursued more frequently on the Internet: to ‘read or send an email’ and to ‘look for news online’ (Dutton et al., Citation2017, p. 28). Both practices – searching for the news and searching for facts – are of pivotal importance in the context of this study, which centers on queries targeting the Covid-19 pandemic. As Google trends data show, across the countries under investigation, search terms like ‘Corona’ and ‘Coronavirus’ were among the top queries throughout the year 2020 (Google Trends, Citation2021).

Auditing search engines for misinformation

As Hussein et al. (Citation2020) define, an audit is the ‘systematic statistical probing of an online platform to uncover societally problematic behavior underlying its algorithms’ (p. 6). Within the field of political communication, scholars have investigated, for instance, how political candidates and parties are represented in search results (Puschmann, Citation2019; Urman et al., Citation2021), how diverse the content is that search engines provide on political issues (Steiner et al., Citation2020), and how personalized the results lists are that algorithms return to their users (Haim et al., Citation2018). In contrast, as Hussein et al. (Citation2020) have recently lamented, research ‘auditing online platforms for algorithmic misinformation is practically non-existing’ (p. 6; see also Bandy, Citation2021).

In order to fill this gap, Hussein et al. (Citation2020) conducted a series of audits of the search function of the video-sharing platform YouTube in the context of five conspiracy theories (‘9/11’, ‘chemtrails’, ‘flat earth’, ‘moonlanding’, and ‘vaccines’, p. 19). As they find, the proportion of search results that promoted conspiracy narratives varied massively between 10% and 75%, depending on the specific conspiracy theory targeted by the search queries. In addition to Hussein et al. (Citation2020), we could identify two further studies that have audited search algorithms for conspiracy theories. The first of these studies, Ballatore (Citation2015), retrieved from the search engines Google and Bing results in response to the six most popular search terms targeting 15 conspiracy theories. In Ballatore’s (Citation2015) study, the proportion of results containing conspiratorial content varied between 14.7% and 90.1%. In a further study, Madden et al. (Citation2012) systematically analyzed the 89 top search results from Google, Yahoo, Bing, and Ask.com in response to six general search terms related to human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines. In their sample, only two websites (2%) referred to conspiracy theories.

This article seeks to advance extant research that audits search engines for misinformation in four aspects. Firstly, extant audits have used search terms only in one language (Ballatore, Citation2015; Hussein et al., Citation2020; Madden et al., Citation2012). In contrast, this study implements the first cross-national audit for misinformation, comparing results in response to query terms in six languages, and simulating six national geolocations via proxy servers. Secondly, extant audits have focused on the most popular search terms, while not reflecting on how the meaning of terms may affect the amount of misinformation retrieved (Ballatore, Citation2015; Hussein et al., Citation2020; Madden et al., Citation2012). In contrast, this study proposes and tests a series of hypotheses on how two semantic dimensions, which we theorize as the specificity and ‘encoding’ (Hall, Citation1980, p. 117) of a search term, impact results. Thirdly, extant studies have audited results for the mere presence of misinformation or conspiratorial content (Ballatore, Citation2015; Hussein et al., Citation2020). In contrast, our analysis is grounded in a more extensive coding effort. Most importantly, we included a coding item that identified the political ‘other’, i.e., the actors who took on the roles of ‘villains’ (Uscinski, Citation2019, p. 15) or malicious ‘plotters’ (Radnitz, Citation2021, p. 17) in the conspiratorial narratives. Fourthly, and relatedly, extant research has limited its scope to identifying the type of sources that spread misinformation, for instance, news websites, wikis, and blogs (Ballatore, Citation2015; Madden et al., Citation2012). In contrast, our coding scheme also identifies the actor who controls the source that spreads the misinformative content. Specifically, we interrogate the influence of Russia’s ruling elites.

Conspiracy theories, misinformation and disinformation

Before we develop hypotheses and research questions, we need to clarify how our key theoretical concept (conspiracy theory) relates to the notions of mis- and disinformation. To begin with, conspiracy theories are commonly analyzed in the academic literature as allegations of conspiracy that ‘may or may not be true’ (Douglas et al., Citation2019, p. 4; see also Radnitz, Citation2021; Sunstein & Vermeule, Citation2009). Thus, while some conspiracy theories may turn out to be factually true later, the key defining element of the concept is that ‘credible evidence’ to support the conspiratorial claim is not ‘available to the public or verified by reliable sources at the time’ (Radnitz, Citation2021, p. 8) when the claim is made.

Misinformation, in contrast, is frequently understood as time-independent, ‘objectively incorrect information’ (Bode & Vraga, Citation2015, p. 621). However, particularly in the field of political communication, it too has turned out a challenge for scholars to neatly separate correct from incorrect information, with many operationalizations relying on reference to an ‘expert consensus’ (Vraga & Bode, Citation2020, p. 137) to make this distinction (Ha et al., Citation2021; Hussein et al., Citation2020). Vraga and Bode (Citation2020), for instance, propose to distinguish misinformation issues for which the expertise and evidence are (a) both ‘clear and settled’, (b) ‘emerging’ or (c) ‘controversial’ (p. 141). This categorization thus also incorporates a dynamic element.

In the context of this study, for example, the conspiracy narrative that the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 had escaped from a laboratory in Wuhan, with Chinese elites and/or scientists conspiring to hide the accident from the public, may be considered an issue on which an expert consensus was ‘emerging’ (Vraga & Bode, Citation2020, p. 141). At the time of data collection in November 2020, an overwhelming majority of scientists considered this scenario highly unlikely. Thus, ‘credible evidence to support the claim’ (Radnitz, Citation2021, p. 18) was not available to the public at that time. That said, a minority of experts, including some academics working at elite universities with high repute, demanded further investigation (consider, as an academic article that appeared in our data set, Relman, Citation2020). In this paper, we focus exclusively on conspiracy theories that were rejected at least by the overwhelming majority of reputable experts at the time of research (‘emerging’ or ‘settled expert consensus’; Radnitz, Citation2021; Vraga & Bode, Citation2020, p. 141) and for which credible evidence was not available to the public. It is in this sense that we consider the conspiracy theories identified in this study misinformation. However, we cannot exclude (1) that some of the conspiracy narratives identified in the analysis are true, even though credible evidence will never become publicly available or (2) that credible evidence for other conspiracy narratives (e.g., the Wuhan-lab-leak-theory) surfaces after this article is published. It is grounded in these definitions that our audit can be understood as an audit for misinformation.

Disinformation, finally, is commonly defined as misinformation that is spread on purpose and with malicious intent (Ha et al., Citation2021; Bennet & Livingstone, Citation2018). While it frequently is a thorny issue to ‘ascertain the intention of the message’ (Ha et al., Citation2021, p. 291), straightforward examples of disinformation mentioned in the literature include ‘deceptive political and commercial advertisements, government propaganda, forged documents, Internet frauds, fake websites, and manipulated Wikipedia entries’ (Ha et al., Citation2021, p. 291). According to this understanding, the conspiracy theories identified in this audit may be considered disinformation, if they are spread by communication outlets operated by, or having close ties with, national governments or ruling political elites.

Developing hypotheses and research questions

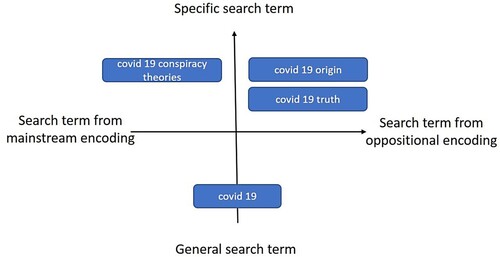

Query terms: distinguishing between mainstream and oppositional encodings

In the following, we theorize two semantic dimensions of search queries to impact the number of misinformative results retrieved (for visualization, see ). The first dimension is what we refer to as the specificity of the search term, i.e., the precision with which the search term targets the misinformation issue under scrutiny. Within this dimension, search terms can be located on a continuum from highly specific to highly abstract. To illustrate this with an example, consider again the Covid-19 conspiracy theory that Chinese officials are intentionally hiding from the public that the virus escaped from a laboratory. With regard to this narrative, the following search queries may be seen as gradually increasing in specificity: ‘Covid 19’, ‘Covid 19 origin’, ‘Covid 19 laboratory’, ‘Covid 19 Chinese laboratory conspiracy theories’. As such ‘linguistic cues’ are among the ‘primary components that make up the rules in a search engine algorithm’ (Granka, Citation2010, p. 366; see also, Kravets & Toepfl, Citation2021), we can plausibly assume that more specific search terms will retrieve higher proportions of results about a misinformation issue. We thus hypothesize:

H1: The higher the degree of specificity with which a search term targets popular Covid-19 conspiracy theories, the greater will be the proportion of misinformative results returned.

Figure 1. Two semantic dimensions of search terms affecting the amount of misinformative results retrieved.

However, not all search terms with similar levels of specificity retrieve equal numbers of misinformative results. Consider the most specific search term among the ones listed above: ‘Covid 19 Chinese laboratory conspiracy theories’. As Fenster (Citation2008) has argued, in many sociopolitical contexts, ‘the label “conspiracy theorist” insinuates that a person is extreme, threatening, nuts’ (p. 1). Accordingly, the term ‘conspiracy’ is typically avoided by individuals who agitate for these narratives. As search algorithms operate on the basis of linguistic cues (Granka, Citation2010), it can be plausibly assumed that any search query that includes the term ‘conspiracy’ will retrieve primarily results that debunk conspiracy theories, since these are the only accounts that will explicitly label these narratives as ‘conspiracy theories’. Against this backdrop, we theorize as a second semantic dimension whether the search query can be considered as pertinent to what Hall (Citation1980) has classically referred to as the ‘dominant’ (in the sense of mainstream) or the ‘oppositional’ (p. 18) discourse about a misinformation issue (see also Toepfl, Citation2013). In this understanding, in our example, the term ‘conspiracy’ can be considered pertinent to mainstream discourse, whereas revealing the ‘truth’ about the real ‘origin’ of the virus can be considered pertinent to ‘oppositional’ (Hall, Citation1980, p. 127) encodings. Accordingly, we hypothesize:

H2: Across all countries, search terms that exclusively occur in the mainstream narratives about Covid-19 conspiracy theories (e.g., ‘conspiracy’) will retrieve fewer misinformative results, by comparison with search terms that occur also in oppositional encodings (e.g., ‘origin’ or ‘truth’).

Countries: comparing the visibility of conspiracy theories in search results across contexts

Extant audits for misinformation have typically used search terms only in one language (English) and not implemented cross-nationally comparative research designs (Ballatore, Citation2015; Hussein et al., Citation2020; Madden et al., Citation2012). This is unsatisfactory because, as critical scholars have long argued, algorithms should not be analyzed as detached technological artifacts but ‘as relational, contingent, contextual in nature, framed within the wider context of their socio-technical assemblage’ (Kitchin, Citation2017, p. 18). For similar reasons, Hussein et al. (Citation2020) have called for ‘conducting audits over a global scale’ as a ‘fertile area for future endeavors’ (p. 22). Taking the first step towards filling this gap, this study implements a cross-national audit for misinformation that simulates queries from six country contexts. The interdisciplinary literature on conspiracy theories offers little leverage to develop hypotheses about whether some of the national communication environments included in this study should be more prone to the circulation of conspiracy theories than others. Presently, as Uscinski (Citation2019) laments ‘[m]ost accounts of conspiracy theorizing focus on a single place […] Researchers need to provide more cross-cultural studies so that we can understand which groups are the most conspiracy minded and why’ (p. 334; for further calls for comparative research on conspiracy theories, see Drochon, Citation2019; Douglas et al., Citation2019). Grounded in initial survey data on conspiracy beliefs across European populations , Drochon (Citation2019) has suggested that ‘[p]oorer and less democratic countries’ tend to ‘return higher levels of conspiracy theories than those who do better’ (p. 337). For a similar carefully worded argument on the potential ‘association of dictators with conspiracy theories’, refer to Radnitz (Citation2021, p. 15). As the extant research does not provide sufficient substance to devise a directed hypothesis about the proportion of conspiracy theories returned by the Google search algorithm across the six contexts, we formulate the following open research question:

RQ1: How does the visibility of conspiracy theories in search results vary across the six countries under investigation?

Source type: websites responsible for the visibility of conspiracy theories in results

Deploying sets of highly specific (English language) query terms (which randomly included terms of what we would refer to as ‘mainstream’ and ‘oppositional’ encodings), Ballatore (Citation2015) found that the following sources dominated the results retrieved: blogs (66.6%), wikis (11.1%), news outlets (15.2%) and academic platforms (4.7%). However, Ballatore (Citation2015) – just like Madden et al. (Citation2012) – did not raise the question of whether different types of sources disseminated confirmatory, neutral or debunking accounts of the suspected conspiracies. Moreover, extant research offers no conclusion as to how and why source types might vary by country context. In order to fill this gap, this study asks:

RQ2: What types of sources contribute most to the visibility of undebunked accounts of conspiracy theories (RQ2a) and how do sources vary by country (RQ2b)?

Source control: the influence of Russia’s digital foreign communication efforts

As has been argued, conspiracy theories are widely deployed in the context of Russia’s foreign communication efforts as a ‘political instrument’ in order to ‘legitimise Russian domestic and foreign policies and, in turn, delegitimise policies of the American government’ (Yablokov, Citation2015, p. 301; see also EEAS, Citation2021; Watanabe, Citation2018; Yablokov, Citation2019). However, no study to date has audited the degree to which misinformative content sponsored by Russia’s ruling elites is rendered visible by web search algorithms. In order to fill this gap, this study raises the research question:

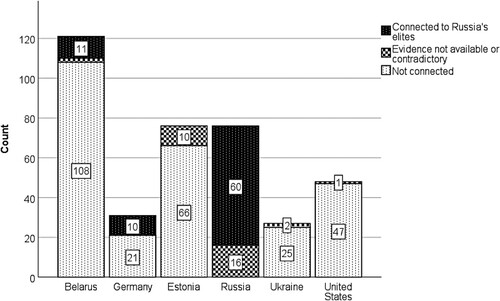

RQ3: Across the six countries under investigation, to what extent does the content of websites connected with Russia’s political elites contribute to the visibility of undebunked conspiracy theories?

Political consequences: who suspects whom behind the conspiracy?

Understood as a ‘populist theory of power’, conspiracy theories commonly formulate a binary opposition between ‘us’ and ‘them’, between ‘the people’ and a ‘relatively secret, elite “power bloc”’ (Fenster, Citation2008, p. 89). Therefore, as Yablokov (Citation2019) has argued, conspiracy theories can become a powerful tool in ‘popular mobilization, and they can also help to destroy the reputations and legitimation of political opponents’ (p. 362; see also Fenster, Citation2008; Radnitz, Citation2021; Watanabe, Citation2018; Yablokov, Citation2015). Extant audits of search algorithms have been limited to measuring the visibility of debunked, neutral or promoting misinformation narratives in search results (Ballatore, Citation2015; Hussein et al., Citation2020; Madden et al., Citation2012). In contrast, this study is the first to focus on who is suspected as ‘villains’ (Uscinski, Citation2019, p. 15) behind the plots in the conspiratorial narratives. Accordingly, we formulate two research questions:

RQ4: Across the six countries under investigation, who were the actors suspected behind the plots in (a) result pages and (b)specifically in result pages connected with Russia’s ruling elites?

Methods

Selection of conspiracy theories, search engines, search terms, and country cases

With regard to the country selection, our rationale was to sample five prime target countries of Russia’s foreign communication that varied widely in terms of (a) political power and (b) strategic relationship with Russia’s ruling elites (friendly vs. adversarial). Accordingly, we chose the US and Germany (as two powerful Western nations, with Russia considering the US its key opponent and Germany, by comparison, as friendlier to Russia [Yablokov, Citation2015, Citation2019]). Moreover, we included Belarus, Estonia and Ukraine in the analysis (as three less powerful polities in Russia’s immediate neighborhood, considered by Russia as falling within her sphere of influence to different degrees). We added the domestic Russian context as a contrast case. From the range of available search engines, we chose Google because it is the platform with the largest market share globally, as well as across the countries under investigation (with the exception of Russia, see Kravets & Toepfl, Citation2021). In 2017, Google publicly announced to ‘de-rank’ (Hern, Citation2017) news websites affiliated with Russia’s ruling elites who spread misinformative content. This audit can thus be seen as a check on the consequences of the company’s efforts in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic. As a time period for the audit, we opted for November 2020 as one of the initial months of the second wave of the pandemic at the global level, when infections were on the rise across all countries under investigation. We selected four query terms that differed qualitatively along the two semantic dimensions of search terms proposed in the previous section (see ). We deployed these query terms translated into the local languages of the five countries (for a list of translated search terms, see the online supplementary file).

Automated data collection

For data collection, we created Python scripts that automatedly retrieved results in response to the four query terms in three-day intervals throughout November 2020 (N = 11 search rounds). We fielded the queries at random daytimes through depersonalized http requests, using proxy servers to simulate IP addresses from the countries under investigation. For each country, we used the local country version of Google (e.g., google.de for Germany) and set the web interface language to the local language (appending ‘&hl = de’ to the URL for Germany). We also used Google’s option of showing search results as they would appear in the country of search (appending ‘&gl = DE’ to the URL). For each of the first 20 organic entries to the search engine result page, we scraped amongst others the title, the search snippet, the link, as well as the full text of the website to which the result was linked. We obtained a data set of N = 5.280 results.

Manual data analysis

In order to analyze these results, we deployed manual quantitative content analysis. The coding effort was implemented by three co-authors of the study and one research assistant, who were native or fluent in the six local languages of the countries under investigation. For some of the variables, achieving satisfactory levels of intercoder agreement required extensive training of coders and the development of fine-grained coding instructions. Consider for instance the key variable on which our analysis draws, which concerns whether a result page contains at least one conspiracy theory that is not ‘forcefully debunked’ (see ). As our coders found, many result pages that were overall supportive of a conspiratorial claim included at least one argument that apparently ‘debunked’ this claim – but was then systematically disproved. Other result pages did not explicitly state that a conspiratorial claim was true. Instead, they presented the audience with a set of unanswered rhetorical questions and/or insinuations that pushed readers to make their ‘own’ conclusions. The third type of website countered one or several conspiracy narratives, but explicitly supported others. We instructed our coders to categorize websites of all these types as containing ‘at least one conspiracy theory that was not forcefully debunked’. We provide detailed information on how all variables were coded in the supplementary materials to this article, alongside examples of coded websites, the full data set, the Python scripts deployed for data collection, and Krippendorff’s alpha for all variables. Intercoder reliability tests resulted in the following satisfactory values for Krippendorff’s alpha for the key variables used in the subsequent analysis: Presence of Conspiracy Theories (α = .86), Type of Source (α = .84), Russia’s Influence on Source (α = .92), and Geographical Origin of Plotter (α = .72).

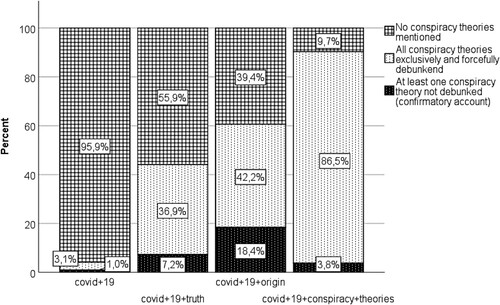

Figure 2. Proportion of conspiracy theories retrieved by search term aggregated over six countries (N = 5280).

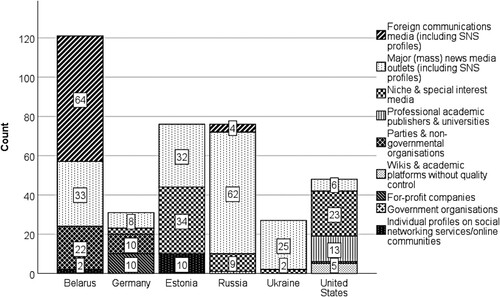

Figure 3. Result pages featuring conspiracy theories by source type (total N = 880 result pages per country).

Findings

Query choice: how conspiracy theories retrieved vary by search term

visualizes our results with regard to query term choice. As hypothesized in H1, across the six countries under investigation, the proportion of undebunked conspiracy narratives significantly increased from the unspecific query covid + 19 (1.0%) to the more specific queries in the oppositional encoding, covid + 19 + truth (7.2%) and covid + 19 + origin (18.4%). While these proportions are calculated on the basis of 5,280 observations, standard statistical tests cannot be applied to this data set because these observations are correlated within countries and between consecutive search rounds. As the assumption of independence of observations is thus violated, we deploy a most cautious approach to statistical testing. We conduct a non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test that compares the proportion of undebunked conspiracy theories, as averaged over the 11 search rounds, across the six countries: (a) in response to the unspecific query term covid + 19 (N = 6 observations) and (b) in response to the two specific query terms covid + 19 + truth and covid + 19 + origin (N = 12 observations). We find a significant effect of search term specificity (U = 6.50, p = .005). H1 is thus supported.

H2 hypothesized that, across all countries, search terms that are exclusive to the mainstream narrative about Covid-19 misinformation narratives (covid + 19 + conspiracy + theories) will retrieve fewer misinformative results, by comparison with search terms widely deployed also in oppositional encodings (i.e., covid + 19 + origin and covid + 19 + truth, see ). As illustrates, covid+19 + conspiracy + theories indeed retrieved results that are patterned in fundamentally different ways. Of all four search terms, this query retrieves by far the largest proportion of more than 90% of results that mention conspiracy theories. However, only 3.8% of results are these conspiracy narratives not explicitly debunked. Again, we conducted a non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test that compares the mean proportion of the undebunked conspiracy theories across the five countries: (a) in response to the query term in the mainstream encoding (covid + 19 + conspiracy + theory, N = 6 observations) and (b) in response to the two query terms occurring also in oppositional accounts (covid + 19 + truth and covid+19 + origin, N = 12). We found a significant effect of search term encoding (U = 14.00, p = .04). Our data thus support H2.

Sociopolitical context: how conspiracy theories retrieved vary by country

RQ1 asked how the visibility of conspiracy theories varied between the five countries under investigation. According to our findings, the proportion of undebunked conspiracy theories retrieved by Google in response to local language search terms varied massively between country contexts. The share of undebunked narratives decreased from Belarus (14.4%) to Estonia (10.0%), Russia (8.6%), the USA (5.6%), Germany (3.6%) and Ukraine (3.2%).

Sources: how distinct types of websites contribute to the visibility of conspiracy theories

RQ2a asks which sources contributed to the visibility of undebunked conspiracy theories across the five countries under investigation. Across all countries, our data set contained 379 results (7.5%) that explicitly propagated at least one conspiracy theory. Of these confirmatory narratives, the overwhelming majority of 80.5% (305) were spread by mass media. More specifically, 43.8% (166) of conspiratorial accounts were published by major national mass media, 18.7% (71) by niche and special interest media, and 17.9% (68) by foreign communication outlets. A further 8.7% (33) originated from websites affiliated with parties and non-governmental organizations.

illustrates how the role of distinct types of sources varied by country (RQ2b). At least three patterns appear noteworthy. First of all, the US context is the only one in which content published by academic publishers of different repute and wikis contribute to the spread of conspiracy narratives. Secondly, in the two most developed democracies, the USA and Germany, major mass media appear to largely refrain from spreading conspiratorial narratives. In contrast, in the US, what we categorized as niche and special interest media play a key role, such as for example, www.genengnews.com or www.independentsciencenews.org. And thirdly, in Belarus, we see a large number of results being contributed by foreign communication outlets, which were Belsat TV (Poland) and Sputnik (Russia). In Germany, conspiratorial narratives entered search results through a self-published book sold on Amazon (for-profit source) as well as through a video published by the YouTube channel of the Austrian right-wing party FPÖ (Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs).

Source control: gauging the influence of Russia’s ruling elites

RQ3 asks how many of the sources propagating conspiracy theories were connected with Russia’s ruling elites? As visualizes, sources affiliated with Russia’s ruling elites did not contribute to the visibility of conspiracy theories in search results in the US, Estonia and Ukraine. In contrast, they appeared in search results in Germany and Belarus. In Belarus, Russia’s influence was mediated through a conspiratorial article published by the foreign communication outlet Sputnik, which consistently appeared in ranks between 4 and 6 in the 11 search rounds in response to the query term covid+19 + origin. In Germany, we coded as implicit Russian influence the visibility of a conspiratorial YouTube video published by the Austrian far right-wing party FPÖ, whose informal ties with Russia’s elites caused the collapse of the Austrian coalition government in 2019 (for details, see Weiss, Citation2020).

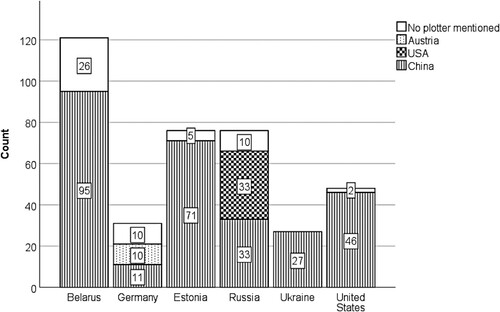

Plotters: the villains suspected behind the pandemic

As demonstrates, across the five countries under investigation, conspiracy narratives clearly contributed to damaging the reputation of political actors: virtually all narratives (86%) mention plotters, explicitly identifying their geographical origins. The overwhelming majority of 283 result pages (74.7%) suspected plotters from China, followed by plotters from the USA (33, 8.7%) and from Austria (10, 2.6%; RQ4a, see ). Notably, all undebunked Covid-19 conspiracy narratives in our sample did not suspect domestic but exclusively foreign villains behind the plot. Finally, RQ4b asked who were the plotters suspected by sources affiliated with Russia’s ruling elites? In this category of sources, the focus of the blame is distinct. Of 81 conspiratorial results, 33 (40.7%) suspect plotters affiliated with the USA, 32 (39.5%) from China, and 10 (12.3%) from Austria. In our sample, plotters from the US are thus suspected behind the plot exclusively by sources affiliated with Russia’s ruling elites.

Discussion

Query terms: how their semantic characteristics impact misinformation retrieval

Extant audits of search engines have typically assessed results retrieved in response to the most popular search terms (Ballatore, Citation2015; Hussein et al., Citation2020; Madden et al., Citation2012). In contrast, this study has been the first to reflect upon how semantic characteristics of search terms may impact the amount of misinformation retrieved. More specifically, we theorized the two semantic dimensions of ‘specificity’ and ‘encoding’ (see ). As our findings demonstrate, the two dimensions indeed affected the proportion of conspiratorial accounts retrieved in the directions hypothesized. Our analysis thus vividly illustrates how the outcome of any algorithmic audit may fundamentally change as a consequence of what might be erroneously understood as ‘minor rewordings’ of the search queries (see H1, H2). Future misinformation audits should thus either deploy search terms covering the entire range of specificity (unspecific to specific) and encodings (from oppositional to mainstream), or reflect upon how the search terms audited are to be positioned within the two-dimensional semantic space delineated in . Doing so will facilitate more nuanced assessments of the extent to which a search algorithm contributes to the dissemination of misinformation in response to distinct query terms. To illustrate this, an example, Hussein et al. (Citation2020) audited the search function of the video-sharing platform YouTube for ‘9/11 conspiracy theories’ by jointly deploying, within one set of search terms, the search queries ‘9/11 inside job’ (highly specific/oppositional encoding) and ‘9/11 conspiracy theories’ (highly specific/dominant encoding). In their analysis, they averaged results over these two search terms. However, as our findings indicate (see e.g., ), it appears highly plausible that the patterns of conspiratorial content retrieved for the two terms differed fundamentally.

Comparing across countries: the mass media’s key impact on the visibility of conspiracy narratives

Extant research has audited algorithms for misinformation by simulating queries in one national sociopolitical context only (Ballatore, Citation2015; Hussein et al., Citation2020; Madden et al., Citation2012). In contrast, this is the first audit to compare the amount of misinformation retrieved for the same search queries posted in six different languages and from six different geolocations. As our data show, the amount and type of misinformation retrieved by the Google algorithm varied massively between the six sociopolitical contexts. These findings add emphasis to Kitchin’s (Citation2014) admonition that algorithms must not be considered as detached technological artefacts or pieces of code, but that ‘understanding the work and effects of algorithms needs to be sensitive to their contextual, contingent unfolding across situation, time and space’ (p. 21).

The reasons for why different proportions of conspiracy theories appear in search results across contexts appear to be complex. Our findings are, for instance, not fully in line with the preliminary evidence that has indicated that conspiracy beliefs may be more commonly encountered in ‘[p]oorer and less democratic countries’ (Drochon, Citation2019, p. 336). That said, several important conclusions can be drawn from our findings – and should be further interrogated in future research. Firstly, as illustrates, across the democratic and non-democratic countries under investigation, only a small number of non-media websites managed to appear in search results. In contrast, the overwhelming majority (80.5%) of all conspiratorial narratives returned by the search algorithm were published by local language mass media websites. Secondly, we further subdivided the mass media category into (1) major mainstream mass media, (2) niche and special interest media, and (3) foreign communication media. As illustrates, the contribution of these three subtypes differed massively across the six-country contexts. In Russia, the majority of undebunked conspiracy theories were contributed by major mainstream media, in the United States by niche media, and in Belarus by foreign communication media. Thirdly, the substantial cross-country differences in the total numbers of conspiratorial results retrieved (see ) resulted from differences in the numbers of conspiratorial mass media articles returned. As these findings indicate, overall, the visibility of conspiracy theories in Google search results depended, in large measure, on the degree to which local language mass media (be they of domestic or foreign origin) picked up and disseminated the conspiratorial claims.

As these conclusions indicate, the search queries conducted for this study were not fielded in situations that Golebiewski and boyd (Citation2019) have prominently theorized as ‘data voids’, i.e., in ‘low-quality data situations’ in which search algorithms return ‘low quality or low authority content because that’s the only content available’ (p. 5). In contrast, in our analysis, the visibility of conspiracy claims resulted from a small number of deviant items published on a type of website (mass media) that search algorithms commonly consider ‘authoritative’ (Golebiewski & boyd, Citation2019, p. 27). Notably, however, in our data set collected for November 2020, journalistic articles supporting conspiracy theories were on average almost two months older than media articles debunking these narratives (average publication dates: 31 July 2020 vs. 6 June 2020). Against this backdrop, it could be argued that older media reports confirming conspiracy theories were overrepresented in search results, by comparison with more recent journalistic articles debunking conspiracy theories (which might be considered more up-to-date and thus of better quality).

Instrumentalizing misinformation: what conspiracy narratives were spread by whom

While extant research has shown that conspiracy theories are vigorously spread by Russia’s foreign communication outlets and used as a ‘political instrument’ (Yablokov, Citation2015, p. 301; see also EEAS, Citation2021; Watanabe, Citation2018; Yablokov, Citation2019), this study finds that conspiratorial articles published by Russia’s official foreign communication outlets did not manage to enter the first 20 results in three of the five-country contexts under scrutiny (the US, Germany, and Ukraine). This is most likely due to Google’s explicit decision to ‘de-rank’ sources affiliated with the Kremlin (Hern, Citation2017). However, sources officially affiliated with Russia’s ruling elites were still visible from Belarus, and omnipresent in the Russian domestic context. Moreover, our audit found implicit influence (through content published by a far-right Austrian party with close ties to the Kremlin) even in the German context. With regard to who was suspected as the plotter (see ), the tendency in our data towards blaming Chinese actors can be partly attributed to query term choice: one of our search terms, covid + 19 + origin, had a high degree of specificity with regard to Wuhan-laboratory conspiracy narratives. Yet, from within Russia, our audit still retrieved results that blame plotters from China and the US in roughly equal measure. This is in line with Yablokov’s claim that Russia’s ruling elites primarily seek to ‘delegitimise policies of the American government’ (Yablokov, Citation2015, p. 301; see also EEAS, Citation2021; Yablokov, Citation2019), which they see as their key opponent on the international stage. At the same time, considering that the remaining three query terms did not target the Wuhan-laboratory-escape narrative, it appears noteworthy that not a single conspiratorial narrative blamed a domestic villain, be it an ethnic or religious minority or the country’s own elites. This finding suggests that, across all countries, conspiracy theorizing around Covid-19 took on a peculiarly populist and nationalistic guise, deepening divides between national communities – rather than within them.

Limitations and paths for future research

This concluding section highlights the limitations of this audit and points to promising paths for future research. First of all, this study has audited only four query terms, in only six contexts, and on only one misinformation issue (Covid-19). Yet, one of our main conclusions is that the findings of an audit will not easily generalize from one sociopolitical context to others, and from one query term to others. Future research thus needs to collect evidence from across other contexts, on other issues, and on other query terms that add substance to some of the indicative conclusions of this article, as for instance, those on which type of sources dominate results, and what actors control the sources retrieved in different contexts. Notably, the search terms deployed in our study were not evenly spread across the four quadrants of . Future research should thus systematically interrogate the amount of misinformation retrieved in response to a wide variety of search terms of distinct semantic positioning. Secondly, this research has audited only one algorithm, Google web search. Future research needs to gauge how other algorithms perform – for instance, those of Russia’s own partly state-controlled search company Yandex. Thirdly, due to limited resources for manual coding, this study is based on the analysis of only 5,280 results. In order to create larger data sets, future research needs to take up the complex challenge of developing valid methodological approaches for automated text analysis of conspiracy narratives. This will allow for extending the scope of misinformation audits to longer time periods. By taking up at least these three challenges, future research will enhance our knowledge of how search algorithms contribute to the spread of misinformation online, and what can be done to prevent the detrimental social consequences thereof.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (868.8 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Florian Toepfl

Florian Toepfl is a Professor at the University of Passau, Germany, where he holds the Chair of Political Communication with a Focus on Eastern Europe and the Post-Soviet Region. He is Principal Investigator of a ERC Consolidator Project on “The Consequences of the Internet for Russia’s Informational Influence Abroad” (Acronym: RUSINFORM).

Daria Kravets

Daria Kravets is a PhD Candidate in Political Communication at the University of Passau and a researcher at the ERC Consolidator Project RUSINFORM. Her research focuses on search engines as mediators of foreign influence.

Anna Ryzhova

Anna Ryzhova is a PhD Candidate and Researcher at the ERC Consolidator Project RUSINFORM (University of Passau). The main focus of her research lies on the Russian-speaking audiences in Germany and their practices of news use and news trust.

Arista Beseler

Arista Beseler is a PhD Candidate and Researcher at the ERC Consolidator Project RUSINFORM (University of Passau). In her research, she focuses on German alternative media and their role as disseminators of pro-Russian content.

References

- Baden, C., & Sharon, T. (2021). Blinded by the lies? Toward an integrated definition of conspiracy theories. Communication Theory, 31(1), 82–106. https://doi.org/10.1093/ct/qtaa023

- Ballatore, A. (2015). Google chemtrails: A methodology to analyze topic representation in search engine results. First Monday, 20(7), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v20i7.5597

- Bandy, J. (2021). Problematic machine behavior: A systematic literature review of algorithm audits. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 5(74), 1–34. https://doi.org/10.1145/3449148

- Bennett, W. L., & Livingston, S. (2018). The disinformation order: Disruptive communication and the decline of democratic institutions. European Journal of Communication, 33(2), 122–139. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0267323118760317

- Bode, L., & Vraga, E. K. (2015). In related news, that was wrong: The correction of misinformation through related stories functionality in social media. Journal of Communication, 65(4), 619–638. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jcom.2015.65.issue-4

- Bruns, A., Harrington, S., & Hurcombe, E. (2020). ‘Corona? 5G? Or both?’ The dynamics of COVID-19/5G conspiracy theories on Facebook. Media International Australia, 177(1), 12–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/1329878X20946113

- Douglas, K. M., Uscinski, J. E., Sutton, R. M., Cichocka, A., Nefes, T., Ang, C. S., & Deravi, F. (2019). Understanding conspiracy theories. Political Psychology, 40(S1), 3–35. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12568

- Drochon, H. (2019). Who believes in conspiracy theories in Great Britain and Europe? In J. Uscinski (Ed.), Conspiracy theories and the people who believe them (pp. 337–346). Oxford University Press.

- Dutton, W. H., Reisdorf, B. C., Dubois, E., & Blank, G. (2017). Search and politics: The uses and impacts of search in Britain, France, Germany, Italy, Poland, Spain, and the United States. SSRN Electronic Journal. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2960697

- European External Action Service. (2021, April 28). Short assessment of narratives and disinformation around the COVID-19 pandemic. Retrieved August 23, 2021, from https://euvsdisinfo.eu/eeas-special-report-update-short-assessment-of-narratives-and-disinformation-around-the-covid-19-pandemic-update-december-2020-april-2021/

- Fenster, M. (2008). Conspiracy theories: Secrecy and power in American culture. University of Minnesota Press.

- Golebiewski, M., & boyd, d. (2019, October 29). Data voids. Data & society. https://datasociety.net/library/data-voids/

- Google Trends. (2021). Das war 2020 angesagt: Deutschland. Retrieved July 27, 2021, from https://trends.google.com/trends/yis/2020/DE

- Granka, L. A. (2010). The politics of search: A decade retrospective. The Information Society, 26(5), 364–374. https://doi.org/10.1080/01972243.2010.511560

- Gruzd, A., & Mai, P. (2020). Going viral: How a single tweet spawned a COVID-19 conspiracy theory on twitter. Big Data & Society, 7(2), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951720938405

- Ha, L., Andreu Perez, L., & Ray, R. (2021). Mapping recent development in scholarship on fake news and misinformation, 2008 to 2017: Disciplinary contribution, topics, and impact. American Behavioral Scientist, 65(2), 290–315. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0002764219869402

- Haim, M., Graefe, A., & Brosius, H.-B. (2018). Burst of the filter bubble? Effects of personalization on the diversity of Google News. Digital Journalism, 6(3), 330–343. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2017.1338145

- Hall, S. (1980). Encoding/decoding. In S. Hall, D. Hobson, A. Love, & P. Willis (Eds.), Culture, media, language (pp. 117–127). Hutchinson.

- Hern, A. (2017). Google plans to ‘de-rank’ Russia Today and Sputnik to combat misinformation. The Guardian. http://www.theguardian.com/technology/2017/nov/21/google-de-rank-russia-today-sputnik-combat-misinformation-alphabet-chief-executive-eric-schmidt

- Hussein, E., Juneja, P., & Mitra, T. (2020). Measuring misinformation in video search platforms: An audit study on YouTube. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 4(48), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1145/3392854

- Kitchin, R. (2014). Big Data, new epistemologies and paradigm shifts. Big Data & Society, 1(1), 1–12. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/2053951714528481

- Kitchin, R. (2017). Thinking critically about and researching algorithms. Information, Communication & Society, 20(1), 14–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2016.1154087

- Kravets, D., & Toepfl, F. (2021). Gauging reference and source bias over time: How Russia’s partially state-controlled search engine Yandex mediated an anti-regime protest event. Information, Communication & Society, 9, 1–17. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2021.1933563

- Madden, K., Nan, X., Briones, R., & Waks, L. (2012). Sorting through search results: A content analysis of HPV vaccine information online. Vaccine, 30(25), 3741–3746. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.10.025

- Newman, N., Fletcher, R., Schulz, A., Andı, S., & Nielsen, R. (2020). Reuters Institute Digital Reporthttps://www.digitalnewsreport.org/survey/2020/.

- Puschmann, C. (2019). Beyond the bubble: Assessing the diversity of political search results. Digital Journalism, 7(6), 824–843. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2018.1539626

- Radnitz, S. (2021). Revealing schemes: The politics of conspiracy in Russia and the Post-Soviet region. Oxford University Press.

- Relman, D. A. (2020). Opinion: To stop the next pandemic, we need to unravel the origins of COVID-19. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(47), 29246–29248. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2021133117

- Steiner, M., Magin, M., Stark, B., & Geiß, S. (2020). Seek and you shall find? A content analysis on the diversity of five search engines’ results on political queries. Information, Communication & Society. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2020.1776367

- Sunstein, C. R., & Vermeule, A. (2009). Conspiracy theories: Causes and cures*. Journal of Political Philosophy, 17(2), 202–227. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jopp.2009.17.issue-2

- Toepfl, F. (2013). Making sense of the news in a hybrid regime: How young Russians decode state TV and an oppositional blog. Journal of Communication, 63(2), 244–265.

- Urman, A., Makhortykh, M., & Ulloa, R. (2021). The matter of chance: Auditing web search results related to the 2020 U. S. Presidential primary elections across six search engines. Social Science Computer Review. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/08944393211006863

- Uscinski, J., & Enders, A. (2020). The coronavirus conspiracy boom. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2020/04/what-can-coronavirus-tell-us-about-conspiracy-theories/610894/

- Uscinski, J. E. (2019). Conspiracy theories and the people who believe them. Oxford University Press.

- Vraga, E. K., & Bode, L. (2020). Defining misinformation and understanding its bounded nature: Using expertise and evidence for describing misinformation. Political Communication, 37(1), 136–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2020.1716500

- Watanabe, K. (2018, August 22–25). Conspiracist propaganda: How Russia promotes anti-establishment sentiment online. ECPR General Conference, Hamburg, Germany. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/7a3e/be6eef4da1d31a1f73abd4aa89fc9196743f.pdf

- Weiss, A. S. (2020). With friends like these: The Kremlin’s far-right and populist connections in Italy and Austria. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. https://carnegieendowment.org/2020/02/27/with-friends-like-these-kremlin-s-far-right-and-populist-connections-in-italy-and-austria-pub-81100

- Yablokov, I. (2015). Conspiracy theories as a Russian public diplomacy tool: The case of Russia Today (RT). Politics, 35(3–4), 301–315. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9256.12097

- Yablokov, I. (2019). Conspiracy theories in Post-Soviet Russia. In J. Uscinski (Ed.), Conspiracy theories and the people who believe them (pp. 360–371). Oxford University Press.

- Yablokov, I., & Chatterje-Doody, P. N. (2021). Russia Today and conspiracy theories: People, power and politics on RT. Routledge.