ABSTRACT

An emerging activist tactic on visual-based social media such as Instagram, slideshow activism adapts the production and consumption of political information to the logic of the platform. In so doing, slideshow activism provides followers with an ideal subject position for civic engagement. By examining a popular slideshow activist Instagram account, we outline the features of this activist tactic and its mobilizing appeal. The qualitative content analysis of a sample of 50 posts reveals that slideshow activism addresses its followers as individuals who are actively staying well-informed on the social justice dimension of a wide range of political issues and are constantly engaged in self-transformation in order to become better citizens. This ideal, we argue, entrenches social justice as a core political value for civic engagement, and recommends a mix of argumentation and personal transformation as the everyday means for individuals to bring about political change. We further explore the consequences of this subject position for citizen engagement with politics.

Introduction: what is slideshow activism?

A popular visual and rhetorical political tactic, slideshow activism is found on image-based social media platforms such as Instagram. Recognizable as PowerPoint-style presentations on a given issue or cause, slideshow activism consists of a succession of several slides (photographs), also known as a ‘carousel’ post, that include short texts and visual elements made available via social media accounts. We approach slideshow activism as an emerging visual template (Leaver et al., Citation2020), designed to be both accessible and spreadable.

While limited academic work has considered slideshow activism as a vehicle for civic engagement (Ledford & Salzano, Citation2022; Salzano, Citation2021), this activist tactic has received attention within popular news media due to its widespread usage, particularly in the summer of 2020 when there was a resurgence of support for the Black Lives Matter movement (Nguyen, Citation2020; Smith, Citation2021). Like related content such as the ‘digital political infographic’ (Amit-Danhi & Shifman, Citation2018), activist slideshows condense complex political issues into accessible and easily shareable visualizations, offering ‘new ways of discussing and understanding politics’ (p. 3531). However, unlike digital political infographics, slideshows break down a larger narrative into smaller bites, offering step-by-step support in a sequential manner. Slideshow activism also overlaps with information activism, defined as a stated aim to use one’s social media following in order to ‘push for genuine political change’ (Halupka, Citation2016, p. 1495). While forms of information activism may be present whenever individuals gather and share politically relevant information that is personally relevant to them, slideshow activism takes this a step forward as a specific subgenre for the presentation of this information in a way that is conducive to shareability. In this sense, slideshow activism also functions as an alternative media tailored to the affordances of social media platforms. Finally, while slideshow activist accounts can garner a great deal of visibility and engagement online, the account author(s) are not always made visible to users. In this sense, slideshow activist accounts can be quasi-anonymous and highly depersonalized, thus following a broader trend in digitally mediated activism whereby the structure and identity of leadership is obfuscated (Bakardjieva, Felt, & Dumitrica, Citation2018).

Focusing on the most popular slideshow activism Instagram account, we ask how their use of slideshow activism constructs the political activist subject; and, which political values are emphasized in this process. Given the limited scholarly discussion, we offer an exploratory analysis of how the format and function of this account’s slideshow activism spurs civic engagement, adding to scholarship interested in the re-appropriation of digital technologies for political participation (George & Leidner, Citation2019; Milan & Barbosa, Citation2020). By means of a qualitative content analysis of a random sample of 50 Instagram slideshows posted by this account, we offer a snapshot of the account’s use of slideshow activism as an activist tactic, a strategy for civic engagement, and a digital subgenre. This case study cannot be used to make generalizations about all slideshow activist accounts. However, it does suggest that the popular formula of slideshow activism developed by this account (where success is understood in terms of Instagram popularity) reproduces the individualization of activism and civic participation associated with digital activism. We reflect on the implications for the development of the wider civic culture, shaped by new media, within which people ‘develop into citizens’ (Dahlgren, Citation2005, p. 158).

The subject position and its role in civic culture

We approach the subject position (re)produced by slideshow activism as part and parcel of the wider civic culture within which individuals come ‘to see themselves as actors who can make meaningful interventions in relevant political issues’ (Dahlgren, Citation2013, p. 24). From a discursive perspective, the social structure within which individuals are located provides them with specific vocabularies, roles, and templates for interaction that legitimize them as actants. Foucault’s (Citation1982) work considers how discipline-specific discourses such as medicine or education open up subject positions from within which individuals can speak authoritatively. He argues that far from being (solely) the result of inner cognitive and emotional processes, individuals are ‘produced by a pre-existing system of power-relations’ (Heller, Citation1996, p. 91).

Drawing attention to the mechanisms through which power becomes constructed, exercised, legitimized, but also resisted, the idea of subject positions plays upon the ambiguity of the notion of the subject: an agent making their own choices (i.e., the subject), but also an object upon which power acts (i.e., being subjected to). Discursive practices have a disciplinary dimension to them: they provide vocabularies and practices that the individual is asked to internalize in order to turn herself into a ‘good’ citizen (Kligler-Vilenchik, Citation2017). In a different area of his work, Foucault referred to this process as ‘technologies of the self’ – recipes through which individuals engage in ‘an exercise of self upon self by which one tries to work out, to transform one’s self and to attain a certain mode of being’ (Fornet-Betancourt et al., Citation1987, p. 1113). While modern forms of power are premised on asking individuals to self-discipline by working upon their own selves, different relations of power co-exist and, as such ‘different discourses construct different subject-positions’ (Heller, Citation1996, p. 93) suggesting that subjectification remains ‘a heterogeneous process’ (ibid.: 94).

We approach Account A’s use of slideshow activism as a discursive practice providing, not just a vocabulary for ‘being politically active’, but also easy-to-use instructions for what citizens can do to act politically. Given the Instagram metrics of this Account (over 3 million followers as of September 2022, making it the most popular slideshow activism account), we argue its use of slideshow activism remains ground-breaking and thus likely to be emulated by accounts seeking to boost their followings. We further consider the subject position of slideshow activism as a ‘mode of action upon the actions of others’ (Foucault Citation1982, p. 790), as well as a pushback against political elites and larger discussions of the ‘worth’ of digital activism.

Digital activism and the engaged citizen

An ambiguous term, ‘digital activism’ refers to the usage of digital media for political purposes (Gerbaudo, Citation2017; Kaun & Uldam, Citation2018). Joyce (Citation2010, p. 2) defines digital activism as a form of practice, suggesting that reliance on and integration of digital technologies in activism has become habitual. Yet, questions still remain regarding the forms of agency that citizens may have vis-à-vis the technological infrastructure, the role of the wider context (e.g., economic, cultural, political factors) within which digital activism unfolds, the relationship between digital and other forms of mediation, and the value or impact of digital activism (Chadwick, Citation2013; Joyce, Citation2010; Treré, Citation2019).

While a review of these debates falls outside the scope of this paper, this section zooms in on aspects within these debates that shed light on how a particular image of the ‘good citizen’ is constructed via digital activism. The case of slideshow activism discussed here constitutes an example of creative reappropriation of a profit-oriented social media platform (i.e., Instagram) for civic purposes (Gordon & Mihailidis, Citation2016; McFarland, Citation2010). Through its affordances and practices of use, platforms develop their own ‘vernaculars’ (Gibbs, Meese, Arnold, Nansen, & Carter, Citation2015). This leads to the development and subsequent normalization of ‘numerous tropes, templates and clichés’ (Leaver et al., Citation2020, p. 72) that push for standardization of content. On the other hand, this also spurs ‘vernacular creativity’ (Burgess, Citation2006), with users recombining existing affordances and practices to generate new and thus potentially striking content. Slideshow activism is a good example of this tension between templatability and vernacular creativity as it blends existing Instagram stories’ ‘aesthetics for presenting quotes, thoughts and other content that has no image of video’ (Leaver et al., Citation2020, p. 60) with an activist purpose (on a platform traditionally known for selfies and the recording of mundanity).

While such moments of creative reappropriation speak of user agency, this does not necessarily result in enhanced political agency. The exclusive reliance on Instagram, for instance, also subjects the activist account to the ebbs and flows of algorithmically afforded visibility. Consequently, the politics of visibility that social media platforms enact (for instance, by making particular type of contents visible to its audiences) deepen the wider phenomenon of individualization of citizenship (Milan, Citation2015). By foregrounding the individual as an organizing principle, social media platforms work against the recognition that a collective ‘we’ is a prerequisite of collective civic action. Collective action thus comes to be experienced as a ‘performance and expression of the “I”, partially losing the representative function of the “we”’ (Milan, Citation2015, p. 896). Similarly, Milan and Barbosa argued that WhatsApp ‘supports the emergence of a new political subject’ marked by individualized action within the personal network, as well as explicit and constant use of the platform for political purposes (Citation2020, np). Bakardjieva and colleagues (Citation2018) echo this when suggesting that discourses around digital activism (as evidenced by news coverage of digitally mediated forms of collective action) further personalize the act of political engagement and cast engagement as ‘a personal decision and action that is amplified – and thus empowered – by social media’s capacity to aggregate it with similar (individual) interests and actions’ (p. 833).

The personalization of engagement remains deeply ambivalent. On the one hand, digital technologies provide new channels for participation. Yet, this participation is less about ‘duty and virtue’ and more about ‘personal interest, care, and self-actualization’ (Dalton in Gordon & Mihailidis, Citation2016, p. 2). On the other hand, the destabilizing impact of atomization on political participation may be offset by the affordances of digital technologies (and social networking sites in particular). Castells’ (Citation2004) model of the network society is premised on the idea that the ‘logic, and organization, of electronic media frame and structure politics’ (p. 370). While pinpointing the exact logic/ organization of digital technologies remains difficult, Castells highlights decentralization and networking as simultaneously furthering individualization and enabling the rise of new flows of power that bypass traditional institutions (from the nation-state to traditional media or political parties). Similarly, in their model of connective action, Bennett and Segerberg (Citation2013) contend that the communication enabled by networks of connected individuals enables the emergence of new forms of political organization. Digital networks, then, promise to offset the civic limits of individualization.

Whether this happens – and how – remains open to debate. Empirical cases suggest that collective identity and leadership remain crucial ingredients to the ability of mobilizing citizens to participate in collective action (Bakardjieva et al., Citation2018). Yet, being an engaged citizen can take many forms beyond participation in protests or other forms of contentious, collective action. Digital technologies can enhance the repertoire of possible political action for citizens. While these actions also entail different costs for the citizen performing them (Van Laer & Van Aelst, Citation2010), they should never be regarded as insignificant in terms of their contributions to symbolically constructing a civic orientation. Digital technologies multiply the possibilities for creative practices of citizenship: ‘the Internet transforms the process of identification by exploding the number of discourses and subject positions to which the individual becomes exposed, as well as by multiplying the forms of participation available at that individual’s fingertips’ (Bakardjieva, Citation2009, p. 94). Instead of the rational actor of classical models of citizenship (where individuals engage in debates to reach informed decisions), Bakardjieva recovers the forms of sub-activism that digital technologies enable: ‘feeble motions immersed in the everyday many times removed from the hot arena of politics’ (Citation2009, p. 103).

Such arguments raise the thorny issue of the value or impact of digital activism – and, by extension, of the civic subject position that it articulates. On a theoretical level, digital activism is confronted with an ontological limitation derived from the overarching profit-making goal of the most popular digital platforms within which it unfolds, as well as from these platforms participation in oft-forgotten forms of media imperialism. For social justice activism in particular, these dimensions mean that, at a fundamental level, the fight for an equitable society comes to generate value for the capitalist system and to establish the geopolitical dominance of specific countries (Aouragh & Chakravartty, Citation2016; Gehl, Citation2015). While social media users are invited to co-create and share their voice (understood primarily as personal preferences and stories), their personal data – but also their attention, an increasingly valuable commodity (Tufekci, Citation2013), become the resource that big tech companies exploit.

Perhaps more visible to citizens themselves is the question of the impact of digital activism, where the image of the engaged citizen morphs into that of the lazy slacktivist, who performs impulsive, low-cost actions in response to the ever shifting of the causes of the day. Rooted in traditional political science models, this view values engagement with formal politics (e.g., voting, political party membership, writing to elected officials, etc.) over acts of self-expression (e.g., displaying your political support through a badge or bumper sticker, talking to others about politics, etc.). The prominence of the latter is often taken as a sign of the dissolution of the very fabric of the polis. Indeed, slacktivism is seen as undermining real political engagement by reducing the civic subject to reactive and non-committal gestures (Halupka, Citation2014). At play here is the question of what exactly the plurality of exclusively digital forms of activism (e.g., online petitions, hashtag activism, etc.) does vis-à-vis political power (Christensen, Citation2011). Assessing the value of digital acts with a political undertone – such as changing one’s Facebook profile picture in support for a cause; or, re-posting a political meme – can be difficult, for such acts may not immediately prompt political change. Yet, they can nonetheless drive it by activating users into citizens, raising awareness on difficult issues, generating support for causes, and so on (Madison & Klang, Citation2020).

These debates sensitize us to the delicate balance between the benefits and limitations of digitally mediated engagement. Slideshow activism – we acknowledge – is only one digitally-enabled activist tactic in a larger media ecosystem, coexisting with other forms of activist intervention. From this theoretical standpoint, we thus ask what civic values, norms, and practices our chosen case study encourages, and how these construct a citizenship imaginary.

Methodology

The empirical data for this paper comes from (to our knowledge) the most popular slideshow activist account on Instagram in terms of followers (over three million as of September 2022). The account itself is public and the about description lists a name. However, in line with debates about the ethical research in online contexts, we anonymized it (Gerrard, Citation2020; Markham, Citation2012). This decision was strengthened by the lack of response to our efforts of contacting the account holder for the purposes of a research interview. The project also received approval from the ethics boards of the authors’ respective faculties.

The Instagram account (Account A) was set up in 2020 as exclusively dedicated to slideshow activism with an explicitly stated social justice purpose. The account posts regularly on issues related to the US political context, with over 1000 posts to date. To understand how the slideshows construct the idea of a ‘good citizen’, we sampled every 10th post from the account’s feed, starting from Account A’s first post to the most recent. Sampling every 10 posts allowed us to span the entirety of Account A’s content, meaning we would be able to trace changes in the slideshow’s format and content across time. This sampling strategy led to a sample of 50 different slideshows (at the time of data collection Account A had approximately 500 posts) for the period February 2020 to February 2021. Slideshow posts in our sample had an average of 8.8 slides.

Posts were analyzed by means of a content analysis using a coding frame informed by several theoretical models on framing activist communication (Benford & Snow, Citation2000); social media NGO communication (Lovejoy & Saxton, Citation2012); and the Foucauldian framework of subject position and technologies of self. The use of a coding frame – a list of overarching topics that were operationalized into yes/no and list questions – allowed us to map the frequency of certain elements across the data while also paying attention to qualitative aspects of meaning-making.

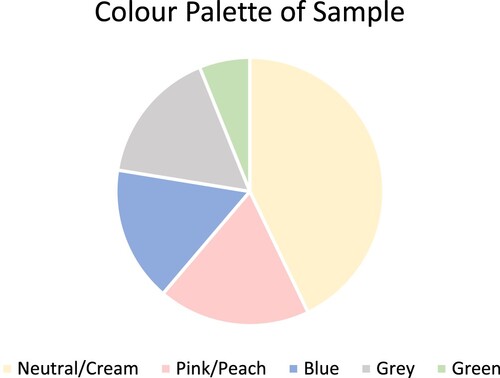

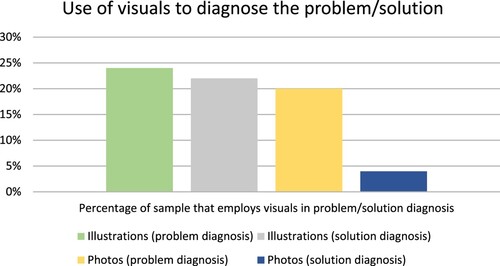

Frames are discursive mechanisms of selection and emphasis. In the context of social movements, frames are essential to building a sense of collective identity based on shared understandings of the problem and its moral evaluation, as well as the solution. Given Account A’s work as an activist communicator on social justice issues, the coding frame included three overarching categories: problem diagnostic (what is the issue); prognosis (what is the solution); and motivation (why someone should join or support the cause) (Snow & Benford, Citation1988). This was further supplemented by incorporating the functions of social media posts for nonprofit communication developed by Lovejoy and Saxton (Citation2012), namely: inform, mobilize, educate, and build community. Finally, the Foucauldian framework was operationalized by paying attention to the mode of address (direct/ indirect; I/ we) and the presence/ absence of specific instructions for how the individuals should act. Finally, given our interest in slideshow activism as an activist tactic, we added formatting aspects pertaining to the visual composition of the slides in order to capture aesthetic patterns across the sample. These included the presence/absence of visual tools (photographs/illustrations/anything that stands out) as well as Account A’s color palette.

The resulting coding frame () was calibrated among the two researchers and their research assistant; this led to further specifying the categories in the coding frame. Following this, the research assistant coded the remaining sample, sharing the mid-way and the final results with the researchers.

Table 1. Coding frame.

Findings

The formula of slideshow activism

Despite operating on a social media platform that adheres to a capitalist for-profit model (Gehl, Citation2015), the activist account under study here has a strict non-profit identity. Followers are reminded of this whenever the account recommends fundraising initiatives or whenever followers themselves express a desire to contribute to the page financially. This stands in stark contrast with the image of Instagram as a marketplace, driven primarily by the commercialization of the personal (Leaver et al., Citation2020). In this sense, the account’s stated activist goal is an instance of vernacular creativity tapping into the platform’s popularity and re-purposing its aesthetic in order to contribute to social transformation.

Content-wise, Account A covers formal politics (e.g., party politics, institutions, activists and current events that are somewhat specific to North America) but presents it in a way that capitalizes upon the existing practices and expectations of Instagram users. Indeed, the account transforms politics into a topic ‘for the gram’, re-appropriating influencer marketing techniques such as producing digital content with an eye to brand coherence, disclosing partnerships, original content, and attention to the use of hashtags (Leaver et al., Citation2020). This is enhanced by the fact that the account responds to the news of the day. For instance, our sample shows the political importance of the electoral year across the topics tackled by the account, with several slideshows filtering electoral issues through an activist and social justice-oriented lens.

Indeed, based on previously published media interviews, Account A is run by an individual with communication and marketing skills. Where influencers rely on the power of ‘multi-influencer campaigns’ to boost visibility of a post (Leaver et al., Citation2020), Account A resorts to regular contributions and collaborations with non-profit organizations and activist groups, crowdsourcing the slideshows to some degree. In a way reminiscent of the disclosure practices of influencers, collaborators but also sources of information for the material used in the slideshow are visibly credited at the bottom of the slides and linked in the caption.

The overall argumentative structure and aesthetic of Account A’s slideshows is consistent and rarely deviates from its format. The argumentative layer of the slideshows emerges as carefully crafted, typically following the format: problem definition → provision of factual support→solution and/or call for action. This recipe echoes the deliberative communicative action model, where ‘in argument or discourse, participants contest and respond to validity claims’ (Johnson, Citation1991: 192).

The account provides information and reasons in support of statements made on a topic – but that can also help readers justify their own position on this topic. Each slideshow has a title page announcing the topic and the account’s logo beneath. Problem definition consists of first stating the topic or the issue, then explaining its significance (with 90% of slideshows in our sample providing an explicit reason why the issue/topic of the slideshow matters). Interestingly, in more than half of the sample, problem definition often frames the source of the issue/ cause as systemic, generally avoiding blame-placing on specific individuals or institutions. Yet, on occasion, Account A nominates activist icons such as Bernie Sanders as well as political enemies such as Donald Trump.

The following slides provide further context and evidence. Here, great care is exercised in sourcing the material presented and visually emphasizing the most striking information supporting or further clarifying the problem definition. For example, 54% of the posts in our sample used statistical data from formal national and international institutions (e.g., White House, the World Health Organization, the United Nations), media institutions (e.g., The Washington Post, National Geographic, The Guardian), and civil society organizations (e.g., Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network, Homelessness Law Center, Green America). In 40% of the posts, quotes were preferred. In some cases, politicians such as Joe Biden and Bernie Sanders, or famous people associated with social justice causes like Colin Kaepernick and James Baldwin were quoted. In other cases, news articles from sources such as Forbes, Scientific American, The Independent or CNN were used. Overall, the attention to sourcing suggests a conscious effort to signal transparency while also building credibility in argumentation.

The final slides provide a solution (74% of our sample), with some outlining further action followers could take to address the issue at hand (58% of our sample). This argumentative structure recalls the strategic communication recipes leveraging the features of social media for nonprofits and activists: information provision and calls for action (Lovejoy & Saxton, Citation2012). The community building function, however, is missing at the level of content: when interpellated, readers are usually addressed as ‘you’ and there is generally little evidence of explicit discursive efforts to build a collective ‘we’. Indeed, Account A can be understood as a ‘professional activist’ rather than an ‘issue-based activist’ with an interest in social justice causes at large.

Aesthetically, the account employs a pastel color scheme with minimalist visuals (see ). This color scheme reflects Instagram’s visual presentation practices drawing on ‘exaggeratedly feminine, pastel-laden aesthetic’ (Bracewell, Citation2021: 2) in order to communicate a political message. Somewhat strikingly, given Instagram’s reputation as a visual based platform, is the relative lack of images in problem diagnosis or problem-solving (see ). Slideshow activism thus builds on the earlier format of Instagram stories that recovered textual-based interventions on an overwhelmingly visual platform (Leaver et al., Citation2020, p. 60). In this sense, we can understand slideshow activism as a creative reappropriation of Instagram’s visual logic in service of raising awareness for social justice discourse.

Next, we discuss Account A’s construction of the political activist subject in relation to three key themes that emerged from the analysis and which can be simplified to form the following statement:

Account’s A slideshow activism constructs the ideal political activist subject as an individual who is well-informed on a wide range of issues and ongoingly works on themselves in order to become a better citizen.

The political subject as an individual

Unlike other forms of activist communication that focus on community-building, Account A directly address an individual in 44% of the posts, and asks for a change within the individual (behavioral, attitudinal, or cognitive) such as things to say, do, or practice with (e.g., learn more about electoral platforms, challenge your beliefs, etc.) in 42% of the posts.

When the plural ‘we’ is used (30% of the sample), the account tends to shift between different types of imagined collectivities. Given the Account’s embeddedness within US politics, it is not surprising that several posts address the national ‘we’, drawing attention to the problems relevant to or explicitly referring to the American public opinion. The national ‘we’ is also signaled by the sources of information quoted in the slides, by the organizations mentioned or partnered up with, as well as by the overwhelming reference to US political actors and institutions. Only in very few cases do these elements evoke a seemingly international (albeit Western-centric) audience. For example, one slideshow discusses depression as a state ‘we all experience’. This slideshow sources support from the World Health Organization, as well as a US-based scholar, and provides the phone numbers of crisis helplines from Germany, Canada, US, Australia, and Mexico.

The emphasis on the individual is mirrored in the attention that Account A devotes to political figures. For example, both political idols such as Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez or Deb Haaland and political foes such as Donald Trump or Harvey Weinstein are nominated and unambiguously profiled as either ‘good’ or ‘bad’. Moreover, Account A often advocates for individual-centered forms of action, highlighting what people can do in their everyday lives, rather than that which is explicitly collective. For instance, a slideshow devoted to LGBTQIA + allyship is first introduced by highlighting the need for allies to express their support in the minutia of everyday life – and not just on celebratory occasions. Explicitly distinguishing between superficial and real support, the Account explains that being an ally is not simply about sharing your photographs from Pride Parade on social media but rather entails a process of self-awareness and self-challenge. Across this slideshow, an ally is an individual who listens to those who are directly marginalized/oppressed for their sexual orientation.

The account addresses followers primarily as individuals who can, on the one hand, improve their own knowledge, and, on the other, contribute to the dissemination of these activist messages as a means of creating social change. This echoes larger discussions on the personalization of politics and the personalization of engagement, where ‘each individual is required to ‘invent themselves’, to shape and form who they are and what they believe in –including how to enact their citizenship’ (Kligler-Vilenchik, Citation2017, p. 1892). While the lack of community building through slideshows is, in our view, likely linked to the general social justice orientation of Account A – as opposed to issue-specific forms of activism – it nonetheless interpellates the reader as an individual whose job is to work upon their own views and actions.

The political subject as well-informed

As an ‘information activist’ (Halupka, Citation2016), Account A condenses and editorializes topics into accessible and succinct ‘cheat sheets’ allowing readers to stay up to date with political developments (primarily in the US) and social justice causes. In this regard, slideshow’s function much like Amit-Danhi and Shifman’s (Citation2018) ‘digital political infographic’ in that they seek to condense complex political issues into accessible and easily comprehensible visualizations, providing followers with a carefully framed argument, as well as the necessary evidence they might need to argue for/against a specific position.

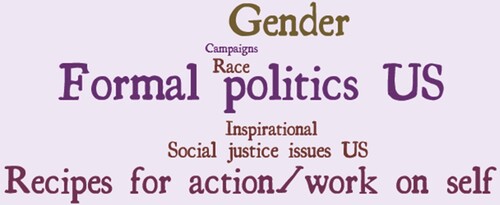

Account A covers a wide array of topics which can broadly be categorized as; explainers/cheat sheets of specific issues (82%); profiling individuals/ institutions (32%), and editorialization of current affairs (52%). Most posts in our sample deal with aspects of formal politics in the US, also reflecting the electoral context of the sampling period. Next to this, gender-related issues and specific recommendations for action and for work upon the self are tackled ().

The ideal reader of these slideshows is thus enticed to stay abreast of current developments in party politics as well as more chronic and systemic political issues/causes (for example, LGBTQI + issues and gender/racial inequality). In the case examined here, slideshow activism editorializes topics already salient in current public debate, providing its followers support for a particular position. In so doing, the slideshows promote particular interpretative frames, working to ‘diagnose a problem or issue, evaluate possible causes of the problem, and prescribe actions deemed appropriate for resolving the issue’ (Ofori-Parku & Moscato, Citation2018, p. 2484), which in turn helps social actors interpret these phenomena.

The logic behind slideshow activism as an activist strategy, as stated by Account A, is that when individuals are better informed, they are more likely to take action. For the informed citizen who feels daunted by the overabundance of information online (Thorson, Citation2012), the slideshows provide a quick and easy to use rolodex of support (e.g., quotes, statistics) for inserting oneself in the political debate. This ideal political subject is reminiscent of the ‘good citizen’ of deliberative models of democracy, with individuals engaged in rational debate, able to explain their positions and their underpinning reasons (Kligler-Vilenchik, Citation2017). Similarly, slideshow activism addresses its readers as seeking information while unambiguously occupying a political position (i.e., pro social justice) on a range of issues.

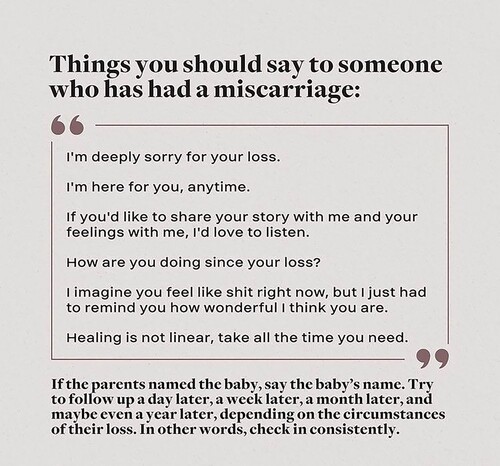

Importantly, the ideal political subject, as constructed by Account A, is already interested in and oriented towards social justice. In that sense, social justice becomes the fundamental value of citizenship, with citizens subsequently working on themselves in order to improve both their understanding of the sociopolitical world and their own actions from this normative standpoint. Take for instance a highly personal (yet often taboo) issue like miscarriage. A slideshow devoted to this topic starts by first defining and contextualizing it statistics and medical information. Then, it delves into why and how miscarriage has been socially stigmatized, further arguing this stigmatization hurts people (and using statistics to support this point). The post concludes with advice on how individuals should act and what they should say to those who had a miscarriage (see ). This advice includes set first-person statements that are offered as appropriate for dealing with the grief miscarriage entails. By tackling such diverse topics from the perspective of social justice, Account A constructs the ideal political subject as someone who, while staying abreast of current events, believes the personal is political and acts accordingly in all aspects of social life.

Moreover, the absence of constructive debate and dissent is a characteristic of Account A’s communicative style that acts as further evidence for their audience having an existing pro-social justice orientation. While Account A emphasizes in its slideshows the importance of ‘listening and learning’, critical dialogue (via the comments section below posts or elsewhere) on the issues tackled by the account is seldom encouraged or even mentioned. In this respect, Account A provides information and evidence, rather than engaging in a dialogue with individuals who hold opposing views. This is not to say Account A is not responsive to their audience; to the contrary, the account would often redact or update information they had provided in response to suggestions by their followers. However, the underpinning progressive social justice framing of the issues and causes covered by the account is not up for debate. In turn, this creates an implicit ‘we’ among the readers/ followers, who are already assumed to care about these issues.

Technologies of the self in slideshow activism

A recurring theme that emerged from the content analysis was the emphasis on ‘working on the self’ as a solution to many of the problems outlined by Account A’s slideshows. While 58% of posts in our sample required some form of action on behalf of the reader, the vast majority of them (72%) advocate for action that requires some form of work on the self. Examples of this kind of solution include, believing victims of sexual assault, ignoring gaslighters, being an ally, committing to personal growth, listening, and seeking help for personal issues.

This is furthered by the interweaving of activist and therapeutic language. For example, readers are asked to commit to ‘personal growth’, ‘center in calm, not fear’ and ‘unlearn’ certain thoughts and behaviors. Slideshows explicitly devoted to work on the self-appear at regular intervals in the sample. They punctuate the steady stream of political and activist centric content to inject some care into Account A’s feed. Indeed, some of these posts are explicitly aimed at recovering positive feelings regarding current political events – and are exemplary of how the Account itself practices the same form of self-care that it recommends to its own readers.

An exemplar case of this kind of content is a slideshow devoted to mental health. The slideshow starts by asserting the importance of paying attention to one’s mental health. It then offers the reader a range of diagnostic tools centered through which they could assess their own wellbeing. For example, readers are asked to take note of their physical state, such as to check if they are clenching their jaw or have a tightness in their chest (see ). Readers are also asked to examine their emotional needs by asking themselves whether they feel emotionally safe. Following this, solutions are offered which include being compassionate to oneself and consciously grasping one’s emotions. A few additional diagnosis tools and solutions are offered in the concluding slide.

This type of work is both inner-oriented, as in ‘change your behavior’, and explicitly social, as in ‘amplify minority voices’. Where care – of self and others – is important in specific online communities and contexts (particularly in feminist and LGBT activist communities (Andrucki, Citation2021; Edelman, Citation2020)), Account A merges it with a social justice oriented activist agenda, almost performing a therapeutic role. For example, within our sample we encountered slideshows which sought to communicate ‘good news’ to followers. These slideshows, which stood markedly apart from the rest of Account A’s content which typically focusses on problems, were justified as a way of breaking up the steady cycle of bad news and therefore providing some relief for followers. In this way, Account A practices care for its followers, thus modeling the kind of political activist subjectivity it advocates for it the rest of its content.

On the one hand, ‘working on the self’ reminds readers that the personal is indeed political (Clark, Citation2016); on the other, it re-articulates civic engagement as a behavior, rather than concrete civic processes such as voting or joining a protest. Occasionally, Account A would also mention other avenues of action, asking readers to register to vote, donate, volunteer, and write or call their elected representatives. Yet, the latter are interwoven with internal work on the self that results in external action in one’s private sphere of influence, such as listen to marginalized groups and continue difficult conversations with those around you. Cognitions, attitudes and actions become fused with each other; the ideal citizen across these slideshows is an individual constantly working from the inside out. Politically responsible civic action thus becomes an expression of the inner work that an individual does upon themselves.

Conclusion

With the emergence of slideshow activism as an activist tactic and a strategy for civic engagement, the popularity of Account A suggests the crystallization of a successful recipe for leveraging Instagram’s visual aesthetics for activist purposes: a ‘carousel’ format for segmenting political information into smaller bits; a simple rhetorical formula for presenting political content, expressed as problem definition→provision of factual support→solution and/or call for action with transparent sourcing; and the use of a visual aesthetic such as the pastel color-palette, graphs, and font sizes for rendering text compatible with an image-based platform.

While this recipe leverages Instagram’s templatability (Leaver et al., Citation2020) for an activist purpose, its approach to the provision of political information remains ambivalent. Slideshows foreground reasoned arguments in support of a particular normative stance, offering followers ready-made definitions, statistics, and quotes that can be used to explain one’s position in a manner consistent with the ideal of deliberative democracy. Sharing a slideshow with one’s social media network can thus become both a statement of, and as a set of validity-claims for, one’s politics. On the other hand, such slideshows address those already committed to social justice principles by often adopting a good/ bad lens in editorializing issues and public figures. In that sense, Account A’s slideshows advocate a normative stance; they act as a rolodex of supporting stats and quotes enabling the reader to competently defend their stance. Like other forms of digital activism, the slideshow activism examined here produces ‘a sense of identity-like connectedness based on shared emotions’ (Milan & Barbosa, Citation2020, np). Here, shared emotions are implied in the followers’ implied commitment to social justice, while the slideshows foreground reason and argumentation. While this can help individuals engage in political discussions, lack of awareness on the interweaving between ideological resonance and argumentation risks demonizing disagreement as irrational and misinformed.

By integrating persuasion and marketing principles in its message, Account A’s formula for slideshow activism creatively reappropriates commercial and leisure-oriented social media platforms for political participation (Gordon & Mihailidis, Citation2016; McFarland, Citation2010). Its strength resides in its low-cost nature: producing political informational content is relatively easy, requiring mostly digital marketing and persuasive skills, along with time investment. The consumption and further peer-to-peer dissemination of these slideshows also remains a low-cost investment for followers. Re-sharing slideshows in particular holds the promise of rekindling interest in politics by circumventing the tiredness associated with activist campaigns (Jenkins & Deuze, Citation2008). In other words, the re-posting of a slideshow outside of peak moments in the lifecycle of a protest, a campaign, or a movement may generate interest in the issue/ cause among the network of peers. While such a tactic lowers the threshold of participation, it also risks making participation seem too easy (Van Laer & Van Aelst, Citation2010). Yet, Account A’s ability to reach out beyond the echo-chambers of audiences already interested in social justice and to confront the decision-making elites remains unclear.

One of the most promising forms of impact, however, remains the ability to spur civic engagement on an individual level. By providing pre-digested (and editorialized) political information, slideshow activism can interpellate followers as citizens, promising to empower them for political participation. In the case of Account A, however, this form of political participation interweaves political knowledge with techniques for ‘working on the self’ in order to become a better citizen (Foucault, Citation1982). Through framing political problems and their respective solutions, it asks its followers to internalize its normative ideal and change themselves accordingly. As personal transformation becomes a means of political participation, Account A stitches together the deliberative ideal of the rational citizen with the neoliberal ‘glorification of individual self-help and responsibility’ (Brodie, Citation2007, p. 102). In turn, the political work towards social justice now appears attainable by virtue of personal transformation and peer-sharing of suitable recipes for doing so. The case study explored here (re)produces wider trends in the personalization of politics (Bennett, Citation2012), where the personal is not just political (Clark, Citation2016), but also a form of political intervention.

Yet, Account A’s popularity also showcases slideshow activism’s potential to spur civic engagement in an otherwise commercial, leisurely-oriented space. In that sense, such forms of digital activism can revitalize civic culture by helping followers ‘develop into citizens’ (Dahlgren, Citation2005, p. 158). Account A also performs an important grassroots digital leadership role by drawing attention to issues and providing shared frames for their interpretation (Bakardjieva et al., Citation2018). Finally, it contributes to ‘promoting new grammars, new social paradigms through which individuals, collectivities, and institutions interpret social circumstances and devise responses to them’ (Young, Citation1997: 3). This use of slideshow activism demonstrates how social media platforms can become political spaces, entrenching social justice as a core political value for civic engagement and training followers in the production of validity-claims for their (political) position. Our case study thus shows how slideshow activism can blend participatory and deliberative models of politics.

A limitation of our study is that it can only speculate on the distribution and consumption of these slideshows. We also note that our arguments are premised on the rather successful (at least in terms of social media metrics) case of Account A. We cannot assume that slideshow activism is always animated by social justice causes; nor can it be assumed that it enacts (self) care as an ethical value crucial to the exercise of politics. Further research that takes a comparative approach to different slideshow activist accounts is thus needed.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution of their research assistant, Hong Nguyen (IBCoM student, Erasmus University Rotterdam), to the data analysis process.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Delia Dumitrica

Delia Dumitrica is Associate Professor in the Media & Communication program at Erasmus University Rotterdam. She has researched the use of digital technologies in citizen-led activism in Canada and Europe. In addition to that, she is also interested in the representation of new media in popular culture, as well as everyday nationalism. email: [email protected]

Hester Hockin-Boyers

Hester Hockin-Boyers is Assistant Professor in the Department of Sport and Exercise Sciences at Durham University (UK). She completed her PhD at Durham University in January 2022, which explored women’s use of weightlifting as an informal strategy for recovery from eating disorders. Her current research interests cohere around physical activity, eating disorders and digital spaces. email: [email protected]

References

- Amit-Danhi, E. R., & Shifman, L. (2018). Digital political infographics: A rhetorical palette of an emergent genre. New Media & Society, 20(10), 3540–3559. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444817750565

- Andrucki, M. J. (2021). Queering social reproduction: Sex, care and activism in San Francisco. Urban Studies, 58(7), 1364–1379. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098020947877

- Aouragh, M., & Chakravartty, P. (2016). Infrastructures of empire: Towards a critical geopolitics of media and information studies. Media, Culture & Society, 38(4), 559–575. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443716643007

- Bakardjieva, M. (2009). Subactivism: Lifeworld and politics in the age of the internet. The Information Society, 25(2), 91–104. doi: 10.1080/01972240802701627

- Bakardjieva, M., Felt, M., & Dumitrica, D. (2018). The mediatization of leadership: Grassroots digital facilitators as organic intellectuals, sociometric stars and caretakers. Information, Communication & Society, 21(6), 899–914. http://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2018.1434556

- Benford, R. D., & Snow, D. A. (2000). Framing processes and social movements: An overview and assessment. Annual Review of Sociology, 26(1), 11–39. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.26.1.611

- Bennett, L. W., & Segerberg, A. (2013). The logic of connective action: Digital media and the personalization of contentious politics. Cambridge University Press.

- Bennett, W. L. (2012). The personalization of politics: Political identity, social media, and changing patterns of participation. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 644(1), 20–39. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716212451428

- Bracewell, L. (2021). Gender, populism, and the QAnon conspiracy movement. Frontiers in Sociology, 5, 426. http://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2020.615727

- Brodie, J. M. (2007). Reforming social justice in neoliberal times. Studies in Social Justice, 1(2), 93–107. https://doi.org/10.26522/ssj.v1i2.972

- Burgess, J. (2006). Hearing ordinary voices: Cultural studies, vernacular creativity, and digital storytelling. Continuum: Journal of Media and Culture Studies, 20(2), 201–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/10304310600641737

- Castells, M. (2004). The network society: A cross-cultural perspective. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Chadwick, A. (2013). The hybrid media system: Politics and power. Oxford University Press.

- Christensen, H. S. (2011). Political activities on the Internet: Slacktivism or political participation by other means? First Monday, 16(2), n.p. https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v16i2.3336

- Clark, R. (2016). “Hope in a hashtag”: The discursive activism of #WhyIStayed. Feminist Media Studies, 16(5), 788–804. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2016.1138235

- Dahlgren, P. (2005). The internet, public spheres, and political communication: Dispersion and deliberation. Political Communication, 22(2), 147–162. doi:10.1080/10584600590933160

- Dahlgren, P. (2013). The political Web: Media, participation and alternative democracy. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Edelman, E. A. (2020). Beyond resilience: Trans coalitional activism as radical self-care. Social Text, 38(1 (142)), 109–130. https://doi.org/10.1215/01642472-7971127

- Fornet-Betancourt, R., Becker, H., Gomez-Müller, A., & Gauthier, J. D. (1987). The ethic of care for the self as a practice of freedom: An interview with Michel Foucault on January 20, 1984. Philosophy & Social Criticism, 12(2–3), 112–131. https://doi-org.eur.idm.oclc.org/10.1177019145378701200202 https://doi.org/10.1177/019145378701200202

- Foucault, M. (1982). The subject and power. Critical Inquiry, 8(4), 777–795. https://doi.org/10.1086/448181

- Gehl, R. W. (2015). The case for alternative social media. Social Media + Society, 1(2), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305115604338

- George, J. J., & Leidner, D. E. (2019). From clicktivism to hacktivism: Understanding digital activism. Information and Organization, 29(3), 1–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infoandorg.2019.04.001

- Gerbaudo, P. (2017). From cyber-autonomism to cyber-populism: An ideological history of digital activism. TripleC: Communication, Capitalism & Critique, 15(2), 478–491. https://doi.org/10.31269/triplec.v15i2.773.

- Gerrard, Y. (2020). What’s in a (pseudo)name? Ethical conundrums for the principles of anonymisation in social media research. Qualitative Research, 21(5), 686–702. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794120922070

- Gibbs, M., Meese, J., Arnold, M., Nansen, B., & Carter, M. (2015). #Funeral and Instagram: Death, social media, and platform vernacular. Information, Communication & Society, 18(3), 255–268.

- Gordon, E., & Mihailidis, P. (2016). Introduction. In E. Gordon & P. Mihailidis (Eds.), Civic media. Technology/ design/ practice (pp. 1–26). The MIT Press.

- Halupka, M. (2014). Clicktivism: A systematic heuristic. Policy & Internet, 6(2), 115–132. https://doi.org/10.1002/1944-2866.POI355

- Halupka, M. (2016). The rise of information activism: How to bridge dualisms and reconceptualise political participation. Information, Communication & Society, 19(10), 1487–1503. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2015.1119872

- Heller, K. J. (1996). Power, subjectification and resistance in foucault. SubStance, 25(1), 78–110. https://doi.org/10.2307/3685230

- Jenkins, H., & Deuze, M. (2008). Editorial: Convergence culture. Convergence, 14(1), 5–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856507084415

- Johnson, J. (1991). Habermas on strategic and communicative action. Political theory, 19(2), 181–201.

- Joyce, M. (2010). Introduction: How to think about digital activism. In M. Joyce (Ed.), Digital activism decoded: The new mechanics of change (pp. 1–14). International Debate Education Association.

- Kaun, A., & Uldam, J. (2018). Digital activism: After the hype. New Media & Society, 20(6), 2099–2106. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444817731924

- Kligler-Vilenchik, N. (2017). Alternative citizenship models: Contextualizing new media and the new “good citizen”. New Media & Society, 19(11), 1887–1903. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444817713742

- Leaver, T., Highfield, T., & Abidin, C. (2020). Instagram: Visual social media cultures (1st edition). Polity.

- Ledford, V., & Salzano, M. (2022). The Instagram activism slideshow: Translating policy argumentation skills to digital civic participation. Communication Teacher, doi:10.1080/17404622.2021.2024865

- Lovejoy, K., & Saxton, G. D. (2012). Information, community, and action: How nonprofit organizations use social media. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 17(3), 337–353. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2012.01576.x

- Madison, N., & Klang, M. (2020). The case for digital activism: Refuting the fallacies of activism. Journal of Digital Social Research, 2(2), 28–47. https://doi.org/10.33621/jdsr.v2i2.25

- Markham, A. (2012). Fabrication as ethical practice. Information, Communication & Society, 15(3), 334–353. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2011.641993

- McFarland, A. S. (2010). Boycotts and dixie chicks. Creative political participation at home and abroad. Paradigm Publishers.

- Milan, S. (2015). From social movements to cloud protesting: The evolution of collective identity. Information, Communication & Society, 18(8), 887–900. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2015.1043135

- Milan, S., & Barbosa, S. (2020). Enter the WhatsApper: Reinventing digital activism at the time of chat apps. First Monday, 25(1), np. https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v25i1.10414

- Nguyen, T. (August 12th, 2020). How social justice slideshows took over Instagram. Vox. Accessed at: https://www.vox.com/the-goods/21359098/social-justice-slideshows-instagram-activism

- Ofori-Parku, S. S., & Moscato, D. (2018). Hashtag activism as a form of political action: A qualitative analysis of the #BringBackOurGirls campaign in Nigerian, UK, and U.S. Press. International Journal of Communication, 12, 2480–2502.

- Salzano, M. (2021). Technoliberal participation: Black lives matter and Instagram slideshows. AoIR Selected Papers of Internet Research, 2021. https://doi.org/10.5210/spir.v2021i0.12034

- Smith, A. (May 13th, 2021). Social justice slideshows are going viral on Instagram – here’s what to remember about what they’re sharing. The Independent. Accessed at: https://www.independent.co.uk/tech/israel-hamas-instagram-viral-slideshow-b1846951.html

- Snow, D. A., & Benford, R. D. (1988). Ideology, frame resonance, and participant mobilization. International Social Movement Research, 1(1), 197–217.

- Thorson, K. (2012). What does it mean to be a good citizen? Citizenship vocabularies as resources for action. ANNALS, 644(1), 70–85. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716212453264.

- Treré, E. (2019). Hybrid media activism. Ecologies, imaginaries, algorithms. Routledge.

- Tufekci, Z. (2013). “Not This One”: Social movements, the attention economy, and microcelebrity networked activism. American Behavioral Scientist, 57(7), 848–870. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764213479369

- Van Laer, J., & Van Aelst, P. (2010). Internet and social movement action repertoires. Information Communication & Society, 13(8), 1146–1171. doi:10.1080/13691181003628307

- Young, S. (1997). Changing the Wor(l)d: Discourse, politics, and the feminist movement. Routledge.