ABSTRACT

The far right is notoriously effective in its use of digital media to mobilize people and to build a sense of collective identity around oppositional cultures. Yet, while research has begun to explore far-right groups’ social media hyperlinking activities, relatively little is known about the purposes and communicative functions of this form of communication. By combining social network analysis and qualitative content analysis on Facebook data obtained from 17 PEGIDA and Generation Identity Facebook pages in the period around the so-called ‘refugee crisis’ (2015–2017), this exploratory study investigates the linked source types and their purposes. We find that the groups predominantly link to mainstream media, far-right media and far-right non-institutional groups. While there are great overlaps in the communicative functions and purposes of the links for the two networks, the PEGIDA groups mainly focus on the promotion of political issues, especially around the opposition to third-country (Muslim) immigration, while the GI groups use them for self-promotional purposes. These differences are largely explainable by the groups’ adverse (online) mobilization aims.

Introduction

Fueled by 9/11, the immigration backlash in 2015, and the fears surrounding the COVID pandemic, the far right has gained much ground in Europe. Recent decades have seen the formation of transnational far-right networks, including both Neo-Nazi groups, and more ‘moderate’ actors such as the Patriotic Europeans Against the Islamization of the Occident (PEGIDA) and Generation Identity (GI). Representing a fundamental irony of the globalization of nationalism, these groups and networks are part of a global far-right ecosystem that scholars have begun to map (see e.g., Baele et al., Citation2020; Davey & Ebner, Citation2017; Froio & Ganesh, Citation2019; Haller et al., Citation2019; Heft et al., Citation2021; Holt, Citation2020). Becker (Citation2019) describes this ecosystem as an ‘international disinformation machine, devoted to the cultivation, provocation and amplification of far-right, anti-immigrant passions and political forces’ (Becker, Citation2019). Connected through digital platforms, it constitutes a mixture of political parties (Ackland & Gibson, Citation2013; Klein & Muis, Citation2019), alternative far-right news sites (Heft et al., Citation2021; Tischauser & Musgrave, Citation2020), numerous looser protest groups (Caiani et al., Citation2012; Caiani & Parenti, Citation2013), and a disparate array of individuals. Participating from the comfort and safety of their own homes, these actors can practically uninhibitedly spread blog posts and news articles, share tweets, and watch and distribute videos.

A substantial scholarship is emerging on how far-right political parties and politicians use digital platforms for both internal communication and propaganda diffusion to a broader audience (see e.g., Ackland & Gibson, Citation2013; Kalsnes, Citation2016; Larsson, Citation2017). This research emphasizes hyperlinking as a central activity for these organizations’ online activity, constituting an important means of framing social and political issues, fostering a sense of group identity, and coordinating political action. Far-right extra-parliamentary actors also use social media, but research on this topic is still relatively scarce (Klein & Muis, Citation2019; Scrivens & Amarasingam, Citation2020; Stier et al., Citation2017).

This study addresses this lacuna through an explorative analysis of the hyperlinking practices of 17 prominent Western European far-right protest groups, which were part of, or associated with, either the transnational Generation Identity (GI) or PEGIDA networks (Berntzen & Weisskircher, Citation2016; Zúquete, Citation2018). These networks are part of the anti-Islam movement and are characterized by their hybrid nature, moving between media and movement actor (Heft et al., Citation2021). The communicational and ideological differences across the two networks make them apt for comparison. More precisely, the study seeks answers to the following research questions:

Q1. What types of media sources are targeted by the hyperlinks? What is the structural relationship between the selected far-right groups, in respect of their connection to each other and their outlinks?

Q2. What are the social and communicative functions of these hyperlinks?

To our knowledge, this is the first large-scale comparative and transnational approach to far-right groups and their hyperlinking practices. While Veilleux-Lepage and Archambault (Citation2019) conducted a similar study of the transnational Soldiers of Odin Facebook network (focusing on three national groups), most existing research focus on protest groups in specific countries, like Germany and Austria (Haller & Holt, Citation2019) and Canada (Scrivens & Amarasingam, Citation2020). So far, few studies have systematically analyzed their transnational online activities across Europe. An analysis of the hyperlinking practices of these extra-parliamentary far-right groups may provide us with important insights on their online communication and mobilization strategies, enabling us to identify inter-organizational structures and cluster affinities.

Our results show that the studied groups predominantly link to mainstream media, far-right media, and far-right non-institutional groups. While the links have similar communicative functions and purposes for the two networks, the PEGIDA groups mainly focus on the promotion of political issues, especially related to third-country (Muslim) immigration, while the GI groups use them for self-promotional purposes. These differences are largely explainable by the groups’ adverse (online) mobilization ambitions.

Hyperlinking as strategic and identity-enforcing activity for the far right

Due to their low entry thresholds and user-friendliness, digital platforms provide ample communication opportunities for a multitude of actors, including those espousing radical worldviews. The platforms’ setups ‘allow outside challengers to route around social institutions that structure political discourse, such as parties and legacy media, which have previously held a monopoly on political coordination and information distribution’ (Jungherr et al., Citation2019, p. 1). Social media platforms thus provide opportunities for group leaders to both address their existing members and to disseminate their viewpoints to a larger ‘follower’ base.

Hyperlinks play a particularly important role in this context. Hyperlinking is an essential part of the web architecture for various online platforms such as Facebook and Twitter and constitutes a key structuring feature of online interaction. Users employ links as communicative acts (Heft et al., Citation2021; Park, Citation2003), and for many political groups, such links serve as a central means of internal communication and of reaching out to the broader public, making them apt for studying far-right mobilization and communication strategies. By sharing links to other websites, actors may call attention to and frame social and political issues, construct political alliances, amplify shared political positions, and coordinate collective action (see e.g., Ackland & Gibson, Citation2013; Caiani & Parenti, Citation2013; Froio & Ganesh, Citation2019).

Research shows that different actor types tend to use links for distinct purposes, implying the need of a case-based interpretation (De Maeyer, Citation2013; Klein & Muis, Citation2019). So far, most research has primarily scrutinized how formal and institutionalized far-right actors, i.e., parties and politicians, use hyperlinks. Oppositely, informal and extra-parliamentary groups have been largely overlooked, with some exceptions.

For instance, in their study of Czech and German far-right movement organizations, Fujdiak and Ocelík (Citation2019) explored the content and nationalities of the linked websites. They show that besides local Identitarian movements and PEGIDA branches, the organizations strongly concentrate on their domestic settings. Haller and Holt (Citation2019) focus on the Facebook pages of the Austrian and German PEGIDA movement. They conclude that these groups refer to mainstream and alternative media almost equally (around 40% of the links), while references to mainstream media are often affirmative in nature, deployed to ‘prove’ their own political positions. Using SNA and discourse analysis, Klein and Muis (Citation2019) compared the hyperlink activities of far-right parties and extra-parliamentary groups in Western Europe. They show that the hyperlink network structures are not clearly linked to offline far-right political opportunities. Furthermore, the Facebook pages vary between far-right actors: party-related pages are less extreme and focus more on the political elite, while movement pages focus more on immigration and Islam, although there are indications of internal differences among various extra-parliamentary groups.

Research on political parties has identified general functions of hyperlinks (Ackland & Gibson, Citation2013; De Maeyer & Holton, Citation2015; Ryfe et al., Citation2016). The main functions frequently described are force multiplication, identity building and reinforcement, and opponent dismissal and issue control (Ackland & Gibson, Citation2013). First, identity confirmation or reinforcement refers to the strategic use of hyperlinks in support of a particular political cause or issue, thereby reinforcing the party’s policy message and priorities. Second, force multiplication refers to the use of hyperlinks to reach out to likeminded organizations, to enhance shared objectives, and to create and cement political alliances. Third, opponent dismissal and issue control is the use of hyperlinks as a means of criticizing other groups, thereby creating a negative affect toward them that reinforces the party’s own identity.

Although this existing research focuses on institutionalized actors, we expect extra-parliamentary far-right groups use links for similar purposes, as both actor types share a desire to promote their political viewpoints, gather support, and build alliances (see Stier et al., Citation2017). Yet, their decentralized organizational structure and stronger focus on mobilization and identity formation also lead us to expect certain differences. Based on previous research, we formulate some expectations that guide the subsequent analysis.

First, considering that (transnational) alliance-building and networking are key strategies of far-right extra-parliamentary actors, we expect this to be a dominant hyperlink use for these groups. Such networking is used for knowledge exchange and learning (Caiani, Citation2018; Durham & Power, Citation2010), and to create ‘ideological cohesion and integration into a political community’ (Heft et al., Citation2021, p. 15), plus as a support network for otherwise marginalized actors (Macklin, Citation2013, p. 177). We thus expect that far-right protest groups use hyperlinks to promote other far-right actors including the American far right, which is becoming a prominent reference point for European far-right actors (Taschka, Citation2019).

Second, similar to Ackland and Gibson’s (Citation2013) ‘opponent dismissal’ category, we also expect (far-right) protest groups to make prevalent use of antagonist constructions to delineate their ideological borders and enforce their collective identity. This identity construction may take place through various framing activities (Snow & Benford, Citation1988), involving the blaming of antagonized ‘others’ for a given phenomenon (Benford & Hunt, Citation1992). We therefore expect the far-right groups to use hyperlinks antagonistically toward primarily left-wing and mainstream politicians, for instance by constructing them as irrational or immoral (Shibutani, Citation1970).

Third, political protests are central for extra-parliamentary groups in their attempts to exert political pressure on adversaries and decision-makers, draw attention to their cause, foster and sustain intra-group cohesion, and recruit new members (see e.g., Caiani et al., Citation2012; Simi & Futrell, Citation2009). This makes advertising for upcoming and past events highly likely to be amongst these users’ key uses of hyperlinks.

In this context, it is also worth investigating to what extent far-right groups lean on mainstream media, as opposed to (far-right) alternative media, to heighten the group’s (perceived) significance. Like far-right alternative news sites, we expect far-right groups to ‘link up to broader information environments’ (Heft et al., Citation2021, p. 16) and react to stories from established mainstream media, more so then setting their own agenda (Kaiser & Rauchfleisch, Citation2019). Hence, we expect that the groups’ hyperlinking activities will consist of the provision of information confirming or ‘proving’ the far-right actors’ own political positions to a large extent, often relying on mainstream media sources for affirmative purposes, to make more ‘legitimate’ claims (see also Fujdiak & Ocelík, Citation2019).

Finally, as a more overarching exploration, we will examine the extent to which the explored far-right extra-parliamentary groups’ social media pages function as so-called ‘echo chambers,’ in the sense that there is a lack of exposure to contrary opinions and truth claims, due to their isolated and homogeneous natures (Jamieson & Cappella, Citation2008; Sunstein, Citation2002). This is a hugely debated scholarly question, due to the expected effects of such knowledge isolation and protection from opposing views, fostering biased conceptions and political polarization. This would suggest that the groups predominantly link to each other and other like-minded actors, rather than political antagonists or critical articles in mainstream media (Barberá et al., Citation2015; Haim et al., Citation2018).

To test these expectations and to gain a deeper understanding of the social media communication and mobilization strategies of far-right extra-parliamentary groups, this study undertakes a comparative and explorative analysis of the online activities of 17 PEGIDA and GI groups on Facebook, focusing particularly on the network structure of the links and their social and communicative functions. These groups’ differences in mobilization strategies makes them ideal cases for investigating hyperlinking practices across extra-parliamentary far-right groups.

Cases: PEGIDA and generation identity

PEGIDA and GI are two of the largest and most prominent European transnational far-right extra-parliamentary networks in recent years. Like many other far-right organizations, the national PEGIDA and GI groups primarily unite around a staunch opposition to mass (Muslim) immigration and the cultural liberalization of Europe, expressed through both offline and, more vociferously, online channels. Both networks have relied heavily on social media, in particular Facebook, to present their political opinions, communicate with members, and coordinate collective action. Existing research demonstrates transnational (online) exchanges between the respective network members (Nissen, Citation2022). We therefore expect a relatively dense linking network, both to local and European PEGIDA and GI groups, but also to other (inter)national far-right organizations.

Having roots in the French groupuscule Identitarian Bloc (Bloc Identitaire), the new right-inspired youth organization Génération Identitaire (henceforth GI France) was founded in 2012. Within a few years, its organizational and ideational framework diffused to other national settings across Europe (Zúquete, Citation2018; Nissen, Citation2022). At their height, around 12 official national GI groups existed across Europe (plus two in the US and Canada). These groups had a strong Facebook presence, until the platform banned all GI groups in 2018. PEGIDA was founded in Dresden, Saxony in Autumn 2014. Initiated on a private Facebook group, by January 2015, the movement had diffused to various countries, where local, regional, and national groups voiced strong opposition to (Muslim) immigration, couched in cultural and populist terms, and predominantly mobilizing online (Berntzen & Weisskircher, Citation2016).

While we expect both the GI and PEGIDA groups to use social media for promoting events and for sharing news stories related to their core mobilizing issues, we also assume they have different online strategies. This is largely based on their different movement identities in terms of worldview, mobilization strategies, and movement identities (see Nissen, Citation2022). Wishing to be perceived as an intellectual avant-garde, the GI groups predominantly focus on influencing the societal discourse and attracting media attention to their cause, using a professional media strategy (Castelli et al., Citation2021; Zúquete, Citation2018). GI’s conscious metapolitical aim of ‘re-conquering’ societal discursive hegemony is likely to lead the GI groups to use mainstream sources to a high extent to underline their claims (see also Nissen, Citation2022). This strong focus on media dissemination differs significantly from most PEGIDA groups, which do not appear to construct and utilize their social media pages with highly strategic communicative ambitions, and instead focus on being considered as part of ‘the people.’ PEGIDA Germany is an exception here since it has been shown to moderate the content of its posts to foster user engagement (Schwemmer, Citation2021). This prompts us to assume that primarily the GI groups, but possibly also PEGIDA Germany, use hyperlinks directed to mainstream media sites.

Data and methods

The dataset comprises 17 Facebook groups associated with either the PEGIDA (11) or the GI (6) networks. Three groups from each network derive from German-speaking countries (Germany, Austria, and Switzerland), allowing for more direct cross-network comparisons. While certain PEGIDA groups (PEGIDA Germany, PEGIDA Austria, and For Freedom) and GI groups (GI Germany, GI Austria, and GI Italy) make up the most protest-active groups, others (PEGIDA Norway, PEGIDA Switzerland, and GI Switzerland) hardly organized any collective action in the studied period. The individual activists Anne Marie Waters and Tommy Robinson were selected due to their leadership of PEGIDA UK, while Robinson is also a prominent activist within the anti-Islam movement. The French Republican Resistance and the GI Netherlands are both related to, but not officially part of, either the PEGIDA or GI network, and PEGIDA Europa, Festung Europa, and Fortress Europe are all transnational pages. This wide selection of groups, protest levels, and countries enables us to make comparisons both within and across the networks.

In terms of the selected time period, we focus on the so-called ‘refugee crisis’ (2015–2017). This period saw high levels of both online and offline extra-parliamentary activities among European far-right groups, making it an opportune moment to explore how these groups communicate and relate to their surroundings. Third-country immigration and Islam were highly contentious and debated issues across Europe, opening more opportunities for voicing discontent. There are other, more practical reasons for focusing on groups coalescing in the mid-2010s, such as the fact that COVID-19 put a (momentary) end to pan-European far-right (offline) collaboration, and that Facebook significantly restricted data access in the wake of the Cambridge Analytica scandal of 2018.

We accessed the data by scraping all official posts from the groups’ Facebook pages using the Netvizz application (Rieder, Citation2013). The data was collected retrospectively, inferring that some posts may have been deleted either by the group moderators or by Facebook before the actual data collection. Yet, as it is the main ambition to understand the groups’ general use of hyperlinks, we argue that such missing posts do not interfere with our overarching findings; instead, the remaining posts depict ‘the curated self-presentation’ of the groups (Stier et al., Citation2017, p. 7). The full corpus consists of 22,699 posts from 17 groups and includes original posts and the associated meta-data, such as ‘likes’ and ‘shares’ (see ). The corpus includes all posts in the period between December 2014 and 2017.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of the selected Facebook groups.

We analyzed the data using an explorative and mixed-method approach, combining social network analysis (SNA) and qualitative content analysis. To address the first research question, we used SNA to provide a relational overview of the outbound links from the selected groups. We extracted all domain names from all posts from each group and reduced them to root-domains (N = 2,293). Both authors then manually coded the URLs into different media categories based on the websites’ self-description in terms of political orientation, together with descriptions provided by fact checkers (for a similar approach, see Heft et al., Citation2021). The coders first jointly constructed a preliminary codebook, which was further moderated in an iterative manner during the coding process. The identified link categories are: Mainstream media; Conservative media; Christian media; Pro-Israel; Russian media; Authorities; Alternative media; Far-Right media (FR media); Far-Right parties (FR parties); Far-Right non-institutional groups and actors (FR groups); Left-wing groups; Sharing platforms (see Appendix for code description). In cases where the sites were no longer accessible, we used the Way Back Machine to retrieve information. Hyperlinks that did not fit within any of these categories or that remained inaccessible were coded as Other (8.7%).

To address the second research question, we investigated how and for what purposes the hyperlinks were used. Drawing on the findings from the SNA, and acting as gold standard or master coder (Syed & Nelson, Citation2015), one author conducted a manual qualitative content analysis on posts from ten groups (five PEGIDA groups and five GI groups), selected due to their belonging to different network clusters. The analysis focused on the links to the three largest media categories in the material, namely Mainstream media, FR media, and FR groups (1,439 posts). The coder coded all links to the two former categories, except for groups with more than 200 links. For these cases, 100 links were randomly selected, as we deemed this sufficient to saturate the data for the two hyperlink types. For the FR groups, we coded all links that were accessible, since only GI France and GI Germany linked to more than 100 of such pages. presents an overview of the coded posts.

Table 2. Overview of ten PEGIDA and GI groups and the number of coded posts for each of these groups (n = 1439).

Inspired by grounded theory (Glaser & Strauss, Citation1967), we identified 13 main codes by focusing on the issue content of the Facebook posts and hyperlinks. These codes were then sorted into four broader categories. The unit of analysis for the coding was the post wording, supported by the actual contents of the posted hyperlink (e.g., if a hyperlink was to a news story about Islamist terrorism it was coded as ‘Demonstrating the dangers of Islam and third-country immigration’). Posts that solely consisted of a hyperlink were coded according to the core message of the material provided on the given webpage. A post could also be coded into two categories. For instance, when a post included a hyperlink to an article containing statistics on immigrant numbers in a given country, and the post encouraged people to join an upcoming protest in response, this post was coded as both ‘Demonstrating the dangers of Islam and third-country immigration’ and ‘Self-promotion.’

The analysis was systematically evaluated by a second coder (using the approach by Riffe and colleagues (Citation1998)), with an intercoder reliability coefficient of 59%. While this can be criticized for being relatively low, we nonetheless consider it sufficient for the grounded theoretical approach, also considering that the posts could be double-coded.

Participants’ integrity and privacy are always important to consider when working with digital data, especially since the considerable size of these groups often makes it very difficult or even impossible to collect individual consent. In this study, several measures were undertaken to ensure participants’ integrity and privacy. Foremost, we only included public Facebook pages in the dataset since these are openly accessible and specifically signed for the purposes of reaching out. In addition, we only included the original posts and an aggregation of the reactions from the followers. Individual user comments were not included in the dataset. Finally, the data has been anonymized, and we present the findings in such a way that no individual users can be identified.

Findings

The network structure of the PEGIDA and GI groups

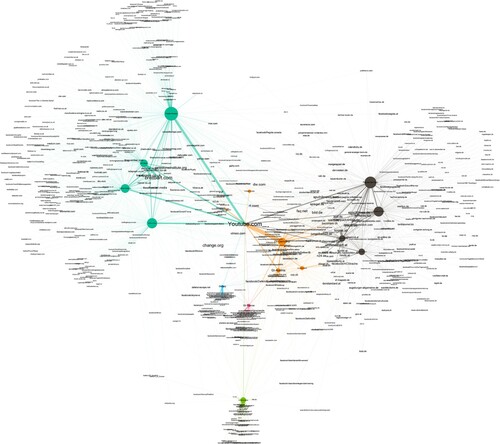

The full network consists of 2,293 nodes and 3,252 edges, with an average degree of 1,418. The network density is very low (0.001), since many sites are linked only once. To create a more manageable network, we selected all nodes with a weighted degree of two or higher, entailing that we only include sites linked at least twice. This produces a smaller and denser network consisting of 845 nodes and 1,807 edges (see ). The network provides an overview of the selected groups, and the sites that are most frequently linked. In the figure, node size is based on outdegree; the label size on indegree.

By using Louvain community detection analysis (Blondel et al., Citation2008), we detected six network clusters (illustrated with different colors in ). The groups cluster primarily around network belonging, but, as other similar studies also indicate (Urman & Katz, Citation2022), language also plays a role. PEGIDA Norway, Anne Marie Waters, Tommy Robinson, and Fortress Europe together form the largest cluster in the network, comprising 44% of the nodes, and they are relatively separate from the rest of the network. Most posts by these groups, including those of PEGIDA Norway, are in English. The second cluster, comprising 26% of the nodes, consists of German-speaking PEGIDA groups (PEGIDA Germany, PEGIDA Europa, PEGIDA Austria, and PEGIDA Switzerland), while the third cluster consists of German-speaking GI groups: GI Germany, GI Austria, GI Switzerland, plus Festung Europa, which is part of the PEGIDA network (13%). These two clusters are well-connected with each other and share many links, most likely due to their shared language. In addition, there are some minor, relatively isolated, clusters: GI Italy (3.5%), GI France (4.9%), and particularly GI Netherlands (8%).

In terms of the nationalities of the linked sites, most sites are from Germany (27%), followed by the US (12%), the UK (11%), and the Netherlands (7%). This confirms our expectation that the European groups draw substantially on American online content (see also Heft et al., Citation2021).

Centrality measures

Looking at node centrality, YouTube is the most central node in the network, serving as a type of gatekeeper connecting all groups (see ). Previous studies also point to the important role of YouTube for far-right agitation (Rone, Citation2021; Schwemmer, Citation2021). Other highly influential sites include the far-right news site Breitbart, the radical-right and anti-Islam think tank Gatestone Institute, and the online petition website Change.org. Among Mainstream media, the most linked sites include the British Express, Daily Mail, and The Guardian, and the German-language Kronen Zeitung, Deutsche Welle, and Der Standard. Notably, two Russian state-owned news sites, RT (previously Russia Today) and Sputnik News, belong to the most central nodes in the network. These results are consistent when using other centrality measures, such as Eigenvector and PageRank.

Table 3. Centrality measures for the most central nodes in the network.

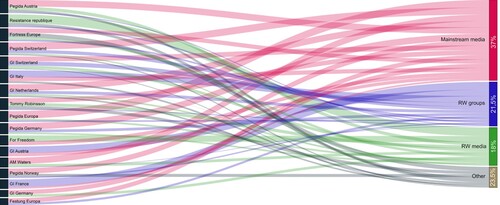

Media categories and user engagement

In alignment with previous studies (Haller & Holt, Citation2019; Heft et al., Citation2021), we also find that Mainstream media (37%) is by far the most frequently linked media category, followed by FR groups (21.5%), and FR media (18%). Other categories receive few links (Alternative media (2.6%), Sharing platforms (1.7%), Russian media (1%), oppositional LW groups (0.5%), and Authorities (0.5%)). Moreover, links to FR parties only make up 3% of the dataset, indicating a limited far-right networking endeavor with more institutionalized actors. However, the Sankey diagram () shows significant differences between the groups. Whereas the PEGIDA groups link to Mainstream media to a high extent (around 50% of their outlinks), the GI groups instead mainly link to various FR groups, predominantly from within their own network, thereby enforcing their (trans)national collective identity (see also Nissen, Citation2022). This is particularly the case for GI France (60% of its outlinks are to local French GI groups). Conversely, GI Netherlands is an exception, as only 23% of its links go to FR groups, potentially explained by its non-inclusion in the official GI network. Only Republican Resistance (67%) and For Freedom (48%) link to a very high extent to FR media. The other media categories are more evenly distributed among the groups. It is noticeable that the large proportion of links to FR media and FR groups seem to differ from previous studies.

Figure 2. Sankey diagram of the Facebook groups and their relations to the three largest media categories.

Mainstream media, FR media, and FR groups also evoke most audience engagement in absolute terms (the total amount of comments, likes, and shares). FR groups receive around 47% of the total number of likes, while links to Mainstream media spark most comments and discussions (40%) and shares (46%). In relative terms (i.e., by dividing each reaction type by the total number of reactions for each media category), we find that FR parties, FR groups, and Sharing platforms tend to receive the largest proportion of likes, while Pro-Israeli sites, Mainstream media, and Alternative media tend to produce a high proportion of shares.Footnote1 YouTube.com, the two German FR media sites Jungefreiheit.de and Epochtimes.de, and the American FR media page Breitbart.com are the sites that spark most overall engagement.

In the next analytical step, we address the second research question by more closely examining how these hyperlinks are used and for what purposes. We focus the analysis on the links to the three largest hyperlinks groups, namely Mainstream media, FR groups, and FR media.

Hyperlinking strategies and functions

The in-depth analysis of the posts containing links to the three largest media categories revealed 13 codes, which can be organized into four broad categories or themes (see ). We describe these codes in detail below.

Table 4. Share of codes for the two networks (PEGIDA = 775; GI = 1092).

Promotion of political issues

Demonstrating or elaborating the ‘dangers’ of Islam and third-country immigration, exemplified through events that provide ‘clear signs’ of the West’s decay. This is typically illustrated as [i] an existential/demographic threat (such as ‘Great Replacement’ worries, high numbers of entering migrants, the introduction of Muslim practices) or [ii] a security threat (e.g., attacks by Islamist terrorists, violence perpetrated by migrants). The posts are only coded to this category if there are explicit references to Muslim and/or migrant perpetrators. The category also includes posts discussing threatening actions of Muslims in third countries, including e.g., references to the violent nature of ISIS in the Middle East or Palestinians in Israel, or to the Turkish President Erdogan’s speeches about the role of Muslims in Europe.

Praising mainstream politicians and media for their anti-migrant actions and statements, often by praising the group’s own role in ‘converting’ these actors and helping them to ‘see the light,’ and for instance begin questioning the strong domestic or European intake of third-country migrants.

(International conflicts and issues. This code comprises posts relating to various international political issues, such as Turkish domestic affairs, conflicts in the Middle East, and the EU, but also various non-political issues. As most links lack a clear political argument accompanying them, except for EU criticism, which is only mentioned in around five of the 1,439 posts, the code is placed in brackets in this category).

Opponent dismissal

Criticizing liberal and LW actors for their positive views on, and actions toward, third-country migrants and Islam. This is expressed by exposing LW actors, especially proponents of a liberal immigration policy (including LW NGOs and politicians), and also through sarcastic remarks about Muslim immigrants as ‘cultural enrichments.’

Criticizing or ridiculing LW (counter-)protesters, including both more peaceful counter-protests and violent attacks against far-right groups. The code also involves complaints about the longer ‘leash’ provided to LW actors regarding their more controversial actions, and mocking statements about LW actors, who have criticized or called for repercussions in response to the groups’ actions.

Criticizing mainstream politicians, often for actions and statements during the so-called ‘refugee crisis.’ Here, ‘Mainstream’ refers to centrist parties, like social democratic, liberal, or conservative parties, or to the ‘political elite’ or ‘political leadership,’ if no explicit parties are mentioned. Such criticism is most frequently voiced against the German Chancellor, Angela Merkel. The GI groups, for instance, accuse their leaders of solely taking in migrants for economic reasons and thereby exploiting them.

Criticizing media framing and censorship, for instance when mainstream media censors the name and ethnicity of a perpetrator or refers to the given far-right group or actor as ‘extremist’ or ‘fascist.’

Self-victimization includes perceived repression against the network, including (pending) court cases against network members, ‘solidarity protests’ for network members, and attacks on network members or other far-right representatives by LW activists. Many of these posts include calls for harsher punishments against this form of violence.

Collective action promotion and organization

Strategic deliberations about far-right mobilization, political events, and ideology. Planning and coordinating political action, evaluating tactics, and discussions on how to position themselves as part of the far-right, conservative movement.

Self-promotion includes advertisements for the groups’ own and fellow network members’ upcoming protests, and reports about their past actions and events, together with links to media interviews and blog posts written by members of the given group.

Far-right political networking

Political networking and ideology cohesion includes reaching out to like-minded far-right groups, discussing the election results of far-right parties, highlighting of nationalist statements, actions, or events, plus more general comments about the advancement of the European far right.

Promotion of far-right ‘alternative media,’ including alt-right media platforms, often accompanied by criticism of mainstream media.

Other

Other includes posts about a diverse range of issues that are only mentioned once or twice in the dataset, including welfare distribution and Swiss direct democracy. It also includes news events related to the ‘refugee crisis,’ but without the actors expressing any sentiments (praise/criticism etc.) regarding these issues.

In alignment with the expectations, a substantial share of both networks’ hyperlinks relates to the groups’ political cause and worldview. Particularly the PEGIDA groups strive to achieve consensus around, and control the issue of, (Muslim) immigration (39.7% of the codes) (see also Schwemmer, Citation2021 on PEGIDA Germany). Looking at the individual groups, the less protest-active groups employ hyperlinks for this purpose to a higher extent (i.e., GI Switzerland, Anne Marie Waters, PEGIDA Austria, and PEGIDA Norway, see Appendix Tables A1 and A2). Conversely, For Freedom hardly uses hyperlinks for worldview diffusion purposes (only 7% of the codes). Moreover, as the sole group, PEGIDA Norway frequently links to fake news or conspiracy theories (e.g., pointing to the Illuminati’s use of Islam to conquer the world), placing it as an outlier from the more general PEGIDA network in terms of political content diffusion.

Both networks mainly employ links to Mainstream media to illustrate the threats related to third-country (Muslim) immigration, especially regarding security issues (particularly crime levels and terrorist attacks), but also to highlight integration challenges and cultural differences (see also Ekman, Citation2018; Froio & Ganesh, Citation2019; Haller & Holt, Citation2019). In fact, around 20% of the groups’ mainstream media posts belong to this code, indicating a legitimacy and confirmation pursuit, as anticipated. Similar to the findings of Haller and Holt (Citation2019), several of these posts involve ‘I told you so!’ statements, where the groups use the media account as an affirmative means ‘to prove [their] own political positions’ (ibid: 1671). Aligning with Generation Identity’s attention-seeking communication strategy, the GI groups (mainly GI Austria) often combine the ‘Promotion of political issues’ with ‘Self-promotion,’ by linking to news articles about their anti-immigration and/or anti-Islam protest actions, while simultaneously emphasizing the immigration threats in the Facebook post itself, thereby also attempting to influence the societal discourse. By contrast, many of the PEGIDA groups’ posts expressing hostility to third-country (Muslim) immigration are instead phrased without any forms of value judgment or calls for action. Instead, they read as news story announcements, solely describing the article contents (see also Haller & Holt, Citation2019).

Interestingly, around 45% of the links in this category are to foreign news stories, illustrating a strong reliance on transnational news circulation. While the groups also make numerous references to international events (6.4%), Germany and Sweden are most frequently used as illustrative examples of the risks associated with overly lenient immigration policies (17% of all posts in this category). These findings indicate that the GI and PEGIDA groups identify both inter- and national news stories that confirm and lend credibility to their migrant-hostile stances, thereby vastly enlarging the pool of negative news stories, and thus augmenting the threat perception.

also shows that both networks often use links involving ‘Opponent dismissal’ (around ⅓ of the posts, predominantly from mainstream and FR media sources). Particularly the German-speaking groups (except GI Austria) and Anne Marie Waters use this strategy. This often involves criticism of mainstream and LW actors, either by using the mainstream media sources as background information for their own criticism in the post, or by posting a link to a FR media page containing this message. Several of these posts are very context-specific. As examples, GI Italy deplores Italian trade unions’ stance on a proposed Italian ius soli legislation, while For Freedom is the only group frequently criticizing violent LW counter-protesters (see also Nissen, Citation2022).

Somewhat surprisingly, the GI groups use substantially more hyperlinks to report about their own and their network members’ activities compared to the PEGIDA groups (38.4% vs. 11.4% respectively). This self-promotion strategy (which is particularly prevalent for GI France (59.5%) and GI Italy (49.3%)) again relates back to the GI groups’ media-attention quest, often sought through protest actions (see Nissen, Citation2022). These links both involve mainstream and FR media articles about GI protests or interviews with GI representatives, while especially GI Germany and GI Austria also link to RW media blog posts written by GI representatives. Interestingly, the majority of the GI links refer to actions posted by the groups’ European GI network partners (75% of the links), implying a combination of both explicit mobilizing and networking functions.

By contrast, the PEGIDA groups’ remarkably infrequent collective action announcements and accounts is mainly explainable by their comparably lower level of offline activities. Most of the (more limited) PEGIDA ‘Self-promotion’ posts are posted by For Freedom (43.8% of the PEGIDA total). Moreover, very few PEGIDA group posts relate to interviews of, or texts written by, network representatives, while only PEGIDA Germany frequently links to other (mainly domestic) PEGIDA groups’ actions (57% of its links in this category). Noticeably, hardly any of the groups voice their ‘Strategic deliberations.’ In fact, only GI Germany, GI Switzerland, and GI Italy pursue this strategy at all. GI Germany, for instance, links to German FR blogs, such as Sezession, where German GI members have formulated blog posts about how to achieve movement success.

Finally, despite expecting that ‘Far-right political networking’ would be an important hyperlinking function, this is in fact not the case in our material. Solely GI Austria occasionally explicitly encourages its followers to read ‘alternative’ RW media sites, and only a small share of both networks’ hyperlinks relate to the promotion of activities or websites of other far-right actors. Unsurprisingly, the vast majority of links in this category are to FR media or FR groups (84.2% of total) and typically relate to the celebration, and/or promotion, of a specific far-right organization, ideological inspiration, and reports about far-right demonstrations. The diversity of these hyperlink usages indicates political alliance-building attempts and ideological overlaps, but also an instrumentalization of other far-right actors as a means to back up the groups’ own claims.

Conclusion

Considering the political advancement of the far right in recent decades, this study addressed the enhanced and still under-explored need to understand how far-right protest groups communicate with their social media audiences. For this purpose, we contributed an explorative analysis of the hyperlinking practices of 17 European GI and PEGIDA Facebook pages.

The first research question addressed the types of media sources that were targeted by the groups’ hyperlinks, and the structural relationship between the selected far-right groups in terms of hyperlink usage. The network analysis revealed six distinct clusters, largely based on linguistic and ideological alignments (cf. Urman & Katz, Citation2022). In terms of the networks’ transnational scope, domestic links still dominate within the dataset (see also Heft et al., Citation2021), although the groups also link to, and inform about, international sites and events (c.f. Fujdiak & Ocelík, Citation2019). Fortress Europe and PEGIDA Norway in particular have a more pronounced transnational approach, often linking to English and American sites. Many of the groups frequently linked to US sources, particularly Breitbart, underlining the strong influence of the US far right on European actors (see also Davey & Ebner, Citation2017). Such hyperlink uses further indicate the ongoing far-right transnationalization (see also Nissen, Citation2022). Future studies should explore this transnational spread of news content and how it is used to further the far-right groups’ messages to their domestic audiences, as a means to better understand the media’s role in far-right mainstreaming.

The absolute majority of hyperlinks in the material was to Mainstream media, FR media, and FR extra-parliamentary groups, covering over 80% of all links. So, despite the groups’ hostility toward mainstream media’s far-right representations, the groups heavily rely on Mainstream media in their Facebook communication (see also Haller & Holt, Citation2019; Heft et al., Citation2021). However, unlike previous findings, the studied groups’ frequent linking to FR media pages and FR groups indicates that the construction of ideational networks is also a dominant endeavor for at least some far-right extra-parliamentary groups. However, only 3% of hyperlinks were to FR parties, a rather surprising finding considering the offline connections and ideological overlaps between groups such as PEGIDA Germany to Alternative for Germany and GI France to National Rally.

Regarding the second research question, the qualitative content analysis shed further light on the social and communicative functions of the links to the three largest media sources. First, we may note that, in line with previous research (Fujdiak & Ocelík, Citation2019; Haller & Holt, Citation2019), links to Mainstream media mainly serve the purpose of lending legitimacy and confirmation pursuit; more specifically, to illustrate, for instance, the threats of third-country immigration or the wrong stances of the political mainstream and/or left-wing. Many of these links go to international Mainstream news sources, further signaling an increasing far-right transnationalization.

In addition, the findings presented here show clear and somewhat unexpected differences in the networks’ communicative strategies. The GI groups use hyperlinks mainly as a tactical communication strategy, for instance, reporting about their network members’ activities, interviews with leaders, coordinating action, and advertising events. The hyperlinks thus fulfill a combination of mobilizing and networking functions. For the PEGIDA groups, on the other hand, the hyperlinks contain much lower levels of collective action announcements, and instead are employed to convey a political message, by promoting political issues, particularly the threat perception of Islam and immigration. These findings run counter to our expectation that the GI groups’ focus on influencing the societal discourse by attracting media attention would lead them to use mainstream sources to a greater extent, while the PEGIDA groups would advertise upcoming events.

Overall, there are few links by the groups to extreme right content, and while many links contain criticisms of the mainstream media’s portrayal of the groups, the ‘echo chamber’ effect is not immediately evident. This is due to the extensive use of mainstream media sources, most of which are in fact employed to corroborate or support the groups’ statements, or to illustrate perceived hypocrisy or contradictions on the part of their political opponents. In this sense, rather than being insulated, closed-off enclaves or ‘echo chambers,’ where certain opinions and ideas are reinforced without competing ideas, these groups’ activities can more adequately be described as a type of trench warfare, in that they often include both confirming and contradicting arguments (Karlsen et al., Citation2017). In order to further investigate this assertion, future research should analyze the audience responses to such posts, with a specific focus on any (potential) differences in the reactions to various media categories.

Considering the imposed restrictions on Facebook and Twitter use for many far-right organizations, future research should explore the hyperlink uses of far-right extra-parliamentary groups on newer digital platforms, such as Gab and Telegram, as research shows that many far-right actors have migrated there (Urman & Katz, Citation2022). This research avenue is particularly important due to the lower levels of transparency and censoring of such pages, inferring a likely more radical form of communication by far-right activists.

Supplement Material.docx

Download MS Word (34.4 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 We only include likes, comments, and shares, since the category ‘reactions’ is an aggregation of likes and other emojis, and engagement adds together comments, reactions, and shares.

References

- Ackland, R., & Gibson, R. (2013). Hyperlinks and networked communication: A comparative study of political parties online. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 16(3), 231–244. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2013.774179

- Baele, S. J., Brace, L., & Coan, T. G. (2020). Uncovering the far-right online ecosystem: An analytical framework and research agenda. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2020.1862895

- Barberá, P., Jost, J. T., Nagler, J., Tucker, J. A., & Bonneau, R. (2015). Tweeting from left to right: Is online political communication more than an echo chamber? Psychological Science, 26(10), 1531–1542. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797615594620

- Becker, J. (2019). The global machine behind the rise of far-right nationalism. The New York Times.

- Benford, R. D., & Hunt, S. A. (1992). Dramaturgy and social movements: The social construction and communication of power. Sociological Inquiry, 62(1), 36–55. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-682X.1992.tb00182.x

- Berntzen, L. E., & Weisskircher, M. (2016). Anti-Islamic PEGIDA beyond Germany: Explaining differences in mobilisation. Journal of Intercultural Studies, 37(6), 556–573. https://doi.org/10.1080/07256868.2016.1235021

- Blondel, V., Guillaume, J.-L., Lambiotte, R., & Lefebvre, E. (2008). Fast unfolding of communities in large networks. Journal of Statistical Mechanics: Theory and Experiment, 10(P10008).

- Caiani, M. (2018). Radical right cross-national links and international cooperation. In J. Rydgren (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of the radical right (pp. 394–411). Oxford University Press.

- Caiani, M., Della Porta, D., & Wagemann, C. (2012). Mobilizing on the extreme right: Germany, Italy, and the United States. Oxford University Press.

- Caiani, M., & Parenti, L. (2013). European and American extreme right groups and the Internet. Ashgate Publishing.

- Castelli, P., Froio, C., & Pirro, A. (2021). Far-right protest mobilisation in Europe: Grievances, opportunities and resources. European Journal of Political Research. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12484

- Davey, J., & Ebner, J. (2017). The fringe insurgency. Connectivity, convergence and mainstreaming of the extreme right. Institute for Strategic Dialogue.

- De Maeyer, J. (2013). Towards a hyperlinked society: A critical review of link studies. New Media & Society, 15(5), 737–751. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444812462851

- De Maeyer, J., & Holton, A. E. (2015). Why linking matters: A metajournalistic discourse analysis. Journalism, 17(6), 776–794. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884915579330

- Durham, M., & Power, M. (2010). Transnational conservatism: The new right, neoconservatism, and cold War anti-communism. In M. Durham & M. Power (Eds.), New perspectives on the transnational right (pp. , pp. 133–148). New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ekman, M. (2018). Anti-refugee mobilization in social media: The case of soldiers of Odin. Social Media+ Society, 4(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305118764431

- Froio, C., & Ganesh, B. (2019). The transnationalisation of far right discourse on Twitter: Issues and actors that cross borders in Western European democracies. European Societies, 21(4), 513–539. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616696.2018.1494295

- Fujdiak, I., & Ocelík, P. (2019). Hyperlink networks as a means of mobilization used by far-right movements. Central European Journal of Communication, 12(2), 134–149. https://doi.org/10.19195/1899-5101.12.2

- Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). Discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Aldine Transaction.

- Haim, M., Graefe, A., & Brosius, H.-B. (2018). Burst of the filter bubble? Effects of personalization on the diversity of Google News. Digital Journalism, 6(3), 330–343. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2017.1338145

- Haller, A., & Holt, K. (2019). Paradoxical populism: How PEGIDA relates to mainstream and alternative media. Information, Communication & Society, 22(12), 1665–1680. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2018.1449882

- Haller, A., Holt, K., & de La Brosse, R. (2019). The ‘other’ alternatives: Political right-wing alternative media. Journal of Alternative & Community Media, 4(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1386/joacm_00039_2

- Heft, A., Knüpfer, C., Reinhardt, S., & Mayerhöffer, E. (2021). Toward a transnational information ecology on the right? Hyperlink networking among right-wing digital news sites in Europe and the United States. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 26(2), 484–504. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161220963670

- Holt, K. (2020). Populism and alternative media. In B. Krämer & C. Holtz-Bacha (Eds.), Perspectives on populism and the media: Avenues for research (pp. 201–214). Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft.

- Jamieson, K. H., & Cappella, J. N. (2008). Echo chamber: Rush Limbaugh and the conservative media establishment. Oxford University Press.

- Jungherr, A., & Jürgens, P. (2013). Through a glass, darkly: Tactical support and symbolic association in twitter messages. Social Science Computer Review, 32(1), 74–89. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439313500022

- Jungherr, A., Schroeder, R., & Stier, S. (2019). Digital media and the surge of political outsiders: Explaining the success of political challengers in the United States, Germany, and China. Social Media + Society, 5(3). https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305119875439

- Kaiser, J., & Rauchfleisch, A. (2019). Integrating concepts of counterpublics into generalised public sphere frameworks: Contemporary transformations in radical forms. Javnost - The Public, 26(3), 241–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/13183222.2018.1558676

- Kalsnes, B. (2016). The social media paradox explained: Comparing political parties’ Facebook strategy versus practice. Social Media+ Society, 2(2), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305116644616

- Karlsen, R., Steen-Johnsen, K., Wollebæk, D., & Enjolras, B. (2017). Echo chamber and trench warfare dynamics in online debates. European Journal of Communication, 32(3), 257–273. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323117695734

- Klein, O., & Muis, J. (2019). Online discontent: Comparing Western European far-right groups on Facebook. European Societies, 21(4), 540–562. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616696.2018.1494293

- Larsson, A. O. (2017). Going viral? Comparing parties on social media during the 2014 Swedish election. Convergence: The International Journal of Research Into New Media Technologies, 23(2), 117–131. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856515577891

- Macklin, G. (2013). Transnational networking on the far right: The case of Britain and Germany. West European Politics, 36(1), 176–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2013.742756

- Nissen, A. (2022). Europeanisation of the contemporary far right. Routledge.

- Park, H. W. (2003). Hyperlink network analysis: A new method for the study of social structure on the web. Connections, 25(1), 49–61.

- Rieder, B. (2013, May 2–4). Studying Facebook via data extraction: the Netvizz application. Proceedings of the 5th annual ACM, Paris.

- Riffe, D. L., Watson, B., & Fico, F. (1998). Analyzing media messages: Using quantitative content analysis in research. Routledge.

- Rone, J. (2021). Far right alternative news media as ‘indignation mobilization mechanisms’: How the far right opposed the global compact for migration. Information, Communication & Society, 12(2), 1333–1350. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2020.1864001

- Ryfe, D., Mensing, D., & Kelley, R. (2016). What is the meaning of a news link? Digital Journalism, 4(1), 41–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2015.1093269

- Schwemmer, C. (2021). The limited influence of right-wing movements on social media user engagement. Social Media + Society, 7(3), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051211041650

- Scrivens, R., & Amarasingam, A. (2020). Haters gonna “like”: exploring Canadian far-right extremism on Facebook. In M. Littler, & B. Lee (Eds.), Digital extremisms: Readings in violence, radicalisation and extremism in the online space (pp. 63–89). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Shibutani, T. (1970). On the personification of adversaries. In T. Shibutani (Ed.), Human nature and collective behavior: Papers in honor of Herbert Blumer (pp. 111–122). Prentice-Hall.

- Simi, P., & Futrell, R. (2009). Negotiating white power activist stigma. Social Problems, 56(1), 89–110. https://doi.org/10.1525/sp.2009.56.1.89

- Snow, D. A., & Benford, R. D. (1988). Ideology, frame resonance, and participant mobilization. International Social Movement Research, 1(1), 197–217.

- Stier, S., Posch, L., Bleier, A., & Strohmaier, M. (2017). When populists become popular: Comparing Facebook use by the right-wing movement pegida and German political parties. Information, Communication & Society, 20(9), 1365–1388. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2017.1328519

- Sunstein, C. R. (2002). Republic. com. Princeton University Press.

- Syed, M., & Nelson, S. C. (2015). Guidelines for establishing reliability when coding narrative data. Emerging Adulthood, 3(6), 375–387. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167696815587648

- Taschka, S. (2019). Trump’s America shines bright for Europe’s radical new right. The Conversation.

- Tischauser, J., & Musgrave, K. (2020). Far-right media as imitated counterpublicity: A discourse analysis on racial meaning and identity on Vdare.com. Howard Journal of Communications, 31(3), 282–296. https://doi.org/10.1080/10646175.2019.1702124

- Urman, A., & Katz, S. (2022). What they do in the shadows: Examining the far-right networks on telegram. Information, Communication & Society, 25(7), 904–923. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2020.1803946

- Veilleux-Lepage, Y., & Archambault, E. (2019). Mapping transnational extremist networks An exploratory study of the soldiers of Odin’s Facebook network, using integrated social network analysis. Perspectives on Terrorism, 13(2), 21–38. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26626863

- Zúquete, J. P. (2018). The identitarians: The movement against globalism and Islam in Europe. University of Notre Dame Press.