ABSTRACT

Through the collection of digital media and engagement with underrepresented groups, memory institutions aspire to preserve and interpret a range of contemporary perspectives on culture and identity. These institutions simultaneously seek to provide experiences that foster civic identities and cultural citizenship. This article explores the potential of collecting internet memes, a specific form of digital media, to further these institutional aims. Through an empirical study of a youth engagement program at a Norwegian folklore archive, we conclude that collecting and contextualizing image macros in collaboration with young people is an institutionally viable and inclusionary approach to documenting new expressions of culture and everyday life. The project further created a context in which young people could exercise competencies related to the development of a civic identity. These findings are relevant for cultural heritage institutions which aim to diversify the forms of digital media, knowledge practices and perspectives represented in their collections, and for cultural heritage professionals who aim to engage youth or marginalized communities. Extending recent research on internet memes as resources for meaning-making the study also underscores the value of participatory research methodologies which deliberately invite individuals’ interpretations of digital culture and analytical approaches that account for the richness of internet memes and image macros as semiotic resources for narrating identity.

Introduction

Tradition archives are an established and crucial part of the world’s social memory and cultural heritage. Referring to a range of organizations that collect and preserve ‘documentation of informal expression and everyday life, often of non-elite groups’ (O’Carroll, Citation2018, p. 15), tradition archives include ethnology and oral history collections as well as other forms of cultural heritage. At the core of many tradition archives are collections of folklore, defined as ‘vernacular patterns, practices, and performances that display multiple existence and variation’ (Buccitelli, Citation2018, p. 5). Historically, through a broad range of collection methods and participatory practices, citizens have contributed content about customs, rituals and traditions to tradition archives; they have shared personal memories, narratives and beliefs that become part of a nation’s folklore and cultural heritage. As memory institutions with a civic mission (Harvilahti et al., Citation2018), tradition archives thus function as knowledge brokers for both the academic community and the broader public in a quite concrete and material sense, actively collecting, documenting, and making available representations and iterations of cultural life (O’Carroll, Citation2018).

Today, this history of contributory practice is aligned with polices in memory institutions that are increasingly focused on fostering civic identity and cultural citizenship (Miller, Citation2001), a trend that is also attributed to the emergence of digital tools and representations that provide new avenues for dialogue and participation (Kekki, Citation2020; Mihailidis, Citation2020). At the same time, the digital age has heightened critical interest in questions of participation, types of representations, content and sharing in a culture’s memory institutions. As ‘everyone’ participates in producing multitudes of narratives online, questions are raised, for example, about the kind of source material that constitutes tradition archives. Moreover, the role of cultural heritage experts and institutional practices in tradition archives has been called into question, as ‘entities that construct, shape, legitimize and lend authority to specific bodies of knowledge pertaining to people and places’ (O’Carroll, Citation2018, p. 14), and involve cultural heritage experts’ judgments of value, significance and monetary worth (Kidd, Citation2014). Therefore, in addition to practical challenges of transforming paper-based tradition archives to operate in a globalized world of electronic communication, there are important practice-based challenges in the transition to digital heritage archives in terms of whose voices participate in collective remembering (Connerton, Citation1989; Wertsch, Citation2002).

Some of these concerns have been met with a hopefulness about the engagement of young people and marginalized voices and communities (Hauge & Rowsell, Citation2020). Through the contribution of their own narratives, perspectives, and stories, Hauge and Rowsell (Citation2020) suggest that young people are driving ever more critical ways of thinking about the politics of race, sexuality, gender, class and dis/ability in archival practices. As Gholami (Citation2017) points out, the ways in which notions of self, other, community and heritage are defined and experienced are inextricably intertwined with ideas of citizenship in late modernity, transcending national-state models as globalization and migration play an increasingly important role in notions of heritage and collective identity. Moreover, ‘in a dialogue that takes place in the media, self-reflection is necessary,’ because it requires a different attitude to understand someone from a different ‘homeworld’ (Kekki, Citation2020, p. 231). What is required, then, to develop inclusionary practices and digital culture resources in memory institutions that can engage young people as citizens in developing, critically examining and sharing their perspectives on culture and identity? In this study, we explore the potential of tradition archives as a site for developing young people’s self-reflection and civic identities by inviting them to document their own time and age.

This study was conducted as part of a larger interdisciplinary research project on digitization and knowledge practices in museums and archives, and involved a university partnership with a Norwegian national folklore archive (Norsk Folkeminnesamling/The Norwegian Folklore Archives; NFS) and a year-long youth engagement program initiative called New Voices in the Archive. We focus specifically on a part of the program in which youth contributors (16–19 years old) collected and contextualized internet memes, predominantly in the form of image macros, to document the experiences of young Norwegians for the archive. Memes are a genre of digital media broadly understood in communication studies as a means with which individuals express identity in a participatory culture, and engage in meaning-making processes online (Aguilar et al., Citation2017). Image macros may be defined as a type of meme that is ‘captioned with humorous, sometimes nonsensical text’ (McNeill Citation2013, p.179).

Based on analyses of the young people’s meme collections and their participation in the project, which included interviews and group discussions about their collecting and contextualizing processes, we explore the following questions: In which ways may young peoples’ contributions to tradition archives facilitate the development of civic identities and cultural citizenship? How can memory institutions cultivate institutionally viable approaches to engage young people in contributing to contemporary folklore archives?

Internet memes as expressions of culture and identity

Internet memes, broadly defined as a ‘group of digital items […] created with awareness of each other and […] circulated, imitated and/or transformed via the Internet by many users’ (Shifman, Citation2014, p. 41), have been objects of inquiry in communication and media studies, political science, and folklore. In communication research, Shifman’s (Citation2013) influential conceptualization of internet memes brings together the academic understanding of memes, initially articulated by evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins in The Selfish Gene, as ‘cultural units of transmission […] spread from person to person by copying or imitation’ (Shifman, Citation2013, p. 363), with the emic use of the term ‘meme’ by contemporary internet users. Shifman’s framework has been used to analyse relationships among digital content, such as a video uploaded to YouTube or image macros posted on an online discussion board, to study, among other issues, LGBTQ collective identity, as articulated and negotiated through a social media campaign to support LGBTQ teenagers bullied for their sexual orientation (Gal et al., Citation2016). Other studies have focused on meme hashtags and their role in establishing and developing collective identity, ‘bringing diverse communities of interest together in dialogue and interaction’ (Mihailidis, Citation2020, p. 2).

The digital artifacts known as memes come in many different forms, such as videos, GIFs, and hashtags (Wiggins, Citation2019), and are perhaps most frequently studied as the creation and circulation of image macros. Communication researchers have argued that analysing the spread and variation of internet memes can provide insight into the ‘values and preferences embedded in online communities’ (Seiffert-Brockmann et al., Citation2018, p. 2862), as those values and preferences relate to formal political processes and to popular culture. In a similar vein, Ask and Abidin (Citation2018) use the genre ‘student problem’ memes to investigate students’ personal experiences with contemporary higher education. An analysis of memes posted on the Facebook page ‘Student Problems’ demonstrates that circulating memes about procrastinating or feeling overwhelmed by the demands of everyday life was a way to ‘express potentially shameful experiences’ (Ask & Abidin, Citation2018, p. 844). Another recent analysis (Aguilar et al., Citation2017) has explored how ‘religious’ memes can be understood as expressing a diversity of positions about religious beliefs and experience. These studies depart from the premise that people make meaning about religion, civic life, and student life by creating, circulating, and looking at internet memes.

A small number of studies provide some grounds for understanding memes from the perspective of the individuals who create them or use them in communication, which is the focus of this study. A recent review of literature on youth well-being and the use of digital media (Ito et al., Citation2020), for example, has highlighted the role of media circulation as an expression of social support, and suggests that among young people ‘sharing memes and laughing virtually together has become a common mode of communication online’ (p. 14). A recent study grounds the interpretation of memes in ethnographic engagement with specific online contexts. In a study of meme use in an online message board, Nissenbaum and Shifman (Citation2017) suggest that knowledge of the community’s unwritten conventions relating to the use of specific memes, and the condemnation of users who violated these shifting, contestable norms, make memes and meme literacy a particularly complex kind of cultural capital. In a different study by Mihailidis (Citation2020), generating memes was explored as means of engaging young people in civic and political expression. The study found that the young people generally perceived memes as most relevant for ‘personal and non-serious expression’ (Mihailidis, Citation2020, p. 3) and it asserted the need for intervention-based studies that could positively impact young people’s attitudes toward the civic potential of emergent online communication. As discussed below, an ‘intervention’ research design was also applied in this study, to explore how the exercise of young peoples’ civic identities might be facilitated through their participation in cultural heritage knowledge work.

As shown in these studies, a broad range of themes and approaches are explored in the research to understand how young people use memes as expressions of identity and means of participating in digital culture and contributing to online discussions. Importantly, for the context of this study, many of these themes and approaches to studying meme use are consistent with how folklorists have approached the study of memes. Folklore studies explore digital-born folk phenomena as expressive forms, as community building online and as part of transnational social media that reveal how ideas about ethnic identity are represented, discussed or negotiated (Blank, Citation2009, Citation2012; Buccitelli, Citation2018). In Tolgensbakk’s (Citation2018) insightful ethnographic study of young Swedes in Norway, for example, ‘meme’ is understood as an emic category to explore how the use of memes in a closed Facebook group constitutes playful and humorous expressions of ethnic in-group belonging. In this study, we similarly explore how the selection and description of memes by the young people participating in this project express aspects of civic identities and cultural citizenship.

The project: New Voices in the Archive

As Reinsone (Citation2018) has pointed out, ‘current digital participatory practices [in cultural heritage] should be interpreted as a continuation of a long-lasting cooperation of tradition archives with society’ (Reinsone, Citation2018, p. 292). Since its founding as a tradition archive in 1914, the NFS has had the aim of documenting informal expressions, creativity and everyday life and represents more than a century’s work to collect, preserve, and present cultural-historical texts and source materials linked with popular culture including narratives of everyday life and folk poetry such as fairy tales, legends and ballads. This national archive of folklore records, comprising mainly written records of orally transmitted forms of popular narratives collected during the 19th and 20th centuries, has been at the heart of research on Norwegian folklore and cultural history since its foundation, extending the concept of culture to include the experiences of common people and daily life. In 2012, the oldest material – the core of the archive – was selected for inclusion in the Norwegian Memory of the World registry under the auspices of UNESCO. As a tradition archive with national status, it has thus ‘shaped, legitimized and lent authority to specific bodies of knowledge pertaining to people and places (O’Carroll, Citation2018, p. 14).

The physical NFS archive material was decontextualized in its time, archived as separate material categories. The knowledge system at play in mapping the folklore landscape thus gave archivists and historians authority and power to both define folklore and how it could be used (Kverndokk, Citation2018). Digitization of this material is changing established relations between categorizations, definitions and understandings of Norwegian folklore, in both research and communication practices. Moreover, the new cultural heritage mediascape and its models of participation have lowered the threshold for ‘lay’ users to submit digital stories for inclusion in NSF and other tradition archives.

Research design and methodological approach

These larger transformations in the cultural heritage sector serve as the background for the aims of the New Voices project, which were twofold. First, there was a practice-based aim to further develop ways of recording and preserving the diverse experiences of contemporary Norwegians, particularly the multicultural experiences of new generations that are currently underrepresented in the folklore collection. Second, in conjunction with archive’s aims of nourishing civic identities, there was an interest in exploring through participatory approaches what Dahlgren and Hermes (Citation2015) describe as ‘the prerequisites for people to act as citizens in the life of a democracy, both in politics and in civil society more broadly’ (p. 117). The research approach may be described as design-based, (McKenney & Reeves, Citation2019), with three rounds of ‘interventions’ in the archive’s practices to explore how to foster more involvement with young people. Activities in the study were implemented over approximately one year. The research was organized as an interdisciplinary university-archive collaboration (Freeth & Caniglia, Citation2020; Pierroux et al., Citation2021) between researchers at two different faculties at a university (educational sciences and humanities), the latter of which hosts the NFS. The interventions can be understood as iterative ‘solutions’ designed to address the ‘problem’ of a lack of youth involvement at the NFS. The approach draws on methods from design-based research in education (McKenney & Reeves, Citation2019), in which a ‘problem in practice’ is first identified. A solution is then developed and implemented to address the problem, and researchers collect and analyse data about how this intervention plays out. Subsequent interventions are iteratively introduced to refine and study changing practices. For this study interventions were developed, implemented, and researched with the aim of changing ongoing practices at the NFS and contributing to a theoretical and empirical understanding of tradition archives as a site for the development of youths’ civic identities.

The initial intervention involved recruiting upper secondary students (16–19 year-olds) for an evening workshop and backstage tour of the archive’s facilities. Through this activity, seven young people were recruited for the position of folklore research assistant. This position entailed a commitment to participate in several ‘after school’ tasks and meetings for a few months, with remuneration in the form of a gift card for a token amount and a certificate documenting their work experience as research assistant. The main task for the young people was to interview their friends and peers using established archival protocols and interview forms, with the aim of collecting narratives of young Norwegians’ life experiences.

While we, the university researchers, had developed the peer interview task, a focus on internet memes as archival material emerged coincidentally, through dialogue with the research assistants. Their interview materials had included some brief references to internet memes, and during informal talk at the beginning of a meeting, the archive researcher (second author) suggested that research assistants consider sending memes to the archive. The possibility of being a ‘meme researcher’ or collector was raised later in the meeting when the archive researcher made a connection between internet memes and folklore research, as an example of the academic study of digital folklore (Rees, Citation2021). Several of the research assistants responded enthusiastically to the idea of being a meme researcher. After reflecting on the enthusiasm with which the young people talked about memes, we concluded that collecting memes was a relevant focus for what now became a more participatory research collaboration (McKenney & Reeves, Citation2019).

The research assistants completed three ‘memes tasks’: collecting and tagging memes; contextualizing a subset of the collected memes with a short text; and curating a meme for the archive’s public Facebook page. The data corpus for the overall study comprises 850 memes collected and tagged by seven research assistants as a part of the New Voices project, 120 of which were contextualized with a short text; four hours of video recordings of meetings and group interviews; and seven responses to an evaluation questionnaire collected at the end of the project.

Analytical approach

The aim of the empirical analysis in this study is twofold: to identify how the memes function as a performative narration of self for a young adult living in Norway, and to explore how the relationships that emerged between the archive and the research assistants may be linked with concepts of civic identities and cultural citizenship. Identifying the kinds of relationships that emerged in the project provides an empirical basis for assessing how and whether their participation involved ‘opportunities for self-creation and meaning-making which serve to enhance the attributes needed for civic agency’ (Dahlgren & Hermes, Citation2015, p. 118).

In the analysis that follows, we consider these relationships in terms of the youth research assistants’ stance-taking (Du Bois, Citation2007), and specifically how stance-taking may be entangled with their approach to the task of describing particular memes. Limor Shifman’s (Citation2013) influential conceptualization of memes as ‘trinities of content, form and stance’ (p. 368) builds on the work of Du Bois and others. Shifman’s (Citation2013) memetic dimension of stance describes ‘the ways in which addressers position themselves in relation to the [meme as] text, its linguistic codes, the addressees, and other potential speakers’ (p. 367). She has observed that ‘people may share a certain video with others for many different reasons (spanning from identification to scornful ridicule), but when they create their own version of it, they inevitably reveal their interpretations of the text’ (Shifman, Citation2013, p. 368). The memetic dimensions of content, form and stance are thus specifically used to explore the creation of internet memes. In the analysis that follows we return to Du Bois’ notion of stance-taking for its relevance to the selection and description of image macros in the New Voices project, rather than the creation of new versions or iterations of a meme in other online settings.

We use stance-taking as an analytical concept to understand the selection and curation of memes by the youth research assistants as a communicative act (Linell, Citation1998). Stance-taking, as ‘a linguistically articulated form of social action’ (Du Bois, Citation2007, p. 139), can only be understood in its dialogic context. Analysing the meaning of a particular stance-act, therefore, involves attention to three sets of relationships. The first relationship is between the stance-taker, as a subject and the object of her stance act, in this case, the relationship between a youth research assistant and the image-macro she selects and describes for the New Voices project. The second relationship is between the stance-taker and other subjects, towards whom the stance-act is addressed. In our case, subjects addressed by youth research assistants include ourselves, as researchers in the project and imagined future users of the archive.Footnote1 The third relationship is between the addressed subjects and the stance object, as inferred by the speaker. This relationship in our case relates to a youth research assistant’s assumptions or inferences about how university researchers and future users of the archive might interpret a meme. Approaching the young research assistants’ collections of memes in terms of stance-taking emphasizes that they selected and interpreted memes for the benefit of audiences in the communicative context of the New Voices project.

In line with our understanding of identity as a performative narration of self, situated in specific interactional contexts (Fludernik, Citation2007), we do not presume that the contextualized memes represent the only way the young people interpreted the memes, or that these texts reveal what they ‘really’ do or think about when using memes in other communicative contexts. Instead, we consider their stance-taking and interpretive evaluations to be indicative of who the contributors were willing to be in their interactions with the archive, and the ideological practices about which they were willing to ‘go on the record’ – with the archive, the university researchers, and each other.

As a communicative act, then, posting memes entailed orienting to diverse discursive contexts and managing intersubjectivity through communicative ‘moves’ (Linell, Citation1998; Matusov, Citation1996; Rommetveit, Citation1976). From a sociocultural perspective, intersubjectivity may be defined as ‘mutual understanding and engagement in participants’ definitions of the situation (i.e., their perceptions and understandings of the situation) and sensitivity to each other’s perspectives of the ongoing joint activity’ (Matusov, Citation1996, p. 29). In orienting toward their role as research assistants, the young people communicated their interpretations of the memes to the archive with short texts and hashtags. They also, however, purposefully selected which memes to collect for the archive, an act that performs aspects of their identities beyond the New Voices project and their role as research assistants. Curating and contextualizing memes thus involved multiple literacies (Lankshear et al., Citation1997; New London Group, Citation1995; Pierroux, Citation2012), which include skills gained through the critique and creation of content in digital environments (Buckingham, Citation2007; Mihailidis, Citation2020). Importantly, mastering such ‘literacy events’ (Barton et al., Citation2000) is related not only to a specific type of semiotic representation and communicative context – as in this activity – but also to the identities and ‘learning lives’ of digital youth viewed from a longer trajectory (Erstad, Citation2012).

The analytical procedures were informed by reflexive thematic analysis (Braun et al., Citation2019) and involved several phases of working with the research data collected during the New Voices project. These phases included:

Familiarization with the overall data corpus, including video and audio transcripts of interviews and in-person meetings as well as the meme collections;

Experimenting with categorizing the content (Shifman, Citation2013) of 850 memes, using following categories race/ethnicity; politics; gender; nationality, including references to im/migration; religion; age/generation; and ‘other’ as a placeholder for additional categories;

Narrowing our analytic focus to the contextualized and curated memes, or memes for which the research assistants had included a short descriptive text as well as hashtags (120 memes in total);

Grouping the 120 memes by memes by research assistant and exploring themes that emerged within and across the collections of the seven individuals; and

Considering how the analytic notion of stance (Du Bois, Citation2007) could capture the relationships between the archive and university researchers, the young people, and the memes that were enacted in the collecting task.

Five memes contextualized by four different research assistants are presented below, with all names anonymized in accordance with privacy regulations. The memes were selected to illustrate the diversity of ‘ideas and ideologies’ (Shifman, Citation2013, p. 369) that the research assistants made relevant through their selection. Ideas or topics that appeared in more than one meme collection but which are not represented by the examples below include memes about ‘student problems’ or student life, similar in many respects to the memes discussed in Ask and Abidin (Citation2018); memes about American celebrities and politicians including Donald Trump, Barack Obama, Beyoncé, Taylor Swift, and the Kardashians; teenage romance and (predominately heterosexual) sexuality; and memes about religious-cultural experiences of Islam, similar to some of the religious memes discussed in Aguilar et al. (Citation2017). As other studies of internet memes have demonstrated (Wiggins, Citation2019), categorizing the memes only in terms of content proved to be analytically problematic. In the analysis that follows, research assistants’ descriptions of memes are quoted in translation. To increase the transparency of the analytical process, the full text of the descriptions in Norwegian and English can be found in the supplementary materials (https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2022.2131363).

Taking a stance towards memes, the archive and the researchers

The meme collecting task offered the young people the opportunity to take a stance in relation to the archive as ‘meme-literate experts’. The analysis of their stance-taking shows that the young people did indeed adopt an expert stance and illustrates how this was enacted. The analysis also suggests that the research assistants approached the meme collecting task as a means of narrating or making visible facets of their identity other than meme literacy, drawing on a kaleidoscopic range of contemporary cultural knowledge and experience as they selected and interpreted memes. Stance-taking as a meme-literate expert can be thought of as addressing the archive as an institution, while the performative narration of identity enacted through selecting and interpreting specific memes can be thought of as addressing the university researchers, their fellow research assistants and, when curating for the archive’s public Facebook page, a broader audience.

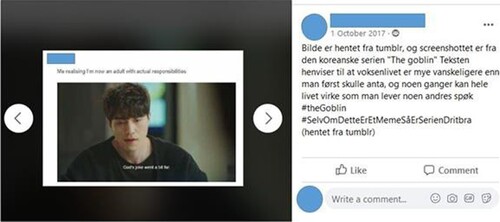

To demonstrate how the research assistants enacted the role of knowledgeable expert in relation to the archive and how this draws on a diversity of cultural knowledge and digital literacies, we analyse stance-taking in three contextualized memes. Ida provided the meme in to the closed Facebook group.

In her description of the image macro in , Ida succinctly indicates where she found the meme, which combines a screenshot from a television series with English subtitles and a short user- generated text (for an English translation of Ida’s description, see Supplementary Materials, ). She then interprets the meme. Ida describes the meme as ‘pointing out’ (henviser til) that being a young adult with increasing responsibilities can feel like being the butt of someone else’s joke. Ida’s text in Norwegian echoes the Tumblr user’s word choice in English (joke/spøk; adulthood/voksenslivet) and her interpretation of the meme appears to parallel the message of the Tumblr user who originally posted it. Ida’s hashtags suggest that for her, knowing the screen shot comes from The Goblin is also an important part of the meaning of the meme. By selecting a meme from The Goblin to contextualize, Ida displays her knowledge and appreciation of a specifically Korean television series, an interest in Korean culture reflected in other contextualized memes from her collection. Ida's text can be understood as addressing the archive and its future users. By including the name of the series as a hashtag and explaining that The Goblin refers to a Korean television show, Ida ensures that her knowledge of k-drama is legible even to readers who may neither recognize the actor nor be familiar with the title of the series. Ida’s stance-taking enacts a relationship with the archive in which her pop culture literacy allows her to interpret the meme, and which accounts for the possibility that the archive as an institution will lack this knowledge of global pop culture.

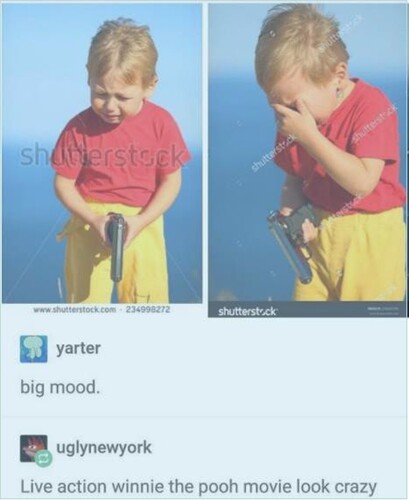

Karoline similarly enacts a relationship with the archive in which she positions a knowledge of memes as a genre as essential to its interpretation ().

Karoline’s description of the image macro in begins by calling attention to the content of the photographs (a crying child holding a gun) and identifies the photographs as stock images (for the full text of Karoline’s description, see Supplementary Materials, ). She then explains that combining stock images with ‘funny comments’ is one way to create ‘an instant meme’ and interprets the two comments that appear under the photographs. Karoline suggests that the first commenter uses the phrase ‘big mood’ to suggest that the image evokes a recognizable feeling ‘in that you can feel vulnerable and maybe in a position of too much responsibility.’ The second commenter instead ‘lightens the situation’ by playfully explaining the existence of this surreal and ‘incomprehensible’ stock image.

Karoline’s description of the meme demonstrates her knowledge of memes as a genre in several respects. She defines the photograph as a stock image and identifies the combination of stock image and comment as a recognizable strategy for creating a meme. Her description further distinguishes between the two commenters’ interpretations of the images (as a visual metaphor for a ‘relatable’ feeling in the first, or as a nonsensical riff on a Disney character in the second). She additionally specifies how the second commenter makes a connection between the stock image and the character Winnie the Pooh by noting the ‘similarity in the boy’s outfit and figure.’ Karoline’s interpretation of the meme involves an appreciation of internet memes as a genre, and a focus specifically on how dimensions of content and form function within the genre. Her stance-taking in the interpretation involves positioning herself as well-versed in the visual and textual conventions of internet memes. Like Ida, Karoline ensures that the archive will understand her interpretation by translating and explaining these conventions.

A number of memes contextualized by Amira involve particularly clear instances of definition and translation. During one of the first weeks of the New Voices project, Amira posted more than 30 ‘habesha memes’ to the closed Facebook group. She introduced the group of memes with the following comment: ‘Here are some habesha memes. Habesha is a group of people in East Africa (ethiopians and eritreans). Can for ex. be compared with scandinavians [sic]’. She then explained a specific Habesha meme () that includes the hashtag #FasikaClapBack.

In her description of the image macro in , Amira defines Fasik (‘Easter in Ethiopia/Eritrea’) and clapback (‘involves dissing someone back’) and sets the meme in the context of the American social media trend of posting ‘savage’ responses to prying family members under the hashtag #thanksgivingclapback (see Supplementary Materials, for the full text of Amira’s description). Amira’s collection of Habesha memes reveals not only her identity as someone who is knowledgeable of Habesha cultural experiences, but also as someone who is fluent in the specific, contemporary vernacular of Habesha identity as it is mediated by and performed through the conventions of social media. By offering definitions and explanations that enable the archive to understand the meaning of these memes, Amira’s stance positions the archive as lacking knowledge of the lived experience of Habesha-as-diaspora in Norway and literacy in the vernacular of social media through which she frames these experiences. The selection of this content thus expresses identity in the sense of cultural citizenship, ‘which acknowledges that one can have multiple affinities to ‘former’ languages, places, or norms and to adopted countries’ (Miller, Citation2001, p. 184).

To summarize the analyses of the memes above, the young people’s role of knowledgeable expert is enacted through two intertwined moves using texts and hashtags. First, the research assistants interpreted the meme, in the sense of making explicit one of the meme’s many meaning potentials. This entailed translating or decoding visual and linguistic references. With reference to Du Bois (Citation2007) stance-taking framework, the researcher assistants’ interpretive move can thus be partly understood as a positioning of the research assistant in relation to the artifact. The second move involved situating the interpretation of the meme in relation to other subjects, specifically, between the research assistant and the archive to which the stance-act is addressed.

As the three examples from the individual collections suggest, the research assistants performed a narration of self through the collection and description of memes that were ‘about’ quite different content and employed different visual forms. At the same time, their interpretations do similar work in addressing the archive as an institution. In their texts, Ida, Karoline and Amira positioned the archive as requiring an explanation of the meme by specifying those aspects of the meme’s semiotic code assumed to be illegible. They then translated these codes to render the meme legible. Their performance of a knowledgeable expert identity demonstrates that the research assistants adopted the framing of their role in the project as literate curators and interpreters of digital culture. Moreover, incorporating this knowledge into their descriptions of the memes is a substantive contribution to the archive, preserving aspects of contemporary youth experience through a literacy in digital culture that may otherwise have been illegible.

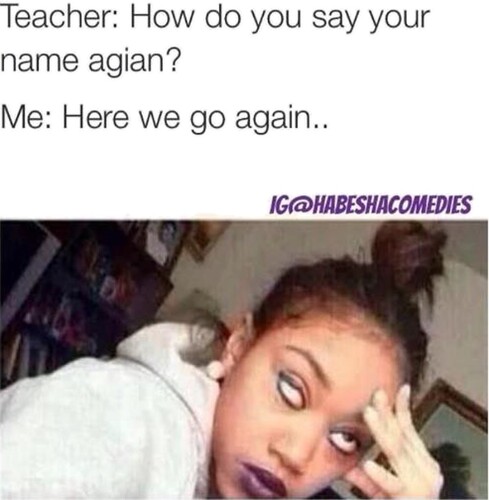

Although translating and defining memes was a prevalent communicative move, it was not the only stance taken in all the research assistants’ contextualizing descriptions. In contrast to translating concepts and words for the archive to contextualize the #FasikaClapBack meme in , Amira’s description of the meme in does not involve explaining elements of the meme’s content and form.

Amira’s short description of the image macro in specifies that ‘all foreigners’ can relate to the experience of having their name mispronounced by a teacher, echoing and expanding on the apparent meaning of the meme’s creator (see Supplementary Materials, for Amira’s description in Norwegian). For Habesha young women, this pairing of image and text suggests, having one’s name mispronounced or not said at all in school is an exasperating and all-too-familiar experience. Amira’s stance-taking might be interpreted as only implicitly identifying with the content through her use of the second person ‘your name.’ In the context of other memes from her collection and her interactions in meetings with the university researchers, however, Amira’s text can be read as an invitation to see specific, mundane experiences of marginalization as a part of her experience of being young and Norwegian. In this sense, the selection and contextualization of this meme suggests that it is linked with her identity, a performative narration of self, and is perhaps addressed more to other project members than to the archive as institution.

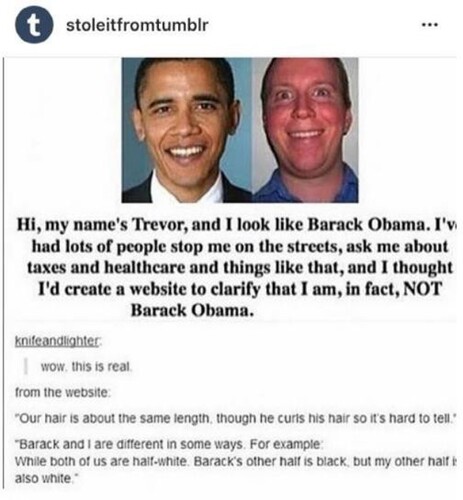

The final example comes from early in the project, when Ali posted the meme in . Ali tagged the archive researcher in his description; she subsequently replied.

Ali’s description of the image macro in might be understood as positioning the archive as a potential source of knowledge about a meme that he is both interested in and does not understand, although concluding his comment with a winking emoji would seem to put some ironic distance between himself and such a request for information (for the full text of Ali’s meme and the archive researcher’s response, see Supplementary Materials, ). As the archive researcher’s comment suggests, we interpreted the meme as a satirical or absurdist critique of white Americans who claimed to be ‘color blind’ or to live in a ‘post-racial America’ following the election of Barack Obama. However, critiques of whiteness were also taken up in other memes in Ali’s collection, and in the collections of other research assistants. Therefore, it might be that Ali did in fact understand, to a greater or lesser degree, that the meme is ‘funny’ because it satirizes whiteness, but he was unwilling to ‘go on the record’ about such an interpretation. Including the meme in his collection while taking an unknowing stance and claiming to not ‘get it’ is a way of registering criticism of white obliviousness while still maintaining plausible deniability about such an interpretation. This may be because such a criticism could be understood as addressing not only the archive as an institution but the university researchers as well. Ali’s stance may thus be viewed as an ‘experimental enactment’ and a kind of projection, when ‘hypothetical resolutions may be put to the test in tentative or exploratory social interactions’ (Emirbayer & Mische, Citation1998, p. 990).

In this instance, Ali literally addresses the archive researcher, tagging her by name in his post to the closed Facebook group. Directly addressing the university researchers using Facebook in this way was relatively infrequent. Yet many of the research assistants’ meme collections similarly involved ‘try[ing] out possible identities without committing themselves to the full responsibilities involved’ (Emirbayer & Mische, Citation1998, p. 990) in relation to the university researchers. This is not to suggest that the research assistants’ collections were focused on a single theme or issue (Ali, for example, also submitted memes about Beyoncé and Taylor Swift) but rather that the selection of memes, not just the contextualizing descriptions of them, were a means by which the research assistants could tell us who they were and what they were about, however indirectly.

Discussion

In the New Voices project, internet memes were framed as a cultural phenomenon that is difficult for ‘outsiders’ to understand and as an expressive form or vernacular in which young people are assumed to be literate. Selecting and interpreting memes for the archive thus required the research assistants to account for the perspectives of others when determining which memes to collect and the aspects of a meme that would need explanation. As the analysis of stance-taking above demonstrates, the research assistants made nuanced and sophisticated interpretations of the memes’ content and form, competently reading these rich semiotic resources. The research assistants further ensured that their interpretations would be legible to others by translating or defining specific aspects of the memes in descriptions and hashtags. Through the selection and contextualization work, the research assistants oriented to the positioning of youth in this project as meme-literate experts, acknowledging the real possibility that other research assistants, researchers, and future users of the archive would need this knowledge to interpret the memes.

Accounting for the perspectives of others and considering how our own perspectives shape the way we understand and relate to others is an important competence for participation in public dialogue and civic life in a democracy (Youniss et al., Citation2002). Such a self-reflective attitude is particularly relevant when public dialogues occur in and through networked media (Kekki, Citation2020). In this sense, the young people in this study engaged in activities that ‘enhance the attributes needed for civic agency’ (Dahlgren & Hermes, Citation2015, p. 118). The memes functioned not only as an indicator of young peoples’ concerns and conditions, as Ask and Abidin (Citation2018) suggest, but also required them to account for the perspectives of others when interpreting them. Participating in and contributing to digital culture involves a process of critically reflecting on the concerns and conditions of self and others and considering how these could perhaps be changed (Hauge & Rowsell, Citation2020). Without overstating the perspective-taking or self-reflection involved in the memes task, we suggest that the act of orienting toward and accounting for others’ understanding of digital cultural artifacts can be understood as facilitating the development of a civic identity.

This study suggests that collecting and contextualizing digital media in collaboration with young people is a viable and inclusionary approach for memory institutions to document new expressions of culture and everyday life. Through participation in this project, the young people critically reflected on memes as transnational expressions of and commentaries about global pop culture, multiculturalism, and societal issues (Hatlehol, Citation2012), sharing at the same time their perspectives on culture and identity and what it means to be a young person today. From the archive’s perspective, their contributions and interpretations demonstrate how expressive culture is relevant to the mission of memory institutions, but also how digital cultural artifacts require local competence to grasp their meaning more fully. The New Voices memes collection is quite unique and far richer than computer-harvested collections, in which only an image file of a meme is saved, because the material is contextualized and interpreted by the contributors. This approach to digital collecting demonstrates how previous analog efforts to collect folklore lack performative context and the degree to which folklorists, rather than their informants, retained control over the interpretation of the archived material.

These lessons in contrast are significant in terms of making visible and eventually transforming knowledge practices in the archive. The approach to collecting that emerged in collaboration with young people suggests one way memory institutions can address the challenge of incorporating new voices and novel cultural artifacts, responding to evolving expectations about the relationship between archives and publics (Benoit & Eveleigh, Citation2019). Three elements of the design of the project are thus important to emphasize. The memes task was developed in response to young people’s interests and literacies; it gave young people the responsibility for selecting which examples of a digital media genre would be collected; and it required them to contextualize or specify a meaning for these artefacts. Each of these choices created an opening for young people to exercise agency in reproducing and transforming the archive’s institutional knowledge practices (Emirbayer & Mische, Citation1998), and to create and elaborate an image of the self to be recognized and acknowledged by others (Fludernik, Citation2007).

The participatory design of the activity also acknowledged the important role of ‘reciprocity’ in citizen humanities projects (Hetland et al., Citation2020). Reciprocity was embodied in the participants’ agency in determining the memes task based on an authentic interest in memes as a form of personal and public expression, but perhaps more relevant, their engagement as research assistants at an archive at the university was highly valued by the young people. Remuneration was in the form of a gift card for a nominal amount and a certificate of their employment as research assistant, which they requested for their resumes. As Esborg (Citation2020) explains, remuneration for citizens’ contributions is an established historical practice in tradition and folklore archives and is thus not a token gesture in this case. The New Voices project became an opportunity for young people to contribute knowledge and demonstrate expertise about memes as modes of political, multicultural and personal expression and to have this expertise recognized and acknowledged by a national memory institution, both in communicative interaction during the project and through the formal integration of their material to the archive’s collections.

In sum, the ways in which ‘contextualized memes’ emerged as a focus for the project, and the literate and knowledgeable stance-taking of the young people in relation to the archive and the researchers, is consistent with an understanding of political and cultural agency (Dahlgren & Hermes, Citation2015) and by extension, the exercise of a civic identity in the context of a national memory institution. The degree to which these experiences can be directly connected to other, important kinds of civic agency, such as participation in elections or other more obviously political forms of advocacy, is an open question. Nevertheless, the process is consistent with aims in the cultural sector for museums and archives to become more inclusive, participatory, and democratic institutions.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (785.4 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Emily C. Oswald

Emily C. Oswald completed her PhD at the Department of Education, University of Oslo. Her research interests include research-practice partnerships in the field of cultural heritage; interaction analysis; and the diverse roles of digital technologies in museum and archival work including public engagement and participation [email: [email protected]].

Line Esborg

Line Esborg is associate professor of cultural history and museology at the Department of Culture Studies and Oriental Languages, University of Oslo. Her research interests include folklore and critical heritage studies, focusing on the various cultural practices involved in memory politics. She also works with the cultural history of knowledge, from early modern popular culture to digital folklore in the present [email: [email protected]].

Palmyre Pierroux

Palmyre Pierroux is professor at the Department of Education, University of Oslo. Her research focuses on meaning making, creativity and knowledge practices in formal and informal learning contexts. Pierroux frequently works with design-based methods and research-practice partnerships to explore how digital media and technologies are transforming learning and teaching in schools and museums, with a particular interest in art, architecture and design as disciplinary domains [email: [email protected]].

Notes

1 The data corpus is rich with instances of interaction among research assistants, both in person and in the closed Facebook group where the memes were collected. Analysis of how these interactions may have intersected with or influenced the selection and interpretation of memes for the project is, however, beyond the scope of this article.

References

- Aguilar, G. K., Campbell, H. A., Stanley, M., & Taylor, E. (2017). Communicating mixed messages about religion through internet memes. Information, Communication & Society, 20(10), 1498–1520. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2016.1229004

- Ask, K., & Abidin, C. (2018). My life is a mess: Self-deprecating relatability and collective identities in the memification of student issues. Information, Communication & Society, 21(6), 834–850. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2018.1437204

- Barton, D., Hamilton, M., & Ivanič, R. (2000). Situated literacies: Reading and writing in context. Routledge.

- Benoit, E., & Eveleigh, A. (2019). Participatory archives: Theory and practice. Facet Publishing.

- Blank, T. J. (2009). Folklore and the internet: Vernacular expression in a digital world. Utah State University Press.

- Blank, T. J. (2012). Folk culture in the digital age: The emergent dynamics of human interaction. Utah State University Press.

- Braun, V., Clarke, V., Hayfield, N., & Terry, G. (2019). Thematic analysis. In P. Liamputtong (Ed.), Handbook of research methods in health social sciences (pp. 843–860). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-5251-4_103

- Buccitelli, A. B. (2018). Race and ethnicity in digital culture: Our changing traditions, impressions, and expressions in a mediated world. Praeger.

- Buckingham, D. (2007). Introducing identity. In D. Buckingham (Ed.), Youth, identity, and digital media (pp. 1–24). The MIT Press. https://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/26085

- Connerton, P. (1989). How societies remember. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511628061

- Dahlgren, P., & Hermes, J. (2015). The democratic horizons of the museum: Citizenship and culture. In S. Macdonald & R. Leahy (Eds.), The international handbooks of museum studies (pp. 117–138). https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118829059.wbihms107

- Du Bois, J. W. (2007). The stance triangle. In R. Englebretson (Ed.), Stancetaking in discourse: Subjectivity, evaluation, interaction (pp. 139–182). John Benjamins Publishing Company. https://benjamins.com/catalog/pbns.164

- Emirbayer, M., & Mische, A. (1998). What is agency? American Journal of Sociology, 103(4), 962–1023. https://doi.org/10.1086/231294

- Erstad, O. (2012). The learning lives of digital youth—Beyond the formal and informal. Oxford Review of Education, 38(1), 25–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2011.577940

- Esborg, L. (2020). Engaging disenfranchised publics through citizen humanities projects. In P. Hetland, L. Esborg, & P. Pierroux (Eds.), A history of participation in museums and archives (pp. 109–125). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429197536-9

- Fludernik, M. (2007). Identity/alterity. In The Cambridge companion to narrative (pp. 260–273). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CCOL0521856965.018

- Freeth, R., & Caniglia, G. (2020). Learning to collaborate while collaborating: Advancing interdisciplinary sustainability research. Sustainability Science, 15(1), 247–261. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-019-00701-z

- Gal, N., Shifman, L., & Kampf, Z. (2016). It gets better”: Internet memes and the construction of collective identity. New Media & Society, 18(8), 1698–1714. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444814568784

- Gholami, R. (2017). The art of self-making: Identity and citizenship education in late-modernity. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 38(6), 798–811. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2016.1182006

- Harvilahti, L., Kjus, A., O’Carroll, C., Österlund-Pötzsch, S., Skott, F., & Treija, R. (2018). Visions and traditions: Knowledge production and tradition archives: Vol. No. 315. Academia Scientiarum Fennica.

- Hatlehol, B. (2012). Aktivel medborgere gjennom digital historiefortelling. In K. H. Haug, G. Jamissen, & C. Ohlmann (Eds.), Digitalt fortalte historier-refleksjon for læring (pp. 13–28). Cappelen Damm Akademisk.

- Hauge, C., & Rowsell, J. (2020). Child and youth engagement: Civic literacies and digital ecologies. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 41(5), 667–672. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2020.1769933

- Hetland, P., Pierroux, P., & Esborg, L. (2020). A history of participation in museums and archives: Traversing citizen science and citizen humanities. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429197536

- Ito, M., Odgers, C., & Schueller, S. (2020). Social media and youth wellbeing: What we know and where we could go. Connected Learning Alliance. https://clalliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Social-Media-and-Youth-Wellbeing-Report.pdf

- Kekki, M.-K. (2020). Challenges and possibilities of media-based public dialogue: Misunderstanding, stereotyping and reflective attitude. In T. Strand (Ed.), Rethinking ethical-political education (pp. 223–236). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-49524-4_15

- Kidd, D. J. (2014). Museums in the new mediascape: Transmedia, participation, ethics. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.

- Kverndokk, K. (2018). Diciplining the polyphony of the herbarium: The order of folklore in the Norwegian folklore archives. In K. Salmi-Niklander, C. af Forselles, & P. Anttonen (Eds.), Oral tradition and book culture (pp. 92–110). Finnish Literature Society/SKS. https://doi.org/10.21435/sff.24

- Lankshear, C., Gee, J. P., Knobel, M., & Searle, C. (1997). Changing literacies. Open University Press.

- Linell, P. (1998). Approaching dialogue: Talk, interaction and contexts in dialogical perspectives. John Benjamins Publishing.

- Matusov, E. (1996). Intersubjectivity without agreement. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 3(1), 25–45. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327884mca0301_4

- McKenney, S. E., & Reeves, T. C. (2019). Conducting educational design research (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- McNeill, L. S. (2013). Folklore rules: A fun, quick, and useful introduction to the field of academic folklore studies. Utah State University Press.

- Mihailidis, P. (2020). The civic potential of memes and hashtags in the lives of young people. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 41(5), 762–781. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2020.1769938

- Miller, T. (2001). Cultural citizenship. Television & New Media, 2(3), 183–186. https://doi.org/10.1177/152747640100200301

- Nissenbaum, A., & Shifman, L. (2017). Internet memes as contested cultural capital: The case of 4chan’s /b/ board. New Media & Society, 19(4), 483–501. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444815609313

- O’Carroll, C. (2018). Tradition archives as memory institutions in the past and in the future. In L. Harvilahti, A. Kjus, C. O’Carroll, S. Österlund-Pötzsch, F. Skott, & R. Treija (Eds.), Visions and traditions: Knowledge production and tradition archives: Vol. No. 315 (pp. 12–23). Academia Scientiarum Fennica.

- Pierroux, P. (2012). Real life meaning in Second Life Art. In S. Osterud, B. Gentikow, & E. Skogseth (Eds.), Literacy practices in late modernity: Mastering technological and cultural convergences (pp. 177–198). Hampton Press.

- Pierroux, P., Sauge, B., & Steier, R. (2021). Exhibitions as a collaborative research space for university-museum partnerships. In M. Achiam, M. Haldrup, & K. Drotner (Eds.), Experimental museology: Institutions, representations, users (pp. 149–166). Routledge. https://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/48842

- Rees, A. J. (2021). Collecting online memetic cultures: How tho. Museum & Society, 19(2), 199–219. https://doi.org/10.29311/mas.v19i2.3445

- Reinsone, S. (2018). Participatory practices and tradition archives. In L. Harvilahti (Ed.), Visions and traditions knowledge production and tradition archives (pp. 279–296). https://www.folklorefellows.fi/ffc-315/

- Rommetveit, R. (1976). On the architecture of intersubjectivity. In L. H. Strickland, F. E. Aboud, & K. J. Gergen (Eds.), Social psychology in transition (pp. 201–214). Springer US. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-8765-1_16

- Seiffert-Brockmann, J., Diehl, T., & Dobusch, L. (2018). Memes as games: The evolution of a digital discourse online. New Media & Society, 20(8), 2862–2879. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444817735334

- Shifman, L. (2013). Memes in a digital world: Reconciling with a conceptual troublemaker. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 18(3), 362–377. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12013

- Shifman, L. (2014). Memes in digital culture. MIT Press.

- The New London Group. (1995). A pedagogy of multiliteracies: Designing social futures. NLLIA Centre for Workplace Communication and Culture.

- Tolgensbakk, I. (2018). Visual humor in online ethnicity: The case of Swedes in Norway. In A. B. Buccitelli (Ed.), Race and ethnicity in digital culture: Our changing traditions, impressions, and expressions in a mediated world (pp. 115–132). Praeger.

- Wertsch, J. V. (2002). Voices of collective remembering. Cambridge University Press.

- Wiggins, B. E. (2019). The discursive power of memes in digital culture: Ideology, semiotics, and intertextuality. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429492303

- Youniss, J., Bales, S., Christmas-Best, V., Diversi, M., McLaughlin, M., & Silbereisen, R. (2002). Youth civic engagement in the twenty-first century. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 12(1), 121–148. https://doi.org/10.1111/1532-7795.00027