ABSTRACT

While government regulators, the press, and academics struggle to determine who should be responsible for content on social media platforms, we know little about what the public believes about these issues. In this study, we investigate what drives Americans’ opinions on whether the government, platforms, or individual users should be responsible for social media content. Using data from a nationally representative survey of over 10,000 Americans, we investigate how anti-establishment attitudes relate to who Americans believe should be responsible for content on social media. We also examine the role of beliefs in the government’s role in the market, free speech beliefs, and beliefs in individual responsibility in this context. Among other findings, we show how anti-establishment beliefs and beliefs in individual responsibility may drive people to put the onus on individual users to bear the responsibility for online content. Theoretically, our study contributes to the ongoing discussion in sociology and political science that partisanship alone is not sufficient for explaining American public opinion. Practically, this study contributes to the ongoing public discussion around content moderation and related policies.

Over 50% of Americans get some of their news from social media, making social media platforms an increasingly important part of how citizens find and interpret information in democracies (Knight Foundation, Citation2022; Shearer, Citation2021). While the decision-making practices of the press are well-documented and relatively professionalized, the content moderation practices of social media platforms are less understood and shift constantly (Barrett & Kreiss, Citation2019). How social media platforms are governed – and how content on them is moderated – is still hotly contested and varies drastically across countries. European governmental regimes have begun to regulate content on social media like hate speech and disinformation (e.g., the Digital Services Act) (Nenadić, Citation2019), while US law still leaves all moderation decisions up to the platforms themselves (Morar, Citation2022; Smith & Alstyne, Citation2021). Often referred to as the ‘26 words that created the Internet (Kosseff, Citation2019),’ section 230 of the Communications Decency Act (CDA) provides online platforms with immunity from liability for online content. While both US parties recently have wanted to change Section 230, the Democratic Party has asked for more content moderation while the Republican Party claims to want less content moderation. Nonetheless, we know surprisingly little about the public’s attitudes towards social media content regulation.

The public’s opinion on these issues matters. While much of the public discourse surrounding platforms evolves at a policy level between think tanks, journalists, academics and political actors, public opinion is a political actor itself in the public sphere (Herbst, Citation2001; Krippendorff, Citation2005). Aware of the influence of public opinion, actors such as interest groups, political parties, and economic elites work to shape public opinion (see, e.g., McGregor, Citation2020; Smith, Citation2000). Public opinion shapes collective behaviors, which can include protests, petitions, lobbies, money flows, and so on (Krippendorff, Citation2005).

Content moderation – ‘a set of practices used by social media platforms to enforce their guidelines on acceptable content (Ganesh & Bright, Citation2020, p. 8)’ – directly affects what types of content reach people and what people say and do on social media because online content spills over the civic and political lives of people in real life. This online content can then become a powerful representation of public opinion (McGregor, Citation2019). When discussing the governance of social media platforms, at stake are essential democratic values, including freedom of expression, political participation, and equitable governance that considers marginalized and more vulnerable communities. The extent to which people enjoy freedom of expression and use social media platforms as means of political and social participation is shaped by the way digital platforms are governed – and by whom. Given all of this, content moderation scholarship faces an urgent challenge to conduct studies that would directly inform policy around online content governance (Gillespie et al., Citation2020).

Thus, the aim of this study was to take a more nuanced approach to understanding Americans’ opinion about governing online content by going beyond the oft-taken partisan explanation. We were especially interested in investigating how beliefs in American democracy relate to support for different social media governance models when combined with political ideology. To do so, first, we examined the relationship of anti-establishment beliefs on Americans’ opinions regarding whether the government, platforms, or individual users should be responsible for online content. Then, we further explored how beliefs in the government’s economic role in the market, beliefs in free speech, and beliefs in individual responsibility were related to Americans’ thoughts about government regulation of online content. In this paper, we use the term ‘governance’ to refer to any and all modes of governing online content regardless of the actor. we use the term ‘regulation’ only when the actor of the governance is the government and the term ‘content moderation’ only when the actor is social media companies. We use the term ‘individual responsibility’ when referring to leaving online content governance to the users themselves.Footnote1

The contributions of this study are both theoretical and practical. Theoretically, this study contributes to enhancing public opinion theory by focusing on anti-establishment beliefs and how they interact with political ideology when people form opinions around online content governance. We argue that including anti-establishment beliefs as a dimension of public opinion in theoretical models can contribute to better understanding Americans’ decision to support different policies. Practically, this research contributes to our understanding of public opinion on a topic currently being debated across the globe, across all levels of government. Specifically, this research furthers our understanding as to what drives these opinions, and in doing so, provides us with practical guidance as to why some people prefer government regulation, platform moderation, or no intervention at all. This focus is paramount to understanding public opinion as well as informing policy (in both governments and within platforms). Our study contributes to the scholarly debate and public discussion around platform governance and content moderation, as well as the emerging literature that examines anti-establishment beliefs as an essential dimension of public opinion.

The American public and online content moderation

Given the dominance of US digital platforms in the global market and their growing influence upon politics in the US, we see the US as an interesting study site to examine how different beliefs relate to support for different governance models for online content. Global technology companies’ content moderation efforts are heavily influenced by public discourse in the US. For example, despite that more than 90% of Facebook’s monthly active users live outside North America, 87% of Facebook employees’ working hours on content moderation went to posts in the US (Tworek, Citation2021). A recent report (Bateman et al., Citation2021) also pointed out that “American U.S. values, norms, and legal traditions of governing speech and harm have an outsized influence on online discourse throughout the world,” a finding based on their analysis of community standards from thirteen social media and messaging platforms compiled by the Partnership for Countering Influence Operations (PCIO).Footnote2

American public opinion around online content governance and who should be responsible for it is complicated. In 2020, Americans were equally divided among those who favor (50%) and oppose (49%) government intervention that would require internet and technology companies to break into smaller companies (Knight Foundation & Gallup, Citation2020). Pew Research Center conducted a similar study and found that Americans were divided – 55% supported government regulation while 42% opposed it (Auxier, Citation2020). Still – 47% of Americans agreed that major tech companies should be regulated by the government more than they are now (Auxier, Citation2020).

Though there is not resounding support for government intervention, Americans are even less keen on tech companies’ efforts to self-regulate. More than 70% of Americans have little or no confidence in tech companies to prevent misuses of their platforms in elections or to determine which posts should be labeled inaccurate (Auxier, Citation2020). At the same time, a similar share of Americans also believe tech companies do have some responsibility to prevent misuses on their platforms (Auxier, Citation2020). The public divide on governance and responsibility around online content clearly requires more scrutiny. We know relatively little as to what factors may impact these divides. A recent report shows partisanship is not a major driver (Knight Foundation, Citation2022). Given this, we focus on other aspects of political beliefs. In moving beyond partisanship, we focus on the role of anti-establishment beliefs in shaping Americans’ opinions about who should be responsible for online content.

Looking into the public opinion after a national crisis is especially valuable as it is when the issue at hand is salient in the public’s mind. In this sense, the data used in this study is particularly useful as the survey was fielded the summer after the attack on the Capitol on January 6th, 2021. Following this incident, Facebook, Twitter, and other tech companies took the unprecedented step of banning a sitting US president from their platforms. Since that day, Republican state legislators in more than half of the country have introduced a wave of bills that impose an array of punishments and prohibitions on tech platforms that attempt to remove content or ban individual users (Lapowsky, Citation2022). Although this study limits its scope to the US, the findings have implications beyond the United States regarding how different beliefs may play out in people’s decision to support different types of governance models for online content.

Three models for dealing with online content: government, social media companies, and individuals

While there is obvious disagreement on what types of content should be online, the preeminent question is exactly who should be responsible for the governance of this content. People are generally divided in their opinions around responsibility for the social and political role of platforms (Helberger et al., Citation2018). Usually, these opinions focus on who is the most responsible for online content among the following three actors (Gorwa, Citation2019): the government (as the entity responsible for setting the overall ground rules and protecting its citizens’ rights in a democratic society), social media companies (as architects and managers of the online environments), and individual users (as individuals making their own decisions about their behavior in an online environment). In reality, these three modes of governance are mixed, with users themselves flagging, reporting, and blocking harmful content voluntarily, while social media companies update content moderation policies as governments introduce new regulations around these practices. Nonetheless, it is important to recognize whether the public thinks having users be responsible for online content is ideal, considering the unfair and unequal labor imposed on marginalized communities (Roberts, Citation2019). Moreover, the resistance to government regulation and content moderation among some individuals may reflect a broader anti-elite struggle, which further complicates the landscape of online content governance.

We have limited knowledge about which of these governance strategies the public supports, and even less understanding of why so. One exception is a recent study that examines the antecedents of support for content moderation and platform regulation (Riedl et al., Citation2022). Riedl and colleagues found that older age, more frequent social media use, and a higher perception that censorship was done intentionally all led to higher support for increased government regulation of social media platforms, while trust in social media platforms and opposition to censorship led to lower support for government regulation. They also found that older and more educated people, with higher perceived effects of online content on others and less opposition to censorship, espoused greater support for content moderation. Most notably, attitudes about censorship were the largest drivers of people’s opinions, outweighing even the impact of partisanship (Riedl et al., Citation2022).

Though this work did not seek to determine whether the public prefers government regulation or content moderation, it has important implications for our own study. Attitudes about censorship seem to trump or subsume partisanship. Echoing a recent Knight/Gallup report (2022), if partisanship doesn’t explain regulation opinions, then what does? Our study examines the roles that anti-establishment beliefs, beliefs about the government’s role in the market, and attitudes about free speech and individual responsibility play in people’s preferences for various models of platform governance.

Anti-establishment beliefs as a dimension of public opinion

Researchers have underlined the importance of studying anti-establishment beliefs as a core dimension of public opinion, moving beyond left-right orientations (Uscinski et al., Citation2021). Anti-establishment beliefs can be defined as ‘the rhetorical appeal used in opposition to the elites’ or ‘opposition to those wielding power’ (Barr, Citation2009). Anti-establishment beliefs do not fit within the left-right conceptualization of public opinion as they span left-right identities (Lacatus, Citation2019; Uscinski et al., Citation2021). Given that partisanship is not a primary driver for ascribing responsibility of content online – and that technology companies face a bipartisan backlash – we suspect anti-establishment beliefs may help explain support for various regulatory models.

Research on dimensions of public opinion outside of the left-right orientation have slowly increased over the past decade, including studies on conspiracy beliefs (Douglas et al., Citation2019; Krouwel et al., Citation2017), populistic beliefs (e.g., Erisen et al., Citation2021), and Manichean thinking (e.g., Selçuk, Citation2016). These orientations share anti-establishment beliefs as a fundamental element.

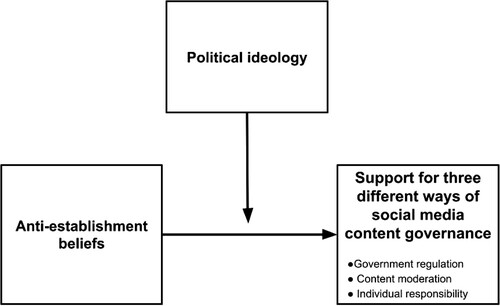

Content moderation efforts on social media and anti-establishment orientations, including conspiracy thinking and populism, are intrinsically linked. In recent years, Facebook (Albert, Citation2020), Twitter (Cohen, Citation2020), and YouTube (Brito, Citation2020) have taken action against QAnon-related groups and accounts. In fact, in the US, the most difficult content moderation problems commonly stem from anti-establishment conspiracies, such as those centered around COVID-19 (e.g., NPR, Citation2021) or the 2020 US presidential election (e.g., Frenkel, Citation2020). Given this, we adapt Uscinski and colleagues’ (Citation2021) model of mass opinion to conceptualize public opinion along two dimensions: anti-establishment beliefs and political ideology. Uscinski et al.’s (Citation2021) model included left-right orientation and anti-establishment beliefs as orthogonal dimensions of public opinion. In adapting these same dimensions, we take a novel approach to conceptualizing public opinion about responsibility for online content.

Below a series of hypotheses stem from our overarching question: Can anti-establishment beliefs explain support for different policies regarding online content?

H1: Stronger anti-establishment beliefs decrease the likelihood of supporting government regulation of online content.

H2: Stronger anti-establishment beliefs increase support for supporting individual responsibility when it comes to online content.

H3: Anti-establishment beliefs will relate to support for content moderation.

Given widening partisan views on the roles of different actors in platform governance, we hypothesize that political ideology will moderate anti-establishment beliefs in shaping support for different models of handling online content ().

H4: Political ideology will moderate the strength of the relationship between anti-establishment beliefs and support for (a) government regulation, (b) individual responsibility, and (c) content moderation.

Belief in the government’s role in the market

Another way to think beyond partisanship is to examine attitudes about the role of the government. Given that anti-establishment beliefs are – at the core – about a relational orientation between an individual and society, we also examine attitudes about the economic role of government in a democratic society. On the one hand, the entities involved in social media and other online content are massive companies. On the other hand, those most impacted by decisions around social media and online content are individuals. As such, we specifically examine attitudes about the economic role of the government in the market: is the government’s role to protect companies or to protect individuals?

Though American public opinion has consistently been divided between the preference for a reduced government role and that of an extended one (Jones, Citation2021), either way, people expect the government to play a role in economic functions. Although individuals make most economic decisions in market economies like the US, the government still serves several roles. For instance, the government is a key actor that maintains competition in the market, stabilizes the economy when needed, and provides public goods and services.

Considering governments’ regulation policies have a significant impact on the economy (Li & Maskin, Citation2021), people’s belief in the government’s economic role in the market may shape support for government regulation on online content. Recent polling demonstrates that views on internet regulation go beyond partisan differences, including six different opinion segments identified through their different views on democracy, society, and technology (Knight Foundation, Citation2022).

In democratic societies, governments play a role in ensuring citizen participation, free and fair elections, economic freedom, a free press, equality, and human rights, while also curbing the abuse of power. Although Americans share a general consensus on the democratic values that are essential for the country (Knight Foundation, Citation2022), there are also certain values on which Americans are relatively divided (Pew Research Center, Citation2018). The role of the government in ensuring economic freedom takes opposing values: does economic freedom stem from promoting a free and open market or from providing aid to those who need it to participate in the market? Americans are likely to be divided on the government’s role in providing welfareFootnote3 and supporting an open market, as they reflect competing values (Jones, Citation2021). We hypothesize that support for government regulation of online content will be associated with how people think of the role of government in the market. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H5: Beliefs about the government’s economic role in the market will be related to support for government regulation of online content. The more one believes the government’s role is to provide aid to those who need it, the greater their likelihood of supporting government regulation of online content (H5a). The more one believes the government’s role is to promote a free and open market, the smaller their likelihood of supporting government regulation of online content (H5b).

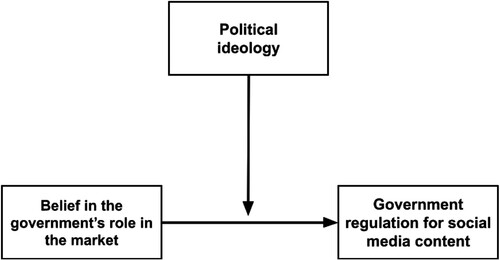

Figure 2. A conceptual model for the relationship between belief in the government’s role in the market and support for government regulation with political ideology as the moderator.

H6: Political ideology will moderate the strength of the relationship between beliefs about the government’s economic role in the market and support for government regulation of online content.

Explaining the opposition to government regulations

Lastly, we provide an exploratory regression analysis on which factors influence anti-government regulation attitudes regarding online content. The two factors we investigated were free speech beliefs and beliefs in individual responsibility. Beliefs about free speech and individual responsibility of online content may both explain anti-government regulation attitudes. Americans’ free speech beliefs are complicated and cannot be solely explained by partisanship (Ekins, Citation2017). For example, Ekins (Citation2017) showed that views about hate speech are divided even among those with the same political ideology. A large majority of Americans (82%) believe that banning hate speech would be difficult because of people’s disagreement on what constitutes hate speech (Ekins, Citation2017). On the other hand, beliefs in individual responsibility refer to people’s tendency to think of online content as a product solely managed and taken care of by the individual as a creator and/or a user. These two beliefs point to different directions – free speech beliefs focus on claims based on the U.S. Constitution (even when the First Amendment is interpreted poorly), while beliefs in individual responsibility move away from these claims. Hence, we propose an open research question:

RQ1: To what extent do free speech beliefs and beliefs in individual responsibility explain anti-government regulation attitudes?

Method

Participants and data collection

This study used data from a Gallup Panel, which was distributed through mail and web, between 30 July and 26 August 2021. The panel is a probability-based panel of US adults, selected by Gallup randomly using both address-based sampling and dual-frame random-digit dialing phone interviews. The dataset used in this study was completed by 10,226 adults in the US, aged 18 or older. The AAPOR5 response rate is 22%.

We weighted the sample using weights provided by Gallup, which corrected for unequal selection probability and nonresponses. Weighting adjustments were made to ensure this sample matches the national demographics of gender, age, race, Hispanic ethnicity, education, and geographic region. These weighting targets are based on the 2019 Current Population Survey figures for US adults.

The questions used in this study – as well as those on the full instrument – were designed by both Gallup and The Knight Foundation, in consultation with academics. For more information on the sample, as well as the full questionnaire from which this study is drawn, see Media & Democracy: Unpacking America’s complex views on the digital public square (Citation2022).Footnote4

Dependent variables: supports for government regulation, content moderation, or individual responsibility

Support for government regulation (M = 0.38, SD = 0.49, range 0–1)

This variable was derived from the responses to a 5-point scale bipolar item,Footnote5 where 5 meant leaning more toward government regulation and 1 meant leaning more toward content moderation by social media companies. Because we wanted to identify the people that supported government regulation, the people who leaned more toward government regulation compared to content moderation were coded as 1. Participants who had no preference or leaned more toward content moderation were coded as 0, which meant they were not supporters of government regulation.

Support for content moderation (M = 1.87, SD = 1.17, range 0–4)

This variable was derived from responses to four sets of items presented as bipolar pairs to the participants. All items included a bipolar pair on a 5-point so that the minimum and maximum scores on the 5-point scale referred to strong preference for different policies. We recoded all pairs of items so that each dummy variable reflected preference to one policy. See for the recoding process for this variable. We added the four binary variables to come up with an index score that ranges between 0 and 4.

Table 1. Recoding support for content moderation.

Support for individual responsibility (M = 1.08, SD = 1.08, range 0–3)

This variable was derived from responses to three sets of items presented as bipolar pairs to the participants. All items included a bipolar pair so that the minimum and maximum scores on the 5-point scale referred to strong preference for different policies. We recoded all pairs of items so that each dummy variable reflected preference to one policy. See for the recoding process for this variable. We added the three binary variables to come up with an index score that ranges between 0 and 3.

Table 2. Recoding support for individual responsibility.

Anti-government regulation (M = 2.97, SD = 1.21, range = 1–5)

This item was the reverse of support for government regulation and was measured on a 5-point Likert scale. As a result, a higher score meant higher anti-government regulation attitudes.

Independent variables

Anti-establishment beliefs (M = 3.47, SD = 0.90, range 1–5)

This variable was the average of the following two items: ‘Even though we elect our leaders, a few people will always run things.’ and ‘Official government explanations of events cannot be trusted.’ The first item fell into the conspiracy dimension of anti-establishment beliefs, while the second fell into the populism dimension of anti-establishment beliefs (Uscinski et al., Citation2021). Both items were asked on a 5-point Likert scale. The Pearson correlation coefficient for these two items was r = 0.366 (p < .001).

Belief in the government’s role in the market (M = −0.14, SD = 1.61, range −4 to +4)

In order to measure this variable, participants were asked to rate the following two items: ‘The government provides aid for those who need it’ and ‘The government promotes a free and open market’ on a 5-point Likert scale.Footnote6 Then, we subtracted the latter item from the former item so that a higher score would indicate more support toward government welfare whereas a lower score would indicate more support toward the open market.

Political ideology (M = 3.86, SD = 1.75, range = 1–7)

Participants were asked the following item to measure their political views: ‘How would you describe your political views?’ This item was asked on a 7-point scale, which ranged from extremely liberal to extremely conservative. The higher the scores, the closer the participants placed their political views as conservative.

Free speech beliefs (M = 1.17, SD = 0.86, range = 1–5)

This variable was the average of the following two items: ‘People should have the freedom to say whatever they want online (reverse-coded from a bipolar pair, where the preference for this item was closer to 1).’ and ‘Censorship online is a more serious problem than fake news.’ Participants were asked these two questions on a 5-point Likert scale. Pearson correlation coefficient for these two items was r = 0.351 (p < .001).

Beliefs in individual responsibility (M = 2.94, SD = 0.22, range = 1–5)

Beliefs in individual responsibility vis-à-vis online content were the average of two items: ‘Social media users alone should be responsible for the content they post online’ and ‘People should have the freedom to say whatever they want online’ – both asked on a 5-point Likert scale. The Pearson correlation coefficient for these two items was r = 0.528 (p < .001).

Covariates

All covariates were not directly asked to participants in the instrument, as they were set from Panel as embedded data. One exception was internet use, which was asked as part of the instrument. When we needed a dummy variable to conduct the moderation regression analyses, we recoded the covariate so that a certain category took the value of 1 while the other took the value of 0.

Sex

Sex initially included two categories: male (48%) and female (52%). We recoded sex as a dummy variable so that female took the value of 1 while male took the value of 0.

Age

Age was a categorical variable that included three categories. Ages 18–34 took the value of 1 (29.9%), ages 35–54 took the value of 2 (33.0%), and ages over 55 took the value of 3 (37.1%).

Race

The original dataset included five race categories: White (66.3%), Hispanic (17.0%), Black (12.6%), Asian (1.9%), and other (2.3%). We recoded race as a dummy variable so that white took the value of 1 (66.0%), and non-white took the value of 0 (33.8%). 0.2% were missing values.

Education

Education initially included nine categories: less than a high school diploma (3.4%), high school graduate (33.6%), technical/trade/vocational/business school or program after high school (3.0%), some college (14.9%), two-year associate degree (10.1%), four-your bachelor’s degree (16.9%), some postgraduate or professional school (4.2%), postgraduate or professional degree (13.9%), and don’t know (0%). For education, we used a dummy variable where college graduates took the value of 1 (44.7%) while non-college graduates took the value of 0 (54.5%). 0.8% were missing values.

Internet use

Internet use was measured with a single item that asked the following question: How often do you use the internet? The item was asked on a 5-point Likert scale, where 1 meant Never and 5 meant Daily (M = 4.85, SD = 0.63, range 1–5).

Results

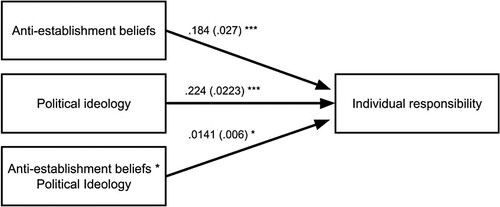

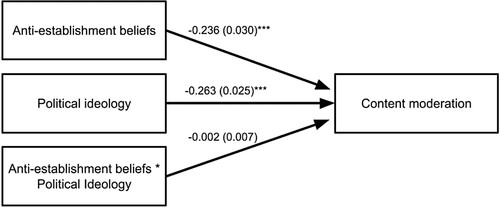

Our first set of hypotheses examined the direct relationship between anti-establishment beliefs and the three models for handling online content: government regulation, platform moderation, and individual responsibility. (). After controlling for race, education, gender, internet use, age, and ideology,Footnote7 we find that anti-establishment beliefs make one significantly less likely to support government regulation of online content (exp. B = .896, p < .001). (See and ). An OLS model controlling for race, education, gender, internet use, age, and ideology shows that anti-establishment beliefs are positively and significantly related to one’s belief in individual responsibility (beta = .184, p < .001) – explaining an additional 3% of variance in the dependent variable. (See and ). Finally, controlling for the same covariates as above, we find that anti-establishment beliefs are significantly and negatively related to support for social media company content moderation (beta = −.236, p < .001) – explaining an additional 2.6% of variance in the dependent variable. (See ).

Table 3. Correlations among and descriptive statistics for all variables.

Table 4. Regression model testing the relationship between anti-establishment attitudes and support for government regulation of social media content (Model 1, H1) and the moderating effect of political ideology (Model 2, H4a).

Table 5. Conditional effects model of anti-establishment attitudes on support for government regulation of social media content at values of the moderator (Political Ideology) (H4a).

Table 6. OLS regression model testing the relationship between anti-establishment beliefs and support for individual responsibility for social media content (Model 1, H2) and the moderating effect of political ideology (Model 2, H4b).

Table 7. Conditional effects model of anti-establishment attitudes on support for individual responsibility for social media content at values of the moderator (Political Ideology) (H4b).

Table 8. Regression model testing the relationship between anti-establishment beliefs and support for social media company responsibility for social media content (Model 1, H3) and the moderating effect of political ideology (Model 2, H4c).

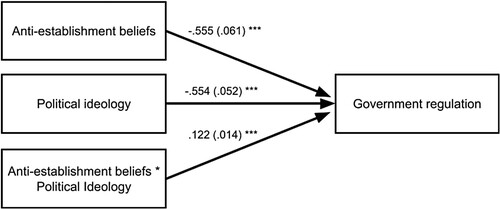

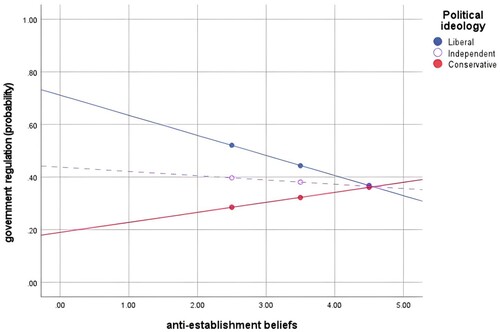

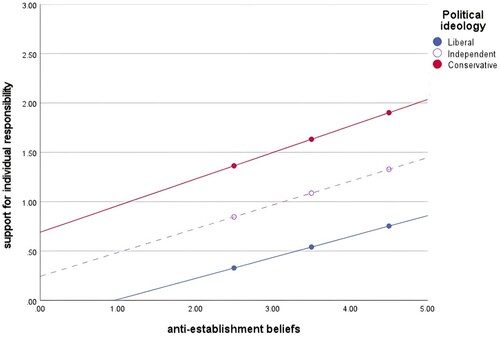

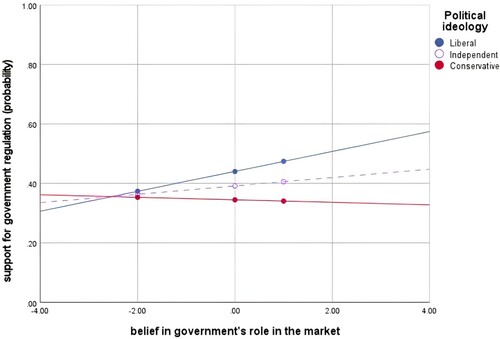

Our next set of hypotheses examined the moderating role of political ideology in the previously described relationships. When it comes to support for government regulation (H4a), the role of anti-establishment beliefs on such support is contingent on one’s ideology (). Those with low anti-establishment beliefs vary greatly, due to their ideology, on their support for government regulation of social media companies – with liberals supporting government regulation and conservatives not. However, those with the highest levels of anti-establishment beliefs converge on a low likelihood of supporting government regulation – no matter their ideology. See (conditional effects) and (probabilistic interaction graphed). Moving to support for individual responsibility online (H4b), we again find that ideology and anti-establishment beliefs work in concert to explain such support (). For liberals, moderates, and conservatives – the stronger one’s anti-establishment beliefs, the greater their support for the individual responsibility model. See (conditional effects) and (interaction graphed). Finally, we do not find that political ideology moderates the relationship between anti-establishment beliefs and support for content moderation (H4c) (). See .

Figure 3. A statistical model for the moderation analysis examining the relationship between anti-establishment beliefs and support for government regulation with political ideology as the moderator.

Note: Unstandardized coefficients of the model are reported with standard errors in parentheses. Covariates included age, gender, race, education, and internet use. Model summary: −2LL 12596.73, ModelLL 328.62, p < .001. Model goodness of ft: χ2 =74.915; df =1, p < .001; pseudo R2= 4.7%.

Figure 4. Conditional effects of anti-establishment attitudes on support for government regulation at different values of the moderator (political ideology).

Figure 5. A statistical model for the moderation analysis examining the relationship between anti-establishment beliefs and support for individual responsibility with political ideology as the moderator.

Note: Unstandardized coefficients of the model are reported with standard errors in parentheses. Covariates included age, gender, race, education, and internet use. Model summary: R2 31%, F(8,9231) = 518.50, p < .001. R2 change for unconditional interaction = 0.04%, F(1,9231) = 5.1836, p = 0.23.

Figure 6. Conditional effects of anti-establishment attitudes on support for individual responsibility at different values of the moderator (political ideology).

Figure 7. A statistical model for the moderation analysis examining the relationship between anti-establishment beliefs and support for social media companies’ content moderation with political ideology as the moderator.

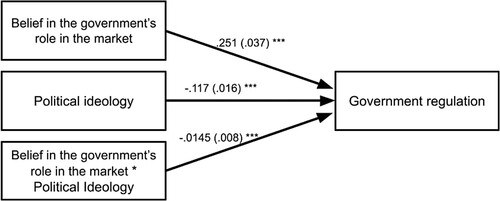

Our next set of hypotheses examined the relationship between Americans’ beliefs in the government’s economic role in the market and support for government regulation of social media (). After controlling for race, education, gender, internet use, age, and ideology, we find that a net belief about the role of a government to support the welfare of all citizens makes one significantly more likely to support government regulation of online content (exp. B = 1.082, p < .001). (See ). Overall, this model explains ∼ 3.7% of the variance in the DV (significantly more than the previous model without beliefs about the government’s economic role in the market). H5 suggested political ideology would moderate the relationship between the government’s economic role in the market and the support for government regulation on online content (). The interaction is significant, showing conditional effects for liberals and moderates, but not for conservatives. See .

Figure 8. A statistical model for the moderation analysis examining the relationship between belief in the government’s role in the market and support for government regulation with political ideology as the moderator.

Figure 9. Conditional effects of belief in the government’s role in the market on support for government regulation at different values of the moderator (political ideology).

Table 9. Regression model testing the relationship between beliefs in the role of government and support for government regulation of social media content (Model 1, H5) and the moderating effect of political ideology (Model 2, H6).

Table 10. Conditional effects model of beliefs in the role of government on support for government regulation of social media content at values of the moderator (political ideology).

Lastly, we address our research question: To what extent do free speech beliefs and beliefs in individual responsibility explain anti-government regulation attitudes? After controlling for race, education, gender, internet use, age, and ideology, we find that both free speech beliefs (beta = .041, p = .004) and beliefs in individual responsibility (beta = .221, p < .001) are significantly and positively related to anti-government regulation attitudes. Beyond the covariates, beliefs in individual responsibility explains an additional 3.5% of variance in the DV, while free speech beliefs only explain .1% more. See .

Table 11. Comparison between different models for RQ3.

Discussion

In this study, we examined how political attitudes – beyond partisanship – shape Americans’ attribution of responsibility regarding online content. The ubiquity of online spaces – coupled with the fact that many people are not very politically interested and lack strong partisan ties, led us to believe that partisanship alone may not drive Americans’ thoughts about to whom the responsibility for the management of online content belongs. And yet, decisions about the handling of online content – from the problematic to the democratic – impact nearly all Americans directly. Instead, we examined the multi-dimensional nature of anti-establishment beliefs and political ideology in shaping American’s attitudes about who bears the responsibility for online content. Our study shows that political ideology alone does not explain Americans’ attribution of responsibility for online content, and thus, their support for different forms of social media content governance. Anti-establishment beliefs and political ideology together display meaningful interaction effects regarding Americans’ thoughts around the responsibility of different actors for social media and other online content. Our study confirms the important role those anti-establishment beliefs play as a dimension of public opinion – one that requires scholarly and public attention when discussing social media governance and policy.

We probed three possibilities of the public’s support for different actors regarding the governance of social media and other online content: the government, social media companies, and individual users. Unsurprisingly, those with anti-establishment beliefs are significantly less likely to support a model of government regulation and more supportive of individual responsibility. We also find that those with anti-establishment beliefs do not support social media companies themselves being responsible for content moderation, suggesting these individuals view technology companies as ‘the establishment.’ Furthermore, results showed that political ideology has a moderating effect in all models of support. No matter one’s ideology, those with high anti-establishment beliefs share little interest in government regulation of online content and much more support for individual responsibility online. Taken together, this further supports the idea that anti-establishment beliefs are a unique component of American public opinion shared by those across the ideological spectrum (Uscinski et al., Citation2021).

There is much to learn about anti-establishment beliefs. Researchers have just started unpacking the correlations anti-establishment beliefs have with several antisocial psychological traits, the acceptance of political violence, time spent on extremist social media platforms, support for populist candidates, and beliefs in misinformation and conspiracy theories (Uscinski et al., Citation2021). Furthermore, from Brexit to #StopTheSteal, social media platforms have been at the center of populist movements, many of which are undergirded by disinformation and conspiracies to which social media companies have struggled to respond effectively. Our findings suggest that not only do these beliefs lead people to oppose government regulation of online spaces, but also to oppose efforts by social media companies to moderate content. This suggests that online and social media companies are seen by anti-establishmentarians – from both the left and the right – as elite bodies and their platforms as one of the sites of anti-elite struggle.

At their root, anti-establishment beliefs are relational, reflecting a deep distrust between an individual and society. Taking a similarly relational turn, we examined how Americans’ attitudes about the government’s role in the market shape to whom they prefer to attribute responsibility for online content. Is the role of the US government to ensure companies, like social media companies, have a free market in which to participate or to ensure individuals’ ability to participate in the market through providing systems of support and aid? To address this, we introduce and test another dimension of public opinion – beliefs about the role of a democratic government (in our case, specifically in relation to the economy). For those who view individuals as more worthy of economic support than technology companies, government regulation is an appealing option – especially for liberals and moderates. Our result aligns with previous findings from Gallup surveys, which identified a shift toward favoring a more active government role in 2020 among Democrats and independents but not Republicans (Jones, Citation2021). Jones (Citation2021) also found that asking respondents to consider the trade-offs between taxes and government services can lead to more support in a limited government, so future work might consider investigating how different priming can lead to different results. Overall, given the recent democratic decline in the US, we suggest that probing Americans’ attitudes about the various functions in a democracy is a fruitful way to understand public opinion beyond anti-establishment beliefs and even mere partisanship.

Whereas beliefs about the economic role of the government in the market shape pro-government regulation beliefs, we also examine what shapes anti-government regulation beliefs. This interest stems from the anti-government and anti-elite heart of populist and extremist movements in both the US and around the world. The discourse around online content regulation at times surfaces free speech claims while at other times promoting individualistic ideas around responsibility. In probing the anti-government dimension, we find that individual responsibility trumps free speech. This suggests that those against government regulation are concerned less with protecting free speech for all and more driven by protecting their rights as an individual. Though one pillar of extremism is the belief that freedom of speech trumps all other freedoms – a particularly pernicious problem in the US as far-right movements have purposively misinterpreted and weaponized the First Amendment – our findings instead suggest individual responsibility outweighs even warped notions of collectivism.

Of particular concern is our finding that high anti-establishment beliefs, coupled with conservative political ideology, lead to support for individual responsibility for social media content. Asking individuals to be responsible for their own online safety is not only the least effective model of platform governance, but it is also the one most likely to exacerbate existing inequalities. The scholarly and regulatory discussion around platform governance is rapidly moving towards a co-governance model with increased government regulation and less self-regulation of the industry. Increased government regulation of online content is seen as a way to enhance transparency, accountability, and human-rights compliance of social media companies (Kaye, Citation2018).

Putting responsibility on individual users is also based on the assumption that all users have the capacity and ability to be ‘responsible’, which simply lacks face validity. On top of that, the individual responsibility model puts a particular burden on those most affected by harmful content online – women, people of color, and other historically marginalized groups (Knight Foundation, Citation2022). Furthermore, users’ activities on platforms are limited to what the organizational design of the product can offer. In other words, if the product makes taking individual responsibility difficult, there is only so much that an individual user can do. Thompson (Citation2014) suggested a concept called ‘prospective design responsibility’ to refer to ‘putting means and measures in place so public values are incorporated in institutional design and so that various stakeholders are (more) likely to take up responsibilities’ (Helberger et al., Citation2018, p. 3).

This study is not without limitations. First, our sample only included people in the US, making the generalizability of the results limited to one country. Although our study offers a clear landscape of Americans’ opinion on social media policy and online content governance, future studies should investigate platform governance opinions – as well as what shapes them – in other contexts, especially outside of the West. This study is based on secondary data. Because our variables were derived and recoded from a panel survey conducted by the Knight Foundation and Gallup, we had less control over how all the questions were initially designed and measured. For instance, this led to the decision of recoding some dependent variables into binary variables to test our hypotheses.

Despite these limitations, this study offers novel insight into public opinion on the problem of online content governance – as well as what shapes such opinions. By doing so, we offer both theoretical and practical contributions. Theoretically, our study contributes to the ongoing discussion in political science and sociology that partisanship alone is not sufficient for explaining American public opinion. By incorporating both anti-establishment beliefs and political ideology in our models, we show that these two variables meaningfully interact to explain people’s attitudes towards different actors’ responsibility regarding online content. This further confirms the work of Uscinski and colleagues (Citation2021) as to the orthogonal relationship between ideology and anti-establishment beliefs. We also suggest a novel dimension of public opinion – support for various priorities in a democratic government. Both collectivist and individual protectionist ideals are embedded in our Constitution and in the American psyche. Our study shows these ideals shape support for the role of the government in regulating online content. These same ideals likely offer explanatory power to a variety of policy attitudes.

Practically, this study contributes to the ongoing public discussion around content moderation and related policies by showing how Americans’ political attitudes and other normative and societal beliefs shape how people attribute responsibility to different actors on social media platforms. Our study’s unique contribution focuses on the relationship between political beliefs and support for different forms of online content governance.

The public's perspective on platform regulation holds significance, even though current debates often revolve around think tanks, political actors, journalists, and academics. One way the people can have a strong voice in democracies is through public opinion, in its myriad forms. Surveys, like this one, are one such way, but so too are the posts, tweets, comments, likes, and queries at the heart of the very online content we struggle to manage. Any form of platform governance, whomever the responsible actor – whether it be governments, platforms, or individuals themselves – impacts both the formation and content of public opinion.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Andrea Lorenz and Carolyn Schmitt for their feedback. We also thank Gallup and Knight Foundation for providing the data.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Raw data were generated at Gallup. Derived data supporting the findings of this study are available from Gallup ([email protected]) on request.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Heesoo Jang

Heesoo Jang is a Richard Cole Doctoral Fellow and a Royster Fellow at the Hussman School of Journalism and Media at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and a Graduate Research Fellow with the Center for Information, Technology, and Public Life (CITAP). She studies the societal impacts of digital platforms and AI technology. [emails: [email protected], [email protected]].

Bridget Barrett

Bridget Barrett is a Roy H. Park Doctoral Fellow in the Hussman School of Journalism and Media at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and a Graduate Research Fellow at the Center for Information, Technology, and Public Life (CITAP). She is interested in new media, advertising technology, and democracy. [email: [email protected]].

Shannon C. McGregor

Shannon McGregor, Ph.D., is an associate professor at the Hussman School of Journalism and Media, and a principal investigator with the Center for Information, Technology, and Public Life – both at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. Her research addresses the role of social media and their data in political processes, with a focus on political communication, journalism, public opinion, and identity. [email: [email protected]].

Notes

1 Nonetheless the term ‘responsibility’ can refer to more than just ‘individual responsibility’ when used independently. (e.g., social media companies should be ‘responsible’ for the online content posted on their platforms).

2 The dataset includes Facebook, Gab, Instagram, LinkedIn, Pinterest, Reddit, Signal, Telegram, TikTok, Tumblr, Twitter, WhatsApp, and YouTube.

3 Here we mean welfare in the broad sense – of providing aid to those who need it. We are not referring to government welfare as a legislative program as it operates in the U.S.

5 ‘The government should regulate and enforce the way social media companies take down false or harmful content or ban users’ and ‘Social media companies should make their own policies, without government regulation, about what people can post on their websites and apps’ on each side.

6 These items are part of a larger battery in the survey measuring what respondents view as important in a democracy. These items, and others in the battery, were developed from the World Values Survey (Inglehart et al., Citation2014).

7 For a full correlation matrix, please see .

References

- Albert, V. (2020, October 7). Facebook bans QAnon pages, groups and Instagram accounts. CBS News. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/facebook-bans-qanon-platforms-pages-groups-instagram-accounts/

- Auxier, B. (2020, October 27). How Americans see U.S. tech companies as government scrutiny increases. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/10/27/how-americans-see-u-s-tech-companies-as-government-scrutiny-increases/

- Barr, R. (2009). Populists, outsiders and anti-establishment politics. Party Politics, 15(1), 29–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068808097890

- Barrett, B., & Kreiss, D. (2019). Platform transience: Changes in Facebook’s policies, procedures, and affordances in global electoral politics. Internet Policy Review, 8(4), 22. https://doi.org/10.14763/2019.4.1446

- Bateman, J., Thompson, N., & Smith, V. (2021, April 1). How social media platforms’ community standards address influence operations. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. https://carnegieendowment.org/2021/04/01/how-social-media-platforms-community-standards-address-influence-operations-pub-84201

- Brito, C. (2020, October 16). YouTube cracks down on QAnon conspiracy theory videos, citing real-world violence. CBS News. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/youtube-qanon-conspiracy-videos-crack-down/

- Cohen, L. (2020, July 22). Twitter unveils plan to limit QAnon activity in new crackdown. CBS News. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/qanon-conspiracy-twitter-bans-accounts-crackdown/

- Douglas, K. M., Uscinski, J. E., Sutton, R. M., Cichocka, A., Nefes, T., Ang, C. S., & Deravi, F. (2019). Understanding conspiracy theories. Political Psychology, 40(S1), 3–35. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12568

- Ekins, E. (2017, October 31). The state of free speech and tolerance in America. CATO Institute. https://www.cato.org/survey-reports/state-free-speech-tolerance-america

- Erisen, C., Guidi, M., Martini, S., Toprakkiran, S., Isernia, P., & Littvay, L. (2021). Psychological correlates of populist attitudes. Political Psychology, 42(S1), 149–171. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12768

- Frenkel, S. (2020, November 23). How misinformation ‘superspreaders’ seed false election theories. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/11/23/technology/election-misinformation-facebook-twitter.html

- Ganesh, B., & Bright, J. (2020). Countering extremists on social media: Challenges for strategic communication and content moderation. Policy & Internet, 12(1), 6–19. https://doi.org/10.1002/poi3.236

- Gillespie, T., Aufderheide, P., Carmi, E., Gerrard, Y., Gorwa, R., Matamoros-Fernández, A., Roberts, S. T., Sinnreich, A., & Myers West, S. (2020). Expanding the debate about content moderation: Scholarly research agendas for the coming policy debates. Internet Policy Review, 9(4), https://doi.org/10.14763/2020.4.1512

- Gorwa, R. (2019). What is platform governance? Information, Communication & Society, 22(6), 854–871. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2019.1573914

- Helberger, N., Pierson, J., & Poell, T. (2018). Governing online platforms: From contested to cooperative responsibility. The Information Society, 34(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/01972243.2017.1391913

- Herbst, S. (2001). Public opinion infrastructures: Meanings, measures, media. Political Communication, 18(4), 451–464. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584600152647146

- Inglehart, R., Haerpfer, C., Moreno, A., Welzel, C., Kizilova, K., Diez-Medrano, J., ..., & Puranen, B. (2014). World values survey: Round six-country-pooled datafile version. Madrid: JD systems institute, 12.

- Jones, J. M. (2021, October 14). Americans revert to favoring reduced government role. Gallup. https://news.gallup.com/poll/355838/americans-revert-favoring-reduced-government-role.aspx

- Kaye, D. (2018). Report of the special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression. United Nations Digital Library. https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/1631686/usage?ln=en

- Knight Foundation. (2022, March 9). Media and democracy: Unpacking America’s complex views on the digital public square. https://knightfoundation.org/reports/media-and-democracy/

- Knight Foundation, & Gallup. (2020). Techlash? America’s Growing Concern With Major Technology Companies. Knight Foundation. https://knightfoundation.org/reports/techlash-americas-growing-concern-with-major-technology-companies/

- Kosseff, J. (2019). The twenty-six words that created the internet. Cornell University Press.

- Kreiss, D., & Mcgregor, S. C. (2018). Technology firms shape political communication: The work of Microsoft, Facebook, Twitter, and Google with campaigns during the 2016 U.S. presidential cycle. Political Communication, 35(2), 155–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2017.1364814

- Krippendorff, K. (2005). The social construction of public opinion. In Kommunikation über kommunikation. Theorie, Methoden und Praxis. Festschrift für Klaus Merten (pp. 129–149). https://repository.upenn.edu/asc_papers/75

- Krouwel, A., Kutiyski, Y., Van Prooijen, J. W., Martinsson, J., & Markstedt, E. (2017). Does extreme political ideology predict conspiracy beliefs, economic evaluations and political trust? Evidence from Sweden. Journal of Social and Political Psychology, 5(2), 435–462. https://doi.org/10.5964/jspp.v5i2.745

- Lacatus, C. (2019). Populism and the 2016 American election: Evidence from official press releases and Twitter. PS: Political Science & Politics, 52(2), 223–228. https://doi.org/10.1017/S104909651800183X

- Lapowsky, I. (2022, January 6). January 6 launched a wave of anti-content moderation bills in America. Protocol. https://www.protocol.com/bulletins/anti-content-moderation-bills

- Li, D. D., & Maskin, E. S. (2021). Government and economics: An emerging field of study. Journal of Government and Economics, 1, 100005. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jge.2021.100005

- McGregor, S.C. (2019). Social media as public opinion: How journalists use social media to represent public opinion. Journalism, 20(8), 1070–1086.

- McGregor, S. C. (2020). Taking the temperature of the room. Public Opinion Quarterly, 84(S1), 236–256. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfaa012

- Mitchell, A., & Walker, M. (2021, August 18). More Americans now say government should take steps to restrict false information online than in 2018. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/08/18/more-americans-now-say-government-should-take-steps-to-restrict-false-information-online-than-in-2018/

- Morar, D. (2022, August 23). The digital services act’s lesson for U.S. policymakers: Co-regulatory mechanisms. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/techtank/2022/08/23/the-digital-services-acts-lesson-for-u-s-policymakers-co-regulatory-mechanisms/

- Nenadić, I. (2019). Unpacking the “European approach” to tackling challenges of disinformation and political manipulation. Internet Policy Review, 8(4). https://doi.org/10.14763/2019.4.1436

- NPR. (2021, May 14). Just 12 people are behind most vaccine Hoaxes on social media, research shows. https://www.npr.org/2021/05/13/996570855/disinformation-dozen-test-facebooks-twitters-ability-to-curb-vaccine-hoaxes

- Pew Research Center. (2017, October 24). Political typology reveals deep fissures on the right and left. https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2017/10/24/5-views-of-the-economy-and-the-social-safety-net/

- Pew Research Center. (2018, April 26). The public, the political system and American democracy. https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2018/04/26/the-public-the-political-system-and-american-democracy/

- Riedl, M. J., Whipple, K. N., & Wallace, R. (2022). Antecedents of support for social media content moderation and platform regulation: The role of presumed effects on self and others. Information, Communication & Society, 1632–1649. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2021.1874040

- Roberts, S. T. (2019). Behind the screen. Yale University Press.

- Selçuk, O. (2016). Strong presidents and weak institutions: Populism in Turkey, Venezuela and Ecuador. Southeast European and Black Sea Studies, 16(4), 571–589. https://doi.org/10.1080/14683857.2016.1242893

- Shearer, E. (2021, January 12). More than eight-in-ten Americans get news from digital devices. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/01/12/more-than-eight-in-ten-americans-get-news-from-digital-devices/

- Smith, M. A. (2000). Public opinion, elections, and representation within a market economy: Does the structural power of business undermine popular sovereignty? American Journal of Political Science, 43(3), 842–863. https://doi.org/10.2307/2991837

- Smith, M. D., & Alstyne, M. V. (2021, August 12). It’s time to update Section 230. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2021/08/its-time-to-update-section-230

- Thompson, D F. (2014). Responsibility for failures of government: The problem of many hands. The American Review of Public Administration, 44(3), 259–273.

- Tworek, H. (2021, October 4). Facebook’s America-centrism is now plain for all to see. Centre for International Governance Innovation. https://www.cigionline.org/articles/facebooks-america-centrism-is-now-plain-for-all-to-see/

- Uscinski, J. E., Enders, A. M., Seelig, M. I., Klofstad, C. A., Funchion, J. R., Everett, C., Wuchty, S., Premaratne, K., & Murthi, M. N. (2021). American politics in two dimensions: Partisan and ideological identities versus anti-establishment orientations. American Journal of Political Science, 65(4), 877–895. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12616

- Vogels, E. A. (2021, January 13). The state of online harassment. Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2021/01/13/the-state-of-online-harassment/