ABSTRACT

Since the 1990s, evidence-based practice has become part of social work, grounded in the notion that social work should be a research-based profession. However, recent studies show that social workers struggle with bridging research and practice. This study analysed Norwegian social workers’ use of knowledge in their daily practice, drawing on data from a survey consisting of 2060 social workers in different practice fields as well as qualitative interviews with 25 social workers from social services and child welfare services. Analyses of the quantitative data revealed that clients, work experience, and colleagues were the three most common sources of knowledge among the social workers. The use of knowledge could be divided into two subgroups: (a) theory-oriented and (b) practice-oriented. The qualitative interviews revealed that social workers valued work experience, colleagues, supervisors, and clients as their main sources of knowledge. Lack of time was identified as the main barrier for engaging in research. The findings in this study are contextualised with theories on knowledge production and translation in social work, arguing that field instructors, supervisors, and social work education play an essential role both in facilitating evidence-based practice and, more broadly, in bridging the gap between research and practice.

SAMMENDRAG

Siden 1990-tallet har evidensbasert praksis blitt en del av sosialt arbeid, forankret i en idé om at sosialt arbeid skal være en forskningsbasert profesjon. Studier viser imidlertid til at det har vært utfordrende å overføre forskningsresultater til praksis. Denne studien analyserer norske sosialarbeidere sin bruk av kunnskap i deres daglige praksis, med utgangspunkt i data fra en undersøkelse bestående av 2060 sosialarbeidere fra forskjellige praksisfelt, og kvalitative intervjuer med 30 sosialarbeidere og ledere fra NAV og barnevernet. Resultater fra de kvantitative dataene viste at klienter, arbeidserfaring og kolleger var de tre vanligste kunnskapskildene blant sosialarbeiderne. Deres bruk av kunnskap i praksis kunne deles inn i to undergrupper: (a) teoriorientert og (b) praksisorientert. De kvalitative intervjuene viste at sosialarbeidere verdsatte arbeidserfaring, kolleger, veiledere og klienter som deres viktigste kunnskapskilder i praksis. Mangel på tid ble identifisert som den viktigste barrieren for å anvende forskning i praksis. Funnene i denne studien er kontekstualisert med teorier om kunnskapsproduksjon i sosialt arbeid, og argumenterer for at praksisveiledere, og utdanning spiller en viktig rolle både i å tilrettelegge for evidensbasert praksis, og for å bygge bro mellom forskning og praksis

Introduction

Social work is a multi-disciplinary profession utilising knowledge from different disciplines and professions, with a vast and widespread research and practice across fields and sectors. The International Federation of Social Workers (Citation2014) has defined social work as a ‘practice-based profession and an academic discipline that promotes social change and development, social cohesion, and the empowerment and liberation of people. Principles of social justice, human rights, collective responsibility and respect for diversities are central to social work. Underpinned by theories of social work, social sciences, humanities and indigenous knowledges, social work engages people and structures to address life challenges and enhance wellbeing’.

As a discipline, social work has struggled to articulate its theoretical knowledge base, and consequently social workers have struggled to articulate what their knowledge is in practice. This uncertainty has contributed to vigorous debates about the translation of research and knowledge to social work practices (Skedsmo & Geirdal, Citation2011; Taylor & White, Citation2006; Trevithick, Citation2008). For the past two decades, evidence-based practice (EBP) has arguably been the focal point in these debates. EBP is considered a framework for practicing social work with an increased focus on effective and research-based interventions, in accordance with teaching practitioners and students to critically utilise and appraise the best available scientific evidence (Howard et al., Citation2003). Although there are various definitions of EBP, the most cited is ‘the integration of best research evidence with clinical expertise and patient values’ (Sackett et al., Citation2000, p. 1). The EBP is described with five steps: (1) convert one’s need for information into an answerable question; (2) track down the best clinical evidence to answer that question; (3) critically appraise that evidence in terms of its validity, clinical significance, and usefulness; (4) integrate this critical appraisal of research evidence with one’s clinical expertise and the patient’s values and circumstances; (5) evaluate one’s effectiveness and efficiency in undertaking the four previous steps, and strive for self-improvement (Thyer, Citation2006, p. 168). EBP has, however, been subject to critique over the past decade; for example, the concept has been said to devalue clinical expertise as well as client values and preferences (Straus & McAlister, Citation2000).

Previous research on evidence-based practice and knowledge utilisation

Research on frontline practitioners’ attitudes and utilisation towards EBP suggests that one of the major issues with EBP is the confusion that surrounds it. This confusion is due to a lack of clarity about the concept, especially in terms of how it should be understood in relation to social work practice (Avby et al., Citation2014; Bergmark & Lundström, Citation2011; Björk, Citation2016; Grady et al., Citation2018; James et al., Citation2019; Knight, Citation2015; Scurlock-Evans & Upton, Citation2015; van der Zwet et al., Citation2019). One explanation for the confusion might be the unclear distinction between empirically supported treatments and EBP. EBP is a model that includes the client’s preferences, the social worker’s expertise, ethical considerations, and the availability of resources, while empirically supported treatments are interventions that exhibit positive results when applied to the client (Thyer & Pignotti, Citation2011).

Studies show that education, workshops, and training courses facilitate the use of EBP (Aarons et al., Citation2006; Edmond et al., Citation2006; Ekeland et al., Citation2019; Gromoske & Berger, Citation2017; Parrish & Oxhandler, Citation2015; Parrish & Rubin, Citation2011; Scurlock-Evans & Upton, Citation2015). Social work field instructors and supervisors have been shown to play an important role (Edmond et al., Citation2006; Parrish & Oxhandler, Citation2015; Tennille et al., Citation2016; Wiechelt & Ting, Citation2012). In a survey carried out by Parrish and Rubin (Citation2011) of 688 social workers of which 107 were field instructors, they found that the field workers were generally positive, showed high levels of familiarity, low levels of perceived feasibility and engagement in EBP. However, there was little difference between field instructors and non-field instructor’s orientation toward EBP.

There are several studies on EBP in social work, most of them focussing on practitioners’ attitudes to and knowledge about the concept. Fewer studies have covered social workers’ use of knowledge in practice, but those that do indicate that social workers generally value work experience, colleagues, and legal sources when making decisions in practice (Avby et al., Citation2017; Cha et al., Citation2006; McDermott et al., Citation2017; Osmond & O’Connor, Citation2006). Iversen and Heggen (Citation2016) surveyed 390 Norwegian social workers in child welfare services regarding their use of knowledge in practice. The results revealed that the social workers most frequently relied on colleagues, supervisors, and personal experience as sources of knowledge; research material, studies, books, and external sources were least frequently used. In order to understand knowledge translation within social work, there is a need to comprehend how social workers utilise knowledge when making informed decisions in practice. We therefore conducted a mixed-methods study including interviews with 30 social workers in social welfare and child welfare services along with survey data from 2060 social workers across different practice fields. This study has two aims: to better understand what sources of knowledge social workers use in their daily practice, and to illustrate how social workers’ use of knowledge fits an evidence-based framework.

Evidence-based practice and knowledge production in social work

In recent decades, EBP has been a central concept in the knowledge production and utilisation debate within social work. Gambrill (Citation2016) argues that although the importance of EBP is widely debated, social work is not grounded on empirical evidence; rather, the practices and policies implemented are based on views opposite to the long-term goals of social work, such as the goal of anti-oppressive social work practices. Accordingly, Gambrill and Parrish (Citation2015) emphasise that there is a gap between what research suggests is effective and the policies and practices that are actually used. In order to secure the well-being of service users, Gambrill and Parrish (Citation2015) advocate the need to minimise the gap between available research findings and social work practices.

Another concept related to EBP is critical appraisal, which involves professionals systematically raising questions regarding the needs of service users, finding the best evidence to respond to the questions, analysing the evidence, and using it in their decision-making (Sackett et al., Citation2000). A systematic literature review of knowledge utilisation models (Heinsch et al., Citation2016) revealed that one shortcoming of the EBP concept is that it views research and practice as separate domains. Seen from this perspective, the core of the problem is that social workers do not use research evidence when making professional decisions, and so the critical appraisal perspective of EBP is not achieved. Within this perspective, the professionals themselves are the key actors in making evidence-based decisions. Scholars also argue that the concept of EBP is too narrow for understanding the knowledge base in social work, and that the EBP process is unrealistic in social work practice because of limited information processing capacity, shortcuts in decision-making, and a lack of motivation from the social workers. Another criticism is the lack of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and meta analyses of RCTs to implement ‘the best available evidence’ in social work, not to mention the difficulty that professionals might face when applying the research in practice (Mullen & Streiner, Citation2004; Okpych & Yu, Citation2014).

Among the scholars who argue for a broader knowledge base in social work is Serbati (Citation2020), who advocates for going beyond the understanding of ‘what works’, to examine how knowledge influences the practitioner and in what contexts these processes occur. The first form of knowledge is external evidence, which is considered technical and instrumental, in that it focuses on ‘what works’. For example, RCTs are often considered to be the gold standard for evaluating interventions and promoting what many scholars consider to be ‘the best available evidence’. The second component of knowledge is internal evidence, which describes what governs the practitioner’s internal actions and decision-making. Serbati (Citation2020) argues that although the aim of external evidence, finding ‘what works’ is common when evaluating theoretical science, in social work it is the practitioner who guides the actions. This creates a need to understand what conditions can enhance the practitioner’s decision-making, in order to change their actions. Agreement between external and internal evidence requires reasoning and dialogue, which occur in the third knowledge component, communicative evidence. Here, the external and internal evidence are intertwined through dialogues where one discusses the use of evidence in practice. For instance, the social worker and the client can work together to challenge practical theories and together establish suitable strategies to tackle the client’s needs.

Data and methods

Data collection procedure

This study was based on a survey carried out by Ekeland et al. (Citation2019) in 2014–2015 along with 30 qualitative in-depth interviews with social workers in social and child welfare services carried out in 2019. The research was conducted in accordance with national norms of research ethics. In this study, child welfare workers and social workers were defined as social workers.Footnote1 The survey data covered 2060 social workers from four different counties in Norway. The social workers were registered members of the Norwegian Union of Social Educators and Social Workers, which includes 70–80% of all social workers in Norway. Ekeland et al. (Citation2019) contacted 5668 social workers through Questback and received a response from 2060 of the informants, comprising 36.3% of the initial sample. Responses were transmitted via encrypted email. The sample in this study consisted of 83% women and 17% men (). Almost half of the participants (51.5%) had further education beyond their bachelor’s degree in social work, and 8.9% of the participants had a master’s degree. The participants worked in a variety of different fields, but the largest group (23.5%) worked in child welfare services and the second largest (14.6%) in social services.

Table 1. Sample characteristics (N=2060).

The qualitative data comprised 30 semi-structured interviews with social workers in social and child welfare services, collected in 16 child welfare and social service offices located in five Norwegian counties. The social workers were selected with the aim of achieving variation in education, field of practice, gender, and geographic location. The counties were also selected based on the management and the social workers willingness to participate in the study, and travel distance from the researchers.

The first author sent an invitation letter and a description of the study to relevant social welfare and child welfare offices and private child welfare organisations in Norway. The requirement to participate in the study was that the social worker had to work in the field of child welfare or social welfare, or as an environmental therapist in child welfare institutions. The study was approved by the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (ref: 839506). Prior to their participation, the social workers received written information about the project and gave their written consent to participate and to be audiotaped. The first author transcribed 22 of the interviews using HyperTRANSCRIBE, and a research assistant transcribed the remaining eight. The transcribed interviews were kept anonymous, and the audio files were encrypted and stored on a secure server. The sample consisted of 25 social workers, 11 of whom worked in social services and 14 of whom worked in child welfare services (). The majority of the sample were female, and most of them were educated as social workers. Four of the informants were not educated social workers, yet worked within social services or child welfare services. One reason for this might be that these positions had not previously required higher education as a social worker.

Table 2. Sample characteristics (N = 25)

Quantitative and qualitative data

This study use a mixed-methods approach, that combines qualitative interviews with quantitative survey data in order to strengthen and expand the study’s validity and conclusions, and to achieve a greater integration of the data which allows for a more confident conclusion (O’Cathain et al., Citation2007; Schoonenboom & Johnson, Citation2017). We believe that the mixed-methods approach creates a broader understanding of how social workers use knowledge in practice by elaborating on quantitative and qualitative results, allowing a greater generalisation of the findings. The research questions of the qualitative and quantitative data are congruent, both exploring social workers perception of EBP and their use of knowledge in practice.

Measures

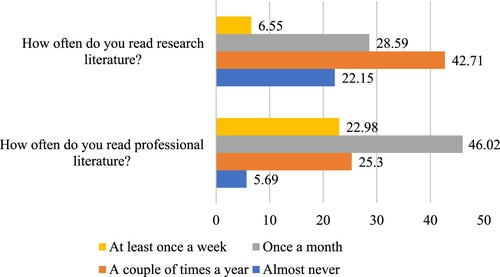

The quantitative data were drawn from a survey of 2060 social workers, all of whom were registered members of the Norwegian Union of Social Educators and Social Workers. The survey was developed to increase knowledge of Norwegian social workers’ attitudes and opinions about different aspects within the social work field, and included 70 questions regarding the social workers’ theoretical approaches within social sciences, attitudes towards EBP, knowledge utilisation, work conflicts, leadership, supervision, and demographic information. Ten items were used to assess the social workers’ sources of knowledge (), using the question ‘How important are the different sources of knowledge listed below for you to be able to do your job?’ with four response alternatives: 1 = ‘not important’, 2 = ‘somewhat important’, 3 = ‘important’, and 4 = ‘very important’. Frequency of reading professional and research literature was assessed by asking ‘How often do you read research literature?’, and ‘How often do you read professional literature?’ with four response alternatives: 1 = ‘almost never’, 2 = ‘a couple of times a year’, 3 = ‘once a month’, and 4 = ‘at least once a week’. Of the 2060 participants in the study, between 1880 and 1897 responded to the various items, thus the percentage of internal missing values was between 9% and 10% depending on the item in question.

Table 3. Mean and standard deviations of the 10 items used to measure the social workers’ sources of knowledge in practice, sorted in descending order

The interview guide

The qualitative data in this study were drawn from qualitative interviews with 30 social workers in child welfare and social services in Norway. The interview guide aimed at gathering data on the social workers’ attitudes towards EBP and knowledge utilisation in practice. The interview guide was divided into three main themes: (1) background and workplace, work position, education, job description, and motivation for working as a social worker, (2) decision-making processes in recent cases and sources of knowledge in practice, and (3) EBP, empirically supported treatments, and utilisation of manuals, standardised procedures, and use of knowledge in practice.

Analysis

Quantitative analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using version 25 of IBM SPSS Statistics. Descriptive statistics were calculated to show the participants’ characteristics and background variables (), and principal component analysis with varimax rotation was performed to identify patterns in the social workers’ knowledge utilisation (). Prior to the principal factor analysis, we tested the suitability of the data using the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy and Bartlett’s test of sphericity. The KMO value was 0.814, which is considered high enough to perform factor analysis (Kaiser, Citation1974), and Bartlett’s test of sphericity gave a significance level of p<0.001, again indicating that the data were suitable for principal factor analysis. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.755 for the 10 items, indicating sufficient internal consistency. Correlation analyses was used to study associations between background variables, use of knowledge and the two subscales derived from the factor analyses.

Table 4. Pattern matrix of principal component analyses with varimax rotation on 10 items for the social workers’ sources of knowledge in practice.

Qualitative analyses

The first author analysed the data from the interviews using thematic analysis as described by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006). A deductive and semantic thematic analysis was considered a suitable approach, as we had two distinct aims that clearly identified main themes in the analysis: ‘What are the sources of knowledge that social workers use in their daily practice, and how does social workers’ knowledge utilisation fit an evidence-based framework?’ The results from the survey data served as a premise for the qualitative analyses, allowing us to elaborate on specific areas. The interpretation of the interview data was semantic, meaning that the intention of the analysis was to describe the social workers’ statements rather than to make any interpretations beyond what they expressed.

The qualitative data collection was performed in six steps. The first step involved becoming familiar with the data material. During this phase, the first author wrote down immediate associations and thoughts while reading through the data. In the second step, NVivo 12 was used to develop the initial codes, resulting in 95 codes representing analytical perspectives on the data such as time management, education level, managers’ attitudes towards EBP, politics, past experiences, discretion, motivation, attitudes towards research, knowledge about empirically supported treatments, work-related courses, critical attitudes, positive attitudes, confusion, and terminology. The third step involved searching for initial themes in the coded material which produced 20 themes from the 95 codes; for example, colleagues and supervisors as sources of knowledge in practice were re-coded into a single theme. In the fourth step, these 20 themes were reviewed to see whether each theme was supported sufficiently by its data, or whether the data were too wide-ranging for a single theme. The theme that included educational level did not have enough data to support any claims, and was therefore removed from the analysis. The fifth step of the analysis comprised naming and defining the themes, and the sixth and final step involved the production and reporting of the findings.

Social workers’ use of knowledge

To examine how frequently the informants read research and professional literature, they were asked ‘How often do you read research literature?’ and ‘How often do you read professional literature?’. The informants read research literature less often than professional literature, with the majority of them (42%) reporting that they read research literature a couple of times a year and 22% reporting that they almost never read research literature. .

demonstrate that the social workers most often valued their clients, their work experience, and their colleagues when making informed decisions in practice. The least frequently used sources were reports after inspections, audits, revisions, and projects; and the Internet and social media.

We performed principal component analysis to allow deeper study of the various forms of knowledge. A factor analysis was conducted with the 10 items using varimax rotation, and principal component analysis was used to identify subgroups of the items. Based on the eigenvalues and the scree plot, we selected a two-factor solution which is demonstrated in . However, one of the items (‘Scientific journals and research material’) cross-loaded on both factors, indicating some complexity among the included items and suggesting that the factor measures several concepts.

The results from the factor analysis indicate that the social workers’ sources of knowledge can be categorised into two subgroups. Factor one, which we labelled ‘theory-oriented knowledge’, consists of eight items. This factor is a combination of written sources of knowledge in practice, and can be understood as comprising competence-oriented measures in social work, such as courses and training programmes, scientific journals, the use of supervisors, and reports. The second factor, which we labelled ‘practice-oriented knowledge’, consists of four items: colleagues, clients, work experience, and scientific journals. Theory-oriented knowledge has an explained variance of 31.68%, while practice-oriented knowledge has an explained variance of 13.29%. This suggest that the independent variables in theory-oriented knowledge better explain the theoretical concept. Pearson’s correlation analyses revealed a positive correlation between these two factors (r = 0.528, n = 1864, p = 0.01), indicating that the social workers valued various forms of knowledge from the two components as important, rather than solely taking a theory-oriented or practice-oriented perspective.

includes the mean, values, standard deviations and correlation coefficients for the 10 study variables included in the analyses. Short work experience comprises social workers with less than five years of experience, and long work experience include those with more than 20 years of work experience. The rest of the age groups have been used as a reference category. Those practicing in family counselling, correctional service, with refugees and asylum seekers, in geriatric social work and educational psychology are treated as reference categories in the analyses due to the low number of informants in the respective groups.

Table 5. Correlations among field of practice, tenure, and knowledge orientation (N = 1834).

The analyses reveal that working in drug counselling is positively correlated with theory-oriented knowledge r = 0.057, p < 0.05, and theory-oriented knowledge is negatively correlated with short work experience r = −0.051, p < 0.05. Being a child welfare worker is negatively correlated with practice-oriented knowledge r= −0.069, p < 0.05, and practice-oriented knowledge positively correlated with long work experience r = 0.049, p < 0.05. The correlations are low, yet they suggest that social workers in drug counselling are associated with theory-oriented knowledge, and practice-oriented knowledge is associated with social workers with longer work experience.

Work experience as a source of knowledge

The most common sources of knowledge mentioned in the interviews were work experience, colleagues, supervisors, and clients. Work experience was particularly highly valued by the social workers. Many explained that they valued work experience because they had worked in the field for many years and had obtained knowledge about the Norwegian welfare system as well as interpersonal skills that allowed them to make informed decisions with the clients and regarding their cases. The voice of the client was regularly emphasised as an important source of knowledge in the decision-making process:

We discuss issues at the team meeting and with the manager, then we go into detail on what we’ve done in the case, what we’ve seen, what we’ve received as information. The office is dependent on information from other agencies, otherwise we’d never have been able to get in touch with family and helped. […] It’s hard to know if we make things 100% right in every case, but we do the best we can. It’s justified by our experience, based on what we see, what we get in, the knowledge we have, the manuals we use, and to a great extent what the clients themselves say. (Social worker in child welfare services)

Colleagues and supervisors as a source of knowledge

The social workers had frequent meetings with their colleagues, where they presented and discussed cases. They also had weekly follow-up meetings with their supervisor where they discussed the progress and obstacles in their cases. The social workers described these meetings as meaningful, as providing insight into the development of their cases, and as an important source of knowledge when making informed decisions in practice. They were regularly given the opportunity to attend work-related courses, although a lack of time was the biggest obstacle to doing so. The social workers, particularly the case workers, regularly referred to the client’s professional network as a source of knowledge.

We have professional meetings at the office […] to exchange knowledge and discuss issues or meetings we’ve had, we have a very open dialogue, and it’s essential for quick follow-up and results. When I have a question about something, I can directly approach the right department and get an answer. I’m not asked to take an e-learning course, things are done right away, and that’s important, even though I take it for granted here in the office, I don’t think everyone has such open knowledge sharing. It’s become a culture, and people see that it’s working. (Social worker in social services)

Research literature as a source of knowledge

Few of the social workers reported that they actively kept up-to-date on new literature in their daily work. Most stated that ideally, they would like to spend time on reading literature, but the interviews suggested that they rarely had the time to do so. Some, particularly social workers in child welfare, stated that they used literature when they had to write reports that required research terminology; however, it was not specified whether this literature was categorised as research literature or professional literature.

It can be difficult when there’s a lot of work to do. The time is always a problem, we always talk about the time issue … it’s a big challenge in child welfare services. (Social worker in child welfare services)

Yes, I do [read research literature]. I’m so forgetful that I often have to look at my document with amendments. The law changes so fast, it’s important to stay up-to-date. (Social worker in social services)

Discussion

The main findings from the survey were that the social workers most frequently relied on clients, work experience, and colleagues when making decisions in practice, while the least common sources of knowledge were state guidelines, governance documents, reports after inspections, audits, revisions, and projects, and the Internet and social media. The social workers’ use of knowledge fell into two subgroups: theory-oriented knowledge and practice-oriented knowledge. Correlation analyses revealed a positive relationship between these two components, indicating that the social workers valued these various forms of knowledge. The analyses revealed that those with longer work experience to a higher degree value practice-oriented knowledge. It suggested that social workers in child welfare might be, while social workers in drug counselling were positively correlated with theory-oriented knowledge. The correlations are, however, low and warrant caution.

The main findings from the interviews were similar to those from the survey data. The social workers valued work experience, colleagues, supervisors, and clients as sources of knowledge when making decisions in practice. They explained that they had obtained particular skills that assisted them when making informed decisions in practice, and that this form of knowledge was achieved through their personal and professional lives. The client was important as a source of knowledge, as was the client’s network; perhaps because case workers in child welfare services request information from the client’s doctor, the police, and other parties when opening and assessing a client’s case.

Few of the social workers were up-to-date on the recent research literature, and many struggled to differentiate professional literature from research literature. Similar results were found in the quantitative data, with more than half (64%) of the social workers reporting that they read research literature a couple of times a year or almost never. As previously suggested, one of the core problems in practicing EBP is the social workers’ critical appraisal of research evidence (Heinsch et al., Citation2016). This study confirms the findings of other recent studies, in particular that social workers tend to value professional experience when making decisions, and that research literature is seldom used as a source of knowledge in practice. For instance, the results from the survey data were similar to those found by Iversen and Heggen (Citation2016), where 390 social workers in child welfare most often valued colleagues, supervisors, and professional experience, while journal articles, textbooks, and external sources were least frequently used. The present study demonstrates that social workers generally value a multitude of sources when making decisions in practice, but that research evidence is not considered essential in decision-making, meaning that the critical appraisal of the EBP model as described by Sackett et al. (Citation2000) is not fulfilled. To this, Rosen et al. (Citation2003) have argued that social workers’ lack of research utilisation could be addressed by introducing practice guidelines developed by researchers. In this way, social workers would be presented with evidence that is suitable for interventions without having to conduct searches and evaluate research evidence themselves.

Although practice guidelines might serve as quality assurance in social work practice, this idea raises several questions regarding the standardisation of the professional social worker, and whether a further push toward an instrumental EBP is beneficial. EBP has been suggested to be both technical and instrumental, with a focus on ‘what works’. However, the core of EBP lies within the practitioner’s ability to critically appraise the EBP steps. The practice itself is therefore deemed internal, and the use of EBP will not be achieved without what Serbati (Citation2020) describes as communicative dialogues, where one discusses the practical use of EBP and finds suitable strategies for its use. Recent research shows that social workers are still confused about the EBP concept (Ekeland et al., Citation2019; Grady et al., Citation2018; James et al., Citation2019; van der Zwet et al., Citation2019), arguably showing that externalised practice has yet to become internalised. In order to establish communicative dialogues to bridge the internal and external knowledge, there is a need to convey knowledge about EBP to social work practitioners. Research has demonstrated that higher education and work courses focussing on EBP have increased EBP behaviour and attitudes (Aarons et al., Citation2006; Ekeland et al., Citation2019; Gromoske & Berger, Citation2017; Parrish & Rubin, Citation2011; Scurlock-Evans & Upton, Citation2015). Social work supervisors and field instructors have been suggested to play an important part as EBP facilitators (Edmond et al., Citation2006; Parrish & Oxhandler, Citation2015; Tennille et al., Citation2016; Wiechelt & Ting, Citation2012).

Two main strategies are therefore suggested. First, there is a need for more evidence-based training courses in social work education so that students learn how to interpret and use research in their practice. This is important because there is too little knowledge about research and scientific thinking in social work education, and this must be the basis for practicing EBP, as well as a critical appraisal of the model. This strengthening of scientific thinking and research methods is also in line with recommendation from The Ministry of Higher Education in Norway.

Second, employers and fieldwork instructors can play an important role in facilitating social workers’ use of research in practice. For this to happen, the field instructors themselves must receive training in the EBP process. For example, Parrish and Rubin (Citation2011) demonstrated that it is possible to increase EBP awareness with a one-day continuing education training in EBP processes, with an increase in attitudes, perceived feasibility, intentions to engage in the EBP process, self-reported engagement in the EBP process, and knowledge about EBP; this was furthermore shown to be effective over time. However, it is essential that the integration of EBP practices occurs via communicative dialogues among and with the practitioners, in order not only to facilitate external change by implementing EBP and practices that are deemed suitable by scholars or governing authorities, but also to involve the practitioner in a way that enables internal change.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. Firstly, only 2060 out of 5668 social workers participated in the survey, producing a response rate of 31–32%. This low response rate in combination with internal missing might indicate that the questionnaire was too comprehensive, causing informants not to participate or to skip questions. Secondly, there were cross-loadings in the principal component analyses, indicating that some of the items were highly correlated. Thirdly, the data from the qualitative interviews were collected in only 5 of the 18 counties in eastern Norway, thus social workers in the remaining 13 counties were not represented. Finally, the survey data were gathered in 2014–2015 while the qualitative data were collected in 2019, meaning that there might be a gap between the results from the interviews and the survey. However, we believe that the mixed-methods approach in this article strengthens the validity of the results, as the findings from the survey data were used as a basis for the qualitative interviews, thus increasing our possibilities to understand the social workers’ use of knowledge.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Joakim Finne

Joakim Finne is a PhD Candidate in Social Work and Social Policy at Oslo Metropolitan University. He is currently researching evidence-based practices in the social sector.

Tor-Johan Ekeland

Tor-Johan Ekeland is Professor in social psychology at the Faculty of Social Science and History at Volda University College, and holds a part-time position at Molde University College, Norway. He has researched professional practice in different fields, for instance the relation between epistemologies and professional mental health practice, and neoliberal governance.

Ira Malmberg-Heimonen

Ira Malmberg-Heimonen is a Professor in Social Work at Oslo Metropolitan University. She has a lead a number of RCT-studies within the social and educational fields. Her interest areas are intervention studies, programme theory and fidelity, and the implementation of evidence-based practices.

Notes

1 In Norway, there are two options for professional education leading to a career as a social worker: a bachelor’s degree in social work, or one in child welfare. Social workers from both programs are commonly employed in a range of different fields and often intertwine across practices.

References

- Aarons, G. A., Sawitzky, A. C., & Deleon, P. H. (2006). Organizational culture and climate and mental health provider attitudes toward evidence-based practice. Psychological Services, 3(1), 61–72. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/1541-1559.3.1.61

- Avby, G., Nilsen, P., & Abrandt Dahlgren, M. (2014). Ways of understanding evidence-based practice in social work: A qualitative study. British Journal of Social Work, 44(6), 1366–1383. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcs198

- Avby, G., Nilsen, P., & Ellström, P. E. (2017). Knowledge use and learning in everyday social work practice: A study in child investigation work. Child & Family Social Work, 22(S4), 51–61. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12227

- Bergmark, A., & Lundström, T. (2011). Guided or independent? Social workers, central bureaucracy and evidence-based practice. European Journal of Social Work, 14(3), 323–337. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13691451003744325

- Björk, A. (2016). Evidence-based practice behind the scenes: How evidence in social work is used and produced. Stockholm University.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Cha, T., Kuo, E., & Marsh, J. C. (2006). Useful knowledge for social work practice. Social Work & Society, 4(1), 111–121.

- Edmond, T., Megivern, D., Williams, C., Rochman, E., & Howard, M. (2006). Integrating evidence-based practice and social work field education. Journal of Social Work Education, 42(2), 377–396. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5175/JSWE.2006.200404115

- Ekeland, T.-J., Bergem, R., & Myklebust, V. (2019). Evidence-based practice in social work: Perceptions and attitudes among Norwegian social workers. European Journal of Social Work, 22(4), 611–622. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2018.1441139

- Gambrill, E. (2016). Is social work evidence-based? Does saying so make it so? Ongoing challenges in integrating research, practice and policy. Journal of Social Work Education, 52(sup1), S110–S125. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2016.1174642

- Gambrill, E., & Parrish, D. E. (2015). Integrating research and practice: Distractions, controversies, and options for moving forward. Research on Social Work Practice, 25(4), 510–522. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731514544327

- Grady, M. D., Wike, T., Putzu, C., Field, S., Hill, J., Bledsoe, S. E., Bellamy, J., & Massey, M. (2018). Recent social work practitioners’ understanding and use of evidence-based practice and empirically supported treatments. Journal of Social Work Education, 54(1), 163–179. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2017.1299063

- Gromoske, A. N., & Berger, L. K. (2017). Replication of a continuing education workshop in the evidence-based practice process. Research on Social Work Practice, 27(6), 676–682. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731515597477

- Heinsch, M., Gray, M., & Sharland, E. (2016). Re-conceptualising the link between research and practice in social work: A literature review on knowledge utilisation. International Journal of Social Welfare, 25, 98–104. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/ijsw.12164

- Howard, M. O., McMillen, C. J., & Pollio, D. E. (2003). Teaching evidence-based practice: Toward a new paradigm for social work education. Research on Social Work Practice, 13(2), 234–259. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731502250404

- International federation of social workers. (2014). Global Definition of the Social Work Profession. https://www.ifsw.org/what-is-social-work/global-definition-of-social-work/.

- Iversen, A. C., & Heggen, K. (2016). Child welfare workers use of knowledge in their daily work. European Journal of Social Work, 19(2), 187–203. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2015.1030365

- James, S., Lampe, L., Behnken, S., & Schulz, D. (2019). Evidence-based practice and knowledge utilisation – a study of attitudes and practices among social workers in Germany. European Journal of Social Work, 22(5), 763–777. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2018.1469475

- Kaiser, H. (1974). An index of factor simplicity. Psychometrika, 39(1), 31–36. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02291575

- Knight, C. (2015). Social work students’ use of the peer-reviewed literature and engagement in evidence-based practice. Journal of Social Work Education, 51(2), 250–269. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2015.1012924

- McDermott, F., Henderson, A., & Quayle, C. (2017). Health social workers sources of knowledge for decision making in practice. Social Work in Health Care, 56(9), 794–808. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00981389.2017.1340391

- Mullen, E. J., & Streiner, D. L. (2004). The evidence for and against evidence-based practice. Brief Treatment and Crisis Intervention, 4(2), 111–121. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/brief-treatment/mhh009

- O’Cathain, A., Murphy, E., & Nicholl, J. (2007). Integration and publications as indicators of “yield” from mixed methods studies. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 1(2), 147–163. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689806299094

- Okpych, N. J., & Yu, J. L. H. (2014). A historical analysis of evidence-based practice in social work: The unfinished journey toward an empirically grounded profession. Social Service Review, 88(1), 3–58. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/674969

- Osmond, J., & O’Connor, I. (2006). Use of theory and research in social work practice: Implications for knowledge-based practice. Australian Social Work, 59(1), 5–19. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03124070500449747

- Parrish, D. E., & Oxhandler, H. K. (2015). Social work field instructors’ views and implementation of evidence-based practice. Journal of Social Work Education, 51(2), 270–286. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2015.1012943

- Parrish, D. E., & Rubin, A. (2011). An effective model for continuing education training in evidence-based practice. Research on Social Work Practice, 21(1), 77–87. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731509359187

- Rosen, A., Proctor, E. K., & Staudt, M. (2003). Targets of change and interventions in social work: An empirically based prototype for developing practice guidelines. Research on Social Work Practice, 13(2), 208–233. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731502250496

- Sackett, D. L., Straus, S. E., Richardson, W. S., Rosenberg, W., & Haynes, R. B. (2000). Evidence-based medicine: How to practice and teach EBM (2nd ed.). Churchill-Livingstone.

- Schoonenboom, J., & Johnson, R. (2017). How to construct a mixed methods research design. KZfSS Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie, 69(Supplement 2), 107–131. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11577-017-0454-1

- Scurlock-Evans, L., & Upton, D. (2015). The role and nature of evidence: A systematic review of social workers’ evidence-based practice orientation, attitudes, and implementation. Journal of Evidence-Informed Social Work, 12(4), 369–399. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15433714.2013.853014

- Serbati, S. (2020). Filling the gap between theory and practice: Challenges from the evaluation of the child and family social work interventions and programmes. European Journal of Social Work, 23(2), 290–302. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2018.1504751

- Skedsmo, H. S., & Geirdal, AØ. (2011). The development of knowledge for somatic hospital social workers in Norway: Implementation of a knowledge tool. Nordic Social Work Research, 1(2), 141–157. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/2156857X.2011.613576

- Straus, S., & McAlister, F. (2000). Evidence-based medicine: A commentary on common criticisms. Canadian Medical Association. Journal, 163(7), 837–841.

- Taylor, C., & White, S. (2005). Knowledge and reasoning in social work: Educating for humane judgement. The British Journal of Social Work, 36(6), 937–954. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bch365

- Tennille, J., Solomon, P., Brusilovskiy, E., & Mandell, D. (2016). Field instructors extending EBP learning in Dyads (FIELD): results of a pilot randomized controlled trial. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research, 7(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/684020

- Thyer, B. A. (2006). What is evidence-based practice? In A. B. Roberts, & K. Yeager (Eds.), Foundations of evidence-based social work practice (pp. 35–46). Oxford University Press.

- Thyer, B., & Pignotti, M. (2011). Evidence-based practices do not exist. Clinical Social Work Journal, 39(4), 328–333. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-011-0358-x

- Trevithick, P. (2008). Revisiting the knowledge base of social work: A framework for practice. British Journal of Social Work, 38(6), 1212–1237. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcm026

- van der Zwet, R. J. M., Beneken genaamd Kolmer, D. M., Schalk, R., & Van Regenmortel, T. (2019). Views and attitudes towards evidence-based practice in a Dutch social work organization. Journal of Evidence-Based Social Work, 16(3), 245–260. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/23761407.2019.1584071

- Wiechelt, S. A., & Ting, L. (2012). Field instructors’ perceptions of evidence-based practice in BSW field placement sites. Journal of Social Work Education, 48(3), 577–593. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5175/JSWE.2012.201000110