ABSTRACT

The unprecedented power of Big Tech corporations and the complexity of regulating them requires considering the role of news media as a corporate accountability mechanism. The aim of this article is to examine news media’s watchdog role through a performative lens, extending it to the corporate context by looking at three manifestations of performance: media visibility, way of coverage, and sourcing patterns. Based on a longitudinal quantitative content analysis of 920 news stories on Big Tech from four media outlets (2000–2021) in the United States and Germany, we explain variances in the watchdog role taking an over-time, cross-country, and cross-political leaning perspective. Our findings suggest that Big Tech corporations receive little but increasing media attention over the years that is driven by events. Similarly, news coverage contains an increasingly strong presence of a detached watchdog role performance. A more interventionist watchdog role is also on the rise – even though marginally – and political actors are increasingly given a voice in news coverage. From a comparative perspective, our results show that Big Tech corporations are more visible in the US and across right leaning news outlets. US journalists exhibit a more detached approach, while German journalists perform a significantly higher interventionist performance. Corporate sources are overall prominent in the media arena yet dominate more in the US. In conclusion, US and German news media are critical but passive observers over Big Tech corporations and can therefore be labeled a tame yet increasingly growling watchdog when it comes to holding Big Tech accountable.

Introduction

News media’s role as a watchdog is central to democratic governance and describes this monitorial function to hold societal actors accountable (Bovens et al., Citation2014). However, the expanding influence of corporations has revealed cracks in the autonomy of the media (Ferrucci & Eldridge, Citation2022), leaving this watchdog role an increasingly challenged normative position. This especially goes for Big Tech(nology corporations) – i.e., Amazon, Apple, Meta (Facebook), Alphabet (Google), and Microsoft – forming the infrastructural ‘core’ of our digital society that increasingly depends on their services or products. A growing body of research expresses concerns over the quality and independence of journalism (Neilson & Balasingham, Citation2022) and its ability to hold them accountable (Napoli, Citation2021). Considering Big Tech’s unparalleled socio-political influence on society and their own legislative accountability (Popiel, Citation2018), investigating when and how the media critically scrutinize Big Tech becomes imperative for a healthy democracy (Fukuyama et al., Citation2021).

In the context of corporations, extant research finds mixed evidence of whether the notion of the watchdog is as pronounced (Kalogeropoulos et al., Citation2015; Stępińska et al., Citation2016), and at times has even taunted business journalism with a failure of compliance (Carson, Citation2014; Starkman, Citation2014). Concerning Big Tech, academia has primarily approached their corporate accountability from a legal perspective (Helberger, Citation2020), and has attested news media several challenges in effectively covering these corporations (Napoli, Citation2021). While legislative regulation proves to be complex (Helberger, Citation2020), we ask the pivotal question whether and how the media perform a watchdog role towards corporations of this scale and scope (Schultz, Citation1998): To what extent does news media coverage on Big Tech corporations resemble a watchdog function?

To provide a systematic account, a preregistered quantitative content analysis of print news coverage on Big Tech was conducted. As one of the first, our longitudinal design (2000–2021) takes into account rapid societal transformations since the rise of Big Tech and provides indications of how this watchdog function manifested over time. Similar to many other studies, ours focuses on the United States (Esser & Vliegenthart, Citation2017), a country that hosts the headquarters of all corporations in the sample and has been hesitant to regulate their national corporations (Fukuyama et al., Citation2021). We also provide an explicit comparison with Germany, a key member state of the European Union which finds itself among the front runners in ambitiously regulating Big Tech (Helberger, Citation2020). With both media systems approaching Big Tech’s legislative accountability differently, they provide interesting national arenas to comparatively study how the media discuss Big Tech’s assumption of socio-economic responsibilities. Grounded in an expanding politicization of these corporations (Van der Meer & Jonkman, Citation2021), our analysis compares news coverage across different types and political leanings (i.e., center-left versus center-right) of newspapers. This article uniquely contributes to the debate on the performance of news media’s watchdog role on Big Tech in a democratic society, and thus ultimately also ties into debates of the media’s own accountability, independence, and quality (Neilson & Balasingham, Citation2022).

The media’s watchdog function in the age of Big Tech

In times of growing concerns regarding the power of Big Tech (Zuboff, Citation2019), we investigate the media’s role as a ‘mechanism for strengthening accountability in democratic governance’ (Jacobs & Schillemans, Citation2016; Norris, Citation2014, p. 1). To understand corporate accountability in the context of the media’s monitorial function, we look through a performative lens and investigate three manifestations of watchdog journalism. These three manifestations are important as the media’s watchdog function can be performed, and therefore measured, in different ways and each uniquely foster accountability in different ways. First, we argue that media visibility – i.e., the attention media pay to corporations – is a key aspect in journalists’ role in holding Big Tech accountable. Hence, we investigate when and how much (visibility) the media watch and direct society’s attention to these corporations. In line with first-level agenda setting, visibility shows the extent to which their responsibilities are put on the media and public agenda (Carroll & McCombs, Citation2003). Second, how journalists actively or passively unleash different forms of critical scrutiny (detached versus interventionist watchdog role performance) and expose scandals and power transgressions (Jacobs & Schillemans, Citation2016), shows the extent to which journalists perform an active watchdog role. Thirdly, as some actors are by definition more critical than others, it is crucial to determine who is given a voice in the space of mediated visibility and co-engages in the construction of Big Tech’s accountability (sourcing patterns).

Visibility

Media attention is an indication that the media and public are keeping an eye on these corporations, and is a prerequisite for media reputation (Vogler et al., Citation2016). Against the backdrop of an increasing mediatization and politicization of corporations (Van der Meer & Jonkman, Citation2021), corporations have grown more visible and ‘face greater pressures to adapt the framing of their actions to pressures from multiple sources’ (Fiss & Zajac, Citation2006, p. 1177). This inextricable relation to news media leaves their corporate accountability (Jacobs & Schillemans, Citation2016) and renewal of their social license to operate (Van der Meer & Jonkman, Citation2021) dependent on a public discussion of their corporate rights and obligations (Lillà Montagnani & Yordanova Trapova, Citation2018). Corporate accountability is thus constructed by the media’s continuous monitoring (Jacobs & Schillemans, Citation2016). With their accountability being up more publicly for debate, corporations are in need to justify their actions to others (Zyglidopoulos & Fleming, Citation2011) and respond to public pressure.

A detached versus an interventionist watchdog

Since visibility does not state how corporations are covered, we apply a performative lens on news media’s watchdog role as a manifestation in text (Mellado, Citation2015). Concerned with how the media interact with those in power (Hellmueller & Mellado, Citation2016), watchdog role performance is connected to different reporting styles that are traditionally analyzed by content analyses (Mellado, Citation2015). The watchdog role thus emerges in a dynamic set of practices: By questioning, criticizing or denouncing (Mellado, Citation2015) Big Tech, the media can trigger accountability (Jacobs & Schillemans, Citation2016). Additionally, investigations into alleged wrong-doing or informing the public on judicial inquiries (Mellado, Citation2015) inform the reader on the accountability of these actors (Norris, Citation2014), and can amplify their legal accountability (Jacobs & Schillemans, Citation2016).

The concept of media interventionism deals with an active–passive journalistic stance in their reporting. This presence of a journalistic voice forms its own journalistic role (interventionist role; Mellado, Citation2015) but also shapes the extent to which a journalistic voice performs the watchdog role (Mellado et al., Citation2020). Based on the intensity of scrutiny, the voice of scrutiny, and source of the event, a distinction between a detached and an interventionist watchdog role performance (Márquez-Ramírez et al., Citation2020) is made. A detached watchdog role involves passive levels of journalistic scrutiny, in which the journalist criticizes corporations through the words of sources. Remaining a critical yet passive observer, a detached watchdog would resort to covering judicial or external investigations, and citing or paraphrasing criticism by other societal actors.

While this orientation corresponds with a passive pursuit of conduct (Hanitzsch & Vos, Citation2018), the more assertive interventionist watchdog role captures the media’s normative critical-monitorial function of a detective (Hanitzsch & Vos, Citation2018) or critical change agent (Hanitzsch, Citation2011). Performing an interventionist watchdog role, the journalist shows high presence in their coverage, offers their opinion, interpretation, and demands, and makes allegations in first person (Márquez-Ramírez et al., Citation2020). The journalist uses their own voice to actively criticize elites, actively engages in investigative journalism, and acts as participant or advocate, even invoking the corporation as a direct antagonist (Mellado, Citation2015). These two sub-dimensions of the watchdog role become crucial considering widespread concern regarding journalistic independence and agency (Neilson & Balasingham, Citation2022) and a technological complexity that is difficult for the reader to penetrate without active journalistic assistance (Napoli, Citation2021).

Patterns of cited sources

Considering a prevalence of this detached orientation across both countries, we tie watchdog role performance with routine practices of sourcing. Sourcing determines who is co-constructing the coverage about corporations, and thus indirectly how the journalist performs the watchdog role. Voices, i.e., sources that are directly or indirectly quoted in journalistic work, shape the media agenda (Carroll & McCombs, Citation2003) and are ‘structurally privileged and able to define’ (Allen & Savigny, Citation2012, p. 281) accountability. We hence argue that the reliance on certain sources can determine the performed levels of watchdog journalism, and influence which sources are given a voice to perform or contest critical scrutiny.

While journalists’ dependence on information subsidies (Gandy, Citation1982) is nothing new, the practice of sourcing takes on a particular function given Big Tech’s considerable opinion power (Helberger, Citation2020), economic interdependence with platforms, and the technological complexity and opacity of these corporations (Napoli, Citation2021). Journalists draw on corporations as news sources in an increasingly routinized manner (Grünberg & Pallas, Citation2013) and journalism has often been accused of being overly influenced by PR efforts (Doyle, Citation2006). While the watchdog role is inherently tied to political, governmental and corporate sources (Berkowitz, Citation2009), a prominence of cited corporate sources speaks to the journalist as a passive observer (Hanitzsch, Citation2011), and of corporate opinion power that opens the door for Big Tech corporations to shape readers’ understanding on their corporate accountability towards society (Helberger, Citation2020). Given Big Tech’s considerable bargaining power (Neilson & Balasingham, Citation2022), the more diverse stakeholders get to voice their opinions, the more readers are enabled to form an opinion on the role of Big Tech in society.

Sources of variation in news coverage: cross-sectional and temporal comparison

Since the rise of these corporations at the onset of the millennium, several transformations warrant a longitudinal look at developments in news coverage (Esser & Vliegenthart, Citation2017). An increasing commercialization, financial dependence (Wahl-jorgensen et al., Citation2009), mediatization (Van der Meer & Jonkman, Citation2021), and event driven character (Strauß, Citation2021) of corporate news coverage coincide with a decline in corporate investigative journalism (Carson, Citation2014). Simultaneously, the sector has gained public affairs dominance (Popiel, Citation2018) that renders organizations more powerful in regulating their public visibility. Over the years, the relationship between Big Tech and the media has been a dynamic and changing one, exhibiting a shift from a tech-utopian to a tech-dystopian outlook on the role of technology in our society (Weiss-Blatt, Citation2021). Indeed, technology innovations have been repeatedly disrupted by crises regarding, e.g., large-scale personal data collections or misinformation that may lead the media to extend their monitorial function to these corporations over-time.

While some studies indeed have critically discussed temporal developments in corporate news coverage (see e.g., Kalogeropoulos et al., Citation2015; Usher, Citation2013, Citation2017) generally, and technology coverage specifically (Weiss-Blatt, Citation2021), ours is the first to answer calls (Mellado, Citation2020) for a longitudinal examination of media’s watchdog role towards these newly emerged societal actors. We aim to understand whether this accountability has become more mediatized, and whether their growing power (Zuboff, Citation2019) has made these corporations more newsworthy over time. We ask:

Research Question 1 (RQ1): How have the media visibility of Big Tech corporations, watchdog role performance, and patterns of cited sources developed over time?

However, while both countries appear to host stable journalistic cultures (Mellado, Citation2020), the topic might leave journalists’ watchdog role and its performance more ambiguous (Mellado, Citation2020; Napoli, Citation2021). In Germany, the watchdog role has played an important role in political news coverage (Hallin & Mancini, Citation2004). Given Germany’s notable advances in media concentration law (Helberger, Citation2020), the presence of a detached and interventionist watchdog role might differ on this topic (Mellado, Citation2020) in accordance with the national regulatory agenda. Meanwhile, the United States host the headquarters of the largest Big Tech corporations, allowing for greater access to corporate sources (Napoli, Citation2021). Studies uncovered a structural bias given to corporate voices (Allen & Savigny, Citation2012), often remaining unchallenged by journalists (Usher, Citation2017). The distinct relevance of both national media arenas in (de)constructing the accountability of Big Tech corporations asks for a cross-country comparison:

Research Question 2 (RQ2): How do media visibility of Big Tech, watchdog role performance, and patterns of cited sources in news coverage differ between the United States and Germany?

Research Question 3 (RQ3): How do the media visibility of Big Tech, watchdog role performance, and patterns of cited sources in news coverage differ between outlets with a center-left versus center-right political leaning?

Method

This study’s research design, objective and analysis elements were preregistered and are located on the Open Science Framework. To dissect the monitorial role of news media, we systematically analyzed print news coverage on Big Tech over the past twenty years (2000–2021). Due to the availability of print news coverage, we can draw conclusions longitudinally, while honoring print journalism’s role to set the agenda for the public (Djerf-Pierre & Shehata, Citation2017) and other, newer media.

Sampling strategy

We compare news coverage on Big Tech across two relevant national media arenas. Due to the large time frame of this study, we limited the number of chosen media outlets to two newspapers per country that would cover the audience’s political spectrum. Our approach resembles a most-different-design approach (Anckar, Citation2008). All four outlets show similarity in the sense that they are situated in a Western context, can be related to some political ideology, and show high levels of professionalism (Hallin & Mancini, Citation2004). However, within this context of advanced, post-industrial democracies, the two countries differ substantially in their political (dual versus multi-system), media (Liberal versus Democratic Corporatist) system features, and regulatory approaches, making it possible to compare relationships in highly different settings. We lean on four outlets that have frequently been chosen for academic investigations (Hellmueller et al., Citation2016) and do not distinguish between a popular versus elite orientation, as this distinction has shown negligible influence on watchdog role performance (Mellado & Lagos, Citation2014). The selection of newspapers was constrained by the electronic availability of sources in the database NexisUni, but the chosen news outlets are among the respective country’s most important newspapers ().

Table 1. Overview of news outlets. Newspapers sampled for comparison, n = 920.

The seminal label of ‘Big Tech’ describes the most influential companies within their area in the technology sector: Meta (Facebook), Microsoft, Amazon, Apple, and Alphabet (Google). We chose to include these five corporations due to their comparable scope and financial investments to control the narrative around digital regulation (Corporate Europe Observatory, Citation2021). The codebook allowed to control for potential cross-corporate differences. Relevant news articles were selected by searching for articles in which the corporation’s name appeared at least twice in the headline and first paragraph. An iterative process to improve recall and precision showed that loosening the lead section and proximity connector criteria resulted in a population of less relevant and in-depth news coverage. For each news outlet, a list of news articles published in all sections of the outlet between January 1, 2000, and November 3, 2021, was downloaded. We then manually reviewed the list and excluded articles according to strict exclusion criteria.Footnote1 This resulted in a dataset of n = 20, 123 articles that allowed to inspect the media visibility of Big Tech corporations over these two decades. From this body of news articles, we used a stratified random sampling strategy to randomly select 23 articles per outlet and year for the period of 2002–2020. To account for the longitudinal design, we opted to sample in two-year intervals (2002, 2004, 2006, etc.). For each even year, we randomly assigned each article a number ranging between 0 –1 and randomly included twenty-three articles in our sample. A total of n = 920 articles were coded for news media’s watchdog function. While the visibility analysis accounts for big business events that have a larger chance to be included in the random sample, sampled articles were rather evenly distributed within each sampled year (see Appendix 1 for sampling distribution).

News features of the watchdog function: the dependent variables

A codebook guided a systematic coding of news coverage and familiarized coders with the case of Big Tech (see Appendix 2). Four student coders were trained in eight hours of training on English language material until intercoder-reliability reached satisfactory levels. Including the first author, three coders were native German speakers; all five coders were fluent English speakers. In an additional hour of training, German-speaking coders were also trained on the application of the codebook on German language articles to ensure comparability. The final codebook contained both English and German examples and context-specific application instructions that allowed a valid application to German news articles. To overcome traditional issues for datasets with skewed variables and a larger number of coders (Matthes et al., Citation2015), we relied on a more chance-corrected reliability, i.e., Fretwurst’s (Citation2015) Standardized Lotus of .67 and higher, (n = 30). This coefficient has been routinely employed (see e.g., Araujo & van der Meer, Citation2020).

Media visibility

Before drawing a random sample for manual analysis, we used the recorded number of news articles (n = 20, 123) as a measure to determine Big Tech’s relative media visibility. To calculate the relative visibility against the total volume of news coverage by the respective outlet, we chose a random period of one week mid-time frame (2010) to arrive at an average weekly news coverage volume.Footnote2

Watchdog role performance: a detached versus interventionist watchdog

Based on Mellado (Citation2015), ten indicators were used to measure the emergence of the watchdog role in-text (see ). These reflect different reporting styles that may include questioning, criticizing or denouncing by the journalist (interventionist watchdog role) or by a source (detached watchdog role). We inferred this distinction from Márquez-Ramírez et al. (Citation2020), with four (five respectively) indicators measuring the detached (interventionist) watchdog role, leaving out the indicator External Investigation. These items were coded for their presence (1) or absence (0) and summarized in a final score for each news item, for which we divided the sum of points by the total items for each index (range = 0–1). Hence a higher score indicated a higher performative degree of the watchdog role, and vice versa.

Table 2. Watchdog role indicators.

Patterns of cited sources

Following Allen and Savigny (Citation2012), we coded whether a corporate, political, or regulatory source was cited and present (1) or absent (0) in the news article. Citing a corporate source (agreement = .87, s-lotus = .93), the journalist quotes or paraphrases corporate representatives, PR texts, announcements or signals the intent to do so. A political source (agreement = .80, s-lotus = .89) labels quotes or paraphrases of politicians, ministers or governmental representatives. Lastly, a regulatory source (agreement = .73, s-lotus = .85) emerges through quotes or paraphrases of regulatory commissions or judicial employees.

Yearly trend variables

We computed a yearly trend variable by assigning a consecutive number to each year present in the data. In the first dataset (n = 20,213), the values range from 1 (year: 2000) to 22 (year: 2021). The manual dataset contains articles sampled in even years, so values range from 1 (year: 2002) to 10 (year: 2020) and reflect a bi-annual increase.

Analysis plan

Analyses were conducted in several consecutive steps, while primarily relying on mean or count variance and regression analyses. For each individual watchdog role indicator, as well as the presence of cited sources, chi-square tests of independence were calculated to test how they differ across outlets and time. For the indexed watchdog role indicators, univariate linear models and ordinary least square regression models were conducted to test the influence of the linear yearly trend variables, country and political leaning.

Findings

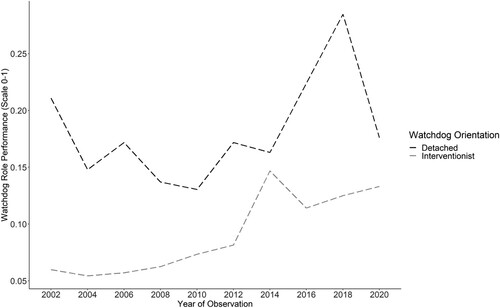

The watchdog role manifests across all four outlets (see ), yet the detached and interventionist orientation show unequal presence. The presence of a detached watchdog (MDetached = .18, SD = .22) is twice as high as the interventionist watchdog (MInterventionist = .09, SD = .16). These findings show significant, t(1465.6) = 13.081, p = .000, but moderate, (Cohen’s d = .61), differences and indicate a dominating passive scrutiny. Simultaneously, corporate sources are prominently cited in over 70% of the whole sample. Political and regulatory sources are only cited in 10–15% of news articles, giving these minimal space in the media arena.

Table 3. Watchdog role performance and cited sources in news coverage. The index was created by dividing the number of present indicators by the total number of indicators and ranges from 0 to 1.

The individual indicators in provide a clearer picture through which routines journalists perform the role of a watchdog. In terms of the intensity of scrutiny, lukewarm forms of scrutiny prevail. The watchdog role is performed through its lesser intense forms of questioning (in 20.11% of the articles) and criticizing (26.63%). Similarly, the presence of interventionist indicators decreases with rising level of intensity: while in 16.64% of articles journalists themselves question Big Tech, only 8.15% of articles contain a denouncement of Big Tech by journalists.

Table 4. The presence of individual indicators across outlets, in percentage (n = 920).

RQ 1: the watchdog role over time

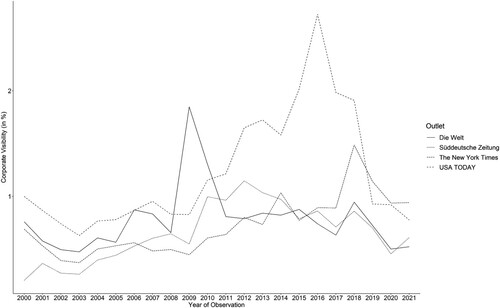

Relative visibility of Big Tech corporations in news coverage is minimal overall yet slightly increasing over the years (b = .03, p < .001). Media attention, however, fluctuates and at no moment in time exceeds 2.5%, increasing with bigger events (). Across all outlets, media attention increases in 2014, a year that marks, e.g., the acquisitions of WhatsApp and Oculus by Facebook, Beats by Apple, and Deepmind and Nest by Google. We see media visibility peak around 2018–2019, a time period that witnessed, among others, the release of the iPhone X by Apple, Facebook’s Cambridge Analytica scandal, and Google’s sexual misconduct investigations. From around 2019 onwards, relative attention decreases, falling to a level of under 1% of total the outlets’ coverage volume again.

Longitudinally, also watchdog role performance increases significantly over the years, showing a stronger increase for the interventionist orientation (b = .01, p < .001) compared to the detached orientation (b = .006, p = .01). shows how a detached watchdog performance stagnates around .15 to .20 but suddenly rises up to .30 in 2018, coinciding with a series of scandals rocking the tech industry. Also the interventionist watchdog role performance increases progressively from around .05 in 2002 to just below .15 in 2020, with the exception of an upward trend in 2014 () that falls together with, e.g., major acquisitions of WhatsApp and Oculus.

Figure 2. Over-time development of the interventionist and detached watchdog role orientation, indexed on a scale of 0–1.

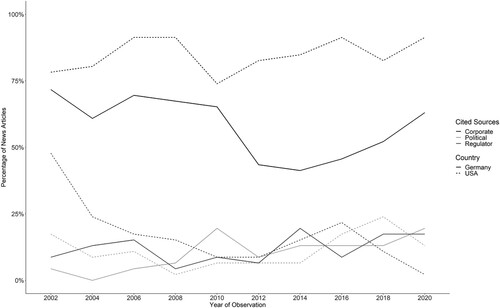

In comparison to media attention and watchdog role performance, we do not find much fluctuation among cited sources (see ). While corporate sources are continuously cited in large quantity (b = −.007, p = .33) and the presence of regulatory sources remains marginal (b = −.01, p = .08), we see a significant yet substantially small increase in annual citations of political sources (b = .01, p = .005).

RQ 2: the watchdog role in the United States and Germany

Comparing the two national media arenas reveals that Big Tech corporations receive more relative media attention in the US compared to Germany, b = .27, p < .001. In contrast, the overall watchdog role performance does not significantly differ across countries, t(917.29) = −1.275, p = .202. However, in both countries, the detached watchdog is significantly more present, with moderate differences in the United States (t(741.77) = −10.276, p < .001, Cohen’s d = 0.68), and small differences in Germany (t(900.09) = −4.15, p < .001, Cohen’s d = 0.27). Despite indicating rather small effects, significantly more indicators of the interventionist orientation emerge in German news outlets, t(874.54) = 3.16, p = .002 (Cohen’s d = 0.21), while significantly more detached indicators manifest in US outlets, t(894.38) = −3.26, p < .001 (Cohen’s d = 0.22). Also at indicator level, associations remain weak: News coverage in the US involves significantly more questioning (χ2 (1) = 17.59, p < .001, Cramer’s V = .14) and denouncing (χ2 (1) = 6.4, p = .01, Cramer’s V = .1) by a source, while German outlets perform significantly more criticism (χ2 (1) = 7.2, p = .007, Cramer’s V = .09) and denouncing (χ2 (1) = 8.92, p = .003, Cramer’s V = .08) by journalists.

Inspecting the presence of sources across countries reveals significant differences. Corporate sources are cited in less than 60% of the sample in Germany, while corporate sources appear in around 85% of articles published in the United States, χ2 (1) = 80.55, p < .001, Cramer’s V = .3. While political sources are equally cited in both countries, χ2 (1) = .28, p = .595, regulatory sources are cited more in the United States, χ2 (1) = 5.03 p = .025. However, this association is small (Cramer’s V = .07) on country level and can be better explained at the outlet level, as the New York Times gives cites regulator sources in over 20% of its articles (see ).

RQ 3: the watchdog role across political leaning

In relative terms, Big Tech corporations are significantly more visible in center-right leaning news outlets, F(1, 412) = 255.2, p < .001 (see ). Linear regression analysis confirms this positive effect (b = .31, p = .000). The detached watchdog dominates across the political spectrum and the interventionist watchdog is moderately significantly less represented in both center-left, t(824.78) = −8.31, p < .001, Cohen’s d = 0.55, and center-right oriented newspapers, t(843.73) = −6.14, p < .001, Cohen’s d = 0.4. Meanwhile, regression analyses show that the detached orientation (b = −.04, p = .001) is significantly negatively affected by center-right leaning. This effect of political leaning is not present for the interventionist orientation (b = −.007, p = .45). At indicator level, differences are minimal and only present for two indicators: Left-leaning outlets report significantly more on judgements (χ2 (1) = 10.21, p = .001) and involve more denouncing by journalists (χ2 (1) = 6.4, p = .011). Political leaning has no significant effect on the annual presence of corporate (b = −.02, p = .668), nor political (b = −.03, p = .231) nor regulator (b = −. 05, p = .124) sources.

Exploratory analyses

In the addition of pre-registered analysis plan, we also tested if sourcing patterns significantly predicted watchdog role performance. The overall regression model was statistically significant, R2 = .15, F(3, 916) = 56.12, p < .001. It was found that the presence of corporate sources (b = .02, p = .02), political sources (b = .04, p = .001), and regulator sources (b = .13, p < .001) significantly predicted watchdog role performance.

Discussion

A comparative analysis of news media coverage on Big Tech showed that this watchdog role is performed through a set of dynamic practices that are shaped by their context. Our study revealed the media’s role as a tame yet increasingly growling watchdog. On the road of setting the agenda on their accountability, the media predominantly perform a detached watchdog role, leaving a critical scrutiny of Big Tech to quoted sources. This detachment goes hand in hand with an increasing incorporation of political and regulatory sources in news coverage. This bears several implications for the media’s multi-fold ways in holding corporations accountable. First, the discussion of Big Tech corporations’ accountability is only slowly entering the media debate. In times in which the legal system is struggling to keep up to speed with fast changing technology corporations, the media increasingly trigger the debate of corporate accountability through critical news coverage or amplify accountability discourses by reporting on legal regulatory attempts (Jacobs & Schillemans, Citation2016). This leaves the media the role of a mediator to provide critical information to others to assess Big Tech’s accountability. Zooming in on Big Tech, the detached watchdog seems equally (Hellmueller & Mellado, Citation2016) or more often (Márquez-Ramírez et al., Citation2020; Mellado et al., Citation2017) present than in previous studies on watchdog journalism in both countries.

However, temporal patterns indicate that media visibility remains driven by isolated events and news values rather than a continuously monitoring watchdog role (Strauß, Citation2021). Second, an increase in political sources can be indicative of an increasingly performed watchdog function (Hellmueller & Mellado, Citation2016), as well as a growing politicization and mediatization (Van der Meer & Jonkman, Citation2021) of Big Tech corporations. Concomitant with the growing power of Big Tech in society, the media seem to contextualize these corporations increasingly as political powers in society that fall under the jurisdiction of the ‘fourth estate’ (Schultz, Citation1998). Lastly, this watchdog role is increasingly performed through a more interventionist orientation (see ), in which journalists themselves raise their voices and critically monitor Big Tech. However, considering dominant patterns of detached watchdog reporting and of corporate sourcing, Western ideals of balance and objectivity seem to infringe a more active watchdog role manifestation. While these ideals speak of the quality of journalism (Neilson & Balasingham, Citation2022), especially in times of an alleged techlash (Weiss-Blatt, Citation2021) and regulatory complexity (Helberger, Citation2020), it leaves the reader with a greater responsibility to navigate technological and regulatory complexities themselves (Napoli, Citation2021) and to hold Big Tech accountable.

While a detached watchdog prevails in a cross-country comparison, especially German news outlets perform also a more interventionist watchdog role. Indicative of higher adversarial watchdog journalism (Hanitzsch & Vos, Citation2018; Mellado et al., Citation2020), German journalists seem to increasingly demand accountability in an active manner. As Germany is one of the forerunners of tech regulation in Europe, the media seem to act in accordance with the regulatory agenda on Big Tech (Helberger, Citation2020). In the meantime, a greater visibility of these corporations in the United States speaks to their importance to the national economy, and perhaps to a greater access to corporate sources, again suggesting that media coverage is not actively driven by the watchdog role but news factors.

Lastly, despite a growing politicization of Big Tech, their accountability seems to be a concern expressed across the political spectrum. News coverage by the New York Times is exemplary of reinforcing legal accountability (Jacobs & Schillemans, Citation2016; Norris, Citation2014), a demand in light of the scale and scope of these organizations that seems to be shared irrespective of political orientation. To conclude, this study is the first to show how the media’s watchdog role manifests in different, dynamic sets of practices. In times in which Big Tech’s accountability is innately connected to a healthy democracy (Fukuyama et al., Citation2021) and media autonomy itself (Ferrucci & Eldridge, Citation2022), the media remain critical yet passive observers.

Limitations and future research

Research on the media’s watchdog role towards corporations is far from being empirically saturated. Detected temporal patterns highlight the importance of longitudinal research. In addition, some indicators suffered from lower agreement, reflecting the difficulty to distinguish the intensity of scrutiny (i.e., questioning versus criticizing) and the intensity of their individual presence. Considering a strong interdependence of corporations with the production and dissemination of news (Neilson & Balasingham, Citation2022), future research could compare our results for print news to news from other types of (social) media. Similarly, we only measured the presence of corporate, political, and regulator sources. Measuring the inclusion of other non-elite sources would help us understand whether journalists also draw on the general public or interest groups to disperse opinion power (Helberger, Citation2020).

To conclude, the rise of large technology corporations presents a multi-faceted phenomenon and might leave the media’s role dynamic and ambiguous, highlighting the need to disentangle the media’s performative and normative roles and their relation. Considering the unprecedented media elite power of Big Tech (Popiel, Citation2018) that leaves these corporations unparalleled influence on their own regulatory accountability, it is pivotal to further map factors that influence the media’s potential as an alternative corporate accountability mechanism. While we cannot reiterate previous claims on a failure of the watchdog (Starkman, Citation2014) towards Big Tech, this watchdog seems to be menacingly growling and it is to be seen what scandal will trigger a bark.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available at Open Science Framework: https://osf.io/ge64b/?view_only=02837cd9092147ef8f55a608a95607ea.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Alexandra Schwinges

Alexandra Schwinges ([email protected]) is a PhD candidate at the Amsterdam School of Communication Research (ASCoR), University of Amsterdam. Her research interests lie in the intersection of journalism and Big Technology corporations. In particular, she is interested in how news media cover and interact with corporations, and how both influence policy formation.

Toni G. L. A. van der Meer

Toni G. L. A. van der Meer ([email protected]) is an Associate Professor in Communication Science at the Amsterdam School of Communication Research (ASCoR), University of Amsterdam. His research focuses on crisis communication, (negativity) bias in the news, processes of mediatization, and misinformation.

Irina Lock

Irina Lock ([email protected]) is professor of strategic communication at the Friedrich Schiller University Jena, Germany. She studies how organizations communicate about their societal responsibilities, how they influence public policy and debate, and how they respond to grand challenges.

Rens Vliegenthart

Rens Vliegenthart ([email protected]) is a full professor in Strategic Communication at Wageningen University and Research (WUR). His research focuses on media–politics relations, media coverage of social movements, election campaigns, and economic news coverage.

Notes

1 An article was excluded if (1) it did not discuss selected Big Tech corporations, (2) if it was published as a short digest or briefing, and (3) if it concerned tips on gadgets, (4) if the same article was published in several regional editions, keeping one.

2 Due to the number of regional editions of Süddeutsche Zeitung, we limited the total number to the Bavarian edition.

References

- Allen, H., & Savigny, H. (2012). Selling scandal or ideology? The politics of business crime coverage. European Journal of Communication, 27(3), 278–290. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323112455907

- Anckar, C. (2008). On the applicability of the most similar systems design and the most different systems design in comparative research. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 11(5), 389–401. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645570701401552

- Araujo, T., & van der Meer, T. G. (2020). News values on social media: Exploring what drives peaks in user activity about organizations on Twitter. Journalism, 21(5), 633–651. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884918809299

- Berkowitz, D. A. (2009). Reporters and their sources. In K. Wahl-Jorgensen & T. Hanitzsch (Eds.), The handbook of journalism studies (pp. 102–115). Routledge.

- Blank, M., Duffy, F., Leyendecker, V., & Silva, M. (2021). The lobby network: Big tech’s Web of influence in the EU. Corporate Europe Observatory. The Lobby Network: Big Tech’s web of Influence in the EU | Corporate Europe Observatory.

- Bovens, M., Goodin, R. E., Schillemans, T., & Norris, P. (2014). Watchdog journalism. In M. Bovens, R. E. Goodin, & T. Schillemans (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of public accountability. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199641253.013.0015

- Carroll, C. E., & McCombs, M. (2003). Agenda-setting effects of business news on the public's images and opinions about major corporations. Corporate Reputation Review, 6(1), 36–46. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.crr.1540188

- Carson, A. (2014). The political economy of the print media and the decline of corporate investigative journalism in Australia. Australian Journal of Political Science, 49(4), 726–742. https://doi.org/10.1080/10361146.2014.963025

- Cioffi, J. W., & Höpner, M. (2006). The political paradox of finance capitalism: Interests, preferences, and center-left party politics in corporate governance reform. Politics & Society, 34(4), 463–502. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032329206293642

- Djerf-Pierre, M., & Shehata, A. (2017). Still an agenda setter: Traditional news media and public opinion during the transition from low to high choice media environments. Journal of Communication, 67(5), 733–757. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12327

- Donsbach, W. (2012). Journalists’ role perception. In The international encyclopedia of communication. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781405186407.wbiecj010.pub2

- Doyle, G. (2006). Financial news journalism: A post-Enron analysis of approaches towards economic and financial news production in the UK. Journalism, 7(4), 433–452. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884906068361

- Esser, F., & Vliegenthart, R. (2017). Comparative research methods. In The international encyclopedia of communication research methods (pp. 1–22). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118901731.iecrm0035

- Ferrucci, P., & Eldridge, S. A., II (2022). The institutions changing journalism: Barbarians inside the gate. Taylor & Francis.

- Fiss, P. C., & Zajac, E. J. (2006). The symbolic management of strategic change: Sensegiving via framing and decoupling. The Academy of Management Journal, 49(6), 1173–1193. https://doi.org/10.2307/20159826

- Fretwurst, Benjamin. (2015). Reliabilität und Validität von Inhaltsanalysen. Mit Erläuterungen zur Berechnung desReliabilitätskoeffizienten ‘Lotus’ mit SPSS. In Werner Wirth, Katharina Sommer, Martin Wettstein, & Jörg Matthes (Eds.), Qualitätskriterien in der Inhaltsanalyse. Cologne, Germany: Halem.

- Fukuyama, F., Richman, B., & Goel, A. (2021). How to save democracy from technology: Ending Big Tech’s information monopoly. 100, 98.

- Gandy, O. H. (1982). Beyond agenda setting: Information subsidies and public policy. Praeger.

- Grünberg, J., & Pallas, J. (2013). Beyond the news desk – the embeddedness of business news. Media, Culture & Society, 35(2), 216–233. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443712469138

- Hallin, D. C., & Mancini, P. (2004). Comparing media systems: Three models of media and politics. Cambridge University Press.

- Hanitzsch, T. (2011). Populist disseminators, detached watchdogs, critical change agents and opportunist facilitators: Professional milieus, the journalistic field and autonomy in 18 countries. International Communication Gazette, 73(6), 477–494. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748048511412279

- Hanitzsch, T., & Vos, T. P. (2017). Journalistic roles and the struggle over institutional identity: The discursive constitution of journalism. Communication Theory, 27(2), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1111/comt.12112

- Hanitzsch, T., & Vos, T. P. (2018). Journalism beyond democracy: A new look into journalistic roles in political and everyday life. Journalism, 19(2), 146–164. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884916673386

- Helberger, N. (2020). The political power of platforms: How current attempts to regulate misinformation amplify opinion power. Digital Journalism, 8(6), 842–854. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2020.1773888

- Hellmueller, L., & Mellado, C. (2016). Watchdogs in Chile and the United States: Comparing the networks of sources and journalistic role performances. International Journal of Communication, 10(16), 3261–3280. 1932–8036/20160005

- Hellmueller, L., Mellado, C., Blumell, L., & Huemmer, J. (2016). The contextualization of the watchdog and civic journalistic roles: Reevaluating journalistic role performance in U.S. Newspapers. Palabra Clave - Revista de Comunicación, 19(4), 1072–1100. 10.5294/pacla.2016.19.4.6

- Jacobs, S., & Schillemans, T. (2016). Media and public accountability: Typology and exploration. Policy & Politics, 44(1), 23–40. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557315X14431855320366

- Kalogeropoulos, A., Svensson, H. M., van Dalen, A., de Vreese, C., & Albæk, E. (2015). Are watchdogs doing their business? Media coverage of economic news. Journalism, 16(8), 993–1009. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884914554167

- Lillà Montagnani, M., & Yordanova Trapova, A. (2018). Safe harbours in deep waters: A new emerging liability regime for Internet intermediaries in the Digital Single Market. International Journal of Law and Information Technology, 26(4), 294–310. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijlit/eay013

- Márquez-Ramírez, M., Mellado, C., Humanes, M. L., Amado, A., Beck, D., Davydov, S., Mick, J., Mothes, C., Olivera, D., Panagiotu, N., Roses, S., Silke, H., Sparks, C., Stępińska, A., Szabó, G., Tandoc, E., & Wang, H. (2020). Detached or interventionist? Comparing the performance of watchdog journalism in transitional, advanced and non-democratic countries. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 25(1), 53–75. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161219872155

- Matthes, J., Marquart, F., Naderer, B., Arendt, F., Schmuck, D., & Adam, K. (2015). Questionable research practices in experimental communication research: A systematic analysis from 1980 to 2013. Communication Methods and Measures, 9(4), 193–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/19312458.2015.1096334

- Mellado, C. (2015). Professional roles in news content: Six dimensions of journalistic role performance. Journalism Studies, 16(4), 596–614. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2014.922276

- Mellado, C. (Ed.). (2020). Beyond journalistic norms: Role performance and news in comparative perspective. Routledge.

- Mellado, C., Hellmueller, L., Márquez-Ramírez, M., Humanes, M. L., Sparks, C., Stepinska, A., Pasti, S., Schielicke, A.-M., Tandoc, E., & Wang, H. (2017). The hybridization of journalistic cultures: A comparative study of journalistic role performance. Journal of Communication, 67(6), 944–967. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12339

- Mellado, C., & Lagos, C. (2014). Professional roles in news content: Analyzing journalistic performance in the Chilean national press. International Journal of Communication, 8(0), 2090–2112. 1932–8036/20140005

- Mellado, C., Mothes, C., Hallin, D. C., Humanes, M. L., Lauber, M., Mick, J., Silke, H., Sparks, C., Amado, A., Davydov, S., & Olivera, D. (2020). Investigating the gap between newspaper journalists’ role conceptions and role performance in nine European, Asian, and Latin American countries. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 25(4), 552–575. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161220910106

- Napoli, P. M. (2021). The platform beat: Algorithmic watchdogs in the disinformation age. European Journal of Communication, 36(4), 376–390. https://doi.org/10.1177/02673231211028359

- Neilson, T., & Balasingham, B. (2022). Big Tech and news: A critical approach to digital platforms, journalism, and competition law. In James Meese & Sara Bannerman (Eds.), The algorithmic distribution of news: Policy responses (pp. 171–189). Springer International Publishing.

- Norris, P. (2014, May 1). Watchdog journalism. In The Oxford handbook of public accountability. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199641253.013.0015

- Popiel, P. (2018). The tech lobby: Tracing the contours of new media elite lobbying power. Communication, Culture and Critique, 11(4), 566–585. https://doi.org/10.1093/ccc/tcy027

- Schultz, J. (1998). Reviving the fourth estate: Democracy, accountability and the media. Cambridge University Press.

- Starkman, D. (2014). The watchdog that didn’t bark. Columbia University Press. https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.7312star15818/html

- Stępińska, A., Jurga- Wosik, E., Adamczewska, K., Secler, B., & Narożna, D. (2016). Journalistic role performance in Poland. Środkowoeuropejskie Studia Polityczne, 2, 37–51. https://doi.org/10.14746/ssp.2016.2.3

- Strauß, N. (2021). Covering sustainable finance: Role perceptions, journalistic practices and moral dilemmas. Journalism, 23(6), 1194–1212. https://doi.org/10.1177/14648849211001784

- Usher, N. (2013). Ignored, uninterested, and the blame game: How The New York Times, marketplace, and TheStreet distanced themselves from preventing the 2007–2009 financial crisis. Journalism, 14(2), 190–207. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884912455904

- Usher, N. (2017). Making business news: A production analysis of The New York Times. International Journal of Communication, 11, 363–382. 1932–8036/20170005.

- Van der Meer, T. G. L. A., & Jonkman, J. G. F. (2021). Politicization of corporations and their environment: Corporations’ social license to operate in a polarized and mediatized society. Public Relations Review, 47(1), 101988–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2020.101988

- Vogler, D., Schranz, M., & Eisenegger, M. (2016). Stakeholder group influence on media reputation in crisis periods. Corporate Communications: An International Journal, 21(3), 322–332. https://doi.org/10.1108/CCIJ-01-2016-0003

- Wahl-jorgensen, K., Hanitzsch, T., Eb, I., & Dijk, T. A. V. (2009). The handbook of journalism studies. Routledge.

- Weiss-Blatt, Nirit. (2021). The Techlash and Tech Crisis Communication. Bingley, UK: Emerald Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/9781800430853.

- Zuboff, S. (2019). The age of surveillance capitalism: The fight for a human future at the new frontier of power: Barack Obama’s books of 2019. Profile Books.

- Zyglidopoulos, S., & Fleming, P. (2011). Corporate accountability and the politics of visibility in ‘late modernity’. Organization, 18(5), 691–706. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508410397222