ABSTRACT

This contribution seeks to demonstrate how studying memes as a collection depends on the website or platform where they are sourced. To do so, we compare how memes, specifically internet memes, are conceived in the well – known meme repository (Know Your Meme) with those from a meme host and generator (Imgur), an imageboard (4chan), a short-form video hosting site (TikTok) as well as a marketing data dashboard (CrowdTangle). Building on insights from software studies and our observational analysis, we demonstrate how each site constructs and arranges meme collections in a distinctive manner, thus affecting the conceptualisation of memes by each of these sites. In all, the piece develops the concept of the meme as a technical collection of content, discussing how each collection’s distinctiveness has implications for meme research.

Introduction: The meme as technical collection of content

The popularity of internet memes in contemporary digital society is widely acknowledged. Beginning as a niche phenomenon (Zanettou et al., Citation2018), memes have long found a home in mainstream digital media, where they have become an ‘ubiquitous, arguably foundational, digital media practice’ (Miltner, Citation2018, p. 412). Besides constituting an integral part of users’ online interactions, they have carved out a significant role in public discourse for their ability to spread ideas and influence debates during elections, protests, and social movements (Heiskanen, Citation2017; Milner, Citation2013; Mina, Citation2019). Similarly, marketing experts and practitioners implement memes in advertising campaigns both as a captivating strategy (Bury, Citation2016) and as a means to interact with consumers (Sharma, Citation2018).

Memes have become a significant object of study for academic research, too, where media and communication scholars understand them as groups of digital objects collectively created, transformed, and circulated online (Shifman, Citation2013). Particularly in the study of digital culture, memes are considered a key manifestation of participatory culture, both in the original creative vernacular sense but also in antagonistic trolling and other darker forms of participation (Nagle, Citation2017; Tuters & Hagen, Citation2020). In this respect, memes are considered a communication genre (Wiggins, Citation2019), requiring ‘new literacies’ (Knobel & Lankshear, Citation2007) for recognition but also for in-group participation (Milner, Citation2016).

While research has focused on the social and cultural aspects of the phenomenon, looking at memes as ‘piece of culture, typically a joke’ (Davison, Citation2012), ‘apparently insignificant embodiments of silliness and whimsicality’ (Shifman, Citation2014) or ‘common tongue’ of the internet (Milner, Citation2016), the purpose here is to understand memes as technical collections of content. This perspective appears relevant when considering their pervasiveness online: as they spread across different digital spaces, we argue, memes acquire specificities depending on the site where they are constructed. Thus, in our reading, memes are understood as collections of technical content resulting from a combination of digital participatory culture as well as software production practices.

Foregrounding considerations of the meme as technical content, we offer an account of how meme collections are constituted across different websites and platforms. The sites taken up include a meme database, a meme host and generator, an imageboard, a short-form video hosting site as well as a marketing data dashboard with a ‘meme search’ feature. Through comparing the meme collections across these sites, we provide practical points about what each set includes or downplays, but also how the distinctiveness of the collections have implications for meme research.

From meme to meme collections

Memes are broadly understood as multimodal cultural artefacts, which are created, remixed and circulated by users across digital platforms (Davison, Citation2012; Milner, Citation2016; Shifman, Citation2014). While such a definition has spread within media research during the past two decades, the origin of the term dates to the 1970s and is tied to the study of memetics.

The meme is a neologism originating from the biologist Richard Dawkins, who defined it as the cultural equivalent of the gene (Citation1976). The meme has sparked debates across disciplines about its utility as well as formal study (Blackmore, Citation2000; Distin, Citation2005). Those debates and the much longer intellectual genealogy of the notion prior to Dawkins’s intervention have been well covered elsewhere (Schlaile, Citation2021). One aspect is of interest here, however, for it concerns the medium or carrier of memes. Dawkins (Citation1982) introduced the concept of the ‘vehicle’ to physically locate memes outside of the human mind. In doing so, he defined vehicles as ‘any unit, discrete enough to seem worth naming, which houses a collection of replicators, and which works as a unit for the preservation and propagation of those replicators’ (p. 114). Put differently, a vehicle is something that contains and protects replicators, enabling them to make further copies of themselves. In a similar way, Dennett (Citation1991) argues that memes are ideas carried around by physical objects that encapsulate them: books, pictures, tools and buildings are all cited as examples of vehicles, insofar as they contain one or more memetic ideas within them. Certain early memetics scholars even identified the internet (Bjarneskans et al., Citation1999) or, as Heyligen calls it, the ‘global computer network’ (Citation1996) as a meme vehicle worthy of study.

More recently, media and communication scholars (Lunenfeld, Citation2014; Vada, Citation2015), in line with user vernacular practice, have furnished memes with a single vehicle or medium: the internet (Sampson, Citation2012; Tuters, Citation2021). Following the popularisation of the term (Milner, Citation2016), they also denaturalised the meme, claiming that user contributions to memes are what distinguishes them from viral content and what makes them additive rather than stand–alone material (Dynel, Citation2016; Shifman, Citation2014). That is, while virals circulate unchanged across platforms, the trademark of memes is their creative re – elaboration (Knobel & Lankshear, Citation2007). Owing to their continual refashioning, memes are viewed as a collection of online artefacts rather than as single pieces.

A significant turning point in the development of meme theory was marked by the intuition to look at memes not as single units or ideas but as groups of content. Shifman (Citation2014) contends that memes maintain a close relationship with each other, ‘(a) sharing common characteristics of content, form, and/or stance; (b) that were created with awareness of each other; and (c) were circulated, imitated, and/or transformed via the Internet by many users’ (p. 8). In this sense, memes, rather than isolated artefacts, are regarded as a full–fledged genre, with sets of socially constructed rules and conventions (Wiggins & Bowers, Citation2015). Ultimately, works that define memes as expressive and semiotic repertoires (cf. Nissenbaum & Shifman, Citation2018) shed light on the culturally and socially-rooted practices of sharing, interpretation and modification, moving away from the diffusionist approach suggested by memetics (de Seta, Citation2016).

In doing so, however, these accounts overshadow the fact that meme conceptualisation also depends on the online sites in which they are created and circulated. In fact, when looking at empirical studies on memes, the selection of certain sites for meme collection and analysis (instead of others) appears to have had an impact on the composition of the sample and, by extension, on the general perspective of the research. For instance, works relying on the database Know Your Meme for sampling and validation focus on standardised formats and layouts (Hristova, Citation2014; Kumar & Varier, Citation2020; Zanettou et al., Citation2018). Conversely, studies sourcing memes from social media as Instagram and Twitter may present a more varied pool of formats (Al-Rawi et al., Citation2021). Crucially, Du et al. (Citation2020) found that meme types that are prevalent in their dataset gathered on Twitter were not included in archives like Know Your Meme. These examples demonstrate how the meme sets returned by different sources may vary in their composition and specificities.

Building upon these considerations, we call for a more granular conceptualisation of meme collections which ties together the cultural aspects and the technical specificities of the online sites employed for the data collection. Hence, our work intends to offer an overview of the meme collections assembled by a selection of them. As stated at the outset, our point of departure is the meme as a collection, but the main argument is that these sets are constructed in heterogeneous manners, which then affects the composition of the collection.

While we concentrate on the implications for scholarly research that includes methodologies for meme collection-making, we also would like to suggest that the outlook here has broader implications for the study of online cultural production and discourse. Our analysis suggests the fruitfulness of disaggregating online memetic practice by platform, fitting with other calls for de-globalizing the sites often relied upon for meme scholarship (Nissenbaum & Shifman, Citation2018).

Methodology: selection and analysis of sites of meme studies

We take up several sites where memes have been located and studied over time to examine how each constructs the internet meme and what these collections imply for their study.

The selection of these online sites follows from exploratory research of existing literature on memes, aimed at identifying key sites for meme production and circulation. We identified five such sites: Know Your Meme, the highest-ranking meme humour website (according to SimilarWeb's category of entertainment and humour) (2022) and the reference site for meme definitions and examples (Pettis, Citation2021); Imgur, the top-ranked meme hosting site (SimilarWeb, Citation2022), widely used by research to source memetic material (Brubaker et al., Citation2018; Eisewicht et al., Citation2021); 4chan, the ‘best known and widely used English-language imageboard’ (Cramer, Citation2021), historically known as one of the cradles of memes and meme culture (Zanettou et al., Citation2018); TikTok, known for its memetic infrastructure (Zulli and Zulli, Citation2020) and its role in spreading memetic content (Schellewald, Citation2021); and CrowdTangle, the Meta-owned marketing data dashboard and main point of (official) access to Facebook and Instagram data, for its recent usage in meme-centred research and its special ‘meme search’ feature (Al-Rawi et al., Citation2021; Lee & Hoh, Citation2021). While we realise our pool is not exhaustive, given the pervasiveness of memes in digital culture, we maintain that each site analysed is an exemplary type where one can distil a distinctive meme collection from a sorting or grouping logic: Know Your Meme as crowdsourced meme database, Imgur as host and generator with image macro templates, 4chan as imageboard with a dark participatory subculture, TikTok as video host with memetic sound linking and CrowdTangle as marketing data dashboard with a meme search function.

Having selected the online sites, we aim to offer an exploration of the internet meme’s technicity, or how it can be seen as ‘technologically composed content’ per site (Niederer, Citation2018, p. 25). From software studies (Fuller, Citation2008) and ‘networked content analysis’ (Niederer, Citation2018) we borrow the term ‘technicity’ (Niederer & Van Dijck, Citation2010) to capture the idea of the meme as ‘technologically composed’, ‘co–constituted’ or constructed by its online environment (Bucher, Citation2012) as well as materially distinctive depending on that milieu. Following this ‘technicity of content’ approach, we undertake an observational analysis of the online sites and their relevance for meme production and dissemination.

Each of the following sections provides the historical background of the website or platform and highlights its relevance – both for users and academic research – with respect to content creation as well as participatory culture. We then examine the technical features of these spaces, focusing on how meme collections are conceived, arranged and retrieved. In this respect, we have looked at the storing strategies (e.g., topic-based and template-based galleries), ordering modalities (e.g., according to popularity or the time of publication) as well as the querying and filtering possibilities (e.g., hashtag, timeframe, and/or language). In conclusion, we compare the different meme collections that can be sourced from these sites, reflecting on the implications for meme research of choosing one collection over another.

Know Your Meme: a special collection of internet phenomena

Know Your Meme (KYM), one of the earliest and most well–known meme repositories, began in 2007 as a segment in the Rocketboom web video series, a ‘daily satire news vlog in the style of The Daily Show’ (Cohn, Citation2005). Rocketboom reported on the goings–on online, and memes were an integral part. The segment, which quickly became its own show, rooted out the origins and influences of a particular meme, not so unlike Gimlet Media’s Reply All podcast that succeeded it. At the same time, Rocketboom compiled memes on its website, a crowdsourced wiki that remains a standard source of internet memes to this day, lending credence to the perspective that internet memes descend largely from American digital culture (Milner, Citation2016; Nissenbaum & Shifman, Citation2018). Prior to the existence of KYM, researchers would trawl numerous websites (such as fark.org or somethingawful.com) and search engines (such as technorati.com for the blogosphere) to locate memes (Knobel & Lankshear, Citation2005). Seeking out memes on Geocities, Usenet and via Gopher file lists also had its scholarly antecedents.

The initial KYM directory listing of meme types provides a sense of what is practically meant by a meme (see list below). It should be pointed out that the examples listed under these types are mainly videos, either humorous or impressive for the artistic performance on display, such as some of the early classics of so–called user-generated content, including ‘Numa Numa’ (2004) and the ‘Evolution of Dance’ (2006). It also should be noted that this collection of digital cultural production is considered specific to the internet, or ‘Internet phenomena’, as KYM phrased it.

List of Know Your Meme’s early classification of meme types. Source: Rocketboom, Citation2008.

Natural Parody

Media Non–Sequiturs

Piggyback

Singing

Dancing

Line Rider

Interruption

Animals

Tasers

Shock/gross–out

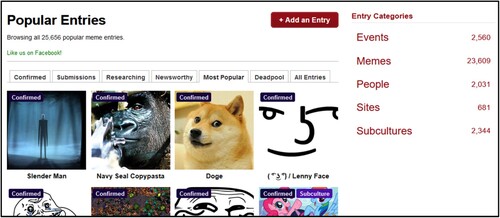

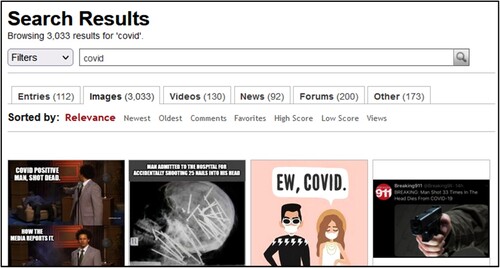

Of special interest is the classification that takes place on KYM, which makes use of labelling to indicate the status, type and contents of the meme entry. There are broadly two ways to create collections of memes on the site: browsing or querying the database. When browsing, one notes the active research process behind KYM’s crowdsourcing and editorial management: memes have been submitted and they are confirmed or still being researched (see ). Popular ones are noted. There is also the ‘dead pool’ or bin, which are rejected meme entries. When searching, one notes the results of the research process: vetted memes that are archived and labelled (see ).

Figure 1. Overview of the meme database of Know Your Meme, 5 August 2022. Source: https://knowyourmeme.com.

Figure 2. Research results for the keyword ‘covid’ on Know Your Meme, 5 August 2022. Source: https://knowyourmeme.com.

Apart from the sourcing and classification practice, we also see the emergence of the distinction between memetic and viral content. In the dead pool bin is ‘commercialismo’, which is described as material that has been ‘planted’ by marketing operatives with the aim of making it ‘contagious’ (Rocketboom, Citation2008). Finally, KYM’s discussion of the meme as part of distinctive ‘internet phenomena’ is relevant not only to the emergence of the internet as main meme vehicle but also to their database as a special collection. This early definition of memes provided by Rocketboom is in line with Jenkins’s notions of ‘participatory culture’ (Citation2006) as well as ‘spreadable media’ (Jenkins et al., Citation2018), adding that the difference between the fad/viral/commercialismo and meme lies in ‘its adoption, reuse, and remixing by a much wider audience’ (Rocketboom, Citation2008).

Meme generator (Imgur): the templatable meme collection

Founded in 2009, Imgur is an American online image hosting and sharing service, mostly hosting viral images and memes. The relevance of this site for meme research is demonstrated by a number of studies regarding Imgur as a large repository of memes and a database for collecting samples (Askanius, Citation2021; Brubaker et al., Citation2018; Eisewicht et al., Citation2021). Imgur also has an in-built meme generator service, a feature included in 2013 that allows users to deploy a variety of image macro templates. The macro is one computing term for executable instructions, which in this case is how text should be mapped onto an image. The format has superseded others in popularity, and many recent analyses of memes are based on them (Brubaker et al., Citation2018; Yus, Citation2018).

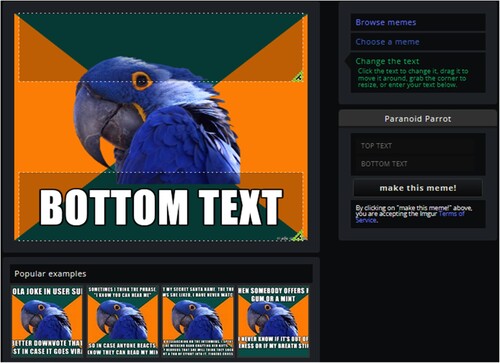

For image macros generated on Imgur, the user can either choose one of the available templates or upload an image. The option ‘select a default meme’ on Imgur opens a dropdown menu of popular standardised templates (e.g., Advice Animals or One Does Not Simply), searchable by name. Once selected, the user can personalise the caption (see ). The input is (by default) two lines of text placed above and below the image, an opener and a thought completion (Yus, Citation2021), though a single line of text is also an option (Brideau & Berret, Citation2014; Vickery, Citation2014).

Figure 3. Overview of Imgur’s meme generator, 5 August 2022. Source: https://imgur.com.

The emergence of online generators simplified the process of meme creation, making it more open and accessible, compared to Photoshop which required a digital skill set. Echoing the considerations advanced by Brideau and Berret (Citation2014), meme generators have also provided a certain ‘stability’. In a sense, the image macro, embedded in web applications for image captioning, standardised memes by providing them with not just a format but also a means to automate or ‘generate’ them. The template creates a fixity upon which the replicative practice rests. Such templating also ensures both their recognition and continuity as a media artefact.

Ultimately, the conceptualisation of memes emerging from this type of site coincides with the image macro, which is perhaps the most successful template that makes a meme recognisable as such (Börzsei, Citation2013; Lugea, Citation2019). Below the section where new memes can be created, users find a gallery of examples using the same image macro, which are labelled as ‘popular examples’ (see ). These memes form template-based meme collections, which may be employed for meme research focusing on the role of image macro in meme culture. The fact that these memes are categorised as ‘popular’ is of particular relevance to understand the role of Imgur’s meme generator in creating and spreading prescriptions guiding the creation of new memes. This is important considering that meme creation and consumption rest on contested and socially negotiated cultural literacy (Nissenbaum & Shifman, Citation2017). These selections offer a sample of how memes with that macro image should be created, contributing to defining how successful (and socially acceptable) ones are constructed. In this sense, we may argue that Imgur’s meme generator contributes to the creation of a memetic canon, providing users with best practice on how to create rewarding memes.

TikTok: the infrastructural meme collection

TikTok, the short-form video platform, is the most recent site of video meme study (Weimann & Masri, Citation2020). Platforms such as YouTube and Vine (now defunct) are also associated with video memes (Silva & Garcia, Citation2012), which as discussed have been central to the early study and collection of memes as ‘internet phenomena’. While academic research on TikTok is still in its early stages, a number of scholars suggests that the platform is much more than a ‘virtual playground’ for young users (Bresnick, Citation2019), highlighting the impact of memes and trends on political discourse (Literat & Kligler-Vilenchik, Citation2019; Medina Serrano et al., Citation2020) as well as the spread of information (and misinformation) around the Covid pandemic (Basch et al., Citation2021).

Launched by the Chinese-based company ByteDance, TikTok has become one of the most popular and downloaded apps in the world, attaining around 1 billion active monthly users at the time of writing (Doyle, Citation2022). As an evolution of Musical.ly (which it acquired), TikTok use is embedded in practices of remixing and repurposing music. The relevance of music in the creation of memes is demonstrated by exemplary forms of playfully remixing audio and visual elements, which include such genres as the already mentioned misheard lyrics (Shifman, Citation2014) or the ‘musicless music video’ (Sánchez–Olmos & Suárez, Citation2017).

Music is one of the primary initiators of memes on TikTok (Vizcaíno–Verdú & Abidin, Citation2021). Not only is music used to create ‘dance challenges’ that are subsequently imitated, recorded, and posted by users (Bresnick, Citation2019), but as noted by Klug ‘a main practice is to create a performance that, through contextual knowledge, transforms a line of lyrics into a new statement, meme, or viral phenomenon’ (Citation2020, p. 5).

Zulli and Zulli (Citation2020) expand upon this point describing TikTok’s infrastructure as memetic. Specifically, they argue that the design of the platform invites users to engage with existing content following the principle of mimesis through shared rituals of imitation and replication. One such way is to create a duet or chain videos responding to other users. Another is replicating the structure of other videos (through gesture, content and/or sound). These videos are linked together by the platform, where the user can follow a chain of videos using the same sound, for example.

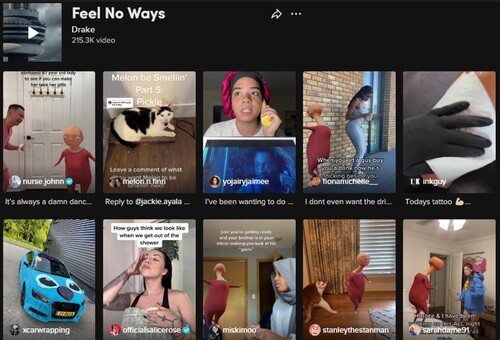

The logic of mimesis and reappropriation fostered by the platform leads to new forms of social interaction, encapsulated in the concept of ‘imitation publics’ (Zulli & Zulli, Citation2020). These claims resonate with the present work as well, if we consider TikTok as a provider and an aggregator of video–meme templates. It even could be argued that the platform’s infrastructure accomplishes a function like a meme generator for static image memes, insofar as it provides users with the tools (e.g., music sounds, filters and effects) to create memetic instances. Many meme generators’ primary usage, however, is for insertion or embedding elsewhere. On TikTok, contrariwise, video-memes constitute an integral part of the platform’s content and infrastructural organisation. Sound IDs and effects are also employed as indices for content: in this sense, we can see that a meme collection on TikTok can be understood as a group of videos employing the same music and/or the same visual filters and effects (see ).

Figure 4. Example of indexing on TikTok (content using the song Feel no Ways by Drake), 5 August 2022. Source: https://www.tiktok.com.

4chan: dark imageboard meme collection

Created in 2003 by Christopher Poole, aka moot, 4chan was conceived as an online image board with a focus on Japanese anime and manga and based on the anime-sharing site 2chan (Nagle, Citation2017). Over the years the site has grown from its anime roots to encompass a variety of boards on topics ranging from politics to music and from science to NSFW (or ‘not safe for work’) content. On 4chan, users post anonymously, as the site does not have a registration system: by default, new posts are invariably attributed to ‘Anonymous’, although it is possible to personalise the username. Threads receiving recent replies are moved to the top of their boards; old content is deleted as new material is published. The site is considered one of the largest incubators for memes, especially political ones (Nagle, Citation2017). The fast-paced exchanges among its users and the presence of a culture valuing original and quirky contributions encourage participation and the production of large quantities of user-generated content. In this vibrant context, memes are often created following the ‘Internet Ugly’ aesthetic described by Douglas (Citation2014), produced through ‘quick-and-dirty, cut-and-paste photo manipulation’ and used ‘as conversational volleys’ (p. 315).

4chan was at one time associated with both Anonymous, the loosely coordinated hackers out for lulz or entertaining pranks as well as memetic traditions like ‘caturday’, slang for ‘saturday’, a day dedicated to posting funny images of cats with purposely misspelt captions, commonly known as LOLCats (Miltner, Citation2014). Much of the activity took place on 4chan/b/, the ‘random’ board, 4chan’s first. The boards of 4chan, or at least the largest, witnessed something of a cultural shift, with the ascendancy of 4chan/pol/, the ‘politically incorrect board’. There, some of the pranking was directed at alternative right, or alt-right, causes (Nagle, Citation2017). Subsequently, with contributions from neighbouring 8chan, these practices gradually grew into QAnon, the serial of story drops concerning a wide-ranging conspiracy theory centred on the deep state (Hannah, Citation2021). The contributions have been described as part of a culture war, pitting them against those branded as ‘libtards’ or said to be shedding ‘liberal tears’ (Tuters, Citation2018).

Described as ‘both horrifying and fascinating’, 4chan was once linked to particular meme generators such as memegenerator.net, which would host many images for the board (Chen, Citation2012; Knuttila, Citation2011). Much of the image-sharing on the 4chan boards is memetic in the sense that one is contributing to image threads with additive content. In other words, users contribute images to threads, either initiating a thread with an image or replying to one with other images and/or a written comment (see ). As the practice of ‘caturday’ shows, the thread can consist of LOLcat image macros, sourced from memegenerator.net, where early 4chan image content was hosted. But memetic practice on 4chan also may take place across threads over longer periods of time, such as with the Pepe the Frog case, a symbol of the alt-right subculture and popular on 4chan (Pelletier-Gagnon & Pérez Trujillo Diniz, Citation2021; Woods & Hahner, Citation2019). Included in the Anti-Defamation League’s hate symbol database, it is an image-meme (rather than an image macro-based meme) that spurred wide variation both on the platform and beyond. Memes deployed on 4chan also may form and be circulated in the written comment text, as demonstrated by the spread of (((They))), a covert symbolic marking employed to indicate any Jew-related entity in a discriminatory way (Tuters & Hagen, Citation2020).

Figure 5. Example of 4chan thread from the board /pol/, 5 August 2022. Source: https://boards.4chan.org/pol/.

Compared to Know Your Meme, the memes circulating on 4chan/pol/ constitute a darker digital culture often attributed to the disinhibition afforded by anonymous posting combined with a particular user demographic (Coleman, Citation2012). 4chan’s darker pranking culture arguably inverts earlier forms of ‘participatory culture’ and ‘user-generated content’. The ‘ambivalent web’ is a term introduced to capture subcultural practices on 4chan and other darker online spaces where hateful and extreme remarks are delivered lightly as jokes or pranks; it is often difficult to establish intent, for they could ‘go either way’ (Phillips & Milner, Citation2018). ‘Dark participation’ (Quandt, Citation2018), similarly, has been offered as a counterpoint to earlier forms of online participation once celebrated for their vernacular creativity. With the dark turn in certain spaces online, productive, creative contributions such as user-generated content yield to less ‘earnest’ ones in image boards and comment spaces. Both the Pepe the Frog as well as the phrasal memes are examples of the 4chan community’s capacity for dark participatory culture: behind the seemingly playful memetic facade, they have been employed to spread polarising, hateful and discriminatory political messages across the site and beyond.

Meme collections on 4chan offer a variety of formats and realisations (e.g., phrasal memes and static, ‘Internet Ugly’ images). In this respect, memes embody the ambivalent culture of the site, torn between the urge for innovation through original content and the adherence to socially established codes and norms. It should be remarked that what is shared are not only memes in and across threads, but also instructions on how to make them circulate and ‘trend’. By providing generated memes as well as specific guidelines for their replication and spread, 4chan’s imageboards serve as sites for the study of memes in the form of their dark content, and, more in general, as part of (sub)cultural capital regulating users’ access and social status within online communities Nissenbaum & Shifman, Citation2018).

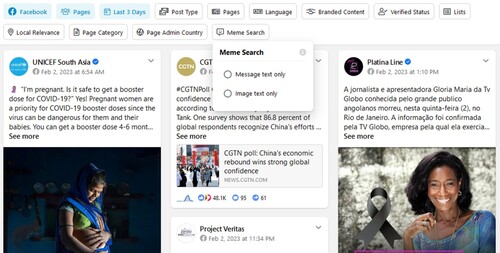

CrowdTangle: meme collection as text over images

Meta provides scholarly access to Facebook (and Instagram) data through the Social Science One initiative, founded in 2018 (King & Persily, Citation2019). One resource made available to scholars through this initiative is CrowdTangle, a marketing data dashboard acquired by Facebook in 2016. According to the official website, CrowdTangle ‘makes it easy to follow, analyse, and report on what’s happening with public content on social media’ (Bleakley, Citation2021). More specifically, the tool tracks and provides information about social media posts, including the time of publication, the account/page that posted the content and the numbers of interactions such as ‘likes’. As the data are provided by Meta, the tool faces the same problems of transparency and reliability affecting platform-owned resources (Marrazzo, Citation2022): platform providers are in charge of the selection process that grants or denies access, ‘limit[ing] scholarly inquiry to issues and topics that are unlikely to put pressure on the platform providing the data’ (Bruns, Citation2019, p. 9).

Nonetheless, CrowdTangle also grants undeniable advantages: the tool constitutes at the moment the best option to collect data from Facebook and Instagram. In fact, although it has been active for just a few years, it already has been deployed in research on memes within and across platforms (Al-Rawi et al., Citation2021; McKelvey et al., Citation2021). Furthermore, CrowdTangle provides several features to customise the data collection. Of particular interest here is the search function, which allows researchers to query the selected platform(s) for keywords and hashtags, with further filtering options. Of special interest is a feature called ‘meme search’ (see ), where one can create a meme collection of Facebook or Instagram posts. Memes are described alternately as ‘text over an image’ and ‘text in images’ (CrowdTangle, Citation2022). The text within the image is read by optical character recognition (OCR) and placed in the alt text attribute that provides descriptive text of the images for the visually impaired.

Figure 6. Overview of CrowdTangle search dashboard, 5 August 2022. Source: https://www.crowdtangle.com.

When using meme search with the option ‘image text only’, the user can query for the words in the attribute. The other option in meme search is ‘message text only’, which returns matches in the posts’ caption text. In the first instance, one may undertake ‘phrasal meme’ research, such as the propagation (and successful spread) of certain messaging across multiple meme images. With the latter query, one is searching for content associated with the memes, and the meme collection could be keyword, thematic or issue-based, e.g., a set of memes about a politician.

The conceptualisation of memes on Crowdtangle stretches beyond the boundaries of the standardised templates seen on Know Your Meme and Imgur’s meme generator (or those feeding 4chan culture). Specifically, the Meta-owned dashboard expands the conceptualisation – and thereby the collection-making – of memes to any image with text on it. On the one hand, this definition ties the concept of memes to multimodal realisations, thereby excluding memes that are only textual, such as (((They))), mentioned above. Nonetheless, datasets gathered via the dashboard include a great variety of digital content, such as screengrabs of news videos with running text, tweets embedded in Facebook posts and ‘social cards’, or placards with statements. Among other research avenues, the meme collection technique afforded by CrowdTangle allows one to study ‘memefication’, or how memetic practices are becoming embedded across media forms such as news and official information provision ().

Figure 7. CrowdTangle ‘meme search’ output for query ‘covid’, option ‘text only’, 25 November 2022, showing formats associated with memes (e.g., tweet screenshots, social cards and breaking news). Source: https://www.crowdtangle.com.

Conclusion: The study of technically composed meme collections

In line with Shifman (Citation2013), the point of departure has been that memes should be treated as collections of content, instead of single cultural units. Conceptually, our main argument is that memes are collections of technical content constructed in software environments online. Their composition varies depending on the site where they are sourced. To better illustrate memes’ ‘technicity of content’, we have observed how memes are conceptualised, arranged and sourced in a series of online resources that have played a key role in meme research. Each software rendering brings a different meme collection into being, with a focus on certain features and norms. That is, the collections of technical objects rendered by the online sites have different features that depend on whether they were amassed through a database, templating or other logic.

We argue that the technological composition of meme collections has implications for their study. For instance, in the early language of the Know Your Meme project, the database logic emphasises the new literacy and taste required to distinguish between the meme as special internet phenomena compared to fad/viral/commercialismo. Relying on this database could well orient the research towards playful digital culture, or how Davison framed the meme as a ‘piece of culture, typically a joke’ (Citation2012, p. 122).

This internet vernacular is a form of digital pop culture with its own literacies and participation norms that also has been critiqued in terms of the gender and ethnic asymmetries (Herring, Citation2003) and its (American) cultural orientation. An overreliance on KYM arguably ‘homogenises’ meme culture (Pettis, Citation2021). There are families of memes that are not present, such as global (and globalised) contributions which all use image macros (Nissenbaum & Shifman, Citation2018). Such repositories (that include memecenter.net) also invite inquiries into ‘why this is not just a joke’ (Yoon, Citation2016).

Meme collections originating from generators typically exploit the macro template as the most recognised meme format, giving it a stability and fixity for replicative practices. As such they mainstream the meme, making them less special or weird. Analytically, one of the main research consequences concerns how the template has mainstreamed the meme, shifting the emphasis in its study from special ‘internet phenomena’ and ‘vernacular creativity’ to massification, circulation and virality.

The imageboard, 4chan, has commentary threads made up of image posts and replies. It hosts a subculture which regards images (and memes) as a form of cultural capital and deploys them often ironically or ambivalently. These environments also can be seen as additive collections of peculiar ‘internet phenomena’, however distinctive (in their often extreme content) from Know Your Meme’s. While difficult to generalise, the imageboard rapidly supplies cultural commentary and forms subcultures to which those in the know contribute. Relying on such environments for meme research thereby opens the study of the meme and ‘memeing’ as part of in-group subcultures, connective culture and connective action (Bennett & Segerberg, Citation2012; Van Dijck, Citation2013). As seen, ‘dark’ forms of participation constitute the focus point of many studies relying on these environments. In fact, it should be noted that what is passed along are not only instances of memes but prescriptions on how to manipulate them. By providing actual realisations of memes as well as specific guidelines for their replication, the 4chan imageboard provides both the templates and conventions of use.

These cultural guidelines also are in place on platforms, whereby memes are part of the infrastructure. As noted, TikTok affords meme–making by providing means by which to link videos and sounds, thereby producing additive content. Timely usage of a trending sound as well as captioning images and deploying them to rise in the ratings may be described as a different ‘new literacy’, one which is performed by the user in participatory culture rather than by the collector of internet phenomena. Thus, research focusing on this deft usage of memes is concerned with shedding light on the interaction dynamics on platforms such as TikTok, where memes are employed as a form of reply and interaction among users.

Finally, CrowdTangle’s expansive definition of the meme as ‘text over an image’ has practical implications for meme research, for one receives the broadest trawl of image types and meme formats. The researcher can be more expansive in what constitutes a meme beyond a single template, opening up the prospect of studying the memefication of media forms, such as news images with embedded captions, making news resemble memes. More generally, CrowdTangle’s collection-making technique privileges text (rather than images), for one begins with a keyword search. The OCR that has been performed on memes transforms them into searchable text–and–image objects, where one may query the ‘text over an image’ as well as the captions. One would thereby be able to undertake ‘phrasal meme’ research, identifying (for example) the extent to which particular one or two-liners are employed across meme imagery.

Throughout we have been emphasising the difference made to the meme as a collection, depending on the site where it is sourced. The specificity of the collection resulting from a database, templating, infrastructural linking, image thread, or search logic, we also argue, has implications for meme and digital culture research. Certain techniques (such as Know Your Meme’s database) lead to studies of the ‘new literacy’ behind identifying special ‘internet phenomena’ and vernacular creativity. Others, such as meme generators, may emphasise less the specimen collection than the stability of the formatting that allows for a vast replicative practice and the mainstreaming of memes. Still others, like the marketing data dashboard, expand meme formats well beyond the meme generators’ image macros to Twitter screenshots, news items with captions and other examples of text over images, where one can study the memefication of other media forms.

While those we discuss are key sites for meme research, we suggest that the approach has broader application. As memetic practice moves across global digital cultures and spreads to other media platforms, there are further opportunities for studying not only the vernacular cultures but also the technical composition of meme collections.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Richard Rogers

Richard Rogers is Professor of New Media and Digital Culture, Media Studies, University of Amsterdam.

Giulia Giorgi

Giulia Giorgi is Postdoctoral Researcher, Department of Social and Political Sciences, University of Milan.

References

- Al-Rawi, A., Al-Musalli, A., & Rigor, P. A. (2021). Networked Flak in CNN and Fox News Memes on Instagram. Digital Journalism, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2021.1916977

- Askanius, T. (2021). On frogs, monkeys, and execution memes: Exploring the humor-hate nexus at the intersection of neo-Nazi and alt-right movements in Sweden. Television & New Media, 22(2), 147–165. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527476420982234

- Basch, C. H., Mohlman, J., Fera, J., Tang, H., Pellicane, A., & Basch, C. E. (2021). Community mitigation of COVID-19 and portrayal of testing on TikTok: descriptive study. JMIR Public Health and Surveillance, 7(6), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.2196/29528

- Bennett, W. L., & Segerberg, A. (2012). The logic of connective action. Information, Communication & Society, 15(5), 739–768. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2012.670661

- Bjarneskans, H. G. B., Grønnevik, B., & Sandberg, A. (1999). The lifecycle of memes. http://www.aleph.se/Trans/Cultural/Memetics/memecycle.html

- Blackmore, S. J. (2000). The meme machine. Oxford University Press.

- Bleakley, W. (2021). About us: learn more about CrowdTangle. CrowdTangle. https://help.crowdtangle.com/en/articles/4201940-about-us

- Börzsei, L. K. (2013). Makes a meme instead. New Media Studies Magazine. Utrecht University.

- Bresnick, E. (2019). Intensified play: Cinematic study of TikTok mobile app. Unpublished paper.

- Brideau, K., & Berret, C. (2014). A brief introduction to Impact: ‘The meme font’. Journal of Visual Culture, 13(3), 307–313. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470412914544515

- Brubaker, P. J., Church, S. H., Hansen, J., Pelham, S., & Ostler, A. (2018). One does not simply meme about organizations: Exploring the content creation strategies of user–generated memes on Imgur. Public Relations Review, 44(5), 741–751. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2018.06.004

- Bruns, A. (2019). After the ‘APIcalypse’: Social media platforms and their fight against critical scholarly research. Information, Communication & Society, 22(11), 1544–1566. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2019.1637447

- Bucher, T. (2012). A technicity of attention: How software'makes sense'. Culture Machine, 13, 1–13.

- Bury, B. (2016). Creative use of internet memes in advertising. World Scientific News, 57, 33–41.

- Chen, C. (2012). The creation and meaning of internet memes in 4chan: Popular internet culture in the age of online digital reproduction. Habitus, 3(1), 6–19.

- Cohn, D. (2005). The vlog world's greatest hits. Wired, 13 July.

- Coleman, G. (2012). Phreaks, hackers, and trolls and the politics of transgression and spectacle. In M. Mandiberg (Ed.), The social media reader (pp. 99–119). NYU Press.

- Cramer, F. (2021). What is urgent publishing?. APRIA Journal, 3(3), 33–43. https://doi.org/10.37198/APRIA.03.03.a3

- CrowdTangle. (2022). CrowdTangle from Facebook, Accessed August 19, 2022, from https://www.crowdtangle.com.

- Davison, P. (2012). The language of internet memes. In M. Mandiberg (Ed.), The social media reader (pp. 120–136). New York University Press.

- Dawkins, R. (1976). The selfish gene. Oxford University Press.

- Dawkins, R. (1982). The extended phenotype. Oxford University Press.

- Dennett, D. (1991). Consciousness explained. Penguin Books.

- De Seta, G. (2016). Neither meme nor viral: The circulationist semiotics of vernacular content. Lexia. Rivista di Semiotica, 25–26. https://doi.org/10.4399/978882550315926

- Distin, K. (2005). The selfish meme: A critical reassessment. Cambridge University Press.

- Douglas, N. (2014). It’s supposed to look like shit: The internet ugly aesthetic. Journal of Visual Culture, 13(3), 314–339. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470412914544516

- Doyle, B. (2022, April 21). TikTok Statistics - Everything You Need to Know. Wallaroo Media. Accessed August 19, 2022. https://wallaroomedia.com/blog/social-media/tiktok-statistics/.

- Du, Y., Masood, M. A., & Joseph, K. (2020). Understanding visual memes: An empirical analysis of text superimposed on memes shared on twitter. Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media (Vol. 14, pp. 153–164). https://doi.org/10.1609/icwsm.v14i1.7287.

- Dynel, M. (2016). I has seen Image Macros!’ Advice animal memes as visual–verbal jokes. International Journal of Communication, 10, 660–688. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/4101/1556

- Eisewicht, P., Steinmann, N., & Kortmann, P. (2021). The global corona pandemic in the mirror of personal postings-platform-related modes of communication in social media. OZS, Osterreichische Zeitschrift fur Soziologie, 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11614-021-00465-w

- Fuller, M. (2008). Introduction. In M. Fuller (Ed.), Software studies: A lexicon (pp. 1–14). MIT Press.

- Hannah, M. (2021). QAnon and the information dark age. First Monday, 26(2), https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v26i2.10868

- Heiskanen, B. (2017). Meme-ing electoral participation. European Journal of American Studies, 12(2), 12–12. https://doi.org/10.4000/ejas.12158

- Herring, S. (2003). Gender and power in on–line communication. In J. Holmes, & M. Meyerhoff (Eds.), The handbook of language and gender (pp. 202–228). Blackwell.

- Heylighen, F. (1996). Evolution of Memes on the Network. In G. Stocker & C. Schspf (Eds.), Ars electronica festival 96 (pp. 48–57). Springer.

- Hristova, S. (2014). Occupy wall street meets occupy Iraq: On remembering and forgetting in a digital age. Radical History Review, 117, 83–97. https://doi.org/10.1215/01636545-2210473

- Jenkins, H. (2006). Convergence culture: Where old and new media collide. New York University Press.

- Jenkins, H., Ford, S., & Green, J. (2018). Spreadable media. New York University Press.

- King, G., & Persily, N. (2019, January 9). Update from Gary King and Nate Persily, Social Science One blog. Accessed November 14, 2022, https://socialscience.one/blog/.

- Klug, D. (2020). "It took me almost 30 minutes to practice this". Performance and production practices in dance challenge videos on TikTok. arXiv preprint, 1–29. https://doi.org/10.33767/osf.io/j8u9v

- Knobel, M., & Lankshear, C. (2005). Memes and affinities: Cultural replication and literacy education. Paper presented to the annual national Reading conference, Miami, Florida, 30 November.

- Knobel, M., & Lankshear, C. (2007). Online memes, affinities and cultural production. In M. Knoble, & C. Lankshear (Eds.), A new literacies sampler (pp. 199–228). Peter Lang.

- Knuttila, L. (2011). User unknown: 4chan, anonymity and contingency. First Monday, 16(10), https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v16i10.3665

- Kumar, K., & Varier, V. (2020). To meme or not to meme: The contribution of anti–memes to humour in the digital space. Language@Internet, 18, article 3, https://www.languageatinternet.org/articles/2020/kumar.

- Lee, S. Y., & Hoh, J. W. (2021). A critical examination of ageism in memes and the role of meme factories. New Media & Society, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448211047845

- Literat, I., & Kligler-Vilenchik, N. (2019). Youth collective political expression on social media: The role of affordances and memetic dimensions for voicing political views. New Media & Society, 21(9), 1988–2009. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444819837571

- Lugea, J. (2019). The pragma–stylistics of ‘image macro’ internet memes. In H. Ringrow, & S. Pihlaja (Eds.), Contemporary media stylistics (pp. 81–106). Bloomsbury.

- Lunenfeld, P. (2014). Barking at memetics: The rant that wasn’t. Journal of Visual Culture, 13(3), 253–256. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470412914544517

- Marrazzo, F. (2022). Doing research with online platforms: An emerging issue network. In G. Punziano & A. Delli Paoli (Eds.), Handbook of research on advanced research methodologies for a digital society (pp. 65–86). IGI Global.

- McKelvey, F., DeJong, S., & Frenzel, J. (2021). Memes, scenes and #ELXN2019s: How partisans make memes during elections. New Media & Society, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448211020690

- Medina Serrano, J. C., Papakyriakopoulos, O., & Hegelich, S. (2020). Dancing to the partisan beat: a first analysis of political communication on TikTok. In 12th ACM Conference on web Science (pp. 257–266). https://doi.org/10.1145/3394231.3397916.

- Milner, R. (2016). The world made meme: Public conversations and participatory media. MIT Press.

- Milner, R. M. (2013). Pop polyvocality: Internet memes, public participation, and the occupy wall street movement. International Journal of Communication, 7.

- Miltner, K. M. (2014). “There’s no place for lulz on LOLCats”: The role of genre, gender, and group identity in the interpretation and enjoyment of an Internet meme. First Monday, 19(8), https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v19i8.5391

- Miltner, K. M. (2018). Internet memes. In J. Burgess, A. Marwick, & T. Poell (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of social media (pp. 412–428). Sage Publications Ltd.

- Mina, A. X. (2019). Memes to movements: How the world's most viral media is changing social protest and power. Beacon Press.

- Nagle, A. (2017). Kill all normies. John Hunt.

- Niederer, S. (2018). Networked images: Visual methodologies for the digital age. Hogeschool van Amsterdam.

- Niederer, S., & Van Dijck, J. (2010). Wisdom of the crowd or technicity of content? Wikipedia as a sociotechnical system. New Media & Society, 12(8), 1368–1387. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444810365297

- Nissenbaum, A., & Shifman, L. (2017). Internet memes as contested cultural capital: The case of 4chan’s /b/ board. New Media & Society, 19(4), 483–501. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444815609313

- Nissenbaum, A., & Shifman, L. (2018). Meme templates as expressive repertoires in a globalizing world: A cross–linguistic study. Journal of Computer–Mediated Communication, 23(5), 294–310. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcmc/zmy016

- Pelletier-Gagnon, J., & Pérez Trujillo Diniz, A. (2021). Colonizing Pepe: Internet memes as cyberplaces. Space and Culture, 24(1), 4–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/1206331218776188

- Pettis, B. T. (2021). Know Your Meme and the homogenization of web history. Internet Histories, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/24701475.2021.1968657

- Phillips, W., & Milner, R. M. (2018). The ambivalent internet: Mischief, oddity, and antagonism online. John Wiley.

- Quandt, T. (2018). Dark participation. Media and Communication, 6(4), 36–48. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v6i4.1519

- Rocketboom. (2008). Know your meme. webpage, 24 July, https://web.archive.org/web/20080724175858/http://rocketboom.wikia.com/wiki/Know_Your_Meme.

- Sampson, T. (2012). Virality: Contagion theory in the age of networks. University of Minnesota Press.

- Sánchez–Olmos, C., & Suárez, E. V. (2017). The musicless music video as a spreadable meme video: Format, user interaction, and meaning on YouTube. International Journal of Communication, 11, 3634–3654. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/6410

- Schellewald, A. (2021). An enhanced method of contactless charging of railway signaling torch light. International Journal of Communications, 15(6), 21–25. https://doi.org/10.46300/9107.2021.15.5

- Schlaile, M. P. (2021). Meme wars’: A brief overview of memetics and some essential context. In M. P. Schlaile (Ed.), Memetics and evolutionary economics (pp. 15–32). Springer.

- Sharma, H. (2018). Memes in digital culture and their role in marketing and communication: A study in India. Interactions: Studies in Communication and Culture, 9(3), 303–318. https://doi.org/10.1386/iscc.9.3.303_1

- Shifman, L. (2013). Memes in a digital world: Reconciling with a conceptual troublemaker. Journal of Computer–Mediated Communication, 18(3), 362–377. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12013

- Shifman, L. (2014). Memes in digital culture. MIT Press.

- Silva, P. D. D., & Garcia, J. L. (2012). YouTubers as satirists: Humour and remix in online video. JeDEM - EJournal of EDemocracy and Open Government, 4(1), 89–114. https://doi.org/10.29379/jedem.v4i1.95

- SimilarWeb. (2022). imgur.com Ranking, https://www.similarweb.com/website/imgur.com/#overview

- Tuters, M. (2018). LARPing & liberal tears. Irony, belief and idiocy in the deep vernacular web. In M. Fielitz, & N. Thurston (Eds.), Post–digital cultures of the far right (pp. 37–48). Transcript Verlag.

- Tuters, M. (2021). Why meme magic is real but memes are not. In J. Galle (Ed.), Memenesia (pp. 46–59). V2_Publishing.

- Tuters, M., & Hagen, S. (2020). (They) rule: Memetic antagonism and nebulous othering on 4chan. New Media & Society, 22(12), 2218–2237. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444819888746

- Vada, Ø. (2015). What happened to memetics? Emergence: Complexity & Organization, 17(2), 1–5.

- Van Dijck, J. (2013). The culture of connectivity: A critical history of social media. Oxford University Press.

- Vickery, J. R. (2014). The curious case of confession bear: The reappropriation of online macro–image memes. Information, Communication & Society, 17(3), 301–325. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2013.871056

- Vizcaíno–Verdú, A., & Abidin, C. (2021). Cross–cultural storytelling approaches in TikTok’s music challenges. AoIR Selected Papers of Internet Research, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.5210/spir.v2021i0.12260

- Weimann, G., & Masri, N. (2020). Research note: Spreading hate on TikTok. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2020.1780027

- Wiggins, B. E. (2019). The discursive power of memes in digital culture. Routledge.

- Wiggins, B. E., & Bowers, G. B. (2015). Memes as genre: A structurational analysis of the memescape. New Media & Society, 17(11), 1886–1906. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444814535194

- Woods, H. S., & Hahner, L. A. (2019). Make America meme again: The rhetoric of the Alt-right. Peter Lang.

- Yoon, I. J. (2016). Why is it not just a joke? Analysis of internet memes associated with racism and hidden ideology of colorblindness. Journal of Cultural Research in Art Education, 33, 92–123. https://doi.org/10.2458/jcrae.4898

- Yus, F. (2018). Identity–related issues in meme communication. Internet Pragmatics, 1(1), 113–133. https://doi.org/10.1075/ip.00006.yus

- Yus, F. (2021). Pragmatics, humour and the internet. Internet Pragmatics, 4(1), 131–149. https://doi.org/10.1075/ip.00058.yus

- Zannettou, S., Caulfield, T., Blackburn, J., De Cristofaro, E., Sirivianos, M., Stringhini, G., & Suarez-Tangil, G. (2018). On the origins of memes by means of fringe web communities. Proceedings of the Internet Measurement Conference 2018, 188–202. https://doi.org/10.1145/3278532.3278550

- Zulli, D., & Zulli, D. J. (2020). Extending the Internet meme: Conceptualizing technological mimesis and imitation publics on the TikTok platform. New Media & Society. Online First, https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820983603