ABSTRACT

This study investigates social media usage patterns, Twitter’ frequency use and message typologies of selected South African female politicians’. Using the digital public sphere theory as a lens, the study considers six hundred Twitter posts from six female politicians from the African National Congress, Democratic Alliance, and Economic Freedom Fighters political parties to examine the potential of social media for visibility and participation, particularly for female politicians who are underrepresented in mainstream media platforms. The study finds that these politicians leverage digital media to promote their public works, challenging media gatekeeping and asserting agency in shaping public discourse. The findings also reveal the strategic use of social media for self-promotion allowing female politicians to enhance visibility, influence public perception, and consolidate their positions.

Background and literature review

Digital media affordances have led to the reconfiguration of engagement methods – from business and trade to entertainment and political life. As Wigand (Citation2010, p. 563) posits, ‘these social media designed originally for friends to connect with friends are changing as private, public and non-profit sector organizations join these online communities to engage their targeted stakeholders.’ Recognising this shift, scholars have examined the implications of this growth in social media on how politicians engage with citizens. Kruikemeier et al. (Citation2018, p. 218) examine how visibility has become central to political communication conversations in contemporary studies and argue that ‘politicians’ visibility depends on the number of people who actively mention them, talk about them online, or share posts about them’. Commenting on this, Waters and Williams (Citation2011, p. 353) intimate that ‘characterized by the distribution of user-generated content, Web 2.0 applications are increasingly being used to relay political-campaigning messages and maintaining relationships with constituents while serving office.’ Manning et al. further consider how politicians in many established democracies frequently try to present themselves as accessible, relatable and authentic individuals through social media (Manning et al., Citation2017). Some scholars have explored the extent to which social media has presented women with fairer opportunities to enter political life (Yarchi & Samuel-Azran, Citation2018; Mutsvairo, Citation2016; Basow, Citation2016; Joiner et al., Citation2016). It is these opportunities that Sobaci and Karkin (Citation2013, p. 417) to conclude that ‘today, the use of ICTs by elected officials has become all the more important because of the potential of ICT-based innovative tools to transform the relationship between the elected and citizens.’

As digital technologies continue to advance and permeate various aspects of society, researchers have turned their attention to the transformative power of social media in political contexts. This scholarship, however, is skewed towards developments in the global North with little focused on the global South. For example, Skalli (Citation2014) discusses anti-sexual harassment initiatives launched in North Africa within the broader context of the Arab Spring. Gheytanchi and Moghadam (Citation2014) explore the diffusion of the use of new media technologies by women through the internal and external communicative practices of social movements and the effects on women’s roles as collective agents of social change. Mateveke and Rosemary Chikafa-Chipiro’s (Citation2020) study looks the misogyny that accompanied the treatment of and responses to the female electorate in Zimbabwe’s 2018 elections. Ncube and Yemurai (Citation2020) examined the discrimination of female politicians in the Zimbabwean digital public sphere. Glenwright (Citation2011) looked at ways social media empowers women and other disadvantaged groups, analysing its use as a conduit for spreading essential human rights messaging. Mano and Ndlela’s (Citation2020) edited volume explored different African cases where social media has been used for politicking and electioneering. Mare and Matsilele (Citation2020) studied the relationship between social media and elections in Zimbabwe’s 2018 polls. Oxlund (Citation2016) studied what he described as the new form of student protest, which traced its genealogy on social media.

The above corpus show Africa’s rapidly evolving digital landscape. However, it is essential to note that few studies have specifically explored the role of women politicians concerning social media use and politics, both within Africa and globally. While some studies examine the relationship between female politicians and social media use for public engagement (Beltran et al., Citation2021; McGregor et al., Citation2017; Yarchi & Samuel-Azran, Citation2018), these have been concentrated in the global North and with a few having looked at sub-Saharan Africa (Ncube & Yemurai, Citation2020). A preliminary investigation of online portals shows a lack of scholarship on how and for what purposes African female politicians are appropriating social media. This observation is a sharp departure from the global North, where consideration has been given to the issue (Fuchs & Schäfe, Citation2021; Yarchi & Samuel-Azran, Citation2018).

This research gap calls for a focused examination of how female politicians utilise social media for communication, engagement, and agency within the African political context. Social media platforms have the potential to provide an avenue for women politicians to amplify their voices, overcome gender biases, and challenge the existing power structures within political spheres. Furthermore, studying how women politicians navigate and utilise social media offers insights into the potential of these platforms to foster greater inclusivity and gender equality in political participation. This exploratory study speaks to the dearth of scholarship investigating female politicians’ use of social media and understanding the patterns and typologies of their shared messages. This study is also essential considering earlier findings by Gelber (Citation2011, p. 2), who concludes that ‘social media may play to women’s preferred styles of communication.’

Studies on social media use in South Africa have confirmed that women have 55% more posts on social media than men (Vermeren, Citation2015). Still, such studies do not tell us much about female politicians’ use of social media in political communication. Research in other parts of the world has confirmed that female politicians engage more on social media than their male counterparts (Beltran et al., Citation2021). This study explores the patterns in use, message typologies and for what purposes female politicians appropriate social media. By examining their strategies, as evidenced in what they tweet, we can gain valuable insights into the transformative role of social media in reshaping gender dynamics, fostering women’s agency, and promoting more diverse and representative political discourse in contexts in the global South.

This study seeks to contribute toward filling the gap on how female politicians in Africa deploy social media for political purposes. In this study, we focus on South Africa, one of the few advanced democracies in the region, by examining female politicians’ use of Twitter in this context as a case study of how female politicians from the global South use social media for political communication. South Africa is outperforming its regional peers on social media uptake. It has 38.2 million internet users (about 64% of the population). This number grew yearly by 1.7 million users, while active social media users increased from 22 million in January 2020 to 25 million in January 2021. Around two of every five South Africans use social media (Lord, Citation2021). This growth in social media uptake in this context has impacted how politicians engage with citizens. Unlike in the days when political actors relied on mainstream media for public engagement, social media allows access to audiences without the normative roadblocks that come with mainstream media. This reconfiguration means female politicians can increase access and visibility, even with limited budgets.

Theoretical framework: the digital public sphere

The study uses the digital public sphere drawing on Habermas’ (Citation1989) public sphere concept.

The digital public sphere theory stems from this conception of the public sphere as a ‘forum where people meet and discuss issues of the day.’ However, such a sphere is no longer a coffee shop but rather is refracted by the virtual sociality of social media, by application software, server farms, the ‘cloud,’ the battery life of smartphones, emojis, and the proprietary terms of use of Twitter, Facebook and WhatsApp (Matsilele, Citation2019; Sharra & Matsilele, Citation2021). The use of digital technology for communication and social mobilisation has brought into question the public sphere created by traditional media platforms and enabled citizens, particularly those who were excluded from participation in conventional media, to exert influence and challenge the ‘discursive hegemony of the centres of power’ vested in mainstream communication channels (Sampedro & Avidad, Citation2018, p. 22). The digital public sphere differs, and even challenges the Harbamasean notion of the public sphere through its potential to create subaltern counter publics that use the alternative space provided by digital tools, to questions the official consensus that is often established in mainstream discourse (Castells, Citation2008). Furthermore, subordinated groups, such as women, can use the affordances it provides as public opinion leaders.

Thus, when used in this study, it is not merely as a concept that replicates Habermas’s notion in the digital space: it is as an alternative space (Etling et al., Citation2014) used by counter elites, such as women, for self-communication in communicative contexts that they have traditionally been excluded from, such as the political arena (Castells, Citation2008). As Etling et al. (Citation2014) argued, an alternative public sphere is a space for public discourse with an agenda that differs in scope and emphasis from official government media and traditional media outlets subject to government controls. Twitter has provided space for people often ‘denied’ in mainstream state-controlled media. This article extends the concept as an alternative public sphere, drawing from the alterations of digital media and other democratic evolutions of society since this imagination of the public sphere. Studies (Beltran et al., Citation2021; Rheault et al., Citation2019) have confirmed that female politicians tend to be met with uncivil messages and gender stereotypes on social media than their male counterparts. This view finds expression in the work of Beltran et al. (Citation2021, p. 239), which assert that ‘politicians conform to gender stereotypes online and reveal ways in which citizens treat politicians differently depending on their gender.’ Scholars repeatedly find that even at the highest levels of political participation (Haraldsson & Wängnerud, Citation2019), such as in the role of president and party leaders, women’s political communication endeavours are still distorted and often under-reported in mainstream media, the communicative channels presented by digital media, are well placed in allow them to self-communicate. In this study, we are interested in understanding how female politicians use social media even as they face gender stereotypes in the social media sphere.

One of the criticisms of the digital public sphere is that it is not even strictly ‘public’ because they are privately owned, and the public can be locked out or banned from the app by corporate owners or other users. Furthermore, assumptions that social media are accessible to the public remain illusory because companies that own such platforms constantly collect users’ data to sell or use to learn more about users’ habits (Isaak & Hanna, Citation2018). Social media platforms have also been branded as ‘elite’ spaces as people who participate in them require smartphones, data that facilitate connectivity and must be conversant in English in most cases.

Methodology

This multi-case study considers the tweets of selected South African politicians to consider the typology and frequency of their social media use for political communication. In considering the typology, the study sets out to categorise the type of content these politicians post, namely original tweets, retweets and replies, to posit the nature of their participation in the digital public sphere. The typology will also consider what they post about to theorise on the genre of their political messages in online spaces. Finally, the analysis of the frequency examines the levels of their engagement in the digital public sphere.

The profiles of politicians considered in this study as per their Twitter accounts on April 2022 were as follows:

Lindiwe Sisulu, a government minister and a member of the governing African National Congress’s (ANC) National Executive Council (@LindiweSisuluSA) – 252.7 K followers [Joined in 2017]

Khumbudzo Ntshavheni, a government minister and member of the governing ANC (@Khu_Ntshavheni) – 13.6 K followers [Joined in 2012]

Helen Zille, chairperson of the official opposition party, the Democratic Alliance’s (DA) Federal Council (@helenzille) – 1.4M followers [Joined in 2009]

Mpho Phalatse, was the Executive Mayor of Johannesburg and a member of the DA during the study period (@mphophalatse1) – 38.9 K followers [Joined in 2016]

Naledi Chirwa, a member of parliament who serves on behalf of the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) (@NalediChirwa) – 123.9 K followers [Joined in 2011]

Hlengiwe Mkhaliphi, a member of parliament and the deputy secretary-general of the EFF (@HhMkhaliphi) – 31.5 K followers [Joined in 2013]

These political figures were selected because they represent the three biggest political parties in South Africa. Also, they were chosen because our preliminary study showed that they were among the most active Twitter users from their respective political formations. Thirdly, all of them are senior leaders in their political parties. Finally, they have thousands of followers, with Helen Zille having over a million. The decision to sample only two politicians per party does pose a limitation, as there may have been several other profiles to consider. In deciding to examine the Twitter activity of these six women, we were drawn to profiles that were active and engaged on Twitter at the time, profiles that belonged to people who are considered leaders within their parties, as well as who occupy a public leadership role, such as that of a minister, member of parliament or mayor, and those with a considerable following. Zille is the outlier in this respect, as she does not occupy these roles. She was selected, however, because she is the party’s federal chairperson, and further, at the time, there were not many female DA MPs active on Twitter. A similar consideration was made when selecting Sisulu and Ntshavheni. Of the female ANC MPs, their activity and following on Twitter were deemed to be of a level that would allow one to observe patterns in usage of the platform. While these politicians are on other social media sites, such as Facebook and Instagram, we chose to focus on Twitter because it is the primary public-facing platform that scholars say is most expedient for political communication (Murthy, Citation2018).

One hundred tweets from each politician were downloaded using a Twitter scraper. The scraper was programmed and requested to pull the posts from 30 April 2022. Because of the differences in the frequency with which each of these politicians tweeted, for some, the 100 tweets covered only seven days, while for others, the 100 tweets were over a month. The decision to collect the data based on a fixed number of tweets per politician rather than a fixed period for all of them is because some tweet more frequently than others, which could skew the analysis of the typology of the tweets. Once the data was collected, the content analysis was undertaken using different applications to generate graphical representations that would then allow us to consider the extent of engagement of each of the politicians on Twitter as a digital public sphere, categorise the nature of the tweets, and then theorise on the genre to ascertain how they use this social media site for political communication.

Results and discussion

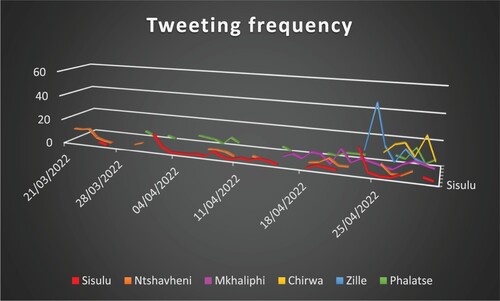

above is a graphical representation of when each politician posted their 100 tweets. Sisulu, Ntshavheni and Phalatse’s tweeted fewer tweets per day but more consistently over time, whereas Zille and Chirwa tweeted more tweets per day but were less consistent in their engagement. Zille, for example, tweeted 47 times on 24 April 2022, compared to 10 times the day before that and 15 times the day after. One explanation for Sisulu, Ntshavheni and Phalatse’s tweeting patterns could be that as government employees, with Sisulu and Ntshevheni being ministers in the national government and Phalatse being a mayor at the local government level, the frequency of their tweeting is driven by a need to be seen to be proactively engaged in the digital public sphere, communicating about the programmes and issues about the portfolios they oversee. And indeed, when we examine , and below, which are a graphical representation of the contents of their tweets further on, we see that this is the case. Zille and Chirwa, on the other hand, engage on party political issues, as depictured in and below, and so their political communication ends are not primarily about providing relevant information in the digital public sphere but about deliberating on matters pertinent to their political party priorities ().

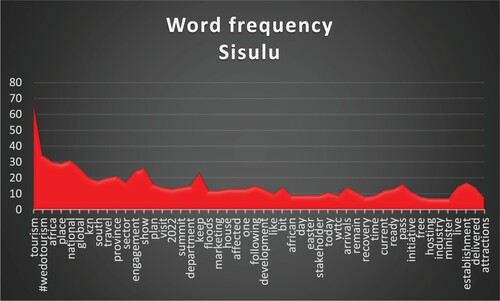

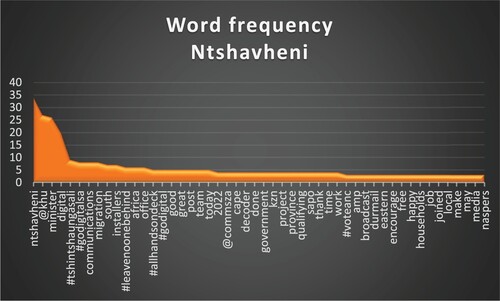

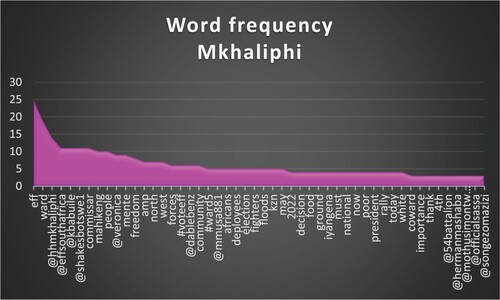

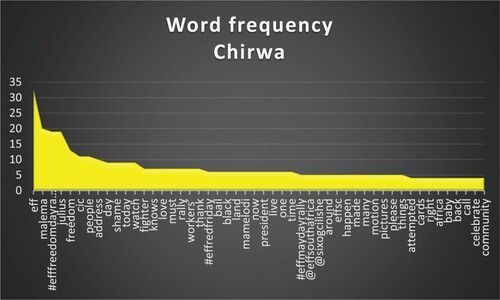

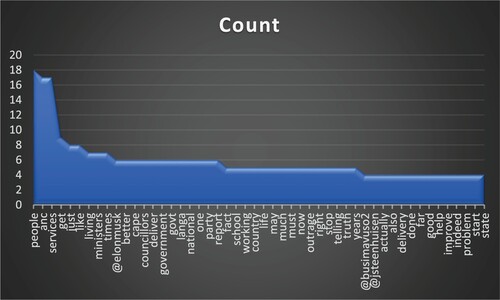

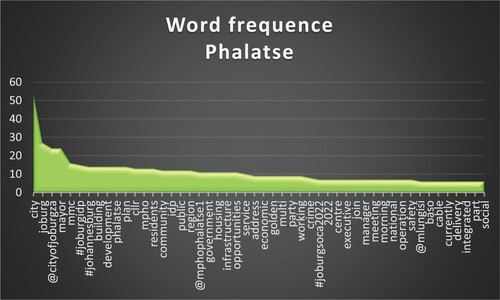

above were created based on word frequency tables generated by an application called Wordsmith, which tallies the number of words used in a corpus of data, in this case, the tweets of each of the politicians considered. shows that the five most frequently used words in Sisulu’s tweets are related to her portfolio as the national minister of tourism. In , we see that for Ntshavheni, a similar pattern is observed, with her most frequent words being about communications and digital technologies. shows that the words most frequently used in Mkhaliphi’s tweets relate to her political party, the EFF, and, similarly, for Chirwa in . The graphical representation of Zille’s tweets, namely , shows us that many of her tweets were devoted to the governing ANC, the government, government ministers and service delivery. , a graph based on the most frequently used words in Phalatse’s tweets, shows us that most of what she focused on related to her work as the Johannesburg mayor. A close reading of the tweets enabled us to further categorise the contents and the nature of the political communication engagement they aim to articulate in the digital public sphere.

Analyzing the politicians’ tweeting patterns and content provides valuable insights into their engagement within the digital public sphere, a concept grounded in theories of participatory democracy and mediated public discourse (Etling et al., Citation2014). reveals distinct temporal patterns in the politicians’ tweeting behaviours, reflecting their navigation of the digital landscape and their efforts to participate in public dialogue actively. Sisulu, Ntshavheni, and Phalatse demonstrate a consistent and sustained presence on Twitter, aligning with a deliberative public sphere, where public officials engage in ongoing, substantive discussions with citizens and stakeholders (Evan, Citation2012). On the other hand, Zille and Chirwa demonstrated higher daily tweet volumes but with less consistency in their engagement. Their focus appeared to align more with party political issues rather than providing relevant information in the digital public sphere. and depict their engagement on matters pertinent to their respective political party priorities. This observation underscores the influence of partisan considerations on their political communication ends within the digital public sphere.

Furthermore, the findings shed light on female politicians’ discursive practices in the digital public sphere. provide further insights into the content of the politicians’ tweets. The word frequency analysis reveals distinct patterns aligned with their roles, portfolios, and political affiliations. Sisulu and Ntshavheni predominantly tweeted about their respective portfolios as ministers in the national government, while Phalatse focused on her work as the Johannesburg mayor. Mkhaliphi’s tweets were highly associated with her political party, the EFF, while Zille’s tweets frequently revolved around the governing ANC, government, government ministers, and service delivery. These findings indicate the varied nature of the political communication engagement undertaken by the politicians within the digital public sphere.

The use of social media for public engagement has been on the rise globally. For example, a study by Ornico and World Wide Worx (Citation2021) concluded that social media use was the preferred method of communication in South Africa due to affordability and access. An interesting finding from the same study titled Social Media Landscape 2021 is that ‘there has been a 59% increase in respondents saying that social media is an effective public relations channel and 123% increase in respondents saying that it lowers the cost of communication’ (World Wide Worx, Citation2021, p. 6). We argue that this explains, in part, the uptake of social media as a communicative device by both party and public officials. As indicated above, politicians in government, regardless of party affiliation, use social media for government purposes compared to partisan actors outside of government. This was the case with Sisulu, Ntshavheni and Phalatse, who tweeted fewer tweets per day but more consistently over time. In contrast, Zille and Chirwa tweeted more, daily, but were less consistent in their engagement. Zille, for example, tweeted 47 times on 24 April 2022, compared to 10 times the day before that and 15 times the day after.

We now turn our attention to a more in-depth analysis of the tweets to examine the nature of the messages, namely whether they are original tweets or retweets, replies, as well the contexts of the tweets, namely what is said and what images or other media are linked into the body of the tweets. New media, including Twitter, offer politicians an unprecedented opportunity to communicate directly with large numbers of citizens. Building on earlier works by Beltran et al. (Citation2021, p. 240), we equally ask, when politicians have full control over the messages they send to the public, do they communicate in ways that conform to gender stereotypes? For this study, we sought to understand the typologies of social media messaging by female politicians from South Africa’s three biggest political parties. We categorised these into informational and trust-building mechanisms, partisan messaging and metavoicing.

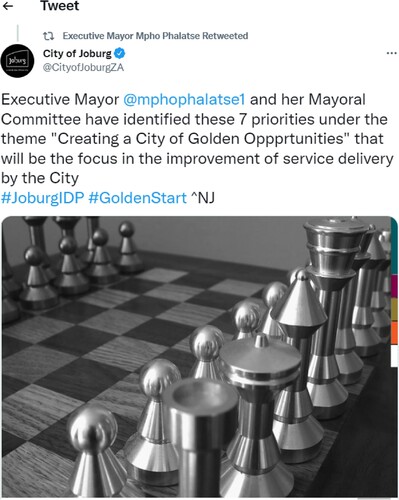

Firstly, some tweets serve as information-sharing about their work as civil servants. These tweets provide information, as shown in and below. They are prone to be retweets of tweets issued from a government entity’s Twitter account, as opposed to tweets issued directly by the political principal herself. This phenomenon reflects the interplay between political agency, organisational communication, and the digital public sphere.

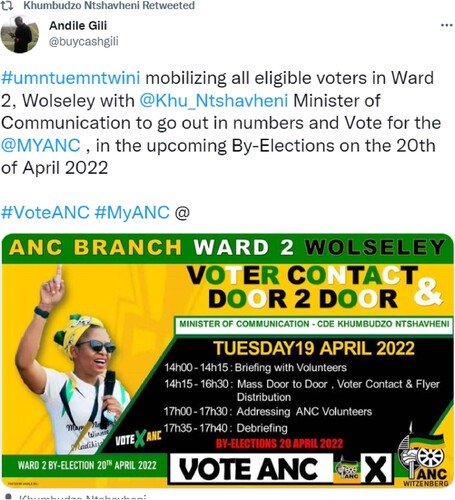

Secondly, some tweets serve as information-sharing about the activities of their political party, as shown in and . These tweets are characterised by their alignment with partisan priorities, manifesting in discussions, announcements, and commentary related to party events, policy stances, and ideological debates. The presence of such tweets underscores the politicians’ dual role as party representatives and social media users within the digital public sphere. By utilising their personal Twitter accounts to disseminate party-centric information, the politicians reinforce their commitment to advancing party agendas, rallying support, and engaging with party supporters and followers.

These tweets were also retweeted from other accounts, as opposed to original tweets from the female politicians.

The retweeting behaviour observed among the politicians aligns with institutional amplification, a process wherein individuals leverage social media platforms to amplify official messages and enhance their visibility and credibility (Kreiss, Citation2015). By strategically sharing content from government entities, the politicians demonstrate their alignment with official narratives, positioning themselves as reliable sources of information and reinforcing their role as civil servants entrusted with communicating government policies and initiatives. This phenomenon highlights the complex interconnections between political actors, bureaucratic structures, and digital communication within the realm of public administration. Furthermore, the prevalence of retweets from government accounts suggests the existence of a broader communication ecosystem within which the politicians operate. This ecosystem encompasses a network of government agencies, departments, and affiliated entities that actively utilise social media to disseminate official information(Grawe et al., Citation2023). The retweeting behaviour by the politicians can be seen as an intentional effort to leverage this established communication infrastructure, amplifying the reach and impact of government messaging through their digital platforms. This phenomenon underscores the interplay between individual political agency, organisational messaging strategies, and the interconnectedness of actors within the digital public sphere.

By engaging in retweeting practices of government content, Sisulu and Ntshavheni navigate the dual roles of civil servants and social media users, strategically shaping their online presence and leveraging institutional resources to maximise their impact within the digital public sphere. This dynamic highlights the multidimensionality of political communication in the digital age, wherein individual agency, organisational structures, and information flows intertwine to shape the discourse and dissemination of information within the political landscape. Understanding these complexities provides valuable insights into the evolving nature of digital politics and the intricate interactions between political actors and institutional frameworks within South African governance.

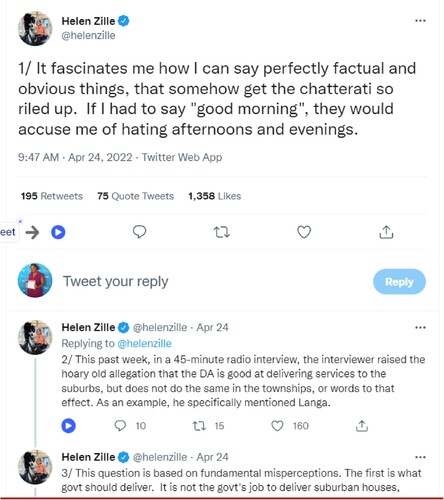

The third category of tweets was those that critiqued another political party. In this instance, the DA and EFF politicians critiqued the ANC, as shown in , and below.

is a retweet by Helen Zille of a tweet from a news media Twitter account about a DA member parliament exposing wrongdoing by government ministers affiliated with the ANC. This retweet illustrates Zille’s strategic use of social media to amplify critical news coverage that aligns with her party’s narrative and bolsters the Democratic Alliance’s (DA) position as an opposition party. By disseminating this content, Zille leverages the credibility and reach of the news media outlet, contributing to a broader discourse surrounding the ANC’s governance and potentially influencing public perception.

is a reply tweet from Zille to someone who replied to an original tweet she posted. The reply simultaneously praises the work being done by her party, the DA, while criticising the ANC. It exemplifies Zille’s adeptness at combining praise for her party, the DA, with criticism directed towards the ANC. Such communication tactics allow Zille to reinforce the party’s image, project a sense of competency and contrast it with perceived failures of the ANC. These examples underscore Zille’s strategic deployment of social media to advance partisan narratives, engage in political discourse, and shape public opinion within the dynamic landscape of digital political communication.

Another example of how these female politicians use Twitter to critique other political parties is when they tweet a tweet portraying another party negatively and then attach their own commentary to this, as exhibited by Mkhaliphi’s quote tweet in below. By quote tweeting, these politicians effectively insert their voices into ongoing political conversations, leveraging existing content to express their party’s perspective and advance their own political agendas. This tactic allows them to actively shape the narrative surrounding political opponents and foster engagement among their followers and supporters. Using Twitter as a medium for critique and commentary, these female politicians harness the platform’s interactive nature to amplify their party’s message, heighten political discourse, and potentially influence public perception and political debates within the digital sphere.

above show that these female politicians engage on Twitter primarily through retweeting content that either supports their political party by providing information about their work or critiques another party. Occasionally they engage through replies to their followers or quote tweets. There were very few tweets issued by these female politicians where, without retweeting or quoting another account, they made an explicit political statement to generate a deliberation on a matter. An example of this was a Twitter thread of 18 tweets and several replies by Zille where she was talking about service delivery issues, as depicted in .

These trends show that in their engagement on Twitter as a digital public sphere, these female politicians rely heavily on content generated by others to articulate their political perspectives rather than on crafting their own tweets. This strategic use of retweets allows them to leverage existing information and narratives to reinforce their party’s position and engage their followers within the digital public sphere. Additionally, occasional engagements through replies to followers and quote tweets further enhance their participation in political discourse. However, a notable finding is the limited occurrence of explicit political statements made directly by these politicians without the use of retweets or quotes. This observation highlights the importance of studying digital deliberation, a concept rooted in the theories of deliberative democracy and participatory politics. It reveals a potential gap in these female politicians’ explicit generation of deliberative discussions on Twitter. Nonetheless, it is worth noting that exceptions do exist, such as Zille’s Twitter thread in , where she initiates a sustained discussion on service delivery issues. This example demonstrates the potential for these politicians to engage in direct political statements that facilitate deliberation and extend beyond amplification or critique, promoting deeper dialogue within the digital public sphere.

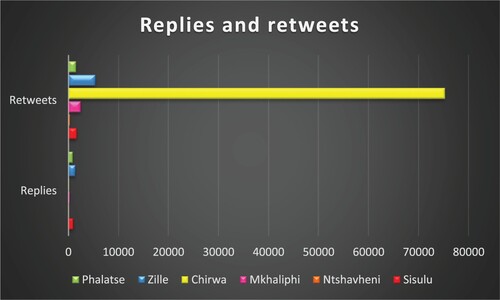

The final figure below is a graphical representation of how the followers of these female politicians engage with their tweets in the form of retweets and replies, as depicted in . Firstly, we observe that Chirwa’s tweets solicited a huge number of retweets. This was a tweet from another account that gained much traction and ended up going viral with over 20,000 retweets. Thus, this number has very little to do with Chirwa and is an outlier. When this is removed, we observe that the preferred means of engagement on the part of the followers of these female politicians is through retweets of what they have shared. Zille did have many replies based on the April 24th thread discussed above. However, other than that, the replies are not particularly notable, given that these women have tens of thousands of followers.

The analysis of offers two key insights regarding the engagement patterns of followers of these female politicians on Twitter, which can be examined through the lens of participatory culture and networked publics (Jenkins & Ito, Citation2015). Firstly, the substantial number of retweets received by Chirwa’s tweets, particularly the viral outlier, highlights the participatory nature of social media platforms, where individuals actively participate by amplifying and circulating content they find relevant or noteworthy. This phenomenon aligns with the concept of participatory culture, emphasising the democratic potential of social media as a space for users to disseminate political information (Jenkins & Ito, Citation2015). Secondly, the limited prominence of notable replies from followers suggests a need for further exploration of networked publics and audience dynamics within the digital public sphere (Bruns & Highfield, Citation2015). Understanding the factors influencing follower behaviour and interactive discourse can provide valuable insights into the mechanisms driving engagement and participation, facilitating a deeper understanding of the complexities of online political conversations.

Typologies

Informational and trust-building mechanism

A study by Odeyemi and Abati (Citation2021, p. 358) argues that ‘technologies can help parliaments become “more sensitive to the needs to engage with the public”, thus promoting “more open and outward-facing practices towards addressing the burgeoning “crises of trust”" in public institutions,’ and indeed, out study found a discernible social media pattern among female politicians who are in government. The graphical presentation shows that Sisulu, Ntshavheni and Phalatse’s tweeted most about their government work. Trust-building and ensuring improved public participation are in sync with what Govender (Citation2020) established in her seminal work that looked at social media use for public engagement by South Africa’s parliament. Our findings also established that the frequency of their tweeting is driven by a need to be seen to be proactively engaged in the digital public sphere, communicating about the programmes and issues pertaining to the portfolios they oversee. This view is consistent with Lee and Kwak (Citation2012, p. 492), who intimated that ‘social media has opened up unprecedented new possibilities of engaging the public in government work.’ This study confirms other studies, such as Alam and Lucas’s (Citation2011, p. 1000), which concluded that ‘government agencies are using tweets mostly to disseminate or broadcast news and updates about their agency or external agency information and events.’ Social media usage has been challenged by some theorists arguing that by solely broadcasting messages in a similar fashion to the mainstream media, social media has failed to facilitate a digital public sphere where views are exchanged before consensus can be formed and prevailing opinions challenged.

Partisan messaging

We observed a closer synergy between claims above and social media appropriation by non-government partisan actors. As this study found out, Zille (DA) and Chirwa (EFF) engage on party political issues, as depictured in and . Their operations, being non-government officials, give them leverage to dabble in messaging devoid of any editorial responsibility and normative media ethics. An example of partisan messaging, in this case undermining the ANC, shows Zille () subtly juxtaposing dirt with voting for the governing party. While subtle, Zille’s conflation of dumping ground in the wrong place is weaved together with other unfortunate scenarios, such as voting ANC.

Crilley and Gillespie (Citation2019, pp. 174–175) postulate the challenges posed by social media regarding polarisation and partisanship, arguing that:

Political actors no longer need journalists to get their message out, they can simply produce media content and circulate it to large audiences themselves. Not only does this lead to political messaging being devoid of any editorial responsibility according to agreed professional ethics, it serves to spread misinformation that in turn contributes to sexism, racism, xenophobia and an undermining of trust in the media.

Metavoicing

The Twitter posts by these South African female politicians demonstrate their active engagement in the digital public sphere, utilising social media to promote themselves and their works publically and advance their political agendas. By leveraging these platforms, these politicians showcase their agency and challenge the limitations imposed by traditional media structures. They can bypass gatekeepers, reach a wider audience, and actively participate in shaping public discourse. Moreover, the findings highlight the concept of metavoicing, a trust-building mechanism adopted by female politicians on social media. Metavoicing on social media relates to ‘adding opinions in the form of expressing likes, comments, and ratings for the original content of others’ (Liu-Thompkins et al., Citation2020, p. 395). This process generates extensive qualitative data as responses often take the form of a discussion (Waxa & Gwaka, Citation2021, p. 449). This study found that, often, female politicians liked and retweeted messages shared by other users. As this study’s findings show, much of the metavoicing happens in party-related ( and ) activities in the form of retweets or shaming the other party ().

As Kaylor (Citation2019) observes, a key part of today’s polarised society is driven by the polarised and polarising world of social media. The scholar adds,

already-existing polarisation in society leads to a polarised use of social media as individuals seek like-minded online communities. However, social media adds to that polarisation by providing echo chambers, and social media features encourage speed over accuracy and more aggressive communication. (Kaylor, Citation2019, p. 183)

Metavoicing allows these politicians to shield themselves from uncivil messages and harassment in the cybersphere, enabling them to maintain their agency and continue their political work without undue interference. Overall, the analysis of the Twitter screenshots reveals how female politicians in South Africa utilise social media to navigate the public sphere, exercise agency, and overcome the barriers imposed by mainstream media, ultimately contributing to a more inclusive and participatory political landscape.

Conclusion

Representing women in the domain of politics is not simply a question of ‘political equality but also relevant to the general pursuit of a more egalitarian society’ (Ncube & Yemurai, Citation2020). While introducing social media has allowed subaltern groups to move from the margins to the centre of public discourse, the change has not been revolutionary. Our study shows that female politicians still rely on metavoicing to communicate with their constituencies instead of constructing their tweets. The study also shows that female politicians, especially those in government, are using the digital public sphere in the same way they deployed traditional media, such as broadcasting information about government programmes of action or information regarding government works. The overarching observation from this study is that female voices are still ‘missing’ as they prefer to employ metavoicing to communicate their messages. Ultimately, this study endorses the postulations of Franks (Citation2021, p. 132), who argued that

if we want online spaces that do not merely replicate existing hierarchies and reinforce radically unequal distributions of social, economic, cultural, and political power, we must move beyond the simplistic and corrosive cliché of the unregulated public square and commit to the hard work of designing for democracy.

This challenges the traditional media’s control over political narratives and empowers female politicians to assert their agency in shaping public opinion. Thirdly, while our study finds that female politicians appropriate social media more for their public works rather than self-promotion, it is crucial to recognise that self-promotion can also be a form of agency. By actively promoting their achievements and initiatives, female politicians assert their presence, build credibility, and influence public perception. Their ability to strategically present themselves in the digital public sphere demonstrates agency in shaping their public image and political agenda. Finally, we can connect the use of metavoicing with trust-building endeavours. In the tweets considered, we observe the reliance of female politicians on metavoicing, which serves as a trust-building mechanism to shield them from uncivil messages and harassment in the cyber sphere. This demonstrates the agency of female politicians in navigating online spaces and protecting their voices from negative and hostile interactions. Metavoicing enables them to maintain their agency and continue engaging in political discourse without being silenced or deterred by online negativity.

For future studies, we recommend more investigations to understand the alignment between what politicians tweet online with their party’s political positions. We also recommend a comparative approach examining how party politics and country-specific political dynamics influence how women politicians use social media for political communication. We also recommend using other data collection methods, such as interviews, to consider the motivations of female politicians who use Twitter for communication and why those not in government use the platform to engage on their party policies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Trust Matsilele

Trust Matsilele is a senior Journalism Lecturer at the Birmingham City University's School of Media and English. He has published two books, Social Media and Digital Dissidence in Zimbabwe (Palgrave Macmillan, 2022) and New Journalism Ecologies in East and Southern Africa (Palgrave Macmillan, 2023).

Sisanda Nkoala

Sisanda Nkoala is a senior lecturer at the Cape Peninsula University of Technology's Media Department. She is a rhetoric and media scholar. She is currently editing two book volumes looking at the 100 years of radio in South Africa. The author order is agreed.

References

- Alam, L., & Lucas, R. (2011, December). Tweeting government: A case of Australian government use of Twitter. In 2011 IEEE ninth international conference on dependable, autonomic and secure computing (pp. 995–1001). IEEE.

- Basow, S. A. (2016). Evaluation of female leaders: Stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination. In Why congress need women (pp. 85–100). Preager.

- Beltran, J., Gallego, A., Huidobro, A., Romero, E., & Padró, L. (2021). Male and female politicians on Twitter: A machine learning approach. European Journal of Political Research, 60(1), 239–251. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12392

- Bruns, A., & Highfield, T. (2015). Is Habermas on Twitter?: Social media and the public sphere. In A. Bruns, G. Enli, E. Skogerbo, A. O. Larsson, & C. Christensen (Eds.), The Routledge companion to social media and politics (pp. 56–73). Routledge.

- Castells, M. (2008). The new public sphere: Global civil society, communication networks, and global governance. The aNNalS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 616(1), 78–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716207311877

- Chikafa-Chipiro, R. (2020). Tsitsi Dangarembga and the Zimbabwean pain body. Journal of African Cultural Studies, 32(4), 445–447.

- Crilley, R., & Gillespie, M. (2019). What to do about social media? Politics, Populism and Journalism, 20(1), 173–176.

- Etling, B., Roberts, H., & Faris, R. (2014). Blogs as an alternative public sphere: The role of blogs, mainstream media, and TV in Russia's media ecology. Berkman Center Research Publication, (2014-8).

- Evans, M. S. (2012). Who wants a deliberative public sphere?. Sociological Forum, 27(4), 872–895. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1573-7861.2012.01360.x.

- Franks, M. A. (2021). Beyond the public square: Imagining digital democracy. Yale LJF, 131, 427.

- Fuchs, T., & Schäfer, F. (2021, October). Normalizing misogyny: Hate speech and verbal abuse of female politicians on Japanese Twitter. Japan Forum, 33(4), 553–579. Routledge.

- Gelber, A. (2011). Digital divas: Women, politics and the social network. Shorenstein Center Discussion Paper Series.

- Gheytanchi, E., & Moghadam, V. N. (2014). Women, social protests, and the new media activism in the Middle East and North Africa. International Review of Modern Sociology, 1–26.

- Glenwright, D. (2011). Using social media to empower women: A case study from Southern Africa. University of Pavia & Bethlehem University.

- Govender, S. (2020). An evaluation of the use of social media in the enhancement of stakeholder engagement in a public institution [Masters dissertation]. Cape Peninsula University of Technology.

- Grawe, M. N., Nkoala, S. B., & Makwambeni, B. (2023). The use of social media for internal communication within South African local government. Academic Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies, 12(4), 203–213. https://doi.org/10.36941/ajis-2023-0106

- Gray, P. H., Parise, S., & Iyer, B. (2011). Innovation impacts of using social bookmarking systems. MIS Quarterly, 35(3), 629–643. https://doi.org/10.2307/23042800

- Habermas, J. (1989). The public sphere: An inquiry into a category of Bourgeois society.

- Haraldsson, A., & Wängnerud, L. (2019). The effect of media sexism on women’s political ambition: Evidence from a worldwide study. Feminist Media Studies, 19(4), 525–541. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2018.1468797

- Isaak, J., & Hanna, M. J. (2018). User data privacy: Facebook, Cambridge Analytica, and privacy protection. Computer, 51(8), 56–59.

- Jenkins, H., & Ito, M. (2015). Participatory culture in a networked era: A conversation on youth, learning, commerce, and politics. John Wiley & Sons.

- Joiner, R., Cuprinskaite, J., Dapkeviciute, L., Johnson, H., Gavin, J., & Brosnan, M. (2016). Gender differences in response to Facebook status updates from same and opposite gender friends. Computers in Human Behavior, 58, 407–412.

- Kaylor, B. (2019). Likes, retweets, and polarization. Review & Expositor, 116(2), 183–192. https://doi.org/10.1177/0034637319851508

- Koroleva, K., Stimac, V., Krasnova, H., & Kunze, D. (2011). I like it because I(’m) like you - measuring user attitudes toward information on Facebook. Paper presented at the International Conference on Information Systems, Shanghai, China.

- Kreiss, D. (2015). Digital campaigning. In S. Coleman & D. Freelon (Eds.), Handbook of digital politics (pp. 118–135). Edward Elgar.

- Kruikemeier, S., Gattermann, K., & Vliegenthart, R. (2018). Understanding the dynamics of politicians’ visibility in traditional and social media. The Information Society, 34(4), 215–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/01972243.2018.1463334

- Lee, G., & Kwak, Y. H. (2012). An open government maturity model for social media-based public engagement. Government Information Quarterly, 29(4), 492–503. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2012.06.001

- Liu-Thompkins, Y., Maslowska, E., Ren, Y., & Kim, H. (2020). Creating, metavoicing, and propagating: A road map for understanding user roles in computational advertising. Journal of Advertising, 49(4), 394–410. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2020.1795758

- Lord, R. (2021). The state of social media in South Africa. Retrieved June 2, 2022, from https://themediaonline.co.za/2021/07/the-state-of-social-media-in-south-africa/#:~:text=This%20number%20grew%20year%20on,some%20form%20of%20social%20media!

- Majchrzak, A., Faraj, S., Kane, G. C., & Azad, B. (2013). The contradictory influence of social media affordances on online communal knowledge sharing. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 19(1), 38–55.

- Manning, N., Penfold-Mounce, R., Loader, B. D., Vromen, A., & Xenos, M. (2017). Politicians, celebrities and social media: A case of informalisation? Journal of Youth Studies, 20(2), 127–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2016.1206867

- Mano, W., & Ndlela, M. N. (2020). Introduction: Social media, political cultures and elections in Africa. In W. Mano & M. N. Ndlela (Eds.), Social media and elections in Africa (Vol. 2, pp. 1–7). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Mare, A., & Matsilele, T. (2020). Hybrid media system and the July 2018 elections in “post-Mugabe” Zimbabwe. In W. Mano & M. N. Ndlela (Eds.), Social media and elections in Africa (Vol. 1, pp. 147–176). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Matsilele, T. (2019). Social media dissidence in Zimbabwe [PhD dissertation]. University of Johannesburg (South Africa).

- McGregor, S. C., Lawrence, R. G., & Cardona, A. (2017). Personalisation, gender, and social media: Gubernatorial candidates’ social media strategies. Information, Communication & Society, 20(2), 264–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2016.1167228

- Murthy, D. (2018). Twitter. Polity Press.

- Mutsvairo, B. (2016). Digital activism in the social media era. Springer Nature.

- Ncube, G., & Yemurai, G. (2020). Discrimination against female politicians on social media: An analysis of tweets in the run-up to the July 2018 Harmonised Elections in Zimbabwe. In W. Mano & M. N. Ndlela (Eds.), Social media and elections in Africa (Vol. 2, pp. 59–76). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Odeyemi, T. I., & Abati, O. O. (2021). When disconnected institutions serve connected publics: Subnational legislatures and digital public engagement in Nigeria. The Journal of Legislative Studies, 27(3), 357–380. https://doi.org/10.1080/13572334.2020.1818928

- Oxlund, B. (2016). # EverythingMustFall: The use of social media and violent protests in the current wave of student riots in South Africa. Anthropology Now, 8(2), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/19428200.2016.1202574

- Rheault, L., Rayment, E., & Musulan, A. (2019). Politicians in the line of fire: Incivility and the treatment of women on social media. Research & Politics, 6(1), 2053168018816228. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053168018816228

- Sampedro, V., & Avidad, M. M. (2018). The digital public sphere: An alternative and counterhegemonic space? The case of Spain. International Journal of Communication, 12, 22.

- Sharra, A., & Matsilele, T. (2021). This is a laughing matter: Social media as a sphere of trolling power in Malawi and Zimbabwe. In S. Mpofu (Ed.), The politics of laughter in the social media age (pp. 113–134). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Skalli, L. H. (2014). Young women and social media against sexual harassment in North Africa. The Journal of North African Studies, 19(2), 244–258. https://doi.org/10.1080/13629387.2013.858034

- Sobaci, M. Z., & Karkin, N. (2013). The use of twitter by mayors in Turkey: Tweets for better public services? Government Information Quarterly, 30(4), 417–425. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2013.05.014

- Vermeren, I. (2015). Men vs. Women: Who is more Active on social media? Retrieved October 17, 2015 from, https://www.brandwatch.com/2015/01/men-vs-women-active-social-media/

- Waters, R. D., & Williams, J. M. (2011). Squawking, tweeting, cooing, and hooting: Analyzing the communication patterns of government agencies on Twitter. Journal of Public Affairs, 11(4), 353–363.

- Waxa, C., & Gwaka, L. T. (2021). Social media use for public engagement during the water crisis in Cape Town. Information Polity, 26(4), 441–458. https://doi.org/10.3233/IP-200273

- Wigand, F. D. L. (2010, April). Twitter in government: Building relationships one tweet at a time. In 2010 seventh international conference on information technology: New generations (pp. 563–567). IEEE.

- World Wide Worx. (2021). Online retail in South Africa leaps to R30-billion, World Wide Worx, viewed 20 May 2021, from http://www.worldwideworx.com/online-retailin-sa-2021/

- Yarchi, M., & Samuel-Azran, T. (2018). Women politicians are more engaging: Male versus female politicians’ ability to generate users’ engagement on social media during an election campaign. Information, Communication & Society, 21(7), 978–995. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2018.1439985