ABSTRACT

The 2019 European Parliament elections seemingly fostered concerted political action among radical right parties (RRPs) to fortify their positions and mobilize publics on a pan-European scale. Digital platforms provide central infrastructure for networks among political actors and user interactions on the ground. Our study, therefore, investigates the intra- and transnational networking on Twitter established by RRPs’ strategic communication and user interactions. To understand how distinct political and media-related opportunity structures align with different intensities, types, and meanings of digital connections, we investigate the salience, actor types, and geographical scopes as well as the functions of digital connections within and across Twitter networks in Austria, France, Germany, Italy, Poland, and Sweden during the EP election campaigns. Our results indicate the influence of parties’ structural power position on networked communication: The ecologies around RRPs in government reflect their integration in national discourses and competition. The networks of RRPs in opposition display a self-referential campaign ecology for the promotion and distribution of candidates, content, and positions. Transnationality in these networks is structured by EU-level collaboration and driven by civil society and political entrepreneurs, who appear keener to mobilize across borders.

1. Introduction

Many European countries have witnessed the strengthening of radical right parties (RRPs) and movements in recent years (Caiani & Císař, Citation2019), with governments fully headed (e.g., Poland) or being supported (e.g., Italy) by right-wing populists (Mudde, Citation2019). Against this background, the 2019 European Parliament (EP) elections provided an opportunity for concerted political action among radical right actors to politicize EU integration, amplify right-wing positions, and mobilize publics on a pan-European scale. In fact, during these elections, RRPs gained considerable voter support. At the party level, this rise was accompanied by a shift toward pan-European coordinated political campaigning events and transnational institution building (Lefkofridi & Katsanidou, Citation2018). Matteo Salvini and Marine Le Pen were arguably the most active politicians orchestrating prominent events that included RRP leaders and entailed movements across the continent.

For political parties, movements, and citizens, social media provide ideal infrastructures for broad repertoires of political action functional for mobilization during elections, such as the dissemination of information, direct communication and interaction with members or supporters, and calls for political activism (Jungherr, Citation2016b; Theocharis, Citation2015). In particular, digital platforms enable networks that connect and feed into a broader political communication ecology that links institutionalized right-wing politics to the electorate. Party actors and individual users at the grassroots level can access each other within the digital infrastructure for networked participation (Theocharis, Citation2015). Moreover, digital networks are not tied to national environments but rather enable communication and coalition building on a transnational scale. As an opportunity structure, they allow RRPs and users to build political linkages at the European level, thereby enhancing political institution-building on the right. However, contrary to the expectation that social media drive Europeanized communication, studies on far-right discourses (Froio & Ganesh, Citation2019) and election candidates’ linking behavior on Twitter (Stier et al., Citation2021) suggest that these actors are primarily engaged in the national political arena focusing on domestic organizations and events. Even though transnational connections may be weak, cross-border communication on social media can establish political ties between otherwise closed communities.

Hence, our study aims to understand better the patterns of digital connections between RRPs and other actors online and evaluate how distinct political and media-related opportunity structures align with different types and meanings of connections within and across European countries. These issues gain relevance from a normative point of view, as the (transnational) networking structures of RRPs in Europe may foster populist and Eurosceptic positions and eventually become a threat to European democratic procedures and institutions. Conceptually, we consider social media networks to be digital political communication ecologies (Häussler, Citation2021). We differentiate between ‘macro’ and ‘micro’ ecologies utilized for political mobilization within national and European publics. Our research questions are as follows: (1) What communication infrastructures have RRPs and their interaction partners established in the context of the EP election campaigns? Which actors are part of this communication ecology, and what are the functions of their connections? How do political and media-related opportunity structures account for variations across countries? (2) Which actors drive transnationality in this communication ecology and provide bridges across national activists, movements, and parties?

This paper covers RRPs of six European countries: Austria, France, Germany, Italy, Poland, and Sweden. They vary in terms of their structural power positions in government or opposition and acceptance in their countries, their ideological stances and offline organizational ties, and in their digital campaigning environment. We consider hyperlinking and other forms of web-based connections on Twitter to represent strategic political action using digital tools to organize, mobilize, and build national and transnational coalitions (Young & Leonardi, Citation2012). In the analysis, we focus on the political and media-related opportunity structures that may explain the intensities, types, and functions of connections within and across different European countries. Our study is based on an analysis of Twitter networks of RRPs and interacting users in the EP election campaigns in May 2019, providing a snapshot of the emerging political communication ecologies.

In the next section, we introduce the idea of macro and micro digital communication ecologies and discuss research on RRPs’ strategic use of social media and user interactions. Drawing on the concepts of political and media-related opportunity structures, we derive expectations of actors’ interaction patterns that guide our empirical investigation. Our findings demonstrate that RRPs’ digital political communication ecologies are driven by parties’ structural power position. Transnationality is shaped by EU-level collaboration and strengthened by political entrepreneurs who appear keener to mobilize across borders.

2. Radical right parties’ digital networks

2.1. Macro and micro ecologies of networked communication

The networks emerging from digital connections as part of actors’ strategic choices and interactions have been conceptualized as digital political communication ecology (Häussler, Citation2021). Using this conceptual lens helps us integrate top-down political action with user interactions while taking a macro view on discourse structures emerging from complex communication environments. These are characterized by fluidity and a diversity of actors who can constantly switch between sender and receiver and who are connecting to and interacting with each other on multiple levels in diverse roles (Friedland et al., Citation2022). Digital political communication ecologies are emergent phenomena that serve as infrastructure for many types of ‘networked communication’ (Benkler et al., Citation2015, p. 596), such as disseminating political content, engaging in direct communication, forming coalitions, or mobilizing supporters for political action. To discern the shape and structure of networked communication that evolved around RRPs during the EP election campaigns, we conceptually distinguish two layers that emerge from different roles of RRPs in digital connections, which we term ‘macro’ and ‘micro’ ecologies. Macro ecology refers to the communication structures established through the sum of parties’ own communicative actions in the form of top-down digital connections. Micro ecology alludes to the entirety of digital connections established by individual users and other organizations on the ground with the parties scrutinized.

The functions of connections forming the macro ecology can be manifold, such as distributing information on parties’ campaigns and candidates or fostering the visibility of their issues and positions (Jungherr, Citation2016b). Likewise, with digital connections, RRPs can directly reach out to like-minded organizations and citizens, acknowledge and establish political alliances, mobilize for action, or attack political opponents (Ackland & Gibson, Citation2013; Bracciale & Martella, Citation2017; Graham et al., Citation2013, Citation2016), thus bypassing traditional media mediation. Social media platforms have become important tools in parties’ repertoires of political communication in this respect, especially for those in opposition (Jungherr, Citation2016b), at the political fringes (Larsson & Kalsnes, Citation2014), or new ones (Dolezal, Citation2015). In the literature, Twitter, a micro-blogging service, is consistently described as a prominent tool for politicians to target opinion leaders and journalists and get their quotes in the media (Jungherr, Citation2016a; Larsson, Citation2015; Oelsner & Heimrich, Citation2015). Especially for RRPs that are partly shunned by traditional media and for small or new parties, the platform allows circumventing gatekeeping barriers of legacy media and establishing contact with potential supporters (Dolezal, Citation2015; Larsson & Kalsnes, Citation2014). Through the short text messages (Tweets) posted on the service, users can establish various digital connections with others within and beyond the platform. These include hyperlinks to other actors and their content on the Web as well as interactions between users on Twitter via @mentions of other users who are notified and prompted to react, @replies to other users and Retweets (RT) of others’ content (Jungherr, Citation2015, pp. 12–15). Therefore, the platform enables direct forms of information distribution, interaction, and dialogical reactions and information mediation through chains of communication.

Research has shown that parties and candidates primarily use Twitter as a broadcast medium and to reach out to party members and activists (Jungherr, Citation2016b; Podschuweit & Haßler, Citation2015). However, simply using the platform to disseminate information from the top down does not fully reflect the potential affordances of the service. Parties need to not only connect to other users but also attract user interactions to gain salience and popularity and spread their messages through individual networks to the wider public (Ernst et al., Citation2017; Podschuweit & Haßler, Citation2015). The multi-directionality of communication in social media (Benkler, Citation2006; Benkler et al., Citation2015) enables organizations and ordinary users to establish direct digital connections with parties. We conceptualize the sum of these digital linkages as a micro ecology. Such participation can be viewed as an ‘act of personal expression’ (Bennett & Segerberg, Citation2012, p. 752f.) through which users feed their ideas and actions into public communication. By mentioning a party or politician, users can start a direct interaction, e.g., comment on, support, or challenge statements and actions (Jungherr, Citation2014, Citation2016b). With an @reply, users engage with the person uploading a post by adding information (Boyd et al., Citation2010; Jungherr, Citation2015). By retweeting parties’ or politicians’ content, users engage in information diffusion by copying and rebroadcasting to their networks. Meanwhile, retweeting can also be seen as a conversational practice through which users signal listening to someone, endorsement, validation, loyalty, etc. (Boyd et al., Citation2010; Bruns & Highfield, Citation2015; Jungherr, Citation2016b).

Organizations at the intersection of institutionalized politics and the periphery are important actors in this micro ecology, such as movement organizations and the variety of alternative information providers belonging to the digital news infrastructure on the right (Heft et al., Citation2020). The digital micro ecology allows for the agency of ‘political entrepreneurs’ who often act in central and network brokerage roles (Christopoulos, Citation2006) and invest political capital for interventions, such as targeting political actors and controlling information flows as sources, drivers, and mediators of attention (Anderson, Citation2010).

2.2. Opportunity structures of parties’ strategic use of digital ties and user interactions

To understand the propensity of RRPs to establish digital connections and the likelihood of user interactions, we take country-specific political and media-related opportunity structures into account. Political opportunity structures have been described by Kitschelt as ‘specific configurations of resources, institutional arrangements and historical precedents for social mobilization’ (Kitschelt, Citation1986, p. 58). With respect to RRPs, we focus on the structural power position of a party in a given country context as a medium-term factor related to the party system (Arzheimer & Carter, Citation2006) and the EP elections as a short-term contextual factor. In addition, we take the suitability of the platform Twitter for politicians’ and individual users’ communicative goals (Ernst et al., Citation2019) into account, thus providing one aspect of a media-related opportunity structure for mobilization.

2.2.1. National structural power position

The structural position of a party in its national political system has been shown to account for variations in parties’ strategic digital connections (Ackland & Gibson, Citation2013). In general, marginalized or extreme parties and groups tend to associate with ideologically similar allies to support each other’s messages, gain followers, and compensate for their disadvantaged position in mainstream discourse. For marginalized groups, digitally acknowledging each other (Ackland & Gibson, Citation2013; Caiani & Parenti, Citation2013; Pavan & Caiani, Citation2017) and reaching out for alliances within and across borders (Burris et al., Citation2000; Gerstenfeld et al., Citation2003) is particularly important. The RRPs in our study differ by their acceptance and power position in their national contexts. Some represent opposition parties that are marginalized in mainstream media and political discourse to varying degrees, while others are heads of or at least part of governments. We can hypothesize that the opposition parties, due to their exclusion from political power, are likelier to establish digital connections and seek allies both within and across their national partisan communities. Opposition parties with a young history particularly are likely to uphold organizational and personal ties with ideologically close challenger organizations, both in the media and other social sectors (Weisskircher & Berntzen, Citation2018). It is therefore reasonable to expect them to establish such ties in their digital communication and connect with challenger organizations and ideologically close allies on the right. Governing RRPs, in contrast, are part of public discourses and mainstream media coverage due to their political power. Thus, reaching out via digital media is expected to be less relevant to their overarching communication repertoire. Furthermore, research has shown that the structure of publics on social media strongly aligns with the party system, thus leading to an online representation of offline political clusters (Reichard & Borucki, Citation2015; Schlögl & Maireder, Citation2015). Therefore, we hypothesize that RRPs in government interact with a broader set of legacy media and other political organizations in their digital communication.

Integration into broader communication networks through user interactions has been described as a critical resource for mobilization and support for RRPs (Ernst et al., Citation2017). Research has shown that messages from populist leaders are likelier to trigger redistribution through RTs or shares than messages from non-populists (Ceccobelli et al., Citation2020). Like our argument concerning RRPs’ strategic top-down communication, we can expect that parties that are less established in their political systems will benefit particularly well from user interactions set up by partisan peripheral organizations and entrepreneurs. These actors may either enact their individual needs or represent challengers on the ground in an attempt to establish and reinforce shared meanings and identities (Melucci, Citation1989, Citation1996). While we expect stronger ideologically aligned connections to opposition parties, RRPs that hold political power positions can be expected to be integrated in broader societal discourses by more diverse, institutionalized political actors and media. In sum, we hypothesize that the digital political communication ecologies of RRPs in government are more diverse in the types (sources, targets) and functions of digital connections, while the opposition parties’ ecologies feature more partisan types and function of connections.

2.2.2. EP election context

The particular context of the EP elections provides an opportunity structure for establishing transnational ties to create and sustain political alliances across Europe. Research has shown that digital links within parties’ own organizations are strong and that they reciprocally enhance the visibility and salience of national, regional, and local party divisions (Reichard & Borucki, Citation2015). However, the propensity to expand discourses across national borders depends on individual issues and actors who initiate a connection (Froio & Ganesh, Citation2019). Hence, transnational organizational ties in the offline world can be expected to be translated into actors’ online communication. During the EP elections, organizational ties of RRPs within the EP fractions indicate shared issues and positions. We therefore hypothesize stronger transnational digital connections in parties’ strategic communication between parties belonging to the same European party group.

The EP campaign also provides a particular context for user engagement. While politicians are constrained in their political communication by the EP electoral system with its nationally defined voter bases, political entrepreneurs may be less confined by their national contexts, aiming to strengthen their claims through networks across geographically and politically defined borders. Entrepreneurs from civil society and citizens alike can use the EP election context to create alliances through interaction networks across borders. Thus, we hypothesize that political entrepreneurs are likelier to establish transnational connections than party actors.

2.2.3. Twitter’s relevance and reach

Finally, digital media appropriation in a country should influence both parties’ strategic communication activities as well as interactions on the ground. Theocharis et al. (Citation2015) show that the extent of Twitter use in a country impacts the density and diversity of networked connections. The more relevant Twitter is as a tool for political communication in a country—due to its reach and user base—the likelier it is that RRPs will communicate and engage on the platform. Also, popularity cues, such as those represented by the number of followers or the specific style of how political leaders adopt social media tools, influence mobilization capacity (Bracciale & Martella, Citation2017; Hameleers et al., Citation2021). To sum up, we hypothesize that the more relevant and popular Twitter is as a tool for political communication, the likelier are its usage and the formation of digital connections.

3. Study design

In our study, we traced the digital connections on Twitter from and to RRPs from six European countries: Austria’s Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ); France’s Rassemblement National (RN); Germany’s Alternative für Deutschland (AfD); Italy’s Lega; Poland’s Prawo i Sprawiedliwość (PiS); and Sweden’s Sweden Democrats (SD). The parties were selected based on their classifications in the Manifesto Project, the Chapel Hill Expert Survey, and the European Social Survey.Footnote1 They are positioned on the radical right in their countries and have been successful in previous national or European elections. We chose three established parties involved in government at the time: the FPÖ, PiS, and Lega. These were compared with three opposition parties that have been kept from political power: AfD, SD, and RN. Our study covers May 2019, the month of the EP elections.

Concerning the offline organizational ties between the parties at the European level, FPÖ, RN, and Lega have been linked by long-standing organizational connections in the Europe of Nations and Freedom (ENF) fraction of the EP since its foundation in 2015. FPÖ and RN mobilized RRPs in the EP in 2010 to establish a joint parliamentary group (Ivaldi, Citation2018; Schiedel, Citation2017). All three parties also joined the new Identity and Democracy (ID) group after the 2019 EP elections. The AfD is comparatively new; their ideological classification and organizational coalitions at the European level remain volatile (Arzheimer, Citation2015; Backes, Citation2018; Kroh & Fetz, Citation2016). In 2014, the AfD became a member of the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) to avoid an association with parties such as France’s RN or Italy’s Lega (Decker, Citation2016). In 2016, they joined Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy (EFDD) (Kroh & Fetz, Citation2016). Due to a more robust radical right profile recently, the party joined forces with Lega, RN, and FPÖ and is now part of the ID group. PiS and SD are both part of the conservative ECR group in the EP. PiS was one of the founding parties of this group in 2009. The SD joined the ECR in 2018. Both parties are distinct: the PiS transformed from a moderate conservative party to a more populist radical right one (Stanley & Czesnik, Citation2019), and the SD gave themselves a softer image after internal party reforms and the split from more radical party fractions (Widfeldt, Citation2008).

4. Measuring digital references – operationalization and data

To measure the macro ecology of parties’ strategic actions, we explored the connections established by the parties in their Twitter communication and use social network analysis techniques to reproduce co-linking networks between the parties and the users they interact with. We operationalized the parties as sources of a connection and the actors linked to via hyperlinks or @mentions, replies and RTs as targets. To access the micro ecology, we collected references (@mentions, RTs, replies) by users (operationalized as sources) that relate to the parties (operationalized as targets) analyzed. This approach allowed us to determine the individual and organizational actors that interacted with the parties and the context in which they are thus placed.

We included the communication on the official party Twitter account and the account of the top candidate (frontrunner) of a party for the EP elections. In case any of these accounts was inaccessible or inactive, we chose the most influential/highest-ranked party official’s account. Likewise, we recorded the interactions of other users with these accounts. We used Crimson Hexagon for data collection, a social media analytic service that has been used in prior research (Faris et al., Citation2017; Isa & Himelboim, Citation2018). It is certified by Twitter and provides full access to current and historical Twitter data, thus offering data access equivalent to using application programming interfaces and allowing the tracking of information related to individual Twitter accounts. For our top-down approach, we used the author specifier (Twitter handle) to collect all tweets created by the party (official party account) and top candidates in May 2019. The bottom-up interactions with the parties and candidates have been collected via the ‘engagingWith’ specifier. This specifier enabled us to collect all the @mentions, replies, or RTs associated with an author (defined via the Twitter handle).Footnote2 Our analyses included the corresponding Tweets in May 2019.

Our approach had a limitation concerning the number of Tweets in a given time frame. We collected all the Tweets of an account as long as a maximum of 50,000 Tweets per month was reached. If this maximum was exceeded, we drew a random sample of 10,000 Tweets per week, resulting in a random sample size of 40,000 Tweets per month. We extracted all references to other actors on Twitter via @mentions, replies, or RTs and references via hyperlinks from the Tweets. We then filtered our data for the top 100 references that the parties and frontrunners made and received each month, thereafter analyzing these networks. Moreover, we extracted all actors and websites from the dataset that are referenced by or a reference to other actors from more than one country and can thus be seen as relevant for transnational communication flows within these networks. An overview of the full database of our study is provided in Tables A1 and A2 in the supplementary online appendix.

For actor classification, we conducted a manual content analysis of the top 100 actors (defined by indegree), which have been connected to by a party or frontrunner, and the top 100 users (defined by outdegree), who interacted with either the official party account or the frontrunner. We classified the actor types by differentiating political, economic, and media entities, different kinds of civil society actors, and, if given, the party affiliation of actors. Additionally, we classified the country of origin and the geographical scope of the actors. Coding, performed by three coders who were either native speakers or highly proficient in the languages of our study, was based on a predefined codebook. Intercoder reliability tests resulted in coefficients of 0.72 for the coding of actors’ country, 0.79 for actor types, and 1 for actors’ party affiliation (n = 50, Krippendorf’s Alpha). We used R (R Core Team 2013) and the packages igraph (Csari & Nepusz, Citation2006), sna (Butts, Citation2016) and network (Butts, Citation2008) for network analysis and visualization.

To evaluate the functions of connections, we performed a manual content analysis of a random sample of 600 Tweets, including 1619 interactions. Based on their content, the classification differentiated between connections established to distribute several types of information, such as information from the campaign itself (‘Updating’), content that promotes an actor or party (‘Promoting’), a specific political position (‘Position taking’), or critiques (‘Critiquing’). Moreover, connections can be established for more directly ‘Acknowledging,’ ‘Mobilizing,’ or ‘Attacking’ another actor (Boulianne & Larsson, Citation2021; Bracciale & Martella, Citation2017; Graham et al., Citation2013, Citation2016; Theocharis et al., Citation2015). We also classified the valence of a reference, distinguishing between positive, neutral, and negative connections. Intercoder reliability (two coders) reached 0.87 for the coding of reference functions and 0.85 for the valence (n = 169 references, Krippendorf’s Alpha). Both codebooks are available in the supplementary material of this paper.

5. Findings

5.1. Activity of RRPs and Twitter users

Examining RRPs’ digital activity based on the number of Tweets in May 2019 revealed considerable differences (see Table A1 in the appendix). The governing parties Lega and PiS as well as the more established RN in France, stood out by a much higher frequency of Tweets than the SD, AfD, and the FPÖ. The numbers reached 7990 in Italy, 2208 in Poland, and 1897 in France, compared to 446 in Sweden, 428 in Germany, and 118 in Austria. The differences in parties’ and candidates’ activities reflect the different adoption rates of Twitter as distinct media-related opportunity structures in these countries. The wider reach of Twitter among the public in Italy, Poland, and France—ranging between 19 and 17 percent (Newman et al., Citation2019)Footnote3—is reflected in the campaign activities of RRPs in those countries. The exceptionally high number of Tweets by Lega and Matteo Salvini accounts for the unique campaigning style of the party under Salvini’s leadership (Bobba, Citation2019). Interaction with the parties reflects both parties’ tweeting activities and the distribution of user attention, as measured by followers (see Table A2 in the appendix). Connections with parties through users’ tweets were markedly the highest in the case of RN (74787 tweets), followed by PiS (58813 tweets) and Lega (54515 tweets). This pattern corresponds to the number of followers that a party can attract. The official Twitter account of RN attracted more than 229,000 followers in May 2019. The Polish PiS has been followed by around 166,500 users, and Italian Matteo Salvini attracted over one million Twitter users at the time.Footnote4 While the parties themselves make greater use of their official accounts, in all countries except Poland, the top candidates attracted proportionally more user engagements per Tweet than the official party handles (see Table A2, Appendix). Overall, the relevance of Twitter and parties’ popularity on the platform present pertinent context conditions of strategic communication and user interactions.

5.2. RRPs’ communication networks: structures and functions

5.2.1. Parties’ strategic communication

The actors addressed in the parties’ communication reflect their structural power position and importance in the national party competition (see ). The governing RRPs refer more frequently to both traditional and alternative online media. This is exemplified by the Austrian and Polish networks in which media such as Krone or Polskieradio24 represent central nodes (measured by indegree; see ). RRPs in government also devote more attention to citizens as they engage with users with individual accounts. Italy’s Lega stands out in this respect, with 29 percent of its digital connections going to individual users. In contrast, all opposition parties tend to remain within their own political spheres with their digital connections. The German AfD is the most confined to the political sector. More than 84 percent of the AfD’s references link to other political accounts, and those primarily represent actors of their own party, that is, sub-divisions of the AfD or individual AfD representatives (92 percent of those references that link to political actors and their respective parties could be determined). Opposition parties are eager to foster the parties’ own digital visibility by linking to their content on other channels (such as the YouTube channel AfD TV with the highest indegree, ) and by linking to affiliates of their own party. Indeed, self-promoting (cross-references between the party and frontrunner accounts) or promoting fellow politicians account for about one-fifth of opposition parties’ digital connections (). Compared to governing RRPs, they also establish a connection to broadcast the parties’ political position more frequently (x2 = 79.70, df = 8, p < 0.001, n = 842).

Table 1. Actor types addressed by parties’ digital connections, May 2019, in percent.

Table 2. Top 20 accounts connected to by parties in Tweets in May 2019, per countries, indegree (ID).

Table 3. Functions of parties’ digital connections (top-down), in percent.

RRPs in power use Twitter to connect to established media and political competitors more frequently. For instance, the SPÖ in Austria attracts the strong attention of the FPÖ (among the top nodes in the Austrian network; ). The references set by governing RRPs primarily function to promote their party and fellow politicians, but they also distribute factual information from news media and other official sources frequently. The FPÖ stands out among the governing parties for critiquing other actors many times, which can be understood as a reflection of internal competition within the governing coalition.

5.2.2. Interacting with parties

Regarding actors who interact with the RRPs, it is primarily private individuals who connect with them by mentioning them, replying to, or retweeting their communication (). While private users form the clear majority of actors in all countries, Poland stands out: Other political actors interacted with the PiS and its top candidate more often than elsewhere. User interactions in Poland are geared less toward promoting the party itself (). Connections more often broadcast factual information as well as political positions and updates on the election campaign.

Table 4. Actor types of user interactions with parties, May 2019, in percent.

Table 5. Functions of user interactions with parties, in percent.

The Austrian, German, and Italian interaction networks displayed a higher diversity of actor types, while the others are built primarily by citizens and political actors (). In Austria, media actors, such as online media and bloggers, are more active in addressing the FPÖ, while in France or Poland, we found almost no interactions originating from media accounts. Movement organizations expected to play a significant role in fostering RRPs’ visibility are little represented in the digital ecologies of all countries. For the users interacting with parties and displaying their party affiliation on their accounts, an interesting pattern was observed: In all countries except Austria, the majority of users are close to or affiliated with the respective RRP to which they relate. The functions of these connections also support our interpretation that the interaction networks primarily serve as mobilization and support structures on the right.

The distribution of actor types shows country-specific differences but no clear patterns regarding the party types analyzed. The functions of these connections highlight the relevance of RRPs’ structural position for user interactions (x2 = 95.13, df = 8, p < 0.001, n = 777). Interactions with opposition parties more frequently help foster and further distribute a party’s own political position. Moreover, promoting party actors by distributing information on the party and the candidates within individual networks is among the main functions when users connect to all parties (). Similarly, through user interactions, campaign updates are propagated to broader audiences. We observed this pattern frequently for the Lega, which attracted links through which Salvini’s campaign messages were distributed further. Interactions with RRPs in government more frequently disseminate additional information and attacks on political opponents.

5.3. Drivers of transnationality

Research has shown that political and societal actors have barely exploited the potential of digital communication for transnational interaction (Froio & Ganesh, Citation2019; Schlögl & Maireder, Citation2015; Stier et al., Citation2021). Although the EP elections in 2019 could have provided a favorable opportunity structure for establishing transnational ties, our data confirmed that RRPs and interacting users devoted their attention primarily to domestic actors. Of 113,783 digital connections in May 2019, we could determine the scope and country of the actors engaged in 91,724 connections (81 percent) via manual content analysis. Of these ties, 8 percent had a transnational scope, meaning that they actually crossed borders, either horizontally through domestic actors connecting to national actors from another country or vertically. Vertical connections include domestic actors addressing transnational institutions and connections between actors that represent transnational entities and refer to national users. Yet, the majority of connections run between national actors of a country (92 percent).

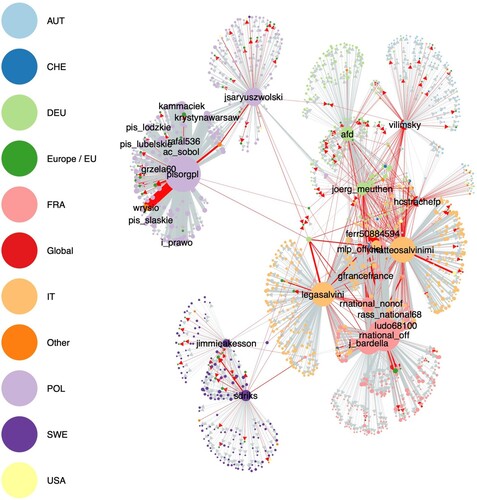

We expected transnational organizational ties offline to become visible in actors’ online communication and result in stronger connections between parties belonging to the same European party group. We also expected political entrepreneurs to be likelier to establish transnational links. depicts the complete network of top-down party communication and user interactions in May 2019.

Figure 1. Networked communication ecology of RRPs and interacting users, May 2019.

Basis: References in parties' and frontrunners' Tweets and interactions with parties and frontrunners in May 2019, n=1427 nodes and 91,724 connections, created with network, igraph, ggplot2 and sna packages in R. Layout: Fruchterman–Reingold. Node size represents indegree, edge strength shows tie weight. Edge color in red if an edge runs between two nodes from different countries or between supranational actors and domestic ones. Edge color in gray if the edge runs between two national actors (nodes) belonging to the same country.

This confirms that most communication circulates in nationally defined country clusters. Furthermore, it highlights transnational connections between the six parties and their surrounding ecologies of different scales: The Polish and the Swedish networked communication ecologies are fairly isolated from the core of the network. Although their Twittersphere includes transnational ties—primarily to supranational actors of the EU or EP members—they are only sparsely connected to the communicative spheres of the other RRPs. In the center of the graph, the parties from Germany, Austria, France, and Italy and their communication ecologies are more strongly integrated and also transnationally linked. The strongest connections run between France and Italy. For example, @matteosalvinimi is not only an important transnational reference point but also shows reciprocal connections to @rnational_off or @afd. Moreover, the Austrian and German clusters are closely connected to the network’s center and exhibit many transnational connections. Thus, the stronger ideological overlap and alliance, as represented by EP fraction membership, manifests in parties’ online ties. Since the majority of all digital connections provide salience and support in broadcasting parties’ campaigns, candidates, and positions—only two percent of user interactions and less than two percent of parties’ top-down connections have a negative valence (see Tables A3 and A4)—we interpret these ties as mobilization and support networks among members of an RRP alliance across Europe.

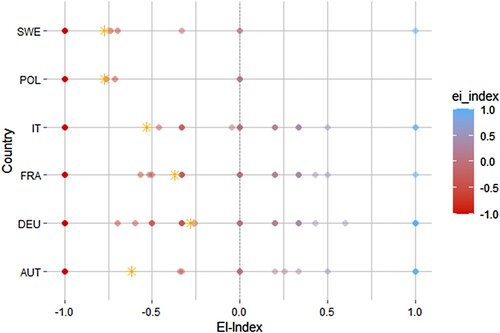

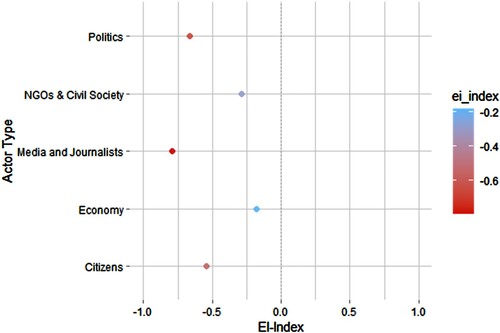

To determine which actors stand out in the transnationality of connections, we applied the Krackhardts and Sterns External-Internal Index (E-I Index) based on country background and scope of an actor as well as the actor type. The E-I Index is node-based, meaning that it considers the number of external and internal connections per node (actor), not the intensity of connections (the weight of a connection). The score ranges from minus 1 to plus 1, the latter signifying that all links of an actor would be transnational, while the former means that all ties are internal, that is, domestic links.

demonstrates that national actors from Sweden and Poland engage almost exclusively in national connections. The mean of French and German actors is closer to zero, representing a higher propensity to establish both transnational and domestic connections. Austria and Italy are located in between. Concerning actor types, shows that no user group has a mean score above zero; all tend primarily toward domestic connections in a national right-wing scene. Yet, it is primarily actors from NGOs and civil society, as well as the field of economics, who are likeliest to establish transnational connections. Since they display the highest degree of openness to relations with actors from other countries, they can be considered drivers of transnationality. Political actors and media actors especially, on the other hand, have the strongest tendency to remain within national ties only. Interestingly enough, individual users display a higher tendency overall toward transnationality than political actors (citizens EI −0.55, political actors EI −0.67). Notably, the country context plays a role in this respect. Political actors in all countries are homogeneously oriented toward domestic connections (ranging between EI −0.99 in Poland and −0.87 in Austria). In contrast, French and German citizens in particular stand out by high transnationality scores (EI −0.16, n = 76, and −0.11, n = 84).

Figure 2. E-I-Index, Transnationality based on actor scope and country, May 2019.

Basis: E-I-value ranges from -1, meaning all connections are internal/domestic, to +1, meaning all connections are external/transnational. Yellow star represents mean EI-Index per country, individual dots represent distribution of individual actors. Number of actors: AUT = 134, DEU = 208, FRA = 225, IT = 308, POL = 266, SWE = 158.

Figure 3. E-I-Index, Transnationality based on actor type, May 2019.

Basis: E-I-value ranges from -1, meaning all connections are internal/domestic, to +1, meaning all connections are external/transnational. Mean EI-Index by Actor Type. Number of actors: Politics = 443, NGOs & Civil Society = 22, Media and Journalists = 321, Economy = 22, Citizens = 613. Actor categories not displayed due to small n: Other = 2, Culture = 4.

6. Conclusion

Our study investigated the digital communication ecologies established by RRPs’ strategic communication and user interactions on a national and transnational scale. To understand how distinct political and media-related opportunity structures in a country align with different types and meanings of connections, we studied the salience, actor types, geographical scopes, and functions of digital connections. RRPs in government and opposition of six European countries were scrutinized during the May 2019 EP election campaigns. We differentiated between a macro ecology resulting from parties’ strategically established connections and micro ecology evolving from user interactions. Together, they provide a networked infrastructure for digital information flows and mobilization of the right.

Our results corroborated the influence of parties’ structural power position on networked communication. The networks of RRPs in opposition appear more strongly confined to actors from their own political sphere, dominated by links to party members and interactions from accounts that show sympathy or affiliation to the respective RRP they support. Thus, the parties’ digital visibility is fostered through promotional links to their content on other channels through cross-references between party members as well as user interactions, which help further distribute information about the RRP, its candidates, and political positions. We can interpret these networks primarily as a self-referential ecology of ‘underdogs,’ established and reinforced by these parties and their allies. The governing RRPs, in contrast, reflect their executive power and country-based party competition by devoting attention to a broader set of actors, including the media, political competitors, and citizens. Their networks function to promote the party, its campaign, and fellow politicians, but likewise to distribute and react to information from other sources. Attacking political opponents is also a more frequent function of these digital connections. Thus, the structural power position seems to be aligned with the less closed structures of these networks, which function to promote and support a party as well as mobilize against competitors.

The analyses also showed that transnationality in these networks reflects offline organizational ties and is made stronger by interactions from civil society, economic actors, and citizens who connect to RRPs across countries more frequently than political actors themselves. The stronger ideological alliances that express themselves in EP fractions are congruent with a network structure that provides salience and support for transnationally closer political allies. Overall, actors from civil society and individual political entrepreneurs, for example, private persons or bloggers, seemed keener to broker between otherwise ‘closed’ national communities in the EP election context. Thus, the overall strong dominance of national connections even in the EP election context can be interpreted as a sign of an enduring second-order status and the nationally oriented election system, which impacts parties’ strategic communication. Political entrepreneurs should be scrutinized further for their propensity to foster transnationality.

Concerning RRPs and their allies as challengers of European democracy in more general terms, their appropriation of digital platforms seems to reflect the inherent tensions between nationalist views and communication strategies and their desire for a transnational alliance on the right. Since alliance building is not only a matter of observable digital communication and mobilization, future studies will benefit from stronger integration of offline factors that may pave the way for synergies and imitation of strategies and actions on the right.

Supplement Material

Download MS Word (62.2 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Annett Heft

Annett Heft is head of the research group Digitalisation and the Transnational Public Sphere at the Weizenbaum Institute for the Networked Society, Berlin, and senior researcher at the Institute for Media and Communication Studies, Freie Universität Berlin. Her main research fields are the comparative study of political communication in Europe, with an emphasis on digital public spheres, right-wing communication infrastructures, transnational communication, and cross-border journalism, as well as quantitative research methods and computational social science [email: [email protected]].

Susanne Reinhardt

Susanne Reinhardt is a researcher and PhD candidate at the Weizenbaum Institute for the Networked Society, Berlin, and the Freie Universität Berlin. Her research focuses on the framing of gender and sexual equality in digital right-wing and mainstream public spheres and its social and political integration into the media in Europe and the US [email: [email protected]].

Barbara Pfetsch

Barbara Pfetsch is a professor of communication science and Head of the Division for Communication Theory and Media Effects at Freie Universität Berlin. Furthermore, she is the principal investigator at the Weizenbaum Institute for the Networked Society. Her work concerns international comparative research on public spheres and political communication as well as issue networks and debates in digital media [email: [email protected]].

Notes

1 https://manifestoproject.wzb.eu/; https://www.chesdata.eu/; https://www.europeansocialsurvey.org/ (01.04.2022).

2 See the official Boolean operator guide https://www.brandwatch.com/p/crimson-hexagon-help-resources/?/hc/en-us/articles/202746249 (13.05.2021).

3 Twitter use among the general population in ascending order: Austria (11 percent), Germany (12 percent), Sweden (16 percent), France (17 percent), Poland (18 percent), Italy (19 percent) (Newman et al., Citation2019).

4 Follower data are from mid-May 2019. They have been collected using the platform Social Blade (socialblade.com, 18.07.2022).

References

- Ackland, R., & Gibson, R. (2013). Hyperlinks and networked communication: A comparative study of political parties online. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 16(3), 231–244. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2013.774179

- Anderson, C. W. (2010). Journalistic networks and the diffusion of local news: The brief, happy news life of the “Francisville Four”. Political Communication, 27(3), 289–309. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2010.496710

- Arzheimer, K. (2015). The AfD: Finally a successful right-wing populist Eurosceptic party for Germany? West European Politics, 38(3), 535–556. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2015.1004230

- Arzheimer, K., & Carter, E. (2006). Political opportunity structures and right-wing extremist party success. European Journal of Political Research, 45(3), 419–443. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2006.00304.x

- Backes, U. (2018). The radical right in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland. In J. Rydgren (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of the radical right (pp. 452–477). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190274559.013.23.

- Benkler, Y. (2006). The wealth of networks. How social production transforms markets and freedom. Yale University Press.

- Benkler, Y., Roberts, H., Faris, R., Solow-Niederman, A., & Etling, B. (2015). Social mobilization and the networked public sphere: Mapping the SOPA-PIPA debate. Political Communication, 32(4), 594–624. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2014.986349

- Bennett, W. L., & Segerberg, A. (2012). The logic of connective action. Digital media and the personalization of contentious politics. Information, Communication & Society, 15(5), 739–768. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2012.670661

- Bobba, G. (2019). Social media populism: Features and ‘likeability’ of Lega Nord communication on Facebook. European Political Science, 18(1), 11–23. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41304-017-0141-8

- Boulianne, S., & Larsson, A. O. (2021). Engagement with candidate posts on Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook during the 2019 election. New Media & Society, Online first. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448211009504

- Boyd, D., Golder, S., & Lotan, G. (2010). Tweet, tweet, retweet: Conversational aspects of retweeting on Twitter. Proceedings of the 43rd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, 1–10. http://bit.ly.

- Bracciale, R., & Martella, A. (2017). Define the populist political communication style: The case of Italian political leaders on twitter. Information, Communication & Society, 20(9), 1310–1329. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2017.1328522

- Bruns, A., & Highfield, T. (2015). Is Habermas on Twitter? Social media and the public sphere. In A. Bruns, G. Enli, E. Skogerbo, A. O. Larsson, & C. Christensen (Eds.), The Routledge companion to social media and politics (pp. 56–73). Taylor & Francis Group. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315716299.

- Burris, V., Smith, E., & Strahm, A. (2000). White supremacist networks on the internet. Sociological Focus, 33(2), 215–235. https://doi.org/10.1080/00380237.2000.10571166

- Butts, C. T. (2008). Network: A package for managing relational data in R. (1.15). The Statnet Project. https://cran.r-project.org/package=network.

- Butts, C. T. (2016). sna: Tools for social network analysis (2.4). https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/sna/index.html.

- Caiani, M., & Císař, O. (2019). Radical right movement parties in Europe. Routledge.

- Caiani, M., & Parenti, L. (2013). European and American extreme right groups and the internet (1st ed.). Ashgate.

- Ceccobelli, D., Quaranta, M., & Valeriani, A. (2020). Citizens’ engagement with popularization and with populist actors on Facebook: A study on 52 leaders in 18 western democracies. European Journal of Communication, 35(5), 435–452. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323120909292

- Christopoulos, D. C. (2006). Relational attributes of political entrepreneurs: A network perspective. Journal of European Public Policy, 13(5), 757–778. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501760600808964

- Csari, G., & Nepusz, T. (2006). The igraph software package for complex network research (1.2.4.1). InterJournal. http://igraph.org.

- Decker, F. (2016). The “alternative for Germany:” factors behind its emergence and profile of a New right-wing populist party. German Politics and Society, 34(2), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3167/gps.2016.340201

- Dolezal, M. (2015). Online campaigning by Austrian political candidates: Determinants of using personal websites, Facebook, and twitter. Policy & Internet, 7(1), 103–119. https://doi.org/10.1002/poi3.83

- Ernst, N., Engesser, S., Büchel, F., Blassnig, S., & Esser, F. (2017). Extreme parties and populism: An analysis of Facebook and twitter across six countries. Information, Communication & Society, 20(9), 1347–1364. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2017.1329333

- Ernst, N., Esser, F., Blassnig, S., & Engesser, S. (2019). Favorable opportunity structures for populist communication: Comparing different types of politicians and issues in social media, television and the press. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 24(2), 165–188. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161218819430

- Faris, R., Roberts, H., Etling, B., Bourassa, N., Zuckerman, E., & Benkler, Y. (2017). Partisanship, propaganda, and disinformation: Online media and the 2016 U.S. Presidential election. Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society Research Paper.

- Friedland, L. A., Shah, D. V., Wagner, M. W., Wells, C., Cramer, K. J., & Pevehouse, J. C. W. (2022). Battleground. Asymmetric communication ecologies and the erosion of civil society in Wisconsin. Cambridge University Press.

- Froio, C., & Ganesh, B. (2019). The transnationalisation of far right discourse on Twitter. Issues and actors that cross borders in Western European democracies. European Societies, 21(4), 513–539. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616696.2018.1494295

- Gerstenfeld, P. B., Grant, D. R., & Chiang, C. (2003). Hate online: A content analysis of extremist internet sites. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 3(1), 29–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-2415.2003.00013.x

- Graham, T., Broersma, M., Hazelhoff, K., & van ‘t Haar, G. (2013). Between broadcasting political messages and interacting with voters: The use of Twitter during the 2010 UK general election campaign. Information, Communication & Society, 16(5), 692–716. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2013.785581

- Graham, T., Jackson, D., & Broersma, M. (2016). New platform, old habits? Candidates’ use of twitter during the 2010 British and Dutch general election campaigns. New Media & Society, 18(5), 765–783. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444814546728

- Hameleers, M., Schmuck, D., Bos, L., & Ecklebe, S. (2021). Interacting with the ordinary people: How populist messages and styles communicated by politicians trigger users’ behaviour on social media in a comparative context. European Journal of Communication, 36(3), 238–253. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323120978723

- Häussler, T. (2021). Civil society, the media and the internet: Changing roles and challenging authorities in digital political communication ecologies. Information, Communication & Society, 24(9), 1265–1282. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2019.1697338

- Heft, A., Mayerhöffer, E., Reinhardt, S., & Knüpfer, C. (2020). Beyond Breitbart: Comparing right-wing digital news infrastructures in Six western democracies. Policy & Internet, 12(1), 20–45. https://doi.org/10.1002/poi3.219

- Isa, D., & Himelboim, I. (2018). A social networks approach to online social movement: Social mediators and mediated content in #FreeAJStaff twitter network. Social Media + Society, 4(1), https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305118760807

- Ivaldi, G. (2018). Contesting the EU in times of crisis: The front national and politics of euroscepticism in France. Politics, 38(3), 278–294. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263395718766787

- Jungherr, A. (2014). The logic of political coverage on twitter: Temporal dynamics and content. Journal of Communication, 64(2), 239–259. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12087

- Jungherr, A. (2015). Analyzing political communication with digital trace data: The role of twitter messages in social science research. Springer.

- Jungherr, A. (2016a). Four functions of digital tools in election campaigns: The German case. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 21(3), 358–377. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161216642597

- Jungherr, A. (2016b). Twitter use in election campaigns: A systematic literature review. Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 13(1), 72–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/19331681.2015.1132401

- Kitschelt, H. P. (1986). Political opportunity structures and political protest: Anti-nuclear movements in four democracies. British Journal of Political Science, 16(1), 57–85. https://doi.org/10.1017/S000712340000380X

- Kroh, M., & Fetz, K. (2016). Das Profil der AfD-AnhängerInnen hat sich seit Gründung der Partei deutlich verändert. DIW Wochenbericht. http://hdl.handle.net/10419/146530.

- Larsson, A. O. (2015). Green light for interaction: Party use of social media during the 2014 Swedish election year. First Monday, 20(12), https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v20i12.5966

- Larsson, A. O., & Kalsnes, B. (2014). ‘Of course we are on Facebook’: Use and non-use of social media among Swedish and Norwegian politicians. European Journal of Communication, 29(6), 653–667. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323114531383

- Lefkofridi, Z., & Katsanidou, A. (2018). A step closer to a transnational party system? Competition and coherence in the 2009 and 2014 European parliament. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 56(6), 1462–1482. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12755

- Melucci, A. (1989). Nomads of the present: Social movements and individual needs in contemporary society. Temple University Press.

- Melucci, A. (1996). Challenging codes: Collective action in the information age. Cambridge University Press.

- Mudde, C. (2019). The far right today. Polity.

- Newman, N., Fletcher, R., Kalogeropoulos, A., & Nielsen, R. K. (2019). Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2019. https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/inline-files/DNR_2019_FINAL.pdf.

- Oelsner, K., & Heimrich, L. (2015). Social media use of German politicians: Towards dialogic voter relations? German Politics, 24(4), 451–468. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644008.2015.1021790

- Pavan, E., & Caiani, M. (2017). Not in my Europe”: extreme right online networks and their contestation of EU legitimacy. In M. Caiani, & S. Guerra (Eds.), Euroscepticism, democracy and the media (pp. 169–193). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-59643-7.

- Podschuweit, N., & Haßler, J. (2015). Wahlkampf mit Kacheln, sponsored ads und Käseglocke: Der Einsatz des Internet im Bundeswahlkampf 2013. In C. Holtz-Bacha (Ed.), Die Massenmedien im Wahlkampf: Die Bundestagswahl 2013 (pp. 13–40). Springer VS.

- Reichard, D., & Borucki, I. (2015). Mehr als die Replikation organisationaler Offline-Strukturen? Zur internen Vernetzung von Parteien auf Twitter - das Beispiel SPD. In M. Gamper, L. Reschke, & M. Düring (Eds.), Knoten und Kanten III. Soziale Netzwerkanalyse in Politik- und Geschichtswissenschaft (pp. 399–421). transcript.

- Schiedel, H. (2017). Antisemitismus und völkische Ideologie. Ist die FPÖ eine rechtsextreme Partei? In S. Grigat (Ed.), AfD & FPÖ. Antisemitismus, völkischer Nationalismus und Geschlechterbilder (pp. 103–120). Nomos. https://doi.org/10.5771/9783845281032.

- Stchlögl, S., & Maireder, A. (2015). Struktur politischer Öffentlichkeiten auf Twitter am Beispiel österreichischer Innenpolitik. Österreichische Zeitschrift Für Politikwissenschaft, 44(1), 16–31. https://doi.org/10.15203/ozp.213.vol44iss1

- Stanley, B., & Czesnik, M. (2019). Populism in Poland. In D. Stockemer (Ed.), Populism around the world. A comparative perspective (pp. 67–87). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-96758-5.

- Stier, S., Froio, C., & Schünemann, W. J. (2021). Going transnational? Candidates’ transnational linkages on twitter during the 2019 European parliament elections. West European Politics, 44(7), 1455–1481. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2020.1812267

- Theocharis, Y. (2015). The conceptualization of digitally networked participation. Social Media + Society, 1(2), https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305115610140

- Theocharis, Y., Lowe, W., van Deth, J. W., & García-Albacete, G. (2015). Using Twitter to mobilize protest action: Online mobilization patterns and action repertoires in the Occupy Wall Street, Indignados, and Aganaktismenoi movements. Information, Communication & Society, 18(2), 202–220. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2014.948035

- Weisskircher, M., & Berntzen, L. E. (2018). Remaining on the streets. Anti-islamic PEGIDA mobilization and its relationship to far-right party politic. In M. Caiani, & O. Císař (Eds.), Radical right movement parties in Europe 1st ed. (pp. 114–130). Routledge.

- Widfeldt, A. (2008). Party change as a necessity – The case of the Sweden democrats. Representation, 44(3), 265–276. https://doi.org/10.1080/00344890802237031

- Young, L. E., & Leonardi, P. M. (2012). Social issue emergence on the web: A dual structurational model. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 17(2), 231–246. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2011.01566.x