ABSTRACT

In an age of digitalization, who still refuses to use digital technology? Drawing on nationally-representative Chinese General Social Survey data, this article finds that about half of Chinese households do not actively use the Internet or e-payment systems, despite their ubiquity. This article estimates the effects of socioeconomic resources on these technologies’ (non-)use across urban, resident but previously urban, resident but previously rural, and rural hukou household registrations in China. Educational attainment is associated with higher odds of use among rural hukou, but the size of this effect is nearly double compared to urban hukou. Additionally, being female increases the odds of use among urban and resident but previously urban hukou, and lowers the odds of use in rural hukou, but which are attenuated by the mediating effects of education. The results give credence to education as a direct and indirect mechanism for digital skills development, especially for rural households. Individuals proximal to rural living conditions have fewer opportunities to learn about digital technology, resulting in greater dependency on education as a rare source of skills training. Simultaneously, education indirectly creates opportunities for women to learn digital skills by improving chances for higher-status job participation that require information management skills, especially in rural regions where traditional cultural norms constrain opportunities for upward mobility. Ultimately, digital technology non-use is traced not to lack of interest, but to lack of skills development opportunities among the socioeconomically disadvantaged.

Introduction

The proliferation of mobile connectivity has occupied the core of the broader shift of digitalization that has reorganized advanced capitalist economies worldwide over the past twenty years. This is especially so in China, where digital connectivity has reached new heights that serve as the inspiration for other regions worldwide.

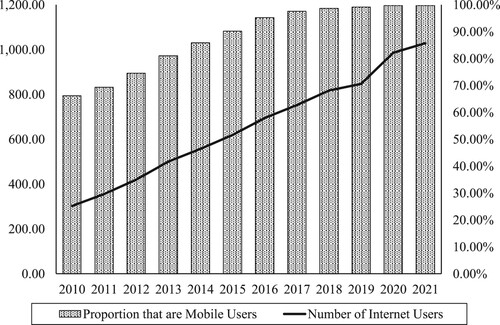

Using data from the China Internet Network Information Center (CINIC), China’s state-run agency responsible for managing online domestic registry data, shows the number of Internet users has apparently risen from 302.73 million in 2010, to 619.81 million in 2015, to 1.028 billion by 2021. Much of this massive rise has been concomitant with the proliferation of mobile devices. Indeed, the proportion of users accessing the Internet using mobile devices has risen from 66.2% in 2010, to 90.1% in 2015, and finally to above 99% by 2019, a level maintained through to 2021.

Figure 1. Number of Internet users in China and the proportion of users who access Internet using mobile devices. Source: Author’s calculations using data from China Internet Network Information Center.

The totalizing sweep of mobile connectivity through the world economy in general and China in particular has reshaped the bases of social and economic life in the household economy. The wide use of social networking sites like Weibo and the use of e-payment systems through mobile-based apps like WeChat pay and Alipay have served as grounds for discussion by academics, pundits, and government officials alike.

Within this scope, there is a well-established body of empirical research that has identified the advantages of Internet access and household participation in mobile connectivity. Internet use has been found to improve access to news, job postings, and work-related information (Castellacci & Viñas-Bardolet, Citation2019; Gürtzgen et al., Citation2021) to the effect of improving job satisfaction (Denzer et al., Citation2021).

Similarly, the ability to use e-payment systems improves inclusive finance, proffering access to entrepreneurship in newly emerging commons economies and marketplaces of exchange on platforms like AliExpress and exposure to financial products and services (Hasan et al., Citation2022), especially for historically disadvantaged populations like rural Chinese citizens who struggle to migrate and integrate into urban regions (Li et al., Citation2022; Yin et al., Citation2019). These benefits extend to social life, where scholars have identified multiplying forms of sociality among users who use mobile Internet apps and devices to foster community in social spaces like romantic fields, school, and the workplace (Au, Citation2022; Chan, Citation2021; Greiffenhagen et al., Citation2022).

This article examines an overlooked segment of the totalizing sweep of mobile connectivity: those who do not use digital technology. Focusing on the usage frequency of Internet and e-payments, this article presents a systematic account of the extent of digital technology (non-)use and estimates the effects of socioeconomic predictors of (non-)use at the individual level.

Analyzing data from the latest 2017 Chinese General Social Survey, a nationally representative survey of China, this article interrogates the unequal distribution of digital technology skills development, accounting for potential direct and indirect effects of education as a proxy, across fine-grained types of hukou.

Hukou registrations are effectively types of citizenship assigned to Chinese households based on their city or locality (e.g., which part of a city or province) of birth. Introduced in the mid-1900s to restrict migration within China, two types are most common: urban (feinongye) and rural (nongye) hukou. More recently, an experimental policy reform has introduced to certain cities a new combined type of ‘resident’ (jumin) hukou registration, into which citizens are transitioned. Each type of hukou is replete with specific rights of access to social services, mobility, and labor markets, giving rise to restrictions on life chances.

Parsing out differences in digital technology use rates across types of hukou, this article presents a sociological account of digitalization as grounds for exacerbating deprivation among the socioeconomically disadvantaged and the root causes underpinning their lack of digital technology use.

Digital exclusion and inequality in China

Demographic covariates of digital technology use and digital skills

Digital technology use has served as an influential research agenda in the study of inequality and development in economics and sociology, as the provision of government services, the labor market, and consumer purchases continue to move toward digital platforms in advanced capitalist economies.

The technical competency to use digital technologies, like interacting with others and communities online or searching/organizing multiple sources of information needed to use digital platforms, is commonly referred to as digital skills (Lewin & McNicol, Citation2015). These skills are associated with several demographic covariates (Hunsaker & Hargittai, Citation2018).

Age

One of the most agreed-upon predictors of digital skills (and digital exclusion) is age. Older adults are less likely to use digital technology. The recency of digital platforms and their integration into school and work precipitate a digital divide across demographic generations, namely, older adults who have fewer opportunities to use digital technology, given their education decades prior or who have phased out of the workforce (Olphert & Damodaran, Citation2013). Through a scoping review, Hunsaker and Hargittai (Citation2018) more explicitly identify cognitive performance and memory as inhibitions, skills that are needed for better Web navigation skills, but incidentally in decline among older adults. Older adults also typically have fewer activities to do online than younger adults, given their diminished social networks (Hargittai & Dobransky, Citation2017).

Put together, despite the myriad health benefits that social media use has for older adults, such as to improve social connections, self-efficacy, and well-being, especially in China (Jiang & Song, Citation2022; Rui et al., Citation2019), there is a general reluctance among older adults to use social media or digital technologies like it (Song & Jiang, Citation2021; Zhou, Citation2019).

Gender

Unlike the evidence for age, evidence for the effects of gender on digital technology use is far more inconclusive, despite its salience in predicting inequality. Men appear more likely to use social media than women in China (Zhou, Citation2019), though explanations for this are mixed. On the one hand, women in China should have higher social media use because of their increased sociality, larger networks, and increased spare time due to the disproportionate amount of time they are assigned to staying in the household for chores (Bian & Ikeda, Citation2018; Gao & Sai, Citation2020). On the other, women suffer from higher rates of deprivation of education, lower income, and segregation in the labor market that relegates them to lower-status occupations outside the purview of the information communication technology sector (Wang & Cheng, Citation2021; Wu & Qi, Citation2017).

Cotten (Citation2017) suggests that even though women should be more social in uses of digital technology, they use digital technology less than men because they have less experience using technology in the workforce. Implicated in her assessment is that inequalities in digital technology use follow existing socioeconomic inequalities, like gendered segregation in the labor market that sorts women in lower-paying and lower-status roles (Tonoyan et al., Citation2020).

Education

Education has a direct effect on digital skills development. In an authoritative systematic review of digital skills training, van Laar et al. (Citation2020) find that education is among the most significant predictors of digital skills. The ubiquity of digital technologies has formalized the training of digital skills in education, both through explicit instruction and through the integration of digital technology in schools as a medium of instruction (Williams, Citation2022). Educational courses often involve Web-based activities like online searching, downloading media, and communication with other users that are necessary for sustained Internet use after graduation, giving rise to large disparities in use between high school graduates and non-high school graduates (Hunsaker & Hargittai, Citation2018). Pick et al. (Citation2015), for instance, find that the college student enrollment ratio and adult literacy rate are reliable proxies of digital skills.

Hukou registrations and inequality

Painting a nuanced sociological portrait of digital exclusion, this article extends research on digital exclusion by situating it in the context of the rural-urban divide in China at the individual level. This study analytically parses out a finer conceptualization of regional residency, namely, across four salient types of hukou registration that capture the spectral orders of social mobility between urban and rural polarities: urban (feinongye), resident (jumin) but previously urban, resident (jumin) but previously rural, and rural (nongye).

The type of hukou determines one’s access to welfare, school registration, and even eligibility for select job categories, typically those in cities. Historically, the concentration of development investments in urban coastal regions, like the Special Economic Zones, has created job markets replete with far more lucrative and diverse job opportunities than inland rural regions. This urban-rural disparity by region trickles down to the individual level through differential access to resources by hukou.

Someone born in central Shanghai is assigned an urban hukou and is entitled to full benefits and jobs in the region. Someone born in a village in Anhui, however, is assigned a rural hukou and is prohibited from migrating to Shanghai unless they apply and gain approval. Should they succeed in migrating, they are still prohibited from applying to high-paying offices or even select social services (Chen et al., Citation2018; Song & Smith, Citation2019). As such, a rich body of evidence identifies a gap in income, occupational mobility, and wellbeing between urban and rural hukou (Chen et al., Citation2018; Song & Smith, Citation2021; Zhong et al., Citation2022).

This article accounts for this traditional binary of urban and rural hukou, in addition to the new resident hukou that combines the traditional urban and rural hukou into a single category (Zhang et al., Citation2019). The urban-rural binary compels a focus on the direct and indirect effects of education. Concomitant with the income inequality that divides urban and rural hukou, this article hypothesizes that,

Hypothesis 1: Individual proximity to the rural hukou is linked to fewer socioeconomic resources in the form of lower educational attainment and digital technology use.

Hypothesis 2: Educational attainment should exert stronger associations with greater digital technology use among individuals, especially women, more proximal to the rural hukou because their level of digital skills starts from a lower baseline.

Thus, though individuals with a new resident hukou enjoy newfound access to resources that they did not under a rural hukou, they are earthbound by the intra-generational effects of mobility. Individuals who move from lower (e.g., rural hukou) to higher classes (e.g., resident hukou) report lower wellbeing than individuals who stay in a higher class consistently, because of the early life effects of poor socioeconomic conditions (Song & Smith, Citation2019). Constraints in education in early life, moreover, have extended effects on life chances that precipitate class-based differences in mortality rates in later life (Dribe & Karlsson, Citation2022).

Data and methods

Data

This article uses the Chinese General Social Survey (CGSS), a nationally representative dataset on the Chinese household population. The survey targets civilian Chinese adults aged 18 or older in China and is administered by the Chinese Statistics Bureau. The CGSS was established in 2003 and regularly surveys over 10,000 households in China to ask about social structures (e.g., perceptions of institutions and inequality), quality of life, and networks, across all regional, geo-administrative, and rural/urban strata (Bian & Li, Citation2012). Surveys were conducted through face-to-face interviews that lasted 1.5 h long, making it a uniquely rich dataset. The present study draws on the 2017 wave, the first iteration with questions about Internet and e-payment system use (N = 12,528).

Measures

To assess the extent of digital technology use, two dependent variables were created. The first is Internet usage over the past six months, based on the CGSS question, ‘in the past six months, have you used the Internet? This includes using computers, smartphones, smartwatches or smart devices, etc.’ Responses were coded into a dichotomous variable: (0) no and (1) yes.

The second is e-payment system usage over the past twelve months, compiled based on two yes/no questions: ‘within the past twelve months, have you used WeChat Pay?’ and ‘within the past twelve months, have you used Alipay?’ If respondents ‘no’ to both of these, their response was coded (0) no, and if respondents answered ‘yes’ to either of these, their response was coded (1) yes. WeChat Pay and Alipay are ubiquitous in China, the most accessible payment systems that have since dominated the entire e-payment systems market (De Best, Citation2021).

The independent variable was highest level of formal education. Responses were coded into five ordinal levels: (0) no education, (1) high school or below, (2) technical college, (3) university, (4) postgraduate or above.

This article further controls for the number of books read in the past twelve months, as a novel measure of informal education. This builds on sociological and economic evidence that reading more books improves individual literacy and active information processing skills that help individuals learn, remember, and apply information – skills that, according to the OECD (Citation2021), are required for meaningful participation in economic life, such as better employment outcomes. This is especially relevant in China, whose rural regions report disproportionately low levels of reading achievement and number of books read (Gao et al., Citation2018).

This study controls for other demographic variables, including age, gender, and total income. Age was recorded as a continuous variable. Gender was recoded into a dichotomous variable: (0) male and (1) female. The total amount of income an individual received for the past twelve months was also recorded as a continuous variable.

Additionally, this study innovates by controlling for the number of social outings. This was based on the CGSS question, ‘over the past year, how often have you gone out to meet up with friends?’ Responses were coded into ordinal levels: (0) never, (1) several times a year or less, (2) several times a month, (3) several times a week, and (4) everyday.

This accounts for evidence linking digital platform use and in-person socializing, but which is mixed on the direction of the relationship. Some evidence suggests that in-person socializing converts to greater digital platform use as friends seek to keep in touch online (Harari et al., Citation2020). Recent studies observe that in-person socializing is inversely proportional to the likelihood of using social media platforms based on simple time use accountancy – the more time spent on one activity, the less time is available for the other (Tuck & Thompson, Citation2021; Twenge et al., Citation2019).

Analytic strategy

To separately examine the predictors of Internet and e-payment system use among variegated types of hukou, the four types of hukou were used to stratify the sample into four subsamples: urban households (n = 2,893), resident households that were previously urban (n = 1,779), resident households that were preciously rural (n = 1,089), and rural households (n = 6,767). This subsample analysis based on types of hukou captured the size of the main effects on each hukou and lent for comparisons between different types.

Binary logistic regressions were conducted on Internet use and e-payment system use for each subsample. While conceptualizing digital technology use as a gradient might be best suited for studying gradations of use, conceptualizing it as binary is better suited for the study of non-use (Reisdorf & Groselj, Citation2017). Given that non-use is an extremity on the scale of use, conceptualizing Internet use and e-payment system use as binary variables tests in a more powerful fashion the willingness to use technology to any degree versus not using it. Within this scope, logistic regressions on binary conceptualizations additionally offer parameter estimates with low bias and high efficiency, and a more straightforward interpretation of the odds of use compared to non-use (Riedl & Geishecker, Citation2014).

There were no missing values for the digital technology use (dependent) variables. For at least one demographic (control) variable, 164 missing cases were identified among urban households, 102 from resident households that were previously urban, 367 from rural households, and 48 from resident households that were previously rural. Missing cases were handled using listwise deletion. The results were the same when multiple imputation was used for handling missing data.

Causal mediation analyses were conducted to assess the mediating influences of educational attainment on the effect of being female on digital technology use. It is well-established, for instance, that women face disproportionately fewer opportunities for upward mobility in China because of patriarchal cultural norms that constrain their place in the household and labor market (Seeberg & Luo, Citation2018). As such, causal mediation analyses assessed the indirect effects that education has on digital skills development (and by extension digital technology use) by alleviating or adding to the effect of gender (Imai et al., Citation2010). Nonparametric bootstrap measures were conducted to estimate significance levels and confidence intervals.

Additionally, thematic content analysis was conducted on responses to the CGSS question, ‘Why don’t you use Internet?’ There were two components to this question. The first was a close-ended question with 14 reasons for respondents to pick, and the second was an open-ended component for respondents to elaborate. Responses congregated around 12 reasons only, reported later ().

The analysis consisted of qualitative coding, the process of taking notes and recording (coding) instances of theoretical interest. For a more parsimonious presentation of results, the close-ended responses were counted and triangulated with the open-ended entries. If open-ended responses were in line with the close-ended options, they were tallied together. Open-ended responses did not materially diverge from close-ended responses, instead explaining in greater detail why they selected ‘age’ as their reason for not using Internet. The recurrent instances of interest were further collated into higher level themes, with which connections were recursively built between the data and theoretical insights about use and non-use on account of digital skills or education (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006).

Results

The proportion of females to males, the mean age, and average participation in in-person social events are relatively comparable across the four types of hukou. However, corroborating Hypothesis 1, a rural-urban divide is observed in the economic and social resources accessible across types of hukou. Across the board, rural hukou citizens report lower income, lower mean levels of educational attainment, and lower number of books read ().

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of covariates by subsample.

Property ownership is comparable, but let this not mask the disparity in economic means across regions. Breaking down recent home purchases by province from the China Statistics Press (Citation2020) and Statista (Zhang, Citation2022), it is observed that property ownership is roughly as common in rural and urban regions because of their property market conditions.

To illustrate, using data from Statista (Textor, Citation2022) the average property price as a proportion of mean wages in affluent Beijing and Guangdong amounts to 3.59 and 6.06, respectively, which are below the national average of 6.15. In the least affluent regions like Ningxia and Guizhou, however, the average property price as a proportion of mean wages is 7.13 and 7.19, respectively, both of which are above the national average. Thus, property ownership is comparable across rural and urban regions only because of lower property prices in rural regions, but which is still tilted unfavorably against the national average when compared with wages.

Despite China’s celebrated digitalization, the high rates of digital penetration recorded () do not reflect active digital technology use and digital integration. It is observed that 7118 individuals used the Internet in the past six months (about 56.8%), but a staggering 5410 individuals did not (about 43.1%). Moreover, 5138 individuals used e-payment systems in the past twelve months (roughly 41.02%), compared to 7390 who did not (roughly 58.98%).

To offer a preliminary account for the wide rift in usage, the matrix in presents a bird’s eye view of digital technology use versus non-use across all four types of hukou.

Table 2. Matrix comparing demographic attributes of digital technology users versus non-users.

The gender proportions are comparable between users and non-users in both Internet and e-payment systems. However, important discrepancies emerge. The mean level of education among users of both types of technology is over twice that of non-users, with the former on average having a high school education or above and the latter having less than a high school education. Similarly, the mean level of hukou among users is 0.8 points (out of 4) more proximal to the coveted urban hukou compared to non-users. The mean age of users is also 20 or more years younger than non-users.

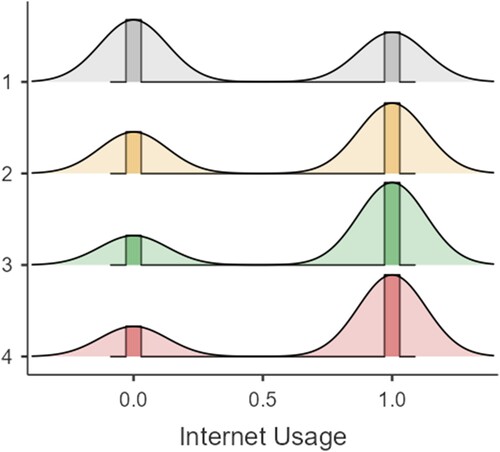

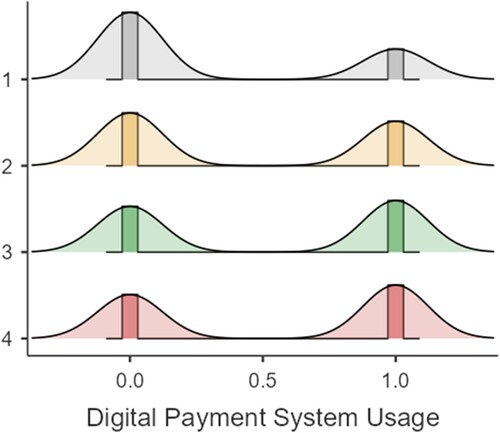

and go further to explore the divide between digital technology use and non-use by hukou. Results further corroborate Hypothesis 1.

Figure 2. Internet use (1 = used, 0 = did not use) parsed out by type of hukou (1 = rural, 2 = resident and previously rural, 3 = resident and previously urban, 4 = urban).

Figure 3. E-payment system use (1 = used, 0 = did not use) parsed out by type of hukou (1 = rural, 2 = resident and previously rural, 3 = resident and previously urban, 4 = urban).

For Internet use, rural hukou is the only one where the number of Internet non-users exceeds the number of users (). For all other types of hukou, most individuals used the Internet, significantly outnumbering non-users.

Turning to e-payment system use, the disparity between rural and urban types of hukou (and their intermediates) grows (). Overwhelmingly, individuals with a rural hukou who have not used e-payments outnumber users by nearly double. Unlike for Internet use, however, this disparity is true even for individuals with a resident hukou who were previously rural, where more individuals did not use e-payments than did.

These preliminary results capture important features about the drivers of use versus non-use that are explored further in the statistical models.

reports the binary logistic regressions on Internet use. Some associations are universal across all four types of hukou. Older age is consistently associated with lower odds of Internet use, consistent with previous research on technology use among older adults (Song & Jiang, Citation2021; Zhou, Citation2019). The effect of income, while significant in most types of hukou, is close to zero. Social outings are associated with higher odds of Internet use, giving credence to theorizations that digital platforms likely functions as a medium to correspond with friends and contacts (Harari et al., Citation2020; Park et al., 2017). The number of books read is non-significant in most hukou, except for rural hukou, where it is associated with slightly higher odds of using Internet, but note that this effect is small in size.

Table 3. Binary logistic regressions predicting Internet use over the past six months across different types of hukou.

Informatively, some effects are different between urban and rural hukou. Being female is associated with higher odds of using Internet, but only among resident hukou that were previously urban (OR = 1.327).

The highest level of educational attainment, moreover, is associated with higher odds of using Internet across all types of hukou, but is significantly stronger in rural hukou. The increased odds of using Internet from educational attainment in rural hukou (OR = 3.89), for instance, is nearly double that of urban hukou (OR = 2.057).

reports the binary logistic regressions on e-payment system use across types of hukou. Some of the covariate effects on Internet use in are consistent. Age is again associated with lower odds of using e-payment systems across all types of hukou. Income is also negligible in predicting e-payment system use. Social events similarly predict greater digital technology use. Books read increases the odds of e-payment system use in both urban and rural hukou, but the effect is again diminutive.

Table 4. Binary logistic regressions predicting e-payment system use over the past twelve months across different types of hukou.

Most salient are the effects of education and being female, corroborating Hypothesis 2. Once again, as in , higher education significantly increases the odds of using e-payment systems, whose effect is the largest and, more importantly, doubly large in rural hukou (OR = 3.385) than in urban hukou (OR = 1.925). Additionally, being female is associated with higher odds of e-payment system use in both urban iterations of the hukou (urban hukou (OR = 1.443) and resident but previously urban hukou (OR = 1.558)), but lower odds in rural hukou (OR = 0.812).

Causal mediation analyses find that the direct and indirect mediating effects of higher education on the association that being female has on both Internet use and e-payment system use among rural hukou ( and ) are significant. It is illuminating that all indirect effects are negative and explain a substantial proportion of the total effect. They suggest that being female has a negative effect on digital technology use in rural hukou, which is indirectly exacerbated by education.

Table 5. Causal mediation analyses on education’s mediating influence on the effects of being female on Internet use among rural hukou.

Table 6. Causal mediation analyses on education’s mediating influence on the effects of being female on e-payment system use among rural hukou.

The same analyses for urban hukou show that the indirect effects significant and negative ( and ). Thus, the obstacle of education as a pathway to lower digital technology use for females holds true for urban hukou also, but we are careful not to overestimate this, as the total (and direct) effects remain significantly positive and/or not significant.

Table 7. Causal mediation analyses on education’s mediating influence on the effects of being female on Internet use among urban hukou.

Table 8. Causal mediation analyses on education’s mediating influence on the effects of being female on e-payment system use among urban hukou.

Consistent with the present theorization of education, women in urban hukou are more liberated from traditional norms that relegate them to household labor and have more opportunities for work and social mobility that, in turn, mean they have more opportunities to learn and use digital technology beyond formal educational settings (Seeberg & Luo, Citation2018).

parses out the reasons that respondents reported for not using the Internet. Together, individuals who responded to this question accounted for 14.22% (n = 1,782) of the total sample (N = 12,528) across all four types of hukou. Roughly 90% of responses are organized around themes about not knowing what the Internet was, in part because of age-related unfamiliarity with technology. Tellingly, those who gave open-ended responses were those who selected age as their reason for not using Internet and expanded on different reasons through which age restricted their ability to do so.

Table 9. Reasons for not using Internet.

According to an 86-year-old respondent, he no longer had opportunities to use or learn about the Internet: ‘when the Internet became popular, I had already retired. The need to learn is gone.’ Age-related physical ailments are another part of the story, according to a 55-year-old respondent who noted, ‘[because I’m older now], my eyesight isn’t very good.’ Most saliently, education – and the generational disparity in education between older versus younger adults – is once again key, the most repeated theme among open-ended responses. Explaining why they did not use Internet, several respondents aged 54–65-years-old reported, ‘I’m illiterate’ and ‘I don’t know how to read.’ As another 61-year-old respondent put it bluntly, ‘I don’t know how to read, and I don’t want to learn.’

Discussion

China is impressive in the sheer rate of digital technology penetration, an oft-cited feature of its trajectory of economic development. A finer examination of usage rates for two cornerstone types of digital technology (Internet and e-payment systems), however, reveals that a sizeable number of individuals have been ‘left behind’ by the winds of digitalization. The number of non-users rivals that of users for Internet use, and even outnumbers users for e-payment system use.

This article builds upon, yet extends previous literature on the rural-urban divide in China by casting light on the present digital technology divide across a nuanced spectrum of four hukou types, capturing rural hukou, urban hukou, and intermediates between the two poles with the newly established resident hukou into which previously rural and previously urban hukou have been siphoned.

The results are telling and consistent with this article’s theorization of education as a crucial source of digital skills training both substantively (teaching students how to use digital technology) and structurally (incorporating digital technology as a medium for instruction). Ultimately, higher levels of educational attainment (greater time spent in the education system and achieving more advanced levels of training) are associated with greater digital technology use across all types of hukou.

The distribution of socioeconomic resources (books read, education, income) and digital technology use are stratified linearly across the hukou gradient from rural (less) to urban (more) hukou (supporting Hypothesis 1). The highest level of educational attainment is also associated with higher odds of Internet use across all types of hukou, but this effect is much stronger in rural hukou, nearly double the effect observed in urban hukou (supporting Hypothesis 2). The reason for education’s outsized effect in rural regions may be linked to the economic and educational deprivation that rural citizens disproportionately face compared to their urban counterparts.

From , the highest level of education in rural hukou is on average high school or lower, whereas that of urban hukou is closer to technical college. Similarly, the mean total income for those living in rural hukou is roughly ¥19,705, whereas those living in urban hukou report over double that amount, ¥51,630.

Thus, for rural hukou citizens, whose socioeconomic resources are lower to begin with, the impact of formal (highest educational attainment) and informal education (number of books read) on Internet use is pronounced because citizens are more dependent on education to learn the requisite digital skills. That is, the impact that education has on rural individuals is more pronounced as a rare source of digital skills training. For other types of hukou that have higher income and access to greater wealth, education is higher by default and so has less of an effect.

Why do women in rural hukou appear less likely to use e-payments technology than those in urban hukou? Causal mediation analyses suggest that one explanation may center on the fact that education is not only a source of digital skills, but also social mobility. Education has significant, negative, and substantial mediating effects that exacerbate that of being female on all forms of digital technology use. This suggests rural households may be more traditional in enforcing cultural norms that relegate women to the household and offer fewer opportunities for women’s education and socioeconomic advancement.

Within rural hukou, education provides an opportunity for women (and men) to directly learn digital skills required of digital technology use, and indirectly opens up greater opportunities to learn such skills by improving chances for upward mobility into higher-status jobs that require information management skills.

Such deprivation is relatively scarcer in urban hukou.Footnote1 This is why being female there does not matter for Internet use and is even associated with higher use of e-payments, even after controlling for education (and why the total mediating effects of education are largely positive and non-significant in urban hukou, compared to rural hukou).

The thematic analyses suggest that Internet non-use is, contrary to previous evidence (Zhou, Citation2019), not due to low interest in the Internet altogether. Rather, triangulated with the statistical results, findings suggest that Internet non-use is due to a dearth of digital skills, largely because of fewer educational opportunities to learn them both formally and informally in early life. This deprivation is age-related (due to cognitive and generational issues) and gender-related (due to patriarchal norms), but whose effects are stratified and contextualized within the broader issue of a stubborn rural-urban divide and the lack of socioeconomic resources available to individuals proximal to rural hukou. This gains credence from the wide margins by which rural hukou lag urban hukou in digital technology use and education ().

Why is there a difference between official numbers of users reported in CINIC and this study’s findings? I suspect the reason is methodological: CINIC likely asked respondents about lifetime use of digital technology (or some other expansive time scale), whereas this study asks about frequency of use within a fixed and recent time frame (within the past six months to a year). Without dismissing the importance of lifetime use, I suggest that constraining our attention to frequency of use within a recent time scale is more telling about who is ‘left behind’ and why. The latter lays bare the socioeconomic circumstances prohibiting the integration of digital tools into everyday life, better allowing us to design acute policy solutions.

The present findings suggest that the adoption of digital technology is unequal and follows conventional fault lines for inequality stratified across urban-rural and female-male divides, mediated by education.

They give urgency to education as a horizon of policy solutions for correcting digital inequality: concentrating resources into developing educational infrastructure and access to education in rural areas.

This study lends credence to subsidy-based policies like the Two Exemption and One Subsidy plan (issued in 2006) that offers free textbooks and subsidies for schoolchildren, but suggests potential to expand them. Possible solutions include pegging subsidies to real (rising) costs of living, designing new affirmative action subsidies targeting female students, and addressing a systemic need to lower tuition costs to make education accessible, an important corrective for the sizeable income lag in rural regions.

Extracurricular digital education programs or opportunities to use digital platforms (such as installing terminals with on-site staff in rural areas to support resident use of e-commerce platforms, as Internet conglomerates have done) could supplement this broad-based push for (gender and regional) equality in education by targeting the digital skills of stakeholders who have aged out of such formal educational opportunities – namely, older adults, who appear most reluctant to use digital technology, but cite as the reason their lack of opportunities to learn.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Anson Au

Anson Au is Assistant Professor of Sociology in the Department of Applied Social Sciences at The Hong Kong Polytechnic University. An economic sociologist and social network scholar, he has published 50 articles in leading journals such as Information, Communication, & Society, Current Sociology, Sociological Review, Critical Asian Studies, Symbolic Interaction, among others.

Notes

1 I say ‘scarcer,’ and not completely ‘non-existent,’because the indirect effects of being female on digital technology use through education still appear to be negative and significant.

References

- Au, A. (2022). Guanxi in an age of digitalization: Toward assortation and value homophily in new tie-formation. The Journal of Chinese Sociology, 9(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40711-021-00160-z

- Bian, Y., & Ikeda, K. (2018). East Asian social networks. In R. Alhajj & J. Rokne (Eds.), Encyclopedia of social network analysis and mining (2nd ed., pp. 1–22). Springer.

- Bian, Y., & Li, L. (2012). The Chinese general social survey (2003-8) sample designs and data evaluation. Chinese Sociological Review, 45(1), 70–97. https://doi.org/10.2753/CSA2162-0555450104

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Castellacci, F., & Viñas-Bardolet, C. (2019). Internet use and job satisfaction. Computers in Human Behavior, 90, 141–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.09.001

- Chan, L. (2021). The politics of dating apps: Gender, sexuality, and emergent publics in urban China. Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press.

- Chen, C., LeGates, R., Zhao, M., & Fang, C. (2018). The changing rural-urban divide in China’s megacities. Cities, 81, 81–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2018.03.017

- China Statistics Press. (2020). 2020 China statistical yearbook. National Bureau of Statistics of China.

- Cotten, S. (2017). Examining the roles of technology in aging and quality of life. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 72(5), 823–826. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbx109

- De Best, R. (2021). Users of Alipay and WeChat Pay in China in 2020, with forecasts to 2025. Statista.

- Denzer, M., Schank, T., & Upward, R. (2021). Does the internet increase the job finding rate? Evidence from a period of expansion in internet use. Information Economics and Policy, 55, Article 100900. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infoecopol.2020.100900

- Dribe, M., & Karlsson, O. (2022). Inequality in early life: Social class differences in childhood mortality in southern Sweden, 1815–1967. The Economic History Review, 75(2), 475–502. https://doi.org/10.1111/ehr.13089

- Gao, G., & Sai, L. (2020). Towards a ‘virtual’ world: Social isolation and struggles during the COVID-19 pandemic as single women living alone. Gender, Work & Organization, 27(5), 754–762. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12468

- Gao, Q., Wang, H., Mo, D., Shi, Y., Kenny, K., & Rozelle, S. (2018). Can reading programs improve reading skills and academic performance in rural China? China Economic Review, 52, 111–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2018.07.001

- Greiffenhagen, C., Li, R., & Llewellyn, N. (2022). The visibility of digital money: A video study of mobile payments using WeChat Pay. Sociology, 57(3), 493–515.

- Gürtzgen, N., Diegmann, A., Pohlan, L., & van den Berg, G. (2021). Do digital information technologies help unemployed job seekers find a job? Evidence from the broadband internet expansion in Germany. European Economic Review, 132, Article 103657. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2021.103657

- Harari, G., Müller, S., Stachl, C., Wang, R., Wang, W., Bühner, M., Rentfrow, P., Campbell, A. T., & Gosling, S. (2020). Sensing sociability: Individual differences in young adults’ conversation, calling, texting, and app use behaviors in daily life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 119(1), 204–228. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000245

- Hargittai, E., & Dobransky, K. (2017). Old dogs, new clicks: Digital inequality in skills and uses among older adults. Canadian Journal of Communication, 42(2), 195–212. https://doi.org/10.22230/cjc.2017v42n2a3176

- Hasan, M., Yajuan, L., & Khan, S. (2022). Promoting China’s inclusive finance through digital financial services. Global Business Review, 23(4), 984–1006. https://doi.org/10.1177/0972150919895348

- Hunsaker, A., & Hargittai, E. (2018). A review of Internet use among older adults. New Media & Society, 20(10), 3937–3954. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444818787348

- Imai, K., Keele, L., & Tingley, D. (2010). A general approach to causal mediation analysis. Psychological Methods, 15(4), 309. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020761

- Jiang, J., & Song, J. (2022). Health consequences of online social capital among middle-aged and older adults in China. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 17, 2277–2297.

- Lewin, C., & McNicol, S. (2015). Supporting the development of 21st century skills through ICT. In T. Brinda, N. Reynolds, R. Romeike, & A. Schwill (Eds.), KEYCIT 2014: Key competencies in informatics and ICT (pp. 98–181). Universitätsverlag Potsdam.

- Li, Y., Tan, J., Wu, B., & Yu, J. (2022). Does digital finance promote entrepreneurship of migrant? Evidence from China. Applied Economics Letters, 29(19), 1829–1832. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504851.2021.1963404

- Olphert, W., & Damodaran, L. (2013). Older people and digital disengagement: A fourth digital divide? Gerontology, 59(6), 564–570. https://doi.org/10.1159/000353630

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2021). OECD skills outlook 2021. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

- Pick, J., Sarkar, A., & Johnson, J. (2015). United States digital divide: State level analysis of spatial clustering and multivariate determinants of ICT utilization. Socio-Economic Planning Sciences, 49, 16–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seps.2014.09.001

- Reisdorf, B., & Groselj, D. (2017). Internet (non-)use types and motivational access: Implications for digital inequalities research. New Media & Society, 19(8), 1157–1176. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444815621539

- Riedl, M., & Geishecker, I. (2014). Keep it simple: Estimation strategies for ordered response models with fixed effects. Journal of Applied Statistics, 41(11), 2358–2374. https://doi.org/10.1080/02664763.2014.909969

- Rui, J., Yu, N., Xu, Q., & Cui, X. (2019). Getting connected while aging: The effects of WeChat network characteristics on the well-being of Chinese mature adults. Chinese Journal of Communication, 12(1), 25–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/17544750.2018.1530270

- Seeberg, V., & Luo, S. (2018). Migrating to the City in North West China: young rural women’s empowerment. Journal of Human Development and Capabilities, 19(3), 289–307. https://doi.org/10.1080/19452829.2018.1430752

- Song, J., & Jiang, J. (2021). Online social capital, offline social capital and health: Evidence from China. Health & Social Care in the Community 30(4), e1025–e1036.

- Song, Q., & Smith, J. (2019). Hukou system, mechanisms, and health stratification across the life course in rural and urban China. Health & Place, 58, 102150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2019.102150

- Song, Q., & Smith, J. (2021). The citizenship advantage in psychological well-being: An examination of the Hukou system in China. Demography, 58(1), 165–189. https://doi.org/10.1215/00703370-8913024

- Textor, C. (2022). Monthly minimum wage in China as of January 2022, by region. Statista.

- Tonoyan, V., Strohmeyer, R., & Jennings, J. E. (2020). Gender gaps in perceived start-up ease: Implications of sex-based labor market segregation for entrepreneurship across 22 European countries. Administrative Science Quarterly, 65(1), 181–225. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001839219835867

- Tuck, A., & Thompson, R. (2021). Social networking site use during the COVID-19 pandemic and its associations with social and emotional well-being in college students: Survey study. JMIR Formative Research, 5(9), Article e26513. https://doi.org/10.2196/26513

- Twenge, J., Spitzberg, B., & Campbell, W. (2019). Less in-person social interaction with peers among U.S. adolescents in the 21st century and links to loneliness. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 36(6), 1892–1913. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407519836170

- van Laar, E., van Deursen, A., van Dijk, J., & de Haan, J. (2020). Determinants of 21st-century skills and 21st-century digital skills for workers: A systematic literature review. Sage Open, 10(1), Article 2158244019900176. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244019900176

- Wang, H., & Cheng, Z. (2021). Mama loves you: The gender wage gap and expenditure on children’s education in China. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 188, 1015–1034. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2021.06.031

- Wang, J., Tigelaar, D., & Admiraal, W. (2021). Rural teachers’ sharing of digital educational resources: From motivation to behavior. Computers & Education, 161, Article 104055.

- Williams, R. (2022). Social Networking Services (SNS) in education. Asian Journal of Advanced Research and Reports, 17(1), 1–4.

- Wu, Y., & Qi, D. (2017). A gender-based analysis of multidimensional poverty in China. Asian Journal of Women’s Studies, 23(1), 66–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/12259276.2017.1279886

- Yin, Z., Gong, X., Guo, P., & Wu, T. (2019). What drives entrepreneurship in digital economy? Evidence from China. Economic Modelling, 82, 66–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2019.09.026

- Zhang, J., Wang, R., & Lu, C. (2019). A quantitative analysis of Hukou reform in Chinese cities: 2000–2016. Growth and Change, 50(1), 201–221. https://doi.org/10.1111/grow.12284

- Zhang, W. (2022). Average sale price of residential real estate in China in 2020, by region. Statista.

- Zhong, S., Wang, M., Zhu, Y., Chen, Z., & Huang, X. (2022). Urban expansion and the urban–rural income gap: Empirical evidence from China. Cities, 129, Article 103831.

- Zhou, J. (2019). Let us meet online! Examining the factors influencing older Chinese’s social networking site use. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 34(1), 35–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10823-019-09365-9