ABSTRACT

To ensure their children's safety online, parents can utilize number of strategies, including active and restrictive parental mediation. Active mediation encompasses parents discussing and advising children about safe usage of the internet, whereas restrictive mediation means limiting children's internet usage. Both strategies aim to affect children's online behavior, especially to minimize online risks. Using a sample of 1031 adolescents aged 11–17 (54% females) and structural equation modeling, we focused on the active and restrictive parental mediation of online interactions and their connections to adolescents’ potentially risky online contacts with new people. In addition, we considered the indirect effect of parental mediation on adolescents’ behavior through adolescents’ risk perception. In this way, we captured one of the potential explanatory mechanisms through which the parental mediation's effect occurs. The results showed that restrictive mediation decreased contacts with new people by increasing adolescents’ risk perception of this activity. In contrast, active mediation had neither a direct nor indirect effect on adolescents’ online contacts. The results enrich the theory of parental mediation by showing that risk perception is an important factor to consider when researchers examine the effects of parental mediation on children's potentially risky online behavior.

Introduction

Adolescents’ interactions with people met on the internet are a common concern among parents (eSafety, Citation2019; Steinfeld, Citation2022). To minimize the potential risks that come with such online interactions, parents can utilize several parenting strategies, collectively labeled as online parental mediation (Kuldas et al., Citation2021). Two particularly prevalent strategies are active and restrictive mediation (Beyens et al., Citation2022; Chen & Chng, Citation2016). Previous research shows that restrictive mediation can be effective in lowering the exposure to online risks, yet at the price of limiting online opportunities and digital-skill development (Livingstone et al., Citation2017). Active mediation, on the other hand, seems to be less effective in directly preventing risk exposure, but it is connected to higher digital skills and better coping after an unpleasant online experience (Shin & Lwin, Citation2017; Wisniewski et al., Citation2015). While a large proportion of research focused on general mediation strategies, less attention has been paid to parental mediation that targets specific aspects of ICT use. Yet, general measurements may not adequately capture the nuances in domain-specific parental mediation and thus, may produce less accurate findings. In our study, we focus on the parental mediation of online interactions (i.e., how parents mediate adolescents’ usage of the internet for communication with other people; Livingstone & Helsper, Citation2008; Symons et al., Citation2019). Such communication can be beneficial but also risky, especially when adolescents share information or photos with new people met on the internet (Borca et al., Citation2015). Thus, we examine how active and restrictive parental mediation of interactions relate to adolescents’ engagement in interactions with new people online. This more focused approach to parental mediation allows us to more precisely capture and understand the effects parenting has on specific adolescents’ behavior.

Moreover, current literature mainly focuses on the direct effect of parental mediation on adolescents’ behavior and does not consider the mechanisms through which the effect occurs (i.e., how parental mediation impacts adolescents’ behavior). Our study aims to enrich the literature by investigating adolescents’ risk perception of online interactions with new people as a possible explanatory mechanism between parental mediation and adolescents’ behavior. Such a focus can bring important insights into how parental efforts function and also shed more light on how adolescents’ evaluation of the online activity shapes their behavior.

Online parental mediation

Online parental mediation is a domain-specific parenting practice that aims to maximize online opportunities and minimize online risks (Livingstone et al., Citation2017; Young & Tully, Citation2022). Two widely used strategies, in particular, received substantial research attention. Active mediation aims to support children's online activities and equip them with the needed skills to utilize the internet efficiently and safely. Thus, it is also sometimes called ‘enabling’ mediation (Livingstone et al., Citation2017) or ‘open’ mediation (eSafety, Citation2019). The specific practices include parents having discussions with children about their online activities, explaining why some things are good or bad, and advising on how to stay safe (Beyens et al., Citation2022; Kuldas et al., Citation2021). Because this strategy promotes children's and adolescents’ critical thinking and their own decision-making, it is often recommended to parents (Shin, Citation2015). However, research shows inconsistent findings regarding active mediation's association with experiencing online risks. For instance, active mediation can help to decrease problematic internet use (Nielsen et al., Citation2019), and it was also linked to the lower disclosure of personal information online (Liu et al., Citation2013). Yet, other studies found no relationship to the examined risks (e.g., Shin & Lwin, Citation2017, who used a composed measure of contact and privacy risks).

The other strategy is restrictive mediation which includes practices like setting rules about internet usage and restricting selected online activities, time spent online, or the places from which the internet can be accessed (Chen & Chng, Citation2016; Ho et al., Citation2017). This strategy was linked to adolescents experiencing fewer online risks, probably because it limits their internet usage, and hence the possibilities to engage in online risky behavior. However, this desirable effect of restrictive mediation is coupled with some drawbacks – it may stifle online opportunities and digital skills (Livingstone et al., Citation2017). Similar to active mediation, there are also studies that show that restrictive mediation had no effect (Keyzers, Citation2021) or that it is linked to more online risks (e.g., Shin & Ismail, Citation2014, who showed that control-based mediation is connected to more risky activities on social media).

There are many reasons for these inconsistent findings, including variability in the measurements, in the sampled population, and in other aspects of the research design (Kuldas et al., Citation2021). Parental mediation is often measured on a general level without focusing on the specific content of the mediation. For instance, the general item may ask how often parents talk to their children about their online activities rather than specifically asking how often they talk about gaming. Using such general measures might obscure the association with a specific activity (e.g., problematic gaming), adding to the inconsistency in the literature. To address this issue, some studies assess domain-specific parental mediation (e.g., parental mediation of gaming: Shin & Huh, Citation2011; or social media: Ho et al., Citation2020). We take the same approach and focus specifically on a frequent domain of adolescents’ ICT activity – online interactions with other people.

Parental mediation of online interactions

Interacting online with others is a daily activity for adolescents. They utilize the internet to chat, call, share pictures or videos, and discuss things with their existing friends, family members, and people they have never met in person (Smahel et al., Citation2020). Such online social interactions have many benefits – adolescents use them to achieve their developmental tasks, such as identity formation and the development of intimacy and sexuality (Borca et al., Citation2015). However, interacting with others online entails risks. For instance, sharing intimate information, personal data, or photos with problematic content (e.g., nude photos) on social networking sites (SNS) raises privacy concerns (Paluckaitė & Žardeckaitė-Matulaitienė, Citation2021; Shin & Kang, Citation2016), and interactions with previously unknown people raise concerns about sexual solicitation and cyberaggression (Hayes et al., Citation2022).

To ensure their children's safety during online social interactions, parents can mediate these interactions. We focus on two types of such interaction mediations. Active mediation of interactions comprises parents discussing online social interactions with adolescents and giving them advice and explanations about the appropriate form, content, and protection strategy during/prior to engaging in the interaction (e.g., advising when sending one's photos is appropriate). Restrictive mediation of interactions reflects setting rules and bans for such interactions (e.g., forbidding talk with unknown people online). Because online interaction often occurs on SNSs, this parental mediation often concerns social media accounts (e.g., privacy settings; Symons et al., Citation2019).

Despite children's online interactions being a common concern for parents, only a handful of studies investigated the parental mediation of interactions, and those that did mostly focused only on its restrictive form (e.g., Livingstone & Helsper, Citation2008; Symons et al., Citation2019). Thus, relatively little is known about the predictors of interaction mediation and their connections to children's behavior. Moreover, existing studies often neglect explanatory mechanisms between parental mediation and their presumed outcomes. In our study, we aim to fill these gaps by investigating (1) how adolescents’ age and gender affect active and restrictive interaction mediation, (2) how these mediation strategies connect to adolescents’ risky behavior related to online interactions (i.e., their online contacts with new people), and (3) whether adolescents’ risk perception of communication with new people online mediates the relationship between parental mediation and the adolescents’ behavior. In the following sections, we describe the rationale for our tested model.

Predictors: adolescents’ age and gender

As children grow older, and especially in adolescence, parents tend to mediate their internet use less. This was shown in cross-sectional as well as longitudinal studies of general active and restrictive mediation (Chen & Chng, Citation2016; Padilla-Walker et al., Citation2012; Steinfeld, Citation2021) and also in studies that specifically examined interaction restrictions (Livingstone & Helsper, Citation2008; Symons, Ponnet, Emmery, et al., Citation2017). The decrease in parental mediation efforts is probably related to adolescents’ increasing self-regulation and growing need for autonomy, which parents perceive as appropriate (Symons, Ponnet, Walrave, et al., Citation2017). We thus propose that:

H1: Adolescents’ age is negatively associated with active (H1a) and restrictive (H1b) parental mediation of interactions.

H2: Adolescent girls report higher levels of active (H2a) and restrictive (H2b) parental mediation of interactions.

Outcome: adolescents’ online contacts with new people

Parents utilize mediation to modify their children's behavior (Beyens et al., Citation2022). Thus, the successful parental mediation of interactions should be reflected in the adolescents’ actual online interactions. In our study, we are specifically interested in online contacts with new people (i.e., people whom the adolescents know only through the internet and have never met offline). Such contacts are common for adolescents. The recent EU Kids Online IV project (Smahel et al., Citation2020) indicates that between 23% (in Italy) and 57% (in Norway) of 9–16-year-old children and adolescents had contact with a previously unknown person on the internet during the preceding 12 months. In the Czech Republic (where the current study was conducted), 44% of 9–16-year-olds had such a contact, ranging from 19% in the youngest group (9–11) to 75% in the oldest group (15–16).

While online interactions with new people offer many potential benefits, they raise substantial concerns among parents and adolescents, especially when the unknown person is an adult (eSafety, Citation2019; Hayes et al., Citation2022; Symons, Ponnet, Walrave, et al., Citation2017). Thus, parental mediation – which aims to ensure the child's safety – should aim to limit contacts with new people online. Several studies examined the association between general parental mediation and online risks, which often include contacts with new people. For instance, Keyzers (Citation2021) focused on the same outcome measure as our study and found that active mediation and restrictions (measured on a general level) correlated positively with adolescents’ contacts with new people online. However, when added to a same model, only active mediation remained significant, while restrictions had no effect. Cabello-Hutt et al. (Citation2018) found that active mediation and restrictions were both associated with lower risks (i.e., a nine-item scale that included communicating with new people online or sending them photos) among 11–17 year-olds. On the contrary, restrictive mediation in Shin and Ismail's (Citation2014) study related to increased contact risks for adolescents on SNS (i.e., adding unknown people to their friend lists), while active mediation related to decreased contact risks. A similar effect of active mediation online risks (including chatting with new people) was also found in (Soh et al., Citation2018) study on 13–15-years-olds. Shin and Lwin (Citation2017) focused on parental, peer, and teachers’ active mediation and adolescents’ online risks (i.e., contacts with new people and sharing personal information with them). When they examined all three types of active mediation in one model, parental mediation had no effect, peer mediation increased adolescents’ online risks, and teachers’ mediation decreased them. As is apparent, there is no clear pattern for how general parental mediation relates to contacts with new people online.

Studies focused on interaction mediation, specifically its restrictive form, provide more consistent results. Livingstone and Helsper (Citation2008) found that rules restricting various forms of online interactions (e.g., instant messages, emails) were correlated with lower engagement in the respective activities among 12–17-year-olds. Though these results may be outdated, a more recent study Symons et al. (Citation2019) corroborates them: both mothers’ and fathers’ interaction restrictions were negatively connected to their adolescent (13–18) child's contacts with new people online. Thus, the restrictive mediation of interaction seems to have the desired impact of lowering adolescents’ contacts with new people.

To our knowledge, only one study assessed the active mediation of interaction. In their study of the parents of 2–12-year-old children, Nikken and Jansz (Citation2014) found that active mediation was associated with more online interactions for their children. While the authors propose that their children's activities predict parental mediation, given the study's cross-sectional design, both causal directions (or bidirectional relationship) are possible. Thus, active mediation may predict more online interactions. Despite this finding, active mediation's presumed aim is still to ensure the children's safety. Since interactions with unknown people are considered risky (Borca et al., Citation2015), we expect the effect of active mediation to be negative. Thus:

H3: Active (H3a) and restrictive (H3b) parental mediation of interactions are associated with lower contacts with new people.

Indirect effect: adolescents’ risk perception

Finally, in our study, we also aim to examine one of the possible mechanisms through which parental mediation may affect risky online behavior – adolescents’ risk perception. According to cognitive approaches to risk-taking behavior, perceived risks (and benefits) play a crucial role in adolescents’ decision-making about participating in potentially risky behavior (White et al., Citation2015). Several studies support the link between risk perception and behavior, specifically for online activities. For instance, Mýlek et al. (Citation2021) found that higher adolescents’ risk perception related to face-to-face meetings with new people from the internet decreased their actual meetings with these people. In a two-wave longitudinal study, Baumgartner et al. (Citation2010a) found that adolescents’ perceived risks of online risky sexual behavior decreased their engagement in it. Notably, the reciprocal effect, which would suggest that participating in the activity increases risk perception, was not supported. Similarly, Ho et al. (Citation2017) found that adolescents’ privacy-related concerns (i.e., risk perception) were positively associated with their intended privacy protection behavior on SNS (i.e., presumably in lower risky behavior). Thus, we presume that:

H4: Adolescents’ risk perception is negatively associated with their contacts with new people.

Thus, we expect an indirect effect of mediation through adolescents’ risk perception:

H5: Active (H5a) and restrictive (H5b) parental mediation of interactions is indirectly associated with adolescents’ engagement in contacts with new people through increasing adolescents’ risk perception.

Method

Participants and procedure

The data for the current study comes from a project focused on the examination of adolescents’ ICT usage and their experiences and evaluation of the online risks. A total of 1031 adolescents aged 11–17 (M = 14.08, SD = 1.44, 54% females) participated in the survey. The data collection took place between April and June 2019 in 32 schools (72 classes) in the South Moravia region of the Czech Republic. The schools were selected from a list of eligible schools in the region. The list initially included all elementary, vocational, and grammar schools (N = 506). We excluded the schools where similar data was collected during the previous year (n = 6) and the schools that participated in an ongoing longitudinal data collection conducted by the authors’ department (n = 3). The schools for the current study were randomly selected with a proportional representation of the adolescents’ age and school type. Data were collected from two classes in most schools.

The research administrators contacted school principals to obtain permission to collect data in selected classes. This process continued until the project's aim to collect data from at least 1000 adolescents was achieved. The questionnaires were filled in online during one school period (45 min) in the presence of a trained research assistant who introduced the project, oversaw the administration process, and debriefed participants.

Standard ethical procedures were followed. We informed the legal guardians of respondents about the purpose and process of data collection, including their and their children's right to refuse participation and skip any item, and we obtained their signed informed consent. After being presented with the same information, the adolescent respondents gave verbal consent at the beginning of the questionnaire administration. Each item included ‘prefer not to answer’ and ‘do not know’ answer options (treated as missing values). The project was approved by the university Research Ethics Committee (EKV-2017-078).

Measures

We tested the dimensionality of the scales using confirmatory factor analysis with a robust maximum likelihood estimator. See the Appendix for the complete item list.

Parental mediation of online interactions

Participants were asked to indicate how often their parents engaged in selected parental mediation practices on a scale from (1) Never to (5) Very often. We developed this scale to capture two mediation strategies: active interaction mediation and restrictive interaction mediation. Active mediation was measured with five items (e.g., ‘Give advice about the information that I can share with unknown people online’), and restrictive with three items (e.g., ‘Forbid me to talk with unknown people online’). The fit of a two-factor model was satisfactory: RMSEA = .06 (90% CI = .05–.07), CFI = .97, TLI = .96, SRMR = .03. The chi-square statistic was significant (χ2 (19) = 81.79, p < .001), likely due to the large sample size. All item loadings were above .61. The correlation between active and restrictive mediation was strong (r = .81), which is in line with other research that examined active and restrictive mediation (e.g., Livingstone & Helsper, Citation2008) and with the parents’ own remarks about the common concurrent usage of both types of mediation in qualitative inquiries (Steinfeld, Citation2021; Symons, Ponnet, Walrave, et al., Citation2017). However, since all items focused on interaction with other people online, we also tested a single-factor model. This model fit was worse: χ2 (20) = 231.15, p < .001, RMSEA = .10 (90% CI = .09–.12), CFI = .91, TLI = .87, SRMR = .05. Because both theory and model fit suggest two dimensions, we proceeded with the first model, and we addressed the strong association between both mediation strategies in the Discussion. The reliability of both the active mediation of interactions (ω = .86, M = 2.23, SD = 1.03) and the restrictive mediation of interactions (ω = .86, M = 2.30, SD = 1.28) was good.

Contacts with new people

Contacts with new people were measured using a five-item scale from EU Kids Online (Livingstone et al., Citation2011). Participants were asked how often (1 = Never to 5 = Daily or almost daily) during the preceding year they engaged in selected behaviors that represented various forms of contacts with unknown people on the internet (e.g., ‘Looked for new friends or contacts on the internet’). One item, ‘Pretended to be a different kind of person online from who I really am‘ had a low factor loading (.34). Because the item did not fit well content-wise with the other items (other items asked about direct contacts with unknown people), we excluded it from the analysis. The model without the item had satisfactory fit (RMSEA = .06 [90% CI = .02–.10], CFI = .98, TLI = .95, SRMR = .02, χ2 (2) = 8.77, p = .013) with factor loadings ranging from .54 to .69. The scale's reliability was acceptable (ω = .71, M = 1.57, SD = 0.59).

Risk perception

The scale consists of three items developed to measure adolescents’ perception of talking to unknown people on the internet (i.e., people that the respondents have never met in person), like ‘Talking to unknown people on the internet is dangerous’. The respondents answered how much they agreed with the statements on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = not at all, 4 = very). Since the scale consisted of only three items, model fit cannot be estimated. However, all items had sufficient factor loadings (β = .68–.82) and the scale's reliability was good (ω = .80, M = 2.41, SD = 0.84).

Results

To test the hypotheses, we used structural equation modeling in Mplus 8.6. Mediation strategies, risk perception, and contacts with new people were treated as latent variables. Age and gender were added as manifest variables and in the main model, all paths were controlled for their effect. Covariance coverage, which reflects the completeness of the data, ranged from .78 to .97. We used full information maximum likelihood to handle the missing data. To provide robust results, we used confidence intervals based on bootstrapping with 5000 samples. We present STDYX standardized coefficients.

First, we present correlations between variables (). Higher age and male gender were associated with lower active and restrictive mediation and lower risk perception. Being older was associated with more frequent contacts with new people online. Both active and restrictive mediation were related to higher risk perception and to lower contacts with new people.

Table 1. Correlations among the age, gender, and latent constructs.

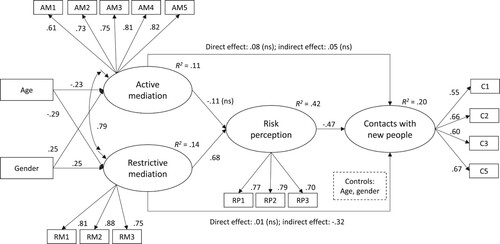

Next, we present the main results. The tested model had satisfactory fit: RMSEA = .05 (90% CI = .05–.06), CFI = .95, TLI = .94, SRMR = .04, although the chi-square was significant (χ2 (106) = 406.48, p < .001), likely due to the large sample size. The model is depicted in , and the full results are in .

Figure 1. Standardized results for the tested model.

Notes: All coefficients are significant on the p < .001 level (except the ones labeled ‘ns’). See Table 1 for exact p values, total effects, and the effects of control variables.

Table 2. Direct, indirect, and total effects on contacts with new people.

The results showed that age is negatively associated with both mediation strategies, which is consistent with H1a and H1b. In line with H2a and H2b, female adolescents also reported a higher frequency for both types of mediation.

Based on total effects, active mediation does not relate to contacts with new people (i.e., H3a was not supported). Restrictive mediation functioned in the expected way (H3b): adolescents who reported higher restrictions also reported less contacts. In line with H4, adolescents’ risk perception was negatively associated with contacts – adolescents who perceived the communication as riskier engaged less in this activity.

We also hypothesized an indirect effect for mediation strategies through the adolescents’ risk perception. This was supported only for restrictive mediation (H5b). Higher interaction restrictions were connected to lower interactions with new people through the increase of adolescents’ risk perception. The direct effect of restrictive mediation on contacts was not significant, suggesting that the effect of parental mediation was fully mediated by risk perception. For active mediation, both the direct and the indirect (H5a) effect were not significant.

Discussion

In this study, we were interested in active and restrictive parental mediations of online interactions – parenting strategies aiming to protect children (adolescents in our case) from risks that come with interacting online with other people (Livingstone & Helsper, Citation2008; Symons et al., Citation2019). Given the adolescents’ high usage of social media and other communication platforms (Smahel et al., Citation2020), and the related parental concerns (Steinfeld, Citation2021; Symons, Ponnet, Walrave, et al., Citation2017), this particular mediation represents an important area of examination. We hypothesized that parental mediation of interactions lowers adolescents’ online contacts with new people. Our data support this expectation when the mediation strategies are considered in bivariate associations with contacts, but when controlled for shared variance, the effect is apparent only for restrictive mediation. Moreover, our results support the notion that restrictive mediation impacts adolescents’ behavior by increasing their perception of how risky it is to communicate with new people online.

Predictors of parental mediation of interactions

In line with our hypotheses, parents’ mediation strategies differ based on adolescents’ age and gender. As adolescents age, they report less active and restrictive mediation of interaction. Such age effect is common in parental mediation studies on adolescents; it is assumed that parents respect their offspring's growing need for autonomy and privacy and that they also take into consideration their increasing skills and self-regulation (De Ayala López et al., Citation2020; Symons, Ponnet, Emmery, et al., Citation2017; Young & Tully, Citation2022). Specifically, in the case of parental mediation of interactions, we presume that parents also consider adolescents’ needs to develop close bonds with their peers (Collins & Steinberg, Citation2007). Online interactions, even with new people, provide adolescents with opportunities to find new friends and partners (Lykens et al., Citation2019). Hence, parents may lower their interaction mediation to allow their older children to reap this benefit.

Regarding gender, we found that girls reported more interaction mediation in both types. This might be connected to how the risk of interacting with others online is presented in the media, which is strongly gendered (Mýlek et al., Citation2021). The risk is usually described in terms of (potential) sexual abuse or solicitation, with males as the typical perpetrators and females as typical victims (Korkmazer et al., Citation2019). The study on unwanted sexual solicitation online shows that female adolescents and young women (14–29) face this contact risk more often than males in any age group and older or younger females (Baumgartner et al., Citation2010b). Thus, parents could be more concerned about their daughters than about their sons. However, in Keyzers’ (Citation2021) study, parental approval of online risky social interactions did not differ between male and female adolescents. Similarly, in a qualitative part of the study, Steinfeld (Citation2022) noted that parents often mentioned they realize boys can be victimized online just as girls. Yet, when they described their parenting, they still focused their mediation of interactions more on daughters because daughters were more inclined to engage in such interactions than sons. It thus seems that parents consider the severity of interaction risks as similar for both, but they see them as more likely to happen to girls.

We did not formulate a hypothesis related to adolescents’ gender and risk perception; however, our results show that girls perceived this risk as higher, which aligns with existing research (e.g., Baumgartner et al., Citation2010b). In our study, this association was not significant when other variables were controlled for. Specifically, parents engaged more in parental mediation of their daughters, which is why we did not see the effect of gender alone in the model. Following the argumentation in the previous paragraph, our risk perception measure mostly tapped into risk severity and not vulnerability (i.e., its perceived probability). Separating these two dimensions of risk perception (Reyna & Farley, Citation2006) might shed more light on gender differences in interaction risk perception.

Parental mediation and adolescents’ behavior

We expected both types of interaction mediation to be associated with lower adolescents’ contacts with new people. This was the case in bivariate associations, but active mediation of interactions was not related to adolescents’ contacts with new people in the full model – neither directly, nor indirectly. Such results are not uncommon in the studies on parental mediation that include both types in the same model and control for their shared variance (e.g., Shin & Lwin, Citation2017). It is possible that active mediation (without restrictions) does not affect the frequency of adolescents’ interactions with new people but rather more nuanced aspects of such interaction. For instance, discussions with parents may inspire the adolescent to more carefully select who to interact with or consider what content (i.e., photos, videos) they should or should not share. Our measure did not capture such preventative strategies nor adolescents’ social or digital skills. Yet, these could be the outcomes of active parental mediation. For instance, in a study on 12–17-year-old adolescents, active mediation was not connected to risky online self-disclosures but was positively associated with risk-coping behavior (Wisniewski et al., Citation2015). Notably, our measure also did not capture whether the interactions were harmful. Although contacts with new people from the internet are considered riskier than contacts with known people, this does not ultimately mean that such contacts lead to harm. It is possible that the effect of active mediation would be more pronounced in decreasing the actual harm rather than in decreasing the engagement in the activity.

Unlike active mediation, restrictive mediation was associated with lower contact with new people (i.e., total effect). Our findings also indicate that this effect occurs through increasing adolescents’ risk perception (i.e., indirect effect). As noted in the introduction, restrictive mediation can effectively lower risky activities but with undesirable side effects, including lower digital skills and fewer online opportunities (Livingstone et al., Citation2017; Rodríguez-de-Dios et al., Citation2018). Researchers point out that it is not possible to conclusively place interactions with new people online on the continuum between risk and opportunity, as this activity can be both (Smahel et al., Citation2020). Thus, the link between restrictions and lower engagement in this activity could be both reassuring (i.e., restrictive mediation decreases the risk) and worrying (i.e., it decreases the opportunities). Again, this is due to the way we measured contacts with new people in our study, which made it impossible to differentiate whether the activity was more risky or beneficial. Future research should approach this potential risk in more detail to allow for a deeper understanding of the effects of parental mediation.

The role of risk perception

Our study shows that risk perception can be essential in understanding parental mediation's effects. Our results suggest that the impact of parents’ restrictions on their children's online behavior is explained by the increase in the adolescents' risk perception. As such, risk perception represents one of the possible explanatory mechanisms of parental mediation, which could be considered in future research to enrich parental-mediation theory. Importantly, our results do not point to a similar mechanism in the case of active mediation. This goes against the results of Liu et al. (Citation2013), who found that both active and restrictive mediation increase adolescents’ privacy concerns, which in turn lower their personal information disclosure. However, the results are not directly comparable. While Liu et al. (Citation2013) analyzed the effects of active and restrictive mediation in two separate models, we included both in one. Thus, our model addresses the significant overlap between active and restrictive mediation and captures their unique effects. We found the same pattern in a study by Steinfeld (Citation2021), who found significant positive correlations between active and restrictive mediation and adolescents’ concerns. However, only restrictions were significant in a regression that included both mediation strategies as predictors of concerns.

These results suggest that discussions, explanations, and advice about security measures related to online interactions (i.e., active mediation) – when considered without the closely associated restrictions – do not relate to how risky adolescents perceive the activity to be. It is the restrictions that have substantial connection to risk perception. Presumably, when parents impose rules without discussing strategies to prevent potential harm, the child may think the harm is unavoidable, leading to higher risk perception. While this may decrease their online interactions, it also puts children in a difficult position when someone starts interacting with them. In a qualitative study (Cernikova et al., Citation2018), some children and adolescents (9–16 years old) reported reacting negatively to any initiation of contact from new people on the internet, even when the message was not bothersome. Therefore, excessive focus on restrictions may ultimately keep adolescents from taking advantage of the opportunities to form new social bonds online. Moreover, in the same study, when children received negative messages from someone online, some stayed passive and did not engage in any coping strategy (e.g., blocking the person), which might point to their lack of skills (Cernikova et al. Citation2018). Crucially, it is likely that children and adolescents who use the internet will (eventually) get in touch with new people there. Relying solely on restrictions does not equip adolescents with the knowledge needed to react actively and without unnecessary fear in such situations.

Though it was not the core focus of our study, our results also demonstrate that adolescents’ risk perception is a vital predictor of their participation in potentially risky online activities. This corroborates previous findings that the perceived risks predict sexting or meeting people from the internet in person (Baumgartner et al., Citation2010a; Mýlek et al., Citation2021). Nevertheless, despite these promising findings and the theoretical soundness of adolescents’ perception impacting their online social behavior, the research in this direction is limited. We thus encourage future research to consider the role of adolescents’ risk perception.

Limits

The study has several limits. Most importantly, we used cross-sectional data. Particularly, the link between adolescents’ behavior and the associated risk perception could be reversed (i.e., adolescents’ experience with the activity could affect how risky they perceive it). While such a direction theoretically makes good sense, this reverse relationship was not significant in the longitudinal study of risk perception as related to risky sexual behavior online (Baumgartner et al., Citation2010a). Moreover, studies show that interactions with new people often do not lead to harm (Smahel et al., Citation2020). Hence, if the relationship was reversed, such interactions would decrease the risk perception, which was not found in our study. Similarly, parental engagement in mediation could be an outcome rather than an antecedent of adolescents’ behavior. However, this does not correspond well to our results. It would mean that high restrictions lead to more contacts with new people, which might be the case for some adolescents (the ‘backfiring’ of mediation was reported previously, e.g., Nathanson, Citation2002), but we find it unlikely for the whole sample.

Conclusions

Our study showed that parents adjust their mediation of interaction to their adolescent children's gender and age and that restrictive mediation has a substantial association with their behavior. We also focused on adolescents’ risk perception as a potential mechanism that explains the impact of parental practices on children's behavior. This is an important theoretical addition to the parental-mediation literature. Online interactions with new people are ideal for testing our assumptions because of the generally high perception of this activity as risky (Mýlek et al., Citation2021). Consequently, adolescents likely view parental restrictions of online interactions as more legitimate and comply with them more often than restrictions of other activities where parents’ and children's concerns diverge (e.g., playing violent games; Kutner et al., Citation2008).

It is important to stress that active and restrictive mediation correlated strongly, which is in line with parents’ own reports of using mediation strategies (Steinfeld, Citation2021; Symons, Ponnet, Walrave, et al., Citation2017). The more parents engaged in one type of mediation, the more they engaged in the other. Our study investigated their unique effects on adolescents’ behavior and risk perception. This allowed us to understand better how different parenting practices function. Nevertheless, given their co-occurrence, the question arises about their combined effect. Hence, when researchers are interested in the effectiveness of parental mediation, we recommend a person-centered approach to the analysis and a focus on the combinations of different types of parental mediation (e.g., through latent profile analysis).

Supplement Material.docx

Download MS Word (14.7 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Lenka Dedkova

Lenka Dedkova, Ph.D. is a postdoc at Faculty of Social Studies, Masaryk University. Lenka’s research interests include the impact of children's and adolescents’ experiences with online interactions on their well-being, online parental mediation, and usable security [email: [email protected]].

Vojtěch Mýlek

Vojtěch Mýlek, M.A. is a doctoral student of social psychology at Faculty of Social Studies, Masaryk University. His research is focused on adolescents’ online communication and their social interactions with new people from the internet [email: [email protected]].

References

- Baumgartner, S. E., Valkenburg, P. M., & Peter, J. (2010a). Assessing causality in the relationship between adolescents’ risky sexual online behavior and their perceptions of this behavior. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39(10), 1226–1239. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-010-9512-y

- Baumgartner, S. E., Valkenburg, P. M., & Peter, J. (2010b). Unwanted online sexual solicitation and risky sexual online behavior across the lifespan. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 31(6), 439–447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2010.07.005

- Beyens, I., Keijsers, L., & Coyne, S. M. (2022). Social media, parenting, and well-being. Current Opinion in Psychology, 47, 101350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101350

- Borca, G., Bina, M., Keller, P. S., Gilbert, L. R., & Begotti, T. (2015). Internet use and developmental tasks: Adolescents’ point of view. Computers in Human Behavior, 52, 49–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.05.029

- Cabello-Hutt, T., Cabello, P., & Claro, M. (2018). Online opportunities and risks for children and adolescents: The role of digital skills, age, gender and parental mediation in Brazil. New Media and Society, 20(7), 2411–2431. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444817724168

- Cernikova, M., Dedkova, L., & Smahel, D. (2018). Youth interaction with online strangers: Experiences and reactions to unknown people on the Internet. Information, Communication & Society, 21(1), 94–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2016.1261169

- Chen, V. H. H., & Chng, G. S. (2016). Active and restrictive parental mediation over time: Effects on youths’ self-regulatory competencies and impulsivity. Computers and Education, 98, 206–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2016.03.012

- Collins, W. A., & Steinberg, L. (2007). Adolescent development in interpersonal context. In W. Damon, R. M. Lerner, & N. Eisenberg (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology (pp. 1003–1049). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470147658.chpsy0316.

- De Ayala López, M. C. L., Haddon, L., Catalina-García, B., & & Martínez-Pastor, E. (2020). The dilemmas of parental mediation: Continuities from parenting in general. Observatorio, 14(4), 119–134. https://doi.org/10.15847/obsOBS14420201636

- eSafety. (2019). Parenting in the digital age. eSafety Commissioner. https://www.esafety.gov.au/sites/default/files/2019-07/eSafety Research Parenting Digital Age.pdf

- Hayes, B., James, A., Barn, R., & Watling, D. (2022). “The world we live in now”: A qualitative investigation into parents’, teachers’, and children’s perceptions of social networking site use. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 92(1), 340–363. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12452

- Ho, S., Lwin, M. O., Chen, L., & Chen, M. (2020). Development and validation of a parental social media mediation scale across child and parent samples. Internet Research, 30(2), 677–694. https://doi.org/10.1108/INTR-02-2018-0061

- Ho, S., Lwin, M. O., Yee, A. Z. H., & Lee, E. W. J. (2017). Understanding factors associated with Singaporean adolescents’ intention to adopt privacy protection behavior using an extended theory of planned behavior. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 20(9), 572–579. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2017.0061

- Keyzers, A. (2021). Parental mediation and adolescent online social behavior [dissertation]. University of Minnesota. https://conservancy.umn.edu/handle/11299/224672.

- Korkmazer, B., Van Bauwel, S., & De Ridder, S. (2019). Who does not dare, is a pussy.” A textual analysis of media panics, youth, and sexting in print media. Observatorio, 13(1), 53–69. https://doi.org/10.15847/obsOBS13120191218

- Kuldas, S., Sargioti, A., Milosevic, T., & O’Higgins-Norman, J. (2021). A review and content validation of 10 measurement scales for parental mediation of children’s internet use. International Journal of Communication, 15, 4062–4084. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/issue/archive.

- Kutner, L. A., Olson, C. K., Warner, D. E., & Hertzog, S. M. (2008). Parents’ and sons’ perspectives on video game play: A qualitative study. Journal of Adolescent Research, 23(1), 76–96. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558407310721

- Liu, C., Ang, R. P., & Lwin, M. O. (2013). Cognitive, personality, and social factors associated with adolescents’ online personal information disclosure. Journal of Adolescence, 36(4), 629–638. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.03.016

- Livingstone, S., Haddon, L., Görzig, A., & Ólafsson, K. (2011). Risks and safety on the internet: The perspective of European children (p. 170). EU Kids Online, LSE. https://doi.org/10.2045/256X

- Livingstone, S., & Helsper, E. J. (2008). Parental mediation of children’s internet use. Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media, 52(4), 581–599. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838150802437396

- Livingstone, S., Ólafsson, K., Helsper, E. J., Lupiáñez-Villanueva, F., Veltri, G. A., & Folkvord, F. (2017). Maximizing opportunities and minimizing risks for children online: The role of digital skills in emerging strategies of parental mediation. Journal of Communication, 67(1), 82–105. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12277

- Lykens, J., Pilloton, M., Silva, C., Schlamm, E., Wilburn, K., & Pence, E. (2019). Google for sexual relationships: Mixed-methods study on digital flirting and online dating among adolescent youth and young adults. JMIR Public Health and Surveillance, 5(2), e10695. https://doi.org/10.2196/10695

- Mýlek, V., Dedkova, L., & Smahel, D. (2021). Information sources about face-to-face meetings with people from the Internet: Gendered influence on adolescents’ risk perception and behavior. New Media & Society. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448211014823.

- Nathanson, A. I. (2002). The unintended effects of parental mediation of television on adolescents. Media Psychology, 4(3), 207–230. https://doi.org/10.1207/S1532785XMEP0403_01

- Nielsen, P., Favez, N., Liddle, H., & Rigter, H. (2019). Linking parental mediation practices to adolescents’ problematic online screen use: A systematic literature review. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 8(4), 649–663. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.8.2019.61

- Nikken, P., & Jansz, J. (2014). Developing scales to measure parental mediation of young children’s internet use. Learning, Media and Technology, 31(2), 181–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2013.782038

- Padilla-Walker, L. M., Coyne, S. M., Fraser, A. M., Dyer, W. J., & Yorgason, J. B. (2012). Parents and adolescents growing up in the digital age: Latent growth curve analysis of proactive media monitoring. Journal of Adolescence, 35(5), 1153–1165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.03.005

- Paluckaitė, U., & Žardeckaitė-Matulaitienė, K. (2021). Adolescents’ intention and willingness to engage in risky photo disclosure on social networking sites: Testing the prototype willingness model. Cyberpsychology, 15(2), 2. https://doi.org/10.5817/CP2021-2-1

- Reyna, V. F., & Farley, F. (2006). Risk and rationality in adolescent decision making. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 7(1), 1–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1529-1006.2006.00026.x

- Rodríguez-de-Dios, I., van Oosten, J. M. F., & Igartua, J. J. (2018). A study of the relationship between parental mediation and adolescents’ digital skills, online risks and online opportunities. Computers in Human Behavior, 82, 186–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.01.012

- Shin, W. (2015). Parental socialization of children’s Internet use: A qualitative approach. New Media & Society, 17(5), 649–665. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444813516833

- Shin, W., & Huh, J. (2011). Parental mediation of teenagers’ video game playing: Antecedents and consequences. New Media and Society, 13(6), 945–962. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444810388025

- Shin, W., & Ismail, N. (2014). Exploring the role of parents and peers in young adolescents’ risk taking on social networking sites. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 17(9), 578–583. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2014.0095

- Shin, W., & Kang, H. (2016). Adolescents’ privacy concerns and information disclosure online: The role of parents and the Internet. Computers in Human Behavior, 54, 114–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.07.062

- Shin, W., & Lwin, M. O. (2017). How does “talking about the Internet with others” affect teenagers’ experience of online risks? The role of active mediation by parents, peers, and school teachers. New Media and Society, 19(7), 1109–1126. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444815626612.

- Smahel, D., Machackova, H., Mascheroni, G., Dedkova, L., Staksrud, E., Ólafsson, K., Livingstone, S., & Hasebrink, U. (2020). EU kids online 2020: Survey results from 19 countries. EU Kids Online, LSE. https://doi.org/10.21953/lse.47fdeqj01ofo.

- Soh, P. C. H., Chew, K. W., Koay, K. Y., & Ang, P. H. (2018). Parents vs peers’ influence on teenagers’ Internet addiction and risky online activities. Telematics and Informatics, 35(1), 225–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2017.11.003

- Steinfeld, N. (2021). Parental mediation of adolescent Internet use: Combining strategies to promote awareness, autonomy and self-regulation in preparing youth for life on the web. Education and Information Technologies, 26(2), 1897–1920. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-020-10342-w

- Steinfeld, N. (2022). Adolescent gender differences in internet safety education. Feminist Media Studies. Advanced online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2022.2027494

- Symons, K., Ponnet, K., Emmery, K., Walrave, M., & Heirman, W. (2017). A factorial validation of parental mediation strategies with regard to internet use. Psychologica Belgica, 57(2), 93–111. https://doi.org/10.5334/pb.372

- Symons, K., Ponnet, K., Walrave, M., & Heirman, W. (2017). A qualitative study into parental mediation of adolescents’ internet use. Computers in Human Behavior, 73, 423–432. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.04.004

- Symons, K., Vanwesenbeeck, I., Walrave, M., Van Ouytsel, J., & Ponnet, K. (2019). Parents’ concerns over internet use, their engagement in interaction restrictions, and adolescents’ behavior on social networking sites. Youth and Society, 52(8), 1569–1581. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X19834769.

- White, C. M., Gummerum, M., & Hanoch, Y. (2015). Adolescents’ and young adults’ online risk taking: The role of gist and verbatim representations. Risk Analysis, 35(8), 1407–1422. https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.12369

- Wisniewski, P., Jia, H., Xu, H., Rosson, M. B., & Carroll, J. M. (2015, March 14-18). Preventative vs. reactive: How parental mediation influences teens’ social media privacy behaviors. CSCW 2015 – Proceedings of the 2015 ACM International Conference on Computer-Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing (pp. 302–316). Vancouver. https://doi.org/10.1145/2675133.2675293.

- Young, R., & Tully, M. (2022). Autonomy vs. control: Associations among parental mediation, perceived parenting styles, and U. S. adolescents’ risky online experiences. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 16(2), 2, Article 5. https://doi.org/10.5817/CP2022-2-5.

Appendix: Items

Parental mediation of interactions

How much do the following statements apply to your parents? If it is difficult for you to choose the answer for both of them together, answer with respect to the parent you are closer to.

Answers: 5-point scale from (1) Never to (5) Very often

AM1: [Parents] talk to me about who I’m talking to on the internet

RM1: [Parents] don't allow me to have people that I don't know personally in my friend list on social media

AM2: [Parents] explain to me how to have a secure profile on a social network

RM2: [Parents] forbid me to talk on the internet with people I don't know personally

AM3: [Parents] talk to me about meeting unknown people from the internet in person

AM4: [Parents] explain to me when it's okay to send photos to the other people online

AM5: [Parents] advise me what information about myself I can share on the internet with people I don't know

RM3: [Parents] forbid me to meet people from the internet in person

Note: AM = active mediation, RM: restrictive mediation

Contacts with new people

How often have you done the following things on the internet in the LAST YEAR?

Answers: 5-point scale from (1) Never to (5) Daily or almost daily

C1: Looked for new friends or contacts on the internet

C2: Sent my personal information (e.g., my full name, address, phone number) to someone I have never met face-to-face

C3: Added people to my friends or contacts I have never met face-to-face

C4: Pretended to be a different kind of person online from who I really am (omitted)

C5: Sent a photo or video of myself to someone I have never met face-to-face

Adolescents’ risk perception regarding interactions with new people online

The next questions are about what you think about talking to unknown people on the internet. By this we mean a situation where you meet someone new on the internet whom you did not know before and you write to them via the internet (e.g., messenger).

For each statement, tick how much it applies to you.

Answers: 4-point scale with responses (1) not at all, (2) a bit, (3) fairly, and (4) very

RP1: Talking with unknown people on the internet is dangerous

RP2: Nothing good can come from talking with someone unknown on the internet

RP3: If my friend was talking to someone unknown on the internet, I would be worried about them