Abstract

Even before ageing became a challenge to society, it already was for social work professionals. What interested the social work professionals were the older people who accumulated low incomes, poverty, loneliness, isolation, disease and several outbuildings. The increasing number of older and much older people reconfigured the intervention of professionals in this area. This intervention is in accordance with the policies of the welfare state, based on the rights and human dignity and a paradigm of social development oriented to social cohesion. The professionals are now responsible for older people policies in social and health care areas. The article includes an analysis of the relationship between social work, ageing and policies for older people and some exploratory results obtained through the analysis of relevant documents that allowed us to characterise the field of social work intervention with older people in the social security system and field of social action. This integrated analysis in a context of economic crisis takes a critical perspective on the impacts of reconfiguration policies for the older people and social work in those days.

Mesmo antes do envelhecimento se constituir um desafio para a sociedade, este já o era para os profissionais de serviço social. O que interessava ao serviço social eram as pessoas com mais idade que acumulavam baixos rendimentos, pobreza, solidão isolamento, doenças e dependências várias. O aumento do número das pessoas idosas e muito idosos reconfigurou a intervenção dos profissionais nesta área. Esta intervenção é configurada de acordo com as políticas do estado de bem-estar, fundada nos direitos e dignidade humana e num paradigma de desenvolvimento social orientado para a coesão social. Os profissionais de serviço social são hoje responsáveis pela estruturação das políticas de velhice e de cuidados sociais e de saúde, integrados. O artigo inclui uma análise à relação entre o serviço social, o envelhecimento e as políticas de velhice e alguns resultados exploratórios decorrentes da análise de documentos relevantes que nos permitiram caraterizar o campo de intervenção do serviço social com idosos no sistema de segurança social e no campo da ação social. Esta análise integrada num contexto de crise economia adota uma perspetiva crítica sobre os impatos da reconfiguração das políticas para as pessoas idosas e para o Serviço Social na atualidade.

1. Introduction

Older people have always been the subject of social work intervention, even before ageing became a challenge to society and to its different welfare states (Fernandes, Citation1997). This activity, associated with charity and welfare, was challenged to become part of the development of democratic states and the integration of human rights in social policies.

Even before there were social policies, the pioneers of social work (Mary Richmond and Jane Addams) developed innovative activities, for example, with immigrants and the older people in the Settlements and Hull Houses (Carvalho, Citation2012b). Social work pioneers started carrying out activities not based on charity or philanthropy but on human rights, even though these were formally established later in the 1948 Declaration of Human Rights and were subsequently integrated within the welfare states established after World War II.

In this paper, we assume that actions concerning older people form part of the identity of social work, involving support actions, social control and emancipation. The process of the modernisation of society (Giddens, Citation1995) saw the State intervening in the social sphere and giving rise to work with the older people.

With the increasing number of older people in these societies the ageing phenomenon is no longer a hidden reality and intervention with this age group, which used to be mainly assistance focused, is now a question of human rights, and also social and political rights. This has changed the way in which society, the state and public policy conceptualise this phenomenon and, consequently, social work intervention with older people.

Social work practitioners have mandates, in particular, care management responsibilities for social resources or services for the older people and increasing responsibilities for promoting older people's access to resources and services. Philipson (Citation2008) says that social work is now challenged to promote active ageing in particular, the impact of ageism—the ageing discrimination—to enhance the capacity of older people in society, and challenge the negative rights and also defend the positive rights.

With the current financial and economic crisis, ageing state policies, the positive, and the negative rights that developed during previous years are clearly threatened, which in turn is having a negative impact in social work intervention with this age group.

Portuguese society was also subject to this change, although this took a different path as public policies within a democratic framework only took place from the end of the 1970s, with the fall of the dictatorship and the establishment of a democratic government (Ferrera, Citation2005). According to the authors, from this date there was an unprecedented transformation of society and the construction of universally based public social policies with emphasis on implementing a Social Security system, the National Health Service and State Schooling.

The social workers were integrated within this process of the modernisation of society and the construction of the social security system, especially in the non-contributory subsystem and social welfare. Social workers re-established their activity in providing help in terms of rights (Carvalho, Citation2010) and contributed greatly to the set up and administration of social welfare regarding older people.

They contributed not only to policy administration of the public social security system, but also participated in the construction of social facilities at the community level, including Day and Social Centres, homes and residential homes, and home support services.Footnote1

However, in Portugal, the number of older people has been substantially increasing since the 1990s. In 2001, the senior citizen group, 65 and above, became a larger population group of 17.2%, compared with the younger age group, 14 and below at 15%. In 2011, the senior citizen category comprised 19.1% of the population, and the younger 14% (INE, Citation2001, Citation2011). This increase of population poses challenges to the social security system both in terms of pension reform and in the area of care.

The increase in the number of older people challenges the social policies and also the social work intervention in this area. In a time of economic and financial crisis this system is being challenged and social work is now intervening in the context of increasing difficulties with access to very limited services and resources for older people, who also have increased levels of need.

1.1. Aim of the article

This paper is part of an ongoing research entitled Social work, Ageing and Intervention with Older People Footnote2 and aims to analyse the field of social work intervention with older people in Portugal from a critical point of the view.

There are two main specific objectives: (1) analyse the national and local policies for the older people that inform social work intervention with older people in Portugal; (2) understand the typologies or approaches adopted in social work intervention within policies for older people in Portugal, taking into account the problems being addressed, the needs that are assessed and met and the main social work activities that are developed by practitioners.

1.2. Methodology

To achieve the goals, we adopt a critical analysis of the role of social work in care management and in the provision of services and resources for older people, in social care settings, in strict relation to national and international policies for the older people. Additionally, we analyse relevant documents in this area, of social policies at both central, local and community levels through an in-depth examination of the most relevant Portuguese legislation, such as The Social Security Act no. 7/Citation2007, The Local Authorities Act no. 1/Citation2011 and The Non Profit Organisations Act no. 119/Citation1983. We adopted a critical approach, on this legislation, on the research subject as opposed to a merely descriptive and functionalist analysis of the main research themes in order to problematise contemporary policies for older people and social work intervention in Portugal.

Here, we will first present our theoretical framework and the policies for older people and social work intervention with older people, analysing (1) the road map of the social security system and social care in Portugal and (2) the duties and responsibilities of social work intervention at the macro, meso and micro levels. Finally, we reflect on the impact of the economic crisis on the system as well as social work provision and conclude by leaving some thoughts for reflection and research.

2. Social work, ageing and policies for older people

Contemporary social work is conceptualised, both as an area of knowledge in the social and human sciences, and as a social practice that is developed in society through and within public and social policies, with relative autonomy and with a social responsibility mandate (Andrade, Citation2001; Carvalho et al., Citation1998).

Social work is influenced by how the states and the specific policies that each state develops in order to address the problems faced by human beings (Habermas, Citation1987) and that social work is influenced directly by social policies (Lorenz, Citation2005), especially with regards to the organisation, management and provision of care services to older people, when attempting to promote their social rights and human dignity (Payne, Citation2012).

Human rights and dignity are fundamental to social work intervention (Banks & Nőhr, Citation2008; Organização das Nações Unidas [ONU], Citation1999; Payne, Citation2011). Social work is a ‘globalised’ knowledge and intervenes with groups of people with ‘faces’ (Granja, Citation2007). Social work's main focus is on the most vulnerable groups of society, with the function of promoting their welfare (Payne, Citation2012).

In Portugal social work was institutionalised in 1935, with the creation of the first school, based on (religious) charity and philanthropy (secularism), and through the social medicine lobby. This training was called ‘Social Service’ and the professionals ‘Social Workers’.Footnote3 Its foundation and development took place during the dictatorial regime—from 1935 to 1974—where social action was not seen in terms of rights but rather as an assistance, which was essentially charitable in nature.

During this period, action took place within charities and state institutions of a repressive character—charitable alms-houses, for example. The first social worker joined the Lisbon Santa Casa da Misericórdia, one of the largest welfare NGOs in Portugal in the 1940s, and only later on were present in hospitals, particularly in the Portuguese Oncology Institute hospital. The director of this institute and other renowned doctors were significant forces in placing social workers in the health care system, and advocated an integrated and holistic view of the system.

The process of industrialisation started in the 1960s in Portugal, as well as war with the former colonies Angola, Mozambique and Guinea, leading to the setting up of public services and hospitals, as well as support services for the war-disabled, which included care for the old-people. As such, older people were often thought of as invalids and care was institutionalised and carried out in homes, called Asylums of charities.

Social work has been part of the modernisation of society and public policies since the 1970s. It is known that Portugal was under a dictatorial regime until 1974, where human and social rights were a mirage. Religious and professional groups were accountable for social protection of a rather small group of people. The Revolution of 1974 brought about civil, political and social rights. From this point on, health, education and social security services were put in place (Carvalho, Citation2012a). Social Work was integrated in this dynamic and gained a recognition it had never experienced before, with examples of this work being projects and solutions provided for children, the disabled and older people. For the latter, day centres, a home help service, homes and residences were established, as well as the first steps towards universal policies with regard to access to pensions and supplements.

During the last thirty years, in Portugal, the main policies on this phenomenon emphasise the active participation of individuals and organisations with regard to choice and access to health, and social services and resources (AAVV, Citation2002; Ministério da Solidariedade e da Segurança Social [MSSS], Citation2008; The national network of integrated continuous care Act. no. 101/Citation2006), like social facilities and long-term care services.

Despite this effort, the state of well-being in Portugal reveals characteristics of a conservative approach, as it protects some groups more than others (Esping-Andersen, Citation1990; Esping-Andersen & Palier, Citation2009) and, in addition, there are differences in access to general care services. Also, the role of families and catholic organisations is in line with the south of Europe model (Ferrera Maurizio, Hemerijck, & Rhodes, Citation2000; Silva, Citation2002).

In the last ten years, ageing policies have incorporated the principles of the paradigm of active ageingFootnote4 (ONU, Citation2002). This idea argues for an integrated approach based on three main pillars—protection, health and participation—considering the need to develop appropriate resources that meet the needs of older people (see, for example, ONU, Citation2002; Ribeiro & Paul, Citation2011). These were the golden years of social policies for older people, especially in investment in care and benefits for reduction of poverty (Ferrera, Citation2005).

The programme to implement this was the integrated support programme for the old-people as laid down in Joint Order No. 166, 1994, but carried out from 1997 onwards, with the purpose of creating new facilities and solutions involving health and the social area with quality standards. This programme was developed until 2006, when a long-term care network was set up.

These programmes developed under the health and social security systems allowed the strengthening of the premise ‘right to have care’. This does not depend on the financial power of families and reinforced the right to have benefits in contexts of deprivation, poverty, illness or incapacity (Esping-Andersen, Citation2000; Esping-Andersen & Palier, Citation2009; Ferrera, Citation2005)

In these days, in Portugal, social work with older people can be found in a vast array of settings and perform a wide range of interventions: in the statutory sector—in central government (Departments and state organisations) and in local government (local authorities); in the non-private sector (non-profit and voluntary organisations) and in the private sector (commercial for-profit organisations). In central government, social work operates within the Department of Social Security, by helping older people claiming welfare benefits and by managing residential and domiciliary care services for the ageing populationFootnote5 (Carvalho, Citation2012a).

Currently the number of senior citizens who have retirement pensions in Portugal is 3,112,256, which represents approximately 29.6% of the Portuguese population (MSSS, Citation2012). The total number of older people aged 65 who make use of social facilities, like home care, day care and residential care is 13.78% (MSSS, Citation2010). According to the MTSS (Portuguese Ministry of Solidarity and Social Security), in 2010, the use of these services include 90,570 older citizens receiving home care, representing 5.49% of the older citizens over 65 years old, 71,261 older citizens in homes and residential centres, representing 4.33% of the older citizens aged 65 years and over, and 62,472 older individuals in day and social centres, representing 3.96% of the older people over 65 years of age.

The study undertaken by Carvalho (Citation2012a), highlights the capacity of action of Portuguese social work care managers (their agency in sociological terms) when promoting the rights of the most vulnerable older people they work with and their innovative projects and solutions to meet older people's needs and abilities. Strategic action is a key feature in social work intervention with older people in a context of economic and social crisis (Dominelli, Citation2010; Garcia, Citation2009), especially when practitioners are providing support for those faced by poverty and social exclusion (Carvalho, Pauletti, & Rego, Citation2011). In the area of social work and within the network of protection for the older people in Portugal, there are different levels which will be further explored in this article: national (macro), local authority (meso) and community level (micro).

3. Policies on ageing and social work intervention

3.1. The road map of the social security system and social care in Portugal

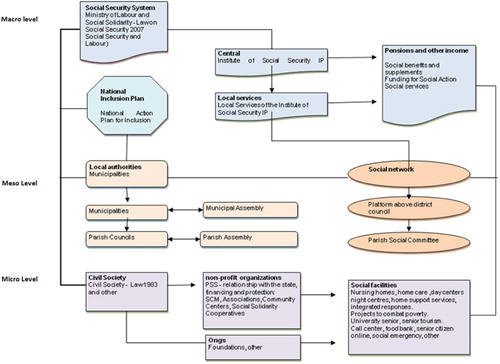

As can be seen from , at central-macro level, the social security system in Portugal is administered by the state. The legal framework on the social security system—Act no. 4/Citation2007—states in Article 2 that ‘all citizens are entitled to social security’. The basic principles underpinning the Portuguese social security system are: universality, equality, solidarity, equity, positive differentiation, subsidiarity, social inclusion, intergenerational cohesion, public accountability, complementarity, unicity, decentralisation, participation, effectiveness, protection of acquired rights, legal protection and, finally, the principle of information.

Portuguese Social Security System comprises the PrevidencialFootnote6 (Welfare) and the CidadaniaFootnote7 (Citizenship) subsystems. The Welfare Subsystem, which is a contributory scheme, covers most employees or similar workers and also the self-employed. Particularly, in the case of older people, it guarantees the right to a retirement pension on old age or invalidity and a supplementary support for dependants. The Citizenship Subsystem aims to guarantee essential citizenship rights, eradicate poverty and social exclusion and provide support in situations of demonstrable personal or family need that are not covered by the welfare subsystem. This subsystem is then divided into three subsystems: the Social Action System, the Solidarity System and the Family Protection System.

The Social Security System is administered, centrally, by the Instituto da Segurança Social, I.P. and, regionally, by its 18 District Social Security Centres (Centros Distritais da Segurança Social). In these centres, pensions under the Welfare Subsystem and all social action included in the Citizenship Subsystem are provided. Until 2010, the Instituto da Segurança Social, I.P. was also responsible for the coordination of the National Action Plan for Inclusion (NAP),Footnote8 which included a specific measure in poverty in the older population.

At local-meso level local authorities are responsible for the social protection of individuals and families. Under the Social Services Department, local authorities develop a variety of local programmes and projects to promote the health and active ageing of older people, to make public spaces more ‘older-person friendly’ as well as educational projects aimed at this age group on issues such as health, nutrition, physical exercise and quality of life. Furthermore, local authorities promote leisure activities and senior tourism in partnership with non-profit organisations and NGOs and provide transport and other resources to these local organisations, such as day centres, domiciliary care services, promoting an integrated social network and support to this age group. The most basic local government unit in Portugal is the parish (or freguesia), which is responsible for the local implementation of social inclusion programmes and services for older people, including day care facilities. Another important responsibility of the local authorities is the provision of social housing and home adaptations and improvements for older people.

Moreover, some local authorities in Portugal also develop integrated continuing care for older people in strict articulation with the central government. In addition, local authorities have also forged strong partnerships with the NHS, the voluntary sector and a range of other partners to ensure that older people's issues are reflected strategically in local plans and strategies. Some local authorities promote an active participation of older people in the decision-making processes through local forums.

Lastly, at a community-micro level, non-profit organisations and charities carry out the state's duties and responsibilities locally through official protocols with the central government. In addition, NGO and foundations also develop specific programmes and services for this age group, but with greater autonomy when compared to the organisations mentioned previously, as they do not have an official protocol with the state.

Therefore, all the above mentioned organisations are responsible for the majority of the services, resources and facilities that are provided to older people in Portugal representing, approximately, 68.1% of all the existing resources directed towards this age group (Carta Social, 2010, p. 4), the remaining percentage being 31.9% MSSS, Citation2010, p. 4). Some social facilities standout, such as residential care, domiciliary care services and day care centres, providing support to approximately 224,303 older people, distributed as follows: day care centres—62,472; residential care—71,261; and domiciliary care services—90,570 (MSSS, Citation2010). Despite the fact that these organisations have their own management structure, their financial dependence on the state means that they have to provide services according to the criteria and quality standards established by the central government.

3.2. Social work intervention: duties and responsibilities at macro, meso and micro level

Social work operates within the legal framework of the Portuguese Social Security System, considering the principles of human rights and the rights of older people to live with dignity. More specifically, as it can be observed from the following figure, social work intervenes within the Citizenship Subsystem, particularly in the solidarity and in the social action subsystem ().

Table 1. Macro level: social security and social work (citizenship subsystem).

Social work intervention does not take place at the previdencial (welfare) level taking into account that access to these benefits depends exclusively on the working contributions of older people. Currently, the retiring age in Portugal is 65, yet this is currently being reviewed.

Therefore, social work in Portugal operates within the citizenship system, more specifically in the solidarity subsystem and in the social action subsystem. This system aims to provide financial and social support to older people in order to promote their social inclusion, with reference to the principles of social cohesion. In the solidarity subsystem, social work intervention focuses on assessments of need and allocation of financial cash benefits such as social pensions, invalidity pensions or death pensions. In the social action subsystem, social work is oriented towards the assessment and development of care plans for older people in need and/or at risk, namely, integration of older people in long-term care facilities. Social work practitioners are responsible for the coordination of social and care services for this age group and for the development and implementation of community-based programmes and projects for this population. At state level, practitioners monitor, supervise and provide consultancy services to all the local non-profit organisations providing direct services to older people ().

Table 2. Meso level: local authorities and social work.

At meso level, social work is integrated in Portuguese local authorities. In this local context, social work performs a wide range of interventions. Whilst at council level, at social services departments, social work practitioners are mainly responsible for the development and coordination of programmes and projects to promote the quality of life of older people; at parish level, practitioners are more involved in the direct intervention with this age group and coordinate services and resources for this age group, such as day care centres. At these local services and resources, both preventative work and direct intervention with older people and their families is carried out by social work practitioners in collaboration with other professionals ().

Table 3. Micro level: Non profit organisations and social work.

Finally, at community-micro level, social work practitioners are employed by non-profit organisations. These organisations can have several configurations and may have broader or more restricted services, depending on their size and complexity. Santa Casa da Misericórdia, the oldest non-profit-making organisation operating across the country is a good example of a big-sized complex organisation. Non-profit organisations in Portugal develop a wide range of services for older people, such as residential care, domiciliary care and day care centres. Due to their participatory management principles and its multidisciplinary teams, they are in the forefront as far as promoting active ageing is concerned. Other non-profit-organisations, due to their smaller and less complex structures, tend to develop more standardised services with little practice innovation, directed mainly to the most socially and economically vulnerable older people. In these smaller organisations, sometimes the only specialised professional is the social work practitioner, who is at the same time responsible for the coordination and the direct intervention with older people and their families.

Therefore, Portuguese social work practitioners integrated in non-profit organisations can have a wide range of roles and responsibilities, such as coordination of services and resources, teamwork, direct intervention with service users and preventative work. They are also concerned with the quality of services that are provided to this age group, namely with older people's views about those services. Therefore, from time to time social workers carry out service satisfaction questionnaires to older people and their families.

4. Reflections on the situation caused by the impact of the economic crisis

The new global context has challenged the State to reconfigure the welfare model to a model now oriented towards expressive (shared) welfare for individualised and personalised socialisation, (socialising has become a voluntary action—produced in an accountable and autonomous manner; Lipovetsky, Citation2011; Soulet, Citation2012, p. 12).

Social policy no longer aims to protect individuals but rather encourages them to take and retake their place in society, that is, the idea of encouraging individuals to take their place in society through action from themselves (Giddens, Citation2007). Furthermore, for Soulet (Citation2012, pp. 12–13) policies are configured according to (1) risk, not in terms of danger to the organisation of society, but as a set of moral principles; (2) emancipation instead of compensatory policies; (3) limitation of support, aimed at those not earning, with social action being a means of encouraging usefulness (4) the idea of best practices towards investment in the development of human potential.

In Portugal, the policies for older people are moving towards the reconfiguration of social security systems, especially in streamlining access to benefits; promotion and funding by the State to both profitable and unprofitable Private Entities, to achieve care; individual responsibility—each individual has to predict the risks associated with old age and disease—through the application of Retirement Savings Plans and Health Insurance—in terms of social responsibility—responsibility for those who cannot insure themselves and demonstrate issues relating to poverty, dependence and isolation.

Measures from the Portuguese Government, the European Central Bank and the European Union concerning Portugal, have not only exacerbated the problems of the older people but also brought into question the area where social work operates. Some measures which have impacted in this area are: the cuts in pensions and Christmas and holiday benefits (this measure was declared illegal by the Portuguese Constitutional Court in April 2013); reduction in benefits for transportation and prescription medicine; streamlining access to services subject to a ‘means test’, increased user fees, control of medical exams and decreased investment in social and health solutions—long-term care—have brought public policies into questionFootnote9 (2011 Portuguese Government Programme).

Policies for older people have shown the following features: fragmentation resulting in a group of people with multiple needs in which situations of dependency and poverty can be identified where need already exists; they are carried out within a context of scarce and sometimes non-existent resources; access is controlled by management mechanisms focused on effectiveness and efficiency and the profitability/sustainability of systems (resources vs. necessity), thereby calling into question the operation of the social security system and social work as explained above.

The welfare state does not have the economic capacity to respond to the dysfunctions of the labour market, and therefore has removed itself from its duties as ‘future planner’ and adopted a moralising type of behaviour, under the pretext of the crisis and liquidation. It is also disseminating a discourse in which resources are not enough for all, and that the health and social security system are at a point of rupture. Furthermore, they have made cuts in retirement pensions, established taxes and regulations conditioning access to these and advocating the privatisation of such services, which are taken to be ‘unprofitable’. Private insurance services are flourishing as are social security systems from insurance companies and other major economic groups, which are proliferating under the guise of regulation. The role of ‘regulator’ means instilling public rules on private entities (Eberlein, Citation1999). However, the private services operate their own rules, the rules of profit.

In the current context of the shrinking state, regulatory rules are being changed. The rules included the so-called public/private partnerships contracts in the form of ‘concessions’, also known as commission contracts (Dominelli, Citation2010). It is like the ‘beach huts’ that are franchised to private entities during the summer season, with the State taking the stance of licensing goods and services that have hitherto been assumed to be public (see the proposal to privatise, and giving concessions to private entities, for the public broadcasting service, which is paid for by taxpayers/citizens through a fee—September 2012).

Privatising and licensing public goods and services have become the State's role. The public good has now become the private good, run by large multinationals, which generate high profits from these services. The services are now aimed at the ‘client’ for personal satisfaction and not for collective satisfaction. These neoliberal policies have deregulated employment, decreased the hourly rate of pay, and created insecurity and social risk. The rates of unemployment in Portugal increased from 7.6% in 2008 to 16.3% in 2014 (Pordata, Citation2013). Many families are emigrating to other European countries and also to other Portuguese speaking African countries (e.g. Angola, Mozambique), leaving the older people behind.

As far as older people are concerned, these neoliberal policies are increasingly visible, in access to and cuts in old age and disability pensions, and family welfare and social care and health. The right to have rights has become a mirage. We have returned to the idea that to have access to social rights a means test is necessary, not only for the individual but the family unit as well—social welfare. The family has become the main source of protection, given that the state has rejected this function. For instance, the budget in the healthcare system has decreased since 2010 and that made families spend more money in health related expenses (Pordata, Citation2013).

These days, professionals of social work see their work linked to managing along with scarce welfare budgets. Policy guidelines favour the selection of needs within a framework determining the complexity of social problems, and the rationalisation of resources.

In a context of global crisis and the financial and legitimacy crisis of the State it is not only investment in social policies that is called into question, but also the social work profession itself. If until 2006 the labour market for social workers lay in the public service, this is being changed. Currently, the little work that exists is poorly paid and in the non-profitable part of the private sector.

It is in this context that social work professionals are challenged to address the growing inequalities which undermine social cohesion and justice and to understand social policy in relation to social work.

5. To conclude

Social work has an implicit relationship with the process of the modernisation of society, linking the process of human rights development and public policy. Public policies, including state social security, local institutions and local care networks have contributed to making a hidden reality visible: social intervention among the older people and promoting the quality and well-being of this population group.

Ageing policies are very important in improving the position of the older people in society and promoting a fairer and more cohesive society. Social policies were constructed based on reducing the main principle causing inequality: namely that all people have the right to meet their needs, understood as fundamental rights, regardless of their social background and social status. Currently, policies are oriented towards individual and family responsibility. Thus human rights and social justice are being jeopardised.

The ageing population is one of the biggest challenges that societies face. The increase of older people in society and the present economic crisis is endangering the public system of social protection and hence the intervention of social services in this area. As we have shown, the State's responsibility regarding social action is being replaced by the action of charities.

The increase in older people challenged public policy, bringing with it challenges to the current model of social protection and the role of social work at social services. These challenges require another form of behaviour: oriented not only towards rights, but also to raise awareness of the conditions of inequality to which these groups are subjected. Only in this way might they become active and participatory stakeholders in the process of sustained development, protecting the people.

In the critical research area some issues may be raised. How to promote the welfare of the population and on the other hand maintain professional quality standards that allow social workers to practise their profession with dignity? How to fight for the protection and integration of older people in society? How to defend both ‘old’ and ‘new’ rights? How can social work defend the rights of the older people to be cared for and, at the same time, regulate access to services and care? What kind of regulation is required to protect and promote the rights of older people? How can social services defend the rights of older people? What form do intervention strategies take during time of crisis? These are the questions upon which policy-makers, social workers, need to reflect and which have to be debated in the near future.

Notes on contributor

Maria Irene Carvalho is a social worker and holds a BA degree (1995) and an MB degree (2001). She holds a Ph.D in social work from the ISCTE-IUL, Lisbon (2010). She teaches social work and coordinates a Master's degree in social gerontology at the ULHT University, Lisbon, Portugal. She is also an Integrated Researcher at the CAPP-ISCSP, Lisbon University, Portugal.

Notes

1. To do this, it was essential to integrate the private, religious and secular voluntary work institutions (Act no. 119/1983) within the public social security system (Act no. 28/1984). The system did not change substantively but was modernised over the years, in 2000 with Act no. 17, and later in 2002 with Act no. 32. Currently the system is regulated in accordance with Act No. 7/2007.

2. This research project aims to analyse, on the one hand, social work intervention with older people in Portugal, taking into account the contemporary policies at central and local level and, on the other hand, the dynamics of social work intervention and the practice of social workers in different settings and contexts.

3. In Portugal social workers are called ‘Social Assistants’ and social work is called ‘Social Service’. This profession began in 1935 and since this date they have been called ‘Social Assistants’. This name was influenced by French social work. In the 1960s, the profession was considered to require higher educational training and the relevant training was extended to four years with the awarding of a degree. Given this recognition the profession expanded its area of activity. Like all professions, it was in recent years, challenged to adapt to the Bologna training model and is currently located within universities offering first cycle BA degrees, second cycle Master MA degrees, and third cycle doctoral Ph.D. degrees. Most professionals have a BA or MA degree.

4. This new paradigm is complex and difficult to conceptualise and, as mentioned by Aceros, Callén, Cavalcante, and Domènech (Citation2013), it should take into account issues related to the concepts of ‘active citizenship’ or even ‘activism’.

5. In the health sector, social workers are responsible for planning an older person's care on leaving hospital by carrying out a community care assessment, are part of the team of professionals providing continuing health care services in the community and are involved in the implementation of health prevention programmes. These programmes, while not intended exclusively for this age group, tend to intervene mainly with older people (Unidade de Missão dos Cuidados Continuados Integrados [UMCCI], Citation2011). Social work practitioners are also employed by non-profit organisations which, in the Portuguese welfare state, are the main providers of services and resources to older people. At a local level, we would like to highlight the Social Network Programmes (Decreto-Lei no. 115/2006) in which gerontological plans are of great importance. Nowadays, social work can also be found in the private sector, namely in residential and domiciliary care services. Last, but not the least, social workers are also involved in preventative programmes against violence on the older people.

6. Previdencial means a prospective vision of the social risks of individuals integrated into the labour market. This subsystem integrates the social rights of people who are integrated into the production system and pay into social security. The rights are: right to retirement, unemployment, sickness, disability, and family allowance supplement for dependence. The financing of this system depends on the contributions of workers and employers.

7. Cidadania means that all taxpayers are funding this system, and the same is directed to vulnerable groups, who are out of the welfare system. This subsystem integrates the social rights of people who are not integrated into the system, i.e. they are not contributing. Social rights are subject to the assessment of need. So are integrated social pensions, the social insertion income, disability, The Solidarity Supplement for older people Act no. 232/Citation2005, and support for private institutions of social solidarity. The financing of this system depends on the state budget.

8. The 2008–2010 PNAI aimed to promote social inclusion and prevent situations of poverty and social exclusion in Portugal. The three fundamental priorities were:

Combating and reversing situations of persistent poverty, especially amongst children and older people;

Addressing disadvantages in education and training, preventing exclusion and contributing towards interrupting cycles of poverty and towards sustained and inclusive economic development;

Acting to overcome discrimination and empower specific groups, namely people with

Disabilities, immigrants and ethnic minorities.

9. These measures were embodied in the state budget for 2013. Of note was an increase in taxation at work and higher taxes for retired senior citizens.

References

- AA.VV. (2002). Portugal 1995–2000, Perspectivas da Evolução Social [Portugal 1995–2000, Perspectives on Social Evolution]. Lisboa: DEPP/MTS e Celta Editora.

- Aceros, J. C., Callén, B., Cavalcante, M. T. L., & Domènech, M. (2013). Participação das pessoas mais velhas: Construindo um quadro ético para teleassistência em Espanha, [Participation of older people: Building an ethical framework for telecare in Espanhal]. In Maria Irene Carvalho (coord), Serviço Social no envelhecimento [Social work in ageing]. Lisboa: Lidel, Practor.

- Andrade, M. (2001). Campo de intervenção do Serviço Social, autonomias e heteronomias do agir. [Field of social work intervention, autonomies and heteronomies of the acting]. Intervenção Social no. 23/24, 217–232.

- Banks, S., & Nőhr, K. (2008). Ética prática para as profissões do Trabalho Social [Ethical practice for the professions of social work]. Porto: Porto Editora.

- Carvalho, M. I. L. B. (2010). Serviço Social em Portugal: Percurso cruzado entre a assistência e os direitos [Social work in Portugal: Cross road between assistance and rights]. Revista Serviço Social & Saúde. UNICAMP Campinas, X, 147–164.

- Carvalho, M. I. L. B. (2012a). Envelhecimento e Cuidados Domiciliários em Instituições de Solidariedade Social [Ageing and home care in non profit organizations] (1st ed., Vol.no. 1). Lisboa: Coisas de Ler.

- Carvalho, M. I. L. B. (2012b). Contracorrentes em tempos de tempestades. O pensamento de Jane Addams e de Mary Richmond no Serviço Social [Crosscurrents in times of storms. The thought of Jane Addams and Mary Richmond in social work], Revista em Pauta, Revista da Faculdade de Serviço Social da Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro 10, 29, 157–169.

- Carvalho, M. I. L. B., Pauletti I., & Rego, R. (2011). Para a melhoria dos serviços sociais a idosos pobres [For the improvement of social services to the older people in poverty], Intervenção Social, no. 37, 109–124.

- Carvalho, M. I. L. B., Silva, R., Vicente, M. R., & Garcia, S. (1998). Serviço social e promoção da cidadania [Social work and citizenship] (pp. 271–300). Revista Intervenção Social. no. 14. Lisboa: ISSSL.

- Dominelli, L. (2010). Introducing social work, reprinted. London: Polity Press.

- Eberlein, B. (1999). L’État régulateur en Europe. Revue Française de Science Politique, 49, 196–230.

- Esping-Andersen, G. (1990). The three worlds of welfare capitalism. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Esping-Andersen, G. (2000). Um estado providência para o século xxi [A welfare state for the twenty-first century]. In M. J. Rodrigues (coord), Para uma europa da inovação e conhecimento [For a Europe of innovation and knowledge] (pp. 79–125). Oeiras: Celta Editora.

- Esping-Andersen, G., & Palier, B. (2009). Três Lições sobre o Estado-Providência [Three lessons on the welfare state]. Lisboa: Campo da Comunicação.

- Fernandes, A. A. (1997). Velhice e Sociedade – Demografia, Família e Políticas Sociais em Portugal [Ageing and society – demography, family and social policies in Portugal]. Oeiras: Celta Editora.

- Ferrera, M. (Ed.). (2005). Welfare state reform in Southern Europe, fighting poverty and social exclusion in Italy, Spain, Portugal and Greece. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Ferrera, M., Maurizio, F., Hemerijck, F., & Rhodes, A. (2000). O Futuro da Europa Social [The future of social Europe]. Oeiras: Celta.

- Garcia, F. G. (2009). Fundamentos del Trabajo Social [Basis of social work]. Madrid: Alianza Editorial.

- Giddens, A. (1995). As Consequências da Modernidade [The consequences of modernity]. Oeiras: Celta Editora.

- Giddens, A. (2007). A Europa na Era da globalização [Europe in the age of globalization]. Lisboa: Editorial Presença.

- Granja, B. (2007). Assistente Social Identidade e Saber [Social worker identity] (Dissertação de Doutoramento em Ciências do Serviço Social). Instituto Abel Salazar, UP.

- Habermas, J. (1987). Teoria de la acción comunicativa I – Racionalidad de la acción y racionalización social and Teoria de la acción comunicativa II – Crítica de la razón funcionalista [Communicative theory of acción I – rationality de la Acción Social y la rationalization and theory of communicative acción II]. Madrid: Taurus.

- INE. (2001). Census 2001. Portugal: Author.

- INE. (2011). Census 2011. Portugal: Author.

- Lipovetsky, G. (2011). Os tempos Hipermodernos [The hypermodern times]. Lisboa: Edições 70.

- The Local Authorities Act no. 1. (2011). Competency framework as well as the legal regime of operation, the bodies of municipalities and parishes. Lei Orgânica publicada em 30/11.

- Lorenz, W. (2005). Social work and a new social order, challenging neo-liberalism's erosion of solidarity. Social Work & Society, 3(1), 93–101. http://www.socwork.net/lorenz2005.pdf

- MSSS – Ministério da Solidariedade e da Segurança Social. (2010). Carta social rede de serviços e equipamentos [Letter dated social networking services and equipment]. Lisboa: Author.

- MSSS – Ministério da Solidariedade e da Segurança Social. (2012). Boletim Estatístico [Statistical bulletin], Fevereiro de 2012. Lisboa: Author.

- MTSS. (2008). Plano Nacional de Acção para a Inclusão, 2008–2010 [National action plan for inclusion]. Lisboa: Author.

- The national network of integrated continuous care Act. no. 101 (2006). Diário da República, I-Série A a 6 de Junho.

- The Non Profit Organizations Act no. 119 (1983). Diário da República, I-Série, no. 46 a 25 de Fevereiro.

- ONU – Organização das Nações Unidas. (1999). Direitos Humanos para o Serviço Social, Manual para Escolas [Human rights and social work]. Lisbon: ONU and e Departamento Editorial do ISSScoop.

- ONU – Organização das Nações Unidas. (2002). International plan of action on ageing 2002, in 2. Assembleia Mundial sobre o Envelhecimento. Madrid, 59.

- Payne, M. (2011). Humanistic social work. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Payne, M. (2012). The citizenship social work with older people. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Philipson, C. (2008). The Frailty of old age. In M. Davies (Ed.), Companion to social work. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Pordata. (2013). Base de dados Portugal contemporâneo [Database of contemporary Portugal]. Retrieved from www.pordata.pt, consultado em janeiro de 2013.

- Ribeiro, Ó., & Paúl, C. coord. (2011). Manual de envelhecimento activo [Guide for active ageing]. Lisboa: Lidel.

- Silva, P. A. (2002). O Modelo de Welfare da Europa do Sul – Reflexões Sobre a Utilidade do Conceito [The model of welfare in Southern Europe – reflections on the usefulness of concept]. Sociologia, Problemas e Práticas. no. 38, 25–59.

- The Social Security Act no. 28 (1984). Diário da República, no. 188, 540 I-Série a 14 de Agosto.

- The Social Security Act no. 17 (2000). Diário da República, I-Série A, no. 182 a 8 de Agosto.

- The Social Security Act no. 32 (2002). Diário da República, I Série-A, no. 294 a 20 de Dezembro.

- The Social Security Act no. 115 (2006). Diário da República, I Série, no. 114 publicado a 14 de junho.

- The Social Security Act no. 7 (2007). Diário da República, I Série, no. 11 a 16 de Janeiro.

- The Social Security System Act no. 4. (2007). General basis of the Social Security System. Diário da República, I-Série, no. 11 a 16 de Janeiro.

- The Solidarity Supplement for older people Act no. 232. (2005). Diário da República, Série-A, de 29 de Dezembro, de 2005.

- Soulet, M.-H. (2012). Prefácio à obra, Urgências e emergências do Serviço Social, fundamentos da profissão na contemporaneidade, de Maria Inês Amaro [Preface, emergency and emergency social work, fundamentals of the profession in contemporary] (pp. 11–18). Lisboa: Universidade Católica.

- Unidade de Missão dos Cuidados Continuados Integrados. (2011). Relatório de monitorização do desenvolvimento e da actividade da rede nacional de cuidados continuados integrados [Monitoring report of the development and activity of the national network of integrated continuous care]. Lisboa: Author.