ABSTRACT

Mental health service user movements have historically to a large extent employed collective forms of mobilisation, where people with service user experience have joined in formal organisations or informal groups. Currently, expressions of service user engagement are changing, and we can now observe the growth of more individualised expressions, often enacted online. This article introduces the concept ‘service user entrepreneur’ (SUE), that relates to this development. SUEs are individuals with service user experience who have made a career of their engagement in mental health issues. Based on their individual narratives of mental ill-health, SUEs often express themselves in participatory media, hold lectures and write books on the subject. The aim of this article is to examine how SUEs in their communication establish authority. Applying case study methodology, we follow four Swedish SUEs involved in mental health issues and analyse their communication primarily in digital arenas. Intimate personal narratives, mobilisation of collectives and institutional perspectives constitute authority sources for SUEs. Balancing individual and collective narratives as well as maintaining a desirable level of vulnerability is a continuous effort. How SUEs manage these issues is further discussed.

SAMMANFATTNING

Brukarrörelser på området psykisk ohälsa har till stor del använt sig av kollektiva former för mobilisering, där personer med brukarerfarenhet slutit sig samman i formella organisationer eller i informella grupper. På senare år har brukarengagemanget genomgått förändringar och vi kan idag se framväxten av mer individualiserade former som ofta tar sig uttryck online. Denna artikel introducerar i det sammanhanget begreppet ‘brukarentreprenör’. Brukarentreprenörer är individer med brukarerfarenhet som har skapat en karriär genom sitt engagemang i frågor som rör psykisk ohälsa. Med grund i sina individuella narrativ om psykisk ohälsa framträder brukarentreprenörer ofta i sociala medier, håller föreläsningar och skriver böcker om ämnet. Syftet med denna artikel är att undersöka hur brukarentreprenörer i sin kommunikation etablerar auktoritet. Med fallstudie som metodologisk ansats följer vi fyra svenska brukarentreprenörer som ägnar sig åt frågor som rör psykisk ohälsa och analyserar deras kommunikation, primärt på digitala arenor. Intima personliga narrativ, mobilisering av kollektiv och institutionella perspektiv är centrala källor till auktoritet för brukarentreprenörer. Att balansera individuella och kollektiva narrativ, men även att upprätthålla en önskvärd grad av sårbarhet, utgör en kontinuerlig strävan.

Introduction

With democratic principles of participation and representativeness as a foundation for authority, mental health service user movements have historically to a large extent employed collective forms of mobilisation. Forming groups and organisations, people with service user experience have joined together for mutual support and to advocate for political change. The Swedish service user movement has been dominated by service user organisations with close connections to the government (Markström, Citation2003; Markström & Karlsson, Citation2013). These organisations today occupy a central role in the process of democratising and developing the quality of human service organisations. However, wider patterns of individualisation of politics are in recent years visible in the area. These tendencies have for instance been reflected in government funded projects aimed at hiring individual service users as coordinators of public service user influence (SOU, Citation2006:Citation100), or training individual service users for anti-stigma work (Andersson, Citation2014). Participatory media has further created new arenas for service user engagement, which often takes more individualised forms (Bennett & Segerberg, Citation2013; Johansson, Citation2015a; Myndigheten för vårdanalys, Citation2015).

Johansson (Citation2013, Citation2015a) has previously examined how digital arenas are employed by individual service users in pursuing politics, but mainly focused on small clusters of blogs with relatively limited audiences. In this study, we explore an example that reaches a larger audience, namely what we call service user entrepreneurs (SUEs). We define SUEs as individuals with service user experience who have established companies and made a career of their engagement in mental health issues. These individuals generally self-define as social entrepreneurs, running companies with the dual goals of moneymaking and a social mission (Clark, Citation2009; Light, Citation2006). Based on their individual narratives of mental ill-health, SUEs often express themselves in participatory media, hold lectures and write books on the subject. The authority of SUEs is related to their having followers on participatory media and co-production characterises the relationship between SUEs and their audiences. Resembling ‘celebrity or corporate’ service users (Lakeman, Cook, McGowan, & Walsh, Citation2007), these are charismatic and articulate individuals, typically not affiliated with a service user organisation. The emergence of SUEs in Sweden is connected to the more prominent position in other national contexts of people who have, alongside collective movements, established platforms for themselves through self-employment, businesses and foundations. Previous research has, however, mainly focused on entrepreneurial endeavours such as social cooperatives and consumer-run services (eg. Krupa, Citation1998; Mandiberg, Citation2016; Trainor & Tremblay, Citation1992) where individual founders, in comparison with SUEs, hold a less central position. Furthermore, the accessibility and reach of participatory media potentially contributes to a growth in both number and influence of more individualised expressions.

The foundation of the activities of SUEs is their individual narratives and experiential knowledge of mental ill-health. A revalorisation of experiential knowledge and an increased awareness of lay peoples’ greater access to certain ways of knowing is evident in the mental health area (Noorani, Citation2013). The authority of experiential knowledge is related to tendencies of service user professionalisation and a growing demand for service user involvement in health care systems (Dawney, Citation2013; Noorani, Citation2013). The emergence of SUEs can also be linked to the so-called ‘narrative turn’ in society with increased attention to sharing narratives of individual experience (Goldstein, Citation2015). A shift towards personal content with the sender in focus is visible both in traditional and participatory media. Celebrities and creative artist (Beck, Aubuchon, McKenna, Ruhl, & Simmons, Citation2014; Lerner, Citation2006) but also practitioners (Davidson, Bellamy, Guy, & Miller, Citation2012; Jones & Pietila, Citation2018) and researchers (Faulkner, Citation2017; Landry, Citation2017) are publicly disclosing experiences of mental ill-health and claim authority from their dual positioning.

In relation to more collective expressions of service user engagements, SUEs require alternative sources of authority in order to legitimise their platform and influence. To provide insights into this process, our aim is to examine how SUEs in their communication establish authority. Authority in social interaction is a specific form of power enactment that depends on being viewed as justifiable and resting on a legitimate source (Haugaard, Citation2018; Weber, Citation1922/Citation1978). Through this, authority is relational and ‘bestowed through a listening which is not coerced’ (Dawney, Citation2013, p. 36). A central concern of authoritative relations regards whose knowledge is defined as legitimate. Experiential knowledge represents a type of knowledge that is increasingly often employed for legitimacy claims (Dawney, Citation2013). Dawney (Citation2013, p. 30) discusses the emergence of ‘figures of experiential authority’, who are defined by the public as experts through their lived experience. Our ambition is to examine how SUEs, as examples of such figures, in their communication establish authority and legitimise their position. Authority is further vital for understanding online communication and networks, that require authority for defining what information and sources are relevant, trustworthy and reliable (O’Neil, Citation2009).

Methods

In order to examine the sources of authority drawn upon by SUEs, we have applied case study methodology (Yin, Citation2007). The study was carried out within a Swedish context. An early and well established service user movement (Markström & Karlsson, Citation2013) and comparatively widespread internet use (Findahl, Citation2014) characterises the national setting for these SUEs. We purposely sampled four entrepreneurs, whose activities we have studied: Aldrigensam (Neveralone); Sinnessjukt (Insanely); Underbara ADHD (Wonderful ADHD); and Pillerpodden (The Pill Podcast). Our inclusion criteria were based on our definition of SUEs as individuals who (1) have founded a company, (2) share their individual narratives of mental health in the company and (3) have the aim of reaching a public audience. From individuals matching these criteria, we selected four SUEs representing somewhat different approaches to display diversity with regard to organisational form, mediums of communication and degrees of interactivity. However, these entrepreneurs’ communication and activities also share important similarities, and thereby illustrate both variation and commonality within this social phenomenon.

The over-arching research project of this study was developed in collaboration with a research panel consisting of members with lived experience. At a later stage this research panel also examined and commented on the design of the individual studies. Several researchers have discussed the benefits of including processes of service user involvement in research on issues concerning these groups (e.g. Beresford, Citation2013; Rose, Citation2014; Videmsek & Fox, Citation2018). The arenas of communication employed by the entrepreneur in question have guided our data collection. We have analysed websites, posts on blogs, Facebook and Instagram, but also debate articles, books and podcasts. Since the ambition of SUEs is to reach a public audience, their communication should be understood as public content. Replies of and comments by audiences have, however, been aggregated in order to avoid identification of individual users. The study received approval by the regional ethical review board in Umeå: 2016/121-31. provides an overview of the arenas for data collection and the included material.

Table 1. Overview of the SUEs and arenas for data collection included.

Initially, we analysed the material with an inductive approach, searching for recurrent topics and communicative processes. Since the SUEs striving to establish authority was central to the outcome of our initial analyses, we returned to data with a focus on articulations of authority as well as instances of challenged authority. The different SUEs are described as separate cases below and are thereafter compared for similarities and differences in relation to the sources of authority that are drawn upon.

Neveralone

Neveralone is a social enterprise described as an ‘information project that spreads knowledge and breaks the silence regarding the taboo subject of mental ill-health among young adults’. Through the project, the founder shares his life story and experience of mental ill-health but also his journey towards recovery. The organisational form is a stock company, and the founder describes Neveralone as the largest mental health information project in Sweden with 100,000 followers on Facebook. Facebook is the main arena for communication of the project, but Neveralone also has a website and an Instagram account. Furthermore, the founder has written two books and holds lectures on the subject.

The Pill Podcast

The founders of the company The Pill Podcast describe their work as being related to three different areas: education, communication and opinion forming. Their main arenas for communication are their podcast and blog. They also provide mental health services through organising support groups for students, hold lectures and have arranged and performed shows for the stage. As with Neveralone, the founders’ own experiences of mental ill-health are central to the company’s communication. The Pill Podcast’s activities aim to break down taboos, create a broader and normalised understanding of mental ill-health, prevent suicide and support mental health among youth.

Wonderful ADHD

Wonderful ADHD started as a blog that turned into a digital platform. The main focus areas of Wonderful ADHD are described as being education, information, inspiration and opinion-forming in order to reduce preconceptions, taboo and to increase knowledge of ADHD. Wonderful ADHD provides educational services such as lectures, contract teaching and online courses for teachers and school personnel. The founder has also performed a show for the stage and written a book based on his own experiences of living with neuropsychiatric disabilities.

Insanely

Insanely is, according to the company’s communication, the first podcast on the subject of mental health in Sweden, currently having over 100,000 downloads each month. During a period when the founder was struggling with mental ill-health, he set up a website in order to share information on mental health issues. He later created a blog and has written several books, for instance related to depression and anxiety disorders. In his books and the podcast Insanely, the founder shares his individual experience of mental ill-health mainly as a backdrop, but often includes mental health professionals and frequently references research. The communication of Insanely has a fact-oriented approach, with the ambition of spreading information and educating.

Empirical presentation and analysis

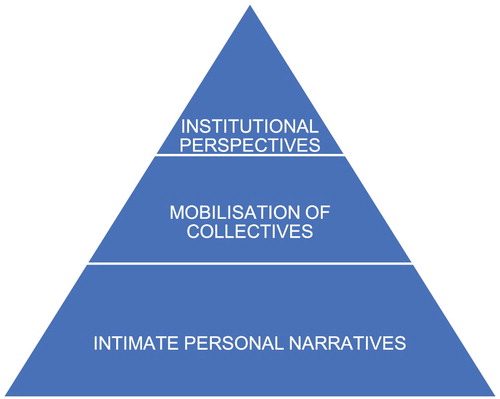

The SUEs included in our study mainly draw upon three sources of authority in their communication. The personal narrative of mental ill-health is the foundation for activities. It is constructed as a source of authority through the entrepreneurs’ experiential knowledge, and also by grounding authenticity. By constructing intimate collectives through communication with their audiences, these entrepreneurs further build authority by forming networks around their causes. Institutional perspectives, the third source of authority, are drawn upon through collaboration with mental health professionals and by presenting research-based perspectives. illustrates the different sources drawn upon in SUEs’ construction of authority. How these different sources of authority are articulated, related and challenged will be discussed in the following section.

Authority through intimate personal narratives

The communication of all four SUEs focuses on their individual narratives of mental ill-health. These personal accounts provide authority by laying the foundation for authenticity and an affective bond with audiences. They are also sources of experiential authority, where the SUEs are constructed as experts through their lived experience of mental ill-health.

The SUEs frequently reference their founders’ experiential knowledge of mental ill-health. Wonderful ADHD describe the founder’s lectures as based on his individual experience: ‘He himself has the diagnosis and is an appreciated lecturer – exactly through his ability to proceed from his own experiences.’ In a debate article, The Pill Podcast also constructs authority by highlighting their lived experience of mental ill-health:

We who are writing are neither researchers nor psychologists. We are witnesses of what it is like to be young with mental ill-health in Sweden today and founders of a small company called The Pill Podcast, which started as a podcast but which now, three months later, has become a full-time job, even though we lack radio education and university merits. But we possess an experiential perspective, and we have the courage to challenge the norm and talk about what is not beautiful, driven by the idea of change and knowing that it is possible since we can see it reflected in ourselves […]

It’s a beautiful autumn evening at the end of September 2013, and my body lies on a cold stretcher inside the intense care unit at the county hospital […]. My parents have just received the call from the doctor, the call no one wants to receive, the call where the doctor tells them that their son will pass away. Some hours earlier I had a massive panic attack and had incredibly strong thoughts of suicide. To get rid of the anxiety I overdosed on pain killers and sedatives. I wanted to find peace and leave this mortal life. My route out of suffering was to die.

I can’t believe that the body can react so strongly to loneliness. Not being alone, just the FEELING of it. Logging the summer’s first massive panic attack. How do you deal with loneliness?’

Personal narratives are not only limited to experiences of mental ill-health. The SUEs also share other aspects of their everyday lives, and thereby construct an intimate connection, leaving audiences with a sense of getting to know the entrepreneurs at a personal level. Berryman and Kavka (Citation2017) describe how youtubers, through sharing personal experiences, create authenticity as the basis of their authority. The invitation of audiences to take part of personal issues contributes to authenticity and strengthens affective bonds. The SUEs themselves are also the focal point of most visual content. The visual communication is representative of the ‘curated’ content often seen in social media, and is remarkably disconnected from mental health issues. Furthermore, the entrepreneurs frequently describe winning awards and other professional achievements. The balance of articulating vulnerability but also success is a continuous effort for SUEs. Accounts of success and curated content may attract audiences, but also challenge the authenticity of the SUEs. The Pill Podcast discusses these issues in a blogpost:

[We] often wrestle with the feeling and thought that you won’t be able to relate to us (without putting ourselves on some kind of pedestal, as if we were supahstarz), that we have lost the authenticity in our work, even though we KNOW ourselves that we haven’t. But we are afraid that it will be perceived that way, as if we have sold ourselves to the industry. We are afraid that you will feel that we have no idea what we are talking about. In addition to this, I have felt quite a lot of shame about working with mental illness, while I am feeling very well. Sure, I have my history and sometimes suffer from anxiety, etc, but “WHO doesn’t??” Anyway, we have had a great deal of doubt in ourselves. We have felt that we need to be extra “real” by showcasing the snot we picked and only post unedited pictures, while it has been damn nice just to show what’s pretty. The luxurious and silver lustrous.

Authority through intimate collectives

The SUE’s ability to attract audiences and form collectives around their causes is important as a source of authority and for building and maintaining a platform. The collectives that are formed are, however, loosely defined, both in relation to the structure of the networks and the cause in focus, and are mainly kept together through affective and intimate expressions.

SUEs’ constitution of networks around their causes through interaction with audiences is an important source of authority. Audiences are often directly addressed by the SUEs using an informal and conversational tone that contributes to a sense of co-presence. The Pill Podcast, for instance, ask their blog readers to provide responses and feedback: ‘Do you recognize yourselves?’ Readers and listeners are furthermore included in the company identity by being referred to as ‘pill podders’. This pattern of audiences being addressed directly as part of an in-group and invited to comment is also reflected in the communication of Wonderful ADHD at the company’s Facebook page: ‘Which tools of assistance do you think are the absolute best and worst for us with ADHD today?’ By interaction and sharing experiences online, abstract but still joint communities can be formed (Lindgren, Citation2014). This collective dimension of SUEs’ activities contributes to their authority, as experiences become more ‘weighty’ and gain authority as they collectivise (Noorani, Citation2013). The communication frequently draws on discourses of collective mobilisation referencing a joint struggle and demands for change, as exemplified by a post on Neveralone’s Facebook page:

People who have contributed to the struggle to erase the prevailing shame and taboo have left us too early. These heroes must not be forgotten; we must continue to plead their cause and carry the message forward. We raise our voices, keep the flame alive and create change. We create a climate where mental illness is seen as any other accepted disease. A climate where help-seeking isn’t shameful. A climate where we promote choosing life! Let this voice be heard, let this flame shine where it is needed; now we are creating change. Now we are saving lives!

We welcome everyone to, together with us, take a stance for a more equal and inclusive Sweden where everyone, regardless of function variation and/or ethnical background etc., will get the right conditions to achieve their full potential. It really doesn’t matter why or in what way you want to say #fuckprejudice – just that you do it!

You can show your support by:

Buying t-shirts, sweatshirts & hoodies with the message Fuck prejudice in Wonderful ADHD’s online store (under development)

By using the hashtag #fuckprejudice when you share one/several posts with optional position in social media

L O V E

Now we fill social media with love. Show your appreciation; share the love with your family and your friends.

It is through love that we lift each other and push each other forward in the struggle against mental ill-health.

Authority through institutional perspectives

To construct authority, the SUEs also draw on formalised sources of authority in their communication. The entrepreneurs’ stance and relationship to the mental health service system is mainly consensus-oriented, and they frequently feature perspectives from research and mental health professionals in their channels. Furthermore, the SUEs include actors with a position of authority in other fields, such as politicians. Thus, the experiential authority and the authority derived from them having a platform and followers is supplemented with institutionalised forms of authority.

The SUEs have mostly adopted a consensus-oriented approach to the mental health service system. Neveralone is never critical of mental health services, but rather encourages people to seek help from them. Through a Facebook update, Neveralone praises mental health professionals for the work that they do:

We need to help each other, support each other and stay positive.

It takes time, energy and many setbacks, but it is possible.

Now we send love to everyone who is struggling, everyone who provides support and all the heroes working in psychiatry.

In general, the focus is on collaboration and The Pill Podcast, for instance, describes how they through their activities can increase trust among young people for public institutions and mental health services. Lakeman et al. (Citation2007) argue that celebrity service users that align with hegemonic biomedical perspectives are most likely to gain authority and become successful. By assuming a consensus-oriented position in relation to hegemonic institutions, multiple sources of authority are available to draw from. Lay voices filtered through biomedical discourses can, however, run the risk of reproducing consumer discourses where mental health issues are individualised (cf. Goldstein, Citation2015). Dependency ties of SUEs to public sector actors as buyers of services such as educational programmes and lectures are also part of this consensus-oriented approach.

Even though an experiential perspective dominates the communication of SUEs, they also draw on institutional sources of authority in their communication. This is most evident for the podcast Insanely. On many issues the expressed views align with the dominating position within the mental health service system, arguing for the importance of evidence-based treatment, and featuring psychologists and psychiatrists as experts. The podcast has an educational ambition, discussing research results, methods of treatment and specific disorders. Insanely has, in relation to the other SUEs, a greater emphasis on complementing the experiential authority based on the entrepreneur’s own background with more general and depersonalised content that draws on formalised sources of authority. This pattern is visible in the description of his lectures:

[The founder] is one of Sweden’s best and most appreciated lecturers on mental health. He gives lectures all over the country during municipal psychiatry days, at schools, companies and organisations. His lecture about mental health, depression and panic disorder covers both his personal experiences and the basic science of mental illnesses.

Apart from mental health professionals, the SUEs also include actors with a status position in other areas in their communication. The Pill Podcast on multiple occasions references a dialogue with the Swedish Minister for Education as a testament of their influence within the field, and the founder of Wonderful ADHD describes being invited to give a lecture in the Swedish Government Offices as one of his greatest professional achievements. These connections to government authorities are constructed as sources of authority by further legitimising SUEs activities.

Discussion

Discussions of service user engagements often revolve around service user groups resisting authority (Noorani, Citation2013). In this study, we have instead focused on the positivity of authority by examining how SUEs themselves legitimise their voice and influence. In accordance with Dawney’s (Citation2013) description of a current pluralisation of knowledge practices, the SUEs included in our study claim authority through a multitude of sources, both by presenting themselves as ‘experts-by-experience’ (Noorani, Citation2013), through building intimate collectives around their causes and by including sources of institutional authority. In this section, we will discuss emerging conflicts that SUEs manage, as authority is articulated, endangered and reinstated.

Tensions between the ‘I’ and the ‘we’

Service user organisations have several claims to authority. They draw on democratic ideals of opinion representativeness and power levelling, where socially vulnerable groups join together to advocate for their interests (Karlsson, Citation2011). The authority of service user organisations could also be understood in relation to how they represent experiential knowledge (Karlsson, Citation2011). Through service user movements, experiential knowledge has been shared, over time been collectivised and has gained in authority (Noorani, Citation2013). Being experts-by-experience is also central to SUEs’ claim to authority, but, in relation to service user organisations, these claims take on more individualised forms. Rather than representing the opinions or knowledge of a collective, the authority of SUEs has charismatic characteristics. Alike O’Neil’s (Citation2009) discussion of charismatic authority in online tribes, the traits of the individual, through the ability to produce an affective relationship and a sense of a mission among audiences, is central to how SUEs gain a platform and audience. Constructing an ‘I’ is important for producing authenticity, relatability and affective intensity that establish such affective commitment on the part of audiences. Having an audience and constructing a ‘we’ is, however, in itself a source of authority. A collective formed around a common if loosely defined cause produces more long-lasting engagement from audiences and lends impact to the experiences and opinions expressed. The balance in SUEs communication of, on the one hand, personalised narratives with the sender in focus, and on the other, articulations of collective narratives requires constant management.

Conflicts between individual and collective dimensions are further visible in the dual goals of moneymaking and a social mission. Making a profit is necessary for these entrepreneurs to be able to continue running companies and earn a living from their activities. If moneymaking for audiences overshadows contributions to a social good, this does, however, challenge the authenticity of SUEs. The openness on the part of the SUEs about accepting sponsorship from and promoting private companies, as well as them defining themselves as entrepreneurs, reflect a general trend towards acceptance of moneymaking and involvement of corporations in social change, that was formerly uncharacteristic of the Swedish context. Still, ‘too much’ emphasis on the business-side of these endeavours endangers their authority. In such instances of conflict, authority can be reinstated by returning to articulations of vulnerability and a collective cause aimed at a social good.

Managing desirable levels of vulnerability

The SUEs also need to continuously manage desirable levels of vulnerability, that constitute an important source of authority. However, vulnerability needs to be managed in order to produce empathic responses that strengthen relatability to the individual, but that do not overbalance into becoming too demanding for audiences. Regardless of the focus on mental health issues, the surfaces of SUEs’ communication are polished. Difficult experiences that suggest a loss of control are mainly consigned to earlier events in the SUE’s lives, that have now been regimented. In that sense, SUEs practice stigma-management (Goffman, Citation1963/Citation2014). A constant balance act is performed as easy-going content is mixed with accounts of vulnerability that produce affective intensity, while not spilling over into uncontrolled illness. Through this balancing act, the entrepreneurs are able to assume an authority position as guides on how to cope with mental ill-health or reduce mental ill-health in society. Managing levels of desirable vulnerability also makes SUEs more likely to reach a broader audience which could potentially contribute to reducing mental health stigma. However, the narratives produced mainly articulate perspectives of resource-strong groups and this could result in an exclusion of the narratives and needs of those who are lacking social resources or are most severely ill.

Concluding remarks

In this study, we have primarily been concerned with the activities of SUEs, but have not looked closer into how their audiences make sense of the interaction. To what extent do these expressions for audiences serve as peer-support, self-help, activism or other purposes? The dynamic between SUEs and established organisations is also important to explore. Democratic models of citizen involvement have come to be complemented by involvement based on employment relationships, where individual experts-by-experience are hired by service providers (Alm Andreassen, Citation2018). The case of SUEs is connected to this development towards individualisation, with an even more evident shift towards the logic of the market. But what are the long-term outcomes of these developments for democratic processes? These issues are pertinent for gaining insights into the future of service user movements.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare under Grant [number 2015-00414].

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Hilda Näslund is a PhD student in Social Work at Umeå University. Her research is focused on service user movements in the mental health area, post de-institutionalisation.

Stefan Sjöström is Professor in Social Work at Uppsala University. His research has often focused on power relations within the mental health field, particularly in relation to coercive treatment. He has also been involved in several projects regarding the criminal justice system’s handling of rape. In a recent project, he has been researching public relations within social service organisations.

Urban Markström is Professor in Social Work at Umeå University. His main area of research has been the transformation from institutionalised mental health care to supports integrated in the community. His research has also explored the introduction of market-systems in the mental health area and focused on the role of non-profit organisations within the Swedish welfare context.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alm Andreassen, T. (2018). From democratic consultation to user-employment: Shifting institutional embedding of citizen involvement in health and social care. Journal of Social Policy, 47(1), 99–117. doi: 10.1017/S0047279417000228

- Andersson, M. (2014). Grunden är den egna berättelsen. In M. Metell Suomalainen (Ed.), Fem år av (h)järnkoll: kampanjen som förändrade attityderna till psykisk ohälsa i Sverige [ Five years of (h)järnkoll: The campaign that changed attitudes to mental illness in Sweden] (pp. 13–17). Stockholm: Nationell samverkan för psykisk hälsa (NSPH).

- Beck, C. S., Aubuchon, S. M., McKenna, T. P., Ruhl, S., & Simmons, N. (2014). Blurring personal health and public priorities: An analysis of celebrity health narratives in the public sphere. Health Communication, 29, 244–256. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2012.741668

- Bennett, W. L., & Segerberg, A. (2013). The logic of connective action – digital media and the personalization of contentious politics. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Beresford, P. (2013). From ‘other’ to involved: User involvement in research: An emerging paradigm. Nordic Social Work Research, 3(2), 139–148. doi: 10.1080/2156857X.2013.835138

- Berryman, R., & Kavka, M. (2017). ‘I guess a lot of people see me as a big sister or a friend’: The role of intimacy in the celebrification of beauty vloggers. Journal of Gender Studies, 26(3), 307–320. doi: 10.1080/09589236.2017.1288611

- Clark, M. (2009). Social entrepreneur revolution: Doing good by making money, making money by doing good. London: Marshall Cavendish.

- Davidson, L., Bellamy, C., Guy, K., & Miller, R. (2012). Peer support among persons with severe mental illnesses: A review of evidence and experience. World Psychiatry, 11(2), 123–128. doi: 10.1016/j.wpsyc.2012.05.009

- Dawney, L. (2013). The figure of authority: The affective biopolitics of the mother and the dying man. Journal of Political Power, 6(1), 29–47. doi: 10.1080/2158379X.2013.774971

- Faulkner, A. (2017). Survivor research and mad studies: The role and value of experiential knowledge in mental health research. Disability & Society, 32(4), 500–520. doi: 10.1080/09687599.2017.1302320

- Findahl, O. (2014). Svenskarna och internet [The Swedes and the internet.] Retrieved from Stiftelsen för internetinfrastruktur http://www.internetstatistik.se/rapporter/svenskarna-och-internet-2014/

- Goffman, E. (1963/2014). Stigma: Den avvikandes roll och identitet [ Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity] (4th ed.). Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Goldstein, D. (2015). Vernacular turns: Narrative, local knowledge,and the changed context of Folklore. The Journal of American Folklore, 128(508), 125–145. doi: 10.5406/jamerfolk.128.508.0125

- Gunnarsson Payne, J. (2015). Från tvångssterilisering till Mors Dag [ From forced sterilization to Mother’s Day]. In E. Carlsson, B. Nilsson, & S. Lindgren (Eds.), Digital politik - Sociala medier, deltagande och engagemang (pp. 173–194). Riga: Diadalos AB.

- Gustafsson, N., & Winryb, N. (2017). The prevalence and durability of emotional enthusiasm: Connective action and charismatic authority in the 2015 European refugee crisis. Paper presented at the ECPR General conference, Oslo, Norway.

- Haugaard, M. (2018). What is authority? Journal of Classical Sociology, 18(2), 104–132. doi: 10.1177/1468795X17723737

- Hopton, J. (2006). The future of critical psychiatry. Critical Social Policy, 26(1), 57–73. doi: 10.1177/0261018306059776

- Johansson, A. (2013). “Låt dom aldrig slå ner dig.” Bloggen som arena för patientaktivism [ “Never let them beat you down.” The blog as an arena for patient activism]. Socialvetenskaplig tidskrift, 3(4), 203–221.

- Johansson, A. (2015a). Politisering av det personliga. Om sociala medier och mobiliseringen kring psykiatriska frågor [ The politicization of the personal. On social media and the mobilisation around psychiatric issues]. In E. Carlsson, B. Nilsson, & S. Lindgren (Eds.), Digital politik - Sociala medier, deltagande och engagemang (pp. 67–90). Riga: Daidalos AB.

- Johansson, A. (2015b). Postengagemanget. Om subjektivering och reifiering av sociala medier [ The post-engagement. On the subjectification and reification of social media]. In E. Carlsson, B. Nilsson, & S. Lindgren (Eds.), Digital politik - Sociala medier, deltagande och engagemang (pp. 19–38). Riga: Daidalos AB.

- Jones, M., & Pietila, I. (2018). Alignments and differentiations: People with illness experiences seeking legitimate positions as health service developers and producers. Health. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1177/1363459318800154

- Karlsson, M. (2011). Mobilisering genom självhjälpsgrupper [ Mobilisation through self-help groups]. In V. Denvall, C. Heule, & A. Kristiansen (Eds.), Social mobilisering – en utmaning för socialt arbete (pp. 119–130). Korotan: Gleerups Utbildning AB.

- Krupa, T. (1998). The consumer-run business: People with psychiatric disabilities as entrepreneurs. Work, 11(1), 3–10. doi: 10.3233/WOR-1998-11102

- Lakeman, R., Cook, J., McGowan, P., & Walsh, J. (2007). Service users, authority, power and protest: A call for renewed activism. Mental Health Practice, 11(4), 12–16. doi: 10.7748/mhp2007.12.11.4.12.c6332

- Landry, D. (2017). Survivor research in Canada: ‘Talking’ recovery, resisting psychiatry, and reclaiming madness. Disability & Society, 32(9), 1437–1457. doi: 10.1080/09687599.2017.1322499

- Lerner, B. H. (2006). When illness goes public: Celebrity patients and how we look at medicine. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Light, P. C. (2006). Reshaping social entrepreneurship. Stanford Social Innovation Review, 4(3), 46–51.

- Lindgren, S. (2014). Giving online support: Individual and social processes in a domestic violence forum. International Journal of Web Based Communities, 10(2), 147–157. doi: 10.1504/IJWBC.2014.060352

- Mandiberg, J. M. (2016). Social enterprise in mental health: An overview. Journal of Policy Practice, 15(1–2), 5–24. doi: 10.1080/15588742.2016.1109960

- Markström, U. (2003). Den svenska psykiatrireformen : bland brukare, eldsjälar och byråkrater [ The Swedish mental health reform: Among bureaucrats, users and pioneers]. Umeå: Umeå University.

- Markström, U., & Karlsson, M. (2013). Towards hybridization: The roles of Swedish non-profit organizations within mental health. Voluntas, 24(4), 917–934. doi: 10.1007/s11266-012-9287-8

- Myndigheten för vårdanalys. (2015). Sjukt engagerad – en kartläggning av patient- och funktionshinderrörelsen [ Sickly engaged – a mapping of the patient- and disability movement]. Stockholm: Myndigheten för vårdanalys.

- Noorani, T. (2013). Service user involvement, authority and the ‘expert-by-experience’ in mental health. Journal of Political Power, 6(1), 49–68. doi: 10.1080/2158379X.2013.774979

- O’Neil, M. (2009). Cyberchiefs: Autonomy and authority in online tribes. London: Pluto Press.

- Ostrow, L., & Adams, N. (2012). Recovery in the USA: From politics to peer support. International Review of Psychiatry, 24(1), 70–78. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2012.659659

- Parsloe, S. M., & Holton, A. E. (2018). #Boycottautismspeaks: Communicating a counternarrative through cyberactivism and connective action. Information, Communication & Society, 21(8), 1116–1133. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2017.1301514

- Rose, D. (2014). Patient and public involvement in health research: Ethical imperative and/or radical challenge? Journal of Health Psychology, 19(1), 149–158. doi: 10.1177/1359105313500249

- SOU. (2006:100). Ambition och ansvar: Nationell strategi för utveckling av samhällets insatser till personer med pskiska sjukdomar och funktionshinder [ Ambition and responsibilty: National strategy for the development of society’s support to people with mental illnesses or disabilities]. Stockholm: Edita Sverige AB.

- Trainor, J., & Tremblay, J. (1992). Consumer/survivor businesses in Ontario: Challenging the rehabilitation model. Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health, 11(2), 65–71. doi: 10.7870/cjcmh-1992-0013

- Videmsek, P., & Fox, J. (2018). Exploring the value of involving experts-by-experience in social work research: Experiences from Slovenia and the UK. European Journal of Social Work, 21(4), 498–508. doi: 10.1080/13691457.2017.1292220

- Weber, M. (1922/1978). The types of legitimate domination. In G. Roth & C. Wittich (Eds.), Economy and society: An outline of interpretive sociology. Vol. 1 (pp. 63–211). Berkely: University of California Press.

- Yin, R. K. (2007). Fallstudier: design och genomförande [ Case studies: Design and implementation]. Stockholm: Liber.