ABSTRACT

In many countries, inspections are employed as a central instrument to promote good social work practice, but how inspections should operationally achieve this is not evident. By utilising data from guidelines, interviews and observations, the aim of the article is to analyse how the Swedish inspectorate operationalises care quality within the residential care services for children. Analytically, the inspectorate is regarded as an open system that is receptive to different ideas of how to operationalise care quality. The results show that: (a) the standards display a marked variation, change annually and are similar across all homes, (b) there is a limited link to good quality care as it is defined in empirical research, (c) there are several driving forces for care aspects to inspect and, in general, the distinct standards pertain to formal requirements, while how the care is provided is associated with more indistinct standards and (d) if there is no obvious malpractice in care provided, the inspections appear to have rather unclear formative effects. The results are inter alia discussed regarding whether inspections foster the idea that the ‘floor’ of the care is raised (i.e. securing a basic level of care) but not the ‘ceiling’ (i.e. maximising care).

ABSTRAKT

I många länder utgör statlig tillsyn ett centralt styrmedel för att förbättra det sociala arbetets praktik. Syftet med föreliggande artikel är att beskriva och analysera hur vårdkvalitet operationaliseras inom svensk institutionsvård för barn och unga. Det empiriska materialet består av tillsynsmyndighetens interna riktlinjer, intervjuer med inspektörer och observationer vid tillsynsbesök. Med utgångspunkt i institutionell organisationsteori betraktas tillsynsmyndigheten som ett öppet system som är mottagligt för olika idéer beträffande hur vårdkvalitet ska definieras. Resultaten visar att (a) de standarder som används uppvisar en stor variation, ändras årligen och är desamma för samtliga typer av institutioner, (b) standarderna har begränsad koppling till god vårdkvalitet så som det definieras inom empirisk forskning, (c) det finns flertalet motiv till val av granskningsområde och standarder för vårdens faktiska utförande är ofta oskarpa samt (d) om en institution inte avviker påtagligt från de standarder som används förefaller tillsynen ha tämligen oklara formativa effekter. Resultatet diskuteras bland annat utifrån om tillsynen bidrar till att säkra vårdens “golv” (dvs. säkerställa en miniminivå i relation till standarderna), men inte vårdens “tak” (dvs. optimera vårdens kvalitet).

Introduction

In many countries, external controls are increasingly employed as central instruments to create accountability and evaluate welfare services. In Sweden, residential care for children is a service in which this development has been salient. In 2010, a new inspection policy came into force, and the responsibility for this policy was transferred to the Inspectorate IVO (the Health and Social Care Inspectorate) established in 2013. Apart from reinforcing the child rights perspective, which entails that children, if they consent, should be interviewed during inspections (Pålsson, Citation2017), the most conspicuous change was the introduction of statutory inspections (Socialtjänstförordning [SoF], Citation2001:Citation937). During the first few years this meant that all residential homes were inspected twice a year, which in 2016 was reduced to once a year. The IVO consists of six regional offices and the overall aim of the inspections is to ‘contribute to a system of care that is safe and of good quality’ (IVO, Citation2015).

Inspections and other external control practices make up powerful principles for social organisation in contemporary society (Dahler-Larsen, Citation2012; Power, Citation1997). They rest on the supposition that by overseeing organisations, and holding them accountable for their performance, it is possible to promote good practice. However, the way inspections should be performed to obtain such goals in residential care warrants closer analysis. Standards used to detect good care quality in this regard are of major importance. Although there is a stronger consensus on definitions of inferior care (e.g. maltreatments), residential care is a service with a contested knowledge base. Hence, it may be difficult to establish valid standards for good care quality (cf. Lee & McMillen, Citation2008), but it should be stressed that research has identified care elements of considerable importance for service users (Boel-Studt & Tobia, Citation2016; Whittaker, del Valle, Holmes, & Gilligan, Citation2015). Further, since theoretical notions suggest difficulties in measuring complex services (Hasenfeld, Citation2010), it is relevant to gain insight into the trade-offs between constructing standards and organising inspections. In addition, there is an overall need for empirical validations on the impacts that inspection standards might have on residential practices.

By utilising data from guidelines, interviews with inspectors and observations during inspection visits, the aim of the article is to describe and analyse how the Swedish inspectorate operationalises care quality. In auditing a complex service like residential care, an inspectorate can be regarded as an open system (Scott, Citation2014), which means that they are receptive to external ideas of how to organise inspections and define care quality. The work of such organisations is an open process where auditors are recurrently influenced by institutional pressures to act in accordance with expectations. How care quality is made auditable is in turn considered formative for the organisation of the auditees (Power, Citation1997). The following research questions are addressed: What falls within (and outside) the operationalisation of care quality? Acknowledging that an inspectorate is an open system, which factors influence the process whereby the inspectorate operationalises and makes care quality auditable? Based on the above, how can you reason about the formative power of the audit system?

Background

Swedish residential care for children

As in many other countries, Swedish residential care is a group-based service aimed at children who, due to maltreatment or behavioural difficulties, have been removed from their home environment either voluntarily or with coercion. It is the municipal social services (n = 290) that are responsible for the placements and, following New Public Management reforms, the care is now often procured from private companies (Meagher, Lundström, Sallnäs, & Wiklund, Citation2016). In Sweden, residential care accommodates highly heterogenic practices: therapeutic residential homes, residential homes for unaccompanied minors and residential homes accommodating children and parents (Meagher et al., Citation2016). As in large parts of the world, Swedish residential care has been debated regarding its alleged deficits and there is evidence of historical failures to safeguard children in care (Sköld, Citation2013). Yet, residential care continues to hold a central status in social services provided for adolescents. The number of children placed in residential care has increased, above all as a consequence of a larger influx of unaccompanied minors. In November 2016, the residential field consisted of approximately 1300 residential homes of which 25 were secure units provided by the state (https://www.ivo.se/om-ivo/statistik/frekvenstillsyn-av-boende-for-barn-och-unga/).

In Sweden, the residential care content can vary considerably. Several professional groups operate in the field and there is a wide array of interventions based on different theoretical ideas (Wiklund, Citation2011). The care is poorly evaluated, but cohort studies have indicated that the long-term client outcomes in general are poor (Sallnäs & Vinnerljung, Citation2008). Internationally, efforts are being made to identify the active ingredients of the service and evidence-based practice (EBP). This has become more and more rhetorically institutionalised as the professional definition of care quality. However, it is disputed whether it is specific theoretical components in programmes or common elements/factors (e.g. therapeutic alliances, client engagement and care elements identified as important across residential programmes) that essentially bring about positive outcomes (James, Citation2017). Even though there is still a need for more evidence concerning what works in care (cf. James, Citation2017), empirical research stresses the importance of reducing disruptions in care, focusing on school and health support and providing the children with welfare resources (e.g. social support, material resources) whilst in care. Other important aspects involve nurturing an environment of strong therapeutic relationships between adolescents and adults, creating a supportive living group climate, collaborating with the family of origin and providing the children with good leaving-care services (Sallnäs, Wiklund, & Lagerlöf, Citation2012; Whittaker et al., Citation2015). However, the practical prerequisites for monitoring bodies to draw up standards regarding such care aspects remain uncertain.

Research on inspections

The research on the public monitoring of residential care is in general scarce and the organisation of audit activities varies between different countries. Audits can, for example hold organisations accountable for procedures (work execution) or performance (work outcome) (cf. Behn, Citation2001). Theoretically, it is argued that audits can be productive in improving social work provided that the standards correspond to crucial aspects of the practices (see e.g. care aspects above) (Munro, Citation2004; Tilbury, Citation2006). However, in social work, problems are often complex which means that it may be difficult to elaborate general standards that automatically raise care quality (Broadhurst et al., Citation2010; Hanberger, Nygren, & Andersson, Citation2018; Munro, Citation2011; Pålsson, Citation2017). Available empirical studies show that inspections of social work practices tend to measure service outputs, and not client outcomes (which arguably is a reasonable yardstick for evaluating care quality) (Hämberg & Sedelius, Citation2016; Hood, Grant, Jones, & Goldacre, Citation2016). Furthermore, inspection standards tend to be merged with quality discourses where the internal controls of organisations are placed in the front seat (Power, Citation1997). Here, the link between system quality on the one hand, and client work on the other, may be difficult to distinguish.

Inspections are carried out by inspectors who, as frontline bureaucrats (Lipsky, Citation2010), visit the care environments and through interviews, observations and the review of documents, gather evidence on the performance of the auditee. The inspections often unfold as processes where the assessments are made in interaction with the auditees and where methods to achieve compliance can involve advice as well as direct enforcement (Ayres & Braithwaite, Citation1992). The main purpose of the inspections in Sweden is to hold residential homes accountable for compliance with regulations. In Sweden, the inspectorate may formally impose requirements such as issuing fines and revoking licenses. But since the regulations are often lack detail, the legislator recognises that the inspections will partly take on an advisory role (Hämberg, Citation2012) and the policy of the IVO provides that the inspections may emphasise either supportive or controlling strategies (IVO, Citation2015). For the auditees, research indicates that becoming ‘auditable’ through documentation and oral accounts, demonstrating conformity may entail extensive work (Ek, Citation2012). Studies also indicate that practitioners may welcome inspections as a way of professionalising the care as it may lead to reflection, but also that standards may evoke tensions when meeting professional practice (Nordstoga & Stokken, Citation2011; Pålsson, Citation2017).

The inspectorate – an open system

To make the actions of the inspectorate intelligible, the analysis is inspired by institutional theory building (e.g. Power, Citation1997; Scott, Citation2014). From such a perspective, organisations like the IVO are viewed as open systems that are susceptible to institutional pressures and whose success hinges upon gaining legitimacy. For an organisation inspecting residential care, the institutional pressures are theoretically even more accentuated. Firstly, the care is aimed at children in vulnerable life situations and hence there are strong moral imperatives for the inspectorate to guarantee the decency of care. Secondly, residential care is complex and associated with disputes regarding the central care aspects. As an open system, such organisations are likely to adopt different ideas on how to organise the work and the care aspects to operationalise. The ideas can be more or less transitory and fad-like, but also more institutionalised, culturally taken-for-granted and codified into regulations. What they have in common is that the ideas often appear rational, appropriate and legitimate – although there is not always clear empirical evidence of their merits.

Methods and material

The study is inspired by ‘case study’ design (Yin, Citation2014) in using different data sources to investigate the inspections. The material consists of guidelines produced by the IVO, interviews with inspectors and field notes retrieved from observations made during inspection visits. The data was collected between October 2016 and April 2017. The study is part of a research project (Pålsson, Citation2017) on the monitoring system of Swedish out-of-home care and was approved by a regional ethical board.

Documents

Internal guidelines (N = 7) were collected from a contact person at the IVO. The guidelines displayed how the inspectorate had operationalised care quality on an annual basis and covered the years 2010–2017, i.e. the period during which the reinforced inspection policy has been in effect. There were no national guidelines in 2016 due to management deciding that it was up to each region to independently formulate standards that could be subsumed under the theme ‘security and safety’. The documents contained information on the care aspect to be inspected during the year in question, applicable regulations, and sometimes the motives behind inspecting the care aspect and how inspectors might reason when making assessments. The documents differed in detail and length (between 4 and 20 pages). By virtue of being documents, they do not represent the actual operational work, but can be defined as an ideal description of the audit procedure. However, as they were not intended for the general public they also brought up difficulties that the inspectors might face. While studying the documents I posed and recorded the answers to the following questions: How had care quality been operationalised? Did the document say why it was urgent to inspect the particular care aspect? Were there clear (or unclear) standards associated with the care aspect?

Interviews

Interviews have been conducted with inspectors (n = 11). The sampling was strategic (Yin, Citation2014) in that the inspectors who were selected were those with experience of operationalising care quality. Contact details of the inspectors with that experience were provided through the contact person. Nine of the respondents were or had been part of a group of inspectors responsible for proposing care aspects to inspect. The other two were inspectors in managerial positions who had a strategic position involving defining the overall focus of inspections and also making the final decision regarding the operationalisation proposed by the inspectors. The inspectors represented all regions, had worked with inspections for between two to fifteen years and their professional background was in social services. Inspectors do not necessarily have any particular training as regards inspections, but they are typically employed on professional merits. The reason for interviewing inspectors with different organisational positions was that they were presumed to represent different perspectives.

The interviews were conducted at the respective regional office of the inspectors. I had met some respondents previously when conducting other studies related to the research project, which supposedly facilitated contacts. Each interview lasted about 1–2 h. An interview protocol was used covering subjects like how the inspections were conducted, the reasons they gave for inspecting certain care aspects and their take on inspection of residential care based on their experience. The interviews allowed the inspectors to deviate from the themes when I judged that sufficient information had been obtained (cf. Yin, Citation2014). The interviews were recorded and transcribed.

Observations

The observation data come from field notes collected during inspection visits (N = 2). Residential homes were contacted through the trade organisation Svenska Vård (Swedish Care) which advocates the interests of private suppliers of social services (of which approximately 60 members are residential homes for children) (http://www.svenskavard.se/om-oss/). I commenced by providing the organisation with a description of the study, which they mediated to their members by e-mail. Five managers of residential homes contacted me to say that they were interested in participating. A prerequisite for participation was that the residential home was subject to an overt (and not covert) inspection visit during the time of the data collection. This was the case for two of the residential homes. The homes were situated in different parts of Sweden and belonged to different regional IVO offices. They were so-called therapeutic residential facilities providing treatment. The target group of one home was boys in the age group 14–17 with relational problems and externalising behaviour. The target group of the other home was girls in the age group 12–18 with psychosocial, neuropsychiatric and addiction problems as well as criminal behaviour.

The residential homes alerted me when they had obtained information on the pending inspection. The inspectors responsible for the inspections were informed in advance about my participation and approved it. I arrived at the residential homes well before the inspections to get to know the manager, staff and adolescents, and to obtain a sense of the residential environment. During the inspections, conventional ethnographic methods were used insofar as I participated as much as possible (cf. Hammersley & Atkinson, Citation2007). This meant observations were made before and upon the arrival of the inspectors when the inspectors interviewed the manager and staff together, and also some time after the inspectors had left. I continuously checked that all the people involved agreed to my participation. Whilst participating, I noted down my observations. My notes were developed into more detailed sections of text (in total 29 pages) soon after the visits.

The data from the guidelines were subject to content analysis (Hsieh & Shannon, Citation2005) in that I categorised the material inductively with reference to the type of care elements inspected. Interview and observation data were read repeatedly and coded in correspondence with the research questions, i.e. experiences of inspecting various care elements, factors influencing the selection of inspection standards and the formative effects of inspections. The analytical work was iterative in that themes were set in an interplay between data and the theoretical propositions that were selected underway (see theory section) and by comparing the empirical observations to quality aspects discussed in research. Regarding the limitations of the study, the sample of residential homes was rather small and how inspectors carry out the inspections may vary. However, the triangulation of methods had the merits of deepening and corroborating findings generated from different data sources (cf. Yin, Citation2014).

Results

The presentation of the results is divided into four themes that integrate empirical observations collected from the different data sources. I begin by describing the standards that have been employed by the inspectorate and in particular analyse the care elements that fall within the focus area of the inspectorate and the extent such elements are consistent with research knowledge. Next, I determine the rationale behind and possible implication of the fact that the indicators shift annually. Thereafter, I analyse the considerations underlying how the inspectorate selects what to audit and make suggestions on the formative power of the system. Lastly, I discuss the fact that the inspections primarily seem to be about ‘raising the floor’ (i.e. securing a basic level of care), but not ‘raising the ceiling’ (i.e. maximising care aspects that are supported by empirical evidence).

Operationalising residential care quality: in search of relevant care aspects

shows how the inspectorate has operationalised care quality since the inspection policy came into effect. The results display a marked variation of indicators that can broadly be subsumed under six domains of service outputs: staffing, internal controls/documented procedures, child participation, collaboration, premises and treatment. In addition, the inspectorate follows up previous failures to comply with requirements and, since 2013, has controlled compliance with the license if the care provider is private.

Table 1. The inspectorate’s operationalisation of residential care quality 2010–2017.

As the table shows, different aspects of staffing have been inspected recurrently (2010, 2012, 2015, and 2017). The monitoring has targeted the competence of the managers and staff, the staffing levels, that management requires extracts from police records before employment and that the children trust the staff. The documents, and interviews, highlight that these standards are rather imprecise (the requirements on managers and the requirement of an extract from police records prior to employment are, however, clearer). Consequently, it is considered difficult to evaluate, something which was apparent during one inspection I partook in, where the inspectors assessed the competence to be low but expressed difficulties concerning the imposition of requirements:

The inspector says to the manager that “as regards skills you’re at a low level, it’s important that you monitor skills.” She continues by saying “however we haven’t been able to link any deficiencies in the operations to the skills of the staff.” (RH2)

‘If we take the matter of comments and complaints from the social services, girls, parents, the IVO. How do you handle these? Do you have a special system?’ the inspector asks. ‘Yes, I think so’, the manager replies. The manager takes up the binder that has been lying there, opens it and starts leafing through it. There are forms that have been filled in. ‘Here I’ve collected all the comments. For instance, there was a girl who complained about the menu.’ (RH2)

Treatment (2012), namely the concrete support that is provided to the children in their daily lives, was inspected one year. This concerned the methods and whether the residential home helped the children with their behavioural development, schooling, and physical and mental health. Such factors may, for example, be determined by requesting how staff administer treatment on a daily basis. The guidance underlines that it is likely to be difficult to assess the information and set precise standards, since care content to a large extent addresses goals, for example, that interventions must be adapted to the individual of an adolescent (SoF 3:3). For instance, inspectors who worked at that time stress that they did not discriminate between different methods:

Because I know we used to do that, we did really extensive ones sometimes, and then there we were. We took in loads of material, lots of lists and what methods they used. We were drowning in it. Ok, now what? You have to be clear about why we do it. So over the years I think we’ve learnt that we have to have a use for any material we request. (Inspector 1)

Shifting standards: rationales and implications

As has been shown, a distinctive feature of the Swedish audit system is that the standards shift annually, which means that each year they focus on one or a couple of care aspects. From a frontline bureaucrat perspective (Lipsky, Citation2010) this can be interpreted as important to render the inspections more manageable. Overall, several measures are taken to make the inspections more efficient. For example, by preferring overt visits (and hence being sure to encounter the manager and that the staff has already begun to adjust to the preannounced standards). Sometimes, by collecting and reviewing documents in advance (and hence reducing the time devoted to such activities during the inspection visits). And finally, by sticking to the predetermined focus during the inspections. Organising the inspections in another manner is in general considered impracticable:

Firstly, you haven’t got the time, it isn’t feasible to gain an overview of everything. And you’re only visiting their reality for a short while and then you have to decide what to look at. (Inspector 2)

On the whole I think it has improved and become more professional since I started out. The quality of the supervision varied quite a lot and the extent too, and the focus as well. And you can see the current situation as a clear improvement. That we’re more professional, we work in a more uniform way across the country. It’s less subjective. (Manager 2)

The Management of the authority has decided that the regular supervision shall have a national focus every year so that the IVO is able to report the situation in the homes concerning a particular determined area at the national level.

Selecting care elements to inspect: an open system creating auditable standards

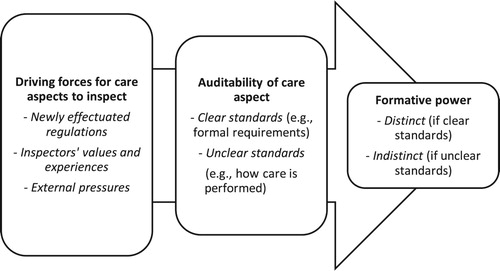

But what influences the process whereby the inspectorate reaches a decision about the care aspects to audit? . sketches an analytical scheme of the considerations underlying this process. As an organisation susceptible to ideas of what to audit, the first box shows that the impetus originates from several sources (newly effectuated regulations, inspectors’ values and experiences, and external pressures). The second box indicates that different care aspects are considered auditable to a varying extent and hence, result in either clearer or less clear standards. The third box reveals that the precision of the standards theoretically affect the formative power of the inspections, that is, the force with which the residential practices will be shaped.

Firstly, emerging as a self-evident source for standards are newly effectuated regulations. During the period studied, regulations on quality systems and reports on complaints and maltreatment were introduced by the legislator and subsequently incorporated into the annual audits. Here, the purpose is to check that new regulations are implemented. During the year studied, the inspectorate audited abidance by a new more specific regulation on suitability assessments conducted prior to the enrolment of new children.

Enrollment and suitability assessments are obvious areas since it is the amendment to the legislation that’s coming into effect as from 1 November, and it has to be documented. It’s important to pay closer attention to the children’s needs and their age. The mix of the children so that it’s safe and secure. So that was pretty obvious. (Inspector 3)

In the current system, we normally, the year before or well, in the run-up to the year we are choosing a theme for, we look at what we’ve seen out there, what deficiencies we have seen, our findings where we feel that here there may be risks, based on what the situation is like at that particular point in time. So we try to collect observations of that kind from the different departments. (Manager 2)

And then there’s been the media and that also sometimes has an impact// … //Well a couple of years ago there was the matter of … At the secure units, that you weren’t allowed to go out. It was a few summers ago, on the program Kaliber (Swedish radio program, author’s note) or something, they did something on that. Then in the middle of the summer we suddenly also had to scrutinise that (Inspector 5).

And then you have to balance it against what’s possible// … //There you use your experience a lot. What can we investigate based on the methods we have. Based on the current legislation, what can we actually demand and so on. // … //What I would wish for would be to look at whether the kids get the help they need, are they better off after their placement.// … // But that isn’t doable, is it? (Manager 2)

Securing the floor but not raising the ceiling?

One facet of the inspection visits was that the inspectors stuck to the delimited focus of inspections and that the inspections were primarily geared towards detecting obvious deviations from standards. This is consistent with what was discussed during the interviews where the inspectors’ view was that they could most easily intervene where the care was evidently inferior. It is also compatible with the fact that there are in general few clear standards relating to how the work is executed, but that the standards target the general management of the residential homes. In practice, the inspection visits unfolded as processes in which the residential homes were encouraged to demonstrate awareness and self-control regarding the care aspect inspected and sometimes could gain some advice and tips. Hence, inspections are often discussion-based and prompt the auditees to account for their strategies and reflections. Prior studies show that this may lead to pause-for-thought amongst auditees which can be constructive, but at the same time, it makes it difficult to conclude what the inspections actually entail for client work (Pålsson, Citation2016). In other words, providers are left with considerable discretion in their work. This rather non-intrusive character of inspections, when a residential home is considered as functioning well, was evident during one of the inspections I participated in:

Then the inspector moves on to the next subject. She says that it’s about suitability assessments// … //She picks up the papers with the three latest enrollment decisions that the home sent to the inspectors in advance. The inspector says that ‘there’s nothing to comment particularly’, that the home has obtained the relevant information for enrollment and checked to see that the adolescent in question fits in with the group at the home. (RH1)

Conclusions and discussion

In many countries, external controls have acquired an important status as central instruments to create accountability and promote good practice in social work. However, how audit systems reach conclusions on which care aspects to control and what the inspections operationally accomplish, is often more opaque. In Sweden, a new inspection policy concerning residential care for children was introduced in 2010, the most conspicuous change being the introduction of statutory annual inspections. Acknowledging the inspectorate as an open system, this article has analysed how the Swedish inspectorate has operationalised care quality, the rationales behind the fluctuating focus of inspections, the factors that influence how care quality is operationalised and has made suggestions on the formative power of the system. By mixing guidelines, interviews and observations the study has a substantiated base, but the qualitative and explorative design also calls for some caution.

In short, the main findings are the following: The standards employed display a substantial variation and the link between standards and findings from research are wanting. The standards used are similar across all residential homes, which appear to emanate from an urge to form a uniform control apparatus. Standards are elaborated in an open process and possible auditability tends to confine what is selected. In practice, the inspections appear rather non-intrusive as the strong formative power targets formal requirements, whilst how client work is performed is associated with less distinct standards.

With these findings as a springboard, three overall conclusions and implications can be expounded. Firstly, the shifting standards can be viewed as a sign of an elastic and open system in which the definitions of care quality are far from fixed. A benevolent interpretation is that this demonstrates an adaptable system which takes into account that residential care is a service where a myriad of factors may be of importance. However, the variation of standards and the various influences also give the impression of a system lacking systematics. Residential care is a service where the working conditions (enrolled children, employed staff etc.) are likely to change rapidly which is why it is relevant to ask whether the fact that a care aspect, once it has been audited, really makes the residential field ‘quality assured’ in this respect. In addition, the fact that the criteria are equal for all residential homes, irrespective of, for example, target group, also means that it is disputable whether the inspections consider the specific logic and operations of different categories of residential homes. In this respect, organisational ideas such as uniformity appear to override other concerns.

Secondly, results show that care aspects, which have been stressed as important in research, are extensively outside the focus of inspections. In other words, auditees are in general accountable for procedures not emphasised in research. Instead, standards are formed by ideas where the aim is to reduce malpractice. Since residential care is a service where protection is fundamental and where there is historical evidence concerning failures to safeguard children in care, this priority is understandable. Furthermore, the benchmark against which the inspectorate is ultimately evaluated, through its institutional setting, is perhaps whether it manages to secure a safe residential environment. However, it also means that it is unlikely that the inspections contribute to maximising the care quality. In one sense, it is not surprising that treatment methods are not reviewed or discriminated between to any great extent, since evidence supporting the merits of specific methods is meagre (cf. James, Citation2017). Further, common factors such as the quality of the relationship between children and staff appears – as have been shown in the article – notoriously difficult to audit and set standards on (cf. Hasenfeld, Citation2010). However, there are care aspects in relation to which residential homes could increasingly be held accountable for, for example, the work done to prevent disruptions, the provision of school support, the planning of leaving-care services and the quality of the group climate etc. (cf. Whittaker et al., Citation2015).

Thirdly, the fact that the audit system, to a high degree, lacks distinct standards regarding how the work with the children is performed and in practice appear rather discussion-based, means that the system evades the possible downside of inspections, such as ‘box-ticking’ and excessive focus on rule compliance etc. (cf. Munro, Citation2011). Hence, the current organisation may be in tune with the complex and situational character of residential care where precise standards may not be theoretically suitable. Yet, you might wonder whether a consequence of not having distinct standards is perhaps less of an impact when care does not deviate very much from the standards. The current audit system gives residential homes considerable autonomy to decide on the actual care content, which means that the state misses the opportunity to have a profound impact. A tentative but legitimate question that can be raised is what the inspections actually achieve at a general level beyond triggering staff at residential homes to reflect on their practices in relation to the care aspect audited at a particular point in time. Notwithstanding the advantages of this reflective output of inspections, the study suggests that inspections of residential care in Sweden are not the forceful quality control that they are often presented as in policy terms.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes on contributor

David Pålsson is researcher and lecturer in Social Work at Stockholm University, Sweden. He recently defended his PhD dissertation which analyzes the audit system of residential care for children in Sweden.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ayres, I., & Braithwaite, J. (1992). Responsive regulation. Transcending the deregulation debate. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Behn, R. D. (2001). Rethinking democratic accountability. Washington, DC: Brookings inst. Press.

- Boel-Studt, S. M., & Tobia, L. (2016). A review of trends, research, and recommendations for strengthening the evidence-base and quality of residential group care. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth, 33(1), 13–35. doi: 10.1080/0886571X.2016.1175995

- Broadhurst, K., Wastell, D., White, S., Hall, C., Peckover, S., Thompson, K., … Davey, D. (2010). Performing ‘initial assessment’: Identifying the latent conditions for error at the front-door of local authority childrens service. British Journal of Social Work, 20(2), 1–19.

- Dahler-Larsen, P. (2012). The evaluation society. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Ek, E. (2012). De granskade. Om hur offentliga verksamheter görs granskningsbara [ The auditees. On how public organisations are made auditable]. Göteborg: Göteborgs universitet.

- Hämberg, E. (2012). Supervision as control system: The design of supervision as a regulatory instrument in the social services sector in Sweden. Scandinavian Journal of Public Administration, 17(3), 45–63.

- Hämberg, E., & Sedelius, T. (2016). Inspection of social services in Sweden: A comparative analysis of the use and adjustment of standards. Nordic Social Work Research, 6(2), 138–151. doi: 10.1080/2156857X.2016.1156015

- Hammersley, M., & Atkinson, P. (2007). Ethnography. Principles in practice. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Hanberger, A., Nygren, L., & Andersson, K. (2018). Can state supervision improve eldercare? An analysis of the soundness of the Swedish supervision model. The British Journal of Social Work, 48(2), 371–389.

- Hasenfeld, Y. (2010). Human services as complex organisations. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications.

- Hood, R., Grant, R., Jones, R., & Goldacre, A. (2016). A study of performance indicators and ofsted ratings in English child protection services. Children and Youth Services Review, 67, 50–56. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.05.022

- Hsieh, H. F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288.

- IVO. (2015). Inspektionen för vård och omsorgs (IVO:s) policy för tillsyn [Supervision policy of the IVO]. Retrieved from http://www.ivo.se/globalassets/dokument/om-ivo/konferens/2015-jan-jun/tillsynspolicy.pdf

- James. S. (2017). Implementing evidence-based practice in residential care – how far have we come? Residential Treatment for Children & Youth, 34(2), 155–175.

- Lee, R. B., & McMillen, C. (2008). Measuring quality in residential treatment for children and youth. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth, 24(1–2), 1–17. doi: 10.1080/08865710802146622

- Lipsky, M. (2010). Street-level bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the individual in public services. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Meagher, G., Lundström, T., Sallnäs, M., & Wiklund, S. (2016). Big business in a thin market: Understanding the privatization of residential care for children and youth in sweden. Social Policy & Administration, 50(7), 805–823. doi: 10.1111/spol.12172

- Munro, E. (2004). The impact of audit on social work practice. British Journal of Social Work, 34, 1075–1095. doi: 10.1093/bjsw/bch130

- Munro, E. (2011). The munro review of child protection: Final report. A child-centered system. London: The Stationary Office.

- Nordstoga, S., & Stokken, A. (2011). Professional work in the squeeze: Experiences from a new control regime in residential care for children and youth in Norway. Journal of Comparative Social Work, 2, 1–18.

- Pålsson, D. (2017). Conditioned agency? The role of children in the audit of residential care for children in Sweden. Child & Family Social Work, 22, 33–42.

- Pålsson, D. (2016). Adjusting to standards: Reflections from ‘auditees’ at residential homes for children in Sweden. Nordic Social Work Research, 6(3), 222–233.

- Power, M. (1997). The audit society: Rituals of verifications? Oxford: Oxford university press.

- Sallnäs, M., & Vinnerljung, B. (2008). Into adulthood: A follow-up study of 718 young people who were placed in out-of-home care during their teens. Child & Family Social Work, 13, 144–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2206.2007.00527.x

- Sallnäs, M., Wiklund, S., & Lagerlöf, H. (2012). Welfare resources among children in care. European Journal of Social Work, 15 (4), 467–483. doi: 10.1080/13691457.2012.702313

- Scott, R. W. (2014). Institutions and organisations. Ideas, interests and identities. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

- Socialtjänstförordning (SoF). (2001:937). [Social Services Regulation].

- Sköld, J. (2013). Historical abuse – A contemporary issue: Compiling inquiries into abuse and neglect of children in out-of-home care worldwide. Journal of Scandinavian Studies in Criminology and Crime Prevention, 14(1), 5–23. doi: 10.1080/14043858.2013.771907

- Tilbury, C. (2006). The regulation of out-of-home care. British Journal of Social Work, 37(2), 209–224. doi: 10.1093/bjsw/bcl012

- Whittaker, J. K., del Valle, J. F., Holmes, L., & Gilligan, R. (red.). (2015). Therapeutic residential care for children and youth: Developing evidence-based international practice. London: Jessica Kingsley Publisher.

- Wiklund, S. (2011). Individ- och familjeomsorgens välfärdstjänster [Welfare services in personal social services]. In L. Hartman (Ed.), Konkurrensens konsekvenser [ The consequences of competition] (pp. 111–145). Stockholm: SNS.

- Yin, R. K. (2014). Case study research. Design and methods. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.