ABSTRACT

This research examines the legal capabilities of social care practitioners involved in a new decision-making process, ‘the kitchen table conversation’, used since the introduction of the 2015 Social Support Act in the Netherlands. This law delegates social care allocation to the local authorities, who employ social care practitioners to assess and decide upon the needs of applicants for personalised services. During the kitchen table conversation, social care practitioners, applicants and specialised services providers discuss the needs of applicants. The extent to which social care practitioners possess legal capabilities to deal with this new process is unknown. In a case study (Utrecht), data from kitchen table conversations with applicants suffering from cognitive impairment were gathered using participant observation techniques, semi-structured individual interviews and one group interview with social care practitioners, between October 2016 and May 2017. Content analysis showed the legal knowledge of social care practitioners and their awareness of the legal consequences of the kitchen table conversation. However, social care practitioners rely heavily on their interpersonal skills and on elective communication to avoid conflicts leading to legal procedures or involving their individual liability. More research is needed on the universal accessibility of social care services in the context of decentralisation.

SAMENVATTING

Dit onderzoek focust op de juridische competenties van sociale professionals die betrokken zijn bij het ‘keukentafelgesprek’, een manier van werken die is geïntroduceerd met de transities in het sociaal domein. Sinds de implementatie van de Wet maatschappelijke ondersteuning (Wmo 2015) zijn Nederlandse gemeenten verplicht onderzoek te doen naar de persoonlijke situatie van mensen die zich melden met een ondersteuningsvraag. De wet delegeert de toekenning van maatschappelijke zorg aan de lokale overheden, die sociale professionals inzetten om de behoeften aan maatschappelijke ondersteuning van cliënten te onderzoeken. Deze lokale professionals spelen tijdens dit proces een belangrijke rol bij de toekenning van de maatwerk oplossing. Tijdens het keukentafelgesprek worden de behoeften van cliënten in kaart gebracht, door de sociale professionals, in samenspraak met de cliënten en gespecialiseerde diensten. De mate waarin sociale professionals over de benodigde juridische kennis, vaardigheden en houdingsaspecten beschikken om dit proces vorm te geven is onbekend. Een case study (Utrecht) rond keukentafelgesprekken met cliënten met cognitieve beperkingen heeft plaatsgevonden. Aan de hand van participerende observaties, semi-gestructureerde individuele- en groepsinterviews zijn gegevens verzameld tussen oktober 2016 en mei 2017. Content analyse laat zien dat juridische kennis van sociale professionals en hun bewustzijn van de juridische gevolgen van het keukentafelgesprek aanwezig zijn. Desalniettemin leunen sociale professionals ook sterk op hun interpersoonlijke en communicatieve vaardigheden teneinde conflicten te vermijden die mogelijk tot bezwaarprocedures zouden kunnen leiden. Meer onderzoek is daarom nodig naar de toegankelijkheid van maatschappelijke diensten in de context van decentralisatie in het sociale domein.

Introduction

Decentralisation efforts have been characterising the social domain since the second half of the twentieth century throughout Western Europe (Minas, Wright, & Berkel, Citation2012) with local authorities such as municipalities becoming active agents in health and social care provisions (Petrasek, Tom, & Archer, Citation2002; Saltman, Citation2007). In the Netherlands, a new wave of changes affecting, among others, social services came into action with the introduction of the 2015 Social Support Act (Wmo 2015, hereafter ‘the new Act’, Citationn.d.). Under the banner of the ‘participative society’, the new Act was introduced along with further decentralizations of (social) care, employment and youth care services.

The new Act is relatively new legislation in the Netherlands, but similar legislation exists in the United Kingdom through the Care Act 2014 (The National Archives, Citation2014). Both Acts fundamentally reframe the statutory duties of local authorities. Their tasks have changed from arranging services for specific client groups to promoting people’s wellbeing, i.e. to enable them to remain independent. Therefore, local authorities have to assess the needs of clients, often suffering cognitive impairments and physical disabilities, who might require social care. For the first time personalisation is placed on a statutory footing in both countries, providing those who are eligible with a legal entitlement to (a personal budget for) care and support. Both Acts introduce the right to an assessment for adults in need of support (Woittiez, Eggink, Putman, & Ras, Citation2018). In practice, social care professionals execute this assessment while having to balance the needs of clients against the resources available to the local communities.

The assessment of the client’s needs, which has come to be known in the Netherlands as the ‘kitchen table conversation’, is to reveal whether generally accessible services (such as activities in a community centre) and the deployment of the usual support from their family, friends and acquaintances, is sufficient to help a client cope with his/her limitations (van Hees, Horstman, Jansen, & Ruwaard, Citation2018). In case those community services are inadequate or insufficient, clients can apply for personalised services, such as home care, a home accessibility improvement or specialised support by caregivers.

The kitchen table conversation

Each council implements the kitchen table conversation in its own way. In many cities, social district teams have been set up for these assessments on behalf of the council, which is the administrative authority. Since the actual decision-making is often outsourced, it is not always clear to applicants and their representatives who formally decides on the allocation of personalised services: the council or the social district team (Eijkman, Citation2017). The composition of the social district team varies per district and council. The underlying organisational idea is that the group of professionals in the district team should together possess relevant expertise to address the needs of the geographical area, or district, in which they work. Professionals with a social work background account for a large part of the staffing of the district teams in the Netherlands (Arum & Van den Enden, Citation2018).

The assessment of the client’s needs in kitchen table conversation-settings is a new task for which professionals with a social work background have not been specifically trained during their formal education. The word ‘kitchen table conversation’ may suggest a homely cheerfulness and a non-committal attitude. However, the content of this discussion largely determines the personalised solution and the professionals act in areas that directly affect people and their rights, such as assistance, support and participation.

On the one hand, the transition to personalised care and support has given social professionals more room for manoeuvre. They can use their expertise to find solutions that suit the client's living conditions, without protocols seriously restricting their leeway. At the same time, personalisation within the new Act leads to new accountability requirements. For example, on what basis does a social care practitioner come to a decision on the content of a personalised solution? Moreover, the increasing emphasis on personalisation is changing the legal relationship between municipalities and citizens. According to the Dutch Social Domain Transition Commission, that it is precisely the fundamental change between government and citizens that has so far received too little attention (Transitiecommissie Sociaal Domein, Citation2016).

At the kitchen table, the changing legal relationship between the government and citizens is actually established by social care professionals in the district team. They are wearing two different hats here: they are both care provider and gatekeeper to the access to the resources under the new Act. This raises the question as to whether this group of social care professionals have the required knowledge, skills and attitude to work with the new legislation and regulations, as a part of their legal capability.

The legal capability framework

Until now, research and education have focused mainly on general support and supervisory competencies of social care professionals, such as the skilfulness to work with individuals, systems and groups (Jörg, Boeije, & Schrijvers, Citation2005). Decision-making studies in the United Kingdom didn’t focus specifically on the role of law but rather on the use of knowledge more broadly (for example; McDonald, Postle, & Dawson, Citation2008; Braye, Preston-Shoot, & Wigley, Citation2013). Research into the social care professionals’ legal competencies in attaining access to social support under the new Act is lacking. Do social care professionals recognise the legal implications of their practices? How do they deal with the accountability requirements in the context of the new Act? Especially for citizens who are less self-sufficient when it comes to access to justice, such as applicants with cognitive impairment, the way in which local professionals understand and implement legislation and regulations might influence the accessibility of social services.

The public legal education evaluation framework (Collard, Deeming, Wintersteiger, Jones, & Seargeant, Citation2011) is an analytical framework developed by the Bristol University Personal Finance Research Centre and Law for Life to evaluate legal capability. Although developed for its application to citizens, this framework lends itself to be adapted to those local social care professionals who are (also) acting as care givers and who support clients navigating through the legal aspects of the new Act. This task of social care professionals within the social district teams requires legal capabilities. The public legal education evaluation framework distinguishes four domains in which legal capabilities can be at play:

Recognising and framing the legal dimensions of issues and situations;

Finding out more about legal dimensions of issues and situations;

Dealing with law-related issues;

Engaging and influencing.

Each of these domains has four to seven indicators, as displayed in . The legal capability of citizens, or, in the case of the social district teams, the social care professionals, can be evaluated based on those indicators. The underlying idea is that individuals with more legal capabilities will be able to better navigate legal situations and therefore realise access to justice.

Table 1. Legal capability: the four key domains for evaluation (developed by Law for Life and Bristol University Personal Finance Research Centre; Collard et al., Citation2011, p. 12).

The present research aims at exploring the legal capabilities of social care professionals when dealing with the new Act during and around the kitchen table conversation, in the light of their increased room for manoeuvre.

The research question guiding the present study is as follows:

Which ‘legal capabilities’ do social care professionals in social district teams in the area of Utrecht, the Netherlands, use in their assessment of applicants with cognitive impairment?

The following sub-questions will be answered:

What knowledge of the procedure under the new Act do local social care professional display? (knowledge)

What legal skills do local social care professionals use in the realization of access to the resources under the new Act? (skills)

How do local social care professionals relate to the procedure under the new Act? (attitude)

Methods

Design

This research was conducted using a case-study design, defined as an ‘empirical inquiry that investigates a contemporary phenomenon in depth and within its real-life context especially when the boundaries between phenomenon and context are not clearly evident’ (Yin, Citation2003, p. 18). In the present study, the case is a set of three kitchen table conversations taking place in and around the area of Utrecht, involving individuals with cognitive impairments applying for a customised solution at one social district team. Kitchen table conversations were selected by the social care professionals themselves, based on the following indicators provided by the researcher: each must be about an application for a personalised service by a client with cognitive limitations (applicants). This demarcation made it possible to specifically observe the social care professionals’ dealings with people with similar limitations that restrict their legal capabilities, such as dementia.

Participant observations, individual interviews and one group interview were used as data collection tools. Participant observations and individual interviews were related to the three aforementioned kitchen table conversations, and a team meeting during which one kitchen table conversation was discussed. All kitchen table conversations took place between October 2016 and February 2017. The participant observation phase had two main goals: providing insights and knowledge of the contents and process of the kitchen table conversations, as well as providing input for the cases discussed during the subsequent interviews (individual and group). The group interviews yielded general information about the application procedure, which was also used as input for the individual interviews, and information on the attitude and skills of social care practitioners concerning the legal aspects of the new Act. The individual interviews were built up around cases of the kitchen table conversations in order to yield insights into the knowledge, skills and attitudes of the involved social care professionals.

Data collection

Participant observations

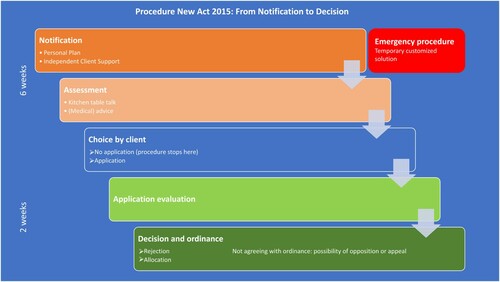

In participant observation, researchers take part in activities in the natural environment of the subjects (Spradley, Citation1980). The researcher (DC) attended personally all three kitchen table conversations as a participant observer. Elements from the general procedure under the new Act (see ) and indicators from the public legal education evaluation framework (Collard et al., Citation2011) served as an observation list. Kitchen table conversations were audio recorded and observation notes were taken in all cases. These recordings were made with the permission of both the social care professional and the applicant to a personalised solution, and with a signed a confidentiality statement from the researcher (DC). The researchers were aware that applicants, due to cognitive limitations, might not have fully understood the implications of giving consent. Therefore, the social care professional reached informed consent beforehand and the researcher (DC) asked for consent during the observation. Ethical issues where discussed within the research team according to the conduct statement of the Dutch Universities (VSNU, Citation2014).

Figure 1. Procedure under the new Act: from notification to decision. Schulinck / Wolters Kluwer Nederland B.V.

Source: Wet maatschappelijke ondersteuning 2015 (Citation2014).

Group interview

A group interview took place with three social care professionals from the social district team. One of them was involved in one of the kitchen table conversations. This group interview yielded information on the attitude and skills of social care practitioners concerning the legal aspects of the new Act. This interview (1,5 h, February 2017) was held using a topic list based on the legal procedure of the new Act.

Individual interviews

Five individual interviews were conducted with 4 social care professionals involved in the selected kitchen table conversations (n = 3) or in other kitchen table conversations (n = 1). One respondent was interviewed twice. During the interviews, respondents were asked about their own practices during the kitchen table conversation, in order to find out about their attitudes and skills concerning the legal aspects of the new Act. At the end of the interview, the procedure under the new Act was presented in order to test their knowledge (see ).

Participants

and give an overview of the respondents of individual and group interviews involved in this case study. General characteristics of the respondents are also displayed.

Table 2. Overview of respondents to the individual interviews and related kitchen table conversations.

Table 3. Overview of participants to the group interview.

Data analysis

This exploratory study used the public legal education evaluation framework (hereafter: legal capability framework) (Collard et al., Citation2011) as a guiding framework for analysing the data. The four key domains were further defined as ‘competencies’, based on the work of Roe (Citation2002), who relates competencies in the professional field to the necessary knowledge, attitudes and skills, which can be learnt and acquired, mostly through on-the-job training. Competencies are expressed in (concrete) behaviour, and related to a task or role within an organisation (Roe, Citation2002). The four legal dimensions of the legal capability framework are phrased as active verbs, and lean themselves to a competency interpretation. The four competencies and related legal capabilities (knowledge, skills, attitudes) were used to code the transcripts of the group and individual interviews. Observations recordings were as well coded using the same framework.

Additionally, the specific knowledge of the procedure under the new Act was tested based on the infographic displayed hereunder (). The related set of questions was included in the interview guide used for the individual interviews. Topics such as the client's right to independent support, knowledge of legal deadlines and the possibility for clients to object were included.

Both the infographic and legal capability framework served as a framework for the data analysis, which was conducted in an inductive manner, using content analysis. In order to increase objectivity in the data analysis, this phase involved three researchers (DC, QE, ML).

The methodological approach and results of the analyses were submitted to a sounding board group, which included two experts in the field of the 2015 Social Support Act and social work (mr dr M.F. Vermaat & dr E. Mudde).

Findings

Knowledge of the general legal procedure

Social care professionals were generally aware of the procedure under the new Act. They were aware of the right to independent advocacy. Also, the statutory deadline to complete the examination within six weeks after the client’s first contact was a well-known fact, as well as the fact that the client must be informed in writing of a decision within two weeks of an application for a personalised service has been submitted. The work processes are laid down in descriptions developed jointly by the council and the district teams. An IT system was set up to monitor the legal deadlines. However, the possibility for clients to submit a personal plan did not come up in the interviews nor during the kitchen table conversations.

All respondents were aware of the possibility for clients to appeal with the council against the district team’s decision. Five out of six social care professionals involved in the individual or group interview(s) knew of the possibility for clients to demand a periodic penalty payment if the statutory deadline is not met. In one individual interview with a social care professional, this subject was not raised. Two social care professionals referred to local ordinances of the municipality, such as quality criteria for personalised care, or maximum tariffs for care providers, as important to their work, but this was not mentioned by the other social care professionals. Several respondents generally referred to case law as guiding principles in the provision of customised services. Two team members with social-legal training had the task of keeping their team informed of changes in legislation and regulations. They occasionally meet with council officials who explain to them the ordinance and policy rules.

When looking at the legal capability framework, the knowledge elements displayed by the social care professionals are mostly related to the competencies ‘Recognising and framing legal issues’ (referring to the legal procedure, knowledge of deadlines and their legal consequences) and ‘Finding out more about legal issues’ (colleagues with the specific mandate of keeping track of changes in regulations). The competency ‘Dealing with legal issues’ is in turn negatively illustrated by the fact that the possibility for clients to submit a personal plan did not come up in the interviews nor during the kitchen table discussions.

Legal skills at the kitchen table

The job profile of district team social care professionals does not directly refer to legal skills (Rekenkamer Amersfoort, Citation2017). Social care professionals acquire the latter mainly from each other. As a social care professional puts it: ‘You contaminate each other with information’ (Individual interview, December 2016).

Local social care professionals generally believe that the content of a decision following a kitchen table conversation is influenced by several factors, including the way the application is worded, regardless of the actual nature of the application. According to them, framing an application within the legal context of the new Act, using the adequate lexicon, is a determining factor for an application to be granted. This comes to the fore in the following fragment from the group interview:

You are sent back sometimes, with a simple ‘do some additional research’. And sometimes you think: I will really have to pull out all the stops to win them [colleagues and the team leader] all over, and you have a decision within 5 minutes.

It is a surprise, every time again. [Laughing]

Yes, and the weakest side of it [decision-making on personalised care] to me is that it depends on the way we put it into words.

And on the person [professional] who presents it, whether the client gets what they need.

Or what they want.

Yes, it keeps you on your toes, yes.

Yes, so I find that quite tough.’

In an interview, a social care professional states:

It is important to already mention self-reliance and participation in the conclusion [of the action plan]. (…) Well, if you put it like: on the basis of our assessment, it has become clear that you are not self-reliant and cannot participate independently because of these and those limitations. If you don't get it, then this, this and that happens, and that is why it is necessary for these and those reasons that you get specialist support. Then you have substantiated within the framework of the new Act why you grant someone something. (Individual interview, December 2016)

‘Searching for protocols’ is a strategy implying setting new informal protocols to standardize the decisions and daily actions of social care professionals around the kitchen table conversations. Within the observed district team settings, the researcher noticed the presence of A4-printed lists, laminated in clear plastic, in the conference room. These lists contained seven working principles, established in partnership with the local authorities. Items such as “Early intervention and prevention come first” were included, as well as “Refer as effectively as possible (if additional care is required)”.

This need for practice-based criteria and protocols is also exemplified by the interview extract below, with a social care professional about setting a personal care budget for a client:

(…)those people are asking for a personal care budget for 28 hours/week of care and support for a family member. (…) Based on what they provide, we really cannot offer more than 20.5 hours.

How do you calculate the total number of hours?

The clients have written down what they do. We look into whatever we can reasonably decide, and which components come under usual care. (…) Just like home care, everything is itemised in a number of minutes. We simply add them all up.

Are there any standards for allocating or calculating that time?

No, and that is the annoying thing. A colleague [nurse] knows this from her experience in personal care because she worked for a home care provider. You just stick to the number of hours. Yes, why do things differently, those times have been set for a good reason. With hours of [personal] support [however], you have no grip whatsoever.’

What I like about it is: here [in this district team] is the working method: you present your case and you are not the only one to judge. As soon as I have presented the case, it is owned by all of us and whatever happens next is simply a team-based decision. (Group interview, February 2017)

The social care professional starts by explaining to an elderly client and her son that the visit is meant to see whether the decision on her daytime care should be extended. The client says that she certainly hopes so, because the daytime care came as a ‘godsend’ after a period in which she lost all her interest in life. The lady does not answer the social care professional's questions unambiguously; she narrates a range of events in her life. The social care professional listens attentively and regularly puts in a question for the purpose of her examination. After 45 min, she indicates that it is clear to her that the lady ‘would love to continue to visit the daytime care centre’. She explains that it is not only up to her, but that the decision is made jointly with colleagues. She promises to call the lady straight after their meeting two days later.

Afterwards, she tells the researcher that she had rather not left the client in uncertainty. The client was worrying at that point, whereas it was perfectly clear that the term of the decision should be extended. Yet, she stood by her actions: she believed it was important for the decision to be ‘team made’. The social care professional chose to leave the client in the dark in order to share the responsibility with her colleagues. From a care provider’s perspective, she would rather have informed the client immediately. (Kitchen table conversation, November 2016)

In the policy that arose in partnership with the council, this form of consultation with the team aims to create the opportunity to share knowledge and experience at case level and learn from one another. This would facilitate the establishment of a standardised assessment framework. For this reason, social care professionals often conduct visits in pairs so that they can use their individual expertise to assess a request for support. This rule seems to be different for applications for domestic care; it is usually the social care professional who makes the decision independently following the interview with the client.

The findings on the legal skills displayed by the social care professionals can mainly be related to the competency ‘Dealing with law-related issues’ from the legal capability framework. Those skills lead logically to the display of this competency, for example in the case of social care professionals using their legal skills in order to have their decisions phrased in ways that make them compatible with the law, or to adopt strategies to deal with law-related issues such as ‘team-reliance’.

Attitude about the legal aspects

The attitude of social care professionals towards the legal aspects of their work became clear when talking about potential objection procedures against written decisions launched by clients or their informal carers. Such a procedure may lead to liability requirements for the professional practices of social care professionals. As one social care professional puts it:

We do not let ourselves [in our daily work] be guided by legalities. You only have to deal with those when the client disagrees with you. So, the legalities only come up when a complaint or objection is in the making. Then, you suddenly become aware: “Oh, I do actually have to justify it all somehow”. What do the bylaw and the additional rules set by the council actually say? Does what we say hold up in court? (Individual interview, December 2016)

When it appears that clients might object to the decision because an agreement cannot be reached, the social care professionals might consult the council’s legal department to phrase the decision with the proper legal substantiation.

Social care professionals showed their awareness of their legal accountability, but also clearly stated that legal aspects were not guiding their daily practice. Instead, those were seen as an additional requirement they had to meet, especially in case an objection procedure would occur. Social care professionals also let the circumstances and perceived well-being of their clients prevail over the legal aspects of their work, for instance when it concerned the right to information of their clients. The following description of a kitchen table conversation exemplifies this:

During a kitchen table conversation, a social care professional chose to give hardly any information about the procedure of conversation to an elderly lady with early dementia. In the interview that followed, the social care professional explained he had restricted the information on purpose, as this would in his opinion confuse the client. Moreover, he thought it would stand in the way of developing trust. (Kitchen table conversation, January 2017).

When a care plan is established by a social care professional, based on the kitchen table conversation and discussed in the team, it is submitted to the client, including the proposed personalised solution. When including a personalised service, the client can apply for it by signing the report with ‘agreed’, whereafter the report counts as official application. However, if the plan concludes that the applicant is not entitled to the service, he/she can sign with ‘seen’. The applicant then can still apply for a decree against which objection and appeal are possible (Marseille & Vermaat, Citation2017). One of the interviewed social care professionals mentioned that this distinction and its implications are ‘certainly not understood’ by the clients, nor by the team members. In practice, social care professionals did not find out more about the difference between both signatures and its consequences, mainly because clients hardly asked questions about it.

Strengthening the client's legal position through independent advocacy is hardly mentioned during the interviews. When asked explicitly during the group interview, one social care professional states that this is something clients are entitled to, and makes the following observation:

And that can also be very helpful to us, them being there. They provide additional information; MEE Client Support [independent advocacy organisation] sometimes knows things we don't know, that can be useful. And it can also reassure the client that someone is accompanying them, making the whole process run more smoothly. It can also work against us sometimes, that there is someone sitting next to you and you think: well, this person is does not bring us any joy, digging their heels in. So, it differs. (Group interview, February 2017)

I have only had to deal with it [Penalty Payments (Overdue Decisions) Act] once within our team. You now try to be as transparent as possible to people and explain: times are busy, we are doing everything we can to meet that deadline, but if we can’t, we can decide retroactively. Then you find that a lot of people are okay with it all.

And as long as people agree, it is allowed?

It is a way to avoid problems, really. Yes, whether it is allowed, that’s a different matter [laughing], but it is a trick to prevent people making claims to the Penalty Payments Act.

Do you inform people that they can...

No. Until recently, I had never even heard of these penalty payments. Yes, and I do think, like, I am not going to make people wiser than necessary.

Social care professionals seem to be partly aware of several strict conditions such as the clients’ right to information, the possibility of independent advocacy and the possibility for clients to appeal to the written decision of the council. This awareness does not mean that they consistently act on it. Considerations as to the client's abilities and the conviction of their own professional diligence influence the way in which they are prepared to use available legal knowledge. They either act in the legal interests of the client or to strengthen the position of the district team.

When relating the attitudes of the social care professionals to the competencies underlying the legal capability framework, these findings show a relationship with the competencies ‘Dealing with law-related issues’ and ‘Engaging and influencing’. However, in both cases, these attitudes seem to undermine the related competencies. The general view that legal aspects are an additional requirement to comply with, and not a guide for the daily practice, seem to be at odd with the competency ‘Dealing with law-related issues’. This competency would only be displayed in case there is no other option, and not made an integral part of the daily social work practice. Likewise, respondents stimulate ‘personal strength’, but do not encourage the client legal power to the same extent. They allow the perceived well-being of their clients to prevail above their right to information. These attitudes lead to a low ‘Engaging and influencing’ competency in terms of the legal capability framework.

Conclusion

The present research focused on the legal capabilities that social care professionals in the Netherlands use around new legislation, when assessing the needs of applicants with cognitive impairment. Comparable to the Care Act 2014 in the United Kingdom, the 2015 Social Support Act reframes the statutory duties of the local authorities and introduces the right to an assessment for adults in need of support, placing personalisation on a statutory footing for the first time. This is an essential difference with the previous situation, where social care practitioners used formalised protocols and guidelines on which to base a decision for social support. These are being dismissed, making room for personalisation.

During the observations and interviews, qualitative data were gathered on general knowledge of the new Act procedure, and on the displayed skills and attitudes of social care practitioners in order to deal with the legal aspects of the new Act. Our analyses showed that general knowledge of the procedure and statutory deadlines of the new Act was present among local social care practitioners, as well as their awareness of the right of clients to be informed, their right to independent advocacy and their right to appeal against a written decision by the council as responsible administrative authority.

The legal skills of the local social care practitioners were mostly displayed through their endeavour to formulate decisions and applications using terms that would fit the new Act. These were not part of the skill set of social care practitioners to begin with, but were acquired on-the-job. Generally, they tended to see the new Act as an additional requirement of their role, which they had to deal with, but which was not providing the necessary guidelines they needed to base decisions upon. The experienced lack of guidelines and protocols was dealt with by relying on the district team, and by looking for team-made decisions about individual cases. The second strategy to counter this lack of guidelines was to reinvent local, informal protocols in order to standardise the decisions and daily actions around the kitchen table conversations.

On the attitude of social care professionals regarding the new Act, and how social care professionals relate to the legal application procedure, results showed that, even if the knowledge and awareness of the procedure and the rights of clients was present, this legal knowledge was not necessarily used primarily for strengthening the client's legal position, but also to defend the position of the district team and of the individual social care professional. Considerations as to the client's abilities and the conviction of their own professional diligence influenced the way in which they were prepared to use available legal knowledge.

As a local case study, focusing on clients with cognitive impairment, the results cannot be generalised and might not represent the legal capabilities displayed by social care professionals in other district teams in the Netherlands, nor represent the legal capabilities displayed by social care professionals when dealing with other types of clients. Moreover, the public legal education evaluation framework used in this study was applied for the first time to map out the legal capabilities of professionals rather than citizens. Further amendments to this framework are needed to develop a better analytical frame for assessing the legal capabilities of professionals. This first application of the legal capability framework to the work of social care professionals made clear that although competencies can be theoretically distilled from the framework, the extent to which these competencies as displayed by social care professionals are beneficial to the legal empowerment of clients is still an object of discussion and would need to be empirically tested.

The data were qualitative and the analyses involved the judgement, interpretation and therefore subjectivity of the researchers. This methodological limitation was partly compensated by relying on a team of researchers and setting up a sounding board group.

Despite these limitations, we can conclude that although the institutional context of the district teams contributes to a ‘humanised legal relationship’ between the government and citizens (Vonk, Klingenberg, Munneke, Tollenaar, & Vonk, Citation2016), two main unintended consequences can be outlined. First, the disappearance of formal protocols and guidelines is an invitation to reinvent those for social care professionals who lack standardised guidelines to base decisions upon. Second, daily practice shows that strengthening the legal position of clients is not necessarily the priority of social care professionals when applying their legal skills. Social care professionals seem to ‘pick and choose’ legal idiom in order to have their decisions phrased in ways that make them compatible with the law, local government policy and clients’ needs. These findings are aligned with the findings of Braye et al. (Citation2013) on the ‘complex and nuanced’ way social care professionals incorporate legal rules in their decision-making. References to the law are more likely to be ‘implicit’ than ‘explicit’ and the absence of legal references is a striking feature in their narratives (Braye et al., Citation2013). While applying the new Act, social care professionals refer to the law, but mostly in an instrumental manner (i.e. when they cannot avoid it and/or or need it).

However, it can be argued that social care professionals need a better understanding of the law to defend their use of powers and duties on the local level. The ability to articulate practice knowledge more broadly is essential to accountability and quality service delivery (Osmond & O’Conner, Citation2004), especially in the face of a ‘complex, messy reality’ (Zacka, Citation2017) of balancing their clients’ needs against the resources available to the local authorities.

Our findings suggest that higher levels of legal literacy are needed, reaching further than mere knowledge of the law. Emphasis on attitudes and skills must be considered to the development of ‘mature legal literacy’ (Braye et al., Citation2013) and firmly embedded in a strong sense of justice as the cornerstone of Social Work (IFSW & IASSW, Citation2014) in order to strengthen the clients’ legal position.

Acknowledgement

Our gratitude goes to the sounding board, mr dr Vermaat and dr Mudde, for reviewing the manuscript from their expertise, both methodological and in the field of the New Act 2015. Our thanks go as well to mrs. Prikken MSc., Triangle Community Services, London, for her helpful comments on the text of the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Dorien Claessen

Dorien Claessen (Msc) is an anthropologist, researcher and lecturer Social Work at the Utrecht University of Applied Sciences. Her research focusses on the link between Human Rights and Social Work and the role of local social professionals.

Quirine Eijkman

Quirine Eijkman (Phd.) is chair of the Research group Access2Justice at the Utrecht University of Applied Sciences and Deputy President of the Netherlands Institute for Human Rights. This article is written in her personal capacity.

Majda Lamkaddem

Majda Lamkaddem (Phd.) is a sociologist, senior researcher and lecturer at the Utrecht University of Applied Sciences. Her field of research encompasses social, cultural and financial factors at play in the universal accessibility to Justice.

References

- Arum, S., & Van den Enden, T. (2018). Sociale (wijk)teams opnieuw uitgelicht [Social (district) teams highlighted]. Utrecht: Movisie.

- Braye, S., Preston-Shoot, M., & Wigley, V. (2013). Deciding to use the law in social work practice. Journal of Social Work, 13(1), 75–95. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1468017311431476

- Collard, S., Deeming, C., Wintersteiger, L., Jones, M., & Seargeant, J. (2011). Public legal education evaluation framework. Bristol: Personal Finance Research Centre, University of Bristol. Retrieved from http://www.bristol.ac.uk/media-library/sites/geography/migrated/documents/pfrc1201.pdf

- Eijkman, Q. A. M. (2017). Toegang tot het recht gaat glocal [Access to justice goes glocal]. Openbare les Lectoraat Toegang tot het recht. Utrecht: Kenniscentrum Sociale Innovatie.

- IFSW & IASSW. (2014, August 6). Global definition of social work. Retrieved from https://www.ifsw.org/global-definition-of-social-work/

- Jörg, F., Boeije, H. R., & Schrijvers, A. J. P. (2005). Professionals assessing clients needs and eligibility for electric scooters in the Netherlands: Both gatekeepers and clients advocates. British Journal of Social Work, 35(6), 823–842. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bch279

- Marseille, A. T., & Vermaat, M. F. (2017). Burgers op zoek naar rechtsbeschermingin het sociaal domein [Citizens seeking legal protection in the social domain]. Handicap & Recht, 1(1), 9–15. doi: https://doi.org/10.5553/HenR/246893352017001001003

- McDonald, A., Postle, K., & Dawson, C. (2008). Barriers to retaining and using professional knowledge in local authority social work practice with adults in the UK. British Journal of Social Work, 38(7), 1370–1387. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcm042

- Minas, R., Wright, S., & Berkel, R. V. (2012). Decentralization and centralization: Governing the activation of social assistance recipients in Europe. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 32(5/6), 286–298. doi: https://doi.org/10.1108/01443331211236989

- Osmond, J. L., & O’Conner, I. (2004). Formalizing the unformalized: Practitioners’ communication of knowledge in practice. British Journal of Social Work, 34, 677–692. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bch084

- Petrasek, D., Tom, F. E., & Archer, R. (2002). Local rule, decentralisation and human rights. Versoix: International Council on Human Rights Policy.

- Rekenkamer Amersfoort. (2017). Rekenkameronderzoek. Effectiviteit en efficiëntie sociale wijkteams Amersfoort [Court of Audit Report. Effectiveness and efficiency of social district teams Amersfoort]. Amersfoort: Panteia. Retrieved from https://www.panteia.nl/uploads/sites/2/2017/10/Rekenkamerrapport-effectiviteit-en-efficiëntie-sociale-wijkteams-Amersfoort.pdf

- Roe, R. A. (2002). Competenties – Een sleutel tot integratie in theorie en praktijk van de A&O-psychologie [Competences – A key to integration into the theory and practice of A&O psychology]. Gedrag en Organisatie, 15(4), 203–224.

- Saltman, R. B. (2007). Decentralization, re-centralization and future European health policy. The European Journal of Public Health, 18(2), 104–106. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckn013

- Spradley, J. P. (1980). Participant observation. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

- The National Archives. (2014, May 14). Care Act 2014. Retrieved from http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2014/23/contents/enacted

- Transitiecommissie Sociaal Domein (TSD). (2016). Decentralisaties in het Sociaal Domein: Wie houdt er niet van kakelbont? Essays over de relatie tussen burger en bestuur [Decentralizations in the social domain: Who doesn't like a mix of colors? Essays about the relationship between the citizen and government]. Den Haag: Rijksoverheid.

- van Hees, S., Horstman, K., Jansen, M., & Ruwaard, D. (2018). How does an ageing policy translate into professional practices? An analysis of kitchen table conversations in the Netherlands. European Journal of Social Work. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2018.1499610

- Vonk, G. (Ed.), Klingenberg, A., Munneke, S., Tollenaar, A., & Vonk, G. (2016). Rechtsstatelijke aspecten van de decentralisaties in het sociale domein [Constitutional aspects of the decentralizations in the social domain]. Groningen: Rijksuniversiteit Groningen, Vakgroep Bestuursrecht & Bestuurskunde.

- VSNU. (2014). The Netherlands code of conduct for academic practice principles of good academic teaching and research. The Hague: Association of Universities in the Netherlands.

- Wet maatschappelijke ondersteuning 2015 [2015 Social Support Act]. (2014, July 9). Retrieved from http://wetten.overheid.nl/BWBR0035362/2018-01-01.

- Wmo 2015 Procedure [2015 Social Support Act Procedure]. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.schulinck.nl/domeinen/sociaal-domein/wmo/wmo-2015-procedure.18328.lynkx

- Woittiez, I., Eggink, E., Putman, L., & Ras, M. (2018). An international comparison of care for people with intellectual disabilities. An exploration. The Hague: The Netherlands Institute for Social Research.

- Yin, R. K. (2003). Case study research: Design and Methods. London: Sage Publication.

- Zacka, B. (2017). When the state meets the street. Public service and moral agency. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.