ABSTRACT

Radical-right populist parties will often try to exploit and ride a wave of popular discontent for their own electoral gain. This paper studies the online populist communication of the leaders of the Rassemblement National (RN) in France in the context of the Gilets Jaunes (GJ) protests and the 2019 European election. It analyses the Twitter activity of these leaders to determine whether they temporarily softened their nativist and exclusionary stances to align their communications with the anti-elitist discourse of the protest movement. We explored this question by employing a quantitative text analysis using R Studio tools of their tweets over a 12-month period in combination with a more qualitative analysis of their output on this social media platform. We carried out tests on bigram frequency, network structure, as well as qualitative analysis of posts on the GJ protests and then compared this data with existing works on the GJ, to identify whether and how the RN adapted its social media discourse at strategic times in the election cycle to better suit the Gilets Jaunes’ demands and themes. The results provide support for the expectation of a strategic modification and moderation of exclusionary populist discourse online with both politicians returning to nativist themes after the European election campaign was over and the GJ mobilisation lost momentum. We therefore suggest that the change in output is part of a strategic moderation or ‘de-demonisation’ in order to gain a wider pool of potential voters and in particular those sympathetic to the protest movement.

Introduction

The Gilets Jaunes (GJ, Yellow Vests) movement in France was one of the most important mass mobilisations in Europe in recent years against the increasing cost of living. Sparked in October 2018, it led to a series of protests organised at roundabouts across the country. By the time of the third protest round on 1 December 2018, 300,000 protesters had rallied at around 700 meeting points, with ensuing clashes with the police (Boyer et al., Citation2020). This issue continued as a major theme in French politics throughout 2019, including during the campaign for the European elections in May. The radical-right Rassemblement National (RN, National Rally) gained 23.3% of the vote, surpassing the ruling La République En Marche (LREM, Republic on the Move) by nearly one percentage point. Many of those votes for the RN were from people living in so-called ‘peripheral France’ including low-level employees and workers, the same people who were attracted by the Gilets Jaunes movement, so called because of their high-visibility yellow vest symbol. The RN gained four million additional voters since the 2014 European elections and its success among GJ protesters was striking. 62% of French people who took part in GJ protests participated in the European election, with 43% of them declaring to have voted for the RN and feeling part of the GJ movement (IFOP, Citation2019). This finding is startling for a movement that presented itself as ‘non-partisan, yet not apolitical’ in the social media spaces where it first found roots (Sebbah et al., Citation2018). Conversely, traditional media have pointed out the links between far-right groups, including the RN, and GJ leaders (Métézeau, Citation2019).

This article aims to understand whether the RN modified its online communication discourse in the run-up to the 2019 European elections in order to prioritise the GJ’s themes and concerns. Our expectation is that RN leaders toned down their usual far-right nativist and exclusionary themes in favour of broader anti-elitist content targeting the ruling political elite. Aligning the RN’s rhetoric with the demands of the GJ could have attracted voters who identified with this movement. The article aims to provide empirical evidence of whether and to what extent populist radical right (PRR) parties strategically prioritise anti-elitist discourse over their more traditional exclusionary discourse in order to attract new voters. Our use of quantitative text analysis in combination with a more qualitative analysis of their output on social media offers a promising method to map changes in far-right populist rhetoric during the electoral cycle – thus adding to other quantitative text analyses of social media campaign content (Stier et al., Citation2018). The article provides a French case study to complement the existing literature on online populist communication (Hameleers, Citation2019a). It also complements and builds on the existing work of Maurer and Diehl (Citation2020) who looked at the Twitter output of several French presidential candidates (including Marine Le Pen) and that of Stockemer and Barisione (Citation2017) who examined the Facebook page of the RN during the period in which Marine Le Pen, now one of the most prominent PRR leaders in Europe, took over the party.

GJ protests mainly took place in areas far away from the metropolitan cities, these locations, known as the périurbain, are often characterised by high rates of unemployment and inequality, and have become strongholds for the RN. This suggests a correlation between political distrust and populist voting, and that short-term, precarious opportunities for social mobility led to calls for systemic change. Similarly, the GJ movement formulated demands for an overhaul of the current French establishment, first expressed on social media, then translated into street mobilisation. Although the GJ did not stand for exclusionary values and priorities (Sebbah et al., Citation2018; Morales et al., Citation2021; Collectif d’enquête sur les Gilets jaunes, Citation2019), analyses showed that their supporters strongly favoured the RN instead of the multiple GJ electoral lists for the 2019 European elections (Chamorel, Citation2019). We first discuss the existing literature on the features of online populist communication and the GJ movement. After outlining our research design and methods, we present the results of a quantitative text analysis of the social media activity of two RN leaders (Marine Le Pen and Jordan Bardella) between June 2018 and September 2019. We carry out tests on bigram frequency, network structure, as well as qualitative analysis of posts on GJ protests. We then compare this data with existing works on the GJ online discourse, to identify whether and how the RN adapted its social media discourse at strategic times in the election cycle to better suit the Gilets Jaunes’ populist demands and themes.

Populist parties and online communication

The literature on populist political communication has grown exponentially and encompasses several sub-fields. We situate our research within studies of political communication which have previously considered how populist actors convey their messages online (Engesser et al., Citation2017; Ernst et al., Citation2017; Hameleers et al., Citation2018; Hameleers, Citation2019a). While recognising the utility of the ‘ideational approach’ to populism, for the purposes of this study we consider populism as a specific political communication style which focuses on people-centrism, anti-elitism – ranging from political elites to mainstream media – and exclusion (Jagers & Walgrave, Citation2007). As Schmuck and Hameleers (Citation2020) point out, despite the different conceptualisations of populism in the literature, it is possible to accommodate them in the concept of populist political communication. In this particular article, we are interested in when this communication focuses on exclusion (including nativist rhetoric on immigration) and anti-elitism (including EU elites and the institutions). Populist politicians cast the people as an in-group that is not adequately represented by the elite out-group (Ernst et al., Citation2017). Populists can present themselves as in-group members and ‘champions of the people’ in their communication aimed at disillusioned voting groups (Bracciale & Martella, Citation2017). Leaders, therefore, become credible anti-elitist sources by following this mechanism of psychological gratification (Hameleers, Citation2019b). Populist identity framing exacerbates this phenomenon because it constructs a boundary between in-group and out-group through the metaphor of the ‘silent majority’ (Hameleers et al., Citation2018).

The existing literature on populist political communication has emphasised its use for strategic purposes, particularly during election times in order to maximise votes (Weyland, Citation2017). The strategic use of negative emotions in particular can successfully amplify previous feelings of victimisation for electoral gains, with emotionalised communication obtaining more reactions than neutral content (Hameleers et al., Citation2017). Exploiting everyday concerns due to a loss of socio-economic status makes PRR objectives digestible to a larger voter share (Krämer, Citation2017) – which in our case might include those who took part in (or at least sympathised with) the Gilets Jaunes protests. This choice reflects the need to differentiate a radical party’s political programme from that of the ruling party, thus exploiting fears and disappointments that build up after the ruling party’s election (Ernst et al., Citation2017).

In electoral campaigns, radical right parties in Western Europe have been found to use populist appeals on both economic and social issues more frequently than mainstream parties (Bernhard & Kriesi, Citation2019). However, the extent that different kinds of populist appeals are made prior to, during and after an election campaign is much less studied. The effect of a particular mobilising episode and nationwide protest, such as the GJ movement in France, has been ignored completely. Schmuck and Hameleers (Citation2020) conducted comparative content analysis of Twitter and Facebook posts by 13 candidates before and after parliamentary elections in Austria and the Netherlands in 2017. They found that all candidates, irrespective of their political leaning, were more likely to use discursive elements of populist communication before than after elections, suggesting that online populist communication is a strategic tool for maximising votes during election season. We wish to test this finding further by looking at whether the RN strategically moderated its populist messages in favour of more anti-elitist content in the run-up to the European elections. In such a way, we hope to add to the emerging literature on how parties systematically vary their populist positions in party competition (Breyer, Citation2022).

Online populist communication as a strategy for the RN and GJ

One common misconception is that, because of its use of populist discourse, the Gilets Jaunes could be interpreted simply as the social movement expression of PRR concerns. However, the protestors focused their messages on anti-elitist themes and time series analysis of online discussions throughout the history of the GJ movement shows that questions of immigration and integration only appeared in debates in the first month of mobilisation. They almost disappeared in all successive protest rounds, while anti-elite sentiment and institutional reform dominated online discussions among the GJ (Morales et al., Citation2021). Further undermining interpretations of the GJ movement as simply an expression of exclusionary radical-right values, only 2 of 166 GJ protesters interviewed for a survey mentioned immigration management as a reason for joining the protests or as a solution to the crisis (Collectif d’enquête sur les Gilets jaunes, Citation2019). Linguistic categories retrieved from Facebook by Guerra et al. (Citation2021) show that the Gilets Jaunes perceive ‘the elite’ to be an obstacle to equality and justice, and that the government’s response is insufficient. We want to know if the RN shifted their message to focus on anti-elitism. Our focus on the online sphere is due to the RN’s changes in campaign methods that have mirrored the explosion in the use of social media by political parties. Indeed, the RN increasingly relies on social media to inform and mobilise its supporters and Le Pen has adopted a direct language aimed at the ‘common man’ and has left traditional PRR themes sandwiched between economic and social proposals (Engesser et al., Citation2017). This softening of radical stances, known as dédiabolisation, has set her apart from her father’s extremism and enlarged her support base (Stockemer & Barisione, Citation2017). She frequently refers to herself as the voice of the French people, addressing concerns of the lower- and lower-middle classes that have also embraced GJ demands.

Somewhat surprisingly, despite the surge in interest in populist radical-right communication, the literature on the use of social media by the RN is rather scant. Scholars have pointed to Le Pen’s growing social media success and the importance of these platforms as a tool to mobilise long-standing and potential voters alike (Hobeika & Villeneuve, Citation2017). Existing research on the RN’s social media content has focused on how Le Pen has insisted on presenting a dehumanised vision of migrants, and Muslims more specifically, in her social media communications (Pietrandrea & Battaglia, Citation2022). Other research has shown that already in the 2017 French presidential election, the probability of Le Pen talking about the people positively and political elites negatively on Twitter was about 50% higher than for her opponents, all while being more negative about immigration than them (Maurer & Diehl, Citation2020). Moreover, in their analysis of Facebook content during the 2019 European elections, Maurer and Béllanger (Citation2021) noted the influence the Yellow Vests protests had on the preponderance of national economic and social issues in the online campaign of French political parties, including the RN. Yet, the strategic element of how social media is used by the party, and how this changes during election cycles, has been ignored, thereby contributing to the importance of a case study on the RN’s online populist communication.

We expect that RN leaders will put less emphasis in their online communications on themes like immigration and national preference (exclusionary populist discourse) at strategic times in the run-up to an election, opting instead for more anti-elitist content targeting political elites. Such a discursive shift could have been implemented to both attract new voters but also reflect the demands of the GJ movement, which had gained public salience since October 2018. The rationale for this assumption is based on the literature previously discussed on the strategic use of populist communication and the attempts by the RN to appear more moderate in order to secure new voters. Our quantitative text analysis will attempt to capture changes in online communication based on politically opportune contexts.

Research design and methods

Our research aim is to assess variations in discourse in the RN’s online communications in light of the rise of the Gilets Jaunes movement during the election cycle leading up to the 2019 European elections. The research question is: to what extent did RN leaders reduce their use of exclusionary language and increase the use of anti-elitist discourse in order to align their communications with the demands of the Gilets Jaunes movement? Social media provide a channel for direct and unmediated communication between politicians and potential voters which makes them suitable for populist communication (Engesser et al., Citation2017). Twitter is particularly apt for this as it plays a central role in hybridising and redefining the traditional cycle of political information and tweets have become a digital version of soundbites (Bracciale & Martella, Citation2017). Indeed, this platform is regularly used by RN leaders because it lends itself well to political campaigning. In order to answer our research question, we adopted a two-pronged approach to text analysis, employing both quantitative and qualitative tools. Quantitative text analysis produces insight into the frequency with which themes in the text are addressed. The additional qualitative analysis can decipher relational and contextual elements behind the raw data, establishing the connections and meanings of political communication. Following the Cambridge Analytica scandal and the ensuing changes in privacy regulation, there are limitations to the data a non-business developer can obtain for free through API settings. Facebook is particularly strict about the application process to retrieve content, including from public pages. This was another reason for opting for Twitter profiles.

Marine Le Pen and Jordan Bardella were chosen for the analysis given their crucial political function, their social media activity, and their known public statements in favour of the GJ movement. Le Pen is an ideal subject for studying the RN’s communication due to her role as party leader and her media prominence. Her status as the RN politician with the highest number of followers (2.3 million Twitter followers as of October 2019) and her tendency to post at least twice a day provide large amounts of data. Bardella had a much inferior number of followers during the period of study (52,200 as of October 2019) but is very active online and he headed the European electoral list for the RN in 2019 and subsequently won a seat as MEP. He has since gone on to become the party’s spokesman and was elected as the RN’s president in November 2022. Most importantly, both leaders have repeatedly stressed the legitimacy of GJ protests. As a result, the Twitter content of both leaders in the selected period is relevant to the analysis. Our dataset consisted of over 6,000 tweets, downloaded through the free tool vicinitas.io. The number of posts and retweets includes our entire chosen time period (June 2018 to September 2019). This allows us to monitor social media activity and discussion topics in the light of key political events. The RN’s official account was not included due to its function as an echo chamber for leaders’ discussion, rather than a valuable forum for party discourse and policy. In fact, nearly the totality of its tweets were retweets of other RN members or advertisements for events around France. Moreover, because of the high number of retweets that the @RNational_off account shared to support electoral efforts, and since vicinitas.io has a cap on downloadable tweets, it was only possible to retrieve posts from May 2019 onwards. This did not provide a complete picture for our case study.

Tweets from these two accounts posted between June 2018 and September 2019 were selected for the analysis (N = 3,113 for Le Pen, N = 3,106 for Jordan Bardella). The period includes, in order: the four months before the first GJ protests took place; the October-January protest phase, with the first protest as well as the highest registered attendance; Emmanuel Macron’s announcement of a grand débat to appease protesters; the period of the European election campaign; and a post-election four-month period, which alongside the pre-GJ period provides a yardstick of comparison for the movement’s impact on the RN’s communication. Vicinitas also shows trends in publication frequency, most employed hashtags, and most mentioned personalities in tweets: this provides useful information on the level of interconnectedness between party members in terms of communication, as well as with other radical-right representatives at the EU level. Using R Studio, we ran tests for bigram (word pair) frequency and co-occurrence networks as well as single word frequency as a robustness test. Important packages used were: Tidyverse, tidytext, ggraph, igraph, stopwords, and ggrepel. Bigram frequency outlines the tendency of certain themes to recur more than others, in order to draw potential voters’ attention. Bigram analysis provides insights into the context in which words are used, instead of merely counting the number of times a word is used. This also allows us to filter cases in which a word of interest is used in a context that is not relevant to the analysis. Our analysis produced a total of 21,992 bigrams. The vast majority of these were utilised just once or twice over the entire period. We therefore only included those bigrams that had been used at least 3 times (N = 1,494). From this list we coded relevant bigrams as either ‘Exclusionary’ or ‘Anti-elitist’ and this allowed us to create our dictionary (see Appendix A).

To allow for clearer comparisons between different political events and their impact on RN communication, we break down bigram frequencies into four-month periods (June to September 2018, October 2018 to January 2019, February to May 2019, and June to September 2019). We also repeated this process with individual word counts as means to test the findings. Repeated auxiliary verbs, prepositions, and conjunctions were deleted from the final list as they do not constitute political lexicon or add ideological elements to the analysis. In fact, we were forced to manually remove several of them because R packages for the identification of French stop words (i.e., articles, prepositions, and other logical connectors) have not been perfected for social sciences and still rely on discourse elements of literary analysis. We also removed hashtags like #onarrive and #rentréemlp as well as Twitter handles of associated parties, as they are not significant to the object of our study. This improves text functionality and completes the ‘normalisation process’, which makes our approach more efficient (Bhadane et al., Citation2015; Günther & Quandt, Citation2016).

Through co-occurrence analysis, we were interested in understanding how bigrams in our data were connected to one another. The bigram frequency analysis only considers the bigrams in isolation, leaving their interconnectedness unaddressed. This test provides a network representation of how individual demands are articulated as broader frames in populist communication. Moreover, when connecting co-occurrences with text polarity, we can delineate classes of negative words and identify how a certain set of ideological stances elicits emotional responses (Antonakaki et al., Citation2017). In the case of the RN, it is useful to determine how combinations of political instances spark negative feelings and feed into the deprivation narrative common to the discourse of the GJ. As the literature outlines, populist rhetoric and style activate those citizens whose socialisation and current situation make them keen to believe in congruent stimuli (Hameleers, Citation2019b). Co-occurrence could provide insights into how that is achieved and made coherent through a communication strategy.

Our qualitative analysis relies on a targeted research of Le Pen and Bardella’s tweets connected to GJ demands and lexicon. We checked for similarities and references to events from GJ protests, based on existing literature on the movement as well as word strings obtained from the co-occurrence network analysis. The GJ lexicon and word strings were researched manually in the TweetDeck search engine bar for all periods we observed, using this functionality to research original tweets by the accounts @MLP_officiel and @J_Bardella. We also included textual descriptions of multimedia materials which had to be removed for the purpose of R text analysis. We would expect that both Le Pen and Bardella express support for the GJ movement throughout the months of protest, online as much as in traditional media, and have done so with a language familiar to their target audience. We also expect the two to have connected through relevant hashtags used to follow the discussion during the December 2018 mobilisation, in which social media attention on violent protests was at its highest (Boyer et al., Citation2020).

Results

Bigram frequencies

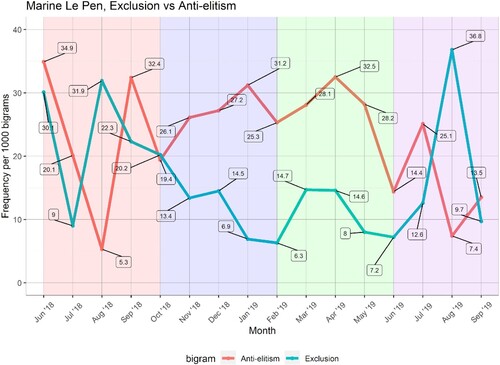

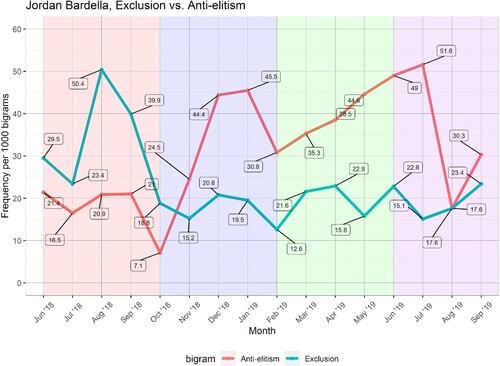

Through bigram frequency, we track changes in the number of references to exclusionary and anti-elitist themes across time for Le Pen and Bardella. Our dictionary includes the most used bigrams for both leaders that were coded as either ‘exclusionary’ or 'anti-elitist' and the same technique was employed for individual words (see Appendix B). We build on previous research in this area by constructing the dictionary of populist phrases by closely following the technique employed by Maurer and Diehl (Citation2020). This includes a systematic process of qualitative pre-analysis and subsequent reliability testing of the dictionaries to ensure that the bigrams selected had been used in the context of populist statements. We found that the bigrams chosen are in line with the conceptualisation and operationalisation of populist communication strategies outlined by Ernst et al. (Citation2017). For the theme of exclusion, we have included bigrams such as ‘illegal immigration’ and ‘asylum seekers’ and for the theme of anti-elitism, we have included bigrams such as ‘European Union’ and ‘French people’ but we decided not to use ‘Emmanuel Macron’ and other variations using the name of the French President as this would have skewed the results. and provide an overview of the frequency with which Le Pen and Bardella employ exclusionary and anti-elite language throughout our selected time frame. Frequencies are shown per 1,000 bigrams to better compare the frequencies of the two individuals.

Figure 1. Comparison of exclusionary and anti-elitist language for Marine Le Pen between June 2018 and September 2019.

Figure 2. Comparison of exclusionary and anti-elitist language for Jordan Bardella between June 2018 and September 2019.

The results from the bigram frequency analysis will be discussed in a series of periods. Period 1 covers June 2018 to September 2018; Period 2 covers October 2018 through January 2019, thus including the beginning and peak of the GJ protests; Period 3 covers February through May 2019, thus including the EU election campaign in France; and Period 4 covers June 2019 through September 2019, the remainder of our data set.

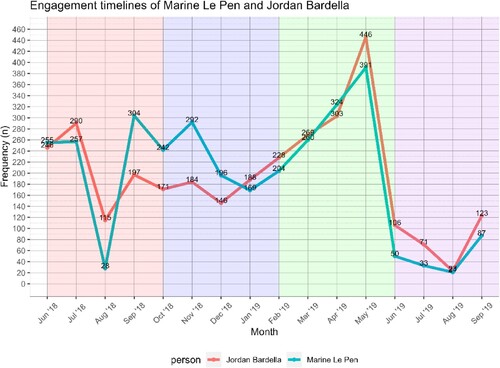

In and , the shaded areas cover the respective periods. Period 2 commences with an online petition against fuel price increases gaining traction prior to the GJ protests and covers the first GJ protests. Period 3 covers the 2019 European elections.

For both Le Pen and Bardella, anti-elitist language dominates most of our data set. During the periods from October 2018 to May 2019, marked by the GJ movement and the European elections, exclusionary language is nowhere near as frequent as anti-elitist language. It is not that exclusionary language frequency necessarily decreases considerably, but rather that it does not increase by any meaningful amount compared to anti-elitist language.

Period 1 – June 2018 to September 2018 Bigram frequency for June to October 2018 shows a general commitment to traditional radical-right exclusionary themes, particularly in the month of August 2018. Both leaders heavily discuss anti-migration discourse and nationalist party events around the time of the rentrée. Le Pen also uses anti-establishment language frequently, more so than exclusionary language except for August and October. Conversely, in Bardella’s frequencies for the two categories, exclusionary language dominates for the entire first period more in line with our expectations. For instance, he uses the bigrams submersion migratoire and immigration massive frequently. The specific case of the migrant rescue ship Aquarius was mentioned 23 times in this period. Qualitative analysis of the tweets reveals that migration is often spoken of in terms of a ‘mass flood’.

Period 2 – October 2018 to January 2019 During Period 2, which opens when the GJ protests began, references to exclusion/nativism become less frequent in both leaders’ content. Meanwhile, and show steep increases in the use of anti-elitist language from both Le Pen and Bardella. This is visible in the blue-shaded area in the figures. The impact of the GJ protests on French political life is shown by the fact that issues connected to the protest, such as the bigram ‘spending power’ (pouvoir d'achat) is used 47 times. Interestingly, we also see the appearance of references to the European Union. The bigram is used 22 times by Le Pen (2nd) and 11 times by Bardella (11th). At this stage, Le Pen makes reference to peuple francais 21 times and when looking at a simple word count, the singular peuple is mentioned 51 times for Le Pen in Period 2, putting it in 10th place in her output, and 33 times for Bardella, putting it in 16th place in his output. This suggests a focus on the agitated domestic setting brought in by the Gilets Jaunes and their demands.

Period 3 – February 2019 to May 2019 In this period, exclusionary language is considerably less frequent than anti-elitist language in both leaders’ content. The difference is largely linked to the EU as a perceived elitist institution and the European elections. Several bigrams related to the elections appear amongst the most used bigrams for both leaders. Le Pen frequently uses the bigrams Union europénne (63), Parlement européen (24), and alliance européenne (18). Bardella frequently uses the bigrams Union européenne (57) and Parlement européen (33).

In Period 3, both leaders produce the highest number of tweets, as seen in , and the European election campaign takes centre stage. We notice a tenfold difference between the use of exclusionary language and references to the campaign itself or the EU (anti-elitist language), in addition to a reduced breadth of nativist themes. The temporary renunciation of exclusionary themes is confirmed by two elements: Le Pen refers to migration far less frequently (immigration massive is used 18 times), while Bardella mentions submersion migratoire and immigration massive 15 and 14 times, respectively. Thus, it appears that the European election campaign relies on intense criticism of perceived elites like Brussels bureaucrats rather than on exclusionary populist discourse.

Figure 3. Engagement timeline for Marine Le Pen and Jordan Bardella’s respective Twitter activity between June 2018 and September 2019.

Period 4 – June 2019 to September 2019 In Period 4, immediately following the European elections, there is a general decrease in Twitter activity. This is shown in the decreasing frequencies in the use of both exclusionary and anti-elitist language for both leaders. After an important and highly active period being over, it would be natural to expect a downward trend on account of the summer season. However, Le Pen does have a particularly active August which is no doubt tied to the news surrounding the Ocean Viking humanitarian ship chartered by the maritime-humanitarian organisation SOS Méditerranée. There is an increase in activity of both Le Pen and Bardella in September 2019, after the holidays. The EU dimension disappears in favour of domestic events but – crucially to our investigation – there is no immediate return to exclusionary discourse. The findings are therefore inconclusive with regard to our expectation regarding a return to nativism once the European elections and the GJ momentum come to an end. After the GJ protests and the EU elections, the use of anti-elitist language certainly declines but the picture regarding exclusionary discourse is far more mixed ( and ).

Co-occurrence networks

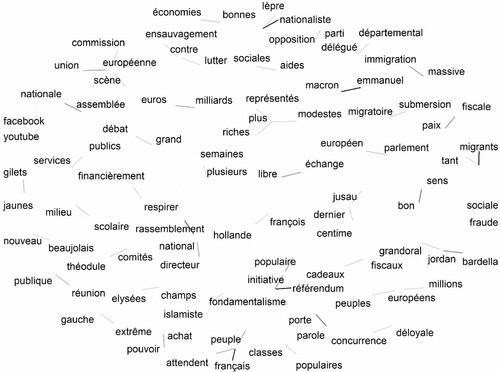

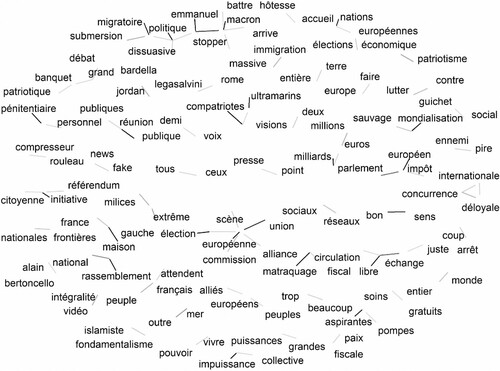

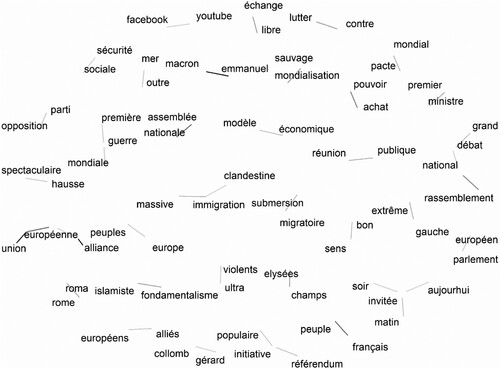

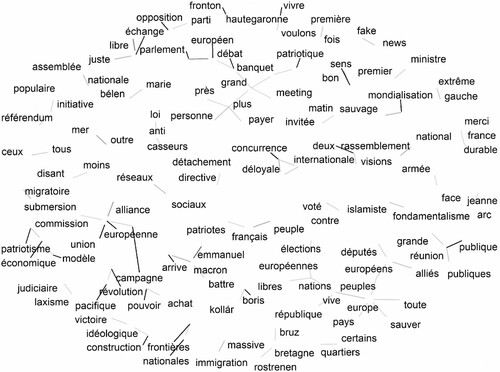

Co-occurrence networks for each period present clusters of interconnected bigrams and themes in the candidates’ Twitter feeds which individual bigram frequency cannot fully capture. We supplemented this network analysis with qualitative manual TweetDeck research to understand how Le Pen and Bardella attempted to take advantage of the Gilets Jaunes’ populist demands at the peak waves of protests and during the course of the European election campaign. Our analysis found a numerical increase in direct and indirect references to GJ demands from November 2018 to July 2019. Meanwhile, the number of bigrams relating to exclusionary themes plateaued in the same period. and present an overview of nodes for Le Pen and Bardella, respectively, in Period 2. They were chosen as they encompass the largest number of GJ themes, which we discuss for the whole-time frame of our study in more detail below. and show the nodes for Le Pen and Bardella, respectively, for Period 3.

Figure 4. Le Pen’s co-occurence network, Period 2 (October 2018–January 2019). The line opacity shows the frequency of the bigram.

Figure 5. Bardella’s co-occurence network, Period 2 (October 2018–January 2019). The line opacity shows the frequency of the bigram.

Exclusionary word nodes in the networks are all typical of the RN’s radical-right discourse. They include ‘clandestine migration’, ‘anarchical migration’, ‘mass migration’, ‘Islamic fundamentalism’, ‘Muslim religion’, ‘Islamist government’, ‘anti-white racism’, and ‘migration-deterrent policy’. While they appear in all co-occurrence network graphs, their number significantly decreases from October to November 2018, instead yielding to GJ-inspired word nodes such as ‘purchasing power’, ‘artificial majority’, ‘political class’, and ‘oppressive taxes’. This trend is comparable to the one outlined in the quantitative text analysis using bigrams, with exclusionary bigrams making a comeback in Period 4.

As the protests gain strength, Le Pen and Bardella openly discuss GJ actions and demands on social media using remarkably similar populist language. The two RN figures speak of ‘excess taxation’, ‘tax overkill’, ‘fiscal peace’, ‘social assistance’, ‘living with dignity’, ‘Champs-Élysées’ (the meeting point for weekly protests), ‘fight against Macron’, ‘national debate’, and ‘popular initiative referendum’. Similarly, Bardella copies a recurring GJ slogan in arguing that increased purchasing power will result in them being able to respirer financièrement: that is, ‘being able to breathe’ from excessive fiscal pressure and focusing more on living standards. Bardella’s tweet from 25th November 2018, summarising an intervention on BFMTV, employs those exact words: ‘This government of shame has DONE EVERYTHING [sic] to intimidate the French and dissuade them from going out to demonstrate! #GiletsJaunes are not vandals, but angry citizens who wish to be able to breathe at the end of the month!’ On 15th December 2018, Bardella even presented the RN’s electoral programme as a response to GJ claims: ‘The French expect a policy of social, fiscal and democratic justice! The @RNational_off defends: ✅ Popular initiative referendum ✅ –5% on electricity/gas tariffs ✅–10% on the first three tax brackets #GiletsJaunes’. Tweets from 21st and 22nd December 2018 deny that the RN is trying to ‘dishonestly appropriate’ the demands of the movement, instead having supported similar demands for a long time.

On 18th January 2019, Le Pen also directly spoke of an integration of GJ points into her presidential programme: ‘All the demands of the #GiletsJaunes were in my 144 presidential commitments. It is Emmanuel Macron who is creating chaos: to a harmful policy, he has added incredible contempt for the vast majority of French people!’ A similar message was formulated in a tweet from 21st February 2019: ‘In my 144 presidential commitments, there are at least 60 that correspond to the demands or concerns expressed by the #GiletsJaunes - whether in terms of purchasing power, representativeness… ’

When looking up these expressions through qualitative research, we find that Le Pen and Bardella employ identical GJ themes and hashtags in some tweets, including in the run-up to the European elections during Period 3, but also towards the end of Period 2. Le Pen’s tweet from 17th February 2019 argues that ‘[f]iscal dispossession and the reduction in purchasing power are not a GJ fantasy’. Already on 13th January that year, Le Pen made the link between the GJ demands and the European elections: ‘In the context of the healthy popular revolt of the Gilets Jaunes, these #Elections2019 offer an opportunity to unravel the political crisis born of the President's blindness, intransigence, class contempt, tax spoliation and human disconnection.’ Bardella’s tweet from 18th April 2019 similarly states that ‘[i]t is necessary to go and vote en masse on 26th May to increase purchasing power and propel fiscal reform’.

Co-occurrence networks in Period 3, focusing on the European election campaign, present a similar picture. Tweets from that time are not limited to criticising ‘unfair international competition’ or discussing ‘economic patriotism’ for ‘free nations’. They also present RN leaders’ discussion of domestic issues close to GJ demands. One node in Le Pen’s network () puts ‘the fight against Macron’ in direct relation with the RN campaign slogan 'We are coming'. There is also mention of the need for a change of economic model, a ‘new harmony’, and ‘extreme left militias’.

At the same time, Bardella links ‘stop’ and ‘Macron’ while employing GJ expressions such as ‘fiscal peace’ and ‘collective powerlessness’. Bardella employs the latter in several tweets in May, with one from 16th May 2019 stating:

Letting Macron and his friends win means legitimising his actions, encouraging him to speed up his disastrous policies, while scorning the courage and patience of those who have been fighting for our dignity for months. Let’s declare a GENERAL MOBILISATION [sic]!

The current level of petrol prices is INSURMOUNTABLE [sic] for the French. It's even higher than at the start of the #GiletsJaunes movement, and that's because of TAXES [sic]. It's time to mobilise and blow the whistle at the end of playtime!

Discussion

The results provide support for our initial expectation of a strategic modification and moderation of the RN’s exclusionary and nativist discourse online during the high period of GJ mobilisation and the European election campaign. However, while Le Pen and Bardella do return to exclusionary themes after the election is over and the GJ mobilisation loses momentum, the trend is not as pronounced as one might expect. One cannot expect to establish causality only through mass data analysis of social media content. However, we see a clear correlation between the emergence of a populist protest movement and the party’s prioritisation of anti-elitist discourse over exclusionary discourse. In the context of a populist denunciation of the system such as the GJ protests, such a discursive approach could be beneficial for the party’s electoral fortunes. Indeed, it was noted by many commentators how the RN had attempted to ride the wave of the GJ protests for their own electoral gain. This does not mean that the RN had never used such anti-elitist language before; rather the variations in exclusionary bigram frequencies and the presence of GJ themes in co-occurrence networks show a populist shift connected to political opportunities, culminating in the 2019 European elections. This new message was designed to appeal to the supporters of a movement like the GJ, with whom the label of a silent majority lost in an elitist system resonates. Exclusionary and nativist ideology is thus temporarily put aside to capitalise on uncertainty and partial realignments, in a strategy of ‘catch-all populism’ (Surel, Citation2019, p. 1236).

Regarding blame attribution, and particularly in the qualitative assessment of tweets, it is noticeable that RN leaders employ a well-established logic of in-group versus out-group. Nevertheless, what constitutes the out-group varies according to the RN’s political agenda and is contingent on domestic and international priorities. In Period 1, dimensions of both anti-elitist and exclusionary populism co-exist: exclusionary themes remain frequent and obtain a similar score to the ones relating to anti-elitist populism. At the moment that the GJ movement arises with its populist demands, the RN pivots to different targets in its social media discourse. Besides the progressive reduction in the use of exclusionary terms, the repetition of Gilets Jaunes shows a commitment to online debate related to their demands. It also hints at an interest in the evolution of the protest and its root causes, for which the qualitative analysis has provided examples. Due to data access constraints, we were not able to test our expectations using Facebook, which is known to achieve higher populism values than Twitter due to its digital architecture (Ernst et al., Citation2017).

Tweets like the ones from 16 May 2019 (see Results section) support a general mobilisation against Macron. They further demand a direct response to the anti-elitist message advocated by the GJ. Through the qualitative analysis and co-occurrence network strings, we also demonstrated how some tweets employ key GJ themes and language for campaigning purposes. This implies a discursive framework in which the RN and its candidates stand for anti-elitist values and attitudes, just like the Gilets Jaunes. The repetition of GJ themes is not limited to the time of the most violent protests in November and December 2018. In fact, between March and May 2019, Le Pen and Bardella either explicitly mentioned the group’s actions or referenced topics originating from the protesters’ online communities. While correlation does not imply causation, the choice to directly mention the movement as part of their election campaign content connotes a specific RN adaptability in ‘softening’ exclusionary content and presenting topics they hope will be appreciated by a wider audience, including GJ sympathisers. In the absence of one unified GJ electoral list in the European elections, appropriating messages that the movement first diffused is likely to have had an impact on the way the RN received the vote of GJ supporters.

The RN’s production of such social media content gives support to Hameleers et al’s (2018) findings on populist cues, at least as far as the supply side is concerned. Our case study does not have the data to prove a conclusive electoral link between the RN’s online communication strategy and the way GJ sympathisers voted for the RN. Nonetheless, 71% of RN voters at the European elections also defined their vote as a way to sanction the President and the government’s policies (IFOP, Citation2019, p. 42). We found that Le Pen and Bardella sent populist cues aligned with GJ stances in their choice of targets and language. By arguing online that the GJ won important concessions for the whole of France, and that Macron’s decision-making and campaign undermined them, the RN was able to actively exploit group relative deprivation. Another reason to presume that the RN temporarily appropriated the GJ’s populist themes for electoral gain is provided by studies of populist attitudes among the protesters themselves. The depiction of a hard-working and unrepresented majority is frequently upheld in the GJ online world as much as in surveys. This self-perception is closely intertwined with the idea of having insufficient resources compared to the pressures and demands of the current system. When Guerra et al. (Citation2019) interviewed GJ protesters, over 95% of them accused politicians of ‘talking too much’, stating that ‘the political differences between the elite and the people are larger than the differences among the people’.

Qualitative social media research (Sebbah et al., Citation2018) confirms that there was a majority of non-partisan GJ members. It is expected that a large majority, if not the entirety of adherents, would have been receptive to congruent populist stimuli like the ones RN leaders crafted and spread. Whether that effectively translated into voting behaviour cannot be answered here. For now, it seems that the RN has produced electoral messages which resonate with the value set defended by GJ protesters. However, it is crucial to stress how a temporary transformation of the RN’s online discourse does not imply that the party has renounced its PRR ideology. Several observers have discussed the RN leadership’s frequent attempts at a strategic moderation or ‘de-demonisation’ in order to gain access to the mainstream political system. To break the glass ceiling of institutionalised politics means reconciling vote-seeking and policy-seeking actions. It is about convincing undecided voters to choose a party whose positions would have not been initially considered because of their extremism. As our Period 4 results prove, ad hoc ‘de-demonisation’ does not compromise the strength of the radical ideology which has been the cornerstone of the RN since its foundation. This is especially true in light of the negative rhetoric outlined in certain co-occurrence network word strings – namely in reference to migrants and the EU’s supposed ‘open-border policy’. Exclusionary themes are still a tenet of the RN's discourse, and the move towards more anti-elitism serves a logic of catch-all populism rather than a genuine ideological moderation. Lastly, it is important to stress that due to data access constraints by the online platforms, our findings were limited to two RN leaders and to Twitter, whereas GJ participants are known to prefer Facebook. However, this should not be considered as undermining the validity of a possible RN strategisation around GJ themes as it is likely that their communication strategies and discourse were similar across the two social media platforms.

Conclusion

Our study of the RN’s online populist communication in the context of the Gilets Jaunes protests and the 2019 European elections aimed to analyse the Twitter activity of PRR party leaders and determine whether they temporarily softened their exclusionary stances to align their communications with the anti-elitist demands of the Gilets Jaunes movement. Our results showed that, as the protests began and the European election campaign-built momentum, nativist content such as anti-immigration stances considerably lost out to more anti-elitist themes and content. The Gilet Jaunes movement prompted the RN leaders to focus their discourse more on socio-economic topics without completely abandoning immigration. Although party leaders resumed their focus on exclusionary policies when the electoral campaign and debate around it drew to an end in August 2019, we did not see a return to nativism as seen in Period 1. Our findings demonstrate that the RN modified its discourse to appeal to GJ members and sympathisers in the run-up to the European vote. This research therefore contributes to the theoretical debate on whether PRR parties strategically prioritise anti-elitist discourse over their more traditional exclusionary discourse in order to attract new voters. It also contributes to debates about mainstreaming and strategic moderation of the RN in particular (Peace & Paxton, Citation2024). The Gilets Jaunes expressed anti-elitist populist stances, insisting on the lack of popular representation and welfare guarantees. It appears that the RN increasingly published social media content on these topics, with targeted references to GJ activities and their role in trying to rock the established political system. Le Pen and Bardella launched negative personal attacks towards Macron, insisted on praising the GJ as an expression of the French people fighting for their rights, and employed populist discourse common to the GJ. Our findings complement the analysis of the RN’s manifesto, speeches and interviews for the 2019 European elections which noted an emphasis on populist rather than nationalist themes, opposing people’s sovereignty not to ethnic out-groups, but to the EU as part of the political elite (Rodi et al., Citation2023). The results are also in line with the trends that Maurer and Béllanger (Citation2021) discovered regarding the use of Facebook by the RN in the months leading up to the 2019 European elections and in particular the subordinate position of the immigration issue.

The case study has provided an investigation into the online populist communication of the main PRR party in France, thus offering country-specific evidence that was missing from the literature. It has explored how congruent messages might be diffused to activate psychological mechanisms of blame attribution and group relative deprivation which underpin populist identification. In the past few years there has been increasing academic attention on the socio-cultural and psychological rationale that can prompt adherence to populist values, in spite of the previous ideological affiliation of an individual. By focusing on the Gilets Jaunes and their self-perceived status, the article provides an example of how these motivations play out in the French context. Our findings suggest that the so-called ‘de-demonisation’ of the RN is not a definitive abandonment of radical-right values, but a contingent effort to broaden the electoral offer for non-partisan, disillusioned voters like GJ protesters and sympathisers. The latter finding deserves further exploration through the effective monitoring of social media content at times of other future crises with an anti-establishment focus. For instance, it would be interesting and relevant to see whether Le Pen and Bardella once again preferred anti-elitist discourse over nativist tropes during the 2019 strikes against Macron’s pension reform, or during the 2022 electoral cycle when it was suggested that Le Pen in particular tried to soften her image to contrast with the far-right candidate Eric Zemmour.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, T.P., upon reasonable request.

Author contributions

L.P. contributed to conceptualization, investigation, methodology, and writing – both original draft preparation and review & editing.

T.P. contributed to investigation, methodology, project administration, validation and writing – both original draft preparation and review & editing.

M.N.P. contributed to data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, software and validation.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Lucia Posteraro

Lucia Posteraro works at the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH). She holds a Master's degree in Human Rights and Humanitarian Action from Sciences Po Paris, with a specialisation in gender equality and diplomacy. She has worked in journalism, communications, policy analysis and research, and event organisation. She has covered roles in institutions such as the European Parliament, UNESCO and several civil society organisations.

Timothy Peace

Timothy Peace is a Senior Lecturer in Politics at the University of Glasgow where he teaches Comparative Politics and Qualitative Methods. He completed his PhD at the European University Institute and has held postdoctoral positions at the Université du Quebec à Montréal and the University of Edinburgh. He has published on social movements, political parties and the politics of migration and is the author of European Social Movements and Muslim Activism: Another World but with Whom? (Palgrave 2015). He is currently the Principal Investigator of the project ‘French local government and the Rassemblement National (RN)’ funded by the Royal Society of Edinburgh.

Marius Nyquist Pedersen

Marius Nyquist Pedersen is a researcher at the Norwegian Defence Research Establishment (FFI), working on climate and security issues and the Norwegian Armed Forces. He is a graduate of Sciences Po Paris, where he obtained a Master of Arts in International Security, with specialisation in Intelligence Studies and the Middle East. He also holds a Bachelor of Arts in International Relations with a specialisation in advanced quantitative methods. This included extensive tuition in the use of the statistical software R Studio.

References

- Antonakaki, D., Spiliotopoulos, D. V., Samaras, C., Pratikakis, P., Ioannidis, S., & Fragopoulou, P. (2017). Social media analysis during political turbulence. PLoS One, 12(10), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0186836

- Bernhard, L., & Kriesi, H. (2019). Populism in election times: A comparative analysis of 11 countries in Western Europe. West European Politics, 42(6), 1188–1208. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2019.1596694

- Bhadane, C., Dalal, H., & Doshi, H. (2015). Sentiment analysis: Measuring opinions. Procedia Computer Science, 45, 808–814. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2015.03.159

- Boyer, P. C., Delemotte, T., Gauthier, G., Rollet, V., & Schmutz, B. (2020). Les déterminants de la mobilisation des gilets jaunes. Revue économique, 71(1), 109–138. doi:10.3917/reco.711.0109

- Bracciale, R., & Martella, A. (2017). Define the populist political communication style: The case of Italian political leaders on Twitter. Information, Communication & Society, 20(9), 1310–1329. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2017.1328522

- Breyer, M. (2022). Populist positions in party competition: Do parties strategically vary their degree of populism in reaction to vote and office loss? Party Politics, 29(4), 672–684. https://doi.org/10.1177/13540688221097082

- Chamorel, P. (2019). Macron versus the Yellow Vests. Journal of Democracy, 30(4), 48–62. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2019.0068

- Collectif d’enquête sur les Gilets jaunes. (2019). Investigating a protest movement in the heat of the moment. Conducting a questionnaire-based survey among the gilets jaunes. Revue française de science politique, 69(56), 869–892. https://doi.org/10.3917/rfsp.695.0869

- Engesser, S., Ernst, N., Esser, F., & Büchel, F. (2017). Populism and social media: How politicians spread a fragmented ideology. Information, Communication & Society, 20(8), 1109–1126. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2016.1207697

- Ernst, N., Engesser, S., Büchel, F., Blassnig, S., & Esser, F. (2017). Extreme parties and populism: An analysis of Facebook and Twitter across six countries. Information, Communication & Society, 20(9), 1347–1364. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2017.1329333

- Guerra, T., Alexandre, C., & Abrial, S. (2021). Enquêter sur les Gilets jaunes. Sociologie politique d’un mouvement social à partir d’une enquête diffusée sur les réseaux sociaux. Statistique et Société, 9(1–2), 21–37.

- Guerra, T., Alexandre, C., & Gonthier, F. (2019). Populist attitudes among the French Yellow Vests. Populism, 3(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1163/25888072-02021039

- Günther, E., & Quandt, T. (2016). Word counts and topic models: Automated text analysis methods for digital journalism research. Digital Journalism, 4(1), 75–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2015.1093270

- Hameleers, M. (2019a). They caused our crisis! The contents and effects of populist communication: Evidence from The Netherlands. In O. Feldman, & S. Zmerli (Eds.), The psychology of political communicators: How politicians, culture, and the media construct and shape public discourse (pp. 79–98). Routledge.

- Hameleers, M. (2019b). To like is to support? The effects and mechanisms of selective exposure to online populist communication on voting preferences. International Journal of Communication, 13(2019), 2417–2436.

- Hameleers, M., Bos, L., & De Vreese, C. H. (2017). “They Did It”: The effects of emotionalized blame attribution in populist communication. Communication Research, 44(6), 870–900. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650216644026

- Hameleers, M., Bos, L., Fawzi, N., Reinemann, C., Andreadis|, I., Corbu, N., Schemer, C., Schulz, A., Shaefer, T., Aalberg, T., Axelsson, S., Berganza, R., Cremonesi, C., Dahlberg, S., de Vreese, C.H., Hess, A., Kartsounidou, E., Kasprowicz, D., Matthes, J.…Weiss-Yaniv, N. (2018). Start spreading the news: A comparative experiment on the effects of populist communication on political engagement in sixteen European countries. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 23(4), 517–553. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161218786786

- Hobeika, A., & Villeneuve, G. (2017). Une communication par les marges du parti? Réseaux, 202–203(2–3), 213–240. doi:10.3917/res.202.0213

- IFOP. (2019). Européennes 2019: Profil des Électeurs et Clefs to Scrutin. Opinion poll. Retrieved May 27, 2019, from https://www.ifop.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/116339-Rapport-JDV-COMPLET-d%C3%A9taill%C3%A9_2019_05.27.pdf.

- Jagers, J., & Walgrave, S. (2007). Populism as political communication style: An empirical study of political parties’ discourse in Belgium. European Journal of Political Research, 46(3), 319–345. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2006.00690.x

- Krämer, B. (2017). Populist online practices: The function of the Internet in right-wing populism. Information, Communication & Society, 20(9), 1293–1309. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2017.1328520

- Maurer, P., & Béllanger, S. (2021). France: Parties’ communication strategies after the 2017 Earthquake. In J. Haßler, M. Magin, U. Russmann, & V. Fenoll (Eds.), Campaigning on Facebook in the 2019 European Parliament election: Informing, interacting with, and mobilising voters (pp. 87–102). Springer.

- Maurer, P., & Diehl, T. (2020). What kind of populism? Tone and targets in the Twitter discourse of French and American presidential candidates. European Journal of Communication, 35(5), 453–468. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323120909288

- Métézeau, F. (2019). Derrière les “gilets jaunes”, l’extrême droite en embuscade. Radio France. https://www.radiofrance.fr/franceinter/podcasts/secrets-d-info/derriere-les-gilets-jaunes-l-extreme-droite-en-embuscade-1918761.

- Morales, P. R., Cointet, J. P., Benbouzid, B., Cardon, D., Froio, C., Metin, O. F., Ooghe Tabanou, B., & Plique, G. (2021). Atlas multi-plateforme d’un mouvement social: le cas des Gilets jaunes. Statistique et Société, 9(1-2), 39–77.

- Peace, T., & Paxton, F. (2024). Populist pragmatism: the nationalisation of local government strategies by the Rassemblement National. Acta Politica, 59. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41269-023-00292-9

- Pietrandrea, P., & Battaglia, E. (2022). “Migrants and the EU”. The diachronic construction of ad hoc categories in French far-right discourse. Journal of Pragmatics, 192, 139–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2022.02.012

- Rodi, P., Karavasilis, L., & Puleo, L. (2023). When nationalism meets populism: Examining right-wing populist & nationalist discourses in the 2014 & 2019 European parliamentary elections. European Politics and Society, 24(2), 284–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/23745118.2021.1994809

- Schmuck, D., & Hameleers, M. (2020). Closer to the people: A comparative content analysis of populist communication on social networking sites in pre- and post-Election periods. Information, Communication & Society, 23(10), 1531–1548. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2019.1588909

- Sebbah, B., Loubère, L., Souillard, N., Thiong-Kay, L., & Smyrnaios, N. (2018). Les Gilets jaunes se font une place dans les médias et l’agenda politique. Laboratoire d’Études et de Recherches Appliquées en Sciences Sociales: Université de Toulouse. https://hal-amu.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02120478/document.

- Stier, S., Bleier, A., Lietz, H., & Strohmaier, M. (2018). Election campaigning on social media: Politicians, audiences, and the mediation of political communication on Facebook and Twitter. Political Communication, 35(1), 50–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2017.1334728

- Stockemer, D., & Barisione, M. (2017). The ‘new’ discourse of the Front National under Marine Le Pen: A slight change with a big impact. European Journal of Communication, 32(2), 100–115. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323116680132

- Surel, Y. (2019). How to stay populist? The Front National and the changing French party system. West European Politics, 42(6), 1230–1257. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2019.1596693

- Weyland, K. (2017). A political–strategic approach. In C. R. Kaltwasser, P. Taggart, C. Ochoa Espejo, & P. Ostiguy (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of populism (pp. 48–72). Oxford University Press.

Appendices

Appendix A – Top bigram counts per candidate

Top 30 bigrams for Marine Le Pen, per period.

Top 30 bigrams for Jordan Bardella, per period.

Appendix B – Top 30 word counts per candidate

Top 30 words for Marine Le Pen, per period.

Top 30 words for Jordan Bardella, per period.