ABSTRACT

This article investigates what is at stake in decolonising the study of conspiracy theories online. It challenges the confidence with which conspiracy theories are often dismissed as aberrations and negative externalities of digital ecosystems. Without reifying conspiracy theories, we identify as problematic how alternative forms of knowledge production are dismissed and colonial tropes reproduced. Contributing to conversations around ‘decolonising the internet’, we offer additional and sharper tools to understand the role and implications of conspiracy theorising for communicative and political practices in different societies globally. Empirically, we analyse a conspiracy theory circulating in Nigeria between 2018 and 2019 purporting that Nigerian President Buhari had died and the man in office was his ‘clone’. Conceptually, our analysis intersects with Achille Mbembe’s work on power in the postcolony, to illustrate how it is possible to adopt alternative forms of normativity that eschew the stigmatisation and exclusion that has prevailed, but still offer evaluative frameworks to locate conspiracy theories in contemporary digital environments. We engage with Mbembe’s ideas about how humorous and grotesque forms of communication can result in the zombification of both the ‘dominant’ and those ‘apparently dominated’. We argue that zombification as a theoretical intervention provides a useful addition to the conceptual and normative repertoire of those studying conspiracy theories, between the poles of dismissal/condemnation and pure curiosity/acceptance of what is said.

1. Introduction

In 2017, a conspiracy theory that Nigerian President Muhammadu Buhari had died in a London hospital and was replaced with a body double called ‘Jubril’ from Sudan surfaced in popular discourse. This occurred after Buhari had spent three months undergoing medical treatment in London for an undisclosed illness. The President’s location outside of Nigeria, in the country that was its former coloniser, gave shape to different versions of the conspiracy theory, with suggestions that British and/or Nigerian political elites were behind the replacement of the President and were hiding his alleged death.

Anxieties around the President were initially provoked by a tweet on 19 May 2017, in which Eric Joyce, a British politician, tweeted that the President was dead. President Buhari had last been seen in public two weeks earlier. Eric Joyce’s tweet triggered Nigerians who were looking to escape a repeat of the power vacuum that had been experienced in the country after the death of a previous sitting president, Umaru Yar’Adua, who died in similar and somewhat mysterious circumstances in 2010.

Narratives that the President was a clone emerged in public discourse following President Buhari's public reappearance and return to Nigeria from the UK in August 2017. The first identified online appearance of the clone conspiracy theory was a YouTube video created by Nnamdi Kanu, leader of the Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB), a secessionist group in southeastern Nigeria, in September 2017. The group had been seizing opportunities during election windows to insert itself into broader political debates by whipping up regional sentiments of marginalisation and political apathy. It had used a range of mainstream and social media channels to call the attention of the international community to its agitations and illegal detention/trial of its leader. The body double conspiracy theory was picked up in the Nigerian media and widely spread through different forms of popular communication in Nigeria, resulting in Buhari publicly acknowledging and confronting the conspiracy theory. On 2 December 2018, Buhari insisted during an event in Poland: ‘It’s [the] real me, I assure you’. The IPOB leader responded, tweeting:

If Buhari is not dead and replaced by Jubril from Sudan, why won't the Nigerian government sue Eric Joyce, a former British lawmaker for peddling lies? They can’t because they know I am speaking the truth. @AsoRock @ericjoyce @NGRPresident @UKParliament @NGRSenate @WhiteHouse https://t.co/qqrKHPmtNy

The arguments and analyses we advance here are closely related to those we presented in a previous article (Gagliardone et al., Citation2021), where we empirically illustrated how this explorative, rather than normative, approach allows us to grasp how individuals do not simply fall for, embrace or support a conspiracy theory, but can ‘do’ specific and distinct things with/through them. In that article, we comparatively analysed how conspiracy theories circulating at the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic were seized by some Nigerian users and politicians as opportunities to criticise the ruling party, while in South Africa the same conspiracy theories became a vehicle to voice deep-rooted resentment towards the West and corporate interests.

We see the present article as an opportunity to expand some of our thinking, incorporating new evidence and reflecting on some observations made in response to our work. The most common remark we received on previous work was that such an explorative approach might encourage an ‘anything goes’ mentality, in the absence of normative frameworks from which to assess the content and potentially negative consequences of specific conspiracy theories. These, and similar comments, helped us reflect on our positions. We interpret the research presented here as a chance to clarify them – not in defence of our work – but to offer additional and sharper tools to understand the role and implications of conspiracy theorising for communicative and political practices in different societies globally.

This article seeks to do so empirically and conceptually, bringing this work into the broader conversation around ‘decolonising the Internet’ in this special issue. Empirically, we offer a detailed analysis of this conspiracy theory that circulated in Nigeria between 2018 and 2019 purporting that Nigerian President Buhari had died in 2017 and the man who was sitting in office was his ‘clone’. While conspiratorial narratives about clones often feature elsewhere, notably within the spectra of Qanon narratives that have gained much media attention in recent years (Mell-Taylor, Citation2021), this conspiracy theory was distinctly concerned with Nigerian politics and political power. Conceptually, our analysis builds on scholars who similarly look outside of Western contexts in order to understand the nature and roles of conspiracy theories within local and global political realities (Bastian, Citation2003; Fassin, Citation2011). Our analysis intersects with Achille Mbembe’s work on the perpetration and contestation of power in the postcolony to illustrate how it is possible to adopt alternative forms of normativity that, while eschewing the stigmatisation and exclusion that has prevailed in most of the literature, still offer evaluative frameworks to locate conspiracy theories in relation to other forms of expression proliferating in contemporary digital environments. We consider in particular Mbembe’s argument that, while the humorous, excessive and grotesque have been important – even essential – in contesting power in conditions marked by profound inequalities, an exclusive/disproportionate reliance on them may result in the ‘mutual ‘zombification’ of both the dominant and those apparently dominated’ (Mbembe, Citation2001, p. 104). This is especially the case in situations where these forms of expression come to characterise the very relationship between ordinary citizens and those in positions of power, and how they address – or dismiss – one another. As Mbembe continues, ‘this zombification means that each has robbed the other of vitality and left both impotent’ (Mbembe, Citation2001, p. 104). This process is apparent in – many – conspiracy theories, characterised often as excessive/extreme forms of contestation that seek to strip power of its authority and legitimacy, but receive dismissal and condescension in return, often leaving the actors engaged, or called upon in their claims, in the same positions, but less able to command each other’s attention.

With this, our article is guided by two interlinked questions. First, how can scholars approach normative studies of conspiracy theories as part of a broader project of decolonising the Internet? And, second, taking this agenda forward, how can postcolonial and decolonial theories, including Mbembe’s analysis of the zombification of the public sphere, help in nuancing and expanding normative perspectives on conspiracy theories both within and beyond the postcolony? We can thus say that, if our previous work examined what people ‘do’ with conspiracy theories, this article shifts the focus to what conspiracy theories (can) ‘do’ to people, or more broadly, to social formations where these types of contestation and communication become more frequent, accepted and pervasive. The ‘mutual zombification’ identified by Mbembe is only one possible outcome of contemporary digital politics characterised by new forms of epistemic contestation globally. It is apparent in the ‘Buhari is a clone’ conspiracy theory, where extreme forms of contestation and critique – claiming the president has been replaced by a body double – gain currency when other, more ordinary and direct ones – attacking the president’s choice to fly to a foreign country for medical treatment – have lost, or never had, the capacity to grab the attention of the powerful and hold them accountable. It is not, however, a process that necessarily occurs for any conspiracy theory. Conspiracy theories of the kind researched by Drążkiewicz (Citation2021), for example, involving categories of citizens that have been failed by a national health system, and developed a deep-rooted distrust in it as a result, respond to a different, protective, logic. Zombification as a theoretical intervention, as developed in this paper, provides a useful addition to the conceptual and normative repertoire of those studying conspiracy theories, existing in-between the poles of dismissal/condemnation and pure (and often exotic) curiosity/acceptance of what is being said.

2. Theorising conspiracy theories

In both popular culture and academia, conspiracy theories have tended to evoke two distinct reactions. The first is dismissal and refusal. It pitches believers in conspiracy theories as ‘others’, individuals with delusional thoughts who prefer a flawed understanding of reality over the power of evidence and the complexities of scientific method. The second recognises the potential appeal of conspiracy theories (of some more than others) for people who engage with them; and in the case of researchers, encourages enquiries on the relational aspects of conspiratorial thought, focusing on social, cultural, and political factors that influence its emergence and diffusion.

Jaron Harambam, examining how these two tendencies have played out in academic debates, grouped them under the rubrics of stigmatisation and normalisation. The stigmatising approach tends to be normative and foregrounds pathological aspects of conspiracy theories, following what he describes as a ‘tripartite pathology model’: bad science combined with paranoid politics forms great societal danger (Harambam, Citation2020, p. 12). The normalisation approach regards conspiracy theories more neutrally and seeks to explore their meaning. It is moved by the aspiration to explain why a specific conspiracy theory originates and takes roots among individuals and communities.

If we are to grasp what they are about and why so many people nowadays engage with these alternative forms of knowledge, then we need to go further than merely dismissing these ideas as pathological. Then we should explore the reasons people have to follow conspiracy theories without the need to disqualify or compare them to certain moral or epistemological standards. When the objective is understanding, what else should we do than engage with the people actually following conspiracy theories so that we can find out why they find these alternative explanations of reality more plausible than those offered by mainstream epistemic institutions, such as science, media, politics, religion (Harambam, Citation2020, p. 19).

While Harambam’s categorisation builds on research mostly in the fields of sociology, anthropology, and psychology, Buentin and Taylor’s speaks especially to debates among philosophers and political scientists. Both classifications, however, have common roots, and serve similar purposes. They evidentiate and take issue at the values and arguments that informed early debates on conspiratorial thought and illustrate how they continued to influence attempts to study conspiracy theories.

Conspiracy theories are not a twentieth-century phenomenon, but they acquired a particularly bad name in that century, especially with works by Karl Popper and Richard Hofstadter. Popper’s The Open Society and its Enemies (Citation1945) and Hofstadter’s The Paranoid Style in American Politics (1966) can be considered the precursors of the stigmatisation/generalist takes on conspiracy theories, identifying conspiracy theories as pathological. Popper suggested conspiracies are rare and rarely successful. Hofstadter suggested that conspiracy theorising takes place within a modest minority of the population; it is a persistent psychic phenomenon that is unaware and resistant to learning from history about how things do not happen. More contemporary versions of these critiques of conspiracy theorising identify it as ‘unscientific’ and even ‘dangerous’ (van der Linden, Citation2015). Cass Sunstein and Adrian Vermeule (2009) locate conspiracy theories within a ‘crippled epistemology’, originating from isolated epistemic communities.

The – more recent – normalisation/particularist approach contests the framing of conspiracy theories as ‘the irrational and extremist opposite of modern science and democracy’ (Harambam, Citation2020, p. 17), suggesting instead to examine the rationality of conspiracy theories on an individual basis. The plots denounced by some conspiracy theories, in the end, turned out to be true (including the Watergate scandal, the CIA mind-control programme MK-Ultra, the FBI’s counterintelligence programme COINTELPRO, or the Iran-Contra Affair – see e.g., Olmsted, Citation2019). A particularist take on conspiracy theories does not go as far as to suggest that since some conspiracy theories ended up offering a more accurate description of events than more widely accepted explanations, conspiratorial thinking should be appeased or uncritically accepted. It warns of the risks of too easily erasing some types of explanations, the communities embracing them, and possible other – less conspiratorial or non-conspiratorial – arguments connected to conspiracy theories as unworthy of consideration.

This position is taken even further by scholars (Carey, Citation2017; Dole, Citation2021) stressing how all critical thinking entails a degree of conspiratorial reasoning. This tension is often downplayed in most academic literature but is also shared, in a different form, by decolonial theorists and anthropologists referring not directly to conspiracy theories but to the epistemic instability that has tended to characterise the postcolony (Kimari & Parish, Citation2020; Mignolo & Walsh, Citation2018; Udupa et al., Citation2021). This instability is one of the outcomes of the imposition of Western rationality through force in the colonial period, in ways that have inevitably generated tension with other sources of knowledge employed to explain the social and the natural world, making epistemic instability not the exception, but the norm. Indigenous, non-secular, or subaltern forms of knowledge production have always had to negotiate and compete with instrumental Western scientific rationality since the colonial era and given the multiplicity of epistemic authorities. As Fassin (Citation2011) illustrated in his analysis of debates around HIV/AIDS in South Africa, this suspicion does not manifest itself only in the margins, but can also be embraced by governments and political leaders, and be deeply entwined with, and reflect, the anxieties and inequalities of colonial and post-colonial international relations. Expanded in the next section, we suggest knowledge production from outside of the West, in places and among scholars who have long been confronted with the particularity and contradictions of Western scientific rationality, offers alternative approaches from which to explore the nature and contribution of conspiracy theories from the post-colony. In particular, we rely on Mbembe’s work on power relations and contestation in the postcolony as a way to advance a different form of normativity that, while removing the moral disdain implicit in generalist approaches, can still identify and acknowledge conspiracy theories’ potential to deplete trust between political actors and opportunities to promote meaningful change.

3. Conspiracy theories in/from the postcolony

When studying conspiracy theories in Africa, two options can present themselves, critically captured by Mbembe’s quote below. One is to pigeonhole research conducted in or on Kenya, the DRC, or Cameroon under the rubric of the case study, offering a glimpse of how ‘things’ work in Africa. The other is to acknowledge and leverage the complex position Africa has occupied normatively, conceptually, and geographically in knowledge production, as a way to unlock new pathways for research, which can be relevant at local and global levels.

As a name and as a sign, Africa has always occupied a paradoxical position in modern formations of knowledge. On the one hand, it has been largely assumed that ‘things African’ are residual entities, the study of which does not contribute anything to the knowledge of the world or of the human condition in general. Rapid surveys, off-the-cuff remarks, and anecdotes with sensational value suffice. On the other hand, it has always been implicitly acknowledged that in the field of social sciences and the humanities, there is no better laboratory than Africa to gauge the limits of our epistemological imagination or to pose questions about how we know what we know and what that knowledge is grounded upon; how to draw on multiple models of time so as to avoid one-way causal models; how to open a space for broader comparative undertakings; and how to account for the multiplicity of the pathways and trajectories of change (Mbembe et al., Citation2010, p. 654).

Is it possible, that as anthropologists, we are more forgiving of half-truths propagated within non-Western societies, as we tend to see them as a symptom of non-Western status: yet another incarnation of ‘traditional’ occult cosmologies or characteristic of post-socialist, or post-colonial political milieux? Is it possible that due to our own political positionalities we have less patience and understanding for conspiracy theorists whom we encounter at home, because the stakes are ours, not someone else’s? (Drążkiewicz, Citation2021, p. 72).

Equally, this move would be moot without taking diverse forms of communicative practices characterising different locations seriously. The study of conspiracy theories in Africa in area studies sits within a different genealogy, focusing also on theories of rumour and other vernacular modes of communication that people have used to make sense of the world and speak to power (Bonhomme, Citation2016). This implies two logical steps. First, revealing the contradictions of, and breaking the binary between, fact and falsehood popular in contemporary debates on conspiracy theories. Second, decolonising communication theories to move away from simplistic notions of the public sphere, premised on the rational and often idealised Western ideas of communication, to foreground vernacular communicative practices, in ways that do not romanticise or essentialise them, but are aware of their situatedness. This is exemplified by Carey's (Citation2017) examination of the role of mistrust in the Moroccan High Atlas as a shared mechanism to process uncertainty or in Nyamnjoh's (Citation2005) and Hasty's (Citation2005, Citation2006) analyses of the press in Cameroon and Ghana as ostensibly abiding to principles that may be taught in journalism schools in the United States or France, but performing in actuality types of narration that are deeply aware of localised forms of belonging, identity, and authority.

The first step requires recognising the contradictions and limitations of studying politics within binaries of transparency versus mystery; fact versus fiction; rational versus pathological; modern versus pre-modern. These divide function by obscuring and denying the coeval nature of modernity and pre-modernity, West and Other, compartmentalising them geographically and temporally (Fabian, Citation1983). Harry West and Todd Sanders (2003) identify a link between conspiracy theories and a contradiction at the heart of contemporary societies. Conspiracy theories – through working with the interplay between hidden meanings and the surface signs of these hidden meanings – are related to the paradoxical promise of modern society to provide more transparency in how power operates. Paradoxical because, despite this promise, power always remains hidden to a degree. Through drawing on ethnographic research into occult cosmologies and rumour at different latitudes (from Korea to the US, from Russia to Nigeria), West and Sanders trace some of the shared characteristics of conspiracy theories:

Although conspiracy theories are not necessarily fully fledged cosmologies, they constitute occult perspectives on the world, for they, too, concern themselves with the operation of secret, mysterious, and/or unseen powers. They, too, suggest that there is more to power than meets the eye. In either case, occult cosmologies and conspiracy theories may express profound suspicions of power. Through them, ordinary people may articulate their concerns that others, in possession of extraordinary powers, see and act decisively in realms normally concealed from view. They may suggest that, in a world where varied institutions claim to give structure to the ‘‘rational’’ and ‘‘transparent’’ operation of power, power continues in reality to work in unpredictable and capricious ways (West & Sanders, Citation2003, p. 7).

Recognising the grotesque, the ridicule, and the excessive in the rulers themselves, and not only, as Bakhtin did, as the means for ordinary people to oppose the dominant culture and find refuge from it, Mbembe remarks on the limits of common references to humour as an expression of resistance. He depicts a scenario where both the rulers and the ruled ‘share the same living space’ and are locked into a relationship where ambivalence and deception prevent critique to effect change. This is the second move enabled by a deeper, even if grimmer, engagement with practices to exert and contest power in the postcolony. One that, rooted in an analysis that encompasses both how rulers and citizens speak to each other – rather than more narrowly celebrating the creative and the humorous in opposing power – also offers the means to normatively assess the consequences of these forms of communication. Rulers project a grandeur that can be ridiculed and accommodated – a paradox that ‘zombifies’ rulers and the ruled with both unable to substantively challenge or change dynamics of power:

‘the contradiction between overt acts and gestures in public and the covert responses made ‘underground’ (sous maquis) … has resulted in the mutual zombification of both the dominant and those whom they apparently dominate. This zombification meant that each robbed the other of their vitality and has left them both impotent’ (Mbembe, Citation2001, p. 104).

4. Zombification as object of study and method: conspiracy theories and the digital in the Global South

The critical historicisation and contextualisation for studying conspiracy theories we are proposing are also meant to respond to a trend that has grown within the study of information disorder online. We refer to how the availability of data on online debates in real time has been leveraged to produce understandings of, and potential solutions to problems perceived as urgent – such as trying to understand the impact conspiracy theories have on people’s vaccination uptake. In fact, for research into the perils of mis/disinformation through the proxy of conspiracy theories to take place, researchers, more or less consciously, have to subscribe to some versions of the stigmatisation/generalist view of conspiracy theories, deploying digital methods in ways that make it more difficult to acknowledge the complexities and socio-political long durée of conspiratorial narratives.

We took a number of steps to avoid reproducing such assumptions about conspiracy theories as exceptional in our methodology and research design. We focus on the popular conspiracy theory that the President of Nigeria, Muhammadu Buhari, was a clone, as an empirical starting point from which to explore in more detail what conspiracy theories can do to people within a specific public discussion. The Buhari-is-a-clone conspiracy theory constellated together wider debates about the power of the President, the government’s relationship to foreign powers, specifically its former coloniser, the UK, and political corruption and distance from the population. Its popularity grew to a point where the President publicly acknowledged its circulation by denying its veracity. This conspiracy theory proves particularly interesting as, while it did not dominate public debate, it was widespread among Nigerians and had a ‘staying power’, in other words, it was picked up at different points in time. Equally, despite this, it did little to undermine Buhari’s position of authority. Conspiratorial narratives were rather absorbed within political debates characteristic of the turbulent public debates in Nigeria.

To empirically explore the evolution, reach, and consequences of the Buhari-is-a-clone conspiracy theory, and especially its digitally mediated dimensions, we focused on discussions on the conspiracy on Twitter. Twitter has played a central role as a place for political discussion and debate in Nigeria, evident on one side in President Buhari’s choice to ban Twitter in June 2021 following Twitter’s takedown of one of his Tweets, and on the other side, its active use as part of mass protests against police brutality in October 2020. Nigeria’s user base on Twitter was estimated at 4.95 million users in early 2023, out of 31.60 million social media users and a total population of 221.2 million (Kemp, Citation2023). Given these statistics, it is important not to overstate the direct importance and reach of online debates. Nonetheless, Twitter has been an active and growing space for political debate in the country, and as we show in this paper, can give a window into some of the active political discourses in Nigeria.

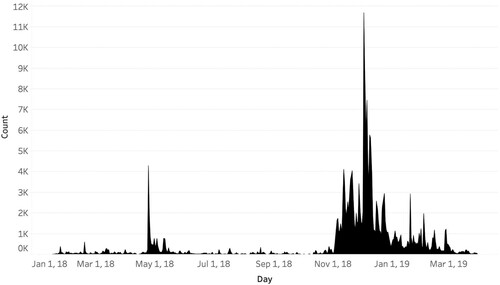

We collected 229,035 tweets published between 1 January 2018 and 3 March 2019 from the Twitter Academic API, using selected keywords [‘buhari clone’, ‘buhari jubril’, ‘buhari body-double’, ‘buhari and medical tourism’]. The time period was selected to allow us to explore how the conspiracy theory evolved over time. Building on a mixed method approach developed previously for our research on conspiracy theories (Gagliardone et al., Citation2021, pp. 4–5), we then combined quantitative exploration of the Twitter data with a more contextual qualitative analysis of how the discussions around the conspiracy theory reflected and mutated in response to political events. shows the overall distribution of the data used for the analysis.

Table 1. Distribution of data analysed.

To facilitate such mixed methods analysis of large datasets, Twitter data was first processed as ‘interaction networks,’ which capture all the interactions of Twitter users (such as retweeting, mentioning, and quoting other Twitter users). The aim of this first stage was to establish an overall picture of the users, interactions and content that constituted public discussion of the conspiracy on Twitter, over time. We analysed and visualised all interactions across the entire dataset as well as temporarily, focusing on time periods when the conspiracy theory was more active in Twitter conversations. shows the time-based distribution of the data, including the frequency of daily mentions of the conspiracy theory across the time period.

From here, to speak to our primary research questions about the normative role of the conspiracy, we focused on qualitative methods to consider popular points of discussion and narrative framings, and to highlight ‘the radical situatedness of online speech acts’ (Pohjonen & Udupa, Citation2017, p. 3051) in how the Buhari conspiracy theory was embedded into the complexities of Nigerian politics, including the 2019 Presidential campaigning and elections. This involved identifying and interrogating patterns in narratives that circulated, which surfaced as most popular, by whom and how they were situated within wider political events and power contests. Finally, in the qualitative analysis, we focused on the applicability of Mbembe’s work on power in the postcolony to provide a more contextual understanding of conspiracy theories and what they do to specific socio-political contexts and during key events.

5. President Buhari, the clone?

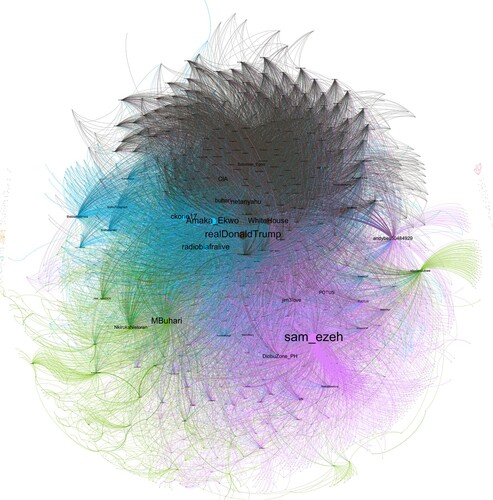

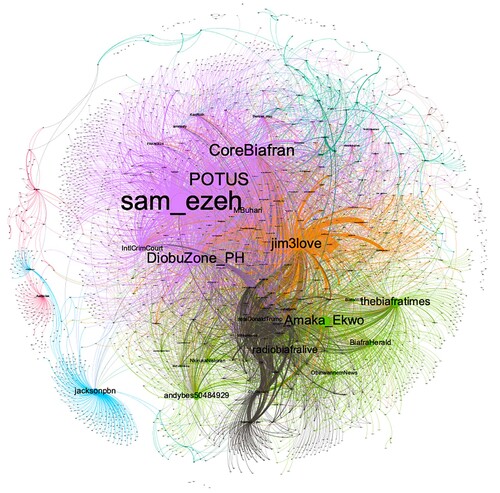

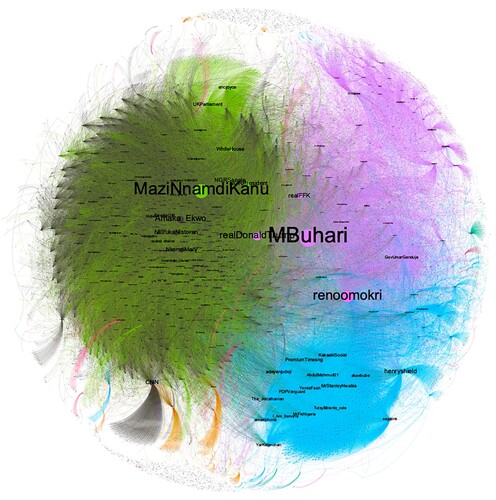

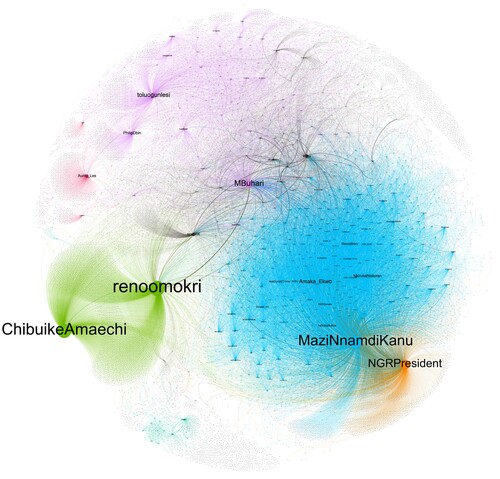

As indicated at the onset of this paper, in 2017 the conspiracy theory that the person sitting in the Presidential office was Buhari’s clone arose following the President’s return from the UK. The conspiracy theory reflected political concerns and unrest: it reflected fears of a power vacuum, as had occurred following the unexplained death of a president less than a decade earlier. It was first publicly shared by Nnamdi Kanu, leader of a secessionist group in southeastern Nigeria. In and the accompanying text below, we show the key events around which this conspiracy theory received active engagement in Nigerian public conversations and the various political factions and communities on Twitter that became involved (January – April 2018 (), May – August 2018 (), September – December 2018 (), and January – April 2019 ()).

Reflected in , initial conversations were targeted at advancing IPOB’s agenda through dedicated accounts operated by Biafra activists. The conspiracy theory was broadcast through IPOB media accounts with tweets seeking Western interest/involvement, mentioning personalities and institutions like Donald Trump, Theresa May, the White House, Amnesty International, Benjamin Netanyahu, and the International Criminal Court. Later, a number of Biafra media outlets amplified the conspiracy theory during the presidential campaigns, calling for a boycott of the election via a sit-at-home directive to its members.

and show a shift from the call for secession, to the conspiracy theory invoked with election-related content. This shift is evident in the entrance of partisan politicians in the conversations. In , on the left-hand side, there is a large mix of accounts representing IPOB, IPOB media and influencer accounts, the Office of the President of Nigeria and the Senate. Bottom right is populated by local media organisations, politicians, social media influencers. Prominent in the purple cluster were President Buhari and Donald Trump (due to high mentions), and opposition (PDP) politicians, Reno Omokri and Femi Fani Kayode, who seized the conspiracy theory as an ammunition for electoral goals.

in particular shows a shift in discourse around the conspiracy theory. It offers a unique outlook on the conspiracy theory at a point when the government unleashed its information machinery – in other words, government-supported influencers, media aides, party spokespersons – to counter and diffuse the tone of the conspiracy theory. It showed distinct clusters pursuing parallel political agendas. On the bottom right, in blue and mustard yellow, the IPOB community and the Presidency were engaged in debates over the legitimacy of the conspiracy theory, with the IPOB leader steering the narratives. On the top left, in purple, is a community dominated by President Buhari and his media aides, as well as a community in green, which featured Rotimi Amaechi, the Director-General of Buhari’s 2019 Presidential campaign, and popular opposition critic, Reno Omokri.

also includes a sharp peak in tweets about the conspiracy theory on 3 December 2018 (producing 11,682 tweets). This was a peak period in the presidential election campaigns. During this period, Buhari acknowledged and responded to the conspiracy theory, affirming ‘it’s the real me, I assure you’, and addressed the authors of the conspiracy theory as ‘ignorant and irreligious’. His statement sparked discussion. One of Buhari’s targets with his statement was IPOB leader, Nnamdi Kanu, who had been discussing and raising popular support for the clone conspiracy theory while based outside of Nigeria, through outlets including Biafra radio, Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube. Kanu was critical of Buhari’s administration. He accused it of bias for not addressing persistent crises that were resulting from tensions and clashes between herders and farmers in Nigeria, especially in the South-east and South-south regions. Kanu had fled Nigeria in 2017 after his home was invaded by the military and he was arrested for ‘inciteful remarks’ against the government and threatening Nigerian people and security personnel in his Radio Biafra broadcasts.

Looking across the time period, particular concerns and interests underpin the conspiracy theory. First, much content took a satirical tone, adding colour and suspense to political discussion, as illustrated in the tweets reported below.

So, I heard buhari is a clone. Maybe we do have change after all #NigeriaDecides2019.

‘I have imposter syndrome.’ – Sudanese Clone Jubril (Jubril from Sudan: ‘Buhari’).

I can report authoritatively that representatives of the Jubril family, having discovered the gigantic swindle, suddenly showed up in Abuja the other day and demanded to be compensated with a power-sharing arrangement at the federal level in perpetuity and demanded to be compensated with a power-sharing arrangement at the federal level in perpetuity, plus 50 percent of Nigeria’s oil revenues for ten years in the first instance. Failing this, they warned, they would tell their story to the whole world.

Whoever believes buhari was in Paris needs to think again, that was his pic when he attended world climate change event that they photoshopped there, look at the badges of other world leaders and notice the difference, we have Jubril-Buhari from Sudan in the Villa.

But come to think of it. Buhari that looks very frail, always going for medical check up in London hospital all of a sudden became hale and hearty. My mind is telling me something. Should I believe it?. That who is currently occupying the villa is jubril from Sudan?

Na separation be the best solution for this country las las not atiku or buhari, Britain way colonize us with all civilization etc they are not one. watin I know_

This is Aminu JUBRIN from Sudan impersonating #DeathBuhari in Nigeria COURTESY BRITISH-GOV @secgen @_AfricanUnion @UN @GermanyUN @EUCouncil

Don't trust British because they are betrayals. Buhari is owned and covered up by British. Why is Jubril still Nigeria president as impostor?

Finally, especially towards the latter end of our dataset, discussion took an increasingly politicised tone, reflecting the upcoming Presidential elections.

Buhari’s campaign for reelection in 2019 faced challenges surrounding his lack of progress in addressing both high-level corruption and economic recession. His capacity to effectively govern formed part of these critiques; with this, clone conspiracy easily entered into media and opposition narratives. The conspiracy featured in popular tweets by opposition political actors, used to undermine the President’s legitimacy to contest in the 2019 elections; displaying, as seen elsewhere in Nigeria’s twittersphere (Gagliardone et al., Citation2021), how political opportunism can make use of conspiracy theories not to advance support for alternative interpretations of social reality, but as political ammunitions. Echoing the ‘Birther Movement’ in the United States – which claimed that Barack Obama was not a US born citizen and his birth certificate was a forgery – some opposition figures claimed President Buhari was not qualified to run for the presidency as a clone. One tweet suggested: ‘Is like the President Muhammadu Buhari we voted died in a London hospital long ago. From all indications, the Buhari we have now is a clone one.’ While Buhari was re-elected, this use of the conspiracy theory contributed to wider efforts to de-legitimise his candidacy. Further, the elections themselves raised challenges for the legitimacy of Nigeria’s electoral process, with a very low voter turnout of 35.6%, indications of voter irregularities, and violence particularly in the North-east.

6. Zombification of Nigeria’s digital public sphere

The conspiracy theory that Buhari is a clone offers several entry points from which to consider the value of working with Mbembe’s arguments to explore alternative forms of normativity that can be adopted to analyse conspiracy theories. Similar to Mbembe’s remarks on the carnivalesque nature of the commandemant, the Buhari-is-a-clone conspiracy theory is part of a dynamic discussion where humour is deployed as a tool to critique power. From the onset, there was space for the conspiracy theory to be grappled with from different perspectives: to contend with political corruption, to express discontent, to promote political competition to President Buhari. Users actively engaged with the conspiracy theory to question the President’s legitimacy, from humorous comments to more serious suspicions about his abilities and trustworthiness. By recognising the conspiracy theory and denying it, Buhari affirmed its presence within the public space.

Within this frame, upon identifying the Buhari-is-a-clone conspiracy theory, and its humorous undertones, is it possible also to assess its normative implications? What effect does humour have on the exercise or contestation of power? Or on the agency of citizens to hold the political elite to account?

While satirising the President, the conspiracy theory drew attention to, and seemed to reinforce, the powerlessness of Nigerians vis-a-vis the President, and both Nigerians and their President in relation to Nigeria’s former colonial power. Claims that the President was a clone were possible within the distance between ordinary Nigerians and political elites. This was not the first President to go abroad for health treatment. It also appeared believable that information about the President’s condition was more readily accessible in the UK than in Nigeria. From here, the conspiracy theory emerged as a two-edged sword: a display of power and distance from the ordinary Nigerian, while subjecting the President and Nigerians to power outside of country borders. Mistrust linking back to the recent history of colonialism gave further plausibility to the conspiracy theory. Political intrigue and corruption are not unexpected among Nigeria’s political elite.

As the conspiracy theory exposed limits of Presidential power and reinforced the relative powerlessness of ordinary Nigerians, its effects in the public debate give way to Mbembe’s concerns about what the grotesque and the humourous can do to struggles for political change. As it continued to circulate, the conspiracy theory seemed impotent to change the course of political events, leading instead to a ‘zombification’ of the political debate. The conspiracy theory mocked the President, and, even if it was drawn into electoral debates, it did little to challenge the social formations that hold power in Nigeria. The conspiracy theory was viral, but largely ineffective.

From this perspective, following Mbembe in working from an empirically grounded account of a conspiracy theory as the premise for considering its normative implications helps to avoid reifying or rejecting conspiracy theories. Instead, there is space to consider conspiracy theories within the world as it is shaped by colonial legacies. The apprehension surrounding Buhari’s long stay in the UK, the unequal access to knowledge, the hidden nature of power are perhaps less surprising from a view of the colonised world. Equally relevant, we suggest, is Mbembe’s approach to making sense of why these particular forms of contestation seem to do little to change structures of power.

Still, with this normative assessment of the Buhari-is-a-clone conspiracy theory as making contestation impotent or ineffective, we do not intend to suggest its generalisability to every form of contestation. Such an argument would suggest change is impossible. In Nigeria, alongside the Buhari-is-a-clone conspiracy theory, other, more radical, forms of political contestation emerged. In October 2020, the EndSARS protests against police violence gave way to a new dynamic critique of state institutions online and on the streets. Online, the networks of users that became increasingly visible during the EndSARS protests continued to grow in influence, underpinning Peter Obi’s 2023 candidacy for presidency. At the least, this rising community indicates the potential for points of disruption to social and political formulations, which do not fit into a conceptualisation of an impotent, ‘zombified’ contestation of power.

Instead, through this analytical opening, we aim to move away from generalist framings that exceptionalise conspiracy theories and locate them outside legitimate political discourse. Suspiction, satire, mockery an important dimensions that exist within Nigeria’s digital public sphere, and analytical and normative tools need to be generated to assess their role, relevance, and implications.

7. Conclusion

Much study of conspiracy theories within ‘modern publics’ is framed by a normative concern for conspiracy theories as an aberration, external to the ideal liberal public sphere. Contextually bounded studies of what conspiracy theories actually do in different situations step outside of these normative claims. However, they also can leave unchallenged the generalist views of conspiracy theories as an aberration to modern reasoning and rationality. This article has attempted to navigate this challenge and carve out an expanded space and rationale from which to empirically and conceptually study conspiracy theories in/from a decolonial context. The spaces we have sought to expand through our conceptual interventions focus on what conspiracy theories actually do to/with political power, and the potential for achieving meaningful/concrete changes to who exercises power over whom. Conceptually, we argued Mbembe’s ‘zombification’ approach, addressing the effects of excessive and grotesque forms of communication/contestation provides a viable alternative to generalist and particularist approaches to conspiracy theories, as it better engages with the many contradictions of modernity and their manifestations within the postcolony. We then empirically specified this argument through an analysis of the Buhari-is-a-clone conspiracy theory, adopting a situated interpretive approach that highlights what conspiracy theories do to specific social formations. We examined how people engaged with the conspiracy theory in different, and sometimes paradoxical ways. This enabled us to descriptively show how the conspiracy theory challenged but also reproduced power in Nigeria: its humorous undertones undercut the President’s legitimacy and its place within the formal public space, but it did not effectively challenge the President's ability to stay in or run for another term in office. We then returned to Mbembe’s ideas to make the case for greater epistemic pluralism in how conspiracy theories are studied, specifically in ways that avoid reproducing (at least some of the) normative eurocentric assumptions about modernity.

Looking beyond this case, we conclude by asking what potential might there be for this addition to the available repertoire of conceptual approaches to conspiracy theories beyond the postcolony. Could similar dynamics of zombification be at play elsewhere, such as in the memetic mockeries of Donald Trump? What could be gained, both theoretically and empirically, by highlighting conspiracy theories not as exceptional, but as a manifestation of the multiplicity of ways in which people make sense of the secrecy and superficiality of power? Could Mbembe’s ideas help to make sense of other times and places whereby conspiracy theories are absorbed into formal political discourse? Conversely, identifying tendencies towards zombification might help to clarify moments when conspiracy theories might contribute to change, helping to make sense of differing possibilities of challenging power despite their often eccentric and eclectic claims to knowledge.

Taking a decolonial lens to the study of conspiracy theories not only shows the problems of dominant approaches but also expands the space available for critical researchers to engage with ideas and experiences of the colonised world. The questions raised in this article also extend to the methodologies used to understand conspiracy theories in the digital environments where conspiracy theories now predominantly circulate. Could we envision a more decentered form of internet studies that takes seriously the challenge of decolonial thinking to interrogate its object of study through the prism of alternative (and arguably more contextually relevant) conceptual apparatuses? If Mbembe’s theory of zombification can be adopted to investigate conspiratorial narratives in large-scale Twitter conversation in Nigeria (rather than resorting by default to theories developed in the US or Europe), why not exploring its potential to assess similar phenomena in Finland, Italy, or the UK? Might this provide new ways to shed light on the multiple roles that conspiracy theories play within different contexts globally, challenging researchers to take a more open approach to conspiracy theories across the ‘modern’ world? From here, then, we return to the challenging question posed by Drążkiewicz (Citation2021) earlier: can researchers move past the unease of considering conspiracy theories as part of normal political discourse close to ‘home’ – noting specifically the Western world that dominates academic publishing – and engage in a more empirically grounded, contextually specific form of normative theorising about the growing global unease about unbridled digital communication?

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Iginio Gagliardone

Iginio Gagliardone is Associate Professor in Media Studies at Wits University and has been leading several projects on the emergence of distinctive conceptions of the information society in the Global South. His work connects science and technology studies, international relations, and media studies.

Matti Pohjonen

Matti Pohjonen is a Senior/University Researcher for the Helsinki Institute for Social Sciences and Humanities (HSSH), University of Helsinki, leading methodological development on using internet and social media data and on social science and humanities debates related to generative AI.

Stephanie Diepeveen

Stephanie Diepeveen is a Research Associate in Politics and International Studies at the University of Cambridge, and a Senior Research Fellow at ODI. Her work sits at the intersection of political studies and media and communications, with a focus on practices and possibilities of decolonial approaches.

Samuel Olaniran

Samuel Olaniran is a Postdoctoral Researcher in the School of Communication, University of Johannesburg, and a Researcher at Media Cloud. His work focuses on developing critical approaches to understanding the intersection of politics and technology, democracy, and mis/disinformation.

References

- AlSayyad, Y. (2020, October 26). What foreign journalists see in the U.S. election. The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/news/video-dept/what-foreign-journalists-see-in-the-us-election

- Bastian, M. L. (2003). ‘Diabolic realities’: Narratives of conspiracy, transparency, and ‘ritual murder’ in the Nigerian popular print and electronic media. In H. G. West & T. Sanders (Eds.), Transparency and conspiracy: Ethnographies of suspicion in the new world order (pp. 65–91). Duke University Press.

- Bonhomme, J. (2016). The sex thieves. The anthropology of a rumor. Hau Books.

- Buenting, J., & Taylor, J. (2010). Conspiracy theories and fortuitous data. Philosophy of the Social Sciences, 40(4), 567–578. https://doi.org/10.1177/0048393109350750

- Carey, M. (2017). Mistrust: An ethnographic theory. Hau Books.

- Comaroff, J., & Comaroff, J. L. (2012). Theory from the South: Or, how Euro-America is evolving toward Africa. Anthropological Forum, 22(2), 113–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/00664677.2012.694169

- Dentith, M. R. (2018). Taking conspiracy theories seriously. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Dole, A. (2021). Critical theory, conspiracy, and ‘gullible critique’. In M. D. Eckel, C. A. Speight, & T. DuJardin (Eds.), The future of the philosophy of religion (pp. 111–135). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-44606-2_8

- Drążkiewicz, E. (2021). Taking vaccine regret and hesitancy seriously. The role of truth, conspiracy theories, gender relations and trust in the HPV immunisation programmes in Ireland. Journal for Cultural Research, 25(1), 69–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/14797585.2021.1886422

- Fabian, J. (1983). Missions and the colonization of African languages: Developments in the former Belgian Congo. Canadian Journal of African Studies / Revue Canadienne des études Africaines, 17(2), 165–187. https://doi.org/10.1080/00083968.1983.10804016

- Fassin, D. (2011). The politics of conspiracy theories: On AIDS in South Africa and a few other global plots. Brown Journal of World Affairs, 17(2), 39–50.

- Gagliardone, I., Diepeveen, S., Findlay, K., Olaniran, S., Pohjonen, M., & Tallam, E. (2021). Demystifying the COVID-19 infodemic: Conspiracies, context, and the agency of users. Social Media+ Society, 7(3), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051211044233

- Harambam, J. (2020). Contemporary conspiracy culture: Truth and knowledge in an era of epistemic instability. Routledge.

- Hasty, J. (2005). The press and political culture in Ghana. Indiana University Press.

- Hasty, J. (2006). Performing power, composing culture. Ethnography, 7(1), 69–98. https://doi.org/10.1177/1466138106064591

- Hofstadter, R. (1966). The paranoid style in American politics and other essays. Knopf.

- Kemp, S. (2023, February 13). Digital 2023: Nigeria. DataReportal – Global Digital Insights. https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2023-nigeria

- Kimari, W., & Parish, J. (2020). What is a river? A transnational meditation on the colonial city, abolition ecologies and the future of geography. Urban Geography, 41(5), 643–656. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2020.1743089

- Mbembe, A. (2001). On the postcolony (Vol. 41). University of California Press.

- Mbembe, A., Comaroff, J., & Shipley, J. W. (2010). Africa in theory: A conversation between Jean Comaroff and Achille Mbembe. Anthropological Quarterly, 83(3), 653–678. https://doi.org/10.1353/anq.2010.0010

- Mell-Taylor, A. (2021, February 25). The world of Far-right social media thinks everyone is a clone. Medium. https://alexhasopinions.medium.com/the-world-of-far-right-social-media-thinks-everyone-is-a-clone-ec7fc52ab2df

- Mignolo, W. D., & Walsh, C. E. (2018). On decoloniality. Duke University Press.

- Nyamnjoh, F. (2005). Africa’s media, democracy and the politics of belonging. Zed books.

- Olmsted, K. S. (2019). Real enemies: Conspiracy theories and American democracy, World War I to 9/11. Oxford University Press.

- Pohjonen, M., & Udupa, S. (2017). Extreme speech online: An anthropological critique of hate speech debates. International Journal of Communication, 11, 19, 1173–1191. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/5843/1965

- Popper, K. (1945). The open society and its enemies. Routledge.

- Robertson, D. G. (2017). The hidden hand: Why religious studies need to take conspiracy theories seriously. Religion Compass, 11(3–4), e12233. https://doi.org/10.1111/rec3.12233, 1–8.

- Skinner, J. (2000). Taking conspiracy seriously: Fantastic narratives and Mr Grey the Pan-Afrikanist on Montserrat. The Sociological Review, 48(2_suppl), 93–111. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.2000.tb03522.x

- Sunstein, C., & Vermeule, A. (2009). Conspiracy theories: Causes and cures*. Journal of Political Philosophy, 17(2), 202–227. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9760.2008.00325.x

- Udupa, S., Gagliardone, I., & Hervik, P. (2021). Digital hate: The global conjuncture of extreme speech. Indiana University Press.

- van der Linden, S. (2015). The conspiracy-effect: Exposure to conspiracy theories (about global warming) decreases pro-social behavior and science acceptance. Personality and Individual Differences, 87, 171–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.07.045

- West, H. G., & Sanders, T. (2003). Transparency and conspiracy: Ethnographies of suspicion in the new world order. Duke University Press.